Abstract

Integrating insights from conservation of resources theory related to both the positive effects of resources and the detrimental effects of resource loss, this paper examines the effect of job autonomy (an organizational-level resource) on subjective physical pain as mediated by mental health, with experienced workplace incivility (a social stressor) included as a boundary condition. Drawing from the results of a state-wide survey of local government professionals (N = 289), we test a moderated mediation model that estimates the relationships amongst job autonomy, mental health, and physical pain, at differing levels of experienced incivility. Mental health is found to fully mediate the negative relationship between job autonomy and physical pain. When the moderating effect of workplace incivility is incorporated into the model, higher levels of uncivil behavior weaken the otherwise positive and significant effect of job autonomy on mental health. However, the relationship between mental health and physical pain does not depend on levels of workplace incivility. This research has important implications for the management of physical and mental health at work. In particular, the results point to a need to develop human resource policies and practices that both promote job autonomy and tackle experiences of workplace incivility, particularly in local governments.

Experienced incivility undermines the positive effects of job autonomy on mental and physical health

Human resource (HR) management practices—depending on how (in)effectively they are implemented—carry the potential to either positively or negatively shape employee mental health and well-being (Guest, Citation2017; Kowalski & Loretto, Citation2017). Research has demonstrated that effectively implemented job autonomy-enhancing HR policies can improve employee mental health (Park & Searcy, Citation2012). Less well known is the extent to which those same HR policies concomitantly impact on employee physical health. This void is surprising given the close association between mental and physical health and the significant economic costs associated with pain. Physical pain is a major source of lost workplace productivity and it is strongly shaped by socio-relational factors (Melzack, Citation1999). It is commonly linked to psychological distress (Darr & Johns, Citation2008) and musculoskeletal disorders, which are the most common causes of sickness-related work absences and disability pensions in many Western countries (Fjell et al., Citation2007), and, in serious cases, can result in costly inpatient treatment (Malec, Cayner, Harvey, & Timming, Citation1981). Research from across 16 countries suggests that the economic costs of pain are estimated to be between 3% and 10% of gross domestic product (Breivik et al., Citation2006). In Australia, the cost of chronic pain is estimated at $48.3 billion in lost productivity (Deloitte, Citation2019).

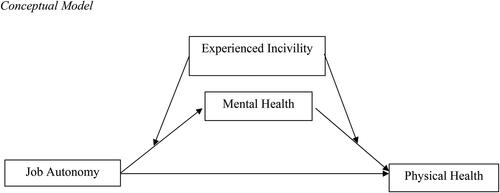

Second to musculoskeletal disorders, stress and stress-related diseases are the next most common cause of health problems in the workplace, and are estimated to cause half of all work absences (Cox et al., Citation2000). High levels of stress can contribute to work-related accidents, employee turnover and presenteeism (Marcatto et al., Citation2016). Work-related stress is a particular issue in the public sector, where rates of high psychological distress exceed those in the private sector (EU-OHSA). A multitude of explanations for this discrepancy have been proposed, including high work demands, greater prevalence of fixed term/casual employment (Jarman et al., Citation2014), and the higher proportion of women in the public workforce who are at an increased risk of factors contributing to poor mental health (Holmlund et al., Citation2022). Similarly, pain arising from musculoskeletal disorders is highly prevalent in public sector employees (Roquelaure et al., Citation2006). Risk factors for experiencing pain among public sector employees include excessive workload and negative working relationships (Marcatto et al., Citation2016). Thus, recognizing the importance of mental and physical health at work, in this study we build on Hobfoll’s (Citation2001) conservation of resources theory (COR) as the overarching framework, and examine how beneficial resources such as job autonomy will help employees to gain resources and improve employees mental health, which in turn may reduce the likelihood of undesirable subjective physical pain. Furthermore, we also consider how experienced incivility, a resource loss representing a salient social stressor and boundary condition, can conditionally influence the impact of job autonomy on mental health, and in turn, on physical pain. The study’s proposed moderated mediation model is depicted in .

By integrating research on job autonomy, experienced incivility, mental health, and physical pain, we hope to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how employees’ mental and physical health are shaped by organizational resources (e.g. job autonomy) and the experience of incivility at work, separately and jointly. In doing so, our study offers both theoretical and empirical contributions to the literature. Theoretically, we echo the concern that resource loss is more salient than resource gain (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). Focusing only on how resource gain impacts employees’ mental and physical health potentially misses the influence of resource loss on these outcomes. Addressing this concern, we take an integrated approach to consider the effect of resource gain and loss on employee mental and physical health. Specifically, we focus on job autonomy as a form of positive resource gain inasmuch as job autonomy improves employee well-being. We focus on experienced work incivility as a resource loss because negative interactions with other people are likely to pose a salient demand on personal resources (Park et al., Citation2014). Incivility is a commonly reported workplace experience with over two-thirds of employees in the U.S. report experiencing workplace incivility (Cortina et al., Citation2001). By taking an integrated approach, our study provides new insights into how and when job autonomy can directly impact employees’ mental health and, indirectly, physical health.

Empirically, addressing the call that resource gain and loss must be understood in context (Halbesleben et al., Citation2014; Hobfoll et al., Citation2018), we focus on local government as a less well studied, but arguably ideal, context to understand the role of resource gain and loss on employees’ mental and physical health. Our choice of the local government sector is motivated by three main reasons. First, local governments have been subjected to unrelenting reforms for decades (Grant & Drew, Citation2017) that often include austerity, amalgamations, organizational restructures, and adaptations to meet increasing community expectations (ALGA, Citation2018; Rayner & Lawton, Citation2018). These reforms have often involved altering organization-level resources, including employee job autonomy. Second, local government employees tend to suffer disproportionately from a range of mental health problems (Hurley et al., Citation2016) and debilitating physical ailments (Khubchandani & Price, Citation2015). Third, workplace incivility is a particularly common behavior in the public sector and in local governments (Hubert & Van Veldhoven, Citation2001; Tsuno et al., Citation2017), making it an appropriate socio-relational stressor boundary condition for our study. Consistent with our theoretical model derived from COR theory, social stressors have been found to be associated with a greater experience of pain in people working in the public sector (Fjell et al., Citation2007). In this light, the local government sector, in all its dysfunction, provides an ideal context in which to examine empirically the effects of interest in our study.

The present research has practical relevance because scholars increasingly understand that physical pain linked to work can have a significant deleterious effect on wider life satisfaction (McNamee & Mendolia, Citation2014) and on the economy (Gaskin & Richard, Citation2012). Our study makes an important and original contribution to ongoing debates surrounding the social determinants of health, both mental and physical, especially in the context of human resource management in the public sector. We demonstrate that managerial decisions on the social organization of job autonomy can influence the employee experience of physical pain, albeit indirectly through mental health, and we also show that experiences of workplace incivility can significantly attenuate the positive health-related benefits of job autonomy. Our results have important implications for the management of physical pain in the local government sector and beyond. This research identifies work-related targets for HR interventions designed to reduce the individual, organizational, and wider societal burdens associated with physical pain at work.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Conservation of resources theory

We draw on COR because it provides a unique framework to help understand why individuals are motivated to protect their current resources and acquire new resources (Hobfoll, Citation2001, Citation2011). Central to COR is the notion that individuals have a limited pool of resources which they are motivated to retain, obtain, and protect. Resources are defined as ‘anything perceived by the individual to help attain his or her goals’ (Halbesleben et al., Citation2014, p. 6). Within this broad definition, scholars have positioned a variety of constructs as resources. Constructive or organizational resources arise from the content of work such as job autonomy (Diestel & Schmidt, Citation2012) and job security (Selenko et al., Citation2013), whereas social resources, including social support (Diestel & Schmidt, Citation2012; Liu et al., Citation2020), arise from the broader work context (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018; Nielsen et al., Citation2017). Consistent with the theoretical tenets of COR, resources across these studies have generally been negatively related to indicators of stress (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). Indeed, a meta-analysis of individual, group, leader, and organizational resources found a positive relationship between resources (at all levels) and employee performance and well-being (Nielsen et al., Citation2017).

Although resource accumulation and protection are important, COR also posits that individuals are particularly sensitive to resource loss (Holmgreen et al., Citation2017), an effect grounded in evolutionary psychology and supported by meta-analytic results (Baumeister et al., Citation2021). According to COR, stress is an outcome of perceived threats to existing resources, actual loss of resources, or the failure to acquire valued resources (e.g. health; sense of purpose; Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). That is, when stressors exceed the capacity of the employee to cope due to a lack of available resources, the individual experiences resource depletion that can and often does result in negative psychological and physiological outcomes (Hobfoll, Citation2011; Citation2018). Despite the centrality of resource loss in COR, ‘it is remarkable how the consequences of such a pivotal concept still remain underinvestigated’ (Halbesleben et al., Citation2014, p. 1345).

The present study seeks to extend COR theory by integrating both the positive effect of job autonomy—an organizational resource ‘inherent in the way work is organized, designed, and managed’, and the resource loss of experienced work incivility—a feature of the social context in which work occurs that characterizes the quality of information and interaction between individuals (Nielsen et al., Citation2017, p. 103). Although COR has been a predominant theory used to understand the experience of burnout and employee stress (Halbesleben et al., Citation2014), the present study extends COR to consider the implications of job autonomy on physical pain, within the broader context of resource loss arising from experiences of work incivility, particularly as it pertains to the Australian local government sector. We propose subjective mental well-being as the mediating process, as further explained below.

Job autonomy

Research investigating the relationship between work and the experience of pain has largely focused on the effect of the physical characteristics of the workplace (e.g. how work is organized and designed) on musculoskeletal issues (Carpini & Parker, Citation2016; McBeth et al., Citation2003). For example, studies identified work tasks such as heavy lifting, kneeling, and standing for lengthy periods to be positively related to a higher risk of experiencing physical pain (McBeth et al., Citation2003). Diverging from the physical demands of work content that may deplete individual resources, the present study examines job autonomy as an important psychological characteristic of work design (Humphrey et al., Citation2007). Job autonomy refers to the extent to which employees are delegated discretion over when, where, and how to carry out their tasks (Grant & Parker, Citation2009). A great deal of research has demonstrated the positive effect of job autonomy on employees’ affective and motivational outcomes such as job satisfaction, employee engagement, organizational commitment, and intrinsic work motivation (Chung-Yan, Citation2010; Humphrey et al., Citation2007; Wegman et al., Citation2018), and behavioral outcomes such as task performance and innovative work behaviors (Carpini et al., Citation2017; De Spiegelaere et al., Citation2016). While limited, extant research specifically in the public sector also suggests that job autonomy significantly influences absenteeism (Kivimäki et al., Citation1997; North et al., Citation1993). As mentioned previously, the experience of pain is associated with absenteeism (Birnbaum et al., Citation2011). We thus suggest that it is possible that job autonomy may be an important organizational resource related to the experience of pain.

Despite a burgeoning body of literature on the psychological and behavioral benefits of job autonomy, little research has investigated whether, how, and when job autonomy, as an artifact of human resource management policy and practice (Nielsen et al., Citation2017), may be associated with physical pain at work (Nixon et al., Citation2011). Within the extant literature on the effects of job autonomy on employee well-being, research suggests that job autonomy is negatively related to physical health (e.g. Glaser et al., Citation2015), and positively related to mental health (Thompson & Prottas, Citation2006; Wood et al., Citation2020). For example, Glaser et al. (Citation2015) report an indirect influence of job autonomy on musculoskeletal pain via emotional irritation, although the direct effect of job autonomy on physical pain was not significant. Wood et al. (Citation2020) found that job autonomy reduces employees’ depression at work. An earlier review by Nixon et al. (Citation2011) also reports that a lack of job autonomy leads to an increase of physical symptoms such as backaches and headaches. However, to date, the relationship between job autonomy and both mental health and physical pain remains understudied. In the present study, we propose an indirect relationship linking job autonomy and physical pain via the effect of mental health. The underlying logic is that job autonomy gives work meaning (Wegman et al., Citation2018) and allows the employee to experience competence and self-control, thus promoting psychological well-being (Nielsen et al., Citation2017) and, in turn, improved physical health. Therefore, the managerial delegation of job autonomy may help improve mental health, and this bolstered mental health potentially reduces the experience of physical pain.

Hypothesis 1: Mental health mediates the negative relationship between job autonomy and physical pain.

The moderating role of experienced incivility

The extent to which the social context may be a powerful resource at work has been well established. For example, Halbesleben’s (Citation2006) meta-analysis on source of social support and burnout found support that social support at work is particularly helpful in attenuating emotional exhaustion and building personal resources. While existing studies have advanced our understanding of the impact of positive social support, less well known is the influence of negative social interactions. It is in this sense that we echo Hobfoll et al. (Citation2018, p. 1052) observation that ‘resource loss is disproportionately more salient than resource gain’. This means that while positive social support may be a useful resource, scholars need to take a more balanced view of resource gains and losses. Thus, in the present study, we examine the potential interaction effect of job autonomy as a resource gain and negative social interaction as a resource loss on employees’ mental health and experience of physical pain.

In the context of COR theory, researchers have suggested that stressful interactions with other people in the workplace can negatively impact the relationship between job autonomy and mental health. For example, research has shown that interpersonal stressors such as experiences of incivility increase work demands by consuming both cognitive and emotional resources (Fasanya & Dada, Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2020; Yao et al., Citation2020a; Yao et al., Citation2020b). This is because the defense mechanisms used to deal with these interactions deplete personal resources and reduce the degree to which people feel they have control over situations, leading to feelings of failure and detachment (Park et al., Citation2014). Experienced incivility is defined as ‘low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms for mutual respect’ (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999, p. 457). Incivility encompasses a constellation of behaviors: rudeness, disrespect, derogatory remarks, isolating actions, insensitivity, a general lack of regard for people, and the erosion of ‘moral’ standards and relational norms in the workplace (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999; Blau & Andersson, Citation2005; Cortina et al., Citation2001; Pearson et al., Citation2001; Pearson & Porath, Citation2009). Examples of incivility at work include: interrupting while another person is talking; gossiping about a colleague; not returning greetings; sending a rude or demeaning email; excluding a colleague from social or work-related meetings; ignoring a request; and undermining a colleague’s credibility (Blau & Andersson, Citation2005; Pearson et al., Citation2000; Pearson et al., Citation2001).

Incivility is a common dysfunction in organizations. Not only is incivility common, but recent meta-analyses suggest it is negatively related to both psychological and physical well-being (Han et al., Citation2022). From a resource loss perspective, experiences of incivility deplete personal resources (Zhu et al., Citation2021) and undermine perceptions of control (Kabat-Farr et al., Citation2018; Vargas et al., Citation2021). Victims of incivility have been shown to disengage from work, be less productive, and exhibit strained and difficult workplace relationships (Pearson et al., Citation2001; Pearson & Porath, Citation2009). These employees also show an increased probability of resigning, with the likelihood of job turnover growing significantly as incivility events become more frequent (Cortina et al., Citation2001; Pearson & Porath, Citation2009). Indeed, participants of Pearson et al. (Citation2001, p. 1404) study report ‘being “depressed”, “down”, “disappointed”, “moody”, “in a funk”, “dissed”, “irritated”, “in a black cloud”, and “hurt”’, all of which are consistent with indicators of poor mental health. Integrating the principle of resource loss from COR theory, we propose the social stressor of experienced incivility will attenuate the otherwise positive relationship between job autonomy (an organizational resource) and employee mental health:

Hypothesis 2a: Experienced workplace incivility moderates the positive relationship between job autonomy and mental health, such that higher levels of experienced workplace incivility weaken the positive effect.

Hypothesis 2b: Workplace incivility moderates the negative relationship between mental health and physical pain, such that higher levels of incivility weaken the protective effect of mental health.

Integrated moderated mediation model

Bring together our hypotheses on job autonomy as predictors of mental health and, in turn, physical pain, and the moderating role of experienced workplace incivility, we hypothesize that experienced work incivility (a salient social stressor) will moderate both the indirect relationship between job autonomy (an organizational resource) and physical pain, as mediated by mental health, as well as the direct relationship between mental health and physical pain. When individuals experience more workplace incivility, such negative experiences are likely to weaken the otherwise positive and significant effect of job autonomy on mental health, and in turn, physical health. We focus on experienced workplace incivility as an interpersonal stressor condition for our study because it has been reported as a particularly common behavior in local governments (Hubert & Van Veldhoven, Citation2001; Tsuno et al., Citation2017). High levels of experienced incivility are often attributed to requirements for local government employees to manage the needs and preferences of multiple simultaneous internal and external stakeholder groups (Timming et al., Citation2019). Consistent with our theoretical model derived from COR theory, social stressors have been found to be associated with a greater experience of pain in people working in the public sector (Fjell et al., Citation2007).

Hypothesis 3: The negative relationship between job autonomy and physical pain, as mediated by mental health, is moderated by experienced workplace incivility such that a higher level of experienced workplace incivility will (a) weaken the positive relationship between job autonomy and mental health and (b) strengthen the negative relationship between mental health and physical pain.

Methods

Sample

We collected data from local government professionals in Western Australia. The design of the survey instrument was informed by a series of focus groups. The survey was administered to all 139 CEOs, who forwarded it to their professional staff occupying a range of positions, including HR professionals, project officers, asset managers, planners, and analysts, among other director-level roles. In total, we received 289 completed questionnaires, including 93 CEOs, for an overall CEO response rate of 67%. Amongst all participants, 47% were female and 32% were located in the State’s metropolitan region (Perth). The majority of participants identified as white (96%), in a relationship (84%), and with a bachelor’s degree or higher (72%). The average age is between 46 and 50 years old, the average tenure in their current organization is 3-5 years, and the average tenure in local government overall is 8-9 years.

Measures

Physical pain

The Freiburg Complaint List (Fahrenberg, Citation1995) was used to measure subjective physical pain. Respondents were asked about the extent to which they feel: (1) neck pain, (2) back pain, (3) shoulder pain, and (4) leg pain. The response scale ranges from 1 (Never) to 5 (Almost every day). The Cronbach’s alpha is .82.

Job autonomy

The five-item autonomy sub-scale of the Work Design Questionnaire (Morgeson & Humphrey, Citation2006) was used to measure job autonomy. This scale asks respondents to rate the extent to which respondents can make autonomous decisions at work. The respondents were asked about the extent to which their jobs: (i) give them a chance to use personal initiative or judgment, (ii) allow them to make a lot of decisions on their own, (iii) provide them with significant autonomy in making decisions, (iv) allow them to make decisions about what methods they use to complete their work, and (v) allow them to decide on how to go about doing their work. The response scale ranges from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). The Cronbach’s alpha is .91.

Mental health

The five-item Mental Health Inventory (Cuijpers et al., Citation2009) was used to measure mental health. This scale asks respondents to rate their mood over the last year. The respondents were asked to assess the extent to which they have felt: (1) nervous, (2) calm and peaceful, (3) downhearted and blue, (4) happy, and (5) so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up. Negative responses were re-coded so that all items are on a scale of 1 (None) to 5 (All the time), such that higher scores are indicative of higher levels of mental health. The Cronbach’s alpha is .83.

Experienced workplace incivility

This variable was measured using Cortina et al. (Citation2001) ten-item workplace incivility scale. Respondents were asked to assess how often someone: (1) put them down or was condescending, (2) paid little attention to them or shows little interest in their opinions, (3) made demeaning, rude, or derogatory remarks about them, (4) addressed them in unprofessional terms, (5) ignored or excluded them, (6) doubted their judgment, (7) made unwanted attempts to draw them into a personal discussion, (8) ignored or failed to speak to them, (9) made jokes at their expense, and (10) yelled, shouted, or swore at them. Responses were recorded from 1 (once or twice a year) to 5 (every day). The Cronbach’s alpha is .91.

Control variables

Consistent with best practice (Bernerth & Aguinis, Citation2016), we included six control variables that are both theoretically and empirically related to our focal variables. Demographically, we included age, gender (1= women, 0 = men), race (1= white, 0 = minority), and marital status (1 = married or defacto partnership, 0 = single). Research has shown that women (Yao et al., Citation2022), younger employees, and minority groups (Han et al., Citation2022) are likely to experience greater levels of workplace incivility. Marital status has been demonstrated to be related to chronic health concerns such that singles were at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke death (Wong et al., Citation2018). Additionally, we control for participants’ job positions and residential regions. Job position (1= CEO, 0 = non-CEO) is included because those in positions of formal authority may enjoy increased psychological well-being (Kifer et al., Citation2013) and have greater decision-making autonomy at work. Residential region (urban = 1 and rural = 0) is included because research suggests that those living in urban areas are at increased risk of depressive symptoms vis-à-vis those living in rural communities (Purtle et al., Citation2019). To ensure full transparency and enhance the generalizability of our results, we also report the results without controls as additional footnotes.

Results

Descriptive statistics, standard deviations, and correlations are presented in . We began by conducting a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to establish the distinctiveness of our study variables. The hypothesized four-factor model fit the data well, χ2 (183) = 420.34, p < .001, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .07. The baseline model, where all items loaded onto a single factor, had poor model fit, χ2 (189) = 1845.49, p < .001, CFI = .42, RMSEA = .19, SRMR = .19, Δ χ2 (6) = 1425.10, p <.001. Table S1 contains additional alternative CFA models. Given the self-reported nature of the data, we complemented our CFA with an analysis of variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). An AVE provides an estimate of both convergent and discriminate validity with a .50 threshold. The mean convergent AVE coefficient was .57 (Min. = .51, Max. = .67), suggesting that the items loaded significantly on their hypothesized factor. The mean discriminate AVE coefficient was .08 (Min. = .00, Max. = .22) suggesting the factors were distinct from one another. Together, these results support the distinctiveness of our variables. Additionally, because Hypotheses 2a/b and 3 specify a moderating effect, common method variance (CMV) is unlikely to significantly influence the results or conclusions of this research because ‘finding significant interaction effects despite the influence of CMV in the data set should be taken as strong evidence that an interaction effect exists’ (Siemsen et al., Citation2010, p. 470).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations amongst study variables.

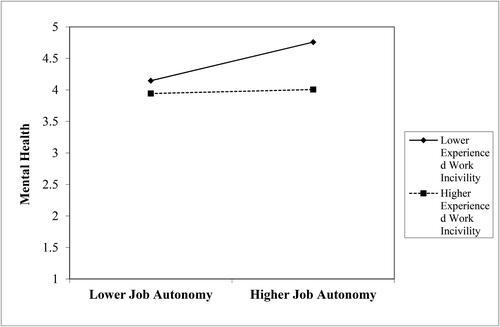

Using mean score composites of our constructs, we tested our first- and second-stage moderated mediation model using the SPSS PROCESS macro (Model 58) (Hayes, Citation2017). PROCESS employs bootstrapping (20,000) in testing the statistical significance of the hypothesized moderated mediation paths. All continuous variables were mean centered in the analyses (Hayes, Citation2017). Age, gender, race, marital status, job position, and residential region were included as statistical controls. reports the results. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the indirect negative effect of autonomy and physical pain was mediated by mental health (B = −0.12, SE = .04, 95%CI [−0.21, −0.05]). Supporting Hypothesis 2a, experienced workplace incivility attenuated the positive relationship between autonomy and mental health (B = −0.30, SE = .09, t = −3.33, p = .001). We probed and visualized the nature of this interaction by plotting simple slope regression lines of mental health regressed on job autonomy for both low (−1SD from the mean) and high (+1SD from the mean) levels of experienced work incivility. As depicted in , job autonomy was positively related to mental health when individuals reported low workplace incivility (B = .40, p < .001), however, this relationship was attenuated when experiences of incivility were high (B = .04, p = .58). Contrary to Hypothesis 2b, experienced incivility did not moderate the positive relationship between mental health and physical pain (B = .20, SE = .14, t = 1.42, p = .16). Finally, in support of Hypothesis 3a, incivility moderated the indirect effect of autonomy on physical pain through mental health (Index = .13, 95% CI = [.04, .24]); however, the index of moderated mediation was not significant for the second-stage moderation between mental health and physical pain (Index = .06, 95% CI = [-0.02, .15]), thus Hypothesis 3b was not supportedFootnote1.

Table 2. Moderated mediation results.

Discussion

The present research integrated insights from COR to examine the potential positive effects of job autonomy (a resource) on local government employees’ subjective physical pain, as mediated by their mental health, while accounting for experienced workplace incivility—a salient social contextual stressor (resource strain). Responding to calls for further understanding of the role of resource gain and loss in predicting employees’ mental and physical health outcomes, our study shows that physical pain is linked, albeit indirectly, to job autonomy, providing empirical support for the notion that job autonomy (as a work-related resource) can support better health outcomes, both mentally and physically (Lovallo, Citation2016; Melzack, Citation1999). However, for the benefit of job autonomy to be fully realized, our study shows that social context is critical. That is, we demonstrate that experienced workplace incivility (as a resource strain) can deplete personal resources, resulting in negative health outcomes. When individuals experience higher levels of workplace incivility, the benefits of increased job autonomy are effectively neutralized.

Theoretical and empirical implications

Our study makes both theoretical and empirical contributions to the COR literature. Theoretically, we take an integrated approach to understand the separate and joint influence of resource gain and loss on employees’ mental and physical health outcomes. While the positive effect of job autonomy (as a resource gain) has been well established, less is known about how potential resource loss can alter the effect of job autonomy on employees’ health outcomes. Specifically, we contribute to the literature by demonstrating the contingency effect of experienced work incivility on the direct effect of job autonomy on mental health, and the indirect effect of autonomy on physical health via the influence of mental health. In doing so, we echo Hobfoll et al. (Citation2018) observation that it is important to have a broad understanding of the interplay of resources gain and loss. It is particularly intriguing that experienced workplace incivility appears to diminish the positive effect of job autonomy on mental health. Thus, experienced workplace incivility is likely to not only directly exhaust personal resources (Han et al., Citation2022), but it also diminishes the positive effect of resource gain (i.e. job autonomy) on individuals’ mental and physical health outcomes. Under higher levels of workplace incivility, individuals seem to benefit less from the benefits of job autonomy in the workplace. Future studies should focus on possible asymmetries in individuals’ responses to gains and losses. For example, resources losses in some individuals might end up triggering more detrimental outcomes (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018).

Empirically, we echo Hobfoll et al. (Citation2018, p. 113) view that ‘COR theory has to be viewed in context’ by focusing on an understudied sector—local government—that is often characterized as having less job autonomy and more workplace incivility. For example, even though job autonomy is widely recognized within the organizational literature to be positively related to individual job performance (Fernandez & Moldogaziev, Citation2011; Gao, Citation2015; Jacobsen & Bøgh Andersen, Citation2017; Kanat-Maymon & Reizer, Citation2017), its adoption in the public sector broadly, and in local government more specifically, has been limited. The rigid bureaucracies endemic to public administration (Barzelay, Citation1992) are perhaps less conducive to delegating discretion over work tasks. Interestingly, our results suggest that compared to non-CEOs, CEOs reported higher job autonomy and experienced incivility, but lower physical health. This finding is consistent with research indicating that leadership positions are associated with poorer physical health (e.g. Glaser et al., Citation2015). Future research should consider further unpacking leadership demands to better understand how leadership positions influence both mental and physical health outcomes.

Practical implications

Our study has two practical implications for the management of human resources in the local government sector. First and foremost, our results align with extant research by confirming that job autonomy is associated with desirable outcomes including better mental and physical health (Nielsen et al., Citation2017). Thus, while the bureaucratic nature of local goverment may make it difficult to strike a balance between a rigid system and job autonomy, it is critical for HR practitioners and senior leaders in local governments to design and implement HR polices that enable employees to experience greater job autonomy. As demonstrated in this research, job autonomy is linked to both improved mental and physical health outcomes, and as such employee well-being can be maximized, and health-related costs minimized simultaneously. One potential way of increasing job autonomy is through job enrichment. Job enrichment involves the vertical expansion of a job through increased responsibility and control over work decisions and processes (Dwyer & Fox, Citation2000). Enriching the jobs of local government employees may be useful in balancing bureaucratic requirements with jobs that provide greater job resources. Increasing job autonomy may also prove a useful job design strategy to support employees experiencing a mental health issue, physical disability, or who are returning to work. Although job enrichment is a useful strategy, prior research suggests optimal physical health outcomes are achieved when jobs are moderately enriched and may result in detrimental physical health when over-enriched (Fried et al., Citation2013).

Second, the HR function in local government must proactively tackle workplace incivility to sustain those benefits. Local governments may have opted not to address workplace incivility in the past due to ambiguity over whether harm was intended or inadvertent (Fischer et al., Citation2016; Pearson et al., Citation2001), but this is an irrelevant question. What is relevant is that experienced incivility, regardless of intention, damages the workplace climate. Therefore, HR managers in the local government sector must develop effective policies and practices to address experienced incivility. For example, a number of local governments have introduced policies related to ‘vexatious’, ‘unreasonable’, and ‘challenging’ behavior in the workplace. These policies empower employees to constructively respond to such behavior by providing feedback about inappropriate behaviors to instigators, discontinuing interactions following a warning, systems to report uncivil treatment, and policies related to incident escalation (City of Albany, 2020; Shire of West Arthur, 2021). Such HR policies support employees by clearly defining uncivil behaviors and provide employees with practical resources to address incivility. By focusing on repeated, long-term uncivil behaviors, rather than singular, one-off occurrences, public administrators can minimize experienced incivility (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999). Moreover, reducing uncivil interactions among local government employees will benefit the public sector by, over time, preventing the erosion of organizational norms around positive interactions, reducing the likelihood of employee disengagement and presenteeism, and obviating a decline in workplace performance and an increase in turnover intent (Pearson & Porath, Citation2009). Successfully addressing persistent workplace incivility, coupled with robust policies aimed at building a culture of job autonomy, will support the mental and physical health of employees and deliver benefits to local government and increase downstream taxpayer satisfaction in the services provided.

Limitations and Future research directions

As with any study, our results should be considered in light of some limitations. The usual caveats apply as with any other cross-sectional survey design. First, although the moderated mediation model goes some way in unpacking the mechanism through which job autonomy is associated with physical pain, the cross-sectional nature of the survey implies that no claims of causality can be made. Second, both the non-random nature of the survey, as well as the single sector from which the research participants were drawn, limit the generalizability of the findings. For example, our sample is not racially diverse as 96% of the participants were white—even though this is an accurate reflection of the racial demographics of the sector. Future studies should consider replicating our findings using data from more racially diverse samples. Third, omitted variable bias is an ever-present concern, especially given the myriad of causes of physical pain that were not included in our models. There are several opportunities for future research to incorporate other important variables, which, due to our sample size and practical issues related to survey length, were unable to be included and tested. It would also be of interest to replicate the present study in the private sector to determine whether public service motivation (Perry, Citation1996) has an impact on the findings.

Conclusions

Given that physical pain is a significant financial liability and a public health concern, what with one out of every five employees suffering from it chronically (Dahlhamer et al., Citation2018), it would seem sensible for local governments to take proactive steps to reduce its prevalence. As demonstrated in our research, the delegation of job autonomy, whereby task discretion and responsibility are granted to employees, can have beneficial effects on mental and physical health. This does not mean that HR managers give up the prerogative to manage, but rather that they should empower local government employees, where possible, to participate in decision-making. However, our study demonstrates that the potential beneficial effect of enhanced job autonomy on subjective health is conditional on the extent to which employees experience incivility. That is, for the benefits of job autonomy for employee health to be realized, HR managers must take proactive steps to mitigate experienced incivility inasmuch as its presence offsets any health benefits from more autonomous work arrangements.

Author contributions

Timming: conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing (review and editing). Carpini: methodology, data curation, and writing (review and editing). Hirst: writing. Tian: writing (review and editing). Notebaert: methodology and writing (review and editing).

Ethical approval

Ethical Approval has been granted by the University of Western Australia Human Ethics Office, RA/4/20/4807.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used in this research are available from the lead author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The pattern of results remained unchanged upon the exclusion of control variables. That is, mental health mediated the negative relationship between autonomy and physical pain (B = -.10, SE = .04, 95%CI [-.18, -.04]). Experienced incivility continued to significantly moderate the relationship between autonomy and mental health (B = -.31, SE = .09, t = -3.51, p = .001). Experienced incivility did not significantly moderate the relationship between mental health and physical pain (B = .20, SE = .14, t = 1.41, p = .16). The index of moderated mediation continued to be significant (Index = .13, 95% CI = [.04, .23]) for the first-stage moderation, whereas the second-stage moderated mediation continued to be non-significant (Index = .05, 95% CI = [-.02, .13]).

Results of a series of one-way ANOVAs compared CEOs to non-CEOs. Specifically, CEOs (M = 3.97, SD = .59) reported significantly higher levels of autonomy than non-CEOs (M = 3.75, SD = .83), F(1,247) = 5.32, p = .02, η2 = .02. CEOs (M = 1.60, SD = .73) reported significantly higher levels of experienced incivility than non-CEOs (M = 1.42, SD = .51), F(1,247) = 5.54, p = .02, η2 = .02. Non-CEOs (M = 2.16, SD = .89) reported significantly higher levels of physical ill-health relative to CEOs (M = 1.91, SD = .87), F(1,234) = 4.44, p = .04, η2 = .02. Finally, there was no statistical difference in reported mental health between CEOs (M = 3.73, SD = .69) and non-CEOs (M = 3.74, SD = .57), F(1,259) = .03, p = .86.

References

- Australian Local Government Association (ALGA). (2018). Local government workforce and future skills report Australia. https://alga.asn.au/local-government-workfoce-and-future-skills-report-australia

- Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. The Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.2307/259136

- Barzelay, M. (1992). Breaking through bureaucracy: A new vision for managing in government. University of California Press.

- Baumeister, V. M., Kuen, L. P., Bruckes, M., & Schewe, G. (2021). The relationship of work-related ICT use with well-being, incorporating the role of resources and demands: A meta-analysis. SAGE Open, 11(4), 215824402110615. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211061560

- Bernerth, J. B., & Aguinis, H. (2016). A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 229–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12103

- Birnbaum, H. G., White, A. G., Schiller, M., Waldman, T., Cleveland, J. M., & Roland, C. L. (2011). Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.), 12(4), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x

- Blau, G., & Andersson, L. (2005). Testing a measure of instigated workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(4), 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26822

- Breivik, H., Collett, B., Ventafridda, V., Cohen, R., & Gallacher, D. (2006). Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. European Journal of Pain (London, England), 10(4), 287–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009

- Carpini, J. A., & Parker, S. K. (2016). Job rotation. In A. Wilkinson & S. Johnstone (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human resource management. Edward Elgar.

- Carpini, J. A., Parker, S. K., & Griffin, M. A. (2017). A look back and a leap forward: A review and synthesis of the individual work performance literature. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 825–885. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0151

- Chung-Yan, G. A. (2010). The nonlinear effects of job complexity and autonomy on job satisfaction, turnover, and psychological well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019823

- Cortina, J. M., Green, J. P., Keeler, K. R., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2017). Degrees of freedom in SEM: Are we testing the models that we claim to test? Organizational Research Methods, 20(3), 350–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428116676345

- Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.64

- Cox, T., Griffiths, A., & Rial-Gonzalez, E. (2000). Research on work-related stress. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work.

- Cuijpers, P., Smits, N., Donker, T., Ten Have, M., & de Graaf, R. (2009). Screening for mood and anxiety disorders with the five-item, the three-item, and the two-item Mental Health Inventory. Psychiatry Research, 168(3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.012

- Dahlhamer, J., Lucas, J., Zelaya, C., Nahin, R., Mackey, S., DeBar, L., Kerns, R., Von Korff, M., Porter, L., & Helmick, C. (2018). Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults - United States. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(36), 1001–1006. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2

- Darr, W., & Johns, G. (2008). Work strain, health, and absenteeism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(4), 293–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012639

- De Spiegelaere, S., Van Gyes, G., & Van Hootegem, G. (2016). Not all autonomy is the same. Different dimensions of job autonomy and their relation to work engagement & innovative work behavior. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 26(4), 515–527. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20666

- Deloitte. (2019). The cost of pain in Australia. https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/economics/articles/cost-pain-australia.html

- Diestel, S., & Schmidt, K. H. (2012). Lagged mediator effects of self-control demands on psychological strain and absenteeism. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 85(4), 556–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2012.02058.x

- Dwyer, D. J., & Fox, M. L. (2000). The moderating role of hostility in the relationship between enriched jobs and health. Academy of Management Journal, 43(6), 1086–1096.

- Fahrenberg, J. (1995). Somatic complaints in the German population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 39(7), 809–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)00151-0

- Fasanya, B. K., & Dada, E. A. (2016). Workplace violence and safety issues in long-term medical care facilities: Nurses’ perspectives. Safety and Health at Work, 7(2), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2015.11.002

- Fischer, T., Van Reemst, L., & De Jong, J. (2016). Workplace aggression toward local government employees: Target characteristics. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 29(1), 30–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-05-2015-0100

- Fjell, Y., Alexanderson, K., Karlqvist, L., & Bildt, C. (2007). Self-reported musculoskeletal pain and working conditions among employees in the Swedish public sector. Work, 28(1), 33–46.

- Fernandez, S., & Moldogaziev, T. (2011). Empowering public sector employees to improve performance: Does it work? The American Review of Public Administration, 41(1), 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074009355943

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/315098

- Fried, Y., Laurence, G. A., Shirom, A., Melamed, S., Toker, S., Berliner, S., & Shapira, I. (2013). The relationship between job enrichment and abdominal obesity: A longitudinal field study of apparently healthy individuals. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(4), 458–465.

- Gao, J. (2015). Performance measurement and management in the public sector: Some lessons from research evidence. Public Administration and Development, 35(2), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1704

- Gaskin, D. J., & Richard, P. (2012). The economic costs of pain in the United States. The Journal of Pain, 13(8), 715–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009

- Glaser, J., Seubert, C., Hornung, S., & Herbig, B. (2015). The Impact of Learning Demands, Work-Related Resources, and Job Stressors on Creative Performance and Health. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 14(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000127

- Gilin Oore, D. E. B. R. A., Leblanc, D., Day, A., Leiter, M. P., Spence Laschinger, S., H. K., Price, S. L., & Latimer, M. (2010). When respect deteriorates: Incivility as a moderator of the stressor–strain relationship among hospital workers. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(8), 878–888. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01139.x

- Grant, B., & Drew, J. (2017). Local government in Australia. Springer.

- Grant, A. M., & Parker, S. K. (2009). Redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 317–375. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903047327

- Guest, D. E. (2017). Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12139

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2006). Sources of social support and burnout: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1134

- Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

- Han, S., Harold, C. M., Oh, I. S., Kim, J. K., & Agolli, A. (2022). A meta-analysis integrating 20 years of workplace incivility research: Antecedents, consequences, and boundary conditions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(3), 497–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2568

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed). Guilford Press.

- Hershcovis, M. S, & Barling, J. J. (2007). Towards a relational model of workplace aggression. In. Langan-Fox, J., Cooper, C. and R. Klimoski (Eds.), Research Companion to the Dysfunctional Workplace: Management Challenges and Symptoms (pp. 268–285). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In S. Folkman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp.127–147). Oxford University Press.

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

- Holmlund, L., Tinnerholm Ljungberg, H., Bültmann, U., Holmgren, K., & Björk Brämberg, E. (2022). Exploring reasons for sick leave due to common mental disorders from the perspective of employees and managers – what has gender got to do with it? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 17(1), 2054081. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2022.2054081

- Hubert, A. B., & Van Veldhoven, M. (2001). Risk sectors for undesirable behaviour and mobbing. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320143000799

- Holmgreen, L., Tirone, V., Gerhart, J., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2017). Conservation of resources theory. The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice, 2(7), 443–457.

- Humphrey, S. E., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1332–1356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1332

- Hurley, J., Hutchinson, M., Bradbury, J., & Browne, G. (2016). Nexus between preventive bullying, and mental health: Qualitative findings from the experiences of Australian public sector employees. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(1), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12190

- Jacobsen, C. B., & Bøgh Andersen, L. (2017). Leading public service organizations: How to obtain high employee self-efficacy and organizational performance. Public Management Review, 19(2), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1153705

- Jarman, L., Martin, A., Venn, A., Otahal, P., Taylor, R., Teale, B., & Sanderson, K. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in a large and diverse public sector workforce: Baseline results from Partnering Healthy@Work. BMC Public Health, 14(1293), 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-125

- Kabat-Farr, D., Cortina, L. M., & Marchiondo, L. A. (2018). The emotional aftermath of incivility: Anger, guilt, and the role of organizational commitment. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(2), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000045

- Kanat-Maymon, Y., & Reizer, A. (2017). Supervisors’ autonomy support as a predictor of job performance trajectories. Applied Psychology, 66(3), 468–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12094

- Khubchandani, J., & Price, J. H. (2015). Workplace harassment and morbity among US adults: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Community Health, 40(3), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-014-9971-2

- Kifer, Y., Heller, D., Perunovic, W. Q. E., & Galinsky, A. D. (2013). The good life of the powerful: The experience of power and authenticity enhances subjective well-being. Psychological Science, 24(3), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612450891

- Kivimäki, M., Vahtera, J., Thomson, L., Griffiths, A., Cox, T., & Pentti, J. (1997). Psychosocial factors predicting employee sickness absence during economic decline. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 858–872. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.6.858

- Kowalski, T. H., & Loretto, W. (2017). Well-being and HRM in the changing workplace. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(16), 2229–2255. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1345205

- Liu, X., Yang, S., & Yao, Z. (2020). Silent counterattack: The impact of workplace bullying on employee silence. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 572236. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572236

- Lovallo, W. R. (2016). Stress and health: Biological and psychological interactions (3rd ed). Sage.

- Malec, J., Cayner, J. J., Harvey, R. F., & Timming, R. C. (1981). Pain management: Long-term follow-up of an inpatient program. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 62(8), 369–372.

- Marcatto, F., Colautti, L., Larese Filon, F., Luis, O., Di Blas, L., Cavallero, C., & Ferrante, D. (2016). Work-related stress risk factors and health outcomes in public sector employees. Safety Science, 89, 274–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2016.07.003

- McBeth, J., Harkness, E. F., Silman, A. J., & MacFarlane, G. J. (2003). The role of workplace low-level mechanical trauma, posture and environment in the onset of physical widespread pain. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 42(12), 1486–1494. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keg399

- McNamee, P., & Mendolia, S. (2014). The effect of physical pain on life satisfaction: Evidence from Australian data. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 121, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.019

- Melzack, R. (1999). From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain, 82(Supplement 1), S121–S126. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00145-1

- Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321–1339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321

- Nielsen, K., Nielsen, M. B., Ogbonnaya, C., Känsälä, M., Saari, E., & Isaksson, K. (2017). Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 31(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1304463

- Nixon, A. E., Mazzola, J. J., Bauer, J., Krueger, J. R., & Spector, P. E. (2011). Can work make you sick? A meta-analysis of the relationships between job stressors and physical symptoms. Work & Stress, 25(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2011.569175

- North, F., Syme, S. L., Feeney, A., Head, J., Shipley, M. J., & Marmot, M. G. (1993). Explaining socioeconomic differences in sickness absence: The Whitehall II Study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 306(6874), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.306.6874.361

- Park, H. I., Jacob, A. C., Wagner, S. H., & Baiden, M. (2014). Job control and burnout: A meta-analytic test of the Conservation of Resources model. Applied Psychology, 63(4), 607–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12008

- Park, R., & Searcy, D. (2012). Job autonomy as a predictor of mental well-being: The moderating role of quality-competitive environment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(3), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9244-3

- Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Porath, C. L. (2000). Assessing and attacking workplace incivility. Organizational Dynamics, 29(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-2616(00)00019-x

- Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Wegner, J. W. (2001). When workers flout convention: A study of workplace incivility. Human Relations, 54(11), 1387–1419. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267015411001

- Pearson, C., & Porath, C. (2009). The cost of bad behavior: How incivility is damaging your business and what to do about it. Penguin.

- Perry, J. L. (1996). Measuring public service motivation: An assessment of construct reliability and validity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 6(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024303

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Purtle, J., Nelson, K. L., Yang, Y., Langellier, B., Stankov, I., & Roux, A. V. D. (2019). Urban–rural differences in older adult depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(4), 603–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.008

- Rayner, J., & Lawton, A. (2018). Are we being served? Emotional labour in local government in Victoria, Australia. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(3), 360–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500-12282

- Roquelaure, Y., Ha, C., Leclerc, A., Touranchet, A., Sauteron, M., Melchior, M., Imbernon, E., & Goldberg, M. (2006). Epidemiologic surveillance of upper-extremity musculoskeletal disorders in the working population. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 55(5), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22222

- Selenko, E., Mäkikangas, A., Mauno, S., & Kinnunen, U. (2013). How does job insecurity relate to self-reported job performance? Analysing curvilinear associations in a longitudinal sample. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(4), 522–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12020

- Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 456–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109351241

- Thompson, C. A., & Prottas, D. J. (2006). Relationships among organizational family support, job autonomy, perceived control, and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(1), 100–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.100

- Timming, A. R., Notebaert, L., & Carpini, J. A. (2019). From workplace stress to workplace wellness: An assessment of the health and well-being of local government Chief Executive Officers in WA., The University of. Western Australia.

- Tsuno, K., Kawakami, N., Shimazu, A., Shimada, K., Inoue, A., & Leiter, M. P. (2017). Workplace incivility in Japan: Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the modified Work Incivility Scale. Journal of Occupational Health, 59(3), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.16-0196-OA

- Vargas, E. A., Mahalingam, R., & Marshall, R. A. (2021). Witnessed incivility and perceptions of patients and visitors in hospitals. Journal of Patient Experience, 8, 237437352110280. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735211028092

- Wegman, L. A., Hoffman, B. J., Carter, N. T., Twenge, J. M., & Guenole, N. (2018). Placing job characteristics in context: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of changes in job characteristics since 1975. Journal of Management, 44(1), 352–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920631665454

- Wood, S., Daniels, K., & Ogbonnaya, C. (2020). Use of work–nonwork supports and employee well-being: The mediating roles of job demands, job control, supportive management and work–nonwork conflict. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(14), 1793–1824. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1423102

- Wong, C. W., Kwok, C. S., Narain, A., Gulati, M., Mihalidou, A. S., Wu, P., Alasnag, M., Myint, P. K., & Mamas, M. A. (2018). Marital status and risk of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart (British Cardiac Society), 104(23), 1937–1948. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313005

- Yao, J., Lim, S., Guo, C. Y., Ou, A. Y., & Ng, J. W. X. (2022). Experienced incivility in the workplace: A meta-analytical review of its construct validity and nomological network. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(2), 193–220.

- Yao, Z., Luo, J., & Zhang, X. (2020a). Gossip is a fearful thing: The impact of negative workplace gossip on knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(7), 1755–1775. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-04-2020-0264

- Yao, Z., Zhang, X., Luo, J., & Huang, H. (2020b). Offense is the best defense: The impact of workplace bullying on knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(3), 675–695. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-12-2019-0755

- Zhu, H., Lyu, Y., & Ye, Y. (2021). The impact of customer incivility on employees’ family undermining: A conservation of resources perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 38(3), 1061–1083. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-019-09688-8