Abstract

The human resource (HR) architecture model has been influential in the field of strategic human resource management since its inception. This study offers a comprehensive review on this model’s contributions to management literature by analyzing 205 journal articles which have substantively cited the three classic articles on HR architecture. Specifically, we develop a framework along two dimensions (that is, the content and the use of the HR architecture model) based on which we systematically discuss the current findings in terms of the theoretical application, empirical validation, and extension and critiques of the HR architecture model. Based on the review, we identify the research gaps in the literature of HR architecture, propose important future research directions and discuss their implications.

1. Introduction

As organizations seek to efficiently manage their human capital (HC) to achieve competitive advantages, the HR architecture model (Lepak & Snell, Citation1999) has been of significant interest since its publication. The HR architecture model views a firm as a portfolio of HC and suggests that different forms of HC should be managed differently in terms of workers’ employment modes, employment relationships, and HR configurations. By taking into account the coexistence of multiple sets of HR practices within one organization, it highlights the limitations of a ‘one size fits all’ approach for strategic human resource management (SHRM) (Wright et al., Citation2001). The model has been described as ‘the first thorough depiction of the differentiated nature of HR systems within organizations’ (Wright et al., Citation2018, p. 150) and has become ‘the most prominent conceptual model’ in the individual differentiation perspective of SHRM (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2014, p. 308). Since its inception, the HR architecture model has substantially influenced later SHRM research (Lengnick-Hall et al., Citation2009; Takeuchi et al., Citation2018).

Despite its widely acknowledged importance and extensive citation, no study has systematically assessed how the HR architecture model has impacted on and been developed by the subsequent literature. Further, a number of important research questions derived from the model remain unanswered. For example, Boon et al. (Citation2018, p. 47) pointed out that ‘researchers have not examined the firm performance effects of this approach’. To fill these voids, the present study aims to offer a comprehensive 20-year review of the HR architecture model.

By reviewing articles citing the three classic HR architecture articles (Lepak et al., Citation2003; Lepak & Snell, Citation1999, Citation2002), we make the following theoretical contributions. First, to assess the status of its development and the impact it has generated, we provide a comprehensive review of how the HR architecture model has been applied, validated, extended and critiqued. Second, based on this review, we propose important future research directions for further developing the model. Overall, this review examines in depth how Lepak and his colleagues’ work on the HR architecture contributes to the SHRM field and provides avenues for future research.

2. The HR architecture model

Drawing upon transaction cost economics, human capital theory and the resource-based view, Lepak and Snell (Citation1999) developed a theoretical model of HR architecture. The main thesis of the model is summarized as follows:

Organizations may implement different employment modes, employment relationships, and HR configurations to manage employee groups with different HC. That is, the HC determines (the appropriateness of) employment modes, employment relationships, and HR configurations. HC can be classified in terms of two dimensions: its value (i.e., the value-creating potential of HC and its associated costs) and uniqueness (i.e., the specificity of the particular HC to the firm). The extent of the value and uniqueness of HC can vary, which plays out in various combinations. These combinations place imperatives on the firm’s strategic choices concerning employment modes, employment relationships, and HR configurations. Thus, the four kinds of HC fall into the four quadrants (i.e., types) in the HR architecture model.

Specifically, for HC with a high value and uniqueness, organizations (should) adopt an ‘internal development’ employment mode (i.e. knowledge-based employment in Lepak & Snell, Citation2002) with ‘organization focused’ employment relationships and a ‘commitment-based’ HR configuration (Quadrant 1, hereafter Q1). For HC with a high value and low uniqueness, organizations (should) adopt an ‘acquisition’ employment mode (also termed job-based employment in Lepak & Snell, Citation2002) with a ‘symbiotic’ employment relationship and a ‘market based’ HR configuration (also called a productivity-based HR configuration in Lepak & Snell, Citation2002) (Quadrant 2, hereafter Q2). For HC with a low value and uniqueness, organizations (should) adopt a ‘contracting’ employment mode (also referred to as contractual work arrangements in Lepak & Snell, Citation2002) with a ‘transactional’ employment relationship and a ‘compliance’ HR configuration (Quadrant 3, hereafter Q3). Finally, for HC with a low value and high uniqueness, organizations (should) adopt an ‘alliance’ employment mode with a ‘partnership’ employment relationship and a ‘collaborative’ HR configuration (Quadrant 4, hereafter Q4).

The HR architecture model is complex in that it adopts a contingent configurational view, in contrast to the ‘best practice’ perspective which argues that one set of HRM practices is appropriate for all organizations and employees. An effective HR architecture requires congruence among the employment mode, employment relationship, and HR configuration.

The HR architecture is dynamic as, over time, the value and uniqueness of HC are not stable and are subject to changes in the external environment. This corresponds to the associated HR architecture evolving across the quadrants. The organization can also implement strategic investments to increase the value and/or uniqueness of its HC, which, likewise, may lead to the HR architecture moving across the quadrants.

In a subsequent study, Lepak and Snell (Citation2002) empirically examined the associations among HC, employment modes, and HR configurations, providing initial empirical support for the HR architecture model. They developed valid and reliable scales to measure the value and uniqueness of HC and ascertain particular HR configurations. Later on, Lepak et al. (Citation2003) explicated that theoretically, employment modes could contribute to organizational performance by increasing an organization’s employment flexibility and such positive effects were contingent on factors such as environmental dynamism and technological intensity. Moreover, they put forward that multiple employment modes could interact with each other in impacting firm performance, which is consistent with the complexity of the HR architecture. Their empirical test, in general, provided support for these arguments.

3. Methods

The aim of this review is to clearly describe the development of the HR architecture literature, assess its contributions to management literature and identify future research directions. We base our analysis on the literature citing the three classical articles on the HR architecture: Lepak and Snell (Citation1999, Citation2002) and Lepak et al. (Citation2003). We searched for articles citing any of these articles in the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) database of the Web of Science for a 20-year period since 1999. By June 30, 2019, we obtained a total of 1109 articles after excluding duplications.

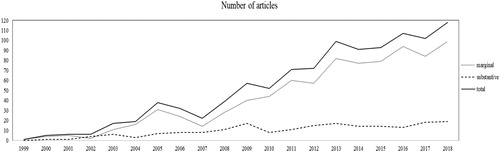

From 1999 to 2019, the average annual output of such articles was about 50 and the number of citations has steadily increased (). In the past five years, the annual number of articles has reached or exceeded 100. The 2019 figure comprises a six-month period only (62 articles). Among the three classic HR architecture articles, Lepak and Snell (Citation1999) attracted the most citations, with a total of 802. This is a high citation number compared with other highly-cited articles in top-tier management journals (c.f., Judge et al., Citation2007).

Figure 1. The annual number of articles citing the three classic HR Architecture articles (1999-2018).

These articles appeared in 329 journals. The top five journals publishing the most articles are International Journal of Human Resource Management (142), Human Resource Management (98), Human Resource Management Review (44), Journal of Management (44) and Personnel Review (43). Articles were also published in prestigious journals in other fields, such as business ethics (e.g. Journal of Business Ethics), public administration (e.g. Public Management Review), and accounting (e.g. Journal of Accounting Research). While the HR architecture model’s influence was mostly on management, especially human resource management, it is evident that its impact has extended widely to other fields.

In total, 2,145 scholars have cited any of the three classic HR architecture articles. The top ten scholars, ranked by the number of articles, are David P. Lepak, Nicky Dries, Patrick M. Wright, Alvaro López‐Cabrales, Ramón Valle-Cabrera, Yaping Gong, Inmaculada Beltrán-Martín, Kaifeng Jiang, Mark L. Lengnick-Hall, and Vicente Roca-Puig.

We differentiated between studies that substantively cited the classical HR architecture articles (i.e. Lepak et al., Citation2003; Lepak & Snell, Citation1999, Citation2002) and those that only marginally cited them. Those which cited the articles only once were coded as marginal citations (Kacmar & Whitfield, Citation2000). For those citing the classic HR architecture articles multiple times, we assessed whether the HR architecture model played a significant role in a focal article with the following criteria: (1) the article builds on Lepak and Snell (Citation1999, Citation2002), and/or Lepak et al. (Citation2003) as theoretical foundations for its hypothesis or proposition development; or (2) it reviews or comments on Lepak and Snell (Citation1999, Citation2002), and/or Lepak et al. (Citation2003); or (3) it discusses the research implications of the focal article for the HR architecture model. Articles that met any of these criteria were coded as substantive citations, others being marginal citations. As a result of the assessment, we identified 205 substantive citations (18%) and 904 marginal citations (82%). As shown by the dotted line in , the annual number of marginal citations has increased steadily over the years, which drives the number of total citations. In comparison, the dashed line reveals that the annual number of substantive citations is relatively stable.

We coded the substantively citing articles with a framework that was created along two dimensions: the content and the use of the HR architecture model (c.f., Anderson, Citation2006; Anderson & Lemken, Citation2019; Wry et al., Citation2013). That is, first, we coded which major idea(s) of the HR architecture model, as reviewed in Section 2, was/were used in the article. Second, we coded whether the use of the HR architecture model in the article fell into one of the three types: theoretical application, empirical validation, and extension and critiques. Cheng et al. (Citation2011) identified three generic stages of new theory development: theory conception and articulation, empirical testing and refinement, and theory affirmation and extension. Adapting Cheng et al. (Citation2011)’s ideas, we have developed three types of use to describe how researchers engage with the HR architecture model. To be specific, they are:

theoretical application, which refers to whether the HR architecture model is adopted by the researchers to develop their own conceptual ideas, such as propositions. This type of use of the model represents its acceptance, diffusion, and application;

empirical validation, meaning whether a subsequent study employs empirical data to test the validity of the HR architecture model, for instance, through hypothesis testing. This type of use is critical for the consolidation and revision of the model;

critiques and extension, which indicates whether the HR architecture model is critiqued, refined, or extended. With this type of use, usually some part of the model is modified, or sometimes the assumptions underlying the whole model are critically challenged or overturned in the form of a paradigm shift (Kuhn, 1970). This type of use is necessary for the development of the model.

Such a classification of the literature has often been adopted, sometimes implicitly, in other literature reviews (e.g. Anderson & Lemken, Citation2019; Colquitt & Zapata-Phelan, Citation2007; Wright et al., Citation2001). For instance, Wright and McMahan (Citation1992) provided a comprehensive review on how theories such as the resource-based view had been applied to SHRM, and emphasized the need for ‘rigorous empirical tests’ (p. 315), and ‘further development and explication’ (p. 316) of these theoretical models.

Based on the framework described above, the first two authors analyzed these substantively citing papers in detail, coding them independently. The two coders had a pilot test on ten articles. Any discrepancies in coding were discussed by the research group before reaching a consensus. summarizes the coding results. The first column refers to the contents of the HR architecture model, including HC and its management, individual quadrants, complexity, dynamics, and effects of employee mode on firm performance via flexibility. The first row corresponds to the use of the HR architecture model, including theoretical application, empirical validation, and critiques and extensions. Each of the other cells indicates the number of articles coded to the focal cell and provides some representative articles. We present our findings from the analysis of the substantive citations below.

Table 1. Coding results of the substantively citing literature.

4. Findings

Among studies which substantively cited any of the three articles of interest, the number of those taking a systematic view of all four quadrants (N = 93) is higher than the number of those focusing on an individual quadrant (N = 45). This suggests that researchers are more interested in the systematic examination of the HR architecture, rather than the management of a single employee group, which is aligned with the premise of the HR architecture model.

4.1. A systematic approach toward the HR architecture

4.1.1. Theoretical applications

The HR architecture model posits that an organization implements diverse HRM subsystems to manage different employee groups based on their HC. We found the subsequent theoretical research interpreted this relationship in two different ways. On one hand, some researchers viewed the model as descriptive, that is, it describes and predicts how the forms of the HC of employee groups impact firms’ choices of their management. On the other hand, some others viewed it as normative, that is, the HR architecture model was interpreted to posit that an organization ‘should’ implement different HRM subsystems for employee groups with different kinds of HC to increase organizational performance. This line of research focused on the fit between HC and firms’ HRM and the effect of the fit on firm performance. More than twice the number of articles have been produced on the normative theme than the descriptive one (26 versus 12). Below we review the theoretical applications of the HR architecture model adopting each approach.

4.1.1.1. Theoretical applications of the descriptive approach

We found 12 articles arguing that HC influences the adoption of HRM and thus causes the differentiation of HRM among employee groups with varying kinds of HC (e.g. Yanadori & van Jaarsveld, Citation2014; Zheng, Citation2016). For example, focusing on high performance work practices (HPWPs), Yanadori and van Jaarsveld (Citation2014, p. 508) theoretically acknowledged that ‘management strategically differentiates HPWPs among employee groups considering the differences in the expected contributions of different employee groups.’ This core idea was also adopted to justify the propositions that across employee groups with different HC, individual HR practices differ, such as pay for performance systems (Bayo-Moriones et al., Citation2013) and career development (Baruch & Rousseau, Citation2019).

Besides, some researchers utilized the HR architecture model as a framework to offer post-hoc explanations for their insignificant empirical results. They argued that these insignificant results were due to the sampling of a single employee group. Such a treatment neglects the differentiated HRM for multiple employee groups (Nieves & Quintana, Citation2018; Uen et al., Citation2009) and may result in the potential problem of range restrictions in the empirical data (Chen, Citation2018), which can reduce the power of the empirical testing.

Some other researchers indicated that future research should take into account the role of the differentiated HRM within organizations, even though they did not include it in their own studies (Giauque et al., Citation2019; Vicente-Lorente & Zúñiga-Vicente, Citation2018; Zikic, Citation2015). Based on such arguments, they called for future considerations about the differences among the various employee groups within one organization.

4.1.1.2. Theoretical applications of the normative approach

The majority of the papers adopting this approach utilized the idea that the fit between HC and HRM could have an impact on organizational performance. These studies acknowledged that to achieve a better performance firms should apply different HRM modes to different employee types based on their HC (e.g. Chadwick & Dabu, Citation2009; Hansen, Güettel, & Swart, 2019; Jiang et al., Citation2012). For instance, Fernandez et al. (Citation2016, p. 207) argued that organizations should apply different HRM to ‘optimise the efficiency of all employees’. Similarly, Gelens et al. (Citation2013, p. 345) indicated that ‘it is believed that organizational efficiency increases when different employee groups (i.e. different in their value and uniqueness) are managed according to different employment modes’. This concurs with Lepak et al. (Citation2004) who emphasized the importance of differentiated HRM for employees with different HC to make optimal contributions to the firm.

Specifically, based on the HR architecure model, researchers pointed out that firms should make strategic decisions on the internal or external allocation of jobs (e.g. Anagnostopoulos & Siebert, Citation2015; Klaas, Citation2008). The decision about when a certain type of work ‘should be performed internally and when it should be outsourced’ (Klaas, Citation2008, p. 1501) has received much attention in the strategic HR literature, and HR architecture serves as a theoretical foundation for these studies to develop their theories. Further, it has been argued that HRM should strategically distinguish core from peripheral employees, helping them contribute to firms in different ways and thus building the organization’s competitive advantage (e.g. Beatty et al., Citation2003; Delery & Roumpi, Citation2017; Dries et al., Citation2012). To take one example, Delery and Roumpi (Citation2017) followed the propositions by Lepak and Snell (Citation2002) to argue that HRM practices should distinguish among employee groups to generate mobility constraints in order to retain the core HC resources.

4.1.2. Empirical validations

The earliest empirical validation of the HR architecture model was by Lepak and Snell (Citation2002), the creators of the model. It was then followed by nearly 20 studies empirically testing the core ideas of the HR architecture model (see ). In total, we found 18 empirical studies which tested the effect of HC on HRM, including 15 supporting the model and three partially supporting it. It is surprising to find no empirical study directly testing the effect of the fit between HC and HRM. This is in contrast to the number of theoretical studies, where more papers were concerned with the fit effect on organizational performance (i.e. the normative approach) than the idea that HC impacts the HRM (i.e. the descriptive approach).

Table 2. Empirical results from testing the effects of HC on HRM.

4.1.2.1. Examinations of the effect of HC on HRM

We found 15 empirical studies supporting the proposition that the design of HRM is influenced by the HC of employee groups. Empirical evidence for the effects of HC on HRM subsystems were found in a variety of geographic regions, including North America (e.g. Schmidt, Pohler, et al., Citation2018; Yanadori & Kang, Citation2011), Europe (e.g. Benzinger, Citation2016; Ramirez & Fornerino, Citation2007; Urtasun & Núñez, Citation2012), Oceania (e.g. McKeown & Lindorff, Citation2011), and Asia (e.g. Vyas & Zhu, Citation2017); in diverse industries, such as tourism (Schmidt, Willness, et al., Citation2018), the armed services (Clinton & Guest, Citation2013), high technology (Yanadori & Kang, Citation2011), manufacturing, education, and finance (Benzinger, Citation2016); in both private firms (e.g. Ferner & Almond, Citation2013; Lepak & Snell, Citation2002; Okay-Somerville & Scholarios, Citation2019) and public organizations (McKeown & Lindorff, Citation2011; Vyas & Zhu, Citation2017); and in both quantitative (e.g. Clinton & Guest, Citation2013; Okay-Somerville & Scholarios, Citation2019; Urtasun & Núñez, Citation2012) and qualitative studies (e.g. McKeown & Lindorff, Citation2011; Vyas & Zhu, Citation2017). In sum, the existing research revealed that the HR architecture model was generally valid in various geographic regions, industries, and organizations when tested with different methods.

Furthermore, these studies showed that some specific HRM practices were strategically designed to be different for various employee groups based on their HC. Such HRM practices included the retention strategy (Gardner, Citation2005), compensation (Gowan & Lepak, Citation2007; Hong & Honig, Citation2016; McDonnell et al., Citation2016), career management (De Vos & Dries, Citation2013; Urtasun & Núñez, Citation2012), pay and performance management systems (Ferner & Almond, Citation2013), organizational socialization tactics (Benzinger, Citation2016), skill development (Okay-Somerville & Scholarios, Citation2019), and training (Melián-González & Verano-Tacoronte, 2004; Vyas & Zhu, Citation2017).

Despite the prevailingly positive evidence, three studies only partially supported the idea that HRM is distinguished according to the strategic value and uniqueness of the HC of employee groups. Lepak and Snell (Citation2002) made the initial effort to examine the relationship between HC and HRM. While most of their results received support for the hypotheses derived from the HR architecture model, the empirical results contradicted their theoretical predictions for the management of workers with high uniqueness and high value (i.e. core employees). They found that in addition to knowledge-based employment (as proposed by the HR architecture model), job-based employment and contractual work arrangements were also applied to these core employees. Similarly, Melián-González and Verano-Tacoronte (Citation2006) found considerable similarities, rather than dissimilarities, between the HRM implementation for employees high in both value and uniqueness and employees with a high value but a low uniqueness. In addition, some HR practices did not show any variance based on the strategic characteristics of employees’ HC. For instance, Ramirez and Fornerino (Citation2007) found that compensation practices were used in the same way among companies with different levels of techonology (which can be viewed as an indicator of HC).

4.1.2.2. Examinations of the effect of the fit between HC and HRM on organizational performance

The fit effect on performance was implicitly held in the HR architecture model. Lepak and Snell (Citation1999, p. 45) encouraged researchers to “examine whether a firm’s emphasis on one mode of employment for all employees versus the use of multiple modes for different groups of human capital impacts firm performance.” However, despite this call, we found that no study so far had empirically examined the effect of the fit between HC and HRM on organizational performance.

What are relevant, though indirectly, may be those exploring the influences of the fit between HC and HRM on employee attitudes and behaviors, which may further affect organizational performance (see ). While some studies did not find any statistically significant effect of the fit on employee wellbeing (Clinton & Guest, Citation2013; Okay-Somerville & Scholarios, Citation2019) or employment opportunities (van Harten et al., Citation2017), others revealed that the fit between HC and HRM can elicit positive employee attitudes and behaviors, such as increasing employees’ satisfaction with their performance management (Decramer et al., Citation2013) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (Schmidt, Willness, et al., Citation2018), and lowering their turnover intentions (Schmidt, Pohler, et al., Citation2018).

Table 3. Empirical results from testing the effects of the fit between HC and HRM on employee attitudes and behaviors.

In sum, the current studies have provided some preliminary evidence for the benefit of the fit between HC and HRM on employee outcomes. However, such evidence only has indirect implications for organizational performance. It is surprising that no study has offered a direct empirical validation of the effect of the fit on organizational performance. This general lack of empirical effort is in stark contrast to the fact that the theoretical applications of the HR architecture model are largely based on the fit between HC and HRM.

4.1.3. Extension and critiques

4.1.3.1. Extension of the HR architecture model

Quite a few studies extended the HR architecture model. Our review shows that the extension was made along two lines: one was by focusing on the role of contexts and the other by offering a miscellany of complementary theoretical perspectives.

In exploring the role of contexts, Kulkarni and Ramamoorthy (Citation2005) attended to the environmental uncertainties. They expanded the HC dimensions of value and uniqueness (i.e. firm specificity in the original model) by adding a usage specificity dimension (i.e. whether the HC is for a particular use or application in a firm) and created eight typologies reflecting different HC attributes and environmental uncertainties. Following this, they proposed corresponding employment modes organizations should adopt. Similarly, Hansen et al. (Citation2019) considered the role of environmental dynamics and proposed specific HR architectures that enabled organizational exploration, exploitation, and ambidexterity in high velocity, moderately dynamic and heterogeneous environments, respectively.

Other studies examined (parts of) the HR architecture model in different types of organizations, such as family firms (Jennings et al., Citation2018), emerging organizations (Bryant & Allen, Citation2009), nonprofit organizations (Ridder et al., Citation2012; Citation2012) and multinational corporations (MNCs) (Morris et al., Citation2016). The assumption is that these types of organizations possess unique features which the original HR architecture model has not taken into account. For instance, Morris et al. (Citation2016) investigated the global talent management in MNCs. Recognizing that, in a global context, employees may possess multiple forms of HC which go beyond the firm-specific level, they added location specificity to firm specificity and used these two dimensions to create four types of HC: local, subsidiary, corporate, and international HC. These researchers argued that the distinct strategy of an MNC determines what the best HC portfolio is. They further proposed HR practices at the individual, unit, and firm levels that aimed to support the HC portfolios.

Studies applying the model in novel contexts also offered country-specific insights. Two studies focused on the Chinese context. The first (Zhou et al., Citation2012) proposed that, due to the transitional nature of the Chinese economy, Chinese firms would deploy hybrid combinations of HR archetypes, rather than a single HR archetype, to achieve multiple organizational goals and to attain fit with macro-economic institutions. The second study (Liu et al., Citation2015) found that employees in a Chinese hotel were grouped by their HC value, but also by their guanxi (relationships) with the employer, which was unique to the Chinese context. Another study (Jayasinghe, Citation2016) carried out in Sri Lanka noted that in emerging countries it cannot be presumed that all organizations have met basic employee needs (i.e. core labor standards). Hence, different from developed countries, voluntary labor code adoption should be regarded as an important HR investment here.

While the studies above have enriched our understanding of the HR architecture model by exploring various novel contexts, other studies have offered alternative perspectives which complement the human capital theory and the resource-based view in the original HR architecture model to explain firms’ choices of HC allocation and development. One perspective is the social capital theory. Kang et al. (Citation2007) noted that the HR architecture model only examined how firms manage HC, which is representative of the knowledge stock of a firm, but did not adequately address how they manage social capital, which is representative of ‘the knowledge flows across different employee cohorts’ (p. 237). They developed two HR configurations – the so-called ‘relational archetypes’ – for managing the relationships of core knowledge employees with other employee groups. Along a similar line of reasoning, Kase and Zupan (Citation2009) examined individual employees’ structural position in knowledge networks (i.e. their social network), in addition to their HC value and firm specificity, to explain why firms internalized these employees’ employment and whether it was justified.

Besides, Chadwick and Dabu (Citation2009) offered a rent-based view to explain how human resources help firms to gain competitive advantage. They maintained that human resources could create traditional Ricardian rents, nontraditional Ricardian rents, and entrepreneurial rents. Distinctive HR systems were needed to support firms’ simultaneous (although to variable degrees) pursuit of the three types of rents, concurring on the idea of HR architecture. Further refining the rent-based view, Chadwick (Citation2017) distinguished human capital value creation from value capture. This fined-grained distinction offers an opportunity to extend the original model by examining how firms can use HR practices to increase human capital value in use and leverage labor market frictions to capture human capital value – an idea echoed by Delery and Roumpi (Citation2017).

Alternatively, McIver et al. (Citation2013) offered a knowledge-in-practice (KIP) perspective. KIP refers to ‘the information and know-how involved in the sequences, routines, capabilities, or activity systems for conducting work in organizations.’ Both information and know-how can be a source of human capital value (p. 599). Using knowledge tacitness and learnability as two dimensions, four kinds of KIP were distinguished from each other. The authors argued that different employment modes, employment relationships and HR configurations might be required to best manage knowledge.

In addition to the studies which offered important complementary perspectives, a few studies extended the HR architecture model at a more incremental scale, by highlighting the role of firms’ overarching HR principle or philosophy in influencing firm’s adoption of HR policies and practices, which was not covered in the original model (Lepak et al., Citation2004; Monks et al., Citation2013; Yanadori & Kang, Citation2011).

In sum, these more or less substantial extensions showcase the potential for further refinement and development of the HR architecture model. Aside from the alternative theoretical perspectives which augmented the applicability of the HR architecture logic, exploration of novel environmental, organizational, and cultural contexts also offered significant promise. Indeed, macro-level factors such as institutions, cultures, and the types of market economies (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001) may constrain or construct the options organizations have in relation to their HRM (Paauwe & Boselie, Citation2007).

4.1.3.2. Critiques of the HR architecture model

Despite the support the model has received over the years, it was also challenged by some researchers. Many of these challenges were made by industrial relations scholars who called for a pluralist view when considering organizations’ employment mode decisions (e.g. Grimshaw & Rubery, Citation2005; Purcell et al., Citation2004; Rubery et al., Citation2003). Focusing on inter-organizational relationships, they argued that the HR architecture model was based on ‘two convenient assumptions’ (Rubery et al., Citation2003, p. 269): first, that the motivation of less-skilled employees was unimportant when pursuing organizational interests; and second, that the decision about internationalization or externalization was primarily based on internal factors such as HC. They were against the idea that there existed a hierarchy of knowledgeable individuals (Tempest, Citation2003) and claimed that the limitation of rational strategic calculation was that it overlooked the complex social and institutional contexts (Rubery et al., Citation2003) or even questioned whether the enactment of HR practices was necessarily strategic at all (Brandl et al., Citation2019). Rejecting these assumptions, they found supporting evidence that intra- and inter-organizational power relationships shaped a firm’s employment mode (Purcell et al., Citation2004) and HR practices (Ferner & Almond, Citation2013; Grimshaw & Miozzo, Citation2009).

Taken together, these studies suggest that the study of the HR architecture should be more deeply embedded in organizations’ internal and external relationships. They challenge the exclusive focus of the HR architecture model on internal factors such as HC in determining the choice of employment mode, employment relationships, and HR configurations.

4.2. Individual quadrants of the HR architecture model

While embracing the idea of differential HRMs in an organization, a substantial number of studies were devoted to single quadrants in the HR architecture model. That is, they focused on one particular combination of HC uniqueness and value, and its associated employment mode, employment relationship, and/or HR configuration (e.g. Gelens et al., Citation2015; Masters & Miles, Citation2002; Melián-González & Bulchand-Gidumal, Citation2009). Researchers made theoretical arguments (e.g. Hong et al., Citation2019; Nijs et al., Citation2014), empirical validations (e.g. Melián-González & Bulchand-Gidumal, Citation2009; Tlaiss et al., Citation2017), and extensions (e.g. Eckardt et al., Citation2018) about this particular quadrant.

Among the four quadrants of the HR architecture model, Q1 (i.e. HRM with HC high in both value and uniqueness) received overwhelming research attention (e.g. Boon & Kalshoven, Citation2014; Krausert, Citation2017; Lepak et al., Citation2007). The number of articles in this quadrant is much more than the sum of the studies on all three other quadrants. This focus on Q1 is likely due to the strategic importance of employees with high levels of value and uniqueness to organizations. According to Lepak and Snell (Citation1999), such employees are most instrumental to a firm’s competitive advantage. The great contributions to a firm’s performance by its core employees make the issues of talent management and a ‘talent war’ prominent in both academic communities and in practice (e.g. Collings & Mellahi, Citation2009; Sparrow & Makram, Citation2015).

4.3. Complexity of the HR architecture

Concerning the complexity of HR architecture, we found that researchers to date have paid attention to two major aspects: (1) the congruence of individual components within each quadrant (Palthe & Kossek, Citation2003; Tsai et al., Citation2009); (2) the interactions between multiple employment modes (or HR configurations) (e.g. Lepak et al., Citation2003; Stirpe et al., Citation2014). Yet, no study has investigated the interactions between multiple quadrants. Below we review the studies related to these two aspects in more detail.

4.3.1. Internal congruence within a quadrant

Although the overall HR architecture model is premised on the internal congruence or alignment between HC, employment mode, and HR configurations within each single quadrant, limited research has tested this idea. Tsai et al. (Citation2009) was one exception. This study empirically tested and found support for the predictions from the model that control-based HR practices were applied to employees in the external employment mode, while commitment-based HR practices were applied to those in the internal employment mode.

In line with the HR architecture model, Palthe and Kossek (Citation2003) proposed four types of congruence among HR strategies, employment modes and organizational subcultures. For example, they argued that an ‘internal development’ employment mode, a ‘make’ (vs. ‘buy’) HR strategy and an ‘employee-centered’ organizational subculture should be aligned with each other.

4.3.2. Interactions between multiple employment modes (or HR configurations)

Some researchers have explored how the individual components of the HR architecture model in different quadrants interact to impact firm performance. A majority of this research paid significant attention to the interactions between internalized and externalized employment modes, although using different terms to refer to them (Lepak et al., Citation2003; Roca-Puig et al., Citation2011; Roca-Puig et al., Citation2008; Stirpe et al., Citation2014). So far, the results on the effects of the interactions on performance have been inconclusive. For instance, Lepak et al. (Citation2003) found a complementary effect between the two employment modes. They indicated that while internalized employees could enable firms to effectively deploy the internal workforce to perform various tasks, the externalized ones could benefit firms with the ability to flexibly adjust the number and type of employees at their disposal. Thus, they proposed that the simultaneous use of the two employment modes could provide firms with coordination and resource flexibility and enhance the firm’s performance. However, some other studies found a substitution effect (Roca-Puig et al., Citation2008; Citation2011; Stirpe et al., Citation2014).

It was suggested that one of the reasons behind the incompatibility of the two modes was that the simultaneous utilization of internalized and externalized employees could come at a price of negative employee attitudes and behaviors (Broschak & Davis-Blake, Citation2006). In particular, the presence of externalized employees might be perceived as threatening the status and job security of internal employees, which would ultimately lead to worse firm performance (Banerjee et al., Citation2012; Vough et al., Citation2005). Taking the argument a step further, some researchers argued that the negative effect of the use of externalized employees on internal employees’ attitudes and behaviors had boundaries. One example was the aim of using externalized employees. Scholars (e.g. Way et al., Citation2010) found that when the use of externalized employees was to enhance the stability of internal employees, it reduced internal employees’ withdrawal behaviors; in contrast, when the aim was to reduce the labor cost, it increased their withdrawal behaviors.

There are also studies focusing on the interactions between other employment modes, such as alliance and knowledge-based employment modes (Kim & Sung-Choon, Citation2013; Lam, Citation2007). Consistent with Lepak et al. (Citation2003), positive interactions were found in these studies. For example, Lam (Citation2007) indicated that the collaboration between university partners and internal employees can benefit joint knowledge production.

As for HR practices, the existing research has offered warnings about some combinations of HR practices which produce a substitution effect on performance, such as putting together layoff and high-involvement work practices (Zatzick & Iverson, Citation2006), and layoff and ‘a war for talent’ (Cho & Ahn, Citation2018). However, there were also combinations which created a complementary synergy, such as commitment-oriented HRM and collaboration-oriented HRM (Zhou et al., Citation2013).

Taken together, the review reveals extensive research interest in the interaction between internalized and externalized employment modes and moderate interest in combinations of multiple HR configurations. However, no study has examined the interaction between different quadrants. We thus know little about how the coexistence of multiple quadrants within organizations impacts their performance.

4.4. Dynamics of the HR architecture

A considerable number of studies theoretically applied and found empirical support for the enhancing effect of HRM on HC. The studies offered a vast array of evidence for the positive association between high performance work systems (HPWS) and HC (e.g. Chang, Citation2015; Chang & Chen, Citation2011; Esch, Wei, & Chiang, 2018; Mansour et al., Citation2014; Schmidt, Pohler, et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2011). Other HR practices also received many examinations seeking to test their enhancement effect on HC, including developmental HRM practices (Cabello-Medina et al., Citation2011; López‐Cabrales et al., Citation2011), HC investment (Lin et al., Citation2017), training (Diaz-Fernandez et al., Citation2017; Nieves & Quintana, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2012), selection (López‐Cabrales et al., Citation2011; Nieves & Quintana, Citation2018), and appraisals and rewards (Diaz-Fernandez et al., Citation2017; López‐Cabrales et al., Citation2011). In particular, as Lepak and Snell (Citation1999) proposed, some studies found evidence supporting the proposition that different HRM practices should be applied to develop different types of HC (Jiang et al., Citation2012; López‐Cabrales et al., Citation2009). For example, Diaz-Fernandez et al. (Citation2017) found that firms could utilize training on job skills to nurture specialist HC, while training on future skills was effective to develop generalist HC.

While it was claimed that empirical evidence was offered which supported the existence of such an effect, the cross-sectional design of these studies constrained the inference of the direction of the effect. That is, it is not clear whether it was HRM that affected HC or the other way around. Another limitation of the current investigations into the dynamics of the HR architecture model is that how the employment modes, employment relationships and HR configurations evolve as the HC changes (due to the change in the environment) was underexplored. The current studies mainly focused on only one part of the dynamics of HR architecture, that is, the enhancement effect of HRM on HC. There is a lack of research about the dynamic changes across the four quadrants of HR architecture which were proposed by Lepak and Snell (Citation1999).

4.5. Effect of HRM on firm performance via HR flexibility

Consistent with Lepak et al. (Citation2003), some studies acknowledged that internal and external employment modes could bring about different forms of flexibility, such as coordination flexibility and resource flexibility (Lepak et al., Citation2003); functional flexibility and numerical flexibility (e.g. Ierodiakonou & Stavrou, Citation2015); and internal flexibility and external flexibility (e.g. Roca-Puig et al., Citation2015). Researchers applied these propositions to explain how internal and external employees contributed to firm performance (e.g. Hansen et al., Citation2019; Way et al., Citation2015). For example, Koch et al. (Citation2013) empirically found that the use of flexible employment schemes composed of both part-time and full-time employees significantly affected an establishment’s post-entry growth. Other researchers focused on how flexibility resulting from HRM could further build organizational ambidexterity (e.g. Ahammad et al., Citation2015; Patel et al., Citation2013). They argued that HR practices could be implemented to develop resource flexibility so that employees had the discretion and motivation to engage in activities associated with both exploitation and exploration. However, it was cautioned that flexibility was not always beneficial for firms. Koch et al. (Citation2013) posited that flexibility might lead to discontinuity and instability in the firm’s development and a higher risk of staff turnover.

Arguing that the flexibility resulting from adopting certain employment modes is more beneficial under some circumstances than others, Lepak et al. (Citation2003) revealed that knowledge-based or contract employment modes could lead to a better firm performance when facing higher environmental dynamism or technology intensity. In contrast, job-based employment or alliances benefited firm performance more when facing lower environmental dynamism or technology intensity. Consistent with this view, Kintana et al. (Citation2006) also found that the positive relationship between HPWS and operational performance was stronger in more technologically intense industries.

In sum, these studies shed light on the mechanisms of how different employment modes or HR configurations affect organizational performance and what the possible boundary conditions in the external environment are. However, research on the latter is scant, leaving research on the HR architecture model primarily inward-looking.

5. Conclusions and discussions

Taking stock of the knowledge presented, this article has offered a comprehensive review of studies on the HR architecture model originally developed by Lepak and Snell (Citation1999, Citation2002) and Lepak et al. (Citation2003). Analysis of the literature citing the three classic articles shows that the model has been widely cited by subsequent research in the last twenty years and most of the main ideas of the model have been theoretically developed, empirically verified, and/or critiqued and extended. While the original model is influential, research gaps have also been revealed through this review. Hence, further studies building on it would continue to be fruitful (Takeuchi et al., Citation2018). Below we outline several critical directions for future research.

First, clarifying the nature of the HR architecture model. Our review has identified two forms of interpretations of the HR architecture model. One is descriptive, in that it views the HR architecture model as one that describes, explains, or predicts what organizations ‘actually do’ (Lepak & Snell, Citation2002, p. 538). The other is normative, as it emphasizes the performance implications of the congruence between HC and HRM, therefore stressing what organizations ‘should do’ (Lepak & Snell, Citation2002, p. 538). While the theoretical applications of the model so far mainly take the normative approach, the empirical validations almost entirely follow the descriptive logic. To better apply, examine and extend the HR architecture model, it is of primary importance to clarify whether this model is descriptive, normative, or both. The answer to this question shall serve as a foundation for further work on the HR architecture model. We also suggest scholars offer explicit statements about their position on this issue.

Second, empirically testing the effects of the fit between HC and HRM on organizational performance. The current literature has included empirical examinations of the impact of HC on HRM, yet no empirical study has validated whether the fit between HC and HRM positively affects organizational performance. In their 2002 study, Lepak and Snell called for empirical investigations on the performance implications of fit (versus misfit) between HC and HRM (p. 538). Despite their appeal, the response is surprisingly scant (Boon et al., Citation2018). Considering that the majority of theoretical applications have adopted the idea of a fit effect, it is highly desirable to have this verified with empirical data.

To conduct empirical examinations on the fit effect, we encourage researchers to pay particular attention to the operationalization and measurement of the fit between HC and HRM. The idea of “fit” has been applied in various research fields including SHRM (Wright & Ulrich, Citation2017) and it has been operationalized in various ways (Delery & Doty, Citation1996; Donaldson, Citation2001; Venkatraman, Citation1989). Different ways of operationalizing fit are associated with different theoretical underpinnings and analytical methods. In that sense, even with the same sample and same dataset, results on the fit effect could be different if the fit is modeled differently. It is therefore necessary for researchers to have a better understanding of the form of fit operating between HC and HRM in the HR architecture model.

Third, further exploring the complexity of HR architecture. Theoretically, the HR architecture model is constituted by four quadrants. An alignment between employment modes, employment relationships, and HR configurations should be attained within each quadrant and across quadrants. The existing literature has only focused on some parts of the HR architecture, such as the interaction between multiple HRM subsystems or what happens within an individual quadrant. Very limited effort has been invested into examining the full HR architecture model. Hence, one key understudied theoretical issue in relation to the complexity of the HR architecture model is the relationships among the four quadrants. Organizations follow a differentiation-integration principle, in that an organization as a system that is differentiated into multiple parts needs to be integrated into a whole (Lawrence & Lorsch, Citation1967). How to align the various quadrants of HR architecture is a significant research question that remains unanswered (Banks & Kepes, Citation2015). To further develop the HR architecture model, it is of primary importance to advance our understanding of the relationships among the four quadrants. That is, are they complementary, substitutive, or independent from each other in their effects on organizational performance? How do organizations leverage the synergy among them? What are the possible integrating mechanisms?

To explore such aspects of the model’s complexity, new analytical techniques such as qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) (Ragin, Citation2000, Citation2006, Citation2008) and big data may be particularly useful. QCA is powerful in exploring effective systems that are composed of multiple, interconnected organizational elements. In the HRM field it has showed its capability in detecting high performance work systems (e.g. Meuer, Citation2017) and organizational career management configurations (De Vos & Cambre, Citation2017). Examining the complexity of HR architecture is essentially identifying the effective architecture involving multiple interdependent elements (i.e. HCs, employment modes, employment relationships, and HR configurations), the four quadrants, and organizational performance, each of which could be at various levels. Hence, QCA is applicable to the empirical identification of high-performing HR architecture by exploring its complexity. In addition, the lack of examinations of the entire model may be due to difficulties in data collection, since such an investigation would require a large-scale sample and rich information, both between and within organizations. In future, scholars could make attempts to apply big data techniques (Jiang & Messersmith, Citation2018; Tonidandel et al., Citation2018) to overcome this barrier to data collection and to facilitate exploring the complex relationships among elements of the HR architecture.

Fourth, deepening understandings of the dynamics and evolution of HR architecture. As described before, Lepak and Snell (Citation1999) emphasized the dynamics of HR architecture. They argued that since the value and uniqueness of the HC may change due to environmental and competitive forces, organizations may choose to reinvest in their HC to sustain their value and uniqueness or shift the HR configurations accordingly. Existing studies have provided some evidence for the influence of HR practices on HC. However, the cross-sectional nature of these empirical studies hinders the inference of the causal effect. Hence, there is an absence of empirical studies on how the HR configurations transform and how the HR architecture evolves as the HC of each employee group changes over time. We therefore do not have a big picture on how firms’ HR architecture evolves over time. It would also be theoretically interesting to explore what influences the evolution of firms’ HR architecture. For example, does organizational path dependence (Sydow et al., Citation2009) play a role in the process? Longitudinal case studies are highly desirable for such research questions.

Fifth, examining the dark side of HR differentiation. So far, many scholars have investigated the implications of HR differentiation for employees, mainly showing positive impacts. However, few studies have identified its possible downsides. The utilization of distinct HR configurations for different groups of employees in the same organization may lead to a sense of injustice among workers (Banks & Kepes, Citation2015; Lepak & Shaw, Citation2008) and hinder social interactions (Buller & McEvoy, Citation2012). Since any perceptions of injustice might generate negative consequences, including ethical problems (Buckley et al., Citation2001), it is conceivable that using diverse HR systems may bring about moral problems. Future research should pay more attention to the potential challenges facing the adoption of HR architecture, which may be the primary step for its effective management.

Sixth, extending the HR architecture model to new contexts and testing the boundary of the model. One important critique of the current research is that the HR architecture model overestimates the impact of HC on HRM and underestimates the role of the external environment (e.g. Rubery et al., Citation2003). Echoing this concern, a number of studies have extended the original model by exploring new research contexts (e.g. Hansen et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2015; Morris et al., Citation2016). We believe this is a promising research direction and would suggest future research attending to the environmental, cultural, and institutional factors that bear on firms’ HR management, which may entail rethinking or challenging some of the implicit assumptions in the original model.

To give an example, as was commented in some of the reviewed articles (Brandl et al., Citation2019; Rubery et al., Citation2003), the original model seems to rest on the assumption that organizations are rational and have complete control over their HR matters (the latter is more valid in deregulated economies). It overlooks the role of institutions which might not only impose external constraints on what organizations can do, but also “co-construct” their nature (Allen et al., Citation2017; Edwards & Kuruvilla, Citation2005; Whitley, Citation2010). This omission is unfortunate, particularly for organizations operating in multiple countries and economic systems, who need not only to consider the institutional variability of their environment, but also the location specificity of some of their HC (Morris et al., Citation2016). Another example is emerging platform organizations like Uber. As the boundaries of such organizations are blurred, this raises controversial questions like whether their workers should be regarded as employees or individual contractors (Rogers, Citation2016). New phenomena like this challenge the fundamental assumptions in the original model that a distinct organizational boundary can be drawn, and that the employment modes can be clearly defined. Taking these complexities into consideration will greatly extend the HR architecture model.

Seventh, looking into the multilevel nature of the HR architecture. Although the original model is primarily theorized at the organizational level, its elements are underpinned by micro-foundations or involve micro-processes. Hence, a full understanding of the HR architecture warrants a multilevel analysis. Recent research on the emergence of HC resources (Ployhart et al., Citation2014; Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011) has offered valuable multilevel explanations of how unit-level HC resources arise from individual knowledge, skills, abilities and other characteristics and what enables their emergence. These insights will greatly inform the dynamics of the HR architecture, that is, how can employ HR practices to enable the emergence of higher-level HC resources. Another potentially informative stream of research is the comparison between intended and realized HR practices (e.g. Wright & Nishii, Citation2013) and the linking role of line managers between them (Khilji & Wang, Citation2006). This would allow us to investigate the micro-processes involved in the management of HC and reveal the full realities and complexities involving the HR architecture.

Acknowledgement

The second and third authors made equal contributions. The authors would like to thank Professor Riki Takeuchi and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahammad, M. F., Lee, S. M., Malul, M., & Shoham, A. (2015). Behavioral ambidexterity: The impact of incentive schemes on productivity, motivation, and performance of employees in commercial banks. Human Resource Management, 54(S1), S45–S62. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21668

- Allen, M. M. C., Liu, J., Allen, M. L., & Imran Saqib, S. (2017). Establishments’ use of temporary agency workers: The influence of institutions and establishments’ employment strategies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(18), 2570–2593. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1172655

- Anagnostopoulos, A. D., & Siebert, W. S. (2015). The impact of Greek labour market regulation on temporary employment - evidence from a survey in Thessaly. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(18), 2366–2393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1011190

- Anderson, M. H. (2006). How can we know what we think until we see what we said?: A citation and citation context analysis of Karl Weick's the social psychology of organizing. Organization Studies, 27(11), 1675–1692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840606068346

- Anderson, M. H., & Lemken, R. K. (2019). An empirical assessment of the influence of March and Simon's Organizations: The realized contribution and unfulfilled promise of a masterpiece. Journal of Management Studies, 56(8), 1537–1569. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12527

- Banerjee, M., Tolbert, P. S., & DiCiccio, T. (2012). Friend or foe? The effects of contingent employees on standard employees' work attitudes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(11), 2180–2204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.637061

- Banks, G. C., & Kepes, S. (2015). The influence of internal HRM activity fit on the dynamics within the "black box. Human Resource Management Review, 25(4), 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.02.002

- Baruch, Y., & Rousseau, D. M. (2019). Integrating psychological contracts and ecosystems in career studies and management. Academy of Management Annals, 13(1), 84–111. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0103

- Bayo-Moriones, A., Galdon-Sanchez, J. E., & Martinez-de-Morentin, S. (2013). The diffusion of pay for erformance across occupations. ILR Review, 66(5), 1115–1148. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391306600505

- Beatty, R. W., Huselid, M. A., & Schneier, C. E. (2003). New HR metrics: Scoring on the business scorecard. Organizational Dynamics, 32(2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-2616(03)00013-5

- Benzinger, D. (2016). Organizational socialization tactics and newcomer information seeking in the contingent workforce. Personnel Review, 45(4), 743–763. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-06-2014-0131

- Boon, C., & Kalshoven, K. (2014). How high-commitment HRM relates to rngagement and commitment: The moderating role of task proficiency. Human Resource Management, 53(3), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21569

- Boon, C., Eckardt, R., Lepak, D. P., & Boselie, P. (2018). Integrating strategic human capital and strategic human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(1), 34–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1380063

- Brandl, J., Kozica, A., Pernkopf, K., & Schneider, A. (2019). Flexible work practices: Analysis from a pragmatist perspective. Historical Social Research-Historische Sozialforschung, 44(1), 73–91.

- Broschak, J. P., & Davis-Blake, A. (2006). Mixing standard work and nonstandard deals: The consequences of heterogeneity in employment arrangements. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 371–393. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20786085

- Bryant, P. C., & Allen, D. G. (2009). Emerging organizations' characteristics as predictors of human capital employment mode: A theoretical perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.12.002

- Buckley, M. R., Beu, D. S., Frink, D. D., Howard, J. L., Berkson, H., Mobbs, T. A., & Ferris, G. R. (2001). Ethical issues in human resources systems. Human Resource Management Review, 11(1-2), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(00)00038-3

- Buller, P. F., & McEvoy, G. M. (2012). Strategy, human resource management and performance: Sharpening line of sight. Human Resource Management Review, 22(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.11.002

- Cabello-Medina, C., López‐Cabrales, A., & Valle-Cabrera, R. (2011). Leveraging the innovative performance of human capital through HRM and social capital in Spanish firms. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(4), 807–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.555125

- Cappelli, P., & Keller, J. R. (2014). Talent management: Conceptual approaches and practical challenges. Social Science Electronic Publishing, 1(1), 305–331.

- Chadwick, C. (2017). Toward a more comprehensive model of firms' human capital rents. Academy of Management Review, 42(3), 499–519. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0385

- Chadwick, C., & Dabu, A. (2009). Human resources, human resource management, and the competitive advantage of firms: Toward a more comprehensive model of causal linkages. Organization Science, 20(1), 253–272. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0375

- Chang, P. C., & Chen, S. J. (2011). Crossing the level of employee's performance: HPWS, affective commitment, human capital, and employee job performance in professional service organizations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(4), 883–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.555130

- Chang, Y.-Y. (2015). A multilevel examination of high-performance work systems and unit-level organisational ambidexterity. Human Resource Management Journal, 25(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12061

- Chen, S.-L. (2018). Cross-level effects of high-commitment work systems on work engagement: The mediating role of psychological capital. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 56(3), 384–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12144

- Cheng, J. L. C., Guo, W., & Skousen, B. (2011). Advancing new theory development in the field of international management contributing factors, investigative approach, and proposed topics. Management International Review, 51(6), 787–802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-011-0105-0

- Chi, N. W., Wu, C. Y., & Lin, C. Y. Y. (2008). Does training facilitate SME’s performance?. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(10), 1962–1975. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802324346

- Cho, H-j., & Ahn, J.-Y. (2018). The dark side of wars for talent and layoffs: Evidence from Korean firms. Sustainability, 10(5), 1365–1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051365

- Chuang, C. H., Jackson, S. E., & Jiang, Y. (2016). Can knowledge-intensive teamwork be managed? Examining the roles of HRM systems, leadership, and tacit knowledge. Journal of Management, 42(2), 524–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313478189

- Clinton, M., & Guest, D. E. (2013). Testing universalistic and contingency HRM assumptions across job levels. Personnel Review, 42(5), 529–551. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-07-2011-0109

- Collings, D. G., & Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.04.001

- Colquitt, J. A., & Zapata-Phelan, C. P. (2007). Trends in theory building and theory testing: A five-decade study of the Academy of. Academy of Management Journal, 50(6), 1281–1303. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.28165855

- De Vos, A., & Cambre, B. (2017). Career management in high-performing organizations: A set-theoretic approach. Human Resource Management, 56(3), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21786

- De Vos, A., & Dries, N. (2013). Applying a talent management lens to career management: The role of human capital composition and continuity. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(9), 1816–1831. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.777537

- Decramer, A., Smolders, C., & Vanderstraeten, A. (2013). Employee performance management culture and system features in higher education: Relationship with employee performance management satisfaction. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(2), 352–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.680602

- Delery, J. E., & Doty, D. H. (1996). Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 802–835. https://doi.org/10.5465/256713

- Delery, J. E., & Roumpi, D. (2017). Strategic human resource management, human capital and competitive advantage: Is the field going in circles?. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12137

- Diaz-Fernandez, M., Pasamar-Reyes, S., & Valle-Cabrera, R. (2017). Human capital and human resource management to achieve ambidextrous learning: A structural perspective. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 20(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2016.03.002

- Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organizations. Sage.

- Dries, N., Acker, F. V., & Verbruggen, M. (2012). How 'boundaryless' are the careers of high potentials, key experts and average performers? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(2), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.10.006

- Eckardt, R., Skaggs, B. C., & Lepak, D. P. (2018). An examination of the firm-level performance impact of cluster hiring in knowledge-intensive firms. Academy of Management Journal, 61(3), 919–944. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0601

- Edwards, T., & Kuruvilla, S. (2005). International HRM: National business systems, organizational politics and the international division of labour in MNCs. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958519042000295920

- Fernandez, V., Simo, P., & Sallan, J. M. (2016). Turnover and balance between exploration and exploitation processes for high-performance teams. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 22(3/4), 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-08-2015-0035

- Ferner, A., & Almond, P. (2013). Performance and reward practices in foreign multinationals in the UK. Human Resource Management Journal, 23(3), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12001

- Fister, T., & Seth, A. (2015). Why invest in firm-specific human capital? A real options view of employment contracts contracts. Advances in Strategic Management, 24, 373–402.

- Gardner, T. M. (2005). Interfirm competition for human resources: Evidence from the software industry. Academy of Management Journal, 48(2), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.16928398

- Gelens, J., Dries, N., Hofmans, J., & Pepermans, R. (2013). The role of perceived organizational justice in shaping the outcomes of talent management: A research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.005

- Gelens, J., Dries, N., Hofmans, J., & Pepermans, R. (2015). Affective commitment of employees designated as talent: Signalling perceived organisational support. European J. of International Management, 9(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2015.066669

- Giauque, D., Anderfuhren-Biget, S., & Varone, F. (2019). Stress and turnover intents in international organizations: Social support and work-life balance as resources. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(5), 879–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1254105

- González, S. M., & Tacorante, D. V. (2004). A new approach to the best practices debate: Are best practices applied to all employees in the same way?. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(1), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/098519032000157339

- Gowan, M. A., & Lepak, D. (2007). Current and future value of human capital: Predictors of reemployment compensation following a job loss. Journal of Employment Counseling, 44(3), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2007.tb00032.x

- Grimshaw, D., & Miozzo, M. (2009). New human resource management practices in knowledge-intensive business services firms: The case of outsourcing with staff transfer. Human Relations, 62(10), 1521–1550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709336498

- Grimshaw, D., & Rubery, J. (2005). Inter-capital relations and the network organisation: Redefining the work and employment nexus. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 29(6), 1027–1051. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bei088

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press.

- Hansen, N. K., Güttel, W. H., & Swart, J. (2019). HRM in dynamic environments: Exploitative, exploratory, and ambidextrous HR architectures. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(4), 648–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1270985

- Hong, J. F. L., Zhao, X., & Snell, R. S. (2019). Collaborative-based HRM practices and open innovation: A conceptual review. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(1), 31–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1511616

- Hong, Y., & Honig, B. (2016). Publish and politics: An examination of business school faculty salaries in Ontario. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 15(4), 665–685. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0273

- Ierodiakonou, C., & Stavrou, E. (2015). Part time work, productivity and institutional policies. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 2(2), 176–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-07-2014-0030

- Jayasinghe, M. (2016). The operational and signaling benefits of voluntary labor code adoption: Reconceptualizing the scope of human resource management in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 59(2), 658–677. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0478

- Jennings, J. E., Dempsey, D., & James, A. E. (2018). Bifurcated HR practices in family firms: Insights from the normative-adaptive approach to stepfamilies. Human Resource Management Review, 28(1), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.05.007

- Jiang, K., & Messersmith, J. (2018). On the shoulders of giants: A meta-review of strategic human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(1), 6–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1384930

- Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Han, K., Hong, Y., Kim, A., & Winkler, A. L. (2012). Clarifying the construct of human resource systems: Relating human resource management to employee performance. Human Resource Management Review, 22(2), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.11.005

- Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Hu, J., & Baer, J. C. (2012). How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1264–1294. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0088

- Judge, T. A., Cable, D. M., Colbert, A. E., & Rynes, S. L. (2007). What causes a management article to be cited - Article, author, or journal?. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.25525577

- Kacmar, K. M., & Whitfield, J. M. (2000). An additional rating method for journal articles in the field of management. Organizational Research Methods, 3(4), 392–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810034005

- Kalaignanam, K., & Varadarajan, R. (2012). Offshore outsourcing of customer relationship management: Conceptual model and propositions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(2), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0291-0

- Kang, S.-C., & Snell, S. A. (2009). Intellectual capital architectures and ambidextrous learning: A framework for human resource management. Journal of Management Studies, 46(1), 65–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00776.x

- Kang, S.-C., Morris, S. S., & Snell, S. A. (2007). Relational archetypes, organizational learning, and value creation: Extending the human resource architecture. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.23464060

- Kase, R., & Zupan, N. (2009). Human capital and structural position in knowledge networks as determinants when classifying employee groups for strategic human resource management purposes. European J. of International Management, 3(4), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2009.028851

- Khilji, S. E., & Wang, X. (2006). Intended’ and ‘implemented’ HRM: The missing linchpin in strategic human resource management research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(7), 1171–1189. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190600756384

- Kim, H., & Sung-Choon, K. (2013). Strategic HR functions and firm performance: The moderating effects of high-involvement work practices. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-011-9264-6

- Kintana, M. L., Alonso, A. U., & Olaverri, C. G. (2006). High-performance work systems and firms' operational performance: The moderating role of technology. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500366466

- Kirkpatrick, I., Hoque, K., & Lonsdale, C. (2019). Client organizations and the management of professional agency work: The case of English health and social care. Human Resource Management, 58(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21933

- Klaas, B. S. (2008). Outsourcing and the HR function: An examination of trends and developments within North American firms. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(8), 1500–1514. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802200280

- Koch, A., Späth, J., & Strotmann, H. (2013). The role of employees for post-entry firm growth. Small Business Economics, 41(3), 733–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9456-6

- Koulikoff, M., & Harrison, A. (2010). Eveolving HR practices in strategic intra-firm supply chain. Human Resource Management, 49(5), 913–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20388

- Krausert, A. (2017). HR differentiation between professional and managerial employees: Broadening and integrating theoretical perspectives. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 442–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.11.002

- Kulkarni, S. P., & Ramamoorthy, N. (2005). Commitment, flexibility and the choice of employment contracts. Human Relations, 58(6), 741–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726705057170

- Lam, A. (2007). Knowledge networks and careers: Academic scientists in industry-university links. Journal of Management Studies, 44(6), 993–1016. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00696.x

- Lawrence, P. R., & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Differentiation and integration in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391211

- Lengnick-Hall, M. L., Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Andrade, L. S., & Drake, B. (2009). Strategic human resource management: The evolution of the field. Human Resource Management Review, 19(2), 64–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.01.002

- Lepak, D. P., & Shaw, J. D. (2008). Strategic HRM in North America: Looking to the future. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(8), 1486–1499. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802200272

- Lepak, D. P., & Snell, S. A. (1999). The human resource architecture: Toward a theory of human capital allocation and development. The Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/259035

- Lepak, D. P., & Snell, S. A. (2002). Examining the human resource architecture: The relationships among human capital, employment, and human resource configurations. Journal of Management, 28(4), 517–543. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800403

- Lepak, D. P., Marrone, J. A., & Takeuchi, R. (2004). The relativity of HR systems: Conceptualising the impact of desired employee contributions and HR philosophy. International Journal of Technology Management, 27(6/7), 639–655. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2004.004907

- Lepak, D. P., Takeuchi, R., & Snell, S. A. (2003). Employment flexibility and firm performance: Examining the interaction effects of employment mode, environmental dynamism, and technological intensity. Journal of Management, 29(5), 681–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063_03_00031-X

- Lepak, D. P., Taylor, M. S., Tekleab, A., Marrone, J. A., & Cohen, D. J. (2007). An examination of the use of high-investment human resource systems for core and support employees. Human Resource Management, 46(2), 223–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20158