Abstract

In European countries, the COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to a demanding work situation for office employees who have been required to work from home (hereinafter referred to as remote workers). Due to curfews, school closures, and leisure restrictions in Austria, remote work circumstances have changed compared to before the pandemic. By combining event system theory with transactional stress theory, we aim to identify the most important resources for maintaining remote workers’ well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. We collected daily data (five working days for each remote worker) once from March to May 2020 (2222 employees) and again from November 2020 to January 2021 (1268 employees) and explored the role of personal (self-goal setting, self-efficacy, home-office experience), external (equipment at home), and organizational (work-related and social) resources for changes in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement. Well-being and engagement decreased less when remote workers indicated high resources of self-efficacy and social support at the beginning of the crises. Results further reveal that an improvement in resources from the first to the second measurement was associated with a reduced decline in well-being, productivity, and engagement, respectively. We discuss implications for HRM and provide suggestions for future research.

Due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, employees in Austria have been obligated to work from home during at least two periods, once in spring (March–May 2020) and once again in autumn (October 2020–January 2021) when COVID-19 cases increased significantly (hereafter, in line with former studies, employees working from home are defined as remote workers Waizenegger et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021). Remote work is not a new phenomenon and is well established in many organizations (López-Igual & Rodríguez-Modroño, Citation2020). So far, studies conducted before the pandemic have been ambivalent regarding the impact of remote work on employees’ quality of work life, finding both positive and negative effects on well-being (Anderson et al., Citation2015; Boell et al., Citation2013; Tavares, Citation2017), productivity (Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Citation2020; Gajendran & Harrison, Citation2007; Hill et al., Citation2003; Nakrošienė et al., Citation2019), and engagement (Kim & Coghlan, Citation2020).

However, it is questionable whether remote work still had both positive and negative effects on remote workers’ work life during this pandemic situation as the COVID-19 pandemic has led to unusual circumstances: Curfews have been imposed, schools and childcare centers have been closed, partners have often also had to work from home, and outdoor leisure activities have been prohibited, which resulted in difficulties to maintain a work-life balance (Syrek et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, during the mandatory periods of restriction in Austria noted above, all office workers were obliged to work from home, which resulted in complex working arrangements, a lack of social interaction, and a lack of support within teams (Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garcés, Citation2020; Chong et al., Citation2020; Eurofound, Citation2020; Statista, Citation2020). These circumstances hereafter collectively referred to as lockdown, continued for several months (Bundesministerium, Citation2021; World Health Organization, Citation2020a). Many remote workers were inexperienced and unprepared for this situation and sometimes lacked the resources to deal with it (Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garcés, Citation2020). Therefore, the transferability of previous studies on remote workers’ work life and resources is limited. This leads to the question of how remote workers have been affected by the pandemic situation, and what resources were important to protect their quality of work life during lockdown. The aim of the current study is thus to reassess remote workers’ daily well-being, productivity, and engagement during this enduring demanding work situation and to identify resources that help remote workers maintain their quality of work life.

Previous data have shown that working from home during the first COVID-19 lockdown had negative effects on employees’ well-being and productivity (Eurofound, Citation2020; Galanti et al., Citation2021; George et al., Citation2021; Ralph et al., Citation2020; Syrek et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, it has been shown that personal, external, and organizational job resources can mitigate these negative effects (Coghlan & Kim, Citation2020; Dolce et al., Citation2020; Ralph et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021; Zacher & Rudolph, Citation2021). For instance, social support, job autonomy (Wang et al., Citation2021), and a well-equipped working space (Ralph et al., Citation2020) enhanced the quality of work life during the first COVID-19 lockdown. In addition, studies have revealed that having resources such as one’s own office or desk at home became more important as other family members were required to stay at home as well.

However, most studies to date have only focused on specific resources, without drawing comparisons between them. Comparing resources and determining which resources have been the most important to maintain employee well-being, productivity, and engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic is expected be highly beneficial for prioritizing Human Resource Management (HRM) measures. In addition, it is important to examine a successful investment in resources namely, what happens when employees build up new resources during the pandemic. Specifically, should HRM invest in building resources during pandemics, or is this useless as resources should be there to begin with? Reasons to raise these questions can be drawn from the predictability of the second lockdown. While the first Austrian lockdown in the spring of 2020 was an unprecedented situation, the second, which started in fall of 2020, was widely expected (Popper, Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2020b). Therefore, the recurring demanding work situations could be anticipated and both organizations and employees had time to build up resources (e.g. improve technical equipment at home or offer self-management webinars). Such an increase in resources can lower strain and help employees to cope with the enduring demanding work situation (Hobfoll et al., Citation1990, Citation2003; van Wingerden et al., Citation2016). However, to our knowledge, no study to date has examined the enhancement of resources during the pandemic to provide evidence of the impact of HRM measures during crises.

The present longitudinal diary study aims to fill this gap, and thereby makes several contributions. First, this study contributes to the existing ambivalent remote working literature. It provides insights into remote workers’ work life during the enduring demanding work situation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since this work situation differed from the situation before the pandemic, the results are important for HRM to gain knowledge about the changing work life of remote workers. Further, this study aims to highlight what resources should be provided and prioritized by HRM in order to guide employees through times of crisis and cope with enduring demanding work situations such as pandemics. As the vast majority of research on remote workers’ resources has analyzed only a few resources at a time, and has not compared several personal, external, and organizational job resources with each other (Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garcés, Citation2020; Chong et al., Citation2020; Ralph et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021; Zacher & Rudolph, Citation2021), knowledge is lacking about what resources are most important to mitigate detrimental consequences of demanding work situations.

Second, we analyze the relationship between resource gains and changes in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, we expand the knowledge on how strengthening resources during a crisis affects remote workers’ daily well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement. This will help practitioners to predict the impact of their investments in resources and to prioritize certain HRM measures over others.

These practical contributions are methodologically supported by our study design, our chosen method for analyzing the data, and the theories on which we build. Primarily, our longitudinal diary study design provides new insights into the working lives of remote workers during the enduring demanding work situation in the first eleven months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using such a longitudinal diary design allows us to gain rare insights into the daily situation of remote workers’ everyday working lives and avoids retrospective, potentially distorted judgments on experiences during the pandemic. For data analysis, we applied the latent change score (LCS) model, which allows us to capture true changes over time and to overcome the limitations of difference scores. These methodological strengths are complemented by our theoretical foundations. We build on event system theory (EST, Morgeson et al., Citation2015) and the transactional theory of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984) as these two theories explain the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on two different levels, namely, either on an organizational level or on an individual level. Building on the two approaches allows us to hypothesize how the COVID-19 crises impacts individuals. It builds our theoretical basis for examining how the COVID-19 crises affects remote workers’ work life and what resources were important to protect this quality of work life.

Enduring demanding work situation for remote workers

The COVID-19 pandemic lasted for a long period of time and the demanding work situation burdened remote workers’ lives throughout. For instance, maintaining a work-life balance during lockdowns was almost impossible as work, child care, and leisure time had to be conducted within the same home-based setting (Syrek et al., Citation2022). Activities outside the home were severely restricted which further exacerbated the work-life imbalance (Syrek et al., Citation2022). It stands to reason that this demanding situation would negatively influence employees’ quality of working life. Combining the EST (Morgeson et al., Citation2015) with the transactional theory of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), the enduring demanding work situation of the COVID-19 crisis represents a stressful environment. The main principle of EST is that organizations are systems that interact with the environment and do not operate in isolation (Morgeson et al., Citation2015). Certainly, organizations are permanently influenced by the dynamics of their environments (Katz & Kahn, Citation1966; Morgeson et al., Citation2015), and events can impact these dynamics. Integrating the transactional theory of stress and coping into this framework, these events can either be assessed as harmless or as threatening and stressful (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Such assessments depend on appraisal processes arising from interactions between the environment and the individual. Due to the rapid and prolific spread of the virus, the COVID-19 crisis is characterized by constant threat that has influenced organizational environments and that has driven a compulsion to work from home, led to complex arrangements between colleagues, and minimized social interactions (Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garcés, Citation2020; Chong et al., Citation2020; Eurofound, Citation2020; Gajendran & Harrison, Citation2007; Statista, Citation2020). As many remote workers were previously inexperienced in these working conditions and lacked the resources to deal with them, the COVID-19 situation is likely to have been assessed as a threatening and stressful event.

To gain a comprehensive picture of the quality of working life of remote workers during the pandemic, we focus on their well-being, engagement, and productivity. Well-being at work is central to various domains as it leads to, for example, good social relationships, reduced strain and fewer health complaints (Charalampous et al., Citation2019; Horn et al., Citation2004). Engagement is associated with decreased turnover intention (Bhatnagar, Citation2012; Bothma & Roodt, Citation2012; Cooper & Dewe, Citation2008; Kaduk et al., Citation2019; Wright & Cropanzano, Citation2000), high organizational commitment (Cesário & Chambel, Citation2017; Teo et al., Citation2020), and increased trust (Chughtai et al., Citation2015; Jena et al., Citation2018). These are crucial factors for successful, productive remote working, particularly in times of crisis (Aitken-Fox et al., Citation2020; Lukić & Vračar, Citation2018). Although employers are mainly concerned with employees’ productivity during remote work (Parker et al., Citation2020), exploring this along with well-being, productivity, and engagement considers both, the perspective of remote workers, whose attention lies on their own well-being, and the perspective of employers, whose priority is to successfully lead the company through crises and maintain productive and engaging workers. Since working conditions during the lengthy COVID-19 lockdowns were demanding, we first hypothesize a decline in daily well-being, daily perceived productivity, and daily engagement.

Hypothesis 1: Daily well-being, daily perceived productivity, and daily engagement decrease from time 1 (March to May 2020) to time 2 (November 2020 to January 2021).

Resources during crisis

Resources defined as conditions, personal characteristics, and energies that are perceived as important themselves or that are important in order to reach a desired state are expected to be particularly relevant in times of crisis (Hobfoll, Citation1989). Individuals strive to actively acquire, maintain, and restore resources to overcome strain. As the work situation during COVID-19 is likely to have caused strain (Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garcés, Citation2020; Chong et al., Citation2020; Eurofound, Citation2020; Statista, Citation2020), the acquisition and conservation of resources are highly relevant for coping with this work situation.

In order to consider as many potential resources as possible, we used three selection criteria. First, in accordance with previous studies and theories, we distinguished between personal, external, and organizational (work-related and social) job resources (Demerouti et al., Citation2001; Hobfoll et al., Citation1990; Hobfoll & Lerman, Citation1988; Schaufeli & Taris, Citation2014; Shaw et al., Citation1993). Second, we integrated the results of previous studies regarding personal, external, and organizational job resources of remote workers in crisis situations. For instance, self-goal setting skills (Müller & Niessen, Citation2019), self-efficacy (van Yperen & Snijders, Citation2000), and remote work experience (Tietze & Nadin, Citation2011) have been highlighted as important resources for remote workers. In addition, organizational job resources, like social support, job autonomy, and supportive leadership, have been cited as central during the initial phases of the pandemic (Dolce et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021). Third, we chose resources that can be improved and strengthened by HRM, specifically, those that can add value to processes of selection, support, and/or development of employees. For instance, external resources like good working spaces can be easily improved in terms of equipment and ergonomics by HRM; additionally, our chosen personal and organizational job resources could be enhanced, for example, through training or coaching (Luthans et al., Citation2006, Citation2008). Taking these criteria together, we defined the following resources: (1) personal resources: self-goal setting, self-efficacy, home-office experience; (2) external resources: equipment at home; and (3) organizational job resources. Organizational job resources are divided into (3.1) work-related resources: job security, job latitude (refers to the freedom an employee has to control and organize her/his work, Frese & Zapf, Citation1994), communication during COVID-19; and (3.2) social resources: leader autonomy support, supervisor support, colleague support.

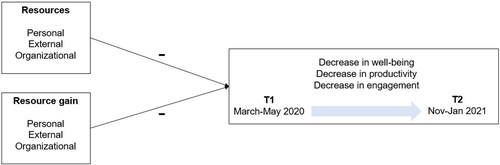

We hypothesize that the negative impact of the enduring demanding work situation is buffered by personal, external, and organizational job resources. For instance, the resource of supportive colleagues may help remote workers feel more connected to their virtual teams, and thus, employees may dare to ask more questions in these difficult times. In turn, this resource may enhance the team climate and quality of work by fostering well-being, engagement, and productivity. Additionally, we examine which resources are most important in mitigating the previously hypothesized decline in work outcomes (see ).

Figure 1. Conceptual Model. The minus signs indicate that resources are negatively related to decreases.

Hypothesis 2.1: Greater availability of personal resources (self-goal setting, home-office experience, self-efficacy) weaken the decline in (a) daily well-being, (b) daily perceived productivity, and (c) daily engagement from time 1 to time 2.

Hypothesis 2.2: Greater availability of external resources (equipment at home) weaken the decline in (a) daily well-being, (b) daily perceived productivity, and (c) daily engagement from time 1 to time 2.

Hypothesis 2.3: Greater availability of organizational job resources weaken the decrease in (a) daily well-being, (b) daily perceived productivity, and (c) daily engagement from time 1 to time 2.

Additional research question (referred to as Hypothesis 3): Which resources are the most important predictors to weaken the decline in (a) daily well-being, (b) daily perceived productivity, and (c) daily engagement from time 1 to time 2?

Gains in resources during crises

In addition to examining the level of resources at a specific point in time (e.g. at the beginning of the first lockdown as it is done in Hypothesis 2 and 3), it is crucial to examine changes in resources during a period of time. Over the course of an ongoing crisis, which can be expected to endure long-term, it becomes vital that organizations go beyond reacting to the crisis, and instead try to manage it proactively (Boiral et al., Citation2021). One way to do this is by trying to increase resources. The question which resources should be strengthened has been of great interest for organizations (Boiral et al., Citation2021). We propose that investing in resources during the pandemic may have led to improvements in remote workers’ well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement. Following an evaluation of whether investing in these resources is worthwhile, the next hypothesis expands on Hypotheses 2 and Hypothesis 3, and reveals what can be achieved through successful HRM measures that improve the necessary resources.

This practical contribution of our study is based on the main principle of conservation of resources theory (COR), which indicates that resources have dynamic characteristics and can be lost and gained by individuals (Hobfoll, Citation1989). Resource gain is associated with health and well-being (Hobfoll, Citation1989, Citation2001), and puts people in a better position in which they are able to spend more resources. Furthermore, gaining resources is linked to the facilitation of additional resource gains (Hobfoll, Citation1989, Citation2001; Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). For instance, organizations that have invested in high ergonomic standards for employees at home (i.e. external resources) may reduce employees’ physical discomfort so they feel less exhausted after work, which will lead to higher productivity. This increased productivity, in turn, can enhance self-efficacy (i.e. personal resources) and thus increase other employee resources. Consequently, resource gains during the COVID-19 pandemic may have been helpful in stimulating an improvement spiral of resources and avoiding decreases in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement. Therefore, we propose that an investment in resources during the pandemic has a significant impact on employees’ quality of work life. Specifically, an enhancement in resources (e.g. investment by HRM in technical equipment for remote workers) during earlier phases of the pandemic should have helped employees gain more resources in later phases of the pandemic and thereby been essential for mitigating the decrease in remote workers’ well-being, productivity, and engagement.

Hypothesis 4: The higher the resource gains the lower the decline in (a) daily well-being, (b) daily perceived productivity, and (c) daily engagement, from time 1 to time 2.

Method

By following a longitudinal design and using a LCS approach to analyze the data, we are able to capture true changes over time (Ferrer et al., Citation2007). These true changes over time are formed by the levels of daily well-being, daily productivity, and daily engagement at the beginning of the pandemic (time 1) and by their level at the end of our data collection (time 2). Latent changes in the true scores of these variables are then predicted by the level of resources during time 1, during time 2 (Hypothesis 2 and 3), and by the latent change of resources (Hypothesis 4).

Procedure and sample

We recruited participants via our personal contacts to organizations and agencies located in Austria. To improve participation, we promised to provide respondents with information on the results of the study. The response rate was high since lockdowns were exceptional situations and employers were more interested in the well-being, productivity, and engagement of their remote workers than before the pandemic. The survey was distributed by our contact persons, who mainly comprised human resource managers. Participants worked in various fields, such as social organizations, media companies, consultancy agencies, and public organizations. Participants were first contacted in March 2020 and informed about the daily procedure and the planned second data collection stage in November 2020. For both data collection stages, we used the following procedure: As soon as participants registered for, gave their informed consent regarding, and agreed to take part in the study, they received the general questionnaire, including items on socio-demographics and resources (conducted using SoSci Survey). Participants were asked to provide their email address and (if preferred), also their phone number, to which the day-specific online questionnaires would be sent. For the invitation to the questionnaire at the second measurement time in November, all participants were contacted via email. To ensure we strictly followed the ethical American Psychological Association (Citation2018) ethical guidelines, email addresses and telephone numbers were saved separately to the answers in the questionnaires; thus, they could not be matched to respondents. The provided information in the questionnaires was completely anonymous.

At 5:30pm on each of the five working days following registration, the participants received an email or text message with a request to fill out the day-specific questionnaire, hereafter referred to as the daily questionnaire. This structured daily questionnaire captured their well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement. To ensure that only remote workers participated, we added a filter question to the general survey and included only remote workers in the survey. In November, we contacted all participants via their registered email addresses with the invitation to take part in the second stage of data collection.

From March to May 2020, a total of 2222 participants (9821 daily entries) were included in the analysis; these participants had filled out at least one daily questionnaire. For the second data collection stage, from November 2020 to January 2021, we contacted these same 2222 participants again and received responses from 1268 participants, which equated to 5950 daily entries (response rate of 57.1 percent). Data were accessed and analyzed only once the data collection window had closed.

The majority of respondents were women (61.9 percent). The average age was 41.9 years (SD = 12.1), and the ages ranged from 16 to 71 years. Thirty percent of the participants had at least one child. Leader responsibility was indicated by 29.1 percent of participants and their mean organizational tenure was 17.4 years (SD = 13.3). More than 82 percent were highly educated (at least high school and/or university degree level).

Measures

We collected data from two sets of questionnaires (general questionnaire and daily questionnaires) for each data collection period. Time 1 refers to data collected from March to May 2020, and time 2 includes data from November 2020 to January 2021. Measuring constructs at different points in time helped us to reduce common method bias, per the recommendation of Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003). Data collected from the general questionnaire, which included the assessment of resources, were collected at least one day before those of the day-specific questionnaires. Additionally, well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement were measured daily to reduce common method bias.

All our selected instruments have been validated and published in psychology-related peer-reviewed journals. Additionally, all scales were confirmed to have a Cronbach’s alpha score of above .70 indicating good internal consistency. The instruments of each construct are provided in .

Table 1. Overview of the measured constructs.

Control variables

We included the control variables age, gender, and number of children, measured at time 1 because previous studies have shown that these factors can influence changes in remote workers’ productivity and well-beingFootnote1 (Gajendran & Harrison, Citation2007; Harker Martin & MacDonnell, Citation2012; Kossek et al., Citation2006).

Data analysisFootnote2

To test our hypotheses, we used the LCS approach. This approach is suitable for testing individual change (Ferrer & McArdle, Citation2010). It models a latent change variable that represents an increase or decrease in the latent true score of variables between two measurement times. In doing so, individual change can be modeled, potential contaminating factors between individuals can be excluded, and limitations of change scores can be overcome (Matusik et al., Citation2020; McArdle, Citation2009). For data analysis, we used Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2009) and the restricted maximum likelihood estimation method with robust standard errors for estimation.

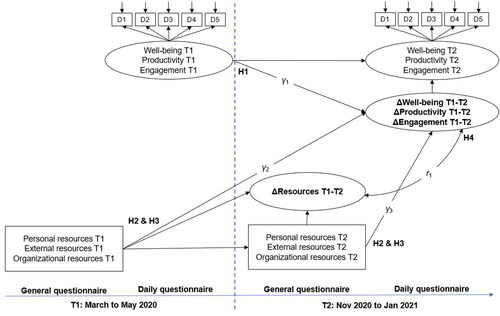

To test Hypothesis 1, we built latent constructs of well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement (e.g. well-being at time 1, well-being at time 2) and modeled LCSs for these constructs, representing the change from time 1 to time 2 (e.g. Δwell-being). Before testing the hypotheses, we examined the appropriateness of our model by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Day-specific variables of well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement from time 1 and time 2 were used to build the latent constructs. Subsequently, the latent change variable (e.g. Δwell-being) was modeled. To do so, the path between the variable at time 1 and the variable at time 2 were restricted to one. Further, the latent change variable was set as a latent cause of the variable at time 2 with a factor loading fixed to one. The latent change factor (e.g. Δwell-being) then represented the true change in the variable from time 1 to time 2. A depiction of the model is shown in .

Figure 2. A two-factor latent change score (LCS) model. Paths γ1 represent proportional change from well-being, perceived productivity, or engagement measured at time 1 to those measured at time 2. Paths γ2 represent the effect of resources measured at time 1 on this proportional change. Paths γ3 represent the effect of resources measured at time 2 on this proportional change. Correlation r1 represents the relationship between proportional change in resources and proportional change in well-being, perceived productivity, or engagement. Unlabeled paths are fixed to 1.0 (McArdle, Citation2009).

The LCS approach can model factors that are predicted by other variables and dynamics over time (McArdle, Citation2009). Therefore, the LCS of, for example, Δwell-being can be predicted by the resources. To test Hypothesis 2, the impact of resources (at time 1 and time 2) on changes in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement were analyzed. In these effects are displayed as paths γ2 (resources at time 1) and paths γ3 (resources at time 2).

For Hypothesis 3, LCSs in resources were modeled. Correlations between the LCSs of resources and the LCSs of well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement were examined (r1). High correlations indicated a strong relationship between changes in resources and changes in work outcomes. Additionally, since Hypothesis 3 is not a directional hypothesis, we used two-sided p-values for the exploratory analysis leading to more conservative testing. By utilizing a large sample size, we followed the recommendations of Funder and Ozer (Citation2019) and interpreted our results in terms that are meaningful in context and do not reduce the estimation of effect sizes on artificial benchmarks.

To evaluate model fit, we used three frequently used indices (Hertzog et al., Citation2003; Li et al., Citation2014; Sianoja et al., Citation2018), namely the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, Steiger, Citation1990), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI, Bentler, 1990). To indicate the most important resources, we followed the recommendation of Funder and Ozer (Citation2019) to interpret the γ paths of all resources in the context of our study design.

Results

shows the means, standard deviations, internal consistencies, and intercorrelations of the study variables. The interrelation between time 1 and time 2 of well-being was r = .50, that of perceived productivity was r = .24, and that of engagement was r = .69. Well-being was positively related to all resources, except for job latitude at time 1. Likewise, perceived productivity was positively related to most resources, except for job latitude at both time 1 and time 2, and for remote work experience at time 1. Additionally, engagement was positively related to most resources, except for job latitude at time 1 and remote work experience at time 1.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, internal consistencies, and correlations

Table 2. (Continued)

First, we conducted the CFAs to test the measurement correctness of our model. We used the standard method for CFA namely, the fixed factor method. Each multilevel CFA contained daily well-being, daily perceived productivity, or daily engagement variables as manifest factors. The model fit of the six CFAs well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement from time 1 and time 2, respectively was acceptable.

We tested Hypothesis 1 using the LCS model. Here, the LCS was estimated for each outcome variable (well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement). Acceptable model fit was found for well-being (CFI = .94, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .043), perceived productivity (CFI = .90, TLI = .89, RMSEA = .051), and engagement (CFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .060). In line with Hypothesis 1, well-being (MΔ = −.24, p < .001), perceived productivity (MΔ= −.04, p < .05), and engagement (MΔ= −.07, p < .001) decreased from time 1 to time 2. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

Hypothesis 2 stated that personal, external, and organizational job resources mitigated the decline in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement. To test this, we added personal, external, and organizational job resources (as manifest variables) individually (one at a time) into the model. It was found that certain personal, external, and organizational job resources weakened the decrease in well-being and engagement. However, neither personal nor organizational job resources were related to a decrease in perceived productivity. The explained variances of the LCSs, as well as the resulting γ2 coefficients of personal, external, and organizational job resources from time 1 and time 2, are provided in .

Table 3. Estimated path coefficients for latent change score models.

Personal resources: The model including the effect of personal resources on changes in well-being (CFI = .95, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .034), changes in perceived productivity (CFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .043), and changes in engagement (CFI = .92, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .050) showed acceptable model fit. The personal resource self-efficacy was shown to prevent the decline in well-being (γ2 = .14, p < .001) and in engagement (γ2 = .13, p = .004). Additionally, self-goal setting was significantly related to a reduced decline in engagement (γ2 = .10, p = .007). Taken together, we can partly confirm Hypothesis 2.1. Higher personal resources were related to a less strong decline in well-being and engagement but were not related to perceived productivity.

External resources: Concerning changes in well-being, external resources, such as having access to necessary materials (γ2 = .07, p < .05) and having good technical equipment (γ2 = .06, p < .05), were important. Contrary to Hypothesis 2.2, having a dedicated home workspace was related to a stronger decrease in well-being. However, for perceived productivity, the external resource of having access to materials was relevant for a reduced decline (γ2 = .08, p < .05). Thus, Hypothesis 2.2 is partially supported. The presence of specific external resources was related to a reduced decline in well-being and perceived productivity but was not related to a reduced decline in engagement.

Organizational job resources: High job latitude and social support from colleagues were associated with a reduced decrease in well-being and engagement (). Additionally, having high job security and being satisfied with the organization’s communication about COVID-19 mitigated the decrease in well-being (). Referring to the control variables included as predictors on the LCS, age (γ2 = −.006, p < .01) and gender (γ2 = .09, p < .05) were significant. Men were found to be slightly more satisfied than women, and younger remote workers showed lower levels of well-being, regardless of their organizational job resources. Furthermore, an indication of high leader autonomy support (γ2 = .12, p < .05) was related to higher engagement. This, Hypothesis 2.3 is partially supported: higher organizational job resources were associated with a reduced decrease in well-being and engagement, but not with changes in perceived productivity.

For Hypothesis 3, we explored which resources had the highest effect on well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement. For this purpose, we constructed an overall model that included personal, external, and organizational job resources for all outcomes. The most important resources were found to be self-efficacy and social support from colleagues, as these were positively related to a reduced decline in both well-being and engagement (). Furthermore, the findings were in line with those for Hypotheses 1–3; namely, access to necessary materials, technical support, and good communication during lockdowns were associated with a reduced decrease in well-being. A reduced decrease in engagement was related to self-goal setting and leader autonomy support. Contrary to our expectations, having a dedicated home workspace and remote work experience were associated with a larger decrease in well-being.

Finally, we tested Hypothesis 4, which suggested that an increase in resources weakened the decline in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement. Overall, an improvement in resources was correlated with less decline in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement (). In particular, having a dedicated office space, enhanced ergonomic standards, and increased remote work experience during the pandemic were important for reducing employees’ decline in well-being, productivity, and engagement, respectively. Increased scope for action and job security were associated with a reduced decline in well-being and engagement. Improved goal-setting skill was positively correlated with a reduced decline in engagement (r2 = .17, p < .001). Improvements in equipment at home were positively related to higher engagement.Footnote3

Table 4. Correlations between changes in well-being, perceived productivity, engagement and changes in resources.

Supplemental analysis

We conducted further analysis of the finding that the resource of having a dedicated home workspace had a negative effect on changes in well-being. To do so, we compared well-being at time 1 and time 2 of remote workers who had access to this resource with remote workers who did not have access to this resource. The supplemental analyses reveal that employees who had a dedicated workspace at time 1 indicated higher well-being at time 1 than people who did not have a dedicated workspace (t(2003) = 2.56, p = .010). However, this significant difference at time 1 cannot be observed at time 2 (t(1087) = 0.73, p = .468).

Discussion

This study examined the role of resources on changes in remote workers’ daily well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. We proposed that remote workers suffered from the enduring demanding work situation, and aimed to show which resources were most important for maintaining remote workers’ well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement by hypothesizing that resources and resource gains can reduce the decline in remote workers’ quality of work life during the pandemic. By using both, a longitudinal diary design to capture actual changes over time, and the LCS method with its unique capability to predict time-varying and/or invariant covariates (Grimm et al., Citation2013), this study adheres to the guidelines on performing LCS models only with true longitudinal data (Grimm et al., Citation2013). Moreover, this study answers the call for more high-quality longitudinal examinations of organizational and work trends (Matusik et al., Citation2020; Mitchell & James, Citation2001; Vantilborgh et al., Citation2018). This enables us to provide empirical evidence of dynamic relationships between two constructs without requiring difference scores, which entail significant methodological problems (Edwards, Citation1995).

As predicted, our results reveal that remote workers’ well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement decreased during the first eleven months of the pandemic. These findings are consistent with existing research on the accumulation of strain over time (Bolger et al., Citation1996; Carayon, Citation1996; Fuller et al., Citation2003). According to the transactional stress and coping model proposed by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), employees who initially assessed the COVID-19 pandemic as stressful would also have been likely to assess it in the same way later, as it endured. Although we anticipated this outcome, habituation of remote workers to the pandemic situation could also have happened (Zacher & Rudolph, Citation2021). In this case, remote workers’ well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement would not have decreased. Thus, our findings bring new insights for EST and its main principle, which asserts that environments and organizations interact with each other, and that the impact of this interaction is dependent on individuals’ appraisal and the event’s duration. Events that are assessed as stressful, and that occur repeatedly or persist long-term, lead to greater strain in employees’ environments and can have strong negative impacts long-term. Based on these results, in the context of lockdowns during COVID-19, it stands to reason that if the demanding situation is long-lasting and another lockdown phase follows, even greater decreases in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement will occur.

Corresponding to COR theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989; Hobfoll & Lerman, Citation1988), our results further suggest that personal, external, and organizational job resources helped remote workers to cope with the enduring demanding work situation. However, our findings show that resources cannot be considered as equivalent to each other but must be differentiated in terms of which aspects organizations want to improve. For instance, while high levels of personal resources positively relate to a reduced decline in well-being and engagement, they are not as strongly related to perceived productivity. This finding supports triple match theory, in which resources are more likely to prevent negative consequences of stressors when stressors, resources, and strains match (De Jonge & Dormann, Citation2006). These results are further discussed in the section detailing our study’s implications.

In line with our hypotheses, a smaller decline in remote workers’ well-being and engagement during the pandemic was associated with high self-efficacy and social support from colleagues. Self-efficacy may result from having successfully mastered challenges in the past, as belief in one’s personal efficacy strengthens after successfully overcoming stressful events (Bandura, Citation1994). Furthermore, Benight et al. (Citation1999) have shown that following Hurricane Opal in Florida in 1995, self-efficacy was the most important predictor of low levels of distress. As such, self-efficacy may also be an effective predictor of the ability to master challenges such as those posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Shifting the focus to social support, the high importance of such support from colleagues for reduced decline in both well-being and engagement may have been due to the changing working conditions during the pandemic. For instance, employees could only communicate via digital technology, as face-to-face interaction and brief updates provided on-the-fly were lost (Wang et al., Citation2021), making collaboration with colleagues more difficult. Solutions for overcoming these difficulties and for enhancing social support include online platforms, which have been shown to enhance social interaction among workers (Wang et al., Citation2021). For instance, informal chatting (e.g. through WeChat or DingTalk) have been shown to help employees feel socially supported (Wang et al., Citation2021), and virtual coffee breaks reduce feelings of isolation (van Zoonen et al., Citation2021). Thus, boosting digital social interaction within the organization was a very important resource during lockdowns.

Nevertheless, while the resources considered weakened the decline in well-being they did not completely eradicate the negative effects of the crisis on employees’ well-being. Referring to Herzberg’s (Citation1974) two-factor theory which differentiates between hygiene factors and motivational factors, the resources considered in this study comprise hygiene factors, as they prevent dissatisfaction but do not influence workers’ motivation. For example, job latitude, and having access to necessary materials and communication during COVID-19, minimized the decrease in well-being but did not lead to increased well-being compared to before the pandemic. This suggests that the COVID-19 lockdowns were so stressful to employees that the resources we consider in this study were only able to minimize the damage, without increasing well-being as they may have done over time prior to the pandemic (Demerouti et al., Citation2017).

However, in contrast to our hypothesis, having a dedicated home workspace at home at time 1 (e.g. a desk) reinforced the decline in well-being. An explanation for this effect is found in the supplemental analysis, which revealed that people who had a dedicated home workspace at time 1 indicated significantly higher well-being at time 1 compared to people who did not have their own workspace. This significant difference was no longer found at time 2. People who had a dedicated workspace showed higher well-being at the beginning of the pandemic, but they drop to the same low level of well-being after eleven months and thus, their decrease in well-being from time 1 to time 2 is stronger. This could be an explanation of why having a dedicated workspace has a negative effect on the latent change score of well-being: People with their own workspace started out at a higher level at the beginning of the pandemic and then dropped to the same level of well-being as people without their own workspaces, leading to a stronger decrease in well-being.

As predicted, improvements in resources were positively related to remote workers’ quality of work life. In particular, improvements in remote workers’ equipment at home and increased remote work experience were associated with a reduced decline in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement. This finding is particularly interesting as these two resources can be improved relatively easily. For instance, access to materials, higher ergonomic standards, and good internet connections are resources that can be provided easy via HRM. In addition, remote work experience increased naturally as employees were often forced to work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, remote work experience at the onset of the pandemic was associated with a stronger decline in well-being. Only employees who continued working from home during the summer, and thus gained more remote work experience during the pandemic, indicated a lower decrease in well-being. Concerning HRM, this means that encouraging employees to continue working from home to help them gain more experience in this environment remains important. These findings regarding improvements in resources during the pandemic are especially useful for HRM as they reveal the impact successful measures have on remote workers’ well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement.

Limitations and future research

As with many studies, the present research is subject to several limitations. The first pertains to generalizability. It is possible that only remote workers who had the capacity to participate in our diary study, or who were dissatisfied with the COVID-19 situation, agreed to participate. Additionally, it could be argued that our sample was self-selected; thus, generalization should be conducted with caution. Regarding generalizability across occupational groups, our selection of organizations was random and the study registration was public. Therefore, anyone who was interested in participating was able to do so. This broad distribution and the sample’s diversity can be considered strengths as they enabled us to capture data from multiple occupational sectors. Moreover, organizations did not receive incentives to participate hence, no dependence could have biased participation. Nevertheless, the voluntary nature of this organizational participation raises the question of whether a study on resources only attracts organizations that are interested in this topic and that are willing to invest in their employees. Additionally, voluntariness at the individual level entailed that only remote workers with the capacity to be part of a study participated. As the pandemic lockdowns posed major challenges and individuals had to cope with an unprecedented situation, it is likely that being available for a diary study was not possible for some people (e.g. employees with young children or other care duties). Thus, our results likely underestimate the negative impact of the pandemic. Future studies can avoid this bias by offering incentives or collecting data from organizations that make participation mandatory.

Second, owing to the rapid onset of the pandemic, we attempted to start data collection as soon as possible. However, we recognize in retrospect that we had overlooked certain organizational job resources. This is why communication about COVID-19 measures, social support from colleagues, social support from leaders, and leader autonomy support were only measured at time 2. Nevertheless, an advantage of the second timepoint is that we only captured resources during the crisis and responses are less biased from support or communication before the crisis. For instance, questions about communication regarding COVID-19 measures at the very beginning of the pandemic might have been posed too early, as no measures had yet been taken. However, future studies should examine changes in communication and support during the pandemic.

Another limitation pertains to the measurement scale used for perceived productivity. Specifically, we measured perceived productivity with self-reported data, which are susceptible to socially desirable responses. Indeed, perceived productivity had a right-skewed distribution that may have caused ceiling effects. These limitations could explain the non-significant findings and low variance in productivity. Future studies could ask supervisors about their remote workers’ productivity, or ask colleagues to assess team members’ level of productivity, in order to avoid common method bias, social desirability bias, and right-skewed distributions (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Implications for HRM practices

Several implications for the selection, support, and development of remote workers emerge from this study. With the aim of enhancing well-being, both Human Resource Management teams, hereafter referred to as HRM teams, and line managers carrying leader responsibilities have several options. HRM teams can develop self-efficacy in employees by providing coaching, specifically e-coaching, in times of crisis (Luthans et al., Citation2006, Citation2008). Since self-efficacy has been shown to be relevant for handling change processes in organizations (Heuven et al., Citation2006), and since times of crisis often entail many organizational changes, self-efficacy may be of special interest for HRM teams. Regarding social interaction between colleagues, HRM teams can offer advice to line managers on facilitating informal, as well as formal, interactions via chat rooms and telephone calls (e.g. via WeChat, DingTalk, or Microsoft Teams) and on promoting turning the camera on during such interactions (Wang et al., Citation2021). A review by Boulton et al. (Citation2021), which examined 18 studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighted that video communication, online discussion forums, and telephone assistance served as useful interventions to improve social support at work. These interventions were shown to be most successful when remote workers were able to speak freely and have shared experiences. Therefore, line managers should establish a daily jour fixe online, in which they encourage employees to share their experiences of remote work during the pandemic. In doing so, commonalities may emerge, and remote workers may feel more socially supported and comfortable.

Furthermore, improvements to remote workers’ workspace design, such as technical equipment, access to necessary materials, and high ergonomic standards, are helpful for remote workers’ well-being. Such improvements could be made by advocating for new technical standards. To further support remote workers, HRM teams could offer team training, motivate line managers to cultivate an open form of communication about COVID-19 measures, and provide greater scope for action in order to promote remote workers’ well-being.

Self-goal setting skills were also shown to be relevant in engaging employees. HRM teams can introduce self-structuring exercises into the selection process in order to assess applicants’ ability to set goals. To support existing employees in their self-goal setting skills, HRM teams can provide self-management training. Furthermore, team and leadership training that foster colleague and autonomy support can improve engagement as well as perceived productivity. Providing access to all necessary materials should also enhance perceived productivity.

What HRM teams and line managers can expect from successful measures for remote workers is not only the effects of increased resources on well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement themselves but also the effect of the improvement itself: If HRM teams and line managers enhance the resources of existing employees, for example, through training, coaching, and implementation of new digital and ergonomic standards, these resources will, in turn, help the employee having access to a bigger pool of resources, gain additional new resources (Hobfoll, Citation1989, Citation2001). For instance, after successful team training, remote workers may rely more on their colleagues and feel more comfortable sharing information. This could lead to higher productivity. In turn, higher productivity could enhance self-efficacy. Taken together, enhancing resources during the COVID-19 pandemic has an enormous positive impact on remote workers’ well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of Eva Straus’ dissertation. She works at the University of Vienna, Austria, and her research covers topics about flexible work and Human Resource Management in times of crisis. No funding was used for the project. We thank the whole team for helping us in collecting the data during the pandemic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 The results do not differ substantially from the reported results.

2 Before the second round of data collection, we pre-registered parts of our hypotheses with the Open Science Framework. As we wanted to capture the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic as early as possible, it was not possible to pre-register any hypotheses before the first data collection stage. However, as all our hypothesis tests include data from the second round of data collection, we could not test our hypotheses before. registering them. The pre-registration can be retrieved here.

3 Appendix A provides descriptive information about positive and negative changes in resources and associated outcome variables.

References

- Aitken-Fox, E., Coffey, J., Dayaram, K., Fitzgerald, S., Gupta, C., McKenna, S., & Wei Tian, A. (2020). Covid-19 has put trust front and centre in human resources management. LSE Business Review (14 Aug 2020). Blog Entry.

- American Psychological Association. (2018). Rules and procedures of the Ethics Committee: 2018. Edited version published in December 1992 in American Psychologist, 1612–1628.

- Anderson, A. J., Kaplan, S. A., & Vega, R. P. (2015). The impact of telework on emotional experience: When, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 882–897. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.966086

- Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). Academic Press.

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A., & Erro-Garcés, A. (2020). Teleworking in the context of the Covid-19 crisis. Sustainability, 12(9), 3662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093662

- Benight, C. C., Swift, E., Sanger, J., Smith, A., & Zeppelin, D. (1999). Coping self-efficacy as a mediator of distress following a natural disaster. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(12), 2443–2464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00120.x

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Bhatnagar, J. (2012). Management of innovation: Role of psychological empowerment, work engagement and turnover intention in the Indian context. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(5), 928–951. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.651313

- Bouckenooghe, D., Devos, G., & van den Broeck, H. (2009). Organizational change questionnaire-climate of change, processes, and readiness: Development of a new instrument. Journal of Psychology, 143(6), 559–599.

- Boell, S. K., Campbell, J., Cecez-Kecmanovic, D., & Cheng, J. E. (2013). The transformative nature of telework: A review of the literature. AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/154058

- Boiral, O., Brotherton, M.‑C., Rivaud, L., & Guillaumie, L. (2021). Organizations’ management of the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review of business articles. Sustainability, 13(7), 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073993

- Bolger, N., Foster, M., Vinokur, A. D., & Ng, R. (1996). Close relationships and adjustments to a life crisis: The case of breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.283

- Bothma, F. C., & Roodt, G. (2012). Work-based identity and work engagement as potential antecedents of task performance and turnover intention: Unravelling a complex relationship. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 38(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v38i1.893

- Boulton, E., Kneale, D., Stansfield, C., Heron, P. N., Sutcliffe, K., Hayanga, B., & Todd, C. (2021). Rapid systematic review of systematic reviews: What befriending, social support and low intensity psychosocial interventions, delivered remotely, may reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adults and how? Version 2; peer review: 2 approved with reservations]. F1000Research. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/177022/1/5c1bc7ef_edd5_421a_a04a_5e13e5a06a30_27076_dylan_kneale_v2.pdf

- Bundesministerium. (2021). Coronavirus - aktuelle Maßnahmen: Informationen über aktuelle Maßnahmen. Federal Ministry. https://www.sozialministerium.at/Informationen-zum-Coronavirus/Coronavirus–-Aktuelle-Ma%C3%9Fnahmen.html.

- Carayon, P. (1996). Chronic effect of job control, supervisory social support, and work pressure on office-worker stress. In S. L. Sauter (Ed.), Organizational risk factors of job stress (2nd ed., pp. 357–370). American Psychological Association.

- Cesário, F., & Chambel, M. J. (2017). Linking organizational commitment and work engagement to employee performance. Knowledge and Process Management, 24(2), 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1542

- Charalampous, M., Grant, C. A., Tramontano, C., & Michailidis, E. (2019). Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: A multidimensional approach. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1541886

- Chong, S., Huang, Y., & Chang, C.‑H. (2020). Supporting interdependent telework employees: A moderated-mediation model linking daily COVID-19 task setbacks to next-day work withdrawal. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(12), 1408–1422.

- Chughtai, A., Byrne, M., & Flood, B. (2015). Linking ethical leadership to employee well-being: The role of trust in supervisor. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2126-7

- Coghlan, A., & Kim, V. (2020). Measuring the factors of teleworking productivity and engagement in a new reality of COVID-19: The case of Austria [Master Thesis]. Germany and Russia, Technical University.

- Cooper, C., & Dewe, P. (2008). Well-being–absenteeism, presenteeism, costs and challenges. Occupational Medicine, 58(8), 522–524. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqn124

- De Jonge, J., & Dormann, C. (2006). Stressors, resources, and strain at work: A longitudinal test of the triple-match principle. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1359–1374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1359

- Delanoeije, J., & Verbruggen, M. (2020). Between-person and within-person effects of telework: A quasi-field experiment. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(6), 795–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1774557

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Demerouti, E., Van den Heuvel, M., Xanthopoulou, D., Dubbelt, L., & Gordon, H. J. (2017). Job resources as contributors to wellbeing. In C. Cooper & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Routledge companions in business, management, and accounting. The Routledge companion to wellbeing at work (pp. 269–283). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315665979-19

- Dolce, V., Vayre, E., Molino, M., & Ghislieri, C. (2020). Far away, so close? The role of destructive leadership in the job demands–resources and recovery model in emergency telework. Social Sciences, 9(11), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9110196

- Edwards, J. R. (1995). Alternatives to difference scores as dependent variables in the study of congruence in organizational research. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 64(3), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1995.1108

- Eurofound. (2020). Living, working and COVID-19. COVID-19 series. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2020/living-working-and-covid-19

- Ferrer, E., & McArdle, J. J. (2010). Longitudinal modeling of developmental changes in psychological research. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(3), 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410370300

- Ferrer, E., McArdle, J. J., Shaywitz, B. A., Holahan, J. M., Marchione, K., & Shaywitz, S. E. (2007). Longitudinal models of developmental dynamics between reading and cognition from childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1460–1473.

- Frese, M. (1989). Theoretical models of control and health. In S. L. Sauter, Hurrell JR, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Job Control and Worker Health (Chapter 6, pp. 107–128). Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Frese, M., & Zapf, D. (1994). Action as the core of work psychology: A German approach. In H. C. Triandis, M. D. Dunnette, & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 4, pp. 271–340). Consulting Psychologists Press. http://www.evidence-based-entrepreneurship.com/content/publications/152.pdf

- Fuller, J. A., Stanton, J. M., Fisher, G. G., Spitzmuller, C., Russell, S. S., & Smith, P. C. (2003). A lengthy look at the daily grind: Time series analysis of events, mood, stress, and satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 1019–1033. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1019

- Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Corrigendum: Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847202

- Gajendran, R. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1524–1541. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524

- Galanti, T., Guidetti, G., Mazzei, E., Zappalà, S., & Toscano, F. (2021). Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 63(7), e426–e432.

- George, T. J., Atwater, L. E., Maneethai, D., & Madera, J. M. (2021). Supporting the productivity and wellbeing of remote workers. Organizational Dynamics, 100869-100878.

- Goodman, S. A., & Svyantek, D. J. (1999). Person–organization fit and contextual performance: Do shared values matter. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55(2), 254–275.

- Grimm, K. J., Castro-Schilo, L., & Davoudzadeh, P. (2013). Modeling intraindividual change in nonlinear growth models with latent change scores. GeroPsych, 26(3), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000093

- Harker Martin, B., & MacDonnell, R. (2012). Is telework effective for organizations? Management Research Review, 35(7), 602–616. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171211238820

- Hertzog, C., Dixon, R. A., Hultsch, D. F., & MacDonald, S. W. S. (2003). Latent change models of adult cognition: Are changes in processing speed and working memory associated with changes in episodic memory? Psychology and Aging, 18(4), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.755

- Herzberg, F. (1974). Motivation-hygiene profiles: Pinpointing what ails the organization. Organizational Dynamics, 3(2), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(74)90007-2

- Heuven, E., Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., & Huisman, N. (2006). The role of self-efficacy in performing emotion work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(2), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.03.002

- Hill, E. J., Ferris, M., & Märtinson, V. (2003). Does it matter where you work? A comparison of how three work venues (traditional office, virtual office, and home office) influence aspects of work and personal/family life. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(2), 220–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00042-3

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Hobfoll, S. E., Freedy, J., Lane, C., & Geller, P. (1990). Conservation of social resources: Social support resource theory. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7(4), 465–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407590074004

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.‑P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

- Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N., & Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 632–643.

- Hobfoll, S. E., & Lerman, M. (1988). Personal relationships, personal attributes, and stress resistance: Mothers’ reactions to their child’s illness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 16(4), 565–589.

- Horn, J. E., Taris, T. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schreurs, P. J. (2004). The structure of occupational well-being: A study among Dutch teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(3), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1348/0963179041752718

- Houghton, J. D., & Neck, C. P. (2002). The revised self-leadership questionnaire. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(8), 672–691.

- Jena, L. K., Pradhan, S., & Panigrahy, N. P. (2018). Pursuit of organisational trust: Role of employee engagement, psychological well-being and transformational leadership. Asia Pacific Management Review, 23(3), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.11.001

- Kaduk, A., Genadek, K., Kelly, E. L., & Moen, P. (2019). Involuntary vs. voluntary flexible work: Insights for scholars and stakeholders. Community, Work & Family, 22(4), 412–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2019.1616532

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. (1966). The social psychology of organizations. Wiley.

- Kim, V., & Coghlan, A. (2020). Measuring the factors of teleworking productivity and engagement in a new reality of COVID-19: The case of Austria, Germany and Russia [TU Vienna]. DataCite. https://repositum.tuwien.at/handle/20.500.12708/15211

- Kossek, E. E., Lautsch, B. A., & Eaton, S. C. (2006). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work–family effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.07.002

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Li, W.‑D., Fay, D., Frese, M., Harms, P. D., & Gao, X. Y. (2014). Reciprocal relationship between proactive personality and work characteristics: A latent change score approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(5), 948–965. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036169

- López-Igual, P., & Rodríguez-Modroño, P. (2020). Who is teleworking and where from? Exploring the main determinants of telework in Europe. Sustainability, 12(21), 8797. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218797

- Lukić, J. M., & Vračar, M. M. (2018). Building and nurturing trust among members in virtual project teams. Strategic Management, 23(3), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.5937/StraMan1803010L

- Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Norman, S. M., & Combs, G. M. (2006). Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(3), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.373

- Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., & Patera, J. L. (2008). Experimental analysis of a web-based training intervention to develop positive psychological capital. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 7(2), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2008.32712618

- Matusik, J. G., Hollenbeck, J. R., & Mitchell, R. (2020). Latent change score models for the study of development and dynamics in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 24(4), 772-801.

- McArdle, J. J. (2009). Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 577–605. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612

- Mitchell, T. R., & James, L. R. (2001). Building better theory: Time and the specification of when things happen. The Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 530–547. https://doi.org/10.2307/3560240

- Morgeson, F. P., Mitchell, T. R., & Liu, D. (2015). Event system theory: An event-oriented approach to the organizational sciences. Academy of Management Review, 40(4), 515–537. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2012.0099

- Müller, T., & Niessen, C. (2019). Self-leadership in the context of part-time teleworking. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(8), 883–898. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2371

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2009). Statistical analysis with latent variables (Vol. 123, No. 6). New York: Wiley.

- Nakrošienė, A., Bučiūnienė, I., & Goštautaitė, B. (2019). Working from home: Characteristics and outcomes of telework. International Journal of Manpower, 40(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2017-0172

- Parker, S., Knight, C., & Keller, A. (2020). Remote managers are having trust issues. Harvard Business Review. https://netfamilybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/remote-managers-are-having-trust-issues.pdf

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

- Popper, N. (2020). COVID-19: Computermodell zeigt mögliche Szenarien auf. Institute of Information Systems Engineering. Technical University Vienna. https://www.tuwien.at/tu-wien/aktuelles/news/news/covid-19-computermodell-zeigt-moegliche-szenarien-auf-1

- Ralph, P., Baltes, S., Adisaputri, G., Torkar, R., Kovalenko, V., Kalinowski, M., Novielli, N., Yoo, S., Devroey, X., Tan, X., Zhou, M., Turhan, B., Hoda, R., Hata, H., Robles, G., Fard, A. M., & Alkadhi, R. (2020). Pandemic programming: How COVID-19 affects software developers and how their organizations can help. Empirical Software Engineering, 25(6), 4927–4961.

- Semmer, N. K., Zapf, D., & Dunckel, H. (1995). Assessing stress at work: A framework and an instrument. Work and Health: Scientific Basis of Progress in the Working Environment, 105–113.

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315.

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. F. Bauer & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health (pp. 43–68). Springer.

- Schwarzer, R., Bäßler, J., Kwiatek, P., Schröder, K., & Zhang, J. X. (1997). The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 46(1), 69–88.

- Shaw, J. B., Fields, M. W., Thacker, J. W., & Fisher, C. D. (1993). The availability of personal and external coping resources: Their impact on job stress and employee attitudes during organizational restructuring. Work & Stress, 7(3), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379308257064

- Sianoja, M., Kinnunen, U., Mäkikangas, A., & Tolvanen, A. (2018). Testing the direct and moderator effects of the stressor–detachment model over one year: A latent change perspective. Work & Stress, 32(4), 357–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1437232

- Statista. (2020, March 18). Homeoffice während der Corona-Krise. Statista Research Department. https://de.statista.com/themen/6093/homeoffice/

- Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4

- Syrek, C., Kühnel, J., Vahle-Hinz, T., & Bloom, J. (2022). Being an accountant, cook, entertainer and teacher-all at the same time: Changes in employees’ work and work-related well-being during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. International Journal of Psychology, 57(1), 20–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12761

- Tavares, A. I. (2017). Telework and health effects review. International Journal of Healthcare, 3(2), 30. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijh.v3n2p30

- Teo, S. T., Bentley, T., & Nguyen, D. (2020). Psychosocial work environment, work engagement, and employee commitment: A moderated, mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102415

- Tietze, S., & Nadin, S. (2011). The psychological contract and the transition from office-based to home-based work. Human Resource Management Journal, 21(3), 318–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2010.00137.x

- van Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2016). A test of a job demands-resources intervention. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(3), 686–701. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-03-2014-0086

- van Yperen, N. W., & Snijders, T. A. B. (2000). A multilevel analysis of the demands-control model: Is stress at work determined by factors at the group level or the individual level? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.182

- van Zoonen, W., Sivunen, A., Blomqvist, K., Olsson, T., Ropponen, A., Henttonen, K., & Vartiainen, M. (2021). Factors influencing adjustment to remote work: Employees’ initial responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136966

- Vantilborgh, T., Hofmans, J., & Judge, T. A. (2018). The time has come to study dynamics at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(9), 1045–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2327

- Waizenegger, L., McKenna, B., Cai, W., & Bendz, T. (2020). An affordance perspective of team collaboration and enforced working from home during COVID-19. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(4), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1800417

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

- Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1), 16–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12290

- World Health Organization. (2020a). COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update. Data as received by WHO from national authorities as of 10am CET 04 December 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19–-11-may-2021

- World Health Organization. (2020b). Strategic preparedness and response plan: 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019‑nCoV). WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-strategy-update

- Wright, T. A., & Cropanzano, R. (2000). Psychological well-being and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 84–94.

- Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. W. (2021). Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 76(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000702

Appendix

Table A1. Mean and standard deviation of remote workers’ difference values in well-being, perceived productivity, and engagement with an increase or decrease in resources.