Abstract

Researchers and practitioners are becoming increasingly concerned with the consequences of modern work arrangements for our understanding of work. This article, alongside the four papers which are included in the special issue, explores the implications of new ways of working for employees. We conceptualise new ways of working as an ongoing transformative process, characterised by unprecedented spread, speed and depth of transformation, and highlight four major changes in work which impact employees’ experiences. We critically evaluate the implications of each change for employees’ attitudes, performance and wellbeing, and suggest areas where more research is needed to deepen our knowledge about how modern work arrangements affect employees.

Work is an essential part of society and increased competition, globalisation, and particularly technology are changing how we define and practice it (Kelliher & Richardson, Citation2012). Indeed, modern work arrangements challenge existing notions about where work takes place, how it is done, who does it and even what work is. The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated existing trends such as remote work, automation and skill gaps, suggesting that an increasing number of individuals carry out work in non-traditional ways. For example, a consultancy report suggests that 20 to 25 percent of the workforce in advanced economies could effectively be working remotely, considering the type of work they do (McKinsey, Citation2021). Estimates further suggest that in about 60 percent of occupations, at least one-third of tasks could be automated, which fundamentally changes how workers carry out their activities (McKinsey, Citation2017). Moreover, the number of gig workers is expected to rise from 43 million in 2018 to 78 million in 2023 (Mastercard, Citation2020).

Prior research has examined the potential benefits and downsides of new ways of working for firm level outcomes or customers, yet we know relatively little about their impact on employees, particularly in middle- and lower-status occupations. This gap is noteworthy as organisations are increasingly adopting new ways of working, which can alter how employees experience work, with important implications for employees’ attitudes, performance, skills, career advancement, and wellbeing (e. g., Chen & Fulmer, Citation2018; De Menezes & Kelliher, Citation2017; Shifrin & Michel, Citation2022). For example, with respect to gig jobs, extant research primarily focuses on consumers rather than on the employees who are working in the gig economy (Gleim et al., Citation2019). Also, it is not clear whether employees in middle- and lower-status occupations benefit from new ways of working, such as flexible working arrangements (Kossek & Lautsch, Citation2018). As such, it is somewhat surprising that there is still a limited understanding of the role of new ways of working in shaping employee outcomes (Gerards et al., Citation2018; Citation2021).

The purpose of this special issue is thus to explore how workers experience changes in ways of working and the resulting individual level implications. To provide a common framework for the papers featured here, this introductory article delves into what we understand as ‘new ways of working’. We discuss different transformative processes which are associated with new ways of working and offer a summary of the four papers that are included in this special issue. We conclude this guest editorial by providing suggestions for research on new ways of working.

New ways of working as ongoing transformative processes

Research has tried to pinpoint the dimensions of modern workplace transformations, seeking to understand why and how work practices evolve and their consequences. Different studies have tended to look at specific dimensions of new forms of work. Some authors have focussed on the timing and location of work, exploring employees who were offered more leeway in deciding when and where they work (Kossek & Lautsch, Citation2018; Van Steenbergen et al., Citation2018). Others have been more interested in investigating who does the work, paying attention to the growth and diversity of flexible contractual arrangements such as agency work, crowd work or freelancing (Cappelli & Keller, Citation2013; Katz & Krueger, Citation2017; Sundararajan, Citation2017). A third stream has been concerned with how work is organised in a more agile, participative, and automatic way and the consequences of that organisation (Cappelli & Tavis, Citation2018; McIver et al., Citation2018). Common to these streams is the latent message of novelty: what is happening is different from the past. This literature has used labels such as ‘new ways of organising’ (Kelliher & Richardson, Citation2012), ‘new ways to work’ (Peters et al., Citation2014), ‘new ways of working’ (Gerards et al., Citation2018) or, more recently, ‘the future of work’ (Beane & Leonardi, Citation2022). The concepts of ‘new’ and ‘future’ often invite the idea of accomplishing a clean break from previous ways of working; that the ‘old’ is irrelevant, obsolete, or superseded, while the ‘new’ is the inevitable next step; that we are undergoing an abrupt transformation with separate ‘before’ and ‘after’ stages.

However, has work not always been transforming? Indeed, ‘The transformation of work’ was the title of a book published in the 1980s. In its introduction the editor wrote: ‘Businessmen, trade unionists, politicians and journalists have all joined in a debate about the changes in employment and labour practices thought to be necessary for advanced capitalist economies to overcome the economic crisis’ (Wood, Citation1989, p. 1). These words are surprisingly telling of today’s situation and could easily have been taken from a text published in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. They convey the idea that work has never stopped being new and that work transformation is not an isolated event, but a process that has been a long time coming.

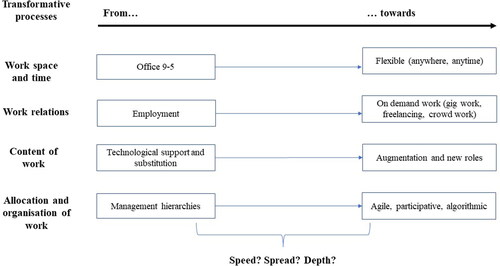

Therefore, this article describes ‘new ways of working’ as ongoing transformative processes that have been unfolding for decades. We suggest that these processes, depicted in , differ in terms of spread, speed, and depth. Spread concerns the extent of the workforce affected by the transformation process. Often, in its initial stages, transformation processes touch only a minority of workers in specific types of roles or industries. In time, changes start expanding to involve larger portions of the workforce and ultimately, they can become standard practice. For instance, the use of computers in the workplace in the 1980s was seen as supportive of technical and clerical work and only a minor percentage of the workforce had to use a computer on a daily basis (Zuboff, Citation1988). Nowadays, it is difficult to find individuals who never use a computer in the context of their work. Similarly, while the use of algorithms to support decision making is currently peripheral, some envision a world in which such use becomes standardised (Malone, Citation2018).

Speed refers to how quickly changes unfold and become normalised. In other words, it concerns how rapidly spread happens. If we take the example of communication technologies, the telephone took over seven decades to increase its user base from 10% to 90% of households in the US. In comparison, mobile phones took about fifteen years and smartphones a mere eight years. Similarly, the speed at which transformation occurs in the workplace can vary. For instance, telework emerged as a new way of working in the 1980s and grew steadily but quite slowly for decades (Eurostat, Citation2020). However, the pandemic boosted the speed of transformation, converting co-located teams into virtual teams almost overnight (Cañibano & Avgoustaki, Citation2022).

Depth pertains to how much the transformation process alters the work experiences of those affected. The extent to which employees actually experience changes to their daily work lives with the introduction of new ways of working can vary substantially. Some changes are shallow, others are moderate, and some deeply transfigure what is understood as work. This can be illustrated by taking flexible working arrangements as an example. While it can entail a minor change, such as providing workers some leeway to decide when to start and finish the workday, it can also enable a profound reorganisation of work and life, as experienced by digital nomads who become fully remote workers (Wang et al., Citation2020).

In the following section, we briefly delve into four major transformative processes and their impact on individual experiences: workspace and time, work relations, the content of work and the allocation of work.

Workspace and time

The flexible working phenomenon dates back to the 1980s when the rise of information and communication technologies enabled homeworking (Baruch, Citation2000). Ever since, the number of people working remotely and during hours other than nine-to-five has slowly but steadily grown. In the EU, the share of the workforce doing at least some of their work from home increased four percentual points between 2009 and 2019 (Ballario, Citation2020). In the UK, CIPD data suggest an 80% growth in homeworking in the last two decades (Chartered Institute of Personnel & Development, Citation2019). In the US the 2005-2015 period saw a 115% increase (Dey et al., Citation2020). The pandemic brought these figures to a completely different level. The Covid-19 crisis dramatically pushed this work transformation, unexpectedly accelerating the spread of homeworking so that, overnight, it went from being relevant to a small group of employees to applying to a majority of the workforce in many sectors and countries.

Despite the general perception that teleworking is beneficial for employees, at least for permanent ones, the literature is still inconclusive (Gajendran & Harrison, Citation2007; Song & Gao, Citation2020) and underlines the paradoxical nature of flexibility (Cañibano, Citation2019; Putnam et al., Citation2014). On the positive side, teleworkers enjoy increased job autonomy because of the flexibility they are afforded over their work location and schedule (Gajendran & Harrison, Citation2007) and report greater levels of satisfaction and commitment than office-based workers (Kelliher & Anderson, Citation2010; Wheatley, Citation2012). The intensity of teleworking, expressed as the number of days an employee works from home, has also been linked to positive outcomes including reduced job stress and less work-life conflict (Fonner & Roloff, Citation2010; Raghuram & Wiesenfeld, Citation2004). A relatively recent experiment on call centre employees further revealed that compared to office workers, teleworkers report more positive attitudes and less work exhaustion, and have lower turnover (Bloom et al., Citation2015). Even within the same employees, existing literature assessing how frequently employees experience a variety of feelings reflecting positive and negative affect shows that on the days during which employees telework, compared to the days they work in the office, they experience improved wellbeing (Anderson et al., Citation2015). The literature has also focussed on employee performance-related outcomes that may be affected by teleworking (De Menezes & Kelliher, Citation2011) and reported that the practice is linked to better job performance and productivity (Bloom et al., Citation2015; Tietze & Nadin, Citation2011) as well as better supervisor performance ratings (Bailey & Kurland, Citation2002; Gajendran & Harrison, Citation2007; Kossek et al., Citation2006).

Although the positive side of teleworking has been widely advocated in the literature, there are numerous studies reporting insignificant results and even supporting negative effects of the practice (e.g. Bailey & Kurland, Citation2002; Kossek & Lautsch, Citation2018). Indicatively, telecommuting has an insignificant impact on organisational commitment (Nieminen et al., Citation2008), self-rated performance, and the relationship quality of teleworkers with co-workers (Gajendran & Harrison, Citation2007). Recent studies have shown that compared to working in the office, teleworking on weekdays or weekends and holidays is actually associated with more rather than less stress (Song & Gao, Citation2020) and that employees may perceive telework as a threat to their jobs and careers (Cañibano & Avgoustaki, Citation2022). An earlier study, comparing the experiences of high-intensity teleworkers and office-based workers, found that the former struggled over being present online and disconnecting outside working hours (Fonner & Roloff, Citation2012). Prior studies also connected teleworking to intensified work (e.g. Avgoustaki & Bessa, Citation2019; Bathini & Kandathil, Citation2019; Kelliher & Anderson, Citation2010), increased work exhaustion (Golden, Citation2012), and decreased career opportunities, such as lower salary growth (Golden & Eddleston, Citation2020) and promotion rates (Bloom et al., Citation2015). The negative impact of telework extends beyond teleworkers, with literature showing that the practice has negative spill-overs on individuals who have reported higher intentions to quit and reduced job satisfaction when their co-workers or managers telecommute (Golden, Citation2007; Golden & Fromen, Citation2011).

Telepresence robots have been studied as a tool to limit the disadvantages of telecommuting linked to the lack of face time, which refers to people ‘seeing and being seen’ (Elsbach et al., Citation2010; Munck, Citation2001). An example of such a robot is a ‘Double’, which consists of an iPad (the head), a retractable stick (the body), and a base with wheels (the feet). The teleworker can move the Double remotely thus being able to see and hear the robot’s environs while the co-workers are able to see the teleworker on the iPad screen. The telepresence robots help in better displaying different dimensions of face time: the amount of active face-to-face interactions between teleworker and co-workers, and the amount of simply being visible at work (Muratbekova-Touron & Leon, Citation2021). Thus, the use of these robots diminishes the teleworkers’ isolation, increases informal communication, and facilitates unplanned meetings (Lee & Takayama, Citation2011; Muratbekova-Touron & Leon, Citation2021). Perceived proximity, i.e. a cognitive and affective sense of relational closeness between teleworkers and co-workers (O’Leary et al., Citation2014), may also be increased through the use of telepresence robots.

On the negative side, the use of telepresence robots may raise issues of privacy; workers may not wish their conversations to be overheard, or to be observed or touched by these machines (Lee & Takayama, Citation2011; Muratbekova-Touron & Leon, Citation2021). In addition, as the robots can move only on a flat floor and are dependent on co-workers to open doors or reconnect robots to a charging station when their battery is flat, the teleworkers sometimes feel akin to disabled workers (Lee & Takayama, Citation2011; Muratbekova-Touron & Leon, Citation2021).

Work relations

The employment contract, the basic foundation that ties individuals to an organisation and states their responsibilities and compensation (Marsden, Citation2004), is slowly waning. Indeed, a plethora of research shows a downward trend in the relevance of employment relations to organise work in favour of alternative options such as temporary help agency workers, crowd workers, freelancers, or contract or service workers (Huws et al., Citation2018; Katz & Krueger, Citation2017, Citation2019; Pesole et al., Citation2018). In the US, alternative work arrangements grew five percentual points between 2005 and 2015 (Katz & Krueger, Citation2017). By then, 0.5 percent of the entire US workforce were already involved in crowd work through platforms (Katz & Krueger, Citation2019). In the UK, nine percent of the population has done some form of crowd work, rising to 22 percent in Italy (Huws et al., Citation2018), while crowd work represents the main job for two percent of the entire workforce in 14 countries in Europe (Pesole et al., Citation2018).

Research has explored the individual implications of these gig employment opportunities. Gig workers provide labour flexibility to organisations but often do not have access to benefits common to ‘regular’ employees, such as health insurance and a minimum wage (Duggan et al., Citation2020; Gleim et al., Citation2019). Gig workers can adjust their working hours and decide when, how much, and how continuously they would like to work, and can have multiple employers and complete tasks on demand. Similar to teleworking, extant studies state that there is a gap with regard to how individuals perceive gig employment opportunities and how these opportunities affect them (Gleim et al., Citation2019). The discussion around gig work emphasises different variants of gig jobs and their positive aspects, such as schedule flexibility and higher levels of compensation (Hall & Krueger, Citation2018), while it criticises the eroded employment standards and lack of regulation associated with this type of work arrangement (Collier et al., Citation2017; Racabi, Citation2021).

Key variants of gig employment opportunities include the sharing economy, which refers to platforms that digitally connect workers, and direct selling, where consumers become direct sellers. A study on sharing economy workers, comparing Uber with more traditional taxi drivers, reports that the former earn similar compensation to taxi drivers and sometimes even more (Hall & Krueger, Citation2018). Chen et al. (Citation2019) confirm these findings. Using data on hourly earnings for Uber drivers, they show that working in such gig jobs helps workers earn more than they would in more traditional arrangements. Another study reveals that not all gig jobs affect workers equally (Gleim et al., Citation2019). Worker perceptions and outcomes are more positive for direct sales workers than for those in the sharing economy, with direct sellers having more self-congruence, meaning better alignment between the brand and the worker’s personality, which improves job satisfaction.

However, prior research has argued that gig workers often hold precarious positions and that compared to ‘regular’ employees, they lack social and job security (e.g. Van Den Groenendaal et al., Citation2022). For example, on-call workers, independent contractors, or freelancers earn considerably less per week than do regular employees with similar characteristics and in similar occupations (Katz & Krueger, Citation2019). Freelancers tend to work irregular hours and their work is often in conflict with their private commitments. In an effort to maintain good relations with their clients, they have to be continually available for work (Gold & Mustafa, Citation2013). They also tend to experience job insecurity as they are themselves continually responsible for finding work (Murgia & Pulignano, Citation2021).

Many variants of gig employment opportunities are algorithm based, meaning algorithms embedded in digital platforms that match supply and demand, and monitor and control workers (Duggan et al., Citation2020). Such jobs put workers under continuous surveillance and apply strict control, which may be perceived as unfair by the workers (Gandini, Citation2019; Pichault & McKeown, Citation2019). Also, by default, algorithm-based jobs eliminate a more interpersonal relationship with management. They reduce human interaction and increase contact with technology, as for example workers are evaluated anonymously by customers instead of their supervisors, which may negatively affect their trust and confidence, resulting in reduced well-being (Duggan et al., Citation2020; Pichault & McKeown, Citation2019). Finally, such jobs transform careers that in the past were stable and linear to be more uncertain and fluid. Although there is evidence showing that freelancers can perceive their career as successful (Lo Presti et al., Citation2018), the literature also challenges such findings. For example, without some level of organisational support, gig workers face challenges in making sense of their work, and they have limited chances to develop their competencies and experience upward mobility within a firm (Kost et al., Citation2020).

Content of work

The type of work that humans do is also subject to ongoing transformation. There is nothing new to the idea that technology automates tasks previously carried out by humans. Since the advent of the steam engine, machines have taken over many tasks hitherto performed by human workers (Raisch & Krakowski, Citation2021). Beyond the initial worry of a massive loss of jobs, recent work shows that as some jobs are replaced, new ones are needed to frame and guide new technological developments (Malone, Citation2018). A consultancy study suggests that by 2030, up to 375 million workers (14 percent of the global workforce) may face a switch in their occupation (Manyika et al., Citation2017).

The evolution in the content of work has important consequences for workers. The most dangerous tasks are slowly replaced by automated processes, making jobs and workplaces safer (Min et al., Citation2019). The most monotonous, tedious, and tiresome tasks within jobs are also being substituted (Frey & Osborne, Citation2017; Lacity & Willcocks, Citation2016), allowing workers to engage in more value-adding, enjoyable and creative areas. Moreover, machines are increasingly thought to not just replace but to complement, augment and unleash human capabilities (Malone, Citation2018). In this way, workers can provide more customised and valuable services (Marinova et al., Citation2017) and increase their problem-solving capabilities (Singh & Hess, Citation2017).

On the other hand, the fear of jobs disappearing and of employment instability can have serious consequences for workers’ mental health. Some argue that ongoing transformations in the content of jobs create uncertainty and anxiety for workers (Min et al., Citation2019). Others underline the increase in cognitive workload that goes hand in hand with more complex and skilled jobs (D’Addona et al., Citation2018). Some question the extent to which workers can smoothly and effectively assume new roles when evidence suggests that employees in jobs vulnerable to automation replacement invest relatively little time in attending training (Koster & Brunori, Citation2021).

The evolution of the content of work, and especially working alongside growingly smart machines, has also sparked questions around workers’ agency and capacity to shape performance expectations (Ter Hoeven et al., Citation2016) and around their privacy (Bhave et al., Citation2020). To study these issues, several scholars have referred to Bentham’s ‘panopticon’ (‘all seeing’ from Greek) metaphor (e.g. Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, Citation2021; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte et al., Citation2014; Muratbekova-Touron & Leon, Citation2021). The panopticon (a circular institutional building where the guard is placed at the centre and the prisoners are in their cells on the circumference) relates to a system of control when one guard observes all prisoners without them being able to know when or whether they are being watched. The prisoners are thus pressured to individually regulate their own behaviour. Scholars point out not only the surveillance issues linked to the transformation of work, but also the adherence of workers to norms for constant availability, putting them in a position of ‘allowed subjection’ and therefore rendering them subjects of ‘free control’ (Leclercq-Vandelannoitte et al., Citation2014). In her study of the new ways of working remotely in co-working spaces, Leclercq-Vandelannoitte (Citation2021) shows how a manager acted to enhance his visibility by increasing managerial control in order to legitimate his role and restore his authority. This visibilising process in remote working, linked to the lack of face time display, raises questions of new relations regarding power, authority and identity that may have negative consequences on subordinates.

Allocation and organisation of work

The way work is negotiated, assigned, and evaluated is also transforming. Conventional management hierarchies are evolving towards more agile, participative, and automated ways of working (Cappelli & Tavis, Citation2018; McIver et al., Citation2018). In particular, agile working has become common practice within organisations and particularly for teams (Edmondson & Gulati, Citation2021). Agile working transforms teams to become more self-managing and have more autonomy to complete tasks according to stakeholder needs, to use resources more efficiently, and to communicate without strict hierarchies in place (Grass et al., Citation2020; Lee & Xia, Citation2010; Peeters et al., Citation2022). The agile way of working is argued to allow organisations and teams to deal with turbulent environments characterised by uncertainty, intense competition, changing customer needs, and new technologies (Abdelilah et al., Citation2018).

In the literature, the benefits of agile working are elucidated through its agile work practices (for a more detailed elaboration, please see Peeters et al., Citation2022). For example, a recent study revealed that agile practices of team autonomy and agile communication contribute to the psychological empowerment and motivation of agile teams, with positive implications for the team’s innovative behaviour and project performance (Malik et al., Citation2021). Another recent study reported that agile working is positively related to team engagement, team performance, and psychological safety climate. In addition, agile work has been associated with outcomes such as higher team member satisfaction (Tripp, Riemenschneider, & Thatcher, Citation2016), favourable team planning behaviours (e.g. different ways of completing tasks and role clarification among team members), and enriched work design experiences, such as autonomy regarding work methods and scheduling, and feedback from others (Junker et al., Citation2022).

Although the literature has demonstrated that a positive link between agile ways of working and team outcomes exists, some have critiqued existing findings for stemming from studies that focus primarily on specific functional domains, team sizes or governance rules (Hobbs & Petit, Citation2017). Also, a few studies have argued that agile working can cause negative outcomes for employees. For example, Annosi et al. (Citation2020) suggest that agile working can harm individual learning and reduce the ability of a team to innovate. Similarly, another recent study showed that agile teams experience peer pressure on delivering and meeting tight deadlines, which has a negative impact on team innovation (Khanagha et al., Citation2022).

While the literature presents agility as a mainly positive new way to allocate work for employees, recent years have also seen the take-off and expansion of other alternatives to management hierarchies, such as algorithmic management, which appear to have more negative outcomes. Digital platforms rely on algorithms, which make autonomous decisions to connect customers and service providers without human involvement. In that sense, increasingly, work is no longer allocated and overseen by managers, effectively removing empathy and human connection from the management of people (Duggan et al., Citation2020). Instead, work evaluation is left to customers and their feedback serves as an input to assign work (Maffie, Citation2022). Bailey (Citation2022, p. 537) describes algorithmic management as ‘a highly onerous form of management’ which puts workers ‘at the mercy of an algorithm whose inner workings are typically opaque to them’. Indeed, some argue that it diminishes workers’ ability to control their work experience, to seek advice or to negotiate developmental, enriching and promotional opportunities (Cameron, Citation2022; Cameron & Rahman, Citation2022; Rosenblat & Stark, Citation2016).

The four papers included in this special issue speak to all of these transformative processes. In the next section, we provide a brief summary of these four articles, before discussing how they point the way towards new research directions.

Overview of the special issue papers

In the first paper featured in this special issue, Salmen and Festing (Citation2021) undertake a systematic review of employee agility research. Seeking to improve the conceptual clarity of this construct and to develop a testable framework of its antecedents, the authors review 61 articles published since 1997 and present descriptive summaries of various approaches to defining and measuring employee agility. Their evaluation of the extant literature culminates in the presentation of a new framework conceptualising employee agility as being composed of learning agility and innovative work behaviour, which are predicted by challenge and hindrance job demands, mediated by strain and moderated by Human Resource (HR) practices that promote flexibility, such as job rotation, team-based work and job counselling. Salmen and Festing conclude by setting out a comprehensive agenda for future research, involving the development of new, validated measures of employee agility; testing the new framework in a variety of different industries, job roles, market economies, and cultural contexts; and examining the role of HR practices and systems in promoting employee agility.

The second paper develops our understanding of agile working further, contrasting the rhetorics of agile to the actual practices and employee experiences of agile working. Through their critical revision of the literature, Roper et al. (Citation2022) identify several streams of work and develop a typology of ‘versions of agile’ extending from the origins of the concept to today. They reflect upon the worker level consequences of each version of agile and its attached practices and theorise on the role that HR management can play in managing different types of agile workers.

Drawing on boundaryless career theory, the third paper in this special issue studies whether gig workers can develop portable career competencies, which may enable them to find better career opportunities outside the gig economy. Specifically, Duggan et al. (Citation2021) examine whether gig workers are able to develop ‘knowing-why’ (career motivation, personal meaning, and professional identity), ‘knowing-how’ (tacit knowledge and expertise), and ‘knowing-whom’ (personal contacts and career network) competencies. The authors collected a sample of 56 gig workers, occupied either as food-delivery workers or rideshare workers, via semi-structured interviews between 2018 and 2019. Contrary to prior literature that has suggested that gig work may facilitate the development of boundaryless career opportunities, this study shows that gig work constrains workers from developing portable knowing-why, knowing-how, and knowing-whom competencies and hampers their future career progression in less precarious jobs.

Do the changes brought about to jobs by the introduction of new technology change workers’ perceptions of their own abilities? Do they alter their sense of identity and accomplishment? In the fourth paper, Moulaï et al. (Citation2022) use the lens of ableism to posit that, as the content of work changes and some human tasks are replaced by machines, the notion of the ideal worker also evolves in workers’ minds. They find that in the process of introducing semi-automated cashier systems in a supermarket setting, workers internalise machines and machinic characteristics as the new worker ideals, which are more efficient and error free. As a result, they come to see themselves as less-able and devalue their own abilities to create meaningful relations with customers. In this process, workers experience an identity tension which affects their sense of self-worth, their social interactions, and their professional role.

Future directions for research on the employee experience of modern ways of working

The papers included in this special issue advance our understanding of how individuals experience modern ways of working by focussing on agile work (Roper et al., Citation2022; Salmen & Festing, Citation2021), gig work (Duggan et al., Citation2021) and working with semi-automated machines (Moulaï et al., Citation2022). They approach the topic from different methodological angles and provide a review of the concept of agility (Roper et al., Citation2022; Salmen & Festing, Citation2021) as well as qualitative perspectives on technology-induced changes related to work (Duggan et al., Citation2021; Moulaï et al., Citation2022). Taken together, the four articles highlight a spectrum of employee experiences which are associated with workplace transformations. While certain forms of agility encourage more flexible, autonomous and self-organised work patterns, other forms of agility are associated with negative experiences such as job insecurity and low work quality (Roper et al., Citation2022; Salmen & Festing, Citation2021). Moreover, gig workers face potentially unmoveable boundaries, which prevent them from developing career competencies and career paths outside the gig economy (Duggan et al., Citation2021). Finally, workplace automation holds severe downsides for workers’ identity, self-perception and self-worth (Moulaï et al., Citation2022). It is noticeable that the articles highlight a lack of clarity when it comes to defining key concepts commonly subsumed under the ‘new ways of working’ movement and demonstrate a need for HR research and practice to consider the types of HR practices which are relevant in non-standard work environments. In what follows, we develop suggestions for researchers to further enhance our understanding of the potential but also the downsides that modern ways of working hold for individuals.

Developing new theoretical frameworks

The papers in this special issue highlight the variety of theoretical perspectives that provide insights into the nature and individual experience of work. This mirrors discussions at a broader level (Godard, Citation2014; Troth & Guest, Citation2020), where scholars have advocated the need for diverse conceptualisations of the employer-employee relationship which take into consideration different interests, power relations and conflicts (Budd, Citation2020). As technology is continuously evolving, the employer-employee relationship changes fundamentally, and new theories are needed to explain how human beings and technology interact in the context of work and how this influences the dynamics of this relationship. We believe that theory development can take place in different ways.

First, we encourage scholars to develop conceptual frameworks and clarifications around the concept of new ways of working. With ongoing transformations, which have taken place over decades, it would be useful to come to a description of when work can be considered ‘new’, and how this contrasts to ‘old’ ways of working. A holistic theory on new ways of working could conceptualise the spread, speed and depth of transformation as key pillars, which help to describe changes in the way that we are working and enables scholars to differentiate between relatively minor adaptations versus large-scale transformation. Doing so is important as it helps researchers to develop a deeper understanding of how workplace changes impact individual and organisational outcomes and tease out tensions that likely exist between organisational strategies, structures and processes and individual feelings, attitudes and wellbeing.

Moreover, following Budd’s (Citation2020) call for multidisciplinary perspectives in HR research, we believe that HR scholars should take insights from other research fields to build new theories, which capture the role of modern technology at work. We consider it especially important to fuse theories on information systems and HR management to develop a deeper understanding of how the human-machine interaction is designed, implemented and experienced by employees. To date, the literatures in both fields have developed largely independently and neglected that technical and human aspects need to be jointly considered to capture the impact of technology on workers more holistically.

A third fruitful avenue to build theory in the area of new ways of working is to extend existing theories on HR management and organisational behaviour by incorporating aspects of the transformative process, which characterises new ways of working. For example, an attribution perspective (Heider, Citation1958; Kelley, Citation1967; Weiner, Citation1985) can enhance our understanding of the workers’ experience by exploring how their perception of the reasons for which changes to work happen influences their attitudes and behaviours. Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986) can provide important insights into how non-traditional workers experience their roles and how this impacts their self-concept. A liminality perspective (Ibarra & Obodaru, Citation2016) might be specifically relevant in uncovering how these individuals, who are often at the periphery of organisations, construct their identities in contexts characterised by high levels of insecurity and instability (Tempest & Starkey, Citation2004). Finally, theory on the psychological contract (Rousseau, Citation1989) can be meaningfully extended by incorporating ideas on the different types of relationships that non-traditional workers engage in and by exploring how they perceive their contributions and retributions vis-a-vis their exchange partners.

Providing a broader conceptualisation of HR practices

A second area where more research is needed relates to rethinking the type of HR practices that are relevant in the context of new ways of working. The strategic HR literature has suggested that organisations should develop bundles of HR practices to enhance the ability, motivation and opportunities of their workforce (Alfes et al., Citation2012; Appelbaum et al., Citation2000). A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated that the practices most commonly included in these bundles are training and development, participation, incentive compensation, performance appraisal, selection and job design (Boon et al., Citation2019). Given the increase in non-traditional ways of working, more research is needed to develop deeper insights into how these bundles of HR practices need to be modified to target a broader group of workers.

For some worker categories, such as gig workers and freelancers, the management and implementation of HR practices is shifted from the organisation to individuals who are now responsible for their own training and upskilling, and for crafting their roles. Hence, we encourage researchers to explore how these individuals interpret HR practices related to their specific work and analyse the extent to which they take ownership of different HR practices. Other worker categories, such as zero hours contracts, have little or no access to most of the traditional HR practices (e.g. incentive compensation, employee participation schemes). More work is therefore needed to understand which HR practices are relevant and how they are experienced by workers in precarious employment conditions. Finally, HR practices that are less often included in traditional HR bundles, such as wellbeing programmes or practices promoting job security, might be of high relevance to workers who are at the periphery of organisations (e.g. temporary or agency workers). Here, we encourage researchers to provide deeper insights into the types of bundles that are meaningful for non-core workers and enhance their ability, motivation and opportunities to perform.

On a broader level, the papers included in this special issue demonstrate the need for HR departments to rethink their role and the scope of their activities (Roper et al., Citation2022). With an increase in non-traditional organisation-worker relationships, questions arise on how HR departments interpret and design the relationship between the organisation and its non-traditional workers and which differences they implement between the core workforce and those operating at the periphery. Research is therefore needed which investigates how HR departments change to address new ways of working and how they develop strategies to redesign their existing bundles of HR practices.

Exploring the post-pandemic HRM landscape

Another fruitful avenue for future research on new ways of working lies in examining the post-pandemic landscape. Flexibility in location of work is becoming increasingly employee-driven rather than employer-driven. Ever since national lockdowns in 2020 and 2021 resulted in unprecedented numbers of workers working from home (approximately 47% during the first lockdown in the United Kingdom; Office for National Statistics, Citation2020), attitudes towards working time and location have shifted for both employers and employees. While many employers are keen to have workers return to the office, a significant proportion of employees are reluctant to do so (Smith, Citation2022). In the USA, 59% of workers who say their jobs can mainly be done from home are working from home all or most of the time, compared to 23% pre-pandemic; in the UK homeworking has increased among all age groups from 2019 to 2022 (Office for National Statistics, Citation2022; Pew Research Centre, Citation2022). How can these divergent attitudes between employers and employees be aligned? Equally, how can the needs of more junior employees for on-the-job learning and knowledge transfer - that are more likely to occur onsite and which have been shown to be detrimentally affected by widespread homeworking within an organisation (Beauregard et al., Citation2019) - be balanced against those of more senior employees, who are more likely to prefer working from home? Some employers have responded initially to these challenges by implementing hybrid working arrangements, but emerging evidence shows that enforcement is often patchy and dependent upon the discretion of individual line managers (Adamson, Beauregard, & Lewis, Citation2023). While this type of idiosyncratic enforcement has the potential to meet operational and individual needs, it also runs the risk of creating perceptions of procedural and distributive injustice and eliciting their negative consequences for employee performance. More sophisticated solutions will need to be developed by HR professionals to address these challenges.

Addressing the employer-employee divide described above also raises the question of who benefits from modern ways of working, and how. Some new ways of working are generally held to involve a shift in control from the employer to the employee, in terms of choices about where and when to work. However, this shift in the balance of power between individual workers and organisations is largely restricted to white-collar, office-based employees, particularly knowledge workers. Others manifest resistance to employer power in other ways. For example, much has been written about the Great Resignation, in which a record number of workers voluntarily left their jobs in 2021; this numbered 47 million workers in the United States (Fuller & Kerr, Citation2022) with resignation rates 40% higher than average in the United Kingdom (Chartered Institute of Personnel Development, Citation2022) and record figures also being achieved in France (Carbonaro, Citation2022). A related phenomenon receiving widespread media attention is ‘quiet quitting’ (Harter, Citation2022), wherein workers are increasingly disengaged emotionally from their work and fulfil the terms of their employment contract but no longer offer employers extra (unpaid) time and effort beyond this. In this context, how will employers foster employee agility—and should they? Critical accounts of agility point to profits for corporations at the expense of quality of work life and, for gig workers supplying on-demand services, worker health and safety (Cameron et al., Citation2021). There is therefore an ethical argument against promoting ever-increasing levels of employee agility. Even for self-employed workers who create portfolio careers, holding multiple jobs simultaneously can be viewed less as a path to self-fulfilment and more as necessary to earn a living in an era where wages have not kept pace with increases in the costs of living. Self-fulfilment is a luxury many cannot afford in societies characterised by a neoliberalist form of capitalism, when pensions are typically reliant upon engagement in standard, full-time work and social safety nets are patchy. Are new ways of working simply new means by which employers can exploit workers?

Conclusion

This special issue sheds light on the various ways in which work is changing and examines the implications of modern work arrangements for employees. While the different transformations in our ways of working can have positive consequences for individuals, organisations and society at large, they also pose challenges with regard to employees’ experience of work and the new types of relationships which develop between employers and employees. New tensions are emerging—between employees with different working preferences within one organisation, between those who use modern work arrangements to achieve self-fulfilment and those who experience ever more precarious job conditions, between opportunities brought by technological advances and the human aspect of work. Given ongoing technological and societal changes, HR departments are key actors which play an important role in addressing those tensions. Doing so requires HR departments to redefine their roles and activities and develop new approaches in the management of a broader group of workers.

ESCP Business School, Heubnerweg 8-10, Berlin, 14059, Germany

[email protected] © 2022 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Grouphttps://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.2149151

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abdelilah, B., El Korchi, A., & Balambo, M. A. (2018). Flexibility and agility: Evolution and relationship. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 29(7), 1138–1162. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-03-2018-0090

- Adamson, M., Beauregard, T. A., & Lewis, S. (2023). Managing through covid: Experiences of managers who are parents. Working families report.

- Alfes, K., Shantz, A., & Truss, C. (2012). The link between perceived HRM practices, performance and well-being: The moderating effect of trust in the employer. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4), 409–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12005

- Anderson, A. J., Kaplan, S. A., & Vega, R. P. (2015). The impact of telework on emotional experience: When, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 882–897. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.966086

- Annosi, M. C., Foss, N., & Martini, A. (2020). When agile harms learning and innovation: (and what can be done about it). California Management Review, 63(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125620948265

- Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., & Kalleberg, A. (2000). Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance systems pay off. ILR Press.

- Avgoustaki, A., & Bessa, I. (2019). Examining the link between flexible working arrangement bundles and employee work effort. Human Resource Management, 58(4), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21969

- Bailey, D. E. (2022). Emerging technologies at work: Policy ideas to address negative consequences for work, workers, and society. ILR Review, 75(3), 527–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939221076747

- Bailey, D. E., & Kurland, N. B. (2002). A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(4), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.144

- Ballario, M. (2020). Telework in the EU before and after the covid-19: Where we were, where we head to. European Institute for Gender Equality. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1950578/telework-in-the-eu-before-and-after-the-covid-19/2702347/

- Baruch, Y. (2000). Teleworking: Benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New Technology, Work and Employment, 15(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-005X.00063

- Bathini, D. R., & Kandathil, G. M. (2019). An orchestrated negotiated exchange: Trading home-based telework for intensified work. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(2), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3449-y

- Beane, M. I., & Leonardi, P. M. (2022). Pace layering as a metaphor for organizing in the age of intelligent technologies: Considering the future of work by theorizing the future of organizing. Journal of Management Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12867

- Beauregard, T. A., Canonico, E., & Basile, K. A. (2019). “The fur-lined rut”: Telework and career ambition. In Clare Kelliher & Julia Richardson (Eds.), Work, working and work relationships in a changing world (1 ed., pp. 17–36). Routledge.

- Bhave, D. P., Teo, L. H., & Dalal, R. S. (2020). Privacy at work: A review and a research agenda for a contested terrain. Journal of Management, 46(1), 127–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319878254

- Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju032

- Boon, C., Den Hartog, D. N., & Lepak, D. P. (2019). A systematic review of human resource management systems and their measurement. Journal of Management, 45(6), 2498–2537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318818718

- Budd, J. W. (2020). The psychologisation of employment relations, alternative models of the employment relationship, and the OB turn. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(1), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12274

- Cameron, L. D. (2022). “Making out” while driving: Relational and efficiency games in the gig economy. Organization Science, 33(1), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1547

- Cameron, L. D., & Rahman, H. (2022). Expanding the locus of resistance: Understanding the co-constitution of control and resistance in the gig economy. Organization Science, 33(1), 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1557

- Cameron, L. D., Thomason, B., & Conzon, V. M. (2021). Risky business: Gig workers and the navigation of ideal worker expectations during the covid-19 pandemic. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(12), 1821–1833. https://doi.org/10.1037/APL0000993

- Cañibano, A. (2019). Workplace flexibility as a paradoxical phenomenon: Exploring employee experiences. Human Relations, 72(2), 444–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718769716

- Cañibano, A., & Avgoustaki, A. (2022). To telework or not to telework: Does the macro context matter? A signalling theory analysis of employee interpretations of telework in times of turbulence. Human Resource Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12457

- Cappelli, P., & Keller, J. R. (2013). Classifying work in the new economy. Academy of Management Review, 38(4), 575–596. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0302

- Cappelli, P., & Tavis, A. (2018). HR goes agile. Harvard Business Review, 96(2), 46–52.

- Carbonaro, G. (2022). No end in sight for the ‘great resignation’ as inflation pushes workers to seek better-paid jobs. Euronews.

- Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. (2019). Megatrends report: Flexible working. https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/megatrends-report-flexible-working-1_tcm18-52769.pdf.

- Chartered Institute of Personnel Development. (2022). The great resignation- fact or fiction? https://www.cipd.co.uk/news-views/cipd-voice/Issue-33/great-resignation-fact-fiction#gref.

- Chen, M. K., Chevalier, J. A., Rossi, P. E., & Oehlsen, E. (2019). The value of flexible work: Evidence from Uber drivers. Journal of Political Economy, 127(6), 2735–2794. https://doi.org/10.1086/702171

- Chen, Y., & Fulmer, I. S. (2018). Fine-tuning what we know about employees’ experience with flexible work arrangements and their job attitudes. Human Resource Management, 57(1), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21849

- Collier, R. B., Dubal, V. B., Carter, C., & Org, E. (2017). Labor platforms and gig work: The failure to regulate. (pp. 106–117.

- D’Addona, D. M., Bracco, F., Bettoni, A., Nishino, N., Carpanzano, E., & Bruzzone, A. A. (2018). Adaptive automation and human factors in manufacturing: An experimental assessment for a cognitive approach. CIRP Annals, 67(1), 455–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2018.04.123

- De Menezes, L. M., & Kelliher, C. (2011). Flexible working and performance: A systematic review of the evidence for a business case. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(4), 452–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00301.x

- De Menezes, L. M., & Kelliher, C. (2017). Flexible working, individual performance, and employee attitudes: Comparing formal and informal arrangements. Human Resource Management, 56(6), 1051–1070. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21822

- Dey, M., Frazis, H., Loewenstein, M. A., & Sun, H. (2020). Ability to work from home: Evidence from two surveys and implications for the labor market in the covid-19 pandemic. Monthly Labor Review, June 2020, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2020.14

- Duggan, J., Sherman, U., Carbery, R., & McDonnell, A. (2020). Algorithmic management and app-work in the gig economy: A research agenda for employment relations and hrm. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(1), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12258

- Duggan, J., Sherman, U., Carbery, R., & McDonnell, A. (2021). Boundaryless careers and algorithmic constraints in the gig economy. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1953565

- Edmondson, A. C., & Gulati, R. (2021). Agility hacks how to create temporary teams that can bypass bureaucracy and get crucial work done quickly. Harvard Business Review, 99(6), 46–49.

- Elsbach, K. D., Cable, D. M., & Sherman, J. W. (2010). How passive ‘face time’ affects perceptions of employees: Evidence of spontaneous trait inference. Human Relations, 63(6), 735–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709353139

- Eurostat. (2020). Employed persons working from home as a percentage of the total employment, by sex, age and professional status (%).

- Fonner, K. L., & Roloff, M. E. (2010). Why teleworkers are more satisfied with their jobs than are office-based workers: When less contact is beneficial. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 38(4), 336–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2010.513998

- Fonner, K. L., & Roloff, M. E. (2012). Testing the connectivity paradox: Linking teleworkers’ communication media use to social presence, stress from interruptions, and organizational identification. Communication Monographs, 79(2), 205–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2012.673000

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.019

- Fuller, J., & Kerr, W. (2022). The great resignation didn’t start with the pandemic. https://hbr.org/2022/03/the-great-resignation-didnt-start-with-the-pandemic.

- Gajendran, R. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1524–1541. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524

- Gandini, A. (2019). Labour process theory and the gig economy. Human Relations, 72(6), 1039–1056. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718790002

- Gerards, R., De Grip, A., & Baudewijns, C. (2018). Do new ways of working increase work engagement? Personnel Review, 47(2), 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-02-2017-0050

- Gerards, R., van Wetten, S., & van Sambeek, C. (2021). New ways of working and intrapreneurial behaviour: The mediating role of transformational leadership and social interaction. Review of Managerial Science, 15(7), 2075–2110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00412-1

- Gleim, M. R., Johnson, C. M., & Lawson, S. J. (2019). Sharers and sellers: A multi-group examination of gig economy workers’ perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 98, 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.041

- Godard, J. (2014). The psychologisation of employment relations? Human Resource Management Journal, 24(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12030

- Gold, M., & Mustafa, M. (2013). ‘Work always wins’: Client colonisation, time management and the anxieties of connected freelancers. New Technology, Work and Employment, 28(3), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12017

- Golden, T. (2007). Co-workers who telework and the impact on those in the office: Understanding the implications of virtual work for co-worker satisfaction and turnover intentions. Human Relations, 60(11), 1641–1667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707084303

- Golden, T. D. (2012). Altering the effects of work and family conflict on exhaustion: Telework during traditional and nontraditional work hours. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(3), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10869-011-9247-0/FIGURES/4

- Golden, T. D., & Eddleston, K. A. (2020). Is there a price telecommuters pay? Examining the relationship between telecommuting and objective career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 116, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103348

- Golden, T. D., & Fromen, A. (2011). Does it matter where your manager works? Comparing managerial work mode (traditional, telework, virtual) across subordinate work experiences and outcomes. Human Relations, 64(11), 1451–1475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726711418387

- Grass, A., Backmann, J., & Hoegl, M. (2020). From empowerment dynamics to team adaptability: Exploring and conceptualizing the continuous agile team innovation process. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 37(4), 324–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12525

- Hall, J. V., & Krueger, A. B. (2018). An analysis of the labor market for Uber’s driver-partners in the United States. ILR Review, 71(3), 705–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793917717222

- Harter, J. (2022). Is quiet quitting real? https://www.gallup.com/workplace/398306/quiet-quitting-real.aspx

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Martino Publishing.

- Hobbs, B., & Petit, Y. (2017). Agile methods on large projects in large organizations. Project Management Journal, 48(3), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/875697281704800301

- Huws, U., Spencer, N. H., Syrdal, D. S., & Holts, K. (2018). Work in the European gig economy: Research results from the UK, Sweden, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Italy. https://uhra.herts.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/2299/19922/Huws_U._Spencer_N.H._Syrdal_D.S._Holt_K._2017_.pdf.

- Ibarra, H., & Obodaru, O. (2016). Betwixt and between identities: Liminal experience in contemporary careers. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.11.003

- Junker, T. L., Bakker, A. B., Derks, D., & Molenaar, D. (2022). Agile work practices: Measurement and mechanisms. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2022.2096439

- Katz, L. F., & Krueger, A. B. (2017). The role of unemployment in the rise in alternative work arrangements. American Economic Review, 107(5), 388–392. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171092

- Katz, L. F., & Krueger, A. B. (2019). The rise and nature of alternative work arrangements in the United States, 1995–2015. ILR Review, 72(2), 382–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793918820008

- Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 192–240). University of Nebraska Press.

- Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2010). Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63(1), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709349199

- Kelliher, C., & Richardson, J. (2012). Recent development in new ways of organizing work. In C. Kelliher & J. Richardson (Eds.), New ways of organizing work: Developments, perspectives and experiences (pp. 1–15) Routledge.

- Khanagha, S., Volberda, H. W., Alexiou, A., & Annosi, M. C. (2022). Mitigating the dark side of agile teams: Peer pressure, leaders’ control, and the innovative output of agile teams. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 39(3), 334–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12589

- Kossek, E. E., & Lautsch, B. A. (2018). Work–life flexibility for whom? Occupational status and work–life inequality in upper, middle, and lower level jobs. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 5–36. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0059

- Kossek, E. E., Lautsch, B. A., & Eaton, S. C. (2006). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work–family effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.07.002

- Kost, D., Fieseler, C., & Wong, S. I. (2020). Boundaryless careers in the gig economy: An oxymoron? Human Resource Management Journal, 30(1), 100–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12265

- Koster, S., & Brunori, C. (2021). What to do when the robots come? Non-formal education in jobs affected by automation. International Journal of Manpower, 42(8), 1397–1419. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-06-2020-0314

- Lacity, M. C., & Willcocks, L. (2016). Robotic process automation at telefónica O2. MIS Quaterly Executive, 15(1), 21–35.

- Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, A. (2021). “Seeing to be seen”: The manager’s political economy of visibility in new ways of working. European Management Journal, 39(5), 605–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.11.005

- Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, A., Isaac, H., & Kalika, M. (2014). Mobile information systems and organisational control: Beyond the panopticon metaphor? European Journal of Information Systems, 23(5), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.11

- Lee, G., & Xia, W. (2010). Toward agile: An integrated analysis of quantitative and qualitative field data. MIS Quarterly , 34(1), 87–114. https://doi.org/10.2307/20721416

- Lee, M. K., & Takayama, L. (2011). “Now, I have a body": Uses and social norms for mobile remote presence in the workplace. In Proceedings of Human Factors in Computing Systems: CHI 2011, Vancouver, California.

- Lo Presti, A., Pluviano, S., & Briscoe, J. P. (2018). Are freelancers a breed apart? The role of protean and boundaryless career attitudes in employability and career success. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(3), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12188

- Maffie, M. D. (2022). The perils of laundering control through customers: A study of control and resistance in the ride-hail industry. ILR Review, 75(2), 348–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793920972679

- Malik, M., Sarwar, S., & Orr, S. (2021). Agile practices and performance: Examining the role of psychological empowerment. International Journal of Project Management, 39(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2020.09.002

- Malone, T. (2018). How human-computer ‘superminds’ are redefining the future of work. MIT Sloan Management Review (Summer Issue), 33–41.

- Manyika, J., Chui, M., Miremadi, M., Bughin, J., George, K., Willmott, P., & Dewhurst, M. (2017). A future that works: AI, Automation, employment, and productivity (Tech. Rep. 60). McKinsey Global Institute Research.

- Marinova, D., de Ruyter, K., Huang, M. H., Meuter, M. L., & Challagalla, G. (2017). Getting smart: Learning from technology-empowered frontline interactions. Journal of Service Research, 20(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670516679273

- Marsden, D. (2004). The ‘network economy’ and models of the employment contract. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 42(4), 659–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2004.00335.x

- Mastercard. (2020). Fueling the global gig economy. https://www.mastercard.us/content/dam/public/mastercardcom/na/us/en/documents/mastercard-fueling-the-global-gig-economy-2020.pdf.

- McIver, D., Lengnick-Hall, M. L., & Lengnick-Hall, C. A. (2018). A strategic approach to workforce analytics: Integrating science and agility. Business Horizons, 61(3), 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.01.005

- McKinsey. (2017). Jobs lost, jobs gained: What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/jobs-lost-jobs-gained-what-the-future-of-work-will-mean-for-jobs-skills-and-wages.

- McKinsey. (2021). The future of work after covid-19. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19.

- Min, J., Kim, Y., Lee, S., Jang, T. W., Kim, I., & Song, J. (2019). The fourth industrial revolution and its impact on cccupational health and safety, worker’s compensation and labor conditions. Safety and Health at Work, 10(4), 400–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SHAW.2019.09.005

- Moulaï, K., Islam, G., Manning, S., & Terlinden, L. (2022). “All too human” or the emergence of a techno-induced feeling of being less-able: Identity work, ableism and new service technologies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.2066982

- Munck, B. (2001). Changing a culture of face time. Harvard Business Review, 79(10), 125–131.

- Muratbekova-Touron, M., & Leon, E. (2021). “Is there anybody out there?” using a telepresence robot to engage in face time at the office. Information Technology & People. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-01-2021-0080

- Murgia, A., & Pulignano, V. (2021). Neither precarious nor entrepreneur: The subjective experience of hybrid self-employed workers. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 42(4), 1351–1377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X19873966

- Nieminen, L. R. G., Chakrabarti, M., McClure, T. K., & Baltes, B. B. (2008). A meta-analysis of the effects of telecommuting on employee outcomes. In 23rd Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, San Francisco, California.

- O’Leary, M., Wilson, J., & Metiu, A. (2014). Beyond being there: The symbolic role of communication and identification in perceptions of proximity to geographically dispersed colleagues. MIS Quarterly, 38(4), 1219–1243. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2014/38.4.13

- Office for National Statistics. (2020). Coronavirus and homeworking in the UK. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/coronavirusandhomeworkingintheuk/april2020.

- Office for National Statistics. (2022). Coronavirus (covid-19) latest insights. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19latestinsights/lifestyle#home-and-hybrid-working.

- Peeters, T., Van De Voorde, K., & Paauwe, J. (2022). The effects of working agile on team performance and engagement. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 28(1/2), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-07-2021-0049

- Pesole, A., Urzi, B. M. C., Fernandez, M. E., Biagi, F., & Gonsalez, V. I. (2018). Platform workers in Europe: Evidence from the colleem survey. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Peters, P., Poutsma, E., Van Der Heijden, B. I. J. M., Bakker, A. B., & Bruijn, T. D. (2014). Enjoying new ways to work: An HRM-process approach to study flow. Human Resource Management, 53(2), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21588

- Pew Research Centre. (2022). Covid-19 pandemic continues to reshape work in America. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2022/02/16/covid-19-pandemic-continues-to-reshape-work-in-america/.

- Pichault, F., & McKeown, T. (2019). Autonomy at work in the gig economy: Analysing work status, work content and working conditions of independent professionals. New Technology, Work and Employment, 34(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12132

- Putnam, L. L., Myers, K. K., & Gailliard, B. M. (2014). Examining the tensions in workplace flexibility and exploring options for new directions. Human Relations, 67(4), 413–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713495704

- Racabi, G. (2021). Effects of city–state relations on labor relations: The case of Uber. ILR Review, 74(5), 1155–1178. https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939211036445

- Raghuram, S., & Wiesenfeld, B. (2004). Work-nonwork conflict and job stress among virtual workers. Human Resource Management, 43(2–3), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20019

- Raisch, S., & Krakowski, S. (2021). Artificial intelligence and management: The automation–augmentation paradox. Academy of Management Review, 46(1), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2018.0072

- Roper, I., Prouska, R., & Chatrakul Na Ayudhya, U. (2022). The rhetorics of ‘agile’ and the practices of ‘agile working’: Consequences for the worker experience and uncertain implications for HR practice. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.2099751

- Rosenblat, A., & Stark, L. (2016). Algorithmic labor and information asymmetries: A case study of Uber’s drivers. International Journal of Communication, 10, 3758–3784.

- Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2(2), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01384942.

- Salmen, K., & Festing, M. (2021). Paving the way for progress in employee agility research: A systematic literature review and framework. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1943491

- Shifrin, N. V., & Michel, J. S. (2022). Flexible work arrangements and employee health: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress, 36(1), 60–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2021.1936287

- Singh, A., & Hess, T. (2017). How chief digital officers promote the digital transformation of their companies. MIS Quarterly Executive, 16(1), 202–220.

- Smith, M. (2022). 50% of companies want workers back in office 5 days a week. CNBC.

- Song, Y., & Gao, J. (2020). Does telework stress employees out? A study on working at home and subjective well-being for wage/salary workers. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(7), 2649–2668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00196-6

- Sundararajan, A. (2017). The future of work. Finance Development, June, 6–11.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

- Tempest, S., & Starkey, K. (2004). The effects of liminality on individual and organizational learning. Organization Studies, 25(4), 507–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604040674

- Ter Hoeven, C. L., van Zoonen, W., & Fonner, K. L. (2016). The practical paradox of technology: The influence of communication technology use on employee burnout and engagement. Communication Monographs, 83(2), 239–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1133920

- Tietze, S., & Nadin, S. (2011). The psychological contract and the transition from office-based to home-based work. Human Resource Management Journal, 21(3), 318–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2010.00137.x

- Tripp, J., Rienemschneider, C., & Thatcher, J. (2016). Job satisfaction in agile development teams: Agile development as work redesign. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17(4), 267–307. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00426

- Troth, A. C., & Guest, D. E. (2020). The case for psychology in human resource management research. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12237

- Van Den Groenendaal, S. M. E., Freese, C., Poell, R. F., & Kooij, D. T. A. M. (2022). Inclusive human resource management in freelancers’ employment relationships: The role of organizational needs and freelancers’ psychological contracts. Human Resource Management Journal, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12432

- Van Steenbergen, E. F., van der Ven, C., Peeters, M. C. W., & Taris, T. W. (2018). Transitioning towards new ways of working: Do job demands, job resources, burnout, and engagement change? Psychological Reports, 121(4), 736–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117740134

- Wang, B., Schlagwein, D., Cecez-Kecmanovic, D., & Cahalane, M. C. (2020). Beyond the factory paradigm: Digital nomadism and the digital future(s) of knowledge work post-covid-19. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 21(6), 1379–1401. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00641

- Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548

- Wheatley, D. (2012). Good to be home? Time-use and satisfaction levels among home-based teleworkers. New Technology, Work and Employment, 27(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00289.x

- Wood, S. (1989). The transformation of work? Skill, flexibility, and the labour process. Routledge.

- Zuboff, S. (1988). In the age of the smart machine: The future of work and power. Basic Books.