Abstract

Purpose

Lockdowns due to the Covid-19 pandemic may have had a disproportionate impact on the daily lives of people with intellectual disabilities. Many of them had to deal with limited social contacts for an extended period. This study explores in depth how people with intellectual disabilities in the Netherlands experienced their daily lives, in particular due to lack of access to regular work activities.

Materials and methods

Eight participants with intellectual disabilities were interviewed. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was employed in conducting and analysing interviews.

Results and conclusions

Analysis yielded three overarching themes that are conceptually linked. Participants experienced a prolonged lack of social connections that resulted in experiences of social isolation and feelings of loneliness. This led to different kinds of struggles: either internal struggles involving negative thoughts or depressive feelings, or a perceived threat to their autonomous position in society. Meanwhile participants had to sustain their sense of self-worth in the absence of work activities. The findings emphasise the importance of social opportunities through the access to work activities for people with intellectual disabilities. Interventions are suggested to help reverse the increased social inequalities and enhance rehabilitation via work activities for people with intellectual disabilities.

More awareness may be raised among authorities, employers and the general public about the significant value people with intellectual disabilities attribute to meaningful social connections, in particular through work activities.

Also, more awareness may be raised about the potential adverse effects of the loss of work activities and social connections on the quality of life of people with intellectual disabilities.

Providing social support to others may help people with intellectual disabilities to construct social valued roles, either in or outside the work situation.

Professionals and employers can support people with intellectual disabilities to find opportunities to provide social support to others.

It is important to invest in sustainable and innovative post-pandemic community participation initiatives and particularly in accessible post-pandemic employment support, for example by organising paid in-company training placements.

It is essential that professionals support people with intellectual disabilities to enhance their sources of resilience and coping strategies, that may have diminished as a result of the pandemic.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABLITATION

Introduction

The global Covid-19 pandemic has had a substantial impact on the lives of many people. Since the start of the pandemic, to a greater or lesser extent, attention was paid to vulnerabilities of specific groups in society [Citation1]. Among others, the pandemic has a particular impact on the lives of people with intellectual disabilities; physically, mentally and socially [Citation2,Citation3]. A large international study [Citation4] revealed, for example, that family members and professional caregivers experienced the pandemic to have a disproportionate negative impact on the lives of people with intellectual disabilities, due to an increase in depression and anxiety, stereotyped behaviour, aggression, and weight gain.

Social restrictions, also in terms of lockdowns, have been applied around the world for a long period of time to prevent the spread of the Covid-19 virus [Citation5]. As people with intellectual disabilities tend to have smaller social networks than people without intellectual disabilities [Citation6] and may be more vulnerable to social isolation and loneliness [Citation7], these social restrictions may have had a substantial impact on their lives. This may be particularly true for people with intellectual disabilities living in supported or residential facilities, as they had reduced possibilities to visit or be visited by family and friends and to meet fellow residents [Citation4]. In the Netherlands, for example, most service providers followed national advice of the branch association of professional service providers in the disability care sector [Citation8] and therefore closed supported and residential facilities for visitors, including family, when the first lockdown was introduced. Studies conducted during the first phase of the pandemic indicated that people with intellectual disabilities perceived the Covid-19 pandemic and the restrictive measures imposed as having a major negative impact on many aspects of their lives and well-being, for example, by causing them to experience a lack of connection with significant others, and by reducing or altering the nature of their access to support [Citation9–11]. Consequently, people with intellectual disabilities may have generally experienced major obstacles in maintaining social contacts in their daily lives during the pandemic. As a result they may have experienced reduced social networks and social exclusion [Citation12]. These problems were compounded by disturbing changes to and interruptions in their employment situation, such as having to interrupt employment temporarily or working remotely [Citation9,Citation13].

Participation in employment, either paid or unpaid, or meaningful daytime occupation is perceived as an important aspect of the lives of people with intellectual disabilities, including the positive effect on their position in society and social contacts [Citation14–17]. Having a job or daytime occupation [from here referred to as “work activities”] is associated with better physical and mental health of people with intellectual disabilities [Citation18] and enables them to experience social connections, a useful and structured spending of time, opportunities to achieve personal development, and a sense of being part of society [Citation19–21]. In addition to the benefits of work activities, it has been suggested [Citation19] that employed people with intellectual disabilities expect unemployment to lead to an experience of emptiness in their lives, in terms of activities and social connections and that a lack of access to regular daytime activities is associated with the prevalence of challenging behaviour, such as self-injurious and stereotypical behaviour, among people with intellectual disabilities [Citation22]. Thus, among other benefits, participation in work can be an important pathway to create and maintain social capital for people with intellectual disabilities [Citation23].

Despite the perceived advantages of work, paid employment rates for people with disabilities are significantly lower compared to the general population in many countries, for example in Canada, the Netherlands, the UK and the US, even in the flourishing economic situation prior to the Covid-19 pandemic [Citation24–27]. Unfortunately, this disability employment gap has widened further in these countries since the Covid-19 pandemic began [Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28]. In addition, the Covid-19 pandemic has also had adverse effects on participation in unpaid employment options, such as daytime occupation. As lockdowns were enforced, services that provide daytime activities for people with intellectual disabilities were closed across a number of countries with higher rates of Covid-19 [Citation4,Citation29–32]. As such, the pandemic has had a detrimental effect on the access of people with intellectual disabilities to work activities, both (paid) employment and daytime activities.

When restrictions were eased in the summer of 2020, day services reopened, in Ireland and the Netherlands for example, albeit with a reduced capacity [Citation29,Citation31]. As Covid-19 infection rates increased again in autumn 2020, stricter measures were reintroduced in many countries. In the Netherlands, for example, a partial lockdown was implemented in October 2020, with measures that included closing bars and restaurants, advising people to work from home and restricting the number of guests in the home to three a day. Subsequently, on 14 December 2020, even a stricter lockdown was imposed, which led to the closure of non-essential shops and the number of guests in the home being reduced to one a day. This inevitably led to a further prolonged interruption of day services [Citation33,Citation34], in addition to a structural decrease in volunteering and employment options [Citation35]. People with intellectual disabilities therefore faced a prolonged loss of a substantial part of their social connections, as a result of their loss of work activities. This impact on social connections adds on the previously mentioned broad impact of social restrictions -and the additional measures in residential facilities- on the social connections of people with intellectual disabilities.

When considering how the initial lockdown negatively impacted upon people with intellectual disabilities, specifically with respect to their personal life and work situation, it is vital to rigorously explore how they experienced the later stages of the pandemic. These stages were characterised by broad restrictions on social contact in daily life for an extended period of time, also due to the lack of work activities. Despite widespread recognition of the negative impact that long-term unemployment can have on people’s lives generally [Citation36], there is a dearth of in-depth scientific knowledge about how the loss of work activities impacts upon the lives of people with intellectual disabilities. Therefore, it is essential to draw particular attention to how people with intellectual disabilities experienced the loss of work activities during this period of time. Indeed, shedding light on these experiences can enhance scientific knowledge about the disadvantages this group experiences as a result of a lack of access to work activities due to social restrictions during periods of crisis. In addition, exploring these experiences enables us to identify potential facilitators of, and barriers to, coping with the loss of work activities during contexts characterised by limited opportunities for social connection and support. The insights yielded from this research can subsequently inform public authorities about how important the social connections formed through work activities are for people with intellectual disabilities, in addition to contributing to policy-making for future crises.

Consequently, this study sets out to answer the following research questions:

How do people with intellectual disabilities give meaning to their daily lives when they have limited social connections, and especially when they experience a long-term lack of access to work activities during a period of crisis?

What facilitators and barriers do people with intellectual disabilities experience when attempting to cope with limited social connections during a crisis, particularly if this stems from the long-term loss of work activities?

Materials and methods

Study design

In this study Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) [Citation37] was employed. Data collection, using semi-structured interviews with the eight participants, started on 19 November 2020 during the partial lockdown in the Netherlands, and continued until the unexpected announcement of a stricter lockdown on 14 December. Before that date, five participants had already been interviewed; the interviews with the three remaining participants had been scheduled for after 14 December. In order to include data on how all of the participants experienced the stricter lockdown, a decision was taken to conduct an additional interview with the five participants who had been interviewed previously. As a result, this study consists of five participants who were interviewed twice and three participants interviewed once, with the first group being treated as the core dataset. This means that we used the interviews of the first group as a focus for the overarching analysis, after which we incorporated the experiences of the remaining three participants. The two interviews of the participants who were interviewed twice were analysed separately and subsequently merged. For this study, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of Tilburg University [RP 149].

Participants

Participants were recruited from a Dutch organisation that provides both residential and community-based support to people of all ages with intellectual disabilities ranging from profound multiple disabilities to borderline intellectual functioning. Professionals were asked to indicate possible participants who met the following criteria: (I) a diagnosis of mild intellectual disability or borderline intellectual functioning (IQ scores between 50 and 85); (II) an age of 18–50, since people with intellectual disabilities are at risk of frail health from the age of 50 [Citation38], which can affect the perception of loss of work activities; (III) having lost at least one half of their (paid or unpaid) working hours since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in the Netherlands (i.e., since March 2020); (IV) being at home without any replacement organised daytime activities for at least three working days a week.

Five men and three women aged between 21 and 40 (average age: 29.9) participated in this study. Demographic data were obtained from the participants during the first interview and from their files, with their consent (see ). To protect their anonymity, the participants are identified using pseudonyms. The participants’ work situations were diverse. Nick and Tim both used to have a competitive paid job in the hospitality industry, with Tim being supported by a job coach of the service organisation. Tim was unemployed after his employer went bankrupt in July 2020. Nick could only work minimum hours from October 2020 due to the second hospitality industry closure in the Netherlands. Jerry used to have an unpaid daytime occupation at a day centre, run by a service organisation that went bankrupt during the first lockdown. Katie, Marvin, Melissa, Oliver and Veronica all had an unpaid daytime occupation in the community, which was organised or supported by the service organisation that also facilitated their residential support. Therefore, the work activities of these participants were, to a greater or lesser extent, affected by the measures taken by the service organisation, in line with national policy. In terms of closing and reopening day centres this meant that day centres closed in March 2020 and home-based daytime activities were sought to be provided instead. From September 2020, the day centres were gradually reopened. With the exception of Tim and Jerry, all participants were offered to return to their work activities part-time or full-time from September 2020 or before. However, Melissa and Oliver chose not to resume work activities because of concerns about possible Covid-19 infection. Marvin and Katie had partially resumed work activities, but Katie was back home again due to private circumstances. Veronica had resumed work in June 2020, but was out of work activities since the hospitality industry closed again in October 2020 and her employer could not offer her any alternative work activities. Therefore, at the first interview, six participants had no working activities, whereas two (Nick and Marvin) had been assigned replacement activities at their workplace for several hours a week. Six participants had been told that they would be able to fully resume their original work activities as soon as the Covid-19 situation permitted, whereas two (Tim and Jerry) had no prospect of returning to their job.

Table 1. Descriptive personal data of participants.

Two participants (Nick and Tim) were living independently, and one (Oliver) was living with his parents. Five participants (Jerry, Katie, Marvin, Melissa and Veronica) were living in community-based care facilities with support. These participants were therefore affected by the national Covid-19 policy implemented by the service organisation supporting them concerning visitors and meeting fellow residents. This meant that between March and July 2020 they were not allowed to receive any visitors at home and could only meet their fellow residents at set times. In addition, participants sometimes had to deal with their residential location being closed because a fellow resident had become infected with Covid-19. As a consequence, participants were not allowed to leave the location or receive visitors for a certain period of time. The easing of the measures from July 2020 was tailored within the organisation on a site-by-site basis, resulting in differences in measures per site. With the new restrictions in October and December 2020, the service organisation sometimes deviated from national policy with, for example, wearing a face mask becoming mandatory at these residential locations earlier than within the national policy.

Procedure

Potential participants were initially approached about participating in the study through a professional or family member. If they expressed an interest in taking part, the first author called the potential participant to check the inclusion criteria, to give them further details about the study and to answer any questions. If they still expressed interest, they were sent an information letter and informed consent form. The letter described the key aspects of the study in detail, along with measures taken to safeguard the confidentiality and rights of the participants. A first interview was planned when they agreed to participate. Before the start of the first interview, the information letter and the informed consent form were carefully reviewed with the participants to make sure that they were fully aware of their decision to participate, after which they signed the informed consent form.

An interview schedule following IPA guidelines [Citation39] was used. The interview schedule was pilot tested among three co-researchers with mild intellectual disabilities, after which minor adjustments were made in the formulation of questions. The interviews started with an open question: “Can you tell me something about how you are experiencing your life right now?” Subsequently, the interviewer tried to respond to elements of the participant’s story, using open-ended questions whenever possible to give participants as much control over the conversation as possible. This allowed information to emerge that was not directly relevant to answering the research questions, but which could help to understand the participants’ experiences within their life context. To explore the participant’s experiences in detail, the interview schedule included some potential questions that could be asked when the topic did not arise spontaneously (see ).

Table 2. Potential questions included in the interview schedule.

The second interview – if applicable – was based on the same principles and started with the open question: “How have you been doing since our last interview?” This was followed up by questions formulated in advance with a view to exploring how participants were experiencing and coping with the stricter lockdown. In the case of the three participants who were interviewed only once, the interview schedule was supplemented with relevant topics from the other participants’ second interview schedule.

The participants were given the choice of being interviewed in person or remotely using video conferencing software; all of them opted to be interviewed in person. The participants were interviewed at home, except for one participant who preferred to be interviewed at the office of the service provider. All interviews were conducted by the first author. Although employed by the participants’ service provider, she had never been professionally involved with any of the participants. Interviews took place in full compliance with the Dutch government’s Covid-19 guidelines as they applied at the time and any additional precautions taken by the participants’ service provider. On one occasion, the second interview was conducted on Skype as the participant felt more comfortable being interviewed remotely; on another occasion, the second interview was conducted by telephone due to quarantine measures. The interviews took an average of 46.5 min each (range: 29–76). With the participants’ consent, all of the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The stages described in the IPA guidelines [Citation39] were carefully applied throughout the analysis, which was conducted by one researcher in close cooperation with a second researcher. Discussions with the full research team were held throughout the analysis process. At the first stage, the recordings of the interviews were listened to, and transcripts were read and reread by one researcher who subsequently, at the second stage, made initial notes on descriptive, linguistic and conceptual aspects. These were carefully audited by and discussed with the second researcher. The third stage involved the formulation of emergent themes by one researcher based on rereading the transcript and initial notes, which were also discussed with the second researcher until consensus was reached. At the fourth stage, the two researchers discussed possible overarching themes based on the emergent themes already formulated. The emergent themes were then clustered according to the overarching themes, audited and discussed by two researchers. At the final stage of the analysis, the overarching themes within and across cases were discussed in detail by the entire research team to identify patterns, similarities and differences. Throughout the process, a reflective journal was kept to document the decisions made.

Results

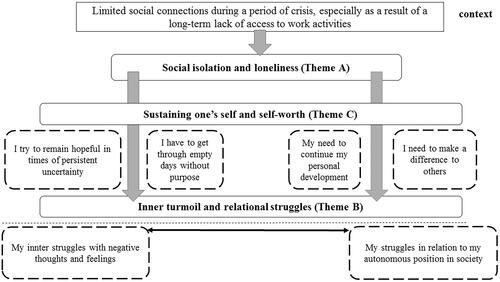

Analysis yielded three overarching themes that are conceptually linked. These themes are presented below and visualised in .

Figure 1. Model of overarching themes.

Theme A: social isolation and loneliness

Participants expressed a significant lack of social connection, which led to social isolation and loneliness. For Marvin, Katie, Tim, Veronica, Jerry and Nick, the social connection to others was significantly impacted by the unintentional loss of their work activities due to Covid-19.

Katie, for example, characterised herself as a people person for whom togetherness and physical contact, particularly cuddling, with significant others are of great importance. The loss of social contact as a result of having to stop her work at a petting zoo, combined with restrictions affecting participation in social activities with fellow residents at her supported home due to Covid-19, led to a significant loss of meaning in her life.

For Melissa and Oliver, there was a different relationship between the loss of work activities and the lack of social connections: they both decided not to resume work despite being given the opportunity to do so. As Oliver considered himself to be at high risk from Covid-19 due to a lung disease, he and his mother decided he should stop his jobs at two nursing homes and a lunchroom, even before the initial lockdown started. Oliver missed the contact with people at work, but above all he missed the personal and intimate contact with his friends, because he only rarely had the chance to meet them in person. For him, online contact via WhatsApp was not sufficient to experience this close connection.

Although Melissa also missed the contact with her colleagues and clients at her job in a nursing home, avoiding loneliness was actually one of the reasons behind her decision not to resume work at that stage in the pandemic. She perceived a high latent risk of infection at the nursing home and was worried that she could easily become infected there. Melissa therefore feared that resuming work would increase the risk of having to quarantine, which in turn would stop her participating in the social activities at her supported home and prevent her from visiting her vulnerable parents. She talked about desperately wanting to avoid the loss of contact with her small circle of significant others.

Melissa: Then I think I’d also … um… feel lonely, because then all I’d do is come home and take a shower and stay in my apartment. I don’t know, I've never tried to go to work and see what happens. And I don’t know what arrangements would follow or what it would be like (…) But I’m like, I’m not going to risk it. I' m not… um…. I'm not going to take that chance.'

Theme B: inner turmoil and relational struggles

The lack of social connections during the pandemic caused the participants to focus more intensely on themselves and their own situation. This affected both their emotional balance and the relational balance between themselves and others. It led them to experience inner turmoil or struggles regarding their position in society.

My inner struggles with negative thoughts and feelings

Some participants experienced inner turmoil due to the lack of social connection. Both Veronica and Nick experienced feelings of gloom. The prolonged loneliness and lack of connection with others during the dark days of winter led Veronica to express dark thoughts. However, she still had sufficient coping skills to avoid falling into depression. Nick, in contrast, experienced feelings of hopelessness and ultimately spiralled down into depression. He was prescribed medication by his general practitioner. Nick seemed to derive his own sense of identity very strongly from his connection with other people and from his identity at work. The decrease in his work activities in a restaurant and the restricted social contacts in both his work and personal life meant that important sources of meaning and aspects that defined his identity were lost to him. On his own, he was no longer able to be the person he wanted to be and slipped into a spiral of negative feelings.

Nick: ‘Then it really is all down to you, and it even gets to the point where you don’t want to go on anymore. You just go crazy inside, you get headaches and you get depressed.’

Although he did not slip into depression, Marvin was caught up in a pre-existing cycle of negative thoughts, exacerbated by the pandemic and the lack of work opportunities. He expressed the need for social meetings and activities outside his home (e.g., activities with friends and contacts with customers at work) as these constituted important sources of distraction from his negative thoughts. He explained that doing domestic activities on his own did not offer him sufficient distraction from and control over his negative thoughts.

Marvin: ‘Yes, when I'm at home too often and I'm in my room too much (…) I don’t know why it’s like that in my head, but in my head I just keep thinking. I get to thinking way more about all kinds of things, about things that went wrong in the past or what could have gone better and, well, I just kind of dig a hole for myself.'

In contrast, the emotional turmoil experienced by Jerry was not caused by the limitations on social contact themselves, but the fact that these limitations were imposed on him by others. The Covid-19 restrictions, and in particular the quarantine measures imposed due to a Covid-19 infection at the supported accommodation where he lives, reminded Jerry of the years he spent in a locked facility, a time he remembered as traumatic and stressful. As a result, he did not want to be deprived of his freedom by the quarantine measures and, against the rules, he continued to visit his family.

Jerry: ‘Yeah, I spent eight years in a locked facility (…) No one’s going to stop me doing that. They did that for a very long time, but not anymore. (…) No, that makes me feel like I’ve been locked up. When I think back on that, it drives me completely crazy.’

My struggles in relation to my autonomous position in society

The changes in social connections led other participants to experience difficulties with regard to the autonomy they wanted to experience in identifying with and relating to other people in society.

Melissa and Katie suffered due to missing opportunities for optimal participation in society. This confronted them once again with their status as a person with an intellectual disability, whereas before the pandemic they had been able to distance themselves from this identity. Melissa used to work in a regular nursing home. She specifically experienced her responsibilities being given to her in caring for elderly residents as things that set her apart from other people with intellectual disabilities. When, in the first phase of the pandemic, she was no longer allowed to work in the nursing home, she was offered substitute handicraft activities at a day care facility, that made her feel undervalued and treated like a child. She expressed her objections to participating in these alternative activities.

Melissa: ‘Yes, and [normally] I work in the neighbourhood. (…) I'm not one for pasting and cutting and all that stuff. (…) I mean, what do they think I am? A 6-year-old kid? Get lost, that’s what I say. That’s not me at all.’

At the same time, being at home so much made Melissa aware of the fact that the Covid-19 measures at her supported accommodation were often different from and more restrictive than the measures for people who do not live in a facility. Like Melissa, Katie experienced her supported accommodation had become a hospitalised environment. Due to the Covid-19 measures, support staff took over tasks from all the residents (such as serving food) and also decided which fellow residents Katie was allowed to meet in the common room and at what time. Katie was also confronted with the status of “vulnerable person”: this was applied to her as a resident of a facility for people with intellectual disabilities, whereas she did not perceive herself as vulnerable.

Katie: ‘Some of the people here are vulnerable, but if you take me, I am otherwise healthy (…) But I still get that label though in terms of health I am not really vulnerable at all. (…) Because it’s an institution they see me as vulnerable.’

Whereas Katie’s and Melissa’s confrontation with their status led them to actively disassociate their personal identity from that of other people with intellectual disabilities by making comparisons, Tim’s confrontation with his intellectual disability led him to speak out in favour of opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities as a group. Tim, who gives the impression of having evolved into an independent and socially engaged person, lost his regular paid job. This forced him to confront his status as an intellectually disabled person once again and face up to the difficulties of living in society while having these disabilities. He had to re-connect with himself as a person with a disability and as part of the group of people with disabilities, a group he felt he had outgrown as a result of his job. This involuntary reactivation of the connection he felt with this group made him want to do something for the group that he said he felt connected to, but not fully part of.

Theme C: sustaining one’s self and self-worth

The lack of work activities and social connections implied that several key elements in participants’ lives were no longer evident, which meant that they had to work hard to maintain their sense of self and self-worth.

I try to remain hopeful in times of persistent uncertainty

The long-term lack of work activities in the context of the unclear and ever-changing situation caused by the pandemic took its toll on all of the participants. However, their abilities to adapt and keep on dealing with this situation differed.

Some participants clearly suffered due to the prolonged lack of prospects resulting from this situation. Marvin, for example, became frustrated by the government’s ever-changing and fluctuating Covid-19 policy, which made him feel like he was constantly taking one step forward and two steps back. He needed more clarity and predictability.

Other participants, however, appeared to succeed better in adapting to the long-term lack of clear prospects. Tim’s open-mindedness and ability to take things as they come seemed to provide a buffer when coping with the current difficulties in his life. Nevertheless, the longer the situation lasted, the more Tim began to lose hope of finding a new job. To protect himself, he tried to temper his expectations but emotionally he seemed to find it difficult to accept his unemployment.

Like Tim, Katie found it increasingly difficult to maintain hope. On the one hand Katie tried to use her experiences during the crisis as a source of support and help for the future. In other words, she felt that – with the crisis as a reference point – she would be better able to handle difficult situations in the future. On the other hand, Katie noticed that she became frustrated with the Covid-19 situation, exerted by feelings of insecurity caused by the ever-changing news about the vaccination strategy.

Katie: ‘On the other hand, I'm like, “Don’t splash it all over the media unless you’re sure,” you know (…) It makes me feel insecure and it probably makes other people insecure too.’

I have to get through empty days without purpose

Participants experienced a lack of variety in their lives that led to a sense of drudgery. Every day seemed to feel the same. The lack of purpose and structure in their lives led them to lose their grip on their personal day-night rhythm.

In the case of Veronica, for example, missing work, and the subsequent reduction of social contact, routine and purpose, made her feel that she no longer had a life.

Veronica: ‘Before you used to work and you had all your colleagues around you, a good atmosphere and you could talk to your colleagues, it was nicer. Now all that’s gone and you miss it. Now I actually feel like I don’t really have a life because … you know what I'm trying to say? Normally you go to work and now you don’t. Now you get up and then it’s like “what am I going to do now”, you know?'

Nick seemed to be a person who got bored easily. When the hospitality sector and other amenities were shut down for the second time in October 2020, an increasing number of activities that might have kept him entertained were no longer possible because of the restrictions (e.g., go-karting, going to the gym). Time seemed to drag by endlessly and this drove him crazy. He noticed that boredom made him lazy and led him to postpone things, but he couldn’t find a way to turn things around.

Nick: ‘[Time] seems to drag on endlessly, so that time actually makes you crazy, and out of boredom you don’t do anything anymore and you get all lazy and lame, so you don’t feel like getting up or doing anything in the first place. You keep putting things off like “I still have to clean the bathroom … Oh, I'll do that tomorrow.” Because you feel that way every day.’

In contrast, Jerry managed to find a new purpose in his days. During a long period without work activities in the past he also fell into a vicious circle and his day-night rhythm was adversely affected, which made him feel tired of almost everything. At the time of the interview, however, Jerry was running his own internet radio station with a friend. This made him feel that he had created his own daytime activity, which made him proud and gave him a sense of having things to do every day.

I need to continue my personal development

Each in their own way, participants experienced that the lack of work activities during the pandemic deprived them of opportunities to learn new things and keep developing as a person. However, some participants found other ways to continue their personal development or even attach new value to certain aspects of their lives and development as a result of their experiences since the outbreak of the pandemic.

For Oliver, learning and personal growth were important sources of inspiration and energy, with the ultimate goal of being able to participate in society as independently as possible. He felt that this growth had come to a complete standstill.

Oliver: ‘A standstill. The brakes are mostly on, I can keep moving but not a lot actually, (…) I do miss growing, continuing to grow, in the sense of learning all kinds of things and being allowed to make mistakes.’

However, he found new ways to meet his needs during the Covid-19 period by learning English through an app and attending an online course with his mother.

Katie, in contrast, put off achieving the goals she had before the pandemic. She initially regretted that the pandemic prevented her from obtaining her driver’s license and doing a course to become an expert client. However, the pandemic made her aware of the importance of enjoying the small things in life, such as physical contact with significant others. She decided she wanted to focus more on these small things in life after the pandemic and postponed her more ambitious goals.

For Veronica too, life during the pandemic provided a positive learning experience. Shortly before the initial lockdown started, Veronica had moved from her parents’ home to supported accommodation. In contrast to many of her fellow residents, Veronica chose to stay in her own home instead of moving back in with her parents. Even though this was a difficult and lonely time for her, she looked back on it as an experience that helped her grow as an autonomous person and to become more self-reliant.

I need to make a difference to others

Although Nick, Tim, Melissa and Katie normally work in different sectors, they all missed making a difference in the lives of their customers or clients. Katie, for example, missed working in the farm shop, where she enjoyed making her regular customers feel happy and special by giving them attention. Katie talked about one customer her colleagues did not get along with, but with whom she had a special connection. She enjoyed finding ways to keep this customer satisfied.

Katie: 'She can be blunt sometimes and some people can’t cope with that. But I turn it around and just try to stay nice (…) It’s very special that a customer likes me and thinks I'm nice. (…) It’s great, wonderful. That makes it all worthwhile (…) keeping the customers happy.’

Despite the absence of work, Melissa found ways to continue to care for others and make a difference to their lives. This was important to her. For example, Melissa identified herself as a family caregiver for her parents and sometimes did shopping for them. She also tried to help the housekeeping staff at her supported home. In Melissa’s experience, these activities helped her make more of a difference to others than the alternative handicraft activities she was given instead of her work in the nursing home. She also enjoyed the appreciation that the housekeeping staff expressed when she helped them.

Tim, by contrast, experienced working as a way to make a difference to society as a whole, for which a salary is the quid pro quo. When he became unemployed, he experienced the income from his benefits as money for nothing, a free ride without having to do anything in return. This made Tim feel bad. He felt it was unfair that others had to make a real effort to have the same amount deposited on their bank account, while his own competencies remained untapped.

Tim: ‘Well, it kind of feels like you’re looking for a handout, like I don’t have to do anything but they give me money anyway. Yeah, that doesn’t really feel right. You know, that one person, my neighbour say, has to work 40 hours a week for about 400 euros and I just sit at home and [whistles] in comes the money. Yes, it’s not nice. I get it, fine, but I mean basically I can work for it.’

Discussion

This study is an in-depth exploration of how people with intellectual disabilities experience their daily lives with limited social contacts, in particular as a result of a long-term lack of access to regular work activities due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This situation made participants suffer from a prolonged lack of social connection, resulting in social isolation and feelings of loneliness. This left participants to draw on their own inner resources and ultimately confronted them with different types of personal struggles. Some participants mainly felt inner turmoil and had to focus on themselves to control the depressive feelings or negative thoughts they experienced due to severe long-term social isolation and loneliness. Other participants experienced struggles that were directly related to what they felt was a threat to their autonomous position in society and sometimes even a confrontation with or a sharp reminder of the stigmatising status of having an intellectual disability. Meanwhile participants had difficulty sustaining themselves and their sense of self-worth, as some key aspects of their lives were no longer self-evident without regular work activities and social connections to engage in. These findings shed further light on the significant value that people with intellectual disabilities attribute to meaningful social connections and work activities, and on the potentially drastic adverse effects on their quality of life when being deprived of these elements in their lives.

Participants in this study mentioned some positive effects of the pandemic, which are also reported in other studies. For example feeling more relaxed and having more time for hobbies [Citation11] or developing skills or personality traits, such as responsibility for themselves and others [Citation39]. However, these positive effects by no means outweigh the psychological and social impact of the preventive measures on the lives of people with intellectual disabilities, which are both reported in this qualitative study and in various quantitative studies [Citation2–4,Citation40]. Puyaltó et al. [Citation12] explored the relationships of people with intellectual disabilities during a similar phase of the pandemic and yielded comparable results. The lack of physical contact caused participants in that study to experience dehumanisation and cooling of relationships, leading to distress in some cases. The detrimental social and psychological effects of the pandemic on people with intellectual disabilities may have several reasons. First, people with mild intellectual disabilities are vulnerable to experiencing a lack of social connections, as they generally tend to have smaller social networks and less supportive resources [Citation6]. Yet at the same time, despite the support needs of people with intellectual disabilities [Citation41], the access to professional support services has deteriorated for them since the pandemic began [Citation42,Citation43]. Therefore, the pandemic may have further limited the availability of supportive resources to help people with intellectual disabilities cope with the social restrictions including lack of work activities. Second, people with intellectual disabilities are generally assumed to be a high risk group for mental health problems, such as depression [Citation44]. Social restrictions and lack of work activities may have further increased this risk, as people with intellectual disabilities are at higher risk to experience feelings of loneliness and experiences of chronic loneliness presumably exacerbate depression in people with intellectual disabilities [Citation7]. In general, the sources of resilience of people with intellectual disabilities [Citation45], both internal (i.e., autonomy, self-acceptance, physical health) and external (daytime activities, social network), may be diminished during a pandemic due to restrictions on freedom and loss of work activities. It is therefore essential that professionals support people with intellectual disabilities to enhance their sources of resilience and coping strategies [Citation45], particularly during a pandemic.

In addition to feelings of loneliness and depression, participants in this study experienced that the long-term situation with restrictions on social contacts, particularly due to a lack of access to regular work activities, threatened their autonomous position in society. In line with the study of Puyaltó et al. [Citation12], our findings suggest that people living in a supported accommodation may have experienced more restrictions in their autonomy than people not living in supported accommodation, potentially leading to feelings of stigmatisation. In general, these experiences may be associated with negative attitudes towards people with intellectual disabilities in the population and the resulting segregation of society [Citation46]. Unfortunately, in various countries, Covid-19 measures have further reduced participation rates in various life domains and reinforced segregation of vulnerable groups in society, including people with intellectual disabilities and mental illness [Citation24,Citation47]. Just as loss of work activities may reinforce the stigmatised identity and risk of social exclusion for people with mental illness [Citation48], this may also apply to people with intellectual disabilities. That is, in Western societies having a job is perceived as a major social role for people to fulfil [Citation49], while performing social roles is usually more difficult for people with intellectual disabilities due to the stigma attached to their disability [Citation50]. The work activities of the participants in this study usually offered them opportunities to perform valued aspects of social roles, such as making a difference to others. These activities also contribute to their identity and self-worth. In a qualitative study, Forrester-Jones & Barnes [Citation51] explored how providing social support to others could help individuals with severe mental illness to forge and manage a less stigmatised identity. They found that providing social support helped participants to construct a more socially valued identity than that of being a patient. In line with their findings, making a difference to others helped participants in this study to take on an accepted social role and escape the public stigma and they tried hard to find other ways to maintain this aspect of their lives while they had limited access to work activities. Both professionals and employers can support people with intellectual disabilities to find opportunities to provide social support to others, either in or outside the work situation, for example by helping out an elderly neighbour.

There are some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, due to the sudden introduction of a stricter lockdown, additional interviews were conducted and, as a result, either one or two interviews with the participants are included in this study. However, we have carefully accounted for this discrepancy in the analysis by using the data from the participants who were interviewed twice as the core dataset. Second, given the iterative nature of the IPA method, the literature recommends that the interviews should be conducted and analysed sequentially [Citation39]. However, due to the unpredictability of the pandemic and subsequent shifts in policy, and the fact that we specifically aimed to collect data in a context with severe restrictions, it was not possible to conduct the interviews sequentially. Lastly, it was not possible to carry out member checks to validate the preliminary results, a procedure applied in some IPA studies [Citation19] and absent in others [Citation52]. Previous studies have proved the valuable contribution of member checks. Nevertheless, in the ever-changing context of the pandemic, member checks proved not to contribute to the research validity: in a pilot member check the participant appeared to have difficulties recalling the experiences at the time of the interviews.

The findings of this study illustrate that the loss of social connections, in particular due to the lack of access to work activities, during the pandemic has reinforced the social inequalities and disadvantages for people with intellectual disabilities [Citation24,Citation47]. The group of people with intellectual disabilities is overlooked and forgotten in Covid-19 policies [Citation24], which can be seen as a result of the public stigma attached to this group [Citation53]. Interventions to address these inequalities and disadvantages are key, especially since a pandemic can reinforce conservative thoughts, stigmatisation and discrimination in the population [Citation47] and since the pandemic has not yet been entirely resolved and new lockdowns cannot be ruled out. It is therefore important to invest in sustainable and innovative post-pandemic community participation initiatives and particularly in accessible post-pandemic employment support to reinstall meaningful work activities for people with intellectual disabilities [Citation24]. There are workforce gaps in several sectors, and employers, together with healthcare professionals, can create opportunities to employ people with intellectual disabilities in these fields, for example by organising paid in-company training placements. In addition, more awareness should be raised among authorities, the general public and employers about the value of participation for people with intellectual disabilities, also in regular work activities. Public policies can be based on the philosophy of contributive justice by creating opportunities for everyone to use their talents to contribute to society rather than providing benefits [Citation54]. Moreover, in the event of new lockdowns, the results of this study could motivate public institutions to tailor policy decisions, considering both health risks and risks of social isolation. This could imply that day services for people with intellectual disabilities can remain open and that the visiting opportunities for people living in residential facilities persist, in compliance with applicable measures. By doing so, people with intellectual disabilities can be protected from health risks, while they can continue to benefit from social connections, which are such an important aspect of their lives.

This study contributes to the scientific knowledge by reporting in depth on the potentially adverse effects of long-term social restrictions on people with intellectual disabilities by depriving them from meaningful social connections through work activities. More research is needed to examine the effect of the loss of work activities, outside the context of a global pandemic with long-term social restrictions, for a larger group of people with intellectual disabilities. It would therefore be desirable to further explore the relationship between the loss of work activities, loneliness and mental health. In addition, considering the negative effect of Covid-19 on participation in employment of people with intellectual disabilities, it is important to investigate how this participation can be improved post-pandemic, for example by exploring partnerships between education, healthcare and companies. Finally, future research can examine how people with intellectual disabilities can use their ability to make a difference to other people’s lives to design their social roles and promote destigmatisation, for example by studying the perceptions of the clients and customers they serve.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the people with intellectual disabilities that participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. WHO; 18 March 2020 (No. WHO/2019-nCoV/MentalHealth/2020.1). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331490/WHO-2019-nCoV-MentalHealth-2020.1-eng.pdf.

- Courtenay P, Perera B. COVID-19 and people with intellectual disability: impacts of a pandemic. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(3):231–236.

- Doody O, Keenan PM. The reported effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with intellectual disability and their carers: a scoping review. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):786–804.

- Linehan C, Birkbeck G, Araten-Bergman T, et al. COVID-19 IDD: findings from a global survey exploring family members’ and pad staff’s perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and their caregivers. HRB Open Res. 2022;5:27.

- Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Our World in Data. 2020. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

- Giesbers SAH, Hendriks AHC, Hastings RP, et al. Family-based social capital of emerging adults with and without mild intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2020;64(10):757–769.

- Gilmore L, Cuskelly M. Vulnerability to loneliness in people with intellectual disability: an explanatory model. J Policy Practice Intellect Disabil. 2014;11(3):192–199.

- Vereniging Gehandicaptenzorg Nederland (VGN). Advies bezoekregeling gehandicaptenzorg [Advice visitation arrangement disability care]. Utrecht: VGN; 2020. https://www.vgn.nl/nieuws/advies-bezoekregeling-gehandicaptenzorg

- Embregts PJCM, Bogaard KJHM, Frielink N, et al. A thematic analysis into the experiences of people with a mild intellectual disability during the COVID-19 lockdown period. Int J Dev Disabil. 2022;68(4):578–582.

- Lake JK, Jachyra P, Volpe T, et al. The wellbeing and mental health care experiences of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities during COVID-19. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. 2022;19(1):35–47.

- Honingh A, Koelewijn A, Veneberg B, et al. Implications of COVID-19 regulations for people with visual and intellectual disabilities: lessons to learn from visiting restrictions. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2022;19(1):64–71.

- Puyaltó C, Beltran M, Coll T, et al. Relationships of people with intellectual disabilities in times of pandemic: an inclusive study. Soc Sci. 2022;11(5):198.

- Amor AM, Navas P, Verdugo MA, et al. Perceptions of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities about COVID-19 in Spain: a cross sectional study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;65(5):381–396.

- Ellenkamp JJH, Brouwers PM, Embregts PJCM, et al. Work environment-related factors in obtaining and maintaining work in a competitive employment setting for employees with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(1):56–69.

- Simoës C, Santos S. The impact of personal and environmental characteristics on quality of life of people with intellectual disability. Appl Res Qual Life. 2017;12(2):389–408.

- Bigby C, Bould E, Beadle-Brown J. ‘Not as connected with people as they want to be’: optimising outcomes for people with intellectual disability in supported living arrangements. Melbourne: Living with Disability Research Centre, La Trobe University; 2015. (ISBN: 9781921915673)

- Blick RN, Litz KS, Thornhill MG, et al. Do inclusive work environments matter? Effects of community-integrated employment on quality of life for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2016;53-54:358–366.

- Robertson J, Beyer S, Emerson E, et al. The association between employment and the health of people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32(6):1335–1348.

- Voermans MAC, Taminiau EF, Giesbers SAH, et al. The value of competitive employmetn: in-depth accounts of people with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(1):239–249.

- Donelly M, Hillman A, Stancliffe RJ, et al. The role of informal networks in providing effective work opportunities for people with an intellectual disability. Work. 2010;36(2):227–237.

- Lysaght R, Petner-Arrey J, Howell-Moneta A, et al. Inclusion through work and productivity for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2017;30(5):922–935.

- Bowring D, Totsika V, Hastings R, et al. Challenging behaviours in adults with intellectual disability: a total population study and exploration of risk indices. Br J Clin Psychol. 2017;56(1):16–32.

- Hall AC, Kramer J. Social capital through workplace connections: opportunities for workers with intellectual disabilities. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2009;8(3–4):146–170.

- Majnemer A, McGrath PJ, Baumbusch J, et al. Time to be counted: COVID-19 and intellectual and developmental disabilities – an RSC policy briefing. FACETS. 2021;6:1337–1389.

- Governor’s role in promoting disability employment in COVID-19 recovery strategies [internet]. National Governors Association. 2021 Mar 23 [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.nga.org/center/publications/governors-role-in-promoting-disability-employment-in-covid-19-recovery-strategies/

- Disability and employment, UK: 2019 [internet]. Office for National Statistics. 2019 Dec 2 [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/bulletins/disabilityandemploymentuk/2019.

- Berendsen E, van Deursen C, Dumhs L, et al. UWV Monitor Arbeidsparticipatie Arbeidsbeperkten 2020. Aan het werk zijn, komen en blijven van mensen met een arbeidsbeperking [EIA monitor labour participation of people with disabilities 2020. Being, entering and remaining in employment for people with a worklimitation]. Amsterdam; Uitvoeringsinstituut Werknemersverzekeringen [Employee Insurance Agency]: 2021.

- Holland P. Will disabled workers be winners or losers in the post-COVID-19 labour market? Disabil. 2021;1(3):161–173.

- Doyle L. ‘All in this together?’ A commentary on the impact of COVID-19 on disability day services in Ireland. Disab & Soc. 2021;36(9):1538–1542.

- Kim MA, Yi J, Sung J, et al. Changes in life experiences of adults with intellectual disabilities in the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(4):101120.

- Ontwikkeling in dagbesteding: Kansen en knelpunten [Development in day serivces: Opportunities and challenges] [internet]. Vereniging Gehandicaptenzorg Nederland [Dutch Organisation for Disability care]. 2021 Mar 15 [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.vgn.nl/documenten/rapportage-ontwikkelingen-dagbesteding-maart-2021

- Trip H, Northway R, Perkins E, et al. COVID-19: evolving challenges and opportunities for residential and vocational intellectual disability service providers. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2022;19(1):102–115.

- Handreiking dagbesteding in de gehandicaptenzorg [Manual on the provision of day time activities in disability care] [internet]. Vereniging Gehandicaptenzorg Nederland [Dutch Organisation for Disability care]. 2020 Oct 30 [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.vgn.nl/system/files/2020-10/Handreiking%20Dagbesteding%2030102020_0.pdf

- Boeije H, van Schelven F, Verkaik R. Gevolgen van coronamaatregelen voor naasten van mensen met een verstandelijke beperking. Onderzoek naar kwaliteit van leven tijdens de tweede golf [Effects of covid-19 measures on relatives of people with intellectual disabilities. Research on quality of life during the second wave]. Utrecht: Nederlands Instituut voor Onderzoek van de Gezondheidszorg [Dutch Institute for Healthcare Research]; 2021.

- de Klerk M, Oltshoorn M, Plaisier I, et al. SCP: Een jaar met Corona. Ontwikkelingen in de maatschappelijke gevolgen van corona [A Year with Corona. Trends in the social impact of corona]. The Hague: Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau [The Dutch Institute for Social Research]; 2021.

- Marrone J, Swarbrick M. Long-term unemployment: a social determinant underaddressed within community behavioral health programs. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(7):745–748.

- Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method & research. London: Sage; 2009.

- Schoufour JD, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K, et al. Development of a frailty index for older people with intellectual disabilities: results from the HA-ID study. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(5):1541–1555.

- Smith JA, Osborn M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Smith JA, editor. Qualitative psychology: a practical guide to research methods. London: Sage; 2008. p. 51–80.

- Lunsky Y, Jahoda A, Navas P, et al. The mental health and well-being of adults with intellectual disability during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2022;19(1):35–47.

- Schalock RL, Luckasson R, Tassé MJ. Intellectual disability: definition, diagnosis, classification, and systems of support. 12th ed. Washington (DC): American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; 2021.

- Parchomiuk M. Experiences of people with intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. A thematic synthesis. Int J Dev Disabil. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2022.2072698

- Purrington J, Beail N. The impact of COVID-19 on access to psychological services. AMHID. 2021;15(4):119–131.

- Nouwens PJG, Lucas R, Embregts PJCM, et al. In plain sight but still invisible. A structured case analysis of people with mild intellectual disability or borderline intellectual functioning. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017;42(1):36–44.

- Scheffers F, Van Vugt E, Moonen X. Resilience in the face of adversity in adults with an intellectual disability: a literature review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2020;33(5):828–838.

- Scior K. Public awareness, attitudes and beliefs regarding intellectual disability: a systematic review. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(6):2164–2182.

- Miltenburg E, Schaper J. Maatschappelijke gevolgen van corona. Verwachte gevolgen van corona voor de opvattingen en houdingen van Nederlanders [Social consequences of corona. Expected effects of corona on the views and attitudes of the Dutch population]. The Hague: Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau [The Dutch Institute for Social Research]; 2020.

- Oudejans SCC, Spits ME, van Weeghel J. A cross-sectional survey of stigma towards people with a mental illness in the general public. The role of employment, domestic noise disturbance and age. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56(9):1547–1554.

- Wolfensberger W. A brief overview of social role valorisation. Ment Retard. 2000;38(2):105–123.

- Dorozenko KP, Roberts LD, Bishop B. The identities and social roles of people with an intellectual disability: challenging dominant cultural worldviews, values and mythologies. Disabil Soc. 2015;30(9):1345–1364.

- Forrester-Jones R, Barnes A. On being a girlfriend not a patient: the quest for an acceptable identity amongst people diagnosed with a severe mental illness. J Ment Health. 2008;17(2):153–172.

- Giesbers SAH, Hendriks AHC, Jahoda A, et al. Living with support: experiences of people with mild intellectual disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32(2):446–456.

- Pelleboer-Gunnink HA, van Weeghel J, Embregts PJCM. Public stigmatization of people with intellectual disabilities: a mixed-method population survey into stereotypes and their relationship with familiarity and discrimination. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(4):489–497.

- Wilthagen T, Stolp M. De arbeidsmarkttrasitite: Naar meer waarde en meer werk [The labour market transition: towards more value and more jobs]. Arnhem: NSvP; 2021.