?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The present article is primarily intended as a methodological contribution to Islamic Studies providing an example of how the power of computer-aided text analysis can benefit the field. The data consists of a set of 51 lexicons created out of translations of the Qur’an into English. The analysis applies simple programming to calculate the lexical overlap between translations and uses the results in a preliminary discussion of possible influence of earlier on later translations. The results are compared with conclusions arrived at in previous research on the interrelationship between translations and are also used to identify and suggest new areas for in-depth studies.

Introduction

Muslims often claim that ‘the Qur’an cannot be translated’, echoing the dogma of the ‘inimitability’, iʿjāz, of the Qur’an. Nevertheless, throughout Islamic history, and in particular during the last century, the text of the Qur’an has been translated into a variety of languages other than the original Arabic.Footnote1 Such translations have been produced by both non-Muslims and Muslims. Some have been made by movements or organizations as part of missionary activities. Others are the works of independent religious scholars, linguists or just devout individuals without any formal religious training. Some have been printed by acknowledged publishers. Others are self-published works, and a few are only available in digital form on-line.

The strong claim of untranslatability may be one reason why translations, as data in themselves, have received little attention in the field of Islamic Studies, at least when compared with the source text. This article is in part a contribution to the study of Qur’an translations as important in their own right, not least as sources for the study of religious change. Mainly, however, the article is intended as a contribution in terms of methodology.

The article relates a set of 51 English translations to one another, creating a crude, and highly preliminary, chronologically arranged network based on lexical (word stock) overlaps.

As far as the present author is aware, this has not previously been done, at least not on a large scale. One of the reasons for this may be that the operation, if done manually, would be highly time consuming. Assuming an average reading pace of 200 words per minute, it would take one person 16 weeks of full-time working hours, five days a week, just to read through the texts that constitute the raw data for this article. To compare word use in the translations, by means of making lists of and analysing lexical overlaps, would take considerably longer, not to mention having potentially damaging effects on the researcher’s mental health.

I have not done this. I have instead relied on the ability of computers to outperform humans in precisely these areas (counting and comparing). Constructing the tools, in terms of small computer programs, to prepare and analyse texts, was until recently a competence reserved for specialists. Today, it is increasingly becoming accessible to non-specialists too. The threshold has been considerably lowered. All the computer programs, or scripts, used in this article have been constructed by the author and are written in the Python programming language.

A note on previous research

Regardless of whether or not the message of the Qur’an loses its meaning when translated into other languages than Arabic, it is reasonable to assume that translations, and not least translations into English, have been important in the development of Islam as a religious tradition, especially during the last century.

Literacy among believing Muslims around the world has risen and, for the most part, this has not been literacy in the classical Arabic of the Qur’an. Given the fact that the mother tongue of the vast majority of Muslims in the world today is not Arabic, it is reasonable to suggest that the majority of those who read the Qur’an in search of meaningful religious information do it in a language other than Arabic. English is the most transnational language in this context, having a growing importance as a global lingua franca of Islam (Wild Citation2015).

Still, as noted above, the academic study of English translations of the Qur’an is not extensive. One of the latest contributions, and the one with the hitherto widest scope as an overview, is religious studies scholar Bruce Lawrence’s book The Koran in English (Citation2017). This ambitious book covers a wide selection of translations made by both non-Muslims and Muslims from the seventeenth century up till 2017. It provides biographical information on some of the better-known translators and compares different translations of a few selected verses. It also notes the expanding presence of translations on-line, and provides an important, and highly useful, list of available translations. Lawrence cites 108 complete works, the vast majority of them being translations made by Muslims. This appears to be a near comprehensive list. I have only been able to gather information on a few additional works. As Lawrence notes, the growth in the number of translations over time has been exponential. Almost half of the translations on his list have been published since the turn of the new millennium.

Lawrence’s book contains approaches that are found separately in other works. There are, for example, case studies that provide both biographical information on individual translators and assessments of the translations that they have produced, as well as the contexts of their production (Khan Citation1986; Mohammed Citation2005; Wild Citation2015; Greifenhagen Citation1992). One of the more ambitious examples in this category is English language scholar Abdur Raheem Kidwai’s Translating the Untranslatable (Citation2011). This book covers 60 translations of the Qur’an, with references to a number of editions and published reviews. While providing some valuable information, the book is unfortunately tainted by a strong Sunni and literalist bias.Footnote2

Other studies provide more detailed comparisons between different translations, of their general style and word use, or of how a particular verse or theme, e.g. gender, is addressed (see e.g. Al-Saggaf, Yasin, and Abdullah Citation2013; Hassen Citation2011). A particular category in previous research compares how particular features of the source language (Arabic) have been rendered into English in different translations (see e.g. Al-Ghazalli Citation2012; Al Ghamdi Citation2015). Yet another category of previous research contains works that address issues on how translations can be said to mirror the translator’s character, or his or her sectarian or ideological biases (see e.g. Sideeg Citation2015; Robinson Citation1997; al-Amri Citation2010).

There are several important respects in which the present article differs from previous research. Most importantly, it refrains from evaluating the various translations, either aesthetically or ideologically. Highly acclaimed translations by trained linguists are treated equally with self-published works by non-academics, however odd and idiosyncratic in character the individual work may be. The study does not focus on differences between translations but instead on similarities, and it is the relations between the texts, rather than the individual texts themselves that are in focus. With a few exceptions, the ideological leanings, personal character, gender or intentions of the individual translators, and how such factors may have influenced their translations are also set aside.

Perhaps most importantly, this is not a study in the field of translation studies in the sense that it dwells upon the relationship between a ‘source text’ being translated into a ‘target text’, and the diverse problems involved in that process. The ultimate source text, i.e. the Arabic text of the Qur’an, is of no importance to the study. In fact, a few of the translations in the set are not translations of the original Arabic, but of translations into Urdu and in one case of a paraphrase into modern standard Arabic.

As far as I know, there is not much in terms previous research that investigates the lexical overlaps of translations, using the lexicons of diverse translations as data in search of interconnectedness. The closest equivalent that I have been able to find is a published conference paper from 2013 (Murah Citation2013). Here, the author presents the results from a comparative study of seven translations into English. There is, however, no chronological ordering or any suggestion of relations between translations, although the study in question does employ computer-aided text analysis. This is not unique in contemporary Qur’anic Studies, albeit not commonplace. However, most existing computer-aided studies of the Qur’an focus on the Arabic original, not on translations (for examples of such works, see Safeena and Kammani Citation2013) and several are of an explicitly confessional character, attempting to scientifically ‘prove’, with the help of computers, the unique, or even miraculous character of ‘the word of God’. One of the better-known examples of this latter tendency, associated with the Qur’an translator Rashad Khalifa, will be addressed below.

It should be stressed that my expertise lies not in the field of computer-assisted text analysis, but in the field of comparative Islamic Studies. The current article does not aim therefore at presenting anything new, or of value, to the former, but it does aim to contribute something to a burgeoning trend of Digital Humanities research in the field of Islamic Studies (Muhanna Citation2016). One of the main tasks within this is to frame relevant questions within Islamic Studies in a manner that can utilize ways of working with religious source material that new technology offers.

The problem in detail

If someone decides to translate the Qur’an, or any text, it is conceivable that she or he will glance at already available translations for inspiration, and perhaps help with particularly cumbersome phrases and words. Lawrence claims that all English translations of the Qur’an are in one way or another ‘parasitic’ on earlier translations (Lawrence Citation2017, 48). Even if a translator does not borrow phrases or words from earlier translations, she or he is, in the very act of translating, parasitic on an established practice. The parasitic character of translations is a matter of degree, from outright plagiarism to inspiration to carry out the act of translation in the first place.

I here focus on the more direct form of parasitic translations, posing the question of how one can find out if a later translation has been inspired by, or has borrowed from, an earlier one. In some cases, the translator may provide this information, stating sources of inspiration. In other cases, however, such information may be lacking. We could, of course, perform guess work based on what previous translations may have been available to the translator in question.

This article rests on the following assumption: If a translation B has a portion of its words in common with an earlier translation A that significantly exceeds what could be expected, given that they are both translations of the same source text, then this is an indication (but far from proof) that B may have been inspired or influenced by A. The method then, is to compare the lexicons of A and B and search for such significant overlaps. In what follows, such overlaps will be termed ‘connections’ and will be treated merely as possible signs of influence.

To carry out this comparison manually is tedious work. It would involve first making a list of the words in B, and then searching for the occurrence of these words in A. Whether or not the number of overlaps between the two deviates positively from what could be expected would furthermore require comparison with a mean arrived at by looking for overlaps within a larger set of translations. A solution to the problem could be to use a limited sample from the texts of each of the translations in question. This would, however, as is the case with all sampling, bring more uncertainty into the operation. The use of computers and simple programming makes it possible to use the entire lexicons of the translations, and still complete the task in a fraction of the time that a manual investigation of even a very limited sample would require.

Material

In the following, I use as data collections of the words (lexicons) contained in 51 different English translations of the Qur’an – a number that is slightly less than half of the total number of English translations available (see above). The choice is one based on expediency. The lexicons were created (with a few exceptions) from translations available in digital form on the website islamawakened.com, which Lawrence (Citation2017, 93) claims ‘exceeds all other competitive websites on Koran translations’.

Of the 50 translations present on islamawakened.com at the time when the lexicons were created, two pairs are versions of one another. One pair consisted of perhaps the best-known translation, by Yusuf Ali. One version is dated 1938 (on the website) and the second version is a Saudi Arabian sponsored revised edition dated 1985. The second pair consist of two editions (published in 2011 and 2013, according to islamawakened) of a translation that is a collective work by the so called ‘Monotheist Group’. The reason for including all four in the material, apart from the fact that they were available, will become evident below.

From the translations available on islamawakened.com I created 50 lexicons that were saved locally as separate text files, using the word tokenizer included in the Python library Textblob. This was done on 17 December 2017. On closer inspection, it turned out that two of the translations on the islamawakened homepage were incomplete, so the lexicons of these two were created using two other sites. The lexicon made from the translation of Abu al-Aʿla Mawdudi’s commentary on the Qur’an, published in 2006, was created on 13 January 2018 based on the translation available on the website tanzil.net. A lexicon of Hamid S. Aziz’s translation was created on the same date on the basis of the on-line translation available at qurandatabase.org. On tanzil.net, I also discovered an additional translation, attributed to a Safi al-Rahman Mubarakpuri, from which I created yet another lexicon.

In creating the lexicons, I excluded text contained within brackets. Introducing text in this manner is a commonplace practice in Qur’an translations. For example, Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall’s translation of verse 1:3 (as presented on islamawakened.com) reads ‘Thee (alone) we worship; Thee (alone) we ask for help.’ The word ‘alone’ in is not actually in the Arabic source text. It is an addition that stresses the theological dogma of tawḥīd, or absolute monotheism.

Words placed within brackets in translations may at times serve merely as linguistic clarifications. They may indicate, for example, that a particular word that is necessary for producing a correct sentence in English is lacking, or is only implicit, in the Arabic original. However, translators may also use bracketing when providing cross-references, more detailed interpretations or personal comments. For the purpose of this particular study, I chose not to include in the lexicons any words put between brackets.

The text with the lexicons was then checked for typos and formatting errors with a Python script that compared each lexicon with every other lexicon and returned the words that were unique to each. Obvious typos were corrected, but misspellings were not. It is, however, unclear whether the typos, which were few in number, would have affected the end result.

Some problems need to be highlighted at this stage. I have chosen to trust the websites from which the lexicons of the translations were created, in the sense that I assume that the on-line texts correspond to the original translations and have not been amended. I have no reason to suspect otherwise, but it is nevertheless a possibility.

A second problem concerns dating. This is of course important, given that interpreting word stock overlaps as influence is dependent upon correct dating. Several of the better-known translations have been published in revised editions over a longer period of time. While the dates of origin for the on-line versions present on the websites used were given in the four cases mentioned above, this was not the case for the rest of the translations. In the process of dating the latter, I have chosen to rely on information gained elsewhere regarding the publication date of the first edition. I have hence assumed, until the opposite is shown, that, whatever changes may have been made between the version found on-line and the original, they are so small that they do not substantially affect the overall result. Even though the focus in this article is on the method, and not on any particular results, it should be kept in mind that the latter must be treated as highly tentative and possibly open to change in the future as new information becomes available.

Method

In comparing the lexicons, searching for similarities in translations, I chose an established, yet simple, measure: the Jaccard similarity. Other methods that could have been used as well (for presentations and discussions of a variety of such methods, see e.g. Gomaa and Fahmy Citation2013; Vijaymeena and Kavitha Citation2016), but the Jaccard similarity is easy to comprehend and include in code, even for a non-specialist, and hence chimes well with the purposes of the article.

The lexicons analysed, one for each translation, are treated as ‘bags of words’, i.e. collections of tokens (in this case whole words) without regard to word order or context. These tokens are, in turn, instances of a set of unique types contained in the lexicon.

As an illustration, in the translation of Q 1.3 by Marmaduke Pickthall (d. 1936) (words between brackets removed) may be compared with how the verse is rendered in another well-known translation, that of Yusuf Ali. Both quotations are from islamawakened.com.

Pickthall:

‘Thee we worship; Thee we ask for help’

Tokens: thee we worship thee we ask for help

Types: ask for help thee we worship

Ali:

‘Thee do we worship, and Thine aid we seek’

Tokens: thee do we worship and thine aid we seek

Types: aid and do seek thee thine we worship

To repeat: the basic assumption underlying this study – here A and B are translations (transformed into lexicons) – is that, if the JC of A and B is significantly higher than expected and A precedes B in time, this connection may be an indication of lexical influence.

In the actual process, I constructed a script that computed the JC for each lexicon and all lexicons derived from later translations in turn. This resulted in a total of 1,275 pairs. The program did not include all types. Since all translations are translations (directly or indirectly) of one and the same source text, a high level of words present in all lexicons was to be expected. Indeed, testing for this, it turned out that 873 words were shared by all 51 texts. These included words common in most texts in English (conjunctions, pronouns, etc.) but also other, less common words such as ‘crucified’, ‘prophet’ and ‘wool’. Types common to all lexicons were of little interest in the comparisons, and hence they were removed from all lexicons before calculating the JCs of the 1,275 pairs.

Results

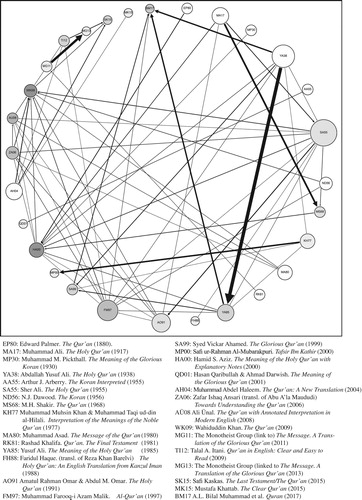

The mean as well as median JC for all pairs was 0,36. As part of analysing connections, I decided to include only the 5% of those with the highest JC in the total set of pairs in a chronologically arranged visualization (see ), which forms the basis for the following analysis. This was done in order not to clutter the resulting graph. The graph has been constructed with the open source visualization software Gephi (available at gephi.org). The 5% correspond to a threshold value of JC of 0,45 (rounded), which excludes 22 of the total 51 translations. These 22 have neither incoming nor outgoing connections with a JC above the threshold value.

The graph runs chronologically clockwise starting at 12 o’clock (with the earliest translation [EP80] being the translation by Edward Palmer, dated 1880). Each circle represents a translation. The thickness of the arrowed lines connecting the circles represents the value of the JC. The size of the circles represents the total density (number of connections as well as their value) of outgoing connections. The gradient of the circle, finally, represents the total density of incoming connections; the darker the gradient, the larger the density.

In the following, I shall use the results from this comparison of translations, mainly those present in the graph, to discuss some conclusions drawn in previous research on relationships between different Qur’an translations, but also to point to some new discoveries worth pursuing in future research. Again, the aim is not to perform a detailed analysis of overlaps and possible relationships, but rather to indicate where such a detailed analysis may be justified.

Observations in relation to previous research

Results supporting previous research

As mentioned above, four of the translations constituted two sets of an original and a revised edition of the same work. This is clearly visible in the graph. The two editions of Yusuf Ali’s translation of the Qur’an (YA38 and YA85) have a JC of 0,99. The two editions of the translation by the so called ‘Monotheist Group’ (MG11 and MG13) have a JC of 0,80. This is of course only to be expected. Even so, the result in the former case may shed some light on a question raised in previous research.

The two editions of Yusuf Ali’s translation have a particular history. The translation is one of the more widely distributed and used. One of the reasons for this is that it was adopted by the Saudi Arabian missionary machinery in the 1980s, revised in 1985 and mass printed by the King Fahd Complex for worldwide distribution. The nature of the revision has been appreciated differently in previous research. According to religious studies scholar Stefan Wild (Citation2015, 172), the Saudi edition was a ‘slightly modified’ version of the original. Lawrence, on the other hand, claims that the latter ‘differs markedly from the original’ (Lawrence Citation2017, 90). Which assertion is correct? The present study indicates that Wild is on the right track. Here, however, it must be remembered that this only applies to the lexical aspect. Furthermore, in-text annotations and footnotes, as well as introductory notes are left out. This suggests that the marked difference that Lawrence refers to may not be in the translated Arabic text as such, but rather in what perhaps could be termed ‘paratextual’ elements in the translation.

It has been claimed by several observers that the 1959 translation by the rather mysterious M.H. Shakir (MS59) relies heavily on one of the earliest Muslim translations, that of Muhammad Ali (MA17), originally published in 1917. Lawrence (Citation2017, 183) views Shakir’s translation an outright forgery ‘reproducing Maulana Muhammad Ali [1917] almost word for word’. Muhammad Ali was one of the founders of the Lahori branch of the Ahmadiyya movement (see below), which officially, on its website, accuses Shakir of forgery and has gone to some length to establish the translator’s true identity.Footnote3 The movement also employed forensic linguist John Olsson to undertake an investigation. His report is published on the movement’s homepage. Olsson’s conclusions are in line with Lawrence’s: ‘The extent to which MH Shakir has plagiarised from MM Ali […], is both breathtaking and blatant. No other conclusion is possible’ (Olsson n.d.). As can be seen from the graph, the current study lends support to the claims made by Lawrence, the Lahori branch of the Ahmadiyya movement and Olsson. The JC of Ali’s and Shakir’s translations is high (0,70), the highest for any pair, excluding the two-version pairs mentioned above. It is noteworthy that neither Kidwai, in his overview of Qur’an translations into English, nor Robinson in his overview of ‘sectarian translations’ mentions these allegations, but they focus instead on Shakir’s Shiite bias (Kidwai Citation2011, 169–172; Robinson Citation1997, 261–263). This may indicate that the allegations, despite the efforts of the Lahori Ahmadis, are not generally known.

There are several other examples of claims on ‘parasitic’ relationships, or similarities, in previous research that are supported in the current study. Lawrence (Citation2017, 184), for example, claims that the translation by Syed Vickar Ahamed (SA99) is ‘mostly derived, without acknowledgement, from Yusuf Ali’. Kidwai (Citation2011, 134) is harsher, calling the translation ‘another blatant instance of plagiarism in the noble field of Qur’anic studies’. Lawrence’s and Kidwai’s assessments are somewhat confirmed. The pairs YA38-SA99 and YA85-SA99 both have a JC of 0,52.

In the conference paper mentioned above, Mohd Zamri Murah (Citation2013) presents results from a computer-aided analysis of similarities between seven Qur’an translations, using several methods, among them a ‘bag of words’ method similar to the one used here. One translation pair stands out: that of Yusuf Ali and that of Muhammad Muhsin Khan and Muhammad Taqi ud-Din al-Hilali (originally published in 1977). When a Saudi Arabian project to mass produce and mass distribute English translations of the Qur’an was initiated, the choice of which translation to use fell on Yusuf Ali’s, despite some reservations regarding the translator’s theological orientation. Around 1989/1990, according to Wild (Citation2015, 173), there was a shift from Yusuf Ali’s translation, to that of Khan and al-Hilali, the latter taking over the officially sanctioned position of the former. The findings here indicate possible continuation, however. Murah’s results are to some extent confirmed. There is a connection between Yusuf Ali’s translation and the translation by Khan and al-Hilali (KH77), with a JC of 0,45.

In referring to the translation by Hamid S. Aziz (HA00), Lawrence (Citation2017, 184) quotes the translator’s words that it is ‘not an original direct translation from the Arabic but the result of comparing several other English translations’. In other words, it could be characterized as a ‘translation sampling’. Looking more closely at the connections between this particular translation and possible predecessors does indeed show a high level of incoming connections above the set threshold (indicated by the dark gradient).

Results questioning or qualifying previous research

While the current study thus appears to lend support to some observations and claims in previous research, this is not always the case. Religious Studies scholar Khaleel Mohammed (Citation2005, 4) has claimed that Pickthall’s translation from 1930 was heavily influenced by Muhammad Ali’s. Mohammed does not provide any reference to support this assertion, but Islamic Studies scholar Neal Robinson (Citation1997, 269), making a similar claim, refers to a study published in 1931, where samples of verses from the two translations are compared and found to be similar. In the study, Pickthall’s translation is also compared with previous translations by non-Muslims, and similarities are found, particularly with the translation by John Medows Rodwell (Shellabear Citation1931). Neither claim is clearly supported by the present study. The JC of the translation pair Muhammad Ali–Pickthall is 0,39, and for the pair Rodwell–Pickthall the JC is 0,40. Both JCs are hence above average, but neither makes it above the set threshold.

It can be noted, however, that, unlike Pickthall’s translation, Yusuf Ali’s translation, which, in its first edition (1934) is almost contemporary with Pickthall’s, does display a higher JC in relation to Muhammad Ali’s translation (0,42), although it does not make it above the set threshold.

So, while it may be the case, as Lawrence (Citation2017, 64–65) claims, that both Pickthall and Yusuf Ali are indebted to Muhammad Ali in the sense that Muhammad Ali paved the way for translations into English, and set some standards, there are indications of a difference between the two in terms of possible lexical influence. This would also correspond well with what is otherwise known particularly about Pickthall and how he conceived of his own translation: as a correction of perceived deficiencies in previous translations, including Muhammad Ali’s (see e.g. Lawrence Citation2017, 58; Kidwai Citation2017, 232).

Another example where the current study leads to the questioning or qualification of claims in previous research concerns the controversial translation by Laleh Bakhtiar, one of comparatively few female translators. Her translation was heavily criticized when it first appeared, partly because it was a conscious attempt at producing a ‘modernist’ translation, particularly pertaining to gender, and partly because she lacked knowledge in Arabic (see e.g. al-al-Amri Citation2010, 105–196; Scrivener Citation2007). In his assessment of Bakhtiar’s translation, Lawrence (Citation2017, 100) claims that she is ‘often […] imitating the style, or even the wording, of A.J. Arberry’. According to the appended footnote, Lawrence here relies on Kidwai (Citation2011, 144–148), who is very harsh in his negative judgement. It is unclear how Kidwai in turn arrived at this conclusion. The JC between Arberry’s and Bakhtiar’s translations is indeed well above the average (0,41), but below the set threshold. More importantly, Bakhtiar’s translation does not stand out as particularly strongly connected to any previous tradition compared with other recent translations that both Lawrence and Kidwai discuss without any note on possible dependence, and review positively, such as, for example, the translations by Muhammad Abdel Haleem and Wahiduddin Khan (Lawrence Citation2017, 86; Kidwai Citation2011, 131–135, 160–161). Both these translations have, according to the analysis in the present study, incoming connections with higher JC than the connection between Arberry and Bakhtiar. Abdel Haleem’s translation has eight inbound connections with a JC exceeding 0,41, although none makes it above the set threshold of JC 0,45. In the case of Wahiduddin Khan’s translation, the corresponding number is 18, of which nine are above the threshold, as can be seen in (WK09).

New discoveries

Strong connections not noted in previous research

As outlined above, Lawrence has noted the strong connection between the translation pair Yusuf Ali–Syed Vickar Ahamed indicated by a JC of 0,52. However, there are other pairs, not mentioned in previous research, that display an even higher JC. One is the Yusuf Ali (both versions)–Bilal Muhammad et al. (BM17) pair, with a JC of 0,62 (the fifth and sixth highest JC). The link provided by islamawakened.com leads to an Amazon page with the Kindle edition of the translation, with the title Quran: Translations Compiled by Members of the Imam W.D. Mohammed Community. The presentation of the book given here states that it is ‘based on classic works by A. Yusef [sic!] Ali, Imam W. Deen Mohammed, Muhammad Asad, and M.M. Pickthall. Other verses are based on new interpretations found on sites like islamawakened.com. And still others are based on selected entries we receive from around the world by devoted students of the Quran’ (Amazon.com Citation2018c) The present results would indicate that the most important of the translations mentioned is that of Yusuf Ali, which would be in line with information given in relation to an earlier publication attributed to Bilal Muhammad, a self-published work available as print-on-demand from amazon.com. The short description of this work cites Yusuf Ali’s translation as the main source of inspiration (Amazon.com Citation2018b).

A connection with an even higher JC (0,65), the fourth highest in the sample, occurs between Khan and al-Hilali and the translation attributed to one Safi al-Rahman Mubarakpuri (MP00). Some further investigation reveals that Mubarakpuri is actually not the name of a translator. He was the supervisor of a translation of the tafsīr (Qur’an commentary) by Ibn Kathīr (d. 1373). The translation was originally published in 2000, according to information on WorldCat (Citation2018). In 2013, it was released as an app, and it was included in the collection of translations at tanzil.net in 2015. The book contains a translation of the qur’anic text, and that translation is in turn based on the translation of Khan and al-Hilali (Amazon.com Citation2018a).

Translation sampling

Above, it was noted that the level of incoming connections (9) above the set threshold to Hamid al-Aziz’s translation could indicate a process of ‘translation sampling’, i.e. using multiple translations as sources for inspiration. Other translations in the set under investigation here display a similar pattern. As mentioned above, Wahiduddin Khan’s (WK09) translation also has nine incoming connections above the set threshold. The translation by Ali Ünal (AU07) has six, and the 2006 Qur’an translation from the Urdu translation of Mawdudi’s tafsīr (ZA06) has a total of five incoming connections with a JC above the threshold. These examples, which are comparatively recent, may reflect a situation of availability of previous translations in a format that is ‘copy-paste’ friendly. However, further research as to the nature of the overlaps is needed in order to investigate this. As will be discussed in the conclusion, there is another possible, and perhaps more intriguing, explanation.

Ideological clusters

One of the more interesting results, in my view, relates to the three translations associated with the already mentioned controversial Ahmadiyya movement. Since its emergence in the late nineteenth century, its followers have been accused of heresy because of its founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmed’s claim to be the awaited Messias (masīḥ) but also to prophethood, and consequently his denial of the dogma that Muhammad was the last prophet. While the two branches of the movement, the Lahori and Qadiani, differ in their views on how radical this latter claim really was, both are generally viewed with suspicion, even hatred, by other Muslims.Footnote4 Nevertheless, the movement’s two branches have been highly active in its missionary work, not least, and most importantly for the present study, by providing translations of the Qur’an in diverse languages (Friedmann Citation2007; Jonker Citation2015).

In the graph (), an Ahmadiyya network of translations is visible through the interconnectedness between Muhammad Ali’s translation and the later two Ahmadiyya translations included in the sample, those by Sher Ali (SA55) and by Amatul Rahman Omar and Abdul Mannan Omar (AO91). The JCs between the translation pairs are: Muhammad Ali–Sher Ali 0,52; Muhammad Ali–Omar and Omar 0,45; and Sher Ali–Omar and Omar 0,54 (the seventh highest in the set). This was perhaps to be expected, but to my knowledge, relationships between these three translations have not been noted in previous research. As will be further discussed below, the Ahmadiyya part in the overall history of translations of the Qur’an into English is well worth pursuing in future research.

As can be noted in the graph, there is a connection above the set threshold (JC = 0,46) between the translation by Rashid Khalifa (RK81) and the first edition of the translation by the above-mentioned Monotheist Group (MG11). The biochemist Khalifa, who was murdered in Tuscon Arizona in 1990, was a controversial translator. In the process of computerizing the text of the Qur’an, he found not only that the number 19 was coded into it (admittedly only after removing two verses [Q 9.128–129]) (Khalifa Citation1981, 443–465), but also that the text foretold himself, Rashad Khalifa, through mathematical code, as ‘God’s Messenger of the Covenant’. This elevated position had, according to Khalifa, been confirmed by revelations from the Archangel Gabriel, and in a dream where it was acknowledged by a row of previous prophets (405–407) Today, Khalifa’s legacy is upheld by the missionary group who call themselves ‘Submitters’ and who continue to spread his message of the miracle of 19 and distribute his writings, including his translation of the Qur’an (Submitters Citation2018).

No connection between Khalifa’s translation and the translation by the ‘Monotheist Group’ is indicated on islamawakened, from which the lexicons were created – rather the opposite. Here, the two translations by the ‘Monotheist Group’ are placed in the category of ‘Generally Accepted Translations’, while Khalifa’s translation is placed among ‘Controversial, deprecated, or status undetermined works’ [uppercase and lowercase as in the original]. Khalifa’s translation is mentioned by both Lawrence and Kidwai, and heavily criticized by the latter (Kidwai Citation2011, 285–288). Neither of them mention the ‘Monotheist Group’ in their lists of translations. However, Lawrence titles the 2012 translation by Edip Yuksel, Layth Saleh al-Shaiban and Martha Shulte Nafeh The Qur’an: A Monotheist Translation and claims that it is a reprint of an earlier, anonymous, work, The Qur’an: A Pure and Literal Translation, published in 2008 (Lawrence Citation2017, 187). On amazon.com and other booksellers on-line, the translators of two works with exactly these titles are not identified as Yuksel et al., but as ‘The Monotheist Group’. On the other hand, a translation with the title The Qur’an – a Reformist Translation (2007) available from Amazon in a 2012 edition, has Yuksel et al. as translators. Kidwai (Citation2011, 295–300) mentions – and criticizes – this translation and notes that it is in line with the thoughts of Khalifa, especially concerning the number 19. No mention is here made of any ‘Monotheist Group’.

In an article from 2010, Islamic Studies scholar Aisha Musa points out that Khalifa and Yuksel were personal friends and associates, and also representatives of a larger trend of ‘quranists’, who reject the authority of other religious sources than the Qur’an (i.e. mainly the Hadith). Musa (Citation2010, 19) also mentions the home page free-minds.com as a third representative of the qur’anist trend, a homepage also noted by Lawrence (Citation2017, 89–90, 187) in his comment on Yuksel et al.’s translation. On this homepage, not only are links provided to Yuksel et al.’s translation, and other works by Yuksel, but available for direct download are also two more Qur’an translations, titled The Message: A Translation of the Glorious Qur’an and The Great Qur’an: An English Translation, both published by Brainbow Press in 2018. They turn out to be identical (apart from the title), and both are attributed to ‘The Monotheist Group’.Footnote5 Hence, again, the crude method for comparing translations employed in this article appears to be able to indicate relationships that could be the objects for further investigation.

Influential translations

If Islamic Studies scholars were asked which translation of the Qur’an has been the most influential, many would probably opt for Yusuf Ali’s. In the current study, Yusuf Ali’s translation, with a publication date given as 1938 for the on-line version used here, does display a large number of outgoing connections above the set threshold. Excluding the natural one with the 1985 version, there are six such connections.

In the scholarly literature, certain other translations by Muslims often receive especial attention as classics, particularly Pickthall’s translation and the 1980 translation by Muhammad Asad. Lawrence (Citation2017, 80) places these three, together with Muhammad Ali’s 1917 translation, in a set of works that, in his words ‘have set the standard for all subsequent translations’. Lexically speaking, however, there appear to be differences. Muhammad Ali’s translation does not match Yusuf Ali in the number of outgoing connections. It has four in all, of which one is the above-mentioned case of plagiarism. Pickthall’s translation has only one outgoing connection, to the ‘sampled’ translation of Hamid S. Aziz.Footnote6 Asad’s translation (MA80) has three outgoing connections, all likewise to translations that have been identified as possible ‘samplers’.

In addition, if the density of outgoing connections with a JC above the threshold is any indication of importance or influence in relation to later translations, Yusuf Ali’s translation does not take the lead. That position is taken by the Ahmadiyya translation of Sher Ali, with nine outgoing connections with a JC above the set threshold, although two of these connections are unlikely to indicate any influence. The connection to the 1985 Yusuf Ali translation mirrors a connection to the earlier 1938 Yusuf Ali translation and the connection to Shakir’s translation could be assumed to mirror the strong connection between Shakir and Muhammad Ali. Still, the remaining seven connections are noteworthy. The Ahmadiyya may be a marginal movement within Islam, but in the history of translations of the Qur’an into English, and perhaps also other languages, they may very well prove to be more important that is usually acknowledged. The first ever English translation by a Muslim, The Holy Korán (not presently included in the material), published in 1905, was made by a member of the movement, Mohammad Abdul Hakim Khan. So was the first Muslim translation to gain a wider circulation internationally (Muhammad Ali’s Citation1917 translation) (al-Amri Citation2010, 90–91).Footnote7 To this may then be added, perhaps, the translation by Sher Ali having lexical influence even on non-Ahmadiyya translations. In his article on translations of the Qur’an in the Encyclopedia of the Qur’an, Harmut Bobzin (Citation2001) rightly notes that Ahmadiyya translations of the Qur’an is an area where more research is needed.

Judging merely from the number of outgoing connections in the network, there are two more translations worth mentioning.

The 1997 translation by Farooq-i Azam Malik (FM97) has six outgoing connections to later translations. This may appear surprising. Malik’s translation is not one that is usually mentioned as one of the more important in previous research. Here, a limitation of the method applied, and the need for more fine-grained analysis, becomes obvious. Sher Ali’s and Malik’s translations have a connection between them. In addition, they share four connections with later translations (HA00, ZA06, AÜ07, WK09), which in turn also have connections between them, with a JC above the set threshold. The problem is that, if these connections are the result of later translators borrowing from earlier translators, it is impossible from the method employed to determine which earlier translation constitutes the source. Does the connection between the translations by Ali Ünal (AÜ07) and Sher Ali indicate that the former has been lexically influenced by the latter, or by any of the other preceding translations that also display connections with Sher Ali’s translation? As can be seen in the graph (), there are several such clusters of interconnections between sets of translations calling for further analysis where not only the level of lexical overlap, but also the nature of the overlaps should be in focus. If such an analysis should show independent strong connections between Malik’s translation and later ones, this might be explained by the fact that the translation was one of four included in later versions of the popular and widely spread (and widely pirated) software Alim distributed on CD-ROM (now transformed into a web page: alim.org), and hence an easily accessible resource for copy-pasting.

The second translation worth mentioning in this context is the one by Muhammad Abdel Haleem (AH04). Although it is fairly recent, it has comparably many outgoing connections (4) to later translations that reach above the set threshold, while no incoming ones (although, as mentioned above, it does have quite a few well above the overall mean). In a comment on this translation, which has been published by Oxford University Press, Lawrence (Citation2017, 86) notes that it is ‘far and away the best seller in English’. He also states that it is the most frequently accessed translation on the web resource Oxford Islamic Studies Online (130).

Connections between Muslim and non-Muslim translations

The sample contains five translations by non-Muslims. Three of these (by George Sale, Edward Henry Palmer and John Medows Rodwell) were published prior to the first known Muslim translation. Included are also two of the better-known non-Muslim translations available, both widespread: those by Arthur J. Arberry and N.J. Dawood.

In general, connections between early non-Muslim translations and later translations are weak. The mean JC of both Sale’s and Rodwell’s translations and all later translations in the sample is 0,32. The mean for Palmer’s translation is higher (0,34) but still below the overall mean (0,36) As can be seen in the graph, it is also only Palmer’s (EP80) translation that has a connection to a later translation at a level higher than the set threshold, that is to the translation by the now already twice mentioned possible sampler Hamid Aziz.

The weakness of connections to early non-Muslim translations is in line with what has been noted in previous research, i.e. that Muslims, and early Muslim translators, have, perhaps rightly, looked upon these translations with suspicion, as parts of a larger hostile, missionary project (Wild Citation2015, 163–164, 168).

Among the earliest Muslim translations included in the sample, those by Muhammad Ali, Pickthall and Yusuf Ali, there is only one connection to non-Muslim predecessors that stands out, even if it does not make it above the set threshold: that between Muhammad Ali’s and Palmer’s translations (JC = 0,42). Although this study does not address the paratexts (introductions, etc.) in the various translations, I could not resist the temptation to have a glance at what Muhammad Ali writes about Sale, Rodwell and Palmer. As Greifenhagen (Citation1992, 284) correctly notes, they are all referred to (mainly in negative terms) in the introduction to the 1917 translation, and also in the footnotes that accompany the translation proper. In a passing note, however, Ali writes: ‘I have tried to be more faithful to the words of the Holy Writ than all existing translations in the English language, among which Palmer has remained nearest to the words’ (Ali Citation1917, xcii).

Neither of the two later non-Muslim translations included in the sample have incoming connections that reach above the threshold, but both have a few outgoing connections to later translations, which then could indicate a somewhat less negative attitude towards these latter examples of ‘Orientalist’ scholarship. Arberry’s (AA55) translation has a connection with Hassan Qaribullah’s translation, with a JC of 0,47. In the case of Dawood’s translation (ND56), there are two outbound connections that make it above the threshold. In sum, though, nothing in this study indicates that there has been any particularly noteworthy influence on the lexical level from any of the translations by non-Muslims on translations by Muslims.

Discussion

Above, I have attempted to show how a relatively simple computer-aided analysis of lexical interconnectedness between Qur’an translations that would be, if not impossible, at least highly time consuming to do manually, can generate results that lend support to claims in previous research, qualify or question other such claims, and point out themes and patterns that can be pursued in future research. In this conclusion, I will not iterate what has already been noted, but rather highlight some of the weaknesses of the study and provide some additional suggestions as for further research.

Again, the Jaccard similarity measure used in this article is admittedly crude. There are several more sophisticated, and more complex, ways of measuring similarity between texts that may be applied to sets of Qur’an translations. One topic for further research would be to investigate whether different methods render the same, or similar, results as the present study. Such a study would, however, require more specialized skills in the field of computer aided Natural Language Processing than the present author possesses at the time of writing.

The lexicons used are almost all created from the same source and the study relies on that source being trustworthy in its reproduction of the translations. Correct dating of the texts from which the lexicons are created, which is necessary for assessing possible influence, is not guaranteed. Still, these problems are minor, given the fact that the main focus in the article is not the actual results (which are all tentative) but the tool proposed. The lexicons can easily be updated (or excluded from the set) if it turns out that they have been based on defective texts, or arranged differently if dating turns out to be incorrect. The tool also allows for easy inclusion of new lexicons.

As noted, the results arrived at here must be seen as tentative, as a first indication of avenues worth pursuing in future research on the interdependence of, and possible influence between, Qur’an translations. The next step in this process could be to perform more detailed analyses. Several topics for further investigation been noted above. Here are a couple more.

The analysis has been on the level of lexical similarity, with no consideration as to where in the texts similarities appear. Hence, more fine-grained analysis can be made on the level of phrases, sentences or verses in those cases where the present study indicates a higher-that-expected level of similarity between translations. If there is actual ‘borrowing’ between an earlier and a later translation, what is the character of that borrowing? Is the similarity a matter of later translators using the earlier translator’s choice of translations of individual words or shorter, standardized phrases in Arabic, or is it a matter of ‘copy-pasting’ whole passages, i.e. outright plagiarism?

Another topic worth pursuing is whether, over time, a more or less standardized English-Qur’anic lexicon has developed, i.e. if certain translations of words and phrases, introduced by some translator at a particular moment in time, has gained such prominence that it has become the standard way of rendering particular Arabic-qur’anic words and phrases into English, part of a common more or less agreed upon lexicon. From the graph, there are also indications of a higher density of interconnectedness over time between translations that are close to one another in time. This could perhaps be an indication of a process of lexical standardization, rather than a direct ‘parasitic’ behaviour of the individual translator in relation to specific previous translations.

These are but a few possible avenues that can be pursued in future research with the help of simple, yet powerful, methods of computer-aided text analysis. The underlying questions are genuinely humanistic in character: questions of how cultural (and more narrowly religious) change and continuity is mirrored in language use. Computer-aided textual analysis can assist in both supporting and questioning claims of such change with a firm foundation in the available data, in a way that would be difficult, if not impossible, to do with traditional methods, at least with the same level of accuracy. Computer-aided text analysis can also be a powerful tool for testing hunches, and for discovering new and unexpected patterns. It can also serve as a useful way for the researcher to avoid biases that we human beings are prone to when observing and interpreting the surrounding world, given both preconceptions and the basic setup of our cognition. What computer-aided text analysis cannot do, however, is to provide the framework for interpreting and explaining observations of change and continuity. For that, existing and new theoretical approaches and the traditional humanistic methods of hermeneutics and contextualization still reign supreme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. For a recent sample of case-studies on translations and commentaries to the Qur’an in different languages, see Taji-Farouki (Citation2015). For lengthy discussions on the notion of iʿjāz in relation to Qur’an translations, see al-Amri (Citation2010).

2. I would here like to offer thanks to librarian Sara Bünger at Linnaeus University Library who helped me to track down and order one of the rare copies of this book from a second-hand book shop in India.

3. For details, see http://www.ahmadiyya.org/movement/shakir.htm (accessed August 17, 2018) and links from this page. The page is apparently continuously updated when new information is gained on diverse issues, including the identity of M.H. Shakir himself.

4. See here for example Kidwai’s refusal to place the seven Ahmadiyya translations discussed in the category of ‘Muslim’ translations in his overview of translations into English (Kidwai Citation2011, 195–232). See also his refusal to acknowledge Mohammad Abdul Hakim Khan’s translation of 1905 as the first Muslim translation of the Qur’an (Kidwai Citation2009). It is noteworthy that this view that Ahmadiyya Muslims are non-Muslims appears to be shared by the occasional Islamic Studies scholar. See, for example, Robinson’s evaluation in his 1997 article on ‘sectarian’ translations of the Qur’an (Robinson Citation1997, 265).

5. Here it can be noted that al-Amri (Citation2010, 106–108) discusses the translations by both the ‘Monotheist Group’ and Yuksel et al. without mentioning any connection between them.

6. Hence, there is little support in the current study for Kidwai’s (Citation2017, 236) assertion that Pickthall’s translation ‘inspired scores of later Muslim writers to produce their versions in their own varied ways. Many of them stand indebted to him for having provided them with apt English equivalents for a range of Arabic/Quranic terminology’. Kidwai makes several claims of later translators plagiarizing Pickthall. None of those mentioned are in the set that the present article uses, so his allegations can neither be strengthened nor questioned at this stage.

7. For an interesting study of the different receptions of Muhammad Ali’s translation in Indonesia and Egypt, see Nur Ichwan (Citation2001).

References

- Al Ghamdi, Saleh A.S. 2015. “Critical and Comparative Evaluation of the English Translations of the Near-Synonymous Divine Names in the Quran.” PhD Diss. University of Leeds.

- al-Amri, Waleed Bleyhesh. 2010. “Qur’an Translation and Commentary: An Unchartered Relationship?” Islam & Science 8 (2): 81–110.

- Al-Ghazalli, Mehdi F. . 2012. “A Study of the English Translations of the Qur’anic Verb Phrase: The Derivatives of the Triliteral.” Theory and Practice in Language Studies 2 (3): 605–612. doi: 10.4304/tpls.2.3.605-612

- Al-Saggaf, Mohammad Ali, Mohamad Subakir Mohd Yasin, and Imran Ho Abdullah. 2013. “Cognitive Meanings in Selected English Translated Texts of the Noble Qur’an.” QURANICA: International Journal of Quranic Research 4 (1): 1–18.

- Ali, Muhammad. 1917. The Holy Qur-án: Containing the Arabic Text with English Translation and Commentary. Woking: The ‘Islamic Review’ office.

- Amazon.com. 2018a. “The Qur’an & Tafsir Ibn Kathir: Part 1.” Accessed 1 October, 2018. https://www.amazon.com/Quran-Tafsir-Ibn-Kathir-Part/dp/B00D0EC8KI.

- Amazon.com. 2018b. “Quran 2012.” Accessed 1 October, 2018. www.amazon.com/Quran-2012-Bilal-Muhammad/dp/1477479651.

- Amazon.com. 2018c. “Quran: Translations Compiled by Members of the Imam W.D. Mohammed Community Kindle Edition.” Accessed 1 October, 2018. www.amazon.com/Quran-Translations-Compiled-Mohammed-Community-ebook/dp/.

- Bobzin, Harmut. 2001. “Translations of the Qur’an.” In Encyclopaedia of the Qur’an [online], edited by Jane Dammen McAuliffe. Leiden: Brill.

- Friedmann, Yohanan. 2007. “Ahmadiyya.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam THREE [online], edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Everett Rowson. Leiden: Brill.

- Gomaa, Wael H, and Aly A Fahmy. 2013. “A Survey of Text Similarity Approaches.” International Journal of Computer Applications 68 (13): 13–18. doi: 10.5120/11638-7118

- Greifenhagen, Franz V. 1992. “Traduttore Traditore: An Analysis of the History of English Translations of the Qur’an.” Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 3 (2): 274–291. doi: 10.1080/09596419208720985

- Hassen, Rim. 2011. “English Translation of the Quran by Women: The Challenges of ‘Gender Balance’ in and Through Language.” MonTI. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación (3): 211–230. https://dti.ua.es/es/documentos/monti/monti-3-cubiertas-indices-y-resumenes.pdf doi: 10.6035/MonTI.2011.3.8

- Jonker, Gerdientje. 2015. The Ahmadiyya Quest for Religious Progress: Missionizing Europe 1900–1965. Leiden: Brill.

- Khalifa, Rashad. 1981. Qur’an: The Final Testament: Self Published.

- Khan, Mofakhkhar Hussain. 1986. “English Translations of the Holy Qur’an: A Bio-Bibliographic Study.” Islamic Quarterly 30 (2): 82–107.

- Kidwai, Abdur Raheem. 2009. “Mohammad Abdul Hakim Khan’s The Holy Quran (1905): The First Muslim or the First Qadiani English Translation?” Insights 2 (1): 57–72.

- Kidwai, Abdur Raheem. 2011. Translating the Untranslatable: A Critical Guide to 60 English Translations of the Quran. New Dehli: Sarup.

- Kidwai, Abdur Raheem. 2017. “Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall’s English Translation of the Quran (1930): An Assessment.” In Marmaduke Pickthall: Islam and the Modern World, edited by Geoffrey P. Nash, 231–248. Leiden: Brill.

- Lawrence, Bruce B. 2017. The Koran in English. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mohammed, Khaleel. 2005. “Assessing English Translations of the Qur’an.” The Middle East Quarterly 12 (2): 58–71.

- Muhanna, Elias. 2016. The Digital Humanities and Islamic & Middle East Studies. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Murah, Mohd Zamri. 2013. “Similarity Evaluation of English Translations of the Holy Quran.” Paper presented at NOORIC Taibah University International Conference on Advances in Information Technology for the Holy Quran and Its Sciences, Medina, 22–25 December 2013.

- Musa, Aisha Y. 2010. “The Qur’anists.” Religion Compass 4 (1): 12–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00189.x

- Nur Ichwan, Moch. 2001. “Differing Responses to an Ahmadi Translation and Exegesis: The Holy Qur’ân in Egypt and Indonesia.” Archipel 62 (1): 143–161. doi: 10.3406/arch.2001.3668

- Olsson, John. n.d. “A Report into Several Translations of the Holy Quran.” Accessed October 1, 2018. www.muslim.org/intro/ShakirPlagiarismReport.htm.

- Robinson, Neal. 1997. “Sectarian and Ideological Bias in Muslim Translations of the Qur’an.” Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 8 (3): 261–278. doi: 10.1080/09596419708721126

- Safeena, Rahmath, and Abdullah Kammani. 2013. “Quranic Computation: A Review of Research and Application.” Paper presented at NOORIC 2013: Taibah University International Conference on Advances in Information Technology for the Holy Quran and Its Sciences, Medina, 22–25 December 2013.

- Scrivener, Leslie. 2007. “Furor Over a Five-Letter Word.” Toronto Star, October 21.

- Shellabear, W. G. 1931. “Can a Moslem Translate the Koran?” The Muslim World 21 (3): 287–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-1913.1931.tb00846.x

- Sideeg, Abdunasir I.A. 2015. “Traces of Ideology and the ‘Gender-Neutral’ Controversy in Translating the Qurān: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Three Cases.” Arab World English Journal (4): 167–181.

- Submitters, International Community of. 2018. “Masjid Tucson (Mosque of Tucson): Official Website.” Accessed 1 October, 2018. http://www.masjidtucson.org/m_index.html.

- Taji-Farouki, Suha. 2015. The Qur’an and Its Readers Worldwide: Contemporary Commentaries and Translations. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vijaymeena, M. K., and K. Kavitha. 2016. “A Survey on Similarity Measures in Text Mining.” Machine Learning and Applications: An International Journal 3: 19–28.

- Wild, Stefan. 2015. “Muslim Translators and Translations of the Qur’an into English.” Journal of Qur’anic Studies 17 (3): 158–182. doi: 10.3366/jqs.2015.0215

- WorldCat. 2018. “Tafsir ibn Kathir (abridged).” Accessed 1 October, 2018. www.worldcat.org/title/tafsir-ibn-kathir-abridged/oclc/46570044.