Abstract

Expatriation significantly influences the career paths of individuals after their international work experience. This study draws on person-environment fit and career construction theories to examine the role of job fit, career adaptability, and expatriate type in shaping both objective and subjective career success. Our 2020 sample comprised 191 expatriates who had worked abroad four to five years prior. This group included both self-initiated and assigned expatriates, as well as repatriates and re-expatriates, providing a broader scope than is typical in expatriation studies. The research reveals that job fit, career adaptability, and expatriate type substantially affect career outcomes. It also identifies that the type of expatriate moderates the relationship between career adaptability and objective career success. Our work extends the applicability of person-environment fit theory and career construction theory within the complex landscape of expatriate careers. The investigation not only deepens our understanding of the factors driving career success post-expatriation but also provides valuable insights to aid the effective management of international careers.

Introduction

Expatriation, where individuals move across national and often also organizational borders, is seen as a highly developmental experience (Mello et al., Citation2023a; Shaffer et al., Citation2012). This type of work is considered more complex and demanding than work in the domestic market (Shin et al., Citation2007) and is classified as high-density (H-D) work (Kraimer et al., Citation2022; Shaffer et al., Citation2012). It significantly influences individuals’ competencies, work interests, and future careers (Dickmann et al., Citation2018; Shaffer et al., Citation2012). The theory of work experience defines density as work that offers a developmental punch of intense experience over time (Tesluk & Jacobs, Citation1998, p.329). As such, H-D work requires expatriates to adapt to new career situations both during and post-expatriation (Guan et al., Citation2019) in order to find the best fit with their new work environments (Chan et al., Citation2015).

The developmental nature of expatriation experiences has prompted interest in understanding the impacts on the careers of different types of individuals post-expatriation (Ellis et al., Citation2020). Existing literature provides evidence of both positive (Ramaswami et al., Citation2016) and negative (Benson & Pattie, Citation2008) career effects. The inconsistency is likely due to most studies not incorporating a diverse array of expatriate types. The types in question include assigned expatriates (AEs), who are sent abroad by their employers, and self-initiated expatriates (SIEs), who seek opportunities abroad on their own initiative (Andresen et al., Citation2020). Our study reports on the career implications of expatriation among a group of individuals who had been expatriates. We include both those who have repatriated back to their home country (i.e. repatriates; Chiang et al., Citation2018) and those who chose to continue their international career with new expatriate work after ending their previous sojourn abroad (i.e. re-expatriates; Ho et al., Citation2016). Therefore, our research looks at the career outcomes of both AEs and SIEs regardless of whether they have repatriated or continued their career abroad in a different job. Consistent with the career literature (e.g. Ng et al., Citation2005), we distinguish between objective (i.e. observable career achievements) and subjective (i.e. subjective evaluations of career outcomes) career success (CS). We assess the career impact four to five years after individuals have concluded their expatriate job, originally held in 2015 or 2016. We refer to this phase as ‘post-expatriation,’ irrespective of where they lived at the time of data collection.

Our study employs person-environment fit theory (Ehrhart, Citation2006) alongside career construction theory (Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012) as conceptual frameworks to navigate the complexities of expatriate CS. These theories have been identified as having the potential to guide future research on careers (Mello et al., Citation2023a; Spurk et al., Citation2019). First, our study applies person-environment fit theory to the context of expatriate CS (Lauring & Selmer, Citation2018), broadening its scope beyond traditional domestic settings and beyond merely subjective career outcomes (Guan et al., Citation2021) to include expatriates’ international work experiences. International career paths can be highly complex and varied and include many location and work patterns (Baruch et al., Citation2013). Therefore, our perspective is especially pertinent as it includes expatriates undergoing phases of repatriation or re-expatriation. Their work patterns are often characterized by career expectations elevated by their international learning experiences (Suutari et al., Citation2018). Therefore, securing roles that align with the competencies cultivated during their work abroad can significantly influence both their subjective CS (Oleškevičiūtė et al., Citation2022; Eugenia Sánchez Vidal et al., Citation2007) and their objective CS in the new position (Mello et al., Citation2023a). Furthermore, our methodological approach contributes by applying robust quantitative methods to validate these theoretical constructs. Consequently, we enhance their empirical rigour and broaden their applicability across diverse expatriate types and career paths.

Second, career construction theory emphasizes the role of expatriates as proactive agents managing their career transitions. This theory introduces the concept of career adaptability, a construct that offers a valuable lens on variations in CS (Spurk et al., Citation2019), including among expatriates (Jannesari & Sullivan, Citation2019). The theory acknowledges the agency of individuals in navigating their career transitions (Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012), emphasizing the proactive role they play in securing job fit (Hirschi et al., Citation2015). As H-D global work necessitates cognitive flexibility, expatriates must demonstrate adaptability as they transition across organizational and national boundaries (Shaffer et al., Citation2012). Weaving the element of career adaptability into the study underlines the importance of individual efforts to address challenges and leverage the opportunities inherent in H-D global work (Jannesari & Sullivan, Citation2019).

Third, we analyse whether the two expatriate types, AEs and SIEs, differ in their CS post-expatriation. Both AEs and SIEs undertake H-D global work, but their career trajectories may differ as SIEs initiate their expatriation while AEs are sent abroad by their employer (Suutari et al., Citation2018). Given that SIEs generally exhibit more proactivity than AEs in initiating and preparing for their expatriations (Andresen et al., Citation2020), we leverage insights from the proactivity literature (Parker & Collins, Citation2010) to understand the differences in CS of these two types of expatriates. This advance is noteworthy because empirical studies on SIE and its career impact have been criticized for lacking theoretical grounding (Mello et al., Citation2023a; Suutari et al., Citation2018).

Finally, drawing on the proactive career literature, we propose that the career adaptability requirements for SIEs and AEs differ during career transitions following international work. Studies highlight that AEs and SIEs differ in the degree of proactivity they bring to their roles (Andresen et al., Citation2020). This variation stems from SIEs lacking corporate support during career transitions (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022). Therefore, we investigate whether the type of expatriate serves as a moderating factor in the relationship between career adaptability and CS.

The overall objective of the present study is to investigate how job fit with the new role, career adaptability, and expatriate type influence the objective and subjective CS of expatriates following their H-D work experience abroad. We contribute to understanding the CS of individuals undertaking global work in several ways. Firstly, while job fit is an essential antecedent of CS in domestic careers (e.g., Erdogan & Bauer, Citation2005), its role in the context of expatriate careers has not been sufficiently examined. Our quantitative study employs the theoretical construct of job fit to explicate the CS of expatriates. While general career theory has previously established the relationship between job fit and subjective CS (Erdogan & Bauer, Citation2005), our study contributes by extending these insights to encompass objective CS within the expatriation context. Traditional studies in this area have often been small-scale, qualitative, and focused solely on subjective CS (e.g., Makkonen, Citation2015).

In contrast, this research encompasses a broader range of expatriate types and career paths. We argue that the highly developmental nature of expatriate work experience amplifies the relevance of job fit, not just for subjective but also for objective CS. Our findings furnish new empirical support for this line of thought. Second, our study offers empirical evidence on the importance of career adaptability in the CS of expatriates after their foreign work experience. Expatriates must first adapt to their expatriate position and, later, to a new job back home or in another international location. We explore how career adaptability leads to enhanced objective and subjective CS (Chiang et al., Citation2018; Ho et al., Citation2016), responding to calls for further research by academics such as Rudolph et al. (Citation2017). Third, our study represents a pioneering effort to apply a theoretical foundation, specifically career construction theory, to investigate the differences in CS between AEs and SIEs following their expatriation experiences. Finally, our study also shows that career adaptability indirectly influences expatriates’ CS when moderated by the expatriate type, a finding that contributes to both general and international career research.

Conceptual framework and hypothesis development

In the dynamic landscape of global careers, understanding expatriates’ objective and subjective CS requires a multifaceted theoretical lens. This study draws upon person-environment fit and career construction theories to frame its investigation. Person-environment fit theory posits that the alignment between people’s characteristics and their occupational environment is crucial for career development and satisfaction (Edwards, Citation1991). This alignment is particularly pertinent for expatriates whose career trajectories are often shaped by complex interactions in diverse cultural and professional settings. Career construction theory complements this approach by adding insights into how individuals construct their careers by making meaning out of their work experiences and adapting to changing environments (Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012). By integrating these theories, our conceptual framework aims to explore how expatriates navigate and construct their careers in alignment with the evolving demands of global work environments.

Career success of expatriates

Researchers have measured CS using objective factors such as salary (Spurk et al., Citation2019), promotions (Kraimer et al., Citation2009), and job responsibility development (Breitenmoser et al.,Citation2018). Conversely, subjective CS has been assessed using measures like career satisfaction (Shaffer et al., Citation2012) or perceived marketability (Suutari et al., Citation2018).

We employ job responsibility development as a more comprehensive measure of objective CS, incorporating both vertical (changes in hierarchical positions) and horizontal (changes in responsibility levels) perspectives, both of which are significant post-expatriation (Breitenmoser et al., Citation2018). This broader perspective aligns with the literature suggesting that hierarchical position and project responsibility development together offer a more nuanced understanding of an individual’s career progress (Breitenmoser et al., Citation2018; Ng et al., Citation2005; Shaffer et al., Citation2012). This dual approach aligns with the objective CS criteria outlined by Arthur et al. (Citation2005) and Gunz and Heslin (Citation2005), which emphasize observable, standardized measures that resonate with broader societal norms. Both promotions and expansions of responsibilities are concrete decisions made by the organization. The outcomes are visible in terms of positions and responsibility areas in the organization. Moreover, we focus on career satisfaction as a subjective CS measure, assessing expatriates’ satisfaction with their career progress with reference to career goals, income level, advancement, and skill development (Greenhaus et al., Citation1990).

Interest in the CS of expatriates has been increasing. Expatriate work is a form of H-D global work (Shaffer et al., Citation2012) offering extensive development opportunities and typically has considerable consequences for a person’s career (Suutari et al., Citation2018). The theory of work experience suggests that employees learn through the density of work experience rather than the time spent in their jobs (Tesluk & Jacobs, Citation1998). Accordingly, this theory highlights the importance of the developmental punch stemming from the challenges people face in their roles (Quińones et al., Citation1995; Tesluk & Jacobs, Citation1998). Researchers have advocated further investigation of such developmental challenges (Akkan et al., Citation2022).

Research to date has queried what makes global work a form of H-D work (e.g., Akkan et al., Citation2022). First, H-D global work involves international relocation, which triggers an adjustment of expatriate thought patterns and scripts to effectively interact with people and adapt to situational demands across cultures (Shaffer et al., Citation2012). The work role requirements also disrupt or interfere with employees’ usual activities and routines outside work (Kraimer et al., Citation2022). Subsequent research suggests that substantial task challenges and autonomy are typical characteristics of H-D global work (Mello et al., Citation2023a). That finding corroborates that expatriates often assume greater task responsibilities than in their previous jobs, while having a higher level of autonomy and having fewer support structures; impacting individuals considerably (Bossard & Peterson, Citation2005; Dickmann et al., Citation2018).

Expatriates’ H-D work experiences are likely to boost their perceived competence, their interest in new career challenges (Shaffer et al., Citation2012) and to elevate their career expectations (Dowling et al., Citation2013). In turn, changes to work responsibilities, social relations, and work environments during transitions may also foster career risks (Guan et al., Citation2019). Expatriates can struggle to find sufficiently challenging jobs after expatriation (Kraimer et al., Citation2012; Suutari & Brewster, Citation2003) or to apply the competencies acquired when they were abroad (Oleškevičiūtė et al., 2022). Overall, expatriation can have major career implications for expatriates (Kraimer et al., Citation2022).

The evidence regarding the CS of expatriates after working abroad is limited and broadly focused on AEs who have repatriated. Studies report mixed findings. There is very little evidence on objective CS concerning measures such as job offers and job responsibility development (Mello et al., Citation2023a). Further research is needed to fully understand the career impacts of expatriation. In particular, research evidence relating to SIEs (Suutari et al., Citation2018) remains very limited.

Antecedents of expatriate career success

Understanding expatriate CS is complex and multifaceted. Theories and related antecedents adopted to study the phenomenon vary extensively in general (Spurk et al., Citation2019) and even within the international career environment (Mello et al., Citation2023a). Prior research illuminates various antecedents impacting expatriates’ career trajectories, ranging from personal resources (e.g., human capital; Ramaswami et al., Citation2016) and individual agency (e.g., self-directed career management; Breitenmoser et al., Citation2018) to environmental resources (e.g., organizational support; Dickmann & Doherty, Citation2010) and contextual resources (e.g., cultural distance; Schmid & Wurster, Citation2017). However, theoretical approaches that focus on how the interplay between individuals and the environment affects CS have not been thoroughly explored in the context of H-D global work. Two promising theories connected with this are person-environment fit and career construction theory (Mello et al., Citation2023a).

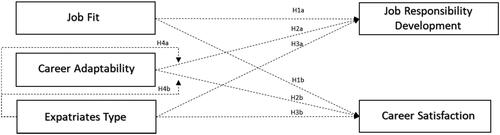

Accordingly, this study delves deeper into the nuanced elements of job fit, career adaptability, and expatriate type as pivotal factors in shaping expatriates’ job responsibility development and career satisfaction post-expatriation. illustrates our conceptual framework, which integrates these antecedents with the broader spectrum of influences on expatriate CS.

The job fit of expatriates after working abroad

When expatriates have completed H-D work abroad, it is important for their careers that they expect to find subsequent jobs reflecting that experience. A suitable job would be one in which there is a fit between their new competencies and the job (Eugenia Sánchez Vidal et al., Citation2007) or even their career goals (Lazarova et al., Citation2021). That is the case whether the next job is at home or abroad (Suutari et al., Citation2018). The concept of fit features in the literature on CS (e.g., Erdogan & Bauer, Citation2005) but has seldom been used in empirical research on expatriates’ career experiences and success (Haslberger & Dickmann, Citation2016). The theory of person-environment fit is based on the premise that a person and environment interact, and it has traditionally been applied in relation to job fit (Ehrhart, Citation2006), focusing on a person’s competencies and the requirements of their job (Aycan, Citation2005). Employees strive to secure a fit with their own perceived competencies, job demands, and job resources (Greguras & Diefendorff, Citation2009). The evidence relating to AEs indicates that companies are not particularly successful at arranging suitable jobs following repatriation (Suutari et al., Citation2018). For their part, SIEs will typically need to find a new employer and role upon repatriation (Andresen et al., Citation2014). These changes might impact expatriates’ CS, as job fit can either promote or obstruct the utilization of resources, subsequently impacting performance and outcomes (Bretz et al., Citation1994).

The theory of person-environment fit suggests that expatriates with the best job fit will extract the most benefit from career competencies acquired abroad (Guan et al., Citation2021). Job fit is considered a wise career choice (Tinsley, Citation2000) and a situation employers should target. Job fit is highly relevant in the context of expatriation owing to the H-D nature of global work and the fact that expatriates must adjust to working in different institutional contexts (Andresen et al., Citation2022). When individuals’ strengths fit the requirements of roles (Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004), the situation contributes to subjective CS (Peltokorpi & Froese, Citation2014). Accordingly, we expect job fit after expatriation to lead to greater career satisfaction. Job fit also affects overall performance, effectiveness (Zimmerman, Citation2008), and career progress (Lyness & Heilman, Citation2006). We propose:

Hypothesis 1: A high degree of job fit positively impacts (a) expatriates’ job responsibility development and (b) expatriates’ career satisfaction.

The career adaptability of expatriates

To succeed in H-D work and find suitable career options after expatriation, individuals must acquire the competencies to adapt to career development requirements and employment demands (Benson & Pattie, Citation2008). We selected a career adaptability measure to reveal the degree of adaptability expatriates require to cope with their career transitions (Mello et al., Citation2023a). It is also a key element of career construction theory (Savickas, Citation2005). Career adaptability encompasses the constellation of behaviours, competencies, and attitudes individuals deploy ‘in fitting themselves into work that suits them’ (Savickas, Citation2005, p. 45). Career construction theory (Savickas, Citation2005) holds that career adaptability consists of four aspects: career concern (considering future possibilities and preparing for them), career control (purposeful decision-making and conscientious action), career curiosity (investigating various situations and roles), and career confidence (dealing with barriers and problems). While job fit emphasizes the final fit achieved, career adaptability stresses the role of individual activity in achieving that degree of fit (Haenggli & Hirschi, Citation2020). Adaptive capability refers to individuals’ capacity to adapt to new work demands in different environments and diverse groups (Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012).

Career construction theory also indicates that career adaptability will enhance CS (Haenggli & Hirschi, Citation2020). Empirical evidence suggests that career adaptability results in successful career transitions (Brown et al., Citation2012) and positive career outcomes (Rudolph et al., Citation2017). The findings concentrate on subjective CS (Rudolph et al., Citation2017), such as perceived employability (de Guzman & Choi, Citation2013) and career satisfaction (Chan & Mai, Citation2015). A recent meta-analysis concluded that there is very little evidence of the connections between career adaptability and objective CS, which invites further research (Rudolph et al., Citation2017).

Research on career adaptability among expatriates is even scarcer (Jannesari & Sullivan, Citation2019). The H-D work of expatriates often requires them to build their careers with less organizational support and to find jobs that will satisfy them in the future (Guan et al., Citation2021). They must also be able to adapt to different kinds of jobs after expatriation, regardless of whether they return home or move to a new job abroad. Accordingly, we expect expatriates would benefit from career adaptability after their international work.

Career adaptability has recently been studied in connection with SIE performance (Jannesari & Sullivan, Citation2019) and their adjustment while abroad (AlMemari et al., Citation2023; Ocampo et al., Citation2022). However, our study focuses on the role of career adaptability in job responsibility development and career satisfaction after expatriation. Building on career construction theory, we propose:

Hypothesis 2: A high degree of career adaptability positively impacts (a) expatriates’ job responsibility development and (b) expatriates’ career satisfaction.

Expatriate type

Both AEs and SIEs undertake H-D work abroad, but their career trajectories differ (Suutari et al., Citation2018). The primary distinction between the two types of expatriates is that SIEs initiate their own expatriation, while AEs are sent abroad by their employers (Andresen et al., Citation2020). Given this core difference, we use the proactivity literature (Parker & Collins, Citation2010) to explain why and how individuals’ proactive career behaviours contribute to their CS.

Proactive career behaviours are theoretically linked to career construct theory (Spurk et al., Citation2020) that explains how individuals construct their careers and derive meaning from their work experiences, enabling them to comprehend their personal values, motivations, and goals (Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012). Proactive career behaviours can be defined as ‘the degree to which somebody is proactively developing his or her career as expressed by diverse career behaviours’ (Hirschi et al., Citation2014, p. 577). Those behaviours are represented by three core components: taking control, anticipation, and information retrieval (Parker & Collins, Citation2010; Smale et al., Citation2019).

Taking control involves individuals exercising autonomy in managing their careers. Anticipation denotes proactive action in response to future situations, and information retrieval refers to obtaining relevant career information and resources (Smale et al., Citation2019). Typically, SIEs are proactive in taking control of their careers by preparing for an international move, exploring job opportunities, seeking the necessary resources to facilitate expatriation, and moving abroad. Researchers (Smale et al., Citation2019; Van den Broeck et al., Citation2016) have described such proactive behaviour as volitional, self-endorsed, and driven by a basic need for autonomy. Consequently, this behaviour could be expected to have significant consequences for the career of an SIE (Andresen et al., Citation2020).

Scholars argue that the autonomy inherent in controlling their career leads individuals to a subjective perception of personal success, akin to thinking, ‘I am doing what I know is best for me’ (Smale et al., Citation2019). In line with that notion, feeling in control of one’s career has been associated with higher levels of subjective CS (Raabe et al., Citation2007). Accordingly, their proactive behaviour may result in SIEs having a higher level of satisfaction than AEs. The latter are subject to management by their organization during the expatriation process (Smale et al., Citation2019). Therefore, we expect SIEs to have greater career satisfaction than AEs after expatriation. Scholars argue that having the personal initiative and autonomy to plan and manage their career (taking control) helps individuals improve job performance and, consequently, objective CS (Tornau & Frese, Citation2013). The idea is supported by findings that individual career planning and career management are associated with higher levels of objective CS (Mello et al., Citation2023a), more so than in organizational career management (Breitenmoser et al., Citation2018). Therefore, we expect SIEs to have a higher degree of job responsibility development as a measure of objective CS than AEs do.

The empirical findings of research among expatriates are conflicting. Studies focusing exclusively on SIEs or AEs report expatriation can exert both a positive and negative influence on CS (see Mello et al., Citation2023a). In addition, the few studies comparing AEs’ and SIEs’ CS after expatriation found few significant differences (e.g., Suutari et al., Citation2018). This study limits the investigation to the original postulation of the proactive literature, which argues that SIEs’ CS can benefit from their more pronounced autonomy and freedom in relation to career decisions. Hence, we propose:

Hypothesis 3: People whose international work experience was gained as an SIE will have higher levels of (a) job responsibility development and (b) career satisfaction after expatriation than people whose international work experience was gained as an AE.

The moderation role of expatriate type between career adaptability and career success

All expatriates benefit from career adaptability during their international careers. However, SIEs are more reliant on career adaptability due to their lack of organizational attachment and support (Chen & Shaffer, Citation2017) and also the increased likelihood of substantial job and employer changes (Andresen et al., Citation2020). As a result, SIEs foster career adaptability when evaluating career options (career concern), making career-related decisions (career control), exploring job and career-related opportunities (career curiosity), and overcoming barriers (career confidence).

This implies that for SIEs career adaptability may play a more significant role in coping with the increased career risks associated with cross-border transitions than it does for AEs (Andresen et al., Citation2020). Drawing from the proactive literature, we contend that career adaptability is even more central to job responsibility development and the career satisfaction of SIEs than AEs. The basis for this perspective lies in the fact that SIEs initiate their international moves proactively and are thus aware that they are likely to enjoy less organizational support than AEs during and after their expatriation. We propose:

Hypothesis 4: Expatriate type moderates the positive relationship between career adaptability and (a) job responsibility development and (b) career satisfaction such that the relationship is stronger for SIEs than AEs.

Method

Sample

The data were collected through an internet survey among expatriate members of two Finnish unions: The Association of Business Schools Graduates and the Union of Academic Engineers and Architects. Since union membership figures in Nordic countries are exceptionally high, this group likely represents almost all Finnish graduates working abroad in these fields (Suutari et al., Citation2018). The unions were able to identify and survey individuals working abroad in 2015 and 2016, and we then sent them our questionnaire in 2020. That ability is an important benefit of surveys directed through this data source as other potential sources, such as employer records or websites, are less likely to have contact details of people who have left their employer or changed countries.

The survey was circulated to 422 individuals. After reminders, 219 survey responses were returned (51.90%). Next, we excluded 80 respondents as they were still in the same country and job, meaning we could not analyse their career paths following changes in their work. We were left with a total of 139 respondents. Seeking to expand the database, we used the online communication channel of the union to invite additional members who had previous expatriate experience to participate in the study. We also checked that the CS of expatriates of these subsamples was the same. The method extended the sample by 62 respondents. Finally, we excluded 11 respondents due to missing data. summarizes that the study attracted 191 respondents (83 AEs and 108 SIEs).

Table 1. Background of the sample (N = 191).

Measures

Our study relies on validated multi-item scales. First, we divided questionnaire sections when entering scales for predictors and outcomes to mitigate the effects of common method variance. Furthermore, we guaranteed respondents anonymity and encouraged them to be honest and spontaneous when replying (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Dependent variables

Breitenmoser et al. (Citation2018) operationalized the job responsibility development scale drawing from the scale used by Kraimer et al. (Citation2009), which emphasizes hierarchical positions. Additionally, they incorporated recommendations from Shaffer et al. (Citation2012) to include a more horizontal perspective on objective CS, focusing on the degree of responsibility associated with tasks or projects. This dual approach enables a comprehensive assessment of job responsibility development, integrating both vertical and horizontal perspectives of objective CS. To compare the career impacts of international work experience post-expatriation, we asked respondents to evaluate their job responsibilities before and after expatriation using this scale (cf. Mäkelä & Suutari, Citation2009; Suutari & Brewster, Citation2003). Our adaptation of the original two items is: ‘Compared to your position before your job abroad (in 2015/16), is your current position a (1) demotion…(5) promotion?’ and ‘Compared to your project responsibility before your job abroad (2015/16), do the projects you are currently responsible for represent a (1) reduction in responsibility…(5) an increase in responsibility?’ The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.911.

We elicited expatriates’ perceptions of subjective career satisfaction, measured with the five-item career satisfaction scale by Greenhaus et al. (Citation1990). A sample item is: ‘The progress I have made toward meeting my goals for advancement’. All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.901).

Independent variables

The demands–abilities fit scale developed by Cable and DeRue (Citation2002) measures job fit based on three items. We asked respondents to state to what extent they felt the skills and abilities developed during their work abroad (2015/16) meet the requirements of their current job on a scale anchored with not at all (1) and completely (5). Amongst the items were: ‘The match was very good between the demands of my current job and my personal skills’, ‘My abilities and training were a good fit with the requirements of my current job’, and ‘My personal abilities provided a good match with the demands that my current job places on me’. The items were measured on 5-point Likert scales (Cronbach’s alpha 0.920).

We used the career adapt-ability scale (CAAS-SF) to measure career adaptability, combining the items to yield a total score (Maggiori et al., Citation2017). When replying, participants were guided by the following description and related question: ‘Different people use different strengths to build their careers. No one is good at everything; each of us emphasizes some strengths more than others. Please rate how strongly you have developed each of the following abilities using the scale below’. Sample items included ‘Thinking about what my future will be like’ (Concern), ‘Making decisions by myself’ (Control), ‘Observing different ways of doing things’ (Curiosity) and ‘Overcoming obstacles’ (Confidence). All items were measured on 5-point Likert scales (Cronbach’s alpha 0.706). We categorized the respondents into two distinct types of expatriates: Assigned Expatriates (AEs) and Self-Initiated Expatriates (SIEs). Participants were asked to describe whether their expatriation was initiated by their employer (AEs) or themselves (SIEs). For the purpose of coding, SIEs were coded 0 and AEs 1.

Control variables

We controlled for age, gender, and career path. First, the extant literature indicates that age has a negative influence on both promotions and perceived external employability (Suutari et al., Citation2018), as well as on home-country marketability (Mäkelä et al., Citation2015). Age was controlled for as a continuous variable. Gender has an impact on the CS of expatriates as there is evidence that women experience unique barriers during international career transitions (Culpan & Wright, Citation2002; Shortland & Perkins, Citation2022). For instance, women managers are less satisfied with their careers after expatriation than men (Ren et al., Citation2013). In addition, studies have suggested that women may choose to self-expatriate to ‘redress the disadvantage they face in managerial career advancement’ (Tharenou, Citation2010). Men were coded 0 and women 1. Finally, to enhance the precision of our findings on CS post-expatriation, we incorporated career path as a control variable, differentiating between expatriates who have repatriated and those who have continued their international careers through accepting new expatriate jobs (i.e. re-expatriates). This distinction is crucial, as existing literature suggests that CS may vary between these groups (Baruch et al., Citation2016; Mello et al., Citation2023b). In our analysis, repatriates were coded as 0 and re-expatriates as 1. Controlling for career path meant we could assess whether the impacts of job fit and the proactive behaviours of expatriates, as demonstrated through their career adaptability, influence their CS independently of their career trajectory post-expatriation.

Analysis

First, we provided a descriptive analysis of the study variables and conducted CFA to check if the model fits the data. Based on the standard suggestions (e.g. Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), the model fit is acceptable with CFI =0.90/0.95, TLI =0.90/0.95, RMSEA <0.06/0.08, and SRMR <0.08. Due to negative disturbance variance, we constrained the disturbance of confidence to .001. Then, following the validation article of the CAAS-SF (Maggiori et al., Citation2017), we allowed two measurement residuals of curiosity items (‘I investigate options before making a choice’ and ‘observing different ways of doing things’) and two measurement residuals of confidence’s items (‘taking care to do things well’ and ‘working up to my ability’) to correlate. The fit indices of the CFA with X2= 337.98, df = 196, p < 0.001, CFI =0.92, TLI =0.91, RMSEA = 0.06, and SRMR =0.06 indicate an acceptable fit. Missing data were handled by using listwise deletion, and there were n = 11 missing responses.

In order to assess discriminant validity, we examined the 95% confidence intervals of the correlations between latent variables in the CFA model. No discriminant validity problems were observed, as the upper interval estimate was below 0.8 between all variables (Rönkkö & Cho, Citation2022).

Then, we tested for common method bias using the marker variables technique (Simmering et al., Citation2015). Remote work satisfaction was used as the marker variable because it is likely to demonstrate similar biasing response tendencies as our other study variables. The model comparison showed no common method bias as the model with marker variable associations to the indicators of other variables was not significantly different (p = 0.30) from the model without associations from the marker variable to the indicators. Additionally, most factor loadings related to the marker variable were non-significant. Finally, we performed multicollinearity tests (tolerance and VIF) to confirm that multicollinearity was not present in the statistical model. All independent variables of our regression model showed tolerance levels higher than 0.10 and VIF lower than 10, in line with the recommendations of Hair et al. (Citation1998).

Given the constraints of our sample size and the focus on direct relationships between variables, we opted for multiple regression analysis to test our research hypotheses. This choice aligns with previous research (e.g., Booth et al., Citation2020) and ensures robust and interpretable results. Lastly, concerning the moderated regression, we included only the indirect effects of career adaptability on CS moderated by expatriate type in the model. However, we excluded other indirect effects as we tested to confirm expatriate type did not moderate the relationship between job fit and career satisfaction. Continuous composite variables were standardized prior to analysis to obtain standardized estimates and also to reduce the multicollinearity between variables. Testing for CFA and CMB relied on MPlus (version 8.6; Muthén & Muthén, Citation1999) software, and multiple regression analysis was performed using R (version 4.3.1; R Core Team, Citation2024).

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between study variables are presented in .

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations of study variables (N = 191).

The results are presented in .

Table 3. Regression results for hypothesized relationships (N = 191).

Starting with the control variables, we found that age had a negative influence on the job responsibility development of expatriates; in other words, the older the expatriates, the lower their job responsibility development (β= −0.31, p < 0.001). Interestingly, there were no differences with regard to gender, though such differences in CS are reported in several studies. It may be that as Finnish society is renowned for its gender equality (Stierncreutz & Tienari, Citation2023), the gender differences in CS do not appear as clearly as in some other countries. Similarly, the career type had no significant impact.

Turning to Hypothesis 1, we anticipated a higher degree of job fit would positively influence expatriates’ (1a) job responsibility development and (1b) career satisfaction. The data confirmed the expectation and showed job fit significantly affects both job responsibility development (β = 0.41 p < 0.001) and career satisfaction (β = 0.43 p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 received full support.

In Hypothesis 2, we suggested that increased career adaptability would positively impact (2a) expatriates’ job responsibility development and (2b) career satisfaction. Contrary to our expectations, our findings indicated that career adaptability only significantly influenced career satisfaction (β = 0.15, p = 0.047), with no discernible effect on expatriates’ job responsibility development. Consequently, we only found support for Hypothesis 2b.

Shifting to Hypothesis 3, we proposed that individuals with international work experience as SIEs would demonstrate greater (3a) job responsibility development and (3b) career satisfaction than those who had been AEs. The data, however, revealed that while SIEs had higher levels of career satisfaction than AEs (β = 0.34, p = 0.011), there was no significant difference in job responsibility development between the two groups. Hence, support was found only for Hypothesis 3b.

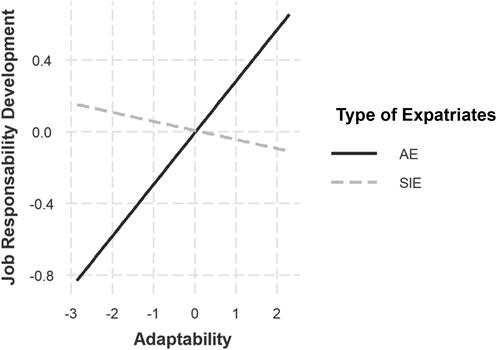

Finally, Hypothesis 4 suggested that expatriate type would moderate the relationship between career adaptability and CS, predicting that increased career adaptability would more strongly relate to (4a) job responsibility development and (4b) career satisfaction among SIEs than among AEs. Our findings showed that expatriate type did indeed moderate the relationship between career adaptability and job responsibility development (β = 0.34, p = 0.013) but not the relationship between career adaptability and career satisfaction. Unexpectedly, the observed moderation did not align with our predictions, leading to the rejection of Hypothesis 4. As illustrates, AEs displayed lower job responsibility development than SIEs at low career adaptability levels. However, when career adaptability was high, AEs achieved greater job responsibility development than SIEs. We extended the exploration of this significant interaction by plotting the relationship between career adaptability and job responsibility development separately for SIEs and AEs. The results revealed that career adaptability was significantly associated with job responsibility development for AEs (β = 0.29 p = 0.016) but not SIEs. The finding suggests that career adaptability influenced the job responsibility development of AEs but not SIEs.

Discussion

This study explores the influence of job fit, career adaptability, and expatriate type on expatriates’ job responsibility development and career satisfaction after international work experiences. Our research emphasizes the outcomes and diverse career trajectories that expatriates may experience, areas that remain underexamined and under-theorized, particularly within the frameworks of person-environment fit theory and career construction theory. These gaps are especially pertinent in the expatriate context (Mello et al., Citation2023a). Our empirical results reveal that the selected antecedents explain a significant proportion (32%) of objective and subjective CS post-expatriation. Furthermore, we delve into the moderating role of expatriate type in the relationship between career adaptability and job responsibility development as a measure of objective CS.

Theoretical and empirical contributions

Our study makes several contributions to the existing body of knowledge. Firstly, while prior research using person-environment fit theory has often focused narrowly on subjective career outcomes (e.g., Bossard & Peterson, Citation2005; Makkonen, Citation2015), our study broadens the scope by incorporating both objective and subjective measures of CS. Specifically, the study sheds light on the significant role that job fit plays in CS, an observation that is particularly pertinent for expatriates. Notably, as expatriates accumulate significant levels of career capital through international work experience (Dickmann et al., Citation2018), our findings suggest that aligning this enhanced career capital with appropriate job opportunities has implications for both objective and subjective aspects of CS. Our research stands out for its robust quantitative methodology and inclusion of a diverse sample of expatriate types, such as SIEs and re-expatriates, thereby further validating the applicability of person-environment fit theory to a broader array of expatriate experiences.

Secondly, our study significantly extends the literature by addressing a relatively underexplored aspect: the implications of career adaptability for expatriates’ CS across various career paths and expatriate types after expatriation. Previous research has been limited in scope, focusing mainly on immediate outcomes or limited aspects of expatriate careers (Suutari et al., Citation2018). Our novel approach adds much-needed depth to this conversation by delving into the complex trajectories expatriates experience post-expatriation. Theoretically, our findings enrich career construction theory by elucidating the role of adaptability in these diverse career paths. We respond to calls for more empirical studies to focus on adaptability, especially in later career stages (Rudolph et al., Citation2017), revealing that adaptability becomes increasingly important in shaping subjective CS, particularly career satisfaction, after expatriation.

While prior research has primarily discussed adaptability in domestic contexts (Spurk et al., Citation2019), with findings mostly indicating connections with subjective CS, significant connections with objective CS have rarely been reported (Rudolph et al., Citation2017). Given the unique challenges and opportunities presented by international careers, we suggest that the role of career adaptability could be more pronounced in such settings, potentially influencing both subjective and objective CS. Intriguingly, our data did not confirm a direct relationship between career adaptability and objective CS, specifically in terms of job responsibility development. This unexpected result, although aligning with findings from Rudolph et al. (Citation2017), warrants further reflection.

In both domestic and international career contexts, career adaptability is consistently linked to subjective CS but not objective CS. The strong connection between career adaptability and career satisfaction may be attributed to the fact that both constructs are fundamentally individual and internal. Career adaptability is defined as an internal ‘psychosocial construct that denotes an individual’s resources for coping with current and anticipated tasks, transitions, and trauma in their occupational roles’ (Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012, p. 662). Meanwhile, subjective CS refers to an individual’s internal evaluation and experience of achieving personally meaningful career outcomes, with career satisfaction serving as a prime example of such outcomes (Ng et al., Citation2005; Spurk et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it appears that internal resources, such as career adaptability, are essential influencers of career outcomes, such as career satisfaction, that result from internal processes. However, these internal resources do not necessarily lead directly to objective CS, which is determined by many external factors that are beyond individuals’ control. Nonetheless, an indirect relationship was observed between career adaptability and objective CS, moderated by the type of expatriate, adding a layer of complexity to our understanding. As existing empirical data on this relationship are limited (Rudolph et al., Citation2017), our study could catalyse further investigations.

Thirdly, our study addresses a critical gap in the literature by offering a theoretical framework specifically tailored for empirical investigation into the career impacts of international work experiences, differentiating between AEs and SIEs. While scholars such as Lauring and Selmer (Citation2018) have noted these distinctions, the field has yet to produce empirical evidence rooted in a theoretical framework that explicitly addresses the career outcomes between these two groups post-expatriation. Bridging this gap, we draw upon career construction theory and proactivity literature (Spurk et al., Citation2020) to underscore the significance of proactive career behaviour in determining the CS of both AEs and SIEs. Empirically, our results align with the proactivity literature (Smale et al., Citation2019), revealing that SIEs experience higher levels of subjective CS when assessed via career satisfaction. However, contrary to expectations, SIEs did not outperform AEs in objective CS, as measured by job responsibility development. They did, however, match AEs in this regard, an observation consistent with prior research on promotions post-expatriation (Suutari et al., Citation2018).

The implications of these findings are twofold and serve as a call to re-evaluate prevailing assumptions in the literature. First, our research challenges existing perspectives that tend to overly emphasize limitations on SIEs’ CS (Suutari et al., Citation2018). Existing research is predominantly qualitative and specific to certain contexts (e.g., Makkonen, Citation2015), somewhat restricting its generalizability. It is, therefore, pivotal to acknowledge the particular context and temporal dimension in examining CS (Andresen et al., Citation2020). For example, upon repatriation, SIEs may confront barriers to reintegration within their domestic job markets, mainly attributable to the absence of organizational support and structured employment arrangements.

Nonetheless, such challenges do not negate the likelihood of SIEs subsequently capitalizing on the benefits accumulated from their prior international work experience (Begley et al., Citation2008; Mello et al., Citation2023b). Moreover, for those electing to continue their international careers, initial conditions and career advancements may closely align with those experienced by AEs. Secondly, elevated levels of career satisfaction amongst SIEs indicate a proactive approach to career management, distinguishing them from AEs. This divergence not only corroborates the empirical findings of the present study but also paves the way for future academic investigations.

Finally, the current study advances existing literature by being the first to identify a moderating effect of expatriate type—AEs versus SIEs—on the relationship between career adaptability and job responsibility development. While research exploring the linkage between career adaptability and objective CS is limited (Rudolph et al., Citation2017), our results reveal that career adaptability positively correlates with job responsibility development solely among AEs. This divergence raises the question: Why does career adaptability not relate to job responsibility development among SIEs? A plausible explanation could be that the heightened proactivity exhibited by SIEs reduces their reliance on adaptability. An SIE is likely to engage in anticipatory actions, proactively seek resources and engage in continuous learning before the need for adaptation arises (Andresen et al., Citation2020). In contrast, AEs often depend on organizational support, a resource frequently lacking in post-expatriation career planning (Chiang et al., Citation2018; Kraimer et al., Citation2009). Consequently, career adaptability—a resource employed following critical incidents (Haenggli & Hirschi, Citation2020) –emerges as more vital for AEs, who generally exhibit less proactive career behaviour.

Additionally, it may also be that the CS of SIEs may be more influenced by external situational factors, such as the domestic or international job markets, than by their own proactive career behaviour. This finding contradicts the existing literature, which posits proactive behaviour is salient in such contexts (Smale et al., Citation2019; Spurk et al., Citation2020). Our results did not establish a positive correlation between enhanced career adaptability and objective CS for SIEs, thereby corroborating the notion that CS is context-dependent and may be influenced more by structural than by agentic factors (Andresen et al., Citation2022). Given the heterogeneous backgrounds of SIEs, a group encompassing both young graduates and those seeking employment abroad due to domestic unemployment, our findings imply that the career impact of international experience on job responsibility development may be less straightforward for SIEs than for more experienced AEs.

Limitations and directions for future research

Like other studies, our research has its limitations. First, our work relies on cross-sectional data. Longitudinal research designs are better suited to investigating the causal effect of antecedents of outcomes, as the temporal order of the antecedents and outcome may be unclear in cross-sectional design studies. We call for more multi-source data and longitudinal designs in expatriate research. Second, all expatriates were university-level educated engineers and business professionals. The career benefits of expatriation may appear differently among people with less education. Further research among low-skilled expatriates is warranted (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2020). Third, all expatriates were Finnish and different cultures and national institutional contexts value expatriation experiences differently (Andresen et al., Citation2020), which could have affected the findings. In addition, the career situation may differ between those who continue their career internationally and those who repatriate. We should, therefore, encourage further research into those who re-expatriate (Ho et al., Citation2016). When studying the career impacts of expatriation, it would also be good to control for the length of time after expatriation, as short-term career implications may differ from longer-term ones (Baruch et al., Citation2013). Thus, the lack of such control of length can be seen as an additional limitation of our study. Finally, the sample size of the study is quite small. Thus, it is important to bear these limitations in mind when interpreting the results of our study.

In terms of specific avenues for future research, the intricate role of job fit in the relationship between career capital and CS for expatriates merits further analysis. Furthermore, while job fit is a pivotal element in shaping an expatriate’s CS, person-environment fit theory introduces additional dimensions of fit, such as person-organization fit, person-culture fit (Guan et al., Citation2021), person-career fit (De Vos et al., Citation2020), and person-skill fit (Chalutz-Ben Gal, Citation2023). Future research should explore impacts of these different types of fits not only to expatriates’ CS but also to overall sustainability of their career (De Vos et al., Citation2020).

Moreover, considering that organizations often fail to adequately plan the careers of AEs post-expatriation (Kraimer et al., Citation2009), future studies should investigate the role of career adaptability as a critical resource, particularly following significant incidents (Haenggli & Hirschi, Citation2020). This focus would add depth to our understanding of AEs, who generally exhibit less proactive career-oriented behaviour than SIEs (Andresen et al., Citation2020). In addition, our findings suggest the need for research investigating and comparing the proactive career behaviours of both AEs and SIEs post-expatriation to validate our initial observations on divergent career satisfaction. Given the potential divergence in career paths between those continuing international careers and those who repatriate, additional investigations into re-expatriation scenarios are also warranted (Ho et al., Citation2016; Mello et al., Citation2023a).

Practical implications

Our findings offer several practical implications. With regard to organizations, our study illuminates the critical role of job fit in expatriates’ CS, emphasizing the need for organizations to enhance their career management practices to find suitable positions for repatriates (Dickmann & Doherty, Citation2010) or re-expatriates (Ho et al., Citation2016). Firstly, organizations should consider developing more sophisticated career structures that offer AEs a broader array of specific choices in terms of job roles, autonomy, and flexible career pathways. Such structures could include job rotation programmes, which allow AEs to experience various functional areas within the company. A ‘career lattice’ could enable not only vertical progression but also lateral and cross-functional movements. Providing attractive choices for expatriates would be likely to enhance job satisfaction and retention (Dickmann & Doherty, Citation2010). Several MNCs are moving towards more agile global talent management with skills-based considerations at the centre of considerations (Jooss et al., Citation2024). Given that international careerists are likely to want to utilize the career capital they acquired abroad (Oleškevičiūtė et al., 2022), it would be good to devise talent management that is more sophisticated to capture both individual and organizational interests. Integrating AI-driven job matching platforms (Delecraz et al., Citation2022) can significantly enhance the alignment of AEs career capital accumulated abroad with appropriate job opportunities post-expatriation.

It is also crucial to highlight the contributions that SIEs can make to organizational knowledge and sustained competitive advantage (Shao & Ariss, Citation2020) SIE’s unique combination of tacit and explicit knowledge related to career capital can be important. Therefore, recruiters and HR managers should be attuned to the career growth and diverse international experiences of all types of expatriates, when offering positions that align with their unique qualifications and aspirations. Peltokorpi et al. (Citation2022) have shown how organizational activities in terms of preparation and reintegration can augment reverse knowledge transfer. Organizations stand to gain from identifying and recruiting individuals who demonstrate high levels of career adaptability, particularly for roles that require international mobility and resilience. In addition, employers may be able to facilitate career adaptability in terms of coaching staff to evaluate career options flexibly and to support career control. That will be more feasible within global contexts where the organizations have moved towards agile, skills-based staffing rather than where employers want to implement more rigid global talent succession systems (Jooss et al., Citation2023).

For individuals, understanding their role in shaping their career paths is crucial. They should be aware that their proactive efforts to prepare for and engage with international roles—both abroad and upon their return home—significantly affect their career. Therefore, aligning these roles with their accumulated career capital and broader professional aspirations is paramount to achieving CS. This finding is particularly relevant for SIEs, who often lack organizational support yet possess significant career capital and knowledge assets. Similarly, AEs frequently encounter inadequate organizational support (Kraimer et al., Citation2009). Proactive utilization of new digital tools, such as AI, might significantly enhance their capabilities (Huang & Rust, Citation2018). Furthermore, SIEs who leverage professional social network sites like LinkedIn (McDonald et al., Citation2023) and capitalize on the accelerated digitalization post-pandemic (Mello et al., Citation2023c) could substantially boost their CS

The above considerations extend to the need for a shift in focus from the predominantly short-term career implications of expatriation to its long-term impacts, a domain that remains largely underexplored (Mello et al., Citation2023a)

Conclusion

The present study offers a contribution to the existing body of research on expatriates’ CS, particularly focusing on job responsibility development and career satisfaction in the post-expatriation context. By employing robust quantitative methodologies and examining a diverse sample of expatriate types, this work extends the applicability of person-environment fit theory and career construction theory within the complex landscape of expatriate careers. Firstly, the study fills a gap in the literature by taking a holistic approach to CS that considers both its objective and subjective dimensions. It accentuates the role of job fit as a decisive factor in expatriates’ CS, a key insight for expatriates who accumulate significant career capital abroad. Secondly, the research deepens the discourse on career adaptability, shedding light on its implications for expatriates after repatriation or re-expatriation. It advances career construction theory by elucidating adaptability’s nuanced role, especially its significance in shaping subjective CS, after an expatriate returns home or embarks on another job abroad. Intriguingly, while the study shows that career adaptability has an indirect influence on objective CS through the moderating role of the expatriate type, it does not exert a direct effect. This finding invites a re-evaluation of current theoretical assumptions, particularly as it suggests that career adaptability influences the career trajectories of AEs and SIEs differently, which could be a consequence of the latter group’s proactive career behaviour (Spurk et al., Citation2020). Finally, by providing a theoretical framework to differentiate between AEs and SIEs, the study challenges prevailing assumptions that tend to overlook or undervalue SIEs’ CS. Our findings confirm that SIEs not only match AEs in terms of objective CS but surpass them in terms of subjective CS, particularly in career satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the financial support from the European Union’s H2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant.

Disclosure statement

We hereby declare that the disclosed information is correct and that no other situation of real, potential or apparent conflict of interest is known to us. We undertake to inform you of any change in these circumstances, including if an issue arises during the course of this submission.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Rodrigo Mello, upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akkan, E., Lee, Y. T., & Reiche, B. S. (2022). How and when do prior international experiences lead to global work? A career motivation perspective. Human Resource Management, 61(1), 117–132.

- AlMemari, M., Khalid, K., & Osman, A. (2023). How career adaptability influences job embeddedness of self-initiated expatriates? The mediating role of job crafting. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2220201. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2220201

- Andresen, M., Pattie, M. W., & Hippler, T. (2020). What does it mean to be a ‘self-initiated’ expatriate in different contexts? A conceptual analysis and suggestions for future research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(1), 174–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1674359

- Andresen, M., Bergdolt, F., & Margenfeld, J. (2012). What distinguishes self-initiated expatriates from assigned expatriates and migrants? A literature-based definition and differentiation of terms. In Self-initiated expatriation (pp. 11–41). Routledge.

- Andresen, M., Bergdolt, F., Margenfeld, J., & Dickmann, M. (2014). Addressing international mobility confusion–developing definitions and differentiations for self-initiated and assigned expatriates as well as migrants. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(16), 2295–2318. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.877058

- Andresen, M., Lazarova, M., Apospori, E., Cotton, R., Bosak, J., Dickmann, M., Kaše, R., & Smale, A. (2022). Does international work experience pay off? The relationship between international work experience, employability and career success: A 30-country, multi-industry study. Human Resource Management Journal, 32(3), 698–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12423

- Arthur, M. B., Khapova, S. N., & Wilderom, C. P. (2005). Career success in a boundaryless career world. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(2), 177–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.290

- Aycan, Z. (2005). The interplay between cultural and institutional/structural contingencies in human resource management practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(7), 1083–1119. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500143956

- Baruch, Y., Altman, Y., & Tung, R. L. (2016). Career mobility in a global era: Advances in managing expatriation and repatriation. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 841–889. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1162013

- Baruch, Y., Dickmann, M., Altman, Y., & Bournois, F. (2013). Exploring international work: Types and dimensions of global careers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(12), 2369–2393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.781435

- Begley, A., Collings, D. G., & Scullion, H. (2008). The cross-cultural adjustment experiences of self-initiated repatriates to the Republic of Ireland labour market. Employee Relations, 30(3), 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450810866532

- Benson, G. S., & Pattie, M. (2008). Is expatriation good for my career? The impact of expatriate assignments on perceived and actual career outcomes. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(9), 1636–1653.

- Booth, J. E., Shantz, A., Glomb, T. M., Duffy, M. K., & Stillwell, E. E. (2020). Bad bosses and self-verification: The moderating role of core self-evaluations with trust in workplace management. Human Resource Management, 59(2), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21982

- Bossard, A. B., & Peterson, R. B. (2005). The repatriate experience as seen by American expatriates. Journal of World Business, 40(1), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2004.10.002

- Breitenmoser, A., Bader, B., & Berg, N. (2018). Why does repatriate career success vary? An empirical investigation from both traditional and protean career perspectives. Human Resource Management, 57(5), 1049–1063. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21888

- Bretz, Jr., Robert, D., & Judge, T. A. (1994). Person–organization fit and the theory of work adjustment: Implications for satisfaction, tenure, and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44(1), 32–54. 54. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1003

- Brown, A., Bimrose, J., Barnes, S. A., & Hughes, D. (2012). The role of career adaptabilities for mid-career changers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 754–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.003

- Cable, D., & DeRue, D. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.875

- Chalutz-Ben Gal, H. (2023). Person–skill fit: Why a new form of employee fit is required. Academy of Management Perspectives, 37(2), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2022.0024

- Chan, K. Y., Uy, M. A., Ho, M. R., Sam, Y. L., Chernyshenko, O. S., & Yu, K. T. (2015). Comparing two career adaptability measures for career construction theory : Relations with boundaryless mindset and protean career attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.006

- Chan, S. H. J., & Mai, X. (2015). The relation of career adaptability to satisfaction and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 89, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.05.005

- Chen, Y. P., & Shaffer, M. A. (2017). The influences of perceived organizational support and motivation on self-initiated expatriates’ organizational and community embeddedness. Journal of World Business, 52(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2016.12.001

- Chiang, F. F. T., van Esch, E., Birtch, T., & Shaffer, M. (2018). Repatriation: What do we know and where do we go from here. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(1), 188–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1380065

- Culpan, O., & Wright, G. H. (2002). Women abroad: Getting the best results from women managers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(5), 784–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190210125921

- de Guzman, A. B., & Choi, K. O. (2013). The relations of employability skills to career adaptability among technical school students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82(3), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.01.009

- De Vos, A., Van der Heijden, B. I., & Akkermans, J. (2020). Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 103196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.011

- Delecraz, S., Eltarr, L., Becuwe, M., Bouxin, H., Boutin, N., & Oullier, O. (2022). Responsible artificial intelligence in human resources technology: An innovative inclusive and fair by design matching algorithm for job recruitment purposes. Journal of Responsible Technology, 11, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrt.2022.100041

- Dickmann, M., & Doherty, N. (2010). Exploring organizational and individual career goals, interactions, and outcomes of developmental international assignments. Thunderbird International Business Review, 52(4), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.20353

- Dickmann, M., Suutari, V., Brewster, C., Mäkelä, L., Tanskanen, J., & Tornikoski, C. (2018). The career competencies of self-initiated and assigned expatriates: Assessing the development of career capital over time. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(16), 2353–2371.

- Dowling, P. J., Festing, M., & Engle, A. D. (2013). International human resource management. (6th ed.). Cengage.

- Edwards, J. R. (1991). Person-job fit: A conceptual integration, literature review, and methodological critique. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ehrhart, K. (2006). Job characteristic beliefs and personality as antecedents of subjective person–job fit. Journal of Business and Psychology, 21(2), 193–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-006-9025-6

- Ellis, D. R., Thorn, K., & Yao, C. (2020). Repatriation of self-initiated expatriates: Expectations vs. experiences. Career Development International, 25(5), 539–562. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-09-2019-0228

- Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. (2005). Enhancing career benefits of employee proactive personality: The role of fit with jobs and organizations. Personnel Psychology, 58(4), 859–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00772.x

- Eugenia Sánchez Vidal, M., Valle, R. S., & Isabel Barba Aragón, M. (2007). Antecedents of repatriates’ job satisfaction and its influence on turnover intentions: Evidence from Spanish repatriated managers. Journal of Business Research, 60(12), 1272–1281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.05.004

- Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/256352

- Greguras, G. J., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2009). Different fits satisfy different needs: Linking person-environment fit to employee commitment and performance using self-determination theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014068

- Guan, Y., Arthur, M. B., Khapova, S. N., Hall, R. J., & Lord, R. G. (2019). Career boundarylessness and career success: A review, integration and guide to future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110(May 2018), 390–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.05.013

- Guan, Y., Deng, H., Fan, L., & Zhou, X. (2021). Theorizing person-environment fit in a changing career world: Interdisciplinary integration and future directions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126, 103557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103557

- Gunz, H. P., & Heslin, P. A. (2005). Reconceptualizing career success. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.300

- Haak-Saheem, W., Hutchings, K., & Brewster, C. (2022). Swimming ahead or treading water? Disaggregating the career trajectories of women self-initiated expatriates. British Journal of Management, 33(2), 864–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12465

- Haak-Saheem, W., Brewster, C., & Lauring, J. (2020). Low-status expatriates. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 7(4), 321–324. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-12-2019-074

- Haenggli, M., & Hirschi, A. (2020). Career adaptability and career success in the context of a broader career resources framework. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103414

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Haslberger, A., & Dickmann, M. (2016). The correspondence model of cross-cultural adjustment: Exploring exchange relationships. Journal of Global Mobility, 4(3), 276–299.

- Hirschi, A., Freund, P. A., & Herrmann, A. (2014). The career engagement scale: Development and validation of a measure of proactive career behaviors. Journal of Career Assessment, 22(4), 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072713514813

- Hirschi, A., Herrmann, A., & Keller, A. C. (2015). Career adaptivity, adaptability, and adapting: A conceptual and empirical investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.008

- Ho, N. T. T., Seet, P. S., & Jones, J. (2016). Understanding re-expatriation intentions among overseas returnees – an emerging economy perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(17), 1938–1966.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huang, M. H., & Rust, R. T. (2018). Artificial intelligence in service. Journal of Service Research, 21(2), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670517752459

- Jannesari, M., & Sullivan, S. E. (2019). Career adaptability and the success of self-initiated expatriates in China. Career Development International, 24(4), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-02-2019-0038

- Jooss, S., Collings, D. G., McMackin, J., & Dickmann, M. (2024). A skills-matching perspective on talent management: Developing strategic agility. Human Resource Management, 63(1), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22192

- Jooss, S., Collings, D., McMackin, J. F., & Dickmann, M. (2023). Towards agile talent management: The opportunities of a skills-first approach. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2023(1), 10103. (https://doi.org/10.5465/AMPROC.2023.232bp

- Kraimer, M. L., Shaffer, M. A., & Bolino, M. C. (2009). The influence of expatriate and repatriate experiences on career advancement and repatriate retention, Human Resource Management: Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management, 48(1), 27–47.

- Kraimer, M. L., Shaffer, M. A., Bolino, M. C., Charlier, S. D., & Wurtz, O. (2022). A transactional stress theory of global work demands: A challenge, hindrance, or both? Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(12), 2197–2219. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001009

- Kraimer, M. L., Shaffer, M. A., Harrison, D. A., & Ren, H. (2012). No place like home? An identity strain perspective on repatriate turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0644

- Lauring, J., & Selmer, J. (2018). Personenvironment fit and emotional control: Assigned expatriates vs. self-initiated expatriates. International Business Review, 27(5), 982–992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.02.010

- Lazarova, M., Dimitrova, M., Dickmann, M., Brewster, C., & Cerdin, J. L. (2021). Career satisfaction of expatriates in humanitarian inter-governmental organizations. Journal of World Business, 56(4), 101205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2021.101205

- Lyness, K. S., & Heilman, M. E. (2006). When fit is fundamental: Performance evaluations and promotions of upper-level female and male managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 777–785. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.777

- Mäkelä, K., & Suutari, V. (2009). Global careers: A social capital paradox. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(5), 992–1008.

- Mäkelä, L., Suutari, V., Brewster, C., Dickmann, M., & Tornikoski, C. (2015). The impact of career capital on expatriates’ perceived marketability. Thunderbird International Business Review, 58(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21742

- Maggiori, C., Rossier, J., & Savickas, M. L. (2017). Career adapt-abilities scale–short form (CAAS-SF): Construction and validation. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(2), 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072714565856

- Makkonen, P. (2015). Employer perceptions of self-initiated expatriate employability in China: A person-environment fit perspective. Journal of Global Mobility, 3(3), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-12-2014-0054

- McDonald, S., Damarin, A. K., & Membrez-Weiler, N. J. (2023). Organizational perspectives on digital labor market intermediaries. Sociology Compass, 17(4), e13061. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.13061

- Mello, R., Erro-Garcés, A., Dickmann, M., & Brewster, C. (2023c). A potential paradigm shift in global mobility? The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Business Review, 102245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2023.102245

- Mello, R., Suutari, V., & Dickmann, M. (2023a). Taking stock of expatriates’ career success after international assignments: A review and future research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 33(1), 100913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100913

- Mello, R., Suutari, V., & Dickmann, M. (2023b). Career success of expatriates: The impacts of career capital, expatriate type, career type and career stage. Career Development International, 28(4), 406–425. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-07-2022-0196

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1999). Mplus user’s guide: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers. Authors.