Abstract

The present study develops and tests an overreaching theoretical framework based on social exchange theory to examine the situations under which individuals with high levels of psychological entitlement are more or less likely to exhibit positive work attitudes and behaviors. In particular, we integrate perspectives from the team climate literature to analyze the moderating effects of employee involvement climate at the workgroup level on the relationship between psychological entitlement and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) through the mediating mechanism of affective commitment (a first-stage moderated mediation model). To test our hypotheses, we collected data from 231 supervisor-subordinate dyads across 41 work teams at a large Chinese automobile manufacturer. We find that when the employee involvement climate level is high, the effects of psychological entitlement on OCBs through affective commitment are positive and significant. In contrast, when the employee involvement climate level is low, the relationship is negative and significant. The present study makes a theoretical contribution to the literature by examining the frequently neglected positive side of psychological entitlement. It demonstrates that a high employee involvement climate helps to engage psychologically entitled employees by circumventing previously unbalanced social exchange relationships. We also discuss the practical implications of our findings and provide suggestions for human resource managers to maximize the contributions of entitled employees and foster their organizational commitment and OCBs.

Introduction

In the contemporary workplace, managers increasingly have to deal with psychologically entitled employees, i.e. those who consistently believe that they deserve preferential treatment irrespective of their actual performance (Campbell et al., Citation2004; Lee et al., Citation2019; O’Leary-Kelly et al., Citation2017). Prior research points out that psychological entitlement is a real problem for organizations and calls on both scholars and practitioners to pay more attention to this issue and develop adequate human resource (HR) policies to effectively manage employees with high levels of psychological entitlement (Fisk, Citation2010; Harvey & Martinko, Citation2009). Over the last decade, researchers have consistently found evidence that psychological entitlement exerts negative effects in the workplace (Loi et al., Citation2020; Neville & Fisk, Citation2019; Wheeler et al., Citation2013). For example, psychologically entitled individuals have been found to be more likely to abuse others and engage in political behaviors at work (Eissa & Lester, Citation2021; Harvey & Harris, Citation2010; Whitman et al., Citation2013) and are less likely to reciprocate positive treatment (Westerlaken et al., Citation2016).

In explaining the negative effects of psychological entitlement, researchers have argued that individuals high in entitlement have a biased view of social exchange and tend to desire more out of relationships than they put in (Naumann et al., Citation2002; Snow et al., Citation2001). However, a number of studies have reported conflicting findings on this point. For example, Brummel and Parker (Citation2015) found a non-significant relationship between psychological entitlement with organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) directed toward the organization, and a marginally significant positive relationship with OCBs directed toward individuals. Similarly, Taylor (Citation2013) found a non-significant relationship between psychological entitlement and OCBs. These results suggest that there may be situations under which psychologically entitled individuals may be more or less likely to engage in positive attitudes and behaviors at work. However, there has been limited research examining the boundary conditions of the link between psychological entitlement and work outcomes.

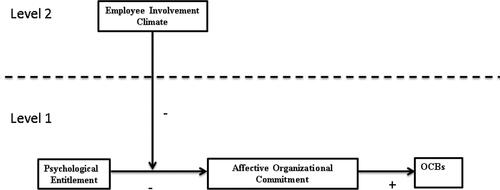

To address this gap in the literature, the present study develops and tests a theoretical framework based on social exchange theory to examine situations under which psychological entitlement is likely to exert a positive or negative influence on employees’ work attitudes and behaviors. Social exchange theory suggests that when treated well by their organization, employees develop positive work attitudes and reciprocate in the form of positive work behaviors. We develop a moderated mediation model in which psychological entitlement is the independent variable, affective organizational commitment captures work attitudes as the mediator, OCBs capture work behaviors as the dependent variable, and employee involvement climate at the workgroup level captures the extent to which the organization involves employees in decision-making as the moderator (Smith et al., Citation2018). We choose to focus on affective organizational commitment as the mediating variable in our theoretical model, as it has been shown to predict OCBs more strongly than other dimensions of commitment (Cetin et al., Citation2015; Organ & Ryan, Citation1995), and captures the social exchange processes that occur when employees decide to reciprocate their organization’s positive treatment (Lavelle et al., Citation2007).

In this study, we examine employee involvement climate at the workgroup level as a moderator, as through signaling to employees that the organization is involving them in decision-making and valuing them as an important member of the organization, a climate of high involvement in the workgroup highlights to employees that the organization is upholding their part of the psychological contract with the employee (Schreurs et al., Citation2013). A strong employee involvement climate is a work environment in which all workgroup members feel they can work autonomously, have access to important work-related information, and influence decisions made within the workgroup (Richardson & Vandenberg, Citation2005; Wallace et al., Citation2016). Integrating perspectives from the team climate literature (Anderson & West, Citation1998) into our overreaching model based on social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964), we argue that when working in a climate where there are high levels of employee involvement in the workgroup, entitled employees are more likely to engage in positive work attitudes and behaviors than when working in a climate where there are low levels of employee involvement. However, when working in a climate of low employee involvement, individuals with high levels of psychological entitlement will be more likely than those with low levels of psychological entitlement to perceive their expectations of the organization in terms of the social exchange relationship are not being met. This will lead them to feel less committed to the organization and, subsequently, less motivated to engage in OCBs. In summary, we propose that the employee involvement climate at the workgroup level moderates the effects of psychological entitlement on OCBs through the mediating mechanism of affective organizational commitment. The proposed theoretical model for this study is shown in .

In examining these issues, our research makes three key contributions. First, our study makes a theoretical contribution by examining the usually neglected positive side of psychological entitlement. More specifically, we show that employees with high levels of psychological entitlement can exhibit positive work attitudes and behaviors, such as affective commitment and OCBs that benefit the organization under the right conditions. Second, our study demonstrates that the extent to which entitled employees engage in positive social exchange processes depends on the employee involvement climate at the workgroup level. In doing so, we contribute to the employee involvement literature by showing how climates at the workgroup level differentially impact individuals with varying degrees of psychological entitlement and by demonstrating that a high employee involvement climate can engage psychologically entitled employees by circumventing previously unbalanced social exchange relationships. Third, our study makes an important practical contribution by highlighting the implications for managing employees with high levels of psychological entitlement.

Theory and hypothesis development

Psychological entitlement

According to Campbell and colleagues (2004, p. 31), psychological entitlement refers to ‘a stable and pervasive sense that one deserves more and is entitled to more than others’. It is associated with inflated self-perceptions that are often not seen by third parties as being objectively justifiable (Harvey & Harris, Citation2010). The term ‘psychological’ entitlement has been used to distinguish it from other conceptualizations of entitlement, such as economic entitlement (e.g. payments owed in exchange for the provision of goods or services; Harvey & Dasborough, Citation2015). Prior research suggests that entitlement often results from a social contract between an individual and another entity in which the individual feels entitled to certain outcomes due to their participation in a social relationship with that entity (e.g. an employee of a business organization; Naumann et al., Citation2002). Employees with high levels of psychological entitlement tend to have favorable self-perceptions and feel they deserve high levels of praise and rewards, irrespective of their actual performance (Harvey & Harris, Citation2010).

Although researchers have highlighted overlaps between psychological entitlement and other traits such as narcissism, there are important conceptual and empirical distinctions between these two concepts. For example, Rose and Anastasio (Citation2014) argue that for one to experience entitlement, the inflation of one’s sense of self is contingent on the treatment received in relation to others, whereas narcissism inflates self-importance regardless of others (see also Lee et al., Citation2019; Treadway et al., Citation2019). Empirically, researchers have also shown that psychological entitlement can exist independently of other key narcissism traits, including assertiveness, deceitfulness, and exploitativeness (Campbell et al., Citation2004; Harvey & Dasborough, Citation2015; Miller et al., Citation2012).

A small but growing body of research has documented the links between psychological entitlement and work outcomes within an organizational context (Lee et al., Citation2019). As highlighted in Harvey and Dasborough (Citation2015) review article, most research on psychological entitlement at work has examined its links with undesirable work outcomes (see also Loi et al., Citation2020; Neville & Fisk, Citation2019). For example, consistent with affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, Citation1996) and attribution theory, Harvey and Harris (Citation2010) found a positive association between entitlement and job frustration, which in turn engendered coworker abuse and political behaviors. Harvey et al. (Citation2014) also found that, in contrast to less entitled employees, more entitled employees were more likely to perceive their supervisor as abusive and retaliate with deviant behaviors.

Employee involvement climate within workgroups

The conditions under which employees actively contribute to an organization beyond their role requirements are increasingly important to scholars and managers (Marchington & Kynighou, Citation2012). This is because extra-role behaviors such as OCBs are positively associated with task performance, organizational productivity, efficiency, and customer satisfaction (Hoffman et al., Citation2007; Podsakoff et al., Citation2009). In their study on servant leadership, Walumbwa et al. (Citation2010) found that the group-level mechanism of organizational climate moderated the differences between employee characteristics and employee OCBs. This indicates that the organizational climate influences how employees perceive their organization as well as their behaviors toward the organization (Kuenzi & Schminke, Citation2009; Marchington & Kynighou, Citation2012).

One type of climate that has been shown to foster positive employee outcomes is an employee involvement climate (Smith et al., Citation2018; Wallace et al., Citation2016). Employee involvement has typically been modeled as a climate in which organizational members perceive particular characteristics of the work environment in the same way (Richardson & Vandenberg, Citation2005; Riordan et al., Citation2005). Building on work that has measured the involvement climate at the organizational level (Lawler, Citation1996), recent research has begun to conceptualize and measure the effects of employee involvement climate at the workgroup level (Richardson & Vandenberg, Citation2005; Wallace et al., Citation2016). An employee involvement climate exists within a workgroup when members of the workgroup mutually understand that they (1) have the power to act and make decisions about issues that affect them in the workgroup, (2) have the information and knowledge to make such decisions, and (3) are rewarded for making decisions that improve their workgroup’s effectiveness (Richardson & Vandenberg, Citation2005; Wallace et al., Citation2016). A strong employee involvement climate is a work environment in which all workgroup members feel they can work autonomously, have access to information, and influence decisions made within the workgroup (Schreurs et al., Citation2013).

Because climates are socially constructed indicators of desired behavior within an organization or workgroup, they originate from the organization’s policies and procedures, and are reinforced by managers who recognize and directly react to employee behavior to socialize employees into the organizational climate (Zohan & Luria, Citation2005). Therefore, strategic HR management can be utilized to foster a high-involvement climate. As highlighted by Wallace and colleagues (2016), involvement climates are generally stronger at lower organizational levels because supervisors can closely direct and influence employee involvement within a workgroup (Richardson & Vandenberg, Citation2005). As such, the immediate supervisor plays an integral role in forming the workgroup’s involvement climate, while HR managers play an important role in developing the organizational culture and reinforcing this culture through policies and procedures.

Moderating influence of employee involvement climate

As has been noted, prior work suggests individuals with high levels of psychological entitlement may, in certain circumstances, display negative attitudes and behaviors at work because they tend to be more demanding in their social exchange relationship with their employer than those with low psychological entitlement. However, the situations in which those with high levels of psychological entitlement may respond more positively have rarely been examined.

In the current study, we argue that an employee involvement climate at the workgroup level moderates the relationship between psychological entitlement and OCBs through the mediating mechanism of affective organizational commitment. In doing so, we integrate principles from the literature on team climate (Anderson & West, Citation1998) with social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964), which states that employees exhibit more positive work attitudes and behaviors toward the organization when they feel that their expectations of their social exchange relationship with the organization have been met (e.g. Miao et al., Citation2013). We choose to focus specifically on affective organizational commitment, defined as an individual’s identification with and emotional attachment to an organization (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990), as the mediating mechanism linking psychological entitlement to OCBs, since among work attitudes, affective organizational commitment has been shown to be the strongest predictor of OCBs and to explain the process through which an employee reciprocates the extent to which an employer meets its obligations under the psychological contract (Lavelle et al., Citation2007).

We argue that employees with high levels of psychological entitlement are typically more demanding in their social exchange relationships with the organization (Naumann et al., Citation2002) and more likely to respond negatively when they are not provided with opportunities for being involved in decision-making in their workgroup. In contrast, we argue they respond in a more positive manner when they believe that the organization has upheld its side of the psychological contract by involving employees in decision-making processes. In other words, we expect that under a team climate characterized by a high level of employee involvement, where employees are provided with the opportunity to access relevant information and knowledge, apply it to make decisions that will influence their workgroup, and are incentivized with rewards to improve workgroup efficiency (Richardson & Vandenberg, Citation2005; Wallace et al., Citation2016), individuals high in psychological entitlement will have a less biased view of the social exchange relationship with the organization and respond in the form of desired work attitudes and behaviors than under a team climate characterized by low levels of employee involvement. In summary, we argue that a team climate characterized by a high level of employee involvement will adjust the reciprocity norm in such a way that those with high levels of psychological entitlement will feel that their needs under their psychological contract are being met, and lead them to reciprocate in the form of greater commitment to the organization, and in turn OCBs that may benefit the organization. The provision of opportunities to participate in decision-making may tap into highly entitled individuals’ self-inflated ego and their innate need to promote themselves to others (Giacalone, Citation1985; Harvey & Harris, Citation2010). In contrast, under a climate characterized by a low level of employee involvement, where there is limited opportunity to gain access to information and knowledge and apply it to make decisions that will influence their workgroup, employees with high levels of psychological entitlement will react in a more negative manner than those with low levels of entitlement, by limiting the extent to which they feel committed to the organization and engage in OCBs.

We first hypothesize that an employee involvement climate will moderate the link between psychological entitlement and affective organizational commitment, the mediator in our overreaching model based on social exchange theory. Although prior work has not examined whether an employee involvement climate moderates the link between psychological entitlement and affective organizational commitment, there is empirical evidence that the employee involvement climate may reduce the negative effects of low pay-level satisfaction on affective commitment (Schreurs et al., Citation2013), suggesting that an employee involvement climate influences employee perceptions that the organization is investing in the social exchange relationship between the two parties. Based on the above discussion, the following Hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Employee involvement climate will strengthen the relationship between psychological entitlement and affective organizational commitment in such a way that psychological entitlement is positively related to affective organizational commitment under high levels of employee involvement climate and negatively related under low levels of employee involvement climate.

Second, we hypothesize that an employee involvement climate will moderate the mediated relationship between psychological entitlement and OCBs through affective organizational commitment, in such a way that the indirect effect of psychological entitlement on OCBs through organizational commitment will be positive under high levels of employee involvement and negative under low levels of employee involvement. As highlighted earlier, affective organizational commitment is viewed as a mediator capturing the social exchange processes that explain why employees engage in OCBs that benefit the organization. More specifically, integrating perspectives from the team climate literature (Anderson & West, Citation1998) into our overreaching model based on social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964), we propose that when employees work in a climate characterized by high levels of employee involvement, they are likely to feel the organization is investing in the social exchange relationship and that their demands are being met because they are provided with the power to act and make decisions, the information and knowledge to make such decisions, and are rewarded for making such decisions. This subsequently leads employees to reciprocate by exhibiting high levels of organizational commitment, and in turn, engage in OCBs that will benefit the organization. As stated above, we expect individuals high in psychological entitlement to respond more positively than those low in psychological entitlement to a strong employee involvement climate, as the provision of opportunities to participate in decision-making may tap into their self-inflated ego and their innate need to promote themselves to others (Giacalone, Citation1985; Harvey & Harris, Citation2010).

There is growing evidence that affective organizational commitment strongly predicts extra-role behaviors such as OCBs because committed employees reciprocate the organization’s positive treatment (Lavelle et al., Citation2007; Meyer et al., Citation2002) and that positive organizational climates lead employees to engage in positive work behaviors by enhancing their organizational commitment (Suliman, Citation2002). Although prior research has found a strong relationship between an employee involvement climate at the workgroup level and workgroup OCBs (Richardson & Vandenberg, Citation2005), researchers have not yet examined whether an employee involvement climate at the workgroup level moderates the link between certain personality traits and the work behaviors of employees and the mediating mechanisms that underlie its transition. The above discussion leads us to the following Hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Employee involvement climate will moderate the first stage of the indirect relationship between psychological entitlement and OCBs via affective organizational commitment in such a way that the indirect effect is positive under high levels of employee involvement climate and negative under low levels of employee involvement climate.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Data were obtained from 231 supervisor-subordinate dyads across 41 teams at a large Chinese automobile manufacturer in Zhejiang Province. One unique supervisor managed each team. Data were collected from two different sources (supervisors and their immediate subordinates). Prior to distribution of the surveys, these were translated into Chinese from English by bilingual members of the research team using a back-translation procedure (Brislin, Citation1993).

We collected two waves of data from the subordinates and one wave of data from their supervisors to minimize common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). At Time 1, subordinates rated their psychological entitlement, the employee involvement climate in their workgroup, and provided their demographic data. Of the 310 contacted subordinates, 279 returned surveys directly to a member of the research team (response rate = 89.35%). At Time 2, one month later, 269 of the 279 subordinates who answered the first questionnaire rated their affective organizational commitment, yielding a response rate of 97.11%. We obtained questionnaires from 63 supervisors whose subordinates responded to the first two waves of the study (response rate = 98.44%) two months after the initial subordinate survey. These supervisors rated their subordinates’ OCBs directed toward the organization.

We achieved high response rates because the organization’s management endorsed our study. In the data collection process, prospective respondents were assured that their responses would be kept confidential and were informed of the voluntary nature of participation. All questionnaires were coded to enable the research team to match the responses of subordinates to the responses of their supervisors.

We removed 22 teams with fewer than three respondents for methodological reasons because the sample size per group can limit the power and reliability of random coefficients estimated at level 2 (Snijders, Citation2005). We performed t-tests to compare the means of all main study variables (psychological entitlement, affective organizational commitment, employee involvement climate, and OCBs) and found no statistically significant differences between the removed and remaining respondents.

Our final sample comprised 231 employees from 41 work teams. The average team size was 5.63, with a standard deviation of 2.58, ranging from 3 to 12. The average age of the employees was 33.15, with a standard deviation of 9.38. Male employees accounted for 62.3%, and 18.6% had received a bachelor’s degree or above. The average organizational tenure was 5.75 years, with a standard deviation of 5.41 years.

Measures

Participants were required to rate each questionnaire item on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Psychological entitlement

The 9-item entitlement measure developed by Campbell et al. (Citation2004) was used to measure psychological entitlement. Sample items included ‘I feel entitled to more of everything’ and ‘Great things should come to me’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .92.

Affective organizational commitment

Affective organizational commitment was measured using the 6-item scale developed by Meyer et al. (Citation1993). Sample items included ‘My organization has a great deal of personal meaning to me’ and ‘I really feel as if my organization’s problems are my own’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .84.

Organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs)

OCBs were measured using the Lee and Allen (Citation2002) scale to capture OCBs directed towards the organization. Sample items included ‘He/she defends the organization when other employees criticize it’ and ‘He/she shows pride when representing the organization in public’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .88.

Employee involvement climate

The workgroup’s employee involvement climate was measured using the 8-item measure developed by Richardson and Vandenberg (Citation2005). Sample items included ‘My workgroup is given enough authority to act and make decisions about our work’ and ‘There is a strong link between how well members of my workgroup perform their jobs and the likelihood of their receiving recognition and praise’. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .83. Because team members each provided their ratings for the employee involvement climate, we performed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to calculate between and within team variance. The ICC(1) was .24, and ICC(2) was .67 (Bliese, Citation1998). Additionally, we calculated the interrater agreement coefficient (i.e. rwg; James et al., Citation1993) to analyze whether team members’ ratings of the employee involvement climate were consistent within teams. The median rwg value across eight items was .95, suggesting that the team members rated the employee involvement climate consistently within their teams.

Control variables

As prior research has found that the age and tenure of employees influence their OCBs, we controlled for both variables in our analysis (Newman et al., Citation2017). We also controlled for gender, as previous studies have shown that gender correlates significantly with psychological entitlement (Hochwarter et al., Citation2010). Gender was measured as a dummy variable (0 = female and 1 = male), while age and tenure were measured as continuous variables using the number of years. We also controlled for whether the employee was in a managerial or non-managerial position with a dummy variable because this may influence their position in the employee involvement climate (0 = non-manager, 1 = manager). At the team level, we also controlled for team size.

Analytical strategy

Because the individual-level responses in our study were nested within teams, we performed a one-way ANOVA to examine whether substantial variability exists among key dependent variables that should be specifically modeled. The results showed that the ratings of OCBs were not independent across teams, ICC(1) = .60, Focb (40, 230) = 9.40, p < .01. Therefore, we estimated a multilevel model in which individuals are nested in their corresponding teams.

We followed Bauer et al. (Citation2006) approach to simultaneously test the cross-level interaction (H1) and multilevel moderated mediation (H2) hypotheses using Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2012). Therefore, a 1-1-1 mediation model with a Level-2 moderator was specified using robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimation (Muthén & Asparouhov, Citation2012). This model estimated the random intercepts of affective commitment and OCBs, as well as the random slope of psychological entitlement and affective commitment. Control variables such as gender and tenure were entered only at the within-group level. Employee involvement climate was only entered at the between-group level. The MODEL CONSTRAINT command was used to estimate and bootstrap confidence intervals for the conditional indirect effects.

Results

Descriptive statistics, including the means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alpha, and correlations among the study and control variables at the individual level are presented in . The correlation between employee involvement climate and team size at the team level was .32 (p < .05) with a team-level sample size of 41.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Prior to Hypothesis testing, we assessed the discriminant validity of the measures using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Because three study variables (psychological entitlement, organizational commitment, and OCBs) were at the individual level, we first specified a single-level three-factor CFA model in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2012) by loading scale items to the corresponding latent variables. In addition, we freely estimated the correlations among the latent variables. This three-factor structure (see ) provided a good fit to the data, χ2 (227, N = 231) = 448.30, p < .01, comparative fit index (CFI) = .91, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .07, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .06, goodness of fit index (GFI) = .84, Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI) = .84, and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = .90. All factor loadings of the indicators on the respective latent variables were significant. The composite reliabilities (CR) for psychological entitlement, organizational commitment, and OCBs were .91, .85 and .88, respectively, while the average variance extracted (AVE) were .56, .48, and .48, respectively. Additionally, we specified a one-factor CFA model in which all three scale items were loaded to a single latent variable. This model’s fit to the data was much worse, χ2 (230, N = 231) = 1647.21, p < .01, CFI = .45, RMSEA = .16, SRMR = .19. Furthermore, we specified three two-factor CFA models that respectively combined affective organizational commitment and OCBs, affective commitment and psychological entitlement, and psychological entitlement and OCBs into one factor and allowed the rest of the items to load onto their respective latent factors. The fit indices of the three two-factor models are listed in . All three models fit the data worse than the three-factor model. Finally, given the multilevel nature of the model, we performed a multilevel CFA on the three individual-level constructs (psychological entitlement, affective organizational commitment, and OCBs) and an additional group-level construct (employee involvement climate). A multilevel CFA is effective for determining whether the latent constructs are consistent with their theoretically implied levels of analysis after accounting for measurement errors at both levels (Grizzle et al., Citation2009). We specified a four-factor multilevel CFA model by loading items to four latent constructs to their corresponding theoretically implied levels. The fit of this model to the data was good, χ2 (Nbetween=41, Nwithin= 247) = 501.16, p < .01, CFI = .91, TLI = .89, RMSEA = .06, SRMR for within = .06, and SRMR for between = .10. The CR and AVE for the employee involvement climate at the group level were .82 and .36, respectively.

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results.

Hypothesis tests

Hypothesis 1 suggests that an employee involvement climate at the workgroup level moderates the relationship between psychological entitlement and affective commitment in such a way that the relationship is positive under high levels of employee involvement climate, and negative under low levels of employee involvement climate. presents the summary statistics of the cross-level moderation analysis.

Table 3. Hierarchical multilevel modeling results of the cross-level moderation of team involvement climate in the relationship between psychological entitlement and organizational commitment.

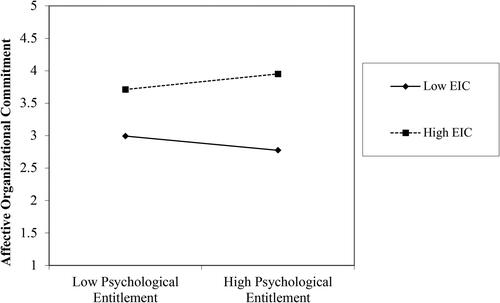

We first estimated the random slope of psychological entitlement on affective commitment. Employee involvement climate at the workgroup level was used to predict the random slope of psychological entitlement on affective commitment at level 2. We also allowed the random intercept of the mediator (affective commitment) to covary with the random slope at the between level. The results showed that the path estimate of the employee involvement climate significantly predicted the random slope of psychological entitlement and affective commitment (Estimate = .53, S.E. = .15, p < .01). Following Aiken and West (Citation1991) recommendations, we plotted this interaction at different levels of employee involvement climate (one standard deviation above and below the mean) and present the results in . In addition, we performed simple slope tests on the interaction effect. Under a high level of employee involvement climate, the simple slope was .13 (p < .05) and significant. Under a low level of employee involvement climate, the simple slope was −.16 (p < .10) and marginally significant. Similarly, shows the negative effect of psychological entitlement at low levels of employee involvement climate, as well as the positive effect of psychological entitlement at high levels of employee involvement climate. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

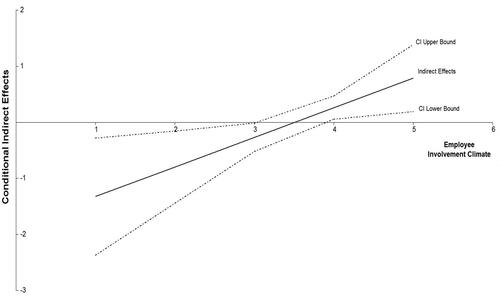

Hypothesis 2 predicts that affective organizational commitment mediates the relationship between psychological entitlement and OCBs, and such a mediation effect will vary under different conditions of employee involvement climate. To construct this multilevel path model, we first estimated the random slope of psychological entitlement on affective commitment at level 1. OCBs were regressed on affective commitment at level 1. At level 2, the random slope was regressed on employee involvement climate, and the random intercept of affective commitment was also regressed on employee involvement climate. Moreover, we allowed the between-level variance of affective commitment, OCBs, and the random slope to covary at the between level. To test this Hypothesis, we used the MODEL CONSTRAINT command to estimate the product term of two path coefficients (psychological entitlement to affective commitment and affective commitment to OCBs) and constructed 95% confidence intervals under high and low levels of employee involvement climate (one and two standard deviations above and below the mean). presents the results for the conditional indirect effects.

Table 4. Cross-level moderated mediation analysis results.

The indirect effect was negative under low levels of employee involvement climate (Estimate = −.03, S.E = .02, p < .10) and become positive under high levels of employee involvement climate (Estimate = .03, S.E. = .01, p < .05). It is worth noting that the indirect effects were not significant until we specified the level of moderators as two standard deviations above and below the mean. It could be that the empirical standard deviation of the employee involvement climate was too small to demonstrate the effect. To investigate at what conditional values of the moderator the indirect effects would become significant, we used the Johnson-Neyman technique referred to in Preacher et al. (Citation2007). With this strategy, our goal was to obtain a region of significant values or confidence bands where the null Hypothesis could be rejected at a significance level of .05. Specifically, we plotted the indirect effects of psychological entitlement to OCBs via affective commitment across different values of team employee involvement climate on a scale of 1 to 5 using the PLOT and LOOP functions in MPlus 7. shows that when the employee involvement climate was above 3.5, the indirect effects (i.e. the solid line) changed from negative to positive values. In addition, the dotted bands represent the 95% confidence interval associated with the indirect effect at any given value of the moderator from 1 to 5. This graph shows that the positive indirect effect becomes significant when the value of the moderator is greater than 3.9, and the negative indirect effect becomes significant when the value of the moderator is smaller than 3. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to identify how organizations can manage psychologically entitled employees to foster their affective organizational commitment and OCBs. Integrating perspectives from the literature on team climate (Anderson & West, Citation1998) with social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964), we found that employees’ psychological entitlement has a positive effect on their affective organizational commitment when the employee involvement climate is high and a negative effect when it is low. We also found that psychological entitlement has a positive effect on OCBs by heightening affective organizational commitment when the employee involvement climate in their workgroup is high. In contrast, when the employee involvement climate in the workgroup is low, psychological entitlement was found to have a negative effect on OCBs by reducing affective organizational commitment. We discuss the theoretical and practical implications of this research in the following sections.

Theoretical implications

By examining the moderating effects of an employee involvement climate at the workgroup level on the relationship between psychological entitlement and work outcomes, our study makes several important contributions to the literature. First, by examining the employee involvement climate at the workgroup level as a boundary condition of the relationship between psychological entitlement and OCBs through the mediating mechanism of affective organizational commitment, our study makes an important contribution to the psychological entitlement literature, which, to date, has revealed inconsistent findings regarding the influence of psychological entitlement on positive work attitudes and behaviors (Brummel & Parker, Citation2015; Taylor, Citation2013). We make a theoretical contribution by integrating perspectives from the literatures on team climate (Anderson & West, Citation1998) and social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964) to examine the situations under which psychological entitlement engenders positive social exchange processes among individuals with high levels of entitlement.

In particular, we extend our understanding of social exchange theory by pinpointing the team climates that exert greater influence on the work attitudes and behaviors of employees with high levels of psychological entitlement than those with low levels of entitlement. We demonstrate that although employees with high levels of entitlement tend to be more demanding in their social exchange relationships with their organizations and are more likely to respond negatively when they are not provided with opportunities for being involved in decision-making in their workgroup, our study also shows that they might have a less biased view of the social exchange relationship with the organization when provided with such opportunities. In fact, we found that they respond more positively than those low in entitlement when the employee involvement climate is high. These findings suggest that in a workgroup with a high involvement climate, employees with high levels of psychological entitlement might actually be more loyal as the organization invests in the social exchange relationship and meets their psychological needs, and even lead them to contribute more positively than those with low levels of psychological entitlement. This might be due to the fact that the provision of opportunities to engage in decision-making fosters exchange processes by tapping into the self-inflated egos of those high in psychological entitlement and their innate need to promote themselves to others (Giacalone, Citation1985; Harvey & Harris, Citation2010). In revealing such findings, our study is one of the first to demonstrate the positive side of psychological entitlement.

Our study also contributes to the literature on employee involvement (Marchington & Kynighou, Citation2012). Although there is growing research that analyzes the direct effects of an employee involvement climate as a workgroup level variable, which captures employees’ shared perceptions of involvement practices on employee performance and OCBs (Smith et al., Citation2018), this is one of the first studies to examine how it interacts with individual traits to predict employee work outcomes. Our results show that involvement-oriented climates that communicate to employees that their opinions, know-how, and perspectives count at work can reduce the potentially detrimental effects of high psychological entitlement. In particular, our study shows that individuals with a biased view of social exchange (i.e. those high in psychological entitlement) may actually respond more positively in a high-involvement climate (Lawler, Citation1996; Richardson & Vandenberg, Citation2005). In other words, this study shows that an employee involvement climate can adjust the reciprocity norm for those with high levels of psychological entitlement by thwarting their excessive expectations and make them more likely to reciprocate in the form of positive work attitudes and behaviors.

Practical implications

In practical terms, our study is among the first to show how organizations can effectively manage employees with high levels of psychological entitlement. More specifically, our findings suggest that to elicit high levels of commitment and OCBs from entitled employees, managers should instill climates of high employee involvement in their workgroups, establishing norms of support, autonomy, and cooperation by providing power, information, rewards, and knowledge to members of their workgroups (Wallace et al., Citation2016).

Our findings suggest it is not necessary for HR managers to screen out highly entitled employees during the selection process, as suggested in previous research (Harvey & Martinko, Citation2009; Wheeler et al., Citation2013). Our research indicates that individuals with high levels of psychological entitlement can be harnessed to deliver positive outcomes for organizations. However, it is important to assess entitlement levels during the selection and socialization processes to ensure entitled employees are placed under managers who have been shown to possess the ability to foster high levels of employee involvement in their workgroups, through participatory management styles (Brown & Cregan, Citation2008).

When developing employee involvement climates, the types of information made available to employees should be chosen carefully. For example, the information-sharing aspect of an employee involvement climate has been shown to exacerbate pay dissatisfaction (Schreurs et al., Citation2013), which may be even higher for psychologically entitled employees who view themselves as more deserving of praise and rewards than their peers. Schreurs and colleagues (2013) also found involvement in decision-making reduces dissatisfaction resulting from lower pay. Therefore, HR managers should focus on involving psychologically entitled employees in the decision-making process when implementing employee involvement climates.

Finally, this research improves our understanding of how the psychological contract is viewed by psychologically entitled employees and, thus, where managers should allocate their resources to maximize the contribution of entitled employees. Employee involvement climates are likely to deliver higher returns on investment than providing more expensive financial benefits to psychologically entitled employees by simultaneously improving employee attitudes and performance (Bosak et al., Citation2017), which might align the interests of entitled employees with those of the organization.

Limitations and future research

Certain limitations need to be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, because the data we used comes from a single organization from a single industrial sector, the findings might not be generalizable to other industrial and cultural contexts (Newman et al., Citation2017). To determine the generalizability of our findings, future work should be undertaken in different industrial sectors and countries.

Second, although we collected variables from two sources, we cannot conclusively rule out common method bias and determine causality between psychological entitlement and OCBs through organizational commitment (Cooper et al., Citation2020). In particular, a lagged study does not completely mitigate the effects of the questionnaire response style on common method bias. In the future, researchers should consider adopting a panel design in which all variables are measured at each point in time to provide stronger causal inferences between the variables in our study.

Third, although we focused on OCBs in the present study, we did not examine whether an employee involvement climate moderates the effects of psychological entitlement on other forms of behavior at work. For example, we did not focus on deviant behaviors, which have been examined in previous studies on psychological entitlement (Harvey et al., Citation2014). Future work may consider whether an employee involvement climate also moderates the relationship between psychological entitlement and such behaviors.

Fourth, we only focused on employee involvement climate as a team-level concept. The study of psychological entitlement in a team context offers more opportunities for future research. It is also possible that psychological entitlement, similar to other personality variables, can be conceptualized as a team-level phenomenon (Hofmann & Jones, Citation2005). For example, the proportion of psychologically entitled team members within a team can impact the team’s overall functioning. Future research can also examine when a particularly entitled team member could alter the overall sense of the justice climate in the team.

Fifth, our study focused on affective commitment as it has been found to have a stronger relationship with OCBs than other dimensions of commitment (Cetin et al., Citation2015). Future research could also study other conceptualizations of organizational commitment, such as normative and continuance commitment (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990) and commitment to organizational career (Lapointe et al., Citation2019), in conjunction with affective commitment to develop a more comprehensive perspective of the role of organizational commitment.

Finally, in the present study, we did not control for variables such as the justice climate and organizational support, which may foster psychological entitlement and have been shown to influence affective organizational commitment and OCBs (Shore & Wayne, Citation1993; Walumbwa et al., Citation2010). In future studies, researchers should control for such variables to determine whether psychological entitlement explains additional variance in affective commitment and OCBs.

Conclusion

The present study contributes to the growing literature on psychological entitlement by examining the moderating effects of an employee involvement climate at the workgroup level on the OCBs of employees through heightening their affective organizational commitment. Integrating insights from the literature on team climate (Anderson & West, Citation1998) and social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964), we found that an employee involvement climate moderates the effects of psychological entitlement on OCBs through affective organizational commitment, such that the relationship is positive when the employee involvement climate is high and negative when it is low.

In addition to helping us understand the conditions under which entitled employees might be more committed to an organization and engage in greater discretionary OCBs, the present study highlights the need for managers to furnish workgroup members with power, information, rewards, and knowledge. We hope the present study provides a basis from which scholars might conduct further research on the situations under which employees high in psychological entitlement will exhibit positive work attitudes and behaviors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

- Anderson, N., & West, M. A. (1998). Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and validation of the Team Climate Inventory (TCI). Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19(3), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199805)19:3<235::AID-JOB837>3.0.CO;2-C

- Bauer, D. J., Preacher, K. J., & Gil, K. M. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11(2), 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.142

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

- Bliese, P. D. (1998). Group size, ICC values, and group-level correlations: A simulation. Organizational Research Methods, 1(4), 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819814001

- Bosak, J., Dawson, J., Flood, P., & Peccei, R. (2017). Employee involvement climate and climate strength: A study of employee attitudes and organizational effectiveness in UK hospitals. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 4(1), 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-10-2016-0060

- Brislin, R. (1993). Understanding culture’s influence on behavior. Harcourt Brace Publishers.

- Brown, M., & Cregan, C. (2008). Organizational change cynicism: The role of employee involvement. Human Resource Management, 47(4), 667–686. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20239

- Brummel, B. J., & Parker, K. N. (2015). Obligation and entitlement in society and the workplace. Applied Psychology, 64(1), 127–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12023

- Campbell, W. K., Bonacci, A. M., Shelton, J., Exline, J. J., & Bushman, B. J. (2004). Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8301_04

- Cetin, S., Gürbüz, S., & Sert, M. (2015). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior: Test of potential moderator variables. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 27(4), 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-015-9266-5

- Cooper, B., Eva, N., Fazlelahi, F. Z., Newman, A., Lee, A., & Obschonka, M. (2020). Addressing common method variance and endogeneity in vocational behavior research: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103472

- Eissa, G., & Lester, S. W. (2021). A moral disengagement investigation of how and when supervisor psychological entitlement instigates abusive supervision. Journal of Business Ethics, 154, 109–126.

- Fisk, G. M. (2010). “I want it all and I want it now!” An examination of the etiology, expression, and escalation of excessive employee entitlement. Human Resource Management Review, 20(2), 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.11.001

- Giacalone, R. A. (1985). On slipping when you thought you had put your best foot forward: Self-promotion, self-destruction and entitlements. Group & Organization Studies, 10(1), 61–80. − https://doi.org/10.1177/105960118501000104

- Grizzle, J. W., Zablah, A. R., Brown, T. J., Mowen, J. C., & Lee, J. M. (2009). Employee customer orientation in context: How the environment moderates the influence of customer orientation on performance outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1227–1242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016404

- Harvey, P., & Dasborough, M. (2015). Entitled to solutions: The need for research on workplace entitlement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(3), 460–465. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1989

- Harvey, P., & Harris, K. J. (2010). Frustration-based outcomes of entitlement and the influence of supervisor communication. Human Relations, 63(11), 1639–1660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710362923

- Harvey, P., Harris, K. J., Gillis, W. E., & Martinko, M. J. (2014). Abusive supervision and the entitled employee. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(2), 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.08.001

- Harvey, P., & Martinko, M. J. (2009). An empirical examination of the role of attributions in psychological entitlement and its outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(4), 459–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.549

- Hochwarter, W. A., Summers, J. K., Thompson, K. W., Perrewe, P. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2010). Strain reactions to perceived entitlement behavior by others as a contextual stressor: Moderating role of political skill in three samples. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020523

- Hoffman, B. J., Blair, C. A., Meriac, J. P., & Woehr, D. J. (2007). Expanding the criterion domain? A quantitative review of the OCB literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.555

- Hofmann, D. A., & Jones, L. M. (2005). Leadership, collective personality, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.509

- James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1993). Rwg: An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 306–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.306

- Kuenzi, M., & Schminke, M. (2009). Assembling fragments into a lens: A review, critique, and proposed research agenda for the organizational work climate literature. Journal of Management, 35(3), 634–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308330559

- Lapointe, É., Vandenberghe, C., Mignonac, K., Panaccio, A., Schwarz, G., Richebé, N., & Roussel, P. (2019). Development and validation of a commitment to organizational career scale: At the crossroads of individuals’ career aspirations and organizations’ needs. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(4), 897–930. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12273

- Lavelle, J. J., Rupp, D. E., & Brockner, J. (2007). Taking a multifoci approach to the study of justice, social exchange and citizenship behavior: The target similarity model. Journal of Management, 33(6), 841–866. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307307635

- Lawler, E. E.III. (1996). From the ground up: Six principles for building the new logic corporation. Jossey-Bass.

- Lee, A., Gerbasi, A., Schwarz, G., & Newman, A. (2019). Leader–member exchange social comparisons and follower outcomes: The roles of felt obligation and psychological entitlement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12245

- Lee, A., Schwarz, G., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2019). Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3456-z

- Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.131

- Loi, K., Kuhn, K. M., Sahaym, A., Butterfield, K. D., & Tripp, T. M. (2020). From helping hands to harmful acts: When and how employee volunteering promotes workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(9), 944–958. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000477

- Marchington, M., & Kynighou, A. (2012). The dynamics of employee involvement and participation during turbulent times. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(16), 3336–3354. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.689161

- Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organization and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

- Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A Meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

- Miao, Q., Newman, A., Schwarz, G., & Xu, L. (2013). Participative leadership and the organizational commitment of civil servants in China: The mediating effects of trust in supervisor. British Journal of Management, 24, S76–S92. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12025

- Miller, J. D., Price, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2012). Is the narcissistic personality inventory still relevant? A test of independent grandiosity and entitlement scales in the assessment of narcissism. Assessment, 19(1), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111429390

- Muthén, B., & Asparouhov, T. (2012). Bayesian structural equation modeling: A more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026802

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Naumann, S. E., Minsky, B. D., & Sturman, M. C. (2002). Historical examination of employee entitlement. Management Decision, 40(1), 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740210413406

- Neville, L., & Fisk, G. M. (2019). Getting to excess: Psychological entitlement and megotiation attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(4), 555–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9557-6

- Newman, A., Schwarz, G., Cooper, B., & Sendjaya, S. (2017). How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2827-6

- O’Leary-Kelly, A., Rosen, C. C., & Hochwarter, W. A. (2017). Who is deserving and who decides: Entitlement as a work-situated phenomenon. Academy of Management Review, 42(3), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0128

- Organ, D. W., & Ryan, K. (1995). A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 48(4), 775–802. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01781.x

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Podsakoff, N. P., Whiting, S. W., Podsakoff, P. M., & Blume, B. D. (2009). Individual- and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1), 122–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013079

- Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

- Richardson, H. A., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2005). Integrating managerial perceptions and transformational leadership into a work-unit level model of employee involvement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(5), 561–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.329

- Riordan, C. M., Vandenberg, R. J., & Richardson, H. A. (2005). Employee involvement and organizational effectiveness: An organizational system perspective. Human Resource Management, 44(4), 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20085

- Rose, K. C., & Anastasio, P. A. (2014). Entitlement is about ‘others’, narcissism is not: Relations to sociotropic and autonomous interpersonal styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 59, 50–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.004

- Schreurs, B., Guenter, H., Schumacher, D., Van Emmerik, I. H., & Notelaers, G. (2013). Pay-level satisfaction and employee outcomes: The moderating effect of employee-involvement climate. Human Resource Management, 52(3), 399–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21533

- Shore, L. M., & Wayne, S. J. (1993). Commitment and employee behavior: Comparison of affective commitment and continuance commitment with perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(5), 774–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.5.774

- Smith, M. B., Wallace, J. C., Vandenberg, R. J., & Mondore, S. (2018). Employee involvement climate, task and citizenship performance, and instability as a moderator. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(4), 615–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1184175

- Snijders, T. A. B. (2005). Power and sample size in multilevel linear models. In B. S. Everitt & D. C. Howell (Eds.), Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science (Vol. 3, pp. 1570–1573). Wiley.

- Snow, J. N., Kern, R. M., & Curlette, W. L. (2001). Identifying personality traits associated with attrition in systematic training for effective parenting groups. The Family Journal, 9(2), 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480701092003

- Suliman, A. M. T. (2002). Is it really a mediating construct? The mediating role of organizational commitment in work climate-performance relationship. Journal of Management Development, 21(3), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710210420255

- Taylor, R. (2013). Psychological contract and OCBs: Psychological entitlement as a moderator [Paper presentation].Academy of Management Proceedings, Lake Buena Vista, Florida. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2013.14261abstract

- Treadway, D. C., Yang, J., Bentley, J. R., Williams, L. V., & Reeves, M. (2019). The impact of follower narcissism and LMX perceptions on feeling envied and job performance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(7), 1181–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1288151

- Wallace, J. C., Edwards, B. D., Paul, J., Burke, M., Christian, M., & Eissa, G. (2016). A multilevel model of employee innovation: Understanding the effects of regulatory focus, thriving, and employee involvement climate. Journal of Management, 42(4), 838–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313506462

- Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., & Oke, A. (2010). Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(3), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018867

- Weiss, H., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). An affective events approach to job satisfaction. In B. M. Staw, & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 18, pp. 1–74). JAI Press.

- Westerlaken, K. M., Jordan, P., & Ramsay, S. (2016). What about ‘MEE’: A measure of employee entitlement and the impact on reciprocity in the workplace. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(3), 392–404. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.5

- Wheeler, A. R., Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Whitman, M. V. (2013). The interactive effects of abusive supervision and entitlement on emotional exhaustion and co-worker abuse. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(4), 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12034

- Whitman, M. V., Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Shanine, K. K. (2013). Psychological entitlement and abusive supervision: Political skill as a self-regulatory mechanism. Health Care Management Review, 38(3), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182678fe7

- Zohan, D., & Luria, G. (2005). A multilevel model of safety climate: Cross-level relationships between organization and group-level climates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 616–628.