ABSTRACT

Introduction and Aims

Professionals working abroad as part of a partnership program is a central act of internationalization among higher education institutions. Little research has been carried out on this topic. The goal of this study was, therefore, to explore, describe and discuss the workplace learning factors – especially cultural factors – influencing Norwegian physiotherapy teachers, working in an international partnership project at a women’s university in Sudan.

Methods

The study had a qualitative case-study design, intended to provide an in-depth understanding of workplace learning processes. We used a multifaceted approach which included individual interviews and document analyses.

Results

We identified individual, social and institutional factors that influenced workplace learning. Culture is decisive at all levels, and knowledge, skills and attitudes are culturally situated. The Norwegian teachers’ learning was found to be dependent on both internal and external factors and the pre- and post-project periods.

Conclusion

This study shows that a workplace perspective on the experience of Norwegian physiotherapy teachers gives us a better understanding of the important factors, associated with such a project. Working abroad not only requires preparation on the part of the sending and host institution but also from the person working abroad (prior to, during and after the stay abroad) if workplace learning is to occur.

INTRODUCTION

Teachers working abroad as part of a partnership program is a central act of internationalization among higher education institutions. This presupposes teachers’ mobility and ability to function independently of the workplace context (Méda, Citation2016; Olsen and Tikkanen, Citation2018). Being a foreigner in a host country is associated with psychological distress and decreased well-being, due to sociocultural, environmental and lifestyle differences (Bhugra, Citation2004). Despite these difficulties, working abroad provides opportunities for personal and professional development (Aalto et al., Citation2014; Altun, Citation2015). Haugland, Sørsdahl, Salam Salih, and Salih (Citation2014) and John et al. (Citation2012) have described factors leading to success in partnerships between higher education institutions in high- and low-income countries, aimed at establishing physiotherapy education in the low-income countries. None of these studies considered the experiences of physiotherapy teachers. Rodríguez (Citation2011) found that teachers who went to Bolivia from America reported improved abilities in cultural, global and educational domains. Doki, Sasahara, and Matsuzaki (Citation2018) in a systematic review identified a range of stress factors that affected foreign-born workers working abroad. Six challenging components from the review included the following: 1) communication; 2) cultural differences in the workplace; 3) daily life; 4) relationships with family and colleagues; 5) financial problems; and 6) social inequality. Consequently, acculturation and occupational stress are more frequently observed in foreign-born workers (Doki, Sasahara, and Matsuzaki, Citation2018). By looking more closely at contextual factors, one might identify the cross-cultural perspective and avoid defining experiences solely from one perspective (usually a Western perspective) (Jentsch and Pilley, Citation2003). This would enable a partnership institution to develop a more satisfactory cross-cultural working environment, suitable for all workers, regardless of their cultural background. In light of these findings, it would be important to further understand the personal, institutional, social and cultural factors, involved in international partnership programs.

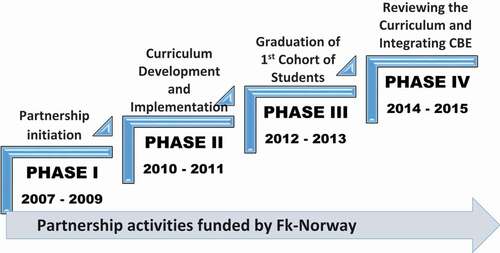

In this case study, we explored Norwegian physiotherapist teachers’ (NPTs) experiences of working at a university in Sudan. In the early 2000s, Sudan did not offer any entry-level physiotherapy programs, and there were few physiotherapists working in the country at this time (Haugland, Sørsdahl, Salam Salih, and Salih, Citation2014). The Sudan-Norwegian partnership was established (at the request of the Sudanese partner) in order to develop an internationally recognized five-year bachelor-level physiotherapy program. The project continued for nine years (2007–2015), during which time four distinct phases of the educational program were achieved ().

Figure 1. Model of the different phases of the Norway – Sudan partnership project on physiotherapy education.

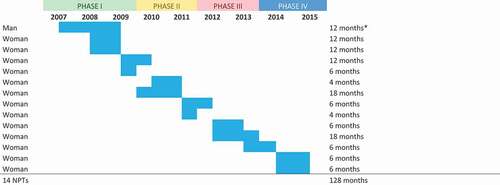

The first three phases: 1) partnership initiation; 2) curriculum development and implementation; and 3) graduation of the first cohort of students were implemented by the two founding partners from Norway and Sudan. Two additional African partners subsequently joined the fourth phase, which was intended to expand the collaboration and enable the NPTs to transfer their experience of integrating community-based education (CBE) in the physiotherapy degree curriculum of the Sudanese. Teachers from all institutions were employed in the execution of the project activities across the four phases. NPTs worked annually in pairs at the Sudanese institution for a period of six to 18 months (Haugland, Sørsdahl, Salam Salih, and Salih, Citation2014) ().

Figure 2. Model of the length of stay for each NPTs involved, distributed on phases.

Sudan University Context

The university is located in Omdurman, one of the biggest cities in Khartoum State (Khartoum being the capital of Sudan). The university only enrolls female students, but the staff comprises both male and female teachers. Arabic is the most common language in the country but the language of instruction and official communication at the university, is English. The university operates six days a week, with the exception of Friday. At the university, there is a dress code; male teachers wear Western attire, and female teachers wear a thobe (a long piece of cloth wrapped around their inner garments) with a long scarf draped around their head. Most students wear a long scarf in addition to Western attire, and some wear the abaya (a robe-like dress) and a niqab (a veil face covering). The legal system in Sudan is based on Islamic Sharia law. The climate in the university area is tropical with sandstorms, which can completely block out the sun.

The Physiotherapy Department is located in a building adjacent to the main university campus. The department occupies the first and second floors of the building and is made up of the administration offices, an open-plan faculty office, classrooms and gyms in addition to the main service facilities. Each classroom can accommodate up to 30 students and is equipped with a multimedia projector, a blackboard and a ceiling fan. Internet access is limited with poor connectivity.

Institutional Obligations and Expectations

Norwegian teachers were employed as part of the partnership project. They were the only physiotherapists at the Sudanese university shouldering full professional duties during the project period. Their work tasks consisted of three main elements: curriculum development, teaching and tutoring students in clinical practice.

Learning in the Workplace

The NPTs’ experience of a workplace setting in a foreign country such as Sudan, with diverse linguistic, ethnic, social and cultural characteristics, was likely to be very challenging (LaVerle, Citation2015). Teachers who work abroad are expected to adapt to the country in which they are working and to the workplace culture, and they are also expected to understand specific workplace needs. This adaptation process which is often informal and subconscious can be described as a workplace learning process, and it occurs while working (Cacciattolo, Citation2015; Cairns and Malloch, Citation2011; Illeris, Citation2018; Olsen and Tikkanen, Citation2018). Learning takes place in a dynamic context that includes individuals’ learning processes and social activity (Cacciattolo, Citation2015; Illeris, Citation2004; Patton, Higgs, and Smith, Citation2013). Learning in the workplace depends on the individual and his/her role as an active, legitimate participant in the setting, previous experiences, motivation and orientation toward self-determination for learning (Illeris, Citation2018A; Ryan and Deci, Citation2000).

NPTs working abroad are placed in a new institutional, social and cultural context. They also had to learn and practice their physiotherapy knowledge, skills and competence in another setting. According to Billett and Choy (Citation2013), although individual engagement in workplace learning is essential, it is important to elaborate on the mediating factors of situation, society and culture that underlie the knowledge, skills and competence, required for work. It is critical to understand the relationship between personal and cultural contributions with regard to learning for and through work (Billett and Choy, Citation2013; Tomasello, Citation2004). When the NPTs’ learning is regarded as a social process of change in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes, workplace learning can be described as a reflective process, involving interaction between the NPTs and relevant others in the communities where the process is taking place (Vågstøl and Skøien, Citation2011). In every organization, there are usually several working communities, defining how people participate, what is useful knowledge, who should possess and retain useful knowledge and how new knowledge is acquired (Billett and Choy, Citation2013). Relevant people from whom the NPTs in our study could learn, included colleagues, teaching assistants, workers in the clinical environment and students. This learning depended on their efforts and capacities as observers, imitators and initiators (Billett and Choy, Citation2013) and required reflective thinking (Patton, Higgs, and Smith, Citation2013). Through reflection, the NPTs could gain knowledge relating to a confusing situation, to clarify their understanding and enable coherent and professional growth to occur (Patton, Higgs, and Smith, Citation2013). The purpose of this case study was to explore, describe and discuss the workplace learning factors especially cultural factors influencing the NPTs working on an international partnership project at a women’s university in Sudan.

METHODS

Design

A case-study design was used to explore the NPTs’ workplace learning at the chosen Sudanese university. The case-study design structure provided a framework, bounded by time and activities, and facilitated collection of detailed information through multiple data collection procedures, over a sustained period of time (Creswell and Creswell, Citation2018). The current study provides an in-depth exploration of the complex processes, assumed to be involved in a cross-cultural partnership. Data collection methods included individual interviews and an analysis of multiple documents (i.e. NPTs’ monthly and final reports, project reports and minutes from partnership meetings) ().

Table 1. Case study data collection and types of information.

Data Collection

This study observed the relevant ethical standards and was conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study received approval from the Norwegian partner and the Norwegian Center for Research Data (NSD, RK-265945). The recordings and transcriptions were saved according to current ethical guidelines, and all data were safeguarded by anonymity. All the NPTs were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time and that the data would be used for publication. Written consent was given by all those interviewed. The NPTs also consented to the use of their reports for the purposes of publishing our findings in international journals.

Five NPTs were interviewed during a conference that they attended in 2017 in Norway. All NPTs were invited, but only five were able to attend. They had worked abroad at different times and during different phases of the project (). A researcher who had not been involved in the planning and implementation of the project conducted the interviews. The interview guide was semi-structured with the following interview categories: 1) preparation for work abroad and for resuming work in Norway; 2) work at the university; 3) cultural challenges encountered during the NPTs’ free time and 4) collaboration with the host, sponsoring institution and coworkers. This relates to our understanding of workplace learning as involving a relationship between personal and cultural contributions for and through work in a given context (Billett and Choy, Citation2013; Tomasello, Citation2004). The interviews were recorded and transcribed.

All NPTs were required to write mandatory reports for the host and sending institutions, sharing their thoughts, feelings and learning experiences, associated with their work and stay in Sudan, resulting in the compilation of a database of 104 written documents. In total, the NPTs created 91 monthly reports during their stay abroad and 13 final reports immediately after their stay. In addition, the research team also reviewed project reports and minutes of meetings, documenting important strategic management procedures, considered during the project period ().

Norwegian Teachers

There were 13 NPTs involved in this project (all but one of whom were women), who had been employed for a period of between six and 18 months (). They all had a bachelor’s degree in physiotherapy, which is the requirement to become an authorized physiotherapist in Norway. One was an associate professor and four had a master’s degree in physiotherapy. All the NPTs worked in pairs. Two resigned after four months for personal reasons. All the NPTs had a clinical background and 11 had no experience of teaching in a higher education institution (HEI). Two of them were working at the Norwegian university when they became involved in the project. All of them had experience of supervising students/patients. All the NPTs enrolled on Arabic language courses upon their arrival in Sudan.

Data Analysis

The principles of systematic text condensation were used in our analysis of the interviews and reports (Malterud, Citation2011, Citation2012). The analysis followed four steps, as follows: 1) getting an overall impression and identifying themes (i.e. investigator triangulation) (Patton, Citation2015); 2) identification of meaning units (i.e. grouping and coding of these); 3) identification of sub-themes in each group (i.e. abstraction of individual meaning units to meaningful wholes and the creation of a condensed first-person narrative with a quote to illustrate what appeared in the categories); and 4) description of the NPTs views based on the condensation forming the results presented.

The first analytical phase was carried out individually by two researchers, and then another round of analysis was completed with the researchers working together. To ensure that the analysis and results were consistent with the overall impression of the data, the researchers read the text in all four steps and carried out the coding several times. The transcribed interviews were in Norwegian and the rest of the data were in English. The translation into English took place between steps three and four. An example of the abstraction process is presented in .

Table 2. Example of the abstraction process; meaning units, code, themes and subthemes.

RESULTS

Our multifaceted analytical process revealed themes and subthemes underpinning experiences essential to the workplace learning processes in this international partnership project in Sudan (). Seven distinct themes of working abroad are shared here.

NPTs’ Motivation for Working Abroad

According to the NPTs, their motivation was a long-established desire to work abroad, a sense of adventure, cultural curiosity, a wish to meet people from another background and to face a new set of work challenges. They felt they could use their education and work experience in this meaningful project, giving them both a challenge and a sense of security. They also emphasized that the length of their stay and the timing were right.

Preparation for Life in Sudan

The NPTs prepared for their work abroad by talking to the leaders and former employees of the project. They also completed a preparatory course organized by Fk-Norway, the organization that funded the project. Conversations with leaders were crucial in familiarizing the NPTs with the project and to clarify roles and expectations. The preparatory course supported the transition from home culture/work to the new setting by giving the NPTs the opportunity to learn about living in a foreign culture, and to appreciate the key differences between themselves and others (as well as the opportunities these differences presented). All the NPTs stated that despite their preparation, Norway was so different from Sudan that it was difficult for them to comprehend the scope of living in such a hugely different culture. One particular concern was the practical problem of living in such a different climate. The NPTs who completed the program felt that conversations with previous NPTs prepared them quite well for life in Sudan.

Social Life

On arrival in Sudan, the NPTs needed practical help with housing, shopping, transport, their visas and their telephones, which was provided by the university. They did experience a culture shock, but this decreased over the course of their stay. They described the practical problems as more distressing at the beginning, and the fact that this frustration was often limited to the initial period of adjustment but was in line with their expectations. However, they maintained that this hardship led to personal growth for most of them, enabling them to understand more about themselves, as well as another culture, as they processed their feelings and realized how resilient they were.

Many NPTs described busy working days, affording them little time for socializing. Certain NPTs socialized with students outside the university, expressing how this gave them a valuable insight into the life of young people in Sudan, as well as exposing them to Sudanese culture. A number of the NPTs expressed a sense of isolation and loneliness after work, with few local friends, even though after a while, they began to participate in various leisure activities. Their friendships were mostly with other foreign-born workers. Furthermore, it was difficult for them to engage in their usual leisure activities (e.g. workouts and other forms of exercise).

Building an Academic Community

At the beginning of the project period, there was no academic community specifically for the physiotherapy program; the primary relationship was with the general university community. The NPTs were included in meetings, social events and everyday life at the university, which seemed to decline as time progressed. However, as the educational program developed, it formed the basis for the most important relationships for the NPTs. At the outset, regular meetings were not held with the program manager and other staff, working on the physiotherapy program. The NPTs also indicated that scheduled meetings might be canceled at very short notice, or people did not turn up, making information sharing and future planning difficult. They also stated that the program leader, as well as other employees involved in the physiotherapy program, were sometimes so busy with other projects that there was no time for meetings and communication about relevant tasks. The NPTs did note, however, that the leader assumed responsibility when he/she attended meetings and took any follow-up action that had been agreed upon. A number of NPTs signaled that they were unaware of which member of staff to approach for any relevant information. This created a degree of confusion and disarray among the NPTs in relation to administrative procedures and exams, etc. Moreover, they felt that they needed a key contact within the university to inform them about rules and regulations; several NPTs expressed how the dean’s involvement in meetings resulted in a positive change.

Navigating Complexity and Challenge

The specific challenges that the NPTs experienced were related to their own competence, technical-institutional problems at the university and students’ requirements.

Competence

Only a few of the NPTs had undergone pedagogical training at an HEI, but the NPTs had developed mentoring competence as a result of training physiotherapy students and working with patients. Those without HEI training felt that they were at a disadvantage because of their lack of HEI experience and had to ask for help periodically. Local teachers with physiotherapy knowledge had neither the time nor the insight into central curriculum topics, and there was no academic community within which to discuss challenges. The NPTs’ teaching was based on their own experience and Norwegian ideas of teaching, which meant an emphasis on interaction and reflection both in class and in practice. The other Norwegian teacher in each pair was a discussion partner, and NPT partners tried to support and encourage one other, a dialogue which several also felt they needed with their home institution. All NPTs felt that the hot climate negatively impacted on their ability to carry out daily tasks. Most of the NPTs worked in the clinic to increase their knowledge of the way in which physiotherapy was provided in the local context, and to learn about local conditions, challenges and patients’ way of life.

Technical-Institutional Problems

NPTs complained of problems associated with having to start from scratch on every course (i.e. timetable, materials, and exams) and problems with placements (having access to a sufficient number of sites and securing supervisors). The project had no system of passing on the work that previous NPTs had undertaken. Other challenges that were often mentioned related to administration and roles and responsibilities (e.g. developing a handbook for placements, course outlines, exam administration, evaluation of exam conformity with the most recent course outlines, and grading procedures). Each teacher organized his/her own internet-based system, most of which functioned reasonably well. However, the internet was poor, making it more difficult to systematize teaching materials, as well as restricting access to and information flow between teachers and students. The university had a system for examination, grading and the requirements for promotion to the next level, which the NPTs believed did not complement sufficiently either the academic requirements or student quality requirements. The university agreed on a compromise, provided that the education was considered as a project and the NPTs were involved. Systematic planning changed somewhat after new quality assurance systems were introduced, with the university leadership giving more direction to the educational program.

Students’ Requirements

All NPTs noted that their students had to meet certain requirements, not considered mandatory among other faculties, such as meeting on time, active engagement in order to experience first-hand how training functioned, having to change into shorts and a T-shirt for the purpose of practicing skills on one another and having exams that tested knowledge beyond mere rote learning. Students were also required to practice skills outside class. The students’ level of English varied, even though English was the lingua franca of the university, which was a challenge in class.

Sense of Time – Culture Matters

Norwegian and Sudanese teachers were conscious of the different perceptions of time, especially with regard to task planning, organizing meetings and classroom teaching. These differences in attitude toward time influenced most of their work tasks. Teachers and students might come in late, resulting in the students having less teaching time if the next class were to start on time. It was not clear to the NPTs whether this was unprofessional behavior or accepted culture. They were also concerned that students were not given the education needed to pass their exams and become skilled physiotherapists. Some claimed that the NPTs’ ideas of task planning differed from those of other staff. Certain factors which made it difficult to plan in good time were the unforeseen external factors, such as riots, power and water losses, and unpredictable events at the hospital during the students’ practice period. Another cultural challenge arose when the NPTs tried to organize the overseeing of the entire program by the Sudanese. The latter did not have the same sense of urgency and were more relaxed, believing that everything would work out well. The allocation of responsibility was a challenge when the NPTs identified an area that should have been planned for previously, but which had not yet been addressed. They noted that there was a difference between taking on responsibility and discussing what and when something should be done.

Finalizing the Job – Preparation for Reentry

Following their stay in Sudan, many of the teachers had a desire to tell the story of their life in Sudan. It was also crucial for them to have discussions with others who had been involved in the project in order to detect common problems. The NPTs noted that they needed ample time (several weeks) to work through their stay, thinking, reviewing, communicating and making notes. This reflective process made it easier to finalize the job as they prepared to reenter their home culture. The NPTs found that they were making other choices after reentry into Norway. They also found that they had more understanding of various diseases, different roles and family circumstances, even among people living in Norway. Therefore, they took a different approach when they treated patients, especially patients from a non-Norwegian, ethnic background.

DISCUSSION

This discussion is based on the assumption that teachers who work abroad are expected to adapt to the country in which they are working and to the workplace culture; they are also expected to understand specific workplace needs and the workplace learning process. shows the recommendations for similar practices, based on this discussion.

Table 3. Recommendations for physiotherapy teachers in similar practices.

According to the “Self-determination for learning theory” (SDT), autonomy, relatedness and perceived competence are important in terms of regulations remaining integrated rather than introjected (subject to approval from others) and are a precondition for learning (Bondevik et al., Citation2015). Our results show that the NPTs felt that the university respected them and their competence, which gave them confidence as individuals to perform their job. This may be taken as an indication that they experienced relatedness to the university and the faculty (Table 3.1).

Most current research explores the changes in culture experienced by students and migrants arriving in a Western country to either study or work (Cervantes, Fisher, Padilla, and Napper, Citation2016; Doki, Sasahara, and Matsuzaki, Citation2018; Zhou, Jindal-Snape, Topping, and Todman, Citation2008). This study confirms that Norwegians going to work in Sudan also experience cultural challenges, despite undertaking the relevant preparatory activities. Zhou, Jindal-Snape, Topping, and Todman (Citation2008) identified that the culture shock could be lessened by good preparation. We observed that when those responsible for the project both in Norway as well as Sudan prepared the NPTs better (i.e. as the project drew to a close), the NPTs had fewer practical problems both at work and in their spare time, but they still experienced a culture shock (Tables 3.2). A culture shock is associated with being a member of a community, a sense of belonging and undertaking legitimate peripheral participation (Lave and Wenger, Citation1991; Sfard, Citation1998). Sfard (Citation1998) also claimed that this critical process of becoming a member of a community involves its language and norms, not just knowledge mastery or the discussion of work tasks. This also involves having one’s norms and values challenged, especially through a process of cultural embeddedness (Table 3.3). To gain a deeper understanding of the various concepts used, one needs to live within the culture in question, thus moving from knowledge to knowing. The culture shock decreased during the NPTs’ stay, which may indicate that they were on a trajectory to full legitimate participation. However, the fact that they mostly made friends with other foreigners might suggest that they had still not become full members of the community.

The NPTs’ norms and values regarding physiotherapy education and the academic community were also challenged. This negotiating was challenging for both the NPTs as well as the faculty at the university, especially since many of the NPTs challenged the Sudanese university system (Table 3.4). The NPTs did not fully comprehend the written or unwritten culture at the university. One reason for this could be that few of the NPTs had an academic background and therefore, did not understand the university laws and regulations. In addition, the NPTs did not have sufficient or clear dialogue with the relevant people and felt that they needed to adapt to regulations which were not clear to them. Another reason could be the different views in relation to the tasks that needed to be completed and the timing of these. Amidst such a conflict, it was a necessary precondition for co-existence that all parties trusted and desired the best for one another (Harden, Citation2001). In the case of the NPTs, this posed a dilemma as to whether to increase their own workload to ensure tasks were completed within their own timelines and/or be open to a different way of working. This could also be viewed as an unclarified responsibility (Tables 3.5–3.9).

The goal of this project was to develop an educational physiotherapy program in Sudan, run by the university and in accordance with international standards. As the NPTs were working under pressure (too little time, extreme heat and limited coverage of central topics due to a lack of qualified teachers), they often relied on teaching methods that were familiar to them. We do not know to what extent pedagogical training from Norway would have helped the NPTs, since the students had to change their learning methods from routine, skill-based learning to more in-depth learning that also included reflection. Mulder and Gulikers (Citation2011), Biemans et al. (Citation2004) and Birenbaum (Citation2003) all described the difficulties of changing students’ learning methods, which are the same in a number of African countries and differ from Norwegian pedagogy with its emphasis on reflection from the commencement of study.

The NPTs mainly conducted their reflection together with their coworkers from Norway during the course of their work. Those who had experience of teaching physiotherapy in an HEI also acted as advisors for less experienced NPTs. There were few, if any, local physiotherapy teachers at the university during the period when the NPTs were based there. This lack of cultural knowledge in discussion deprived the NPTs of a certain depth of understanding, of a deeper learning of physiotherapy in the local context and the opportunity to solve work tasks in ways other than they would have done in Norway. Since the reflection was conducted by people using the same frame of reference, there was less risk of misunderstanding. Pedagogical, social and work tasks in the clinical placements were discussed with locals, and this gave them the opportunity to consider alternative interpretations of their experiences (Engeström, Citation2011) (Tables 3.10–3.11).

The NPTs continued to engage in this reflective process when they returned home. This created an analytical distance, and they were able to verbalize their thoughts, explore and understand their feelings and their learning (Patton, Higgs, and Smith, Citation2013) (Table 3.12). The most important change they highlighted was that they managed to contribute to developing and running a physiotherapy program in another culture. They obtained knowledge of different communities in Sudan and at the university, and they managed to adapt their Norwegian physiotherapy knowledge and skills to the Sudanese context. They experienced attitudes and values in Sudan which they wished to integrate into their way of life and working practices in Norway.

Strengths and Limitations

The use of a case-study design made it possible to explore in depth and over time the workplace learning of NPTs in a partnership project in an HEI, aimed at building an educational physiotherapy program in a Muslim country where no such education existed and where few physiotherapists worked. Since there are, to the best of our knowledge, no studies focusing on physiotherapy teachers’ experience, it was important for us to gain an insight into the complex processes, assumed to be involved in a cross-cultural partnership. By looking specifically at one case, we cannot generalize our recommendations in relation to all such partnerships. However, our recommendations can give other partnerships and people working abroad an insight into the challenges they might face (Patton, Citation2015).

CONCLUSION

This study shows that a workplace perspective on the experience of NPTs enhances our understanding of the individual, social and institutional factors which are important for such a project. In addition, it reveals the impossibility of separating these factors from culture. Culture is decisive at all levels, and knowledge and competence are culturally situated. Therefore, the work of physiotherapy teachers cannot function independently of the workplace context.

We found several factors related to learning for work and learning through work, which are important for physiotherapy teachers working abroad and for designing such a partnership. Moreover, our study shows that working abroad requires preparation on the part of the sending and the host institution, and on the part of the person working abroad – before, during and after the stay. However, the study also shows that it is possible to have a partnership for the purposes of an exchange of teachers within an HEI, and that such a partnership can be beneficial for both partners in terms of building capacity and education across cultural borders. This study can also serve as a model for exploring the determinants of working abroad in other partnerships.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to all the Norwegian physiotherapy teachers for allowing us to use their reports and for letting us interview them.

References

- Aalto AM, Heponiemi T, Keskimäki I, Kuusio H, Hietapakka L, Lämsä R 2014 Employment, psychosocial work environment and well-being among migrant and native physicians in Finnish health care. European Journal of Public Health 24: 445–451. 3 10.1093/eurpub/cku021

- Altun M 2015 The Role of working abroad as a teacher on professional development. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 4: 101–109. 4 10.6007/IJARPED/v4-i4/1937

- Bhugra D 2004 Migration, distress and cultural identity. British Medical Bulletin 69: 129–141. 1 10.1093/bmb/ldh007

- Biemans H, Nieuwenhuis L, Poell R, Mulder M, Wesselink R 2004 Competence-based VET in the Netherlands: Background and pitfalls. Journal of Vocational Education and Training 56: 523–538. 4 10.1080/13636820400200268

- Billett S, Choy S 2013 Learning through work: Emerging perspectives and new challenges. Journal of Workplace Learning 25: 264–276. 4 10.1108/13665621311316447

- Birenbaum M 2003 New insights into learning and teaching and their implications for assessment. In: Segers M, Dochy F, Cascallar E (Eds) Optimizing New Modes of Assessment: In Search of Qualities and Standards, pp. 13–36. Switzerland, Springer Nature.

- Bondevik GT, Holst L, Haugland M, Baerheim A, Raaheim A 2015 Interprofessional workplace learning in primary care: Students from different health professions work in teams in real-life settings. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 27: 175–182.

- Cacciattolo K 2015 Defining workplace learning. European Scientific Journal 1: 243–250.

- Cairns L, Malloch M 2011 Theories of work, place and learning: New directions. In: Malloch M, Cairns L, Evans K, O’Connor BN (Eds). The Sage Handbook of Workplace Learning, pp. 3–16. London, UK: Sage.

- Cervantes RC, Fisher DG, Padilla AM, Napper LE 2016 The Hispanic Stress Inventory Version 2: Improving the assessment of acculturation stress. Psychological Assessment 28: 509–522. 5 10.1037/pas0000200

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD 2018 Research Design (5th ed). London, UK: Sage.

- Doki S, Sasahara S, Matsuzaki I 2018 Stress of working abroad: A systematic review. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 91: 767–784. 7 10.1007/s00420-018-1333-4

- Engeström Y 2011 Activity, theory and learning at work. In: Malloch M, Cairns L, Evans K, O’Connor BN (Eds) The Sage Handbook of Workplace Learning, pp. 86–104. London, UK: Sage.

- Harden R 2001 AMEE Guide No. 21: Curriculum mapping: A tool for transparent and authentic teaching and learning. Medical Teacher 23: 123–137. 2 10.1080/01421590120036547

- Haugland M, Sørsdahl AB, Salam Salih A, Salih O 2014 Factors for success in collaboration between high- and low-income countries: Developing a physiotherapy education programme in Sudan. European Journal of Physiotherapy 16: 130–138. 3 10.3109/21679169.2014.913316

- Illeris K 2004 A model for learning in working life. Journal of Workplace Learning 16: 431–441. 8 10.1108/13665620410566405

- Illeris K 2018 A comprehensive understanding of human learning. In: Illeris K (Ed) Contemporary Theories of Learning. Learning Theorists … In Their Own Words (2nd ed), pp. 8–22. New York, US: Routledge.

- Jentsch B, Pilley C 2003 Research relationships between the South and the North: Cinderella and the ugly sisters? Social Science & Medicine 57: 1957–1967. 2003 10 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00060-1

- John EB, Pfalzer LA, Fapta DF, Glickman L, Masaaki S, Sabus C 2012 Establishing and upgrading physical therapist education in developing countries: Four case examples of service by Japan and United States physical therapist programs to Nigeria, Suriname, Mongolia, and Jordan. Journal of Physical Therapy Education 26: 29–39. 1 10.1097/00001416-201210000-00007

- Lave J, Wenger E 1991 Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- LaVerle BB 2015 A Country Study: Sudan. Washington DC, USA: Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/cs/pdf/CS_Sudan.pdf.

- Malterud K 2011 Kvalitative Metoder i Medisinsk Forskning. En Innføring, [Qualitative Methods in Medical Research: An Introduction (3rd ed)]. Oslo, NW: Universitetsforlaget.

- Malterud K 2012 Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 40: 795–805. 8 10.1177/1403494812465030

- Méda D 2016 The Future of Work: The Meaning and Value of Work in Europe. International Labour Office Research Paper No.18. https://www.ilo.org/global/research/publications/papers/WCMS_532405/lang–en/index.htm.

- Mulder M, Gulikers J 2011 Workplace learning in East Africa: A case study. In: Malloch M, Cairns L, Evans K, O’Connor BN (Eds) The Sage Handbook of Workplace Learning, pp. 307–318. London, UK: Sage.

- Olsen DS, Tikkanen T 2018 The developing field of workplace learning and the contribution of PIAAC. International Journal of Lifelong Education 37: 546–559. 5 10.1080/02601370.2018.1497720

- Patton MQ 2015 Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods (4th). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Patton N, Higgs J, Smith M 2013 Using theories of learning in workplaces to enhance physiotherapy clinical education. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 29: 493–503. 7 10.3109/09593985.2012.753651

- Rodríguez E 2011 Reflections from an international immersion trip: New possibilities to institution-alize curriculum. Teacher Education Quarterly 38: 147–160.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL 2000 Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology 25: 54–67. 1 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

- Sfard A 1998 On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one. Educational Researcher 27: 4–13. 2 10.3102/0013189X027002004

- Tomasello M 2004 Learning through others. Daedalus 133: 51–58. 1 10.1162/001152604772746693

- Vågstøl U, Skøien AK 2011 A learning climate for discovery and awareness: Physiotherapy students’ perspective on learning and supervision in practice. Advances in Physiotherapy 13: 71–78. 2 10.3109/14038196.2011.565797

- Zhou Y, Jindal-Snape D, Topping K, Todman J 2008 Theoretical models of culture shock and adaptation in international students in higher education. Studies in Higher Education 33: 63–75. 1 10.1080/03075070701794833