ABSTRACT

This paper introduces new tools for the cultural-historical analysis of children play in early years and how the cultural-historical genetic-analytical model can be applied as a tool of analysis of the role of children’s play in psychological development. The paper discusses the complexity of the interrelations of several situations in child’s play − 1) the imaginary situation; 2) the social situation; 3) the normative situation and 4) the social situation of development which might arise within the social situation depending on how the social situation is refracted through the prism of child’s perezhivanie. These theoretical concepts and the genetic-analytical model might be a powerful analytical tool to disclose the dialectical nature of child development in early years.

Introduction

Matryoshka is a set of Russian traditional wooden dolls of decreasing size placed one inside another. Thus, opening the first matryoshka doll, we find the second, and in it the third, and so on.

However, the matryoshka we discuss in this article is a particular cultural-historical one, in which when opening the first sphere (the social situation) we may or may not discover the second sphere (the social situation of development). Moreover, this matryoshka is arranged in such a way that when we open a social situation, we could find that it contains several social situations of development. The same way, when studying children’s play and uncovering the first sphere of play space (the imaginary situation), we could see there the second sphere (the social situation) or even several social situations with hidden spheres (social situations of development).

We use the metaphor of a matryoshka doll as an illustration of the relationships between several main concepts of cultural-historical theory that we discuss in this article − 1) social environment, 2) social situation, 3) social situation of development, 4) imaginary situation and 5) normative situation.

In doing so, we will draw on Vygotsky’s seminal works, which have only now appeared in new translations (Veresov Citation2019; Vygotsky Citation2016, Citation2021). We believe that these new materials, which are the part of what Veresov defines as a new reality with Vygotsky’s legacy (Veresov Citation2020), allow for revealing more deeply the dialectical nature of human development and significantly improve understanding of one of the basic ideas of Vygotsky’s theory of the social environment and play as a source of development of the child.

Social environment, social situation and social situation of development as dialectical unity

In this part of the article, we intend to show what is common and what is different in the three spheres of the cultural-historical ‘matryoshka’ − 1) social environment 2) social situation and 3) social situation of development.

Social environment as a source of development

In this section, drawing on Vygotsky’s seminal ideas and recently published new translations of previously unavailable texts (Vygotsky Citation2019, Citation2021), we show how Vygotsky’s position has been changed and improved over time specifically in terms of a deeper understanding of the dialectics of psychological development. We discuss how the dialectics of development might be disclosed when these concepts are used as analytical tools.

Let us begin with the most general proposition of cultural-historical theory: that the social environment is seen not as a factor that (along with internal bio-physiological factors) influences development, but as a source of psychological development. When introduced to the Western academia in 1978 (Vygotsky Citation1978), the idea of the social origins of human mind (Wertsch Citation1985, Citation1998) gave rise to a number of outstanding studies in the framework of Vygotsky’s theory (Cole Citation1997; Daniels, Cole, and Wertsch Citation2007), which is known in the West as sociocultural theory (Veer van der Citation2008) and in Russia as cultural-historical theory (Dafermos Citation2018; Miller Citation2011).

The development of the individual is the ‘path along which the social becomes the individual’ (Vygotsky Citation1998, 198). In its most general form, this position is expressed in the general genetic law of development, which states that any higher psychological function first appears on the stage of development on the social plane: as a social relation of people (inter-psychological form), and only then is there a transition into an internal individual intra-psychological form (Vygotsky Citation1997, 106).

This approach challenges the traditional view on development. In Vygotsky’s words: ‘… development is not simply a function which can be determined entirely by X units of heredity and Y units of environment. … development is an uninterrupted process which feeds upon itself; that it is not a puppet which can be controlled by jerking two strings’ (Vygotsky Citation1993, 253).

This approach opens the possibility of revealing the inner dialectic of a complex and contradictory process of development. In a recently published English translation of Vygotsky’s work, we find confirmation of this position: ‘… child development cannot be taken as a process guided and determined by some sort of outside forces or factors. The process of child development is subordinate to its own, internal regularities. It flows as a dialectical process of self-movement’ (Vygotsky Citation2021, 6).

The most important aspect of this dialectical process is that ‘all higher psychological functions originate as true social interaction between people’, and even being internalised, they ‘remain quasi-social’ (Vygotsky Citation1997, 106). Here, we see the cultural-historical theorisation of the dialectics of individual and social, where they are not taken as formal oppositions, but as a unity of dialectical opposites (for more detailed analysis see Veresov Citation2016, Citation2017). The individual here is understood not as a passive recipient of social influences, but as an active participant in social relations and interactions in various kinds of joint activity and communication. The dialectics here is that in the process of development the social becomes individual but does not die in it, and the individual, through his actions and interactions, becomes part of the social world but does not dissolve in it.

Comparing Vygotsky’s early works (Vygotsky Citation1993) and the later ones (Vygotsky Citation2021), we see his theoretical position on the place and role of the social environment remains unchanged, and only moves toward a deeper understanding of the internal dialectics of the process of human development.

Social situation of development: what makes the social environment a source of development?

In the last period of his work (1931–1934), Vygotsky took a major step forward, as a theoretical outcome of intensive experimental research, while retaining the general theoretical proposition of the social environment as the source of the psychological development of the individual. The concept of the social situation of development (SSD) was introduced. SSD is characterised as:

A completely original and unique relation between the child and social environment that

represents the initial moment of all developmental changes and

determines forms and the path along which the child acquires newer personality characteristics (Vygotsky Citation1998).

Returning to our metaphor, we might say that here Vygotsky reveals the second sphere of the socio-cultural ‘matryoshka’, where the first sphere – the social environment – contains the second, that is the social situation of development. There are at least two significant consequences that are coming from this. First, not every social environment is automatically a source of development. It only becomes a concrete source of development when a social situation of development emerges within it, and it does not become a source of development if no social situation of development emerges. The developmental potential of a child’s social environment can be realised if a social situation of development has arisen in that environment or will remain an unrealised potential if no SSD has arisen.

The second consequence is that the concept of SSD introduces the perspective of the child into the system of analysis, where the child is not approached as a more or less passive recipient or a more or less active ‘reflector’ of social influences, but as an active participant and contributor to social contacts, interactions, and shared cultural behaviours and activities with others. The concept of SSD shows that, from a developmental perspective, the child’s place, the active participation, and role in the social environment are no less important than the place and the role of social influences on the child from the social environment. In other words, the social environment and the social situation of development, although related, are not the same. SSD is that dynamic dialectical unity of the child and the social environment from which, as from the initial moment, the development-process unfolds, and which determines the unique form and individual trajectory of that process.

However, in firmly introducing the new concept of SSD into the system of theoretical concepts of cultural-historical theory, Vygotsky also introduces a new problem. The problem is this: what determines the appearance (or not appearance) of a social situation of development in the social environment? Are there criteria by which the analysis can identify and describe the mechanisms by which the social situation of development emerges? In other words, what makes the social situation of development within the social environment?

It seems to us that in a series of his pedological studies conducted in the last years of his life (1933–1934), Vygotsky suggested an answer to this question, based on an enormous amount of clinical material, and gave an example of the analysis of concrete social situations of development. We are referring to the materials of the pedological research on child development presented in a cycle of lectures which were long thought to have been lost but were fortunately found and published in Russia (Vygotsky Citation2001) and translated to English only recently (Vygotsky Citation2019).

In Lecture 4 ‘The Problem of Environment in Pedology’ (Vygotsky Citation2019, 65–84), we have an example of the analysis of the SSD where we can see Vygotsky’s advancement of the general proposition of the role of environment that he came to. Vygotsky gives an example from the clinic:

We are faced with three children brought to us from one and the same family. The situation in the family was awful because the mother drank and suffered from several nervous and psychological disorders. When drunk, the mother regularly beat her children or threw them to the floor and had once attempted to throw one of the children out of the window.

In this ‘situation of terror and fear in connection with these conditions’ (Vygotsky Citation2019, 70) the three children present completely different outcomes of development.

The youngest child reacted by developing several neurotic symptoms; that is, symptoms of a defensive nature in the form of attacks of terror, depression, and helplessness. In other words, the child reacted as though completely overwhelmed and helpless in this situation. The second child was developing a state of acute torment, a state of inner conflict ‘in the form of a positive and a negative relation to the mother, dire attachment to her and desperate hatred for her, along with acutely contradictory behaviour’ (Vygotsky Citation2019, 70).

And finally, the third and eldest child

… at first sight gave us a completely unanticipated impression … He understood that his mother was ill and pitied her. He had seen the younger children at risk when the mother was raging. And this accounts for his special role. He had to calm the mother and to watch over her so that no harm was done to the younger ones, and to console the younger ones. He was, after all, the elder of the family, the one who had to take care of the rest … This was a child who had changed drastically in development into a child of a different type.

Vygotsky begins the analysis with the question: ‘What determines the fact that the same environmental conditions have three different effects on three different children?’ The answer is this: ‘ … depending on the three different perezhivaniyaFootnote1 of one and the same situation, the impact that the situation has upon their development turns out to be different’ (Vygotsky Citation2019, 71). Importantly, Vygotsky does not speak about three different social situations: he speaks about three children being in the same social situation. He gives the answer to the question by saying that children’s different perezhivaniya determined the fact that the same social conditions had three different effects.

However, what is perezhivanie? Perezhivanie as a psychological phenomenon is ‘how the child is aware of, interprets, and affectively relates to a certain event’ (Vygotsky Citation2019, 71).

This example of analysis is interesting because it introduces a new layer of the matryoshka – a layer that lies between the social environment and the social situation of development. Some event in which the child is intellectually and emotionally involved is what Vygotsky defines as a social situation. The social situation of development arises (or does not arise) in the social environment, but only in relation to a certain event, that is, a certain social situation.

The social situation is not just reflected in the child’s mind; we are dealing with a much more complicated process: the social situation is refracted by the child’s individual perezhivanie. Various components (moments, parts, aspects) of the social event (social situation) are refracted differently in the perezhivanie of different children because of the individual psychological characteristics of the children. This ‘constitutes the prism which defines the role and influence of the environment on the development of … the child’ (Vygotsky Citation2019, 71). In this way, ‘it is not in itself this moment or that moment, taken without regard to the child, but that moment, refracted through the perezhivanie of the child, which is able to define how that moment will affect the course of future development’ (Vygotsky Citation2019, 69–70). Thus, in the perezhivanie of the child, a unique and exclusive unity of child and environment is created, a unique relationship between the child and the social environment appears.

In the book The Problem of Age (Vygotsky Citation2021) he makes a next step and summarises this in the form of general statement:

To give a somewhat general formal definition, it seems to me that it would be correct to say that the environment determines the development of the child through perezhivanie of the environment … and the forces of environment acquire a guiding significance thanks to the perezhivanie of the child.

This requires

a profound inner analysis of the perezhivanie of the child, that is, the study of the environment which is transferred to a large degree inside the child himself, and not confined to the study of the fixed external settings of his life.

This example of analysis demonstrates further development and improvement of concepts that are used as analytical tools. The first conceptual improvement is a rethinking of the concept of the social situation of development. Indeed, SSD was originally introduced in relation to the psychological age. Defining SSD, Vygotsky initially explained it as a unique relationship between a child and the environment which arises at the beginning of each psychological age and is related to age crises (Vygotsky Citation1998, 198). We can conditionally define this as a macro-SSD due to its long-time duration. In Lecture ‘The Problem of Environment in Pedology’ (Vygotsky Citation2019, 65–84) he improves this point and shows that SSD does not necessarily occur at the beginning of a psychological age; SSD can occur (or not occur) at the micro-level, depending on the micro-social situation in which the child finds himself.

The second theoretical advancement, as we have discussed above, is the introduction of a new concept – a social situation – and the proposition that not every social situation is the social situation of development. The child’s perezhivanie – the way the child perceives, understands, and interprets the situation – might lead to the appearance of SSD within a given social situation. However, in this case, like the macro-social situation at the beginning of psychological age, such a micro-social situation should appear in the form of a social event which contains a moment of contradiction, crisis, and drama (micro-crisis and micro-drama) which is refracted through the prism of child’s perezhivanie, making it a dramatic perezhivanie (Veresov and Fleer Citation2016). In this way, it turns out that between the two spheres of matryoshka − 1) the social environment and 2) the social situation of development – there is another one, which is called the social situation (an event).

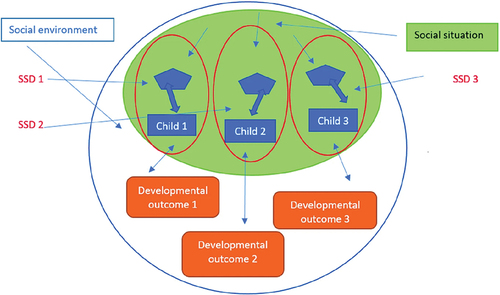

On this basis, taking an example of Vygotsky’s analysis of three children, Veresov (Citation2019) has developed the genetic-analytical model ().

Figure 1. Genetic-analytical model. Adapted from Veresov, N. 2019. ‘Subjectivity and Perezhivanie: Empirical and Methodological Challenges and Opportunities’. in Subjectivity within Cultural-Historical Approach, edited by F. Gonzalez Rey, A. Mitjans Martinez, and D. Goulart, 61–86. Singapore: Springer. Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature.

The social environment (white area) is an objectively existing sociocultural context, independent of the child, which surrounds the child. The social situation (green area) appears as a specific context in the form of an event where the child is a participant. The social situation as a component of the social environment is being refracted by the children through different dramatic perezhivaniya (blue prisms) making three different social situations of development (red circles) and leading to three different developmental outcomes in three children.

In the following section of the article, we, on the basis of this general model, will try to show how this might be applied to the study of child’s play. We will show what new ways of exploring children’s play can open up if we consider the play as a series of social situations: social situations of development that arise inside the imaginary situation.

Matryoshka of child’s play: imaginary situation, social situation, SSD and normative situation

In this part of the article, we will show what new possibilities the model the genetic-analytical model (Veresov Citation2019) might offer for exploring the developmental potential of play. In doing so, we continue to develop the cultural-historical theorisation of play that has been initiated in previous studies (Veraksa et al. Citation2020; Veresov and Veraksa Citation2022).

We begin with a brief overview of Vygotsky’s (Citation2016) article on play and its role in psychological development. Although this paper has been translated into English several times, here we use the newest translation of 2016 (for details on translations of Vygotsky’s paper see Veresov and Barrs Citation2016). This article is a seminal source for researchers studying play in the cultural-historical tradition (Duncan and Tarulli Citation2010; Edwards Citation2011; Elkonin Citation1978, Citation2005; Elkoninova and Bazhanova Citation2007; Fleer Citation2009, Citation2014; Kravtsova Citation1999, Citation2004; Holzman Citation2009; Lindqvist Citation1995 among others). On the other hand, it seems to us that the new translation of this seminal article by Vygotsky and the genetic-analytical model provides an opportunity to significantly advance the theoretical framework of play studies and to explore more deeply the dialectics of play and, consequently, its role in child development.

Imaginary situation

The imaginary situation (mnimaya situatsiya) is what Vygotsky sees as the main distinguishing feature of children’s play. Examples of imaginative situations range from simple ones, with a child riding a stick like a motorbike, to quite complex, for example, a group of children in a role play (family, hospital, etc.). The most important aspect of the imaginary situation is that it does not arise by itself but is created by the child (or children). Speaking dialectically, by creating imaginary situations, the child resolves a basic conflicting tendency: imaginary situations allow play to be a form of realizing unsatisfied desires of a child, desires which cannot be realized immediately in a direct form (Vygotsky Citation2016, 9). The imaginary situation is a core entity in the dynamic structure of play, and its investigation allows researchers to identify two main areas for analysis. First, in terms of the development of the play itself, the imaginary situation leads to the emergence and development within this situation of a complex hierarchical system of all the main components of play – the rules, roles, and actions that are subject to the plot of the game the children create. There are good reasons to believe that the creation of a play situation is the child’s first (primary) play action, which lies entirely within the realm of imagination as the higher psychological function.

Second, in terms of the psychological development of the child, the imaginary situation leads to the appearance of two fields – the visual field and the field of meanings (smyslovoye pole). Some objects in play (the stick) remain as they are while simultaneously acquiring the meanings of other, imaginary objects (the motorbike) in the field of meaning. The field of meaning (or semantic field of perception and actions) that emerges in an imaginary situation leads to a separation of the visible (optical) field and the field of meaning in the child’s perception and actions. The coexistence of the two fields of perception and action determines the main paradoxes and contradictions of play and makes it a source of the child’s psychological development.

Imaginary situation and social situations in play

Role play might be theorised as a social situation (or several social situations in the case of an extended plot) within the imaginary situation. This makes it possible to distinguish, for analysis, its structural elements (participants, actions/interactions, play objects, roles, and narratives of play) and its dynamical aspects (changes in the narrative, moments where the participant takes the lead role, etc.). Moreover, it makes it possible to study how the roles in the imaginary situation are ‘built into’ the plot and how the story determines the child’s actions in the role; in other words, it makes it possible to see how the original imaginary situation itself changes during play.

In play, the plot (such as a play of the wizard) can bring up social situations that the child does not encounter in real life; in play (e.g. pirates searching for treasure), actions that would not be possible in reality become possible within play context. Therefore, using the concept of social situation gives the researcher new possibilities for identifying the conditions for development that are created in the analysed imaginary situation of play.

Normative situations in real life and child’s play

In this section we introduce a normative situation into the matryoshka of play. In doing so, we build on our previously published research (Veresov and Veraksa Citation2022), and take the next step to identify the place and role of normative situations in the psychological structure of children’s play.

Researchers have introduced the concept of normative situation as a social and cultural regulator of human interactions (Veraksa and Bulitcheva Citation2003). Society develops specific systems of formal and informal regulations of social interactions which we could call the norms of human culture. In some sense human culture consists of normative situations of various types. If the person is taking the bus obviously, some standard way of acting is expected: she should buy a ticket and not disturb other passengers. Normative situations are related to social roles and rules: for example, the role of university professor is submitted to some official guidelines and rules, while the patterns for the role of students are different. These regulations and norms are impersonal; they are not related to the individual characters of professors and students.

Elsewhere (Veresov and Veraksa Citation2022) we have discussed three ways for the child to master the rules in the normative situation. The child: (1) learns the rule by trial and error; (2) learns the rule by observing the behaviour of an adult (or other children) and then reproducing it through imitation; and (3) the child follows a direct instruction from an adult or another child. This corresponds with Vygotsky’s conception of the stages of cultural development of the child – the first way corresponds to the stage of the ‘natural behaviour’; the second and the third ones are at the stage of external operations (Vygotsky Citation1994, Citation1998).

The concept of normative situation might be a powerful analytical tool to disclose the process of development. People interact, and normative situations provide the stability of these interactions. In real life, within the concrete social environment, the first one to introduce the child to the standard way of following the rules must be someone experienced in being in a normative situation (an adult or other children). First, the child masters these requirements in the process of communication with other people, and then acts independently. This is in line with the process, described by Vygotsky, who writes that in the process of development, ‘the child begins to apply to himself those forms of behaviour that adults usually apply to him’ (Vygotsky Citation1997, 88).

In developed forms of play (role play), children follow the rules, not only corresponding to their role (Vygotsky Citation2016), but they also follow the rules which regulate actions and interactions in the role. These types of rules and regulations come from the real social world, from the social environment. Research demonstrates that when playing role games, children can often be seen approaching their peers and correcting their actions. Thus, in role play, children ‘continually turn to each other with amendments (“Is this what the doctor does? But the driver is driving the car in another way!”)’ (Elkonin Citation1978, 152). Lewis and Boucher also highlighted this aspect of children’s interactions in play: ‘Such amendments and clarifications are introduced into the play by the children themselves, arguing with each other and clarifying the words and actions of the characters depicted: ‘Why are you going straight to the doctor? You must first sign up at the reception and then sit in line … ’ (Lewis and Boucher Citation1997, 110). The natural form of a child’s behaviour begins to change and is shaped by cultural norms. Thus, as we can see, an imaginary situation is created, in which play actions are guided by a system of normative situations. Each normative situation is defined through external and hidden rules.

Elsewhere (Veresov and Veraksa Citation2022) we suggested that ‘the normative situation in a child’s play is another important component, along with an imaginary situation, roles, rules, and play actions, which allows investigating the role and the contribution of a child’s play to development’ (8). The genetic-analytical model of analysis presented above allows us to take the next step. In his article on play, Vygotsky did not consider play as a specific social situation through which the roles, rules, and play actions might be analysed. The genetic-analytical model, which presents the social situation as a specific event within the social environment, allows us to clarify the place of the normative situation in the general dynamic structure of play. The normative situation is a part of the social situation that occurs in play. The doctor’s visit play does not only reproduce a social situation from real life, but also reproduces normative situations regulating the actions of the doctor and the patient. By reproducing normative situations, the conditions appear for the child to gradually assimilate these norms which will become internal regulators of her play actions and real-life actions as well.

The identification of normative situations as an integral part of social situations arising in play allows, we believe, a deeper exploration of the role of play in development. First, by creating play actions in accordance with normative situations, the child makes a transition from spontaneous play actions and forms of behaviour to cultural forms of behaviour, which first emerge as social forms of behaviour (in accordance with normative rules) and gradually become individual cultural forms. This aspect of development, therefore, might be seen as a concrete manifestation of the law of sociogenesis of higher forms of behaviour (Vygotsky Citation1998, 169). Second, normative situations as an integral part of social situations in play create conditions for the zones of proximal development (ZPD). For example, children may create situations in which they are not competent enough, which means they may not know the rules they are willing to follow. However, through cooperation or/and under guidance they gradually acquire the norms associated with the roles and imaginary situations, and therefore they can navigate and move forward within the ZPD.

However, creating the conditions for development is necessary but not sufficient. Development does not occur automatically when the most favourable conditions are created, that is when a social plane of development and inter-psychological form are formed (Vygotsky Citation1997, 106). This means, as we discussed in the previous section of this article, that not every social situation automatically leads to an individual (intra-psychological) plane of development. For this to happen, a social situation of development must arise within a given social situation. There is something that leads (or does not lead) to a particular social situation of development within the social situation – this ‘something’ is the child’s perezhivanie.

Social situation of development and perezhivanie in play

As shown in a previous section of this paper, in cultural-historical theory, SSD is a specific and unique relationship between the child and the social environment. Identifying the social situation of development is the first task with which analysis must begin (Vygotsky Citation1998, 198). If we consider play as an imaginary situation in which micro-social situations of development might occur, this concept allows for a deeper understanding of play because children’s play is never repeated. For example, when playing a family or a hospital, children never play the same story; there are always new variations in roles and actions. This means that the imaginary situation does not remain the same either. At each moment of play, therefore, a distinctive and unique relationship between the child and the social environment is realized. On the other hand, the concept SSD allows us to better understand why the developmental potential of the social situation that exists in play is realised or remains unreleased. Even the most favourable play context, which creates a rich social situation – and even the emergence of a social plane of development and the discrepancy between the visible field and the field of meanings – may not lead to changes in the child’s development, if there is no social situation of development. The social situation of development may or may not arise in the play context. The perezhivanie of the child is what makes the micro-social situation of development arise (or not arise) within the social situation of play.

The social situation of development is, in Vygotsky’s view, the unique relationship between the child and the social environment (social situation). The uniqueness is determined by perezhivanie – that is, by how exactly and in what way different aspects of the social situation are refracted in the child’s mind. Being in the same social situation of play, different children, depending on their individual characteristics, refract the main components of this social situation differently; even more, some aspects of the social situation of play are refracted and some are not refracted at all. This explains why different children see the same imaginary situation differently. Roles, rules, and play actions are therefore also refracted in the child’s mind in a unique way, determining the child’s attitude towards the whole social situation in the play context. In this way, within the same social situation of play, specific relationships between different children and the social situation are formed (or not formed) and therefore social situations of development arise (or do not arise).

Conclusions and final comments

In this article, based on Vygotsky’s recently published and previously unknown work (Vygotsky Citation2016, Citation2019, Citation2021), we examine the opportunities where the genetic-analytical model can function as a tool of cultural-historical analysis of the role of children’s play in psychological development. To explore the complexity of child’s play we use the metaphor of matryoshka. We believe this metaphor is important as an illustration of the complexity of the interrelations of several situations related to play − 1) the imaginary situation as the main distinguishing feature of child’s play, 2) the social situation which appears within the imaginary situation as a certain event (or series of events) in the plot and the narrative of the role play, 3) the normative situation as a component of the social situation which represents the normative/regulatory aspect of the social situation, and 4) the social situation of development which might arise within the social situation depending on how the social situation is refracted through the prism of child’s perezhivanie.

Our goal was to show that the inclusion of two new concepts – the concept of social situation and normative situation – allows us to more deeply explore the dialectics of development in the tradition of cultural-historical research of play. The social environment becomes a real and acting source of development; it begins to ‘work’ as a source of development only if the child is a part (participant) of a particular event (social situation) and if a social situation of development is formed in that social situation. The social situation of development is the sphere where the developmental potential of the social situation might be actualised.

Children’s play can be seen as a social situation (or a series of social situations) of a special kind, occurring within an imaginary situation. Child’s play is the source of development (Vygotsky Citation2016) and what we try to show in this article is that it comes to ‘work’ as a source of development when the child acts and interacts within the social situation/s of play and refracts the social situation through his or her perezhivanie, thereby creating the unique relationship with the social situation – the social situation of development. Play creates the ZPD (Vygotsky Citation2016), and what we try to show in this paper is that normative situations in play create the conditions for the child to move from collective forms of cultural behaviour to individual forms that, according to Vygotsky (Citation1994), represent the cultural aspect of the development of higher psychological functions of a child.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Plural form of perezhivanie.

References

- Cole, M. 1997. Cultural Psychology: A Once and Future Discipline. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Dafermos, M. 2018. Rethinking Cultural-Historical Theory: A Dialectical Perspective to Vygotsky. Singapore: Springer.

- Daniels, H., M. Cole, and J. V. Wertsch. 2007. The Cambridge Companion to Vygotsky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Duncan, R. M., and D. Tarulli. 2010. “Play As the Leading Activity of the Preschool Period: Insights from Vygotsky, Leont’ev, and Bakhtin.” Early Education and Development 14 (3): 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1403_2.

- Edwards, S. 2011. “Lessons from ‘A Really Useful Engine’™: Using Thomas the Tank Engine™ to Examine the Relationship Between Play As a Leading Activity, Imagination and Reality in Children’s Contemporary Play Worlds.” Cambridge Journal of Education 41 (2): 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2011.572867.

- Elkonin, D. B. 1978. Psikhologiya Igry [Psychology of Play]. Moscow: Pedagogika.

- Elkonin, D. B. 2005. “The Psychology of Play.” Journal of Russian and East European Psychology 43 (1): 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10610405.2005.11059245.

- Elkoninova, L., and N. Bazhanova. 2007. “Forma I Material Suizetno-Rolevoi Igri Doshkolnikov” [The Form and the Material of Preschooler’s Make-Believe Play]. Cultural-Historical Psychology 3 (2): 2–11. https://psyjournals.ru/en/journals/chp/archive/2007_n2/Elkoninova.

- Fleer, M. 2009. “A Cultural-Historical Perspective on Play: Play As a Leading Activity Across Cultural Communities.” In Play and Learning in Early Childhood Settings: International Perspectives, edited by I. Pramling-Samuelsson and M. Fleer, 1–17. Netherlands: Springer.

- Fleer, M. 2014. Theorizing Play in the Early Years. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Holzman, L. 2009. Vygotsky at Work and Play. New York: Routledge.

- Kravtsova, E. 1999. “Preconditions for Developmental Learning Activity at Pre-School Age.” In Learning Activity and Development, edited by M. Hedegaard and J. Lompscher, 220–245. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press.

- Kravtsova, E. 2004. “Metodologicheskoye Znachenie Vzgliadov D. B. Elkonina Na Detskuyu Igru” [Methodological Significance of Elkonin’s Approach to Child’s Play]. Mir Psihologii i Psihologia v Mire 1 (37): 68–76.

- Lewis, V., and J. Boucher. 1997. Manual of the Test of Pretend Play. London: Harcourt Brace.

- Lindqvist, G. 1995. “The Aesthetics of Play: A Didactic Study of Play and Culture in Preschools.” PhD diss., Uppsala University. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED396824.

- Miller, R. 2011. Vygotsky in Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Veer van der, R. 2008. “Multiple readings of Vygotsky.” In The Transformation of Learning: Advances in Cultural-Historical Activity Theory, edited by B. van Oers, W. Wardekker, E. Elbers, and R. van der Veer, 20–37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Veraksa, N., and A. Bulitcheva. 2003. “Razvitie Umstvennoi Odarennosti v Doshkilnom Vozraste” [Development of Intellectual Giftedness in Pre-School Age]. Voprosy Psihologii 6:17–31.

- Veraksa, N., N. Veresov, A. Veraksa, and V. Sukhikh. 2020. “Modern Problems of Children’s Play: Cultural-Historical Context.” Cultural-Historical Psychology 16 (3): 60–70. https://doi.org/10.17759/chp.2020160307.

- Veresov, N. 2016. “Duality of Categories or Dialectical Concepts?” Integrative Psychological and Behavioural Science 50 (2): 224–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9327-1.

- Veresov, N. 2017. “The Concept of Perezhivanie in Cultural-Historical Theory: Content and Contexts.” In Perezhivanie, Emotions and Subjectivity: Advancing Vygotsky Legacy, edited by M. Fleer, F. G. Rey, and N. Veresov, 47–70. Singapore: Springer.

- Veresov, N. 2019. “Subjectivity and Perezhivanie: Empirical and Methodological Challenges and Opportunities.” In Subjectivity within Cultural-Historical Approach, edited by F. G. Rey, A. M. Martinez, and D. Goulart, 61–86. Singapore: Springer.

- Veresov, N. 2020. “Discovering the Great Royal Seal: New Reality of Vygotsky’s Legacy.” Cultural-Historical Psychology 16 (2): 107–117. https://doi.org/10.17759/chp.2020160212.

- Veresov, N., and M. Barrs. 2016. “The History of the Reception of Vygotsky’s Paper on Play in Russia and the West.” International Research in Early Childhood Education 7 (2): 26–37. https://doi.org/10.4225/03/584e716cbdb75.

- Veresov, N., and M. Fleer. 2016. “Perezhivanie as a Theoretical Concept for Researching Young Children’s Development.” Mind, Culture and Activity 23 (4): 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2016.1186198.

- Veresov, N., and N. Veraksa. 2022. “Digital Games and Digital Play in Early Childhood: A Cultural-Historical Approach.” Early Years. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2022.2056880.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Manchester: Harvard University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1993. The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky: The Fundamentals of Defectology (Abnormal Psychology and Learning Disabilities). Vol. 2. New York: Springer.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1994. “The Problem of the Cultural Development of the Child.” In The Vygotsky Reader, edited by R. van der Veer and J. Valsiner, 57–72. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1997. The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky: The History of the Development of Higher Mental Functions. Vol. 4. New York: Springer.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1998. The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky: Child Psychology. Vol. 5. New York: Springer.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 2001. Lektsii Po Pedologii [Lectures on Pedology]. Izevsk: Izdatelstvo Udmurdskogo Universiteta.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 2016. “‘Play and Its Role in the Mental Development of the Child (With Introduction and Afterword by N. Veresov, and M. Barrs).’ Translated by N. Veresov and M. Barrs.” International Research in Early Childhood Education 7 (2): 3–25. https://doi.org/10.4225/03/584e715f7e831.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 2019. L.S. Vygotsky’s Pedological Works: Volume 1. Foundations of Pedology. Singapore: Springer.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 2021. L.S. Vygotsky’s Pedological Works: Volume 2. The Problem of Age. Singapore: Springer.

- Wertsch, J. V. 1985. Vygotsky and the Social Formation of Mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wertsch, J. V. 1998. Mind As Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.