Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to provide a description of the learning environment at Folk High School for participants with high-functioning autism and to examine their learning experience at Folk High School.

Methods

A qualitative interview study was conducted with 21 participants who were enrolled at Folk High School which had been adapted to suit young adults with high-functioning autism. The interviews were analysed by means of a thematic content analysis which resulted in the identification of 6 themes related to learning experiences at Folk High School.

Results

The participants enjoyed themselves and felt secure at Folk High School. They felt that they and their academic endeavours were suitably recognised, acknowledged, and understood. They reported that the teaching was suitably adapted for them and they felt that they could succeed in their studies. A frequent report that they made concerned their experience of clear structures in the teaching process and its predictability. The participants stated that Folk High School has the ability to satisfy each participant’s needs, which entailed lower levels of perceived stress than what they had experienced in their previous schooling. The participants experienced personal development during their time at Folk High School.

Conclusions

Folk High School, and its special character, is able to successfully satisfy the needs of participants with high-functioning autism. Many of the participants, for the first time in their lives, experienced a sense of inclusion in an educational system and felt that they could succeed in their studies. However, there exists a risk that they become institutionalised, which entails that the participants function well primarily in Folk High School’s safe and caring environment.

A supportive environment including both formal and social learning is paramount for people with high-functioning autism.

Individually adapted teaching that is structured and predictable improve the conditions under which they can focus on their studies and enjoy academic success.

The teachers’ relational competence and ability to show interest in each individual are crucial.

Social- and special-pedagogic competencies need to co-exist so as to improve learning conditions.

Internship/workplace training can provide an important social learning experience for participants, as they learn about themselves and others and as they develop their social competence.

To practice living on one’s own is a significant challenge, but it can create opportunities to learn about one’s self and to develop a sense of responsibility and other social skills.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

From an international perspective, the situation in which people who suffer from different functional impairments find themselves has worsened in several areas during the twenty first century, with increasing levels of exclusion and discrimination as a result of this. This is apparent in the school system, as well as in the healthcare system and in the labour market [Citation1–4]. In Sweden, this trend has followed a similar path with the creation of an increasingly difficult situation for this group of people [Citation5–8]. The present study is focused on people with high-functioning autism and their academic endeavours at Folk High School. Folk High School is a Scandinavian education system for adults which has been said to have a special character since social- and meaningful dimensions are included in its approach [Citation9,Citation10]. One difficulty that people with high-functioning autism face is to function and be accepted at school. Consequently, the high school drop-out rates for this group of people is significantly higher than the average, in Sweden [Citation11]. The difficulties that arise at school are often caused by a lack of adaptations, bullying, and exclusion [Citation12–14]. The purpose of this article is to provide a description of how Folk High School functions as a learning environment for participants with high-functioning autism and to also report on the experiences that they have of their studies at Folk High School.

The special character of the Swedish Folk High School system

Today, Sweden has 154 Folk High Schools with approximately 100 000 participants per year who are engaged in different educational courses. The most common courses are general and correspond to courses at the upper secondary school. These courses are for participants who previously failed in upper secondary school. Most Folk High Schools also offer specialized courses that often focus on aesthetic content, or are vocational courses, that correspond to university education. In addition, special courses are also offered for newly arrived refugees, people with impairments; and for senior citizens. The Folk High School is fifty percent funded by government grants and the remainder is funded in various ways, mostly by organizations, foundations and municipalities [Citation15]. The Folk High School system, which is an important part of the Folk education movement in Sweden, has been described as having a special character, in contrast with the rest of the Swedish educational system [Citation9,Citation10]. This special character is a function of the social- and meaningful dimensions of the Folk High School system. This is a result of the holistic view taken of people and knowledge which is related to a person’s whole life-situation. Personal development and an individual’s experience of what is meaningful are central tenets to this approach. The term that is used to refer to those individuals who study at Folk High School is participant, which is quite different from the rest of the education system. The term, participant, indicates that Folk High School’s values are based on freedom and voluntariness, where participants, via inter-personal interaction, are viewed as co-creators of processes which are informed by the notion that everyone is equal [Citation9]. Folk High School also has a long tradition of arranging courses which are aimed at including people and contributing to the bildung of people who have different needs, for example, people with impaired functional abilities [Citation16]. According to Skogman [Citation17] and Nylander [Citation18], Folk High School is characterised by an openness and accessibility which facilitates this particular group of participant’s studies. In 2016, the Folk High School directorate decided on a new grant system for Folk High School, which was put into place on 1 June 2017. One of the grants on offer, a support grant, is specially aimed at supporting pedagogic input for participants with impaired functional abilities [Citation19]. This support grant is based on a relational perspective regarding functional impairments where:

[…] these [impairments] are considered in relation to the environment – problems first arise in the interaction between people with impaired functional abilities and the environment. In such a perspective, different measures can be seen as ways of changing the environment with the goal of preventing any problems from arising. [Citation19,p.2]

The existing conditions for providing inclusive education are thus considered to be good for Folk High School. But how are they implemented? Previous research on Folk High School in general and its work aimed at participants with high-functioning autism is particularly thin on the ground [Citation20], which is why the present study can contribute to the field with valuable knowledge about Folk High School as an educational system and how this system is experienced by participants with high-functioning autism.

The Swedish Folk High School and participants with impaired functional abilities

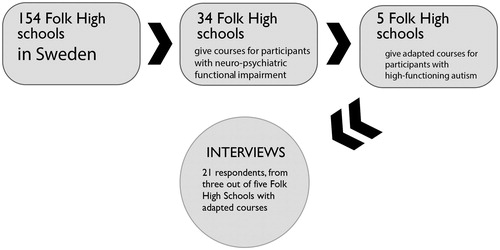

The proportion of participants with impaired functional abilities at Folk High School has increased during the beginning of the twenty-first century. Currently, the largest participant group who makes use of the support grant are participants who have some form of neuro-psychiatric functional impairment [Citation20]. High-functioning autism is subsumed under this category. 33% of participants who are enrolled in general courses (corresponds to upper secondary school) have some form of functional impairment, whilst for the specialized courses that have aesthetic content, or are vocational courses (corresponds to university), the corresponding proportion is 13%. Furthermore, Folk High School offers 34 educational courses which are exclusively adapted for participants with functional impairment, 5 of which are aimed at young adults with high-functioning autism [Citation15]. In the present study, these 5 courses which are aimed at young adults with high-functioning autism form the basis of our investigation.

High-functioning autism

High-functioning autism is one of several neuro-psychiatric functional impairments. People who are diagnosed with such are described as having limitations in the areas of social cognition [Citation21–30] and empathy [Citation31–35]. Research has also identified a lack of enterprise and an inability to take the initiative amongst people who have been diagnosed with high-functioning autism [Citation36,Citation37], as well as a limited ability to make plans and to be flexible [Citation24]. This research, however, has been challenged by studies that claim that poor results on all sorts of tests can be attributed to difficulties in understanding what psychiatrists and researchers expect from the high-functioning autistic subject, instead of any specific cognitive impairment(s) [Citation38]. Moreover, other studies suggest that several of the impairments are expressions of normopathy rather than symptoms [Citation39]. Notwithstanding this observation, the medical paradigm has a great deal of influence in this regard, and, as a consequence, it is the impaired abilities which are most frequently remarked upon for people who have been diagnosed with high-functioning autism [Citation40].

A proper understanding of these impaired abilities is, of course, crucial to being able to provide adequate support for people who have been diagnosed with high-functioning autism. The individual focus on impairment in the diagnosis period can be supplemented, to good effect, with a relational focus concerning designing support structures for the individual in question. This point is raised, as previously mentioned, by the Folkbildningsrådet [Citation19] [The Swedish National Council of Adult Education] with respect to support grants for Folk High School participants. We note that even in the Swedish Equality Act [Citation41] and the Socialstyrelsen [Citation42] [The National Board of Health and Welfare] emphasise the fact that the environment is a significant factor as to whether a functional impairment is an obstacle for the individual or not. Consequently, we view functional impairment as something dynamic which is made manifest in the interaction between people and their environment, which entails that the environment itself can be impairing. Such a perspective also has implications for support measures. Primarily, it is the environment in the form of norms and attitudes in society, and the physical environment, which needs adjustment so as to be inclusive, supportive, and not pose itself as an impairment [Citation43]. In practical terms, this may entail offering support during- and outside the teaching process by means of social-pedagogic- and special-educational needs measures [Citation44].

In previous research, the opportunity to be able to study alone at one’s own designated study cubicle, to focus on one task at a time, and to enjoy the freedom to decide over one’s time has been shown to be of great import to the success of the academic endeavours of young people with high-functioning autism [Citation45,Citation46]. In addition to formal learning experiences linked to subject content, informal learning experiences also take place. This informal learning has been previously described as being of importance to people with high-functioning autism since it can contain valuable aspects complementary to formal learning experiences linked to subject content [Citation12–14]. Such experiences can include social skills – social learning, which are of particular importance to people with high-functioning autism [Citation21–24]. Previous research [Citation45,Citation46] has also shown the importance of social learning and the opportunities that it provides for people with high-functioning autism, since it allows them to develop the ability to create social relationships and networks, and gives them the courage to ask for help and to speak in front of groups of people. Social learning can also be linked to formal learning and thereby constitute a teaching subject which can be given complementary to more informal social learning experiences. For example, there are three general Folk High School courses which are aimed at people with high-functioning autism. The purpose of these courses is to offer participants course content which will help them to better understand themselves, to deal with day-to-day issues, and to develop socially. Furthermore, there exists a Folk High School course that prepares participants for a career pathway and for independent living. This course is aimed at getting participants to develop suitable skills that will allow them to fit into the labour market and successfully live on their own (www.folkhogskola.nu).

Social learning experiences are central to a specific method of rehabilitation/habilitation which has shown itself to be effective for people who have been diagnosed with high-functioning autism; namely, Supported Education [Citation47,Citation48]. The ambition behind this method is to increase the self-knowledge of students/participants by focusing on informal- and social learning [Citation49,Citation50]. Previous research has shown that Supported Education can lead to increased self-knowledge and self-reliance and improved study results [Citation51–54]. Despite the fact that not all educational courses which are aimed at people with high-functioning autism are given in accordance with the principles of Supported Education, it has been shown that they can have clear and distinct rehabilitation- and habilitation effects [Citation45,Citation46].

The importance of social learning for people with high-functioning autism is thus quite wide-ranging. We thus ask: How can Folk High School, with its focus on social- and meaningful dimensions [Citation9], provide social learning experiences which, in turn, will improve the opportunities for people with high-functioning autism to succeed in their academic endeavours?

Method

Procedure

This study was initiated so as to investigate the existence of Folk High Schools which provide educational courses for people with neuro-psychiatric functional impairments. 34 schools were identified, of which five provided specific courses for participants with high-functioning autism. Three of these five schools were selected, and 21 interviews were conducted at these schools during the autumn of 2017. The three Folk High Schools that were selected offered several educational courses for participants with high-functioning autism. These included a general educational course that had been adapted for participants with high-functioning autism (corresponds to upper secondary school), a “regular” general educational course where participants with high-functioning autism studying together with participants without impairment (also corresponds to upper secondary school), and special courses which focus on independent living, work-life, and social competence. The criteria for attending such a course is that you are diagnosed with high-functioning autism. In total, five different courses were included in this study, of which two were general courses (one adapted and one “regular”) and three were special, preparatory courses for a career pathway and independent living ().

Two researchers visited each Folk High School two full days and conducted the interviews individually. All of the interviews consisted of semi-structured life-world interviews [Citation55] and covered a number of question areas regarding experiences of Folk High School studies, such as experiences of teachers, teaching and learning as well as coping with living by themselves at the school. An interview guide was used during the interviews, but, notwithstanding this, the interviews were relatively open interviews, which meant that the respondents’ narratives gave partial direction to the content of the interviews. The individual research interviews lasted between 23 and 80 min each. All of the interviews were transcribed. In order to secure the validation of the content in the interviews, the researchers conducted two focus group discussions about the findings, one with the participants and one with the teachers.

Participants

All of the participants who were interviewed were young adults who had been diagnosed with high-functioning autism, between the ages of 18–28 years. Sixteen of the participants were male and five were female. During our visits to the Folk High Schools, we asked all the participants aged between 18 and 29 to take part in the interview study and of the 36 participants, 21 agreed. The average age of the participants in the study is 21.5 years and the average duration time at the Folk High School is 18 months. provides an overview of the participants, including their background and previous experience.

Table 1. Overview of the participant characteristics and experiences.

Analysis

We employed a qualitative content analysis [Citation56] with the aim to identify overarching themes concerning how Folk High School functions as a learning environment for participants with high-functioning autism and to report on the experiences these participants have had during their studies at Folk High School. The interviews focused on the latent abstraction level, meaning an interpretation of the content [Citation57], in order to capture a condensed but broad description of the participants’ experiences [Citation58]. The analysis was carried out in three steps that were inspired by Creswell [Citation59], Larsen [Citation60], and Tesch [Citation61]. The interviews were first transcribed, followed by a careful reading of all interview transcriptions. The reading gave an overview and some insight into the material. Some of the descriptions were shared by the majority of the respondents while some were unique. Thereafter, the material was encoded by keywords and phrases. Lastly, the material was read through once again and content categories were created based on the keywords.

Concerning the learning environment, our analysis was primarily directed towards its content with respect to teaching, the teachers, the course content, and other issues which were more formal in character. Two themes that were linked to the learning environment were identified: (i) Teachers who See, Confirm, and Understand the Individual and (ii) Individualised Teaching with Structure and Predictability. These two themes focus primarily on relationships and activities that take place in the classroom itself.

Concerning the participants’ experience of studying and learning, informal aspects were primarily highlighted in the analysis, including time spent outside the classroom and relationships with other participants and school staff. Four themes were identified with respect to the participants’ experience of studying and learning: (i) A Safe and Caring Environment; (ii) Good Support Functions at Folk High School; (iii) Internship and Contacts with Working-life and the Surrounding Society; and (iv) Living by themselves at Folk High School is an Important Learning Experience. These four themes focus primarily on relationships and activities that take place outside the classroom, but which help to create the conditions for teaching.

Ethical considerations

The participants were informed about the purpose of the study and gave their consent to be included in the study. The respondents’ right to privacy meant that they were treated and described confidentially. In summary, we have followed the ethical requirements of the Humanities and Social Sciences [Citation62,Citation63].

Results

Of the participants who were interviewed (n = 21), 19 of them reported that they were happy studying at Folk High School, and two-thirds of the participants reported during the interviews that they had been enrolled at Folk High School for more than one year. The two participants who stated that that they were not happy at Folk High School had given up and reported that nothing in life made them happy. These two individuals had felt depressed for a long period and said that their attendance at Folk High School had nothing to do with how they felt:

It has been quite educational, I think… but at the same time I have had my personal problems with coming to the courses… with sleep and stuff […] I have had trouble with sleep for quite a long time… I have eaten this kind of sleep medication for a long time […] I probably get as much support as I can get here… the problem is that I have become pretty tired of everything… so my desire to do something is not very strong anymore […] What is my biggest problem is that I do not want something special with my life … I have no ambitions […] It was my parents who wanted me to be a little more independent and move here but I still don’t feel ready to move away from home. (D10)

Two prominent themes which emerged in the participants’ descriptions of their interaction with Folk High School in conjunction with the teaching and learning environment were: (i) Teachers who See, Confirm, and Understand the Individual and (ii) Individualised Teaching with Structure and Predictability. The themes which emerged in conjunction with discussions of their experience of studying and attending Folk High School in general were (i) A Safe and Caring Environment; (ii) Good Support Functions at Folk High School; (iii) Internship and Contacts with Working-life and the Surrounding Society; and (iv) Living by themselves at Folk High School is an Important Learning Experience. These themes are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Teachers who see, confirm, and understand the individual

All of the participants reported that they enjoyed positive and close interpersonal relationships with their teachers at Folk High School. In these trusting relationships, the participants felt that they were seen, confirmed, and understood by their teachers. Most prominent was the notion that they were understood by their teachers at Folk High School:

The teachers are nice and I feel that I am accepted and understood […] We have a good relationship with each other … perhaps we don’t chat very much with each other but we accept each other and acknowledge each other … no-one is alienated or attacked in any way. We understand each other … perhaps we don’t agree with each other, but we understand. (D6)

The fact that the teachers understand the participants entails, according to the participants, that the teachers can provide explanations during their lessons in a way that the participants can understand:

They are very knowledgeable teachers … the courses are adapted according to [one’s] diagnosis […] Very nice teachers and they are very understanding, for example, if I don’t understand something, then they can explain in a way that you do understand. (D2)

Many of the participants reported on their experience of this type of student-teacher relationship as being quite different from what they had experienced in previous educational settings. At Folk High School, the participants claimed that the teachers cared about them as people, not just as students assigned to different subjects:

I think that they care a lot … previously, it was like, in high school, the teachers just cared about their subject … here, I think that they care about much more […] They are much more personable here at Folk High School and so I think it is easier. It feels better because of this. (D18)

We thus observe that the teachers’ relational competence is highlighted as something of importance. The fact that they have the ability to show interest in each and every individual, (and not just for the subject matter being taught), was experienced as something both unusual and positive, and, of course, facilitated the delivery of individually-adapted teaching and learning experiences. Furthermore, it was felt that a suitable amount of structure and predictability was provided to each participant.

Individualized teaching with structure and predictability

Eleven of the participants reported that it was the first time that they had been provided with supported teaching which was adapted according to their individual needs and abilities. They felt that these adaptations allowed them to succeed in their educational endeavours. The participants also reported that they felt less stressed about their work than previously, thanks to Folk High School’s ability to interact in a positive way with every individual and as a result of being able to take extended time to complete their courses. Most of the participants who were included in this study follow an adapted course timetable which includes a smaller number of courses per study session than is typical and which allows them to complete a course before they proceed with the next. What is most apparent in this system is that it has a very clear structure, with defined limits and clearly formulated assignments. This was considered to be important for the participants and their academic success:

When I went to regular school, I found it difficult sometimes to start my assignments … but here [at Folk High School] I think that the instructions are clear … I understand the assignment immediately. (D4)

When things work best for me … it’s when … “This is what we are going to do” … you know, there is a clear assignment and it is clearly explained what the assignment is and how much. I don’t like to get, like, a countdown to a deadline … because this stresses me out. I want to have a clear ending. […] It feels like a very clear arrangement and this is really good for me. (D5)

Another clear structural element in the teaching which is important to many of the participants is made apparent in their discussion sessions. Everyone is allowed to speak, according to their turn (which the participants know about beforehand), so they can prepare themselves for it:

I feel assured that we take turns … the teachers are quite good at this … so everyone gets to say what they feel and think about, you know. I have always found it a bit difficult to be someone who can get my opinion across. (D7)

Predictability is a very important condition for the majority of the participants. Knowing exactly what is going to happen during a lesson, during the school day, and during the school week, entails for the participants less stress and worry about unforeseen events:

On Mondays during the first hour on the timetable, they explain what will take place during the week and what you should be thinking about … sometimes there are after-school activities which they tell us about […] It’s quite nice to know what is going to happen during the week … quite nice to know what will happen. If we did not have weekly-planning, then one would be quite stressed out. It’s quite nice to have weekly-planning instead of being shocked every time … oh dear, something new is happening today … oh again now, and now once more. The one gets stressed because of this […] and every lesson that we have, they set out what the lesson will be like […] that is a very good thing, I think. Then after two hours, then it is time for food. One also gets to know about the menu … what food is served. Then you know … ah, I can eat this food today. Then you can start to focus on eating supper at night. (D16)

Folk High School offers learning experiences that are characterised by being individually-adapted, structured, and predictable, which provide participants the opportunity to experience a sense of assurance. This sense of assurance allows the participants to really focus on their studies and gives them the opportunity to succeed.

A safe and caring environment

Half of the participants in this study had experienced a sense of insecurity in their previous school attendance. Nine of the participants reported that they had been socially excluded and bullied, for long periods of time, at primary and lower-secondary school and at high school. Their interaction with Folk High School and their attendance at the school is described as quite a different experience. All of the participants reported that Folk High School is a safe and caring environment, where none of them had experienced any insults or felt socially excluded:

It feels like everyone is really open to each other’s needs … really interested in each other … I feel secure with everyone … it’s not like you feel left outside or that anyone is nasty, and there have never been any conflicts at all in class. There has been a very calm atmosphere. (D4)

At folk High School, many informal meetings take place in every-day situations between participants, but also between participants and all of the staff who work there. Participants eat breakfast, lunch, and take coffee breaks together with their teachers and other staff in Folk High School’s dining room. These informal meetings and every-day situations contribute, in various ways, to creating positive experiences for participants:

It feels nice in some way … like I knew everyone after the first week already. It feels like a community in some way. And I have an understanding for other people’s weaknesses and others have an understanding of my weaknesses. So I dare to be more open. This is a very positive thing for me. (D8)

This is the best school that I have ever attended. […] I live here to start with. I am really close by to all the lessons I attend. Then there is such a context that you are part of when you live here. It is like one family. (D17)

The Folk High School environment was often described in the interviews in terms of a community, where everyone was like a big family. A family where participants found themselves in a context that is characterised by “understanding” and a sense of “caring for each other”.

Good support functions at Folk High School

All of the participants included in this study claimed that Folk High School offers good support functions, both during lessons and outside the classroom. Important support functions outside the classroom that were mentioned include, for example, social-needs teachers, living-support assistants, personal assistants, and special needs teachers. One participant reported:

They come round and remind me about reality … I am not really good at cooking either, so I need a great deal of help and that support is here. (D10)

With respect to support needs, most frequent was getting help for the participant’s daily routine; getting out of bed in the morning and being on time. Many participants stated that the lessons, in themselves, were not a problem. However, getting to class on time had been a considerable problem for them. Consider the following three participants’ description of how they had received help in this area from Folk High School:

They call me on the phone like hell … chase me up … one teacher called me now, you know, 5 minutes before I came here. (D8)

The biggest problem I have is getting out of bed in the morning and going to bed at night, and I get help with this. (D9)

The biggest support I need in my studies is getting myself off to my lessons. This is the biggest problem I have had in all of my schooling. Getting there on time and actually leaving to go to class. Before, I had never felt any good at school, before I came here. When I actually came here [to Folk High School], then I started to work … I have no problem with this … you just have to get here in the morning … but if I just get here then it works. […] Before, if I woke up late, then I did not dare go to class because I didn’t want everyone to look at me. I felt really bad about that. […] Now, I have someone who sends me messages … if it is past nine, then I get a message about that. (D17)

The social-pedagogic competence (remarked on above) that exists at Folk High School is thus considered to be very important by the participants. This competence is represented by several areas of responsibility at Folk High School and is a primary force which creates the conditions for formal learning, by ensuring that the participants actually attend class.

Internships and contacts with working-life and the surrounding society

The development of social skills and the provision of the necessary tools to participants so that they can deal with and understand their diagnosis and its consequences are important features of all of the educational courses that were included in this study. The internship gave the participants the opportunity to meet people in organizations and authorities and act as ambassadors for young adults with high functioning autism. In the careers preparatory course, we find that greater focus is directed at dealing with work-life and the expectations and demands that are placed on people in a professional setting. The participants’ experiences of how Folk High School prepares them for work-life and the surrounding society varied. This is partly a function of the fact that they were enrolled in different educational courses with different goals and purposes, and partly because the participants had different levels of motivation to work outside the safe environment found at Folk High School. Two of the participants described how they practice at functioning in society in the following:

We go out on trips together to different places, and the purpose of this I think, is so that you become more social … that is to be able to mix with people and still feel secure. Then you can go out and go bowling and swimming and then you are with other people. (D11)

Many of the participants reported on how they prepare themselves for work-life together in different courses at Folk High School:

They helps us out in our work-life … before, I had difficulty in entering the work-life […] They help us … we practice and we talk about work, and such, and how it is to do work. (D1)

We learn about what Asperger entails and we prepare ourselves for work-life. Despite the fact that I probably won’t work “for real” for the next couple of years. (D3)

Some participants reported that they prepare themselves for the internship that will take place during their studies:

We are going to do an internship in five weeks’ time. And then you have to attend and find something that you want to work with. I can be at a place where I can work with people. […] And this feels good because you are prepared and not just thrown out, and you can get supervision at the start. (D4)

We are going have five weeks of internship this spring. Amongst other things, we will practice doing job interviews so that we are used to the type of questions which are asked, and we will make our CVs and everything possible to prepare us to secure a job. (D5)

The development of social skills also takes place when the participants leave Folk High School and get to meet strangers in different contexts and also during their internships. Even if it is the case that the purposes behind these two activities are slightly different, they both make social learning possible; something which is of importance to the participants’ self-understanding and their understanding of others and of importance to the development of their social competence, thereby increasing their employability.

Living by themselves at Folk High School is an important learning experience for participants

Twelve of the participants who were interviewed live at their respective Folk High Schools. For all of these individuals, this was the first time in their lives where they had their own living quarters. Moving away from home and having one’s own living quarters at Folk High School appeared to be a learning experience equal to the actual academic courses that they read at the school. This is described as a large step in their lives:

This has been a huge change … I had taken my time to move out from home … this is, of course, the first time I have been away from my parents … this has been a huge change. (D7)

It feels good … but in the beginning, I was really nervous because I was in a new place and should go to sleep … but it all worked out later. (D11)

One of the participants described a sense of freedom associated with leaving home at last:

It was really nice to get away from my parents. Really nice, to get away from the room in which I had lived for my whole life, where I had so many really bad memories and all types of possible shit. So nice! […] It was so good; I felt so free. (D7)

Learning to live on one’s own and to manage one’s household was described as an important learning experience:

I cook and wash my clothes and so on … kinda independent. I assume that this is important. [laughs] (D3)

Things are fine … but it is not super-easy to keep things in order … it doesn’t come naturally … so I have to work a bit more on it. (D5)

Now I am better at frying meat … this was difficult for me before, because I didn’t know when to stop. (D17)

What was quite apparent during the interviews was that their stay at Folk High School had contributed to their personal development, with a strong sense of self-reliance and improved self-knowledge. The participants related how this had had a positive effect on them:

My social skills have improved greatly since I started … one example is the fact that the time I spend playing computer games has decreased significantly. Before I started here, I was very withdrawn … I did not speak with my peers, except for people on the internet. Now I am much more sociable and I talk. (D13)

This has meant a great deal to me … I have learnt to know about my self in a way which I did not previously. (D2)

When I came here … things were completely different. I am in my third year now and I feel that I have grown as a person … things are going much better for me now. (D18)

Living on one’s own is a big challenge for the participants, but it is also an opportunity for them to learn about their selves and to develop a sense of responsibility and a range of social skills. The participants’ personal development, across several different areas of their lives, contributes to the creation of conditions conducive to their formal learning.

Discussion

The purpose of this article is to provide a description of how Folk High School functions as a learning environment for participants with high-functioning autism and to survey the experiences that they have regarding their studies at Folk High School. What is quite apparent in the results of our investigation is that participants experience their time at Folk High School as something very positive. The results show that the participants thrive at Folk High School since they feel safe and they feel that they are active participants. They also report that the teaching is adapted to them and that they feel that they can succeed with their academic endeavours. These observations can be compared with previous research which has described that the difficulties which are experienced by these individuals at the primary-, lower-secondary-, and high school levels are often caused by issues of exclusion, bullying, and a lack of adaptations to suit these individuals [Citation12–14]. At Folk High School, the individual adaptations made with respect to the provision of clear structures and predictability are significant. The participants feel that they are seen (taken notice of), confirmed, and understood by their teachers and the rest of the staff at Folk High School. Folk High School is described as possessing the ability to interact with every person on an individual basis, which results in less stress for the participants in comparison with their previous encounters with the education system. Support functions outside the classroom were also reported on as being important by the participants. Many of the participants remarked on a personal development with a strong sense of self-knowledge and increased levels of self-reliance during their stay at Folk High School (cf. the aims associated with Supported Education [Citation47–54]).

One important aspect of the positive image presented by the participants’ description of their studies at Folk High School that we should take into account is the fact that the participants were (obviously) older than they were when they attended earlier stages of their schooling. Note too that Folk High School is a form of education which is completely voluntary, and that the participants choose the courses which they wish to follow themselves. If there were any participants who had less positive experiences of Folk High School, it seems that they were not enrolled at the schools we visited during the course of our interviews. This point was not raised during any of the interviews, but it is an important observation to be made.

In the following section, we discuss the results of this study in terms of four over-arching aspects which can shed further light on the fact that the participants were so uniformly positive about their studies at Folk High School.

Participant-centred teaching

The courses offered by Folk High School for participants with high-functioning autism are more based on the participants’ needs and abilities than on subject content. Central to the teaching that is provided is a form of participation that is focused on the learning individual, not on the subject. This point can be linked to Folk High School’s special character [Citation9,Citation10] and its social- and meaningful dimensions which are based on a holistic view where knowledge is related to a person’s whole life-situation. The participants’ descriptions highlighted the point that the teaching at Folk High School is provided by teachers who see, confirm, and understand each individual. The fact that the teaching is participant-centred also entails that the participants have the opportunity to work at their own pace, and are not subject to the stress of having to complete a certain assignment within a set time-frame, as it was in the earlier stages of their schooling. Consequently, it is often the case that these participants take more time than the others to complete certain courses of study. They need a “changeover period” [Citation64] each time they complete one activity and move on to another before they are fully engaged in their studies. Whilst it may be the case that people with high-functioning autism are sometimes characterised as lacking flexibility [Citation24] and lack an enterprising spirit and an ability to take the initiative [Citation36,Citation37], Folk High School’s ability to interact with each participant on an individual level and to provide then with the necessary changeover period may be a contributing factor to the fact that participants feel less stress than during their previous schooling.

Social education/pedagogy and special education/pedagogy in a symbiosis that provides the conditions for learning

According to Skogman [Citation17] and Nylander [Citation18], Folk High School is characterised by an openness and accessibility which facilitates the academic endeavours of participants who have impairments. The participants included in our study described the teaching that takes place as accessible and adapted to suit their needs. The most obvious adaptations dealt with structure and clarity. It was highlighted during the interviews that Folk High School, to a large extent, lives up to the intentions behind the support grant in terms of deploying a relational perspective in a context where measures are taken to change the environment and to work pro-actively, before problems arise [Citation19,Citation43]. We observed two parts of the adaptations that have been made: the first part consists of what is done by the subject teachers during their classroom teaching, and the second part is made manifest in the support functions that are provided outside the classroom, but which, in turn, make teaching possible. The adaptations that are made by the teachers in their classroom teaching can be described as “special education” and the support that is provided outside the classroom can be described as “social education” [Citation44]. We observed that the teachers who taught the adapted educational courses at the schools that we visited possessed a high degree of special education competence, especially since the participants felt that they were understood by their teachers. In addition to this, a special education teacher was available at Folk High School who could provide individual academic support to participants. The social education support that was present at Folk High School was represented in the form of specialised social education teachers, assistants, and living-support assistants. The social education teachers often participated in the classroom teaching and thus became a bridge between the participants’ living conditions, their studies, and their free time. Many of the participants included in this study reported that they experienced great difficulty (i) in getting out of bed in the morning and (ii) in following a normal daily routine. The participants stated that they received valuable help for these issues from the social education teachers and their living-support assistants. We claim that the support functions provided by the social education teachers and the subject teachers’ relational special education practices are just as important for the participants, and we suggest that they are woven together in a symbiotic relationship with each other, thereby providing the participants good conditions for learning. It should be possible for the Folk High School to gradually raise the demands so that the challenges of living on one’s own can successively shift to a greater focus on the studies.

Implications for practice

We perceive that there exists a risk of the participants becoming institutionalised, according to the interviews that we conducted. The participant’s lives and their academic endeavours are reported to work well at Folk High School, and we note that there is almost a plethora of support functions available to the participants; including social education teachers, living-support assistants, a curator, teaching assistants, a psychologist, and a study- and careers guidance councillor. These professionals are easily accessible at the location where many of the participants live. Things work so smoothly, are nice, and taken care of at Folk High School that some participants remain there for up till six years. Notwithstanding this, many participants are in need of step-by-step training if they are to manage the social demands that most people are subject to outside the walls of the Folk High School system, for example, at the workplace or during university studies (if these are to be pursued). Many participants find it particularly difficult to satisfy social demands such as getting up on time in the morning, being punctual, or taking oneself to class. It is not a reasonable state of affairs that, after several years of attendance at Folk High School, the participants are still dependent on social education teachers and other teacher having to continually “chase after” them if they are to be on time for their classes. Note that this is a completely unreasonable demand to place on a potential employer or university lecturer in the future. However, the participants have been given a de facto diagnosis which, in many cases, entails limitations concerning a person’s development of independence [Citation36,Citation37]. There were major differences between the five courses in terms of preparing participants for a future as independent citizens. Three of the courses are general educational courses at upper secondary school level and do not focus on making participants employable. In the individual courses which specialised in independent living, work-life, and social competence, there were some established contact networks in the surrounding community and good opportunities for internships where participants had the chance to show their abilities to potential employers and not least to themselves. In addition, much of the preparatory work involved making the participants aware of the demands, including social demands, that a job entail. We believe that there is room for Folk High School to improve on its efforts to gradually challenge all participants, irrespective of the type of course they attend, in areas where they can develop more self-reliance and independence.

Conclusion

Folk High School, with its special approach, succeeds in satisfying the needs of participants with high-functioning autism. Many of these participants, for the first time in their lives, experience a sense of inclusion in the education system and a feeling that they can succeed in their academic endeavours. However, the risk of institutionalisation remains, which entails that these participants primarily function well in the safe and caring environment that is provided to them by the Folk High School system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Goodley D. Disability studies. An interdisciplinary introduction. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2017.

- Houtenville AJ, Brucker DL, Lauer EA. Annual compendium of disability statistics, 2015. New Hamshire: University of New Hampshire, Institute on Disabilities; 2016.

- Meekosha H, Soldatic K. Human rights and the global South: the case of disability. Third World Quarterly. 2011;32(8):1383–1397.

- World Health Organization and The World Bank. World report on disability. Genéve: World Health Organization; 2011.

- Larsson Abbad G. “Aspergern, det är jag” – En intervjustudie om att leva med Asperger Syndrom. Linköping: Linköpings Universitet, Institutionen för beteendevetenskap och lärande; 2007.

- Hendricks D. Employment and adults with autism spectrum disorder: challenges and strategies for success. J Vocat Rehab. 2010;32(2):125–134.

- Krieger B, Kinébanian A, Prodinger B, et al. Becoming a member of the work force: perceptions of adults with Asperger syndrome. Work. 2012;43(2):141–157.

- Roy M, Prox-Vagedes V, Ohlmeier MD, et al. Beyond childhood: psychiatric comorbidities and social background of adults with Asperger syndrome. Psychiatr Danub. 2015;27(1):50–59.

- Andersén A. Ett särskilt perspektiv på högre studie? Folkhögskoledeltagares sociala representationer om högskola och universitet. Jönköping: Jönköping University; 2011.

- Paldanius S. En folkhögskolemässig anda i förändring: En studie av folkhögskoleanda och mässighet i folkhögskolans praktik. Linköping: Linköpings universitet; 2007.

- Centralbyrån S. Unga utanför? Så har det gått på arbetsmarknaden för 90-talister utan fullföljd gymnasieutbildning. Örebro: Statistiska Centralbyrån; 2017.

- Adolfsson M, Simmeborn Fleischer A. Applying the ICF to identify. Requirements for students with Asperger syndrome in higher education. Develop Neurorehab. 2015;18(3):190–202.

- Giarelli E, Fisher K. Transition to community by adolescents with Asperger syndrome: staying afloat in a sea change. Disabil Health J. 2013;6(3):227–235.

- Simmeborn Fleischer A. Support to students with Asperger syndrome in higher education – the perspectives of three relatives and three coordinators. Int J Rehabil Res. 2012;35(1):54–61.

- Folkbildningsrådet. Folkbildningsrådets samlade bedömning –Folkbildningens betydelse för samhället 2017. Stockholm: Folkbildningsrådet; 2017.

- Kindblom L. Invandring och svenskundervisning - så började det. Stockholm: Leif Kindblom förlag; 2016.

- Skogman E. Att studera som vuxen med funktionsnedsättning. En fördjupad studie av studerandes erfarenheter. Stockholm: Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten; 2015.

- Nylander E, Bernhard D, Rahm L, et al. oLika TillSAMmanS: En kartläggning av folkhögskolors lärmiljöer för deltagare med funktionsnedsättning. Linköping: Linköping University Press; 2015.

- Folkbildningsrådet. Folkhögskolans förstärkningsbidrag – En fördjupad analys 2017. Stockholm: Folkbildningsrådet; 2018.

- Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten. Villkor för utbildning – Kartläggning av nuläge för barn, elever och vuxenstuderande med funktionsnedsättning. Stockholm: Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten; 2017.

- Barnhill GP. Outcomes in adults with Asperger syndrome. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2007;22(2):116–126.

- Fiske S, Taylor S. Social cognition: from brains to culture. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2013.

- Gillberg C, Ehlers S. Asperger syndrome: an overview. London: National Autistic Society; 2006.

- Happé F, Frith U. The weak coherence account: Detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36(1):5–25.

- Striano T, Reid V, editors. Social cognition: development, neuroscience and autism. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

- Mendelson JL, Gates JA, Lerner MD. Friendship in school-age boys with autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analytic summary and developmental, process-based model. Psychol Bullet. 2016;142(6):601–622.

- Hinterbuchinger B, Kaltenboeck A, Baumgartner JS, et al. Do patients with different psychiatric disorders show altered social decision-making? A systematic review of ultimatum game experiments in clinical populations. Cognit Neuropsych. 2018;23(3):117–141.

- Cotter J, Granger K, Backx R, et al. Social cognitive dysfunction as a clinical marker: a systematic review of meta-analyses across 30 clinical conditions. Neurosci Biobehavior Rev. 2018;84:92–99.

- Tulaci RG, Cankurtaran ES, Özdel K, et al. The relationship between theory of mind and insight in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nordic J Psychiat. 2018;72(4):273–280.

- Erol A, Akyalcin Kirdok A, Zorlu N, et al. Empathy, and its relationship with cognitive and emotional functions in alcohol dependency. Nordic J Psychiat. 2017;71(3):205–209.

- Bal E, Harden E, Lamb D, et al. Emotion recognition in children with autism spectrum disorders: relations to eye gaze and autonomic state. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(3):358–370.

- Golan O, Baron-Cohen S, Hill JJ. The Cambridge mindreading (CAM) face-voice battery: Testing complex emotion recognition in adults with and without Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36(2):169–183.

- Golan O, Baron-Cohen S, Hill JJ, et al. The 'Reading the Mind in the Voice' test-revised: a study of complex emotion recognition in adults with and without autism spectrum conditions. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(6):1096–1106.

- Wallace GL, Case LK, Harms MB, et al. Diminished sensitivity to sad facial expressions in high functioning autism spectrum disorders is associated with symptomatology and adaptive functioning. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(11):1475–1486.

- Morie KP, Jackson S, Zhai ZW, et al. Mood disorders in high-functioning autism: the importance of alexithymia and emotional regulation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;47(9):2935–2945.

- Low J, Goddard E, Melser J. Generativity and imagination in autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from individual differences in children’s impossible entity drawings. British J Develop Psychol. 2009;27(2):425–444.

- Adams NC, Jarrold C. Inhibition in autism: Children with autism have difficulty inhibiting irrelevant distractors but not prepotent responses. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(6):1052–1063.

- White SJ. The triple I hypothesis: Taking another’s perspective on executive dysfunction in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(1):114–121.

- Dachez J, Ndobo A. Coping strategies of adults with high-functioning autism: a qualitative analysis. J Adult Dev. 2018;25(2):86–95.

- Linton FK. Clinical diagnoses exacerbate stigma and improve self-discovery according to people with autism. Social Work Mental Health. 2014;12(4):330–342.

- Svensk författningssamling. Diskrimineringslag. Vol. 567. Stockholm: Socialdepartementet; 2008.

- Socialstyrelsen. Insatser och stöd till personer med funktionsnedsättning Lägesrapport 2017. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2017.

- Nirje B. The normalization principle and its human management implications. Int Social Role Valoriz J. 1994;1(2):19–23.

- Larsen V, Lyng Rasmussen G. Social- og specialpaedagogik i teori och praktik. Fredriksberg: Frydenlund; 2017.

- Hedegaard J, Hugo M. Social dimensions of learning – the experience of young adult students with Asperger syndrome at a supported IT education. Scandinavian J Disab Res. 2017;19(3):256–268.

- Hugo M, Hedegaard J. Education as habilitation: empirical examples from an adjusted education in Sweden for students with high-functioning autism. AS. 2017;23(3):71–87.

- Unger KV. Psychiatric Rehabilitation through Education: Rethinking the Context. In: Farkas MD, Anthony, WA, editors. The Johns Hopkins series in contemporary medicine and public health. Psychiatric rehabilitation programs: putting theory into practice. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1989. p. 132–161.

- Unger KV, Anthony WA, Sciarappa K, et al. A supported education program for young adults with long-term mental illness. PS. 1991;42(8):838–842.

- Bengs A-K, Borg G, Liljeholm U. Studieinriktad rehabilitering – ur tre perspektiv [Supported Education]. Stockholm: FoU-Södertörn; 2013.

- Waghorn G, Still M, Chant D, et al. Specialised supported education for Australians with psychotic disorders. Australian J Social Issue. 2004;39(4):443–458.

- Kidd SA, Kaur Bajwa J, McKenzie K, et al. Cognitive remediation for individuals with psychosis in a supported education setting: a pilot study. Rehab Res Pract. 2012;2012:1–715176.

- Kidd SA, Kaur J, Virdee G, et al. Cognitive remediation for individuals with psychosis in a supported education setting: a randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia Res. 2014;157(1–3):90–98.

- Manthey TJ, Goscha R, Rapp C. Barriers to supported education implementation: implications for administrators and policy makers. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(3):245–251.

- Stoneman J, Lysaght R. Supported education: a means for enhancing employability for adults with mental illness. Work (Reading, Mass.). 2010;36(2):257–259.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2009.

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2004.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115.

- Creswell JW. Research design. London: Sage Publications, Inc; 2014.

- Larsen A-K. Metod helt enkelt [Method, quite simply]. Malmö: Gleerups; 2009.

- Tesch R. Qualitative research: analysis types and software tools. New York: Falmer; 1990.

- Swedish Research Council. Forskningsetiska principer inom humanistisk-samhällsvetenskaplig forskning. Stockholm: Swedish Research Council; 2002.

- Swedish Research Council. Särskilda anvisningar för utbildningsvetenskap. Stockholm: Swedish Research Council; 2005.

- Hugo M. Meningsfullt lärande i skolverksamheten på särskilda ungdomshem. Institutionsvård i fokus. Vol. 1. Stockholm: Statens institutionsstyrelse; 2013.