Abstract

Purpose

To describe how managers of employees on sick-leave, due to chronic pain conditions, experience participating in a three-party meeting using the Demand and Ability Protocol (DAP) in the return-to-work process.

Materials and methods

This study is based on individual semi-structured interviews with 17 managers of employees with chronic pain. Interviews were conducted after participating in a three-party meeting including the employee, manager, and a representative from the rehabilitation team. The data were analyzed using thematic analysis with an inductive approach.

Results

Two main themes were identified – “to converse with a clear structure and setup” and “to be involved in the employee’s rehabilitation.” The first theme describe experiences from the conversation, and the second theme reflected the managers’ insights when being involved in the employee’s rehabilitation. The themes comprise 11 sub-themes describing how the DAP conversation and the manager′s involvement in the rehabilitation may influence the manager, the manager-employee relationship, and the organization.

Conclusions

This study show, from a manager's perspective, how having a dialogue with a clear structure and an active involvement in the employee’s rehabilitation may be beneficial for the manager-employee relationship. Insights from participating in the DAP may also be beneficial for the organization.

A structured dialogue between the employee, employer, and rehabilitation supports the return to work (RTW) process

A structured dialogue and collaboration may strengthen the relationship between the manager and employee

An active engagement of managers in the employeès RTW process is beneficial for the manager-employee relationship, and for the organisation

Healthcare professionals should collaborate with the workplace to promote participation of managers

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Chronic musculoskeletal pain, often defined as pain present for more than three months, is common. Approximately 30–40% of the adult population in Sweden is likely to report chronic musculoskeletal pain in one or several sites of the body over a lifespan. It is more common among women, and the prevalence increases with age [Citation1,Citation2]. Globally, low back pain is one of the leading causes of years lived with disability [Citation3]. The clinical presentation of chronic musculoskeletal pain varies; moreover, for some individuals, the pain is so severe that it significantly impairs their ability to work.

In Sweden, musculoskeletal disorders are the second most common cause of sickness absence [Citation4]. Among pain patients at specialist interdisciplinary treatment clinics in Sweden, almost half can be expected to be on registered sick-leave [Citation5]. The process for a successful return to work (RTW) involves challenges not only for the employee on sick-leave but also for the employer, as well as the co-workers of the sick-listed employee [Citation6]. Workplace interventions are important for improving workability and for a successful RTW process [Citation7–11]. Furthermore, the collaboration and involvement of stakeholders, including the employer, are of importance for a successful and sustainable RTW [Citation10,Citation12–14]. According to employees on sick-leave due to back pain, a lack of collaboration or understanding from the manager has been expressed as one of the greatest obstacles for a successful RTW process [Citation15]. Facilitating factors for RTW include improvement of work environment, possibility of a gradual return to work, and understanding from the employer [Citation15]. One way to promote the employer’s involvement in the RTW process is to include them in a three-party meeting, where the employee, the employer, and a third party have a dialogue together. What role the third party should have, and the structure and focus of the dialogue, are likely of importance for the outcome [Citation16].

Most studies on the experiences from the RTW process have focused on the employee’s experience [Citation12,Citation17–21] and there are few studies that describe the employer’s experiences [Citation12,Citation22,Citation23]. A recent Swedish qualitative study investigated the managers’ experiences of a workplace oriented intervention enhancing a dialogue between the manager, the employee, and a rehabilitation coordinator in the RTW process, involving employees with stress-induced exhaustion disorder. The authors describe how the managers experienced that the dialogue helped in building competences, making adjustments, as well as promoting shared responsibilities with the employees [Citation23]. In a synthesis of qualitative studies, including the employees’ (individuals with chronic pain) and the employers’ perspectives on RTW, three core categories were identified – managing pain, managing work relationships, and making workplace adjustments. The authors of the synthesis also highlighted the importance of both the employee with pain and the organization having equal expectations for a successful process. Further, they concluded that there is a need to balance the needs of the individual with chronic pain, the work colleagues, and the work organization to have a successful RTW process [Citation22]. Several studies suggest there are benefits, for employees with pain conditions who RTW, when involving the manager in the process, as described by employees [Citation7,Citation14,Citation24–26] and managers [Citation22,Citation25–28]. Although knowledge about the managers’ perspective on being involved should be of relevance for a successful manager involvement, very few studies have focused on managers’ perspectives and experiences from accommodating employees with pain conditions [Citation27,Citation28] or taking an active part in the RTW process [Citation23].

Six steps have been suggested for managing work absence due to musculoskeletal disorders and a successful RTW process: (1) time off and recovery period; (2) initial contact with the worker; (3) evaluation of the worker and his/her job tasks; (4) development of a return-to-work plan with accommodations; (5) work resumption, and (6) follow-up of the return-to-work process [Citation29]. The Demand and Ability Protocol (DAP) is a protocol used in three-party meetings, which may be helpful for steps 3 and 4 in this process. The DAP considers work demands and the individual’s resources; moreover, during the conversation using the DAP, the employee and employer are to assess, reason, and agree upon the work demands in relation to the employee’s abilities [Citation20,Citation30]. A good balance between demands at work and the individual’s resources, including functional capabilities and motivation, is essential for a good workability [Citation31,Citation32]. The employeès experiences from participating in a three-party meeting using the DAP was described in a recent study [Citation20], however no study has investigated the managers experiences from using the DAP. The aim of the study was to describe how managers of employees on sick-leave, due to chronic pain conditions, experience participating in a three-party meeting using the Demand and Ability Protocol in the return-to-work process.

Materials and methods

This is a qualitative study based on data from individual semi-structured interviews with managers of employees who participated in a 5 to 6 weeks long interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program at one of two included pain rehabilitation units in Sweden. The interviews were conducted, on average, 1.9 months after participating in a three-party meeting using the Demand and Ability Protocol (DAP). All patients who started their pain rehabilitation at one of the included units between 2019 and 2021, who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, were approached for inclusion to the DAP intervention. In all, 30 employees (patients) and their managers participated in the DAP intervention, out of whom 17 participated in this interview study (see ). The study is reported according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) 32-item checklist [Citation33] to ensure trustworthiness.

Figure 1. Presenting the strategy for inclusion of participants in the study among managers of patients at the rehabilitation program who fulfilled the two presented inclusion criteria.

Setting

The DAP was included in the rehabilitation program and was conducted when the employee had been in the program for a few weeks. Most commonly, the DAP took place at the rehabilitation clinic; however, due to recommendations in conjunction with the Covid-19 pandemic, some DAP meetings were digital. The employee approached the manager for participation in the DAP. The engagement of the employee in this process was made purposely for the employee to take an active part in his/her rehabilitation. One meeting was planned for the DAP, without follow-up meetings. Occupational therapists who had received training in performing the DAP (in accordance with what is recommended for using DAP) led the meeting.

The Demand and Ability Protocol

The Demand and Ability Protocol (DAP) is an intervention based on a further development of the Dutch Functional Ability List [Citation34] and knowledge about disability in working life and is linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) [Citation35]. The purpose of using the DAP in a structured three-party meeting was to assess workability, in relation to the demands at the workplace, to make adequate adjustments at the workplace, and to promote RTW. The DAP was developed in Norway and is primarily used in occupational healthcare settings for assessments of a patient’s functional abilities in relation to his/her requirements at work through a structured dialogue [Citation20,Citation30]. The structured dialogue is held in a three-party meeting including the employee, his/her immediate manager, and a representative from the rehabilitation team (e.g., in this study, an occupational therapist).

The DAP is structured into 6 domains, assessing: 1) mental and cognitive ability, 2) basic skills and social ability, 3) tolerance for physical conditions, 4) ability to work dynamically, 5) ability to work statically, and 6) ability to work certain times. Detailed questions are asked around each domain to assess the balance between the employee’s abilities and the demands at work (). For each question, the employee and the employer should agree on the employee’s ability and the demands required at the workplace and rate them on a scale of 1 (low or none) to 3 (high). Areas where there is an imbalance between ability and demands can thus be identified and used for further planning or adjustments at the workplace. At the end of the protocol, there is a summary of the actions planned in relation to the employee’s RTW, including, e.g., joint decisions on potential workplace adjustments.

Table 1. A presentation of the six domains included in the DAP, number of items in each domain, and example of itemsa.

Participants

The managers were recruited by a consecutive sampling method [Citation36]. The criteria for inclusion were set according to the employee’s (patient’s) characteristics (see ). Since we aimed to assess the current demands at the workplace, the employee should not have been on full-time sick leave for more than six months prior to the rehabilitation program.

At the time of recruitment, the participants received oral and written information from the occupational therapist working at the rehabilitation clinic about the aim of the study and what participation would entail. They were also informed that they could withdrawal from the study at any time for any reason. All participants signed a written informed consent form.

In all, 19 managers initially agreed to participate in the study; however, two of them decided to drop out at the time of scheduling the interviews, one due to lack of time, and one did not respond to the invitation to schedule a time. The 17 managers who remained were interviewed by a member of the research group. Ten of the participants were women and seven were men. The managers had between 1 and 36 years of manager experience, and they were responsible for between 3 and 54 employees. See .

Table 2. Characteristics of participants.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted by occupational therapists, EJ (10 interviews), TH (3 interviews), and two occupational therapists from the rehabilitation program (4 interviews). Neither of the interviewers had participated in the DAP three-party meeting, nor been part of the rehabilitation team in the rehabilitation program. The interviews were held digitally (10), at the workplace (5), or at the rehabilitation clinic (2). All interviews were audio recorded and lasted between 16 and 49 min. An interview guide was used for the semi-structured interview, where the managers were asked to reflect on the structure of the DAP, experiences, outcomes, and lessons learned from participating in the three-party meeting using DAP (see full interview guide in appendix). To test the interview guide, it was piloted by the first interview. No significant changes were made to the guide after this interview, and thus the interview was included in the study.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board, D-nr 2019-01755 and 2020-00015.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using thematic analysis with an inductive approach [Citation37]. In accordance with what has been suggested for a thematic analysis, the process included six steps. In the first step, the interviews were transcribed, and the material was read and re-read to get familiar with the data. During this first step, the transcripts were imported to NVivo 12 for further processing, and notes were taken on initial ideas occurring when reading through the material. In a second step, initial codes were generated. The codes were labelled using words and phrases close to the transcript. All interviews were systematically reviewed and coded accordingly. Initially, one of the interviews was coded in a parallel process by both the first and last author to reach agreement. As for the rest of the interviews, the first author performed the coding but discussed them regularly with the last author. In a third step, when all interviews were coded, they were sorted based on the context and potential themes. All interviews were analyzed together in the third step to see common patterns of the individual codes, and to combine the codes into more general themes. In step four, the themes and codes were reviewed, going back and forth between the codes, themes, and transcripts. In the fifth step, the themes and sub-themes were discussed thoroughly among the authors. After a consensus had been reached, the themes and sub-themes were named. In a sixth and final step of the analysis, the report was produced, and the text describing the content of the themes and the sub-themes were produced; furthermore, a selection was made of the extract examples to support the themes and sub-themes. All authors contributed to the analytic process from step three and onwards by having regular discussions and critical reviews.

Results

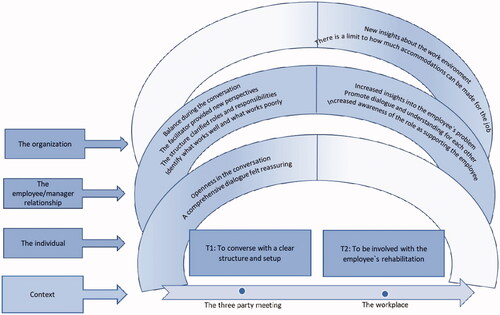

Two main themes were identified – “to converse with a clear structure and setup” and “to be involved in the employee’s rehabilitation.” The first theme describes how the managers experienced the actual conversation, and the second theme describes the managers’ insights, lessons learned, and changes that have emerged as a result of being involved in the employee’s rehabilitation. The first theme can be described as being in a context of the conversation as such, and the second theme in a context of the situation at the workplace after participation in the DAP. The two main themes comprise 11 sub-themes that reflect experiences from participating in the three-party meeting (). The sub-themes describe how the DAP conversation and involvement in the rehabilitation may influence the individual, the manager-employee relationship, and the organization ().

Figure 2. Describing the two main themes (T1 and T2), which contexts they are described within, the eleven sub-themes, and how they influence on an individual level, employee-manager relation, or organizational level.

Table 3. The analytical process identified two main themes and eleven sub-themes.

T1: to converse with a clear structure and setup

The first main theme involves experiences from the DAP conversation. The participants described DAP as comprehensive and detailed. This was, however, not necessarily considered to be a disadvantage. Instead, they described how this contributed to open, honest dialogues with a sense of balance in the conversation, where both the employee’s and the manager’s perspectives were raised on equal terms.

The managers also described how the structure contributed to the reasonings around new (for the manager) perspectives on the employee’s situation at work, and how the structure facilitated the identification and concretization of problem areas and potential interventions.

Openness in the conversation

The managers described how the clarity of the protocol made the dialogue objective, and it was easier for the manager to be open about the work demands. They described that the structure, where the facilitator led the conversation using pre-determined questions, made it easier to discuss the employee’s function in relation to work demands without feelings of discomfort, and with less risk of the employee feeling cornered or attacked. The structure also helped to clarify what the employee could manage and what worked well. The managers further described how the DAP conversation clarified the expectations of both the manager and the employee. One manager expressed how unrealistic expectations of each other can hinder the planning ahead:

….//it is really crazy if we have expectations of each other that will never be met, ….then it will irritate us in one way or another. So, what I mean is that first you must start by sorting out what is reasonable and what is not, and then take it from there. Because, somehow, if the work is sedentary, then I can’t adapt it to a job outdoors. It’s not possible; it’s not the position the co-worker has, although the co-worker may have a need for just that. In these cases, you need to discuss how you should proceed (Manager 17, 3 years experience as manager, manages 20 employees).

The managers described how the structure, the detailed form, and the presence of the facilitator contributed to a discussion and reflection, and a deeper understanding of the employee’s situation and disorder. They described how situations during the DAP conversation, when there was not an agreement, led to a discussion that deepened the knowledge and understanding of each other, through which they could then agree.

The managers expressed that it was advantageous that the facilitator was a person who knew the employee as a patient and had knowledge about the employee’s problems, and who could support the employee in describing his/her abilities.

A comprehensive dialogue felt reassuring

The concrete outcome from the dialogue was perceived as reassuring. The fact that it was a comprehensive dialogue, and that they went through the situation in detail, which enabled the identification of specified problem areas were perceived as reassuring by the managers as it gave a feeling that nothing had been overlooked. They expressed that this made their task addressing issues regarding the employee’s work environment easier.

The facilitator could help to unravel what needed to be more clearly highlighted. Also, the facilitator gave advice about adjustments that could make it easier for the employee, which the manager found very helpful. One manager expressed that it felt safe that the conversation was led by a person who had the perspective of a caregiver, that this person could see how we could make it easier for the employee, and which help aids could be useful.

The dialogue also confirmed that already ongoing work with work-environment and previous discussions between the manager and the employee about needs for interventions were relevant:

…//what became clear to me in this conversation [DAP] was that xxxx [employee] and I have identified relevant things together, what we need to work on, but we received help with a more concrete direction (Manager 18, 3 years experience as manager, manages < 20 employees).

The review also contributed to an identification of the interventions and adjustments that had already been made, including the aids already being used. In that way, it became a reminder of using the interventions that were already implemented.

Balance during the conversation

The managers experienced that the setup of the meeting contributed to a feeling of balance during the conversation. They appreciated that it was not only the employee’s perspective in focus, but that they could also raise their own expectations and needs from the manager’s perspective. The managers expressed that including both perspectives, including requirements from the manager, was important to be able to make adjustments at work that were important for the employee, but at the same time did not change the assignment the employee was hired to perform. They expressed that discussing the work demands or the employee’s abilities during the three-party meeting was not awkward. None of the participants mentioned any situation of conflict or bad atmosphere arising during the conversation.

I believe that the other conversations have been more focused on the employee. Yes, absolutely, it is always a combination of work and which work that should be done, but it is more like the co-worker who has been the one saying, “yes, how are you?”, and the central part around whom we should arrange everything around. Here, it was more like, “yes, but the work demands”. There was more of a balance in this conversation somehow (Manager 3, 3 years experience as manager, manages >20 employees).

The managers felt that the facilitator helped to clear up any misunderstandings, invited the parties to speak up, and kept everything in order. They viewed the facilitator as a neutral party in the conversation, a person that was impartial and that could help guide the discussion forward when the manager and the employee had different opinions or judgments. They felt that this neutrality helped to achieve a balance during the conversation, where the facilitator had the task of creating a balance rather than taking a stand.

The presence of three parties in the conversation was perceived as a balancing act, and it contributed to an open climate that was not characterized by their roles. The conversational climate also contributed to a co-creation between the manager and the employee:

….//That’s how I felt. I felt it was a very open meeting, it was like, we, no one, we were, it was the three of us who sat there that had to find a goal together, not that we were a manager on one side and a co-worker on the other side. I mean, that was not how we worked; instead, we worked together so that we laughed sometimes because it was like that (Manager 14, < 3 years experience as manager, manages >20 employees).

One manager expressed that a conversation that only aims to discuss work adjustments can make the manager feel cornered.

Identify what works well and what works poorly

The managers expressed that the detailed form facilitated finding all parts and extracting the work demands and the employee’s abilities. The managers described how it became clear through the conversation what aspects of the work the employee had difficulties with, but also which parts worked well. Some managers expressed that the detailed form with several parts made it clear that there was quite a lot that worked well for the employee, which the manager believed was important to acknowledge for the employee’s self-esteem.

The structure was described by the managers as a checklist where the employees and the managers could check the boxes for which parts were relevant to work with further, resulting in a clear plan from which to work. The strategy to go through the work situation in detail and concretize those parts where problems usually appear contributed to highlighting that also smaller, simpler interventions may be meaningful. Even if the managers had discussed the need for work adjustments and support on previous occasions, this conversation made it more hands-on, and also highlighted small but meaningful details:

Yes, but now it became more hands-on somehow. I know that it’s these things that are…We have discussed that previously, and I have adjusted her workdays so that it will be as helpful as possible for her. But this was also like, how can you help her even more, a bit more like the finishing touch, if that is how you say it (Manager 10, < 3 years experience as manager, manages < 20 employees).

The facilitator provided new perspectives

The managers viewed the facilitator as having an important role by guiding and moving the conversation forward. By explaining and asking related questions, the discussion was deepened and the possibility of reaching a conclusion around concrete problem areas or interventions increased. The managers described how the facilitator, who was an external party could contribute with new perspectives and facilitate the manager and employee to open up to new perspectives. The facilitator could help to acknowledge what was already done and what could be done differently. One manager expressed that the facilitator could help to steer away from habitual thoughts that had evolved during previous discussions about the employee’s work situation. Hearing the new thoughts from the facilitator, which helped to highlight the questions from a different perspective, the manager and the employee could find new ways forward in their work:

When xxx [the employee] steers into old habits, then the person from the care unit [facilitator] comes in and says, “no, but we looked at this. Is this really like this or that?” Do you see what I mean? That one can get help to focus correctly and not drift off towards something, if I look at it, I believe that it is something that would benefit xxx situation, but when you hear the third perspective, which helps, then you realize that no, that is not what we should do. Let’s do it this way instead (Manager 18, 3 years experience as manager, manages < 20 employees).

The structure clarified roles and responsibilities

The managers expressed how the structure made it clearer what responsibility the manager and employee had, respectively, to promote a healthy work situation for the employee and how they both should act to move forward. The clear structure made it easier to identify and specify parts that were of importance, as well as which parts were the manager’s and the employee’s responsibility to approach. One example that was raised, was that it became clear where the manager had to support the employee in changing behavior (e.g., to take on more work than is expected), and to encourage the employee to decrease the work-pace or lower the ambitions. One manager expressed that it was good that it became clear that the employee also had a responsibility in changing his/her behavior, and that it was not only the manager’s responsibility to make changes:

Yes, to help her with the things she needs help with, that it was more specified, it wasn’t so unclear. It was more clear which things that are important to address and what’s her responsibility and what’s mine (Manager 10, <3 years experience as manager, manages < 20 employees).

T2: to be involved with the employee’s rehabilitation

The second main theme describes how the managers perceive their participation in the DAP conversation has influenced their relationship with the employee and their thoughts about the environment at the workplace. The managers described how they gained insights and understanding for the employee’s problems by participating in the employee’s rehabilitation and the DAP. They further described how the dialogue between the manager and the employee had changed and become clearer after the DAP. An increased understanding for each other was mentioned as one aspect, in explaining why the dialogue had changed. The managers expressed that their participation in the employee’s rehabilitation made the manager more aware of his/her role in supporting the employee.

The manager’s involvement in the rehabilitation also gave new insights about the work environment, for the employee, and for the workplace overall. They also raised the issue that there are limitations on how extensive workplace adjustments could be made without changing the work assignment.

Increased insights into the employees’ problem

The managers described how participating in the conversation improved the relation to the employee; that the manager got to know the employee better; and gained an understanding of, and knowledge about, the disorder the employee had and his/her situation at work. The managers described how they gained an understanding of the employee’s disease, both psychologically and physically, and which work tasks were painful for the employee. The three-party meeting also allowed for an increased understanding of why the employee had been away from work so much.

The managers gained increased insights on what the employee could manage through the three-party meeting, which enabled new ways of thinking about adjustments and work interventions. Even if the employee and the manager had already been talking about what he/she can manage and not manage in their work before the rehabilitation and the DAP, the three-party meeting gave the manager a deeper understanding of what the pain disorder meant for the employee:

….//I think it became quite clear what kind of work and which work tasks that can be extra difficult for xxx [employee]//….//What kind of work tasks that can be painful//… (Manager 13, > 3 years experience as manager, manages > 20 employees).

Involvement in the rehabilitation and the DAP allowed the manager to gain an increased understanding of the work-situation as a whole. Specifically, the manager could understand the emotional demands that the employee perceived at work and the complexity of the work tasks. One manager expressed how difficult it is as a manager to get the full picture of the employee’s work situation.

Promote dialogue and understanding for each other

One manager expressed that one lesson learned from the three-party meeting was that there is a need for clearer communication around the cognitive work demands, and not only the physical demands as in previous dialogues between the manager and the employee. Another manager expressed how the dialogue between the manager and the employee has been clearer after the three-party meeting and that they now can discuss the employee’s work situation in a more concrete manner. The manager’s participation in the rehabilitation process has made the manager more aware of the work situation for the employee, but also, at some level, opened up for thoughts about how other employees at the workplace experience their situation:

Then, there’s a great deal of responsibility on her to really do what she has decided to do and I can support her in that. But, of course, since we are in this process now; it may be that I unconsciously or consciously open up a little for how others experience it. I get reminded of it because I am in that process…maybe a little bit (Manager 8, 3 years experience as manager, manages > 20 employees).

Participation in the DAP led to that the employee and the manager having a greater understanding of each other and each other’s perspective. One manager expressed that this could be important for a better dialogue between them in the future:

…so I sort of think that the dialogue between us can become even better in the future actually, thanks to this (Manager 12, > 3 years experience as manager, manages < 20 employees).

The managers believed that the employees thought it had become easier to speak up and ask for help when needed, that he/she felt it was acceptable to do that now. The increased trust between the manager and the employee after the three-party meeting has given the manager a mandate to interfere and point out to the employee when he/she falls into a behavior that is not favorable, and to highlight the need for prioritization. The manager also felt that the employee had an increased understanding of this, when the manager needs to interfere and point out certain things in his/her way of working.

Increased awareness of the role as supporting the employee

Due to the DAP, the manager became aware that the employee needs support from the manager to change a behavior that is not favorable for his/her health, that he/she needs support to hold back, or to work ergonomically. They expressed that this is an important role for the manager. It could, e.g., involve making the employee aware of his/her behavior, even small things, thus reminding the employee. One manager described how she is now more aware of how she can act to not exacerbate the employee’s feelings of stress, and that she has become more aware of which signals the employee sends out:

No, I have to pay a bit more attention not to push her so much. Because I understand now that she is reluctant to say no or to speak up when it becomes too much; instead, she pushes herself. And you could say that I will pay more attention to those signals and think in a different way (Manager 12, > 3 years experience as manager, manages < 20 employees).

One manager expressed that her participation in the employee’s rehabilitation and in the discussions that were held during the DAP made it more legitimate for the employee to change a behavior. She added that the employee may feel safe since they have discussed this together, that he/she may understand the need to change a certain behavior, and feel that it is all right for them to change their behavior.

The managers also described that participating in the DAP gave insights to the employee’s rehabilitation process and the challenges the employee faces in terms of returning to work. It may be challenging for the employee to maintain and practice what he/she brought from the rehabilitation. One manager expressed that it is important that the manager intercepts and supports the employee during this process so that the work started by the employee’s rehabilitation will not be undone:

I also think it is a good way. I mean, if you should think about the economic aspects; it is five weeks, it’s a really long time; it’s an investment from several directions, and then if you miss out on the employer, then you have missed out on something, that is where the person should act. So, from that perspective, it feels very positive, from a socio-economical perspective…. (Manager 8, 3 years experience as manager, manages > 20 employees).

New insights about the work environment

The managers expressed that the insights they gained regarding the employee’s need for aids and work adjustments are experiences to be used in their work around the work environment for the rest of the organization. One manager described how the discussions about demands at work gave him new insights on how aids may make it easier for more employees in the working group:

…because when you ask these questions about demands and so, on a scale, like, it was a lot like this and what can you do to change the things that were less good….I mean to be able to make it better, not only for xxx, but for others, like as help aids and things like that. That may be an insight you don’t really think about. You tend to think only about the person who is in pain; you don’t think about the others who may get that after a while if they don’t get some help aids. So, it’s maybe something you think about a bit more (Manager 2, > 3 years experience as manager, manages < 20 employees).

Others expressed how the interventions that had been implemented at the workplace will be helpful for other employees as well, and how lessons learned and tips about ergonomics that the employee learned from the rehabilitation spill over to more people in the work group.

One manager expressed how she used the lessons learned from being involved in the rehabilitation when planning for changes in the organization, where she, already at the planning stage, could see possible risks and thereby design the changes differently, with the aim to prevent an adverse work environment for the employee.

The managers further described how they use experiences from the clearly structured form in DAP when communicating with other employees, and that it may be a good way for the employees to explain their situation. Another expressed how she can use the structure in conjunction with new recruits, for a clearer communication about the demands at work.

There is a limit to how much accommodations can be made for the job

The managers pointed out several different adjustments that had been made after the three-party meeting to improve the physical or psychosocial work environment. Some described how different organizational changes had been made, e.g., regarding possibilities to work from home, or to work in other groups.

The managers raised the issue that it may be bothersome with adjustments, that there are limitations to how many adjustments can be done without changing the assignment that the employee was hired to do. The managers believe that the employees understand this limitation regarding adjustments at work:

But then, since some of the things we can’t adjust since you work in a school, and as a teacher. We both agree upon that, that these are difficult, but if you can’t perform that, then we can’t work to 100%, because then you can’t be like, full-time (Manager 14, < 3 years experience as manager, manages > 20 employees).

Discussion

The aim of the study was to describe how managers, of employees on sick-leave due to pain conditions, experience participating in a three-party meeting using the DAP in the RTW process. Two main themes, “To converse with a clear structure and setup” and “To be involved in the employee’s rehabilitation,” were identified. The first theme related to how the managers experienced the actual conversation, and the second theme reflected the managers’ insights, lessons learned, and changes that emerged when being involved in the employee’s rehabilitation.

The managers described how the structure of the DAP helped to identify what works well and what works poorly, and that the structured protocol contributed to clarifying roles and responsibilities. Apart from providing a structured evaluation of the worker and his/her job tasks, these two aspects may also influence the relationship between the manager and the employee. Furthermore, several other aspects emerged when the managers described their experiences from having a dialogue with a clear structure and being involved in the employee’s rehabilitation, which imply that the DAP may promote a successful RTW and have an impact at the individual level, in the relationship between the manager and the employee, and at an organizational level.

The managers’ experiences from using the DAP suggest benefits for the manager at an individual level by reassuring the managers that they fully capture the problem through the comprehensive protocol. Furthermore, the managers described how the structure contributed to an openness in the conversation, how the objective discussions made it easier for them to be open and honest about the work demands, and that the conversation was not only focusing on what the manager should do to enable RTW for the employee, but also on the managers’ perspective in relation to the work demands. The feeling of security among the managers, the openness and honesty during the dialogue, as well as the mutual responsibility have been highlighted in a recent Swedish study by Eskilsson et al. among managers who had participated in a dialogue-based intervention for RTW. It is also in line with the results from a French study, where the managers expressed a wish to be heard regarding restrictions on ergonomic recommendations for employees with pain conditions [Citation27].

The managers’ descriptions of the insights and lessons learned from the DAP to bring to the workplace (described by theme 2) suggest that the lessons learned may be beneficial on an organizational level by having new insights on work environment that is applicable for the workplace and not only for the employee in question. This phenomenon that involvement of the manager influences the manager’s way of taking preventive actions targeting other employees was also seen in another recent Swedish study [Citation23]. The study was performed in a setting of RTW of employees with stress-induced exhaustion disorder, investigating managers’ experiences from another dialogue-based intervention. One of the main findings from their study suggests that managers gain competence and capacity to act from being involved in the employee’s RTW process [Citation23]. It has previously been suggested that managers of employees with chronic pain conditions lack competence in pain management and RTW [Citation38], and the findings from our study together with previous studies [Citation23] indicate that involving the manager in the employee’s rehabilitation may increase their competence and confidence in the complex RTW process. In the study by Eskilsson et al. the more established method Convergence Dialogue Meeting (CDM) was used [Citation23,Citation39]. The CDM and DAP are similar in that they strive for initiating a dialogue between the patient and the supervisor to find solutions to facilitate RTW. One of the main differences between the two methods are however the structure of the protocols, where the DAP has a more detailed structure, based on work demands and abilities [Citation39].

The lessons learned and insights from being involved in the RTW process and the DAP are likely of importance for a sustainable RTW for the employee in question, and workability among employees with health problems in the long-term perspective. Previous studies have described how the manager’s role in applying organizational strategies can act as facilitators or barriers for employees working with health problems [Citation25,Citation40]. Altogether, this suggests that involving managers in one employee’s rehabilitation may have long-term positive consequences for the whole organization. And that the manager can find the involvement to be beneficial also for them as individuals.

The results from our study further suggest that having a dialogue with a clear structure and setup using the DAP and being involved in the employee’s rehabilitation is beneficial for the relationship between the employee and the manager. Similar findings were presented by Eskilsson et al. [Citation23]. A good relationship and collaboration between the manager and the employee have been highlighted as important for a successful RTW in several studies [Citation12,Citation15,Citation25,Citation26,Citation40–43]. The managers expressed how the structure of the DAP and the presence of the facilitator gave them new perspectives. They also described how the structure led to an openness in the conversation, and how they could discuss the demands at the workplace more objectively. This openness may also allow for new perspectives for both the manager and the employee, and possibly promote a better dialogue between them further on. Previous studies have described how managers experienced that flexibility among the manager and the employee facilitated the interaction during the RTW process [Citation41] and that creating confidence between the supervisor and the employee, and making demands on the employee is important for a successful RTW [Citation42]. Further, employees have highlighted a lack of understanding from the manager as an important obstacle to returning to work [Citation15].

Previous studies have described how managers have expressed a wish to be involved in their employee’s rehabilitation [Citation26], and the results from our study indicate that involvement may be beneficial from several aspects. However, the managers also highlighted how adjustments of the workplace can be bothersome, since there is a limit to how many adjustments can be made without changing the assignment that the employee was hired to do. Concerns among managers in relation to workplace adjustments, and the expectations and demands around accommodations that are perceived among the managers, have also been expressed in previous studies [Citation22,Citation26–28]. It is possible that an active involvement of the manager in the rehabilitation process and an open and honest dialogue around work demands and ability may facilitate the job accommodations. These potential effect however, needs to be investigated in future quantitative studies.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, only one previous study [Citation23] has described managers’ experiences from participating in a dialogue-based intervention. Although that study was performed in a different setting, with a different intervention and including managers of employees with stress-induced exhaustion disorder [Citation23], there are many similarities to our study. Overall, many aspects that are highlighted in our study were found also in the study by Eskilsson et al. [Citation23], although expressed by using somewhat different themes. This strengthens the credibility of the results from our study. Another strength is that the participants of this study represent the voices of a variety of managers regarding age, gender, sector, years of experience being a manager, and number of employees. However, it is possible that those who agreed to participate in the DAP and in the interview, in general, may be more engaged in their employee’s RTW, and thus may not be fully representative for managers in general, which is a limitation of this study. The managers in this study were overall positive to the DAP, and the lack of negative experiences may be a result from this potential selection bias. Another limitation is that some of the interviews were held digitally, and some were conducted in real life. There can be both pros and cons with using digital interviews – a richer material can be obtained concerning sensitive topics, but body language can be difficult to read [Citation44]. In this study, we could not see any difference between the interviews that were conducted digitally regarding duration or in quality. The rather long time of (on average) two months between participating in the DAP and the interviews may also be a limitation, due to potential recall bias. However, this period may also have given the manager some time to consider what impact participation in the DAP may have had, which is described by the second main theme.

In this study we chose to only include managers of employees who had not been on full-time sick leave for more than six months. However, this limit was set based on speculative basis, to keep the group somewhat homogenous with regard to the employeès possibilities for a successful RTW. Overall, there is no reason to believe that experiences from participating in the DAP would be vastly different if the employee had been on sick leave for longer, as long as the requirements at work were still relevant.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates several aspects of the managers’ experiences from having a dialogue with a clear structure and an active involvement in the employee’s rehabilitation that may be beneficial for the manager-employee relationship. Further, the results imply that insights and lessons learned from participating in the DAP may also be beneficial for colleagues in the organization. An active involvement of the manager in the rehabilitation, e.g., by using DAP, may be beneficial for a successful and sustainable RTW, and it may strengthen the managers in their work with job accommodations and work environment.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (17 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the individuals who participated in the study and the occupational therapists at the interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program for recruiting eligible participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aili K, Campbell P, Michaleff ZA, et al. Long-term trajectories of chronic musculoskeletal pain: a 21-year prospective cohort latent class analysis. Pain. 2021;162(5):1511–1520.

- Harker J, Reid KJ, Bekkering GE, et al. Epidemiology of chronic pain in denmark and sweden. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:371248.

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259.

- Social Insurance Agency. Social Insurance in figures 2021. 2021. https://m.forsakringskassan.se/wps/wcm/connect/11bc72d6-4bbb-4893-8a3b-c9e9eae568f8/social-insurance-in-figures-2021.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=

- LoMartire R, Dahlström Ö, Björk M, et al. Predictors of sickness absence in a clinical population with chronic pain. J Pain. 2021;22(10):1180–1194.

- Tjulin A, Maceachen E, Ekberg K. Exploring workplace actors experiences of the social organization of return-to-work. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(3):311–321.

- Cullen KL, Irvin E, Collie A, et al. Effectiveness of workplace interventions in return-to-Work for musculoskeletal, Pain-Related and mental health conditions: an update of the evidence and messages for practitioners. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(1):1–15.

- Oakman J, Neupane S, Proper KI, et al. Workplace interventions to improve work ability: a systematic review and meta-analysis of their effectiveness. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2018;44(2):134–146.

- Sennehed CP, Holmberg S, Axén I, et al. Early workplace dialogue in physiotherapy practice improved work ability at 1-year follow-up-WorkUp, a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Pain. 2018;159(8):1456–1464.

- Carroll C, Rick J, Pilgrim H, et al. Workplace involvement improves return to work rates among employees with back pain on long-term sick leave: a systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(8):607–621.

- van Vilsteren M, van Oostrom SH, de Vet HC, Cochrane Work Group, et al. Workplace interventions to prevent work disability in workers on sick leave. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;5(10):Cd006955.

- Liedberg GM, Björk M, Dragioti E, et al. Qualitative evidence from studies of interventions aimed at return to work and staying at work for persons with chronic musculoskeletal pain. JCM. 2021;10(6):1247.

- Nastasia I, Coutu MF, Rives R, et al. Role and responsibilities of supervisors in the sustainable return to work of workers Following a Work-Related musculoskeletal disorder. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31(1):107–118.

- Etuknwa A, Daniels K, Eib C. Sustainable return to work: a systematic review focusing on personal and social factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(4):679–700.

- Dionne CE, Bourbonnais R, Frémont P, et al. Obstacles to and facilitators of return to work after work-disabling back pain: the workers’ perspective. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(2):280–289.

- Holmlund L, Sandman L, Hellman T, et al. Coordination of return-to-work for employees on sick leave due to common mental disorders: facilitators and barriers. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2020;5:1–10.

- Strömbäck M, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Keisu S, et al. Restoring confidence in return to work: a qualitative study of the experiences of persons with exhaustion disorder after a dialogue-based workplace intervention. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0234897.

- Azad A, Svärd V. Patients’ with multimorbidity and psychosocial difficulties and their views on important professional competence for rehabilitation coordinators in the return-to-Work process. IJERPH. 2021;18(19):10280.

- Svärd V, Friberg E, Azad A. How people with multimorbidity and psychosocial difficulties experience support by rehabilitation coordinators During sickness absence. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:1245–1257.

- Johansson E, Svartengren M, Danielsson K, et al. How to strengthen the RTW process and collaboration between patients with chronic pain and their employers in interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs? Patients’ experiences of the Demand and Ability Protocol. Disab Rehabil. 2022;10:1–8.

- Svanholm F, Liedberg GM, Löfgren M, et al. Factors of importance for return to work, experienced by patients with chronic pain that have completed a multimodal rehabilitation program - a focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(5):736–744.

- Grant M, Ob-E J, Froud R, et al. The work of return to work. Challenges of returning to work when you have chronic pain: a meta-ethnography. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e025743.

- Eskilsson T, Norlund S, Lehti A, et al. Enhanced capacity to act: managers’ perspectives when participating in a Dialogue-Based workplace intervention for employee return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31(2):263–274.

- Peolsson A, Hermansen A, Peterson G, et al. Return to work a bumpy road: a qualitative study on experiences of work ability and work situation in individuals with chronic whiplash-associated disorders. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):785.

- Wynne-Jones G, Buck R, Porteous C, et al. What happens to work if you’re unwell? Beliefs and attitudes of managers and employees with musculoskeletal pain in a public sector setting. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(1):31–42.

- Jakobsen K, Lillefjell M. Factors promoting a successful return to work: from an employer and employee perspective. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21(1):48–57.

- Grataloup M, Massardier-Pilonchéry A, Bergeret A, et al. Job restrictions for healthcare workers with musculoskeletal disorders: consequences from the superior’s viewpoint. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(3):245–252.

- Williams-Whitt K, Kristman V, Shaw WS, et al. A model of supervisor Decision-Making in the accommodation of workers with low back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(3):366–381.

- Durand MJ, Corbière M, Coutu MF, et al. A review of best work-absence management and return-to-work practices for workers with musculoskeletal or common mental disorders. Work. 2014;48(4):579–589.

- Engbers MF. Funksjonsvurdering på arbeidsplassen, et hjelpemiddel ved spesialvurdering i regi av bedriftshelsetjenesten. Test av Krav og Funksjonsskjema i praxis. Slutrapport till NHO Arbetsmiljöfondet Projekt S-2387. Oslo. 2006.

- Ilmarinen J. From work ability research to implementation. IJERPH. 2019;16(16):2882.

- Ilmarinen J, Tuomi K, Klockars M. Changes in the work ability of active employees over an 11-year period. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23(Suppl 1):49–57.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Brouwer S, Dijkstra P, Gerrits E, et al. Intra- en inter-beoordelaarsbetrouwbaarheid ’FIS-belastbaarheidspatroon’ en ‘functionele mogelijkheden lijst’ [English: intra- and Inter-Rater Reliability – Functional Information System and Functional Ability List]. Tijdschrift Voor Bedrijfs- en Verzekeringsgeneeskunde. 2002;11:360–367.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Geneva, 2001.

- Polit DB. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia, 2012.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Cunningham C, Doody C, Blake C. Managing low back pain: knowledge and attitudes of hospital managers. Occup Med. 2008;58(4):282–288.

- Karlson B, Jönsson P, Pålsson B, et al. Return to work after a workplace-oriented intervention for patients on sick-leave for burnout–a prospective controlled study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:301.

- Buck R, Porteous C, Wynne-Jones G, et al. Challenges to remaining at work with common health problems: what helps and what influence do organisational policies have? J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(4):501–512.

- Jansen J, Boot CRL, Alma MA, et al. Exploring employer perspectives on their supportive role in accommodating workers with disabilities to promote sustainable RTW: a qualitative study. J Occup Rehabil. 2022;32(1):1–12.

- Holmgren K, Dahlin Ivanoff S, Ivanoff SD. Supervisors’ views on employer responsibility in the return to work process. A focus group study. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(1):93–106.

- Jansen J, van Ooijen R, Koning PWC, et al. The role of the employer in supporting work participation of workers with disabilities: a systematic literature review using an interdisciplinary approach. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31(4):916–949.

- Thunberg S, Arnell L. Pioneering the use of technologies in qualitative research – A research review of the use of digital interviews. Inter J Soc Res Methodol. 2022;25(6):757–768.