Abstract

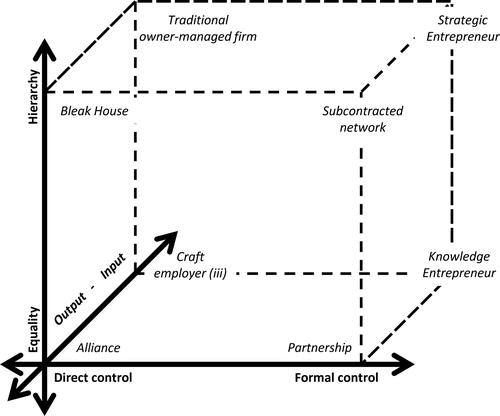

The diversity of practices observed in small enterprises demands a new evaluation of HRM with respect to its phenotypes and functions. By bringing HRM back to its functional requirements as represented by the need to control the human side of work as well as the differentiation and integration of tasks, we develop a configurational model of eight ideal types of HRM, that resonate in previous research as well as in emerging organization types in the networked economy. Based on varying positions along the hierarchy, formalities and input- or output-oriented dimensions of control, we discern craft employers, traditional owner-managers, and strategic-, knowledge-, and bleak house entrepreneurs from subcontracted work, alliances and partnerships. Because control serves as a bridge between agency and structure, the proposed classification offers an analytical starting point for detecting, describing, contrasting, comparing and contextualizing empirically observed HRM configurations in a broad diversity of small enterprises. The approach offers a mid-range theory, which allows for generalization across small enterprises without the risk of losing peculiar responses to enacting HRM.

Introduction

Micro and small businesses can be creative when it comes to the organization of work and workers to meet business objectives – the essence of HRM (Boxall & Purcell, Citation2011). Universalistic models and measures developed in the context of larger organizations do not appropriate the phenomenon of HRM in small firms well. Over the past decades, integrative qualitative research have shown that small firm parameters (e.g. smallness and age), interact in dynamic ways with contextual conditions (e.g. industry and labour market) and specific conditions of the organization itself (e.g. ownership and resources), which bring about HRM approaches different from large organizations (Edwards et al., Citation2006; Harney & Alkhalaf, Citation2020). Depending on the mix of conditions, HRM systems can take form as pragmatic but intelligent (e.g. Marchington et al., Citation2003), as a series of informal adjustments between owners and workers (e.g. Marlow & Patton, Citation2002), and as potentially exploitative of workers (e.g. Ram et al., Citation2007). The phenomenal range of HRM approaches in small firm contexts challenges the progression of research (Harney & Alkhalaf, Citation2020).

In this contribution, we propose taking the control of workers and work, the first task of any organization no matter its size, as an analytical starting point for detecting, describing, contrasting, comparing and contextualizing HRM in a broad diversity of small enterprises. Control concerns the ability of organizations to ensure desired behaviour from workers, which makes it a central concept to HRM (e.g. Snell, Citation2011), employment and industrial relations (Gill, Citation2019; Kaufman, Citation2010; Storey, Citation1985), alternative work arrangements in the new economy (e.g. Cappelli & Keller, Citation2012) and management studies (e.g. Bedford & Malmi, Citation2015). Control exercised in response to the need to secure workers on the one hand and the organization of work on the other can vary along dimensions of (in-)formality, authority and input-output (Whitley, Citation1999), which combine into a typology of eight HRM configurations. The typology extends previous configurational research (e.g. Edwards et al., Citation2006) by adding the dimension of close versus distant control over employee behaviour (input versus output oriented control) (Whitley, Citation1999), such that output oriented work arrangements like subcontracting and platform work can also be accounted for as a means to control work and workers.

In contrast to earlier integrative studies, the typology does not include conditions mapping the organization in its context (e.g. product or labour market). The typology serves as a midrange theory that is detailed enough to diagnose small organizations but broad enough to allow for generalization across cases (Fiss, Citation2007; Weick, Citation1989), which offers methodological advantages in capturing the nature, causes and consequences of HRM for small organizations (Bacharach, Citation1989).

The added value of analysing HRM in small organizations as a set of responses to the requirement of controlling work and workers is threefold. First, the approach offers an opportunity to go beyond checklists of HR practices and to understand how observed HR practices serve to control workers and the organization of work (Harney & Alkhalaf, Citation2020). Second, control bridges the selection of HR practices on the one hand, to internal and external determinants of the organization and to choices and preferences of the entrepreneur on the other (Edwards et al., Citation2006; Storey, Citation1985). This will facilitate systematic integrative studies, wherein HRM is seen as an integral part of the characteristics of the small organization itself, of its larger socioeconomic context, and as the outcome of strategic choice and agency in response to the environment (Heracleous & Hendry, Citation2000). Third, the typology extends to include non-traditional, twenty first century work relationships, which improves capturing some creative ways in which small enterprises organize work and workers. Finally, in consulting with small firm employers, the typology serves to advice on alternative, equally effective ways to organize HRM that contribute to decent work for workers and to business success.

The article is structured as follows. In the second section, we delineate the elements that make up the phenomenon. In the third section, we provide an overview of existing integrative conceptualizations of HRM in small enterprises and indicate existing gaps in the research. Thereafter, we delineate the theoretical foundations of the control of work and work relationships, and indicate how these relate to HR practice in small enterprises. This section is followed by the typology of HRM configurations associated with various positions on the control dimensions. Example propositions illustrate how each type can be integrated into its structural and dynamic contexts. In the final section, we discuss avenues for future research.

Theory

Delineating the phenomenon

Building a typology of HRM configurations for small organizations begins with defining its elements. Small organizations are bounded social entities, whose persistence depends on the replication of routines and competencies by those who make a living of it, including owner-managers, employees, and working family members (Aldrich, Citation1999). Especially in smaller enterprises, resource constraints result in alternative, flexible types of work, which erode the meaning of the term ‘employee’. First, the term does not refer to a legally defined entity, which leaves room for broad interpretations (Wynn, Citation2016). Moreover, new types of employment contracts, such as contracting self-employed employees (Flinchbaugh et al., Citation2020), posting work on platforms (Duggan et al., Citation2020), or engaging employees as shared owners (Wynn, Citation2016), erode the boundaries between employers and employees. Rather than speaking of employment relations, speaking of work relationships or work arrangements seems more accurate. Work relationships concern economic work, involving any activity undertaken for an organization in exchange for compensation (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2012).

HRM focuses on which procedures, systems and behaviours to put in place to control the human side of work as well as the organization of work itself, such that organizational goals are met (Boxall & Purcell, Citation2011). Small firm business goals can be as diverse as the continuity of family income, the drive to ‘stay alive’, or the pursuit of nonfinancial personal enjoyment (Combs et al., Citation2018; Edwards & Ram, Citation2006; Reijonen & Komppula, Citation2007). The diversity of organizational goals and work relationships indicates ambiguity: it is expected that there are different, but similarly effective approaches to HRM for small organizations. This notion of equifinality is the cornerstone of configurations theory (Short et al., Citation2008).

Integrative perspectives of HRM in small organizations

When asked about their management of employees, small business owners describe their approach as involving an interrelated flow of activities rather than a number of single practices (Drummond & Stone, Citation2007; Heneman et al., Citation2000). This observation of ‘fit’ between practices that provide synergy in alignment with organizational strategies and the organizational context to advance firm survival and growth is commonly made in HRM theory (Boon et al., Citation2019; Delery & Doty, Citation1996; Paauwe & Farndale, Citation2017). According to configuration theory, there is no single universalistic HRM model that works for all organizations, but instead, there are multiple ways to reach the same outcome, albeit not all are equally effective (Short et al., Citation2008). Because ineffective configurations have lower survival rates, over time, organizations form stable constellations of management practices, operations, strategies and values that together reinforce each other to influence their performance in the market, making the system stable and resistant to change (Miller, Citation1987; Sheppeck & Militello, Citation2000). Endless variety (idiosyncrasy) is therefore unlikely because in reality, only a limited number of configurations – ideal types or “gestalts” – are fit for survival.

The logic of configurations is widely used in integrative studies of HRM in small firms, where the nature of work and work relationships is considered an integral part of social structures at various levels, which reinforce or challenge the status quo in a particular enterprise. Some conditions, such as product and industry characteristics, demographics and culture, exist within the more stable, structural context of organizations. Other conditions are more temporal, such as economic turmoil or changed legislation, and indicate tensions that challenge the present nature of HRM. Finally, some conditions relate to managerial choice and are therefore more dynamic in nature, indicating not only a deterministic influence of contextual conditions but also the power and agency of entrepreneurs and workers to alter and deviate from existing practice (Giddens, Citation1984; Harney & Alkhalaf, Citation2020; Johns, Citation2006).

provides a chronological overview, by way of illustration, of theoretical and empirical publications that apply an integrative approach to studying the nature of work and work relationships in small organizations. Although there is some agreement on the types of conditions considered, the overview also shows substantial divergence. What is commonly mentioned are structural conditions such as products, sectors, and regulatory contexts; an organization’s positioning in a production chain; embeddedness in specific labour markets and a lack of union involvement.

Table 1. Overview of integrative approaches to the control of work relationships in small organizations.

The papers diverge with respect to the stable influence of contexts vis a vis strategic choice. Some papers take a deterministic position on the influence of context (Barrett & Rainnie, Citation2002; Goss, Citation1991; Lacoursière et al., Citation2008; Rainnie, Citation1985). However, mediating structures that can induce changes emerge as well, such as changes in the labour market (e.g. Edwards & Ram, Citation2006; Kroon & Paauwe, Citation2014), generations in family firms, or more broadly speaking, in the presence of ‘presenting issues’ that challenge the status quo (Harney & Alkhalaf, Citation2020). A number of papers also highlight managerial choice or style (e.g. Baron et al., Citation1996; Cappelli & Keller, Citation2012; Edwards et al., Citation2006; Goffee & Scase, Citation1995; Harney & Dundon, Citation2006; Kroon & Paauwe, Citation2014).

Overall, the overview emphasizes the need to contextualize HRM in small organizations. At the same time, various levels of context interact in complex ways, with temporal stability guiding and guided by the behaviour of small enterprise owners and workers. As Harney and Alkhalef (2020) observe in their review, there is a need for a contingency-based approach that explores how HR practices in small organizations actually function. The authors call for phenomenon-driven research whereby determinants manifest themselves in configurations where HRM supports the survival of the organization in its context. Given the wide scope of determinants considered, this may prove a challenging task. To find middle ground between identifying idiosyncrasies and the failure of large-N studies to consider specific HRM responses of small organizations, we propose a midrange theory that addresses the need for parsimony while not trying to capture the full contextual complexity of each case (Bacharach, Citation1989). Following Fiss (Citation2007), we propose a set-theoretic approach, which means that we begin with observing actions of control over work and work relationships before engaging in interpretational discourse on the causes and nature of control. Systematic comparisons between cases then determine which combinations of organizational and contextual conditions are associated with various approaches to the control of work and work relationships and related HRM practices.

Functional requirements of HRM

Our approach centres on the concept of control over work and work relationships. An individual, self-employed entrepreneur has few concerns in this respect, performing all tasks by him- or herself; however, the situation becomes more complicated once collaboration with another person is introduced (Boxall & Purcell, Citation2011; Goffee & Scase, Citation1995). At this point, functional questions about collaboration and task division arise, which will shape the work relationship. Functional requirements are indispensable functions that have to be fulfilled in any organization (irrespective of its size) for it to be effective (Gresov & Drazin, Citation1997). In any organization, two functional requirements have to be met: 1) ensuring the presence of workers (the human factor) and 2) the differentiation and integration of tasks (the work design factor) (Aldrich, Citation1999; Jaffee, Citation2001).

The human factor requires organizations to recruit workers and to manage relationships with them (Aldrich, Citation1999). This process begins with finding workers: who is asked to join the organization and which networks are used to find candidates (Aldrich, Citation1999; Behrends, Citation2007)? Once workers are chosen, the next task is to ensure that their contributions last as long as the organization needs them, which implies the control of work relationships (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2012).

The differentiation and integration of work involve deciding on ways to divide tasks among workers, for example, the need to specialize between members or to departmentalize the organization. Differentiating tasks also induce a need to integrate install mechanisms to coordinate work by means of procedures, leadership and organizational hierarchies (Jaffee, Citation2001; Lawrence & Lorsch, Citation1967; Mintzberg, Citation1979).

HR practices are the controls used to deal with the functional requirements. Based on Boxall and Purcell (Citation2011, p. 3), we distinguish HR practices into employment practices (the human factor) and work design practices (task related). Employment practices ‘include all the practices used to recruit, deploy, motivate, consult, negotiate with, develop and retain workers’. Work practices ‘have to do with the way the work itself is organized and any associated opportunities to engage in problem solving and change management regarding work processes (such as quality circles and team meetings)’.

displays the functional requirements and illustrates some potential HR practices that can be observed in small organizations. The examples of HRM practices listed in show that different HR practices can contribute to meeting the same functional requirement. Moreover, the same HR practice can contribute to meeting different functional requirements. For example, by clustering the HR practices of 1230 SMEs, Innes and Wiesner (Citation2012) showed that training appears in a bundle of practices ensuring workers are qualified for tasks (recruiting members from the ranks of the organization) while also in a bundle of motivation practices to ensure the continuity of work relationships. Various combinations of responses to functional requirements are possible and can equally contribute to organizational goals. As long as responses to the functional requirements of control help reach small firm goals, such configurations have equifinal worth (Fiss, Citation2007).

Table 2. Functional requirements and possible HRM responses.

Scoping variations of control

HR practices are the tools used to control the human side of work as well as the differentiation and integration of tasks. In this section, we scope control style responses to the functional requirements. The style of control ranges along dimensions of 1) formality and informality, 2) hierarchical power and equality and 3) input and output control.

Formality involves a reliance on more formal or more direct control procedures. Formal control diminishes the need for interaction between the owner-employer and workers and replaces this with instrumental artefacts such as measures and formal procedures. The opposite of formal control is not simply informal control (i.e. the absence of formal control) but direct control. When formal rules are absent, control is exercised through close interaction, where decisions are made on a personal, case-by-case basis (Marlow & Patton, Citation2002; Whitley, Citation1999). Direct control in the absence of formal control may create tensions - for example, without formality, superiors find it difficult to express their expectations and obligations to their workers (Gilman & Edwards, Citation2008; Nadin & Cassell, Citation2007). However, even when small firms adopt a formal HRM strategy, its use can be piecemeal or reactive (Harney & Dundon, Citation2006). Small businesses’ HRM ranges from nonformal and direct to somewhat more sophisticated and formalised (Rauch & Hatak, Citation2016).

Hierarchy describes the power distance between superiors and workers (Bedford & Malmi, Citation2015; Etzioni, Citation1961; Storey, Citation1985). In a heavily hierarchical relationship, the owner-manager acts in an authoritarian way and minimizes worker autonomy. The opposite end of this dimension can be characterised by equality between management and workers, where a significant amount of control is arranged through egalitarian, horizontal or team-like exchanges (Bedford & Malmi, Citation2015; Ouchi, Citation1979; Scase, Citation2003). Under egalitarian control, superiors work alongside their workers, teaming up for the survival of the company. HR practices for equality, such as year-end profit shares, minimize distinction between owners and workers.

The third control dimension relates to the relative emphasis on results (output control) or on the people who do the job (input control). Input control focuses on the qualities, skills and behaviours of workers (Merchant, Citation1985). In focusing on the individual, management expects the desired results to follow automatically (Bedford & Malmi, Citation2015; Ouchi, Citation1979). In contrast, when using output control, there is no need to become involved with the activities executed by the person carrying out the job, since output control is only concerned with the results and outcomes of the job (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2012; Merchant, Citation1985). Compared to formalization and the authority style (hierarchy), the distinction between behaviour and output control is less prominent in the small organizations literature, but it does come forth in Cappelli and Keller (Citation2012) typology of direct and third-party or subcontracted forms of work relationships and resonates with work in the networked economy. Moreover, the risks of working conditions under output control are highlighted by critics of the ‘small is beautiful’ paradigm, which negate the view that close and personal relationships in small organizations are by definition harmonious (Rainnie, Citation1985).

Eventually, organizations take different positions on each of the control dimensions, which evolve as an outcome from the dualistic interplay between the structural context and employers’ and workers’ agency. These configurations are social constructions that are reproduced in the behaviour and understanding of all actors, i.e. owners and workers (Fiss, Citation2007; Whittington, Citation1992). In their reproduction, configurations are temporary but relatively stable responses in how organizations and their members as a social system respond to the functional requirements.

Typology of control in SMEs

Configurations of responses to meet the functional requirements along the three dimensions of control are associated with specific sets of HR practices, as will be illustrated in this section. For purposes of theoretical advancement and to reduce the range of possible configurations, we only describe combinations of the extreme values of the three dimensions, which results in eight ideal-type configurations of HRM. We will illustrate each configuration by drawing on previous research. This approach results in labelling the resulting configurations as traditional owner-manager firms, strategic entrepreneurs, craft employers, knowledge entrepreneurs, Bleak Houses, subcontracted networks, alliances, and partnerships (see ). details examples of HR practices (subdivided into employment and work practices) for each configuration.

Table 3. Configurations with HRM responses to functional requirements.

Following configuration theory, ideal types align with internal (e.g. ownership, strategy, and growth) and external (e.g. the institutional context and labour market) conditions such that there is temporal stability until a presenting issue challenges the status quo (Harney & Alkhalaf, Citation2020). We formulate eight propositions for sample contextual conditions associated with each ideal type. Additionally, we highlight a range of presenting issues that may lead agents who enact one ideal type to adopt another. The propositions are not exhaustive but serve to illustrate how context relates to the stability of and changes in ideal types.

Traditional owner-managed firms resemble Mintzberg’s (Citation1979) simple structure: a centralized organizational structure in which the owner takes a dominant position. Many case studies of small manufacturing, transport or construction organizations have found HRM patterns resembling the traditional owner-manager type (e.g. Grugulis et al., Citation2000; Marlow & Patton, Citation2002; Ram, Citation1991; Ram & Holliday, Citation1993). Authority is centralized in the owner’s proprietorial hands and has been described as charismatic, autocratic (Goffee & Scase, Citation1995) or paternalistic (Goss, Citation1991; Whitley, Citation1999). Workers are employees, and work relationships are (sometimes literally) family-like, so the emphasis is more on personal qualities and behaviour than on output (Senftlechner & Hiebl, Citation2015). To maintain a close and personal family-like climate, work relationships are informal (Whitley, Citation1999). Recruiting members to the organization happens through personal (often family or community) and business networks (Horak, Citation2017; Marchington et al., Citation2003). Changes in demand are primarily met by creating internal numerical flexibility, such as through overtime work (Marlow, Citation2002; Mihail, Citation2004). Continuity is achieved by establishing a close and personal working climate more than through pay or personal growth (Baron et al., Citation1996). Work is functionally divided among staff and integrated in a hierarchical manner with an in-group of owner and family members taking the strategic positions. Employees have little say over strategies and work (Dundon et al., Citation1999; Gilman et al., Citation2015).

Proposition 1a:

Family ownership, local community embeddedness, and the production of traditional craft products reinforce the traditional owner-manager configuration.

Proposition 1a:

Succession is a presenting issue for traditional owner-managed firms, which leads to more formalization of work relationships, as successors are often better educated in management theory and need to mark their authority by adopting a more formal approach to work relationships. The nearest configuration will be strategic entrepreneurs.

Strategic entrepreneurs most closely resemble modern high-performance HRM configurations of large organizations, which are found in growth-oriented start-ups (Barringer et al., Citation2005) involving capital from external investors (Gundry & Welsch, Citation2001), in capital-intensive industries and in organizations closely collaborating with larger firms (Barringer et al., Citation2005). These conditions foster the need for a more formal approach to HRM. Strategic entrepreneurs manage the organization as if it were already a large organization with a mission and a clear vision for how to achieve it (Barringer et al., Citation2005). The approach manifests in an awareness of human capital importance (input control) for achieving business results (Horak, Citation2017). Recruiting members to the organization occurs through selective hiring (Horak, Citation2017). Flexibility is incorporated both quantitatively (overtime pay) and qualitatively (staff training programmes that ensure that employees can take on several roles) (Barringer et al., Citation2005). Stock options and financial incentives attach workers to the organization (Baron et al., Citation1999). Often, strategic entrepreneurs have earlier managerial experience and are embedded in business networks, leading them to mimic “large firm” approaches to work division and control: hierarchical organization layers, functionally specialised managers, and formal regulation of workers’ voice (Davila, Citation2005; Gilman et al., Citation2002; Lacoursière et al., Citation2008).

Proposition 2a:

Being under the reign of external capital reinforces the strategic entrepreneurial configuration because board members representing external capital demand a business plan, insert formal controls, and provide business consulting.

Proposition 2b:

External financers may impose presenting issues to strategic entrepreneurs. Apart from vulnerability to take-over, which marks the end of an independent small business, external financers can require lean strategies, resulting in the outsourcing of parts of the business to supplier organizations. Strategic entrepreneurs could then develop towards subcontracted networks.

Craft employers are microbusinesses based on the specific craft skills of an entrepreneur (e.g. a hairdresser or carpenter) who hires a few employees because there is more work than he or she can handle (Goffee & Scase, Citation1995). Craft employers typically lack entrepreneurial orientation, and their businesses operate in local niches (Monder Ram et al., Citation2001). When determining how to deal with workers, craft employers draw comparisons to other craft employers in the immediate local community, as they do not have the time or interest to invest in in-depth knowledge on HRM (Kitching, Citation2016). Craft employers exercise leadership by working alongside their workers, setting standards of behaviour by acting as role models (Goffee & Scase, Citation1995). As such, hierarchy is exercised through continuous and informal mutual adjustments in the absence of formal management functions. Because leadership involves many face-to-face interactions, craft employers recruit workers that guarantee harmonious interpersonal relationships through informal networks of family and friends (Goffee & Scase, Citation1995; Monder Ram et al., Citation2001). These employers rely on the numerical flexibility of their present staff to meet demands because they doubt the quality of the work of “strangers” (Goffee & Scase, Citation1995). Work division is informally negotiated, and a close and personal working climate ensures employee commitment.

Proposition 3a:

Peer-like relations with workers in craft employers align better with micro firms than with small or medium-sized firms.

Proposition 3b:

There are numerous presenting issues associated with the liability of smallness. For example, regulations for employment protection imposing greater financial risks on employers, lead craft employers to move from being employers to joining alliances of individual self-employed workers.

Knowledge entrepreneurs exist in creative industries, consultancies and the ICT sector, where work is of an intellectual nature and where higher-educated knowledge workers form the majority of the workforce. What these organizations share is the intangible resource of professional knowledge and skills, resulting in a strong emphasis on input control (Alvesson, Citation2000). Professional norms and regulations bring about more formalised work relationships compared to those found among craft employers or traditional owner-manager firms (Whitley, Citation1999). As owners often come from the same profession as their workers and as some workers help sustain networks with customers, egalitarian modes of control prevail ( Goss, Citation1991; Monder Ram, Citation1999 ). Overall, cooperation, trust and interdependence between owners and workers arise (Ram, Citation1999). In recruiting members to the organization, owners use peer referrals within professional networks to find specialist human capital and to ensure embeddedness in professional and customer networks (Behrends, Citation2007). Interesting work and room for professional development (training and taking on new projects) commit workers to these organizations more than competitive remuneration (Barret, Citation1999). Work division is not very strict; there is room to take on new ideas that go extend the job description (Barret, Citation1999). Work is coordinated through procedural informality with everyone adhering to professional rules of conduct, which can be labelled formal because they are agreed-upon working standards (Baron et al., Citation1996). Consultants and IT specialists in small organizations refer to the management style as egalitarian with open communication lines and regular formal meetings (Ram, Citation1999).

Proposition 4a:

The industries in which knowledge entrepreneurs thrive are in specialist business to business services.

Proposition 4b:

Fluctuations in the demand for specialist services pose presenting issues to this configuration. The need to adjust to market demands can cause a move towards subcontracted networks, where specialists are hired for projects on a needs basis. Alternatively, the configuration could develop in a partnership, where all workers become owners and as such responsible for bringing in their own projects.

Bleak Houses, a concept derived from the title of a novel by Charles Dickens, illustrates the potentially exploitative, darker side of working for a small organization (Rainnie, Citation1989). For survival, Bleak House employers compete on prices with larger organizations, resulting in low wages and very minimal investments in equipment or staff (Patel & Cardon, Citation2010). Such enterprises employing low paid, low skilled, and often migrant labour can be found in supplying industries, housework, tourism and agriculture. Owner-dominated and seemingly arbitrary decisions characterise a precarious work relationship (Anderson, Citation2010). Employment control is strictly hierarchical but lacks formal structures, since formality would increase cost with an almost complete focus on work output control rather than input control. Recruiting members to the organization takes place through family or coethnic immigrant networks (Edwards & Ram, Citation2006). Flexibility is purely numerical: overtime is demanded or workers are fired. The work relationship is transactional; workers are in jobs such as these to survive on the margins of society and typically earn very low wages or piece-rate rewards (e.g. Datta et al., Citation2007). Work division and coordination are strictly hierarchical and characterised by an almost complete lack of say in employment and work practices (Felstead & Jewson, Citation1997).

Proposition 5a:

Bleak House configurations thrive on the margins of the economy or in weak states, where they are off the radar for inspection or correction and where workers have little power to change their situation.

Proposition 5b:

Presenting issues are changes in public awareness on working conditions and increased political interference in sectors with vulnerable workers. Stricter inspection can move a Bleak House configuration in various directions. Configurations with a strong output focus will turn into subcontracted networks, while some may truly improve care for workers and develop into traditional owner-managed firms.

Subcontracted networks exist when an entrepreneur wants to expand his or her business without having to deal with the hassles of tenured employees (Klaas et al., Citation2005). Subcontracted constructions include freelancing, on-demand gig work, agency work and pay rolling (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2012; Flinchbaugh et al., Citation2020; Guerci et al., Citation2015). Here there is no formal employer-employee relationship other than a contract in which a certain amount of labour (in hours or output) is exchanged for income (Flinchbaugh et al., Citation2020). By outsourcing all investments in personnel other than pay to the subcontractor, the focus of control is on work output. The configuration depicts a strictly transactional employer-worker relationship. The work relationship is hierarchical: there is a formal contract about the precise exchange conditions with a fixed term. Workers have little say beyond what is contractually agreed upon (Whitley, Citation1999). From an employer perspective, the work relationship is clear: the focus is on work output, and the subcontractor can decide who does the work and in what manner. Research finds positive effects of subcontracted labour for organizations but largely harmful effects for the workers themselves (Flinchbaugh et al., Citation2020). Employment risks are transferred to the worker, which qualifies many subcontracted constructions as “bad jobs” with high levels of job insecurity, low pay, no training, no insurance and no voice (Kalleberg et al., Citation2000; Quinlan, Citation2015).

Proposition 6a:

Transaction costs are an important motive for subcontracted networks. The rise of flexible forms of work causes an ever-increasing number of employers to move to subcontracting rather than hiring.

Proposition 6b:

Presenting issues happen at the macrolevel of politics and social security. New regulations aim to protect workers from the liabilities of flexible work arrangements, which could stop the trend towards subcontracting and bring workers back to traditional owner-managed, strategic, or knowledge entrepreneur configurations.

Alliances concern informal mutual agreements between equals to deliver an output. Such entities are not organizations in the traditional sense but social units of (generally self-employed) individuals who work together on a more or less regular basis. This configuration fits with the image of adhocracy or networked ‘organizations’ (Goffee & Scase, Citation1995; Mintzberg, Citation1979). Examples of alliances are found in labour-intensive professions such as construction or in the “alternative” not-for-profit circuit (as in a cooperative bookshop) and in the music industry (Coulson, Citation2012; Goss, Citation1991). A lack of hierarchy and formal rules defines this typology (Goffee & Scase, Citation1995). As all interaction is negotiated through social interaction, alliances have trouble achieving profitability (Goss, Citation1991). Recruiting members to the alliance occurs through a local social community of craftspeople or people with shared ideals. Individuals are committed to an alliance because it offers more security (income and continuity of work) than standalone self-employed entrepreneurship due to the presence of shared customer and knowledge networks. Individuals divide work informally in mutual negotiation, and work coordination is organized in informal meetings, where all members have a say.

Proposition 7a:

The alliance configuration is viable for recurring project work for which teamwork is essential, but the skill mix may vary from one project to the next. Individual self-employed workers find partners for a project among those with whom they collaborated before.

Proposition 7b:

A booming economy poses a presenting issue to this configuration when solo self-employed individuals notice that their peers are too busy to join. In such cases, the alliance configuration will be abandoned, and the self-employed individual strengthens control over the work relationship by offering permanent employment contracts. The configuration then develops into a craft employer.

Partnerships are formally contracted associations between equals: organizations owned by their workers often called associates or partners (Greenwood et al., Citation2007). Partnerships are common in human capital-intensive professional services such as medical and legal professions (e.g. dentistry and advocacy) and in management consulting (Levin & Tadelis, Citation2005). Less common but similar in terms of control are worker-owned and managed organizations found in a broad range of industries, including production and agriculture (Cheney et al., Citation2014). Contractual arrangements form the basis of lateral work relationships. Contracts may concern shared costs, goodwill or the amount of financial or labour input. Such contracts serve to retain and motivate partners (Cheney et al., Citation2014; Von Nordenflycht, Citation2010). Members of a partnership work as equals, and as each has an equivalent say in the organization, there is little hierarchy (Wynn, Citation2016). Recruiting members to the organization takes place through a strict selection of potential partners or co-owners by evaluating a candidate’s ability to become a partner (Greenwood et al., Citation2007; Levin & Tadelis, Citation2005). Contractual agreements function as formal controls of each partner’s contribution to the organization.

Proposition 8a:

Partnerships are the institutionalized form of business found in a few specific professions, such as surgery, consulting, and law.

Proposition 8b:

Presenting issues emerge when medical and legal professionals change work expectations. New generations object to the high investment required to become a partner and no longer aspire to the long work hours associated with a partnership, which will cause partnerships to transform into knowledge – or strategic entrepreneurs, due to the preference for formalized control that comes with the profession.

In conclusion, the typology based on control dimensions provides a theoretical lens through which to observe the phenotypes of HRM in small organizations. The approach does not replace integrative perspectives such as open systems theory (Harney & Dundon, Citation2006; Lacoursière et al., Citation2008), institutional theory (Edwards et al., Citation2006), mixed embeddedness (Edwards & Ram, Citation2006), or structuration theory (Kroon & Paauwe, Citation2014), but offers an analytical starting point from which to detect, describe, contrast, compare and contextualize empirically observed configurations of work relationships and associated HRM practices in a broad diversity of small organizations.

Discussion and future research

Research on HRM in small organizations requires a new approach to find means used to organize work in organizations that cannot be captured by questionnaires of high-performance work systems developed in the context of large organizations. The goal of this contribution is to provide a typological model of based on the control of work and work relationships in small enterprises as an alternative approach for analysing HRM. The typology can advance the development of integrative configurations that position the phenomenon of HRM in the various contexts of small organizations. This approach provides opportunities for theory building and practice as explained below.

The focus on control styles provides a lens from which to study HRM responses of new types of small organizations such as those developing in the networked economy. By including output oriented control as a style to manage work and workers, three new configurations were found to describe alternative forms of small firm HRM: alliances, subcontracted networks and partnerships. The subcontracted workforce has been largely ignored in the previous small firm employment relations literature, partly due to a focus on employment rather than work relationships. In a similar vein, the approach can bridge the small organizations and self-employed entrepreneurship literatures. This concerns the domain of microenterprises facing growth and responses to control the inherent development of work relationships to meet work demands (Baines & Robson, Citation2001). To date, alliances that develop between the self-employed are largely ignored in the HRM literature.

The approach can also bridge the small firm and family firm literatures. Similar to small organizations, family firms are not a homogeneous sector. Family ownership and family member involvement impose a challenge to the control of work and work relationships that is common to many small organizations (Combs et al., Citation2018). Again, observing the control styles could be the starting point for understanding the complex interplay between family and workers in small, family-owned and managed organizations.

The control-styles based typology can advance integrative configurations research. Such research requires methods that can assess complex, nonlinear, and synergistic effects. Set-theoretic methods that use a Boolean strategy to determine which combinations or ‘sets’ of organizational characteristics combine to result in an outcome are best suited to finding configurations (Fiss, Citation2007). Set-theoretic methods show patterns under more stable structural conditions and during events that induce change initiated by agents who behave and act within these structures (Giddens, Citation1984; Johns, Citation2006).

The first step in building an integrative configuration therefore involves using the four functional requirements to ask open-ended questions about the organization of work to representative members of an organization. For recruiting members, one could ask “how is it ensured that there are enough people to perform work?”. To ensure continuity, “what is done to ensure that these people contribute their time and effort to the organization?”. For differentiation, “how is work divided between all those working for the organization?”. Finally, for integration, one could ask “what is done to coordinate the work once tasks are divided?”. As an important advantage of this approach, it is not the sheer presence of HRM practices that matters but the intended and actual effects that these employment and work practices have with respect to meeting functional requirements (Arthur & Boyles, Citation2007). For example, training may be used to staff an organization with the right skills and competencies, but it may also serve to manage exchange relationships with workers. This phenomenon will only surface when practices are unveiled after asking about functional requirements and never when these are established as part of a checklist. In a configuration, the parts of the system make up the whole.

Open-ended questions on how functional requirements are dealt with provide observations that can be coded in terms of control dimensions. Does the organization of work relationships that appears from answers to these questions align with direct or formal control or with output or input control? Is this process hierarchical or egalitarian? provides examples of ways to find the nearest ideal type configuration. Then, asking why the functional requirements are met as they are will link the configuration to the context indicating structural contingencies, agency, and change. The descriptions of the eight types already indicate some professions and sectors wherein certain configurations are likely to occur. This search for configurational fit with organizational contingencies could be a next research avenue.

Of theoretical interest are questions concerning the relative importance of determinants and the stability and viability of configurations. The first question concerns the relative importance of determinants for the types. Determinants can be systematically compared by taking a substantive sample of small firms that operate in the same product sector and in the same labour market, mapping their configurations of control of work relations and the determinants mentioned, and systematically comparing and contrasting determinants to find which combinations or paths dominate for each type. Research on this question can provide a further theoretical understanding of the ‘why’ of determinants: what is the relative importance of previously suggested determinants such as transaction costs, labour dependence, owner imprinting and agency?

The second question addresses the stability of the configurations. Configurations have temporal stability that changes when presenting issues happen, challenging the ways in which work relationships are controlled (Harney & Alkhalaf, Citation2020). The propositions indicate that presenting issues will most likely affect one of the control dimensions and not all at the same time, making transitions to another configuration gradual and changes from one type to the opposite in the cube unlikely.

A related question concerns which dimensions of control are more robust to disruptions and whether effects are more fundamental to disruptions caused by changes to the external context (e.g. society) or to disruptions to the internal context (e.g. ownership). An additional way to capture causes for changes in control types involves process research (Langley, Citation2007), which tracks the presenting issues contributing to major shifts in organizing the control of work relationships. After an issue such as a change in ownership or declining performance emerges, the small organization will be in a state of flux with increased dynamics, which will enable sharper insight into the effects of the different determinants and the kind of agency exerted by the owner manager on the nature of and change in HRM responses. Repeated intervals of interviews could help establish chains of cause and effect and thus help clarify underlying processes.

Finally, the question of the viability of configurations in relation to the survival of small organizations is important. The business goals of small organizations are framed in terms of continuity, personal satisfaction and exceeding customer expectations rather than growth, which poses the question of whether various styles of control bring about or cause these business outcomes. This last question could facilitate consultation with small organizations. How can small business entrepreneurs better reach their goals by changing their ways of controlling work relationships in their firms?

Overall, a stronger understanding of the relative importance of determinants and of the stability and viability of control configurations for work relationships has practical implications for labour and economic policy makers, for inspection and law enforcement, for the success of small businesses and for workers whose incomes depend on them.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aldrich, H. E. (1999). Organizations evolving.

- Alvesson, M. (2000). Social identity and the problem of loyalty in knowledge-intensive companies. Journal of Management Studies, 37(8), 1101–1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00218

- Anderson, B. (2010). Migration, immigration controls and the fashioning of precarious workers. Work, Employment and Society, 24(2), 300–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017010362141

- Arthur, J. B., & Boyles, T. (2007). Validating the human resource system structure: A levels-based strategic HRM approach. Human Resource Management Review, 17(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.02.001

- Bacharach, S. B. (1989). Organizational theories: Some criteria for evaluation. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 496–515. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308374

- Baines, S., & Robson, L. (2001). Being self-employed or being enterprising? The case of creative work for the media industries. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 8(4), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006830

- Baron, J. N., Burton, D. M., & Hannan, M. T. (1996). The road taken: Origins and evolution of employment systems in emerging companies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 5, 239–276.

- Baron, J. N., Burton, M. D., & Hannan, M. T. (1999). Engineering bureaucracy: The genesis of formal policies, positions, and structures in high-technology firms. The Journal of Law, Economic and Organization, 15, 1–41.

- Barret, R. (1999). Industrial relations in small firms: The case of the Australian information industry. Employee Relations, 21, 311–323.

- Barrett, R., & Rainnie, A. (2002). What’s so special about small firms? Developing an integrated approach to analysing small firm industrial relations. Work, Employment & Society, 16(3), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/095001702762217416

- Barringer, B. R., Jones, F. F., & Neubaum, D. O. (2005). A quantitative content analysis of the characteristics of rapid-growth firms and their founders. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(5), 663–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.03.004

- Bedford, D. S., & Malmi, T. (2015). Configurations of control: An exploratory analysis. Management Accounting Research, 27, 2–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2015.04.002

- Behrends, T. (2007). Recruitment practices in small and medium size enterprises. An empirical study among knowledge-intensive professional service firms. Management Revue, 18, 55–74. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2007-1-55

- Boon, C., Den Hartog, D. N., & Lepak, D. P. (2019). A systematic review of human resource management systems and their measurement. Journal of Management, 45(6), 2498–2537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318818718

- Boxall, P., & Purcell, J. (2011). Strategy and human resource management (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

- Cappelli, P., & Keller, J. (2012). Classifying work in the new economy. Academy of Management Review, 38(4), 575–596. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0302

- Cheney, G., Santa Cruz, I., Peredo, A. M., & Nazareno, E. (2014). Worker cooperatives as an organizational alternative: Challenges, achievements and promise in business governance and ownership. Organization, 21(5), 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508414539784

- Combs, J. G., Jaskiewicz, P., Shanine, K. K., & Balkin, D. B. (2018). Making sense of HR in family firms: Antecedents, moderators, and outcomes. Human Resource Management Review, 28(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.05.001

- Coulson, S. (2012). Collaborating in a competitive world: Musicians’ working lives and understandings of entrepreneurship. Work, Employment and Society, 26(2), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017011432919

- Datta, K., McIlwaine, C., Evans, Y., Herbert, J., May, J., & Wills, J. (2007). From coping strategies to tactics: London’s low-pay economy and migrant labor. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45(2), 404–432.

- Davila, T. (2005). An exploratory study on the emergence of management control systems: Formalizing human resources in small growing firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30(3), 223–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2004.05.006

- Delery, J. E., & Doty, D. H. (1996). Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management : Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 802–835.

- Drummond, I., & Stone, I. (2007). Exploring the potential of high performance work systems in SMEs. Employee Relations, 29(2), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450710720011

- Duggan, J., Sherman, U., Carbery, R., & McDonnell, A. (2020). Algorithmic management and app-work in the gig economy: A research agenda for employment relations and HRM. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(1), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12258

- Dundon, T., Grugulis, I., & Wilkinson, A. (1999). Looking out of the black-hole’. Employee Relations, 21(3), 251–266.

- Edwards, P., & Ram, M. (2006). Surviving on the margins of the economy: Working relationships in small, low-wage firms. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 895–916.

- Edwards, P., Ram, M., Gupta, S. S., & Tsai, C. (2006). The structuring of working relationships in small firms: Towards a formal framework. Organization, 13(5), 701–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508406067010

- Etzioni, A. (1961). A comparative analysis of complex organizations: On power, involvement and their correlates. Simon and Schuster.

- Felstead, A., & Jewson, N. (1997). Researching a problematic concept: Homeworkers in Britain. Work, Employment & Society, 11(2), 327–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017097112007

- Fiss, P. C. (2007). A set-theoretic approach to organizational configurations. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1190–1198. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26586092

- Flinchbaugh, C., Zare, M., Chadwick, C., Li, P., & Essman, S. (2020). The influence of independent contractors on organizational effectiveness: A review. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.01.002

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press.

- Gill, M. J. (2019). The significance of suffering in organizations: Understanding variation in workers’ responses to multiple modes of control. Academy of Management Review, 44(2), 377–404. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0378

- Gilman, M. W., & Edwards, P. K. (2008). Testing a framework of the organization of small firms: Fast-growth, high-tech SMEs. International Small Business Journal, 26(5), 531–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242608094028

- Gilman, M., Edwards, P., Ram, M., & Arrowsmith, J. (2002). Pay determination in small firms in the UK: The case of the response to the National Minimum Wage. Industrial Relations Journal, 33(1), 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2338.00219

- Gilman, M., Raby, S., & Pyman, A. (2015). The contours of employee voice in SMEs: The importance of context. Human Resource Management Journal, 25(4), 563–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12086

- Goffee, R., & Scase, R. (1995). Corporate realities: The dynamics of large and small organizations. International Thomson Business Press.

- Goss, D. (1991). Small business and society (Vol. 82). Routledge.

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429494338

- Greenwood, R., Deephouse, D. L., & Li, S. X. (2007). Ownership and performance of professional service firms. Organization Studies, 28(2), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840606067992

- Gresov, C., & Drazin, R. (1997). Equifinality: Functional equivalence in organization design. Academy of Management Review, 22(2), 403–428.

- Grugulis, I., Dundon, T., & Wilkinson, A. (2000). Cultural control and the “culture manager”: Employment practices in a consultancy. Work, Employment & Society, 14(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170022118284

- Guerci, M., Radaelli, G., Siletti, E., Cirella, S., & Rami Shani, A. B. (2015). The impact of human resource management practices and corporate sustainability on organizational ethical climates: An employee perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(2), 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1946-1

- Gundry, L. K., & Welsch, H. P. (2001). The ambitious entrepreneur: High growth strategies of women-owned enterprises. Journal of Business Venturing, 16, 453–470.

- Harney, B., & Alkhalaf, H. (2020). A quarter-century review of HRM in small and medium-sized enterprises : Capturing what we know, exploring where we need to go. Human Resouce Management, 60, 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22010

- Harney, B., & Dundon, T. (2006). Capturing complexity: Developing an integrated approach to analysing HRM in SMEs. Human Resource Management Journal, 16(1), 48–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2006.00004.x

- Heneman, R. L., Tansky, J. W., & Camp, S. M. (2000). Human resource management practices in small and medium-sized enterprises: Unanswered questions and future research perspectives. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 25(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2007.82.4.907

- Heracleous, L., & Hendry, J. (2000). Discourse and the study of organization: Toward a structurational perspective. Human Relations, 53(10), 1251–1286. https://doi.org/10.1177/a014105

- Horak, S. (2017). The informal dimension of human resource management in Korea: Yongo, recruiting practices and career progression. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(10), 1409–1432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1089062

- Innes, P., & Wiesner, R. (2012). Beyond HRM intensity: Exploring intra-function HRM clusters in SMEs. Small Enterprise Research, 19(1), 32–51. https://doi.org/10.5172/ser.2012.19.1.32

- Jaffee, D. (2001). Organization theory: Tension and change. McGraw-Hill.

- Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context of organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/sl0551-008-9983-x

- Kalleberg, A. L., Reskin, B. F., Hudson, K. (2000). Bad jobs in America: Standard and nonstandard employment relations and job q …. American Sociological Review, 65(2), 256–278.

- Kaufman, B. E. (2010). The theoretical foundation of industrial Relations and its implications for labor economics and human resource management. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 64(1), 74–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391006400104

- Kitching, J. (2016). Between vulnerable compliance and confident ignorance : Small employers, regulatory discovery practices and external support networks. International Small Business Journal, 34(5), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615569325

- Klaas, B. S., Yang, H., Gainey, T., & Mcclendon, J. A. (2005). HR in the small business enterprise: Assessing the impact of PEO utilization. Human Resource Management, 44(4), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20083

- Kroon, B., & Paauwe, J. (2014). Structuration of precarious employment in economically constrained firms: The case of Dutch agriculture. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12024

- Lacoursière, R., Fabi, B., & Raymond, L. (2008). Configuring and contextualising HR systems : An empirical study of manufacturing SME’s. Management Revue, 19(1–2), 106–125.

- Langley, A. (2007). Process thinking in strategic organization. Strategic Organization, 5(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127007079965

- Lawrence, P. R., & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Organization and environment: Managing differentiation and integration, Harvard Business School Press.

- Levin, J., & Tadelis, S. (2005). Profit sharing and the role of professional partnerships. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(1), 131–171. https://doi.org/10.1162/0033553053327506

- Marchington, M., Carroll, M., & Boxall, P. (2003). Labour scarcity and the survival of small firms: A resource-based view of the road haulage industry. Human Resource Management Journal, 13(4), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2003.tb00102.x

- Marlow, S. (2002). Regulating labour management in small firms. Human Resource Management Journal, 12(3), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2002.tb00069.x

- Marlow, S., & Patton, D. (2002). Minding the gap between employers and employees: The challenge for owner-managers of smaller manufacturing firms. Employee Relations, 24(5), 523–539. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450210443294

- Merchant, K. A. (1985). Control in business organizations, Pitman.

- Mihail, D. M. (2004). Labour flexibility in Greek SMEs. Personnel Review, 33(5), 549–560. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480410550152

- Miller, D. (1987). Strategy making and structure: Analysis and implications for performance. Academy of Management Journal, 30(1), 7–32. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=4324172&site=ehost-live

- Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations, Pearson Education.

- Nadin, S., & Cassell, C. (2007). New deal for old? Exploring the psychological contract in a small firm environment. International Small Business Journal, 25(4), 417–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242607078587

- Ouchi, W. G. (1979). A conceptual framework for the design of organizational control mechanisms. Management Science, 25(9), 833–848. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.25.9.833

- Paauwe, J., & Farndale, E. (2017). Strategy, HRM, and performance: A contextual approach. Oxford University Press.

- Patel, P. C., & Cardon, M. S. (2010). Adopting HRM practices and their effectiveness in small firms facing product-market competition. Human Resource Management, 49(2), 267–292. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20346

- Quinlan, M. (2015). The effects of non-standard forms of employment on worker health and safety. Conditions of Work and Employment Series. ILO. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3934.4400

- Rainnie, A. (1985). Is small beautiful? Industrial relations in small clothing firms. Sociology, 19(2), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038585019002005

- Rainnie, A. (1989). Industrial relations in small firms: Small isn’t beautiful. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315563541

- Ram, M. (1991). Control and autonomy in small firms: The case of the West Midlands clothing industry. Work, Employment & Society, 5(4), 601–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017091005004007

- Ram, M. (1999). Managing autonomy: Employment relations in small professional service firms. International Small Business Journal, 17(2), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242699172001

- Ram, M., & Holliday, R. (1993). Relative merits: Family culture and kinship in small firms. Sociology, 27(4), 629–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038593027004005

- Ram, M., Edwards, P., & Jones, T. (2007). Staying underground: Informal work, small firms, and employment regulation in the United Kingdom. Work and Occupations, 34(3), 318–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888407303223

- Ram, M., Edwards, P., Gilman, M., & Arrowsmith, J. (2001). The dynamics of informality: Employment relations in small firms and the effects of regulatory change. Work, Employment & Society, 15(4), 845–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/095001701400438233

- Rauch, A., & Hatak, I. (2016). A meta-analysis of different HR-enhancing practices and performance of small and medium sized firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(5), 485–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.05.005

- Reijonen, H., & Komppula, R. (2007). Perception of success and its effect on small firm performance. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 14(4), 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000710832776

- Scase, R. (2003). Employment relations in small firms. In P. Edwards (Ed.), Industrial relations: Theory and practice (pp. 470–488), Wiley.

- Scott, W. R., & Davis, G. F. (2015). Organizations and organizing: Rational, natural and open systems perspectives. Routledge.

- Senftlechner, D., & Hiebl, M. R. W. (2015). Management accounting and management control in family businesses: Past accomplishments and future opportunities. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 11(4), 573–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-08-2013-0068

- Sheppeck, M. A., & Militello, J. (2000). Strategic HR configurations and organizational performance. Human Resource Management, 39(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-050X(200021)39:1 < 5::AID-HRM2 > 3.0.CO;2-I

- Short, J. C., Payne, G. T., & Ketchen, D. J. J. (2008). Research on organizational configurations: Past accomplishments and future challenges. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1053–1079.

- Snell, S. A. (2011). Control theory in strategic human resource management: The mediating effect of administrative information. The Academy of Management Journal, 35(2), 292–327.

- Storey, J. (1985). Management control as a bridging concept. Journal of Management Studies, 22(3), 269–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1985.tb00076.x

- Von Nordenflycht, A. (2010). What is a professional service firm? Toward a theory and taxonomy of knowledge-intensive firms. Academy of Management Review, 35(1), 155–174. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2010.45577926

- Weick, K. E. (1989). Theory construction as disciplined imagination. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 516–531. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308376

- Whitley, R. (1999). Firms, institutions and management control: The comparative analysis of coordination and control systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 24(5–6), 507–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(97)00030-5

- Whittington, R. (1992). Putting Giddens into action: Social systems and managerial agency. Journal of Management Studies, 29(6), 693–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1992.tb00685.x

- Wynn, M. T. (2016). Chameleons at large: Entrepreneurs, employees and firms-the changing context of employment relationships. Journal of Management and Organization, 22(6), 826–842. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.40