Abstract

Purpose

To explore workers’ views and considerations on involving their significant others (SOs) in occupational health care.

Methods

Four focus group interviews in the Netherlands, with 21 workers who had visited an occupational health physician (OHP) due to work absence caused by a chronic disease. Data was analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

We distinguished four main themes: (i) attitudes towards involving SOs, (ii) preferences on how to involve SOs, (iii) benefits of involving SOs, and (iv) concerns with regard to involving SOs. Workers expressed both positive and critical opinions about involving SOs in occupational health care. Benefits mentioned included provision of emotional and informational support by SOs before, during, and after consultations. According to workers, support from SOs can be enhanced by informing SOs about re-integration plans and involving them in decision making. However, workers were concerned about overburdening SOs, and receiving unwanted support from them.

Conclusions

According to interviewed workers, engagement of SOs in occupational health care can help workers with a chronic disease in their recovery and return to work. However, they felt it is important to take SO characteristics and the worker’s circumstances and preferences into account, and to balance the potential benefits and drawbacks of involving SOs.

This study suggests that the worker’s re-integration process could benefit from informing significant others about the return to work plans, involving them in decision-making, and explicitly discussing how the significant other can support the worker.

Occupational health physicians have an important role in informing workers about the possibility and potential benefits of involving their significant others in the re-integration process.

The involvement of a significant other in the re-integration process needs to be tailored to the specific situation of the individual worker, taking into account the preferences of both the worker and significant other.

Findings suggest that it is important that occupational health physicians, workers and significant others are not only aware of the possible benefits of significant other involvement, but also of potential drawbacks such as interference during consultations, overburdening significant others, and significant others providing unwanted support.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Within the working population, the number of people with one or more chronic diseases will continue to rise due to various reasons, such as an aging population and unhealthy lifestyles [Citation1]. Although many individuals with a chronic disease are able to work, work participation rates among people with chronic diseases are still lower than those of the general population [Citation1,Citation2]. Significant others (SOs) like partners, family members, or friends, can play an important role in how workers cope with having a chronic disease, thereby influencing their work and health outcomes [Citation3–6]. In this context, SOs can be a valuable source of support to enable individuals to cope effectively with their chronic disease and manage their working life [Citation6,Citation7]. However, SOs may also hinder functioning and recovery, as, for example, when their illness perceptions result in overprotective behavior [Citation4,Citation8].

In clinical health care, research has demonstrated that family-oriented interventions involving SOs are more effective than care in which SOs are not involved [Citation6,Citation9–12]. It is therefore not surprising that various clinical and multidisciplinary guidelines advise health professionals to involve SOs in treatment and care and also to intervene when SOs exhibit detrimental cognitions and behaviors [Citation13–19]. In line with these guideline recommendations, SOs are frequently involved in medical consultations, mental health care, and rehabilitation [Citation20–22]. Nevertheless, it is currently not common practice to involve SOs in occupational health care [Citation21]. A recent survey study among occupational and insurance physicians (OHPs) showed that OHPs recognize the potential influence of SOs on recovery and work outcomes of workers with a chronic disease, but they also reported potential risks and barriers of SO involvement [Citation23].

Despite recommendations in occupational health guidelines to involve SOs to better support workers in their recovery and re-integration into work, as yet OHPs receive only limited guidance on how to manage such involvement. It is therefore not surprising that prior research suggests that a lack of self-efficacy of OHPs can partly explain why they often do not pay attention to the influence of SOs or involve them in treatment and care [Citation23]. These observations underline the need for more insight into the views of OHPs, workers, and SOs themselves, in order to develop clear guidelines and training for OHPs so that they can successfully implement SO involvement in worker recovery and reintegration into work [Citation24,Citation25].

Prior research among OHPs has already provided some insight into their views regarding this issue [Citation23,Citation26]. One study indicated that OHPs felt that the necessity and benefits of assessing the influence of SOs and involving them in treatment depended on factors such as the severity of the complaints, and the level of progress of recovery and re-integration [Citation23]. Furthermore, some OHPs expressed concerns that their questions about the cognitions and behaviors of SOs would be a breach of the SO’s and worker’s privacy.

To our knowledge, only one prior study has explored workers’ views about occupational health care consultations with a spouse, family member, or friend present [Citation26]. In that study, workers who had brought a companion to their consultation reported various reasons for doing this, one being the perception that their companion could provide additional information and support. However, the study did not explore workers’ ideas as to specific ways in which involvement of their SOs could better support them in recovery and re-integration. Moreover, as that study included only workers who brought a companion to their consultation [Citation26], including workers who did not bring a companion could yield other views and considerations. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to expand our knowledge of workers’ views and considerations regarding involvement of their SOs in occupational health care.

Materials and methods

Dutch context of occupational health care

In the Netherlands, OHPs are the primary providers of work-related care while other health care providers such as general practitioners and medical specialists are not expected to offer work-related support. Dutch employers are legally obliged to contract an OHP, who provides support in re-integrating sick employees during the first two years of sick leave. While occupational health services are paid by the employer, OHPs are independent advisors and work for employers as well as employees. They give independent advice and guidance, are bound by medical professional secrecy and have to comply with various privacy regulations. While workers can access an OHP for various issues related to work and health, consultations between workers and OHPs mostly take place in the context of longer lasting sickness absence. As employers are legally obligated to provide access to OHPs, consultations with OHPs mostly take place with employees. However, while less common, it is possible for self-employed workers with private disability insurance to receive counseling and return to work guidance from an OHP. In addition, sick-listed non-permanent workers, including unemployed workers, temporary agency workers and workers with an expired fixed-term contract, can apply for sickness benefits at the Dutch Social Security Agency and receive sickness absence counseling from an insurance physician.

Study design

For this study, we chose a qualitative approach, using semi-structured focus group interviews to explore the perspectives of workers. We chose this format because it enabled an in-depth exploration of workers’ experiences, feelings, opinions and beliefs, and it allowed for interaction and discussion among participants. We conducted the focus group sessions between November 2018 and January 2019, and used the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) to guide our reporting of the findings [Citation27].

Inclusion criteria

We included workers between the ages of 18 and 64, who had visited an OHP at least once due to work absence caused by a chronic disease, defined as a somatic or mental illness with a duration of at least three months or causing more than three illness periods a year [Citation28]. We did not restrict participation to a certain timeframe with regard to when workers had to have last visited an OHP. We included both employees and self-employed workers. In addition, both workers with and without experience of involving SOs in occupational health care were eligible for participation. As all sessions were held in Dutch, eligibility was restricted to Dutch speaking workers.

Recruitment

We recruited participants through the Patient panel of the Netherlands Patients Federation, and through 15 OHPs who agreed to help with recruitment of participants. Panel members with a chronic disease received an online invitation from the Netherlands Patients Federation, an umbrella organization representing more than 200 patient organizations. Panel members who expressed interest in participating in the study were approached by a representative of the Netherlands Patients Federation to confirm their eligibility, give them the opportunity to ask questions, and check their availability for the planned sessions. After panel members had agreed to participate in one of the sessions, their contact information was sent to the main researcher (NS).

Fifteen OHPs of HumanTotalCare, a holding company which operates two large nationwide operating Occupational Health Services in the Netherlands, informed eligible workers about the study, gave them a flyer explaining the aim of the study, and asked their permission to be contacted by the researchers. Workers who agreed signed a form granting consent to share their contact information with NS. After receiving the consent forms and contact information, the researcher contacted the workers to confirm whether they wanted to participate in the study, to invite them to ask questions, and to check their availability for the planned sessions.

For all workers who agreed to participate in one of the focus group sessions, NS checked whether they met the inclusion criteria before confirming their participation.

Data collection

Group interviews were held at different locations to facilitate participation by workers from different regions in the Netherlands. We aimed to have six to eight participants in each group, but for each session up to nine participants were included to allow for possible dropouts. Groups were mixed with regard to participant characteristics and recruitment method ().

Table 1. Participant characteristics per focus group session (N = 21).

Each focus group met for a duration of approximately two hours, including a short break halfway through the session. Before the start of each session, participants were asked to complete a brief questionnaire regarding their demographics and work situation. An experienced independent moderator led the sessions. Two researchers (NS, HdV) were also present during all sessions to help the moderator to monitor group interaction, ask follow-up questions, and take notes.

We used a semi-structured interview guide to ensure comparability of the focus groups and to aid the moderator. We used an iterative approach. After each session, we reflected on the data gathered and, where necessary, adapted the interview guide to better explore new insights during the following sessions. At the start of each session we briefly introduced the topic and explained the aim of the study. Subsequently, we discussed the following topics: opinions on and experiences with involving SOs in occupational health care, possible goals of involving SOs, relevant topics to discuss with SOs, considerations regarding whether or not to involve SOs, and specific ways in which to involve SOs. At the end of each session, each participant received a gift certificate of €20 and was offered reimbursement of travel costs.

Data collection continued until the point of saturation was reached. The data was considered saturated when no new codes occurred in the focus group data and analyses did not lead to any new emergent themes compared to the previous focus group sessions.

Sample characteristics

Through OHPs, we received contact information of ten workers. In response to the online invitation through the Patient Federation, initially about 150 panel members indicated to be interested in participation. After receiving additional information about the study and the dates, times and locations of the sessions, participation was confirmed by six of the workers recruited through OHPs and 19 panel members. No purposive sampling was performed due to the limited number of workers who were able to participate in one of the scheduled sessions. Four of the 27 participants who agreed to take part in the study were unable to participate due to other appointments, health problems or travel issues. One participant did not attend because she forgot about the focus group session and one participant did not attend for reasons unknown. In total, 21 workers participated in this study, divided over four focus groups ().

presents an overall summary of participants’ demographic and work characteristics. Participants’ mean age was 55 years (age range: 38–65 years). The majority of participants were men (66.7%), and highly educated (66.7%). Participants had a wide variety of types of chronic diseases, and 38.1% had one or more comorbidity. Seven participants (33.3%) indicated during the focus group sessions to have experience with involving a SO in health care. Five participants (23.8%) stated to have no experience with involving SOs, while nine participants (42.9%) did not indicate whether or not they had any experience with SO involvement.

Table 2. Characteristics of participating workers (N = 21).

Data analysis

All sessions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. For each session, we made a summary of the main findings of the topics discussed and sent it to the participants for member checking, inviting participants to respond when they had additional comments or disagreed with the content. We received no comments in response to the summaries. Two researchers (NS, AB) independently analyzed the data. Both researchers have a background in health sciences, and AB has substantial experience with qualitative research.

In the first stage of analysis, we closely read the transcripts to become familiar with the data. To analyze the data we used thematic analysis [Citation28]. We applied an inductive approach, starting with line-by-line coding of the transcripts. During this open coding process, we used qualitative data indexing software (ATLAS.ti) to assist the process and to produce an initial list of codes. Next, the two researchers sifted through the data, searched for similarities and discrepancies, and ultimately grouped and combined codes into subthemes in an iterative manner. We discussed disagreements regarding the coding and grouping process until reaching consensus. We then clustered subthemes into main themes, and discussed these with all members of the research team (NS, HdV, AB, SvdB, MH, SB) until reaching consensus regarding the final themes. The varied backgrounds and expertise of members of the research team augmented interpretation of the data and minimization of bias. Finally, we selected and translated appropriate quotations to illustrate each theme (NS) and had the translated quotes checked by a native English speaking editor. With these quotes we used the following transcript conventions:

… Short pause

(…) Words omitted to shorten quote

[text] Explanatory information included by the author

F/M(number) Identifier of participant providing the quote

Ethical considerations

Participants received written information regarding the confidentiality and anonymity of the study results and were given an opportunity to ask questions. All participants signed a consent form at the start of the focus group session. The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen confirmed that their official approval was not required, as the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) did not apply to this study (METc 2017/486, M17.218841).

Results

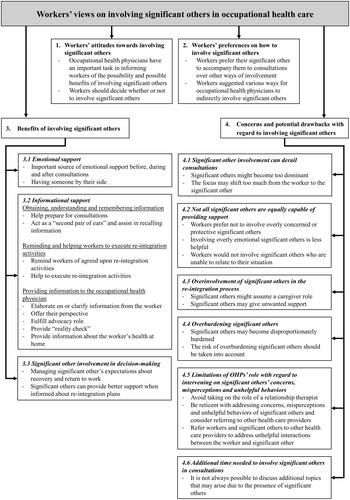

With regard to the perspectives of workers on involving SOs in occupational health care, we distinguished the following main themes: (i) attitudes towards involving SOs, (ii) preferences on how to involve SOs, (iii) benefits of involving SOs, and (iv) concerns and potential drawbacks with regard to involving SOs. These themes and their subthemes are presented in and will be discussed in more detail in the four main sections below.

Figure 1. Overview of themes and subthemes. .

Workers’ attitudes toward involving SOs

Participants generally expressed positive views when asked how they felt about involving SOs in occupational health care. They would appreciate being offered the opportunity to involve their SOs, although their personal preferences varied with regard to this involvement. Workers felt that OHPs have an important task in informing workers of this possibility and explaining its potential benefits, after which the worker should decide whether or not to use this opportunity. One worker explained:

Do you know what I would like best? If they would ask people at the beginning, and that you can just say yes or no. Because look, I can imagine that you might not feel the need at all. That you think like… I also hear you [other participants] say that sometimes you just prefer to do it alone. I recognize that too (M8, 42 years, experience with partner involvement).

Workers’ preferences on how to involve SOs

When involving SOs, most workers would prefer their SO to accompany them to consultations with the OHP. However, if this is not feasible, for example due to SOs’ other obligations, workers indicated that SOs can be involved in other ways, such as using video conferencing to enable SOs to participate in consultations. Workers also suggested various ways for OHPs to involve SOs indirectly: by having SOs fill out a short form with questions at home, by advising workers to discuss certain topics with their SOs, or by providing workers with information to discuss with their SOs.

Benefits of involving SOs

Participants mentioned various benefits of involving SOs in occupational health care; these are described below.

Emotional support

Workers stated that SOs could be an important source of emotional support before, during and after consultations with the OHP. They noted that the presence of a SO during consultations could be reassuring and reduce worries one might have about visiting an OHP, as having someone by their side can provide a sense of security. Furthermore, workers felt that the importance of emotional support is amplified when workers are particularly anxious or distressed about visiting the OHP. One worker said,

And when I talk to my fellow patients [about visiting the OHP], they often feel (…) enormous agitation. And I think the moment that you add a significant other, in a conversation like that alone … that that … uh . yes, can give a huge boost (F7, 47 years, no experience with SO involvement).

Informational support

Many workers stated that SOs could provide various kinds of informational support during the re-integration process (i.e., before, during and after consultations with the OHP). They described that SOs could help them obtain, understand, and remember important information, but they could also help with providing information to the OHP.

Obtaining, understanding and remembering information

Workers described how their SOs had helped them prepare for consultations by talking about questions and issues that were important to discuss with the OHP. They also appreciated their SOs’ help with raising these issues during the consultation. One worker recalled,

Then I think before [the consultation]: ‘write it down, and then when you see that doctor, you can say it’. [But then I think:] ‘that is nonsense, I will remember it'. But then you sit there and then you really don't remember it. Because that man [doctor] starts talking about this, you start talking about that, and he asks about something else, and then you're done again. And… my wife is like, if she were there, she would remember it and she would say 'you wanted to ask that and that and that' (M9, 58 years, experience with partner involvement).

Some workers also mentioned that SOs could act as a “second pair of ears”. Workers indicated that SOs would be able to assist in recalling information provided by the OHP after the consultation had finished. In this context, workers explained that the worker and SO could supplement each other’s recalled information, as each person might have remembered different aspects of the consultation or interpreted information differently. One worker said,

Yes, if someone does indeed come with you (…) you could then talk about that together [after the consultation], like 'gosh, we did talk about it, but how would we do it again?’ (F4, 48 years, unknown whether the participant had experience with SO involvement).

Another worker stated,

It has simply been proven that with every conversation you have, a somewhat longer conversation, you may only really remember 20–30% [of what has been discussed]. And if you have someone with you, they may remember just that other 30% (M4, 61 years, unknown whether the participant had experience with SO involvement).

Someone else explained,

And precisely because we were with the three of us [worker, wife and OHP] every time, those conversations were useful. Because I always only heard that she [OHP] said: 'Well your reintegration to your own work'. … And my wife then said, 'Yes, but she did also say that this will take a year'. And then I think 'Oh yes, that's also true' (M5, 61 years, experience with partner involvement).

Such informational support appeared to be especially important for workers who felt unable to remember questions they wanted to ask, or absorb information given during the consultation. A worker recalled,

… That he [significant other], for example, says what you have to do, or what new appointments have to be made, that sort of thing. [Or] information that you should receive from the OHP that I just couldn't remember myself. My partner then remembered that [for me]. And then I don't have to do that myself. Because I couldn't do that at all at the time (F1, 57 years, experience with partner involvement).

Reminding and helping workers to execute re-integration activities

Aside from recalling and discussing information after consultations, workers felt that SOs could support them by reminding them of agreed upon re-integration activities or helping them to execute these activities. One worker remarked,

Yes, and then my wife is an extension of the OHP. Because if I don't feel like doing anything in the morning, then I get a kick [from her] and she says 'You have to walk for an hour', and then she does, when she's home, she puts on her shoes and then we go walk together (M5, 61 years, experience with partner involvement).

Providing information to the OHP

Another observation was that SOs can help workers to provide information to the OHP. Although workers felt that they themselves should always remain the main source of information, they stated that SOs could elaborate on or clarify this information. Furthermore, they can offer their perspective on the worker’s functioning at home, for example, regarding the worker’s energy level during the day, or the amount of time needed to recover after a workday. In this context, SOs can also fulfill an advocacy role during consultations, to defend workers’ rights and ensure that their best interests are being served. One worker stated:

But a significant other is also very capable to emphasize what the consequences are. That if you've done something, worked or whatever, that you can't do anything anymore during the weekend (F3, 58 years, no experience with SO involvement).

Some workers also mentioned that SOs could ensure that workers provided accurate or relevant information, and that information from SOs can serve as a “reality check”. One worker explained:

You always pretend to be bigger than you are, and to… to nuance that a bit in shades of gray… Of course, you are good at mentioning your good sides… but the less positive sides [difficulties, health complaints] … you just don't mention them. Period. You're not going to talk about that. Come on! But a significant other can shed more light on that. Not to discredit you, but to add nuances [to what you tell the OHP] (M10, 63 years, unknown whether the participant had experience with SO involvement).

However, some controversy arose about having SOs fulfill this role, as it could trigger frustration or anger in the worker. One worker explained that he had initially been furious when his wife had told the OHP that he was not able to do everything he used to do, but that he later recognized that she was right in telling this, and he appreciated her having done it. Other workers stated that they would not appreciate having their SOs provide a reality check during a consultation with their OHP, and that this could be a reason not to bring their SO.

Finally, workers felt that an SO could provide information about the worker’s health at home. One worker said,

Yes, and thát is what your significant other can tell, like, well, ‘when you come home, you don't do anything at all anymore, you are exhausted, barely approachable'. Look, and that is information that the significant other provides and not the patient himself. Because he [patient] wants to work and says ‘yes, but I’m fine’ (F3, 58 years, no experience with SO involvement).

So involvement in decision-making

Some workers stated that it could be beneficial to involve SOs in making decisions regarding re-integration goals and how to achieve these goals. They felt that this could help in managing SOs’ expectations with regard to the expected duration and different stages of the re-integration process. Furthermore, it might make SOs more supportive of re-integration plans and better aware of why certain decisions or recommendations had been made. Another observation was that SOs will be better able to provide support outside of consultations when they are informed about the re-integration plans. In this context, some workers felt that it would be helpful to discuss explicitly what SOs could do to support the worker, or how the worker and SO could work together to deal with the disease, execute plans, and achieve re-integration goals. One worker said,

I can imagine that in some situations it is very pleasant to actually involve the partner, or the person who is present, actively in the conversation. Because perhaps, (…) such a partner can also be actively involved in a bit of the reintegration, or in a bit of guidance during such a disease process. So that agreements can also be made or proposals can be made like, 'Indeed, go walk for an hour with your wife', but that that opportunity is also discussed. Or… discussing ways on how you can proceed together (M6, 56 years, unknown whether the participant had experience with SO involvement).

Concerns and potential drawbacks with regard to involving SOs

In spite of the perceived benefits of involving SOs in occupational health care, some workers also expressed concerns and potential drawbacks regarding the issue. These concerns and potential drawbacks are described below. According to workers, it is important that OHPs, workers and SOs balance the potential benefits and drawbacks of SO involvement.

So involvement can derail consultations

Some workers were concerned that the presence of SOs might negatively affect the interaction between the worker and the OHP. SOs might become too dominant in the consultation, at the expense of the worker’s involvement. Furthermore, workers expressed concern that the focus may shift too much from the worker to the SO. They indicated that situations could arise in which OHPs engaged primarily with the SO during consultations, at the expense of the worker. One worker said,

(…) someone sitting next to you should not take over the conversation (F5, 55 years, experience with involving a good acquaintance).

Workers felt that OHPs have an important task in balancing the benefits of actively involving SOs and the potential negative effects this can have on the consultation and interaction with the worker. For example, although workers felt it was important for OHPs to recognize misperceptions, anxiety and concerns on the part of SOs, they stressed that the consultation should always remain focused on supporting the worker’s return to work.

Not all SOs are equally capable of providing support

Participants also felt that not all SOs were equally capable of providing support during the re-integration process. Several workers noted that they preferred not to involve a SO who was overly concerned or protective. One worker explained,

I wouldn't take anyone with me who is overprotective. Because when this happens, you have the chance that, if you are in a rehabilitation period, that this might have an inhibiting effect. And you don’t want that either. You do want to move forward (M6, 56 years, unknown whether the participant had experience with SO involvement).

In addition, SOs who were likely to become overly emotional during a consultation were considered less helpful. Someone said,

(…) If I had had my father there, he would have dragged that man across the table. Well, you don’t want that, I'm afraid (M3, 49 years, no experience with SO involvement).

Some workers also indicated that they would not involve SOs who were unable to relate to their situation. One explained,

And especially my daughter, who is also unemployed at the moment, doesn't understand. She says 'You get your money easily'. So, when I talk about that, yes, what my motive is [to work from home two days a week], yes, that does not come across (M14, 62 years, unknown whether the participant had experience with SO involvement).

Overinvolvement of SOs in the re-integration process

Workers spoke of the risk that SOs could become overinvolved in the re-integration process. Several workers expressed the concern that SOs might assume a caregiver role, and try to assume part of the control over the worker’s life. Furthermore, SOs may give unwanted support or start to act as a surrogate for the OHP at home. Although well-intended, this could cause the worker frustration, and lead to conflict. A worker explained,

Yes, what I am always a bit afraid of, and I do also say that [to my wife]: 'Yes I married you, but I am not married to a caregiver', you know. That is awfully essential. I do want help from her, but yeah … yeah, also not too much, you know. It's a bit … otherwise you are so dependent, right? (M8, 42 years, experience with partner involvement).

Overburdening SOs

Workers explained that their disease had consequences not only for themselves, but also for their SOs, and that they did not want to burden them more than necessary. They stressed the importance of preventing SOs from becoming overburdened, and of not losing sight of how the disease affected the SOs. One worker explained that by involving them, SOs may become disproportionately burdened:

And if you as an OHP say, 'We want to have the partner there to allow the person who is ill to re-integrate', then you have to realize that you can really disproportionally burden the partner. With all the love that everyone has for their own partner, that you think like ‘yes, but they [partner] will pay the bill twice’. I would also watch out for that (M5, 61 years, experience with partner involvement).

There was consensus that the risk of overburdening SOs should be taken into account when considering whether, when, and how to involve them in occupational health care.

Limitations of OHPs’ role with regard to intervening on significant others’ concerns, misperceptions and unhelpful behaviors

Although workers were generally positive about involving SOs in occupational health care, opinions differed on what this involvement should entail and what topics the OHP should address with the worker and SO. More specifically, some controversy arose about whether it would be appropriate for OHPs to address cognitions and behaviors of SOs, and interactions between the worker and SO, that seemed to hinder the worker’s coping and re-integration process. Some workers felt that OHPs could to some extent address concerns, misperceptions about the illness and behavior of SOs, if it were to contribute to the worker’s re-integration process. One worker stated,

Yes if it helps, if he [OHP] can provide information so that the partner or the accompanying person gains a better understanding and is better able to help, and this indeed helps towards the main goal [of return to work], then I certainly think it can help (F4, 48 years, unknown whether the participant had experience with SO involvement).

However, others firmly stated that such issues should not be addressed by OHPs, but rather be discussed with other health care providers (e.g., a psychologist or medical specialist) or someone from a patient organization. Similarly, some workers allowed that OHPs might, to a limited extent, try to facilitate positive interactions between the worker and SO, while others felt that this was not the OHP’s responsibility. One worker said,

But the OHP you know, and conveying that overprotectiveness, yes then I would like, if he [OHP] would also say something like, 'listen, also trust him [the worker] a bit' (M7, 54 years, experience with partner involvement).

Although opinions differed regarding which topics the OHP could address, workers agreed that OHPs should avoid taking on the role of a relationship therapist. About this, one worker said,

And whether we have marital problems or not, the OHP doesn't have to go fishing about that. Because I choose to bring someone that I trust at that moment. (…) But it's not my therapist, that OHP (M5, 61 years, experience with partner involvement).

Overall, most workers felt that when issues surrounding SOs’ concerns, misperceptions, behavior, or interactions appeared to hinder the worker in his or her coping and re-integration, it would be better to refer workers and SOs to other appropriate health care providers or a patient organization.

Additional time needed to involve SOs during consultations

Some workers expressed doubts as to whether sufficient time is available during consultations to actively involve SOs in the conversation, for example to provide them with additional information or ask about their perspective. Workers had had different experiences with the duration of consultations, with available time ranging from ten minutes up to an hour. Consultations with a duration of ten minutes were considered too short for discussing additional topics that could arise because of the presence of SOs. However, some workers stated that OHPs could easily schedule an additional or double appointment to allow for more time. One worker said,

Perhaps you could include that in the protocol, like 'Instead of having a standard consultation of ten minutes, schedule, for example, half an hour for those people [workers who take a significant other with them]' (F2, 53 years, unknown whether the participant had experience with SO involvement).

Discussion

In this focus group study, we aimed to better understand how workers with chronic diseases feel about involving their SOs in occupational health care, and how this should be implemented to best meet their needs. The workers participating in this study reported that SOs can play an important role in supporting workers with chronic diseases in the re-integration process, both in daily life and during consultations. They generally had positive views about involving SOs in occupational health care, and felt that this can benefit the work re-integration process. Although their personal preferences regarding its implementation varied, most said they would appreciate the opportunity to involve their SOs. They indicated that benefits of involving SOs are that they can provide emotional and informational support (e.g., reducing anxiety, and providing and recalling information) before, during, and after consultations with the OHP. Moreover, they felt that involving SOs in decision-making could help workers to better manage their expectations about recovery and return to work; a well-informed SO could better support the worker’s re-integration plans.

Nevertheless, aside from identifying the potential benefits of involving SOs in occupational health care, workers also expressed some concerns and potential drawbacks. Some pointed out that the presence of SOs could derail the consultation, negatively affecting the interaction between the worker and the OHP. Others were concerned that SOs might assume a caregiver role, give unwanted support, or become overburdened. Still others mentioned that the limited time available during consultations could also present challenges for actively involving SOs. Finally, opinions differed on what involving SOs should entail, and what topics should be addressed by the OHP. For example, when issues surrounding SOs’ concerns, misperceptions, or interactions were likely to hinder the worker in his or her coping and re-integration, most workers felt that it would be better to refer workers and SOs to other appropriate health care providers or a patient organization.

Our findings are largely in line with clinical studies exploring how individuals with a chronic disease view involvement of SOs in medical consultations. Some of these studies also found that patients generally hold favorable views towards involvement of a spouse, family member or friend [Citation21,Citation29]. Moreover, other studies confirm that SOs can offer important emotional and informational support before, during, and after consultations [Citation20,Citation21,Citation30]. Prior studies also confirm our finding that the involvement of SOs can present some challenges, such as their overinvolvement, and possibly needing extra time during consultations [Citation29–31].

However, our findings differ in some respects from those of other clinical studies. In our study, we found that most workers were less inclined to involve unsupportive or overprotective SOs, as they felt that this could hinder the re-integration process. In contrast, prior research indicated that it could be helpful to involve unsupportive SOs in health care interventions, as this could enhance support, helpful behaviors, effective communication, and joint problem solving [Citation20,Citation32], which could in turn lead to better health, relationships and work outcomes [Citation4,Citation20,Citation30,Citation33]. This difference may in part be explained by the view of workers in our study that enhancing support by SOs is not among the core tasks of OHPs, and could be better addressed by other health professionals with more expertise in counseling people on interpersonal matters. The position of OHPs in the health care system may also play a role in this matter. For instance, in the Netherlands, since 1994 occupational health services (OHS) have been provided by commercial enterprises, with the market dominated by a few major organizations [Citation34]. Most OHS employ OHPs and other occupational health experts. Employers are legally obliged to contract an OHP to assist them in guiding sick employees during the first two years of sick leave. OHPs providing support and guidance to help employees retain or return to work are thus hired by employers, which has led to discussions about their independence and impartiality. In this context, OHPs are often seen by employees as acting mostly on behalf of the employer, whose best interest is to have sick-listed employees return to work as quickly as possible, rather than as care providers whose task it is to protect and promote the health of employees in relation to their work, and to support sick-listed employees in their recovery and re-integration process. This perception could in turn influence workers’ views on the role of OHPs in eliciting support from SOs. Our findings regarding the benefits and reasons for involving SOs in occupational health care strongly resemble findings in a prior study on workers’ views about occupational health care consultations with a spouse, family member, or friend present [Citation26]. In both studies, workers mentioned emotional support as an important reason to bring someone to consultations, and indicated that having an SO present can be helpful for recalling information and providing extra information to the physician. Furthermore, as in our study, workers in that study mentioned that the presence of their SO at the consultation enabled them to discuss its outcomes afterwards [Citation26].

When comparing views on involving SOs in occupational health care of workers in our study with those of OHPs [Citation23,Citation26], we found both similarities and discrepancies. Both workers and OHPs highlighted that SOs can play an important role in providing OHPs with greater insight into a worker’s illness and functioning. Both stakeholders also agreed that it is not always necessary to involve SOs in occupational health care, mentioning that the necessity and benefits of such involvement depend on factors such as the worker’s coping, capability to provide sufficient information, and disease characteristics [Citation23]. In addition, both workers interviewed in this study and OHPs participating in other studies [Citation23,Citation26] indicated that the characteristics of SOs should be taken into account when deciding whether or not to involve someone. For example, some workers and OHPs [Citation23] indicated that they would not involve an overprotective SO, as they felt that this might hinder the worker’s re-integration process or disrupt consultations.

There were, however, some discrepancies between the views of workers and those of OHPs. For instance, to some extent workers and OHPs gave different reasons to involve SOs. Workers in this study emphasized mainly practical reasons for wanting to involve SOs, such as reducing their own anxiety about visiting the OHP, and having support in recalling and providing information. In contrast, in a prior survey study, one of the main reasons OHPs gave for involving SOs was to gain more insight into the social context of the worker, and the influence of SOs on the worker’s coping, recovery, and re-integration process [Citation23]. Furthermore, OHPs in that study indicated involving SOs not only to mobilize their support, but also to be able to intervene when SOs’ cognitions and behaviors appear to be an obstacle. While some workers in our study also indicated that OHPs might, to a limited extent, address hindering cognitions and behaviors of SOs when this would benefit the return to work process, they generally felt that OHPs should show restraint in intervening on such cognitions and behaviors. This difference in opinions between workers and OHPs may in part be explained by the way the role of OHPs is regulated in the Netherlands. Discussion regarding the independence of OHPs strikes at the core of the physician-patient relationship, namely trust. Patients must trust their physicians to work in their best interests to achieve optimal health and functioning outcomes. In addition, SO involvement in occupational health care means that SOs are involved not just in the worker’s health, but also in the worker’s work context. Therefore, privacy concerns of workers might also be an issue and influence their views on what topics should be addressed when involving SOs. This is especially so when SOs assume an active role in providing information to the OHP, which could in turn affect the worker’s return to work. In this context, our findings indicate that the workers interviewed in this study generally felt that the OHP’s role in supporting recovery and re-integration is limited to addressing topics directly related to the worker and his/her work. While concerns about the worker’s privacy can be a reason for OHPs to be reticent in addressing topics that are not directly related to the worker and his/her work, there is also some evidence that OHPs feel that their role does include addressing environmental factors outside of work that hinder the worker’s recovery and re-integration [Citation23].

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the diversity of our sample with regard to chronic diseases, age, sex, duration of sick leave, work status, and experience with involving SOs. This resulted in a wide range of views and considerations regarding involving SOs in occupational health care. Furthermore, we used an iterative data collection approach, which allowed us to better explore new topics that were introduced in previous sessions.

A limitation of our study is that we were unable to perform purposive sampling. In addition, there is some risk of selection bias due to our recruitment method and relatively small study sample. While there was sufficient diversity in our sample with regard to experience with SO involvement and most worker characteristics, low-educated workers were underrepresented. Prior research indicates that workers with a lower educational level may experience more difficulties in managing their disease than workers with a higher education [Citation21]. In addition, lower educated workers are more likely to have low health literacy, which can negatively impact physician-patient interaction, chronic disease self-management and patient outcomes [Citation35–37]. As lower educated workers may need more or different types of support from their SOs to effectively interact with physicians and manage their disease, their preferences with regard to involving them in the re-integration process may differ from those of workers with a higher educational level. The underrepresentation of workers with a low educational level might have been prevented by taking additional measures aimed at ensuring an even representation of workers across educational levels, which may in turn have resulted in additional themes. Another limitation of this study is that it is unknown for some participants whether they had any experience with involving significant others in occupational health care. This information could have provided more insight into the standpoint from which these participants spoke and whether views and considerations might differ depending on workers’ personal experience with SO involvement. Finally, the third focus group consisted of only two participants, due to a last-minute drop out and difficulties in recruiting more participants for this session. Nevertheless, a benefit of the small size of this particular group was that it allowed us to go into more detail and discuss each participant’s thoughts, experiences and opinions more extensively than in the other sessions.

Implications and recommendations for occupational health practice

This study provided valuable insight into workers’ views on involving SOs in occupational health care, as well as a number of practical implications. First, most participating workers believed that their involvement in the re-integration process can facilitate a helpful role of SOs, which in turn can help workers in their recovery and return to work. In this context, OHPs may inform SOs about the return to work plan, involve them in decision-making, and explicitly discuss with workers and SOs what the SO can do to support the worker. Furthermore, they may consider intervening on concerns, misperceptions and unhelpful behaviors of SOs in order to reduce a hindering role of SOs, either by providing information and advice or referring workers and SOs to other health care professionals. However, according to workers, potential drawbacks of SO involvement need to be taken into account, including risks of overburdening SOs and SOs interfering too much during consultations or providing unwanted support. In this context, it is important that OHPs, workers and SOs balance the potential benefits and drawbacks of involving SOs in the re-integration process. Moreover, OHPs and workers should take the worker’s self-management skills, preferences and needs and characteristics of SOs into account when deciding whether to involve SOs, as well as which SO to involve. Finally, as many workers had never considered the possibility of involving their SOs, they felt that OHPs have an important role in creating more awareness among workers of the possibility and potential benefits of involving SOs in occupational health care. These insights are helpful in developing guidelines and education for OHPs on how to manage involvement of SOs in occupational health care.

Recommendations for future research

This study and prior research have focused on the views of workers and OHPs regarding involving SOs in occupational health care. However, knowledge of the views of the SOs themselves on this topic is still lacking. Future research should therefore aim at gaining insight into how the SOs perceive their involvement in the re-integration process. Such research may result in additional considerations and recommendations that are important for successful implementation of SO involvement in occupational health care. In addition, future research should focus on gaining more fundamental insight into dyadic processes of workers and SOs (e.g., the ways they cope with stress together) that can influence the recovery and re-integration process of sick-listed workers. As our research indicates that workers have varying preferences regarding the role of SOs in consultations and the re-integration process, future studies could focus on exploring how workers and SOs can best negotiate this role. In addition, more research is needed to determine whether these dyadic processes and the benefits and drawbacks of SO involvement depend on which SO is involved and whether or not the worker and SO live together. Finally, future research is needed to determine the size of effects, both positive and negative, of involving SOs on recovery and successful return to work of workers with a chronic disease. In this context, it is important to also explore whether worker characteristics such as gender, illness severity and self-management skills influence the effects of SO involvement.

Conclusion

The workers participating in this study were generally positive about the possibility to involve SOs in occupational health care, believing that involving SOs can contribute to recovery and work re-integration of workers with a chronic disease. They felt that an important benefit of such involvement is that SOs can provide emotional and informational support before, during, and after consultations. However, they also indicated that the circumstances and preferences of the worker should be taken into account when deciding whether and how to involve SOs, and that care should be taken that SOs do not become overinvolved or overburdened.

Ethical approval

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen confirmed that official approval by this committee was not required, as the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) did not apply to this study (METc 2017/486, M17.218841).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Author Contributions

NS, HdV, SvdBV, SB and MH contributed to the conception and design of the study. NS and HdV developed the interview guide and invitation letter; SvdBV, SB and MH reviewed the content. NS and HdV performed the data collection; NS and AB performed the data analyses; and NS drafted the manuscript. All authors have contributed to critical revision of the main intellectual content of the manuscript, and have approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Margriet van Kampenhout for her contribution to the data collection. We would also like to thank the 15 occupational health physicians of HumanTotalCare and the Patient panel of the Netherlands Patients Federation for their contribution to the recruitment of participants. Finally, the authors thank all workers who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

Drs. Snippen, Dr. de Vries, and Prof. dr. Brouwer received grants from Instituut Gak to conduct the study; Drs. Bosma, Prof. dr. van der Burg-Vermeulen and Prof. dr. Hagedoorn have nothing to disclose.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to identifying information, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- European Chronic Disease Alliance. Joint Statement on “Improving the employment of people with chronic diseases in Europe”. 2017. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/policies/docs/2017_chronic_framingdoc_en.pdf

- OECD/EU. Health at a Glance: Europe 2016 - State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD Publishing. 2016. DOI: 10.1787/9789264265592-en

- Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(6):920–954.

- Snippen NC, Vries H. D, Burg-Vermeulen S. V D, et al. Influence of significant others on work participation of individuals with chronic diseases: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e021742

- Rosland A-MM, Heisler M, Piette JD. The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: a systematic review. J Behav Med. 2012;35(2):221–239.

- Deek H, Hamilton S, Brown N, et al.; FAMILY Project Investigators. Family-centred approaches to healthcare interventions in chronic diseases in adults: a quantitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(5):968–979.

- Islam T, Dahlui M, Majid HA, et al.; MyBCC study group. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(S3):1–13.

- Brooks J, McCluskey S, King N, et al. Illness perceptions in the context of differing work participation outcomes: Exploring the influence of significant others in persistent back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:48.

- Martire L, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, et al. Review and Meta-analysis of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(3):325–342.

- Hartmann M, Bäzner E, Wild B, et al. Effects of interventions involving the family in the treatment of adult patients with chronic physical diseases: a Meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(3):136–148.

- Kelly GR, Scott JE, Mamon J. Medication compliance and health education among outpatients with chronic mental disorders. Med Care. 1990;28(12):1181–1197.

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook S, et al. A randomized trial of individual and couple behavioral alcohol treatment for women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(2):243–256.

- Vooijs M, van der Heide I, Leensen MCJ, et al. Richtlijn Chronisch Zieken en Werk [Guideline ’The chronically ill and work’]. Amsterdam; 2016. Available from: https://www.psynip.nl/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Richtlijn_chronisch_zieken_en_werk_2016.pdf

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of chronic pain. A national clinical guideline. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2019. Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1108/sign136_2019.pdf

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Brain injury rehabilitation in adults. A national clinical guideline. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2013. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign130.pdf

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Stroke rehabilitation in adults. Clinical guideline [CG162]. NICE; 2013;1:44. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg162/resources/stroke-rehabilitation-in-adults-pdf-35109688408261

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression in Adults: recognition and Management. Clinical guideline [CG90]. Natl Collab Cent Ment Heal. 2009. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90/resources/depression-in-adults-recognition-and-management-975742636741

- Centre for Clinical Practice at NICE (UK). Rehabilitation after critical illness. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2009.

- van Dijk JL, Bekedam Ma Brouwer W, et al. Richtlijn Ischemische Hartziekten [Guideline Ischemic Heart Disease]. Utrecht. 2007 [cited 2019 Feb 21]. Available from: www.nvab-online.nl

- Lamore K, Montalescot L, Untas A. Treatment decision-making in chronic diseases: what are the family members' roles, needs and attitudes? A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(12):2172–2181.

- Laidsaar-Powell RC, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. Physician-patient-companion communication and decision-making: a systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(1):3–13.

- Meis LA, Griffin JM, Greer N, et al. Couple and family involvement in adult mental health treatment: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(2):275–286.

- Snippen NC, de Vries HJ, de Wit M, et al. Assessing significant others’ cognitions and behavioral responses in occupational health care for workers with a chronic disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;43(19):2690–2703.

- Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, et al. The person-based approach to intervention development: Application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(1):e30.

- Gupta K, Lee H. A practical guide to needs assessment. Perform Improv. 2001;40(8):40–42.

- Sharp RJ, Hobson J. Patient and physician views of accompanied consultations in occupational health. Occup Med. 2016;66(8):643–648.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Bu S, et al. Attitudes and experiences of family involvement in cancer consultations: a qualitative exploration of patient and family member perspectives. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(10):4131–4140.

- Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: a Meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):823–831.

- Hobson J, Hobson H, Sharp R. Accompanied consultations in occupational health. OCCMED. 2016;66(3):238–240.

- Manne S, Ostroff JS, Winkel G. Social-Cognitive processes as moderators of a Couple-Focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Heal Psychol Published. 2007;26(6):735–744.

- Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, et al. Partner-assisted emotional disclosure for patients with gastrointestinal cancer: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2009;115(S18):4326–4338.

- Burdorf A, Elders L. Occupational medicine in The Netherlands. Occup Med. 2010;60(4):314–314.

- Davey J, Holden CA, Smith BJ. The correlates of chronic disease-related health literacy and its components among men: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):589.

- Sim D, Yuan SE, Yun JH. Health literacy and physician-patient communication: a review of the literature. Int J Commun Heal. 2016;10:101–114.

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;155(2):97–107.