Abstract

Purpose

The study objective was to investigate how health care providers in stroke teams reason about their clinical reasoning process in collaboration with the patient and next of kin.

Materials and methods

An explorative qualitative design using stimulated recall was employed. Audio-recordings from three rehabilitation dialogs were used as prompts in interviews with the involved staff about their clinical reasoning. A thematic analysis approach was employed.

Results

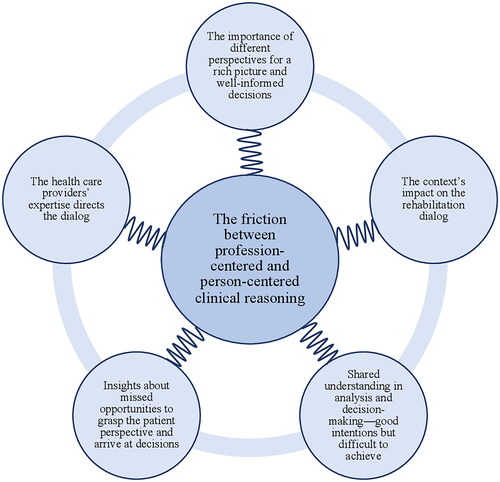

A main finding was the apparent friction between profession-centered and person-centered clinical reasoning, which was salient in the data. Five themes were identified: the importance of different perspectives for a rich picture and well-informed decisions; shared understanding in analysis and decision-making – good intentions but difficult to achieve; the health care providers’ expertise directs the dialog; the context’s impact on the rehabilitation dialog; and insights about missed opportunities to grasp the patient perspective and arrive at decisions.

Conclusions

Interprofessional stroke teams consider clinical reasoning as a process valuing patient and next of kin perspectives; however, their professional expertise risks preventing individual needs from surfacing. There is a discrepancy between professionals’ intentions for person-centeredness and how clinical reasoning plays out. Stimulated recall can unveil person-centered practice and enhance professionals’ awareness of their clinical reasoning.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

The findings provide insights into the clinical reasoning process of interprofessional stroke teams, which can increase awareness and support the development of competencies among health care providers.

To increase patient participation in the clinical reasoning process, stroke teams are recommended to clarify the function of goals and the decision-making process in management.

Stimulated recall is recommended as a reflective activity in the work of stroke teams to develop awareness and skills in clinical reasoning performed in collaboration between health care providers and patients.

Introduction

Recent developments in research on clinical reasoning (CR) and person-centered care suggest more involvement between professions and greater participation from patients [Citation1–3]. However, achievement of intended levels of participation is difficult in everyday clinical practice [Citation4–6]. Further insights into how health care providers conceive their CR may shed light on challenges and provide key information to further professional and organizational developments.

CR is described as the cognitive processes that health care providers engage in to make clinical decisions guiding their clinical practice [Citation7]. More elaborate descriptions of CR also include contextual, collaborative, and person-centered dimensions [Citation8–11]. Information gathering, interpretation of data, and management planning are key components of CR; goal setting and outcome evaluation are often also included [Citation8,Citation12,Citation13]. In complex clinical health care situations, such as caring for people recovering from stroke, health care providers must be competent in reasoning jointly to provide accurate assessments and effective management. The varying consequences of stroke such as motor, cognitive, and language impairments, limitations in daily life activities, role fulfillment, social participation, and an often long-term rehabilitation in different settings challenge the CR process. Furthermore, difficulties in self-management and coping with everyday problems may result in negative effects on patients’ quality of life and increased burden on family members [Citation14]. Thus, different professional perspectives [Citation15], patient [Citation4] and next of kin involvement [Citation6] are fundamental to meeting stroke survivors’ individual needs.

CR in different health professions share similar components; however, the underlying perspectives and questions raised may be profession-specific. In medicine, the focus is on diagnosis, i.e., a biomedical perspective, and management reasoning, i.e., a biopsychosocial perspective [Citation16]. Cognitive representations of diseases developed by experience, i.e., illness scripts [Citation17] are used by physicians to interpret and predict biomedial information to arrive to a diagnosis. Script activation as part of the CR implies information gathering from the patient, for example concerning their signs and symptoms [Citation18]. The activation of scripts thus implies interaction, which allows them to emerge. CR within the nursing context addresses reasoning patterns to arrive at a nursing plan of care [Citation12], in which noticing and interpreting signs and symptoms, and patient interaction are central [Citation19]. Physical and occupational therapists place movement, function, and occupation in the center of their CR together with a collaborative and holistic view [Citation8,Citation11,Citation13]. When diverse professions work together in teams, the sharing of profession-specific information and information retrieval from team members are essential processes for a collaborative CR approach [Citation2]. Thus, CR is rarely performed individually; it includes the integration of diverse professional views and an approach to engage the patient in the process.

A person-centered approach includes respectful, holistic, individualized, and coordinated care where persons are empowered to participate in health decisions [Citation20,Citation21]. The inclusion of the patient as an equal partner in the team characterizes a person-centered approach in interprofessional teamwork and a cocreation process between professionals, patients, and relatives to arrive at shared care and management decisions [Citation22]. Such interaction is paramount in improving patient satisfaction [Citation23] and maximizing rehabilitation efficiency [Citation24]. Health care providers often perceive their care to be more person-centered than their patients [Citation25,Citation26], and a lack of team collaboration results is associated with a disempowering stroke rehabilitation process [Citation15], which requires further investigation.

Although patient participation has been advocated as a strategy for improved person-centered care, its implementation has been challenging to achieve in practice [Citation4]. Stroke survivors’ participation can, and should, be expected to be expressed differently in acute and rehabilitation phases of stroke care [Citation5], and several areas for improvement have been identified [Citation6,Citation26–28]. Two areas for improvement are goal setting and management decisions; patients who are more involved in these processes and decisions are more satisfied, motivated, and achieve better functional outcomes [Citation26,Citation29]. If used efficiently, rehabilitation dialogs (RD), in which the patient, next of kin, and the interprofessional team come together and discuss goals and rehabilitation interventions, have the potential to be a powerful tool to promote patient participation.

To fully understand how patients with stroke are involved in reasoning and decisions in RDs the thought processes and intentions of involved health care providers should be brought to the fore. Based on the hidden nature of these cognitive processes, the CR of interprofessional teams is best achieved by letting them reflect and think aloud about their actions and interactions in the dialogs. The current study aims to investigate how health care providers in stroke teams reason about their CR process in collaboration with the patient and next of kin.

Methods

Study design

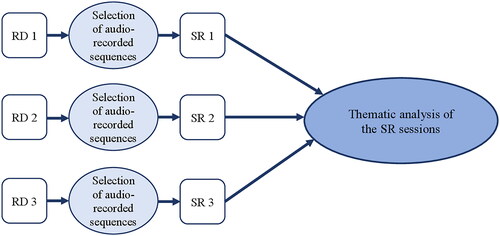

This study is positioned within the interpretivist research tradition and employs an explorative qualitative design using audio-stimulated recall (SR) [Citation30] as a method in interviews about CR performed in RDs. An overview of the study design is presented in . The study is part of a larger project focusing on professional and patient perspectives on person-centeredness in CR in the stroke context. SR sessions were also held with the patient to capture the patient perspective. These findings will be analyzed and reported separately.

Figure 1. Design of data collection and analysis. Audio-recorded sequences from rehabilitation dialogs (RD) were selected as a basis for stimulated recall (SR) sessions, which were analyzed with thematic analysis.

Setting and participants

The setting was an outpatient stroke rehabilitation unit located at a hospital in a Swedish middle-sized city. The rehabilitation is based on interprofessional teams of physicians, reg. nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech therapists, psychologists, social workers, and dieticians. The patients are of working age and have the capacity to participate in rehabilitation 2–3 days per week. The length of the rehabilitation is approximately 8 weeks, but the period can differ based on patient needs. RDs with the stroke team, the patient, and next of kin (optionally) are held continuously during the rehabilitation period, the first one after 1–2 weeks and then monthly, with a minimum of 3 RDs during a rehabilitation period. The 30-min RD focuses on the patient’s illness, psychological, physical, and social capabilities, and progress. The interprofessional team is trained to follow a certain structure in the RD including identification of patient resources and barriers, goals for rehabilitation, planning of management strategies, and evaluation of care and rehabilitation. The RD results in a rehabilitation plan that is documented in the patient record. The patient prepares answers to questions regarding resources, obstacles, and short- and long-term expectations. The RD is led by a physician or a reg. nurse on the stroke team.

A reg. nurse at the unit identified eligible persons with stroke who participated in ongoing rehabilitation. We aimed to include patients of various ages, sex and in different phases of the rehabilitation period. Patients with severe cognitive impairments, aphasia, or a lack of ability to speak the local language (Swedish) were excluded. Three patients and their next of kin were asked about participation and agreed to participate in the study. The health care providers who constituted the stroke teams and were responsible for the three patients’ rehabilitation were also invited and agreed to participate in the study. Three RDs were considered appropriate to achieve sufficient data depth and breadth for the study aim.

Data collection

Health care providers within interprofessional stroke teams, patients with stroke, and next of kin were audio-recorded during RDs. The recording was used in a subsequent interview with the involved health care providers to instigate a SR and encourage the participants to explicitly communicate their CR. SR is a method in which cognitive processes can be investigated by using video or audio recordings as prompts for persons to recall their concurrent thinking during a specific event. Compared to persons’ narratives about an event, which can be limited to what the person remembers and reports, the stimulus of replaying sequences within an interview context may enhance recall accuracy and completeness [Citation30]. SR has been extensively used in research into physician–patient consultations and decision-making since the method provides insights into the CR behind actions [Citation31].

Three RDs were audio-recorded, each followed by an SR session where selected recorded sequences were replayed and prompting questions were posed to the stroke team. The first author (ME) observed the RDs and made reflective notes. Before the RD started, ME informed the participants about the study, her role as a researcher, and stated that no questions should be asked during the RD. After each RD, the research team analyzed the audio recording. The researchers independently listened to the audio-recordings and selected sequences that considered aspects of patient participation, nonparticipation, and professional interactions related to components of CR. The selected sequences were compared and discussed to achieve consensus regarding the most appropriate sequences to be used in the SR session. In the final selection of sequences, the team considered variations in who was talking and variations in the CR components in focus. Five to six sequences per RD, with a length between 17 s and 2.5 min, were selected. These sequences are summarized in Appendix A.

The SR sessions occurred 7–10 days after the RD and were audio-recorded and conducted with ME and MP present. ME led the session using an interview guide for structural support (Box 1). MP made reflective notes and asked follow-up questions when needed to achieve rich data. The SR session started with ME introducing the method of using audio-recorded prompts to stimulate recall, with the aim of reflecting and exchanging thoughts rather than answering specific questions, implying that the participants could ask and respond to each other’s thoughts and descriptions and that there were no right or wrong answers. The selected audio-recorded sequences were replayed one by one, followed by prompting questions to explore the health care providers’ thoughts, intentions, and reflections regarding their actions and interactions with each other, the patient, and the next of kin. The RD and SR sessions were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber.

Reflective questions used in the SR sessions

The questions were preceded by audio-recorded sequences from the rehabilitation dialog.

Please describe your thoughts and actions in the situation we listened to.

What made you think and act in the way we just heard? Tell us about what happened in the situation and your thoughts about it.

Can you elaborate on your thoughts about the patient’s participation in this event? What in the situation was important to enable patient participation?

How does the team think and reason together in this event? Are there any differences between the collective thinking of the team and individual health care providers?

What do you think will be the consequences of the event we listened to? For you as a team? For the patient?

Data analysis

A thematic analysis in six steps according to Braun and Clark was conducted [Citation32]. The SR sessions constituted the unit for data analysis. First, the research team listened to and read the transcripts of the SR sessions to familiarize themselves with the data. Second, ME, in discussion with the team, selected meaningful segments in the data regarding the health care providers’ thoughts and reflections about their actions and generated initial codes. This step included a constant comparison with the related transcripts of the RDs to put data from the SR session into a context. Third, ME, in discussion with the team identified themes, which implied analyzing, comparing, and sorting codes of the SR sessions across the dataset. Fourth, the themes were reviewed by the research team to develop focused, rich, and diverse themes reflecting the meaning of the data. Fifth, ME described the themes narratively and selected key extracts illustrating features of the themes. Sixth, further refinements of the analysis and theme names were made by the team during manuscript writing. In addition, the total time that the staff, patient, and next of kin talked at the RDs, including silence, was calculated to describe their respective space in the conversation, which could provide further understanding of the prerequisites for patient participation in CR. This added descriptive analysis did not form a part of the thematic analysis.

Ethical considerations

The staff, patients, and next of kin were informed verbally and in writing about the study, that participation was voluntary, and that data were treated confidentially. Written informed consent was collected from all participants. Audio-recordings of the RDs, instead of video-recordings, were selected to secure the personal integrity of patients and next of kin. The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2021-02926).

Results

All health care providers who attended the RDs also participated in the SR sessions, except for one who was sick at the time of the SR session. In total, 14 health care providers participated in the three SR sessions, four of whom participated in two RD/SR sessions, i.e., there were, in total, ten individuals (seven women and three men) participating in the SR sessions. The health care providers’ working experience ranged from half a year to 30 years with a mean of 12 years. The three participating patients were diagnosed with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Two were men, and one was a woman. The patients’ age ranged from 51 to 61 years. The time since the patients experienced the stroke was between 1.5 and 7 months. A detailed description of the participants is presented in .

Table 1. Participants in the rehabilitation dialog (RD) and stimulated recall (SR) sessions.

The total proportion of time spent talking at the RDs ranged from 45–51% for the professional team, 36–49% for the patient, and 13–18% for the next of kin.

The analysis of the SR sessions resulted in five themes, which together unveiled a friction between profession-centered and person-centered CR (see ). The themes describe how the teams struggle for a person-centered approach, but the profession-centered approach is often in the foreground and directs the conversation. Thus, a friction arises between different needs in the CR. In the results, the themes are presented as narratives including quotes, and the text in brackets presents the SR session and the audio recorded sequence from the RD that was in focus for the reflection. A description of the audio-recorded sequences is presented in Appendix A.

Figure 2. Overarching theme and themes.

Theme 1: the importance of different perspectives for a rich picture and well-informed decisions

The RDs were initiated with open questions to invite the patient to talk about their situation, capacity, and the consequences of having experienced a stroke. According to the team’s reflections, the goal was to highlight the patient’s resources to use these as motivators in the rehabilitation. Wide and open questions provided an understanding of the patient’s prioritizations in the current situation. Confirmation from the team through humming and nodding supported the patient to telling their story.

I think it’s great to do that [ask about resources], because many patients find it a bit difficult to put into words what they can do. And they say they can’t do anything./…/You can hear about what areas the patient perceive are important. This facilitates for us to think further in the rehabilitation and what we should focus on. (SR 2; Sequence #7)

The team paid attention to and valued the perspective of the next of kin in complementing the patient’s perspective. This information provided descriptions of challenges in the patient’s daily life, which guided further questions and decision-making in the RD. The team highlighted the importance of seeking confirmation from the patient after listening to the view of the next of kin.

Yes, he/she [the next of kin] said straight away that he/she was the one who experienced this with memory difficulties. And he/she was the one who had written it on the note too. So, I think it was very good that you [another team member] turned towards the patient and asked how he/she felt. (SR 2; Sequence #9)

The patient and team perspectives shifted throughout the RDs. The team expressed that they wanted to listen to the patient’s and next of kin’s experiences and then share their expertise with the aim of increasing the understanding of a situation or problem. The health care providers’ experiences of similar patients enabled recognition of symptoms and signs, which contributed to improved interpretation. By listening to the RDs, the team reflected that their different professional expertise was important in the assessment of realistic patient goals. They also expressed how the interactions within the team gave clues about further important profession-specific examinations.

I’m starting to think about whether there are more tests you can do, based on what you [another team member] mention with the brain fatigue as well. I think, ‘but I need to assess this too’. (SR 3; Sequence #15)

Theme 2: shared understanding in analysis and decision-making—good intentions but difficult to achieve

Several sequences in the RDs included the team’s, patient’s, and next of kin’s joint effort to understand the patient’s problem, such as impaired physical or psychological functions and limitations in daily activities. The team considered it important to connect the patient’s experiences of a problem with their knowledge to determine their agreement. Disagreement was a prompt for the team to provide more information, such as disease- and symptom-specific information and examination results, and further explain their interpretation. The team explained how the view of participating next of kin enriched the understanding, sometimes to the extent that the patient’s view became blurred. Shared understanding was sought by asking the patient and next of kin to confirm the team’s interpretation.

Yes, it’s like, you must sort it out so that you talk decently about the same thing, if you think that’s important. (SR 1; Sequence #2)

Feedback on examination results was perceived as an important means to involve the patient in the rehabilitation. The team sought to avoid the use of medical terms, such as diagnoses, to avoid causing the patient unnecessary worry. Instead, they tried to express their reasoning with everyday terms and describe the manifestation of the diagnosis for this unique patient. When a patient expressed knowledge of stroke and rehabilitation, this was seen as a resource and a challenge by the team. On the one hand, the patient provided valuable input on understanding the problem; on the other hand, the team doubted their competence and certainty in decision-making.

A great deal of the RDs focused on patient goals. The team perceived that their role was mainly to transform the patient’s goals to be measurable, something that the team worked with during the RD, but also after the meeting. The team stressed the importance of arriving at a shared understanding of the goal, i.e., what it means and what causes the patient’s current difficulties. As they listened to their reasoning about goals, they were alerted to the fact that a deficient analysis of the patient’s problem resulted in unclear goals. In turn, this deficiency resulted in uncertainty about goal achievement.

I was confused about the goal of ‘being able to write’. I thought it was about him/her having some processing difficulty with the language. And then you started to talk about motor difficulties. So, I didn’t understand what it was about. That’s what I remember I was thinking when you talked about that goal. (SR 1; Sequence #1)

The team stressed their intention to involve the patient in the planning of treatment and training. They invited the patient to contribute their own suggestions based on their abilities, for example, cognitive capacity. The greater the patient knowledge and awareness of the problem was, the greater their role in decision-making was. The team also reflected on the difficulty in involving a patient in management decisions when there was a discrepancy between the patient’s high ambition and the team’s limited resources. In such situations, the team’s judgment superseded the patient’s wishes.

It’s good to have a discussion, what do you [the patient] think we should do? Can you solve this? And we solve the other. Yes. I think it is very important. Whenever possible. (SR 3; Sequence #16)

RDs performed later in the rehabilitation period included evaluations of goals and treatment outcomes. The team expressed difficulties making room for the patient’s and the team’s views in the conversation. They stressed the value of highlighting both the patient’s subjective experiences and the team’s objective outcome measures, but the team mostly favored the objective evaluation to clarify improvements or declines.

I think that we play with this all the time, with objective, hard measures. Although it is very difficult./…/And then to make room for the patient’s subjective experience. That’s like a form of validation and confirmation, that you feel that things move in a certain direction./…/I think, what do you [the patient] want? How do you want us to evaluate your goal? How do you want to notice that you are getting better? We don’t talk about that very often. (SR 1; Sequence #5)

Theme 3: the health care providers’ expertise directs the dialog

The team expressed the importance of compliance with the patient’s story and needs in the RD, but the audio recordings alerted them to an often professional-controlled dialog. The team was keen to ask the patient about situations they perceived important to discuss based on their previous experiences with similar patients and their greater knowledge of the disease and rehabilitation. The team expressed a view of patients lacking insights about their situation, e.g., difficulty understanding the consequences of cognitive deficits or having realistic thoughts about recovery time, reinforcing a professional-driven conversation. To open the dialog too much was perceived as risking deviation from the team’s agenda.

Yes. We are very, very controlling. Even though we’re empathetic and listening too, we provide a lot of structure. (SR 1; Sequence #1)

There were situations in the RD when the view of the next of kin was not considered, and the team moved on to the next question. In these cases, the team perceived their view as more accurate or more in line with the patient’s view, which explained why they ignored the next of kin’s view.

I think, that was no big problem, as we experience. I think … it becomes a bigger problem for his/her next of kin, that’s another thing. Maybe that’s something to deal with in another way. (SR 2; Sequence #9)

In discussions about goals and goal achievement, the team reflected on their needs and actions. Long-term goals, expressed by the patient at the beginning of the rehabilitation period, were not further discussed, as the team perceived them as low priority at this early stage of the period. Their actions were described as ways to focus the conversation on goals that were important for the team and specific health care providers, for example, goals related to movement for the physiotherapist or goals related to speech abilities for the speech therapist.

Yes, one way could be to steer the patient in the direction we prefer, towards the goal that we have chosen to discuss, or towards the part of the rehabilitation plan that we want to focus on. To get there, at once. Instead of meandering all the way there. As we would have otherwise done, if we had just let the conversation flow, and … we’ve had the lovely, open questions. (Laughter). Like we’re just drifting around in the ocean, until we find an island. (SR 2; Sequence #1)

Evaluation of goals was discussed to a large extent in the RD performed late in the rehabilitation period. The team expressed the importance of discussing goal achievement from the view of the health care provider mostly involved in the management. In the RD the team wanted to first express their view of goal achievement and then ask about the patient’s view. Furthermore, they expressed that their use of objective tests for evaluation was to confirm or disconfirm the patient’s own experience of goal achievement.

I think, I don’t know… in the conversation, he/she [the patient] is telling his/her subjective experience “I think I have gotten worse”. But you as a professional say “We haven’t made any measurements on this yet”. We only have his/her experience so, that’s why you can’t answer. (SR 1; Sequence #5; RS 1)

Theme 4: the context’s impact on the rehabilitation dialog

Some sequences evoked thoughts about a lack of structure in the dialog. The team found it difficult to know when to express thoughts about the patient’s problem or suggest management decisions since they were unsure when and how to articulate their point of view. The time frame of 30 min for the RD was perceived as challenging for involving the patient. For example, details could seldom be discussed, even if perceived as urgent for the patient. The team also stressed that the RD should be considered part of a longer process, including planning and decision-making at other team meetings and individual patient encounters.

I think it is hard to know when to present your thoughts in the conversation, and what goals you should discuss. For me, it is not very clear how the structure of these dialogs should be. (SR 3; Sequence #13)

The team expressed that the lack of clarity in the RD was caused by the team being in-sufficiently prepared, which caused confusion in the conversation with the patient. Awareness of each other’s competencies and personal characteristics, such as body language, allowed the team to interact and understand unspoken signs.

We know each other and each other’s peculiarities well. So, you know roughly how to play together. And it usually works quite well (RS 1; Sequence #1)

When discussions about short- and long-term goals were in focus, the team expressed difficulty interpreting these terms, which caused ambiguity in decision-making. The team did not agree about their definitions and realized that the time frame for short-term goals was not clearly described for the patient. Some health care providers perceived long-term goals as fully patient-centered and indicated that the team should not discuss whether they are realistic. Others reflected on the conflict between setting long-term goals that are important for the patient and having a time-limited rehabilitation period, which could result in unachievable goals. When such long-term goals were included, it was difficult to use the goal for management planning, and there was a risk of unrealistic expectations about treatment outcomes and the time of the rehabilitation period.

I’m thinking, when he/she [the patient] wrote the note, does he/she know what short and long-term goals mean? How short is short-term?/…/That’s a good thought, maybe it needs to be a clarified what is short term and what is long term? (SR2; Sequence #10)

Theme 5: insights about missed opportunities to grasp the patient perspective and arrive at decisions

The SR sessions provided insights to the team regarding opportunities in the RD when the patient expressed a will or a problem that they had not noticed. For example, new and important information that was mentioned briefly or somewhat hidden in a longer patient story. Such missed opportunities were explained by difficulties understanding nuances, interpreting patient information, and prioritizing the most important information. Unclear questions from the team could also result in ambiguity in understanding and dealing with the patient’s answer, resulting in a lack of team response. At the end of one of the dialogs, the patient summarized their will as follows: “All I want is to be healthy again”, which the team reacted to by nodding and giggling but asked no follow-up questions. The team reflected that this was a summary of what the patient had already expressed in other ways during the dialog, something that many patients express as their ultimate goal but also that they were not sure of the patient’s intention with the statement.

Yes, and then you can think about what he/she means by healthy. Does he/she thinking of starting to work again? Then I’m healthy, or? (SR 2; Sequence #12)

The RDs focused on many activities that the patient wanted to be able to perform, but when listening to the dialog the team realized that few wishes were transferred into specific short-term goals.

We didn’t say, we’ll take this as a short-term goal. It’s not clearly expressed that what is written on the note about what the patient wants to achieve will be a goal. You need to look at that later. You will sum up, but we didn’t sum up anything this time. (SR 2; Sequence #10)

Long-term goals were also brought up by the patient that were not grasped and discussed by the team.

I kind of think that we, okay, we hear what you’re saying, but… it’s not really relevant right now. (SR 2; Sequence #11)

Nonspecific goals were a source of confusion for the patient, next of kin and team, as they resulted in ambiguity regarding what should be achieved and how. The team reflected that the discussion about performed and planned interventions became nonspecific when goals were unclear,.

Because it was… it was not a SMART goal from the beginning. No, this was diffuse, as if we didn’t really find out what exactly he/she wanted to achieve. (RS 1; Sequence #2).

When listening to the RDs, the teams reflected on the lack of discussion summaries and clear management decisions. Long discussions could end without any further plan or conclusion. According to the team, these actions were sometimes conscious when they needed to move forward, but could also be unconscious when the conversation became complex and difficult to articulate.

So, there is, there is a lot going on, which is maybe not expressed. (SR 3; Sequence #17)

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate how health care providers within stroke teams reason about their CR process in collaboration with the patient and next of kin. In summary, CR moved back and forth between a profession-centered and person-centered process. The reasoning was characterized by good prerequisites and intentions for involving the patient in a collaborative CR process. However, the reflections revealed gaps between intentions to focus on patient needs and wishes and practice, including a professional-controlled dialog. The observed talking times were approximately equally distributed across the professional team and the patient and the next of kin. Although not a measure of person-centeredness per se, half of the talking time provides opportunities for the patient to express needs and react to the health care providers’ views in the dialog.

CR was influenced by different perspectives contributing to a rich and valuable collective perspective of the patient’s problem and situation. The environment was characterized by respect and empathy, and everyone was allowed to speak and share experiences, thoughts, and suggestions. These aspects are emphasized as key dimensions in person-centered care [Citation20,Citation21] and provide a foundation for a partnership between health care providers and patients [Citation33]. Although most current models of CR include the patient perspective and highlight shared decision-making, building a person-centered foundation early in patient encounters is rarely explicitly described. Rather, person-centeredness is nested in descriptions such as “social interactions” [Citation16], “the right reason,” i.e., considering the patient perspective [Citation12], and “a biopsychosocial approach” [Citation8,Citation11]. Although established CR models, such as illness scripts formation [Citation17,Citation18], include patient interaction, the focus is on biomedical information and diagnosis and not on complex clinical reasoning about care and rehabilitation in collaboration with the patient. Thus, our findings highlight the complexity of CR in the stroke rehabilitation context and the need for elucidation of person-centered aspects, e.g., meaningful relationship building, as part of CR models.

The RD followed a standardized agenda, which invited the patient and next of kin to share their experiences; however, the conversation was directed toward a professional-driven agenda and individual health care providers’ needs. Thus, the findings revealed a discrepancy between the extent to which the team valued the patient perspective and its integration into the RD. From a CR perspective, the team needs to collect data to make well-informed decisions in diagnosis and management planning [Citation16], which motivates the teams’ actions. However, the patient and next of kin have an experience of the illness that is unique, and the patient, not the health care providers, experiences the consequences of stroke. This discrepancy raises questions about roles in RD. Whose needs are in the foreground: those of the individual health care providers, the team, or the patient? Moore and Kaplan [Citation34] present a framework for a shared decision-making process highlighting the roles and actions of the health care provider and the patient, respectively. In preparation for collaboration, the health care provider and patient determine which decisions need to be made and which the patient prioritizes. The exchange of information about goals and management options is emphasized, and congruence between patient priorities and available options is determined. In decision-making on goals and management, the patient has an active role summarizing the plan and raising concerns [Citation34]. Our findings demonstrate that the patient’s preparation before the RD supported collaboration and that missed opportunities to capture patient perspectives and arrive at decisions counteracted collaboration. Clarifying decided goals and management plans and asking the patient to summarize information and decisions, so-called teach-back, may be a way forward. The use of teach-back has been shown to support patient autonomy, shared decision-making, and self-management abilities [Citation35], which can clarify ambiguities in health care providers’ perspectives but requires mechanisms to emphasize the person’s needs and preferences to align with a person-centered approach in CR. Collaboration and dialogue to capture the patient perspective in CR also requires consideration of the patient’s level of health literacy, i.e., skills that enables individuals to obtain, understand, and use information to make health-related decisions [Citation36]. To enable patients to participate more fully in the CR process patients need to understand what involvement means and appreciate that they have a valuable contribution to make to the process given their experiences. Research demonstrates that education and training about how to support development of patients’ basic health-literacy skills are needed for both patients and health care provider [Citation37].

Patient goals were central in the conversation and contributed to a CR process driven by patient needs. However, some goals were profession specific instead of originating from the individual patient’s needs. Similarly, Levack et al. [Citation38] demonstrated that patient-centered goals in stroke rehabilitation are difficult to achieve, as certain goals are prioritized by the team, for example goals toward physical function and short-term goals. Furthermore, when patient and prioritized goals do not align, the team tends to turn the conversation toward familiar prioritized goals. Such interactional dilemmas arose in the current study when health care providers neglected long-term goals and directed the conversation toward short-term goals and issues they perceived as most important. In contrast to the findings of Levack et al. [Citation38], where goals and management did not align, goal setting in the current study was used as an activity to influence management and, thus, a component of the CR process. According to our findings, goals must be based on a careful analysis and understanding of the patient problem to be useful for the management plan. Dekker et al. [Citation39] have suggested a hierarchical model of goal setting to improve patient motivation for rehabilitation where the patient’s fundamental beliefs, goals, and attitudes are explored to set a meaningful overall rehabilitation goal followed by specific rehabilitation goals related to the overall goal. Elvén et al. [Citation8] stress that goals are not single events, but are integrated into the CR process. Patient needs and wishes must first influence assessment; after arriving at a diagnosis or problem formulation, the patient wishes should be transformed to specific goals that guide management. Thus, the integration of goal setting in the CR process in stroke rehabilitation is complex and requires a shared understanding of the definitions and functions of goals within the team. The importance of educating staff and patients about the goal setting process is emphasized in the literature [Citation26].

In rehabilitation, person-centeredness goes beyond person-professional dyads since it includes interactions within interprofessional teams, including the patient and relatives [Citation40]. The current study findings highlight the value of including the patient, different professional perspectives, and contextual barriers to effective teamwork, such as organizational deficiencies and different views on goals. Similarly, Légaré et al. [Citation41] identified time constraints and lack of training as barriers and motivations for including the patient as part of the interprofessional team. Information must be well distributed among team members at the starting point of the reasoning process to support collaboration in CR within interprofessional teams; additionally, individual team members must strive to retrieve information from other team members [Citation2]. Furthermore, the importance of clarifying of roles, and promptly investigating patient preferences is emphasized [Citation42], and a decision coach who can support the patient’s involvement in decision-making is suggested [Citation41].

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study is that the use of SR allowed us to unveil the CR processes of stroke rehabilitation teams, which normally remains largely hidden. The trustworthiness of findings [Citation43] was considered in several ways in data collection and data analysis [Citation44]. The risk of social desirability in the health care providers’ responses was countered by emphasizing the value of their experiences, reflections, and confidentiality. The interviews were rich in content and the informants expressed that it was valuable to reflect on own and others’ actions in the RDs, which improved the credibility of data. Furthermore, the careful and collaboratively performed data selection of the RDs and data analyses of the SR sessions improved the credibility. The researchers represented different professions and were all involved in the analyses, contributing to various perspectives on data and reducing the risk of researcher bias. Confirmability was enhanced by describing the selected audio sequences of the RDs that were used in the SR sessions and by using quotes to demonstrate the grounding of the findings in the data.

Some limitations of the study need to be highlighted. One limitation is the number of RD/SR sessions included in the study, which may have limited variations in the data and affected the study findings. However, the SR sessions were characterized by a respectful relationship between the participants and researchers, which supported reflections and interaction among the team members and resulted in rich data. This study was conducted in a specific Swedish stroke rehabilitation setting, including stroke teams of health care providers who knew each other well and followed an established plan for RD. Thus, the results and conclusions are applicable to similar situations and settings, and the description of the setting provides other researchers with data to assess the transferability of the results to adjacent settings. Another limitation may be the selection of sequences in the RDs. As these were used as prompts in the SR sessions other sequences might have resulted in other reflections of the team. However, the sequences were carefully selected by the research team to include different aspects of participation and that all health care providers were heard in the recordings. The use of audio recording instead of video recording as prompts in the SR could be a limitation. Video recordings could have better revealed interactions among staff and patients by capturing nonverbal behaviors [Citation31]. On the other hand, video recordings might have compromised integrity and increased the risk that health care providers would refuse to participate.

Implications for practice and research

First, the study findings will contribute to the scientific community’s understanding of CR as it is used in stroke rehabilitation and interprofessional teams. Second, from a practice perspective, the findings will contribute to health care providers’ competency development. Third, the study contributes to future research by suggesting SR methods to provide new insights and awareness of actions that may be implicit.

Even though the patient perspective is valued in the CR process of stroke teams, there remain issues to be considered to integrate person-centeredness more fully. Above all, stroke teams must clarify the function of patient goals and the process of shared decision-making in management planning to support patients as active partners in rehabilitation. From a learning perspective, the SR sessions provided the team with insights and “aha experiences” about the content and quality of their CR. The method stimulated the team to raise questions about different professional perspectives in the reasoning, involvement of the patient and next of kin, and organizational facilitators and barriers for team interaction. Although SR is a research method, it also utilizes metacognition, i.e., “thinking about your thinking,” which is necessary to transform experience into learning [Citation45]. The use of SR can be a way for interprofessional teams to highlight professional roles, interactions, and patient participation and improve their CR. Such a learning approach could include repeated SR sessions guided by a facilitator, where key features in the CR process can be identified, discussed, developed through training, and evaluated. To achieve such professional development, time and support from the organization is needed.

Conclusions

The findings reveal that professional stroke rehabilitation teams reason about their CR as a process in which patient and next of kin perspectives are valuable for understanding and managing patient problems; however, they consider that direct questions and interpretations are necessary aspects of their professional expertise. Furthermore, there is a discrepancy between health care providers’ intentions for person-centeredness and how their CR plays out in RDs. The friction between a profession-centered and person-centered CR process is evident; however, it is difficult for professionals to grasp in practice. One way forward is the use of SR to unveil person-centered practice and identify strengths and weaknesses in CR. The method can be used for research and local development to enhance professional awareness. Goal setting within CR is a fruitful way to further develop person-centeredness in stroke rehabilitation. Such work requires shared understanding between team members and patients about the definitions and function of goals in the stroke setting.

Author contributions

ME, MP, IKH, and SE each made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. ME collected data at the RDs. ME, MP, IKH, and SE analyzed and selected audio-recorded sequences from the RDs. ME conducted the interviews at the SR sessions assisted by MP. ME, MP, IKH, and SE analyzed and interpreted the data. ME wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Madeleine Örnberg, Sofia Berglind Sernander, and Birgitta Martinsson for assisting with the recruitment of participants for the study. We are also grateful to the stroke teams who contributed their thoughts and reflections to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Paxino J, Denniston C, Woodward-Kron R, et al. Communication in interprofessional rehabilitation teams: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(13):3253–3269. doi:10.1080/09638288.2020.1836271.

- Kiesewetter J, Fischer F, Fischer MR. Collaborative clinical reasoning - a systematic review of empirical studies. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37(2):123–128. doi:10.1097/CEH.0000000000000158.

- Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):Cd006732. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub4.

- Yun D, Choi J. Person-centered rehabilitation care and outcomes: a systematic literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;93:74–83. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.012.

- Elvén M, Holmström IK, Carlestav M, et al. A tension between surrendering and being involved: an interview study on person-centeredness in clinical reasoning in the acute stroke setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2023;112:107718. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2023.107718.

- Lloyd A, Bannigan K, Sugavanam T, et al. Experiences of stroke survivors, their families and unpaid carers in goal setting within stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(6):1418–1453. doi:10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003499.

- Higgs J, Jensen GM, et al. Clinical reasoning: challenges of interpretation and practice in the 21st century. In: Higgs J, Jensen GM, Loftus S, editors. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2019. p. 3–11.

- Elvén M, Hochwälder J, Dean E, et al. A clinical reasoning model focused on clients’ behaviour change with reference to physiotherapists: its multiphase development and validation. Physiother Theory Pract. 2015;31(4):231–243. doi:10.3109/09593985.2014.994250.

- Hege I, Adler M, Donath D, et al. Developing a European longitudinal and interprofessional curriculum for clinical reasoning. Diagnosis (Berl). 2023;10(3):218–224. doi:10.1515/dx-2022-0103.

- Durning SJ, Artino ARJ, Schuwirth L, et al. Clarifying assumptions to enhance our understanding and assessment of clinical reasoning. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):442–448. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182851b5b.

- Huhn K, Gilliland SJ, Black LL, et al. Clinical reasoning in physical therapy: a concept analysis. Phys Ther. 2019;99(4):440–456. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzy148.

- Levett-Jones T, Hoffman K, Dempsey J, et al. The ‘five rights’ of clinical reasoning: an educational model to enhance nursing students’ ability to identify and manage clinically ‘at risk’ patients. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(6):515–520. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2009.10.020.

- Matthews LK, Mulry CM, Richard L. Matthews model of clinical reasoning: a systematic approach to conceptualize evaluation and intervention. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2017;33(4):360–373. doi:10.1080/0164212X.2017.1303658.

- Jaracz K, Grabowska-Fudala B, Górna K, et al. Consequences of stroke in the light of objective and subjective indices: a review of recent literature. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2014;48(4):280–286. doi:10.1016/j.pjnns.2014.07.004.

- Hartford W, Lear S, Nimmon L. Stroke survivors’ experiences of team support along their recovery continuum. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):723. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4533-z.

- Cook DA, Durning SJ, Sherbino J, et al. Management reasoning: implications for health professions educators and a research agenda. Acad Med. 2019;94(9):1310–1316. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002768.

- Schmidt HG, Rikers RM. How expertise develops in medicine: knowledge encapsulation and illness script formation. Med Educ. 2007;41(12):1133–1139.

- Charlin B, Boshuizen HPA, Custers EJ, et al. Scripts and clinical reasoning. Med Educ. 2007;41(12):1178–1184. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02924.x.

- Tanner CA. Thinking like a nurse: a research-based model of clinical judgment in nursing. J Nurs Educ. 2006;45(6):204–211.

- Håkansson Eklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, et al. “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(1):3–11. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.029.

- Langberg EM, Dyhr L, Davidsen AS. Development of the concept of patient-centredness - a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(7):1228–1236. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.023.

- Ebrahimi Z, Patel H, Wijk H, et al. A systematic review on implementation of person-centered care interventions for older people in out-of-hospital settings. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(1):213–224. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.08.004.

- Quaschning K, Körner M, Wirtz M. Analyzing the effects of shared decision-making, empathy and team interaction on patient satisfaction and treatment acceptance in medical rehabilitation using a structural equation modeling approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):167–175. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2012.12.007.

- Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47(6):e98–e169. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000098.

- Cameron LJ, Somerville LM, Naismith CE, et al. A qualitative investigation into the patient-centered goal-setting practices of allied health clinicians working in rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(6):827–840. doi:10.1177/0269215517752488.

- Rose A, Rosewilliam S, Soundy A. Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):65–75. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.030.

- Kristensen HK, Tistad M, Koch L, et al. The importance of patient involvement in stroke rehabilitation. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157149. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157149.

- Walder K, Molineux M. Listening to the client voice - A constructivist grounded theory study of the experiences of client-centred practice after stroke. Aust Occup Ther J. 2020;67(2):100–109. doi:10.1111/1440-1630.12627.

- Turner-Stokes L, Rose H, Ashford S, et al. Patient engagement and satisfaction with goal planning impact on outcome from rehabilitation. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2015;22(5):210–216. doi:10.12968/ijtr.2015.22.5.210.

- Lyle J. Stimulated recall: a report on its use in naturalistic research. British Educational Res J. 2003;29(6):861–878. doi:10.1080/0141192032000137349.

- Paskins Z, McHugh G, Hassell AB. Getting under the skin of the primary care consultation using video stimulated recall: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):101. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-14-101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. London: Sage; 2022.

- Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, et al. Person-centered care - ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10(4):248–251. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008.

- Moore CL, Kaplan SL. A framework and resources for shared decision making: opportunities for improved physical therapy outcomes. Phys Ther. 2018;98(12):1022–1036. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzy095.

- Talevski J, Wong Shee A, Rasmussen B, et al. Teach-back: a systematic review of implementation and impacts. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231350. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231350.

- Nutbeam D, McGill B, Premkumar P. Improving health literacy in community populations: a review of progress. Health Promot Int. 2018;33(5):901–911. doi:10.1093/heapro/dax015.

- Muscat DM, Shepherd HL, Nutbeam D, et al. Health literacy and shared decision-making: exploring the relationship to enable meaningful patient engagement in healthcare. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(2):521–524. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05912-0.

- Levack WM, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, et al. Navigating patient-centered goal setting in inpatient stroke rehabilitation: how clinicians control the process to meet perceived professional responsibilities. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):206–213. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.011.

- Dekker J, de Groot V, Ter Steeg AM, et al. Setting meaningful goals in rehabilitation: rationale and practical tool. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(1):3–12. doi:10.1177/0269215519876299.

- Jesus TS, Papadimitriou C, Bright FA, et al. Person-centered rehabilitation model: framing the concept and practice of person-centered adult physical rehabilitation based on a scoping review and thematic analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103(1):106–120. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2021.05.005.

- Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, et al. Validating a conceptual model for an inter-professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(4):554–564. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01515.x.

- Voogdt-Pruis HR, Ras T, van der Dussen L, et al. Improvement of shared decision making in integrated stroke care: a before and after evaluation using a questionnaire survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):936. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4761-2.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications; 1985.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Marcum JA. An integrated model of clinical reasoning: dual-process theory of cognition and metacognition. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(5):954–961. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2012.01900.x.