Abstract

The study investigates to what extent empowering HRM practices (i.e., workplace flexibility, professional autonomy, and access to knowledge via ICT) and empowering leadership have the potential to motivate employees in displaying workplace proactivity in NWW contexts. The study builds on the empowerment theory to gain a better understanding of how employees are able to make choices in order to achieve the goals set in their work and how leadership can support this. A field study was conducted in four subsidiaries of a large Dutch bank active in the financial sector. In line with expectations, positive relationships were found between professional autonomy, access to knowledge via ICT and empowering leadership, on the one hand, and psychological empowerment, on the other. Also, in line with expectations, a positive relationship was found between psychological empowerment and workplace proactivity. Moreover, as hypothesized, psychological empowerment partly mediated the relationship between the HRM practices and empowering leadership and workplace proactivity. However, autonomy had a direct, negative effect on workplace proactivity. Also workplace flexibility was neither directly nor indirectly associated with workplace proactivity. Finally, HRM and leadership can be viewed as complementary as they combine different perspectives for employees in order to display proactive workplace behaviour. In conclusion, the empowerment process approach helped to disentangle the motivating elements that foster workplace proactivity in modern workplaces.

Introduction

Organizations are increasingly implementing new ways of working (NWW) in their response to the agile and dynamic work environment pushed by new technologies, artificial intelligence and digitalization. In order to enhance organizational agility in highly unpredictable and complex markets, employees’ workplace proactivity has become more and more a necessity (Binyamin & Brender-Ilan, Citation2018). Workplace proactivity refers to employees’ ability to take self-directed action to anticipate changes in their work and to respond to future possibilities instead of undergoing developments passively (Crant, Citation2000). However, workplace proactivity is not something that happens automatically; employees must be abled, motivated and given the opportunity to enact specific proactive behaviours in the workplace (Appelbaum et al., Citation2000; Parker & Wu, Citation2014).

Over the past decades, many organizations have established empowering Human Resource Management (HRM) practices that are based on trust and that are assumed to motivate employees by offering and sharing autonomy, workplace flexibility and providing access to information via information and communication technologies (ICT; Peters et al., Citation2014). These empowering HRM practices can comprise flexible work arrangements known as NWW (e.g. Gerdenitsch et al., Citation2015; Van der Heijden et al., Citation2014). NWW offers workers electronic tools and ICT which enable them to share their knowledge with peers inside and outside their organizations (Coun et al., Citation2019; Ten Brummelhuis et al., Citation2012). Empowering HRM practices can enhance employees’ autonomous work motivation, which in turn can foster workplace proactivity and thus the generation of creative and innovative ideas. However, studies that linked the HRM system or HRM practices to workplace proactivity (e.g. Arefin et al., Citation2015; Batistič et al., Citation2016; Chen et al., Citation2017) mainly focused on practices such as selection, training and reward systems which can be used to monitor and indirectly control people (Peters et al., Citation2016) rather than on HRM practices which can be expected to motivate employees. Therefore, more empirical evidence is needed to determine how single empowering HRM practices (i.e. workplace flexibility, professional autonomy and access to knowledge via ICT) can encourage workplace proactivity in an NWW context, and to determine what the underlying mechanisms are.

In addition to empowering HRM practices, empowering leadership may also play a role in encouraging workplace proactivity (Parker et al., Citation2010; Parker & Wu, Citation2014). NWW and remote working often require leadership to shift from direct supervision and top-down control to more indirect forms of leadership (Peters et al., Citation2014). That is, in the context of NWW, leaders can no longer simply instruct their employees to be more proactive, but they have to empower them to display workplace proactivity and emphasize employees’ self-influence and self-directness (Sharma & Kirkman, Citation2015). Empowering leaders can facilitate and support employees by sharing broader responsibilities and decision-making authority, allowing them to plan their work and make their own decisions (Hill & Bartol, Citation2016). Although there is an increasing research interest in empowering leadership (cf. Kim et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2018; Sharma & Kirkman, Citation2015), only few studies have investigated the relationship between empowering leadership and workplace proactivity (Martin et al., Citation2013; Schilpzand et al., Citation2018). Hence, more empirical evidence is needed to explain the relationship between empowering leadership workplace proactivity.

In order to explain how both HRM practices and empowering leadership contribute to workplace proactivity, the empowerment literature can be helpful. Within this body of literature, empowerment is commonly conceptualized in terms of either a structural or a psychological approach (Leach et al., Citation2003; Menon, Citation2001). The structural approach to empowerment typically focuses on organizational and managerial conditions which relate to sharing informal power and information, access and control over resources and rewards, and on the leaders who design them (Bowen & Lawler, Citation1992). The psychological approach to empowerment focuses on how employees experience their work. When employees make positive assessments in terms of a set of four cognitions (i.e. meaning, competence, self-determination and impact) that reflect their orientation to work, higher levels of intrinsic task motivation can be achieved, and, therefore, they feel more psychologically empowered (Spreitzer, Citation1995; Thomas & Velthouse, Citation1990). Rather than focusing on managerial practices in which power and information are shared with employees at all levels, the psychological perspective is focused on how employees experience their work. In the present study, we will use the empowerment process approach that integrates these two approaches (Conger & Kanungo, Citation1988; Fernandez & Moldogaziev, Citation2013; Spreitzer, Citation1995, Citation2008) to explain the mechanisms by which empowering HRM practices and empowering leadership may contribute to employees’ workplace proactivity.

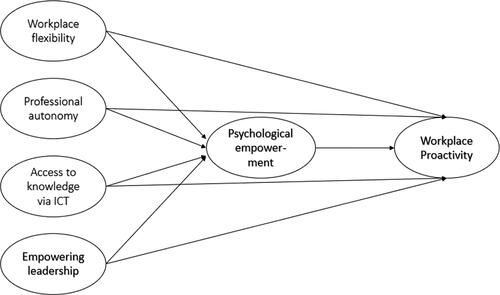

In view of the literature discussed above and building on the process approach to empowerment, the present study examines how both empowering HRM practices (i.e. professional autonomy, workplace flexibility and access to knowledge via ICT) and empowering leadership may have the potential to foster workplace proactivity, directly and/or indirectly through psychological empowerment.

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, by simultaneously investigating how both HRM practices and leadership might foster workplace proactivity, the present study connects the HRM and leadership literature (Leroy et al., Citation2018). Whereas HRM is more focused on the processes and systems in an organization and leadership is more closely related to the individual employee, this study wants to foster our understanding of how HRM and leadership contribute to influencing employee outcomes. Second, by drawing on empowerment as a process approach (Conger & Kanungo, Citation1988; Fernandez & Moldogaziev, Citation2013; Spreitzer, Citation1996), we test and uncover explanatory mechanisms that show how HRM practices (i.e. workplace flexibility, professional autonomy and access to information via ICT) and empowering leadership contribute to proactive workplace behaviour. Finally, we extend previous workplace proactivity research by examining to what extent both empowering HRM practices and empowering leadership may affect employees’ workplace proactivity (Bindl & Parker, Citation2010; Parker et al., Citation2010).

Theoretical background and hypotheses

The direct relationship between empowering HRM practices and workplace proactivity

Workplace proactivity, which has become increasingly important in today’s global work context, is a type of motivated and change-focused work behaviour that can foster self-initiation (Bateman & Crant, Citation1999). This implies that employees take self-control and anticipate problems rather than passively wait for problems that can occur or for instructions that can be given (Crant, Citation2000). Parker and Collins (Citation2010) have characterized workplace proactivity as future and change oriented, comprising behaviours such as taking charge, expressing voice, showing individual innovation and demonstrating problem prevention. Taking charge refers to employees’ efforts to realize change with respect to how the work is executed. Expressing voice is concerned with speaking out and seeking information about issues in the work context. Individual innovation focuses on novelty in order to influence the work context. Finally, problem prevention is related to the way in which challenges and obstacles in the work environment are dealt with (Parker & Collins, Citation2010). In the context of NWW, organizations have adopted empowering HRM practices (in this study, workplace flexibility, professional autonomy and access to knowledge via ICT) to stimulate workplace proactivity, since this enables employees to make choices about their work and encourages them to take initiatives when it comes to solving problems and changing the current circumstances beyond their work-related tasks. These relationships will be discussed below.

The concept of workplace flexibility is related to that of time-spatial flexibility, referring to ‘when’ and ‘where’ employees work (Gerdenitsch et al., Citation2015; Hill et al., Citation2008). Employees have the freedom and independence to decide when the work is carried out and for how long work is performed. In addition, employees have various options for where to do their work, both outside and within the office environment. In the context of telework and flexible work, Kelliher and Anderson (Citation2010) argued that employees work harder to give something back to the organization in gratitude for the flexibility they have received that allows them to better deal with their challenges at work and at home. In a similar vein, giving employees the opportunity to work flexibly might enhance their feelings of being supported, which might encourage them to display workplace proactivity. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1a: Workplace flexibility has a positive relationship with workplace proactivity.

A concept related to workplace flexibility is professional autonomy, which refers to the extent of control that employees have over ‘how’ to perform and execute work (Gerdenitsch et al., Citation2015; Sardeshmukh et al., Citation2012). Particularly important is the degree to which the job provides freedom and discretion for the employee in scheduling his/her work, in decision making and in determining how the work can be carried out (Hackman & Oldham, Citation1976; Morgeson & Humphrey, Citation2006). Yet, employees who have more freedom also face a number of responsibilities that emerge from particular agreements about achieving results. In fact, work results and output from work are more important than the number of hours actually worked (Peters et al., Citation2009). Peters et al. (Citation2014) pointed out that in recent decades, accountability concerning the execution of work activities has increasingly shifted towards the employee. Professional autonomy, viewed as a job resource, can therefore generate positive employee outcomes (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). Moreover, Parker et al. (Citation2006) consider job autonomy to be an important factor for proactive workplace behaviour. When employees experience that they have control over their work and are involved in challenging tasks, they may experience a work climate that fosters proactive work (Coun et al., Citation2015; Rank et al., Citation2007). Based on this, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1b: Professional autonomy has a positive relationship with workplace proactivity.

Besides workplace flexibility and professional autonomy, also access to information and knowledge via ICT are ingredients for structural empowerment (Bowen & Lawler, Citation1992; Spreitzer, Citation1996, Citation2008) as these can support workers to perform better. The increased evolution of connectivity technologies, both with respect to hardware and software systems, has provided significant potential for flexible working possibilities (Wynarczyk, Citation2005). Organizations can use social ICT and online knowledge management platforms to enhance virtual collaboration across organizational or team boundaries. Collecting and sharing knowledge and information next to being active in social networks suits the preferences and skills of knowledge workers (Liu & DeFrank, Citation2013). In addition, access to digital information and support from digital technology is important to generate and implement creative and innovative ideas in the workplace (Oldham & Da Silva, Citation2015). Therefore, ICT access to enhance knowledge sharing might enhance self-directed action, something which is central in order to engage in proactive behaviour. Based on the account above, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1c: Access to knowledge via ICT has a positive relationship with workplace proactivity.

The direct relationship between empowering leadership and workplace proactivity

Empowering leadership can be defined as a leadership behaviour through which leaders delegate authority to their employees in order to promote autonomous and self-directed decision making. It involves sharing power with employees, encouraging self-management and supporting employees by giving them space and confidence to handle challenging work without direct interference (e.g. Ahearne et al., Citation2005; Sharma & Kirkman, Citation2015). With regard to workplace proactivity, empowering leadership might be important especially when employees have to do their work with a high degree of discretion (Sharma & Kirkman, Citation2015). In contrast to transformational leaders, who inspire followers with a vision or who challenge them intellectually but still retain all the decision-making and leadership authority, empowering leaders actually transfer much control and power to subordinates (Kim et al., Citation2018). Empowering leadership encourages employees to take responsibility, to face difficulties and to collaborate with others (Arnold et al., Citation2000). In this regard, empowering leadership encourages employees’ initiative and independent workplace behaviour. Empowering leadership can result in employees making their own decisions rather than simply being influenced by their leaders (Ahearne et al., Citation2005). As employees’ workplace proactivity refers to their anticipatory activities in taking the initiative and being in charge of changes with the aim to have an impact on their own work context, we might expect that empowering leaders are responsive to and able to reinforce proactive employees. Previous studies have shown that empowering leadership has the potential to enhance proactive work behaviour (Chen et al., Citation2019; Martin et al., Citation2013). Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2: Empowering leadership has a positive relationship with workplace proactivity.

The mediating role of psychological empowerment

Psychological empowerment addresses employees’ intrinsic task motivation, manifested in four cognitions (i.e. meaning, self-determination, competence and impact), reflecting how employees experience their work (Thomas & Velthouse, Citation1990). The cognition of ‘meaning’ refers to employees’ feelings of sense and enjoyment in their work, and ‘impact’ occurs when employees believe they can affect outcomes in their work. The cognition of ‘competence’ is the capability of accomplishing task goals; ‘self-determination’ is defined as the situation in which employees have the freedom to choose how they do their work. Hence, when employees experience all four psychological states, higher levels of intrinsic task motivation can be achieved, and thus greater psychological empowerment emerges (Spreitzer, Citation1995). To conclude, psychological empowerment is not an organizational intervention or a dispositional trait but rather a cognitive state achieved when individuals perceive that they are empowered. Those feelings of psychological empowerment may be affected by the organizational context, in particular by empowering HRM practices and leadership (Seibert et al., Citation2011).

Workplace flexibility assumes that employees have a say where (place), when (time) and for how long they work (Hill et al., Citation2008). Building on self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000), Carless (Citation2003) reported that time-spatial flexibility appeals to the need satisfaction of autonomy and competence, both of which are important for employees’ autonomous motivation. Moreover, when it comes to psychological empowerment, the basic psychological need for autonomy and competence is closely related to the social cognitions of self-determination and feeling competent (Gagné & Vansteenkiste, Citation2013). Consequently, employees might make themselves more available, which means that they can be consulted readily. This gives employees the feeling that their work is meaningful. According to Peters et al. (Citation2016), access to telework can enhance employees’ motivation, commitment and engagement as it is associated with prestige and signals trust in employees. In this vein, workplace flexibility may enhance employees’ status and hence the feeling that they can have an impact. This leads us to assume that time-spatial flexibility fosters employees’ cognition of psychological empowerment (i.e. self-determination, competence, meaning and impact). Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3a: Workplace flexibility has a positive relationship with psychological empowerment.

Besides workplace flexibility, professional autonomy is also important for employees so that they have a say in how to perform their work. In line with the job characteristics theory (Hackman & Oldham, Citation1976), it can be argued that professional autonomy fosters self-determination and meaning (Humphrey et al., Citation2007). In addition, based on the job demands resource model (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007), it can be argued that job autonomy, viewed as a job resource, is positively related to psychological empowerment (Quiñones et al., Citation2013). Moreover, professional autonomy can enhance employees’ feelings of having impact on their work environment since they can make personal choices regarding how to accomplish their tasks. In addition, employees who are given greater autonomy experience more control over their work, which enhances their feeling of being more competent for their work. Based on this, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3b: Professional autonomy has a positive relationship with psychological empowerment.

As discussed previously, having access to digital information and support via ICT is of major importance for knowledge sharing in organizations. The relationship between access to information and psychological empowerment is already widely acknowledged in both the professional and academic literatures. Spreitzer (Citation1996) found empirical evidence that having access to information is positively associated with perceptions of empowerment. Access to information helps employees to see the bigger picture and thus the impact of their work (Spreitzer, Citation1996). On the basis of social cognition theory (SCT) (Bandura, Citation1986, Citation2002), we assume that individuals pursue a sense of agency and belief that they can have impact on important matters in their work environment. Moreover, SCT suggests that access to information can contribute to self-efficacy (Gist & Mitchell, Citation1992) since this helps to create a sense of meaning and purpose and enhances employees’ ability and competence to make decisions. Led by the above, we assume that access to knowledge facilitates cognitions of empowerment and thus psychological empowerment.

Hypothesis 3c: Access to knowledge via ICT has a positive relationship with psychological empowerment.

Empowerment leadership represents leadership behaviour that may increase employees’ perception of psychological empowerment because of the role that leaders play in shaping work experiences (Spreitzer, Citation2008). Empowering leadership, too, has theoretical roots in SCT (Bandura, Citation1986) and emphasizes employees’ self-influence processes rather than hierarchical control by a manager (Houghton, & Yoho, Citation2005). From this perspective, an empowering leader can enhance employees’ cognitive processes to manage their own behaviour and will therefore enhance psychological empowerment. In line with this, it has been argued that empowering leadership involves leadership behaviour that enhances employees’ perceptions of meaningfulness by supplying information and that expresses confidence in high performance, which enhances their participation in decision making and strengthens feelings of self-determination and impact (Ahearne et al., Citation2005). Finally, empowering leaders can provide employees with constructive feedback, an important source of self-efficacy that enhances employees’ feelings of competence (Bandura, Citation1986). Some researchers have already reported empirical evidence for this (e.g. Lee et al., Citation2018; Zhang & Bartol, Citation2010). Led by the above, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 4: Empowering leadership has a positive relationship with psychological empowerment.

Furthermore, psychological empowerment theory posits that employees’ experience of psychological empowerment can be related to several work outcomes, as empowered employees have an active orientation towards work (cf. Spreitzer, Citation1995; Thomas & Velthouse, Citation1990). When employees perceive the impact and meaningfulness of their own work role, they might become confident that they can understand problems from various perspectives and influence the organization. This feeling may encourage them to undertake more risks and respond to future possibilities, and thus to display higher levels of proactive work behaviour. In addition, employees who experience self-determination and the capability to accomplish their jobs, who put in a greater amount of effort, and who continue to solve any problems that they may encounter are more likely to be proactive in their work (Parker et al., Citation2006; Spreitzer, Citation1995). The above mentioned four dimensions reflect an active rather than a passive orientation to one’s work role. In other words, empowered individuals do not see their work situation as ‘given’, but rather something that enables them to shape their own actions. Psychologically empowered employees are more confident at work and can strengthen their problem-solving abilities (Spreitzer, Citation1995), resulting in higher degrees of workplace proactivity. Led by this, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 5: Psychological empowerment has a positive relationship with workplace proactivity.

Finally, as empowering HRM practices and empowering leadership on the one hand and psychological empowerment on the other are both expected to directly relate to workplace proactivity, their inter-relatedness suggests that psychological empowerment may also be a mechanism through which HRM practices and empowering leadership impact workplace proactivity. In this regard, SCT (Bandura, Citation1986) can explain how an employee functions in terms of a triadic interplay between the environment, the individual’s cognitive state and his or her behaviour. Employees do not merely undergo the influences of their environments in a passive manner, but they can be seen to actively shape their work environment. In the context of NWW, the social environment includes the HRM practices offered by the organization and the empowering leader, which can influence employees’ cognitive states and contributes to psychological empowerment. This has motivational potential and results in an active rather than a passive approach to work (Spreitzer, Citation1995). For these reasons, we assume that employees who experience to be psychologically empowered will also display proactive workplace behaviour. Empowerment scholars have acknowledged that psychological empowerment serves as a mediating mechanism which enhances the positive effect of structural factors (cf. Maynard et al., Citation2012; Seibert et al., Citation2011). In this regard, we might expect that both empowering HRM practices and leadership may evoke psychological empowerment that will motivate employees to display proactive work behaviour. In line with the above, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 6a-6b-6c: Psychological empowerment mediates the relationships between HRM practices (i.e. workplace flexibility, professional autonomy, access to knowledge via ICT) and workplace proactivity.

Hypothesis 7: Psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between empowering leadership and workplace proactivity.

depicts the hypothesized relationships.

Method

Sample

An online questionnaire was administered to 1111 respondents from four subsidiaries of a large Dutch bank active in the financial sector in the Netherlands. These organizations were early adopters of the concept of self-managing teams and had implemented NWW by offering HRM practices. Of all respondents, 342 (31%) filled out the questionnaire completely without errors. From this cross-sectional sample, 177 respondents reported having completed university education at Bachelor’s (47%) and Master’s (37%) level. Of the total sample, 56% were female and 44% male.

Measures

Workplace proactivity was measured with the validated questionnaire developed by Parker and Collins (Citation2010). This questionnaire consists of four subscales: Taking Charge (3 items), Voice (4 items), Individual Innovation (3 items) and Problem Prevention (3 items). A 5-point Likert scale was used for all items (ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree). We used all four subscales in one construct to measure workplace proactivity, as suggested by Parker and Collins (Citation2010). Sample items included ‘Try to implement solutions to pressing organization problems’ (Taking Charge), ‘Speak up and encourage others in the workplace to get involved with issues that affect you’ (Voice), ‘Generate creative ideas’ (Individual Innovation) and ‘Try to develop procedures and systems that are effective in the long term, even if they slow things down to begin with’ (Problem Prevention).

Empowering leadership was measured with the validated questionnaire developed by Arnold et al. (Citation2000). This questionnaire consists of five subscales which include Leading by Example (5 items), Participative Decision Making (5 items), Coaching (6 items), Informing (4 items) and Showing Concern/Interacting with the Team (6 items). A 5-point Likert scale was used for all items (ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Always). As suggested by Arnold et al. (Citation2000), we used all five subscales in one construct. Sample items included ‘Sets a good example by the way he/she behaves’ (Leading by Example), ‘Encourages to express ideas/suggestions’ (Participative Decision-Making), ‘Encourages to solve problems together’ (Coaching) and ‘Explains the purpose of the company’s policies’ (Informing).

Psychological empowerment was measured with the validated questionnaire proposed by Spreitzer (Citation1995). This questionnaire consists of four subscales that include Meaning (3 items), Self-Determination (3 items), Competence (3 items) and Impact (3 items). A 7-point Likert scale was used for all items (ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 7 = Completely agree). As suggested by Spreitzer (Citation1995), we used all four subscales in one construct. Sample items included ‘The work I do is meaningful for me’ (Meaning), ‘I have considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do my job’ (Self-Determination), ‘I am confident about my ability to do my job’ (Competence) and ‘I have significant influence over what happens in my department’ (Impact).

Professional Autonomy (8 items), Workplace Flexibility (3 items) and Access to Knowledge via ICT (6 items) as empowering HRM practices were based on the available literature on NWW (cf. Baane et al., Citation2011; Bijl, Citation2009; Coun et al., Citation2015; Peters et al., Citation2014). A 5-point Likert scale was used for all items (ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree). Sample items included ‘Decide how to do your work’ (Professional Autonomy), ‘Work from home or from the office at your discretion’ and ‘Finish work on weekends or evenings’ (Workplace Flexibility) and ‘Have access to all the information needed for my work outside the office’ (Access to Knowledge via ICT).

Procedure

As the nature of our research was explanatory, we conducted PLS–SEM using SmartPLS version 3.2.3 (Ringle et al., Citation2015). Our purpose was to estimate the predicting power of the hypothesized model. For the partial least square algorithm, we used the path weighting scheme with the maximum number of iterations set at 300 and 10^–5 as our stop criterion. We used a uniform value of 1 as the initial value for each of the outer weights (Henseler, Citation2010). In view of the rule of thumb provided by Barclay et al. (Citation1995), suggesting the use of 10 times the maximum number of paths aiming at any construct in the outer and inner models, the sample size was considered acceptable.

Results

Model characteristics

For the outer model evaluation, we first examined reliability and convergent validity. We checked for convergent validity using Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) criterion of an average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct above the 0.5 benchmark. We checked for reliability using Nunnally’s (Citation1978) Cronbach’s Alfa threshold of 0.7.

Workplace Flexibility and Professional Autonomy were found to have enough validity and reliability to meet the required benchmarks. After two items had been removed, access to Knowledge via ICT was also found to have enough convergent validity and reliability. Empowering Leadership was shown to meet the required benchmarks after the removal of four items. For Psychological Empowerment, we removed three items to ensure sufficient convergent validity and reliability. Finally, we removed five items from Workplace Proactivity for sufficient convergent validity and reliability. For all the constructs, items of all the related sub-constructs were represented as mentioned above (cf. Arnold et al., Citation2000; Parker & Collins, Citation2010; Spreitzer, Citation1995). provides an overview of all constructs and their reliability and convergent validity characteristics.

Table 1. Overview descriptive, reliability and convergent validity scores.

Finally, we checked for discriminant validity, comparing the AVEs of the constructs with the inter-construct correlations determining whether each latent variable shared greater variance with its own measurement variables or with other constructs (Chin, Citation1998; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). We compared the square root of the AVE for each construct with the correlations with all other constructs in the model (). A correlation between constructs exceeding the square roots of their AVEs indicates that they may not be sufficiently discriminable (). For each construct, we found that the absolute correlations did not exceed the square roots of the AVEs. Hence, we may conclude that all constructs showed sufficient reliability and validity.

Table 2. Correlations.

Common-method variance

As we conducted our research using a self-administered survey method, we tested for common-method variance (CMV) to evidence the absence of systematic bias that might have influenced the collected data (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). We used a two-step approach. First, following Podsakoff and Organ (Citation1986), we used Harman’s (Citation1976) one-factor test. In line with this approach, all principal constructs were entered into one principal component factor analysis. Using SPSS software (SPSS version 26 for Windows), we applied the extraction method of principal component of one fixed factor with no rotation method. Results showed that with only one factor emerging, less than 50% of the variance (25.01%) was explained, which gives a first indication of the absence of common-method variance. Second, we used the method proposed by Bagozzi et al. (Citation1991), which stresses that CMV occurs when the highest correlation between constructs is more than 0.9. As shown in , the highest correlation between constructs is 0.7 (correlation between Professional Autonomy and Psychological Empowerment). Therefore, we concluded that no CMV was found in the collected data.

Table 3. Structural relationships with path coefficients (γ) and predicting power f2 .

Model estimations

Regarding the inner model evaluation and estimates, we analysed the path coefficients by using bootstrap t-statistics for their significance (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). For this bootstrapping, we used 5000 subsamples, with a bias-corrected bootstrap, testing for a two-tailed significance of 95%. The model showed a good model fit: the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was 0.07, which is in line with Hu and Bentler’s (Citation1998) criterion of a value lower than 0.08. To test the hypotheses, we first calculated the direct effects for the differentiated paths in the model (see ). Second, we tested the predictive power using Cohen’s (Citation1988) f2effect size to indicate whether each construct had a weak, average or strong effect on ‘Psychological Empowerment’ and ‘Workplace Proactivity’. Finally, to test the mediating role of Psychological Empowerment, we tested the indirect effects of the independent variables via Psychological Empowerment on Workplace Proactivity.

Hypothesis testing

As depicted in , Hypothesis 1a was not supported by the data as Workplace Flexibility had no significant direct effect on Workplace Proactivity (γ = 0.09, p = .256, R2 = 0.28). Hypothesis 1b was also not supported by our data. Whereas a positive direct effect was expected, Job Autonomy was found to have a negative direct significant effect on Work Proactivity (γ = −.19, p = 0.031, R2 = 0.28). However, the predictive power was low (f2 = 0.02). Hypothesis 1c was also not supported by the data. Access to knowledge via ICT had no significant direct effect on Workplace Proactivity (γ = −.08, p = .196, R2 = 0.28). Hypothesis 2 was not supported as Empowering Leadership had no significant direct effect on Work Proactivity (γ = −.01, p = .845, R2 = 0.28). Hypothesis 3a, however, was supported as Workplace Flexibility had a significant relationship with Psychological Empowerment (γ = −.11, p < .050, R2 = 0.55), albeit with a low predictive power (f2 = 0.01). Hypothesis 3b was supported as Professional Autonomy had a significant effect on Psychological Empowerment (γ = .71, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.55) with strong predictive power (f2 = 0.53). Hypothesis 3c was also supported as Access to Knowledge via ICT had a significant relationship with Psychological Empowerment (γ = .13, p = .035, f2= 0.55), albeit with a low predictive power (f2 = 0.02.). Hypothesis 4 was supported as Empowering Leadership had a significant effect on Psychological Empowerment (γ = .11, p = 0.008, R2 = 0.55) with low predictive power (f2 = 0.02). Hypothesis 5 was supported as Psychological Empowerment had a significant effect on Workplace Proactivity (γ = .65, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.28) with strong predictive power (f2 = 0.26). After calculating the indirect effects, we found no support for Hypothesis 6a (γ = −0.07, p = 0.054, R2= 0.29). We did find support for Hypothesis 6b (γ = 0.46, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.29), for Hypothesis 6c (γ = 0.08, p = 0.048, R2 = 0.29) and for Hypothesis 7 (γ = 0.07, p = 0.011, R2 = 0.29).

We also tested for possible moderations of Empowering Leadership on the relationship between HRM practices (i.e. Workplace Flexibility, Professional Autonomy and Access to Knowledge via ICT) and Workplace Proactivity. As depicted in , all interactions were found to be non-significant, which supports that Empowering Leadership and HRM practices (Workplace Flexibility, Professional Autonomy and Access to Knowledge via ICT) do not interact to affect Workplace Proactivity. Furthermore, we tested for possible moderations of Empowering Leadership on the relationship between HRM practices and Psychological Empowerment. Here, too, none of the interactions proved to be significant (see ).

Table 4. Interactions HRM practices and empowering leadership and the relation with workplace proactivity.

Table 5. Interactions HRM practices and empowering leadership and the relation with psychological empowerment.

Discussion and theoretical contributions

The aim of the present study was to investigate simultaneously to what extent HRM practices (i.e. workplace flexibility, professional autonomy and access to information via ICT) and empowering leadership contribute to workplace proactivity in NWW context. Employees’ proactivity has become important since decentralization and digitalization have forced organizations to set up self-organizing teams. The transition from direct control to the delegation of responsibilities requires more empowered and self-controlled employees. We applied an empowerment process approach (cf. Conger & Kanungo, Citation1988; Fernandez & Moldogaziev, Citation2013; Spreitzer, Citation1995) to determine to what extent structural empowerment factors such as empowering HRM practices and empowering leadership have the potential to autonomously motivate employees to display workplace proactivity and what the mediating role of psychological empowerment is. The results of our study revealed a significant mediating role of psychological empowerment in the relationship between HRM practices particularly for professional autonomy, access to knowledge and empowering leadership on the one hand and proactive workplace behaviour on the other hand. In order to focus on the motivating elements in our model, we shall discuss our main findings and contributions below.

First, we found that the relationship between professional autonomy as an empowering HRM practice and workplace proactivity was partially mediated by psychological empowerment. When professional autonomy ensures that employees make positive assessments of the four aspects of their work role (i.e. impact, competence, meaning and self-determination), they achieve higher levels of autonomous motivation, feel more psychologically empowered, and therefore display higher levels of workplace proactivity. This finding gives empirical evidence for Spreitzer’s idea (1995, 2008) that when professional autonomy appeals to an individual’s sense of psychological empowerment, this results in a more active rather than a more passive approach to work. However, and in contrast to insights from the proactivity literature (Parker et al., Citation2006), professional autonomy as an empowering HRM practice can have a negative effect on workplace proactivity when this does not lead to psychological empowerment. Probably, professional autonomy may hinder workplace proactivity when employees experience a lack of direction. The goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, Citation2006) points out that high levels of professional autonomy allow employees to achieve their goals more easily and to select more options. However, professional autonomy can also lead to employees setting unachievable goals or choosing non-appropriate goals. Consequently, professional autonomy combined with increased accountability might cause strain or pressure, make employees less decisive, and therefore might hold them back rather than make them more proactive. Indeed, scholars reported that too much professional autonomy is detrimental to employees’ mental health, as this is likely to create pressure (Kubicek et al., Citation2017; Peters et al., Citation2014; Stiglbauer & Kovacs, Citation2018).

Second, the relationship between access to digital information supported by ICT and workplace proactivity was shown to be fully mediated by psychological empowerment. Obviously, Access to knowledge via ICT has empowering potential as it can play an important role for employees to feel in control and self-determinant, improving employees’ individual capabilities and skills and giving them confidence in terms of having an impact on the organization and having meaningful work. This can intrinsically motivate employees, which in turn can foster workplace proactivity. This is in line with previous research reported by Spreitzer (Citation1996), who found in a study of middle managers that the role of access to information is an important antecedent for psychological empowerment. However, the absence of a direct effect of access to knowledge via ICT on workplace proactivity implies that this HRM practice is not sufficiently effective in terms of enhancing workplace proactivity when employees do not feel empowered.

Third, and contrary to our expectations, workplace flexibility was also not found to be a significant HRM practice that contributes to psychological empowerment in terms of fostering workplace proactivity. Probably, employees in contemporary organizations perceive workplace flexibility as a general condition, necessary to combine work and family, for example, but insufficient for motivating workplace proactivity. However, this HRM practice was not found to hinder workplace proactivity either. This is in line with findings reported by scholars who argue that providing employees with the opportunity to decide when, where and how long they work has increasingly become a right that is built into the employee-employer psychological contract rather than a motivating working condition (Cañibano, Citation2019; Root & Young, Citation2011). In this regard, workplace flexibility might be considered a ‘hygiene factor’ (Herzberg et al., Citation1959), the absence of which leads to ‘dissatisfaction’ whilst the appearance of this condition is not a motivator for employees.

Fourth, above and beyond professional autonomy and access to knowledge via ICT, we found that an empowering leadership style of a manager, only when employees experience to be psychologically empowered, can encourage employees to take initiatives and become more proactive in the workplace. There is no autonomous effect of empowering leadership on workplace proactivity besides this mediation effect. Frese and Fay (Citation2001) pointed out that supervisors may not always foster proactivity, particularly when changes in procedures and routines are perceived as strenuous or threatening. In this regard, the results indicate that sharing power with employees by offering them responsibility and decision-making authority, such as giving support to handle the additional responsibility, enhances employees’ sense of psychological empowerment (Kim et al., Citation2018; Raub & Robert, Citation2010). The finding that empowering leadership only has an indirect effect stresses that leaders need to truly inspire and intrinsically motivate employees. Hence, feeling supported by an empowering supervisor can indeed motivate employees, which in turn can foster their workplace proactivity.

Finally, our additional analyses on the interactions between each single HRM practice (i.e. workplace flexibility, professional autonomy and access to information via ICT) and empowering leadership was not found to be significantly related with psychological empowerment, nor with workplace proactivity. Hence, HRM practices and empowering leadership are complementary (Leroy et al., Citation2018): they combine different perspectives for employees.

Our research has made a number of significant theoretical contributions. First, by simultaneously investigating how HRM practices and leadership foster workplace proactivity, we have contributed to the ongoing debate about the integration of the studies of HRM and leadership to enhance our understanding of how HRM and leadership enhance the empowerment of employees in displaying workplace proactivity (Leroy et al., Citation2018). As such, the leader and the HRM systems and processes are two starting points for influencing people’s behaviour, but they can be related in different ways. They can substitute, reinforce, complement each other, can be used in different ways and in different sequences. Particularly, our study found that HRM and leadership can both contribute to employees’ workplace proactivity via psychological empowerment, which can be linked with one of the mechanisms distinguished by Leroy et al. (Citation2018). The results of our study are in line with the HRM literature that suggests that consistency of signals that are sent from both HRM systems and processes and leadership behaviour, are important for employees’ reactions and attitudes (cf., Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004). In our study, we have found that HRM and leadership are complementary although some prior research with different variables and outcomes in different context found that HRM systems and processes can substitute leadership behaviour (e.g. Audenaert et al., Citation2017) or leadership can compensate for HRM (e.g. Ehrnrooth et al., Citation2020), or either can strengthen each other (e.g. Audenaert et al., Citation2017; Ehrnrooth et al., Citation2020). The results of our study might indicate that HRM and leadership can offer guidance for employees’ behaviour in organizations which can be viewed in light of Mintzberg (Citation1979) who suggested that when power is decentralized and decision making is shared in organizations, formal policies and rules are necessary to clarify and to set shared goals and to provide guidance. Accordingly, formalization through empowering HRM practices (i.e. job design, homework-policy and knowledge management) associated with NWW and decentralization through empowering leadership can have both a positive effect on employees’ psychological empowerment and hence workplace proactivity. In addition, our study has also extended previous research which was mainly focused either on the HRM system or on HR practices (e.g. Arefin et al., Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2019), or on the role of empowering leadership (e.g. Martin et al., Citation2013; Schilpzand et al., Citation2018) in relation to employees’ workplace proactivity.

Second, by drawing on the empowerment process approach (Conger & Kanungo, Citation1988; Fernandez & Moldogaziev, Citation2013; Spreitzer, Citation2008), this study provides additional insights into how HRM practices (i.e. workplace flexibility, professional autonomy and access to knowledge) combined with empowering leadership are necessary, but not sufficient, for fostering employees’ workplace proactivity. The process of psychological empowerment of employees is needed and mediates the relationship between the structural features of managerial empowerment elements and proactivity. Particularly by investigating single HRM practices combined with empowering leadership, we have disentangled the structural facets which actually drive the associations. In this regard, we have extended empowerment research that most commonly investigated only HR practices (cf. Arefin et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2019; Maynard et al., Citation2012) rather than their individual components and the role of leadership (cf. Fong & Snape, Citation2015). In addition, by using an empowerment process approach, we have explained that empowerment can be regarded as an interactional process in which psychological empowerment is shaped through structural factors such as empowering HRM practices and empowering leadership, and we have explained how this produces behavioural outcomes such as workplace proactivity. This contributes to the empowerment theory (Spreitzer, Citation1996) through the acknowledgement that the meaning of empowerment differs from employee to employee, as this is a result of the different interpretations which individuals form regarding the practices, policies and forms of leadership within their work context and how this eventually affects their own psychological state. The empowerment process can be seen as a sense-making process among employees through their own views of HR practices (Nishii & Wright, Citation2008; Weick, Citation1995)

Finally, our study has extended workplace proactivity literature (Parker et al., Citation2010) by focusing on how in contemporary organizations, HRM practices (i.e. professional autonomy and access to knowledge via ICT) and empowering leadership can only indirectly influence employees’ workplace proactivity, that is, when empowering practices and leadership foster psychological empowerment. Although typical HRM practices (i.e. selective staffing, training and rewards) and HR systems have been widely examined in the body of literature on workplace proactivity (Arefin et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2019), to our knowledge the investigation of empowering HRM practices that intrinsically motivate employees to develop proactive workplace behaviour has been limited, and studies have not offered a theoretical framework to understand how this proactivity emerges.

Limitations and directions for future research

Besides a number of limitations, this study has found a number of new directions for further research.

First, because we used a cross-sectional design, the dynamic interplay between empowering HRM practices, empowering leadership, psychological empowerment and workplace proactivity could not be studied, which precluded the determination of causal relationships. In addition, although the empowerment process theory assumes a process, this sequence could not be tested based on the cross-sectional design. Conclusions on causal effects should, therefore, be treated with much caution and reservations, due to the shortcoming of measuring one time. Research approaches such as longitudinal studies are needed to draw firm conclusions about causal relationships. In line with this longitudinal approach, as modern work is changing so rapidly, it would be worthwhile to examine how employees react to organizational changes driven by digitalization and artificial intelligence. Future studies should analyse the positive and negative implications of the consequences of remote working, oftentimes enforced in times of the Covid19-pandemic, and how they evolve over time. How do attitudes of employees towards work change at different implementation stages?

Second, this study focused on the impact of HRM practices (workplace flexibility, job autonomy and ICT access) on proactivity. However, proactive employees might have more opportunities and abilities for job crafting and for negotiating their own (flexible) working arrangements. Proactive individuals could also be more able and motivated to adjust and craft their work tasks (cf. Bakker, Tims, & Derks, Citation2012; Clegg & Spencer, Citation2007). Future research could investigate the dynamic relationship between proactive personality, the crafting of working arrangements and proactive work behaviour. Investigating the possibility of reverse causality might also be interesting to uncover the dynamics of empowerment in the work context. For instance, proactive behaviour may lead to greater structural empowerment, which in turn can contribute to greater psychological empowerment.

Third, as familiarity with remote working has increased over the years and the Covid-19 crisis has also promoted the acceptance of HRM practices related to NWW by managers and employees, one can expect that the outcomes of our study become important for many other workers than highly educated knowledge workers. However, it would be worthwhile to explore the dynamics that develop when employees are obliged or forced to work remotely almost full-time due to the Covid-19 crisis. In addition, as empowerment is about the distribution of power in organizations, authority, autonomy and responsibility have to be delegated to employee levels. However, people do not necessarily give up their control and power easily (Maynard et al., Citation2012). Future research could further explore how organizations that have embraced NWW and teleworking during the Covid-19 crisis will continue these practices.

Finally, in an attempt to connect the leadership and HRM literature, our study has investigated simultaneously how both leadership and HRM practices contribute to workplace proactivity. Led by the results of our study, we found that in the context of NWW, HRM and leadership can be regarded as complementary as they combine different perspectives for employees. Whilst some studies (e.g. Audenaert et al., Citation2017; Ehrnrooth et al., Citation2020) found interaction effects between HRM and leadership, others (Jo et al., Citation2020) could not find synergetic interaction effects between HRM and leadership. We encourage future research to shed more light on the boundary conditions and the mechanisms that influence how HRM systems and processes and different leadership approaches operate in empowering and, hence, motivating employees to enact proactive behaviour enhancing performance. In addition, by investigating the interactions between additional factors or possible configurations via advanced methods such as qualitative comparative analysis, could be helpful in this regard (Greckhamer et al., Citation2018). Future research should also focus on multiple interrelations between HRM and leadership as proposed by Leroy et al. (Citation2018) that can enhance workplace proactivity via psychological empowerment.

Managerial implications

Our findings have a number of practical implications for HR staff and departments, organizational leaders and employees who need to be more responsive and proactive with respect to the challenges presented by an increasingly agile and dynamic work environment fuelled by new technology, artificial intelligence and digitalization.

First, in order to improve workplace proactivity, it is important for organizations to identify the stimulating and detrimental factors in the contemporary work environments. They should act wisely when adopting HRM programmes that promote workplace flexibility, autonomy and unlimited access to knowledge. Workplace flexibility is an important enabler in modern workplaces but has no motivational potential regarding workplace proactivity. In addition, although employees’ psychological empowerment and proactive workplace behaviour can be enhanced through professional autonomy and access to knowledge via ICT, there are limits to what autonomy can achieve.

Second, employees should feel empowered by both the systems and the processes in an organization as well by the individual leader. Professional autonomy is important, but managing people remotely is not enough. In order to demonstrate autonomous workplace proactivity, employees must be given autonomy, flexibility and access to information (i.e. a feeling of being trusted) to feel empowered. As this empowerment is especially important in virtual settings (Spreitzer, Citation2008), management and HR departments should take this into account as many employees are currently forced to work more remotely and in virtual settings due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Third, team leaders and supervisors have a critical role in promoting psychological empowerment and thus positive workplace proactivity among employees whose work is characterized by a high degree of professional autonomy in the context of NWW. In particular, organizations should encourage their team leaders and supervisors to develop and demonstrate empowering leadership behaviour and to engage in relationships with their employees, so that employees feel that they are supported and also valued. This is pertinent not only for maintaining a healthy and productive work context for employees but also for attracting and retaining talent (Ehnert et al., Citation2014).

Finally, managers should be aware that enhancing empowering elements in the work context may be fruitful as empowered employees have greater authority and responsibility for their work in terms of maintaining meaning in their work and having an impact at work. Our study provides additional insights into the empowerment process concerning factors which can enhance proactivity. Employees’ workplace proactivity is crucial for organizational success, given the increased uncertainty that characterizes the contemporary world of work where change is ever present and where flexibility is continuously needed. To conclude, organizations that aim to increase employees’ workplace proactivity need to invest in HRM practices and forms of leadership that support employees and make them feel psychologically empowered.

Acknowledgement

We thank C.W.I. Jongerius for the help with the data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions e.g. their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

- Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J., & Rapp, A. (2005). To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 945–955. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.945

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

- Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., & Kalleberg, A. L. (2000). Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off. New York, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Arefin, M. S., Arif, I., & Raquib, M. (2015). High-performance work systems and proactive behavior: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. International Journal of Business and Management, 10(3), 132–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v10n3p132

- Arnold, J. A., Arad, S., Rhoades, J. A., & Drasgow, F. (2000). The empowering leadership questionnaire: The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring leader behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(3), 249–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200005)21:3<249::AID-JOB10>3.0.CO;2-#

- Audenaert, M., Vanderstraeten, A., & Buyens, D. (2017). When affective well-being is empowered: The joint role of leader-member exchange and the employment relationship. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(15), 2208–2227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1137610

- Baane, R., Houtkamp, P., & Knotter, M. (2011). The new world of work unravelled. (In Dutch: Het nieuwe werken ontrafeld). Assen: Uitgeverij Van Gorcum.

- Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421–458. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2393203

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Database] https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations, 65(10), 1359–1378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712453471

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. (2002). Growing primacy of human agency in adaptation and change in the electronic era. European Psychologist, 7(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027//1016-9040.7.1.2

- Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Studies, 2, 285–309.

- Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1999). Proactive behavior: Meaning, impact, recommendations. Business Horizons, 42(3), 63–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-6813(99)80023-8

- Batistič, S., Černe, M., Kaše, R., & Zupic, I. (2016). The role of organizational context in fostering employee proactive behavior: The interplay between HR system configurations and relational climates. European Management Journal, 34(5), 579–588. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.01.008

- Bijl, D. (2009). Starting with new ways of working (In Dutch: Aan de slag met Het Nieuwe Werken). Zeewolde: Par CC.

- Bindl, U. K., & Parker, S. K. (2010). Proactive work behaviour: Forward-thinking and change-oriented action in organizations. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 567–598). American Psychological Association.

- Binyamin, G., & Brender-Ilan, Y. (2018). Leaders’ language and employee proactivity: Enhancing psychological meaningfulness and vitality. European Management Journal, 36(4), 463–473. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2017.09.004

- Bowen, D. E., & Lawler, E. E. (1992). The empowerment of service workers: What, why, how and when. Sloan Management Review, 33(3), 31–39.

- Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29, 203–221.

- Cañibano, A. (2019). Workplace flexibility as a paradoxical phenomenon: Exploring employee experiences. Human Relations, 72(2), 444–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718769716

- Carless, S. A. (2003). Does psychological empowerment mediate the relationship between psychological climate and job satisfaction?Journal of Business and Psychology, 18(4),405–425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBU.0000028444.77080.c5

- Chen, G., Smith, T. A., Kirkman, B. L., Zhang, P., Lemoine, G. J., & Farh, J. L. (2019). Multiple team membership and empowerment spill over effects: Can empowerment processes cross team boundaries?Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(3), 321–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000336

- Chen, M., Lyu, Y., Li, Y., Zhou, X., & Li, W. (2017). The impact of high-commitment HR practices on hotel employees’ proactive customer service performance. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 58(1), 94–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965516649053

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295, 295–336.

- Clegg, C., & Spencer, C. (2007). A circular and dynamic model of the process of job design. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(2), 321–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/096317906X113211

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

- Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1988). The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 471–482. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1988.4306983

- Cooper, C. D., & Kurland, N. B. (2002). Telecommuting, professional isolation, and employee development in public and private organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(4), 511–532. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.145

- Coun, M. J. H., Gelderman, C. J., & Pérez Arendsen, J. (2015). Shared leadership and proactivity in new ways of working (In Dutch: Gedeeld leiderschap en proactiviteit in Het Nieuwe Werken) (Vol. 28(8), pp. 356–379). Gedrag & Organisatie.

- Coun, M. J. H., Peters, P., & Blomme, R. J. (2019). Let’s share!’ The mediating role of employees’ self-determination in the relationship between transformational and shared leadership and perceived knowledge sharing among peers. European Management Journal, 37(4), 481–491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.12.001

- Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 435–462. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600304

- Cohen, J & Ryan, R.M. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

- Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R.M. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

- Ehnert, I., Harry, W., & Zink, K. J. (2014). Sustainability and HRM: An introduction to the field. In I. Ehnert, W. Harry, & K. J. Zink (Eds.), Sustainability and human resource management: Developing sustainable business organizations (pp. 3–32). Heidelberg: Springer.

- Ehrnrooth, M., Barner‐Rasmussen, W., Koveshnikov, A., & Törnroos, M. (2020). A new look at the relationships between transformational leadership and employee attitudes—Does a high‐performance work system substitute and/or enhance these relationships?Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22024.

- Fernandez, S., & Moldogaziev, T. (2013). Using employee empowerment to encourage innovative behavior in the public sector. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(1), 155–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mus008

- Fong, K. H., & Snape, E. (2015). Empowering leadership, psychological empowerment and employee outcomes: Testing a multi‐level mediating model. British Journal of Management, 26(1), 126–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12048

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Frese, M., & Fay, D. (2001). Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23, 133–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23005-6

- Gagné, M., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2013). Self-determination theory’s contribution to positive organizational psychology. In A. B. Bakker (Ed.), Advances in positive organizational psychology (pp. 61–82). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Gerdenitsch, C., Kubicek, B., & Korunka, C. (2015). Control in flexible working arrangements. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 14(2), 61–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000121

- Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management Review, 17(2), 183–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1992.4279530

- Greckhamer, T., Furnari, S., Fiss, P. C., & Aguilera, R. V. (2018). Studying configurations with qualitative comparative analysis: Best practices in strategy and organization research. Strategic Organization, 16(4), 482–495. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127018786487

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7

- Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Henseler, J. (2010). On the convergence of the partial least squares path modeling algorithm. Computational Statistics, 25(1), 107–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-009-0164-x

- Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snydermann, B. (1959). The motivation to work. New York: Wiley.

- Hill, E., Grzywacz, J. G., Allen, S., Blanchard, V. L., Matz-Costa, C., Shulkin, S., & Pitt-Catsouphes, M. (2008). Defining and conceptualizing workplace flexibility. Community, Work and Family, 11, 149–163.

- Hill, N. S., & Bartol, K. M. (2016). Empowering leadership and effective collaboration in geographically dispersed teams. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 159–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12108

- Houghton, J. D., & Yoho, S. K. (2005). Toward a contingency model of leadership and psychological empowerment: When should self-leadership be encouraged?Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11, 65–83.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to under parameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

- Humphrey, S. E., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1332–1356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1332

- Jo, H., Aryee, S., Hsiung, H. H., & Guest, D. (2020). Fostering mutual gains: Explaining the influence of high‐performance work systems and leadership on psychological health and service performance. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(2), 198–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12256

- Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2010). Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63(1), 83–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709349199

- Kim, M., Beehr, T. A., & Prewett, M. S. (2018). Employee responses to empowering leadership: A meta-analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25, 257–276.

- Kubicek, B., Paskvan, M., & Bunner, J. (2017). The bright and dark sides of job autonomy. In C. Korunka & B. Kubisec (Eds.), Job demands in a changing world of work: Impact on workers’ health and performance and implications for research and practice (pp. 45–63). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54678-0_4.

- Leach, D. J., Wall, T. D., & Jackson, P. R. (2003). The effect of empowerment on job knowledge: An empirical test involving operators of complex technology. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/096317903321208871

- Lee, A., Willis, S., & Tian, A. W. (2018). Empowering leadership: A meta‐analytic examination of incremental contribution, mediation, and moderation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(3), 306–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2220

- Lee, H. W., Pak, J., Kim, S., & Li, L. Z. (2019). Effects of human resource management systems on employee proactivity and group innovation. Journal of Management, 45(2), 819–846. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316680029

- Leroy, J., Segers, J., Van Dierendonck, D., & Den Hartog, D. (2018). Managing people in organizations: Integrating the study of HRM and leadership. Human Resource Management Review, 28(3), 249–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.02.002

- Liu, Y., & DeFrank, R. S. (2013). Self-interest and knowledge-sharing intentions: The impacts of transformational leadership climate and HR practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(6), 1151–1164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.709186

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 265–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00449.x

- Martin, S. L., Liao, H., & Campbell, E. M. (2013). Directive versus empowering leadership: A field experiment comparing impacts on task proficiency and proactivity. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1372–1395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0113

- Maynard, M. T., Gilson, L. L., & Mathieu, J. E. (2012). Empowerment-fad or fab? A multilevel review of the past two decades of research. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1231–1281. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312438773

- Menon, S. (2001). Employee empowerment: An integrative psychological approach. Applied Psychology, 50(1), 153–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00052

- Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations. Engle-wood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321–1339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321

- Nishii, L. H., & Wright, P. M. (2008). Variability within organizations: Implications for strategic human resources management. In D. B. Smith (Ed.), The people make the place: Dynamic linkages between individuals and organizations (pp. 225–248). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd edition). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Oldham, G. R., & Da Silva, N. (2015). The impact of digital technology on the generation and implementation of creative ideas in the workplace. Computers in Human Behavior, 42, 5–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.041

- Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310363732

- Parker, S. K., & Collins, C. G. (2010). Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. Journal of Management, 36(3), 633–662. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308321554

- Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., & Turner, N. (2006). Modelling the antecedents of proactive behaviour at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 636–652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636

- Parker, S. K., & Wu, C. H. (2014). Leading for proactivity: How leaders cultivate staff who make things happen. In D. Day (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of leadership and organizations (pp 380–403). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Peters, P., Den Dulk, L., & van der Lippe, T. (2009). The effects of workplace flexibility and new working conditions on employees’ work–life balance: The Dutch Case. Community, Work & Family, 12, 279–297.

- Peters, P., Ligthart, P., Bardoel, A., & Poutsma, F. (2016). Fit’ for telework’? Cross-cultural variance and task-control explanations in organizations’ formal telework practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(21), 2582–2603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1232294

- Peters, P., Poutsma, E., Van der Heijden, B. I., Bakker, A. B., & Bruijn, T. D. (2014). Enjoying new ways to work: An HRM-process approach to study flow. Human Resource Management, 53(2), 271–290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21588

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

- Quiñones, M., Van den Broeck, A., & De Witte, H. (2013). Do job resources affect work engagement via psychological empowerment? A mediation analysis. Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones, 29(3), 127–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5093/tr2013a18

- Rank, J., Carsten, J. M., Unger, J. M., & Spector, P. E. (2007). Proactive customer service performance: Relationships with individual, task, and leadership variables. Human Performance, 20, 363–390.

- Raub, S., & Robert, C. (2010). Differential effects of empowering leadership on in-role and extra-role employee behaviors: Exploring the role of psychological empowerment and power values. Human Relations, 63(11), 1743–1770. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710365092

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt. Retrieved November 6, 2018 from http://www.smartpls.com.

- Root, L. S., & Young, A. A., Jr. (2011). Workplace flexibility and worker agency: Finding short-term flexibility within a highly structured workplace. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 638(1), 86–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716211415787

- Sardeshmukh, S. R., Sharma, D., & Golden, T. D. (2012). Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: A job demands and job resources model. New Technology, Work and Employment, 27(3), 193–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00284.x

- Schilpzand, P., Houston, L., & Cho, J. (2018). Not too tired to be proactive: Daily empowering leadership spurs next-morning employee proactivity as moderated by nightly sleep quality. Academy of Management Journal, 61(6), 2367–2387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0936

- Seibert, S. E., Wang, G., & Courtright, S. H. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 981–1003. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022676

- Sharma, P. N., & Kirkman, B. L. (2015). Leveraging leaders: A literature review and future lines of inquiry for empowering leadership research. Group & Organization Management, 40, 193–237.

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 1442–1465.

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1996). Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 483–504.