Abstract

Despite extensive enquiry into the socio-political aspects of environmental impact assessments (EIA), empirical material from east- and south-east Asia remains underrepresented in English-language scholarship. This is notable given increasing infrastructural developments and interest in environmental justice in the region. We contribute to this field by evaluating the Miramar Resort EIA controversy in Taitung County, Taiwan, to assess how a developer and a local government conspired to circumvent an EIA process. Through documentary analysis and stakeholder interviews, we assess the argumentation used by different actors to articulate their support for or opposition to the development. We find that much contention rests on claims to economic benefit and environmental protection that cannot be verified, and on limited participation opportunities. We call for further research into strategies used by proponents to discredit the knowledge and experience of opponents within EIA processes, especially given rising global interest in traditional, local and indigenous knowledge.

1. Introduction

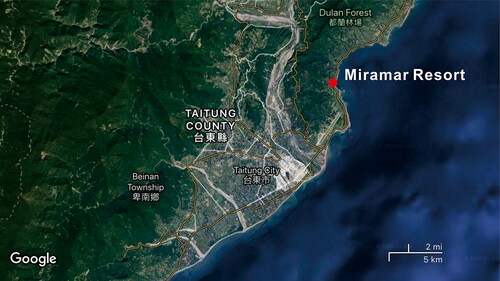

Despite a long tradition of scholarship into controversies around environmental impact assessment (EIA) and a widespread understanding in the social sciences that EIAs are socially and politically mediated, the body of English-language literature into EIA controversies in an east- and south-east Asian context is still developing. Although a number of studies exist at the state- or regional level into environmental assessment for large-scale infrastructure in east- and south-east Asia (e.g. Johnson (Citation2014) on China; Hwang (Citation2017) on Korea; Blake and Barney (Citation2018) on Lao PDR), empirical assessment of site-specific controversies and their impacts on communities is more limited (Fan, Chiu, and Mabon Citation2020). Given the level of expected infrastructural development (Moser Citation2020) and rising interest in the justice dimensions of responses to environmental change (Chou et al. Citation2020) for east- and south-east Asia, it is timely and relevant to consider how understandings of the societal contours of EIA processes derived from Global North contexts are applicable to east- and south-east Asia, especially as regards emerging economy and new democracy settings. This paper responds to this growing field of scholarship through empirical evaluation of the Miramar Resort controversy in Shanyuan Bay, Taitung County, Taiwan. The Miramar Resort issue is a long-running controversy over the legality of the EIA process for a resort hotel built on the coast of Taitung County in eastern Taiwan, in which the local government was accused of conspiring with the developer to circumvent EIA regulations and fast-track approval of the development. We link our enquiry to existing empirical and conceptual material, in order to make sense of the strategies used by the developer and local authority to circumvent a well-intentioned EIA process, and to understand how communities and less empowered stakeholders’ knowledge and experiences may become discredited within environmental assessments.

2. Conceptual background: environmental controversies and the potential for manipulation

An EIA is defined by Taiwan’s Environmental Protection Administration (2019: np) as “the processes of identifying, predicting, evaluating and mitigating the biophysical, social, and other relevant effects of development proposals prior to making major decisions and commitments.” Puig and Villarroya (Citation2013) add that on the basis of an EIA, avoidance, minimization, or compensation strategies may be adopted to counter environmental impacts.

Nonetheless, EIAs do not necessarily provide objective or value-neutral assessment of environmental impacts, nor do they automatically lead to courses of action deemed most beneficial to the environment and society. The role of “science” and evidence in EIAs is not without contest (Cashmore Citation2004), and power and political dynamics may be significant within EIA research (Cashmore and Richardson Citation2013). It has long been argued that controversy is an integral part of technology assessment, and hence that assessment of technologies and their impacts is an inherently social process (Cambrosio and Limoges Citation1991). Lyytimäki and Peltonen (Citation2016) therefore conceive of EIAs as focusing events, which can influence opinion and set agendas around a project or the development trajectory of a locality. The social and political dynamics which arise during the process of an EIA may hence be influenced by – and yield valuable insight into – broader issues affecting a locality beyond a site-specific project, such as in whose interest the environment is managed, whose knowledge counts, and who holds power over environmental policy and planning decisions.

There are numerous examples globally of controversy within EIAs for new infrastructure projects. Looking to the EIA process for the Tseng-Wen Reservoir Transbasin Water Diversion Project in Taiwan, Fan (Citation2016) argues that the EIA process is inadequate to interpret local (especially indigenous) cultural heritage or to account for socio-economic impacts. Reflecting on an EIA for coastal defenses and their effects on fish farms in the Basque Country, Spain, Puig and Villarroya (Citation2013) believe there is a degree of subjectivity in identifying and assessing environmental “impacts”, and that there are limits to the ability of economic methods to adequately determine “compensation” for environmental impacts. For EIAs in onshore renewable energy developments in Scotland, UK, Smart, Stojanovic, and Warren (Citation2014) identify a lack of clarity on the purpose of an EIA, and question the ability of EIAs for site-specific projects to assess the impacts of projects on regional- or global-scale processes such as ecosystems and climate change. Spiegel (Citation2017), in the context of EIAs for small-scale mining in Zimbabwe, argues that enactment and enforcement of EIA processes may embody ideas of how the environment “ought” to be managed and by whom, often at the expense of small-scale and artisanal practitioners (in Spiegel’s case, miners).

Whilst the above is not intended to be an exhaustive list of examples, it gives a sense of the methodological limitations of an EIA process and the power imbalances that may be contained within. Nevertheless, although scholars such as Cambrosio and Limoges (Citation1991) see controversy and participation as a valuable part of technology assessment, ability to participate in an EIA process is not equal across society (Tu Citation2010). Nor is it the case that all actors participate in good faith. Enríquez-de-Salamanca (Citation2018) provides a typology of how the limitations outlined above may lead to the good intentions of an EIA being hijacked by progress-oriented proponents of developments, or by opponents of a project. These are: using false information in support of one’s position; proposing false alternatives or unnecessary elements to create an illusion of choice and steer actors toward a desired outcome; exaggerating information on the benefits or drawbacks of a development; hiding information about the objectives or the characteristics of a project; undervaluing or over-valuing impacts to downplay or emphasize the effect the project will have on the surrounding environment; providing confusing or complex information to discourage publics unfamiliar with techno-scientific language from participation; self-censorship by actors to avoid conflicts or reprisals; administrative manipulation of the EIA process by strategically timing announcements or finding ways to circumvent the process; offering bribes and kickbacks; and taking advantage of relationships of dependency in a manner amounting to extortion.

In this paper we take Enriquez de Salamanca’s typology, and the associated scholarship and case studies on EIA controversies as a social process and use the case of the Miramar Resort development in Taitung County, Taiwan, to elaborate how a developer and local authority may work to exploit the inadequacies of an EIA and generate a desired outcome in practice.

3. Context: the Miramar resort dispute and environmentalism in Taiwan

3.1. The Miramar resort dispute

The focus of this paper is the controversy over the Miramar Resort development in Shanyuan Bay in Taitung County, in the southeast part of Taiwan. Contestation over the Miramar Resort has lasted for over a decade (see timeline in ), and has centered on the legality of the EIA conducted for the project. Taiwan’s Central Mountain Range has blocked Taitung Country from the western plain of Taiwan, where most of the country’s development has taken place. The level of development here has been far slower than the west part of Taiwan, hence a significant proportion of the natural landscape remains. The eastern part of Taiwan is regarded as a pure “back garden” for Taiwan free from damage from development, and hence is argued to function as a “retreat” for people from elsewhere in Taiwan (Lin Citation2013; Huang Citation2014).

Table 1. Timeline of Miramar Resort Conflict.

Taitung County and Shanyuan Bay may be considered a peripheral region according to the three criteria of Kühn (Citation2015). Lack of innovation through low-qualified work and decline of employment is illustrated by a decline in the number of working age people in employment from 122,405 in 1990 to 98,295 in 2000 and 86,253 in 2010 (DGBAS Citation2010). Poverty through out-migration and stigmatization may be reflected in the reduction of the population of Beinan Township (in which the Miramar Resort is located) from 24,420 in 1981 to 17,132 at end of 2019 (Ministry of Interior Statistics Citation2021); and also by the land price index for Taitung County, which in 2013 (at the time of the development) was 79.91 for Taitung compared to 90.34 for Taiwan as a whole, indicating notably lower land values in Taitung (Ministry of Interior Statistics Citation2021). Powerlessness via dependency in decision-making and exclusion from networks can be seen through the markedly higher proportion of indigenous people – an often disempowered and marginalized group in Taiwan – at 36.47% for Taitung County as of 2020 compared to 2.45% for whole of Taiwan (Ministry of Interior Statistics Citation2021); and by the statement of the governor of Taitung County on the cancellation of the Miramar Resort project claiming that the county relied upon external investment for development (UDN News Citation2018). Understanding Taitung County, and especially Shanyuan Bay, as a peripheral region matters in an EIA context because extant research indicates that the social, economic and environmental marginality of peripheral regions may create uneven power relations in development processes (Butler and Hinch Citation2006; Karrasch and Klenke Citation2016) and make it hard for communities and local authorities to be able to resist new development proposals (Blowers Citation1999). As the literature in Section 2 and our analysis and discussions in Sections 5 and 6 illustrate, this peripherality may create conditions for the kind of manipulative practices in EIAs outlined by Enríquez-de-Salamanca (Citation2018) to take hold.

The Miramar Resort sits in Shanyuan Bay (see and ). The bay used to be a lido and is a natural sand beach, different to the more rugged coastal topography typical of eastern Taiwan. The Amis indigenous name for the coastal area is Fudafudak, but the name of Miramar Resort in Mandarin – Meiliwan – means “beautiful bay”. This “beautiful bay” was used as a selling point to attract tourists to the Miramar Resort. Tourism indeed has a central role in Taitung County’s economic development (Taitung County Government Citation2018; Mak Citation2017). However, whilst the beautiful scenery forms the basis of a tourist resort, other values and interests are invested in the landscape. The Amis people, a branch of Taiwan’s indigenous people, dwell closely to the resort site. Specifically, a tribe called the Tzu-Tung inhabit the southern part of Shanyuan Bay (Tai, Kong, and Kou Citation2012). Viewing the ocean as a foundation of nature and interacting with the natural environment in a harmonious way is core to how the Amis people value the environment (Smith Citation2015).

Although the physical construction area of the Miramar Resort is relatively small, the dispute over the resort was not resolved for more than ten years. Developer Miramar and the Taitung County Government (the local government representing the locality) were in favor of the development. Some members of the Amis people, environmental protection groups such as the Wild at Heart Legal Defense Association and Citizen of the Earth were however in opposition (see summary in ). As we will illustrate, there is of course a diverse range of views within the “for” and “against” positions.

Table 2. Roles of key actors within Miramar Resort development, EIA and operation.

Groups opposed to the resort development accused Miramar of intentionally avoiding conducting an EIA prior to construction. The Miramar Resort asked Taitung County Government to fit their development needs and modify land numbers to create a new separate parcel of 9,997 m2 for the Resort to build their main building. Taiwanese EIA regulations state that the requirement area for conducting an EIA is 1 hectare. Thus, a 9,997 m2 parcel is excluded from this restriction. This led to claims that developers Miramar were deliberately avoiding doing an EIA. It is also notable that because Miramar submitted their application as a general hotel, the EIA would be overseen by Taitung County Government. Had they applied as a tourist hotel, the application would have been assessed by the central government.

Environmental lawyer Chan (Citation2013) explains that the local government (Taitung County Government) held three roles in the planning and development process for the Miramar Resort. Taitung County Government was (a) the contracting party for the Miramar Resort Build-Operate-Transfer project (i.e. the project’s public sector partner); (b) the competent authority regulating the hotel’s business, given that the EIA was submitted as a “general” hotel and not as a “tourist” hotel; and (c) the competent authority overseeing the EIA for the project. The developer (Miramar Resort) meanwhile is the private sector partner for the build-operate-transfer project; the applicant for the hotel’s development and operation; the producer of the Environmental Impact Statement for the Miramar Resort; and the organization responsible for the construction of the resort infrastructure itself. Chan (Citation2013) thus points out that the developer and the regulator enjoyed a symbiotic relationship across the EIA process. As we discuss in Section 5, the local government in Taitung County have been argued to be culpable in making the dispute last as long as it has, in that they continued to grant construction permits to the Resort and did not supervise the developer to undertake a rigorous EIA. In addition to claims over the legitimacy of the EIA process, claims around the living rights of indigenous people have also been raised (Wei Citation2018). After many years of court orders to stop construction, the EIA which citizens had claimed was invalid was finally cancelled. As of spring 2021, the resort building remains constructed but unused.

3.2. The Taiwanese context: challenges and applicability

An additional contribution of our research to the international literature is as a case of an EIA controversy for a relatively new democracy. Indeed, the wider socio-economic context in Taiwan has significant bearing on environmental governance in the country today, hence is worth outlining briefly here. In 1949, the KMT retreated to Taiwan after losing the Civil War, constructing rapidly and intensively (Grano Citation2014; Citation2015). Under Martial Law, all decisions were made under a totalitarian process (Williams and Chang Citation2008). During this time period, development followed the United States and Western model, where high-intensity development over a short period of time created Taiwan’s “economic miracle” (Williams and Chang Citation2008; Grano Citation2015). Yet the emergence of serious environmental problems indicates local environments were being sacrificed to boost national economic growth (Grano Citation2015).

Environmentalism in Taiwan initially came from the grassroots level before being taken up by the middle classes, a large proportion of whom were educated in the United States in the 1980s (Hsiao Citation1999; Grano Citation2015). Along with the end of Martial Law in 1987, the Environmental Protection Administration was established in response to environmental problems. Taiwan’s democratic transition in the 1980s to the 1990s lessened state control and enhanced environmental governance (Grano Citation2015; Wong Citation2017). Despite this increasing environmental consciousness, in Taiwan environmental concerns arguably remain inferior to economic growth among decision-makers (Williams and Chang Citation2008; Ho Citation2010). Taiwan’s economy started to embrace neoliberalism in the 1990s, as illustrated by cooperation between government and private sectors on build-operate-transfer (BOT) projects (Tai, Kong, and Kou Citation2013).

Taiwan’s Environmental Impact Assessment Act was enacted based on the United States’ EIA Law in 1994, and was initially criticized as a means of helping bureaucrats to “rubber stamp” construction (Ho Citation2004; Tai, Kong, and Kou Citation2013). The EIA Act has also arguably come too late, lacking independence and being over-simplified (Tai, Kong, and Kou Citation2012; Chen Citation2014). Although Taiwan has followed the United States’ EIA template, some contents differ. Taiwan’s EIA asks the project developer to provide an environmental assessment report, with the assessing experts gathering only for the assessment meetings – which act as the final decision for the project (Tu Citation2012). This “quick build” way of processing the EIA, under a constrained timeframe, presents many shortcomings, such as over-reliance on techno-scientific knowledge, inaccuracy of reports, and insufficient communication between experts and local residents such as indigenous people (Tu Citation2012). Indeed, it has been argued that an uncritical reliance on “science” has contributed to environmental crises in Taiwan (Hsiao Citation1990), with technological determinism and technocratic governance weakening public participation and leading to deficiencies in Taiwanese EIAs (Hsu and Hsu Citation2001; Tai, Kong, and Kou Citation2013).

In short, there remains a general belief in the reasonable, objective, and neutral nature of science within Taiwan. Yet such reliance on “objective” evidence when assessing the effects of a proposed development risks neglecting other factors such as communication between stakeholders, local residents’ voices, or indigenous people’s culture in disputes (Fan Citation2006; Tu Citation2012). Since 2018 the EPA has begun a review and amendment of the EIA Act, proposing to add a sub-law of social impact assessment under the EIA Act (EIA Act Article Five from Environmental Protection Administration 2018). Recent research into EIAs in Taiwan has focused on the efficiency and perfection of EIA processes (Tu Citation2012; Chen Citation2014); discussing the improvement of EIAs in relation to existing ideology (Tai, Kong, and Kou Citation2013; Chen Citation2014); and the politicization of environmental issues to garner political support (Chen Citation2014; Grano Citation2015).

4. Methodology

This paper takes a single case study approach. As per Yin (Citation1984), the value of a single case study lies in contributing to theory, rather than providing generalizations across society. In this regard, the study aims to contribute to understandings of how proponents of a development (in this case a developer and a local authority working in partnership) can act to manipulate the good intentions of an EIA process, by providing an empirical evaluation of themes identified in extant scholarship into the socio-political dimensions of EIAs and challenges around fair and equitable participation in EIAs. Although we do not claim our results are representative of a larger population, it is nonetheless the case that empirical studies of environmental controversies in east- and south-east Asia are more limited than counterparts from the Global North (Fan, Chiu, and Mabon Citation2020); hence the study also aims to contribute to the geographical diversity of extant literature on the social dimensions of EIA controversies. We return to draw links to this wider literature in Section 6.

4.1. Collation and qualitative content analysis of textual materials

The first step of the research involved collation and qualitative content analysis (Mayring Citation2019) of statements and reports relating to the dispute and to the environmental assessment process. The objective of this was to construct a broad-based understanding of the types of arguments used by key actors in the Miramar Resort dispute, and understand the different standpoints at play. Relevant material was collected by sampling news reporting and the online presence of organizations with an interest in the dispute (identified through news reports). These included the Miramar Resort’s official website, blogs of opposition groups, environmental NGO websites, and news sites (see below). Notes of the content of these websites were taken to compare similarities and differences in the argumentation used, and subsequent analysis followed a directed content analysis approach, as outlined in more depth in Section 4.3., whereby the content of material was assigned to pre-determined categories relating to overarching research questions the study sought to address.

Table 3. Core documentation consulted for qualitative content analysis.

4.2. In-depth interviews

Whilst the documentary material consulted is of value in mapping out the standpoints of the actors and their lines of argumentation, it may be less useful in clarifying the wider contextual factors which inform how people make sense of the impacts of a development on their lives. Given the complexity of factors raised in Section 2 around EIAs, peripheral communities, and environmental assessment processes, in-depth interviews were conducted to assess how the Miramar EIA debate fits into broader narratives of a sense of place and an appropriate development trajectory for Shanyuan Bay and Taitung County.

Following the methodology outlined in Huang and Mabon (Citation2021) semi-structured interviews were conducted with seven key informants, representing five organizations closely related to the development and two outsiders with previous experience of the issue. Recruitment sought to represent a number of viewpoints relating to the Miramar issue. Initial participants were identified through the content analysis outlined in Section 4.1. (see ), and further interviewees were recruited via the “snowball” sampling method. Research of this nature, which draws wider insights from in-depth consideration of specific cases, requires the views of those who can provide context-specific understanding through their significant knowledge of the issue at hand. Accordingly, focused samples of comparable size, targeted at those who can make meaningful contributions to the dataset, have been used in analogous case-based research elsewhere (e.g. Mehnen, Mose, and Strijker Citation2013; Boeckmann Citation2016; Nordberg and Salmi Citation2019).

Table 4: Summary of Interviewees and Relationship to Conflict.

Interviews proceeded around a loose set of questions, with further follow-up questions depending on interviewees’ responses. Therefore, the questions of each interviewee were slightly different, following the idea of a semi-structured interview as a “guided conversation” (Bryman Citation2012). However, each interview sought to cover (a) the respondents’ general views toward the Miramar Resort and the EIA process; (b) the history and context of their relationship to the issue; (c) their perceptions of fairness within the project; (d) their thoughts on how environmental assessment ought to proceed in such socially-complicated situations such as the Miramar dispute; and (e) their own personal environmental values to understand the wider context of their responses to the issue. All interviewees consented to participate in and knew the purpose of the research. All interviews were undertaken in Chinese.

4.3. Analysis

Both the documentary and interview analysis proceeded according to directed qualitative content analysis, meaning that the materials were read to identify pre-determined ideas and themes, but that the researcher was also free to note any other themes which had not been expected beforehand yet appeared significant (e.g. Mayring Citation2019; Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). As outlined in Huang and Mabon (Citation2021), this allowed for relatively structured analysis between cases and enabled the documentary material and the interview material to be considered together under common themes (Cho and Lee Citation2014) given the relatively small sample size, but also gave room for us to note new themes and material emerging during the reading. Accordingly, material was read and coded primarily for statements which (a) indicated the speaker’s overall standpoint toward the Miramar conflict; (b) indicated the speaker’s perceptions of the impact assessment process, including both what constituted an “impact” and how the process itself was undertaken; and (c) gave an indication of how and in what ways participants indicated their values toward the environment (e.g. statements ascribing an economic value to the natural environment; statements ascribing a spiritual value to the natural environment etc). All analysis was undertaken as far as possible on the original Chinese material, with indicative quotes subsequently translated into English. Compared to our previous research in this area which focused more narrowly on the controversy around the Miramar Resort in relation to issues of sustainable consumption (Huang and Mabon Citation2021), in the findings and analysis that follows we conduct new and further analysis into how different actors viewed the Miramar Resort EIA controversy, and how they justified or opposed the developer and local government’s combined efforts to direct the EIA process toward approval of the resort.

4.4. Rigour

Our methodology was guided by the four principles of rigour in qualitative research elaborated for geographical research by Baxter and Eyles (Citation1997). Credibility was worked toward through purposeful sampling, to ensure that interviewees and documents, whilst giving a small sample size, represented a broad range of different standpoints on the Miramar controversy, This was supported by persistent observation, following the debate via media over several years in order to build an in-depth understanding among the research team. Transferability was facilitated via the kind of thick description Baxter and Eyles advocate – that is, whilst we do not claim our results are generalizable to a wider context, in Section 3 we have sought to provide adequate information on the Miramar Resort and on the Taiwanese context for a reader to be able to understand the context of our claims. Dependability is worked toward through triangulation (i.e. using textual/documentary materials as well as interviews), and mechanically recorded data via manual noting of key points from texts and quotes from interviews. Finally, confirmability is facilitated through audit trail products in Section 5, namely quotes from the in-depth interviews and the documentary analysis to evidence the points made.

5. Findings

5.1. Actors’ standpoints and rationales

Our first thematic area concerns how different actors involved in the dispute justify their stance toward the project. Both Taitung County Government and the Miramar Resort developer claim the project to be “sustainable” in that it uses Shanyuan Bay’s natural environment as a resource to bring local socio-economic benefit:

Taitung County possesses a lot of natural resources, we choose to work on doing tourism as our main industry. (Taitung County Government representative)

A good condition of environment is the selling point and demand of our resort’s aim. Furthermore, the project had signed a 50 year contract, the Miramar Resort will not kill the goose that lays the golden eggs. (Miramar Resort section managerFootnote1)

In both quotes, preservation of environmental quality is argued to be a necessity to unlock socio-economic benefit. Indeed, Taitung County Government’s wider messaging and publicity taps heavily into this idea of “naturalness” to draw tourists to the county (Taitung County Government Citation2018). By contrast, those in opposition to the project – or at least with concerns over it – expressed skepticism over the ability of a development undertaken in the name of uplifting the local economy to actually return benefit to the area’s citizens:

As the Shanyuan Bay is an aboriginal peoples’ traditional area, the project should get the agreement from the tribe in the beginning […] because of the operation of the local government to influence the lowly-informed Taitung local community to believe in economic growth through this project, most of the local people are supporting this project. (Local indigenous activist)

Although the Miramar Resort provides the public a better service than a lido, a company which will invest in a lido is not mainly to offer a good service for customers. They are seeking benefits from these customers. (Online opposition group administrator)

Notably, rationales for opposing the development encompass a range of concerns, stretching far beyond the potential environmental impacts of the Miramar Resort. These include lack of trust in the local government’s message of economic growth, suspicion of the motivations of the developer, and procedural issues relating to who has the right to make decisions about the land. Even for local social sustainability in the form of jobs and economic benefit, skepticism exists about the extent to which the project will benefit the locality. Environmental lawyer Chan Shun-Kuei, was reported as quoting “the words of Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz […] that the development claimed by Miramar would only concentrate 99% of the benefits in the hands of 1% of the population, which is not a real public interest, and that the so-called job opportunities are only low-level jobs” (PeoPo Citizen Journalism Citation2012: n.p). Miramar countered this claim by arguing that the resort would employ a number of local young people – including in management roles – and that the employment would help to retain local talent and solve other problems such as an aging local population (Miramar Resort Official Website Citation2019). Regardless of the veracity of both sides’ claims, this again illustrates the differing interpretations at play as to whether or not a development predicated on appreciating the environmental quality of the area does indeed deliver positive social and economic impacts at a local level.

It is also important to note the different actors who come together here in the common direction of opposing the development. Whereas the indigenous activist is local to Shanyuan Bay, the Oppose the Miramar Resort opposition group use social media to gain traction, and other opposition groups are run largely out of the Taipei Metropolis area and have a nationwide reach. Many of the opponents to the project – those most vocal in their claims to the environmental and social harms of the resort – are hence “outsiders” staking a claim to the future of the bay. As we now discuss, this can give rise to subtle variations in how and why claims to environmental “impact” are made.

5.2. Claim-making around potential environmental “impacts”

We now evaluate how different actors make claims to environmental “impacts” arising from the Miramar Project. We focus on what kinds of claims are considered admissible within formal planning processes, and also what the potential range of outcomes from the impact assessment process may be.

As outlined earlier, environmental “impacts” in Taiwan are understood at government level as “biophysical, social and other relevant effects”, which can be identified, predicted, evaluated and mitigated (Environmental Protection Administration Citation2019). This idea of there being an appropriate manner and process through which environmental impacts “ought” to be assessed is adopted by Taitung County Government to discredit actions from those opposed to the development. In an official statement, the county government claimed that to derail the Miramar project, some citizens broadened the interpretation of the judgment recklessly, misled other citizens to believe the building must be deconstructed before the EIA could be done, and tried to interfere with the decision making of the EIA investigators (Taitung County Public Work Bureau Citation2012). Actions lying outside of the formal EIA process and the people undertaking these actions (e.g. people circulating images and texts through the internet) come to be viewed as “irrational”. This idea was expressed strongly in Miramar’s official statements, and also by a Taitung County Government representative:

Only few opponents will attend [EIA] meetings, and they are all too emotional. Sometimes the opponents did not attend the meetings because they would be isolated by supporters who are the majority. (Taitung County Government representative)

Describing opponents as “emotional” has the effect of allowing both the Taitung County Government and the Miramar Resort developers to position themselves as taking a reasonable stance. An interviewed Miramar Resort representative for instance stated that “the Miramar Resort always hope they could have a rational conversation with the opponents” (interview with Miramar Resort senior representative). The work of Miramar to position themselves as a “rational” actor is reflected in the title of website which the developer built to set out their position on the controversy – “Miramar Facts” (http://www.miramarfacts.com.tw, now offline). Positioning actions lying outside of the formalized, measurable EIA process as being irrational also has the effect of closing down the debate and excluding – or at least portraying as somehow negative and of less value - a number of more value- or emotion-driven arguments against the resort. Consider, for instance, the following:

The aboriginal people often regard the mountains or the ocean as our mother, you can say you love your mother, you are a child of the ocean, but only share the environment, not possess it. (Local indigenous activistFootnote2)

I am selfish since I yearn for leaving these beautiful mountains and seas to our next generations. In order to achieve this selfishness, we only could keep making effort on it. (Environmental NGO representative)

In both cases, the respondents’ concerns about the development come from a deep-seated sense of who they are and how this drives their view of what a sustainable trajectory is for the landscape. Similar to Cass and Walker (Citation2009), this illustrates that regardless of any claims to “rationality” or otherwise, emotions can and do drive people’s responses to changes in the environment in profound ways. As such, attempts to dismiss such arguments as “irrational” and lying outside of EIA structures may underestimate the strength of feeling and resolve held and/or lead decision-makers to miss the point of why some people oppose developments such as Miramar. In any case, even within empirically-driven, process-based EIAs, as per Bradbury et al. (Citation1994), Miramar opponents are able to use the language of science and decision-making to justify their opposition:

Since humans’ life relies on the environment, the environment is very important to us. In my opinion, the environment’s value is levelled by its degree of development. (Online opposition group administrator)

We only heard the Miramar Resort makes a lot of promises, but we do not know “how” they exactly fulfil their promises. What is more, in fact, the condition of engagement is based on the fact that we cannot ask them to deconstruct. (Local indigenous activist)

Here, the logic of understanding natural systems and of using an EIA as a basis for decision-making are turned on their head by opponents. In the first quote, humans’ dependency on the environment is drawn in to suggest the resort may pose a threat to humans’ lives. In the second, Miramar and Taitung County Government’s lack of specificity in clarifying the range of outcomes that may be possible from the EIA (i.e. deconstruction not an option) challenges the very idea of an EIA being used to guide the most fitting course of action. This questioning of the EIA process itself forms our final area of concern.

5.3. Contestation over the EIA process

This section builds on our argument in Section 5.2. about the kinds of arguments that are seen to count in relation to the Miramar Resort’s potential environmental impact. Over time, the Miramar Resort debate seems to become more about the propriety of the EIA process, rather than the substantive nature of any environmental impacts. This touches on issues of justice in both the process itself and recognition of those with a stake in the issue.

From a procedural perspective, the perceived inadequacy of citizen consultation is explicitly cited in opposition from Citizen of the Earth, a Taiwan-wide environmental organization:

The Miramar Resort project, from rendering the profile to doing the EIA and construction process, is not in accordance with the procedural justice process. The Taitung County Government misinterpreted the laws and ignored the administrative court’s judgement. This act will encourage other projects to follow. This goes against sustainable development and green economics. (Citizen of the Earth, content from petition)

Here, fair process is argued to be an integral part of sustainable development more generally. Under this argumentation, an inadequate EIA does not only risk environmental damage, but may also contribute to an unsustainable societal form. Concerns over lack of meaningful opportunity to participate in the process seem at least in part supported by the content of illustration meetings and records of citizen interaction, which are attached to the Miramar Resort’s environmental impact statement (Miramar Resort Project Environmental Impact Statement, Miramar Resort Citation2008). According to the first illustration meeting in 2006, no more than ten local people attended it, with discussion on job opportunities and preferential services for the local community. Although the voices of opponents appear until 2007, from what the records show (Miramar Resort Project Illustration Meeting 2006 and 2007, Miramar Resort n.d.), the form of the meeting is set as people asking questions and then the resort answering, as opposed to a more dialogic or conversational format.

From a recognition perspective too, interviews revealed differing perspectives on the appropriateness or effectiveness of consultation meetings:

Citizens were informed only three days before the [Sixth] EIA [Meeting, 2 June 2012]. What is more, general citizens could not sit in and convey opinions by paper, only the representatives of each side (support and against) could attend the meeting and make contributions. (Local indigenous activist)

We did not communicate with each other, each side’s standpoint is very clear. Therefore, the perspectives have nothing in common with each other […] an ideal communication in Taitung communities, especially with indigenous groups, is difficult to occur. (Online opposition group administrator)

The online opposition group administrator goes on to elaborate that the difficulty of an ideal communication seems to be that as Taitung County is a less-developed area, most of the adults are moving out to the west part of Taiwan for jobs (as per the socio-economic data presented in Section 3). Therefore, the local communities are formed mainly by children and older people, and those who have less ability and knowledge to speak for themselves and may even be willing to follow any policies that the government decides. Moreover, disenfranchized populations also include indigenous people, where problems will probably be more serious since some older people cannot even speak Mandarin (interview with social observation student). These claims indicate that to even participate in the EIA, one would require a certain level of knowledge of how the system works, and be able to speak Mandarin. This gives rise to potential for claims of injustice in recognition, given the difference between the idealized EIA process and the characteristics of the local community directly affected.

What comes across strongly in the above is that the Miramar Resort EIA controversy goes far beyond contestation over the environmental impacts themselves. Rather, the controversy becomes about different kinds of people and different identities, who is considered able to participate in decision-making, and who has the power to make decisions about the future development trajectory of the landscape. Further complicating this process, it is also worth reiterating that within the coalition of opposition there exist a range of identities and affiliations. Each of these may have their own differing views on what an ideal society ought to be, yet they are able to coalesce around the idea of the Miramar Project as an example of how they do not wish decisions about the environment to be made.

6. Discussion

We discuss our findings and their implications for scholarly literature on the socio-political aspects of EIAs by returning to the characteristics of EIA manipulation identified by Enríquez-de-Salamanca (Citation2018). We consider these characteristics in groups, and discuss if and to what extent each is present in the Miramar case. Based on the Miramar experience, we also offer insight into additional ways in which developers and proponents may conspire to manipulate an EIA process.

A first cluster of characteristics identified by Enríquez-de-Salamanca (Citation2018) concerns the presentation of information within an EIA – specifically false information, exaggerated information, or hidden information. Whilst there is no evidence of outright false information in the Miramar EIA process, there are arguably claims of hidden and exaggerated information on the part of the developer. Hidden information comes through concealing the true purpose of the resort at the outset of the EIA process – by registering the hotel as a “general” hotel and not a “tourist” hotel and thereby influencing the parameters against which the EIA is judged – and through marking a piece of adjacent land on the environmental statement merely as a “hillside” and not as land with significance to the local indigenous population (Huang and Mabon Citation2021). In both these cases, information which could influence the scope and content of the EIA is hidden by omission. Claims to exaggerated information, meanwhile, arise in Miramar in relation to the perceived economic and employment benefits of the development to the local community. As outlined in Section 5.1., the developer’s arguments of employment and economic benefit are challenged by resort opponents on precisely the grounds that the information provided by the developer is exaggerated (PeoPo Citizen Journalism Citation2012). However, in relation to Enriquez de Salamanca’s observations, what the Miramar resort shows is that it may be difficult to prove a developer or authority is concealing information by omission or exaggerating impacts. In this sense, the Miramar findings reinforce those of Puig and Villarroya (Citation2013) in the Basque context on the need for acknowledgement of the limitations of economic projections within EIA processes; and Fan (Citation2016) in the Taiwanese context on the difficulties of understanding and delineating local cultural heritage within more technically-driven EIA processes.

A second characteristic identified by Enríquez-de-Salamanca (Citation2018) is that of false alternatives or unnecessary elements. Whilst Enriquez de Salamanca makes this point in the context of a developer creating the illusion of choice by proposing unfeasible or undesirable alternatives and thus guiding the EIA toward a desired outcome, false alternatives arise for Miramar as the creation of an arguably false choice between allowing the development to happen or losing out on economic growth opportunities. For instance, after the Miramar developer withdrew from the project in 2018 following repeated failures to gain EIA approval, Taitung County Mayor Huang Chien-Ting was quoted as saying that “most of the opponents are not local people, they don’t understand Taitung’s development, they think they are righteous, yet they ignore the impact of this dispute could lead to a chilling effect and let Taitung’s beautiful 176 km coastline become useless and deterring enterprises to invest” (UDN News Citation2018). Attempts to steer environmental assessments and environmental controversies toward an either-or dichotomy have similarly been identified in other industrializing peripheral regions by Fan, Chiu, and Mabon (Citation2020), who observed developers telling opponents to the Ha Tinh Steel plant in Vietnam to “choose” between steel or shrimp farming; and by Childs (Citation2019) in relation to the Solwara 1 deep sea mining project off the coast of Papua New Guinea, where developers and proponents position deep-sea mining as “necessary” to provide raw materials for green energy infrastructures. In terms of Enriquez de Salamanca’s principle of false alternatives or unnecessary elements within an EIA, what the Miramar Resort indicates is that a developer or proponent may introduce false choice dichotomies as a way of closing down the EIA to a narrow discourse of modernization for a locality, in a way that sidelines potential for the continuation of, for example, small-scale or artisanal practices (Spiegel Citation2017).

A third set of characteristics drawn out by Enríquez-de-Salamanca (Citation2018) is to undervalue or overvalue impacts. What happened at Miramar was that – deliberately or otherwise – the commencement of construction before completion of the EIA made it difficult to establish whether any environmental impacts were in fact the result of the development. NGO Citizen of the Earth claimed, on the basis of coral reef examinations and onshore ecological surveys, that buried construction waste from the resort had caused heavy metal pollution. However, as construction had already commenced, it became difficult to produce a formally acknowledged baseline against which claims to environmental “impact” (like those made by Citizen of the Earth) could be assessed or valued. As well as the obvious point that an EIA is insufficient to guard against damage to the environment if it cannot be undertaken and enforced prior to the commencement of development, the Miramar controversy adds nuance to Enriquez de Salamanca’s observation of the under- or over-valuing of impacts by illustrating the subjective nature of evidence-making for environmental valuation and impact assessment (see also Puig and Villarroya (Citation2013) in the Basque context on the difficulties of delineating damage to fish farms caused by environmental interventions). Furthermore, building on Smart, Stojanovic, and Warren’s (Citation2014), claims to the under- or over-valuation of environmental impacts specific to a development may become even harder to verify as developments take place under an ever-intensifying backdrop of global environmental change.

A fourth cluster of characteristics identified by Enríquez-de-Salamanca (Citation2018) is administrative manipulation of the EIA process and the use of confusing or complex information. This transpired in the Miramar case in two ways. First, administrative manipulation of the EIA process happened by dividing the resort site into two smaller land packages, in order to allow resort building construction to commence and to circumvent the need for a full-scale EIA (Chan Citation2013). Second, both administrative manipulation and the creation of confusion and complexity were apparent in the community engagement processes around the development. As outlined in Sections 5.2. and 5.3., consultations were held at short notice and with the requirement to register in advance to speak, and were held only in Mandarin. Whilst arguably an acceptable form of consultation under local EIA legislation, such actions may be considered administrative manipulation and creation of complexity if they make participation in the EIA process impossible to all but the most active and vocal members of the community, or to civil society groups from elsewhere in Taiwan with the political nous to know how to work within the constraints of an EIA process and/or generate controversy through, for instance, social media and coordinated protests. The contribution the Miramar case makes to Enriquez de Salamanca’s concerns over administrative manipulation of the EIA process, and the use of confusing or complex information, is that even if an EIA is conducted within a developer’s interpretation of the law (i.e. even if the use of outright false information, bribery and extortion are avoided), the outcome may not be consented to by communities and opponents if the consultation process is not perceived as open and fair or if it raises barriers to participation. This has of course been well covered in the EIA literature, both in Taiwan (e.g. Tu [Citation2010] on the Central Taiwan Science Park) and globally (e.g. Smart, Stojanovic, and Warren (Citation2014) on EIA processes for onshore wind on Scotland being viewed as ‘biased’ toward developers). However, in newer democracies and/or contexts where concern for due process is not so established, the Miramar case illustrates how the bare legal minimum for consultation in an EIA may not in itself be enough to build consent for the outcome.

Finally, there is little evidence of self-censorship (albeit because the local government – and thus the project promoter, regulator and competent authority – has come out strongly in favor of the development); of bribes and kickbacks; or of extortion. It is worth noting though that with the project effectively canceled, in an arbitration hearing in October 2020 Taitung County Government was ordered to pay NTD 629 million to buy the building back, with no immediate plans for its reuse – thereby having a direct negative effect on the local economy as a result of the development outcome.

The Miramar case also reveals an additional tactic deployed by the developer and EIA proponents which Enríquez-de-Salamanca (Citation2018) does not touch on so explicitly – discrediting evidence and testimony. As per Section 5.2., arguments against the developer grounded in local and indigenous understandings of the bay, or in concerns over the effects on future generations, did not appear to have been given consideration within the EIA process for the Miramar resort. The local government also described opponents’ arguments as being “emotional” or “irrational” and hence inappropriate for consideration in an EIA forum. Moreover, actions such as holding consultations in Mandarin (as opposed to traditional local languages), and the developer’s establishment of a website titled “Miramar Facts” (http://www.miramarfacts.com.tw, now offline) can all be seen as seeking to devalue and discredit certain kinds of argumentation in favor of seemingly objective “facts”. Such actions to devalue or discredit the contributions of participants in an EIA process may be considered a form of epistemic injustice (Fricker Citation2007) if they lead to people and perspectives being overlooked from processes of defining and understanding social problems on account of the identity of the speaker, or the language/type of knowledge they use to make their claims. Consideration of how to embed traditional, local and indigenous knowledge into environmental assessment processes is still emerging globally (see e.g. Eckert et al. (Citation2020) on the limitations of Canadian environmental assessment legislation to engage indigenous knowledge; and Sandham, Chabalala, and Spaling (Citation2019) on linking participatory rural appraisal on EIAs in South Africa). The Miramar findings hence illustrate that even if opportunities for participation in the EIA process are provided, these may be of limited value if they are not supported by measures to ensure contributors’ testimonies and knowledge are treated with credibility.

7. Conclusion

We started from the premise that the implementation and evaluation of an EIA is a social process intrinsically bound up with uneven power relations and limitations to what can be known with certainty, and that development-oriented proponents could seek to exploit the limitations of otherwise well-intentioned EIA regulations in order to engineer a desired outcome. Through assessment of the controversy around the EIA process for the Miramar Resort in Shanyuan Bay, Taitung County, Taiwan, we have sought to build on this extant literature by assessing an empirical case where the developer and local government appear to have worked together to circumvent an EIA process. Eastern Taiwan is perhaps typical of a number of emerging economy and new democracy contexts where socio-economic development imperatives and environmental goals have the potential to conflict with one another, and where local governments may ultimately be the people who have to balance these objectives through processes such as granting permission for new developments. However, our findings from Taitung County show that a drive for social and economic development in order to “level up” with the rest of the country can, if not managed sensitively, lead to a relationship of dependency with external investors and result in situations such as that in Miramar whereby local authorities appear to actively work with developers to circumvent environmental protection legislation. Indeed, the Miramar Resort is one of a number of tourist-oriented developments in Taitung County in recent years, leading to concerns over development fatigue and skepticism over the benefits to local communities (Indigenous Sight Citation2019). The responses from participants in our study suggest communities may not necessarily see economic and employment improvements as a fair tradeoff for culturally meaningful landscapes. Finally, whilst our findings are largely consistent with what has been written in extant research, a particularly notable finding is that as part of efforts to thwart due process within EIAs, proponents of developments may work to discredit the experiences or knowledge of other actors in the controversy, for instance by dismissing their concerns as “emotional” or irrational or by sidelining traditional, local and indigenous knowledge within the EIA process. Further research may hence wish to explore strategies for ensuring that different experiences and knowledge systems can not only participate, but are also recognized, within social and environmental impact assessments.

Acknowledgements

Leslie Mabon participated in the writing of this paper as part of his activities as a Future Earth Coasts Fellow.

Notes

1 Also quoted in Huang and Mabon (Citation2021).

2 Also quoted in Huang and Mabon (Citation2021).

References

- Baxter, J., and J. Eyles. 1997. “Evaluating Qualitative Research in Social Geography: Establishing ‘Rigour’ in Interview Analysis.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 22 (4): 505–525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-2754.1997.00505.x.

- Blake, D.J.H., and K. Barney. 2018. “Structural Injustice, Slow Violence? The Political Ecology of a ‘Best Practice’ Hydropower Dam in Lao PDR.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48 (5): 808–834. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2018.1482560.

- Blowers, A. 1999. “Nuclear Waste and Landscapes of Risk.” Landscape Research 24 (3): 241–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01426399908706562.

- Boeckmann, M. 2016. “Exploring the Health Context: A Qualitative Study of Local Heat and Climate Change Adaptation in Japan.” Geoforum 73, 1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.04.006

- Bradbury, J., K. Branch, J. Heerwagen, and E. Liebow. 1994. “Community Viewpoints of the Chemical Stockpile Disposal Program.” Summary Report and Eight Community Reports Prepared for the US Army and Science Applications International Corporation, Richland, WA: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

- Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods: 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Butler, R., and T. Hinch. 2006. Tourism and Indigenous People: Issues and Implications Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Cambrosio, A., and C. Limoges. 1991. “Controversies as Governing Processes in Technology Assessment.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 3 (4): 377–396. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09537329108524067.

- Cashmore, M. 2004. “The Role of Science in Environmental Impact Assessment: Process and Procedure versus Purpose in the Development of Theory.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 24 (4): 403–426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2003.12.002.

- Cashmore, M., and T. Richardson. 2013. “Power and Environmental Assessment: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 39: 1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2012.08.002.

- Cass, N., and G. Walker. 2009. “Emotion and Rationality: The Characterisation and Evaluation of Opposition to Renewable Energy Projects.” Emotion, Space and Society 2 (1): 62–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2009.05.006.

- Chan, S.K. 2013. “Discussion on Avoidance of BOT Project's EIA Procedure: Start from the Miramar Resort Case.” Taiwan Environmental and Land Law Journal 1 (5): 83–98. in Chinese)

- Chen, C. L. 2014. “Institutional Roles of Political Processes, Expert Governance, and Judicial Review in Environmental Impact Assessment: A Theoretical Framework and a Case Study of Taiwan.” Natural Resources Journal 54: 41–79.

- Childs, J. 2019. “Greening the Blue? Corporate Strategies for Legitimising Deep Sea Mining.” Political Geography 74: 102060. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102060.

- Cho, J., and E.-H. Lee. 2014. “Reducing Confusion about Grounded Theory and Qualitative Content Analysis: Similarities and Differences.” The Qualitative Report 19 (32): 1–20. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss32/2.

- Chou, K.-T., K. Hasegawa, D. Ku, and S.-F. Kao. 2020. Climate Change Governance in Asia. London: Routledge.

- Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. 2010. 2010 Population and Housing Census. Accessed April 7 2021. https://census.dgbas.gov.tw/PHC2010/english/rehome.htm.

- Eckert, L. E., N. Xemŧoltw–Claxton, C. Owens, A. Johnston, N. C. Ban, F. Moola, and C. T. Darimont. 2020. “Indigenous Knowledge and Federal Environmental Assessments in Canada: Applying Past Lessons to the 2019 Impact Assessment Act.” Facets 5 (1): 67–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2019-0039.

- EIA Act Article Five from Environmental Protection Administration. (2018). Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Taiwan) official website. Accessed October 16 2019. https://oaout.epa.gov.tw/law/LawContent.aspx?id=FL016247 (in Chinese)

- Enríquez-de-Salamanca, Á. 2018. “Stakeholders’ Manipulation of Environmental Impact Assessment.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 68: 10–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.10.003.

- Environmental Protection Administration. 2019. ‘Environmental Impact Assessment (環境影響評估)’ https://www.epa.gov.tw/eng/392EF735A15E6538

- Fan, M..F. 2006. “Nuclear Waste Facilities on Tribal Land: The Yami's Struggles for Environmental Justice.” Local Environment 11 (4): 433–444. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830600785589.

- Fan, M.-F., C.-M. Chiu, and L. Mabon. 2020. “Environmental Justice and the Politics of Pollution: The Case of the Formosa Ha Tinh Steel Pollution Incident in Vietnam.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848620973164.

- Fan, M. F. 2016. “Environmental Justice and the Politics of Risk: Water Resource Controversies in Taiwan.” Human Ecology 44 (4): 425–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-016-9844-7.

- Fricker, M. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grano, S.A. 2014. “Change and Continuities: Taiwan’s Post-2008 Environmental Policies.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 43 (3): 129–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261404300306.

- Grano, S.A. 2015. Environmental Governance in Taiwan: A New Generation of Activists and Stakeholders. London: Routledge.

- Ho, M.S. 2004. “Contested Governance between Politics and Professionalism in Taiwan.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 34 (2): 238–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00472330480000071.

- Ho, M. S. 2010. “Co-Opting Social Ties: How the Taiwanese Petrochemical Industry Neutralized Environmental Opposition’ Mobilization.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 15 (4): 447–463. doi:https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.15.4.n077415430371445.

- Hsiao, H.-H.M. 1990. “The Rise of Environmental Consciousness in Taiwan.” Impact Assessment 8 (1-2): 217–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07349165.1990.9726039.

- Hsiao, H.-H.M. 1999. “Environmental Movements in Taiwan.” in Asia’s Environmental Movements: Comparative Perspectives, edited by Y-S. F. Lee and A. Y So, 31–54. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, Inc.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S.E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis’ Qualitative.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Hsu, S.J., and S.F. Hsu. 2001. “The Research of Environmental Impact Assessment from the Viewpoint of Citizen Participation.” Journal of Taiwan Land Research 2: 101–130. (in Chinese)

- Huang, I.-M.P. 2014. “Rediscovering Local Environmentalism in Taiwan.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16 (4): 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2563.

- Huang, Y.-C., and L. Mabon. 2021. “Coastal Landscapes, Sustainable Consumption and Peripheral Communities: Evaluating the Miramar Resort Controversy in Shanyuan Bay, Taiwan.” Marine Policy 123: 104283. ; doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104283.

- Hwang, J.T. 2017. “Changing South Korean Water Policy after Political and Economic Liberalisation.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 47 (2): 225–246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1266014.

- Indigenous Sight. 2019. “When Indigenous Communities Meet Tourism: Those BOT Projects in Our Traditional Territories: Indigenous Sight.” Accessed April 7 2021 https://insight.ipcf.org.tw/en-US/article/124

- Johnson, T. 2014. “Good Governance for Environmental Protection in China: Instrumentation, Strategic Interactions and Unintended Consequences.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 44 (2): 241–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2013.870828.

- Karrasch, L., and T. Klenke. 2016. “Aligning Local Adaptive Land Use Management in Coastal Regions with European Policies on Climate Adaptation and Rural Development.” in European Rural Peripheries Revalued: Governance, Actors, Impacts, edited by U. Grabski-Kieron, I. Mose, A. Reichert-Schick, and A. Steinführer, 296–312. Munster: LIT Verlag.

- Kühn, M. 2015. “Peripheralization: Theoretical Concepts Explaining Socio-Spatial Inequalities.” European Planning Studies 23 (2): 367–378. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.862518.

- Lin, Y.Y. 2013. “Hua-Tung Pure Land, Beautiful Back Garden ‘Plant a Hope for the Land’.” ISBNet 179: 31–34. (in Chinese)

- Lyytimäki, J., and L. Peltonen. 2016. “Mining through Controversies: Public Perceptions and the Legitimacy of a Planned Gold Mine near a Tourist Destination.” Land Use Policy 54: 479–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.03.004.

- Mak, A.H.N. 2017. “Online Destination Image: Comparing National Tourism Organisations’ and Tourists' Perspectives.” Tourism Management 60: 280–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.012.

- Mayring, P. 2019. “Qualitative Content Analysis: Demarcation, Varieties, Developments.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 20 (3): 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3343.

- Mehnen, N., I. Mose, and D. Strijker. 2013. “The Delphi Method as a Useful Tool to Study Governance and Protected Areas?” Landscape Research 38 (5): 607–624. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2012.690862.

- Ministry of Interior Statistics 2021. Monthly Bulletin of Interior Statistics. Accessed April 7 2021 https://ws.moi.gov.tw/001/Upload/400/relfile/0/4413/fb872a90-4ab8-4752-bf7b-7bcd890da5f3/month/month_en.html.

- Miramar Resort. 2008. Miramar Resort Project Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). Miramar Resort Limited Company: Taipei.

- Miramar Resort. n.d. Illustration Meeting Documents of the Miramar Resort Project 2006 and 2007. Miramar Resort Limited Company: Taipei.

- Miramar Resort. 2019. ‘Miramar Facts: Official Website’ [online] Accessed October 16 2019 http://www.miramarfacts.com.tw/ (in Chinese)

- Moser, S. 2020. “New Cities: Engineering Social Exclusions.” One Earth 2 (2): 125–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.01.012.

- Nordberg, K., and P. Salmi. 2019. “Addressing the Gap between Participatory Ideals and the Reality of Environmental Management: The Case of the Cormorant Population in Finland.” Environmental Policy and Governance 29 (4): 251–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1850

- PeoPo Citizen Journalism. 2012. Accessed October 16, 2019 http://www.peopo.org/news/98877 (in Chinese)

- Puig, J., and A. Villarroya. 2013. “Ecological Quality Loss and Damage Compensation in Estuaries: Clues from a Lawsuit in the Basque Country, Spain.” Ocean & Coastal Management 71: 46–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.09.005.

- Sandham, L. A., J. J. Chabalala, and H. H. Spaling. 2019. “Participatory Rural Appraisal Approaches for Public Participation in EIA: Lessons from South Africa.” Land 8 (10): 150. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/land8100150.

- Smart, D. E., T. A. Stojanovic, and C. R. Warren. 2014. “Is EIA Part of the Wind Power Planning Problem?” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 49: 13–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2014.05.004.

- Smith, G. 2015. “Indigenous Activists Win Legal Battle against Luxury Resort Developer in Taiwan” Cultural Survival Accessed October 16 2019 https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/indigenous-activists-win-legal-battle-against-luxury-resort-developer-taiwan

- Spiegel, S. J. 2017. “EIAs, Power and Political Ecology: Situating Resource Struggles and the Techno-Politics of Small-Scale Mining.” Geoforum 87: 95–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.10.010.

- Tai, H. S., W. S. Kong, and C. W. Kou. 2012. “Environment Impact Assessment under Developmentalism and Neoliberalism: Rethinking the Case of Miramar Resort.” Paper presented at the 4th Annual Conference on Development Studies in Taiwan: Trans-X Risk and Justice, Taiwan. (in Chinese).

- Tai, H. S., W. S. Kong, and C. W. Kou. 2013. “The Miramar Resort Case: Controversy over the Design and Enforcement of Taiwan’s Environmental Impact Assessment.” Journal of National Development Studies 12 (2): 133–178. (In Chinese).

- Taitung County Government. 2018. “Introduction: Taitung Travel” Available at: Accessed October 16 2019 https://tour.taitung.gov.tw/en/discover/intro

- Taitung County Public Work Bureau 2012. Accessed October 16 2019 http://www.taitung.gov.tw/Publicwork/News_Content.aspx?n=E4FA0485B2A5071E&sms=E13057BB37942D3F&s=3F66F5AE0561EF79 (in Chinese)

- Tu, W. L. 2010. “Environmental Impact Assessment: Environmental Disputes over the 3rd Stage of Central Taiwan Science Park Development.” Journal of Public Administration 35: 29–60. (in Chinese)

- Tu, W. L. 2012. “Expert Meetings in the Environmental Impact Assessment Process: The Framed Expert’s Rationality’ Taiwan.” Journal of Democracy 9 (3): 119–155. in Chinese)

- UDN News. 2018. Accessed July 28, 2019 https://udn.com/news/story/7328/3279250 (In Chinese)

- Wei, B. R. 2018. “Against Opposition to Anti-Meiliwan.” in Resistance: Ten Environmental Movements from Streets to the Court, edited by Y. Y. Chang and C. Lee, 34–43. Taipei: Sharing. (In Chinese)

- Williams, J., and C.-Y. D. Chang. 2008. Taiwan’s Environmental Struggle: Toward a Green Silicon Island. London: Routledge

- Wong, W. M. N. 2017. “The Road to Environmental Participatory Governance in Taiwan: Collaboration and Challenges in Incineration and Municipal Waste Management.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 60 (10): 1726–1740. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2016.1251400.

- Yin, R. K. 1984. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. New York: Sage.