ABSTRACT

This study examines business students’ learning and assessment under remote teachings during the COVID-19 pandemic in a well-established Finnish university. A survey method is used to collect information on 336 business students including 42 accounting students. As indicated by students’ responses, a majority of the students succeeded in assessing and self-regulating their learning, but a considerable group of students failed in this task. Students gave a lot of positive feedback on supervised electronic exams, such as scheduling efficiency, improved ability to focus, and reduced stress level. Students also reported a low number of monitoring problems in these exams. Furthermore, the results provide evidence that some students see the risk that problems in monitoring coursework threaten the value of their university degrees. However, about half of the students did not want to increase monitoring. Accounting students’ opinions were mostly similar to those of the other business students. This study contributes to the literature by showing key factors that influence students’ learning in remote teaching under abnormal conditions. In addition, it demonstrates how the constructivist model of learning can be used to explain students’ learning and assessment in these circumstances.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the boundaries of learning and teaching, as it caused a sudden digital leap in remote teaching and distance learning. Everything happened quickly, and pushed students and teachers to the limits of their capacity (Sangster et al., Citation2020). There is a need to redefine accounting education, and take the social, environmental, and moral aspects of education into account in the post-COVID-19 world (Carnegie, Citation2021; Fogarty, Citation2020; Tharapos, Citation2021). For example, it is problematic that at research universities, the faculty are primarily evaluated based on their research outcomes and not by their online teaching materials (O’Connell, Citation2021). Accounting educators now have the opportunity to learn from this unexpected shock, and take all the good ideas into circulation to reformulate the best teaching practices for the 2020s. The new curriculums should maximise the universities’ ability to motivate and train new skilful accounting people, who would solve the global problems of the upcoming decades.

During the pandemic, many universities fully transitioned to distance learning mode and accounting educators had to find new ways to teach the substance of accounting and to train the generic skills (e.g. presentation skills) of the students. Moreover, instructors faced a monitoring challenge because they suddenly had to assure the learning of their students from a distance. Prior research shows that instructors’ coping methods differed a lot during the pandemic, which suggests that students saw various approaches to teaching (Bartolic et al., Citation2021). Interestingly, Macias et al. (Citation2021) document that the pandemic triggered the use of new communication platforms, and improved the quality of dialogue between instructors and students. Moreover, it is documented that studying remotely requires that both the teaching and assessment include enough social elements, authenticity, and student participation (Halabi, Citation2021; Mali & Lim, Citation2021; Zarzycka et al., Citation2021).

In remote teaching, formative assessments can be effective in increasing students’ motivation and preventing procrastination (Blondeel et al., Citation2021). However, it is important to have clear guidance on the technical elements of online assessment in order to prevent the demonstrated problems with their online execution (Cahapay, Citation2021). In addition, prior studies demonstrate that although cheating is a common problem in online exams, it can be prevented if the assessment is carefully planned (Ebaid, Citation2021; Guangul et al., Citation2020). Hence, post-pandemic accounting education is faced with opportunities and challenges, which can be best understood through research in different institutional environments.

The existing literature provides meagre evidence on business students’ learning and assessment during COVID-19 in an environment, in which the assessment is decided by the universities, and not regulated by the professional bodies. In addition, more evidence is needed on environments in which the infrastructure for supervised electronic exams is available. As such, the objective of the paper is to shed light on this gap. The motivating research problem in this paper is: How did learning and assessment succeed in remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Finnish business school? The study of the research problem will be linked to the constructivist model of learning (see section 2.4), which suggests that student-related factors, current learning context, and the assessment explain why some students learn better than others (Biggs, Citation2003; Lucas & Mladenovic, Citation2004; Miihkinen & Virtanen, Citation2018). The more specific research questions of the study are the following:

How did students experience the quality of their learning?

Did students succeed in assuring and self-regulating their learning?

Did students consider that teachers’ assessment methods were effective?

Did students think that electronic exams and course assignments facilitated their learning?

What kind of opinions did students have on the monitoring of their coursework?

This study answers the research question by examining business students’ responses via an online survey, which included both closed and open-ended questions. The survey was conducted at a business school of an old and well-established Finnish university in January and February 2022, during which the pandemic had been ongoing for almost two years. 336 business students, including 42 accounting students, answered the survey.

The suitability of the Finnish setting can be justified by the country’s education-friendly culture and good performance in global education rankings (Kupiainen et al., Citation2009; Ustun & Eryilmaz, Citation2018; Yoon & Järvinen, Citation2016). In Finland, studying at a university is possible for everyone at a low cost. The curriculums of the universities support the development of students’ critical thinking. For example, students write bachelor’s and master’s theses during their studies, which increases their capacity for conceptual thinking and analytical work.Footnote1 In addition, because Finnish universities decide their assessment practices independently, professional bodies and employers do not set any specific requirements that a certain amount of students’ coursework should be monitored.Footnote2

The results demonstrate several positive viewpoints on studying during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many students argued that they were able to assure and self-regulate their learning in remote mode. Students’ opinions demonstrate that the effectiveness of remote studying can be better than that of contact teaching in a classroom. One reason is that remote studying is much more effective timewise. Students also gave positive feedback on assignments, which facilitated the assurance of their own learning during the course. In addition, the monitored electronic exams received a lot of positive feedback due to their flexibility and stress-relieving effect. The student opinions suggest that the monitoring problems of the supervised electronic EXAM exams were low.

However, the student responses also document some negative aspects of studying during the COVID-19 pandemic. The most alarming finding is that students’ performance varied significantly among different groups during the examined time period. The responses demonstrate that there was a certain group of students, who were unable to assess and self-regulate their learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. One inference for this finding is that the grouping is caused by the differences in student factors of the constructivist learning model, such as previous knowledge, motivation, affect, and integration. Some students benefit, and some students suffer from remote teaching.

Finally, the results provide evidence that in the students’ opinion, there were no significant issues with the monitoring of their coursework during the COVID-19 pandemic. These problems were limited to the unmonitored electronic Moodle home exams, while the monitored electronic EXAM exams received a lot of positive feedback. Students question the ability of the Moodle exams to signal their learning. Interestingly, about half of the respondents argued that they are ready for their course work to be more rigorously monitored to ensure the valuation of their university degrees, but there was also a strong opposition against new monitoring practices. Accounting students’ responses were fairly similar with other business students’ responses. One probable reason for this is that all business students read the same basic courses in the beginning of their studies, and they are also a homogeneous group of students.

Contribution

This study contributes to the learning and assessment literature by providing empirical evidence on business students’ positive and negative viewpoints on learning and assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic with remote teaching, and reflecting the results against the constructivist model of learning (e.g. Biggs, Citation2003; Lucas & Mladenovic, Citation2004; Miihkinen & Virtanen, Citation2018). Firstly, it is one of the first studies examining business students’ experiences on learning and assessment during the pandemic. This way, it provides new information on the advantages and disadvantages of studying via remote teaching. Secondly, this study contributes to the assessment literature by exploring the monitoring of learning in an environment where teaching education and outcomes are globally recognised, but the professional bodies do not regulate the monitoring of the course work; as a consequence, the planning of the curricula is more dependent on the internal forces of the university. In this environment, it adds value to show students’ preference towards assignments in the spirit of the principles of formative assessments.

Thirdly, the study adds to the meagre existing evidence on the usability of different forms of electronic exams in the 2020s by showing the various aspects that relate to this type of testing of students’ performance. Finally, the study adds to the accounting education literature by empirically documenting the grouping of students’ performance in the pandemic; that is, it demonstrates that roughly two-thirds of university students performed well during the pandemic, while one-third performed poorly.

The study findings are relevant for the practitioners who develop their future teachings, and make decisions on the best ways to learn remotely. This helps them to find and preserve the best practices of distance learning. The examined information provides much needed support for the educators’ efforts to encounter the renewal pressures of university teaching most efficiently.

The study proceeds by discussing the theory and empirical literature on learning and assessment in section two, followed by data and methods in section three. Section four reports the empirical results, and the discussion of the results is provided in section five. Section six summarises and concludes the paper.

Theory and empirical literature

Theoretical reasoning for learning and assessment under COVID-19

The constructivist learning theory suggests that students learn better if learning objectives are aligned with teaching and assessment methods (Biggs, Citation1996).Footnote3 The constructivist model of learning gives an important role for the current learning context because it affects students’ perception of task requirements, which then influences students’ approaches to learning (Biggs, Citation2003; Lucas & Mladenovic, Citation2014). In addition, learning outcomes depend on assessment methods and tools, which influence students’ perception of task requirements, interact with student-related factors, and can aid students in their self-assessment and self-regulating their learning (Miihkinen & Virtanen, Citation2018). However, the existing literature documents difficulties in students’ self-assessment and task selection (Kostons et al., Citation2012). The self-regulation theory suggests that students’ capacity to self-regulate their learning boosts constructive processing and works better than external regulation (Vermunt, Citation1998). Thus, effective self-regulated learning requires that the student can precisely assess her/his performance (e.g. Kostons et al., Citation2012; Puustinen & Pulkkinen, Citation2001; Vermunt, Citation1998).

Empirical evidence on learning and assessment during COVID-19

There is some evidence regarding the effects of the pandemic on learning and assessment. The compiled article by Sangster et al. (Citation2020) summarises how the accounting educators in 45 countries around the world responded to the outbreak of COVID-19.Footnote4 The article provides evidence on the advantages (such as new forms of teaching) and disadvantages (such as the faculty and students’ worsened health and well-being) of the pandemic, and predicts that accounting education will not return to how it was before the outbreak. Furthermore, Bartolic et al. (Citation2021) document that instructors’ viewpoints on the effects of the pandemic on learning and teaching, as well as their coping methods, vary considerably across courses and countries.

Communication and collaboration between the instructors and the students were major challenges in the pandemic, and new communication platforms had to be used. Interestingly, Macias et al. (Citation2021) document that although the distance between the students and the instructors grew, the quality of dialogue increased. This finding suggests that the pandemic expanded the means for interaction, along with the new platforms to communicate and build trust in the relationship between the participants. On the contrary, Mali and Lim (Citation2021)Footnote5 provide evidence that students preferred face-to-face learning over blended learning because it is superior in terms of incorporating the social elements into teaching. They suggest that educators should remember to include social elements in teaching when they move from traditional teaching to online or blended teaching. In addition, Zarzycka et al. (Citation2021)Footnote6 show that active participation in distance classes and the use of social media increased the quality of communication and collaboration during the pandemic. However, Altindag et al. (Citation2021) results suggest that unequal access to technology is a source of learning disparity during the pandemic.

Assessment was another challenge in the pandemic because it may be more difficult for students to assess their learning in remote learning. Blondeel et al. (Citation2021)Footnote7 provide evidence that by adding the home exams to the course programme, the voluntary usage of supplemental learning materials via the online platform increased. The finding suggests that a formative assessment via intermediate home exams motivates students to use additional online formative assessments on the platform, and can be used to prevent students’ procrastination. However, Cahapay (Citation2021) documents several problems in the online assessment, and suggests that student guidance via a test manual is important.Footnote8 Moreover, Halabi (Citation2021)Footnote9 demonstrates that alternative assessment methods, which substitute the final examination, can be effective. His results suggest that an interview that is reported as a podcast provides an efficient learning experience where theory, practice, and authenticity are taken into consideration. According to Altindag et al. (Citation2021)Footnote10, COVID-19-triggered changes in the student’s assessment led to an increase in the student’s grades. However, the instructor-specific factors, such as leniency in grading or actions towards preventing violations of academic integrity, may interfere with the correct inferences on the benefits of online learning.

Academic dishonesty amid the COVID-19 pandemic has been examined in few studies. Guangul et al. (Citation2020) suggest that the assessment type plays a key role in preventing cheating. For instance, identifying the student in the online presentation and preparing different questions for each student were good methods to support academic integrity during COVID-19.Footnote11 Ebaid (Citation2021) provides evidence that cheating was a prevalent phenomenon during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that the most common cheating behaviours were as follows: text messages via cell phones to send or receive exam answers to/from another student, using an open book during an online exam, consulting with other students during an online exam, delaying one’s entry to the online exam for some time to get questions from another student, and using personal class notes during an online exam.Footnote12

The monitoring of students’ course work in the post-COVID-19 era

The monitoring of students’ course work is important because a higher degree of monitoring (or invigilation) is expected to increase the value of the university degrees in the eyes of the professional bodies and employers, as they will be able to better trust that the finished university degrees reflect the skills and knowledge of the students. Lowering the monitoring of students’ course work can be problematic if it increases the probability that students do not achieve the skills and competency that they are expected to have in their work-life. The credibility of the assessment system lowers the information asymmetry related to the education quality, and the ‘stakeholders’ of the university can better trust the skills of the new graduates. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, contact teaching was the prevailing teaching method. Thus, monitoring the students’ course work was easier to execute than in the middle of the epidemic. The electronic exams became a popular way to test students’ learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, and thus challenged the existing monitoring practices.

In some countries, professional bodies set assessment requirements or hurdles for the assessment. For example, in Australia, they expect that the invigilated work is at least 50% of the overall assessed course work, focusing on the competency area of the student.Footnote13 In Finland, the invigilation of course grades is not regulated by professional bodies, and universities have a lot of responsibility in organising the assessment of the course work. In Finland, the universities offer a chance to accomplish the required courses for the official auditor degrees as a part of their studies. Those who apply for the confirmation of their official auditor degrees have to show the diploma that confirms that they have studied the required courses. Thus, it is enough that these courses are studied at the university, and that the university has aligned the content and scope of the courses with the country-wide auditor degree requirements.

Predictions based on the literature

The results will be interpreted against the constructivist model of learning, which suggests that student-related factors and the current learning context determine students’ learning process and learning outcomes (e.g. Biggs, Citation2003; Lucas & Mladenovic, Citation2004). It is expected that students encounter a lot of uncertainty because the pandemic shapes the boundaries of the normal learning context. In this environment, differences in student factors and assessment methods (e.g. formative vs. summative assessment) help students to perceive task requirements, self-assess their studying, and choose a proper approach to learning, which ultimately leads to better learning outcomes (Miihkinen & Virtanen, Citation2018). It is ex-ante difficult to predict the extent of the monitoring problems within the target sample.

Data and methods

The survey data was collected from the students of the business school in a Finnish university. The business school has five units, and it has undergraduate, master, Ph.D., and MBA programmes. It is also possible to study some of its courses in an Open University.

The Department of Accounting and Finance has several subjects that can be studied as a major. Combined, Accounting and Finance are the largest subjects at the entire business school. For example, they overcome many other units in terms of the number of major students, the number of completed master’s theses, and the number of studied academic credits. During the pandemic, electronic exams became a standard way of testing students’ learning.Footnote14 Two forms of electronic exams exist in the studied university, which are unmonitored Moodle exams and supervised EXAM exams.Footnote15

COVID-19 forced the targeted university to move to remote teaching in March 2020, and the following academic year (starting in the fall semester of 2021) was largely organised in the remote teaching mode. Hence, the freshmen who started their studies in that year were mostly forced to study remotely for the whole year. The pandemic showed signals of disappearing in the summer of 2021, and the university was able to partly return to contact teaching, but had to close again at the end of the year. Hence, after almost two years of studying during the pandemic, and after seeing the different phases of the epidemic, it is expected that students have a good capacity to answer the survey.

The online survey was sent to the students with the help of the study office in January 2022.Footnote16 At this time, the third semester of the academic year had just started, and students had begun a new year in remote teaching. Due to the Omicron variant spreading heavily, the university had to therefore cancel contact teaching again. The survey focused on different aspects of studying during the pandemic. In this study, the focus is on questions that explore students’ opinions on their learning and assessment during the pandemic.Footnote17,Footnote18

Empirical evidence on learning and assessment during the Covid-19 pandemic

Description of the data

Altogether, 236 business school students answered the survey anonymously.Footnote19 This number included the responses of 42 accounting students. Posting lists were used to deliver the survey, which made it impossible to provide the exact response rate. The target sample is relatively equally distributed by gender; 56.8% of the respondents are female and 43.2% are male. The majority of them (60.6%) belong to the age group of 18-25, with the age group of 26–35 being the second most common (25.0%) group. The age groups 36–45 and 46–55 represent about 7% and 6% percent of the responses, respectively. Full-time students dominate the sample (56.4%), whereas a quarter of the respondents work a maximum of two days a week in addition to studying. Moreover, 18.6% of the respondents are working full-time and studying with the remaining time. There is a good distribution of different students in the sample; 47.2% of them studying for a bachelor’s degree, 41.7% master’s degree, 2.1% percent a Ph.D., and 8.9% studying at the Open University.

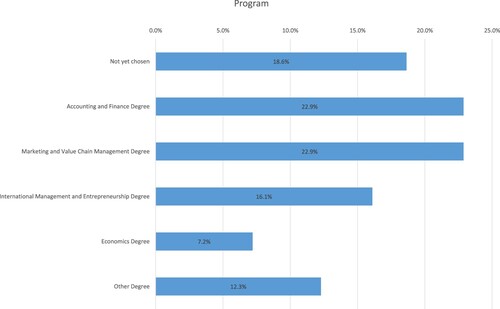

In addition, there is a broad distribution of classes represented in the sample: 24.8% are first-year students, 26.5% second-year students, 13.2% third-year students, 15.0% fourth-year students, 12.0% fifth-year students, 3.4% sixth-year students, and 5.1% have been studying for more than six years. The student respondents represent a wide selection of study programmes, as it can be shown in . Accounting and Finance Degree students, together with the Marketing and Value Chain Management Degree students, represent 22.9% of the target sample; 18.6% has not yet chosen the study programme, 16.1% have chosen an International Management and Entrepreneurship Degree, 7.2% Economics Degree and 12.3% Other Degree. With respect to the specialisation subjects studied by the respondents, the untabulated results confirm that Accounting is the most common (18.2%), followed by Management and Organisation (16.8%), Marketing (12.1%), and Finance (9.9%).

Empirical results

The next sections will discuss how the respondents have seen their performance in learning and assessments in a COVID-19 world. It will describe the statistics of the responses, accompanied with the selection of student quotes as provided in the open questions of the survey.Footnote20

The quality of learning under remote teaching

One way to measure the quality of learning is to use course grades to gauge what has been learned. Although this measure is common in the pedagogical literature, it has been criticised because it measures only certain dimensions of learning. However, assuming that the course grades somehow signal the quality of learning in the sample, the results show that about a fifth of the students (18.4%) have benefited from studying during the pandemic since their course grades have improved, whereas 81.6% have not seen any improvement (results untabulated, available on request). However, the improvements in course grades should be interpreted with caution because COVID-19 also made it more challenging to monitor cheating.

Students’ qualitative comments demonstrate how differently they have dealt with the new way of learning under the abnormal conditions:

I have had problems with [the] power to study and keep up my motivation. My grades have gotten lower when I have not had [the] power to do anything else than the necessary [tasks].

My study motivation has increased.

It has been easier to recap because of the video material. It has also been easier to prepare for the exams when there has been the change to fit [the] exam schedule to [my] own rhythm.

I guess a more important reason for better grades is that my study skills have improved.

I do not have any interest in studying. It has become unsavoury and burdensome, although I used to like it sometimes. The constant staring at the computer screen also downgrades the grades.

Remote and home work has hampered my performance. Previously, I was able to stay long days at school with my friends. It was easier to study.

Studying has become much easier and now studying and [my] own effort matters. Previously, it was only important if you have time to go to the lecture and see the correct answers to the assignments, etc. There are more hours in the day, and it is easier to concentrate in privacy at home.

Students’ ability to assure and self-regulate their learning

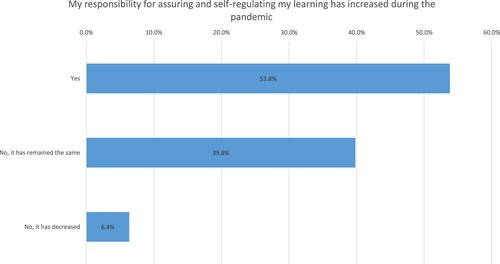

Students’ survey responses suggest that the majority of them have been able to assure and regulate their learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. illustrates that 53.8% of the respondents took more responsibility in this area; for 39.8%, there was not any change, and 6.4% said that their responsibility decreased.

Figure 2. This Figure shows students’ answers on the question regarding their responsibility on assuring and self-regulating their learning during the pandemic. The number of responses is 236.

The qualitative comments document several factors, which are important in effective assurance and regulation of learning in the remote teaching mode. Several keywords can be linked to these responses, such as responsibility, pressure, internal motivation, scheduling, and optimal study approach:

I have learned to better self-regulate my studying, which has improved my grades.

You have to schedule your work better to be able to make a difference between school and free time.

I have taken more responsibility for searching information and monitoring my studying. This has been an excellent exercise for the work-life.

If the lectures are recorded, it is easier to skip the lecture and read the same information from the course books. Hence, I have to take the responsibility that I learn the learning objectives of the course. For me, this is a better approach than sitting in lectures. I learn by reading, not by listening.

I do not require that much from myself, and I am happy with the okay level performance. I do not have the power to dig deeply into topics and to do anything extra to aid my learning.

Maintaining self-discipline when studying online has been hard since it is so easy to start multitasking. Also, keeping focus in online classes requires much more because there are so many potential distractions when studying at home. Not being able to go to school/library has also made it harder to separate school/leisure time.

Remote studying and remote working mean that I spend all the time at home - alone. Since the future seems so hopeless, I have little motivation to do anything unnecessary. I can't meet my thesis counsellor and I feel I am all alone in this situation.

As a first-year student, I feel that I have not get information anywhere. All information has to be searched for alone. As a first-year student, it is difficult to consider how the situation could be because I do not have anything where to compare.

Students’ qualitative comments on the reasons, which have influenced their success in the assurance of their learning, document that the clarity of instructions and peer support are important drivers of the assessment of students’ own learning. In addition, the continuous testing of learning is mentioned. The following qualitative comments are as follows:

I feel [it is] difficult to understand some guidelines of the assignment as the requirements are not explicit and specific enough.

Sometimes it is difficult to know what I am expected to do at the course. You cannot ask the teachers as easily as you could in contact teaching.

Benchmarking is quite difficult, you don't know the other people and don't study together.

Midterm assignments, midterm exams, and group work sessions tell me if I have learned the studying issues of the week.

Fortunately, university infrastructure is excellent, and they facilitate its accessibility by remote learning instruments.

The unstable Internet in the Student Village and the difficult access to some printed reference materials in the library.

Because some teachers have lots of technical problems, and it's not easy to focus during online lecturing.

I have done more assignments and got feedback on them.

I have learned more [learning] during the pandemic than before it. Hence, it has been easier to assess [my] own learning.

It makes it possible to learn, although you would have a family. I have been forced to be a lot [more] absent because my child has been sick. Remote connection makes it possible to participate and the recorded lectures are not dependent on time, so you can do shifts at the same time.

I think my self-esteem as a student has decreased a lot during the pandemic. It's hard to believe in myself since I haven't graduated yet, although there have been so many years since I started studying.

My ability to concentrate has declined.

Moreover, the survey responses suggest that for some students, remote teaching can be helpful in self-regulating their learning, especially in courses where the outcome is a thesis or another long written report. The results (untabulated) demonstrate that 54.1% of the business students saw the benefit, 18.9% did not see it, and 27.0% did not have any thesis or long written reports during the pandemic. Among the accounting students, these numbers are 48.8%, 31.7%, and 19.5%, respectively. Hence, the majority of the students answered that remote teaching supported their thesis work.

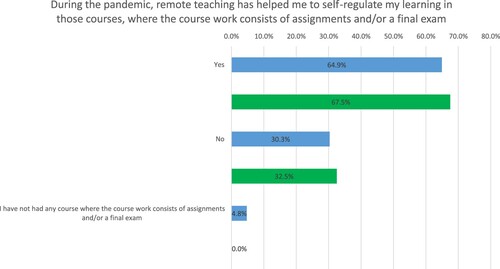

Furthermore, depicts that 64.9% of the students consider that remote teaching has helped them in self-regulating their learning in those courses where the course work consists of assignments and/or a final exam. Among the accounting students, this number is 67.5%. This finding implies that remote teaching works well for almost two thirds of the students in courses with traditional assessment methods like exams and assignments. Collectively, the results document that during the pandemic, remote teaching has helped many students in self-regulating their learning; but notwithstanding, approximately a third of the students have not benefited from it.

Figure 3. This Figure describes students’ responses on the usefulness of remote teaching in self-regulating their learning in the courses where the course work consists of assignments and/or a final exam. The blue bar in the chart represents a total of 231 responses from business students, whereas the green bar represents a total of 40 responses from accounting students.

Effectiveness of the teachers’ assessment methods under the pandemic

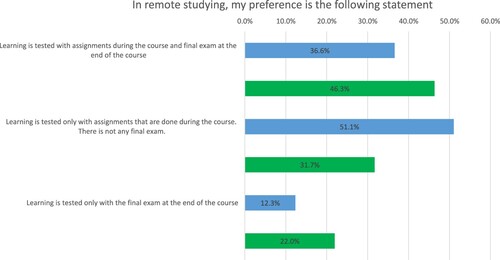

In a formative assessment, students’ learning are already measured during the course (for example, via assignments), whereas in a summative assessment, students’ learning are tested by a final exam at the end of the course. depicts students’ viewpoints on the preferred way of testing their learning in remote studying. The responses demonstrate that although 36.6% of the students preferred the combination of a final exam and assignments, the majority (51.1%) considered it better if their learning was tested only with assignments that are completed during the course without any final exam. This left 12.3% of the respondents considering it best if their learning was tested only with the final exam at the end of the course. Interestingly, among the accounting students, the percentages reversed: 46.3% of the accounting students considered that their preferred method of testing their learning was a combination of the assignments and final exam, 31.7% preferred only the assignments, and 22.0% would only use the final exam. The finding suggests that in remote studying, there is pressure to use alternative assessment methods in lieu of traditional final exams, although accounting students seem to appreciate a final exam a bit more than other business students.

Figure 4. This Figure describes students’ responses with regard to their preferences for testing their learning. The blue bar in the chart represents a total of 235 responses from business students, whereas the green bar represents a total of 41 responses from accounting students.

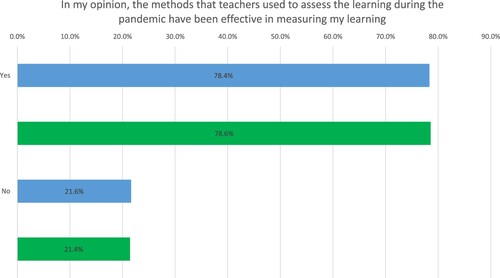

portrays students’ opinions on the teachers’ assessment methods and their performance in assessing students’ learning. It shows that 78.4% (78.6%) of the business students (accounting students) considered that the methods that teachers used to assess their learning during the pandemic were effective in measuring their learning, whereas 21.6% (21.4%) did not see the effectiveness. Interestingly, the untabulated results suggest that 70.6% (81.0%) of the business students (accounting students) answered that during the pandemic, teachers had less success in the assessment of learning compared to the pre-pandemic assessment of students’ learning. On the other hand, 21.5% (16.7%) did not notice any difference, and 7.9% (2.4%) replied that the teachers succeeded better than before the pandemic. The results suggest many students were more satisfied with the methods than with teachers’ performance in assuring their learning. However, this finding should be inferred with caution because students’ responses may reflect their dissatisfaction with other areas of instruction than the assessment. Another interpretation of this conflicting finding is that the methods were effective as such, but teachers provided too little feedback and guidance for the students, and some students therefore felt that teachers did not bring incremental value to students’ self-assessment.

Figure 5. This Figure describes students’ responses with regard to teachers’ assessment methods during the pandemic. The blue bar in the chart represents a total of 231 responses from business students, whereas the green bar represents a total of 42 responses from accounting students.

Furthermore, the qualitative results provide evidence that course assignments were effective in improving students’ learning, but teachers’ different teaching methods influenced students’ learning outcomes. Interestingly, one student answered that the connection with teachers improved during remote teaching, whereas the others argued that the connection became faceless:

I learn better by doing assignments and writing essays. The type of tasks have been common during the pandemic, and I feel that they measure learning better than traditional exams.

My experience is that teachers’ assessment/teaching depends more on [the] teacher than the mode of teaching (remote or contact).

This depends on the teacher. Some teachers have realised that it is effective to record the lectures, and assign smaller deadlines during the course. Some teachers refuse to record the lectures, which do not help us to study.

Before the pandemic, I have never achieved [a] similar connection with the teachers than now.

Teachers only see a black screen during the lectures. It is very difficult to assess [a] student’s activity. In remote mode, teachers often see only the name of the students and then link that to the faceless electronic exam or essay grade.

The whole study time in my current degree has been pandemic time.

Because from the beginning of this pandemic, I am admitted here, and I cannot compare before and after!

The role of electronic exams and course assignments in assessment

On-site exams at the campus were forbidden for a long time during the pandemic. In this situation, electronic exams had to be used as a replacement. Two main approaches prevailed. First, having an unmonitored home exam in a learning platform called ‘Moodle’. Second, having an electronic exam in the electronic exam system called ‘EXAM’. The main difference between the two forms of electronic exams is that EXAM exams are supervised with access control and video surveillance and conducted in a specific place at a specific prebooked time, whereas Moodle exams are done at home without supervision. The university under study had already taken the EXAM platform into use prior to the pandemic, which means that it did not have to suddenly create the infrastructure when remote teaching started.

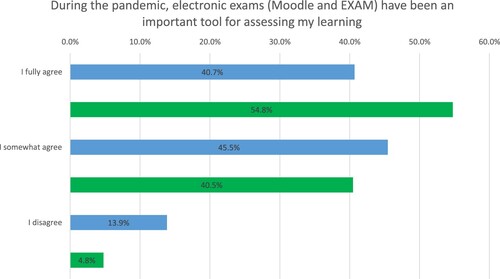

portrays students’ opinions on the importance of electronic exams in the assessment of their learning; showing that 40.7% (54.8%) of the students (accounting students) considered electronic exams important, 45.5% (40.5%) somewhat agreed on the importance, and 13.9% (4.8%) disagreed on their importance. These results imply that many students deemed that electronic exams were useful in the assessment of their learning, and this opinion was more common among accounting students.

Figure 6. This Figure describes students’ opinions on the importance of electronic exams (unmonitored Moodle exams or supervised EXAM exams) for the assessment of their learning. The blue bar in the chart represents a total of 231 responses from business students, whereas the green bar represents a total of 42 responses from accounting students.

An even stronger effect has been documented in the responses to the question on the importance of course assignments (results untabulated). Accordingly, 64.3% (61.9%) of the business students (accounting students) fully agree that course assignments have been an important tool to assess their learning, whereas only 3.0% (4.8%) disagree. These results support the idea of a formative assessment, which suggests that course performance is assessed already during the course.

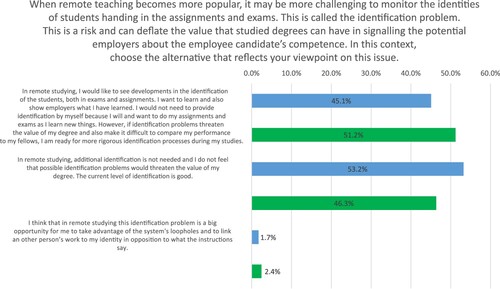

Monitoring of the students’ coursework

Remote teaching increased the challenges of monitoring students’ coursework. This is one disadvantage that has been linked to electronic exams. However, they also have many benefits, such as flexibility, which increases the effectiveness of learning and teaching. The survey results documented that 31.1% (45.0%) of the students (accounting students) would like to see more rigorous actions in the monitoring of their coursework, whereas 68.9% (55.0%) do not see any need for that. Interestingly, almost half of the accounting students would like to see more monitoring in regards to their assignments and exams. Students’ qualitative responses are well aligned with the reported numbers:

It is irritating when you know that other students have cheated without any consequences. Then [my] own honest work feels less valuable.

In my opinion, this is not that big [of] a problem that it would be necessary.

For me, it does not matter who is doing the assignments during the course because usually, the exam shows who has learned and who has not. But sometimes it feels unfair that I do the exams by myself, and I am not using any aids if they are not allowed. And I really try to understand the taught issues, and then you end up hearing that some students have gathered to do the exam together. And this way, they have benefited in the exam and the whole course.

I answered no because at the moment, a big amount of the Moodle exams are done assuming that the students use course materials and Google. The exams require more applied thinking, and there is very little time.

You cannot increase the monitoring of the students at the same time as you require that university students are adults, self-regulating their work and taking responsibility. It does not show trust.

Figure 7. This Figure describes students’ opinions on the need for more effective identification strategies to better monitor students’ course work in remote teaching. The blue bar in the chart represents a total of 233 responses from business students, whereas the green bar represents a total of 41 responses from accounting students.

Moreover, students’ qualitative comments demonstrate that some respondents were concerned about the risk of a potential value degradation of their degrees due to inefficient monitoring, whereas some students highlighted that identification problems are not significant. Interestingly, one student argued that signalling a potential identification problem could cause distrust among employers:

There are all kinds of assignments, which are done independently also in the contact teaching. I do not believe that the problem is any bigger in remote teaching. I also believe that most of the university students are conscientious and willing to learn and do not try to cheat to get the degree.

Because in my daytime job, I work as an employer and have recruited dozens of people only last year; I do not recognize this problem as an employer.

We could have some identity checks in the electronic EXAM exam rooms.

The only risk factor is that the university itself starts to signal a problem, which is not a problem. It is very dangerous if the university starts creating distrust and the employers take ideas of that. Who would really think that universities have a cheating wave ongoing, and these cheating students would start applying for a job, which needs specific skills that they do not have.

If identifying the students is a problem, could we take strong identification in use in the future? I think that [my] own bank passwords will not be shared so easily.

EXAM exam is a fabulous invention. Then you can choose your own timetable and go according to it.

It's great to have the ability to schedule exams depending on the time needed to study for them. If it's a set date, I might have 3 exams in 2 days. Now I can spread them out and not have to study for each test at the same time.

There is nothing in the on-site exam, which would not exist in [the] EXAM exam, whereas the on-site exam, which is taken in the class, has many disadvantages that do not exist in EXAM exams. It is much more difficult to concentrate on the on-site exam. The only disadvantage of EXAM exams is that the testing places can be fully booked. On the other hand, the on-site exam is much less flexible timewise.

I am easily procrastinating the EXAM exam until the last evening, although I would have already learned the studied tasks. On-site class exams could work better if I could manage to do the exams during the correct study period. This would prevent taking the fall courses in the spring.

At least in the economics courses, learning would be easier to measure if you would have the opportunity to use a pen and piece of paper to draw graphs and formulas. On the other hand, in those courses where learning can be measured through an essay, EXAM would be a better alternative.

I like that all the students have the same on-site exam. EXAM draws the exam questions, and some students get an easier or more difficult exam.

More effective way for me because I get less stressed and nervous in EXAM room exams, and can thereby better focus on my performance.

There is a stressful situation on traditional final exams but not electronic. I mean, you can take your exam without being distracted how others, with what speed, are doing their stuff!

The possibility to take into account [my] own schedules and other exams. I am also less nervous in EXAM exams.

Discussion of the results

The COVID-19 pandemic was an exogenous shock to the current learning context. This study documents how differently the pandemic treated the students. Many students benefited from distance learning, whereas for some students, ‘the new normal’ caused severe difficulties in assessing and self-regulating their learning. This finding is in line with the constructivist model of learning, which suggests that student factors and the current learning context influence a student’s perception of task requirements (e.g. Biggs, Citation2003; Lucas & Mladenovic, Citation2014).

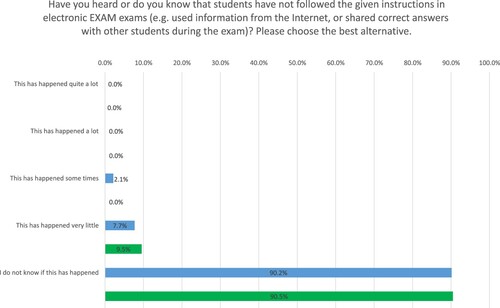

Figure 8. This Figure describes students’ answers to monitoring problems in electronic EXAM exams. The blue bar in the chart represents a total of 234 responses from business students, whereas the green bar represents a total of 42 responses from accounting students.

Interestingly, when some students considered certain issues to be advantageous for learning, other students had exactly the opposite view on the same issue. For example, there was a high number of students, for whom distance learning improved their time management and made learning more flexible. It also improved their ability to have a job parallel with their studies. These students were able to self-regulate and assess their learning, and use the course material effectively to maximise their learning opportunities.

On the contrary, there was a moderate number of students who could not self-regulate and assess their own learning remotely. The documented negative aspects of remote studying are somewhat in line with the results of Mali and Lim (Citation2021), and can be also explained by the constructivist model of learning because students come from different backgrounds and these differences also influence their learning outcomes. For example, a student who has been dependent on external requirements before the pandemic and lacked internal motivation may face many difficulties in regulating her/his learning, which then influences harmfully on her/his perception of task requirements and approach to learning.

Another explanatory factor for the differences in students’ responses was the assessment, which varied because teachers had different assessment practices. If the student factors do not give adequate preconditions for learning, then the assessment is a key factor in the current learning context, which can facilitate learning and compensate for the deficiencies in the student factors. The idea of assessment helping students’ self-assessment and learning is in line with Miihkinen and Virtanen (Citation2018).

In addition, the results suggest that assignments can be more helpful than exams in the assessment of students’ learning. The results provide evidence that having regular assignments during the course helped students to assess and self-regulate their learning process, which led to better learning. This approach is in line with the idea of a formative assessment, in which a student’s performance is monitored already during the course. It may be that those students who face more problems in distance learning would also benefit more from formative assessments. Regular assignments would help them to self-regulate and assess their learning, thereby preventing procrastination and improving their learning in line with the constructivist model of learning. The documented positive effect of formative assessments on their performance is in line with the theory of Miihkinen and Virtanen (Citation2018, p. 129). In addition, it supports the empirical findings of Blondeel et al. (Citation2021), who suggest that increased levels of formative assessments can prevent students’ procrastination.

This study also brings new light on the monitoring challenges of remote teaching. About half of the students wanted more monitoring of the assignments and exams, whereas the other half resisted the idea. One conclusion of this finding is that the respondents do not share a unanimous view that more monitoring is needed to assure the identity of the students. For some students, it seems to be important if it helps to safeguard the value of the degree. Most likely, this is partially related to the institutional setting. In Finland, the monitoring is decided at a university level. There are not any external pressures that would require a certain amount of coursework to be invigilated. This culture may reduce the need and willingness to incorporate additional monitoring burdens in the assessment.

Furthermore, this study provided evidence on the monitoring of electronic exams. One key finding is that although cheating happens in electronic exams, it usually occurs in unmonitored home exams. The documented cheating is in line with the thoughts of Guangul et al. (Citation2020) and Ebaid (Citation2021). However, several qualitative comments also show that many students prioritise learning over cheating at the university. Especially, the supervised electronic EXAM exams are documented to be effective in preventing cheating, which is an addition to the existing literature and shows that rigour and flexibility can be combined in the assessment of students’ learning. Only a few respondents documented monitoring problems in this type of exam. Moreover, the suggested scheduling efficiency makes monitored electronic exams a powerful resource in remote teaching, and these exams represent a new way of testing accounting students’ learning in their future assessment.

The results also raise a question on how much time the accounting faculty, who is also active in research, should put into teaching. Some students seem to think that educators should ‘bend over backwards’ to make them learn. Learning cannot be driven by only external factors, as students need to have some internal drive to be active as well. Hence, faculty members who also do research should find a good balance between their teaching and research time. Enough ‘stick and carrot’ incentives accompanied by supporting guidance should be provided to ensure students’ learning outcomes. Students are responsible to do the rest of the work.

Summary and conclusions

This study examined how learning and assessment succeeded in remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Finnish business school. The specific research questions addressed different viewpoints around the motivating research problem. The survey method was used to collect responses from the business students at the beginning of the spring semester of 2022 in January and February.

The results documented several positive aspects of remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many students were able to assure and self-regulate their learning in distance learning. The ease of scheduling and course assignments, following the spirit of formative assessments, were contributing factors for the positive experiences. Moreover, the supervised electronic exams received a lot of positive feedback because they improved students’ scheduling and learning, improved their ability to focus, and caused them less stress. In addition, the monitoring problems were low in this type of exam.

The findings also demonstrated the negative aspects of studying in remote teaching mode during the COVID-19 pandemic. There was considerable grouping in students’ answers, which suggests that students’ capabilities to cope with the changing forms of studying differed. Although some students benefited from the new form of learning remotely, a notable group of students suffered from it. This is a big contrast, which should be taken into future consideration when making decisions on the new forms of teaching. Furthermore, the results showed that about half of the respondents were ready for more rigorous monitoring of their coursework if it would better prevent the value degradation of their university degrees. However, there was also strong opposition to this kind of renewal. Accounting students’ responses were mostly similar to those of other business students.

This study contributes to the learning and assessment literature by documenting business students’ positive and negative viewpoints on their learning and assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic with remote teaching, and reflecting the results against the constructivist model of learning (e.g. Biggs, Citation2003; Lucas & Mladenovic, Citation2004). The study also contributes to the literature by providing evidence on the benefits of supervised electronic exams. Lastly, one contribution is the documented grouping effect, which shows that approximately two-thirds of the university students perform well and one-third perform badly in the remote teaching mode. The results are useful for accounting educators who try to answer to the renewal pressures of university teaching by developing the best practices for distance learning in the 2020s.

This study also has some limitations. The results may not be generalised for other countries, which have different university systems. Another limitation is that the students may have been self-selected to answer the survey if their characteristics explain how actively they answered the survey. Future research could benefit from additional evidence on the factors that determine why some students perform well in distance learning, and why others suffer from poor performance and bad learning outcomes. This would require well-designed research methods to reliably get into the student factors of the constructivist learning model to better understand their role as explanatory factors for students’ ability to cope with the demands and opportunities of remote teaching. Furthermore, the lecturers at the same institution could be examined to determine if they see the pros and cons of distance learning during COVID-19 differently.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2023.2229996)

Notes

1 In Finland, thesis work is a part of students’ university education, as it trains students to do scientific research. At the bachelor’s level, the students write a bachelor’s thesis, which consists of 20–30 pages. At the master’s level, students dig deeper into scientific research and write approximately 70–90 pages for their master’s thesis on the chosen research topic.

2 In this study, the terms monitoring and invigilation are used interchangeably to describe the level of monitoring that is addressed to students’ coursework, such as assignments and exams. The purpose of monitoring/invigilation is to ensure that the quality of education remains at a high level, and that employers can rely on the fact that graduates possess the skills and competence expected based on their university studies. These parallel concepts relate to the confirmation of students' identity relative to their course work. In certain jurisdictions (e.g. Australia), the professional bodies and employers give explicit pressures that a certain amount of the course work in degree studies should be based on work that is done while being monitored and linked directly to the student’s identity. ‘Monitoring’ is typically used in American English and ‘invigilation’ in British English.

3 The term ‘constructive alignment’ is often used to describe this.

4 In less than three years, this study has accumulated over 44,500 views and 115 CrossRef citations.

5 The research sample consisted of second-year accounting undergraduate students in the UK.

6 They used an online survey to examine Polish business and finance students.

7 The target sample covers first-year undergraduate business economics students taking an accounting course at a large research-oriented Belgium university.

8 The research sample consisted of Filipino college students. The documented problems in their online assessment are: incompatible browsers, anxiety over tracking tools, unstable internet connection, electric power interruptions, distraction in the environment, and unknown accessibility issues.

9 Halabi (Citation2021) tests this method in his MBA accounting course.

10 The target sample covers student records of 78,048 observations from a U.S. public research university.

11 They used a survey to collect information from instructors of the Middle East College.

12 This survey explored the seventh and eight level accounting students in the accounting departments of three Saudi Arabian universities. The students were more experienced and already passed a large number of assessments.

13 This means that 50 % of the overall assessed course work is monitored so effectively that the identity of the student can be linked to that course work.

14 The electronic EXAM exams are done by the students based on their own reservation. Usually, there is about 1–3 weeks’ time to take the exam, and this is decided by the instructor. EXAM is used by a consortium of Finnish Universities, and students also can take the exam in other universities than their home university. More information on EXAM can be found from the following website address: https://e-exam.fi/in-english/

15 In Finland it is not allowed to control students’ remote exams via the web camera. It was previously allowed, but after a student made a complaint on the policy, it was discontinued due to the violation of students’ privacy.

16 The need for the approval of studying human participants was inquired before the study. The university did not require the formal approval of studying students anonymously at the business school level. In addition, as shown in the Appendix, the first question asks students for consent to handle and report their replies confidentially and use them for scientific research and/or the development of teaching.

17 These survey questions, combined with the relevant background information that was asked, are provided as an online Appendix. The online appendix is available from the following address: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Jfr5XlpqgW16IU4C6QmTX22vTbPHtb-o?usp=sharing

18 The survey was written and sent both in Finnish and English. 210 students answered the Finnish survey, and 27 for the English survey. The quotes of the Finnish survey are translated to English. The language editor also edited the students’ responses in order to maintain the readability and authenticity of the answers. As such, the text inside the square brackets provides clarification for the reader, while supporting the content of the quotes. Moreover, the survey questions from the Appendix were edited by the language editor to improve their readability.

19 Originally, there were 237 responses, but one student did not give consent to use the data. Hence, her/his answers were not taken into consideration. Moreover, students were allowed to leave a question unanswered. For these reasons, the number of responses varies between 236-228.

20 Those responses, which were given in Finnish, are translated into English.

References

- Altindag, D., Filiz, E., & Tekin, E. (2021). Is online education working? NBER Working Paper No. w29113. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3897550 Accessed 31.1.2022.

- Bartolic, S. K., Boud, D., Agapito, J., Verpoorten, D., & Williams, S. (2021). A multi-institutional assessment of changes in higher education teaching and learning in the face of COVID-19. Educational Review, 74(3), 517–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1955830

- Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871

- Biggs, J. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university (2nd ed.). Society for Research into Higher Education, Open University Press.

- Blondeel, E., Everaert, P., & Opdecam, E. (2021). Stimulating higher education student to use online formative assessments: The case of two mid-term take-home tests. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(2), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1908516

- Cahapay, M. (2021). Problems encountered by college student in online assessment amid COVID-19 crisis: A case study. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology for Education, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.21742/IJCSITE.2021.6.1.01

- Carnegie, G. D. (2021). Accounting 101: Redefining accounting for tomorrow. Accounting Education, 31(6), 615–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2021.2014915

- Ebaid, I. E. (2021). Cheating among accounting students in online exams during COVID-19 pandemic: Exploratory evidence from Saudi Arabia. Asian Journal of Economics, Finance and Management, 3(1), 211–221.

- Fogarty, T. (2020). Accounting education in the post-COVID world: Looking into the mirror of erised. Accounting Education, 29(6), 563–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2020.1852945

- Guangul, F. M., Suhail, A. H., Khalit, M. I., & Khidhir, B. A. (2020). Challenges of remote assessment in higher education in the context of COVID-19: A case study of Middle East College. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 32(4), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09340-w

- Halabi, A. K. (2021). Pivoting authentic assessment to an accounting podcast during COVID-19. Accounting Research Journal, 34(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-08-2020-0219

- Kostons, D., van Gog, T., & Paas, F. (2012). Training self-assessment and task-selection skills: A cognitive approach to improve self-regulated learning. Learning and Instruction, 22(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.08.004

- Kupiainen, S., Hautamäki, J., & Karjalainen, T. (2009). The Finnish education system and PISA. Ministry of Education Publications. Available at https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/75640 Accessed 27.9.2022.

- Lucas, U., & Mladenovic, R. (2004). Approaches to learning in accounting education. Accounting Education, 13(4), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963928042000306783

- Lucas, U., & Mladenovic, R. (2014). Perceptions of accounting. Chapter 6 in the Routledge Companion to accounting education (Edt. Richard M.S. Wilson), 125–144.

- Macias, H., Patino-Jacinto, R. A., & Castro, M. F. (2021). Accounting education in a Latin American country during COVID-19: Proximity at a distance. Pacific Accounting Review, 33(5). https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-11-2020-0198

- Mali, D., & Lim, H. (2021). How do students perceive face-to-face/blended learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic? The International Journal of Management Education, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100552

- Miihkinen, A., & Virtanen, T. (2018). Development and application of assessment standards to advanced written assignments. Accounting Education, 27(2), 121–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2017.1396480

- O’Connell, B. (2021). He who pays the piper calls the tune’: University key performance indicators post COVID-19. Accounting Education, 31(6), 629–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2021.2018338

- Puustinen, M., & Pulkkinen, L. (2001). Models of self-regulated learning: A review. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 45(3), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830120074206

- Sangster, A., Stoner, G., & Flood, B. (2020). Insight into accounting education in a COVID-19 world. Accounting Education, 29(5), 431–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2020.1808487

- Tharapos, M. (2021). Opportunity in an uncertain future: Reconceptualising accounting education for the post-COVID-19 world. Accounting Education, 31(6), 640–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2021.2007409

- Ustun, U., & Eryilmaz, A. (2018). Analysis of Finnish education system to question the reasons behind Finnish success in PISA. Studies in Educational Research and Development, 2(2), 93–114.

- Vermunt, J. D. (1998). The regulation of constructive learning processes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 68(2), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1998.tb01281.x

- Yoon, J., & Järvinen, T. (2016). Are model PISA pupils happy at school? Quality of school life of adolescents in Finland and Korea. Comparative Education, 52(4), 427–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2016.1220128

- Zarzycka, E., Krasodomska, J., Mazurczak-Maka, A., Turek-Radwan, M., & Jin, H. (2021). Distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Students’ communication and collaboration and the role of social media. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2021.1953228