Abstract

Purpose: We aimed to map the physiotherapy practice in Sweden of clinical tests and patient-reported outcome measures in low-back pain (LBP), and to study advantages and barriers in using patient-reported outcome measures.

Methods: An online survey was mailed to 4934 physiotherapists in primary health care in Sweden. Multiple choice questions investigated the use of clinical tests and patient-reported outcome measures in assessing patients with LBP. Open questions investigating the advantages and barriers to the use of patient-reported outcome measures were analyzed with content analysis.

Results: The response rate was 25% (n = 1217). Clinical tests were used “always/often” by >60% of the participants, while most patient-reported outcome measures were used by <15%. Advantages in using patient-reported outcome measures were: the clinical reasoning process, to increase the quality of assessment, to get the patient’s voice, education and motivation of patients, and communication with health professionals. Barriers were lack of time and knowledge, administrative aspects, the interaction between physiotherapist and patient and, the applicability and validity of the patient-reported outcome measures.

Conclusion: Our findings show that physiotherapists working in primary health care use clinical testing in LBP to a great extent, while various patient-reported outcome measures are used to a low-to-very-low extent. Several barriers to the use of patient-reported outcome measures were reported such as time, knowledge, and administrative issues, while important findings on advantages were to enhance the clinical reasoning process and to educate and motivate the patient. Barriers might be changed through education or organizational change-work. To enhance the use of patient-reported outcome measures and thus person-centered care in low-back pain, recommendation, and education on various patient-reported outcome measures need to be advocated.

To increase the effects of rehabilitation in low-back pain, yellow flags, and other factors need to be taken into the consideration in the assessment which means the use of patient-reported outcome measures in addition to clinical testing.

The use of patient-reported outcome measures is an advantage in the clinical reasoning process to enhance the quality of assessment and to educate and motivate the patient.

Barriers to use patient-reported outcome measures are mainly lack of time and knowledge, and administrative aspects.

Through education or organizational change-work, barriers to the use of patient-reported outcome measures might be changed.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Low-back pain (LBP) continues to be the number one disorder as regards years lived with disability worldwide [Citation1]. Thus, people suffering from LBP are among the most common patients seeking primary health care. In Sweden, as in many other countries, patients have direct access to physiotherapists, meaning that there is no need for referral from a general practitioner [Citation2]. This implies that physiotherapists are often the first-line examiners of people seeking primary care, and with a great responsibility for taking risk and prognostic factors into consideration when targeting treatment.

Low-back pain is often recurrent and nonspecific and considered to be a multifactorial condition [Citation3,Citation4]. Physiotherapists use various rehabilitative methods to treat LBP, such as exercises, manual methods, and modalities based on the patient’s history and the physiotherapist's clinical findings. To date, the consensus is that advice to stay active and early return to work is effective treatment for people suffering from LBP, but other than that there is little or no evidence on what are the most effective interventions to prevent LBP from becoming a long-term health concern [Citation5,Citation6].

In everyday work, physiotherapists use various clinical tests to investigate factors such as joint movement, muscle length/strength, and movement control, while the complaint of the patients often is pain and impaired activity level [Citation7–11]. Hitherto, studies of how physiotherapists carry out the clinical assessment in LBP and conduct their clinical reasoning process to target treatment are sparse [Citation12]. Despite this, it has been shown that physiotherapists have appropriate knowledge in managing and treating patients suffering from musculoskeletal disorders [Citation13] as well as a good ability to decide when further medical investigation is needed [Citation14,Citation15]. In addition to clinical testing, patient-reported outcome measurements (PROMs) are recommended in the management and clinical reasoning process to guide and assess improvement of interventions and to benchmark treatment goals [Citation16–20]. However, guidelines for clinical use are still deficient. A comparison of guidelines for the management of LBP showed that Canada and New Zealand were the only countries that recommended specific PROMs for screening psycho-social factors (yellow flags) [Citation5]. However, in recent guidelines to manage LBP from Canada [Citation21] and Denmark [Citation22], PROMs are only briefly mentioned. In Sweden, national guidelines for the management of LBP are lacking, and recommendations for PROMs are sparse [Citation23].

To date, evidence on treatment and prognosis in LBP mostly derives from clinical trials using PROMs as outcome measures. Even so, previous findings report diverse results how physiotherapists use PROMs when targeting treatment [Citation19,Citation24–28]. Studies surveying physiotherapists on their use of PROMs in clinical practice imply both facilitators and barriers, and report a low percentage of the use of PROMs in clinical practice [Citation24–28]. Hitherto, there is insufficient knowledge on to what extent physiotherapists in primary health care, in Sweden, use clinical tests and PROMs in their management of patients suffering from LBP [Citation12]. In addition, barriers, facilitators, and advantages are not previously investigated with open-answer alternatives to get a deeper understanding of why or why not physiotherapists use PROMs in LBP.

We therefore aimed to map the clinical practice of tests and PROMs in LBP used by physiotherapists working in primary health care in Sweden and to study the advantages and barriers to the use of PROMs from the perspectives of the physiotherapists. By mapping the current usage and experienced advantages and barriers, we aim to lay a base for recommendations of usage in physiotherapy clinical work in Sweden.

Methods and Materials

Study design

This is a non-experimental cross-sectional survey study using multiple choice and open-answer questions.

Context of the study

In Sweden, physiotherapist is a regulated profession with a protected title, requiring a license to practice. There are ∼15,000 registered physiotherapists in Sweden. In 2015, 76% of all physiotherapists in Sweden were registered within the Swedish Association of Physiotherapists and 77% were female [Citation29]. Many physiotherapists working in primary health care are advanced clinical specialists with a master’s degree in pain management, manual medicine, primary health care, or sports medicine. All patients have access to (a choice of self-referral) and may utilize publicly financed primary health care with direct access to physiotherapy treatment at a very reasonable cost. Physiotherapists in primary health care work either as private practitioners or in primary care settings.

Setting and participants

Data collection

An online survey (SurveyMonkey®) with multiple choice and open questions (Supplementary Material) was constructed. Email addresses (n = 4934) to a sample of physiotherapists working in primary health care were obtained from the Swedish Association of Physiotherapists (sub divisions of manual therapy, primary health care, pain management and, sports medicine). The aim and execution of the study was explained in an e-mail that contained the survey link. Responders were physiotherapists who worked in primary health care and consequently met with patients suffering from LBP on a regular basis, at least every month. If answered negatively to the question on meeting patients with LBP, they were informed they could not be part of the survey and were thus excluded.

The survey was constructed through discussions among the authors related to their clinical experience and by literature search on clinical testing and PROMs commonly used in LBP. The survey was piloted for understanding the questions among a convenient sample of 38 physiotherapists, both men and women, working in primary health care, one larger and two smaller settings. These survey answers were not included in the main survey. Some minor alterations of wording were made following the pilot study.

Online survey

Eleven multiple choice questions asked the respondent to grade at what frequency a specific clinical test or instrument is used by choosing one of the options “always”, “very often”, “often”, “seldom”, “very seldom” or “never”. For each question, the respondent had the option of listing any instruments not specified in the question, followed by the same choices on frequency. Questions were constructed thoughtfully to be as clear as possible and so as not to be offensive to participants, and in a way, that reduces the risk of misinterpretation.

Questions on use of various clinical test

The survey comprised four multiple choice questions on clinical tests: common clinical tests such as observation of posture; range of motion; neurological tests; muscle strength; muscle length; segmental movement of spinal segments; repeated movements according to Mechanical Diagnostics and Therapy (MDT) [Citation30]; palpation for pain; examination of range of motion in nearby joints and the abdominal draw in maneuver while palpating for activity in the deep abdominals [Citation31], as well as various tests used for observing movement control impairment [Citation9,Citation32].

Questions on PROMs included in the survey

Seven multiple choice questions were included on the respondents use of PROMs: Pain [Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) [Citation33]; Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [Citation34] and Borg’s Category Scale (CR-10) [Citation35]; Disability [Oswestry Disability Index [Citation36], Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire [Citation37], Pain Disability Index (PDI) [Citation38], Disability Rating Index (DRI) [Citation39], Patient Specific Functioning Scale (PFSF) [Citation40]; Quality of life [Short Form 36 (SF-36) [Citation41] and Euroquol 5 dimensions (EQ 5D) [Citation42]; Fear-avoidance Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) [Citation43] and Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ)[Citation44]; Risk of chronicity Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening [Citation45] or Start Back Screening Tool (STaRT) [Citation46]; Self-efficacy (self-efficacy scale) [Citation47]; Anxiety/depression [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [Citation48], Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [Citation49], Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) [Citation50], Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) [Citation51].

Open questions about PROMs included in the survey

Four open answer questions were included in the survey, whereas two are included in the present study: (i) “In what way do you find the PROMs you use helpful in assessing LBP?” (ii) “What might be the reason that you choose not to use a PROM in your assessment of LBP?” The findings from two other questions on sub-grouping will be presented elsewhere.

All answers were collected anonymously, even to the authors. Notice was given in the e-mail that answering the survey was voluntary and that, by answering the survey, informed consent to participate was given. The participants responded online between the first and last days of September 2016. Two reminders were sent out with a 1-week interval. An ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethical Committee in Stockholm (Registration no. 2016/354–31/4).

Data analysis

The outcome from the multiple-choice questions is presented with descriptive non-parametric statistics using the computer program Microsoft Office Excel 2013®. The options “always”, “very often”, “often” and “seldom”, “very seldom”, “never” were dichotomized into two categories in the data analysis: (i) used always/often (“always”, “very often”, “often”), and (ii) used seldom/never (“seldom”, “very seldom”, “never”).

The open questions were analyzed with qualitative content analysis in a manifest manner if feasible [Citation52] and otherwise with common qualitative analysis reporting frequencies [Citation53]. Answers from the open questions were first read several times to get an overall impression and then shortened into meaningful units if feasible. The units were then coded, and the codes were merged into sub-categories and categories for the open questions analyzed. All categories were exemplified with citations. The coding was carried out by the first author and then discussed in collaboration with the other authors. Codes and categories were settled when consensus was achieved among all authors.

Results

Of 4934 e-mails that were sent out, 4,843 were delivered to the e-mail addresses. The number of respondents were 1217 (25%). Thirty-one physiotherapists received and started the survey, but did not meet patients with LBP regularly and were thus excluded. Ninety-five percent (n = 1135) answering the trial met with LBP patients every day or more than once a week.

Demographics of the respondents are presented in . Thirty-three percent (n = 397) of those responding were male. The mean age of the respondents was 44 years (SD 12). Seventy-eight percent (n = 945) had worked as a physiotherapist for >5 years. Sixty-one percent of the physiotherapists had a bachelor’s degree and 22% had a postgraduate degree at master’s level. Fifty-four percent worked in public primary health care or private health care centers, and 39% worked in private settings. Eleven percent (n = 147) were advanced clinical specialists in pain management, manual therapy, sports medicine, or primary health care.

Table 1. Respondents’ demographic characteristics (n = 1217).

Respondents’ use of clinical testing

The reported usage of the clinical tests to assess LBP is presented in [palpation for pain; repeated movements according to Mechanical Diagnostics and Therapy (MDT); segmental movement of the spine; muscle length and strength; neurological tests; observation of posture; abdominal-draw-in maneuver, and movement screening]. All the aforementioned tests were used “always/often” by >60% of the respondents. The neurological test and posture was observed by almost all (99%) of the respondents. The abdominal draw-in maneuver (ADIM) while palpating for activity in the deep abdominal muscles was used “always/often” by 68%.

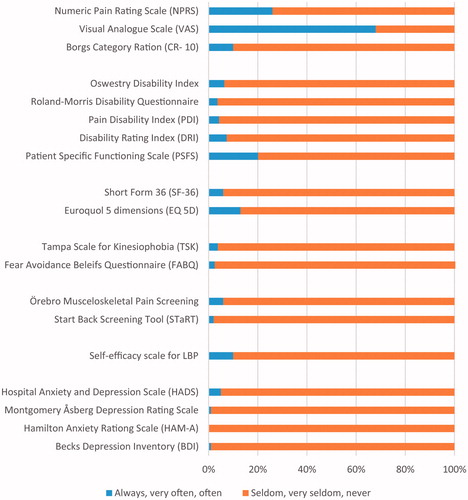

Figure 1. The respondents’ use of various clinical tests. The blue vertical pillars present “always, very often, and often” in percentage of use (0–100%).

More than 40% of the respondents examined mobility in the foot joints, pelvic joints, shoulder joints, knee joints, hip joints, thoracic spine and neck “always/often” (). The most commonly tested joints were the hip and pelvic joints and the thoracic spine.

Various tests for observing impaired movement control of the spine () were used “always/often” by <20% of the respondents.

Respondents’ use of PROMs

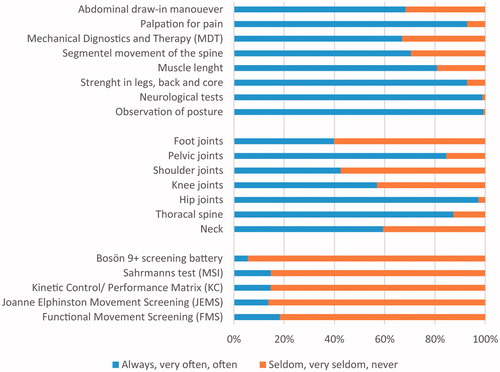

Pain

Sixty-eight percent of the respondents used Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) “always/often” (). Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) and Borg’s Category Scale (CR-10) were used “always/often” by <30% of the respondents.

Disability

shows the respondents’ use of PROMs for disability. The most frequently used PROM for disability was PSFS, which was used “always/often” by 20%. The other PROMs for disability were used “never/seldom” by >90% of the respondents.

Quality of life

The Short Form 36 (SF-36) and the Euroquol 5 dimensions (EQ 5D) for measuring quality of life were used “never/seldom” by >80% of the respondents.

Fear avoidance and self-efficacy

Fear-avoidance measured with Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) and Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) were used “never/seldom” by >90% of the respondents. Ninety percent of the respondents “never/seldom” used a PROM for self-efficacy.

Depression and anxiety

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Becks Depression Inventory (BDI) were used “never/seldom” by >90% of the respondents.

Risk and prognosis

To identify risk or prognosis of long-term LBP, >90% used “never/seldom” the PROMs Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening and Start Back Screening Tool (STaRT).

Open-ended questions

Advantages to use PROMs

Findings from the open-ended question on the advantages of using PROMs “In what way do you find the PROMs you use helpful in assessing LBP?” were analyzed with content analysis and resulted in five categories and 11 sub-categories (). Categories with examples of citations are presented in the following section.

Table 2. Advantages using PROMs (response rate n = 529).

Clinical reasoning and patient management

The PROMs were experienced as a help in the physiotherapy working process. They were used to assess and diagnose and to follow-up the progress of rehabilitation and to evaluate interventions. The PROMs were also used to capture those with so called “yellow flags” to be taken into consideration in the management. In addition, they could be used to form a treatment plan more easily, to set goals and determine what to focus on in treatment.

Capture those [patients] who show high risk of fear of movement, depression and negative views about the future

To be able to formulate a treatment plan at the right level

The quality of the assessment

The PROMs were used to achieve a clear structure during the examination process, to validate the clinical findings from the examination and to ensure the quality of the assessment so as to target treatment. Through the structure using PROMs, nothing was forgotten, and thus a good quality was achieved.

More structured, less risk that something is forgotten

For objective assessment

The patient’s view influences assessment

Using PROMs, the patient’s voice was heard, and the results of the PROMs were compared to the physiotherapists’ findings from the clinical testing in order to validate whether the clinical assessment and what the patient reported corresponded. The PROMs were also considered helpful to obtain the patients subjective experience and experience of previous episodes of pain.

The patient’s own experience is one of the base elements for how you proceed with the treatment

To get an idea of the self-reported measurements in relation to objective findings and perceived disability

Educate and motivate the patient

PROMs were also articulated to be used in an educational role with the patient, for example, to clarify to the patient what the problem is and also to discuss rehabilitation and self-management. It was also used to get the patient more involved in the rehabilitation process and for the patient to see their problem more clearly.

How much education the patient needs, pain physiology and explanation models for low back pain

Puts the patient in a position where they need to reflect on their function

Communication with other health professionals

PROMs were considered helpful when communicating with other health professionals about the patients’ condition, when, for example, giving feed-back to physicians.

To give a report to other care-givers

Investigate whether the patient needs multimodal treatment

Barriers to the use of PROMs

The answers to the question on barriers gave only short answers, thus common content analysis with frequencies was used. Findings on how the respondents experienced barriers (response rate, n = 824) while using PROMs (responses to the question “What can be the reason that you choose not to use a PROM in your assessment of LBP?”) resulted in the following four categories and 13 sub categories ().

Table 3. Categories and sub categories of regarding barriers of using PROMs (response rate n = 824).

Lack of time and knowledge

The respondents reported that they had a lack of time. For example, the lack of time to administer PROMs during the first visit was articulated. In addition, they considered that they had a lack of time to learn how to use various PROMs and to learn which specific PROMs are important to use. Furthermore, they had no routine for PROMs in their everyday practice, no education on PROMs and low overall knowledge about PROMs. The respondents also stated that patient history and/or the clinical assessment gave sufficient information, and that there was no need to use PROMs. There were statements about how they either forget to use PROMs or were not able to answer why they do not use them.

There is not enough time during the first visit to administer PROMs and the outcome of the PROM

It is hard to choose which PROM to use; there are too many and some are too complicated

Administrative aspects

The participants described several barriers, such as restrictions in the electronic journal system, which means extra administration to include PROMs. Further barriers, were that PROMs were not accessible in the clinic’s internal web system, meaning more administration and paperwork, which was not possible. The respondents also found that the routines at their work place prevent them from using PROMs, and that if a license was needed to use PROMs this would have a cost implication. It was also said that the use of PROMs is a reality for register research, but was not prioritized in the clinic. Yet another statement was that, since there is no obligation to use PROMs, they are not prioritized. Some said that other caregivers do not know these instruments and therefore do not know how to handle the result.

There is no convenient way to integrate these instruments into the journal system

No physician or other care-giver understands it [the PROMs]

Influences on the interaction between PT and patient

Language and cultural barriers were described as a barrier. It was described that PROMs in Swedish are useless for patients from other countries (e.g., for immigrants) as well as there being deficits in some patients’ cognition and understanding. Opinions were raised that PROMs might be inconvenient for the patient, and that patients might experience that their physical suffering is not taken seriously, meaning that they could feel exposed. It was also said that the patient–clinician interaction could be harmed and, that answering a PROM may not correspond to the patient’s expectations.

It [the use of PROMs] can disturb my dialogue with the patient and the patient-therapist alliance

Language barriers, memory difficulties for the patient [using the PROM]

The PROMs applicability and validity

There were arguments that the available PROMs are not applicable to the specific patients they treat, who were athletes, healthy subjects, children or patients with mild symptoms and quick recovery. It was also stated that, since PROMs in general are not reliable or valid, therefore there is no reason to use them.

There are too few objective and reliable PROMs

Not applicable to the patients I meet

Discussion

The aim with the present study was to map the current praxis of how physiotherapists in primary health care in Sweden use clinical tests and PROMs to assess patients suffering from LBP, and in addition to study the barriers, and advantages to the use of the PROMs. Our findings show that >3/5 of the physiotherapists use clinical tests “always/often”, while most PROMs were used “never/seldom” by >85%. The two most used clinical tests were observation of posture and neurological tests. The three PROMs most used were the VAS for pain, used “always/often” by almost 3/4, the NRS by ∼1/4, and the PFSF for assessing functional limitations by 1/5 of the physiotherapists.

The respondents reported a high use of clinical tests, of which several have been shown to have a low validity and reliability [Citation6–8]. For example, >65% reported that they “always/often” assessed the activity of the deep abdominal core muscles using abdominal-draw-in-maneuvres (ADIM), a test that has been shown to have a low discriminative validity, even if the reliability is reported good [Citation32]. In addition, the respondents reported the use of clinical provocation and mobility tests such as assessing segmental mobility, tests shown to have poor reliability [Citation6]. The reasons for frequently using clinical testing and not PROMs are most likely both by educational background and habits. Habits are known to be hard to change when the context is constant for longer periods, as they are in the health care culture. Thus, to achieve such a change in physiotherapists’ behavior and roles, that is to use clinical testing and PROMs, interventions that will change the physiotherapists’ context will also address the habit itself [Citation54]. In Sweden, a multi-component implementation for PROMs was evaluated for patients suffering from LBP, neck- and shoulder pain, including a 3-h education, guidelines and a website providing easy access to recommended PROMs as well as offering support and guidance. The intervention showed an increase in the use of PROMs after a 3-month period [Citation55].

In physiotherapy interventional research, outcome measures are most often not clinical tests but PROMs evaluating pain level, activity limitations, and in addition psychosocial factors, e.g., depression or fear of movement. Thus, key factors such as psychosocial factors important for the prognosis might not be captured if not using PROMs meaning that some patients might not be given a targeted treatment. Evidently there are barriers to the use of PROMs. Reported in our study were aspects of physiotherapists’ personal factors, administrative factors, and factors related to the patient–therapist interaction. For the open question on barriers, the most commonly stated barriers to not using PROMs were the physiotherapists’ lack of time and knowledge and experiencing “no additional benefits from using PROMs”. Other barriers identified were administrative aspects such as difficulties in incorporating the PROMs into the electronic journal system and interactional aspects with patients, such as language and cultural barriers and lack of appropriate PROMs. These findings concur with recent studies [Citation24,Citation56]. In keeping with our findings, a previous study among physiotherapists in Australia reported that “the time required to administer the test” and “lack of familiarity” were barriers addressed by >80% of the respondents [Citation26]. Our findings of administrative barriers such as the difficulties of including PROMs in currently used electronic journals are hitherto not reported, and are significant for modern organizations using web-based and electronic solutions in clinical practice. Nor has the idea previously been expressed that some respondents found their clinical knowledge “good enough” and thus considered PROMs not to be needed. We find that this is an interesting remark, which might be explained by the physiotherapists’ tacit knowledge based on their clinical experience [Citation57]. There were also expressions that the use of PROMs disturbed the interaction with the patient and thus the use of PROMs was negative. On the other hand, improved interaction was mentioned by others as an advantage of using PROMs. The barrier of other colleagues and employers preventing the respondents from using PROMs has only been mentioned in a previous study [Citation24], and is an organizational issue since management of PROMs is considered to take time from patients.

PROMs have in earlier studies [Citation58,Citation59] been proved useful in assisting the clinician in the clinical reasoning process, in measuring psychosocial factors and for ensuring a patient-centered treatment, which is in keeping with our findings. For instance, a low level of self-efficacy for physical activity has been shown to be an important predictor of long-term disability in LBP [Citation47,Citation60], and fear-avoidance is considered important to take into consideration for the transition of acute back pain into chronic pain [Citation59,Citation61]. In the present study, several advantages were reported to result from the use of PROMs. These advantages align with previous studies, although ours is the only study that specifically asked for the physiotherapists’ views on the advantages of using PROMs. Reported advantages were taking "yellow flags" into consideration in the clinical reasoning process, the quality of the assessment for objective assessment, and educating and motivating the patient to cause them to better understand the problem and to communicate with other health professionals. Not reported before is our finding, the use of PROMs to educate and motivate patients about their condition. This is an important knowledge, since patient education and self-management is highly recommended in the treatment of LBP, especially in those with minor pain and low disability [Citation5,Citation62].

Comparing our findings with similar studies of physiotherapists’ use of PROMs, we find that little seems to have changed regarding physiotherapists’ use of PROMs, even though the research evidence for PROMs has grown stronger over the past decade [Citation16,Citation19,Citation24,Citation26,Citation27,Citation56,Citation63,Citation64]. One might question whether the physiotherapy programs and continued education have incorporated the research within the field of PROMs and, in addition, whether the education of graduate physiotherapists is up-to-date, thus the implementation lags. How the clinical work is organized or steered also might have an impact on the use of PROMs and clinical testing.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the present study is that more than 1000 physiotherapists working in primary health care all over Sweden responded to the survey, although a limitation is the low response rate of 25%. Despite this, our findings based on the open questions might be considered as a large material for analysis of open questions with written answers. One reason for the low response rate could be that those who did not answer did not feel that they had the time to respond to a survey, meaning that lack of time would be even more clearly represented had they answered. The spread between men and women is close to the population of physiotherapists in Sweden, which in 2015 included 77% women and 23% men [Citation29].

The present study included open questions to identify advantages and barriers using PROMs. However, not everyone responded to the open questions, meaning that other barriers and advantages might exist in addition to those in our findings. A further limitation is that respondents answering a web-based survey might capture those interested in the subject, thus missing valuable information. However, the survey was piloted among 38 physiotherapists for face validity, and following this only minor change were made. An additional limitation is that the physiotherapists might have had difficulties to determine between response choices meaning that a misclassification bias is possible. We, however, choose to categorize the answers into “always/often” and “never/seldom” making the potential error negligible. Furthermore, there is always a risk of overestimation as the perceived behavior might differ from the reality, which would imply that physiotherapists in Sweden might use PROMs even less than reported. This is further reported in a previous study using a similar design as ours [Citation24].

There seems to be a significant need for translational research regarding the use of PROMs in clinical practice, considering the gap between scientific evidence based on outcome measures and their implementation in practice. This is confirmed in a study of treatment methods for musculoskeletal disorders in Sweden, which reported that several interventions used in clinic practice have unclear or no evidence of effect [Citation23].

To increase the use of PROMs on a wide scale, barriers such as the routine collection of PROMs that are not time-consuming and fears about how PROMs interfere with patients’ expectations, need to be overcome. For example, to meet the need for a more feasible PROM in primary health care, the Keele Musculoskeletal Patient Reported Outcome Measure (MSK-PROM) [Citation65] was developed for clinical practice and designed to capture six prioritized domains; while the remaining four domains are to be measured with EQ-5D. Another PROM feasible for the use in LBP is the Start Back Screening Tool, which has been cross-culturally translated and validated [Citation66,Citation67]. Despite this, our findings showed that the Start Back was used “seldom/never” by >90% of our respondents. Thus, future research needs to evaluate whether undergraduate programs as well as continued education on PROMs used in LBP would increase their use by physiotherapists in primary health care and thereby increase the health for LBP patients.

Conclusions

Our findings show that physiotherapists working in primary health care use clinical testing in low-back pain to a great extent, while various patient-reported outcome measures are used to a low-to-very-low extent. Several barriers to the use of patient-reported outcome measures were reported, such as time, knowledge and administrative issues, while important findings on advantages were to enhance the clinical reasoning process and to educate and motivate the patient. Barriers might be changed through education or organizational change-work. To enhance the use of patient-reported outcome measures and thus person-centered care in low-back pain, recommendation and education on various patient-reported outcome measures need to be advocated.

Supplemental.docx

Download MS Word (30.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all participating physiotherapists.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:968–974.

- Bury TJ, Stokes EK. A global view of direct access and patient self-referral to physical therapy: implications for the profession. Phys Ther. 2013;93:449–459.

- Delitto A, George SZ, Van Dillen LR, et al. Low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42:A1–A57.

- Balague F, Mannion AF, Pellise F, et al. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 2012;379:482–491.

- Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2075–2094.

- Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6.

- Strender LE, Sjoblom A, Sundell K, et al. Interexaminer reliability in physical examination of patients with low back pain. Spine. 1997;22:814–820.

- Rebain R, Baxter GD, McDonough S. A systematic review of the passive straight leg raising test as a diagnostic aid for low back pain (1989 to 2000). Spine. 2002;27:E388–E395.

- Roussel NA, Truijen S, De Kerf I, et al. Reliability of the assessment of lumbar range of motion and maximal isometric strength in patients with chronic low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:788–791.

- Hicks GE, Fritz JM, Delitto A, et al. Interrater reliability of clinical examination measures for identification of lumbar segmental instability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1858–1864.

- Carlsson H, Rasmussen-Barr E. Clinical screening tests for assessing movement control in non-specific low-back pain. A systematic review of intra- and inter-observer reliability studies. Man Ther. 2013;18:103–110.

- Karayannis NV, Jull GA, Hodges PW. Movement-based subgrouping in low back pain: synergy and divergence in approaches. Physiotherapy. 2016;102:159–169.

- Childs JD, Whitman JM, Pugia ML, et al. Knowledge in managing musculoskeletal conditions and educational preparation of physical therapists in the uniformed services. Mil Med. 2007;172:440–445.

- Jette D, Ardleigh K, Chandler K, et al. Decision-making ability of physical therapists: physical therapy intervention or medical referral. Phys Ther. 2006;86:1619–1629.

- Rabey M, Morgans S, Barrett C. Orthopaedic physiotherapy practitioners: surgical and radiological referral rates. Clin Governance: Intl J. 2009;14:15–19.

- Wittink H, Nicholas M, Kralik D, et al. Are we measuring what we need to measure? Clin J Pain. 2008;24:316.

- Kyte DG, Calvert M, van der Wees PJ, et al. An introduction to patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in physiotherapy. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:119–125.

- Gardner T, Refshauge K, McAuley J, et al. Patient led goal setting in chronic low back pain-What goals are important to the patient and are they aligned to what we measure? Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1035.

- Dulmen SA, WP, Staal JB, Braspenning JB, et al. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) for goalsetting and outcome measurement in primary care physiotherapy, an explorative field study. Physiotherapy. 2017;103:66–72.

- Yeomans SG, Liebenson C. Applying outcomes management to clinical practice. JNMS. 1997;5:1–14.

- Wong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: a systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Eur J Pain. 2017;21:201–216.

- Stochkendahl MJ, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J, et al. National Clinical Guidelines for non-surgical treatment of patients with recent onset low back pain or lumbar radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:60–75.

- Bernhardsson S, Oberg B, Johansson K, et al. Clinical practice in line with evidence? A survey among primary care physiotherapists in western Sweden. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21:1169–1177.

- Swinkels RA, van Peppen RP, Wittink H, et al. Current use and barriers and facilitators for implementation of standardised measures in physical therapy in the Netherlands. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:106–120.

- Stokes EK, O'Neill D. Use of outcome measures in physiotherapy practice in Ireland from 1998 to 2003 and comparison to Canadian trends. Physiother Can. 2008;60:109–116.

- Abrams D, Davidson M, Harrick J, et al. Monitoring the change: current trends in outcome measure usage in physiotherapy. Man Ther. 2006;11:46–53.

- Copeland JM, Taylor WJ, Dean SG. Factors influencing the use of outcome measures for patients with low back pain: a survey of New Zealand physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2008;88:1492–1505.

- Sheeran L, Coales P, Sparkes V. Clinical challenges of classification based targeted therapies for non-specific low back pain: What do physiotherapy practitioners and managers think? Man Ther. 2015;20:456–462.

- Swedish Association of Physiotherapists. [cited 2018 April 10]. Available from: https://www.fysioterapeuterna.se/InEnglish/

- Werneke MW, Hart D, Oliver D, et al. Prevalence of classification methods for patients with lumbar impairments using the McKenzie syndromes, pain pattern, manipulation, and stabilization clinical prediction rules. J Man Manip Ther. 2010;18:197–204.

- Kaping K, Ang BO, Rasmussen-Barr E. The abdominal drawing-in manoeuvre for detecting activity in the deep abdominal muscles: Is this clinical tool reliable and valid? BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008711.

- Luomajoki H, Kool J, de Bruin ED, et al. Reliability of movement control tests in the lumbar spine. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:90.

- Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:17–24.

- Stubbs DF. Visual analogue scales. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;7:124.

- Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377–81.

- Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine. 2000;25:2940–2952; discussion 52.

- Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine. 1983;8:141–144.

- Chibnall JT, Tait RC. The Pain Disability Index: factor structure and normative data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:1082–1086.

- Salen BA, Spangfort EV, Nygren AL, et al. The Disability Rating Index: an instrument for the assessment of disability in clinical settings. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1423–1435.

- Stratford P, Solomon P, Binkley J, et al. Sensitivity of Sickness Impact Profile items to measure change over time in a low-back pain patient group. Spine. 1993;18:1723–1727.

- Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305:160–164.

- Brooks RG, Jendteg S, Lindgren B, et al. EuroQol: health-related quality of life measurement. Results of the Swedish questionnaire exercise. Health Policy. 1991;18:37–48.

- Roelofs J, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH, et al. Fear of movement and (re)injury in chronic musculoskeletal pain: evidence for an invariant two-factor model of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia across pain diagnoses and Dutch, Swedish, and Canadian samples. Pain. 2007;131:181–190.

- Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, et al. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52:157–168.

- Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: the predictive validity of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:80–86.

- Forsbrand M, Grahn B, Hill JC, et al. Comparison of the Swedish STarT Back Screening Tool and the Short Form of the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire in patients with acute or subacute back and neck pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:89.

- Denison E, Asenlof P, Lindberg P. Self-efficacy, fear avoidance, and pain intensity as predictors of disability in subacute and chronic musculoskeletal pain patients in primary health care. Pain. 2004;111:245–252.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370.

- Soron TR. Validation of Bangla Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRSB). Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;28:41–46.

- Maier W, Buller R, Philipp M, et al. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 1988;14:618.

- Alic A, Pranjic N, Selmanovic S, et al. Screening for depression patients in family medicine. Med Arch. 2014;68:37–40.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis – an introduction to its methodology. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: The Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania; 2012.

- Nilsen P, Roback K, Brostrom A, et al. Creatures of habit: accounting for the role of habit in implementation research on clinical behaviour change. Implementation Sci. 2012;7:53.

- Kall I, Larsson ME, Bernhardsson S. Use of outcome measures improved after a tailored implementation in primary care physiotherapy: a prospective, controlled study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22:668–676.

- Davies C, Nitz AJ, Mattacola CG, et al. Practice patterns when treating patients with low back pain: a survey of physical therapists. Physiother Theory Pract. 2014;30:399–408.

- Darrah J, Loomis J, Manns P, et al. Role of conceptual models in a physical therapy curriculum: application of an integrated model of theory, research, and clinical practice. Physiother Theory Pract. 2006;22:239–250.

- Fritz JM, Delitto A, Erhard RE. Comparison of classification-based physical therapy with therapy based on clinical practice guidelines for patients with acute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2003;28:1363–1371.

- Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Weiser S, et al. The role of fear avoidance beliefs as a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2014;14:816–836.

- Rasmussen-Barr E, Campello M, Arvidsson I, et al. Factors predicting clinical outcome 12 and 36 months after an exercise intervention for recurrent low-back pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:136–144.

- Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U, et al. Fear-avoidance beliefs-a moderator of treatment efficacy in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2014;14:2658–2678.

- Hill JC, Dunn KM, Lewis M, et al. A primary care back pain screening tool: identifying patient subgroups for initial treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:632–641.

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9–19.

- Kay TM, Myers AM, Huijbregts MPJ. How far have we come since 1992 A comparative survey of physiotherapists' use of outcome measures. Physiother Can. 2001;53:268–275.

- Hill JC, Thomas E, Hill S, et al. Development and Validation of the Keele Musculoskeletal Patient Reported Outcome Measure (MSK-PROM). PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124557.

- Hill JC, Dunn KM, Main CJ, et al. Subgrouping low back pain: a comparison of the STarT Back Tool with the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:83–89.

- Betten C, Sandell C, Hill JC, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Swedish STarT Back Screening Tool. Eur J Physiother. 2015;17:29–36.