ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the socio-demographic attributes and political attitudes of protesters in Germany. In doing so, the paper studies participation at demonstrations, one of the key forms of non-electoral political participation in Germany and a central political arena in which to negotiate political and cultural conflicts. Methodologically, we draw on original data from nine protest surveys collected between 2003 and 2020. The demonstrations under scrutiny address a wide variety of issues such as peace, climate change, global justice, immigration, international trade and social policy. Analysing protesters’ profiles, we focus on differences both within and across demonstrations. We show that demonstrators’ socio-demographic and attitudinal characteristics diverge considerably across the surveyed demonstrations. In particular, we identify two clusters of demonstrations, differing most prominently regarding participants’ political trust, satisfaction with democracy, and perceptions of self-efficacy – the ‘disenchanted critics’ and the ‘confident critics’. Based on a regression analysis across all nine demonstrations, we further show that the distinction of these two demonstration clusters is not the result of the presence or absence of certain groups of demonstrators.

Introduction

At regular intervals, political scientists lament the loss of legitimacy of political systems and their democratic institutions (Habermas Citation1973; Crouch Citation2004). In Germany, as in many established democracies (Catterberg and Moreno Citation2005), general population surveys show declining trust in political institutions between the 1980s and mid-2000s (Hadjar and Köthemann Citation2014). In line with this, the overall increase of protest activities over the last decades (Dalton, van Sickle, and Weldon Citation2010) as well as recent protests in Germany (and elsewhere) both from the left and the right have been interpreted as visible signs of this crisis of legitimacy and a growing distance from established political institutions. The Occupy Movement’s claim to recapture democracy from political and economic elites was a radical democratic expression of political distrust from the left (Gerbaudo Citation2017). Mass mobilisations against transnational trade agreements like TTIP or CETA (see Rone and Gheyle, in this special issue) and against the G20-summit in Hamburg questioned the legitimacy of decision-making at the national and international level. On the political right, Pegida and other anti-refugee protests expressed fundamental distrust in political elites who were framed as agents of globalist interests. And most recently, a series of protests against Covid-19 related restrictions spread anti-elitist conspiracy narratives and signified a widespread alienation from political institutions among segments of the German population.

But are demonstrations really a sign of a growing distance to the political system and decreasing trust in democratic institutions? At first glance the relationship seems obvious: demonstrators are necessarily critical towards ruling political elites – otherwise they would not protest – and, indeed, studies often associate participants in demonstrations with lower levels of political trust when compared to the general population (e.g. Hooghe and Marien Citation2013). But on the other hand, protest itself is an active expression of political participation, and protesters often highly value democratic procedures and have developed numerous democratic innovations (Della Porta Citation2009; Flesher Fominaya Citation2020).

In our article, we take a closer look at this relationship between protest participation and political disaffection. Based on an evaluation of data from nine protest surveys conducted between 2003 and 2020, we show that participants in some demonstrations display surprisingly high levels of political trust – sometimes even higher than those of the average citizen. Nevertheless, there are protest participants who fulfil the image of disgruntled citizens. Their participation in protests can be seen as an expression of democratic engagement but at the same time, these demonstrators deeply distrust politicians and established political institutions.

Based on our data, we show that at some demonstrations these attitudes are dominant. This group of demonstrations differs substantially from a second, larger group of demonstrations where high levels of trust in political institutions prevail. We therefore distinguish between demonstrations of the ‘disenchanted critics’ and demonstrations of the ‘confident critics’. Contributing to recent studies on diverse levels of trust among protesters (van Stekelenburg and Klandermans Citation2018; Christensen Citation2016; Andretta, Bosi, and Della Porta Citation2015) our study hence shows that trust levels not only differ between individuals, but between different kinds of demonstrations.

To shed more light on the seemingly ambiguous role of political mistrust in protest participation, we first systematically explore the differences between these two clusters of demonstrations. In a second step, we dig a bit deeper and examine whether these differences are more likely the result of the over-representation of certain groups of protesters at some of the demonstrations or whether they indicate more far-reaching differences. Third, we contextualise the cluster of the ‘disenchanted critics’ by adding qualitative insights from open questions about the protesters’ motivation. Finally, we draw conclusions on our central findings and on the distinctiveness of both clusters.

Who Protests?

Political participation can take a variety of forms. For a long time, scholars distinguished between ‘conventional’ and ‘unconventional’ forms of political participation (Barnes and Kaase, Citation1979) marking their different degrees of ‘normalcy’. With the considerable growth of ‘unconventional’ forms, however, this distinction no longer makes much sense. Instead, scholars have suggested a distinction between institutional(ised) or formal and non-institutional(ised) or informal forms of participation (see e.g. Hooghe and Marien Citation2013). While the former refer to ‘acts directly related to the institutional process’ which are shaped by political elites and political parties, the latter ‘have no direct relation with the electoral process or the functioning of the political institutions’ (Hooghe and Marien Citation2013, 134). Informal forms of participation involve signing petitions, joining boycotts, as well as taking part in demonstrations and are sometimes summarily referred to as ‘protest activities’ (see Saunders Citation2014). In the following review of the literature, we will focus instead on ‘protest’ in a narrower sense: we use it to refer to a particular form of non-institutionalised participation, namely the participation in public demonstrations and marches. The profile, commitment and motivation of participants in such demonstrations and marches differ from participants in other protest activities and the former usually distrust political institutions more than the latter (Saunders Citation2014), making them particularly interesting for our analysis.

General Characteristics of Protest Participants

Protests are an essential pillar of political participation in democracies (e.g. della Porta Citation2013; Norris Citation2011). A considerable body of research has emerged exploring dynamics of street mobilisations and the individual characteristics of protesters. These studies show that protest participants tend to have a specific profile with respect to socio-demographic characteristics and political attitudes. This profile differs, both, from the average population as well as from people taking part in other forms of political participation. With respect to socio-demographic characteristics studies have shown that compared to the population average, protesters tend to have higher levels of education (e.g. van Aelst and Walgrave Citation2001; Dalton, van Sickle, and Weldon Citation2010) and income (e.g. Kurer et al. Citation2019), and they tend to be younger. With respect to political orientation and attitudes, cross-national studies reveal that compared to the population average, protest participants in Western Europe tend to be more left-oriented (e.g. Torcal, Rodon, and Hierro Citation2016; Dalton, van Sickle, and Weldon Citation2010), they are more likely to share post-materialist values (Inglehart Citation1990), have a stronger political interest (Saunders Citation2014) and have higher levels of perceived political self-efficacy – believing that their actions can influence political decision making (e.g. Klandermans Citation1984; Saunders et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, comparative cross-country studies show that while people participating in demonstrations do not tend to participate less than non-demonstrators in institutionalised forms of participation such as in elections, they do tend to have less trust in political institutions than the average population (Dalton, van Sickle, and Weldon Citation2010; Braun and Hutter Citation2016; Saunders Citation2014). In this vein, studies have consistently found that the lower a person’s political trust, the higher the probability that she/he will engage in non-institutional forms of participation (e.g. Kaase Citation1999; Hooghe and Marien Citation2013). This effect is particularly pronounced for participation in protests (Kaase Citation1999; Hooghe and Marien Citation2013). By contrast, the effect is the reverse for institutionalised forms of participation. The more people trust political institutions, the more they tend to use these forms of action, including voting (Dalton Citation2004; on Germany see: Hadjar and Köthemann Citation2014), especially if they have high levels of perceived self-efficacy (Hooghe and Marien Citation2013).

But, of course, protesters also differ in their political attitudes. In this vein, some recent studies have shown that political trust varies among protesters depending on their socio-demographic profiles, political resources and levels of political efficacy (van Stekelenburg and Klandermans Citation2018; Christensen Citation2016; Andretta, Bosi, and Della Porta Citation2015). Recent studies have also identified differences between more experienced protesters and newcomers with regard to their political attitudes. In a comparative study about May Day and climate change protests across Europe, Saunders et al. (Citation2012) show that participants with much prior protest experience (stalwarts) are more likely to be mobilised through closed organisational communication channels, to hold left-wing views, and to be politically engaged. They also tend to be less satisfied with democracy compared to protesters with less or none prior protest experience. Similarly, Sabucedo et al. (Citation2017) show for anti-austerity protests in Spain in 2010 and 2011 that regular protesters reveal lower levels of trust in political institutions and less satisfaction with democracy.

Context-Specific Characteristics of Protest Participants

In addition to individual-level factors, however, the context also affects protest participation; frequency, size and nature of protests depends on the interaction of individual-level factors with contextual factors (van Stekelenburg et al. Citation2012; Kurer et al. Citation2019; Dalton, van Sickle, and Weldon Citation2010). First, protests and their participants differ across countries. Studies have examined the effect of countries’ economic development (e.g. Kern, Marien, and Hooghe Citation2015), political opportunity structures (e.g. Dalton, van Sickle, and Weldon Citation2010) or cleavage structure (e.g. Kriesi et al. Citation2012; Hutter 2014; Damen and van Stekelenburg Citation2019) on protest issues and participants. For Germany, Lahusen and Bleckmann (Citation2015) argue that some of the general determinants of protest participation identified in comparative studies are less relevant here or change over time. Based on an evaluation of general population surveys they show that, as expected, in the 1970s younger people with a university degree, post-materialist values, high political interest and active organisation membership were most likely to participate in protests. As in other countries, men were more likely to protest than women at that time and the socio-economic status as well as trust in political institutions did not seem to have much impact on protest participation. The picture changes in general population surveys conducted in 2008 when age, gender, university degree and active organisational membership cease to have a decisive impact on protest participation, reflecting a growing diversification of protest (ibid.).

Beyond country-specific contexts, scholars highlight protesters’ diverging characteristics in the context of different types of demonstrations. A growing body of research points out that different kinds of demonstrations draw different crowds, depending on the issues they address and the type of organisations that mobilise. The gender ratio, for example, strongly depends on the protest issue (van Aelst and Walgrave Citation2001; Fillieule Citation1997). Other socio-demographic characteristics also diverge between different kinds of protests. Norris, Walgrave, and van Aelst (Citation2006) show that participants at demonstrations of the ‘new left’ in Belgium, including global justice and anti-racism protests, are younger, better educated and more politically engaged than participants at demonstrations of the ‘old left’ about social security and education. Similarly, Damen and van Stekelenburg (Citation2019) show in their comparative study of protests in four European countries between 2009 and 2013 that while higher professionals form the largest groups in all types of demonstrations, members of the working class are more present in demonstrations that focus on ‘bread and butter issues’ (in particular anti-austerity) and tend to be more left-wing than participants in demonstrations concerned with social-cultural issues. Furthermore, various studies highlight differences between left-wing and right-wing protests. Norris, Walgrave, and van Aelst (Citation2006) for example show that participants in demonstrations of the (old) left in Belgium show a higher satisfaction with democracy than participants in demonstrations of the (new) right.

This draws attention to the fact that protest participants may differ considerably between different kinds of protests. Contributing to this literature, the following analysis introduces the distinction between protests of the ‘disenchanted critics’ and of the ‘confident critics’. In contrast to existing distinctions that cluster demonstration types on the basis of protest issues or protesters’ political orientation, our distinction is based on participants attitudes and the diverging foundation of their protest and criticism.

Data and Methods

The Advantages of Protest Surveys

We compare the social-demographic and political profile of protesters across different types of protests in Germany based on protest surveys collected between 2003 and 2020. Such data offers certain advantages over data retrieved from alternative sources that are common in social movement research, such as general population surveys and protest event analyses. Many of the above cited studies on the socio-demographic characteristics and political attitudes of protest participants rely on general population surveys – such as the European Value Survey (e.g. Hooghe and Marien Citation2013).Footnote1 Based on newspaper reports, protest event analysis has often been employed to systematically map the frequency and size of demonstrations and their main goals and organisers (Koopmans and Rucht Citation2002; Hutter 2014). Both sources of data come with limitations (see also van Aelst and Walgrave Citation2001). Protest event analyses only provide superficial (if any) insights about who participates in a given demonstration and about the individual reasons for participation. General population surveys, in contrast, do provide individual-level insights, but information about the context of the protest participation, such as the issue or the date of the protest an individual attended is not available. Surveying protesters on the spot allows for link formation between individuals and protest issues. In this vein, protest surveys are snapshots of conflicts. To explore the particular features of protesters in Germany, we introduce a dataset that merges the responses of 5,460 individuals surveyed at nine street demonstrations from 2003 to 2020. The earlier surveys from 2003 to 2010 were conducted by the research group on political mobilisation at the Berlin Social Science Centre led by Dieter Rucht, the more recent surveys were organised by members of the Institute for the Study of Protests and Social Movements (ipb).Footnote2 Our analysis includes surveys from diverse protests that address a wide range of issues including: the war in Iraq in 2003, the restructuring of social welfare and labour market policy in 2004, the construction of a new train station in Stuttgart in 2010, the Ukraine war in 2014, migration in 2015, international trade agreements TTIP and CETA in 2015, the G20 meeting in 2017, the climate crisis in 2019 and agricultural reform in 2020 (for details see Appendix).

In order to contrast the demonstrators’ profiles with the average population in Germany, we compare the protest survey data with the two most recent waves of the German general population survey ALLBUS that contain questions about protest participation, ALLBUS 2008 (GESIS Citation2015) and ALLBUS 2018 (GESIS Citation2019).

Methodology of Protest Surveys

Within a decade, protest surveys have become an established method to explore the composition and motivation of people who join a demonstration (Fillieule and Blanchard Citation2010; Klandermans Citation2013; Della Porta and Andretta Citation2014). While most surveys emerged as side projects without proper funding, the international research project ‘Caught in the Act of Protest. Contextualising Contestation’ laid the groundwork for a rigorous methodological standard (van Stekelenburg et al. Citation2012). There are three main ways to administer protest surveys, namely (1) handing out paper questionnaires and a prepaid return envelope (2) distributing leaflets with a link to an online survey, and (3) face-to-face interviews (recently aided by tablets with a survey app) recording replies on the spot. All three methods come with specific biases and shortcomings. Rüdig (Citation2010), for instance, finds that older, female, and better educated protesters are more likely to respond when provided a paper questionnaire. By contrast, online surveys are less accessible for older protesters. In our surveys, we used either paper questionnaires or online surveys (see overview in ), for the G20 protests, we combined both methods.

Table 1. Surveyed demonstrations.

The central challenge of surveying a crowd is to obtain an approximately representative sample. With this in mind, scholars aim to realise a random sample of the people who participate in a demonstration. However, the most sophisticated method is limited, if protesters do not want to cooperate. This problem was minor or non-existent in most surveys. But relevant parts of the Pegida demonstration refused to take part in the survey, namely the hardcore activists at the head of the demonstration, groups of hooligans, and Neo-Nazis. (Daphi et al. Citation2015, 8-10; Teune and Ullrich Citation2015). The most probable reason for this refusal was these groups’ lack of trust in scientific research.Footnote3 While we are confident that we were able to realise a random sample in all other demonstrations, the Pegida sample represents only the moderate parts of the demonstration, rather than the demonstration as a whole.

Analysis

Who are the people who take to the streets in Germany? In this section, we compare central characteristics of the demonstrators who participated in the protests we surveyed between 2003 and 2020. First, we focus on socio-demographic features, political orientation, and protest experience. The comparison shows remarkable differences across the nine demonstrations. While existing studies have identified important predictors that distinguish protesters from non-protester, protest is heterogeneous in itself and different demonstrations attract different groups of demonstrators. Second, we argue that beyond these basic differences, the demonstrations in our sample can be separated into two different clusters when it comes to political perceptions and attitudes. The demonstration cluster of the ‘disenchanted critics’ strongly differs from that of the ‘confident critics’ in terms of trust in political institutions, satisfaction in democracy and perceptions of self-efficacy. While, almost per definition, all those taking to the street share a sense of opposition against the government and other political institutions, the attitudinal background of this opposition differs between (often issue-specific) criticism based on generalised trust in one cluster, and diffuse resistance on the basis of detachment from institutionalised politics in the other.

Different Demonstrations, Different Demonstrators

A closer look at our nine demonstrations shows that they attract different demonstrators, supporting the growing body of studies claiming that the composition of those who turn up on the streets depends on issue, context, and demonstration type.

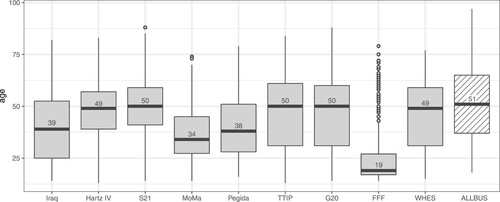

First, we see remarkable differences in the age structure with a median ranging from 19 years at the Fridays for Future demonstration to 50 years at the Stuttgart 21 protests (see ). While the median age at some demonstrations (Hartz IV), Stuttgart 21 (S21), TTIP, G20, and the agriculture protests (WHES) is very close to the population average, the protests against the war in Iraq, the peace Vigils (MoMa), Pegida, and, most prominently, the Fridays for Future demonstration draw substantially younger crowds.

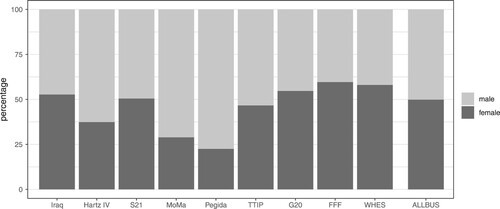

Second, the gender distribution at the surveyed demonstrations shows marked differences, too (see ). The demonstrations dominated by men are the Hartz IV protests, the Peace Vigils, and the Pegida demonstration, where male participation ranges between two thirds to three quarters. Other demonstrations, and especially the more recent ones, such as the climate strikes (59 per cent) and the agriculture protests (58 per cent) bring out a clear majority of female participants.

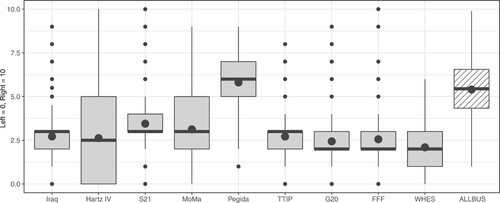

Third, when comparing the political orientation among our set of demonstrations the pattern is less diverse (see ). The majority displays a left-wing orientation with WHES showing the leftmost profile. Only Pegida protesters position themselves more to the political right and closer to the population average.Footnote4

Fourth, participants in the demonstrations in our sample show a broad range in terms of protest experience. While the Fridays for Future demonstrations, the S21 protests, the Peace Vigils and Pegida attract many first-timers, other demonstrations are strongly dominated by experienced protesters (numbers not displayed). Those who state that they have not participated in another demonstration within the last 12 months range from 65 per cent (Pegida) and 46 per cent (S21) to only three per cent at the WHES demonstration and eight per cent at the G20-protests.

Disenchanted Critics vs. Confident Critics

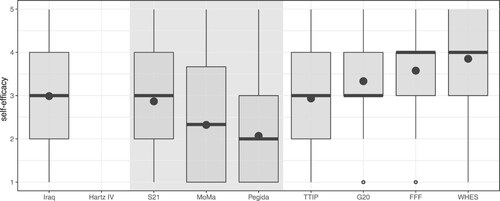

As we will demonstrate in this section by looking at demonstrators’ levels of political trust, satisfaction with democracy and perception of self-efficacy, the nine demonstrations cluster into two distinct groups. We suggest calling these groups the ‘disenchanted critics’ and the ‘confident critics’. The cluster of the ‘disenchanted critics’ encompasses the Pegida demonstration, the Peace Vigils, and the protests in Stuttgart. These demonstrations addressed diverse issues – ranging from Pegida’s racist protests against the ‘Islamisation of the occident’ to the protests for peace in Ukraine and the locally specific protests in Stuttgart against the city’s new train station. Their overall ideological orientation also diverges, with Pegida demonstrators largely identifying as centre-right and the Peace Vigils and Stuttgart 21 protests with a more mixed, centre-left profile. Despite these differences, these three protests share several features that clearly distinguish them from the other demonstrations in our sample. The demonstrators of the ‘disenchanted critics’ are (1) much less satisfied with how democracy works than other demonstrators, (2) participants in these three demonstrations have considerably lower levels of trust in key political institutions, and (3) their perceptions of political self-efficacy are considerably lower (see ).

Table 2. Overview of two demonstration clusters.

The cluster of the ‘confident critics’ encompasses five demonstrations in our sample: those against the war in Iraq and the G20 meeting, the broad mobilisation against the TTIP/CETA agreements, the climate protests, and the demonstration for sustainable agriculture.Footnote5 While being very diverse in their central claims and topics, they all share a widespread satisfaction with the existing state of democracy, high levels of trust in key political institutions that often even exceed the population-average and – compared to their disaffected peers – a stronger self-confidence that their protest can make an impact.

The distinction between these two clusters points to different perspectives on the state and different attitudinal bases of protest and opposition. In the first cluster, protest goes along with a general distrust in ‘the state’ and/or ‘the elite’. In the second cluster, protesters appreciate the fact that they live in a democracy, however flawed it might be. In what follows, we trace these two clusters – the ‘disenchanted critics’ and the ‘confident critics’ – in our empirical data, before further substantiating this distinction.

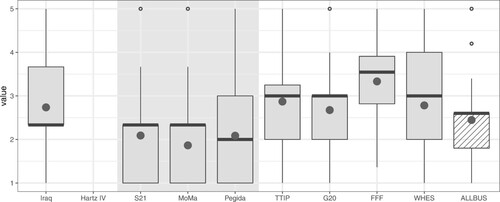

First, the comparison of democratic satisfaction among demonstrators reveals striking differences between both clusters. The question in all surveys was not about democracy as an abstract idea but rather about the actual working of democracy in Germany. And it is thus quite remarkable that satisfaction with democracy among demonstrators in five out of eight demonstrations is even higher than satisfaction levels among the general population. The high levels of democratic satisfaction among participants of the TTIP/CETA and G20 demonstrations are particularly noteworthy given that they were directly based on doubts about the democratic legitimacy of these institutions. Among respondents at the TTIP/CETA demonstration, no more than 7.5 per cent said they were not (or not at all) satisfied with the state of democracy in Germany. And in the light of the media’s widespread portrayal of G20 demonstrators as a threat (Sommer and Teune Citation2019), the comparatively high level of trust among them is even more astonishing.Footnote6 This is in stark contrast with the second cluster of ‘disenchanted critics’. For the S21, the Peace Vigils and Pegida protests, satisfaction with democracy is below that of the average population and much lower than in the first cluster (). 35 per cent of the S21 participants, 46 per cent of the Peace Vigil participants and 28 per cent of the Pegida protesters stated that they were not at all satisfied with how democracy works in Germany. This marked difference between these two clusters of demonstrations cannot be explained by political orientation alone. S21 demonstrators mainly identify as left-wing as do the majority of those who answered this question at the Peace Vigils (see , above).

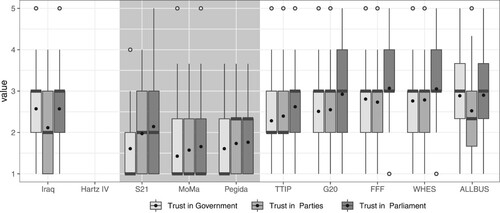

Second, a comparison of respondents’ trust in key political institutions (see ) confirms the cluster distinction. Again, the ‘confident critics’ show on average higher levels of trust in political parties, the government and the parliament than the demonstrators from the ‘disenchanted critics’ cluster. Their trust in parties and parliament even exceeds the trust levels of the general population. Given that many of these protests specifically mobilised against government policies, it is hardly surprising that trust in the government is slightly lower than among the general population. Interestingly, WHES demonstrators are not only the most leftist, but also among those with the strongest confidence in the government with roughly 22 per cent (largely) trusting those in power. Average trust levels among participants of the climate strikes are even higher which is astonishing given the movements’ central framing that stresses the government’s responsibility for insufficient climate policies. In particular, levels of trust in parliament and in political parties above population average indicate that these demonstrators are discontent with specific political decisions but support the democratic system in Germany and its institutions.

Figure 5. Trust in political institutions. Notes: The demonstration cluster of the ‘disenchanted critics’ is highlighted with a grey background. The levels of trust for the Pegida demonstrations and Peace Vigils are slightly overvalued as questionnaires at these demonstrations did not include the option ‘partly trust’ – in contrast to the other demonstrations.

The ‘disenchanted critics’ show a very different pattern. Trust levels in all three institutions are considerably lower than in the first cluster. The distinction is most clearly visible for the parliament. In all three demonstrations, less than five per cent state that they trust or partly trust the parliament compared to an average of 23.4 per cent in the other cluster. This mistrust in the parliament, in particular, indicates that among participants at these demonstrations, there is something more at play than an issue-specific critique of political decision-makers or government policies.

When it comes to trust in the EU, we see a similar pattern with seven per cent on average among the ‘disenchanted critics’ and almost 28 per cent trusting or largely trusting the EU among ‘confident critics’ (not displayed). The gap for trust in the media is equally large with 21 percentage points separating those in the disenchanted cluster (5.6 per cent) from those demonstrations clustered as ‘confident critics’ (26.5 per cent).

This picture changes when we turn to trust in the police, where levels of trust are highest among Pegida demonstrators with 90 per cent indicating that they rather trust than mistrust the police, followed by Fridays for Future, TTIP/CETA protesters and participants of the Peace Vigils. Trust in the police is considerably lower among those demonstrating against G20 and S21. Given that participants in these two protest events received the invitation to participate in the surveys under the immediate impression of confrontations with the police (see below), we suspect that trust in the police is more situational and, hence, we argue that the findings do not invalidate the overall cluster distinction. All in all, our distinction of two demonstration clusters with strikingly different attitudes towards key political institutions holds for all variables, with the partial exception of the police.

Third, we find relevant differences between the two clusters of demonstrations with regards to participants’ levels of perceived self-efficacy (). For all demonstrations (apart from the Hartz IV protests), we asked the participants to what extent they thought that their engagement could have an impact on politics in Germany.Footnote7 Also in this regard, the separation into two clusters is consistent. Among WHES demonstrators, almost two thirds were confident that their engagement could make a difference. Also among FFF (51 per cent) and G20 protesters (40 per cent) many agreed or largely agreed to this statement. In contrast, at the Peace Vigils and the Pegida protest perceived self-efficacy ranges only between ten per cent (Pegida) and 25 per cent (MoMa).

Overall, the comparison of political perceptions and attitudes shows the existence of two different clusters of demonstrations – the ‘disenchanted critics’ and the ‘confident critics’. Beyond the overall heterogeneity in terms of socio-demographic characteristics both clusters are opposed to each other while showing rather coherent patterns within each respective cluster. The overall ideological orientation crosses this cluster distinction – with Pegida demonstrators largely identifying as centre-right while the Stuttgart 21 protests reveal a clear centre-left profile and the Peace Vigils being largely left, with more variation (see ). The ‘disenchanted critics’ are much less satisfied with how democracy works when compared to the ‘confident critics’, they show considerably lower levels of trust in key political institutions including the parliament and government, the EU and political parties, and they have much lower perceptions of political self-efficacy.

Distinct Demonstration Clusters or Different Social Groups?

The two clusters of demonstrations could be the result of two social processes. On the one hand, the differences may be due to the dominance of certain social groups of demonstrators at each cluster. The boxplots above clearly show that levels of trust in political institutions and satisfaction with democracy vary significantly between individual demonstrators at each demonstration. The disenchanted cluster may thus be the consequence of an over-representation of the less trusting and less satisfied demonstrators. If this is true and differences between demonstrations are mainly the result of the presence or absence of certain groups of demonstrators, then our data should show stable correlations between individual characteristics of demonstrators and levels of trust and satisfaction with democracy. Existing research on individual determinants of political trust and satisfaction with democracy show that age, gender and education correlate with levels of political trust and satisfaction with democracy. In a cross-national study, Dassonneville and McAllister (Citation2020) show that female, older, leftist, or less educated citizens are less satisfied with democracy. Schnaudt (Citation2020) finds with respect to Germany that women have higher levels of trust in representative democratic institutions than men. In line with this research, we should therefore see similar and stable correlations between satisfaction with democracy and political trust on the one hand and gender, age cohort, left-right-placement and education on the other across all our demonstrations. Furthermore, studies about protest participants’ profiles discussed in the literature review suggest that protesters with less prior protest experience tend to have higher levels of satisfaction with democracy and political trust (Saunders et al. Citation2012; Sabucedo et al. Citation2017) and participants with low political trust tend to have lower levels of education (van Stekelenburg and Klandermans Citation2018).

However, if the clusters are not the result of the over- or underrepresentation of certain socio-demographic groups, we should see different correlations between individual-level socio-demographic variables and levels of trust and democratic satisfaction in both clusters. This would then point to more profound differences between the two clusters.

In order to test this, we conducted multiple linear regression analyses for two different dependent variables that figured prominently in the inter-demonstration variations: satisfaction with democracy and trust in government. Each model tests the correlation between these dependent variables and six independent variables that potentially define groups of demonstrators and affect levels of trust and satisfaction with the political system: (1) Age, (2) Gender, (3) Education, (4) Left-Right-Position (see Dassonneville and McAllister Citation2020; Schnaudt 2020), (5) Protest Experience, and (6) Organisational Membership (see Saunders et al. Citation2012).

Our goal here is not to test specific hypotheses; we are rather interested in exploring whether any (or all) of these independent variables are consistently correlated to higher or lower levels of institutional trust and satisfaction with democracy. summarises the two regression models (see details in Appendix). It lists for each demonstration and both dependent variables only the statistically significant factors. The table thus reveals the similarities and differences between demonstrations regarding possible explanatory variables for different levels of satisfaction with democracy and political trust within each demonstration. The entry ‘Gender (+)’ e.g. means that switching from male (0) to female (1) statistically significantly increases the level of trust in the respective demonstration or that female protesters show higher level of trust than male protesters.

Overall, the regression analysis () demonstrates that there are no stable correlations between satisfaction with democracy and political trust on the one hand and gender, age cohort, left-right-placement, education, and prior protest experience on the other. This suggests that the difference between the ‘disenchanted critics’ and the ‘confident critics’ is not the result of the presence or absence of clearly identifiable social groups at the respective demonstrations. The only independent variable that consistently correlates with levels of trust and satisfaction with democracy is the placement on the left-right axis, and it only does so at the demonstrations of the ‘confident critics’ and at the Stuttgart 21 protest. The positive, significant correlation means that higher levels on the scale (i.e. a less radical left position) correspond to higher levels of satisfaction with democracy or trust in government. For the Peace Vigils and the Pegida protests this correlation is not present. At these demonstrations, levels of trust in the government and satisfaction with democracy are low, regardless of the political position of the demonstrators.

Table 3. Overview of linear regression models.

For the other independent variables, we find significant correlations only for some demonstrations. In two cases (Iraq War and FFF) women are more satisfied with democracy than men – as existing research suggests – and in three other demonstrations (S21, TTIP, and G20) women show higher levels of trust in the government than men. Only among Pegida protesters do women trust the government less than men. Age does not play any role for satisfaction with democracy and trust in government. The notable exception is G20 where age is negatively correlated with satisfaction with democracy – contrary to existing studies – and trust in the government; mistrust thus increases with age among the G20-protesters.

At two demonstrations (S21 and G20) higher levels of education go along with higher levels of trust and satisfaction with democracy. For the other demonstrations, education does not have a significant effect. Similarly, organisational membership and protest experience are only significant for some demonstrations.

The regression results thus show that adding more demonstrators who position themselves towards the middle or the right of the political spectrum and more women would not raise levels of satisfaction with democracy or political trust at the Peace Vigils or the Pegida protests. The clusters therefore do not seem to be the result of the presence or absence of certain groups of demonstrators. The results also show that among the disenchanted critics, Stuttgart 21 is special: Here the presence of more women and demonstrators who position themselves in the political centre would, indeed, have raised levels of trust. The Stuttgart 21 protests are thus structurally more similar to the cluster of the ‘confident critics’ than to the ‘disenchanted critics’.

Contextualising the Disenchanted Critics

As the analysis above shows, the Stuttgart 21 protests differ in some respects from the other protests of the ‘disenchanted critics’ cluster. Hence, a closer look at the ‘disenchanted critics’ is worthwhile, putting the quantitative findings in perspective. The low level of trust in the police at the demonstrations against Stuttgart 21 and G20 is a case in point as they demonstrate the extent to which survey answers depend on the very specific dynamic of the situation: In contrast to other surveyed demonstrations, the surveys at these two demonstrations were set in close proximity to drastic violent encounters of protesters and the police. The strikingly different results underline both the limits of the method of protest surveys in a politically loaded setting and the influence of situational factors on the results (see Teune and Ullrich Citation2015).

Such context specific factors also need to be taken into consideration when taking a closer look at the different protests within the ‘disenchanted critics’ cluster. At first glance, the proximity of respondents protesting the Stuttgart 21 project on the one side and those at the Peace Vigils and at the Pegida protests on the other side is rather surprising. Akin to events in the other cluster, the Stuttgart 21 protests had been organised by a long-standing coalition of environmental organisations, citizens’ initiatives, and parties of the left. With the notable exception of a sizable conservative contingent (which would suggest higher levels of trust in democratic institutions), the protests also matched the demographics of the usual suspects: well-educated and centre-left. To understand the low level of trust and the sceptical evaluation of democracy in Germany, open questions about the respondents’ motivation provide valuable insights into their thinking. What follows falls short of a systematic qualitative analysis. It is rather a glimpse into reasons for people to join the protests and the differences and similarities that can be found within the cluster of the ‘disenchanted critics’.

All protests in this cluster are part of a series of events. The Peace Vigils and Pegida initially provided an opportunity to raise a plethora of different concerns that were bound by a general discomfort with how things were going. At the Peace Vigils, respondents hoped to contribute to a more harmonic world, they wanted to foster alternatives, and to express their general opposition to the economic and monetary system. At the Pegida protests, the fear of ‘Islamisation’ was dominant, but respondents also claimed that their pensions were unjust, they wished for peace in Europe and wanted to promote referenda as a form of direct democracy. At both demonstrations, participants were enraged by the media coverage of earlier protests, which highlighted antisemitism, racism, and the presence of organised Neo-Nazis. Thus, a general feeling of being misrepresented by the ‘gleichgeschaltete Presse’ (media forced into line) acting in unison with a sinister government fuelled more distrust. One respondent at the Peace Vigils summed up their motivation as follows: ‘Abolition of the corrupt system in which money rules and the media manipulates the people’. When it comes to democratic processes and institutions, the critique at both rallies is remarkably abstract and far-reaching. Journalists and elected officials are considered as part of a foul ‘system’. One respondent at the Pegida rally sees the need to ‘educate citizens that we have a soft dictatorship and not a democracy’.

The trajectory of disenchantment is different for the S21 protest as it draws on participants’ concrete prior disappointments in making themselves heard. Opponents of the Stuttgart 21 project had employed various ways to voice their dissent, most notably the collection of over 60,000 signatures for a referendum to force the city to withdraw from the project. After the referendum was rejected, the conflict culminated in a series of massive protests. The series peaked with the violent removal of protesters trying to stop the felling of old trees. Over the years, protesters experienced project planners and government officials as not responsive despite material concerns over Stuttgart 21. Also, in their view, local media neglected their control function. This process of frustration and alienation is highly visible in the ways respondents describe their motivation. One protester writes: ‘At first, I was concerned with preventing the project S21. Increasingly, however, it is also fundamentally about improving the participation of the population in certain decisions’. While the background for disenchantment with democracy differs, the criticism raised on occasion of Stuttgart 21 shows some overlap with the frames used at Pegida and Peace Vigils. Several respondents describe the situation as a ‘temporary dictatorship’, ‘the end of democracy’ or ‘GDR 2.0’.

Conclusion

Analysing the socio-demographic and attitudinal profile of protesters across a variety of protests in Germany, this paper firstly showed that demonstrators’ profiles diverge considerably, with regards to participants’ age, gender, left-right orientation and protest experience. Beyond such overall fluctuation, we demonstrated, secondly, that some differences between the protests are more systematic: In particular, we identified structural differences between two clusters of demonstration. The demonstrations of the ‘disenchanted critics’ diverge from those of the ‘confident critics’ with respect to their considerably lower levels of political trust, satisfaction with democracy and perceptions of self-efficacy. We substantiated this finding with regression analysies to check whether different levels of trust and satisfaction with democracy may be the result of over- or underrepresentation of specific socio-demographic groups at the different clusters of protests. Across all analysed demonstrations, participants’ political trust and satisfaction with democracy only consistently correlate with their left-right orientation, and this only in the ‘conficent critics‘ cluster. This suggests that the differences we identified between the ‘disenchanted critics’ and the ‘confident critics’ are not the result of the presence or absence of certain groups of demonstrators and thus these inter-demonstration differences mark indeed different types of protests.

Our work contributes to existing research and goes beyond existing knowledge in at least three ways. First, the two clusters of demonstrations we identify add to research on distinct types of protests and their diverse participants’ profiles that had largely focused on differences in issues, organisational structures and left-right orientation of protests. Our analysis draws attention to differences with regard to trust in democratic institutions and the evaluation of democratic performance. In fact, as the two clusters we identify reveal diverse ideological profiles, our distinction does not correspond with the often employed left-right differentiation. This is a pattern also other studies of protests in Germany confirm. A survey among the 2012 Occupy protests in Germany (Décieux and Nachtwey Citation2014) shows that these left-wing protests have a similar profile as the ‘disenchanted critics’ protests analysed above, with similarly high levels of mistrust in political institutions.

Second, our findings add to and qualify insights about protest participants’ profiles. This concerns on the one hand the role of political mistrust in protest participation. While mistrust in political institutions has been identified as an important predictor of protest participation in existing cross-national studies, for Germany, this factor has proven to be much less relevant (see above, Lahusen and Bleckmann Citation2015) – as is the case for some other countries such as Belgium (Norris, Walgrave, and van Aelst Citation2006). The strong differences in trust levels that we identified between the two clusters may explain these inconclusive findings. Furthermore, our results show that political trust among protesters does not necessarily depend on the radicalness of their claims, as we find high levels of trust also in more radical demonstrations such as the G20.

On the other hand, our findings qualify existing insights about the influence of prior protest experience on levels of political trust. In contrast to existing studies (Saunders et al. Citation2012; Sabucedo et al. Citation2017), we do not find that protest participants with more protest experience tend to have lower levels of trust in political institutions and satisfaction with democracy in either cluster. Among the ‘disenchanted critics’ high levels of distrust and dissatisfaction go even along with low levels of prior protest experience, underlining the need to further explore protests that assemble many newcomers in future research.

Finally, the distinction of two different types of protest and in particular, the profile of the ‘disenchanted critics’ helps to clarify recent trends in German (street) politics more broadly. It draws attention to the emergence of a new type of protest that has changed the political landscape in Germany. The Peace Vigils, Pegida as well as the protests against the state response on the Covid pandemic have ushered in formerly inactive citizens and they have been a fertile ground for the growth of populist and conspiracy thinking. All of these protests have built on a cohesive critique of the government and the media that are imagined as parts of a sinister system. Thus, the mobilisation of the ‘disenchanted critics’ has paved the way for a renewed radical right in Germany.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

Survey data used for this paper is not generally available but replication data can be obtained by the authors upon request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Priska Daphi

Priska Daphi is Professor of Conflict Sociology at Bielefeld University.

Sebastian Haunss

Sebastian Haunss is Professor and Head of the Research Group ‘Social Conflicts’ at the Research Centre on Inequality and Social Policy (SOCIUM), University of Bremen.

Moritz Sommer

Moritz Sommer is a researcher at the German Center for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM) in Berlin and a research affiliate at the Institute of Sociology at Freie Universität Berlin.

Simon Teune

Simon Teune is a post-doctoral researcher at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS), Potsdam.

All authors are board members of the Institute for the Study of Protest and Social Movements (ipb).

Notes

1 Notable exceptions include Norris, Walgrave, and van Aelst (Citation2005), who combine insights from population surveys and protest surveys, and, most prominently, the dataset collected in the context of the CCC project, a comparative study of street demonstrations between 2009 and 2013 in eight European countries (van Stekelenburg et al. Citation2012; Walgrave and Verhulst Citation2011; Damen and van Stekelenburg Citation2019). However, this dataset does not include Germany.

2 We are very grateful to the colleagues who collected the data with us and allowed us to integrate them into one coherent data set. The colleagues are: Dieter Rucht (DR) and Mundo Yang (MY) for the protests against the Iraq-war 2003, Wilhelm Heitmeyer, Dieter Rink, Roland Roth, DR, and MY for the Hartz IV protests 2004, Britta Baumgarten, DR, Wolfgang Stuppert (WS), and Simon Teune (ST) for the Stuttgart 21 protests 2010, Priska Daphi (PD), Sebastian Haunss (SH), Oliver Nachtwey, Matthias Quendt, DR, WS, ST and Peter Ullrich for the Peace Vigils 2014, PD, Jochen Roose, DR, WS, ST, and Sabrina Zajak (SZ) for the Pegida protests 2015, PD, SH, Moritz Sommer (MS), WS, ST and SZ for the stop TTIP/CETA protests 2015, PD, Leslie Gauditz, SH, Matthias Micus, Philipp Scharf, MS, ST, and SZ for the G20 protests 2017, SH, DR, MS, ST, and SZ for the Fridays for Future protests 2019, and Madalena Meinecke, Renata Motta, Michael Neuber and ST for the Agricultural Transition protest 2020.

3 Along with the movement’s distrust in major media outlets and its catchphrase ‘Lügenpresse’ (lying press), it also coined the phrase ‘Lügenwissenschaft’ (lying science).

4 only encompasses data for those participants who position themselves somewhere on the left-right scale. Additional answer categories for this question also included ‘do not know’ and, in some cases, ‘no position on this scale’. The share of those in the latter category was particularly large among participants of the Peace Vigils in 2014.

5 We cannot say whether the Hartz IV demonstration is part of this cluster as in this case, participants were not asked about their institutional trust nor about their satisfaction with democracy.

6 It should be noted that this number includes data from surveys conducted at two different demonstrations against the G20-summit, one perceived as moderately leftist on 2 July 2017 and one with a more pronounced anti-capitalist and radical left profile on 8 July 2017. While participants in this latter demonstration showed less trust in the government and in other institutions than those marching on July 2, the average trust levels are still considerably higher than for the demonstrators in the cluster of the ‘disenchanted critics’ (Haunss et al. Citation2017).

7 Wording (Translation from German): ‘With my commitment, I can influence politics in this country’. The wording at the S21-survey was slightly different from the other surveys (‘people like me can have an impact on political decision-makers’).

References

- Andretta, Massimiliano, Lorenzo Bosi, and Donatella Della Porta. 2015. “Trust and Efficacy Taking to the Streets in Times of Crisis: Variation among Activists.” In Austerity and Protest: Popular Contention in Times of Economic Crisis, edited by Marco Giugni, and Maria Grasso, 133–154. London: Routledge.

- Barnes, Samuel, and Max K Kaase. 1979. Political Action: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

- Baumgarten, Britta, and Dieter Rucht. 2013. “Die Protestierenden gegen ,Stuttgart 21‘ einzigartig oder typisch?” In Stuttgart 21. Ein Großprojekt zwischen Protest und Akzeptanz, edited by Frank Brettschneider and Wolfgang Schuster, 97–125. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Braun, Daniela, and Swen Hutter. 2016. “Political Trust, Extra-Representational Participation and the Openness of Political Systems.” International Political Science Review 37 (2): 151–165.

- Catterberg, Gabriela, and Alejandro Moreno. 2005. “The Individual Bases of Political Trust: Trends in New and Established Democracies.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 18 (1): 31–48.

- Christensen, Henrik Serup 2016. “All the Same? Examining the Link Between Three Kinds of Political Dissatisfaction and Protest.” Comparative European Politics 14 (6): 781–801.

- Crouch, Colin. 2004. Post-Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dalton, Russel J. 2004. Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford.

- Dalton, Russell J., Alix van Sickle, and Steven Weldon. 2010. “The Individual–Institutional Nexus of Protest Behaviour.” British Journal of Political Science 40 (1): 51–73.

- Damen, Marie Louise, and Jacqueline van Stekelenburg. 2019. “Crowd-Cleavage Alignment Do Protest Issues and Protesters’ Cleavage Position Align?” In Social Stratification and Social Movements: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives on an Ambivalent Relationship, edited by Sabrina Zajak and Sebastian Haunss, 82–108. London: Routledge.

- Daphi, Priska, Piotr Kocyba, Michael Neuber, Jochen Roose, Dieter Rucht, Franziska Scholl, Moritz Sommer, Wolfgang Stuppert, and Sabrina Zajak. 2015. Protestforschung am Limit. Eine soziologische Annäherung an Pegida. ipb working paper. Berlin: Institut für Protest- und Bewegungsforschung. https://protestinstitut.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/protestforschung-am-limit_ipb-working-paper_web.pdf.

- Dassonneville, Ruth, and Ian McAllister. 2020. “The Party Choice Set and Satisfaction with Democracy.” West European Politics 43 (1): 49–73.

- Décieux, Fabienne, and Oliver Nachtwey. 2014. "Occupy: Protest in der Postdemokratie“, Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 1: 75–89

- Della Porta, Donatella, ed. 2009. Democracy in Social Movements. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Della Porta, Donatella. 2013. Can Democracy Be Saved? Participation, Deliberation and Social Movements. Chichester: Polity Press.

- Della Porta, Donatella, and Massimiliano Andretta. 2014. “Surveying Protestors. Why and How.” In Methodological Practices in Social Movement Research, edited by Donatella della Porta, 308–334. Oxford and Malden, MA: Oxford University Press.

- Fillieule, Olivier. 1997. Stratégies de la rue: Les manifestations en France. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

- Fillieule, Olivier, and Philippe Blanchard. 2010. “Individual Surveys in Rallies (INSURA): A New Tool for Exploring Transnational Activism?” In The Transnational Condition. Protest Dynamics in an Entangled Europe, edited by Simon Teune, 186–210. Oxford & New York: Berghahn Books.

- Flesher Fominaya, Cristina. 2020. Democracy Reloaded: Inside Spain's Political Laboratory from 15-M to Podemos. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2017. The Mask and the Flag: Populism, Citizenism, and Global Protest. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- GESIS. 2015. Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften ALLBUS 2008. ZA4600, Datenfile Version 2.1.0. Köln: GESIS Datenarchiv, doi:10.4232/1.12345.

- GESIS. 2019. Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften ALLBUS 2018. ZA5270, Datenfile Version 2.0.0. Köln: GESIS Datenarchiv, doi:10.4232/1.13250.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1973. Legitimationsprobleme im Spätkapitalismus. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Hadjar, Andreas, and Dennis Köthemann. 2014. “Klassenspezifische Wahlabstinenz. Spielt das Vertrauen in politische Institutionen eine Rolle?” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 66 (1): 51–76.

- Haunss, Sebastian, and Moritz Sommer, eds. 2020. Fridays for Future - Die Jugend gegen den Klimawandel. Konturen der weltweiten Protestbewegung. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Haunss, Sebastian, Priska Daphi, Leslie Gauditz, Philipp Knopp, Matthias Micus, Philipp Scharf, Stephanie Schmidt, et al. 2017. #NoG20. Ergebnisse der Befragung der Demonstrierenden und der Beobachtung des Polizeieinsatzes. ipb working paper. Berlin: Institut für Protest- und Bewegungsforschung. https://protestinstitut.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/NoG20_ipb-working-paper.pdf.

- Hooghe, Marc, and Sofie Marien. 2013. “A Comparative Analysis of the Relation Between Political Trust and Forms of Political Participation in Europe.” European Societies 15 (1): 131–152.

- Hutter, Swen. 2012. “Restructuring Protest Politics: The Terrain of Cultural Winners.” In Political Conflict in Western Europe, edited by Hanspeter Kriesi, Edgar Grande, Martin Dolezal, Marc Helbling, Dominik Höglinger, Swen Hutter, and Bruno Wüest, 151–181. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1990. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kaase, Max. 1999. “Interpersonal Trust, Political Trust and non-Institutionalised Political Participation in Western Europe.” West European Politics 22: 1–21.

- Kern, Anna, Sofie Marien, and Marc Hooghe. 2015. “Economic Crisis and Levels of Political Participation in Europe (2002–2010): The Role of Resources and Grievances.” West European Politics 38 (3): 465–490.

- Klandermans, Bert. 1984. “Mobilization and Participation: Social-Psychological Expansions of Resource Mobilization Theory.” American Sociological Review 49 (5): 583–600.

- Klandermans, Bert. 2013. “Survey Research.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, edited by David A. Snow, Donatella Della Porta, Bert Klandermans, and Doug McAdam, 1–4. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Koopmans, Ruud, and Dieter Rucht. 2002. “Protest Event Analysis.” In Methods of Social Movement Research, edited by Bert Klandermans and Suzanne Staggenborg, 231–259,. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Martin Dolezal, Marc Helbling, Dominic Höglinger, Bruno Wüest, and Swen Hutter. 2012. Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kurer, Thomas, Silja Häusermann, Bruno Wüest, and Matthias Enggist. 2019. “Economic Grievances and Political Protest.” European Journal of Political Research 58 (3): 1–27.

- Lahusen, Christian, and Lisa Bleckmann. 2015. “Beyond the Ballot Box: Changing Patterns of Political Protest Participation in Germany (1974–2008).” German Politics 24 (3): 402–426.

- Meinecke, Madalena, Renata Motta, Janina Henningfeld, Michael Neuber, Moritz Sommer, Simon Teune, and Noemi Unkel. 2021. Politische Ernährung. Mobilisierung, Konsumverhalten und Motive von Teilnehmer*innen der Wir haben es satt!-Demonstration 2020. ipb working paper. Berlin: Institut für Protest- und Bewegungsforschung. https://protestinstitut.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ipb-Working-Paper_Wir-haben-es-satt.pdf

- Norris, Pippa. 2011. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, Pippa, Stefaan Walgrave, and Peter van Aelst. 2005. “Who Demonstrates? Antistate Rebels, Conventional Participants, or Everyone?” Comparative Politics 37 (2): 189–205.

- Norris, Pippa, Stefaan Walgrave, and Peter van Aelst. 2006. “Does Protest Signify Dissatisfaction? Demonstrators in a Postindustrial Democracy.” In Political Dissatisfaction in Contemporary Democracies, edited by Mariano Torcal and José Ramon Montero, 279-309. London: Routledge.

- Rucht, Dieter, and Mundo Yang. 2004. “Wer demonstrierte gegen Hartz IV?” Forschungsjournal Neue Soziale Bewegungen 17 (4): 21–27.

- Rüdig, Wolfgang. 2010. “Assessing Nonresponse Bias in Activist Surveys.” Quality & Quantity 44 (1): 173–180.

- Sabucedo, José-Manuel, Cristina Gómez-Román, Mónica Alzate, Jacquelien van Stekelenburg, and Bert Klandermans. 2017. “Comparing Protests and Demonstrators in Times of Austerity: Regular and Occasional Protesters in Universalistic and Particularistic Mobilisations.” Social Movement Studies 16 (6): 704–720.

- Saunders, Clare. 2014. “Anti-politics in Action? Measurement Dilemmas in the Study of Unconventional Political Participation.” Political Research Quarterly 67 (3): 574–588.

- Saunders, Clare, Maria Grasso, Christiana Olcese, Emily Rainsford, and Christopher Rootes. 2012. “Explaining Differential Protest Participation: Novices, Returners, Repeaters, and Stalwarts.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 17 (3): 263–280.

- Schnaudt, Christian. 2020. “Politisches Wissen und politisches Vertrauen”, In Politisches Wissen in Deutschland, edited by Markus Tausendpfund and Bettina Westle, 127–64. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Sommer, Moritz, and Simon Teune. 2019. “Sichtweisen auf Protest - Die Demonstrationen gegen den G20-Gipfel in Hamburg 2017 im Spiegel der Medienöffentlichkeit.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 32 (2): 149–162.

- Teune, Simon, and Peter Ullrich. 2015. “Demonstrationsbefragungen - Grenzen einer Methode.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 28 (3): 95–100.

- Torcal, Mariano, Toni Rodon, and Maria José Hierro. 2016. “Word on the Street: The Persistence of Leftist-Dominated Protest in Europe.” West European Politics 39 (2): 326–350.

- van Aelst, Peter, and Stefaan Walgrave. 2001. “Who is That (Wo)man in the Street? from the Normalisation of Protest to the Normalisation of the Protester.” European Journal of Political Research 39 (4): 461–486.

- van Stekelenburg, Jacquelien, and Bert Klandermans. 2018. “In Politics We Trust … or Not? Trusting and Distrusting Demonstrators Compared.” Political Psychology 39 (4): 775–792.

- van Stekelenburg, Jacquelien, Stefaan Walgrave, Bert Klandermans, and Joris Verhulst. 2012. “Contextualizing Contestation: Framework, Design, and Data.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 17 (3): 249–262.

- Wahlström, Mattias, Moritz Sommer, Piotr Kocyba, Michiel de Vydt, Joost de Moor, and Stephen Davies. 2019. “Fridays For Future: a New Generation of Climate Activism: Introduction to Country Reports,” In Protest for a Future: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays For Future Climate Protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European Cities, edited by Mattias Wahlström et al. (eds), 5–17. Available from https://osf.io/yr5h4/.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Dieter Rucht, eds. 2010. The World Says No to War: Demonstrations Against the War on Iraq. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Joris Verhulst. 2011. “Selection and Response Bias in Protest Surveys”. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 16 (2): 203–222.

Appendix

Table A1. Linear regression: dependent variable ‘satisfaction with democracy’ (1–5).

Table A2. Linear regression: dependent variable ‘trust in government’ (1–5).

A1. A Short Description of the Protests under Study

15 February 2003, demonstration against the US-led war on Iraq in Berlin. As in many countries across the globe, people in Germany joined millions of protesters against the imminent war on Iraq. The protest in Berlin, organised by networks of the peace movement as well as the global justice movement, parties and trade unions, was the largest of events in several German cities, drawing 500,000 participants. The survey was part of an international cooperation with colleagues in eight countries (Walgrave and Rucht Citation2010).

13 September 2004, protest marches against the ‘Hartz IV’ legislative package in Berlin, Magdeburg, Dortmund, and Leipzig. Demonstrations against the restructuring of social welfare and labour market policy went back to the call by an individual for weekly Monday protests in Magdeburg (Saxony-Anhalt). Reminiscent of Monday protests against the SED regime in 1989 and weekly protests for the preservation of jobs in the transition phase after unification, the protests mushroomed across the country with a steep increase in numbers for weeks (Rucht and Yang Citation2004).

18 October 2010, rally against the demolition of the old and the construction of the new Stuttgart main station (Stuttgart 21). A forceful urban movement opposing the multi-billion Euro project called for weekly protests on Mondays. It was fuelled by representatives of governments from the local to the national level adhering to Stuttgart 21 despite soaring costs, security concerns, and other objections. Environmental organisations, parties, and citizens initiatives mobilised tens of thousands for a sustained period of conflict. The survey was conducted at a mass demonstration that followed an incisive confrontation of protesters trying to inhibit construction works and the police (Baumgarten and Rucht Citation2013).

26 May and 2 June 2014, Montagsmahnwachen (MoMa; Peace Vigils) on occasion of the Ukraine war in Berlin, Bremen, Frankfurt/Main, Dortmund, Erfurt, and Jena. The Peace Vigils were organised by individuals who connected through Facebook. The mobilisation was based on the assumption that the German government would head towards a war with Russia and that professional media in Germany would cover the conflict concordantly with an anti-Russian bias (Daphi et al. Citation2015).

12 January 2015, Pegida march in Dresden. The weekly protests of the Patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the Occident (Pegida) experienced exponential growth within weeks. Organised by a group of acquaintances through a Facebook group, the Monday protests imagined Muslim rule over Germany as an imminent threat. The protests had offsprings in dozens of cities but only in Dresden, the event series succeeded in attracting several thousand participants for an extended period of time (Daphi et al. Citation2015).

10 October 2015, demonstration against the international trade agreements TTIP and CETA in Berlin. As part of an international effort to stop the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), the Berlin event was the largest in a series of local, regional and national protests. It was carried out by an ample coalition of trade unions, environmental, civil right, and global justice organisations as well as cultural and tenants organisations (Daphi et al. Citation2015).

2 and 8 July 2017, protest marches on occasion of the G20 meeting in Hamburg. Two marches of ideologically distinct coalitions framed the international summit in Hamburg’s exhibition halls. Moderate environmental and development aid organisations mobilised for a demonstration preceding a week of action while radical left groups and peace groups called for a march on the second day of the summit. The mood at the second demonstration was heavily influenced by violent confrontations of protesters and police in the days before (Haunss et al. 2015).

15 March 2019, climate protests organised by Fridays for Future (FFF) in Berlin and Bremen. As part of the global climate strike, two of hundreds of events across Germany were surveyed in a collective effort with colleagues in nine countries (Wahlström et al. Citation2019). The protests demanded swift and radical measures to slow down the climate crisis and built on the school strike spearheaded by Greta Thunberg that spread out and inspired local action across the globe. In Germany, the demonstrations were organised by students, supported by environmental organisations, and attended by participants of every age group (Sommer et al. Citation2019; Haunss and Sommer Citation2020).

18 January 2020, march for an agricultural transition in Berlin. Annual ‘Wir haben es satt!’ (WHES; ‘We are fed up!’) protests parallel the agricultural fair since 2010. They are organised by a coalition of organic farmers’ associations, consumer groups, and environmental organisations to promote a shift in the agrarian system towards an organic and animal friendly food production (Meinecke et al. Citation2021).