Abstract

Purpose

Adults with acquired neurological disability often require paid disability support to live an ordinary life. However, little is known about what facilitates quality support. This study aims to explore the lived experience of people with acquired neurological disability to develop an understanding of the factors that influence the quality of support.

Methods

Guided by constructivist grounded theory, in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with 12 adults with acquired neurological disability. Data analysis followed an iterative process to develop themes and subthemes and explore relations between themes to build a model of quality support.

Results

Nine key factors emerged in the dyadic space, with the support worker recognising the person as an individual as foundational to quality support. Beyond the dyadic space, three broader contextual factors were identified as influential on the quality of support by mechanism of facilitating or constraining the person with disability’s choice. Finally, the provision of quality support was characterised by the person feeling in control.

Conclusions

Findings support the rights of people with disability to quality, individualised support, and a need for interventions to better prepare the disability workforce to deliver support in line with the needs and preferences of people with acquired neurological disability.

To provide quality support, disability support workers need to recognise the person with disability as an individual and the expert in their support needs and preferences.

The quality of paid disability support is primarily determined by the way the person with disability and support worker work together in the dyadic space.

Ensuring people with acquired neurological disability have authentic choice over their support arrangements and daily living is critical to facilitate quality support, and in turn help the person with disability to feel in control.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Globally, around 650 million people are living with a disability [Citation1]. A significant number of these people have neurological disabilities due to a range of developmental conditions or disorders acquired as the result of illness or injury. According to prevalence data, at least 5% of people in Australia [Citation2] and the USA [Citation3] have some form of cognitive impairment due to developmental or neurological disability and are likely to require support to live and fully participate in the community, and to realise the full spectrum of human rights [Citation4,Citation5]. Yet, the support needs of most persons with disabilities worldwide are not being met as their needs have generated relatively little public and political interest [Citation6]. This research focuses on paid support for adults with acquired neurological disability (i.e., traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, stroke, multiple sclerosis) who experience a range of cognitive, communication and physical impairments, and require support to live an ordinary life.

Paid support is primarily provided by a disability support worker. The support worker role is to support and build the capacity of people with disability to make their own lifestyle choices, participate in the community and achieve their self-described goals [Citation7–9]. The role involves providing support across a range of activities, including daily and domestic living tasks, employment, housing and community participation [Citation10–12]. Support workers work in numerous environments, including the person’s home, the community, day services, shared supported accommodation and residential aged care [Citation11–14]. There are multiple employment arrangements for support workers (i.e., directly employed by the person with disability or employed via a service or housing provider) [Citation11,Citation14,Citation15]. As such, it is a variable and complex role yet training opportunities for this workforce continue to be inadequate [Citation14,Citation15]. Indeed, a recent study found support workers themselves considered that lack of knowledge about disability amongst their peers negatively impacted the quality of support received by people with disabilities and potentially contributed to abuse and neglect [Citation16].

Over the past decade, an international shift towards individualised funding and person-centred approaches in disability support provision has occurred [Citation17,Citation18]. In Australia, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was introduced in 2013 with the aim to increase choice and control for people with disability by providing access to tailored support packages [Citation19]. Although in theory this shift is promising, under individualised funding schemes, the support workforce has become increasingly casualised with limited institutional structure. This change combined with few formal requirements to be a support worker, results in high turnover of workers who are often undertrained and under supported [Citation14,Citation20,Citation21]. In addition, evidence suggests an increased risk of support worker stress and burnout [Citation22], as well as ongoing safeguarding concerns for people with disability [Citation23]. Further, the introduction of the NDIS has called for a substantial increase in the disability workforce, and in turn, there has been a vast increase in workers with limited disability experience or education [Citation24]. Moreover, whilst the NDIS committed to spend $24.2 billion in disability support in 2019–20 [Citation25], the pricing structures do not incorporate sufficient training or development opportunities [Citation26]. This training void is especially problematic as individualised support arguably requires a broader range of skills [Citation15,Citation21], and being skilled, having ongoing training opportunities and good work conditions have been shown to be critical for quality support [Citation20]. Further, limited guidance is available for people with disability around what quality support looks like, and how to build quality support teams. Thus, although people can choose and purchase supports, the lack of guidance combined with the variability of the workforce, hinders the rights of people with disability to access quality support.

Available evidence on support for people with acquired neurological disability suggests that quality support is determined by a complex mix of interrelated factors [Citation27]. In line with individualised funding schemes, studies suggest people with neurological disability want agency over their support arrangements [Citation28–30] and to be involved in daily decision making [Citation31]. Correspondingly, research highlights the importance of person-centred individualised approaches to support [Citation31–33]. To do this effectively, support workers need to be willing to listen and learn [Citation31,Citation32,Citation34–36], demonstrate empathy and respect [Citation30–32,Citation34,Citation36], and be competent in relevant skills [Citation30,Citation31,Citation35]. Further, data from several studies suggest that the relationship between the person and their support worker plays a key role in the quality of support [Citation13,Citation23,Citation28–32,Citation34–37]. In addition, Robinson et al. [Citation38] highlighted the role of the relationship in maintaining safety and minimising harm to people with disability. Whilst intuitively the relationship is influenced by the support worker and the person with disability, corresponding with expert insights in our scoping review [Citation27], recent research indicates that organisational policies can facilitate or constrain the support relationship [Citation13,Citation39]. Finally, research suggests that access to consistent support acts as a precursor of quality support, as continuity of support facilitates a better relationship [Citation29,Citation32–35,Citation37].

Despite the available evidence, few studies have directly investigated the factors that influence the quality of support from the perspective of adults with acquired neurological disability. To better conceptualise quality support, it is vital to understand the lived experience of people receiving paid support and what they want in a support worker. With this understanding, we will be better equipped to improve the quality of support in line with the needs and preferences of people with acquired neurological disability. Further, understanding the support experience for people with neurological disability can inform ways of maintaining safety and reducing risk for this population. Accordingly, this study is the first in a series of studies to develop a holistic understanding of quality support, grounded in the lived experience of people with acquired neurological disability, close others (i.e., family, friends, partners) and support workers. In line with a person-centred approach, this study aims to obtain the perspective of people with acquired neurological disability on the factors that influence the quality of support.

Method

Study design

Given the study aim and the relational nature of support, a constructivist grounded theory method was chosen to capture the experiences and perspectives of adults with acquired neurological disability [Citation40]. Constructivist grounded theory lends itself to exploring research questions about which little is known, as is the case for paid support for this population. Given its roots in symbolic interactionism [Citation41], grounded theory is well suited to exploring experiences that take place in an interactional space like that of support. This method accommodates an inductive, non-linear approach to data collection and analysis, allowing researchers to be flexible when interviewing to generate rich data reflecting the participants’ lived experience. A constructivist grounded theory method recognises the influence of interaction between the researcher and the participant, as well as the researcher’s preconceptions, on the generation and interpretation of data. Thus, subsequent theory generation is seen as a construction between the participants and the researcher.

Participant recruitment

Institutional approval was obtained from the University Human Ethics Committee (HEC20253). All participants provided written informed consent. Recruitment was supported by a non-for-profit advocacy organisation. The organisation did not provide support services. An administrative staff member independent to the research project approached potential participants. Participants had, had previous contact with the organisation (e.g., attending forums, participating in lived experience workshops) and indicated they would be interested in participating in research opportunities. On initial approach, the administrative staff member discussed the eligibility criteria with the participant to ensure they were eligible for participation. Purposive sampling was used to recruit adults with acquired neurological disability who had at least 1-year experience receiving paid support, with attention to variation regarding support set-up and participant age, gender and disability type. Participants were provided with a gift voucher to thank them for their time. Of the invited participants, one refused to participate due to not being interested, and one interested participant became unwell and unable to participate.

Participants

Twelve adults with acquired neurological disability (7 female, 4 male, 1 agender; mean age 46, range 30-mid 60 s) were recruited to the study (see ). A range of disability types were represented (multiple sclerosis = 5; acquired brain injury = 4; stroke = 1; spinal cord injury = 1; other neurological disorder = 1). The participants lived in Australia, in their own home or private rental (8), shared supported accommodation (3) or residential aged care (1). All were receiving support from multiple support workers for an average of 103 h per week (range 39–168). None of the participants received paid support from family members. Participants self-identified as having high support needs, ranging from Level 4 (can be left alone for part of the day and overnight) to Level 7 (cannot be left alone) on the Care and Needs Scale [Citation42]. Eight participants received support from a self-selected service provider, three from a service provider selected by their housing provider and four used online platforms to directly manage their supports. Three participants received support from both a service provider and online platforms. Participants satisfaction with their current support reflected the full range of responses (1–10) on a 10-point scale (mean 6.75).

Table 1. Participants characteristics.

Procedure

In-depth interviews were conducted between November 2020 and June 2021. Participants received written and verbal information about the study and the researcher’s motivations for the study (i.e., the first author’s doctoral research), and were invited to discuss the study with the first author prior to providing consent. Interviews lasted between 30 min and 1.5 h and were conducted at a time convenient to the participant via Zoom videoconferencing (7) or telephone (5). Face-to-face interviews were planned, but because of restrictions imposed due to COVID-19, remote interviews were conducted. As online interviewing with adults with neurological disability was relatively new territory, we conducted a rapid narrative literature review to guide the procedure [Citation43]. Informed by the review, several measures were implemented to ensure the interviews were practically, ethically, and methodologically sound. One such measure involved the researcher contacting participants prior to the interview to have an informal introductory conversation, build rapport and establish a relationship. Overall, the medium by which interviews were conducted did not impact the quality of the data. Additional reflective details of the interview process can be accessed in our case study published by Sage Research Methods [Citation44].

The first author, a female doctoral candidate with a Psychology background and experience conducting research interviews with a range of adults including adults with disability, conducted the interviews. The first author was trained and supported by the second author who is an experienced qualitative researcher with extensive clinical and research experience with adults with acquired neurological disability. Audio recordings of interviews with the first three participants and all subsequent participant transcripts were reviewed by the second author. Interviews followed a semi-structured schedule (see Appendix 1) developed by the authors in consultation with a person with lived experience of disability and paid support. Considering the limited research in this area [Citation27], the interview questions were broad and open-ended to encourage participants to discuss their experiences of paid support, what makes an excellent support worker and other factors that influence the quality of support. The first author conducted the interviews, taking an active, responsive approach, i.e., following leads of enquiry raised by participants, using probes such as “tell me more…” and “can you give an example…,” and non-verbal cues (e.g., nods, facial expressions) to encourage elaboration [Citation45]. Most participants scheduled the interviews when support workers were not present, and participants who had support workers in the home (n = 3) conducted the interview in a separate room. During the interviews, the interviewer took field notes to document observations of participant behaviours, indications of emotions and their environment. No repeat interviews were required.

Data analysis

Data analysis was an iterative process, conducted concurrently with data collection to guide theoretical development. Interviews were audio recorded and a third-party transcription service was engaged to transcribe the interviews verbatim. All interview transcripts were verified as accurate by the first author. Following the interview, the first author reviewed the audio recording and journaled initial thoughts and reflective feelings. Interview transcripts, reflective journal entries and memos were imported into NVivo [Citation46] and analysed in line with Charmaz’s [Citation40] three-stage coding process: initial, focused and axial coding. The first author coded the transcripts, with secondary coding of five transcripts completed by the second author to ensure consistency of coding. The second author reviewed all subsequent coding. Constant comparison was used across all stages of analysis, whereby codes and data within the codes were compared within and between participants to facilitate conceptual abstraction, and in turn, the generation of analytical and conceptual themes that reflected participant experiences of quality support [Citation47]. Diagramming was also employed to aid the development of themes, explore interconnections and provide visual representation of emerging analysis. Throughout the analytical process, in-depth discussion between the three authors provided guidance to the first author regarding the emerging themes and subsequent model. The process of coding and comparison was repeated until saturation was evident and no new themes emerged during analysis of the last four interviews [Citation48]. At this point a consensus decision regarding theoretical sufficiency was reached by the three authors and no further sampling was necessary [Citation49].

Quality

Charmaz’s [Citation40] quality criteria regarding credibility, originality, resonance and usefulness were considered to ensure the rigour of this study. Credibility was achieved through strategies to help the participant feel comfortable sharing authentic information (i.e., rapport building), followed by additional strategies to ensure subsequent data analysis remained grounded in the data (i.e., in-depth documentation of the research process through memos, journal entries, field notes and diagrams). In addition, frequent detailed discussions between the authors, all of whom have different academic and practice backgrounds, provided opportunities for reflexivity and helped reduce the risk of researcher bias. Where discrepancies between authors occurred, transcripts, field notes and memos were referred to, and discussions continued until consensus on the relevant code, theme or relationship was reached. Further, as a data verification strategy, rather than return transcripts to participants for comment, the first author generated a summary of the participant’s contributions and asked the participant to review it and provide feedback on whether it captured their experiences accurately and provide any additional thoughts. Participants engaged in the verification process, with most responding to confirm the accuracy and some also phoning to discuss the summary and emphasise points of importance. This process not only helped with data authenticity, but also added to the richness of the data. In terms of originality, this is the first grounded theory study to directly investigate the quality of paid support for this population. Resonance and usefulness were verified through presentation and discussion with people with lived experience, allied health professionals and academics in local, national and international forums during the research process. Further, to demonstrate the findings are fully grounded in the lived experience, illustrative quotes from the interviews are presented throughout the results. Pseudonyms are used to protect the identity of participants. Finally, the study was conducted and reported in line with the criteria set by the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research [Citation50].

Results

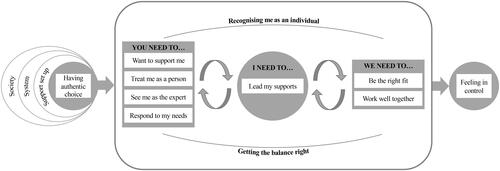

Quality support emerged as a process situated primarily in the dyadic space between the person with disability and the support worker. Within the dyadic space, factors pertaining to what the support worker needs to do (you need to), what the person with disability needs to do (I need to) and what we need to do together (we need to) to achieve quality support were developed. Of most prominence was what the support worker needs to do, with recognising the person as an individual emerging as fundamental to the realisation of all other factors. Further, the support worker needs to want to support the person with disability, treat them as a person, see them as the expert and respond to their needs. In turn, the person with disability can lead their supports. Together, the person with disability and the support worker need to be the right fit and work well together. Lastly, the person with disability and the support worker getting the balance right emerged as a mediating factor relevant to all factors in the dyadic space. Beyond the dyadic space, broader contextual factors influencing the quality of support were identified. Namely, the immediate context within which the support is provided (support arrangements), as well as the systemic and societal context. See for a summary of the themes and subthemes.

Table 2. Themes, subthemes, and codes describing factors that influence the quality of support.

Factors in the dyadic space

You need to…

Recognise me as an individual

The overarching factor reflects the participants’ view that to provide quality, tailored support, the support worker must demonstrate that they recognise the person with disability as an individual. This means seeing them as a person with individual needs and preferences. To illustrate that they recognise the person as an individual, the support worker needs to want to support them, treat them as a person, see them as the expert in their own support needs and respond to their needs.

Want to support me

A consistent thread across participants was the importance of the support worker wanting to support them, rather than “just doing it for the money” (Kelly) or “filling employment” (Isabella). As the role looks different with each person, the support worker must recognise the person as an individual to understand what the role entails, to know if they want to support them. Participants described ways support workers indicate that they want to support them, such as “being interested in helping [me], someone who asks a lot of questions” (Tony) or asking for feedback.

If they’re very curt you can pick up that they don’t want to work here, that’s difficult… they’re just doing it for the money. Kelly

He came to me and said, “have you got any feedback for me on how I’m doing and how I can do better?” Lauren

Participants emphasised the importance of support workers having a “happy disposition and be[ing] happy to do things to help you” (Charlie). As Paula captured, she wants support workers “to begin with a smile and show that they care, it’s not just a job is most important to me.” Correspondingly, participants assumed the support worker did not want to be there when they complained about the burdensome nature of the role or their personal issues.

If you don’t wanna be here, see you later… when they come in saying about how tired they are or things about home, I don’t wanna hear it. Sarah

I’m sorry if he’s had a bad day, but he needs to leave it at the door and when he comes in here, he’s with me. Ashley

Participants felt that support workers “who are doing the work because they want to, not because they need the money” have better work ethics because they “care about what they’re doing, they’re committed, they’re responsible” (Lesley).

Treat me as a person

Participants wanted support workers to humanise the support experience by “treat[ing] you like a person” (Charlie), rather than “their job,” “a number,” “a patient,” or a “body in a bed” (Lauren; Sarah; Kelly; Charlie). Fundamental to treating me as a person, is respect and dignity. Participants spoke of times they felt disrespected, including Lauren who recalled support workers who would “leave [her] lying on the bed spread legged” and not “shut the door when [she’s] on the toilet… things that you wouldn’t do for yourself, why is it ok to do to a disabled person?.” Participants also felt disrespected when support workers “talk about me like I wasn’t there” (Lauren) or speak for them when they have “the ability to order it for [myself]” (Darren). Many participants noted they wanted “empathy, but not sympathy” (Darren) from support workers. The overall sense of treating me as a person, as Ashley captures, was that “all [support workers] have to do is to treat other people like they would like to be treated.”

They didn’t know your name, treat you like you’re just a body in a bed… Here they treat you like a person, they ask you what you want. It makes you feel a lot better. Charlie

The words dignity and respect are something that people just don’t even think about, they just treat me like I’m their job, not a person. Lauren

It really makes a difference if support workers really engage with you compassionately and they don’t make it too much of a clinical setting, but they actually regard you as a person and not necessarily a patient. Kelly

See me as the expert

This factor reflects the participants need to feel seen and listened to by support workers. To tailor support to the individual, the support worker must be willing to learn from the person with disability and see them as the expert in their own needs and preferences. In practice, seeing me as the expert involved asking the person how they want to be supported, asking for feedback, listening to them and following their instructions.

Even if the rules seem ridiculous and over-exacting, if I say something’s important, just trust me that it’s important. Respect my perspective. Alex

You’re here to help me. It’s not what you like, it’s what I like. If I don’t like my shirts ironed, don’t iron my shirt because you like them ironed. Charlie

Participants stressed that support workers should not make assumptions about how they would like to be supported as “everybody’s different to each other, you can’t think two people are the same” (Georgie). Correspondingly, support workers should not direct questions to others about how to best support the person. Participants described experiences with support workers, particularly those working in institutional settings or who have a lot of experience, whereby the support worker “tries to run the show” (Isabella) and provides support in line with their own preferences or preconceptions rather than the needs and wants of the person with disability.

I wouldn’t mind if they’d had lots of experience if they were like ‘… this is a different situation, I can adapt, I can apply my knowledge… This is how we do it here, not this is how I do it’ and it’s so wrong to come into someone’s house and tell them what to do. Lesley

It was, like, not actually listening to what I was trying to say, it was just assuming what I was trying to say. And it drove me mad. Lauren

Respond to my needs

The final factor reflecting what the support worker needs to do captures the importance of workers being aware of individual needs, and willing and able to respond to those needs. As Isabella states, support workers need to "be helpful when you can see that I need some of your support." Participants highlighted the importance of support workers being attentive, having good attention to detail and getting to know their needs. Participants wanted support workers to be flexible in their approach to support, as needs can be variable and changing. Correspondingly, participants valued initiative and problem-solving abilities. In addition, each participant spoke of basic competencies support workers need to have depending on their support needs (e.g., domestic tasks, handling a wheelchair or hoist, transfers, personal care).

I’ve got a variable condition that changes from day to day so they need to pick up on the job… whether or not I’m strong enough… or that I can do something. Kelly

You can’t be on the phone to your family and then you go “argh,” you’re putting me second but you’re being paid by me to do something for me. If you’re putting me second that’s just not good enough. Charlie

I need to…

Lead my supports

As a first step in leading supports, participants highlighted the importance of knowing who to choose as their support worker, which can be difficult as “it’s not like anyone ever trains disabled people in how to do a job interview” (Alex). However, participants felt this process could be easier with support from someone they trust to help with interviewing and evaluating support workers. Alex suggested to “figure out what things actually matter to you” to guide your choice, rather than referring to “default requirements” (e.g., do you need someone who has a car, or someone who can get to work reliably). Participants interviewed support workers to get a sense of compatibility and competency. One participant suggested using learnings from previous failures with support workers to inform interview questions. Most participants endorsed trial shifts for assessing workers in practice.

Participants also described leading supports in terms of training and managing. They primarily used shadow shifts, to allow support workers to learn by seeing and doing. Many participants provided written information to guide support workers and reduce the burden of repeating instructions. Participants simplified instructions to avoid “overwhelming” (Lesley; Alex) support workers, and in turn assist them to follow instructions. Examples included having both a simplified and detailed care plan, simplified recipes, and colour-coding objects. Two participants felt that “explaining why things matter” can be helpful because “people remember better if they understand why something’s important to me” (Alex).

If you just give the people the whole list, it’s like super overwhelming. So, it’s good to have the short list on the fridge, which is just a page. Alex

Direct and clear communication was cited as key to leading supports. For some participants, this meant being “very strong” (Sarah) and articulating your needs. Participants also implied that having the capacity to direct support workers influences the way they treat you. Moreover, participants highlighted the value of setting expectations with support workers.

I’m clearly articulate and educated… so I’m not as easy for someone to kind of steamroll. But it’s horrible when people are trying to run your life for you. Alex

If you don’t want dinner at five o’clock, don’t be having dinner at five o’clock. Stick up your hand… probably the most important thing is to assert yourself. Sarah

Be upfront right in the beginning… because if I’m feeling depressed or sick, I can’t cope… my ability to speak and be articulate starts to stumble and struggle. Lauren

We need to…

Be the right fit

The support relationship was consistently acknowledged as a key factor influencing the quality of support. Participants discussed how being the right fit allows for a comfortable and productive support relationship, as support workers can be “a big part of your day and they become a big part of your life” (Paula). Participants valued being compatible with support workers, pointing to the importance of choosing their own workers, and the workers wanting to support them. For some participants, compatibility was about having shared interests or being a similar age.

Somebody who’s friendly, happy to like be like a mate… enjoys the things that I do, like going to the footy or the cricket. Tony

For other participants having workers who were the same gender to provide personal support for comfort, or for social activities in the community was preferred. For most participants, however, compatibility was not a tangible concept but more around “gelling” (Sarah; Kelly), “connecting” or “clicking” (Georgie).

Never once have I asked to see her resumé or her qualifications. I really don’t care what she’s got. I care about how we gelled. Sarah

I don’t waste time on the ones—if I don’t click with them, if I don’t get that vibe. Georgie

Work well together

This factor captures the importance of mutual respect, patience and effective communication in the support dyad. Participants discussed support as collaborative, with reciprocity and mutuality as facilitators of quality support. Ashley, hypothetically giving advice to a new support worker said, “we’re both new at this… let’s be patient and if I do anything that you don’t like, please let me know and I would like to do the same.” In terms of reciprocity, participants emphasised the importance of treating support workers well in order to receive quality support.

I want you to have respect for me, so I have to have respect for you. It’s always up to me. It always comes down to me of how I communicate to them. Lauren

If you talk to them like that, they’re not going to do anything for you… you get more with honey than vinegar and all that kind of thing. Georgie

Get the balance right

Participants recognised the support relationship as a balancing act, because whilst it is a working relationship, much of the work is personal in nature. This factor is not to say there is a right balance, more that there is a right balance for each dyad. Participants had varying preferences for the optimum support dynamic. Paula felt that “it’s always good to keep that sort of line in there between work and friendship.” Whereas Kelly “prefers the relationship to be flexible, you know… for boundaries… it’s better being fluid and flexible,” and Sarah wants support workers to “treat me as a friend, not a client.”

It’s really, really hard when, you know, if I’ve got this one carer four days a week for the next 10 months, it’s really hard not to make a relationship out of it. And where do you cross the line, you know? Ashley

Moreover, as all the aforementioned factors are influenced by the relationship, this factor emerged as a mediator across the dyadic space. With the changing nature of the role, there appears to always be an element of getting the balance right. For example, to effectively lead supports, the person with disability needs to learn how to communicate with their support worker and get the balance of instructing but not overwhelming them. Whereas the support worker needs to get the balance right in terms of how much to ask the person, so as not to burden them but enough to understand how they want to be supported and demonstrate that they see them as the expert.

Broader contextual factors and authentic choice

Broader contextual factors impact support quality primarily because they determine whether participants have authentic choice. Participants described the importance of having authentic choice in terms of building and managing their support team. In turn, having authentic choice can influence the realisation of the factors in the dyadic space, and therefore impact the quality of support. The authenticity of choice was emphasised because participants described experiences of having choice in theory but not in reality, as described below. The broader contextual factors discussed were support arrangements and the systemic and societal context.

Support arrangements

Support arrangements refers to the support worker employment set up (e.g., service provider, housing provider or direct employment) and support environment (e.g., shared supported accommodation, residential aged care, or private home). Support arrangements often determine whether people can choose and manage their support workers. Participants spoke of receiving support from “lots of different workers all the time” (Georgie) in shared supported accommodation and having to spend “a ridiculous amount of time fighting with old school agencies to do rostering and to not have support workers yanked off shifts” (Alex). Darren wanted to be authentically involved in choosing support workers and did not want service providers to just “bring a couple along for me to give approval for,” because “nobody should be able to choose [my] support workers.”

Not having the opportunity to choose support workers influenced the likelihood of being the right fit. Ashley, referring to staff in shared support accommodation, said “out of 42 people, there’s probably two people that I really get along with.” Participants discussed issues with service providers sending support workers they had never met.

I don’t want this random man to give me a bed bath and wash my genitals and feel like I have to let him because otherwise I might end up in the hospital. Alex

Participants receiving support via service providers, or living in shared supported accommodation, did not feel they could change workers. Ashley found it difficult to raise issues about staff because “you’ve really got to be careful that you don’t tread on toes because that very, very quickly gets passed around the staff room” and therefore feels he “really has to deal with what [he’s] been given.”

Furthermore, participants living in shared supported accommodation described experiences whereby they did not feel recognised as an individual and were unable to lead their supports. They were “expected to fit into their timetable” or “had to wait for someone with higher needs to be served before [getting] any attention” (Sarah). Kelly felt that “it was very much all about getting through the numbers and the work as quickly as possible. They won’t necessarily spend time on individual pursuits.”

Rules and regulations set by service or housing providers impeded the person’s choice and opportunity to lead their supports. Sarah, referring to her relationship with support workers said, “technically, we’re not meant to be friends.” Additionally, participants reflected upon experiences with support workers in supported accommodation who did not want to support them.

You get the feeling sometimes that they’re just there for the job, they’re just there to make money but they’re not really in it with their heart. Georgie

In contrast, participants spoke highly of direct employment because they felt in control of their supports and could choose support workers who are the right fit.

I do all the rostering and the choosing of who comes and when they come, which is great. Alex

I have made the decision to take control of hiring and firing my staff because I’ve had such a nightmare time with agencies and it just caused me more stress than I needed so I decided if I’m going to be stressed, I’m going to do it myself. Lauren

Systemic context

At a broader level, the systemic context governs whether people can choose who supports them. Georgie reflected that since the introduction of the NDIS and online support platforms, she can “find my own workers and we’ve created a really good team.” However, participants felt that low remuneration and “high attrition rate” (Alex) impact the quality of the workforce, meaning that even when the person has choice in theory, limited quality options are available. Correspondingly, participants ascribed the issue of support workers who did not want to support them to the low level of formal requirements for support workers.

It’s a pretty low paying job that doesn’t have any qualifications that you have to have, so you’re going to occasionally get people that just don’t care. Alex

Participants reflected upon the impact of high attrition rates in the support workforce impeding their control over supports, and the burdensome nature of “constantly looking for” (Paula) and training support workers.

It’s a very fine-tuning job. It’s not just popping someone in. It’s draining. Lauren

Moreover, participants complained about having to train support workers in the basics, because even those who had been trained “still don’t know what they’re doing” (Lesley). Multiple participants preferred support workers without training because those with training “have all these ideas and the first thing I have to do is un-educate them because all the ideas are wrong” (Alex). These systemic issues often resulted in participants feeling 'stuck' with support workers they no longer wanted to work with, as they feared not being able to find a better worker or were tired of hiring and training.

You never know what the quality of the next person is going to be… the energy required to train up and get used to a new person, is quite high. So, it has to get quite bad before I fire someone. Alex

Societal context

Support workers’ preconceived ideas and attitudes impacted the approach they took to support provision, often impeding the person’s choice and control. For example, Lauren had, had support workers who did things their way because they thought they were “making your life better by being here.” Participants also discussed support workers’ implicit attitudes about disability types impacting support.

Often people who are career disability support workers, some of them have that thing where they want to swoop in and save you. Or they think that they should run your life the way they think it should be run. I’ve had some of those and it’s horrible. Alex

When their background is with just intellectual disabilities, I tend to get a bit wary… I actually don’t tolerate being spoken to in a condescending way or babied. Georgie

Participants spoke of support workers perceiving them as “demanding,” “too opinionated,” or “insanely picky” (Lauren; Georgie; Alex), or disliking them, because they were direct about what they wanted.

My roommate was non-verbal and I’m like, “She’s the favourite because she can’t speak back.” … I was one of the least favourites because I was very opinionated. Georgie

Tony felt that support workers did not ask him for help (in reference to his support), because their attitude was “what would [he] know, [he’s] disabled.” These attitudes contradict the fundamentals of recognising me as an individual, seeing me as the expert and treating me as a person, and in turn, do not give the person the opportunity to lead their supports.

Feeling in control

The person with disability feeling in control emerged as a product of achieving the factors in the dyadic space and receiving quality support. When describing support from quality support workers, participants described being able to lead supports and live an ordinary life. For example, Charlie referring to his current support said, “I’m excited every day. I do my shopping on Tuesdays, I choose what I eat, I choose to help cook, it’s really good.” Similarly, Ashley, describing support from his favourite support worker said, “We don’t need to fight over decisions being made… he’s happy to just let me be myself. And give decisions about where I want to go… how long I’d go for. He’s very, very easy.” When participants felt at the centre of their support, this fostered an environment conducive to feeling in control.

As long as they know my needs, that it is all about me… they need to know that they work for me basically. Sarah

Model of quality support process

The findings emerged as a model of quality support with the fundamental factors situated in the dyadic space, and indirect factors positioned in the broader contextual space, as presented in . Factors within the dyadic space were interrelated and characterised by an overarching factor of recognising the person as an individual and getting the balance right as the key mediating factor. Further, the support worker’s approach to support provision can influence if, and how, the person leads their supports, and vice versa, and in turn how the dyad work together. Whilst the broader context influences multiple elements of the dyadic space, findings revealed that the key mechanism by which the broader context influenced support was by facilitating or impeding the person with disability’s authentic choice, which in turn influences the realisation of the factors in the dyadic space. Thus, the person with disability having authentic choice emerged as a facilitator of quality support. Finally, when the factors in the dyadic space were achieved, the provision of quality support was characterised by the person feeling in control of their support arrangements, and their broader life.

Figure 1. Model of quality disability support from the perspective of adults with acquired neurological disability.

Discussion

This qualitative study aimed to build an understanding of the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support from the perspective of adults with acquired neurological disability. The findings reveal a model whereby the foundation of quality support is how the support worker and person with disability work together in the dyadic space. Beyond the dyadic space, broader contextual factors influence the realisation of the factors in the dyadic space, by influencing whether the person with disability has authentic choice. Largely, quality support emerged as a process in which the person with disability’s choice facilitates quality support in the dyadic space and receiving quality support allows the person with disability to feel in control.

The prominent finding pertaining to the importance of the support worker recognising the person as an individual is encouraging, as it is in line with the person-centred approach to support and individualised funding schemes [Citation17,Citation18]. Critically, this study supports the notion that needing disability support should never rob a person of self-hood, choice and control. Further, these findings echo previous research suggesting that adults with acquired disability value support workers who see them as a person [Citation31–33] and take a “human approach” to support provision [Citation31]. Accordingly, the emphasis on the support worker treating the person with disability as a person further resonates with earlier studies highlighting the importance of respect, empathy and understanding in support provision [Citation30–32,Citation36]. The findings stressing that the support worker must see the person as the expert reflect previous research stating that support workers need to be willing to listen and learn to respond to the person’s needs [Citation31,Citation32,Citation34–36]. Being seen as the expert positions the person in a better place to lead their supports. Thus, quality support emerged as a collaborative process in which the support worker and person with disability must work well together.

Exploring support from the perspective of people with acquired disability revealed how working well together looks in practice. Participants consistently spoke of the fundamentals of mutual respect, open and honest communication, and patience. These findings broadly align with those of Robinson et al. [Citation37,Citation38], which illustrate the importance of mutuality, respect (including being heard and responded to), and shared values in the support relationship. Noting the significant role support workers play in their lives, participants in the current study and previous research [Citation34–36] felt that to work well together, it helps to be compatible. However, the findings demonstrate that the preferred support relationship varies between people, again promoting an individualised approach to support. Further, these findings highlight the need for robust relationship management training for support workers who are navigating various support relationships.

Promisingly, in terms of the principles of individualised funding schemes, the person with disability’s choice and control emerged as key factors in the support model. Corresponding with previous research [Citation28,Citation29], participants in the current study described the importance of having choice over their support arrangements. In addition, this study provided further insights into the mechanism by which choice and control emerge in the model of quality support. As evidenced in , choice emerged as the mechanism by which the broader contextual factors influence the quality of support because the participant’s descriptions of the contextual impact on support were centred around the contextual impact on choice. Having authentic choice, in turn, emerged as a facilitator of quality support by influencing the realisation of the factors in the dyadic space. For example, being able to choose support workers makes it more likely the dyad will be a good fit, or if the person with disability has choice over who supports them and their daily schedule (rather than the service provider), the support worker will be more inclined to see them as the expert in their own needs. Control, on the other hand, emerged as a characterisation of how the person with disability feels when they receive quality support. These findings are supported by Robinson et al.’s [Citation38] finding that the context in which support was provided could restrict opportunities for the individual to control decisions around their support. Thus, these findings support the focus of individualised funding schemes on choice as a key principle in disability support, but also suggest that it is important to dissect the broader context in which support is provided to ensure choice is facilitated in practice.

Future research

Given this study is the beginning of a series of studies, the subsequent studies aim to deepen the current findings to build a holistic model of quality support across the perspectives of people with acquired neurological disability, support workers and close others. Most prominent in the current findings was what the support worker needs to do to deliver quality support, but this study represents the perspective of people with disability. Thus, considering previous research on support worker stress and burnout [Citation22], we may learn more about how the organisational or structural level impact the experience and behaviour of support workers. Further, support workers may give more insights into what the person with disability can do to foster a positive support environment. Following the series of studies, the next steps involve working with people with acquired disability to co-design practical solutions to improve the quality of support and translate this research into practice.

Implications for policy and practice

This model of quality support can be used to inform support work practice and policy around support provision for people with acquired neurological disability. The findings have evidenced the foundational elements of quality support with practical examples to help guide practice. The model is such that all factors are interrelated, meaning improving one element of the model is likely to have a flow on effect to other factors. Primarily, and in support of the rights of people with disability [Citation4,Citation5], the provision of quality support requires the person with disability to be at the centre of all interactions and across all tasks regardless of the nature of their disability. Correspondingly, it appears that foundational to quality support is vetting potential workers for unhelpful pre-conceived ideas or attitudes about people with disability or the power dynamic between the person with disability and the support worker. However, it is evident from previous research that it is difficult to assess pre-conceived attitudes due to pervading social desirability effects [Citation51]. Thus, as suggested by a participant, the best way to assess the support worker’s approach to support provision may be to ask scenario-based questions or ask prospective workers to complete practical tasks or trial shifts as part of the recruitment process.

Considering the valuable practical insights provided by people with acquired disability, the current findings demonstrate the value of lived experience and the expertise of people with disability in informing practice and policy around support provision. Whilst it is broadly understood that it is best to take an individualised approach to support, the current study breaks this down and highlights key attributes and behaviours valued in support workers. For example, to demonstrate they recognise the person as an expert in their own support needs, support workers should direct questions to the individual and not make assumptions about their needs or preferences. Thus, whilst each person requires different technical competencies from support workers, these insights have important implications for developing training and development initiatives around the approach support workers should take to support provision. In addition, participants described useful strategies they use to lead their supports, which can inform guidance for other people with disability navigating support services. The findings of this study have also provided lessons for service providers, in terms of the importance of fostering the autonomy of the individual, and guiding support workers to recognise and prioritise the needs of each individual as that individual sees their needs. Further, in line with recent research [Citation13,Citation39], service providers should encourage and provide opportunities for support workers to build positive relationships with the people they are supporting.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first grounded theory study investigating the factors that influence the quality of support from the perspective of people with acquired neurological disability. Grounded theory methodology allows for rich qualitative data, and we included strategies in line with Charmaz’s [Citation40] quality criteria to ensure rigour of the study. Acknowledging the researcher’s role in both the collection and analysis of data, we incorporated opportunities for reflexivity throughout the study (i.e., journaling, field notes, memoing and discussions between researchers) and referred to the raw transcripts consistently up to the final stages of analysis and write up. Thus, the emergent model of quality support is truly grounded in the lived experience of the participants. A further strength of this study was that the participants had a wealth of experience receiving paid support and represented a range of levels of satisfaction with their support. However, it must be noted that there was limited heterogeneity in terms of cultural differences, thus there is limited generalisability across cultures. Given the findings in our scoping review [Citation27] around the importance of support workers meeting cultural needs, further research should look to understand quality support from people with different cultural backgrounds. In addition, the current participants were able to articulate their needs both to the interviewer and to support workers in practice. Thus, some of the strategies will not apply directly to those who are non-verbal or have severe cognitive disability. However, we believe that the key principles of recognising the individual and their needs and preferences apply across different disability types, even if the realisation of these factors differ. Another limitation of this study was that, although participants were given the opportunity to give feedback on summaries of their own interviews, they were not given the opportunity to provide feedback on the group findings. However, we plan to do this once all three studies, including the support worker and close other perspectives, are complete. Finally, this study represents only one perspective in the support dyad, thus our further research will deepen and broaden the current findings.

Conclusion

This qualitative inquiry was undertaken to gain an in-depth understanding of quality disability support grounded in the experience of adults with acquired neurological disability. Participants shared rich insights into their support experience and what impacts the quality of support. From this, a meaningful model of quality support was developed. The model is consistent with the broader literature and in line with individualised funding principles and the rights of people with disability. Despite limitations in the research, the current findings provide practical implications for individualised support provision and support the importance of ensuring people with disability are at the centre of their support.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank the participants with acquired neurological disability who generously shared their experiences and perspectives, making this research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Disabled World. Disability statistics: information, charts, graphs and tables [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.disabled-world.com/disability/statistics.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s welfare. Canberra: ACT; 2013.

- US Census Bureau. Washington DC: American Community Survey (ACS); 2014.

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: resolution adopted by the General Assembly, A/RES/61/106 [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2021 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/45f973632.htm.

- UN General Assembly. Report of the special rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities (Theme: access to rights-based support for persons with disabilities) A/HRC/34/58 [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2021 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Disability/SRDisabilities/Pages/Reports.aspx.

- World Health Organization. World Report on Disability [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2021 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-disability.

- Lord J, Hutchison P. Individualised support and funding: building blocks for capacity building and inclusion. Disab Soc. 2003;18(1):71–86.

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. NDIS Quality and Safeguarding Framework [Internet]. Canberra. 2016 [cited 2022 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/04_2017/ndis_quality_and_safeguarding_framework_final.pdf.

- Commonwealth of Australia (National Disability Insurance Scheme Quality and Safeguards Commission). NDIS Workforce Capability Framework. 2021.

- Redhead R. Supporting adults with an acquired brain injury in the community ‐ a case for specialist training for support workers. Social Care Neurodisability. 2010;1(3):13–20.

- Iacono T. Addressing increasing demands on Australian disability support workers. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;35(4):290–295.

- Hewitt A, Larson S. The direct support workforce in community supports to individuals with developmental disabilities: issues, implications, and promising pactices. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(2):178–187.

- Robinson S, Hall E, Fisher KR, et al. Using the ‘in-between’ to build quality in support relationships with people with cognitive disability: the significance of liminal spaces and time. Soc Cult Geogr. 2021;2021:1–20.

- Macdonald F, Charlesworth S. Cash for care under the NDIS: shaping care workers’ working conditions? J Ind Relat. 2016;58(5):627–646.

- Moskos M, Isherwood L. Individualised funding and its implications for the skills and competencies required by disability support workers in Australia. Labour Industry. 2019;29(1):34–51.

- McEwen J, Bigby C, Douglas J. What is good service quality? Day service staff’s perspectives about what it looks like and how it should be monitored. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(4):1118–1126.

- Ungerson C, Yeandle S. Cash for care in developed welfare states. Hampshire and New York: Palgrave McMillan; 2007.

- Purcal C, Fisher KR, Laragy C. Analysing choice in Australian individual funding disability policies. Aust J Public Adm. 2014;73(1):88–102.

- Parliament of Australia. National disability insurance scheme act. Canberra: Parliament of Australia; 2013.

- Cortis N, Meagher G, Chan S, et al. Building an industry of choice: service quality, workforce capacity and consumer-centred funding in disability care: final report. Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre; 2013.

- Ryan R, Stanford J. A portable training entitlement system for the disability support services sector [Internet]. Canberra; 2018. Available from: https://www.tai.org.au.

- Judd MJ, Dorozenko KP, Breen LJ. Workplace stress, burnout and coping: a qualitative study of the experiences of australian disability support workers. Health Soc Care Comm. 2017;25(3):1109–1117.

- Robinson S, Graham A. Feeling safe, avoiding harm: safety priorities of children and young people with disability and high support needs. J Intellect Disabil. 2021;25(4):583–602.

- Mavromaras K, Moskos M, Mahuteau S, et al. Evaluation of the NDIS Final Report. 2018.

- National Disability Insurance Agency. COAG Disability Report Council Quarterly Report – 30 June 2018 [Internet]. National Disability Insurance Agency. 2018 [cited 2021 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/publications/quarterly-reports/archived-quarterly-reports-2017-18.

- Cortis N, Macdonald F, Davidson B, et al. Reasonable, necessary and valued: pricing disability services for quality support and decent jobs Further information [Internet]. 2017. Available from www.sprc.unsw.edu.au.

- Topping M, Douglas JM, Winkler D. Factors that influence the quality of paid support for adults with acquired neurological disability: scoping review and thematic synthesis. Disab Rehabil. 2020;2020:1–18.

- Wadensten B, Ahlström G. Ethical values in personal assistance: narratives of people with disabilities. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16(6):759–774.

- Bourke JA, Nunnerley JL, Sullivan M, et al. Relationships and the transition from spinal units to community for people with a first spinal cord injury: a New Zealand qualitative study. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(2):257–262.

- Braaf SC, Lennox A, Nunn A, et al. Experiences of hospital readmission and receiving formal carer services following spinal cord injury: a qualitative study to identify needs. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(16):1893–1899.

- Fadyl JK, McPherson KM, Kayes NM. Perspectives on quality of care for people who experience disability. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(1):87–95.

- Nilsson C, Lindberg B, Skär L, et al. Meanings of balance for people with long-term illnesses. Br J Community Nurs. 2016;21(11):563–567.

- Yeung EYW, Partridge M, Irvine F. Satisfaction with social care: the experiences of people from chinese backgrounds with physical disabilities. Health Soc Care Commun. 2016;24(6):e144–e154.

- Gridley K, Brooks J, Glendinning C. Good practice in social care: the views of people with severe and complex needs and those who support them. Health Soc Care Commun. 2014;22(6):588–597.

- Martinsen B, Dreyer P. Dependence on care experienced by people living with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(2):82–90.

- Wadensten B, Ahlström G. The struggle for dignity by people with severe functional disabilities. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16(4):453–465.

- Robinson S, Blaxland M, Fisher KR, et al. Recognition in relationships between young people with cognitive disabilities and support workers. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;116:105177.

- Robinson S, Graham A, Fisher KR, et al. Understanding paid support relationships: possibilities for mutual recognition between young people with disability and their support workers. Disab Soc. 2020;2020:1–26.

- Fisher KR, Robinson S, Neale K, et al. Impact of organisational practices on the relationships between young people with disabilities and paid social support workers. J Soc Work. 2021;21(6):1377–1398.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2006.

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2008.

- Tate RL. Assessing support needs for people with traumatic brain injury: the care and needs scale (CANS). Brain Inj. 2004;18(5):445–460.

- Topping M, Douglas J, Winkler D. General considerations for conducting online qualitative research and practice implications for interviewing people with acquired brain injury. Int J Qual Methods. 2021;20:160940692110196.

- Topping M, Douglas J, Winkler D. Adapting to remote interviewing methods to investigate the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support. Sage Research Methods: Doing Research Online. 2022.

- Minichiello V. In-depth interviewing: principles, techniques, analysis. 3rd ed. Simai-Aroni RA, Hays TN, editors. Sydney: Pearson Education Australia; 2008.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home?_ga=2.57117602.966813235.1638426383-1710954617.1638426383.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2014.

- Constantinou CS, Georgiou M, Perdikogianni M. A comparative method for themes saturation (CoMeTS) in qualitative interviews. Qual Res. 2017;17(5):571–588.

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, et al. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):148.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251.

- Pelleboer-Gunnink HA, van Oorsouw WMWJ, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma research in the field of intellectual disabilities: a scoping review on the perspective of care providers. Int J Dev Disabil. 2019;67(3):168–187.

Appendix 1.

Participant interview schedule

Begin interview by thanking the participant for participating in this study and remind the participant that their participation is voluntary, and they can stop the interview at any time. Give the participant the opportunity to ask questions. Once consent has been re-confirmed verbally, confirm any incomplete items from the demographics form and then use the following questions as an interview guide. Prompt participants as necessary (e.g., tell me more, can you give me an example of a time…) and alter questions and ordering of questions as necessary in line with the participant’s narrative.

Tell me about your current support arrangements.

What do you think of the quality of support you receive?

Tell me about time/s when you received excellent support

Do you have (or have you had) any excellent support workers? Can you describe them to me? What makes them excellent?

Tell me about time/s when you feel the support could have been better.

What can make it difficult to work with support workers?

How do you think the quality of support you receive could be improved? What would help?

Tell me about your experience finding/hiring new support workers?

What do you look for (/value) in a support worker? (If prompts needed e.g., skills, qualities, characteristics, training, experience)

Tell me about your relationships with your support workers.

Are there other factors you think influence the quality of support you receive? What makes it better/what makes it worse?

What advice would you give to a new support worker about how to be an excellent support worker?

What is the most important factor that influences the quality of support?