Abstract

Purpose

People with aphasia post-stroke are at risk for depression and social isolation. Peer-befriending from someone with similar experiences may promote wellbeing and provide support. This paper explored the views of people with aphasia and their significant others about peer-befriending.

Materials and methods

We conducted a qualitative study within a feasibility trial (SUPERB) on peer-befriending for people with post-stroke aphasia and low levels of distress. Of the 28 participants randomised to the intervention, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with 10 purposively selected people with aphasia (at both 4- and 10-months post-randomisation) and five of their significant others (at 4-months). Interviews were analysed using Framework Analysis.

Results

Participants and their significant others were positive about peer-befriending and identified factors which influenced their experience: the befrienders’ personal experience of stroke and aphasia, their character traits and the resulting rapport these created, the conversation topics they discussed and settings they met in, and the logistics of befriending, including planning visits and negotiating their end. Interviewees also made evaluative comments about the befriending scheme.

Conclusion

Peer-befriending was an acceptable intervention. Benefits for emotional wellbeing and companionship were reported. The shared experience in the befriending relationship was highly valued.

The lived experience of stroke and aphasia of befrienders was highly valued by people with aphasia receiving peer-befriending.

Training, regular supervision, and support for befrienders with practicalities such as organising visits ensured the befriending scheme was perceived as straightforward and acceptable by befriendees.

Those receiving peer-befriending would recommend it to others; they found it beneficial, especially in terms of emotional wellbeing and companionship.

Implications for Rehabilitation

TRIAL REGISTRATION:

Introduction

Aphasia is an acquired communication disability most commonly caused by stroke and affects approximately one-third of stroke survivors [Citation1]. Stroke and aphasia can have a profound impact on people’s lives. Anxiety and depression are common consequences of stroke, with depression remaining in around one-third of survivors one-year post-onset [Citation2]. There is evidence that the psychological needs of people with aphasia are even greater, with a 62% rate of depression reported in this group one-year post-stroke [Citation3]. Social support and social networks are also affected: people with stroke and aphasia risk losing contact with their wider network and friendships are particularly vulnerable [Citation4]. Yet friendships are a crucial aspect of living successfully with aphasia [Citation5]. Poor social support is associated with worse physical recovery [Citation6] and an increased likelihood of a second stroke [Citation7].

A UK audit of clinical psychology services for people with low mood post-stroke found that monitoring and advice were the most common outcomes of mood assessment, with less than half of the audited patients receiving psychological interventions [Citation8]. However, the National Clinical Guideline for Stroke [Citation9] highlights that psychological care after stroke should be multifaceted, involving health, social care and voluntary agencies. It recommends that people with stroke should be offered psychological support regardless of whether they exhibit specific mental health or cognitive difficulties, advocating a stepped care model to select the level of appropriate support. Yet a Cochrane systematic review on the effectiveness of psychological therapies for post-stroke depression identified that most studies excluded people with aphasia [Citation10]. Therefore, there is a pressing need to evaluate interventions that aim to improve psychosocial wellbeing for people with stroke, and people with aphasia in particular.

A systematic review of interventions aiming to treat and/or prevent depression in stroke survivors with aphasia found that though some interventions may enhance the mood for those without clinically significant depression, they do not lead to significant reductions in depression scores [Citation11]. The SUpporting wellbeing through PEeR-Befriending (SUPERB) study aimed to address this need for people with aphasia with no or low levels of psychological distress. It aimed to test an early intervention for individuals with mild or no mood problems, particularly with a view to preventing the adverse, long-term psychological consequences that so often follow stroke and aphasia.

Peer-befriending consists of social and emotional support provided by people with experience of a condition to others with a similar condition, in order to facilitate a desired social or personal change [Citation12] and is widely used in mental health [Citation13] and other long-term conditions [Citation14]. Peer-befrienders whose own condition has improved has been found to offer acceptance, respect, empathy and hope, and opportunities to share experiences and coping strategies [Citation15]. Peer-befriending has been evaluated in stroke, but within a hospital setting rather than the community, and people with severe aphasia were excluded [Citation16].

In the UK, a charity for people with aphasia (Aphasia Re-Connect, formerly Connect—the communication disability network) offers a peer-befriending scheme. The scheme, mostly targeting socially isolated people with aphasia in the longer-term post-stroke, reported positive outcomes for people with aphasia, their families, and health professionals involved in their care [Citation17]. The SUPERB study tested the feasibility of a refined version of this peer-befriending scheme. It was offered to people with aphasia in the early stages post-stroke when they had been discharged to the community from the hospital and once intensive rehabilitation had ended. This paper reports the findings from a nested qualitative study within SUPERB and involved qualitative interviews with recipients of peer-befriending, and with their significant others. Qualitative interviews with recipients of peer-befriending with other conditions [Citation18,Citation19] have been conducted in order to further explore befriendees’ perceptions of the support they received. This paper also reports the findings from interviews, which explored the experiences of the peer-befriending intervention, including their overall impression, their relationship with the befriender, any perceived impact of the intervention, any difficulties experienced, and their views on the logistics of the intervention.

Materials and methods

Ethics

Ethical approval for the SUPERB study was granted by the NHS Health Research Authority London-Bloomsbury Research Ethics Committee (ref 16/LO/2187). Local NHS Research and Development approvals were gained from all participating sites. All participants gave consent to take part in the study and be interviewed. Reporting follows the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ, [Citation20]). (Supplementary file 1).

Study design-broader SUPERB study

The SUPERB study was a single-blind, mixed method, parallel-group feasibility (phase II) multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) which compared usual care with usual care + peer-befriending for people with aphasia post-stroke who had low levels of psychological distress [Citation21]. Eligible significant others who gave their consent were also enrolled.

Study design-qualitative study

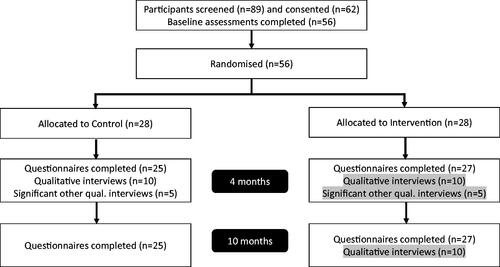

The qualitative study used semi-structured interviews of purposively sampled participants (n = 20) and significant others (n = 10) from both arms of the trial at 4-months post-randomisation, which was post-peer-befriending for those in the intervention arm, to explore the acceptability of trial procedures, experiences of care and the process of adjusting to life with aphasia after stroke (CONsolidated Standard Of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) [Citation22] diagram in ). These findings are reported elsewhere [Citation23,Citation24]. Those in the PEER arm were also asked about their experience of being befriended and were re-interviewed at 10-month post-randomisation to further reflect on these experiences. The current paper focuses on this topic, reporting on the interviews with people with aphasia in the intervention arm (n = 10) at both 4-months and 10-months and the significant others in the intervention arm (n = 5) who were interviewed at 4-months (, in total n = 25 interviews). Peer-befrienders were also interviewed about the scheme; these data are reported elsewhere [Citation25].

Recruitment and participants in the broader SUPERB study

Participants were recruited from North London hospitals, community services (e.g., speech and language therapy teams) and GP practices. Baseline assessments and randomisation took place after discharge from the hospital and once intensive rehabilitation, e.g., the early supported discharge had ended in the community.

Participants with aphasia had to meet the following criteria: ≥18 years of age; fluent premorbid users of English (confirmed by relative or self-report); the presence of aphasia due to stroke (determined by the multidisciplinary team notes, based on SLT diagnosis); and low level of emotional distress, determined by their score of ≤2 on the Depression Intensity Scale Circles (DISCS) [Citation26].

Each person with aphasia was invited to nominate one significant other (and up to three alternatives), who was their closest confidant and ≥18 years old. If participants lived alone, their significant other was someone they saw at least once a week. Consent was sought from the significant other to take part in the study. When the significant other did not meet eligibility criteria or did not give consent, other nominated individuals were approached. People with aphasia without a significant other were still eligible to take part.

Exclusion criteria for participants with aphasia and significant others were: other diagnoses affecting cognition or mental health, for example, advanced Parkinson’s disease, motor neurone disease, dementia, clinical depression; severe uncorrected visual or hearing problems; and severe or potentially terminal co-morbidities, on grounds of frailty. People with aphasia were also excluded if they were discharged to a geographical location away from the borough of the recruiting hospital, as this made it unfeasible for peer-befrienders to visit those in the intervention arm.

Fifty-six participants with aphasia were randomised in SUPERB, 28 in each arm. Of these, 48 had a significant other taking part (n = 24 in each group).

Participants in the qualitative study

In this article, the focus is on the participants with aphasia (n = 10) (henceforth referred to as befriendees) and significant others (n = 5), interviewed from the intervention arm of the trial. They were purposively sampled to ensure they were representative of the wider group. For befriendees, key criteria were severity of aphasia (mild or moderate/severe), determined by the Western Aphasia Battery-revised (WAB-R, [Citation27]) Aphasia Quotient, and whether the person lived alone. Secondary criteria were: geographical area of residence, gender, mobility (i.e., wheelchair user or not), mood (no/low distress vs. high distress), determined by baseline General Health Questionnaire 12 (GHQ-12) score, and ethnicity. For significant others, sampling criteria included relationship to the person with aphasia (partner/spouse or child/other), ethnicity, gender and General Health Questionnaire 28 (GHQ-28) score. Owing to this sampling strategy, there were three occasions where a significant other was interviewed but not the befriendee who nominated them.

Procedures

Intervention

Full details of the intervention are in the protocol TIDieR checklist [Citation21]. The intervention aimed to use the “lived experience” of befrienders to offer emotional, social, and informational support to befriendees to help them move forward and develop their own strategies for adjusting to life post-stroke. In their first visit, the pair agreed on the schedule and nature of visits. They also identified possible goals for the intervention. For example, participants might discuss concerns or activities that they would like to pursue. Subsequent visits may include conversation, problem-solving, and joint activities.

To deliver the intervention, befrienders received comprehensive training about their role as peer supporters, managing health and safety and risk prevention, and dealing with challenging situations. They were encouraged to share their personal experiences and to offer tips, advice and practical support. Befrienders also attended monthly group supervision sessions and additional one-to-one support as and when needed.

The intervention comprised six befriending visits between randomisation and 4-months, followed by two optional visits by 10-months for a gradual transition to the end of befriending. All visits were conducted in a befriendee’s home or community settings if befriendees were sufficiently mobile, and were arranged between the dyads for mutual convenience, supported by the befrienders’ supervisor (SM) where necessary.

Data collection

Interview topic guides were developed by a senior qualitative researcher (SN) (Appendices 1 & 2) and discussed with a user group of people with aphasia, who suggested minor changes and a small number of additional questions, which were incorporated. The befriendees and significant others were seen in the community, typically at home, and informed about the aims of the qualitative study. They were also informed of the interviewer’s role in the study and made aware that she would not be involved in outcome assessments. At the beginning of the interview, participants were reassured that there were no right or wrong answers. Face-to-face interviews were audio and video-recorded with written consent. A research assistant (KM), a speech and language therapist with extensive experience in communicating with people with aphasia, conducted the semi-structured interviews. She was trained by a senior qualitative researcher (SN), who had prior experience in adapting qualitative methodologies for people with aphasia. Pictures and photographs were used to support communication, and “total communication” techniques [Citation28] such as gesture, drawing, facial expression and tone of voice were used to support speech.

The senior qualitative researcher viewed two videotaped initial interviews and gave feedback to ensure questioning was unbiased and led to a full exploration of topics. She also provided supervisory support throughout the trial. All interviews with participants were transcribed by the research assistant. The lead data analyst (BM) checked 25% of these for accuracy and no discrepancies were found. Interviews with significant others were transcribed either by the research assistant or external transcription service. In the latter case, these were all checked for accuracy by the research assistant. On occasion, the research assistant made field notes for personal reflection, but these were not part of the analysis.

Analysis

All qualitative data were analysed using Framework Analysis [Citation29]. Initial themes and concepts were identified through reviewing the data, then used to construct a thematic index in order to assign a label to each phrase or passage of the transcripts. Labeled raw data were summarised and synthesised into thematic matrices, to facilitate systematic exploration of the full range of views, including both between and within cases. Finally, descriptive and explanatory accounts of the data were produced. Data were organised and analysed using NVivo version 12 (QSR International).

In order to increase the trustworthiness of the analysis, the lead analyst (BM) did not conduct any of the interviews, though she conducted outcome assessments with some participants in the course of the wider study. The lead analyst, a clinical linguist with extensive experience in qualitative analysis, developed the thematic index. It was further refined through discussion with the research team. Coding was conducted by the lead analyst, then a second analyst (NB) read through three of the coded transcripts (12%), and also reviewed 37.5% of the thematic matrices’ material. This resulted in minor labeling amendments but no major thematic changes. A senior qualitative researcher (SN) oversaw all stages of the analytic process, and discussed the emerging themes with the research team, including exploring whether the diversity of experiences was reflected fairly in the final analysis.

Results

Participants and interviews

Full participant characteristics are shown in and . To preserve their anonymity, the participants have all been given pseudonyms. Of the befriendees, five were male and five female. Six had mild aphasia, four moderate/severe. Four were wheelchair users and three lived alone. Five were black, four white and one mixed race. The age range was 53–84, median (IQR) 69 (64–77). Two of the participants’ significant others were interviewed, besides three other significant others sampled from the wider trial, totaling four females and one male. Two were spouse/partner to the participant, and three were their child/other e.g., friend. Three were white, one black and one mixed race. Their ages ranged 41–83, median (IQR) 65 (42–82.5).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants with aphasia.

Table 2. Characteristics of significant others.

The significant others of the two befriendees (Ivy and Elizabeth) were daughters, the other three were one wife (of Benjamin), one husband (of Enid) and a further daughter (of Marcellino). Interviews with befriendees and significant others were one-to-one, with the exception of Benjamin remaining present when his wife was interviewed; his contributions are not included here. One participant was interviewed but discounted, in consultation with the research team, owing to the inability to stay alert and fully engage with the interview; an additional participant was therefore purposively sampled and interviewed. No befriendees declined the interview; one significant other declined, and another was purposively sampled and interviewed. Length of befriendee interviews ranged 15–82 min, median (IQR) 47 (34–59); length of significant other interviews ranged 22–46 min, median (IQR) 34 (27.5–45.5).

Four main themes emerged from the data: participants talked about the befrienders, their experience of stroke and aphasia and the befriender characteristics that incited rapport; they reflected on the conversations they had and what they did during befriending; they talked about the logistics of befriending, including planning visits and endings; and evaluated the impact befriending had on them.

The peer-befrienders

Experience of stroke and aphasia

The fact their befriender had also experienced a stroke and had aphasia was referred to by all the befriendees. A small number, who lived alone, said their befrienders having this personal experience was not that important to them, instead emphasising the pleasure of having a regular visitor for conversation and a friendly atmosphere. However, for most it was seen as an important and positive attribute, helping them realise they were not alone in their experience. They felt they were speaking to someone who could truly understand. Some described the relationship as “therapeutic,” owing to the “fellow feeling” between them and their befriender. For example, Samson said:

I discuss her predicament [because she’s] also in the same situation …. I’m not on my own, I’m not the only person who is suffering this … so I take some sort of confidence in that.

Another befriendee, James, remarked that his befriender’s personal experience of stroke meant that, unlike friends and medical professionals, the befriender would not make comments which were intended to be encouraging but which James found insensitive:

A lot of people say “you look really well,” he’d never say that to me … whereas other people wouldn’t understand it … It’s not relevant to how I look or don’t look, it’s how I feel. And “Oh you’re so lucky” sort of thing. I’m not lucky and God forbid that you’d have that experience. Unless it happens to you it’s difficult to understand what the difference it makes to you, a stroke. A big, big thing.

Some said that seeing their befriender’s progress towards recovery incentivised them, giving them confidence that they too would improve. For example, Betsy observed:

You have to know that some people are also like, like the same of you. They, they got a stroke. And eh they are getting/oh/okay. So, you know that way to going to be okay…. I can see that he was getting eh up and down… I wouldn’t like to my door, I didn’t like to go out. But now because he comes, we go, we go out.

Several participants drew direct comparisons between themselves and their befriender. Despite their relatively recent experience of symptom onset, many of these comparisons led to positive reassessments of the severity of their own stroke, suggesting that witnessing the befriender’s challenges had altered their perspective. For example, Marilyn said:

Also, for me to see somebody who’s the living proof of somebody who’s had a very bad stroke. And is still surviving. I think she’s eh somebody you would admire.

Most dyads also talked about their experience of stroke and aphasia. Befrienders offered empathy, describing their own post-acute experiences and subsequent progress milestones, and provided gentle encouragement to get out of the house, go on holiday or resume driving. They also recommended the next steps such as seeking further physiotherapy, and some brought photocopied information to visits. Befriendees also noted that befrienders gave advice and tips from personal experiences, such as recommending local stroke support groups and a taxi-card service, and reported this advice was helpful and had been acted upon.

Many of these themes were still present at 10-month follow-up, when befriendees reflected on the visits they had received. They emphasised the sense of encouragement they had felt, both in terms of hope for future progress and through comparison to befrienders’ own impairments and challenges. For example, James said a key realisation for him was that his befriender was still able to drive and that he could aspire to that too, while Ivy said:

To me I’m better off than him, I have more family…. But he is happy even though he walks with a stick - when I was sick, I didn't realise I was better off than some, so I was disturbed until I saw him, then I said “Oh, I'm blessed.”

Mutual experience and a sense of shared insight were also cited as valuable at this stage. For example, Jonathan said that therapists had sometimes “disregarded” something he had said if it was not word-perfect, whereas with his befriender they had both been resourceful and worked together to ensure they understood one another. At 10-months, one befriendee, Enid, recalled that as well as receiving support on coping strategies, she had reciprocated: when her befriender was experiencing persistent arm pain, she advised her to “go to the doctors and kick up a stink.” One significant other felt this reciprocity was skewed, and that her husband supported his befriender more than she supported him:

I’m not knocking her … but it wasn’t filling a need for us. There were times when we felt that the boot was on the other foot.

Like the befriendees, some of the significant others also felt that the befriender’s personal experience of stroke and aphasia was a particular asset. They reported this made them realise that their loved one was not alone, that progress was possible (“So I’m like, see: she can do it, so can you,” Ivy’s daughter) and that help was available. They also felt there was a connection and empathy between the dyads because of this shared experience. Enid’s husband said seeing how his wife was helped by the visits also impacted him, demonstrating that “if I am helping her, then I’m helping myself. Because it helps me to feel better about her disability.”

Ivy’s daughter regarded befriending as a form of counselling:

They are experts. They have been through the same path, so they are the best people to talk to. It gives you the confidence and hopes that people have been through it that you can also go through it and be perfect, it’s not the end of life. Somebody who has been through it, who has a different opinion compared to me, and that person is not a close family member like me… she will take him more seriously than what I may say to her.

Some significant others did not feel their family members had benefitted from their befriender having aphasia, either because the befriender’s speech was difficult to understand, or they did not converse enough.

Befriender character traits and rapport

Many befriendees offered examples of what made their befriender an ideal candidate for providing peer support, often describing them as “chatty,” “talkative” or “outgoing.” Sympathy and humour were also valued, besides patience and an ability to listen. Ivy described her befriender as “strong, advisable” [capable of giving useful advice], while Marilyn spoke of her respect for her befriender, explaining: “She’s lovely yeah. I think she’s amazing, you can tell she’s a feisty woman and she’s eh independent, I admire her.” This meant that the visits were both “a little something to look forward to,” but further that the befriender also became a positive role model, to whose approach Marilyn aspired.

Some indicated they liked being befriended by individuals with similar personality traits to themselves, such as being “funny,” “gentle” and “interesting.” Several spoke of rapport, and how they “gelled” with their befrienders, with one describing an affectionate relationship, saying they hugged and kissed when greeting one another. David said:

It's important your befrienders, don’t adopt a bossy attitude, there’s nothing worse … particularly when one’s feeling a bit under the weather. Laying down the law and not brooking any opposition to their eh statements, I would find that very irritating.

A minority of befriendees were initially reluctant to be recipients of befriending but explained that when they met face to face, they warmed to their befriender and changed their minds. For example, Marilyn was concerned when she learned of the disparity between her age and her befriender’s but was surprised by how easily they got along:

When I heard her age, I thought I’m gonna be too old for her [laughs]. I said that to [my husband] oh my God she’s, and then when I met her, I said oh my God [laughs], she’s tall, she’s a very attractive woman, she’s not going to want to see me again because I’m in my seventies … But it was good… I loved meeting her and we had got very, very friendly towards the end.

Another, Trevor, had expressed a preference for a female befriender whose age was close to his, and was pleased when a suitable match was arranged.

Two of the participants were paired with a befriender who was from their country of origin and with whom they shared a common language. This was very positively received and appeared to create a firm bond, as they enjoyed reminiscing about their country together, and speaking in their first language which was easier for the befriendee than English since her stroke. Another said that speaking the same language as her befriender had made him ‘my brother’ and that they continue to meet at a local stroke group because ‘we are like family’ a sentiment which increased when they realised the befriender’s brother-in-law attended the same church as the befriendee.

At a 10-month follow up, one befriendee, David, reflected further on the importance of being carefully matched with his befriender. He said their shared sense of humour, even though they were “totally different people” was central to their rapport.

One significant other felt that in hindsight her father would have preferred a younger, female befriender, and someone more “bubbly.” However, most significant others spoke of an affectionate relationship between the pairs: Enid’s husband explained “it was nice to see…. It was the love, that’s what it is …. It’s only love that flows out from these people.” Elizabeth’s daughter added that her mother was initially a shy and reserved person when she met new people, particularly now that she had aphasia, but that her befriender’s “calm and relaxed” demeanour meant they had been able to have “a good chat.” Despite an unfavourable stance on befriending generally, Benjamin’s wife spoke positively of the befriender’s attributes:

She’s got a lovely, warm, affectionate personality. There’s a tremendous amount of good, and goodwill and friendliness radiate from her. She’s got very, very good qualities. I would think one of the reasons that she is put forward as a befriender is because of her very commendable get up and go.

Conversation topics and activities

As described above, most pairs discussed their experiences of stroke and aphasia. Participants described a prevailing sense that conversation flowed naturally and was “a two-way thing;” David remarked: “She was good company, she had a lot to say, never a dull moment.” The dyads talked about their respective families, political beliefs and their past, for example their work and countries of origin. Several pairs watched television news and sports together and then discussed or debated what they had seen. Trevor, a non-verbal participant, spent time playing dominoes with his befriender, sitting together in the garden, listening to music, looking at an ornithology book and listening to his befriender read the newspaper aloud to him.

Some of the more mobile participants and befrienders went on outings together, such as to a stroke group at a local community centre, or visiting local shops, which befriendees said had increased their confidence. One befriendee, Marilyn, took the initiative to arrange a schedule of independent coffee shops to visit with her befriender, saying:

I’m showing off my manor, aren’t I?! I found it fun to think of places, I wanted her to like them - she was very blunt about the first one [because it was too noisy].

At 10-month follow up, some befriendees mentioned the importance of being able to have “deep conversations” about stroke with someone who was “outside of my group [usual social circle], and the fact the befriender was “a stranger, she’s not a friend, she’s not a member of the family” (Marilyn).

Like the befriendees, significant others said the pairs had talked about family and friends, traveling and going out, and one recalled the befriender also showed the befriendee her artwork.

One significant other felt the conversation was stilted, but noted that had the befriendee been more mobile they may have enjoyed going on outings together. Another expressed disappointment that the pair had watched television rather than talking about stroke and aphasia, despite this being the befriendee’s preference, owing to his fatigue, rather than the befriender’s.

Intervention logistics

Planning visits

Arranging visits appeared to have been largely straightforward from befriendees’ perspectives. For example, Samson detailed how he and his befriender had ensured their plans went smoothly: his befriender would arrange a date for the next visit at the end of the session, and telephone the day before she was due to visit to confirm it; on one occasion she was going to arrive early and warned him of this. He would then follow up after each visit to check she was home safely.

A couple of minor issues were raised: occasionally visits went on too long, or there were substantial gaps between visits owing to holidays, which caused the last few visits to feel rushed. Marilyn felt this interfered with building rapport:

You meet somebody. You know something about them. But then there’s a long gap. What do I do? Do I start go back to the beginning or just pick it up? You know I was thinking about it, maybe overthinking a bit I don’t know.

Ending visits and continuing contact

Accepting that befriending was a finite service that would end after six visits (with the option of a further two to follow up) was problematic for a minority of befriendees. This was most often expressed as a mild disappointment, such as missing the befriender, or wishing there could be more visits. For James, the ending was a different and more significant issue. This was because he felt he had not been forewarned of the six-visit arrangement, and was shocked:

[Sighs] I didn’t even know until the last day that he wouldn’t be coming again… I didn’t know there was a limited amount … I don’t think anybody mentioned until the last day they said “I won’t be coming anymore” and I thought “Whoa, whoa!” …. I was enjoying that, and yet suddenly, it was, it’s over.

At the 10-month follow-up, this perceived sudden ending remained a source of regret for James. However, he reflected that this may be attributable to the fact that he was already frustrated that his formal cessation of stroke services was abrupt at that time.

Many other befriendees were not troubled by the end of visits, feeling that six visits were adequate, and pointing out they had other ways to fill their time. Others said the transition had been smooth as they continued to see their befriender at a stroke support group. One befriendee, David, organised a celebration to mark the end of befriending, making drinks and canapes for them both:

I knew she was game for a cocktail, so I had the whole work out nibbles, and I used the shaker… dry Martinis, my favourite and she seemed to like them.

He added that he did not feel the need for further befriending because he managed well on his own, and said that seeing his long-term friends was enough for him.

Few befriendees remarked on the timing of the intervention, and those that did felt it had been at an appropriate juncture post-onset. James said he could see both benefits and challenges in visits beginning sooner than they had: he felt it may have been useful earlier when he was “in the dark … to shed some light earlier on,” but conversely that at that point he “might not have been able to speak very well then.”

At 10-months, a minority of befriendees described they felt stronger and less sick than at 4-months. These individuals wondered if they may have derived more benefit from being befriended at a slightly later stage. For example, Rose said that now her mobility and the weather had improved, she would be able to go on outings and ride the bus with a companion, while Jonathan described being ‘not in a good frame of mind’ at the time of the visits. He added:

Most of that time, I was really sick but I try my best. I wasn’t feeling well at all. Things there were a lot of things that give me, hurting me inside.

It appeared that he felt he would have preferred to wait until his mood had improved to begin receiving the intervention.

There was no mention of concern about the intervention ending or wishing to continue contact among the significant others. A minority of significant others raised visit planning. One said: “Very good, she arrived on public transport and was very strict about just an hour and she was up and off.”

Participants’ evaluation of the befriending intervention

The befriendees unanimously agreed they would recommend peer-befriending to other people with their condition, even if they had described being initially reluctant to take part. They emphasised the benefits to the emotional wellbeing they had experienced through being befriended, including finding visits therapeutic and feeling they were not alone, and increased confidence and hope for future improvement. They also felt having a peer-befriender “relieved the tedium” of living alone with a serious health condition, providing company and offering a distraction from dwelling on perceived deficits:

It makes me think more when I’m lonely, but if somebody’s there I’m reengage in conversation, makes me forget about [how] I cannot do those things, then I become more remorse … At least you are occupied with something, therefore you don’t sit idle for you to ponder other things. (Samson).

For some, the detrimental effects of coping with stroke and aphasia alone prior to being befriended had been profound; for example, Ivy remarked: “Loneliness can also kill.” At the 10-month follow-up, these positive evaluations continued to be endorsed.

Benjamin’s wife stated that she liked his befriender, but did not feel her husband benefitted personally, as he had an adequate support system in place. Conversely, Enid’s husband was unequivocal in his recommendation of peer-befriending as a positive experience and emphasised the importance of shared insight rather than clinical expertise:

Because I can see the difference it’s made to [Enid]. She was able to relate more to [her befriender] than to any of the therapists that she’s been having to see.

He elaborated that he was impressed that the befriender was willing to “put effort into doing something outside herself … and doing it so well and so willingly.” Ivy’s daughter felt that befriending had benefitted not only her mother, but her too, saying: “It’s helped me not fighting for her to get that, but it was easy for her to get that help.”

Discussion

Befriendees and their significant others identified a wide range of factors that influenced their experience of peer-befriending. These included: the befrienders’ personal experience of stroke and aphasia, their perceived character traits and the resulting rapport these helped create, the conversation topics they discussed and settings they met in, and the logistics of befriending, including planning visits and negotiating their end. Interviewees also made general evaluative comments about the befriending scheme.

Peer-befriending: mutual experience and reciprocity

A strong theme was the importance of mutual experience in the dyads, which created a sense of being truly understood and not feeling alone. It also engendered comparisons between the befriendees and their befrienders, which appeared to encourage optimism for future progress, and at times a positive reframing of their own milder deficits and stronger social networks. Some befriendees and their significant others felt there was a therapeutic or counselling aspect of peer-befriending, which could not necessarily be provided by others in the befriendees’ social network. At the 10-month follow-up, befriendees were able to reflect that the relationship within the dyad had elements of reciprocity, and felt they too had also been able to offer peer support within the relationship. This was reflected, for example, in the concern shown by Samson for his befriender’s safe arrival home after visiting him. This mutuality of care has been found to be favoured in another study of peer support [Citation30], which demonstrated perceived benefits including the opportunity to give as well as receive support, and both ‘upwards’ and ‘downwards’ comparison with others whose progress was greater or less than their own. Furthermore, reciprocity, rather than passive receipt of care, was felt by participants in one communication impairment study [Citation31] as being central to social relationships and community belonging.

Befriendees further reported that they felt the conversation had been two-way and that they were able to have ‘deep’ conversations about stroke that they could not have with family, friends or clinicians. In a study of peer-befriending for carers of people with dementia [Citation32], similar feelings were reported, including a sense of being in a safe and trusting conversational environment. These findings appear to reinforce the argument that there may be greater benefits to being befriended by a peer rather than a volunteer. This reflects previous findings from a study where a group of 12 volunteers included a subgroup of four individuals who, like their befriendees, had personal experience of serious mental illness [Citation19]. They were thought to provide unique additional benefits, such as being a role model and having greater sensitivity to the power dynamics of their role, therefore paying more attention to equality in the relationship. These individuals were also reported as being more likely to advocate for their befriendees. Similarly, in the current study befriendees received not only encouragement but practical tips and advice, for example, to get out of the house, attend stroke groups or obtain access to free public transport. In a qualitative study of what people with aphasia want in order to aid their recovery [Citation33], practical support like this was also highly valued.

Matching befrienders and befriendees

Befriendees’ reflections on their befrienders’ character traits indicated the importance of careful matching to maximise the chances of rapport-building and positive outcomes. Befrienders were matched primarily on their geographical proximity to their befriendee, for ease of access by car or public transport. However, both parties were able to express additional preferences regarding characteristics such as age and sex and were also invited to indicate factors that would deter them from accepting a match. The trial manager consistently considered practicalities (e.g., smokers, pets), interests and hobbies, and commonalities in terms of ethnic/cultural background, religion and sex. Most befriendees did not express a preference regarding befriender ethnic or religious background, age or sex, however, a subgroup of individuals identified these as important variables. Though warned these criteria may not always be met, several befriendees indicated their pleasure at receiving a match they regarded as appropriate to their wishes. A particular advantage in the current study was the capacity to match two dyads who shared a first language and country of origin, with very positive results.

Significant other perspectives

While most significant others were also very positive about the value of a peer-befriending intervention, a minority appeared slightly less receptive to the intervention than were befriendees. This was owing to either perceived unsuitability of matches, for example, because the befriender’s aphasia was too severe or they were not sufficiently chatty; or because the intervention was regarded as not meeting their needs. It is notable however that these issues were not reflected in the befriendee interviews. It appears there are no other studies exploring the specific impact on significant others of their family member receiving a befriending intervention. It is notable that one recent qualitative study [Citation34] observed discordance between stroke survivors and their caregivers when describing the social and emotional repercussions. This suggests the relative importance of an intervention to address these issues may be different to the two groups.

Befriender characteristics, training and supervision

More general aspects of befrienders’ personalities and communication were also noted as key to being a skilled befriender, such as gentleness, humour and lack of bossiness, and this theme was also reflected in the befriender interviews [Citation25]. In other peer-befriending studies, befriendees have also described age, sex and warm personality traits as important to a successful match [Citation32]. Further, where befriendees in the current study had reported reservations, such as fearing they were too old for their befriender or preferring to “keep themselves to themselves,” they later re-evaluated this and felt they would recommend the scheme to others. This may be attributable in part to the in-depth training befrienders received as part of the scheme, and the ongoing supervision and support provided. This included managing difficult conversations and situations; their role, specifically, not a “friend,” nor an advisor, nor a healthcare professional, but a friendly peer willing to share tips and ideas about a range of issues; and behaviours to avoid. Supervision also included peer-befrienders sharing their experiences with the rest of the group, and offering one another constructive advice. Other successful peer-befriending studies have offered a similar package of training and support, and likewise reflected high levels of satisfaction from befriendees [Citation35].

Planning and ending peer-befriending

The logistics of visit planning were largely perceived by befriendees as straightforward. This underlines the importance of a well-coordinated intervention, as much work was undertaken both by the trial manager and befriender supervisor to ensure visits ran smoothly. This support is regarded as integral to good practice when setting up a befriending scheme [Citation36]. Support included preliminary informal health and safety and access checks, and practical tasks such as printing maps and assisting with route planning, besides being available for real-time telephone contact if problems were encountered. Similarly, great care was also taken to ensure befrienders were supervised and supported throughout [Citation25], in order that befriendees perceived the intervention as a simple process.

The end of the befriending scheme, though broadly found acceptable, was a regretful time for some, with expressions of sadness or of missing their befriender and the conversations they had. Though endings were discussed in detail both during the training and supervision, it seems even further attention should be paid to this throughout the course of the intervention, particularly since endings were also sometimes perceived as challenging by the befrienders [Citation25]. Similarly, in a mental health peer befriending intervention [Citation37], befrienders felt inadequately prepared for terminating contact, despite this having been covered in training and supervision. They explained the relationship had rapidly become meaningful and highly valued by the befriendee, and consequently they felt a responsibility for their emotional wellbeing. In the current study, this was especially the case if they felt their befriendees were vulnerable, for example if they had no family. In the Bray et al. study [Citation35], many peer-befrienders continued visits beyond their allotted timeframe, feeling that their befriendee had not yet reached a “good enough place.”

While continuing formal visits was not permitted in the current study, participants could meet socially, for example at stroke clubs or church, and several did so. However, other befriendees were satisfied that they had received ample support and could move on to access other resources and relationships.

Limitations and strengths of the study

In terms of study limitations, the small number of significant others may not have allowed their data to reach saturation, therefore we cannot be certain whether the full range of significant other views about peer-befriending was captured. This may have been further complicated by the sampling strategy, which meant that on occasion a befriendee but not their significant other was interviewed, or vice versa. Interviewing both individuals would have enabled further elucidation of differences between perceptions of the intervention between the two groups.

The study also had strengths. Besides spouses or partners, befriendees were free to nominate friends, adult children or other relatives as their significant other. Befriendees were interviewed immediately after the intervention and also at a longer-term follow-up, to allow a period of reflection. Participants were purposively selected to reflect a range of experiences; and careful facilitation allowed even those with severe aphasia to take part. To increase trustworthiness of findings multiple analysts were used.

Conclusion

Peer-befriending is a complex intervention requiring careful consideration of matching parameters and planning, and ongoing support and supervision. Overall, peer-befriending was an acceptable intervention that befriendees and a majority of significant others would recommend to others. The shared experience in the befriending relationship was highly valued, and benefits especially in terms of emotional wellbeing and social companionship were highlighted.

Supplementary_Material_1.pdf

Download PDF (152.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the recruitment sites and the participants in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Flowers HL, AlHarbi MA, Mikulis D, et al. MRI-based neuroanatomical predictors of dysphagia, dysarthria, and aphasia in patients with first acute ischemic – Stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2017;7(1):21–34.

- Hackett ML, Pickles K. Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(8):1017–1025.

- Kauhanen ML, Korpelainen JT, Hiltunen P, et al. Poststroke depression correlates with cognitive impairment and neurological deficits. Stroke (1970). 1999;30(9):1875–1880.

- Northcott S, Hilari K. Why do people lose their friends after a stroke? Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2011;46(5):524–534.

- Brown K, Davidson B, Worrall LE, et al. “Making a good time”: the role of friendship in living successfully with aphasia . Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2013;15(2):165–175.

- Tsouna-Hadjis E, Vemmos KN, Zakopoulos N, et al. First-stroke recovery process: the role of family social support. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(7):881–887.

- Boden-Albala B, Litwak E, Elkind MSV, et al. Social isolation and outcomes post stroke. Neurology. 2005;64(11):1888–1892.

- Lincoln N, Worthington E, Mannix K. A survey of the management of mood problems after stroke by clinical psychologists. Clinical Psychology Forum. 2012;231:28–33.

- Stroke NCGf. https://www.strokeaudit.org/SupportFiles/Documents/Guidelines/2016-National-Clinical-Guideline-for-Stroke-5t-(1).aspx.

- Allida S, Cox KL, Hsieh C-F, et al. Pharmacological, psychological, and non-invasive brain stimulation interventions for treating depression after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;(1):CD003437.

- Baker C, Worrall L, Rose M, et al. A systematic review of rehabilitation interventions to prevent and treat depression in post-stroke aphasia. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(16):1870–1892.

- Solomon P. Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27(4):392–401.

- Repper J, Carter T. A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. J Ment Health. 2011;20(4):392–411.

- Hoey LM, Ieropoli SC, White VM, et al. Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(3):315–337.

- Mead N, Lester H, Chew-Graham C, et al. Effects of befriending on depressive symptoms and distress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(2):96–101.

- Kessler D, Egan M, Kubina L-A. Peer support for stroke survivors: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):256–256.

- Hargroves DT. M. Life after stroke: commissioning guidance for clinical commissioning groups and local authority commissioners. 2017 [cited 2021 May 20]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2017/07/life-after-stroke.pdf

- Burn E, Chevalier A, Leverton M, et al. Patient and befriender experiences of participating in a befriending programme for adults with psychosis: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1–9.

- McCorkle BH, Dunn EC, Wan YM, et al. Compeer friends: a qualitative study of a volunteer friendship programme for people with serious mental illness. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2009;55(4):291–305.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Hilari K, Behn N, Marshall J, et al. Adjustment with aphasia after stroke: study protocol for a pilot feasibility randomised controlled trial for SUpporting wellbeing through PEeR Befriending (SUPERB). Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5(1):1–16.

- Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) and the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in medical journals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(11):MR000030–MR000030.

- Moss B, Northcott S, Behn N, et al. Emotion is of the essence …. number one priority: a nested qualitative study exploring psychosocial adjustment to stroke and aphasia. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2021. DOI:10.1111/1460-6984.12616

- Hilari K, Behn N, James K, et al. Supporting wellbeing through peer-befriending (SUPERB) for people with aphasia: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2021. DOI:10.1177/0269215521995671

- Northcott S, Behn N, Monnelly K, et al. “You get good rewardings for it”: a qualitative exploration of befrienders’ experiences delivering peer befriending to people with aphasia in the SUPERB feasibility trial. 2021.

- Turner-Stokes L, Kalmus M, Hirani D, et al. The depression intensity scale circles (DISCs): a first evaluation of a simple assessment tool for depression in the context of brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2005;76(9):1273–1278.

- Kertesz A. The western aphasia battery – revised (WAB-R). London, UK: Pearson Clinical; 2006.

- Rautakoski P. Training total communication. Aphasiology. 2011;25(3):344–365.

- Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: SAGE; 2003.

- Skea ZC, MacLennan SJ, Entwistle VA, et al. Enabling mutual helping? Examining variable needs for facilitated peer support. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):e120–e125.

- Pound C. Reciprocity, resources, and relationships: new discourses in healthcare, personal, and social relationships*. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2011;13(3):197–206.

- Smith R, Drennan V, Mackenzie A, et al. Volunteer peer support and befriending for carers of people living with dementia: an exploration of volunteers’ experiences. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(2):158–166.

- Worrall L, Sherratt S, Rogers P, et al. What people with aphasia want: their goals according to the ICF. Aphasiology. 2011;25(3):309–322.

- Bucki B, Spitz E, Baumann M. Emotional and social repercussions of stroke on patient-family caregiver dyads: analysis of diverging attitudes and profiles of the differing dyads. PLOS One. 2019;14(4):e0215425.

- Bray L, Carter B, Sanders C, et al. Parent-to-parent peer support for parents of children with a disability: a mixed method study. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(8):1537–1543.

- Volunteer Now. Good practice guidelines for setting up a befriending service. 2011 [cited 2021 May 20]. Available from: https://www.befriending.co.uk/r/24693-volunteer-now-good-practice-in-setting-up-a-befriending-service

- Simpson A, Quigley J, Henry SJ, et al. Evaluating the selection, training, and support of peer support workers in the United Kingdom. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2014;52(1):31–40.

Appendix 1

Topic guide for befriendees

Pre-interview:

Reaffirm consent; tape recording

Thank yous: for their time and taking part in the project

Reassurances: confidential; can stop/take a break; no right or wrong answers, their perspective

Time: 1 to 1½ hours [total length]

Aim of interview [reported in this paper]: Explore how they found taking part in the study (what worked well, what was less good, experiences of peer-befriending)

Topics:

overall impression of intervention

map out what sorts of things they did with their befriender (and explore how they experienced these)

relationship with the befriender (how they got on; how they negotiated the types of activities they did together; the significance, if any, of befriender having aphasia)

what worked well (if any)/ perceived as useful (if any)

impact of the intervention, if any, on their lives

what didn’t work well/ unhelpful

logistics (number, spacing, how it was arranged, process of being ‘matched’ and introduced, timing of befriending post stroke)

ending of the befriending

*** suggestions for change ***

Final question: How they would describe peer-befriending to someone who has just had a stroke

Appendix 2

Topic guide for significant others

Pre-interview:

Reaffirm consent; tape recording

Thank yous: for their time and taking part in the project

Reassurances: confidential; can stop/take a break; no right or wrong answers, their perspective

Time: 1 to 1½ hours [total length]

Aim of interview [reported in this paper]: Explore experiences of peer-befriending

Topics:

overall impression of intervention

map out what sorts of things their partner did with their befriender (and how the carer experienced these)

impact of befriending on carer’s life

what worked well (if any)/ perceived as useful (if any) – for carer

what didn’t work well/ unhelpful – for carer

logistics (number, spacing, how it was arranged, process of being ‘matched’ and introduced)

ending of the befriending

*** suggestions for change ***

Final question: How they would describe peer-befriending to someone who has just had a stroke?