Abstract

An intra-organizational change process involving all middle managers was studied in a public sector organization in Sweden over three time points, spanning two years in total. Using sensemaking and the person-environmental fit literature as well studies on promotion and demotion, hypotheses about the effects of managerial status loss and being offered a non-preferred role (non-preference) on change reactions (job satisfaction, turnover intentions, mental health) are made. Data from 140 middle managers was analyzed with path models, where two process factors (perceived organizational support during the change, procedural justice of the change) and two job characteristics (job demand, job control) were tested simultaneously as mediators. Results revealed that managerial status loss had negative effects on work attitudes but mental health was positively affected over time through decreased job demands. Non-preference had negative consequences for all outcome variables and these effects were mediated through lower procedural justice of the change, lower job control, and for some outcomes, lower perceived organizational support during the change. The results provide insight into how middle managers react to change, and suggest that process justice and job characteristics play an important part in shaping these reactions.

Introduction

Leadership is considered one of the key drivers of successful implementation of organizational change (van der Voet, Citation2014). While executive managers often initiate organizational changes, middle managers are the ones to implement them. Middle managers are therefore the de facto enactors of change; they serve as role models, explain the change to their subordinates, and motivate them to commit to the change. The effects of changes on subordinates have been studied extensively (Oreg et al., Citation2011; Worley & Mohrman, Citation2014), and systematic reviews have concluded that organizational restructuring affects subordinates’ well-being mostly negatively, both in the short and in the long run (de Jong et al., Citation2016; Westgaard & Winkel, Citation2011). Yet, managers are not exempt from organizational changes themselves, especially not when organizational changes target managerial structures and positions, which imply the risk that managers lose their status, or are moved to roles they do not prefer. With the specific role of being both subordinate to upper management, as well as manager with leadership responsibilities for subordinates, middle managers’ work attitudes and well-being during and after an organizational change process are of particular relevance for the wider company, the success of the change, and a large number of subordinate employees. Yet, there is surprisingly little research on managers’ change reactions in the specific case when managerial jobs are the main focus of the restructuring efforts of the organization (for an exception, see Davies, Citation2000).

In the present study, we investigate an intra-organizational change process in a public sector organization in Sweden over two years. All middle managers were asked to reapply for positions with re-defined job descriptions, effectively reducing the available number of managerial positions. The aim of the change process was to establish a lean managerial hierarchy with clear responsibilities under a new organizational structure with an increased focus on customer orientation (with the citizen being the customer). This process bears clear resemblance to ideas related to new public management (NPM). The idea of NPM is that state-financed public sector organizations have to be transformed and run much like private companies to be more competitive and cost-effective (Hall, Citation2013). The change process we describe is not unusual; after the financial crisis in the 1990s, the public sector in Sweden has been subject to wide-ranging reforms implementing NPM ideas (Bach & Bordogna, Citation2011; Berg Elisabeth et al., Citation2008).

With this paper, we make the following contributions to the organizational change and NPM literature. First, we study the effects of a specific restructuring process, where managers reapply for revised positions within their current organization. Here, we disentangle the effects of losing the managerial position and getting a non-favored position. While it is a common tactic of organizations to let employees reapply for positions within the organization after a restructuring process, there is very little scientific studies on employee reactions to this practice. Second, this study sheds more light onto potential explanatory mechanisms of reactions to change. We evaluate the mediating potential of two process-related psychological mechanisms (perceived organizational support during change and procedural justice of the change) and two job characteristics (job demands and job control) for managers’ change reactions. Process-related mechanisms have been given research focus in the organizational change literature (Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1999; Bouckenooghe et al., Citation2009), while the role of job characteristics as a mediator mainly been described in the literature on health (Kivimäki et al., Citation2000), and the present study is one of the first to combine these perspectives. Moreover, several mediators are rarely tested simultaneously (for exceptions, see Kivimäki et al., Citation2001; van den Heuvel et al., Citation2015), but in the present study we include four, which better reflects the reality that several processes may occur at once. Our third contribution is the investigation of changes in managers’ work attitudes and mental health two months after a reorganization (which included the possibility of managerial status loss or getting a non-preferred job), thus capturing immediate reactions to the change process

Intra-organizational job changes and its consequences

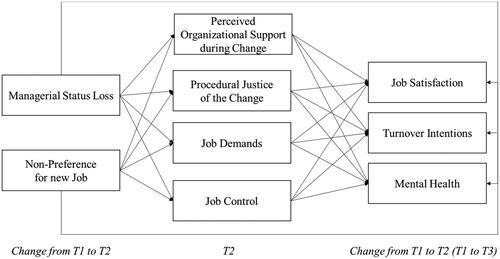

In a situation where managers have to apply for re-defined positions within their organization, two risks can arise; the risk of losing the managerial position (managerial status loss) and the risk of being moved into a non-favored position (non-preference). Managerial status loss refers to when managers no longer hold the status of being managers after the restructuring process. Non-preference refers to whether managers are moved to a less preferred positions instead of attaining the job they applied for as their first choice. We expect these changes to relate to a number of different outcomes, which are outlined in our theoretical model ().

No longer being in a managerial position after restructuring while staying in the same organization is likely seen as a demotion and status loss by former managers themselves, as well as by others in the organization. Higher social status is related to higher levels of job satisfaction (Feng et al., Citation2017), and lower turnover intentions (Knapp et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, higher socioeconomic status is related to better health and well-being (Knight & Mehta, Citation2017). Studies on demotions of employees have reported negative consequences, such as higher levels of exhaustion, dissatisfaction with work, lower identification with work (Hennekam & Ananthram, Citation2020).

In contrast, managers who are offered a new managerial position after a management restructure will likely see the maintenance of their status as a manager as confirmation of their abilities, skills, and competence as manager. Being re-hired for a similar or perhaps even more challenging managerial position may resemble intra-organizational promotion decisions. Studies on promotion decisions have shown that recently promoted employees have higher levels of job satisfaction, lower turnover intentions, and higher commitment than those who were unsuccessful in receiving a promotion (Lam & Schaubroeck, Citation2000). In another study, intra-organizational upward career transitions were found to increase career satisfaction (Rigotti et al., Citation2014).

In the context of organizational restructuring, and building on the person-environment-fit literature (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005), it can be expected that managers likely apply for positions that they feel best equipped for, that is, which most closely matches their skills and interests. Not being hired for the preferred position is likely seen as a negative outcome. Managers can decide to leave the organization or, if offered, accept an alternative position, either as manager or not, but not for the specific team or area they preferred. In both cases, managers, when accepting such an alternative offer, have to compromise on what they may see as their potentially best person-environmental fit.

The job applicant, regardless of whether the manager still wanted to hold a managerial role after the restructuring, or preferred to step down as manager, likely interprets getting the preferred position as a positive outcome. As the restructuring gives a unique chance to move into a position that truly fits, receiving the job one prefers should be positively related to work attitudes and mental health. Evidence supports positive associations between fit and job satisfaction (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005), turnover intentions (Abdalla et al., Citation2018), and mental health (Tong et al., Citation2015). In sum, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1: Managerial status loss is associated with decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and decreased mental health.

Hypothesis 2: Non-preference is associated with decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and decreased mental health.

The mediating role of process factors

Organizational change processes are believed to result in individual change reactions via psychological mechanisms (Datta et al., Citation2010), such as employees’ perceptions of the organizational change process (Chen & Wang, Citation2014; Cullen et al., Citation2014; Marzucco et al., Citation2014; Thakur & Srivastava, Citation2018). In the organizational change literature, such process factors pertaining to employees’ perceptions of different aspects of the organizational change process (Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1999; Bouckenooghe et al., Citation2009) refer to individual’s perceptions of actions undertaken during the implementation of the organizational change process. In this paper, we focus on the role of perceived organizational support during the change process, and perceived procedural justice of the change process. If managers experience a managerial status loss, or are not hired for the job they preferred, they will seek explanations for these unfavorable outcomes that do not negatively impact their self-evaluations of own managerial skills and competence or personal attributes. Based on sensemaking theory (Weick, Citation2001) and findings on attributions of promotion decisions (Webster & Beehr, Citation2013), we argue that managers who face unfavorable intra-organizational job changes attribute this to how the organization handled the change process, rather than their own shortcomings. Sensemaking is a retrospective process, in which people attempt to find rational justifications that give meaning to what they have encountered (Weick, Citation2001). Importantly, retrospective sensemaking means that biased reconstructions can occur, since the outcome is known at the time when the reconstruction takes place (Weick, Citation2001). It has been found that individuals who are not promoted blame something other than themselves for this unfavorable result (Webster & Beehr, Citation2013). This may disclose a self-serving bias, that is, a person tends to attribute success to own abilities and failures to circumstances in situations when the self is threatened (Campbell & Sedikides, Citation1999), where the individual strives to maintain a positive self-presentation and self-esteem (Shepperd, Malone, & Sweeny, Citation2008). Mapped onto the situation of losing one’s status as manager or being hired for something else than the preferred job, managers may retrospectively attribute the undesired outcome to a lack of justice in the recruitment process, or a lack of support from the organization. In contrast, candidates hired for their preferred jobs or in new managerial positions, are more likely to express positive evaluations of the organization’s support and procedural justice, since the strategies have brought their own competence and personal fit for the job to the fore.

There is evidence that perceptions of organizational support and procedural justice of the change management relate to subsequent employee reactions. For example, employees who perceive low procedural justice during the organizational change are less likely to identify with the organization (Michel et al., Citation2010), less likely to accept, support, and commit to the change (Korsgaard et al., Citation2002), and report lower well-being (de Jong et al., Citation2016) than those who perceive high procedural justice. Similarly, not perceiving the organization as supportive was found to relate to less favorable employee reactions in change contexts (Chen & Wang, Citation2014; Cullen et al., Citation2014; Lawrence & Callan, Citation2011; Thakur & Srivastava, Citation2018). Based on the above, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3: The evaluation of the change process mediates the relationship between managerial status loss and change reactions. Specifically, managerial status loss is negatively associated with the evaluation of the change process (perceived organizational support during change, perceived procedural justice of the change), which, in turn, is associated with decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and decreased mental health.

Hypothesis 4: The evaluation of the change process mediates the relationship between non-preference and change reactions. More specifically, non-preference is negatively associated with the evaluation of the change process (perceived organizational support during change, and procedural justice of the change), which, in turn, is associated with decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and decreased mental health.

The mediating role of job characteristics

Another potential mechanism underlying the relationship of the restructuring to work attitudes and mental health may be related to job characteristics. Theories on work stressors and resources propose that job characteristics are fundamental in shaping work attitudes and health (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). The most well-known theory of job characteristics is the Job-Demand-Control model (Karasek & Theorell, Citation1990), which proposes that job demands have a negative effect, and job control a positive effect on work attitudes and health outcomes. Job demands are often understood in terms of the quantitative workload, and job control in terms of autonomy in influencing aspects of one’s work activities. An organizational change typically involves mastering new or different tasks, a higher workload, or ambiguous tasks. Changes in the public sector often have often meant that employees have to do more work with fewer resources than before (Kiefer et al., Citation2015). Navigating the workload through an organizational change process, which tends to be characterized by a high degree of uncertainty, puts additional demands on people (Datta et al., Citation2010; de Jong et al., Citation2016). Empirical evidence shows that a reduction in staff numbers or restructuring of work hours can increase perceptions of job demands and job stress and make it even more important to have autonomy in how to deal with these changes (Boyd et al., Citation2014). At the same time, job control can be negatively affected by organizational changes, because changed roles may also involve different rules about the delegation of tasks, the decision-making process involved in the daily work, or changes to how or when the tasks need to be done. Structural changes within an organization have been found to relate to increased role ambiguity, increased workload, and lower perceived control (Chauvin et al., Citation2014; Day et al., Citation2017). Only a few studies have focused on the mediating role of job characteristics for the relationship between organizational changes and stress and health outcomes (Bond & Bunce, Citation2001; Kivimäki et al., Citation2000; Kivimäki et al., Citation2001; Tvedt, Saksvik, & Nytrø, Citation2009), and the present study provides an important contribution in examining this relationship.

After the restructuring process, those in a managerial position will likely experience an increased workload due to the reduction of managerial positions overall (Kiefer et al., Citation2015; Rigotti et al., Citation2014). At the same time, being in a managerial role may involve a high degree job control as new ways of working will need to be organized within a bigger team, and managers typically are given the authority to decide how work is allocated and done differently within a new organizational structure. In contrast, those who have lost their managerial status will likely have less job control than managers. What regards job demands, those who have lost their managerial position may have to master new tasks, at the same time as they are experiencing a loss in job control and status. No longer being a manger might also be accompanied by a lack of social connection with the new colleagues (probably former subordinates), which could hinder integration into the new team and make it difficult to ask for advice how to master new tasks. In total, this might result in higher perceived job demands and lower job control among non-managers than for those who are still managers.

If being assigned the preferred position, individuals may perceive a good person-environment fit, and may view the work demands and control that come with their work role rather favorable, no matter whether they still are managers or not. In contrast, when not getting the preferred position, the person-environment fit may be evaluated more negatively, and with such a perception of mismatch, the employee is more likely to evaluate work demands and job control in their non-preferred role more unfavorably after the change, which, in turn, can be expected to be associated with unfavorable reactions to the change process. In sum, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5: Perceived job characteristics mediate the relationship between managerial status loss and change reactions. Specifically, managerial status loss is associated with higher job demands and lower control, which, in turn, are associated with decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and decreased mental health.

Hypothesis 6: Perceived job characteristics mediate the relationship between non-preference and change reactions. Specifically, non-preference is associated with higher job demands and lower job control, which, in turn, are associated with decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and decreased mental health.

The role of time

An important question is whether individual change reactions are sustained over a longer period of time after a change process has been implemented. The three-stages model by Lewin (Citation1951) proposes that a successful change involves individuals adapting to the new environment and internalize the new structures, behaviors, and norms. In order to identify individuals’ immediate reactions to organizational change processes, it is conventional to design studies that enable researchers to compare levels of employee attitudes and health before the change process to those after the process. Depending on the nature of the organizational change and the reactions in question, the ideal time point to capture such immediate employee reactions may differ. In this study, we focus on short-term effects measured at two months after the implementation, in order to allow some time for all new and former managers to become familiar with the new organizational structure and their new job positions. There has been a debate about whether individual change reactions may be sustained, or decline, over time. For example, it has been argued that individuals adapt, and therefore their reactions may go back to pre-change levels over time (Bamberger et al., Citation2012). Yet others have argued that individual reactions may not manifest immediately, but need time to develop before they are observable, which means that individual reactions may not be measurable immediately after a change process but only after some time has passed (de Jong et al., Citation2016). The ideal time lag for capturing such long-term reactions is therefore not necessarily known and may rely on the judgment of the researcher, or alternatively, on the organization. In our study, we conducted a follow-up after a rather long time span (17 months after implementation) in order to supplement our analyses of the immediate reactions with additional analyses of the reactions over a longer time span.

Methods

Organizational setting

Data were collected in a Swedish government agency that reorganized their management structure in order for the organization to become more effective and service-oriented. As is common in Sweden, the change proposal was discussed with the union before the implementation started. The proposed change resulted in the number of managerial positions decreasing by one third. This was achieved by creating three service areas from the previous four, and by re-allocating tasks and responsibilities so that each area was composed of four to five units with about ten teams each. Team sizes increased when 158 teams were restructured into 123 teams without any involuntary layoffs. Inevitably, this also changed the responsibilities of the new managerial positions. Prior to restructuring, the lowest managerial role in the organizational structure, the team manager, encompassed both operational and managerial tasks, but it now became solely a managerial role. After the restructuring, team managers were expected to only engage in leadership tasks, and to not be involved in any operational tasks. At the next level up in the hierarchy, the unit managers now carried out work that previously was divided into team management, unit management, and process management, effectively gathering tasks that previously had been spread across three managerial levels into one role. At the next level, three new service area manager roles were created. These reported directly to the agency director. Nothing was changed for the agency director and vice director, who were excluded from this study. Other managers from the head office were included, since potentially these managers could also apply for a new role, and because two new managerial functions were added at head office. These managerial functions provided specific expertise and support across hierarchies and service areas.

The change process: Job reallocation

All middle managers were invited to apply for the newly created managerial positions. Alternatively, they could decide to step down as managers (by not applying for one of the new positions). All newly created managerial positions were advertised internally and externally. All applicants had to fulfill certain educational requirements, and were tested (through psychometric testing) by an external recruitment consultant. Upon recommendation by this consultant, potential candidates were interviewed. The recruitment for the new managerial positions was organized in a top-down order following several steps. First, positions at the top of the hierarchy (the service area managers) were filled. Recruitment decisions for this highest managerial level (service area manager) were made by the agency director together with head office and human resource management personnel. The service area managers then participated the recruitment and interviewing of candidates for the next level, i.e. their respective unit managers, and these unit managers finally had a say in appointing the team managers after the interview round. One person could apply for several positions (for example, for unit manager and team manager, or for process manager and unit manager), but had to indicate which of these positions they preferred. During the time of the recruitment process, the organization worked under the old structure. The recruitment procedure was scheduled to be conducted over a period of six months so that all positions would be filled before the date at which the agency adopted the new organizational structure.

In this new organizational structure, some of the former managers were now working as non-managerial staff, either because the organization had not hired them for a new managerial role (declined their application), or because they had signaled to the organization that they would want to step down from their managerial position. Also, among the new managers, some had been hired for their preferred managerial position, whereas others were not in the managerial position that was their preference (e.g. had accepted a managerial role at a lower level, or for another group). During the whole process, all managers had the option to ask for counseling with an external coach that provided career guidance. No advice was offered by the organization’s own HR division, as they did not want to seem partial towards certain managers.

Data collection

Data were collected by means of online surveys. The target population consisted of those in managerial positions at Time 1 (T1; June 2011). From January 2012 onwards, the new organizational structure was in place, which meant that the former managerial positions did not exist anymore, and all had started the new managerial or non-managerial roles that they had been recruited for. Two follow-up surveys were sent out at Time 2 (T2; March 2012) and Time 3 (T3; June 2013). Before the start of the first data collection, all potential participants received a letter communicating the purpose of the research project, assuring that participation would be voluntary and confidential, and that the study had been approved by the relevant ethics review board. Participants could access the online survey via a link that was sent to their work email. Three reminders were provided before the survey was closed. The first survey (T1) was sent out about eight weeks before each manager had to submit their application for a managerial position in the new organizational structure. The second survey (T2) was sent about eight weeks after the implementation of the new organizational structure. By that time each employee had worked in their new role for about two months. The third survey (T3) was sent about one year and two months after T2. No major organizational changes happened between T2 and T3.

Participants

At T1, a total of N = 178 managers out of 208 eligible employees responded to the survey, which corresponds to a response rate of 86%. At T2, N = 140 participated and at T3 N = 142 individuals responded to the survey. In total, N = 131 responded to T1 and T2 and N = 91 participated at all three measurement points (longitudinal response rate T1-T2-T3: 70%).

Dropout analyses showed that those who participated only at T1 had significantly lower levels of job satisfaction and higher levels of turnover intentions at T1 than those who participated at both T1 and T2. There were no differences in terms of demographic variables or any other study variable. There were no significant differences in terms of demographic variables or any other study variable between those who replied to all three waves (T1, T2, and T3) and those who replied only to T1 and T2 but not T3.

Those who participated in both T1 and T2 were on average 48 years of age (SD = 9), with an average tenure of 18 years (SD = 12), 53% were women, 46% men, and 65% at least a Bachelor’s degree. Participants who responded to all three measurements were on average 48 years old (SD = 8), had an average organizational tenure of 19 years (SD = 11), 54% were women and 66% had at least a Bachelor’s degree.

Measures

Job transitions

At T2, managerial status loss was assessed with one item asking the participants to indicate whether the current job position included a managerial role (in one of four possible categories for team, unit, service area or headquarter) or not. Answers were recoded so that all those who ticked one of the four possible managerial positions were collapsed into 0 (still manager), whereas all others were coded into 1 (no longer manager).

At T2, non-preference was measured with a single item being “Is your current position the one that you indicated as your first choice during the application process?” Answers were coded 0 (yes) or 1 (no).

There were 70 individuals who worked as managers in their position of first choice, and 33 individuals who were hired as managers, but not for their preferred position. Among those who were no longer managers, 18 indicated that the new position was their preferred one, whereas for 19, not being a manager anymore was not their preference.

Mediators

At T2, perceived organizational support during change was assessed with three items (Eisenberger et al., Citation1986), an example item being “During the reorganization, I felt that [the organization] really cared about my well-being”, on a response scale from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely). Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable (.90) and an index variable (mean score) was created.

At T2, procedural justice of the change was assessed with one item “The recruiting procedure in this organizational change was done in a fair manner” with response options ranging from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely). This item is a direct question pertaining to the procedure with which the recruitment was undergone during the reorganization.

At T2, job demands were assessed with three items (Sverke & Sjöberg, Citation1994, based on Walsh et al., Citation1980), an example item being “It happens often that I have to work under time pressure”, with a response scale ranging from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely). Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable (.74) and an index variable (mean score) was created.

At T2, job control was assessed with four items (Sverke & Sjöberg, Citation1994, based on Walsh et al., Citation1980), an example item being “I can decide myself how I want to do my work”, with a response scale ranging from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely). Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable (.86) and an index variable (mean score) was created.

Outcomes

At all three time points, job satisfaction was measured with three items (Hellgren et al., Citation1997, based on Brayfield & Rothe, Citation1951), an example item being “I am satisfied with my work”, with a response scale ranging from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely). Cronbach alphas were acceptable (T1 .84, T2 .94, T3 .89) and index variables (mean scores) were created for each time point.

At all three time points, turnover intention was measured with three items (Sjöberg & Sverke, Citation2000), an example item being “I am thinking about finding a job outside of this organization”, with a response scale ranging from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely). Cronbach alphas were acceptable (T1 .87, T2 .90, T3 .82) and index variables (mean scores) were created for each time point.

At all three time points, mental health was measured with twelve items from the GHQ-12 (Goldberg, Citation1979), an example item being “How often during the last weeks have you been able to concentrate on what you are doing?”, with a response scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (all the time). Cronbach alphas were acceptable (T1 .79, T2 .82, T3 .86) and index variables (mean scores) were created for each time point.

Analytical strategy

All analyses were conducted in Mplus (Version 8.2). Path models with manifest variables were estimated due to the complexity of the model, several single-item measures, and the small sample size. To test the hypotheses, a path model was estimated including all three dependent variables (job satisfaction, turnover intentions, mental health) at T2, while controlling for T1 levels of each dependent variable. To test the direct effects (H1, H2), the dependent variables at T2 were predicted by the dependent variables at T1 and the two independent variables at T2 (Model 1). To test the indirect effects (H3-6), the four mediator variables at T2 (perceived organizational support during the change, procedural fairness of the change, job demands, job control) were simultaneously added to the model (Model 2). The mediating and outcome variables were allowed to correlate. Mediation effects were examined by testing the significance of the indirect effect (a*b; where a refers to paths from the independent variables to the mediator variables and b to paths from the mediator variables to the outcome variables), by examining the bias-corrected confidence intervals of the indirect effects which were generated by bootstrapping procedures based on 5,000 samples. Model fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1995) was assessed with the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean square error of approximation (SRMR). In the literature, it is recommended use the full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) technique to deal with missing values in the variables as FIML provides unbiased and efficient estimates and is recommended in the literature (Enders & Bandalos, Citation2001). Therefore, the analysis sample was N = 140, including everyone who responded to the items regarding managerial status loss and non-preference at T2. The same procedure was repeated for the supplemental analyses pertaining to the long-term effects of the job change with the dependent variables at T3, while controlling for T1 levels. Detailed results of these analyses can be found in the supplemental materials.

Results

presents the descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables.

Hypothesis testing

Model fit for Model 1 (direct effects only) with dependent variables estimated at T2, controlled for T1, was adequate: χ2 = 17.39, df = 12, p = .136, CFI = .977, RMSEA = .057, SRMR = .069. Model fit for Model 2 (including both direct and indirect effects) with dependent variables estimated at T2, controlled for T1, was adequate: χ2 = 34.84, df = 24, p = .071, CFI = .978, RMSEA = .057, SRMR = .085.

Hypothesis 1 and 2 proposed that managerial status loss and non-preference would be associated with negative changes in the outcome variables (direct effects). Results from Model 1 revealed that those who no longer were managers after the change reported a decrease in job satisfaction (β = −.20, p = .008) and an increase in turnover intentions (β = .17, p = .026), but no change in mental health (β = −.11, p = .176). Those who were in a non-favored position reported a decrease in job satisfaction (β = −.32, p < .001), an increase in turnover intentions (β = .23, p = .003), and a decrease in mental health (β = −.17, p = .032). We regard Hypothesis 1 supported for job satisfaction and turnover intentions, and Hypothesis 2 fully supported.

Results from Model 2 (with mediating variables included) showed that the direct associations between managerial status loss and changes in job satisfaction and turnover intentions were no longer significant (βjob satisfaction = −.06, p = .296; βturnover intentions = .02, p = .813), the association to mental health was marginally significant (β = −.13, p = .067). The associations between non-preference and changes in the outcomes were all no longer significant (βjob satisfaction = −.07, p = .231; βturnover intentions = .02, p = .739; βmental health = .01, p = .919). summarizes the results regarding the indirect effects.

Table 2. Indirect effects.

Hypothesis 3 suggested that perceived organizational support and procedural justice would mediate the relationship between managerial status loss and change in the outcomes. Managerial status loss was not related to perceived organizational support (β = −.11, p = .186). Perceived organizational support was positively related to job satisfaction (β = .14, p = .036), negatively related to turnover intentions (β = −.21, p = .007), but not significantly related to mental health (β = .03, p = .682). The indirect effect from managerial status loss through perceived organizational support to change in the outcomes was not significant. Managerial status loss had a marginally significant association with procedural justice of the change (β = −.14, p = .073). Procedural justice of the change significantly predicted all outcomes (βjob satisfaction = .23, p = .001; βturnover intentions = −.24, p = .003; βmental health = .26, p = .001). The indirect effects from managerial status loss through procedural justice of the change to change in the outcomes were not significant. Given these results, Hypothesis 3 was not supported.

Hypothesis 4 suggested that perceived organizational support and procedural justice would mediate the relationship between non-preference and change in the outcomes as measured. Non-preference was negatively related to perceived organizational support (β = −.26, p = .001). The indirect effect of non-preference on change in job satisfaction through perceived organizational support was marginally significant using (a*b = −.076, p = .081, 95%CI −.211; −.006), the indirect effect on turnover intentions was significant (a*b = .138, p = .041, 95%CI .029; .349), while no effect on mental health was found. Non-preference was negatively associated with procedural justice of the change (β = −.34, p < .001). Testing the indirect effects of non-preference showed that procedural justice of the change significantly mediated the relationship to change in job satisfaction (a*b = −.161, p = .008, 95%CI −.316; −.058), turnover intentions (a*b = .201, p = .015, 95%CI .049; .424), and mental health (a*b = −.072, p = .010, 95%CI −.147; −.025). Hypothesis 4 was supported, with the exception of the indirect effect from non-preference through perceived organizational support on mental health.

According to Hypothesis 5, we expected that job demands and job control would mediate the relationship between managerial status loss and change in the outcomes. Managerial status loss had a negative association with job demands (β = −.39, p < .001). Job demands were not significantly related to changes in job satisfaction (β = .04, p = .463), were marginally significantly related to changes in turnover intentions (β = −.13, p = .068), and significantly related to changes in mental health (β = −.29, p < .001). The indirect effect of managerial status loss through job demands to job satisfaction was not significant. The indirect effect of managerial status loss through job demands to turnover intentions was marginally significant but the confidence intervals included zero (a*b = .136, p = .088, 95%CI −.042; .351). The indirect effect from managerial status loss to job demands to mental health was significant (a*b = .099, p = .002, 95%CI .047; .183). Managerial status loss was marginally significantly associated with job control (β = −.14, p = .074). Job control was significantly associated with changes in job satisfaction (β = .50, p < .001), turnover intentions (β = −.30, p < .001), and mental health (β = .30, p < .001). The indirect effect from managerial status loss through job control on changes in job satisfaction was marginally significant but the confidence intervals included zero (a*b = −.16, p = .084, 95%CI −.395; .031). The indirect effects from managerial status loss through job control on changes in turnover intentions and mental health were not significant. In sum, Hypothesis 5 received very limited supported; managerial status loss was associated with changes in mental health through job demands.

Hypothesis 6 expected that job demands and job control would mediate the association between non-preference and changes in outcomes. Non-preference was not significantly related to job demands (β = −.00, p = .989), but significantly related to job control (β = −.27, p < .001). There were significant indirect effects of non-preference through job control on job satisfaction (a*b = −.275, p = .002, 95%CI −.509; −.098), on turnover intentions (a*b = .202, p = .010, 95%CI .058; .444), and on mental health (a*b = −.066, p = .010, 95%CI −.131; −.024). In sum, Hypothesis 6 is partially supported; no support at all for job demands, but fully for job control.

Supplemental analyses

Lastly, we wanted to explore whether the associations would also hold true for the prediction of outcomes at T3, controlling for T1 levels of the outcome variables. Detailed results can be found in the Supplemental Materials. Of all the indirect effects, the following were significant: non-preference through procedural justice of the change on changes in job satisfaction at T3 (a*b = −.134, p = .092, 95%CI −.335; −.006), non-preference through job control on job satisfaction at T3 (a*b = −.188, p = .025, 95%CI −.471; −.032), and managerial status loss through job demands on mental health on T3 (a*b = .115, p = .024, 95%CI .017; .271).

Discussion

This study set out to follow an organizational change process within a government agency in the Swedish public sector. The change process incorporated a change of the managerial structure and allocation of positions and tasks, affecting all middle managers within the agency. When evaluating this specific change process, we made the distinction between managerial status loss (whether participants were still managers after the restructuring or not), and non-preference (whether participants obtained the job they preferred or not). The aim of the study was to investigate the longitudinal impact of those two variables on changes in job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and mental health. Moreover, we tested the mediating role of perceived organizational support during the change process, perceived procedural justice of the change implementation, perceived job demands, and perceived job control after the change process. Additionally, we explored the impact of time on these relationships in our supplemental analyses.

Discussion of results

As expected, managerial status loss had mostly negative consequences, such as decreased job satisfaction and increased turnover intentions directly after the change implementation. Based on sensemaking (Weick, Citation2001) and findings on attributions of promotion decisions (Webster & Beehr, Citation2013), we expected that managers who underwent status loss would evaluate the justice of the process and support from the organization negatively, resulting in negative change reactions. Moreover, we expected that managers who underwent status loss would have less positive change outcomes due to higher perceived demands and lower job control in their new jobs. However, our results showed that that managerial status loss was associated with increased mental health in the short-term as well as in the long-term. This relationship was mediated by job demands, which were lower among participants who no longer were managers. Those who remained in managerial roles had an increased risk of ill-health, which could be explained by the higher perceived job demands in this group. This result is consistent with observations in many public sector organizations and government agencies there is a pressure to increase efficiency and cut costs (Bozeman, Citation2010), which may potentially have negative health consequences for the middle managers who are responsible for implementing the changes:. Our finding is also in line with another Swedish study that reported excessive workload and increased administrative burden for public sector managers after reorganization (Wallin et al., Citation2014). In our study the managers were also the ones who were directly affected by the change, at the same time as they had to carry out the implementation of the change process, which likely added to their perception of job demands being high.

Research thus far has considered the negative effects of demotion on employees (Hennekam & Ananthram, Citation2020; van Dalen & Henkens, Citation2018) but not explicitly focusing on managers being demoted. Losing managerial status is an external change that is visible to others, which may contribute to shape the reactions to this loss. As the chosen mediators in this study did not explain much of the relationship between managerial status loss and the outcome variables, other mediating factors that capture the social aspects of status loss may be more relevant to investigate in future studies. Even if the status loss was voluntary, colleagues and former subordinates may express sympathy or doubts about the managerial qualities of the former manager. The former manager may suffer from lack of self-esteem, heightened negative emotions, doubts about the importance of their job, they may struggle to find a new role identity, and may even perceive a lack of support and trust from colleagues. Here, qualitative approaches that include interviews with former managers about their decision-making process, their reasons for choosing to discontinue their managerial career, and their perceptions of how colleagues and superiors view them after the organizational change may provide fruitful new avenues to study in order to further understand what status loss, and, in particular, managerial status loss means.

For non-preference, results were largely in line with our expectations, which were based on the person-environment fit literature (Kristof-Brown et al., Citation2005) and arguments from sensemaking theory (Weick, Citation2001). Those managers who were moved to a non-preferred job reported decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and decreased mental health. These relationships were mediated by procedural justice of the change and job control, and partly by perceived organizational support, such that those who did not get their preferred role perceived less procedural justice, less job control and less support from the organization, which was related to negative work attitudes and poorer mental health. Looking at the long-term results, more than one year after the decisions on job allocations took effect, the direct relationship to turnover intentions and indirect relations to job satisfaction endured, which suggests that the decision-making of the re-organization may have a lasting effect on work attitudes. While organizational restructuring is a stressful experience for many employees, resulting in uncertainty and potential losses, in the present organizational change process we found higher and more significant relations with non-preference than managerial status loss. Specifically, those who got their preferred position reported higher perceptions of support, fairness, job control, job satisfaction, intentions to stay, and health. It is impossible to give all employees what they want, but future studies may examine how the negative effects of assigning individuals to non-preferred positions can be mitigated. Drawing on the fairness literature at large, it may be that informational justice, in terms of receiving adequate, timely, and truthful explanations for negative decisions, may counteract some of the negative effects (Skarlicki et al., Citation2008).

The indirect effects showed that the change literature may be well advised to complement the focus on process factors with an increased focus on how change recipients perceive their jobs after the change effort. Both perceived organizational support during the change process and procedural justice of the change implementation are important indicators of the social exchange relationship between employee and employer (Cropanzano et al., Citation2017). Process factors related to the social exchange relationship have been given more focus in the change literature than job characteristics (Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1999; Datta et al., Citation2010). In addition to these process factors, this study highlights that job characteristics may also be underlying mechanisms contributing to individuals’ change reactions (Kivimäki et al., Citation2000). Job demands may be particularly important to track over longer time periods to explore how they relate to mental health.

This study investigated the short-term effects of the change implementation in addition to exploring the longer-term consequences. The tested associations, short-term (two months after implementation) and long-term effects (17 months after implementation) did not all exhibit the same pattern. For job satisfaction, managerial status loss and non-preference had short-term direct effects which did not last over time. The mechanisms linking managerial status loss and non-preference to job satisfaction were procedural justice of the change and job control, and their indirect effects were present both immediately and over a longer period of time. These results suggest that organizational changes in terms of managerial status loss and non-preference for the new job can have a persistent effect on job satisfaction over time, but also that these effects are mediated through perceptions of the change process and job characteristics. For turnover intentions, direct and indirect effects were largely short-term and only the direct effect from non-preference persisted over time. These results regarding turnover intentions appear to be consistent with the ideas of adaptation and person-environment fit, such that a mismatch may be temporary and individuals adapt to their new environment over time (Caldwell, Citation2011; Lewin, Citation1951). For mental health, job demands helped explain the relationship from managerial status loss and non-preference; indirect effects were short-term and became stronger long-term. These results are in line with the expectation that organizational changes can undermine health long-term and that effects take some time to manifest (de Jong et al., Citation2016; Ganster & Rosen, Citation2013). In the downsizing literature, longitudinal studies with several points of measurement found various patterns of relationships (de Jong et al., Citation2016). While one study found a decrease in self-rated health right after the restructuring but not four years later, another study found that work attitudes improved after the restructuring, yet, three studies found a negative effect of restructuring on well-being in the short- as well as the long-term (de Jong et al., Citation2016). These differing patterns of the consequences of restructuring over several measurement points highlight the relevance of assessing several individual, work, and health outcomes, in addition to evaluating organizational change reactions at several points in time after the change has been implemented. The present study contributes to the literature on change processes in the public sector by its focus on a Swedish agency and longitudinal design, as it was noted that most of the existing studies have an Anglo-Saxon origin and that longitudinal studies on the implementation and consequences of public management change efforts are needed (Kuipers et al., Citation2014). However, instead of measuring reactions post-change at only two time points, it will be important to collect data at a sufficiently large number of time points so that, for example, time series analyses would be possible, which would be useful in order to better understand changes in reactions over time.

Practical implications

In this paper, we argued that managerial status loss as a result of a re-allocation of jobs may be a stressor, whereas keeping their managerial status might act as a resource for managers. However, the results of our study indicate that retaining the status of a manager may actually be a risk factor for poor mental health due to higher perceived job demands, as compared to those who lost their managerial status. As enactors of change, managers need to be role models (Melkonian et al., Citation2011), and our results suggest that to operate in a changed work environment may be perceived as demanding by managers. Organizations need to protect managers from job demands after the implementation of a change process, and provide them with tools to meet potentially increased demands.

Individuals who did not get their preferred job reported less positive work outcomes and poorer mental health directly after the change and the negative effects on work attitudes carried through to some extent even more than a year after the restructuring was implemented. It seems that perceived procedural justice of the change, job control, and, to some extent, perceived organizational support are important mechanisms linking organizational changes to employee reactions. Organizations undergoing change should try to assess the needs of employees, as employees are usually good at judging their personal work-environment fit, and this would facilitate for HR professionals to consider person-environment fit as well as job preference when allocating re-defined roles during change processes. Further, the process by which this is done, the support given to employees during the change process, as well as job quality are important aspects that HR professionals may need to take into consideration when they design new work roles and prepare and implement change processes.

When the entire management structure is re-organized and new positions are formed and announced, HR professionals have a critical role in supporting managers through the process. In the present empirical example, the internal HR professionals did not participate in supporting middle managers to any greater extent. A challenge the HR professionals faced was that offices were spread out over the country whereas HR was located at the head office. Also, HR professionals were mindful of not being seen as partial to any particular manager if they gave support or advice. While some external coaching was made available to all managers, the uptake was limited, resulting in many middle managers not getting any support. Therefore, it might be valuable for HR professionals to provide more formalized internal support to all the managers affected by the change. Providing career coaching to all affected managers as part of the change process may also be a good strategy for HR professionals to consider employing, especially when organizational changes may lead to a significant decrease in certain positions and may result in some individuals being assigned non-preferred roles.

Methodological considerations and future research

Despite our attempt to test predetermined hypotheses with a rigorous methodological approach, we want to outline several possible limitations of the present study. First, the context is important to consider. In Sweden, the status of managers may be less desirable compared to other countries, as Sweden is relatively low on the power-distance cultural dimension (Hofstede, Citation2001), and salary differences for various positions are smaller compared to more capitalism-oriented countries, which may result in managerial status loss being less problematic in the present study than it would in other countries. The study was conducted within a single public sector agency where the restructuring included no mandated downsizing, and the turnover rate at the agency was very low (below 1 per cent). The results may therefore be limited in generalizability because of the specific jobs the people did at the agency. It may be that individuals felt they had to stay with their organization, since perhaps their jobs did not exist in the private sector, which may create a higher need to adjust and adapt to the new environment rather than leave the environment. The context may have also made an organizational change particularly challenging, since employees in this context may expect stability due to the lack of changes in the past. While organizational changes in public sector organizations such as local and central government agencies or health care providers have become more widespread during the last decade (Bozeman, Citation2010; Kiefer et al., Citation2015), public sector organizations often still operate in a regulated labor market with relative high job security and low turnover. The results reported in the present study may not be generalizable to the entire population of public and private organizations, but rather to relatively protected organizations such as government agencies.

Another limitation pertains to the sample. Although there were different categories for managers, few of them made a transition to a higher (less than one per cent of the sample) or lower (six percent) managerial position. Because of these small sample sizes, we decided to not make a further split into those managers who transferred to lower versus higher positions. The sample size was limited by the number of managers working at the governmental agency, and of course by whether those invited to participate in the study. Thus, a limitation of the current study is a potential lack of power to detect smaller significant associations.

A limitation, but simultaneously an avenue for future research, is that we investigated the mediating potential of several mediators in parallel. However, mechanisms can also be tested in serial. For instance, it has been suggested that social support during organizational change can have a positive impact on perceived control (Oreg et al., Citation2018). Given our study design, this was not possible to test in the present study, but future research may explore this in order to disentangle whether mediators such as those studied in this present study may be best represented in a serial model. Likewise, while we argued and tested the mediating mechanisms for the associations between managerial status loss and non-preference for change reactions, there might also be important moderating effects. For instance, it is common to combine the effect of job characteristics like job demands and job control on outcomes (Karasek & Theorell, Citation1990). Because of the complexity of our model and our limited sample size, we decided not to test these here, but future studies with larger sample sizes could incorporate interaction terms between job characteristics, or perhaps between job characteristics and change process variables. Furthermore, all mediating variables were measured as subjective perceptions, and changes in perceptions over time may to varying degrees mirror objective changes in the mediating variables. For employees who switched from managerial to non-managerial roles, the reports on job demands and job control may perhaps be more representative of actual changes than the reports from those who switched from one managerial role to another.

Another avenue for future studies is to also investigate further of any potential interactions between changes in job status and job preference. The current study did not allow for the testing of this in a reliable way because the sample size was too small. It would be important for future studies to test whether those managers who kept their status as managers and received the job they preferred felt more positively towards the change and their work environment than those who did not keep their status as managers but received the job they preferred. More data and empirical information on the process and consequences of the strategy of re-applying for positions with the employing organization would be highly valuable, as this practice is not uncommon.

Lastly, the time lags implemented in the study design may have not been perfect to detect all relationships. The mediators and reactions in terms of work attitudes and mental health were measured eight weeks after the change implementation, which may not be ideal to allow time for employees to truly settle into their new positions with the changes in circumstances relating to tasks, procedures, and structures. Additionally, to better understand the adjustment to, and acceptance or disillusionment of, managers in their new roles, more intensive data collections, with more frequent measurement points, and qualitative approaches could complement the current study. However, a strength of the study is that the independent variables refer to objective circumstances.

Conclusions

This study set out to follow all middle managers at a governmental agency in Sweden, in which the managerial structure was fundamentally changed. Results suggest that the restructuring was perceived very differently depending on a variety of factors. Managers who lost their managerial status had initially less favorable work attitudes, but over time reported better mental health, which was mediated through lower levels of job demands. Those who were moved to a position they initially did not prefer reported less favorable work attitudes and poorer mental health directly after the change than those who were assigned to their preferred role. These associations were mediated by lower levels of perceived procedural justice of the change, job control, and, to some extent, perceived organizational support. Even more than a year after the organizational change was implemented the negative associations with job satisfaction through the effects of procedural justice of the change and job control remained. This study highlights the relevance of objective changes to positions, the incorporation of process factors and job characteristics in order to better understand the underlying mechanisms linking organizational changes to individuals’ reactions, as well as the relevance of studying managers’ work attitudes and health variables as outcomes of organizational change over several points of time.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

All authors discussed the idea and structure of the paper. CE analyzed the data, CE and CBO wrote the first draft. All authors helped revise the manuscript. CBO and KN collected the data. All authors agreed with the final version of the manuscript. KN received the grant that enabled the data collection.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by VINNOVA under Grant [2009-03077] and Swedish Research Council for Health, Working life and Welfare [Forte, grant number 2017-0259].

Data availability statement

Data can be made available upon request to the authors.

References

- Abdalla, A., Elsetouhi, A., Negm, A., & Abdou, H. (2018). Perceived person-organization fit and turnover intention in medical centers: The mediating roles of person-group fit and person-job fit perceptions. Personnel Review, 47(4), 863–881. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2017-0085

- Armenakis, A. A., & Bedeian, A. G. (1999). Organizational Change: A Review of Theory and Research in the 1990s. Journal of Management, 25(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500303

- Bach, S., & Bordogna, L. (2011). Varieties of new public management or alternative models? The reform of public service employment relations in industrialized democracies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(11), 2281–2294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.584391

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bamberger, S. G., Vinding, A. L., Larsen, A., Nielsen, P., Fonager, K., Nielsen, R. N., Ryom, P., & Omland, Ø. (2012). Impact of organisational change on mental health: A systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 69(8), 592–598. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2011-100381

- Berg Elisabeth, E. B., Barry Jim, J. J., & Chandler John, J. P. (2008). New public management and social work in Sweden and England: Challenges and opportunities for staff in predominantly female organizations. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 28(3/4), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330810862188

- Bond, F. W., & Bunce, D. (2001). Job control mediates change in a work reorganization intervention for stress reduction. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(4), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.4.290

- Bouckenooghe, D., Devos, G., & Broeck, H. v d. (2009). Organizational Change Questionnaire-Climate of Change, Processes, and Readiness: Development of a New Instrument. The Journal of Psychology, 143(6), 559–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980903218216

- Boyd, C. M., Tuckey, M. R., & Winefield, A. H. (2014). Perceived effects of organizational downsizing and staff cuts on the stress experience: The role of resources. Stress and Health : journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 30(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2495

- Bozeman, B. (2010). Hard Lessons from Hard Times: Reconsidering and Reorienting the “Managing Decline” Literature. Public Administration Review, 70(4), 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02176.x

- Brayfield, A., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35(5), 307–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055617

- Caldwell, S. D. (2011). Bidirectional relationships between employee fit and organizational change. Journal of Change Management, 11(4), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2011.590453

- Campbell, W. K., & Sedikides, C. (1999). Self-Threat Magnifies the Self-Serving Bias: A Meta-Analytic Integration. Review of General Psychology, 3(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.3.1.23

- Chauvin, B., Rohmer, O., Spitzenstetter, F., Raffin, D., Schimchowitsch, S., & Louvet, E. (2014). Assessment of job stress factors in a context of organizational change. European Review of Applied Psychology, 64(6), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2014.09.005

- Chen, D., & Wang, Z. (2014). The effects of human resource attributions on employee outcomes during organizational change. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(9), 1431–1444. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.9.1431

- Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E., Daniels, S., & Hall, A. (2017). SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY: A CRITICAL REVIEW WITH THEORETICAL REMEDIES. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 479–516. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099

- Cullen, K. L., Edwards, B. D., Casper, W. C., & Gue, K. R. (2014). Employees’ adaptability and perceptions of change-related uncertainty: Implications for perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(2), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9312-y

- Datta, D. K., Guthrie, J. P., Basuil, D., & Pandey, A. (2010). Causes and Effects of Employee Downsizing: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of Management, 36(1), 281–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309346735

- Davies, A. (2000). Change in the UK police service: The costs and dilemmas of restructured managerial roles and identities. Journal of Change Management, 1(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/714042456

- Day, A., Crown, S. N., & Ivany, M. (2017). Organisational change and employee burnout: The moderating effects of support and job control. Safety Science, 100(Part A), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.03.004

- de Jong, T., Wiezer, N., de Weerd, M., Nielsen, K., Mattila-Holappa, P., & Mockałło, Z. (2016). The impact of restructuring on employee well-being: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Work & Stress, 30(1), 91–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1136710

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived Organizational Support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

- Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(3), 430–457. [Database] https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

- Feng, D., Su, S., Yang, Y., Xia, J., & Su, Y. (2017). Job satisfaction mediates subjective social status and turnover intention among Chinese nurses. Nursing & Health Sciences, 19(3), 388–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12357

- Ganster, D. C., & Rosen, C. C. (2013). Work stress and employee health: A multidisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1085–1122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313475815

- Goldberg, D. (1979). Manual of the general health questionnaire. NFER Nelson.

- Hall, P. (2013). NPM in Sweden: The Risky Balance between Bureaucracy and Politics. In Å. Sandberg (Ed.), Nordic lights: work, management and welfare in Scandinavia. (pp. 406–419). Studieförbundet Näringsliv och samhälle.

- Hellgren, J., Sjöberg, A., & Sverke, M. (1997). Intention to quit: Effects of job satisfaction and job perceptions. In F. Avallone, J. Arnold, & K. de Witte (Eds.), Feelings work in Europe. (pp. 415–423). Guerini.

- Hennekam, S., & Ananthram, S. (2020). Involuntary and voluntary demotion: Employee reactions and outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(4), 586–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1733980

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Cultures consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. (2 ed.). Sage.

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1995). Evaluating model fit. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. (pp. 76–99). Sage.

- Karasek, R. A., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books.

- Kiefer, T., Hartley, J., Conway, N., & Briner, R. B. (2015). Feeling the Squeeze: Public Employees’ Experiences of Cutback- and Innovation-Related Organizational Changes Following a National Announcement of Budget Reductions. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(4), 1279–1305. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu042

- Kivimäki, M., Vahtera, J., Pentti, J., & Ferrie, J. E. (2000). Factors underlying the effect of organisational downsizing on health of employees: Longitudinal cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 320(7240), 971–975. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7240.971

- Kivimäki, M., Vahtera, J., Pentti, J., Thomson, L., Griffiths, A., & Cox, T. (2001). Downsizing, changes in work, and self-rated health of employees: A 7-year 3-wave panel study. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 14(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800108248348

- Knapp, J. R., Smith, B. R., & Sprinkle, T. A. (2014). Clarifying the Relational Ties of Organizational Belonging: Understanding the Roles of Perceived Insider Status, Psychological Ownership, and Organizational Identification. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051814529826

- Knight, E. L., & Mehta, P. H. (2017). Hierarchy stability moderates the effect of status on stress and performance in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(1), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1609811114

- Korsgaard, M. A., Sapienza, H. J., & Schweiger, D. M. (2002). Beaten Before Begun: The Role of Procedural Justice in Planning Change. Journal of Management, 28(4), 497–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800402

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individual’s fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

- Kuipers, B. S., Higgs, M., Kickert, W., Tummers, L., Grandia, J., & Van Der Voet, J. (2014). The management of change in public organizations: a literature review. Public Administration, 92(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12040

- Lam, S. S. K., & Schaubroeck, J. (2000). The role of locus of control in reactions to being promoted and to being passed over: A quasi experiment. Academy of Management Journal, 43(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556386

- Lawrence, S. A., & Callan, V. J. (2011). The Role of Social Support in Coping during the Anticipatory Stage of Organizational Change: A Test of an Integrative Model. British Journal of Management, 22(4), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00692.x

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. Harper.

- Marzucco, L., Marique, G., Stinglhamber, F., De Roeck, K., & Hansez, I. (2014). Justice and employee attitudes during organizational change: The mediating role of overall justice. European Review of Applied Psychology, 64(6), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2014.08.004

- Melkonian, T., Monin, P., & Noorderhaven, N. G. (2011). Distributive justice, procedural justice, exemplarity, and employees’ willingness to cooperate in M&A integration processes: An analysis of the Air France-KLM merger. Human Resource Management, 50(6), 809–837. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20456

- Michel, A., Stegmaier, R., & Sonntag, K. (2010). I scratch your back—you scratch mine. Do procedural justice and organizational identification matter for employees’ cooperation during change?Journal of Change Management, 10(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010903549432

- Oreg, S., Bartunek, J. M., Lee, G., & Do, B. (2018). An affect-based model of recipients’ responses to organizational change events. Academy of Management Review, 43(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0335

- Oreg, S., Vakola, M., & Armenakis, A. (2011). Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47(4), 461–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886310396550

- Rigotti, T., Korek, S., & Otto, K. (2014). Gains and losses related to career transitions within organisations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.12.006

- Shepperd, J., Malone, W., & Sweeny, K. (2008). Exploring causes of self-serving bias. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 895–908. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00078.x

- Sjöberg, A., & Sverke, M. (2000). The interactive effect of job involvement and organizational commitment on job turnover revisited: A note on the mediating role of turnover intention. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 3, 247–252.

- Skarlicki, D. P., Barclay, L. J., & Douglas Pugh, S. (2008). When explanations for layoffs are not enough: Employer’s integrity as a moderator of the relationship between informational justice and retaliation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81(1), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317907X206848

- Sverke, M., & Sjöberg, A. (1994). Dual commitment to company and union in Sweden: An examination of predictors and taxonomic split methods. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 15(4), 531–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X94154003

- Thakur, R. R., & Srivastava, S. (2018). From resistance to readiness: The role of mediating variables. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 31(1), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-06-2017-0237

- Tong, J., Wang, L., & Peng, K. (2015). From person-environment misfit to job burnout: Theoretical extensions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-12-2012-0404

- Tvedt, S. D., Saksvik, P. Ø., & Nytrø, K. (2009). Does change process healthiness reduce the negative effects of organizational change on the psychosocial work environment?Work & Stress, 23(1), 80–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370902857113

- van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2018). Why demotion of older workers is a no-go area for managers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(15), 2303–2329. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1239214

- van den Heuvel, S., Schalk, R., & van Assen, M. A. L. M. (2015). Does a well-informed employee have a more positive attitude toward change? The mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment, trust, and perceived need for change. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 51(3), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886315569507

- van der Voet, J. (2014). The effectiveness and specificity of change management in a public organization: Transformational leadership and a bureaucratic organizational structure. European Management Journal, 32(3), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.10.001

- Wallin, L., Pousette, A., & Dellve, L. (2014). Span of control and the significance for public sector managers’ job demands: A multilevel study. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 35(3), 455–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X13488002

- Walsh, J. T., Taber, T. D., & Beehr, T. A. (1980). An integrated model of perceived job characteristics. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 25(2), 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(80)90066-5

- Webster, J. R., & Beehr, T. A. (2013). Antecedents and outcomes of employee perceptions of intra‐organizational mobility channels. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(7), 919–941.

- Weick, K. E. (2001). Making sense of the organization. Blackwell Publishing.

- Westgaard, R. H., & Winkel, J. (2011). Occupational musculoskeletal and mental health: Significance of rationalization and opportunities to create sustainable production systems - A systematic review. Applied Ergonomics, 42(2), 261–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2010.07.002

- Worley, C. G., & Mohrman, S. A. (2014). Is change management obsolete?Organizational Dynamics, 43(3), 214–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2014.08.008