ABSTRACT

While there is consensus among those working to prevent violence against women and girls of the need to develop the capacity of researchers and implementers working in the global South, there is insufficient evidence on how to effectively achieve this. This article reflects on the approaches used by the What Works programme to develop capacity. It recommends that effective capacity development requires: meaningful commitment; an organic process driven by the needs of the global South; recognising the importance of soft-skills; acknowledging what is achievable within resource constraints; and a commitment to women’s rights and gender equality.

Introduction

Preventing violence against women and girls (VAWG) is central to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and is dependent upon supporting the next generation of researchers and implementers in the global South, develop, implement and evaluate interventions to achieve these aims. Despite agreement that this is necessary, capacity development with southern partners is rarely approached rigorously, or adequately resourced. Few donors, large consortiums or programmes have adequate capacity development strategies, budgets or time allocated for this. Furthermore, capacity development strategies often fail to meaningfully place southern implementers and researchers at the centre of the process, inadvertently reinforcing unequal relationships of power or dependency, and limiting the effectiveness of VAWG research and interventions. This article discusses a capacity development strategy focused on strengthening researchers’ and implementers’ ability to undertake VAWG programming and research in the global South. Through a case study of the “What Works to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls? Global Programme” (What Works), we reflect on approaches to capacity development to inform future capacity development programmes.

In this article we refer often to the “global South”. From the mid-1990s the term “global South” was used to refer to regions outside of Europe and North America, including Latin America, Asia, Africa and Oceania, characterised by being mostly low-income and often politically or culturally marginalised (Dados and Connell Citation2012). It references to the history of colonialism, neo-imperialism and differential economic and social change through which large inequalities in living standards, life expectancy and access to resources are maintained (Dados and Connell Citation2012). While the global South remains contested as a concept, we use the term as it is less hierarchical than “the developing” or “Third World”.

Background to VAWG capacity development in the global South

In the late 1980s, development aid started to focus on “capacity development”, moving away from dependency-centred models of development (Lusthaus, Adrien, and Perstinger Citation1999). Despite limited rigorous debate and shared understanding of capacity development concepts and methods, common themes can be observed across the literature.

There has been a shift away from capacity “building” towards capacity “development”, with capacity development focusing on working with and developing existing capacities of organisations and individuals in a collaborative way (Ubels, Acquaye-Baddoo, and Fowler Citation2010). Whereas, earlier theories of capacity building tended to focus on bringing in external expertise to build something new, with little recognition of existing skills and knowledge (Land et al. Citation2008). Building on the shift towards capacity development, the literature emphasises the importance of collaborative partnerships fostering “country leadership and ownership”, and “more south-south cooperation in support of increasingly sustainable outcomes” (Pearson Citation2011, 12). This has sought to destabilise linear development approaches that focus on the global North “helping” the global South, rooted in neo-colonialist assumptions of aid, towards recognising the imperative of knowledge developed in the global South as providing a different, and more contextually relevant form of knowledge (Rihani Citation2002). Despite broad commitment towards more equitable and empowering approaches to capacity development, traditional capacity building approaches remain dominant. These include one-off training, which tends to be situated within the lower end of Kaplan’s capacity hierarchy, focused on material and financial resources, and ignores critical factors such as organisational strategy and values.Footnote1 This reflects Simister and Smith’s (Citation2010) distinction between capacity development as a “means to an end”, or as “an end in itself”. To elaborate, an organisation might be supported to develop staff capacity or their internal systems and/or structures, with significantly less emphasis on less tangible, but necessary, processes of “reflection, inspiration, adaptation” (Simister and Smith Citation2010, 5).

Within VAWG prevention there is a growing understanding of what works to prevent VAWG from a programming and policy perspective (Ellsberg et al. Citation2015). However, there remains limited reflection and documentation of effective strategies to develop the capacity of VAWG implementers and researchers, despite recognition that capacity gaps are hampering progress on VAWG prevention (Dartnall and Gevers Citation2017).

Another key approach for successful capacity development within the field of VAWG prevention has been an emphasis on meaningful collaboration between southern research institutions and NGOs working on VAWG prevention; often referred to as South-to-South collaborations (Campbell and Mannell Citation2016; Chu et al. Citation2014). Importantly such approaches ensure that interventions and research resonate with local needs and requirements, and helps assist researchers from the global South to “lead, fund, develop, test and publish locally relevant VAW and VAC [violence against children] prevention programmes” (Dartnall and Gevers Citation2017, 9).

Case study – What Works

What Works is a five year, £25 million, four component, multi-country programme funded by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) to support research and implementation of VAWG prevention in the global South. It is one of only a few large consortia in the VAWG sector with an explicit mandate to strengthen the capacity of southern researchers and implementers.

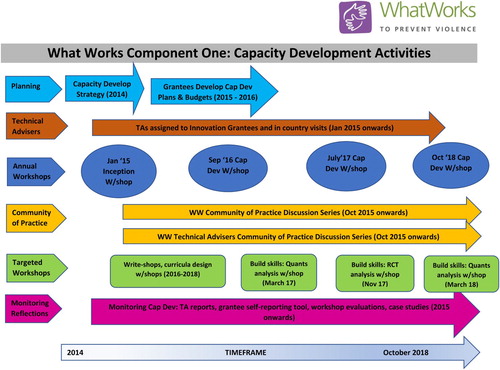

What Works Global Programme (Component One) is managed by three organisations, the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), as the Secretariat, together with Social Development Direct (SDDirect), and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). What Works supported two types of VAWG prevention studies: six large-scale randomised control trials (RCTs) evaluating the impact of promising VAWG prevention interventions (impact evaluations), and 10 innovation grants that developed or adapted interventions, and evaluated them through either pilot studies, or RCTs. Grants were awarded in 2014, and the capacity development programme began in 2015, based in part upon the capacity development strategy drafted by the What Works consortium in 2014, and informed and adjusted based on emerging grantee needs.

This article is based on an inductive thematic analysis of monitoring data used in the What Works programme collected over the three years when most activities occurred. This included a bi-annual self-completed tool monitoring individual grantee capacity growth, quarterly grantee reports, and reports from technical advisers (TAs). In addition, to capture capacity development, we conducted eight in-depth case studies with grantees in the final year around their capacity development experiences, as well as workshop exit interviews and a focus group with TAs reflecting on their experiences of providing capacity development.

Capacity development needs and approaches

In January 2015, a week-long inception workshop brought together grantees, the technical team and management for the first time. This was an opportunity to meaningfully explore grantees skills and needs through interaction with the technical team and an online assessment. This revealed greater capacity needs among most grantees than previously anticipated. In June 2015, a dedicated capacity development manager was appointed to oversee the capacity development strategy. This appointment was critical as it meant capacity development had a champion to drive it as a core activity of What Works:

The appointment of a lead person on capacity development was extremely positive and resulted in a step change in how capacity development was organised and communicated, which I and the grantee have greatly appreciated. (Technical Adviser, exit interview, October 2017)

The capacity development manager’s role included developing a strategic vision, identifying and responding to shifting capacity development needs, and implementing and monitoring the programme-wide activities.

At the start of the programme in 2014, it was assumed only innovation grantees would require capacity development support; however, the inception period (year one) revealed What Works had underestimated the needs of many of the grantees and the time needed to undertake high-quality formative research, and intervention adaptation and design. Furthermore, many of the impact evaluations required significant support to design and implement RCTs, and in some cases develop and adapt their interventions. In response, What Works expanded the capacity development portfolio to provide all grantees with the necessary support and increased the role and numbers of TAs.

Capacity gaps covered five key areas: (i) thematic knowledge such as VAWG prevention, gender equality, economic empowerment, and working with children; (ii) evidence-based intervention design; (iii) research design and implementation; (iv) research uptake; and (v) programme management. A number of grantees also needed intense support with their formative research. The scope of work was significant, and it is estimated the capacity development portfolio utilised 10% of the programme’s overall funds.

The capacity development approaches and activities were guided by recent shifts in good practice around effective capacity development, namely that it should build on existing skills and knowledge. The activities while grounded in the original strategy, also responded to emergent demands and on many occasions developed organically in response to shifting needs. Each innovation grant had bespoke plans based on their areas of need, and these too remained responsive to change. This adaptive element of capacity development was critical to its success. Activities included three capacity development workshops for all grantees (2016–2018), a series of ad hoc, smaller workshops building specific skills among targeted grantees, ongoing mentoring and support to grantees from a team of TAs, in-country technical visits, an online community of practice (CoP), and ongoing monitoring of the process. In some cases, local providers ran training on research and facilitation skills and organisational development.

From the outset, What Works' broad philosophical approach to capacity development drew on reflective, participatory learning processes, and was respectful of local knowledge and experience, while imparting new knowledge and skills as needed. This was captured in the strategy as “guided learning by doing” supported by technical experts, who utilised guidance and mentoring rather than instruction and was driven by the intrinsic values of the leadership and technical team. Different approaches were used depending on need, in some cases through facilitating local knowledge and in others through introducing new knowledge and skills, such as how to analyse data or write a policy brief. Many individuals received extensive mentoring, and whole-team capacity growth was also encouraged through sharing knowledge, skills and reflection while working as a team to apply new knowledge to project data.

While this paper focuses on processes and approaches rather than impact, extensive monitoring data over three years showed significant capacity growth among Southern grantees. The bi-annual capacity development monitoring tool showed continuous growth across all skills sets by all grantees, and the external evaluation commended the work as innovative and effective. Eight-nine per cent of all What Works published peer-reviewed journal articles include southern authors, many publishing for the first time. The commitment by What Works to ensuring the involvement of southern authors, including those implementing interventions, sought to reverse the trend whereby publications are written by northern researchers, excluding southern partners. Additionally, almost a third of the grantees have developed skills in adapting and developing VAWG prevention interventions.

The different components of the capacity development strategy are included in and discussed in detail below.

Technical advisers

TAs provided bespoke support to What Works projects and served as critical enablers of grantees’ capacity growth. The focus of TA support and time allocated varied depending on grantee needs and project stage. In some cases, grantees were allocated one or two specifically contracted TAs for three years. In other cases, principal investigators (PIs) acted as TAs to junior colleagues and/or implementing partners, or members of the Secretariat supported capacity growth around specific skills or knowledge areas.

TA matching is not an exact science and adjustments were often made. In two cases, the TA-grantee relationship was challenging, and a new TA was allocated. In other cases, a TA could not meet all the needs and an additional TA was allocated; for example, a TA may provide excellent VAWG prevention and research design skills, but not have intervention adaptation skills, or would be a gender expert but not have VAWG prevention knowledge. Initially, for most of the 10 innovation grantees there was one TA allocated 20 days per year, over three years. In many cases this was an underestimation, and nearly all were allocated additional TA support, largely from the Secretariat, ranging from an additional 5 to 60 days. The relationship between the TA and grantee was closely supported and monitored by the capacity development manager to identify shifting needs or ineffective matchings.

TA support usually involved two in-country visits (of four to six days), and in a few cases additional visits were undertaken (with one project receiving five visits). The bulk of support and mentoring was undertaken through email, virtual meetings, telephone discussions and during ad hoc capacity development workshops, or side meetings at bigger What Works meetings.

TAs were largely female and came from both the global South and North. Experience varied, with more effective TAs tending to have 10 plus years' experience, including working in the global South with NGOs or research institutes. Several TAs had experience in gender and development, and women and girl’s rights, rather than VAWG specifically, though those with experience on the latter were at a significant advantage. Some had specific experience working in the country or on the thematic area that the grantee was focusing on, though grantees said that this was not critical (Grantee, capacity development case study).

The What Works experience suggests effective TA support to projects was based on three factors. First, TAs needed appropriate technical skills to support the grantees needs, and these needs often shifted over the life of each project. Matching TAs’ technical skills to project needs, and adding additional support as necessary, was critical to successful capacity development:

The importance of [the TA] having strong technical skills, an ability to adapt to the different and changing capacity needs and being able to provide bespoke support to different team members depending on their needs, was seen to be critical to “making sure that everyone understood what was happening”. (Grantee, Afghanistan case study)

Second, the TAs' “soft skills” and ability to build relationships of trust with grantees was critical and was repeatedly stressed in feedback from grantees and TAs. Face-to-face meetings and early in-country visits were key to building these relationships, and to developing a deeper appreciation of constraints, and opportunities, grantees faced. TAs noted the imperative of having a trusting and respectful relationship with grantees, to support deeper learning and on occasions bridging relationships between implementing and research partners, or with the Secretariat. Grantees talked about appreciating when TAs worked through facilitated discussions, and joint decision-making, rather than top-down processes: “Our TA didn’t make decisions for us – we made decisions together” (Grantee, Kenya).

Alongside soft skills, the TAs' personal values were also important for successful relationships:

The TA’s values and attitudes and being able to create a safe space for critical yet supportive discussions, where all voices are heard and respected, was seen as the “door-opener” to a successful TA-grantee relationship. (Grantee, Tajikistan case study)

Potential power dynamics within TA-grantee relationships cannot be ignored. Even when TA-grantee relationships were highly effective, there were inevitably power dynamics between TAs and grantee organisations, relating to individual background and experience. For example, when the TA came from the global North and the staff from the grantee organisation from the South, historical associations of power and privilege, linked to the colonial past, were more present than when both TA and grantee staff were from the global South. TAs from the global South often came with a nuanced understanding of the complexities of intervention delivery and conducting research within southern contexts, which quickly allowed them to establish an open and equal relationship and knowledge exchange. In comparison, many northern-based TAs came with a certain degree of privilege and therefore had to use their soft skills, and demonstrate personal values of respect and equality, to build equitable relationships with southern partners. For the most part, northern TAs were able to do this, though some found this harder, which led to changes in some TA-grantee matching. About half of the TAs were based and identified as coming from the global North, the rest were southern or had lived there for a long time, and all grantees were based in the global South.

Finally, the TAs’ understanding of gender and development, women’s rights and VAWG, was critical for their success in building relationships and effective capacity development. Specific knowledge of a country or region was not essential, as knowledge of the specific setting could be developed through an early in-country visit. However, a broad understanding of, and commitment to, VAWG prevention and gender equality was critical to ensure that the ideas and approach were translated and constantly reinforced in practice.

While grantees reported that TA support was generally very effective, it was suggested that TAs would have benefited from greater guidance at the beginning around the capacity development vision and approaches. Spending time with all the TAs at the start of the programme to ensure a shared understanding of the principles of “guided learning by doing”, participatory knowledge sharing, and southern-driven capacity development would have been beneficial.

Capacity development workshops

What Works convened three annual one- to two-day capacity development workshops, attended by all grantees (60–70 participants). While these were in the original strategy, the specifics were designed in response to evolving needs of the What Works programme and grantees. The first, in 2016, focused on supporting research skills for VAWG prevention work. The second, in 2017, focused on research uptake. The final workshop in 2018 focused on sustainability and taking the work forward beyond What Works.

In addition, following the identification of skills gaps among specific grantees, the Secretariat facilitated a series of group workshops with one to three projects and around 10 participants, which were one-week long and targeted specific skills relevant to those projects. While these ad hoc workshops were primarily designed for skills transfer, the method remained guided learning by doing, using the cycle of teaching, applying, and reflection. They were supported by a technical team to ensure sufficient mentoring and support. Workshops included developing an evidence-based intervention curriculum, writing and presentation skills, and quantitative data analysis.

Grantees reported both types of workshops were important learning spaces, and particularly appreciated the process of learning, action and reflection:

The event was “Marvellous”. In terms of the use of applied learning. Active in methodology. Rich in content. Vigorous in tasks. Enormous in facilitation quality and experience. I learned by doing. (Capacity development workshop, 2017, post-workshop survey)

Workshops were successful due to four factors. First, the focus of workshops was agreed in consultation with grantees, based on formal and informal needs assessments from several sources (pre-workshop survey, grantees self-reporting, TA reflections, secretariat assessments, etc.). Second, both intervention and research partners participated. While costly and resulting in very large workshops, it provided essential spaces for the partners to spend time together creating a sense of unity and peer support. Third, activities in the workshops followed the guided learning by doing approach. While there were some taught areas to share new skills, large sections were allocated for working in project teams to apply and reflect on the learning. During most activities, grantees worked in project teams using their own project data to apply key ideas and approaches and reflect. Fourth, session planning and delivery involved southern grantees and southern grantees ran sessions, challenging the idea that skills transfer flows from the North to the South.

The What Works community of practice

A key component of capacity development in What Works was creating spaces for continued sharing and learning among grantees and between grantees and the technical team. Given the global spread of grantees, this was done through supporting an online “community of practice” (CoP), primarily through regular webinars. While most emphasis was on sharing information or skills, the intention of the CoP was to build a sense of a What Works community to share ideas and experiences among grantees and the technical team.

Establishing an effective CoP was challenging. The initial approach aimed to establish five online discussion groups, focused on different topics. The six-month pilot review found the plan over-ambitious, with too many groups resulting in coordinators and participants feeling overwhelmed. Attempts to encourage grantees to engage in regular online chat forums also failed, perhaps as many were field based and did not have continuous online access. The one group that did work was for the TAs.

Despite these challenges, grantees continued to request the Secretariat to support spaces for peer sharing and learning. In response, a new approach was developed, with one regular CoP discussion series, every 6–8 weeks, hosted online. Each discussion session had a different focus, including skills development, and sharing knowledge and project experiences, and was led by the technical team often with grantees as co-presenters. Topics covered in the CoP included writing a blog, challenges in endline research, and women living with disabilities and VAWG. The revised approach proved more successful, with a consistent attendance of around 35 participants who became more active and confident over time, with a significant increase in sharing and discussion during the sessions. Discussions were held in English, as a common language, which had limitations for those less fluent in English.

The What Works CoP discussion series succeeded in bringing grantees together for four reasons. First, through limiting attendance to What Works grantees only, emphasis was placed on keeping this a safe space where grantees could explore ideas and ask questions freely. Second, to maximise participation by southern grantees, all sessions were held during working hours in Asia and Africa. This meant that discussions were often too early for those in the far West (e.g. USA), unfortunately excluding some research partners. While this timing issue may appear obvious, it is often ignored with global development webinars. Third, using an appropriate online conferencing system, with low bandwidth and simple functionality ensured it was easy for participants to use and minimised connectivity problems. The online conferencing system also had a chat function allowing participants to write comments to be read out by the facilitator; this was popular, particularly with participants who felt uncomfortable asking questions directly. Fourth, the selection of discussion themes and presenters reflected the interests of the different projects and covered the breadth of needs from sharing the latest evidence, to technical skills and spaces to reflect.

It took time to build and nurture a What Works CoP, especially when dealing with challenges such as multiple languages and time zones, interactions being primarily virtual, and where there were real or perceived power imbalances. Nonetheless, grantees reflected they had found the CoP discussions important spaces to engage and learn from others within What Works. Furthermore, increasingly by year four, grantees reached out, independently of the Secretariat, to each other to talk, trouble-shoot and explore new opportunities together, forming relationships which are likely to be sustained beyond the programme.

Capacity development planning, budgeting and monitoring

To embed capacity development in all What Works activities, each of the 10 innovation grants was required to develop project-level capacity development plans and set aside approximately 4% of budget towards achieving these. The Secretariat also allocated centrally managed funds to capacity development. However, developing the project-level plans and allocating budgets was complex and took time. There was an initial donor expectation of clear capacity development plans and budgets, at both project and Secretariat level that would be neatly executed. However, the reality was that these processes were dynamic, and could not be neatly planned at inception, and for most grantees, capacity gaps emerged over the project. This meant some grantees drafted project-level capacity development plans before a comprehensive picture of needs had emerged. For instance, the skills and support required to develop rigorous evidence-based interventions were initially significantly underestimated by many. Furthermore, impact evaluations were not required to develop capacity development plans, yet it became evident that many would benefit from being a part of the capacity development portfolio. In addition, there were ongoing conversations with grantees about which activities fell under capacity development, for example whether training of field workers was capacity development or preparation for fieldwork. The late appointment of the capacity development manager and related delay in issuing the Secretariat’s guidance around capacity development added to challenges. Additionally, the TA was often key in facilitating the necessary reflections to develop the plans, a process which was richer once the TA-grantee relationship had had time to deepen, often following the first TA in-country visit. In response, What Works moved to encouraging the plans to be dynamic and organic, with ongoing monitoring and reflections, leading to changing plans; allowing this flexibility was essential for meaningful capacity development.

The capacity development portfolio was continuously monitored to assess delivery, shifting needs and impact. To do this, multiple informal and formal methods were employed, and these too shifted over time. Informal monitoring, relying largely on the close relationships and knowledge that TAs, the capacity development manager and Secretariat proved particularly effective in identifying shifting needs and shaping activities. This was supplemented by extensive formal monitoring by grantees, TAs and the capacity development manager, the detail of which is referred to above when noting the formal sources of monitoring data reviewed for the paper.

What Works identified four key lessons for successfully developing and implementing meaningful project-level capacity development plans. First, the process itself was important, with innovation grantees reporting that being required to draft capacity development plans and budgets was relatively unique and that it ensured the centrality of capacity development in the programme:

Team members emphasised the importance of dedicating specific time and resources to capacity development within projects, highlighting that this was unique to any other projects they had worked on before, and that “setting aside a budget line for it [capacity development] is really important”. (Bangladesh, case study)

Second, project-level capacity development plans and budgets were developed through a participatory process, as opposed to one person undertaking a tick-box exercise, which led to the process in and of itself developing capacity and ownership of the plans. Third, effective delivery against these plans was dependant on support from TAs, and was most effective when there was a good TA-grantee match.

Finally, the formal and informal monitoring systems were critical for ensuring that the capacity development agenda was responsive and shifted as needed. While there were clear capacity development plans and budgets, most shifted significantly over the years, and without the ability to remain responsive and adapt plans the programme would have failed to meet the significant and changing needs of grantees.

Discussion

Strengthening southern researchers’ and implementers’ capacity to undertake VAWG prevention interventions and research remains imperative to preventing VAWG. In this discussion we draw out eight themes from the What Works experience which were found to be key for effective capacity development: (1) meaningful commitment to capacity development; (2) a focus on foundational skills beyond research and interventions; (3) capacity development as an organic process; (4) driven from the global South; (5) participatory and empowering approaches; (6) the importance of soft skills; (7) recognising limitations within resource constraints; and (8) a commitment to women’s rights and gender equality.

Meaningful commitment

Meaningful commitment from leadership is critical to successful capacity development and is needed across the overall programme vision, operational plans, and resource investments. Commitment towards meaningful capacity development was demonstrated within What Works by the donor and the management consortium. The donor explicitly included southern capacity development as a core deliverable within the request for proposals. The What Works leadership demonstrated its commitment through the principles captured in the Capacity Development Strategy (2014), “The Consortium is committed to growing the next generation of Southern researchers and practitioners in the VAWG prevention field”. As well as through “walking the talk” by placing capacity development at the centre of the programme, and allocating significant resources. Capacity development will only be effective with substantial financial investments and commitment.

The appointment of a dedicated capacity development manager, demonstrated What Works commitment while also strengthening strategic planning, implementation and accountability. Leadership support for integrating capacity development across activities was important. For example, where possible project teams were brought together to develop their analysis skills rather than a statistician or senior researchers simply doing the analysis themselves, and research uptake was driven by a capacity development lens, including intensively supporting southern authors and presenters.

Foundational skills

Capacity development needed to move beyond strengthening VAWG research and intervention skills to include general organisational skills, including report writing, and financial and project management. Additionally, most grantees needed support to undertake effective and innovative research uptake, including intensive support to translate research findings into key messages and multiple outputs. While these skills are not specific to VAWG prevention, they are foundational skills needed to enable organisations to undertake ongoing high-quality VAWG prevention work.

Organic process

Capacity development is an organic process that while supported by plans, budgets and reporting, needs flexibility. The What Works experience showed that it is not possible to accurately identify all capacity development needs at inception, it takes time to develop a comprehensive picture of teams’ skills and needs, which shift over the life of the project. These shifting needs can be supported if work is allowed to adapt and through close monitoring, plans and resources are adapted.

Driven from the global South

Central to the success of the capacity development programme was that it was driven from the global South. The Secretariat and many TAs were located in the South, and southern grantees were central to directing and shaping their own capacity development. As is increasingly recognised, in VAWG, and gender studies, the global South has been central in driving the field forwards (Hodes and Morrell Citation2018) and providing frameworks for conceptualising new sets of relationships in the production of knowledge locating an increased power to the global South.

Having the What Works Secretariat and several TAs being physically and symbolically located in the South enabled different relationships with grantees, often with a deeper understanding of implementation difficulties. While being based in the global South does not automatically lead to a southern focus, more relevant knowledge or to questioning historical northern dominance, it is relevant in challenging the northern hegemony in global health and development. For What Works the process was, in many cases, a South-to-South learning process, inverting hierarchies in the production of knowledge and capacity development.

Philosophical approach

The philosophical approach to capacity development within What Works emphasised a participatory, learning through doing, approach, delivered over a number of years. This was demonstrated through both how capacity development was undertaken, but also who led such processes. Providing space for grantees to lead workshop sessions and ensuring that processes supported broad knowledge sharing and critical reflection, rather than simply skills transfer.

Importance of soft skills

TAs’ soft skills were central to effective capacity development and enabled effective mentoring and guidance to the grantees, and assisted bridging different workstyles and expectations. Once the TA-grantee relationship was strong, the TA often played a core role in building grantee self-confidence, and navigating misunderstandings and frustrations between different players, including researchers, intervention partners and programme management. Having the necessary soft skills to work through moments of tension, and professional self-doubt, was key for sustained capacity development. This is because such relationships involve power and feelings, as well as rational negotiation (Pasteur and Scott-Villiers Citation2006) and it is critical that these are openly recognised and navigated.

Recognising what is achievable within resource constraints

Capacity development will experience resource constraints as it competes with other budget priorities, therefore realistic objectives need to be set. In What Works, the TA and Secretariat worked with grantees to assess the extent to which individual capacity development plans were achievable. In some cases, this meant recognising that certain skills could not be supported effectively at a distance, on a limited budget. These constraints also meant much of the capacity development occurred at the individual level, as intense distant support with limited funds is difficult to scale up to organisational level. What Works grantees experienced incredible growth but there are limits to what is achievable within resource constraints.

A commitment to women’s rights and gender equality

Finally, development work, including research and programming for VAWG prevention, risks becoming depoliticised (Wallace and Porter Citation2013) and a technical tick-box exercise, rather than politically transformative. In many ways incorporating gender equality and women’s rights into intervention and research design and delivery is the simple part, the more significant challenge arises in how to integrate this into internal operational and strategic processes. As Dartnall and Gevers (Citation2017) note, the project team needed to internalise and live the project principles, which on occasions requires personal transformative work. What Works, including the capacity development process, was committed to women’s rights and gender equality and ensuring this was at the forefront of the work. This was as much about the TAs' skills as about how support was delivered, linking back to the need for soft skills and respectful TA-grantee relationships.

Conclusion

Capacity development of VAWG prevention implementers and researchers in the global South will remain a dominant component of development aid for the foreseeable future. Funded by donors in the global North, it is likely to remain embroiled in complex politics of power and inequality. Throughout such processes, final decision making around which projects get funded, how funds are allocated, and what “success” is, tends to remain located in the global North. This said the What Works programme of capacity development provides insights into how such processes can be done differently in ways that support a more transformative agenda.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all What Works project partners who were involved in this capacity development journey, we learnt so much from you.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Samantha Willan is Capacity Development Manager at the What Works programme and has 20 years’ experience working in the global South on women’s rights, VAWG and capacity development.

Alice Kerr-Wilson is a Technical Adviser on the What Works programme and Senior Associate at Social Development Direct, London. Kerr-Wilson has 15 years’ experience working on gender equality and women and girls’ rights.

Anna Parke is a gender equality and social inclusion Technical Specialist with Social Development Direct, London, with expertise in women’s political empowerment and VAWG.

Andrew Gibbs is a Senior Specialist Scientist at the What Works programme, at the Gender and Health Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council. Gibbs has over 10 years’ experience working on gender and VAWG in the global South.

ORCID

Samantha Willan http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8629-887X

Andrew Gibbs http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2812-5377

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Kaplan (Citation1999) described capacity as seven interrelated elements in an organisational setting – ranging from an organisation’s conceptual framing through to material resources, highlighting the often-invisible nature of some of these elements. While material and financial resources, skills, organisational structures and systems tend to be the more visible within the hierarchy, vision, strategy and cultural values are often invisible (Datta, Shaxson, and Pellini Citation2012).

References

- Campbell, C., and J. Mannell. 2016. “Conceptualising the Agency of Highly Marginalised Women: Intimate Partner Violence in Extreme Settings.” Global Public Health 11 (1–2): 1–16. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1109694

- Chu, K. M., S. Jayaraman, P. Kyamanywa, and G. Ntakiyiruta. 2014. “Building Research Capacity in Africa: Equity and Global Health Collaborations.” PLoS Medicine 11 (3): e1001612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001612

- Dados, N., and R. Connell. 2012. “The Global South.” Contexts 11 (1): 12–13. doi: 10.1177/1536504212436479

- Dartnall, E., and A. Gevers. 2017. “Harnessing the Power of South-South Partnerships to Build Capacity for the Prevention of Sexual and Intimate Partner Violence.” African Safety Promotion Journal 15 (1): 8–15.

- Datta, A., L. Shaxson, and A. Pellini. 2012. Capacity, Complexity and Consulting: Lessons From Managing Capacity Development Projects. Working Paper 344, London: Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

- Ellsberg, M., D. J. Arango, M. Morton, F. Gennari, S. Kiplesund, M. Contreras, and C. Watts. 2015. “Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls: What Does the Evidence Say?” Lancet 385 (9977): 61703–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7

- Hodes, R., and R. Morrell. 2018. “Incursions From the Epicentre: Southern Theory, Social Science, and the Global HIV Research Domain.” African Journal of AIDS Research 17 (1): 22–31. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2017.1377267

- Kaplan, A. 1999. The Developing of Capacity. Cape Town: Community Development Resource Association.

- Land, T., N. Keijzer, A. Kruiter, V. Hauck, H. Baser, and P. Morgan. 2008. Capacity Change and Performance: Insights and Implications for Development Cooperation. Policy Management Brief No. 21, December.

- Lusthaus, C., M. H. Adrien, and M. Perstinger. 1999. Capacity Development: Definitions, Issues and Implications for Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation. Universalia Occasional Paper No. 35, Québec: Universalia, September.

- Pasteur, K., and P. Scott-Villiers. 2006. “Learning About Relationships in Development.” In Relationships Matter, edited by R. Eyben, 94–112. London: Earthscan.

- Pearson, J. 2011. Training and Beyond: Seeking Better Practices for Capacity Development. OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers No. 1, Paris: OECD.

- Rihani, S. 2002. Complex Systems Theory and Development Practice: Understanding non-Linear Realities. London: Zed Books.

- Simister, N., and R. Smith. 2010. “Monitoring and Evaluating Capacity Building: Is It Really That Difficult?” Praxis Paper 23, Oxford: INTRAC.

- Ubels, J., N. A. Acquaye-Baddoo, and A. Fowler (eds). 2010. Capacity Development in Practice. London: Earthscan.

- Wallace, T., and F. Porter. 2013. “Introduction: Aid, NGOs and the Shrinking Space for Women: A Perfect Storm.” In Aid, NGOs and the Realities of Women’s Lives: A Perfect Storm, edited by T. Wallace and F. Porter, 1–30. Rugby: Practical Action.