ABSTRACT

What happens to queer and gender-non-conforming community, bodily expression and identity when many queer spaces are closed and communities move to online spaces? In this article, we critically reflect on our collaborative project bois of isolation (boi) – a platform within Instagram for people to share selfies of the spaces and processes through which they queer gender binaries during the COVID-19 pandemic. We ask to what extent online social media spaces can disrupt normative, binarized gender identity and provide ways of reimagining the selfie. Operating within digital capitalism, selfies often serve to circulate and reproduce dominant ‘desirable’ subjectivities in ‘gender appropriate’ places. However, we argue through interventions like boi young people carve out small spaces of dissent and respite in/from social media platforms and create forms of community during lockdown. By queering the visual representations of binarized gender and questioning the neoliberal individualized ‘self’ in ‘selfies’, young people construct communal aesthetic spaces in which gender plurality and fluidity are expressed and celebrated.

Introduction

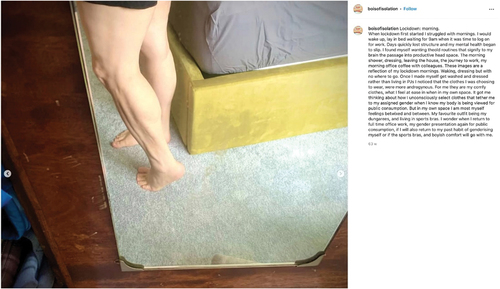

For me they are my comfy clothes, what I feel at ease in when in my own space. It got me thinking about how I unconsciously select clothes that tether me to my assigned gender when I know my body is being viewed for public consumption. But in my own space I am most myself feeling betwixed and between. Amber – boi (Instagram)

Trans embodiments – confrontations, intrusions, intimacies – Exploring and feeling safe in my body inside but feeling my body debated online and in discourses. Harry – boi (workshop 1)

In boi Instagram posts and workshops, participants like Harry and Amber, above, used selfies and accompanying text to explore gendered expression in public and private spaces during pandemic lockdown. boi emerged in 2020 as an Instagram-based collaboration between the authors – artist and academic, Dawn and academic and activist geographer – AC. Within a wider project, Making Feminist Spaces, which explored feminist practices of care and survival under pandemic lockdown, boi aimed to create a platform for sharing selfies that queer the gender binary. Using online workshops and conversations, we asked participants to explore how selfies might disrupt dominant visual representations of the gender binary. Participants used place, props, clothing and hair, bodily gestures and angles to queer not only the gender binary but also the very notion of the human ‘self’ in selfies. In contexts where, particularly, younger people are spending increasing time in ‘online spaces’, this project aimed to both increase the visual literacy of participants and viewers and disrupt dominant visual representations of gender, contributing to visual practices that celebrate gender plurality and fluidity.

This project was initiated at a time when the potential harms of social media have come under increasing scrutiny. In the second half of 2021, internal research conducted by Facebook and leaked to the Wall Street Journal spurred media headlines about the potential impact of social media on self-image and mental health. Presentation slides by researchers working for Instagram indicate that photo-sharing on Instagram increases anxiety and depression and worsens body image for one in three teenage girls (Wells et al., Citation2021). The researchers found that some of the problems teens experienced were specific to Instagram, such as those caused by social comparison, because it focuses more heavily on the body and lifestyle than other platforms (Wells et al., Citation2021). The leaked documents mirror academic research that highlights the harms of gender stereotyping in images: narrowing beauty ideals, contributing to negative body image – especially in women who seek to adhere to gender ideals (Franzoi, Citation1995) – increasing anxiety, shame, depression and eating disorders (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997; Zawisza, Citation2019) and lowering aspirations (Simon & Hoyt, Citation2012). Research on social media has argued that hostile messaging and the currency of likes and followers (Felmlee et al., Citation2019) reinforces and polices dominant feminine or masculine beauty ideals (Grogan et al., Citation2018). These practices have been linked to exacerbating eating disorders, self-harm and reduced self-esteem (Chua & Chang, Citation2016).

Despite these findings, it is important to be cautious in ascribing causality between psychological effects and media usage: The act of taking selfies is not in itself automatically harmful. While selfies are one avenue through which damaging gendered stereotypes can be reproduced, they are also a vehicle to challenge stereotypes and present bodies differently. The vilification and backlash to selfies also need to be understood as a question of power and who has access to ‘acceptable’ forms of public visibility (Murray, Citation2021; Tiidenberg, Citation2018; Walker Rettberg, Citation2014). Tiidenberg (Citation2018) argues that while it is socially acceptable for powerful men to have portraits and statues made, young people, particularly women and gay men, are vilified for appearing to seek recognition through selfie-taking (p. 81). Selfies on social media may represent a mode of resistance and an opportunity for young women and other marginalized individuals to bypass the (often white, male, privileged) ‘gatekeepers of visibility’ such as professional photographers, modelling agencies and magazine editors (Tiidenberg, Citation2018, p. 81). Murray (Citation2015) even goes as far as describing the selfie as a ‘revolutionary political movement’ and an ‘aggressive reclaiming of the female body’ (2015, p. 490).

In this paper, we draw on the selfies, comments and discussions shared on boi Instagram and in two workshops, to offer a nuanced consideration of the role of the selfie, beyond a blanket vilification or celebration. Specifically, we build upon an emergent body of research that examines how selfies can be used to disrupt the gender binary. We take a critical look at our work with boi to understand how sharing selfies might offer creative tools to queer bodily expression, increase visual literacy and foster queer community. Participants’ contributions and our own experiences of experimenting with selfies defied facile, binarized characterizations of selfies, social media and the spaces of pandemic lockdown. Through boi, we found distinct visual-spatial techniques that either work, or crucially – refuse to work – to queer and disrupt the ‘business as usual’ circulation and hierarchies of what count as valued selves and selfies.

I: selfie practices and gender

As an interdisciplinary project for ‘queering selfies’, our work on boi has been shaped by broader literature on selfie practices. Here, we review some of this existing work on selfies as a highly gendered practice before considering how selfie practices have been understood as queering gender and/or creating queer community.

Selfie as practice

Research in the humanities and social sciences discusses selfies as a range of spatial and digital practices, including performance and staging of context and self, editing, filtering, sharing and interaction with images (Liu, Citation2021, p. 240). Tiidenberg (Citation2018, p. 134) sees these practices as tied to human desires for what she calls belonging and becoming, highlighting five types of selfie practices tied to: (1) performing identity, (2) thinking through something, (3) interaction with others, (4) expression and (5) monetary gain (e.g. work, buying/selling or branding). With boi being a response to the spatial restrictions of pandemic lockdown, we are particularly interested in a sixth, and related, aspect of selfies: the self in relation to objects and spaces. This is a perspective emphasized by digital geographers, who have considered relationships between spaces, subjectivities and digital technologies (Rose, Citation2016).

Rather than seeing online spaces as entirely separate from – or opposed to – physical spaces, these are understood as mutually constitutive (Kitchin & Dodge, Citation2011). This virtual-physical hybridity (Miles, Citation2018) is manifest in selfies through their emplacement and the curation of locations of the self, as well as the use of geolocational data and digital platforms which facilitate social and physical connection. For example, Bonner-Thompson (Citation2017) highlights the decision of where to locate Grindr selfies is an important part of the type of masculinity that is being portrayed. Blanchfield and Lotfi-Jam (Citation2017) highlight how the archetypal selfie angle – a photo taken from above, pointing downwards, allows for the subject’s context to become an important and integral part of the selfie.

Despite understanding selfies as interacting with physical spaces and processes, it is important to recognize the specificities and affordances of online spaces. For example, the creation of shared, often anonymous, online spaces allows for ‘otherwise geographically dispersed sex and gender minorities’ (Hakim, Citation2019, p. 143) to find one another. According to Hakim (Citation2019), this has provided the conditions to establish identities and cultures (e.g. trans*, intersex and asexual) outside of both the heteronormative and homonormative mainstreams. It also allows for self-expression without the fear of imminent physical violence. Non-binary artist and writer Alok Vaid-Menon describes the Instagram-based self-portraiture as a ‘sort of idyllic space too – an imagination of what I could look like/become without fear of harassment’ (Lehner, Citation2019).

The gendered selfie

As Vaid-Menon also recognizes, this ‘idyllic space’ sits within social media dominated by powerful norms relating to gender, race, sexuality and class. This extends to acceptable selfie locations. Research on selfie practices has highlighted the gendered and racialized disciplining of what are considered ‘acceptable locations’ for selfies. While group selfies or tourist destinations are seen as more acceptable (Tiidenberg, Citation2018, p. 51), research by Williams and Marquez (Citation2015) on millennial selfie practices in Texas and New York indicates that bathroom selfies are more divisive. They found that bathroom selfies taken by white men are stigmatized as narcissistic, unacceptable masculine behaviour by white women (e.g. through adding negative comments on posts) (2015, p. 1784). Williams and Marquez (Citation2015) found that Black and Latino men were not stigmatized in the same way for taking selfies, as long as images were limited in number and reinforced racialized ideals of masculinity.

Binary gender ideals and relations of power can also be reproduced by selfies through the composition of the images and the subject’s body comportment. Researchers have taken prior work on gender and visual representations and extended it to selfies. For example, Prieler and Kohlbacher (Citation2017) build on research by Archer et al. (Citation1983), finding that face-ism (depicting the face more prominently) is more common in images of men and body-ism (emphasizing the body) more frequently features in images of women. In relation to selfies, Prieler and Kohlbacher (Citation2017) found that selfies taken by older men and women (potentially holding more traditional views on gender roles) were more likely to show gender-based face-ism/body-ism.

Similarly, Döring et al. (Citation2016) analysed 500 Instagram selfies to explore if they conformed to gender stereotypes as identified in Erving Goffman’s (Citation1976) Gender Advertisements. Goffman identified five categories through which women were objectivized and subordinated to men in visual adverts: relative size, light feminine touch, function ranking (e.g. women in a subordinate occupation), ritualization of subordination (e.g. physically being lowered or off-balance) and licenced withdrawal. To these five categories, Döring et al. (Citation2016) added Kang’s (Citation1997) category of bodily display (how revealing clothing is) and three categories deriving from selfies: muscle display; kissing or pouting face and faceless portrayal. The study revealed that gender stereotypical behaviours found in adverts are repeated in selfies and that feminine touch, imbalance, withdrawing the gaze and loss of control are featured in selfies more frequently than in magazine adverts. In the selfie categories, female selfies contained more pouts and faceless portrayals (body-ism), while male selfies displayed more muscle presentation (Döring et al., Citation2016).

Queering selfies

Research into queer digital practices has emphasized their liberatory potential, transforming LGBTQI+ spaces, politics and communities (Hakim, Citation2019; Miles, Citation2018). Research on queer selfies has highlighted their role in enhancing queer visibility (Duguay, Citation2016; Lehner, Citation2019), raising awareness of queer oppression, challenging stereotypes (Duguay, Citation2016) and affirming ‘intersectional and hybrid trans and non-binary representations’ (Lehner, Citation2019, pp. 52–53). In research with trans and gender-fluid Tumblr users, Vivienne (Citation2017) found that positive comments on selfies helped promote body acceptance and that users viewed trans and gender-fluid selfies as defying industries that promote binary beauty ideals and capitalize on consumer’s insecurities.

Queering selfies imply a range of practices that question the fixity and binarized nature of gender. Vivienne (Citation2017) found that Tumblr users tended to post selfies in pairs or series to produce narratives of gender-as-fluid. Similarly, Darwin (Citation2017) analysed the contents of genderqueer subreddit discussion threads and selfies to determine how non-binary people ‘do gender’ online. Darwin found that existing binary gender tropes associated with hair, clothing and stance, such as those identified by Goffman (Citation1976) are combined and played with in order to perform a non-binary gender. For prominent Instagram influencers, practices of queering gender binaries infuse their entire account: Lehner notes that Instagram allows Vaid-Menon’s account to function like an evolving, transforming self-portrait, with an ‘ongoing proliferation of complex self-representations’ that can destabilize and de-essentialize gender (2019, p. 59). For Vaid-Menon, self-portraiture is a vehicle for deconstructing the racist and colonial construction of the gender binary. Similarly, Germain de Larch, a queer artist and activist in South Africa, uses self-portraits and portraits of non-binary people, not to showcase individualized, private queer existences, but as ‘multivocal’ and ‘nuanced’ representations that affirm queer lived experience (de Larch, Citation2014, p. 122).

The liberatory potential of selfie-sharing practices needs to be tempered by a recognition that social media is ultimately an arena for the exploitation of data and discourses – produced and circulated to aid the accumulation of capital (Hakim, Citation2019). If queer and non-binary people must conform to neoliberal expectations of data-producing self-disclosure to gain exposure, this puts into question the extent and nature of ‘liberation’ in queer online spaces. Yet, queering selfie practices may contribute to more incremental changes in visual practices and cultures online. Experimental research provides some evidence that repeated exposure to ‘counter-stereotypical’ associations in images can reduce racist (Olson & Fazio, Citation2006) and sexist prejudices in viewers (Suitner et al., Citation2016). Suitner et al. (Citation2016) built on research by Chatterjee (Citation2002) on spatial biases in portraits, highlighting that in cultures where writing flows from left to right, subjects are assumed to have greater agency and social power if they face or gesture rightwards. Suitner et al. (Citation2016) repeatedly exposed participants to images in which male portraits faced left and female portraits faced right, countering the dominant visual paradigm. This study indicates that there may be some potential for greater exposure to gender nonconforming selfies to diminish discrimination towards diverse expressions of gender.

Our project seeks to explore this potential and respond to the call from Prieler and Kohlbacher (Citation2017), for educators, activists and policymakers to do more to raise awareness of visual imbalances of power and their consequences, allowing the public to critically analyse visual practices in advertising and photojournalism. With Boi, we aim to increase visual literacy of participants and viewers and intervene in dominant circulations of selfies, contributing to a more heterogeneous visual culture.

boi methodologies

boi emerged in 2020 as a response to the Instagram-based project Girls of Isolation, which presented monochrome selfies of predominantly femme, young and slim people, alone during lockdown. We were concerned these largely reiterated dominant gender stereotypes with an artistic filter. We wanted to create and participate in aesthetic spaces that queer the gender binary, yet boi did not look to create an online space only for those labelled as non-binary and we welcomed anyone who experienced marginalization for their gender. In a collaborative creative research process on Instagram and in online workshops, we focused on the process of queering and the immanence of gender (March, Citation2020), disrupting gender fixities and binaries (Barker & Iantaffi, Citation2019; Oswin, Citation2008).

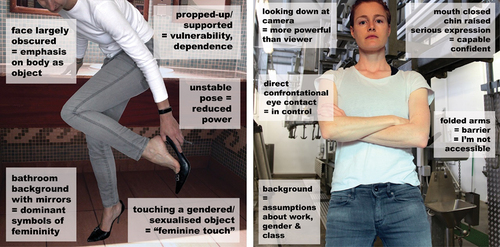

After seeking institutional ethical clearance for the project, we populated our Instagram page with a series of our own ‘spoof’ self-portraits, created in our respective homes during lockdown, using tripods, digital SLRs and Photoshop for fake backgrounds (). These annotated images aimed to enhance visual literacy and were informed by the content-analytical schemes discussed earlier (Archer et al., Citation1983; Chatterjee, Citation2002; Döring et al., Citation2016; Goffman, Citation1976; Kang, Citation1997). We dressed in plain white and grey to minimize attention to specific (gendered) clothing worn and to focus on how our bodies took up space and interacted with objects. In many ways, these spoof images mimic and parody the very binary gender performances that we hoped to disrupt in our project.

Figure 1. ‘Spoof instructional selfies’ by AC Davidson and Dawn Woolley. bois of isolation Instagram project, UK (2020). Credit: the authors. CC BY-NC-ND.

Putting ourselves into the images was an important – if at times uncomfortable – aspect of boi. We took a feminist participative approach (Askins, Citation2018) in which we recognize our own embodiments and positionalities as both participants and researchers/artists. Embodied approaches have a long tradition in both feminist (cultural) geography and self-portraiture, in questioning the god-trick ‘view from nowhere’ (Haraway, Citation1988), decentring the heteropatriarchal gaze and refusing appropriation (Luciano & Chen, Citation2015). In embodied practices including self-portraiture or autoethnography, the ‘proper’ scale of power and politics is questioned, making the personal political and diminishing the ‘distance between subject and object’ (Jones, Citation1998, p. 182). By setting ourselves the same challenges that we set other contributors and reflecting on our own experiences, we brought this autoethnographical material into conversation with responses from contributors.

We linked potential participants to a Qualtrics site which allowed for informed consent, uploading of selfies and reflection on the process. To allow for a range of gender expressions, we asked for up to four selfies that queer the gender binary. We wanted to defy the idea of a single, coherent identity (required by social media platforms to track users and gather data more effectively) and avoid pairs of images that might infer a gender binary or the ‘before’ and ‘after’ transformation common in advertisements. Using hashtags (e.g. #nonbinary and #queer) and reciprocal following of users in our own social networks and beyond, we put a call out for submissions. Contributors were asked to consider why they chose gestures, objects and locations for their selfies and to reflect on their feelings during the process. After receiving minimal responses via the (long and potentially off-putting) Qualtrics form, we organized two online workshops. We had intended to initiate collaborative discussion and analysis of images on Instagram. However, the practices of ‘liking’ and re-sharing did not lend themselves as well to this. Instead, the workshops allowed us to create a collaborative, discursive and experimental online space during the pandemic. The first workshop, on 16 February 2021, was attended mainly by students who responded to a call from a university’s LGBTQI research group (W1). The second workshop, on 8 April 2021, was held as part of a conference attended by academics and PhD students in the arts (W2).

Workshop participants were encouraged to experiment with selfie-taking practices and reflect on this experience in group discussions. Those who wished could share their selfies in an online document and were asked whether they consented to us reproducing these images afterwards. Participants created such a broad range of interesting and creative selfies that we were able to select images for this paper that largely do not contain faces. We opted for this, despite having obtained consent through the workshop and in subsequent emails, to preserve privacy. However, the participants gave their consent to be named (and shared on Instagram and in this paper), so we treat these as creative self-portraits that should be attributed.

Doing selfies and gender otherwise in pandemic lockdown

When participating in boi, we asked selfie-takers to reflect on three main themes: place; props, clothing and hair (styling) and bodily gestures and angles. In the following sections, we follow this thematic structure to outline some of the key ideas expressed in the selfies.

Place

The context of pandemic lockdowns in 2021, and our virtual workshops, meant that most selfies on boi were taken indoors. We asked participants to consider how their selfie location expressed their identities, gender and experience of pandemic lockdown. As discussed earlier, the location of selfies is not simply a backdrop, but an inherent part of constructing selfies and the ‘self’. Socially acceptable locations of selfies are also racialized and gendered. As authors, gendered as female/non-binary, we reflected on how we felt much more comfortable taking selfies when we were alone, often at home. Here, we focus on the places highlighted in participants’ selfies. Many of our participants in workshop one lived in shared or student housing, and in workshop two, participants included professional academics and/or artists, and studios, offices and homes were more prevalent backdrops. Interestingly, the impact of social class or different housing arrangements (e.g. intergenerational living) did not arise in workshop discussions or participant responses.

Research on gender, sexuality and domestic spaces highlights how home spaces and the binary of domestic/public spaces are structured by heteronormativity (Pilkey et al., Citation2015) and dominant conceptions of binary gendered roles. The ambivalence of home for LGBTQ+ youth needs to be recognized: while home spaces can offer a shielding from violence and hegemonic norms of gender and sexuality, unsupportive or unsafe home settings can require leaving or going out to come out (Matthews et al., Citation2018). Lockdowns also intensified existing ambivalences around specific spaces, as Victor writes: ‘As a lifetime night owl and insomniac, the bed can be an uncomfortable location – more so now when there’s nowhere else to go. Bedroom selfies are supposed to be intimate, but lockdown can make them lonely’ (W1). For young people living in shared housing or student halls, the bed and bedroom risks becoming a space of confinement. As Victor discusses in a caption to , activities such as cycling become an expression of freedom in this context: ‘as a trans man, masculinity and freedom are associated, which I recognize as potentially problematic’.

Figure 2. ‘Selfie’ by Victor Max-Smith. UK (2021). Credit: the author. Reproduced with permission from the author.

Some of our participants mentioned being shielded from ‘public consumption’ during lockdown, making them feel more able to examine and experiment with queer and/or non-binary presentation. Amber said that the comfort of her own space enabled her to wear clothes that make her feel less tethered to her assigned gender (Instagram). However, via social media and mobile technologies, selfie-sharing brings the public into the private realm and connects the private into a wider community. This can provide what Ehlin describes as a ‘type of communal self-love that affirms non-isolation’ (Ehlin, Citation2014, p. 80). As Phoenix commented: ‘bed, feels very intimate to me and recently photos from bed have become more meaningful in terms of connection from a place of comfort and also of vulnerability’ (W1). Selfie-sharing may feel exposing, and there is a vulnerability to not receiving the desired acknowledgement and affirmation that is so important in the production of ourselves as subjects (see Ehlin (Citation2014), drawing on Judith Butler).

Participants such as Guy and Victor took selfies in mundane ‘transient spaces’ like stairs (Guy, W1) or hallways (Victor, W1), spaces which blur private–public boundaries, particularly in shared housing. Just like the selfie linking the private and public, stairs often connect more public-facing spaces in the home to more private places. Choosing mundane selfie locations counters the medium’s propensity to show spectacular, Instagram-able moments in notable locations.

Props, clothing and hair (styling)

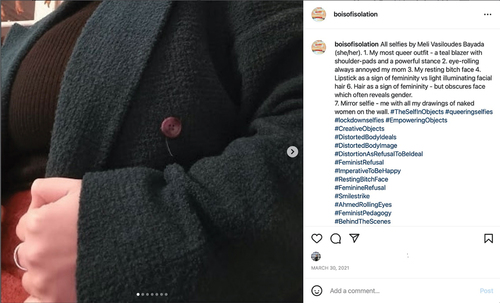

We invited participants to think about how clothing, accessories, hairstyles and objects in selfies can be expressions of gender identity and can reinforce, subvert or queer gender binaries. For example, Meli writes: ‘My most queer outfit – a teal blazer with shoulder-pads and a powerful stance’ (). In another selfie, applying red lipstick with light illuminating her facial hair, she comments on the mixing of gender stereotypes (W1).

Figure 3. ‘Selfie’ by Meli Vasiloudes Bayada (Instagram post). UK (2021). Credit: the author. Reproduced with permission from the author.

Pandemic lockdown limited or changed the way participants related to objects, clothing and hair and shifted online the queer nightlifes and events, for which we might have ‘dressed up’ – such as club nights or drag king workshops. In , Harry shows off their feet and ankles in a pair of glittery high-heeled shoes accompanied by the caption ‘missing the dance-floor’ (W1). Instead, depicting themselves next to a desk covered in makeup and jewellery, Harry was ‘getting ready for zoom meetings’ (W1). Similarly, Sophie took a selfie in a mirror on her makeup desk and wrote:

a location for studying ‘ideal’/normative femininity - espec in context of going outside for a walk feeling like an event and a chance to be looked at + context of pivotal queer experiences during lockdown - what makes me feel like an ‘acceptable woman’? What are my expectations of ‘ideal femininity’ and how do I give in to them and/or subvert them? I can study that in the mirror. (W1)

Some objects in selfies played with sexualization. In Gender and Advertising, Goffman found that women were more likely to be photographed touching an object because ‘feminine touch’ implies that the female body is touchable (1976). In one of Victor’s selfies, he looks up towards the viewer with the end of a drum stick resting on his lip. He writes:

As I’m on the asexual spectrum, it seems weird to me how and why people choose objects to do sexualised displays with - the significance of chosen objects can just be that they’ve got a phallic shape. In this photo, that I use my drums for activism could be obscured by me using a drumstick as a sexy prop. (W1)

Hair featured prominently in several selfies and was a key point in workshop discussions. Not having access to professional haircuts on lockdown was a source of anxiety for some and an opportunity for DIY or housemate experimentation for others. Body and facial hair are often strongly tied to ideal expressions of masculinity or femininity and our navigation and desires around these. As Victor says, context matters, ‘facial hair and the lack of it is gendered differently in different contexts […] being able to shave, like my dad, was a big masculine milestone for me’ (W1). Meli, in an image of hair obscuring her face, and in the image applying lipstick, plays with how hair in different places is gendered differently (W1). Phoenix shared a bathroom selfie in which they played with more ‘masculine looks’ by showing their armpit hair (W1). Sophie’s selfie of a short pandemic haircut coincided with a new (first) queer relationship (W1). Conversely, hair that grew uncomfortably long during the pandemic needed to be cut and queered into a ‘man bun’ by AC (Instagram).

Gestures, body and angles

Our spoof instructional images () illustrate how pose, position and gesture are often used to emphasize a person’s relative power. We asked participants to reflect on how they are holding and angling their cameras and bodies to express – and play with – ideas of gender and power. Selfies taken using a reverse camera lens (‘selfie-mode’) and angled down towards the face, place the subject lower than the viewer, implying inferiority, whereas taking selfies through a mirror often presents the subject on an equal or slightly raised level in relation to the viewer.

Subverting the dominant practice of taking a selfie from above, Sophie took a photo of her unsmiling face, looking down into the camera (W1). In , the camera is positioned on the floor pointing up at Victor, who is sitting in front of a bike, looking away from the lens; framing tropes that are frequently employed in male portraiture to show the subject is strong, powerful and refuses to be objectified by the viewer’s gaze (Goffman, Citation1976).

Mirrors can function as a distancing and framing mechanism that fragments the body, isolating particular body parts. Images that do not include the face can be read as reducing the subject to the body. This can also fetishistically sexualize characteristics such as masculine muscles or feminine lips in binarized ways. In contrast, the images shared on boi, such as Amber’s pose in emphasizing her leg muscles, tend to present body parts in ambiguous ways that are difficult to ‘read’ in gender binary terms (Instagram).

In images that do feature the face, the gender politics of facial expressions came up repeatedly. Helen used the hashtag #GiveUsASmileLove with a series of unsmiling selfies, commenting: ‘The power of not smiling – even I, with my tattoos and queer undercut, will post it rarely. Afraid of further isolation and being singled out, we bare our chimp grin and hope for the best’ (Instagram). Similarly, Sophie describes this as: ‘Allowing my face to just be – relaxed actual expression, having to confront an unposed existence when existing in my own space by myself for lockdown’ (W1). Meli also included expressions that challenge the expectation that (particularly feminine) people should look cheerful and inviting. Her series of selfies show; ‘resting bitch-face’, eye-rolling, applying lipstick and then distorting her lips (W1). In contrast, Guy used exaggerated gestures and facial expressions to show playfulness (W1).

These facial expressions could be read as a resistance and disruption of gendered expectations and a refusal to carry out the affective labour of performing the sex-gender we were assigned at birth. Yet, perhaps due to the limited social scripts we have available to read and perform gender and power, this often appears as a ‘flipping the script’: refusing to ‘do’ your assigned gender often meant assuming the expressions and bodily comportment of the opposite gender. In a similar way, at the end of the workshops, we invited participants to take a group selfie that challenged expected selfie forms. The most popular suggestion was to take ‘uglies’ - a type of selfie that is intentionally unattractive or unedited and shows blemishes (Darr et al., Citation2022). Some selfie-takers view them as opposing expectations of beauty. However, scrolling through some of the 45,000 Instagram posts tagged with #uglyselfie, very few selfies deviate from attractiveness standards. This points to the difficulty in thinking selfies beyond the norms of social expectation and the register of attractive/unattractive.

Queering the coherence and concept of the ‘self’ in selfies

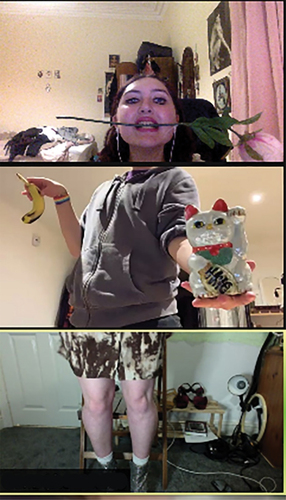

Producing a series of selfies allowed participants to play with a range of selfie practices (Liu, Citation2021) showcasing different aspects of their gender identities, relationships to themselves, friends and communities during pandemic lockdown. As Barker and Iantaffi (Citation2019) suggest, we are complex ‘multiversal’ beings. For example, Harry’s series () explores varying gender presentations: One selfie (not depicted here) shows mainly their torso and face wearing bright red lipstick, with the tops of their bare legs showing a wide stance. Their pose fills the frame, and they gaze directly into the camera, but they are looking up at the camera with their head tilted. This combination of visual codes obfuscates a clear reading of gender and power. In the following image, also not reproduced here, they stand with one leg slightly ahead and raised, their back to the viewer looking over their shoulder, gently holding their arm with their hand, reproducing some of Goffman’s ‘feminine poses’. Presenting these selfies in sequence, Harry portrays a fluid gender identity that queers the gender binary as well as the association of power or status with particular bodily comportments and genders.

Selfies also confounded a coherent and unified ‘self’ through a refusal of the dominant locus of vision: questioning the focus on the eyes and face, and instead, using selfies not so much to be seen but also to find other ways of considering the self. For example, in Mariana focused the viewers’ gaze away from the eyes and face, instead framing her ear with a square tube-like object that directs and constrains the viewer’s gaze. Mariana writes, ‘I tried to find another gaze, or frame to look myself through. It felt almost impossible to see my own face and not fall into stereotypical gender gestures and body parts. So I look for other set of “eyes”’ (W2). In another image, she holds a framed photograph of a fruit in front of her face and writes:

…, I was trying to connect to an object which I feel has an ambiguous origin, feels like cells coming into formation, still undone. And this might have been my origin too. Queering my origin might be about imagining I once was a fruit, a vegetable, a bundle of green cells. (W2)

Figure 6. ‘Selfies’ by Mariana Cabello. UK (2021). Credit: the author. Reproduced with permission from the author.

Mariana alongside AC in becoming-carpet () use their selfies to refuse the imperative to be recognized as human. This aligns with queer and trans critiques and refusals of humanism: If the measure of ‘proper’ humanity is transphobic, ableist, racist and heteronormative, these interventions attempt not to centre, uphold – or be recognized within – this vision. Mariana’s selfies, AC’s carpet selfie and a workshop selfie in which participants’ faces are obscured by yellow cards with the text ‘IDENTITY AS A FICTION? ALWAYS WE NEED FICTIONS’ question human identity in a way reminiscent of the professional self-portrait taken by queer Chicana artist Laura Aguilar. Portraying herself as a boulder: ‘she is entering the very nonhuman fold where some would place her, effectively displacing the centrality of the human itself’ (Luciano & Chen, Citation2015, p. 184).

Figure 7. ‘Exquisite corpse selfie’ by Sophie Nardi-Bart, Victor Max-Smith and Harry. UK (2021). Credit: the authors. Reproduced with permission from the authors.

Figure 8. ‘Glitch Selfies’ by Dawn Woolley and AC Davidson. bois of isolation Instagram project, UK (2020). Credit: the authors. CC BY-NC-ND.

Aguilar’s body-as-boulder and AC’s and Mariana’s selfies work in different ways to deny the body’s identification within hierarchies of power. By embracing and exploring the category of sub-human or not-properly-human (often ascribed to queer, fat, trans, Black and/or disabled bodies), these images ‘queer the human’ and subvert ‘capture’ or reproduction of aesthetic bodily ideals that produce value for neoliberal capitalism. In a similar vein, Hakim argues that the non-hierarchical decentralization of digital technologies could bring about a ‘post-neoliberal future in which all bodies, no longer marked by differences in power, have equal capacity to limitlessly multiply their force of existence in all areas of social life’ (2019, p. 146). We do not necessarily view online selfie-taking practice as representing the liberatory potential that Hakim does and query to what extent bodies can – and should – be devoid of markers of power (what of the relief or pleasures of consensually relinquishing power, questioning and playing with unequal relations of power, as shown in some of the boi selfies, discussed above?). We are intrigued, however, by Hakim’s notion that digital media might allow bodies, in ‘mutually empowering assemblages’ to ‘become-imperceptible to digital capitalism’s apparatuses of capture’ (2019, p. 146). In one workshop, we played with representations of non-individualized, recombinant selves: asking participants to create collaborative selfies using props and the capabilities of Zoom. As seen in , they created exquisite, gender-incoherent cyborg mashups.

These playful images foreground collectivity rather than individual identity, resisting digital capitalism’s demand for a coherent ‘self’. While there may be moments of imperceptibility or freedom-from-capture afforded by digital media, we found the glitch, discussed here, a more nuanced metaphor for the ambivalent potential of selfies. Our accidental creation of glitch selfies () queered the cohesion and legibility of/as ‘proper’ human subjects. These glitches – digital and machinic failures (Richardson, Citation2021) – produced damaged images in accidental alliance with our phones and Instagram. The glitch queers temporal and spatial boundaries with backgrounds, bodies, past images and objects coalescing. According to Russell (Citation2020), the glitch denotes the failure of queerness to perform fixed gender and a refusal to seek recognition and identify within this schema. As unexpected errors, which are difficult to reproduce, predict or avoid, the glitch represents a generative failure to control technology and representation (Russell, Citation2020). In contrast to Russell’s vision of empowerment ‘to choose and define ourselves for ourselves’ (p. 11), we argue that the glitch offers a more radically indeterminate empowerment, with less onus on individualized imperatives to choose.

Through a failure in form, the glitch obscures the ‘self’, impeding the intended outcome of a self-portrait, and instead brings into view the constituent colours and pixels, reminding the viewer of the digital processes of image production. The glitch images offer a metaphorical crack through which to see the co-constitution of the human and technological (Cockayne & Richardson, Citation2018, p. 1588) and the conditions of social media image (re)production. Breaking ourselves down into pixelated, abstracted forms, our glitch images speak to our role on social media platforms, not as human individuals, but as cohesions of data points, as data workers, (re)producing images, meanings and values within circuits of capital accumulation (Richardson, Citation2021).

Conclusion

boi failed exquisitely as an Instagram project. We did not attract a large following or many responses, and we shifted to the more transient encounter of the online workshop. Yet in true queer form, these failings allowed for more unexpected and collaborative ways of interrogating the selfie and gendered selves during lockdown. In our workshops and calls for participants on Instagram, we provided spoof selfies and a skeleton structure asking for participants to consider how they used location, props/objects and body comportment to express or queer gender in lockdown. The resulting images speak to both a resistance to – and an inevitable complicity with – gendered and heteronormative representations and structures of power. The gender binary is often reflected and reproduced within attempts at ‘transcending’ it. Our words, images and workshop discussions also reflected on the ‘betwixt and betweenness’, in Amber’s words, of the spatio-temporalities of lockdown: pandemic spaces are becoming intimate-public, virtual-real and liberating-constraining.

Although, at the time of writing, the context of the pandemic has shifted towards a ‘living with’, the structuring force of the gender binary represented in online/offline worlds remains. The range of online platforms and – their popularity – continue to proliferate, and as such there are ever-growing opportunities to play, queer, subvert and comply with gender binaries in visual self-representation. To enable selfie-takers to contribute to a more heterogeneous visual culture, academics and technologists could examine and expose the algorithms that prefer selfies conforming to dominant beauty and gender standards. The use of hashtags to facilitate queer community building and queer notions of the self(ie) might also be examined to increase visual literacy around the power of gender binaries. Furthermore, there are unanswered questions: can selfies exist without contributing to neoliberal discourses of individualism and productivity? Can people outside of dominant (gendered) beauty ideals self-represent in ways that resist capture as commodified data points?

The boi project to queer gender binaries through selfies sits in this space between the liberational potential of a post-neoliberal future in which diverse bodies represent themselves (Hakim, Citation2019) and inevitable complicity within circuits of bodily normativity and digital capital. Our selfies-in-series, collaborative online renditions of the ‘exquisite corpse’ game and unintended glitches (Leszczynski, Citation2019; Russell, Citation2020) perhaps offer us generativity in this impasse. These offer ways to refuse binarized choices – or indeed any imperative for individualized ‘choice’. Instead, the error, the unpredictable, the mash-up, the illegible and non-reproducible (e.g. a finite workshop event) speak to ways of evading and refusing capture within the binary.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants in our workshops and on Instagram for their creativity, engagement and generosity. For the purposes of open access, the authors have applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Accepted Author Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dawn Woolley

Dawn Woolley is an artist, a research fellow at Leeds Arts University and an Honorary Research Fellow, in the Faculty Research Centre Business in Society at Coventry University. Woolley’s research examines contemporary consumerism and the commodified construction of gendered bodies, paying particular attention to the new mechanisms of interaction afforded by social networking sites. Recent solo exhibitions include “Consumed: Stilled Lives” bildkultur Gallery, Stuttgart (2022), “Consumed: Stilled Lives” Perth Centre for Photography, Australia (2021) and “Dance for Good & Exercise Your Rights” Public Space One Gallery, Iowa City (Hard Stop 2020). Consuming the Body: Capitalism, Social Media and Commodification was published in 2023 by Bloomsbury.

A.C. Davidson

AC Davidson teaches, learns and researches around questions at the intersections of sustainability, queer and feminist theory, embodiment and social justice. Recent publications include Cycling Lungs in Antipode (2021) and Radical Mobilities in Progress in Human Geography (2020). Current projects include research on gender, embodied energies and the mobile work of truck driving; enhancing access and equity into geography and the geosciences (NERC-funded) and interdisciplinary and grassroots concepts of Geoethics (British Academy funded). They are Senior Lecturers in Human Geography at the University of Huddersfield.

References

- Archer, D., Iritani, B., Kimes, D. D., & Barrios, M. (1983). Face-ism: Five studies of sex differences in facial prominence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(4), 725–735. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.4.725

- Askins, K. (2018). Feminist geographies and participatory action research: Co-producing narratives with people and place. Gender, Place & Culture, 25(9), 1277–1294. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2018.1503159

- Barker, M. J., & Iantaffi, A. (2019). Life isn’t binary: On being both, beyond, and in-between. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Blanchfield, C., & Lotfi-Jam, F. (2017). The Bedroom of things. Log, 41, 129–134. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26323727

- Bonner-Thompson, C. (2017). ‘The meat market’: Production and regulation of masculinities on the grindr grid in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(11), 1611–1625. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2017.1356270

- Chatterjee, A. (2002). Portrait profiles and the notion of agency. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 20(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.2190/3WLF-AGTV-0AW7-R2CN

- Chua, T. H. H., & Chang, L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.011

- Cockayne, D. G., & Richardson, L. (2018). A queer theory of software studies: Software theories, queer studies. Gender, Place and Culture, 24(11), 1587–1594. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2017.1383365

- Darr, C. R., Doss, E. F., Humphreys, L., & Humphreys, L. (2022). The fake one is the real one: Finstas, authenticity, and context collapse in teen friend groups. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 27(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac009

- Darwin, H. (2017). Doing gender beyond the binary: A virtual ethnography. Symbolic Interaction, 40(3), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.316

- de Larch, G. (2014). The visible queer: Portraiture and the reconstruction of gender identity. Agenda, 28(4), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2014.968408

- Döring, N., Reif, A., & Poeschl, S. (2016). How gender-stereotypical are selfies? A content analysis and comparison with magazine adverts. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 955–962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.001

- Duguay, S. (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer visibility through selfies: Comparing platform mediators Across Ruby Rose’s Instagram and vine presence. Social Media + Society, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116641975

- Ehlin, L. (2014). The subversive selfie: Redefining the mediated subject. Clothing Cultures, 2(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1386/cc.2.1.73_1

- Felmlee, D., Inara Rodis, P., & Zhang, A. (2019). Sexist slurs: Reinforcing feminine stereotypes online. Sex Roles, 83(1–2), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01095-z

- Franzoi, S. L. (1995). The body-as-object versus the body-as-process: Gender differences and gender considerations. Sex Roles, 33(5–6), 417–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01954577

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

- Goffman, E. (1976). Gender advertisements. Harper Torchbooks. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-16079-2

- Grogan, S., Rothery, L., Cole, J., & Hall, M. (2018). Posting selfies and body image in young adult women: The selfie paradox. Journal of Social Media in Society, 7(1), 15–36. https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/618951

- Hakim, J. (2019). Work that body: Male bodies in digital culture. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism as a site of discourse on the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

- Jones, A. (1998). Body art performing the subject. University of Minnesota Press.

- Kang, M.-E. (1997). The portrayal of women’s images in magazine advertisements: Goffman’s gender analysis revisited. Sex Roles, 37(11–12), 979–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02936350

- Kitchin, R., & Dodge, M. (2011). Code/Space [electronic resource] : Software and everyday life. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262042482.001.0001

- Lehner, A. (2019). Trans self-imaging praxis, decolonizing photography, and the work of alok vaid-menon. Refract: An Open Access Visual Studies Journal, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.5070/r72145857

- Leszczynski, A. (2019). Glitchy vignettes of platform urbanism. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 38(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819878721

- Liu, C. (2021). Exploring selfie practices and their geographies in the digital society. The Geographical Journal, 187(3), 240–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12394

- Luciano, D., & Chen, M. Y. (2015). Has the queer ever been human? GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian & Gay Studies, 21(2–3), 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2843215

- March, L. (2020). Queer and trans* geographies of liminality: A literature review. Progress in Human Geography, 45(3), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520913111

- Matthews, P., Poyner, C., & Kjellgren, R. (2018). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer experiences of homelessness and identity: Insecurity and home(o)normativity. International Journal of Housing Policy, 19(2), 232–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2018.1519341

- Miles, S. (2018). Still getting it on online: Thirty years of queer male spaces brokered through digital technologies. Geography Compass, 12(11), e12407. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12407

- Murray, D. C. (2015). Notes to self: The visual culture of selfies in the age of social media. Consumption Markets & Culture, 18(6), 490–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2015.1052967

- Murray, D. C. (2021). On photographic photography’s multitudes in the age of online self-imaging. In J. Lewis & K. Parry (Eds.), Ubiquity (pp. 179–196). Leuven University Press.

- Olson, M. A., & Fazio, R. H. (2006). Reducing automatically activated racial prejudice through implicit evaluative conditioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(4), 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205284004

- Oswin, N. (2008). Critical geographies and the uses of sexuality: Deconstructing queer space. Progress in Human Geography, 32(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507085213

- Pilkey, B., Scicluna, R. M., & Gorman-Murray, A. (2015). Alternative domesticities. Home Cultures, 12(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/17406315.2015.1046294

- Prieler, M., & Kohlbacher, F. (2017). Face-ism from an international perspective: gendered self-presentation in online dating sites across seven countries. Sex Roles, 77(9–10), 604–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0745-z

- Richardson, L. (2021). Glitch feminism: A manifesto: By L. Russell, 2020, London, Verso, 178 pp., $14.95 (Paperback), ISBN, 978-1786632661 (Paperback). Gender, Place & Culture. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2021.1981638

- Rose, G. (2016). Cultural geography going viral. Social & Cultural Geography, 17(6), 763–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2015.1124913

- Russell, L. (2020). Glitch feminism: A manifesto. Penguin Random House.

- Simon, S., & Hoyt, C. L. (2012). Exploring the effect of media images on women’s leadership self-perceptions and aspirations. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16(2), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212451176

- Suitner, C., Maass, A., & Ronconi, L. (2016). From spatial to social asymmetry. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41(1), 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316676045

- Tiidenberg, K. (2018). Selfies: Why we love (and hate) them. Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781787543577

- Vivienne, S. (2017). “I will not hate myself because you cannot accept me”: Problematizing empowerment and gender-diverse selfies. Popular Communication, 15(2), 126–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2016.1269906

- Walker Rettberg, J. (2014). Seeing ourselves through technology: How we use selfies, blogs and wearable devices to see and shape ourselves. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661

- Wells, G., Horwitz, J., & Seetharaman, D. (2021). 2021 September 14. Facebook knows Instagram is toxic for teen girls, company documents show. The Wall Street Journal Retrieved 20 September 2021 from https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-knows-instagram-is-toxic-for-teen-girls-company-documents-show-11631620739

- Williams, A. A., & Marquez, B. A. (2015). The lonely selfie king: Selfies and the conspicuous prosumption of gender and race. International Journal of Communication, 9, 1775–1787. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3162

- Zawisza, M. J. (2019). Advertising, gender and society: A psychological perspective (First ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315144306