ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic represented a crisis that was handled in very different ways by different retailers. The purpose of this comprehensive empirical study is to explore how Swedish retailers adapted their retail formats, activities and governance over the course of the pandemic. Three types of adaptations were observed: adaptations in the physical store environment, new services connected to the physical store, and reduction of services connected to the physical store. We also found that the development of adaptations could be divided into three process steps: mobilization, operation (with adapted retail formats, activities and governance), and normalization. While literature tends to portray retail format development as proactive, carefully planned and top down, our findings suggest that the development undertaken in response to the pandemic was reactive and often bottom-up. Our findings also suggest that, in the wake of Covid-19, retailers can create value for customers by providing them with a novel kind of customer experience, a reassuring kind of customer experience in which safety and security are important elements.

Introduction

The perspective on retail format and store-service activities taken in this article is one we could not have imagined writing at the start of 2020. Although the first cases of a pneumonia of ‘an unknown cause’ were reported from China in December 2019, it was perhaps in January 2020 that declarations from the World Health Organization (WHO) made it clear that this was going to become much more than a local outbreak. By 11 March 2020 the consequences of the outbreak had reached far beyond China and Covid-19 was declared a pandemic. In the following weeks, many European countries introduced lockdown measures, restricting citizen mobility in extraordinary ways. Several European countries also took measures to force the closure of non-essential retail stores.

The societal restrictions and preventive measures adopted in Sweden in response to the pandemic were quite different from those adopted in most other European countries. The Swedish response to the pandemic was built on the principle of responsibility, which means that the party responsible for a particular activity under normal circumstances is also responsible for that activity in a crisis. Instead of imposing measures by mandate, such as nationwide lockdowns, the Swedish authorities advocated voluntary responsibility and entrusted members of society to make their own decisions on how to manage social distancing. In line with this approach, Swedish retailers made gradual, voluntary adaptations in their retail formats and store-service activities as the pandemic developed in 2020 and 2021.

Format and store-service development is not unusual in the retail industry and typically represents a proactive and strategic change in the retailer’s business model. Examples include the development, in recent years, of multichannel retail models (e.g., Berman and Thelen Citation2004; Jeanpert and Paché Citation2016) or store format adaptations (e.g., Egan-Wyer et al. Citation2021). Retail format development is, under normal circumstances, typically reactive, adaptive, incremental and may even be unnoticeable (e.g., Reynolds et al. Citation2007). However, the recent changes in retail format and store-service activities due to the pandemic situation in Sweden represent a departure from these norms. To meet new societal circumstances and to ensure that the retail store could be kept safe for both customers and store personnel, the format developments witnessed during the Covid crisis were both reactive and relatively radical. They were also, largely, voluntary in nature and, therefore, different from the mandatory format adaptations necessitated by, for example, local planning regulations (e.g., Sørensen Citation2004; Griffith and Harmgart Citation2005; Hallsworth and Coca-Stefaniak Citation2018) or national re-regulation of transnational corporations (e.g., Kim and Hallsworth Citation2013; Coe and Bok Citation2014; Nguyen et al. Citation2014; Theurillat and Donzé Citation2017). Due to the originality of Swedish society’s approach to the crisis, we find the Swedish retail context to be a particularly interesting empirical case with which to study voluntary format and store-service adaptation as a response to broad governmental recommendations (rather than specific and mandatory regulations) on social distancing.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the societal changes that followed (e.g., general health concerns and reluctance to engage in the close social encounters that would otherwise be part of everyday life) represented a global situation that was handled in very different ways by different retailers. Our key interest in exploring format and store-service adaptation in the wake of Covid-19 is to see what we can learn from behaviour by Swedish retailers during 2020 and 2021. The empirical base for our study of the Swedish retail landscape includes structured observations of retailer websites and store environments, and interviews with store managers at six major retailers in southern Sweden. Through a comprehensive empirical study of Covid-19 adaptations over time, we find three types of adaptations relevant to discuss and analyse: adaptations in the physical store environment, new services connected to the physical store, and reduction of services connected to the physical store. We also find that the development of adaptations can be divided into three process steps: mobilization, operation with adapted retail format and store services, and normalization.

Covid-19 and retail format development

Covid-19 has inspired a great deal of academic research, some of which relates to the effects of the pandemic and its associated restrictions and regulations on retail activities. Despite the relatively short time frames involved, research has been published concerning the effect of the pandemic on consumers’ perception of and attitudes towards safety measures in physical stores (e.g., Grashuis, Skevas, and Segovia Citation2020; Untaru and Han Citation2021), their changing attitudes towards online retailing (e.g., Dannenberg et al. Citation2020; Goddard Citation2020; Koch, Frommeyer, and Schewe Citation2020; Martin-Neuninger and Ruby Citation2020; Sayyida, Gunawan and Husin, Citation2021; Beckers et al. Citation2021), and their reactions to product shortages in grocery stores (e.g., Goddard Citation2020; Martin-Neuninger and Ruby Citation2020; Brandtner et al. Citation2021). Retail researchers have modelled and compared the potential spread of the virus in different shopping situations (e.g., Budd et al. Citation2021) and explored the role of retail-related technologies in keeping employees and customers safe during the pandemic (e.g., Heinonen and Strandvik Citation2020; Shankar et al. Citation2021). Others have analysed pandemic-related signage in retail stores (McNeish Citation2020). Few, if any, Covid-related studies have explicitly examined the effects of the pandemic on retail format over time, or retail format development in the wake of Covid-19 in particular, and it is in this area that the present article seeks to contribute.

It is well established that the format of the physical retail store can influence customer experience (e.g., Alencar De Farias et al. Citation2014; Bagdare and Jain Citation2013; Grewal, Levy, and Kumar Citation2009; Jack and Ling Citation2016; Rhee and Bell Citation2002). Retail managers have long manipulated in-store environments in the hope of creating distinctive (e.g., Verhoef et al. Citation2009; Alencar De Farias et al. Citation2014), extraordinary (Jahn et al. Citation2018), powerful (e.g., Dolbec and Chebat Citation2013), exciting (e.g., Sherry Citation1998; Sherry et al. Citation2001; Borghini et al. Citation2009), or simply more convenient (e.g., Egan-Wyer et al. Citation2021) shopping experiences. Gauri et al. (Citation2020) have previously suggested that retail managers choose between excitement or convenience when it comes to customer experience. Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, safety and security have become important new elements of customer experience. Retail managers have had to modify customer journeys to offer more reassuring customers experiences (e.g., Untaru and Han Citation2021), which has compelled them to adapt store formats and service in new ways.

Retailing has long (perhaps always) been subject to structural transformations of various kinds. Technologies such as railways, the automobile and the internet revolutionised the ways in which we shop (e.g., Christensen and Tedlow Citation2000; Nairn Citation2002) but changes in society, like urbanisation (e.g., Hultman et al. Citation2017) and the rise of consumer culture (e.g., Slater Citation1997; Sassatelli Citation2007) have had similar effects. Despite the growth of online and omnichannel retailing in recent years, the majority of customer transactions still occur in physical stores (e.g., Johansson Citation2018) and, therefore, the store format represents a key point of contact with customers (e.g., Reynolds et al. Citation2007). Format innovation that concerns the physical store has, hence, been seen as a way to achieve growth in a challenging retail landscape (e.g., Dawson Citation2000; Edelman & Singer, Citation2015), for retailers to differentiate themselves from competitors, to appeal to existing customers, and to target new segments (e.g., González-Benito, Muñoz-Gallego, and Kopalle Citation2005; Levy, Weitz, and Grewal Citation2014). Format development has been undertaken in a reactive manner in order to respond to changes in the retail landscape, such as urbanisation or technological progress (e.g., Hultman et al. Citation2017), or to make shopping more geographically accessible (e.g., Severin, Louviere, and Finn Citation2001; Jones, Mothersbaugh, and Beatty Citation2003; Jaravaza and Chitando Citation2013). It has also been undertaken more pro-actively in order to create new kinds of customer experience (e.g., Rigby Citation2011) or to create new touchpoints on a customer journey (e.g., Edelman & Singer, Citation2015).

The Covid-19 pandemic represents a novel reason for retail format development. During the pandemic, retailers were compelled to change the format of the physical store as well as the kind of service interactions they provided, suddenly and in response to societal uncertainty and distress. Alternative touchpoints on the customer journey were added or incentivised and the in-store experience was radically altered in order to protect customers and store employees from infection and in order to comply with public health recommendations. While retail stores in many other countries were forced to close for long periods during the pandemic, Swedish retailers were allowed to remain open and, hence, had to react rapidly and radically to adapt their format and service offerings. While radical retail format developments, such as rethinking established store formats (e.g., González-Benito, Muñoz-Gallego, and Kopalle Citation2005; Hultman et al. Citation2017; Egan-Wyer et al. Citation2021), tend to be proactively and carefully planned, the relatively radical adaptations undertaken by retailers in Sweden during the pandemic were reactive in nature and were executed quickly, thus representing a novel kind of format development.

As highlighted in Heinonen and Strandvik’s (Citation2020) study of Covid-19 as a catalyst for service innovations, severe disruptions can stretch businesses, forcing them to look beyond their existing strategies for innovative solutions. And the pandemic certainly proved to be a severe disruption. However, the pandemic also offered novel motivation for format development. Rather than developing format to increase transactions, turnover or profit, during the pandemic, retailers made format and service adaptations in order to reassure customers that they could continue to shop safely and securely in physical stores. In one way, this resonates with the development of experience-based store formats, such as themed brand stores (e.g., Sherry Citation1998; Borghini et al. Citation2009), flagship brand stores (Sherry Citation1998; Kozinets et al. Citation2002), pop-up stores (Niehm et al. Citation2007; Surchi, Citation2011; Picot-Coupey Citation2014; Robertson, Gatignon, and Cesareo Citation2018), and concept stores (Egan-Wyer et al. Citation2021), where the retail business model is developed, first and foremost, to enhance the emotional relationship between customers and retailer brands, with increased transactions being less important. However, the retail format development witnessed during the Covid-19 pandemic differs from the kind of format development associated with flagship brand stores, pop-up stores and concept stores in one important way. While both represent fairly radical departures from the status quo, the latter are well-planned and organised while the former have been executed in haste with little time for planning. Exploring how these radical and reactive format developments were handled by different Swedish retailers over time offers us a unique opportunity to better understand retail business model innovation and adaptation.

Retail business model adaptations

A business model is a detailed system of ‘interdependent structures, activities, and processes’ that organises the ways in which a firm creates value for customers and extracts value (for itself and its partners) (Sorescu et al. Citation2011:4). Business models grew in popularity alongside personal computers and spreadsheets, which made it easy to analyse assumptions and predictions in a scientific way and, hence, to model the business (Magretta Citation2002). While there is some overlap in the two terms, a business model is not the same thing as a strategy. A business model is strategy in practice (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart Citation2010; Gambardella and McGahan Citation2010). While a strategy articulates a goal, a business model articulates the details of how that goal will be achieved (e.g., Sorescu et al. Citation2011; Magretta Citation2002). And while strategy is focused on the firm’s external position relative to others in the marketplace, the business model is directed inwards towards the internal organisation (Cao Citation2014) and how it functions.

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, structural transformations to the retail environment, physical store closures (e.g., Grewal, Roggeveen, and Nordfält Citation2017; Helm, Kim, and Van Riper Citation2018), high customer expectations and fierce competition (e.g., Sorescu et al. Citation2011) meant that retailers needed to constantly adapt their business models to maintain a competitive advantage. Retail business model innovations, according to Sorescu et al. (Citation2011), involve changes to current practice in either retail format, retail activities or retail governance, which modify the organizing logic for creating and appropriating value. Retail format adaptations are changes in ‘the structures for sequencing and organizing the selected retailing activities into coherent processes that fulfil the customer experience’ (Sorescu et al. Citation2011:5). Adaptations in retail activities affect the ways in which goods and services are acquired, stocked, displayed and exchanged (Sorescu et al. Citation2011). And retail governance adaptations involve the actors that create and deliver customer experiences, for example, store personnel (Sorescu et al. Citation2011). Each of these kinds of adaptations clearly impacts the customer journey and the experience that the customer enjoys throughout that journey. However, they only fulfil Sorescu et al.’s definition of retail business model innovations if they are ‘new to the world’ (2011:7) and if they also modify the retail organisation’s logic for creating or appropriating value.

In order to comply with regulations and recommendations issued in relation to the pandemic, and in order to convince customers that their risk of infection while shopping was minimal, Swedish retailers made radical changes to their format and services within a relatively short period of time. In this article, we use Sorescu et al.’s concept of retail business model innovation to analyse how adaptations to retail format, retail activities, and retail governance affected the kinds of customer journeys offered by the retailers in our study. We also consider what kind of customer experience the adapted customer journeys engender as well as the kinds of value creation and appropriation they permit.

Method

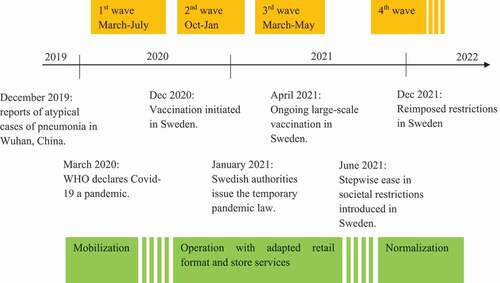

The aim of this study is to explore format, activity and governance adaptation in the wake of Covid-19, and to see what we can learn from the behaviour of Swedish retailers during the pandemic. To fulfil our aim, and to capture Swedish retailers’ behaviour during 2020 and 2021, we adopted a multiple case study methodology (e.g., Stake Citation1995, Citation2010; Yin Citation1994). In doing so, our primary objective is not to seek generalizations, but rather to provide credible and rich (e.g., Stake Citation2010) descriptions. By systematically structuring and analysing these descriptions, we are better able to understand the ways in which retail stores adapted their formats and service-offerings in the wake of Covid-19. The empirical base for our study includes structured observations of retail websites and store environments. It also comprises interviews with store managers at six major retailers with outlets in South Sweden: IKEA (home furnishing), Blomsterlandet (flowers, plants, and gardening equipment), Clas Ohlson (home improvement), ICA (groceries), Systembolaget (Swedish government monopoly on retailing of alcoholic beverages) and Dormy (golf equipment). The participating firms are a convenience sample of retailers that represent a variety of sectors that have outlets in southern Sweden and were, therefore, accessible to us for both physical visits and interviews during the pandemic. Empirical materials were collected at several points over an 11-month period (), providing us with a rich foundation for our subsequent comprehensive empirical analyses. Having empirical material that included repeated interviews and observations over a long period of time allowed us to analyse the material both chronologically and thematically and, thereby, to identify and observe steps in the process towards adaptations of the physical store.

Table 1. Retailers included in the study and observations/interviews made for the study

First, we made observations on the retailer’s website to get a good overview of the centralised, corporate response to Covid-19. These corporate responses were issued around mid-March 2020 and most of the retailers updated them continuously. The website observations were repeated in 2021. Second, we conducted six semi-structured interviews with store managers in southern Sweden. Due to the circumstances, we could not meet the store managers face-to-face, but instead conducted the interviews Microsoft Teams, with both audio and video transmission. The interviews, which were based on an open-ended question protocol were recorded with the participants’ permission. Using semi-structured interviews enabled us to have a clear direction in the discussion with respondents while the open-ended questions enabled us to reduce potential interviewer bias (e.g., Fontana and Frey Citation1994). The six interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes each and were conducted in June and August 2020. Third, we conducted store environment sweeps, i.e., store observations including photography. During the store sweeps we observed and photographed the store environment, focusing on store signage and format and store-service adaptation. Fourth, follow-up interviews were conducted with the store managers to discuss further adaptations and the developments after the second and third waves of infections in Sweden. The six follow-up interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes each and were conducted between January and April 2021.

Retailer’s format and store-service adaptation in the wake of Covid-19 – the Swedish case

In this section, we will report how the retailers from our study adapted their formats, activities and governance in the wake of Covid-19 (in 2020 and 2021). In contrast to many other countries, and in line with the principle of responsibility, the Swedish authorities encouraged and trusted the retail sector to adjust its own store operations to secure safety for both customers and store personnel. Despite criticism at home and abroad – of both the Public Health Agency (Folkhälsomyndigheten) and the assumptions on which it based its strategy – the Swedish Covid-response strategy did not initially impose any mandatory measures to ensure social distancing in the retail sector, although other societal interventions were later introduced (e.g., limit of crowds). During the initial phase of the pandemic there was a high degree of general uncertainty and distress in society, and this was reflected in retail. For example, in the grocery sector, we witnessed customers hoarding dry food, canned food, and other products like toilet paper. In other sectors, the number of store visitors dropped dramatically.

During the spring of 2020, the Swedish Trade Federation (Svensk Handel) issued industry regulations and guidelines for the retail sector at large. Specific guidelines for particular sectors were also issued. For example, the Swedish Food Retailers Federation (Svensk Dagligvaruhandel) issued guidelines for the grocery sector, which included measures that food retailers should take to ensure social distancing. At this initial stage, due to lack of experience and knowledge, retailers typically adopted local solutions to ensure personnel and customer safety. In January 2021, as a response to the second wave of Covid-19 cases, a temporary Covid-19 law came into effect. The new law included regulations that required retailers to keep track of the number of customers on their premises and to calculate that each visitor was afforded a social distancing area of at least 10 square metres. In July 2021, as part of a stepwise easing of societal restrictions in Sweden, the restriction on maximum number of customers was eventually lifted only to be partially reimposed again in December 2021 as Sweden suffered a fourth wave of Covid-19 infections.

Throughout the four waves of infections in 2020 and 2021 (), Swedish authorities continued to trust the retail sector to manage store operations in a way that would secure safety for customers and store personnel. Our interviews unanimously point at the criticality of the first phase from the time when Covid-19 was declared a pandemic until initial adaptations had been made in the store. During these first weeks of mobilization, there was high degree of uncertainty. For example, customers’ hoarding of grocery products challenged normal supply and inventory forecasts. Also, suppliers of hand sanitiser were not prepared for the sudden increase in demand. In some retail sectors, the number of customers visiting physical stores dropped significantly and there was unexpected pressure on other channels. Amid this uncertainty, retail managers rapidly developed local solutions in an attempt to reduce the risk of infection, ensure safety and stay in business. Our initial empirical investigation identified three types of adaptations to format, activities and governance that are relevant to discuss and analyse: (1) adaptations in the physical store environment; (2) new services connected to the physical store; and (3) reduction of services connected to the physical store. These are outlined in the following three subsections and are also detailed in . As retailers started to find their way in the Covid-19 pandemic, all three types of adaptations proved important. They not only helped to ensure the safety of customers and staff but also to reassure customers by convincing them that they could have a safe and secure customer experience in the physical store.

Table 2. Summary of adaptations

Adaptations in the physical store environment

Firstly, adaptations were made to the current physical retail format – i.e., the ways in which retail activities are sequenced and organised (Sorescu et al. Citation2011) – to ensure social distancing. We observed that the adaptations depended not only on the type of retail, but also on the nature of the store and how it was designed. Although retail format often sets the stage for store design (e.g., IKEA’s maze and store aisle configurations), local conditions (e.g., size and location of the premises) were also in play when retailers adjusted their stores to secure social distancing. For example, at the IKEA store in Älmhult, the checkout areas were adjusted with barriers and locks between checkout and queue, to avoid congestion. In the store, signage was used to help remind customers of their distance between themselves and store personnel and other customers. Here, IKEA’s well-known maze layout was already part of the store format, the one-way route helping to ensure that customers kept to one direction when walking through the store. Not all stores use a given, or suggested, walkthrough route as part of the retail format. In those cases, we observed how retail activities – the ways in which goods are stocked, displayed and exchanged – were adapted via the use of store signage (e.g., signs and barriers) and other types of support (e.g., voice messages, entrance hosts) to facilitate a safe walkthrough and entrance/exit. A store manager at ICA (groceries) commented:

Our store has a few places that can create crowds and therefore, in these places, we have worked with customer hosts. For example, our dairy department is a bit messy and crowded, and that is a place where we have asked our customers to wait outside and so on. […]. We have [also] reduced sales spots in the store to create more space and open floor. Our risk analysis showed that our fruit and vegetable department could create crowds, and that is an example of where we have reorganized some aisles and removed tables to free up more floor space.

As pointed out, the focus was on handling congestion areas in the store (i.e., points where distance was either unnatural or difficult to maintain, and where queues normally occur) and to make format and activity adaptations that facilitated the maintenance of a safe distance between store personnel and customers, and between customers in these areas. At the store’s information/service points, where staff-customer interaction is common, distance was secured with the use of plexiglass protection shields. A store manager at Clas Ohlson (home improvement) noted:

We rebuilt our check-out area. […] We noticed that we could have most of our customers waiting at the check-out, but not many customers in the rest of the store. […] It was a plan that we had initiated before the pandemic since we had one check-out point that was rarely used, but we were not allowed to do this since our plan did not square with the central store concept. We removed one check-out point to make it possible to partition off the check-out points. Otherwise, customers that were done with their business at the check-out could not pass through to the exit without getting too close to others and, thanks to the pandemic. we were allowed to do it. The change made it possible for us to free up floor space and secure distance with dividers in-between two opposite check-outs. […]

At golf equipment retailer, Dormy, where custom fitting and demonstration of golf equipment is at the heart of the customer experience, adaptations in hygiene and customer interaction routines were made in order to maintain services during the pandemic. The store manager explained:

Here, we do what we can to handle social distancing. We have implemented protective visors for all personnel working on the store floor. It has worked just fine, and our personnel are comfortable with this, and we have worked with visors for quite a while now. So, our work is focusing on distance keeping. Then again, we are not really policing this, and the customers need to take their responsibility as well, but we do what we can with signage and stickers on the floor. This thing with recommending the customers to shop alone … well, it does not really work but in our equipment testing area we restrict it to one person per booth. Otherwise, we work with recommendations and not with restrictions.

New services connected to the physical store

Secondly, and mainly to incentivise or encourage new customer journeys, retailers initiated additional or alternate store services. These new store services represent adaptations to both format and activities (Sorescu et al. Citation2011). Although several measures to ensure a safe retail environment for both customers and store personnel in the physical store had been taken early in 2020, the pandemic accelerated the pace of digitalization of the customer journey. In order to reduce the frequency of store visits and to attract customers who could not or would not shop in the physical store, several retailers took measures to adapt their retail format – the structures used to organise the retail process (Sorescu et al. Citation2011) – by steering customers towards e-commerce. They did so by offering price reductions on home delivery and various types of offerings that made it possible to avoid a visit to the physical store. Others took measures to reduce the time spent in the store, like click-and-reserve or click-and-collect both inside the store and outside the store (e.g., curb side delivery). A store manager at IKEA noted how their local solution to assist people that did not want to visits the store later was adopted by other stores in the group:

All the things we do have their origins on a local level. Our central service office offers a basic package with minimum requirements and if we need to add things because of local conditions, we will do that. Like where barriers are supposed to be in the store. […] The solution to offer curb-side delivery was hatched here in Älmhult and that solution was quickly implemented in the rest of Sweden.

While these retail format adaptations may not be considered innovations according to Sorescu et al.’s (2011) criteria – because they are not new to the world – they do represent a change in the value creation and appropriation logic employed by many retailers. Value is created for customers by creating new customer journeys in which they feel safe and protected. Furthermore, the removal of the physical store as a touchpoint for some customers did indeed lead to some ‘new to the world’ innovations. For retailers with physical stores, part of their competitive strength lies in the store services and interaction with staff offered there. They therefore needed to create new retail activities that mirrored service interactions previously experienced in the store. For example, Golf equipment retailer Dormy held online theme nights and IKEA offered free online planning services (e.g., kitchen planning). These new services represent adaptations to retail activities as well as to governance since personnel had to take on new tasks and manage new kinds of (digital) touchpoints. In several instances, our interviewees described how store personnel were reassigned to new tasks instead of being made redundant. These new tasks included, for example, supporting and guiding customers outside and inside the store, or working with e-commerce. A store manager at Systembolaget (alcoholic beverages) explained how new services connected to the physical store also meant a need for additional store personnel:

Before we had a definitive maximum of customers in the store, we needed to control that we did not have too many people at one point in the store. We had a queue system outside the store in place throughout the Christmas holidays, since we knew that this would be a busy time. If we had 15 customers in the store and all of them stood at the check-out, we let people in the queue enter the store, but 25 customers could be in the store without any problems. […] During Christmas, customers tend to buy the same things [e.g., mulled wine, beer], so customers linger at these shelves. Everything worked fine since we had a queue system and manned the barrier outside the store during these weeks. […] We manned the queue system with our own staff. Since we have had an increase in sales as well, we needed to man our store sufficiently to secure this function.

Reduction of services connected to the physical store

Thirdly, as some in-store activities involved close interaction with customers or created congestion in the store, retailers needed to consider and execute shutdown of store services. IKEA is well known around the world for its in-store restaurants and, from a customer experience point of view, restaurants, cafés and other sorts of refreshment offerings can significantly contribute to a positive customer experience and create longer visit times. However, alongside with the play area SMÅLAND, these services were temporarily shut down in 2020 in a radical and reactive retailing format adaptation (Sorescu et al. Citation2011). Among the retailers we studied, we observed several instances where store services were shut down or reduced. Bulky in-store campaigns needed to be removed to broaden aisles and to create a smoother and safer walkthrough for customers. In-store demonstrations, campaigns and play areas for children were either heavily restricted or temporarily shut down to avoid close interaction between customers and between customers and store personnel. A store manager at Blomsterlandet (gardening) commented:

All our store events have been cancelled, and they are usually quite popular. We usually run events on how to tie a wreath or a bouquet, how to best transplant or replant potted plants and so on. We usually have 70-80 customers at each of these events and run them every quarter. Our suppliers also do things, but right now their sales reps are not welcome here either.

In the physical store, the consultative role of store personnel cannot be underestimated with regards to co-creating and delivering a positive customer experience. However, during the pandemic, the interaction between store personnel and customers also needed to change. Staff were scripted to be less proactive on the store floor and instead trained to man the doors as entrance guards. A store manager at Systembolaget (alcoholic beverages) exemplified:

It is in our mission to work as good hosts for our customers, but now we are a bit more careful with proactivity on the store floor. When spotting a customer that is dilly-dallying, our job has previously been to walk up and ask if we can help. Today a customer might not appreciate that approach, since we might come up too close. Now, we try to be visible so that if the customer needs help, they can approach us.

The reduction of services connected to the physical store observed in this study demonstrate how adaptations in retail activity, format and governance are often linked. Removal of a service might include adaptations to retail activities (i.e., those that now no longer take place in the store) as well as adaptations to retail format (i.e., the addition of new, possibly digital, touchpoints to replace that service) and adaptations to retail governance (i.e., the preparation and deployment of personnel to alternative services or touchpoints). The reduction of services connected to the physical store may also challenge value creation logics in interesting ways. Removing a service may not typically be imagined as a way to create value for customers. However, when removing services leads to more reassuring customer journeys, value is indeed created for customers that are seeking safety and security in uncertain and distressing times.

Analysis and discussion

The process towards adaptations of the physical store environment during Covid-19 was not always straightforward. In our analyses, we have identified three steps within that process (). In the first step (mobilization), during and after the first wave of infections, retailers mobilized towards adaptations of the physical store. In the second step (operation with adapted retail format and store services), after the first wave of infections and through the second and third waves, retailers operated with adapted retail formats, activities, and governance. In the third step (normalization), as societal restrictions were sequentially lifted, retailers normalized their operations. The new normal, however, entails retaining several of the minimum requirements for retailers to secure a safe shopping experience, e.g., bottom-line adaptations to format, activities and governance as new features in the physical store. When identifying and discussing Covid-19 adaptations through these three steps, we also contribute to the literature on Covid-19 adaptations in the retail sector by addressing the challenges faced by retail management over time.

During the initial stages of the pandemic, there were few or no clear directions on how to make adaptations in the store environment. Therefore, adaptations in the mobilization step were often handled locally with provisional barriers and provisional signage, and several of our interviewees point at an interplay between local innovativeness and central steering. A store manager at IKEA (home furnishing) exemplifies:

Well, particularly in the beginning, we helped each other to find good examples. Both locally and centrally. […] Crisis groups have worked with this, and there has been a lot of communication between the local level and the national level, with exchange of ideas and actions to take. The more time has passed, the more the central level have been steering this.

This echoes McNeish’s (Citation2020) observation of ad-hoc signage in the early days of the pandemic. During this initial step of mobilization, store managers found support both through competitors and through nearby peers. As more central functions (e.g., crisis teams, regional management) were mobilized, standardized solutions began to be implemented (this is the step we call operation with adapted retail format and store services). Eventually, feelings of fragility and uncertainty (e.g., McNeish Citation2020) gave way to an appreciation of the new normal taking shape (normalization step). A store manager at Systembolaget (alcoholic beverages) commented:

During spring 2020, we had daily morning meetings with regional managers to get updates, and the regional managers had meetings with central management. This is how we figured out how to work in the stores, so that we all worked in the same way and there was coherence in how we worked. In these meetings, we addressed things like queue systems, hand sanitizer and so on. Early on, there was a crisis team that worked intensively with these matters, collected information, and did risk analyses that we then could work with locally. Initially, we had morning meetings every day but now there is organization in place and ways to stay informed about updates.

Our comprehensive empirical study of Covid-19 retail adaptations over time allowed us to observe the three different steps in the process. It also allowed us to see how these adaptations differed from typical retail business model innovations. While many of the changes made were based on recommendations stipulated and regularly adjusted by the Public Health Agency, retail managers also worked on their own initiative, at a local level to secure a safe retail environment. When a temporary Covid-19 law was enacted in January 2021, retailers were legally required to calculate the maximum number of customers allowed on their premises (allowing for a social distancing space of at least 10 square metres per visitor) and to track the number of customers entering and exiting in order to ensure that the maximum number was not exceeded. But, by then, most retailers already begun to voluntarily track and regulate the number of customers on their premises. A store manager at ICA (groceries) noted:

Early on, our sector [Swedish Food Retailers Federation] came up with a model for how to calculate a maximum, based on the square meter size of the premises. A good thing here was that we had a store in our network [an ICA peer] that already had a system for calculating customers in the store, and this made it possible for us to show how many minutes the average customer spends in the store and find a way to calculate a maximum for our store. We have found that we are never even close to this number. […] We have an average of perhaps 150 customers. […] Wednesday the day before Easter, we had a peak with 379 customers [the maximum number was eventually set at 500].

Literature tends to present radical retail format developments, such as rethinking established store formats (e.g., González-Benito, Muñoz-Gallego, and Kopalle Citation2005; Hultman et al. Citation2017; Egan-Wyer et al. Citation2021), as proactive, carefully planned and top-down. The changes in retail format, activities and governance we observed in response to the Covid-19 pandemic complicate this picture. While they were radical in many ways, they were also reactive in nature, with analysis following rather than preceding decision-making. And they were often bottom-up, with local retail managers making adaptations that were subsequently adopted on a national level.

Although the retail format, activity and governance adaptations that have occurred in the wake of Covid-19 are unprecedented, it is difficult to argue that they are retail business model innovations, according to Sorescu et al.’s (2011) strict definition, which requires that the innovations are ‘new to the world’ and also that they modify the retail organisation’s logic for creating or appropriating value (Sorescu et al. Citation2011, p. 7). The majority of the adaptations are not true innovations because they are not ‘new to the world’ (Sorescu et al. Citation2011, p. 7). Rather the pandemic encouraged wider adoption of formats and activities that existed prior to the pandemic but that were not very widely exploited (e.g., click and collect). It is for this reason that we refer to these changes as adaptations rather than innovations throughout this article. However, when it comes to the creation and appropriation of value, it is easier to make an argument for these adaptations as retail business model innovations. Rather than innovating to appropriate value from the market, the adaptations to format, activity and governance observed during Covid-19 were made to ensure store safety. But, as we have already highlighted, by creating and incentivising new customer journeys via format adaptations, reorganising retail activities, and defining and organising new tasks for store personnel – all of which aim to maintain safety and convenience – retail managers do, in fact, create a novel kind of value for their customers.

The retail managers that we interviewed seemed to instinctively appreciate Grashuis et al.’s (Citation2020) observation that customers are less willing to shop inside physical stores when Covid-19 rates are increasing, as well as Untaru and Han’s (Citation2021) findings that customers need to be constantly reassured that their health and safety is a priority. They, hence, created a novel kind of customer experience, one in which safety and security are important elements. This finding complicates discussions around retail format and customer experience (e.g., Egan-Wyer et al. Citation2021; Gauri et al. ; Hultman et al. Citation2017) by highlighting that customer experience may not only be about excitement (Sherry Citation1998; Sherry et al. Citation2001; Borghini et al. Citation2009), drama (Kozinets et al. Citation2002; Dolbec and Chebat Citation2013), or extraordinary branding (Jahn et al. Citation2018), nor even about convenience (Egan-Wyer et al. Citation2021). Rather, the creation of a reassuring customer experience may be equally or more important in certain circumstances.

During the pandemic, a key challenge for many retailers has been to reduce, replace or shorten store visits. By adapting store services that steered customers towards e-commerce, Covid-19 has contributed to an accelerated digitalization of the retail customer journey. This development has been particularly evident in the grocery sector, with increasing frequency of alternative solutions (e.g., click-and-collect). The study by Becker et al. (Citation2021) made a similar observation, by noting an increase in e-commerce in the sector during Covid-19. For retailers with a strong foothold in the physical world, however, this development is, in many ways, in stark conflict with many of the efforts to secure and incentivize visits to the physical store that retailers have struggled with in recent years. A store manager at ICA (groceries) noted:

In our line of business, we are used to attracting customers. I mean, we are trying to attract customers all the time; “Look here! We have cheap coffee! Today, we offer free cake!” And now, suddenly, we are instead supposed to tell our customers to keep their distance, and to not come to our store during certain times. This is not in our DNA. This has been very difficult, and we are still fumbling a bit. […] A lot of this … to not want customers in our store, that is not what we do. […] This has made store management a bit difficult when those responsible for driving sales ask me: “Are we not supposed to sell as much as possible?” And I have to reply, “Well yes, maybe, but not all the time.” […] To be better prepared, we need to have an internal talk about how to approach this in the future.

It remains to be seen what long-term effects the Covid-19 pandemic will have on customer journeys but the tension between the traditional desire to attract customers to the store and the current need to keep them away and to redirect customers to e-commerce, is extremely interesting. We expect that this tension will, eventually, have an impact on some of the taken-for-granted logics that inform retail management, for example that driving customer traffic to stores is the way to generate sales revenue or that proactive interaction between store personnel and customers is the best way to manage the customer experience in-store. It will almost certainly continue to accelerate the digitalization of many customer journeys. We encourage further longitudinal studies that explore this tension and how it plays out in potential future waves of the pandemic as well as in an eventual post-Covid retail landscape.

Conclusions

The Swedish case of responses to Covid-19 in the retail sector is unique since, while retail stores in many other countries were forced to close for long periods during the pandemic, Swedish retailers were allowed to remain open and hence, had to adapt their format and service offerings rapidly and radically. With a combination of local and central initiatives, and with industrial guidelines based on the recommendations stipulated and regularly adjusted by the Public Health Agency, Swedish retailers manoeuvred carefully in the face of the pandemic. They voluntarily adapted their focus on store selling and creating a positive customer experience (e.g., excitement, convenience, and other types of customer value) in order to focus on creating a safe and reassuring customer experience. In doing so, they created a new kind of value for customers that built on a quite different type of customer experience, one in which shorter visits, less interaction, and greater social distance were key elements.

When we completed the first draft of this article in September 2021, societal recommendations and preventive measures relating to the pandemic were almost completely lifted in Sweden but just three months later, Sweden experienced a fourth wave of infections and retailers were, again, required to keep track of the number of customers on their premises and to calculate that each visitor was afforded a social distancing area of at least 10 square metres. Our empirical investigation suggests that the retail sector is likely to keep or make permanent several of the adaptations to format and activity that were made in response to the pandemic. Even after the current wave of infections wanes, we are likely to continue to experience features like hand sanitation stations, plexiglass shields, signage to inform about social distance and other measures to ensure a concern-free shopping experience. They will form part of the retail manager’s toolbox of service adaptations that can be ramped up and down as required to reassure customers that their journeys are safe and secure. New services connected to the physical store and reduction of services connected to the physical store will endure. And touchpoints that were added to the customer journey during the pandemic will survive. Thus, the adaptations have become the new normal and represent permanent changes to the business model for many retailers.

The adaptations of the physical store environment during Covid-19, including new services connected to the physical store and reduction of services connected to the physical store, presented new challenges for store management in the retail sector. Firstly, retail store managers needed to reorganize store space to maintain safety and convenience for store personnel and customers. This reorganization also meant that store managers needed to define and organize new tasks for store personnel. A key observation here is that, during the pandemic, there was a clear shift in approach from store selling to store safety. Furthermore, ensuring store safety sometimes meant creating or incentivising new customer journeys, particularly ones that involved spending little or no time in the physical store. Since many of these adaptations seem set to become more permanent business model features, retailers will need to consider how, in the long-term, to integrate them into their well-established store formats in order to form new, adapted and contingent customer journeys.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jens Hultman

Jens Hultman is Professor in Business Administration with focus on marketing and retail at Kristianstad University. His research covers a broad area of retail challenges including retail format development, retail sourcing and retail sustainability.

Carys Egan-Wyer

Carys Egan–Wyer is a post-doctoral researcher at Lund University’s School of Economics and Management with a PhD in marketing. Her research interests lie at the nexus of consumption, retail and sustainability. Carys is also the deputy director of the interdisciplinary Centre for Retail Research, where she works to communicate cutting-edge retail and sustainability research to individuals and companies.

References

- Alencar De Farias, S., C. Aguiar, F. Vicente, and S. Melo. 2014. “Store Atmospherics and Experiential Marketing: A Conceptual Framework and Research Propositions for an Extraordinary Customer Experience.” International Business Research, [E-journal] 7 (2), 87–99.

- Bagdare, S., and R. Jain. 2013. “Measuring Retail Customer Experience.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 41 (10): 790–804. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-08-2012-0084.

- Beckers, J., S. Weekx, P. Beutels, and A. Verhetsel. 2021. “Covid-19 and Retail: The Catalyst for E-commerce in Belgium?” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 62 (4).

- Berman, B., and S. Thelen. 2004. “A Guide to Developing and Managing A Well‐integrated Multi‐channel Retail Strategy.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 32 (3): 147–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550410524939.

- Borghini, S., N. Diamond, R. V. Kozinets, M. A. McGrath, A. M. Muñiz, and J. F. Sherry. 2009. “Why are Themed Brandstores so Powerful? Retail Brand Ideology at American Girl Place.” Journal of Retailing 85 (3): 363–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2009.05.003.

- Brandtner, P., F. Darbanian, T. Falatouri, and C. Udokwu. 2021. “Impact of COVID-19 on the Customer End of Retail Supply Chains: A Big Data Analysis of Consumer Satisfaction.” Sustainability 13 (3): 1464. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031464.

- Budd, C., K. Calvert, S. Johnson, and S. O. Tickle. 2021. “Assessing Risk in the Retail Environment during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Royal Society Open Science 8 (5): 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.210344.

- Cao, L. 2014. “International Journal of Electronic Commerce Business Model Transformation in Moving to A Cross-Channel Retail Strategy: A Case Study.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 18 (4): 69–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415180403.

- Casadesus-Masanell, R., and J. E. Ricart. 2010. “From Strategy to Business Models and onto Tactics.” Long Range Planning 43 (2–3): 195–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.01.004.

- Christensen, C. M., and R. S. Tedlow. 2000. “Patterns of Disruption in Retailing.” Harvard Business Review 78 (1): 42.

- Coe, N. M., and R. Bok. 2014. “Retail Transitions in Southeast Asia.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 24 (5): 479–499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2014.977324.

- Dannenberg, P.M. Fuchs, T. Riedler, and C. Wiedemann. 2020. “Digital Transition by COVID‐19 Pandemic? The German Food Online Retail.” Tijdschrift voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 111 (3): 543–560. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12453.

- Dawson, J. 2000. “Retailing at Century End: Some Challenges for Management and Research.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 10 (2): 119–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/095939600342325.

- Dolbec, P.-Y., and J.-C. Chebat. 2013. “The Impact of a Flagship Vs. A Brand Store on Brand Attitude, Brand Attachment and Brand Equity.” Journal of Retailing 89 (4): 460–466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2013.06.003.

- Edelman, D, and Singer, M. 2015. Competing on Customer Journeys Harvard Business Review 93 11 88–100

- Egan-Wyer, C., S. Burt, J. Hultman, U. Johansson, A. Beckman, and C. Michélsen. 2021. “Ease or Excitement: Exploring How Concept Stores Contribute to a Retail Portfolio.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 49 (7): 1025–1044. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-10-2020-0407.

- Fontana, A., and J. H. Frey. 1994. “Interviewing: The Art of Science.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, ed. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 361–376. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Gambardella, A., and A. M. McGahan. 2010. “Business-Model Innovation: General Purpose Technologies and Their Implications for Industry Structure, Long Range Planning.” Pergamon 43 (2–3): 262–271.

- Gauri, D. K., Jindal, Rupinder, Ratchford, Brian, Fox, Edward, Bhatnagar, Amit, Pandey, Aashish, Navallo, Jonathan, R., Fogarty, John, Carr, Stephen, and Howerton, Eric. 2020. “Evolution of Retail Formats: Past, Present, and Future.” Journal of Retailing 41 (10): 790–804.

- Goddard, E. 2020. “The Impact of COVID‐19 on Food Retail and Food Service in Canada: Preliminary Assessment.” Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue Canadienne D’agroeconomie 68 (2): 157–161. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12243.

- González-Benito, O., P. A. Muñoz-Gallego, and P. K. Kopalle. 2005. “Asymmetric Competition in Retail Store Formats: Evaluating Inter- and Intra-format Spatial Effects.” Journal of Retailing 81 (1): 59–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2005.01.004.

- Grashuis, J., T. Skevas, and M. S. Segovia. 2020. “Grocery Shopping Preferences during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Sustainability 12 (13): 5369. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135369. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

- Grewal, D., M. Levy, and V. Kumar. 2009. “Customer Experience Management in Retailing: An Organizing Framework.” Journal of Retailing 85 (1): 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2009.01.001. JAI.

- Grewal, D., A. L. Roggeveen, and J. Nordfält. 2017. “The Future of Retailing.” Journal of Retailing 93 (1): 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2016.12.008.

- Griffith, R., and H. Harmgart. 2005. “Retail Productivity.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 15 (3): 281–290. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09593960500119481.

- Hallsworth, A. G., and J. A. Coca-Stefaniak. 2018. “National High Street Retail and Town Centre Policy at a Cross Roads in England and Wales.” Cities 79: 134–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.03.002.

- Heinonen, K., and T. Strandvik. 2020. “Reframing Service Innovation: COVID-19 as a Catalyst for Imposed Service Innovation.” Journal of Service Management 32 (1): 101–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0161.

- Helm, S., S. H. Kim, and S. Van Riper. 2018. “Navigating the “Retail Apocalypse”: A Framework of Consumer Evaluations of the New Retail Landscape.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 54.

- Hultman, J., U. Johansson, A. Wispeler, and L. Wolf. 2017. “Exploring Store Format Development and Its Influence on Store Image and Store Clientele – The Case of IKEA’s Development of an Inner-city Store Format.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 27 (3): 227–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2017.1314867.

- Jack, S., and C. Ling. 2016. “A Model Linking Store Attributes, Service Quality and Customer Experience: A Study among Community Pharmacies.” International Journal of Economics and Management 10 (2): 321–342.

- Jahn, S., T. Nierobisch, W. Toporowski, and T. Dannewald. 2018. “Selling the Extraordinary in Experiential Retail Stores.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 3 (3): 412–424. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1086/698330.

- Jaravaza, D. C., and P. Chitando. 2013. “The Role of Store Location in Influencing Customers’ Store Choice.” Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences 4 (3): 302–307.

- Jeanpert, S., and G. Paché. 2016. “Successful Multi-channel Strategy: Mixing Marketing and Logistical Issues.” Journal of Business Strategy 37 (2): 12–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-05-2015-0053.

- Johansson, Ulf, Ed. 2018. Framtidens Fysiska Butik [The Physical Store of the Future], Centre for Retail Research. Lund: Lund University.

- Jones, M. A., D. L. Mothersbaugh, and S. E. Beatty. 2003. “The Effects of Locational Convenience on Customer Repurchase Intentions across Service Types.” Journal of Services Marketing 7 (7): 701. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040310501250.

- Kim, W., and A. G. Hallsworth. 2013. “Large Format Stores and the Introduction of New Regulatory Controls in South Korea.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 23 (2): 152–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2012.754779.

- Koch, J., B. Frommeyer, and G. Schewe. 2020. “Online Shopping Motives during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Lessons from the Crisis.” Sustainability 12 (24): 10247. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410247.

- Kozinets, R. V., J. F. Sherry, B. DeBerry-Spence, A. Duhachek, K. Nuttavuthisit, and D. Storm. 2002. “Themed Flagship Brand Stores in the New Millennium: Theory, Practice, Prospects.” Journal of Retailing 78 (1): 17–29. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00063-X.

- Levy, M., B. Weitz, and D. Grewal. 2014. Retailing Management. 9th editio ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Magretta, J. 2002. “Why Business Models Matter.” Harvard Business Review 80 (5): 86–92.

- Martin-Neuninger, R., and M. B. Ruby. 2020. “What Does Food Retail Research Tell Us about the Implications of Coronavirus (COVID-19) for Grocery Purchasing Habits?” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1448. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01448.

- McNeish, J. E. 2020. “Retail Signage during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Interdisciplinary Journal of Signage and Wayfinding 4 (2): 67–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.15763/.2470-9670.2020.v4.i2.a64.

- Nairn, A. G. M. 2002. Engines that Move Markets: Technology Investing from Railroads to the Internet and Beyond. Wiley-Academy.

- Nguyen, H. T. H., Deverteuil, G., Wrigley, N., and Ruwanpura, K. 2014. “Re-Regulation in the Post-WTO Period? A Case Study of Vietnam’s Food Retailing Sector.” Growth and Change: A Journal of Urban and Regional Policy 45 (2): 377–396. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12043.

- Niehm, L. S., Fiore, A. M., Jeong, M., and Kim, H. 2007. “Pop-up Retail’s Acceptability as an Innovative Business Strategy and Enhancer of the Consumer Shopping Experience.” Journal of Shopping Center Research 13 (2): 1–30.

- Picot-Coupey, K. 2014. “The Pop-up Store as a Foreign Operation Mode (FOM) for Retailers.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 42 (7): 643–670. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-01-2013-0032.

- Reynolds, J., E. Howard, C. Cuthbertson, L. Hristov, and J. Reynolds. 2007. “Perspectives on Retail Format Innovation: Relating Theory and Practice.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 35 (8): 647–660. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550710758630.

- Rhee, H., and D. R. Bell. 2002. “The Inter-Store Mobility of Supermarket Shoppers.” Journal of Retailing 78 (4): 225–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(02)00099-4.

- Rigby, D. 2011. “The Future of Shopping.” Harvard Business Review 89 (12): 64–75.

- Robertson, T. S., H. Gatignon, and L. Cesareo. 2018. “Pop-ups, Ephemerality, and Consumer Experience: The Centrality of Buzz.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 3 (3): 425–439. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/698434.

- Sassatelli, R. 2007. Consumer Culture: History, Theory and Politics. London: SAGE Publications.

- Sayyida, S., S. Gunawan, and S. Husin. 2021. “View of the Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Retail Consumer Behavior.” Aptisi Transactions on Management (ATM) 5 (1): 79–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.33050/atm.v5i1.1497.

- Severin, V., J. J. Louviere, and A. Finn. 2001. “The Stability of Retail Shopping Choices over Time and across Countries.” Journal of Retailing 77 (2): 185–202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00043-4.

- Shankar, V., K. Kalyanam, P. Setia, A. Golmohammadi, S. Tirunillai, T. Douglass, J. Hennessey, J. S. Bull, and R. Waddoups. 2021. “How Technology Is Changing Retail.” Journal of Retailing 97 (1): 13–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.10.006.

- Sherry, J. F., Jr. 1998. “The Soul of the Company Store: Nike Town Chicago and the Emplaced Brandscape.” In Serviscapes: The Concept of Place in Contemporary Markets, ed. J. F. Sherry Jr., 109–146. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Business Books.

- Sherry, J. F., R. V. Kozinets, D. Storm, A. Duhachek, K. Nuttavuthisit, and B. De Berry-Spence. 2001. “Being in the Zone.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography Sage Publications 30 (4): 465–510. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/089124101030004005.

- Slater, D. 1997. Consumer Culture and Modernity. 1997. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Sørensen, M. T. 2004. “Retail Development and Planning Policy Change in Denmark.” Planning Practice and Research 19 (2): 219–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0269745042000284430.

- Sorescu, A., R. T. Frambach, J. Singh, A. Rangaswamy, and C. Bridges. 2011. “Innovations in Retail Business Models.” Journal of Retailing 87 (1): 3–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2011.04.005.

- Stake, R. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Stake, R. 2010. Qualitative Research: Studying How Things Work. New York: Guilford Press.

- Surchi, M. 2011. The Temporary Store: A New Marketing Tool for Fashion Brands Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 15 2 257–270

- Theurillat, T., and P.-Y. Donzé. 2017. “Retail Networks and Real Estate: The Case of Swiss Luxury Watches in China and Southeast Asia.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 27 (2): 126–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2016.1251954.

- Untaru, E.-N., and H. Han. 2021. “Protective Measures against COVID-19 and the Business Strategies of the Retail Enterprises: Differences in Gender, Age, Education, and Income among Shoppers.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 60: 102446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102446.

- Verhoef, P., K. N. Lemon, A. Parasuraman, A. Roggeveen, M. Tsiros, and L. A. Schlesinger. 2009. “Customer Experience Creation: Determinants, Dynamics, and Management Strategies.” Journal of Retailing 85 (1): 31–41. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2008.11.001.

- Yin, R. K. 1994. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.