Abstract

The organizational value of international assignments (IAs), is unclear and rarely measured by organizations. We argue that taking a relational perspective may enable a greater understanding of the value of IAs to organizations. A relational perspective involves focusing upon the relationship between the home and host organizations participating in an IA. Our literature review combines separate strands of research from the fields of Human Resource Management, International Business and Global Mobility to investigate whether such a relational underpinning exists. Based on this we develop a relational framework enabling the clarification of extant knowledge and illuminating the contradictions, uncertainties and areas for further research. As a result, we offer exploratory propositions and a future research agenda to improve our knowledge and understanding of this fundamental topic. Through reframing extant knowledge of IA organizational value we enable HR departments to refine their global mobility strategies and guide their choices amongst assignment options.

1. Introduction

The number of expatriates on international assignments (IAs) continues to grow (Santa Fe Relocation Services, Citation2019) despite significant cost premiums to local hires (Doherty & Dickmann, Citation2012). Surprisingly, the value to organizations is rarely measured and generally unknown to practitioners (McNulty et al., Citation2013). Reports indicate that identifying this value is important to practitioners (RES Forum, Citation2017). However, whilst there is considerable literature investigating the value of IAs to the individual assignee (Takeuchi et al., Citation2009), and an emphasis on the importance of global performance management and staffing practices (Engle et al., Citation2015), extant literature does not give a clear explanation of the value of IAs at the organizational level.

The nature and variation in IAs have developed significantly in recent decades from the traditional HQ-subsidiary expatriation which was central to Edström and Galbraith's (Citation1977) seminal paper investigating why organizations used IAs. Their paper considered IAs as involving long term engagements taking family members whereas today there is a wide range of possibilities including inpatriates, self-initiated expatriates (SIEs) and various short-term alternatives. However, germane to all organizationally driven IA options is a movement of personnel from a home organization to a host organization, usually within a single multi-national corporation (MNC). The complexity of the relationships between these parties has been noted (Gaur et al., Citation2019; Taylor et al., Citation1996) including the difficulty in identifying who captures the benefits (Welch et al., Citation2009). As such, taking a relational perspective may be critical to understanding IA organizational value. We define a relational perspective as a focus upon the relationship between the home and host organizations participating in an IA and a consideration of the factors that define and affect this relationship.

Organizational value is a challenging construct to define as many articles use the term ‘value’ in the context of organizations without a definition (see, for example Vandermerwe, Citation1997; H. Zhu et al., Citation2015). Whilst there is also a potential interaction with the concept of ‘values’, our focus is at the organizational level of analysis and ‘values’ are generally considered an individual level construct (Kraatz et al., Citation2020). Hence we turn to the Expatriate literature and define IA organizational value as ‘a calculation regarding an ongoing or completed IA in which the actual and still anticipated direct and indirect financial and non-financial benefits to a part or all of the organization are compared with the actual and still anticipated direct and indirect financial and non-financial costs to that part of the organization. All numbers are adjusted for the time-value-of-money’ (Renshaw et al., Citation2020, p. 23). This definition enables a broad literature review to investigate our relational construct including, for example, papers investigating subsidiary performance. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that defining organizational performance is itself complex (Richard et al., Citation2009).

The relational view has been applied in management literature, for example to investigate how a subsidiary gains attention from its parent (Bouquet & Birkinshaw, Citation2008), how effective marketing operations perform between these two organizations (Hewett & Bearden, Citation2001) and how alliance networks operate (Capaldo, Citation2007). Furthermore, internal competition and coopetition between such entities is a regular part of international business (Dyer et al., Citation2018; Luo, Citation2005) and there may be a power relationship between subsidiaries and their parents (Peng & Beamish, Citation2014). Similarly, the control and coordination role of expatriates on behalf of the HQ has been researched for several decades triggered by the seminal paper by Edström & Galbraith (Citation1977) as has the implications of agency problems between a parent and its subsidiaries (Kawai & Strange, Citation2014; Singh et al., 2019). This all indicates the potential for an underlying relational dynamic for IAs. The concept of relational rents (Dyer & Singh, Citation1998; Dyer et al., Citation2018) also plays a role in understanding organizational value. These are inter-relational advantages that are exploited to generate supernormal profits. This offers parallels to the creation of intra-relational advantages through IAs. Dyer and Singh's (Citation1998) definition of relational rents relies on the combination of resources and capabilities between independent firms in a way that results from their relationship and could not be achieved in isolation. IAs normally require two intra-organizational entities (home and host) and hence IAs and the value they generate cannot be achieved in isolation and may also be dependent upon the relationship between these entities. Consequently, IAs may have the potential to generate value as a form of intra-organizational relational rents. However, this dyadic relationship sits within a complex extended relational structure including other sister-subsidiaries or sub-subsidiaries (Singh et al., Citation2019) in addition to the external world of clients, suppliers and other stakeholders (Gaur et al., Citation2019).

A relational perspective may enable a clearer interpretation of the complex factors which affect value creation as distinct to value capture (Lepak et al., Citation2007). Value may be created by one party and yet captured by another (Bowman & Ambrosini, Citation2000; Pitelis, Citation2009). In an IA context, the findings that assignee attrition is high (Lazarova & Tarique, Citation2005) demonstrate how the assignee may capture value in addition to the organization (through finding greater pay or opportunities elsewhere). In contrast, the employee retention capabilities of an organization may inhibit this (Newton et al., Citation2007). Combined with the implications of intra-organizational relational rents in IAs, this indicates that the home-host relationships plus the relational structure within which they sit (individuals, teams and external parties), need to be understood to evaluate the potential consequences for IA value creation and capture. Consider, for example, how the organizational relationships may differ between a global management consultancy in which a high percentage of staff regularly relocate to work in different countries with other colleagues on short and long term projects, compared to that of a car manufacturer where the majority of the workforce remain in their original country and company of origin. The potential organizational value of further IAs may be entirely different.

The IA literature includes papers which might be considered to have taken a relational approach. For example, McNulty et al. (Citation2009) took an HR Systems approach and McNulty and De Cieri (Citation2011) took a systems theory approach to identify and question the return on investment (ROI) of IAs. However, they treat the organization in their frameworks as a single entity. Hence there is no direct acknowledgement of the range of fundamental relational aspects between the host and home which affect the value derived by the organization as a whole, nor how the home and host may have different relationships with the external environment. Similarly IB literature considers inter-subsidiary trade and how IAs impact on subsidiary performance (Gaur et al., Citation2019; Singh et al., Citation2019), and yet this tends to exclude the impact on the home organizations sending the assignees.

On this basis we contend that taking a relational view of extant literature regarding the organizational value of IAs may provide a useful step in understanding what is already known about this important topic and advancing future research to support the needs of practitioners and academics. Hence, we identified the following research questions: is there a relational underpinning to the organizational value of IAs and if so can we develop a relational framework to improve our understanding of expatriation and its value implications? To answer this we undertook a literature review designed to identify the relevant bodies of knowledge.

We define IAs following McNulty and Brewster's (Citation2017, p. 20) definition of ‘business expatriates’ such that IAs involve ‘legally working individuals who reside temporarily in a country of which they are not a citizen in order to accomplish a career-related goal, being relocated abroad…by an organization’. Whilst, as described below, we found no literature considering the organizational value of non-traditional IAs such as frequent flyers or commuters, all types of assignment are caught in this definition with the exception of SIEs (as they are not relocated by an organization, rather they relocate themselves). We excluded SIEs because there is no underlying home-host relationship and the initial costs are fundamentally different. Nonetheless, in this investigation of the relational nature of IAs the research includes latent or delayed impacts post IA including repatriation or the assignee moving to another employer.

We make three main contributions. First, we identify and demonstrate how relational aspects underpin the organizational value of IAs thereby improving conceptual clarity. Ignoring these aspects, we argue, will reduce the impact of future research. Second, we provide an integrative relational framework drawn from existing literature to explicate extant knowledge and position future research. This demonstrates the central role of the home-host intra-organizational relational dynamics sitting within a broader relational context. Using this relational perspective we identify the strengths and weaknesses of extant knowledge including notable gaps. For example, IA value can accrue to different parts of the same organization and at different times depending upon their relationships. Third, using the relational framework, we provide exploratory research propositions and a research agenda to move our understanding of this vital topic forward.

This paper next explains our literature review method and summarizes the papers identified. Then we describe the process of analysis and the relational themes that emerged. Thereafter we explicate IA organizational value using each of these five themes and then illustrate the resultant intra-organizational relational framework. This enables both an initial set of exploratory research propositions and a future research agenda. Finally, the implications for practitioners are reviewed before presenting a summary of research limitations and conclusions.

2. Method

2.1. Literature review process

Searching online databases using keyword search strings is a common first step in many literature reviews. However, it is also accepted that database searches only produce a small percentage of the required material (Greenhalgh & Peacock, Citation2005): indeed this was not straightforward in this case as our research aim is to demonstrate if a relational view underpins the relevant literature. As such we are searching for a construct (relationality) which is implicit rather than explicit in the literature. Accordingly, whilst recognizing that no system is infallible, we designed an alternative search process in line with the broader principles of evidence-based management (Briner et al., Citation2009) in order to provide a justifiable, transparent and replicable approach. We adopted the principle of triangulation using four different steps through which we could be confident that all relevant literature should be identified (acknowledging that no approach is beyond the risk of excluding papers). The steps were as follows:

1. A citation review for Edström and Galbraith (Citation1977) using the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) database of the ISI-Web of Knowledge was carried out. We anticipated that research considering the organizational value of IAs would cite this paper because it is widely recognized as the seminal paper on why organizations use IAs (Benito et al., Citation2005; Caligiuri & Bonache, Citation2016). All titles and abstracts of articles citing this paper in SCCI were analyzed.

2. A citation review for McNulty and Tharenou (Citation2004) was undertaken. This paper was chosen given its claim that it was the first to discuss expatriate ROI. We anticipated that this ROI would be referred to where organizational value is considered in IA literature. As this paper did not appear in either ISI-Web of Knowledge or Scopus databases, the journal publisher’s website (Taylor and Francis Online) and Google Scholar were used.

3. An expert group of senior academics was asked to provide lists of the most influential articles giving insights into IA organizational value in their opinions. The scholars were chosen through purposeful sampling as a cross-section of authors from those listed in the articles found in steps 1 and 2 above. These authors were widely spread around the world, thereby seeking to overcome the network citation effect (Jo et al., Citation2009). A total of 16 scholars were contacted of whom 11 provided responses.

4. In order to ensure that our search was as comprehensive as possible, snowballing (Nijs et al., Citation2014) was applied to the above articles. The reference sections of all articles included at any point were checked and the abstracts of all potential articles analyzed, until we reached a point that no new articles were identified.

An Inclusion-Exclusion protocol was defined to guide this search (Tranfield et al., Citation2003) and is detailed in . This included only literature that explicitly discussed IA organizational value, whether conceptual or empirical, and full length articles published in peer-reviewed academic journals to ensure the knowledge had been certified by appropriate scholars (Podsakoff et al., Citation2005). Monographs or chapters in edited volumes were excluded because these generally describe the field with a low likelihood of including original research. Using the earlier noted definition of IA organizational value we included papers considering only the cost or only the benefits to give us greater insight.

Table 1. Literature review inclusion/exclusion protocol.

Research on individual level value, for example ‘expatriate success’ was excluded. This predominantly considers individual task level performance and focuses on individual adjustment or acculturation (see, for example Harrison & Shaffer, Citation2005; Takeuchi et al., Citation2009). Similarly, papers which considered the correlations between IA numbers and different traits of countries, subsidiaries or parent companies were excluded from this analysis (see, for example, Peng & Beamish, Citation2014) unless they conceptualized the relationships using theories directly linked to value constructs and their implications. Other exclusions included papers on the reasons or drivers behind the use of IAs (Harzing, Citation2001) unless the research was linked to organizational value. This is because there is no certainty that the value achieved is consistent with the reasons that triggered their use, especially given the possibility that their instigation may happen in ad hoc discussions rather than through business case evaluation (Harris & Brewster, Citation1999).

A summary of the outcomes of the article identification and inclusion-exclusion process is shown in . Upon full reading, 72 of the 136 articles identified for detailed analysis were rejected due to lack of relevance. At this stage subjective quality criteria were considered by reference to Daft (Citation1995), e.g. insufficient theory or amateurish style and Pittaway et al. (Citation2004), e.g. contribution to knowledge and methodological rigor. After discussing these quality criteria amongst the research team, a total of 64 articles were retained for full analysis (see Appendix).

Table 2. Summary of article identification and inclusion-exclusion process.

Each paper was reviewed and notes were made using a template designed following the guidance of Tranfield et al. (Citation2003) and Pilbeam et al. (Citation2012). This template captured critical data likely to support the identification of themes including, for example, the empirical nature of the research, the phenomena of interest, definitional factors and the key findings. Collating these templates enabled the research synthesis process with specific reference to our research question and the identification of any relational aspects, tacit or otherwise. The first author analyzed and summarized the data in various forms to represent the underlying factors involved. These included, for example, any theoretical lenses or theories used, the source participants where empirical work was involved and the definition of the IAs studied (if provided). This process first validated the importance of the core underlying concept of the relational construct and the many different implications this has for IA organizational value. These factors were coded into primary and secondary level schemas to generate underlying relational themes. The identification and coding of these themes continued on an iterative basis until a comprehensive and distinct categorization was achieved. Five primary themes were established, four of which were considered to be internal to the home and host relationship and one external. The framework is illustrated in Section 3.7 below after the review of each theme in detail.

2.2. Overview of articles

All papers focused on MNCs and were published after 1988 in 29 different journals. Almost 75% are in journals rated 3 or above in the Chartered ABS list indicating that this is an important area of research (see ).

Table 3. Summary of journals and thematic allocations.

Detailed analysis suggested three distinct categories of literature each with a different focus. We named these in line with that focus: Subsidiary Performance (39 papers), ROI (15) and CEO/TMT Impact (on firm performance) (6). Four papers did not fit into any single category. The three main bodies of literature are summarized as follows:

2.2.1. Subsidiary performance

These articles investigate the performance of subsidiaries including or focused upon the impact of IAs. They are predominantly quantitative studies evaluating wholly owned subsidiaries (Colakoglu & Caligiuri, Citation2008), international joint ventures (IJVs) (Lyles & Salk, Citation1996) and a combination of the two (Konopaske et al., Citation2002).

2.2.2. CEO/TMT impact

These mostly quantitative-methods papers consider the impact the IA experience of the group’s CEO/TMT has on overall firm performance. These articles fit within a wider field of literature scrutinizing the connections between CEO/TMT attributes and organizational performance (see, for example Carpenter & Sanders, Citation2004).

2.2.3. ROI

This literature focuses on how the value of IAs could be measured and the elements that contribute to this both at the individual and organizational levels of analysis. This literature includes a notable percentage of conceptual papers (33%).

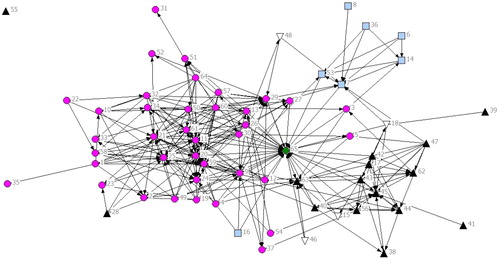

To verify the categorization of the papers into the three groups and the seminal influence of Edström and Galbraith (Citation1977), we applied network analysis using UCINET software in order to review which of the papers cited the others. All cross referencing within the 64 papers and the original seminal article by Edström and Galbraith (Citation1977) is visually represented in . Proximity between articles indicates a connection, as gauged by the extent to which they reference each other, while each line shows that a paper has cited another paper within the group, with the direction of the arrow going from the citing paper to the cited paper. Each paper is coded by color and shape to show which group of literature we estimated it belonged to. indicates how three bodies of literature cluster separately with very few citations between the groups and hence supports our initial categorization of the literature. The papers that were not fitted into one of these three bodies mostly sit with the ROI cluster, which is perhaps not surprising as some of the authors overlap although they do not focus on ROI. Only two papers (numbers 16 and 28) align with a different group of articles and one sits alone, uncited by any other nor citing any other (number 55). 58% of the papers only cite three or fewer of the other 64 papers identified in this review. The three bodies of literature are mostly written by different groups of scholars who rarely appear to contribute directly or indirectly to each other’s research. For example, one of the ROI papers states that the authors were unable to identify any other work researching the same construct and, consistent with this, do not cite any Subsidiary Performance literature.

Figure 1. Network analysis of review literature. Green Diamond (in the center) = Edström and Galbraith (Citation1977). Black up-triangles = ROI literature. Pink circles = Subsidiary Performance literature. Blue squares = CEO/TMT literature. White down-triangles = Other literature. Numbers correlate with the list of articles in Appendix.

A high number of the Subsidiary Performance papers (72%) involve research on Asian MNCs (see ). Notably several of these relied on language techniques to interrogate surnames of subsidiary workers and hence define them as expatriates of the parent company (see, for example, Gaur et al., Citation2007) whilst others assumed that foreign nationals represented expatriates. This may not correctly identify them as IAs if, for example, they are locals with Japanese surnames or have dual nationality. Furthermore, many of these papers identify the potentially unusual culture of Japanese, Chinese and other Asian nationalities and their approaches to HR practices and business groups such as Keiretsu and Chaebol (Gaur et al., Citation2019) questioning the generalizability of their work. Finally, the ROI cluster is dominated by McNulty who was involved in seven of the 15 papers, several of which appear to draw on the same underlying dataset. Bringing these streams of research together is an important contribution of this paper as, to our knowledge, no other frameworks for IA value draw on this full set of literature. We now turn to explicate each of the five major themes identified in our review.

Table 4. Research locus of papers in literature review.

3. The organizational value of IAs – a relational framework

3.1. Organizational structure and characteristics

The first relational theme, which is internal to the organizations, is the relational structure of the organizations. This addresses the basis of the legal and contractual nature of the relationship between the organizational parties affected by the IA. A series of factors which represent the structure of the organizational relationship between the home and the host have been considered within IA organizational value research. At its most fundamental level, the ownership has been analyzed, e.g. whether hosts are wholly owned subsidiaries (WOS) or IJVs. For example, in a study of Japanese manufacturing companies and their overseas subsidiaries, Konopaske et al. (Citation2002) reported that increased IAs from the home HQ was negatively related to subsidiary performance for IJVs (shifting from negative to positive as the equity percentage increases) whereas for WOS ethnocentric staffing is positively related to subsidiary performance. In most cases, however, studies defined their research sample by reference to ownership status and did not investigate the consequence of this structural issue despite the potential for significantly different relational dynamics between the home and the host. Alternatively the analysis simplified the situation by comparing all WOS to all IJVs.

Further structural characteristics that have been suggested in the literature are the age of the host and its size, both of which have relational implications for the other parties. Whilst these are not contractual or legal factors per se, we suggest they would affect the nature of those relationships whereby, for example, a large and influential host has greater potential for decision-making autonomy (Oki, Citation2020). Findings as to the impact of the age of the host on the correlation between IA levels and subsidiary performance has produced conflicting evidence. For example Gong (Citation2003a) found that age is not beneficial whilst Gaur et al. (Citation2007) found that it is. Sekiguchi et al. (Citation2011) also investigated how the IA make-up of Japanese affiliates’ TMTs affected their performance by reference to the affiliates’ age and size. They found that whilst the age of the affiliate on its own did not moderate the performance relationship with IAs in the TMT, larger and younger affiliates with more TMT IAs correlated with improved performance. Furthermore, younger affiliates performed better with IA Managing Directors (MDs) rather than Japanese (local) MDs, although in older affiliates it made little difference. When affiliate size was introduced there was no correlation with the IA status of the MD. Applying an alternative viewpoint, Riaz et al. (Citation2014) considered the effect of parent size on new subsidiaries’ sales performance related to IA numbers, finding that the larger the parent size the greater the positive effect.

Taking a different structural issue, the literature only considers MNCs. No research was found that investigated organizational value in other organizational types such as charities, religious organizations and public-sector bodies. The intra-organizational relationships within these parties may be distinctly different to those of MNCs due to structural differences, for example where a central charity HQ acts as the fundraising body for overseas activities or the political manifestations in an NGO (Y. Zhu & Purnell, Citation2006). Given that IA usage correlates with better subsidiary performance in times of environmental uncertainty and economic crisis (Chung & Beamish, Citation2005; Singh et al., Citation2019), we suggest host NGOs and charities will consistently derive high value from IAs because they operate in challenging and uncertain environments. Likewise the home entities will benefit because their purpose is often to assist others in such contexts (Barrett et al., Citation2017).

In conclusion, we suggest that the relational structure of the home and host affects the organizational value of IAs and yet there are inconsistencies and gaps in the research. For example, we argue that NGOs and international charities will generate more organizational value from IAs in both the home and the host on average when compared to MNCs. As an initial step we offer the following:

PROPOSITION ONE: The relational structure between the home and host will determine the organizational value of IAs to each party.

3.2. Operations

The second relational theme covers the operational activities of the home and host. The primary operational relationship question is the extent to which a host organization’s operations act on a standalone or integrated basis with the home – the localization versus globalization distinction (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Citation1989). Whilst some of the Subsidiary Performance literature uses IA numbers as a proxy for localization (see, for example Ando, Citation2014; Lam & Yeung, Citation2010) our theme of operational relationships considers the connectivity between the underlying practices of the parties. Roth (Citation1995) reported that CEO IA experience had a positive impact on firm performance and yet if group interdependence was low (as distinct to the interdependence between the home and the host which was not measured), then it had a negative impact on performance. In contrast, Richards (Citation2001) investigated the impact of interdependence of the subsidiary host with the parent home and found this had no impact on host performance related to expatriate versus local managing directors. At a more granular level of interdependence, Tan and Mahoney (Citation2006) identified that higher local product customization needs and lower local advertising intensity each correlated with greater IA use and hence indicated situations when the value to the subsidiary is highest. Similarly, Dutta and Beamish (Citation2013) found a curvilinear relationship between IA numbers and firm performance such that increasing IAs in the workforce improved performance up to a point after which it declined. Notably, this curvilinear relationship was positively moderated by the greater extent of product relatedness between the host (in this case IJVs) and its parent (the home), an operationally relational concept. In a similar vein Rodgers and Wong (Citation1996) found that where IAs were used to increase the lean manufacturing capability of overseas Japanese subsidiaries this had a positive effect on performance which did not arise without this mediation effect.

Colakoglu et al. (Citation2009) argued that the business strategy of the host subsidiary and its levels of operational innovation would affect IA organizational value. For example they argued that a low cost strategy or low levels of local innovation in host subsidiaries suggested an IA approach would have less value. This strategic operational relationship is consistent with Bonache Pérez and Pla-Barber (Citation2005) who found that if subsidiaries depend upon HQ centralized innovation there is a tendency to use more IAs, although they did not report on any value implications of this increase. Offering seemingly contradictory findings, Colakoglu and Jiang (Citation2013) identified no correlation between the home and the host having a shared vision and the value the host gained from IAs, despite finding that such a shared vision increased the use of IAs. Having a shared vision and a strategic relationship between home and host would seem to be an important relational question and yet the consequences on organizational value are unclear, especially given the lack of research on the impact to the home. We suggest that a complementary operational strategy between home and host would generate positive IA value outcomes for both parties when measured in the long term, i.e. taking into account the impact of repatriating assignees, and this might explain the inconsistent findings described above.

Building on Tan and Mahoney's (Citation2006) findings on advertising intensity, the marketing needs of the subsidiary host in combination with their technology needs, both of which affect the operational relationship between home and host, have been identified as affecting IA value. Fang et al. (Citation2010) found that the number of IAs in the workforce relative to the total number of subsidiary employees strengthened the effect of a parent firm’s technological knowledge on subsidiary performance in the short term (not in the long term), but weakened the impact of the parent firm’s marketing knowledge on subsidiary performance in the long term. Adding to the confusing picture regarding these relationships, Richards (Citation2001) reported that where the marketing themes in hosts were similar to the HQ, HCN-led subsidiaries outperformed IA-led ones.

Moving from the practicality of operational issues to issues of a company’s operational style and culture, studies have researched the extent to which IA value is captured as a result of the organization’s international approach. This has been conceptualized differently, e.g. as global mindset (Oddou et al., Citation2009) and operationalized differently, e.g. as global strategic posture (Carpenter et al., Citation2001) yet represents a relational issue. Findings support the argument that businesses with an international approach benefit the most from a CEO’s IA experience (plus the TMT’s IA experience where included). Overall, whilst the research base is limited, measuring a business’s international approach before deciding to implement an IA program could have positive impacts and logically this would affect both home and host depending upon their levels of involvement in this international approach.

Finally, the operational relationship can be considered in terms of the role a host takes within the overall organizational network and the relational consequences this may have. The Subsidiary Performance literature has argued that the role of the subsidiary as a manufacturer versus a sales-oriented entity may affect the impact of IAs (see, for example Kawai & Strange, Citation2014; Oki, Citation2020). Similarly, drawing on Birkinshaw and Morrison’s (Citation1995) conceptualization that subsidiaries may add different levels of value to products or services which could then trigger internal competition, Colakoglu et al. (Citation2009) argued these relationships would affect the value of IAs to the host. Consistent, however, with the themes already identified, they did not consider the impact beyond a recipient subsidiary, e.g. the home, peer-peer IAs or inpatriation.

In conclusion, research on the operational characteristics of the home and host offers contradictory findings and, importantly, ignores the impact on how value may be shared between the parties. However, when an overall organization has an international approach, an increase in IAs offers increasing organizational value after the IA, which is consistent with the positive IA value expectations when there is lower intra-organizational competition. Thus we suggest that globalization of an organization’s operations is likely to increase the organizational value of IAs and, as described above, a complementary operational strategy between home and host would generate value from IAs over the long term. For example, the greater the interdependence of the manufacturing processes between home and host, the greater the organizational value of IAs to both parties in the long run. Hence our second proposition is:

PROPOSITION TWO: The greater the interdependence of the operational relationship between the home and the host, the higher the value of IAs to all intra-group parties.

3.3. Human resource management

The HRM relationships within the parties involved in IAs represents the third relational theme we identified in the literature. Processes such as career and talent management are potentially critical to the organizational value of IAs, with repatriation and retention consistently identified as such (McNulty et al., Citation2009, Citation2013; Schmidt & Minssen, Citation2007). This also emphasizes how the organizational value of IAs may happen both during and after the IA. However, the relationship between repatriation and organizational value is not researched in any of the quantitative studies we identified. These practices clearly involve relational aspects given the levels of HRM interaction between the home and the host. The potential significance of retention on value appears consistent with the findings of the CEO/TMT Impact literature noted above, except that if the employing organization does not have an international approach then retaining the assignee may be a poor decision. Similarly, failings in the creation of differential career paths for repatriates within which to use their new skills (Schmidt & Minssen, Citation2007) may make retention moot and implies a disconnect between host and home HRM operations raising questions as to how the integration of HRM operations is affecting the organizational value of IAs. Furthermore, research to determine any relationship between repatriate retention and organizational value rather than relying on conceptual or presumed relationships would add considerably to the call for improving repatriation and retention processes (Lazarova & Tarique, Citation2005). Adding to the complexity, Carpenter et al. (Citation2000) argued that the very increase in IAs itself should have a positive impact on internal labor markets due to the faster promotion of those with IA experience reducing the need for external hiring. This might balance the negative effect of high attrition.

Performance and career management are identified as important organizational value determinants in Yan et al.'s (Citation2002) conceptual framework. This argues that the relationship between the assignee’s goals and the organization’s goals is fundamental to success, and is similar to Bonache and Noethen's (Citation2014) view that there should be a relationship between the difficulty of the IA task and the capability of the assignee. Whilst goal alignment is arguably operational, we would expect the HR function organizing IAs to be attuned to this. This may need further development, however, as once again these papers treat the organization as a single entity and also ignore where HRM operations sit. Hence the home-host HRM relationship question is overlooked. This raises questions as to the home and host HRM relationships and their accountability for performance and career management. For example, does an assignee’s career management shift from the home to the host and how does this affect future decisions on an IA? Alternatively is there a central HR function responsible for assignee career management? Meeting the psychological contract expectations of the assignee could also be incorporated here as a mediator for goal alignment, although there is uncertainty given evidence of assignees’ intentions to leave their host employer despite such expectations having been met (McNulty et al., Citation2013). More importantly, the existing research does not explore the relational distinction between home and host given their different potential impacts on the assignee’s psychological contract. What might the consequence be if the home HRM operations see the assignee as having ‘gone native’ at the host?

Whilst the work of HR in creating and subsidizing IAs affects the overall organizational cost of IAs (Nowak & Linder, Citation2016), research does not consider where these costs are borne, i.e. in the home, host or elsewhere. From a relational viewpoint, value is affected by whether IA process or remuneration costs are retained in a central HR function or distributed. This is especially the case with respect to assignee compensation levels which are widely recognized as being high compared to local hires (Toh & DeNisi, Citation2003). Drawing on Nowak and Linder's (Citation2016) arguments that understanding the organizational cost of IAs is critical to success, we suggest centralizing IA cost management (including remuneration) into an overarching HR function will bring greater corporate visibility to their costs and result in greater IA organizational value to all parties.

The uncertainty regarding the implications of HRM practices and how they impact upon the value to the home and the host suggests a need for further research. Drawing on the earlier findings regarding the positive impacts of operational globalization plus the coordination requirements of many HRM IA practices with the home and host, we suggest:

PROPOSITION THREE: The integration of HRM operations and IA practices between the home and the host will increase the value captured by each party from IAs.

3.4. Organizational capabilities

The previous relational themes are internal and have a structural and functional focus. We now turn to consider the broader organizational capabilities of the home and host as the final internal theme identified. The role of knowledge transfer (KT) is fundamentally relational as it implicitly assumes different levels of knowledge between the parties for KT to arise. The ROI literature has identified KT as a benefit of IAs (McNulty et al., Citation2013) and a recent conceptualization of the KT issues for IAs identifies knowledge transferred to the host subsidiary, knowledge sustained by the host subsidiary and knowledge transferred to the home organization thereby supporting the importance of taking a relational perspective (Gonzalez & Chakraborty, Citation2014). Gonzalez and Chakraborty conceptualized a positive relationship of KT with absorptive capacity in the host subsidiary, while Kawai and Chung (Citation2019) argued that the host’s ability to absorb new knowledge from assignees effectively into the host’s activities is key to the value achieved from KT. Whilst these papers focus on the host subsidiary we draw on Oddou et al.'s (Citation2009) view of the home organization post repatriation to suggest that the absorptive capacity of the home or other affected sister companies is also key to their respective IA organizational value derived from KT.

Despite support for this KT phenomenon (Fang et al., Citation2010; Wang et al., Citation2009), research on the KT creation mechanism for IAs in host subsidiaries and IJVs has triggered contradictory evidence. For example, Colakoglu and Jiang (Citation2013) found no correlation between KT from IAs and subsidiary performance, whilst Chang et al. (Citation2012) found that assignee competencies in KT enhanced subsidiary performance through knowledge received, but there was no correlation between the numbers of IAs and subsidiary performance unless the subsidiaries had high absorptive capacity. Lyles and Salk (Citation1996) found similar results for Hungarian IJVs. Chang et al. (Citation2012) suggested this may be a result of companies using IAs predominantly for technical or task-based reasons and hence these assignees may not have the appropriate KT skills. This illustrates the usefulness of Wang et al.'s (Citation2009) findings that international assignees possessing the motivation and adaptability for KT had a positive correlation with subsidiary success (which was mediated by the KT). This complexity suggests caution for global businesses relying on KT for value.

Turning to a different organizational capability issue, studies have found conflicting evidence on the impact of the home’s knowledge and experience of the host country and industry when using IAs. Tan and Mahoney (Citation2006) identified that lower host experience of the home correlated with greater IA use and hence indicated situations when the value to the subsidiary is highest. However, Hebert et al. (Citation2005) found that the home’s prior experience of the host country had no effect on the value of IAs and yet Goerzen and Beamish (Citation2007) found that an increase in the parents’ prior experience in the host country correlated with an increase in expatriate numbers generating greater subsidiary performance. Both Hebert et al. (Citation2005) and Riaz et al. (Citation2014) found that the parent’s experience of the industry within which the subsidiary sat, had a positive effect. Once again the overall picture is unclear and we suggest that the explanation may sit in research which investigates the organizational value of IAs on the home and other sister companies as well as that on the host recognizing the growing number of IAs which are not in the traditional HQ-subsidiary direction.

In conclusion, there is uncertainty and contradiction in our understanding of what or how organizational KT, and knowledge and experience capabilities determine the value of IAs to the home and host. For example, it might be that the greater the sectoral experience of the overall organizational group, the greater the organizational value of the parties affected by IAs when assessed in combination and in the long run. Relevant IA research to date is unidirectional – looking only at the value to one party. This suggests:

PROPOSITION FOUR: The effectiveness of the home and host’s organizational capabilities will determine the organizational value to all parties.

Whilst our analysis so far draws attention to the primacy of the internal relationships between the home and the host, these relationships sit within a broader external relational context. We now turn to consider this final theme.

3.5. External relational factors

Whilst McNulty and De Cieri (Citation2011) conceptualize the home-host organization as a single entity, the significance of external factors on the organizational value of IAs is directly recognized within their systems-based framework for ROI in IAs. Looking across the research in this field, the range of external factors affecting the home-host relationship and hence the organizational value of IAs is significant. For the purposes of our paper we summarize these as (1) the customers, the competition, and the market; (2) the cultural or institutional distance between the home and the host and (3) the assignee. We first consider the literature on the customers, competition and market.

Richards (Citation2001) identified that subsidiary hosts benefited more from IAs when they had more international customers whereas HCN-led subsidiaries performed better with more local customers. As regards the competitive nature of the host’s market place, McNulty and De Cieri (Citation2011) identified the potential for impacts on IA value from inter-organizational networks and alliances, environmental volatility and dynamism. This aligns with Bouquet et al.'s (Citation2009) findings that increased industry dynamism increases the positive effect of CEO/TMT attention on subsidiaries, which is important because CEO/TMT IA experience was identified as a key determinant of this attention.

Considering the implications of the external market on IA value, Chung and Beamish (Citation2005) researched the impact of economic crises. They identified that in such a crisis the number of expatriates in a subsidiary is positively related to the survival of that subsidiary and that this arose more so with greenfield joint ventures and acquired WOS than greenfield WOS. However, while this positive interaction effect is significant in an economic crisis, it is not significant in an economically stable situation which is consistent with the findings of Lam and Yeung (Citation2010) who investigated uncertainty in the business environment. This raises practical challenges however, regarding a firm’s ability to predict these situations with sufficient time to organize IAs.

The effect of cultural and institutional distance on the value of IAs was considered by several articles investigating host subsidiary performance (Colakoglu & Caligiuri, Citation2008; Hyun et al., Citation2015). These articles make the implicit assumption that the distance between organizations is the same irrespective of the directionality or the specific in-country location – a construct validity problem raised by several scholars (see, for example, Tung, Citation2016) and magnified where the method identifies only the assignee’s assumed country of birth not the home organization (see above).

Whilst the impact of cultural differences has been found to have an interactive effect on the IA-subsidiary performance relationship, findings are inconsistent. Some authors (Gaur et al., Citation2007; Gong, Citation2003a; Riaz et al., Citation2014) found that the positive effect of IA’s increased as cultural distance increased (including normative distance and regulative distance). Others found no correlation (Bonache Pérez & Pla-Barber, Citation2005). Colakoglu and Caligiuri (Citation2008) found that a correlation only existed when cultural distance was taken into account, but was in the opposite direction, i.e. subsidiary performance reduced as cultural distance increased. Richards (Citation2001) found similarly contradictory evidence comparing the performance impact between subsidiaries of US companies in Thailand and the UK with, for example, host country national-led subsidiaries in Thailand outperforming those that were IA-led in both the UK and Thailand. To add further uncertainty Gaur et al.'s (Citation2007) findings regarding institutional distance were commensurate with Colakoglu and Caligiuri (Citation2008) at the workforce level (firm performance reduced as distance increased) but positive at the General Manager level. In summary, more research on these issues is required before conclusions on the impact of cultural or institutional distance can be drawn.

The relevance of market and competitive conditions also influences the possibility that the home and host may not retain all the value generated by IAs if other organizations poach their assignees. Most of the CEO/TMT Impact literature ignores whether the IA experience was in the same company within which the CEO/TMT position was held and Daily et al. (Citation2000) found that the positive relationship between CEO IA experience and firm performance was moderated by outside succession. A similar issue is the assignees’ ability to capture some organizational value through proactively changing employer or renegotiating salaries prompted by competitive markets (Dickmann & Doherty, Citation2010; Welch et al., Citation2009). Indeed, Carpenter et al. (Citation2001) found that CEOs with IA experience obtained higher pay although only if the firm had a global strategic posture. This suggests that the greater the competition for talent in a particular industrial sector, the lower the long-term IA organizational value to the home and host due to the poaching of employees. It also indicates that many factors regarding the assignees’ personal attributes, such as their motivation and adjustment will also affect the organizational value to the home and host.

The uncertainties in these external relationships suggest a need to draw together the issues to extend our understanding of the conceptual possibilities. Many relational factors merit further research indicating the importance of in-depth qualitative research. For example, we might find that as the level of competition for managerial talent in their respective markets increases, the overall group organizational value of IAs reduces. As an initial step we suggest:

PROPOSITION FIVE: The organizational value of IAs to each of the home and the host will vary depending upon factors external to the organizations.

Having identified five relational factors regarding the value that is generated through IAs, in the next section we examine: what is the total value across an organization, how is this shared, when does it arise and how do other parties, namely the assignees and other businesses, share in this value?

3.6. What value is generated?

An examination of the types of organizational value that IAs create confirms the importance of taking a relational view. This value has been interpreted from two primary perspectives: the host, and the organization as a whole, which we refer to as the group (assuming, as per the literature, that the host and home are in the same group of companies). Despite recognition that they may be affected (Welch et al., Citation2009) the papers provided no clarity as to whether value occurs simultaneously in different organizational parties as they analyze the parties separately and have not investigated the home as a distinct entity. As discussed earlier, relational aspects are regularly acknowledged yet research effectively ignores one half of the home-host relationship in their value calculations in addition to the parties beyond this central dyad.

Value to the host is identified, rather than defined, through the Subsidiary Performance literature in terms of organizational performance (Richard et al., Citation2009). As described earlier, most of the assumptions used to identify participants as expatriates could not differentiate which home entity was involved and no analysis was undertaken as to the value implications on the home(s) losing staff through an intra-organizational, international move. In any event, the underlying findings indicate contradictory evidence with some reporting an increase in the number of IAs in a subsidiary correlated with decreased performance (Distel et al., Citation2019; Tao et al., Citation2018) and others reporting increased performance (Chung & Beamish, Citation2005; Gong, Citation2006; Hyun et al., Citation2015). However, the majority of the latter establish that this value only exists if certain relational characteristics are present as discussed above.

The value to the host is measured or identified through increases in labor productivity, profitability, sales volumes, market share, performance compared to parent company expectations, long term subsidiary survival and return on equity (ROE) (see, for example, Chang et al., Citation2012; Gong, Citation2003a; Konopaske et al., Citation2002). These cross-sectional survey-based research designs raise issues as to the direction of causality – do successful firms use more IAs? The CEO/TMT Impact literature acknowledges the causality issue and identifies value at the group level in similar terms, for example, average income growth over five years, ROI, pre-tax ROE, market-to-book ratio, return on assets, return on sales and total stock market returns (see, for example, Daily et al., Citation2000; Roth, Citation1995). In contrast, the ROI literature identifies non-financial factors with capability development, incorporating improved knowledge transfer (KT) and networking capabilities as primary examples (McNulty et al., Citation2013) and offers formulaic and descriptive definitions of the organizational value – although treating the MNC as a single entity (McNulty & De Cieri, Citation2016; McNulty & Tharenou, Citation2004).

In line with the ROI literature, the organizational value identified in the Subsidiary Performance literature exists both during (Fang et al., Citation2010; Konopaske et al., Citation2002) and after the IA (Chang et al., Citation2012; Hebert et al., Citation2005) and, whilst variations exist, evidence supports positive effects at different levels, e.g. the subsidiary workforce, CEO and TMT level. For example, Hocking et al. (Citation2004) tested the relationship between the intended purpose of workforce IAs to subsidiaries and their outcomes. They identified a positive relationship which increased as the IA duration increased. However, this study did not validate any relationship between the desired outcomes and organizational value and ignored how IA costs are borne. This cost issue is a critical relational question and is only considered explicitly in a small number of papers (Benito et al., Citation2005; Nowak & Linder, Citation2016). If, for example, costs are borne centrally then any host value may be misleading when compared to total net organizational value giving a different outcome for business efficiency.

The CEO/TMT Impact literature offers ‘consistent evidence that CEO international experience is positively related to corporate financial performance’ (Daily et al., Citation2000, p. 520). However, this value arises after the IA experience and may be in different companies if the assignee has changed employer. Furthermore, without time series data including costs and benefits involving all relevant employers, there is a risk that the true organizational value of the IA is not being fully documented. Similarly, the consequences for global business may be substantial if, for example, they assessed IA impacts based only on the host and ignored lost productivity at the home or centralized HR costs funding IA programs.

Businesses do not appear to calculate the organizational value of IAs and the factors limiting this are operational (e.g. lack of data), cultural (e.g. such a calculation is not required) and strategic (e.g. no party is accountable for this) (McNulty et al., Citation2009). Nonetheless, several enabling conceptual frameworks exist for the measurement of the organizational level of value (see, for example Hemmasi et al., Citation2010; Nowak & Linder, Citation2016; Schiuma et al., Citation2006). Acknowledging the different organizational and individual goals and their inter-relationships, these offer a range of calculations in order to manage and measure the effects of IA value. Nonetheless, these frameworks treat the organization as a single entity without separating the home and the host, or other organizational entities. The narrative needs to change to include a relational view.

In summary, using a relational lens, the most significant issue identified on how IA organizational value is defined and researched was the failure to consider the separate and interactive effect on the home, host and other intra-organizational entities. This includes questions on the timing of that value between the disparate parties and any internal competition that may arise to capture this value. We now draw together our analysis to offer a relational framework for the organizational value of IAs in line with our research question.

3.7. The relational framework

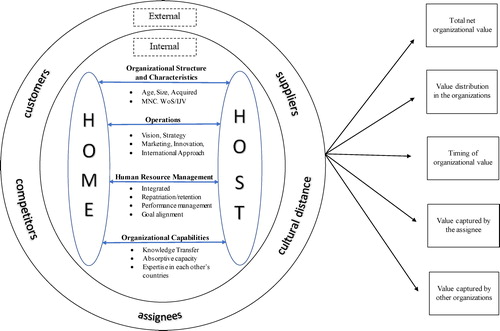

We have identified four internal and one external core relational themes underpinning extant knowledge on the organizational value of IAs within which the home-host dyad sits at the center. This is presented as an overarching framework in . In each case, examples drawn from our review of the literature are included in each theme. The first theme is Organizational Structure incorporating issues such as the investment relationship of the parties, e.g. is the host a wholly-owned subsidiary of the home or an IJV? The subsequent themes look at the localization versus globalization distinctions under two categories: Operations and Human Resource Management. Following on from these functional perspectives, the fourth theme considers the Organizational Capabilities of the home and host, for example their knowledge transfer competencies. The final theme, potentially impacting each of the first four, considers External Factors such as customers, competitors and suppliers.

Figure 2. Relational Framework for the Organisational Value of IAs, including example variables by theme.

As shown on the right-hand side of the framework and drawing from our review in Section 3.6 above, these relational themes all have the potential to affect the total organizational value generated, how this value is distributed, the potential for different internal and external parties to capture this value (including the assignee) and the timing of this value.

4. Discussion and future research agenda

This paper sought to address whether there is a relational underpinning to the organizational value of IAs and if so to develop a relational framework to improve our understanding of current knowledge. Our review has demonstrated that whilst understated, the relationship between the home, the host and the context within which they sit is fundamental to the organizational value of IAs and that one part of the relationship is consistently overlooked. Drawing on three streams of literature we have provided a relational framework to explicate extant knowledge and advance initial exploratory propositions. We argue that a relational view highlights the critical factors that need addressing in future research on IA organizational value.

Many of the findings to date regarding the relational impacts on IA organizational value have been contradictory or inconsistent. Our initial propositions address issues including the structural relationships in NGOs and international charities compared to MNCs, intra-organizational KT levels and the HRM relationships between the parties. There are also notable gaps in existing research which become more apparent when taking a relational perspective. We turn now to suggest a future relational research agenda.

4.1. Value for whom

There is no empirical analysis of the organizational value derived through the use of IAs at the home organization or the impacts on other group organizations not involved in the IAs. Whilst the focus on subsidiary performance is valid in that literature, it does not help with the understanding of total value to the organizations involved. This is a fundamental issue in moving forward IA organizational value research. It is feasible that value generated in a subsidiary due to the arrival of IAs causes a reduction in the value generated in other group operations without IAs (Colakoglu et al., Citation2009). There may also be regional impacts worthy of investigation when, for example, different countries are jointly led by a single regional Managing Director whose interests differ to those of another regional Managing Director. Similarly, corporate headquarters may suffer as a result of sending its best people overseas to the benefit of local operations. Furthermore, analysis of IAs in non-traditional short-term alternatives, e.g. business travelers or commuters, is not considered and only Zaharie et al. (Citation2019) has investigated the inpatriation-expatriation relationship. The IA organizational value in these circumstances may be affected by several relational factors, e.g. the role each organization plays within the overall group (Colakoglu et al., Citation2009) or the volume of IAs in the host country sent by other organizations and any interaction effect on performance (Ge et al., Citation2019). New research in all these aspects could bring clarity.

4.2. Value for other home-host relationships

Possibly due to the complexity of research design, there are no studies considering the organizational value generated in relation to (a) when one group implements the IA and another separate group subsequently employs the assignee and derives benefit from that experience, (b) inter-organizational IAs, i.e. where an assignee moves between completely separate organizations or (c) the impacts when a host organization is involved in a merger or acquisition thereby joining a new MNC. Given the increasing interest in global supply chains and coopetition within and between organizations (see, for example Luo, Citation2005) combined with the numbers of global M&A transactions, there may be innovative IA examples to consider here.

4.3. Ownership structure

Building on the potential impacts of M&A activity, most research does not meaningfully explore the ownership implications in their study of IA organizational value, e.g. whether wholly owned or otherwise. Rather, they often simplify the analysis into WOS versus non-WOS assessments and also implicitly assume any IJV partners are host-country entities which may not be the case (see, for example Singh et al., Citation2019). In contrast, Dutta and Beamish's (Citation2013) study of 20–80% owned US located JVs of Japanese firms found a curvilinear relationship between IA numbers and firm performance such that increasing IAs in the workforce improves performance up to a point after which it declines. Research confirming such an optimal point combined with ownership structure implications would be highly beneficial.

4.4. IA objectives

Extant research does not investigate the potential for different value outcomes depending upon the purpose of the IA or capability of the assignee. And yet assignees are sent for different reasons as Edström and Galbraith (Citation1977) first suggested and these sit within a relational framework. If, for example, the host retains technical expertise for an MNC, say in manufacturing components, this relationship affects the decisions on who to send on IA and the direction in which to send them. With a growing focus on the shortage of global talent and hence talent development programs providing IA opportunities to high-potential employees (Cerdin & Brewster, Citation2014) this distinction may be significant. Similarly we can learn more from understanding the alignment of purpose, or objectives, between the assignee and the home and the host and the value consequences for each party.

4.5. Temporal considerations

Finally, no empirical research investigates whether organizational value arises at the same time in the host, the home, the assignee and across the whole organization. The Subsidiary Performance papers primarily investigate CEO/TMT assignees at the host level in the traditional parent-subsidiary direction whereas the CEO/TMT Impact papers investigate the CEO/TMT at the HQ level subsequent to the IA. If high costs were suffered by the company funding the IA, which could be in a different group, the total net value has not been determined. Finally, the existence of the expatriation cycle suggests that value might arise to the home, host and other organizational entities both during and after the IA. Subsidiary Performance papers regularly use time-based data, but they only investigate the impacts on the host subsidiaries. Latent effects on the host and the home may be difficult to identify and yet these still form part of the value equation. Hence longitudinal studies which continue to track the relationships between the organizational parties, combined with the relationships between technical benefits and managerial benefits, would add considerably to our understanding of these issues.

We now turn to the implications of our relational framework on HRM and Global Mobility practitioners responsible for IA implementation and strategy.

5. Implications for HR practitioners

There are multiple practical implications for HR professionals in taking a relational view when considering IA organizational value. The fundamental implication is that the impacts on the home and host may differ and be in conflict, so value has to be considered both separately and collectively with appropriate HR systems in place to limit and manage any conflicts that arise. Investments in IAs are costly (Doherty & Dickmann, Citation2012) and take many different forms depending on the duration, sending unit, host location, or function in the destination country (Baruch et al., Citation2013). The purpose of an IA has a bearing on the value outcomes. In their strategic considerations, therefore, HR professionals should assess the various IA options and choose the most beneficial one for the group as a whole, through analyzing the parts. For instance, this would allow them to compare the likely value of a long-term control and coordination IA, where the expatriate develops a local successor, with that of a developmental assignment. Such business case considerations could be designed using a relational framework.

In addition, understanding value, value creation processes and value capture mechanisms has many HRM process implications. Sophisticated assignee selection and preparation, expatriation rewards and benefits, performance management, long-term career approaches and repatriation mechanisms have an impact on the value generated (Carpenter et al., Citation2000; Dickmann & Baruch, Citation2011; Harris & Brewster, Citation1999). A better understanding of individuals, their preferences and strengths (Doherty et al., Citation2011) as well as an appreciation of the host and home relational context and the potential preparation of host teams will affect IA value. Thus, HR professionals should develop a more in-depth appreciation of the value implications throughout the expatriate cycle and create more tailored solutions. For example, HR can have much deeper discussions regarding assignee goals and objectives, and their relational implications, in addition to tracking success with all the parties seeking to gain from the IA. Over time, this could lead to an increased individualization of IAs and more sophisticated global mobility practices. Overall, an improved understanding of what IA value is, where, when and to whom it accrues combined with the relational factors that affect this value could strengthen global mobility outcomes.

6. Conclusions and limitations

We proposed that implicit in the extant literature is a relational perspective which, when exposed to daylight, will improve our understanding of IA organizational value, its contradictions and its uncertainties. We identified and brought together three literature streams which address this phenomenon and yet do not appear to have been previously considered collectively. This enabled the key contribution, namely to illuminate the importance of taking a relational view when investigating the organizational value of IAs combined with the presentation of an integrative relational framework. This places the home-host intra-organizational relationship at its center whilst recognizing that this sits within a broader relational context with external factors. We provided exploratory research propositions using the relational framework and a research agenda to move our understanding of this vital topic forward. Finally, we identified key issues for HR functions and global mobility professionals to address. Taking a relational view allows us to identify the research and practical implications for IAs and the organizational value derived for the parties involved. Future research on the topic needs to take these into account and can no longer consider the value to one party without questioning what happens to others.

Whilst much is known from 30 or more years of research there is considerable uncertainty regarding the organizational value generated by IA interventions. The literature offers many examples of value being generated at the subsidiary level and yet it is uncertain whether sister entities or the overall group of companies benefit as the literature implicitly assumes the cost of IAs sits in the host subsidiary. Furthermore, there are many questions as to what relational features are needed to capture this value. Having an international approach is supported and presents a clear opportunity for HR functions to work within businesses to achieve this and hence capture value from IAs. However, whilst retention of the assignees after the IA is regularly reported as a process that is expected to capture value, there is limited research to support this. Similarly, there is inadequate information regarding how the organizational structure, the operational and HR needs of individual host organizations and the home/host capabilities might affect the outcomes. Our framework depicts these key elements and allows a more holistic assessment of the organizational value of IAs.

Taking a relational viewpoint may have its limitations. In aiming to address all the relational issues involved in IAs it may create research designs that are too complex to pursue. Hence the inter-relationships between the many different aspects may be beyond existing research capabilities. Similarly, practitioners may not be able to apply attention to all of the possibilities. Currently, however, practitioners appear to be making limited if any progress as the same issues continue to arise in surveys and hence a relational view may offer a useful place from which to start. Furthermore, simply focusing on and prioritizing one party such as the host over the home, has significant weaknesses as we have identified above. We also acknowledge that the concept of ‘value’ itself is difficult to define and that we have interpreted literature as being consistent with our definition when the papers themselves often do not use this terminology. Ultimately, whilst research may need to move forward on a step by step basis, simply incorporating the value impact on the different organizational parties involved would be an important step.

From a practitioner perspective, the uncertainty as to when, where or indeed whether there is any net value generated for organizations through their use of IAs raises uncomfortable questions. Above all, the authors hope that the issues discussed and insights developed serve to guide future research to address these challenges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- Ando, N. (2014). The effect of localization on subsidiary performance in Japanese multinational corporations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(14), 1995–2012. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.870289

- Barrett, M., Cox, A., & Woodward, B. (2017). The psychological contract of international volunteers: An exploratory study. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 5(2), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-03-2017-0009

- Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1989). Managing across borders: The Transnational Solution. Harvard Business School Press.

- Baruch, Y., Dickmann, M., Altman, Y., & Bournois, F. (2013). Exploring international work: Types and dimensions of global careers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(12), 2369–2393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.781435

- Beamish, P. W., & Inkpen, A. C. (1998). Japanese firms and the decline of the Japanese expatriate. Journal of World Business, 33(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(98)80003-5

- Belderbos, R. A., & Heijltjes, M. G. (2005). The determinants of expatriate staffing by Japanese multinationals in Asia: Control, learning and vertical business groups. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(3), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400135

- Benito, G. R. G., Tomassen, S., Bonache-Pérez, J., & Pla-Barber, J. (2005). A transaction cost analysis of staffing decisions in international operations. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 21(1), 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2005.02.006

- Birkinshaw, J. M., & Morrison, A. J. (1995). Configurations of strategy and structure in subsidiaries of multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(4), 729–753. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490818

- Björkman, I., Barner-Rasmussen, W., & Li, L. (2004). Managing knowledge transfer in MNCs: The impact of headquarters control mechanisms. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400094

- Bonache, J., & Noethen, D. (2014). The impact of individual performance on organizational success and its implications for the management of expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(14), 1960–1977. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.870287

- Bonache, J., & Zárraga-Oberty, C. (2017). The traditional approach to compensating global mobility: Criticisms and alternatives. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1), 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1239123

- Bonache Pérez, J., & Pla-Barber, J. (2005). When are international managers a cost effective solution? The rationale of transaction cost economics applied to staffing decisions in MNCs. Journal of Business Research, 58(10), 1320–1329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2004.05.004

- Bouquet, C., & Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Weight versus voice: How foreign subsidiaries gain attention from corporate headquarters. Academy of Management Journal, 51(3), 577–601. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.32626039

- Bouquet, C., Morrison, A. J., & Birkinshaw, J. (2009). International attention and multinational enterprise performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(1), 108–131. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.64

- Bowman, C., & Ambrosini, V. (2000). Value creation versus value capture: Towards a coherent definition of value in strategy. British Journal of Management, 11(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00147

- Briner, R. B., Denyer, D., & Rousseau, D. M. (2009). Evidence-based management:Concept cleanup. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(4), 19

- Caligiuri, P. M., & Bonache, J. (2016). Evolving and enduring challenges in global mobility. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.10.001

- Capaldo, A. (2007). Network structure and innovation: The leveraging of a dual network as a distinctive relational capability. Strategic Management Journal, 28(6), 585–608. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.621

- Carpenter, M. A., & Sanders, W. G. (2004). The effects of top management team pay and firm internationalization on MNC performance. Journal of Management, 30(4), 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.02.001

- Carpenter, M. A., Sanders, W. G., & Gregersen, H. B. (2000). International assignment experience at the top can make a bottom-line difference. Human Resource Management, 39(2-3), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-050X(200022/23)39:2/3<277::AID-HRM15>3.0.CO;2-0

- Carpenter, M. A., Sanders, W. G., & Gregersen, H. B. (2001). Bundling human capital with organizational context: The impact of international assignment experience on multinational firm performance and CEO pay. Academy of Management Journal, 44(3), 493–511. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069366

- Cerdin, J.-L., & Brewster, C. (2014). Talent management and expatriation: Bridging two streams of research and practice. Journal of World Business, 49(2), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.11.008

- Chang, Y.-Y., Gong, Y., & Peng, M. W. (2012). Expatriate knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity, and subsidiary performance. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 927–948. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0985

- Chung, C. C., & Beamish, P. W. (2005). Investment mode strategy and expatriate strategy during times of economic crisis. Journal of International Management, 11(3), 331–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2005.06.003

- Colakoglu, S., & Caligiuri, P. M. (2008). Cultural distance, expatriate staffing and subsidiary performance: The case of US subsidiaries of multinational corporations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(2), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190701799804

- Colakoglu, S., & Jiang, Y. (2013). Subsidiary-level outcomes of expatriate staffing: An empirical examination of MNC subsidiaries in the USA. European J. of International Management, 7(6), 696–718. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2013.057107