ABSTRACT

This article analyses the consequences of recent changes in cleavage structures in German society for civil society, democracy, and social cohesion. It argues that the emergence of a new ‘demarcation-integration’ cleavage has politicised civil society in Germany in several ways. As a result, the role of civil society for the future development of German democracy has become highly ambivalent. The article is organised into four parts. First, recent transformations in political conflict structures in Western European countries are outlined. Second, the article presents data on the manifestation of this conflict in Germany after the so-called ‘refugee crisis.’ Third, the consequences of these new conflicts on civil society are analysed. Fourth, the relationship between civil society and democracy is discussed. The article concludes with suggestions for future research.

Ambivalences of Civil SocietyFootnote1

The public understanding of civil society and large parts of civil society research are shaped by strong normative presuppositions. According to this interpretation, civil society is by definition oriented towards the common good, political protest is attributed emancipatory effects, and civic engagement is considered to promote democracy. As a result, the relationship between civil society, democracy, and social cohesion should be unambiguously positive: The stronger civic engagement and organised civil society, the stronger democracy. In a nutshell, civil society makes ‘democracy work’ (Putnam Citation1993) and serves as ‘humus’ (Röpke Citation2021) or ‘cement of society’ (Diani Citation2015). In Germany, the conception of civic engagement as developed by the Study Commission ‘Future of Civic Engagement’ stands exemplarily for such a neo-Tocquevillean model of civil society. Established in 1999 by the German Bundestag, the Commission attributes civil society constitutive importance for social cohesion and democracy (cf. Enquete-Kommission Citation2002) and makes far-reaching recommendations for its activation and strengthening in Germany.

Based on such an understanding of civil society, the causes for the increase of radical populist political parties and movements are primarily located in processes of social disintegration, structural weakness of civil society, and institutional deficits of democracy. Recent political developments in some Eastern European countries such as Poland and Hungary are taken as evidence (for differentiated views, Foa and Ekiert Citation2017; Greskovits Citation2020). However, the electoral successes of the radical right populist ‘Alternative für Deutschland’ (AfD) have triggered public debates over social cohesion and the future of democracy in Germany as well (see, for example, Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2020; More in Common Citation2019; Zentrum Liberale Moderne Citation2019).

The normative assumptions of civil society research and its subsequent focus on the ‘civil’ side of civil society and the democracy-promoting effects of civic engagement are problematic for several reasons. On the one hand, an increasing number of studies on ‘bad’ or ‘uncivil civil society’ (e.g. Berman Citation1997; Chambers and Kopstein Citation2001; Youngs Citation2018; Ekiert Citation2019) have shown that civil society can also have its ‘dark’ sides. These ‘dark sides’ have become apparent in both newly established democracies such as Poland and established democracies such as the US with the rise of religious fundamentalist movements (e.g. McAdam and Kloos Citation2014). On the other hand, the comparative analysis of radical right populist parties in Europe (cf. Kriesi and Pappas Citation2015) reveals that these parties are also strongly represented in countries with stable democratic systems that are very open to political participation, such as Switzerland, and in countries with strong social cohesion, as we find them in Scandinavia (cf. Larsen Citation2013).

This empirical evidence suggests that the relationship between civil society, democracy, and social cohesion is more complicated than commonly assumed in the neo-Tocquevillean model. In the following, I will argue that the role of civil society in contemporary democracies can be highly ambivalent. It is not only the organisational strength of civil society that is decisive for social cohesion and the quality of democratic governance; even more important are its normative orientation, organisational structures, and its embedding in the relevant political conflict structures. It is precisely a strong, well-organised civil society that can weaken democracy and social cohesion in the long term if it is divided and if this division leads to political polarisation and radicalisation. As Berman (Citation1997, 402) concludes, ‘Had German civil society been weaker, the Nazis would never have been able to capture so many citizens for their cause or eviscerate their opponents so swiftly.’ For this reason, it is crucial to know how civil society relates to the relevant political conflicts, how these conflicts affect civil society, and what role civil society plays in organising and articulating these conflicts, as suggested by the contributions to this special issue (for an overview see Hutter and Weisskircher Citation2022).

This argument will be developed based on empirical evidence for Germany in four steps. First, recent transformations in political conflict structures in Western European countries are outlined. In a second step, data on the manifestation of this conflict in Germany after the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ is presented. Third, the consequences of these new conflicts on civil society are analyzed; and, fourth, the relationship between civil society and democracy will be discussed. The article concludes with suggestions for future research.

The Revival of Cleavage Politics: Transformations in Political Conflict Structures in Western Europe

The key to understanding recent developments in civil society is the analysis of political conflict structures. In theory, we can think of a multitude of issues which could in some way or the other cause political conflict; but in reality, there are only very few of them which are strong enough to produce ‘stable system(s) of cleavage and oppositions’ (Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967, 1) between political parties and social groups. West European democracies have been characterised by such a clear and rather stable structure of conflict for most of the time. Their political systems had been dominated by a single ‘cleavage’, the class conflict, throughout the 20th century (Bartolini Citation2000). It is now well established empirically that a change in political conflict structures has been taking place in Western European countries since the 1990s. As a result of this change, a new ‘cleavage’ has emerged constituted by cultural-identitarian issues rather than by socio-economic conflicts (cf. Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012; Hooghe and Marks Citation2018).Footnote2 This change was triggered by the process of globalisation in its various dimensions: economic, political, and socio-cultural. The consequences of global economic interdependence, European integration, and cross-border migration have nurtured new conflicts between groups of (actual and potential) ‘winners’ and ‘losers.’ These groups cut across existing social classes. They form heterogeneous new mobilisation potentials that undermine conventional social and political categorizations. The new conflicts are not only about the economic consequences of globalisation; more importantly, they are about questions of authority, belonging, social inclusion, and identity. The opposite poles in this conflict are ‘closure,’ ‘exclusion,’ and ‘demarcation’ on the one hand, ‘openness,’ ‘recognition,’ and ‘integration’ on the other. This opposition can refer to the closure or opening of markets, but also to the degree of political integration of nation-states into international organisations and the opening of national societies to immigration and the conditions of the integration of migrant groups. In the socio-cultural sphere, a universalistic or cosmopolitan position of openness and mutual recognition contrasts with the demarcation of others and the particularistic defense of national identities and cultural values. Through this transformation, the conflict structures of capitalist industrial society (capital vs. labour) continue to lose significance; and the ‘new value’ conflicts that have arisen in the course of ‘postmodernization’ (Inglehart Citation1998) since the 1960s (materialism vs. post-materialism) are accentuated and reinforced. Empirical studies have shown that this has far-reaching effects on the dynamics and structures of political mobilisation and social capital formation in contemporary societies (see, e.g. Beramendi et al. Citation2015; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019).

As a result, European societies have by no means become ‘post-identitarian,’ as claimed by Crouch, who argues that ‘we have entered a stage of postmodern society in which no identities have power enough to define us politically’ (Citation2016, 150; translation by author). Strong, identity-forming conflicts still shape them – but the meaning of this cleavage and the constituting issues have changed. Indeed, the new ‘demarcation-integration’ cleavage has not emerged in all European countries in the same way and with the same intensity (cf. Kriesi Citation2016; Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019). It is particularly pronounced in North-Western Europe, while in Southern European countries, economic conflicts play a greater role, especially in the wake of austerity policies forced by the Eurozone crisis (cf. della Porta Citation2015; Giugni and Grasso Citation2015). In Western Europe, the new cleavage has so far been constituted primarily by two highly contentious issues: immigration and European integration. These have been controversial issues since the 1990s, and the Eurozone crisis and the ‘refugee crisis’ certainly intensified these conflicts (on Europe, cf. Hutter, Grande, and Kriesi Citation2016; on immigration Grande, Schwarzbözl, and Fatke Citation2019; Hutter and Kriesi Citation2021). In essence, these new ‘cleavage issues’ intensify not socio-economic (distributional) conflicts, but cultural-identitarian (value) conflicts. These conflicts cut across the class conflicts of industrial society and cannot be adequately identified based on a simple one-dimensional spatial model of politics. The new conflicts have created a new two-dimensional political space characterised by two (more or less) independent conflict dimensions: a socio-economic conflict dimension and a cultural-identitarian conflict dimension. The cultural-identitarian conflict dimension is shaped by the issues of immigration, European integration, and cultural liberalism (i.e. attitudes towards minorities, gender issues, and the protection or expansion of individual rights). In this two-dimensional conflict space, the distinction between ‘left’ and ‘right’ does not become meaningless, but its significance is weakened.

In West European countries – and beyond –, radical right populist parties have been most forceful in exploiting these new political potentials. These parties are considered the ‘drivers’ of the formation of the new cleavage; their rise and lasting electoral success is attributed to a vigorous strategy of emphasising the new ‘cleavage issues’. As a result, scholars observe an increasing fragmentation and polarisation of party systems (Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012). The crucial question then is how these conflicts have materialised in German politics and how they have affected civil society?

The Significance of the New Cleavage for the 2017 German Federal Election

Among the group of West European countries, Germany was considered a special case in the scholarly literature for years. Although there was evidence that the new cleavage had some impact on party competition and voter behaviour, these changes did not result in the successful formation of a new radical right populist party at the national level, as compared, for example, to France, Austria, and Switzerland. Noteworthy cases of failure of new radical right populist or extreme right parties in federal elections were the Republikaner (Republicans), the DVU (the German People’s Union – Deutsche Volksunion), or the so-called ‘Schill Party’ (Party for a Rule of Law Offensive – Partei Rechtsstaatlicher Offensive). These parties indeed articulated and represented the ‘demarcation’ pole of the new ‘demarcation-integration’ cleavage, but none of them succeeded in gaining seats in the federal parliament. In particular, electoral successes of the Republikaner in local and state elections and the election to the European Parliament in 1989 were a clear indication of the emergence of a new conflict potential. The literature identified several reasons why the (populist) ‘dog did not bark’ in Germany (Dolezal Citation2008; see also Bornschier Citation2012). Most importantly, the Christian-Democratic parties CDU and CSU have repeatedly been serving as the functional equivalent to radical right populist parties in other countries. In several major public controversies (e.g. in the debates over Turkey’s EU membership in the mid-2000s), they occupied the same positions in the new two-dimensional political space as radical right populist parties in other West European countries. However, established moderate right parties in Germany had withstood the temptation to fundamentally transform their ideological profile to occupy this sector of the political space permanently as the Austrian FPÖ (Freedom Party) and the Swiss SVP (Swiss People’s Party) did. In addition, the PDS (Party of Democratic Socialism) – later Linkspartei, since 2007: Die Linke – to some extent a leftwing populist party, also absorbed part of the protest voters who were dissatisfied with the established ‘Volksparteien’ in particular in East Germany.

In the following, I will present data from the 2017 federal election, which shows that the new ‘demarcation-integration’ cleavage has fully developed meanwhile in Germany. Issues constitutive for the new cleavage have been structuring both the demand side of voters and the supply side of party competition in this election.

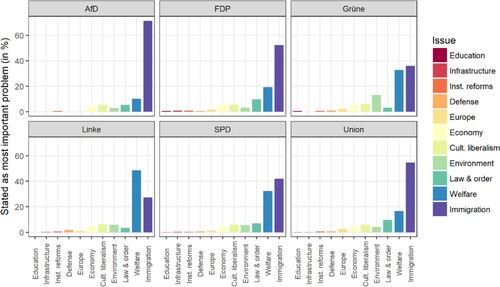

First, data from the national election study (the German Longitudinal Election Study; GLES) show that the immigration issue – or, more precisely, the topic ‘immigration–refugees–political asylum’Footnote3 – played an outstanding role for voters in the 2017 federal election. Although its salience had declined since the peak of the refugee crisis in autumn 2015, the immigration issue remained the most important political issue for voters in the election campaign. A more differentiated view of voters’ party affiliations shows that this was the case for voters of all parties except the Left Party (Die Linke) voters (). The immigration issue was by far the most important issue for voters of the moderate right parties CDU and CSU and the liberal FDP (Free Democratic Party). For SPD and Green Party voters, immigration was of greater significance than their core issues ‘social welfare’ and ‘environment,’ respectively. For AfD voters, it was of unique importance; other issues were almost insignificant for them. This holds even for the European integration issue, which was the constitutive issue for the party during the European sovereign debt crisis.

Figure 1. The most important issues for voters in the 2017 German federal election.

Source: German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES Citation2019, ZA6803 pre-release).

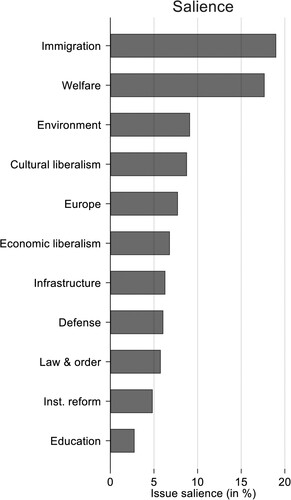

The empirical analysis of the election campaign on the basis of media dataFootnote4 shows that the immigration issue did indeed play a central role in public election debates, although Manifesto data suggest that the major parties had intended a subordinate role for it in their overall campaign strategies (Grande, Schwarzbözl, and Fatke Citation2019). As we can see in , the immigration issue was the most visible issue in the 2017 election campaign. Its salienceFootnote5 was higher than that of social welfare issues that had dominated previous election campaigns. The other two constitutive issues for the new cleavage, ‘cultural liberalism’ and ‘European integration,’ were also very visible. As a result, the overall salience of the new cultural–identitarian cleavage was greater than the salience of the socio-economic conflict dimension in this election campaign. Because foreign policy issues and matters of national security (labelled ‘defense’ in ) – like Germany’s or EU’s relationship to Turkey or the civil war in Syria – were discussed in relation to issues of immigration and European integration, the significance of the cultural–identitarian cleavage might have been even more significant.

Figure 2. Salience of the most important issues in the 2017 German federal election.

Note: Salience is operationalised as the percentage share of core sentences of an issue such as, for example, immigration compared to the number of all observations during an election campaign. Source: Kriesi et al. (Citation2020).

In order to structure political conflict, controversial issues have not only to be visible in public; they must also polarise between parties. In this regard, the data reveals significant differences between the two most salient issues in the 2017 election campaign, immigration and welfare. As we can see in (right-hand panel), immigration is by far the most decisive polarising issue. By contrast, welfare issues had only a very moderate polarising effect, especially between the major parties. Taken together, the immigration issue was not only the most visible issue; it was also the most divisive topic of the entire election campaign. This was the biggest difference to the 2013 federal election (; left-hand panel), in which there was no issue with such a politicising force (Schwarzbözl and Fatke Citation2016). The 2013 campaign was dominated by welfare issues, such as a minimum wage, on which there were only moderate positional differences between the two major parties. More strongly polarising issues like immigration had only weak visibility in 2013; and European integration was, at that time, only moderately polarising between the established parties.Footnote6

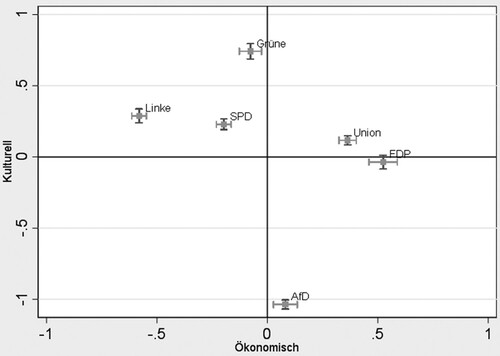

Figure 3. Positioning of parties in the political space in the 2013 and 2017 German federal elections.

Note: The two figures show the results of multidimensional scaling (MDS) whereby the salient issues of an election campaign – e.g. social welfare [welfare], economic reform [ecolib], cultural liberalism [cultlib], immigration [anti-immig], etc. – and the most important political parties – ‘union’ (CDU), ‘gr’ (Grüne), ‘rl’ (Linkspartei), ‘spd’, ‘fdp’ and ‘afd’ – are placed in relation to one another. The positional proximity of a party to an issue signals agreement with respect to the content, whereas positional distance signals corresponding rejection. Source: Kriesi et al. (Citation2020).

![Figure 3. Positioning of parties in the political space in the 2013 and 2017 German federal elections.Note: The two figures show the results of multidimensional scaling (MDS) whereby the salient issues of an election campaign – e.g. social welfare [welfare], economic reform [ecolib], cultural liberalism [cultlib], immigration [anti-immig], etc. – and the most important political parties – ‘union’ (CDU), ‘gr’ (Grüne), ‘rl’ (Linkspartei), ‘spd’, ‘fdp’ and ‘afd’ – are placed in relation to one another. The positional proximity of a party to an issue signals agreement with respect to the content, whereas positional distance signals corresponding rejection. Source: Kriesi et al. (Citation2020).](/cms/asset/85bb161d-9971-4ee9-8609-4df0a3c60b89/fgrp_a_2120610_f0003_ob.jpg)

What kind of conflict structure results from this? The following analyses reveal the conflict structures in the party system () and the electorate (). shows the positioning of the parties in 2017 vis-à-vis one another and the most important campaign issues. For purposes of comparison, the corresponding positions in 2013 are also presented. In order to facilitate the interpretation, the economic and social welfare issues constituting the socio-economic conflict dimension are connected in such a way that they form the horizontal axis of the political space. The parties’ positioning along this axis corresponds in general to our expectations: the FDP occupies the liberal (right) pole, the Greens the interventionist (left) pole,Footnote7 the SPD and the CDU hold positions in between. On this dimension, the parties are positioned left-of-centre, interpreted as ‘social democratization’ of the CDU vis-à-vis economic and welfare state issues in public debates. However, decisive for the overall structure of the political space is the second conflict dimension, which was characterised by the immigration issue. The critical distance to immigration (‘anti-immigration’) and to cultural liberalism constituted a distinct pole in the political space in 2017, and the AfD exclusively occupied this pole. The AfDs positioning on this issue set it apart from the other parties in the political space. This two-dimensional structure can also be found in the 2013 election, even though the distance between the AfD and the other parties was markedly smaller, and the AfD was not so negatively positioned vis-à-vis the immigration issue.

Figure 4. Positioning of voters in the political space in the 2017 German federal election.

Note: This diagram shows a varimax-rotated, two-factor solution matrix for the principal component analysis. The horizontal axis comprises the economic conflict dimension based on the three issues ‘welfare state’, ‘government intervention’, and ‘budget finance’; the vertical axis comprises the cultural-identitarian dimension based on the two issues ‘European integration’ and ‘immigration.’ All variables are standardised. Source: German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES Citation2019, ZA6803 pre-release)

A permanent restructuring of political conflict can only be expected if both parties and voters are polarised in the same way, however. shows the positioning of voters in the political space in the 2017 federal elections. The overall structure is not completely identical to the distribution of the parties in , because the voter analysis was based on a smaller number of issues.Footnote8 The horizontal dimension was constructed from the voters’ positions to economic and welfare state issues; the vertical dimension was calculated from their attitudes towards immigration and European integration. Apparently, voters can be clearly located in the two-dimensional space on the basis of their preferences towards these issues. Again we find a distinct voter distribution along the socio-economic line of conflict: voters of the FDP and the Christian-Democratic parties occupy the pole on the right; the Left Party and SPD voters occupy the one on the left. On the socio-economic dimension, voters of the Green Party and AfD supporters occupy the centre of the political space. Most important, however, the voters’ political space also shows a two-dimensional structure and the second dimension is constituted by the two cultural-identitarian issues. On this ‘demarcation–integration’ dimension, voters of AfD and the Green Party occupy the extreme poles, while voters of the other parties, including the Christian-Democratic parties, occupy the centre of the political space.Footnote9

Summing up, three conclusions can be drawn from these analyses. First, there is empirical evidence that Germany is no longer an exceptional case. In the last decade, the new ‘demarcation–integration’ cleavage has fully developed its transformative power by restructuring both party competition and voter alignments. Second, a comparison to the 2013 election shows that this new cleavage structure is not only a result of the ‘refugee crisis’ in 2015. In 2013, we already find the same conflict constellation both among voters and parties, even though the AfD failed (albeit barely so) to gain seats in Germany’s federal parliament at that time. The AfD had already occupied the ‘demarcation’ pole of the new ‘cleavage’ in 2013. Third, it is quite remarkable that AfD voters position themselves unequivocally and unanimously behind the newly contended issues. This finding is at odds with the assumption that these individuals are ideologically diffuse ‘protest voters.’ In line with literature on the electoral successes of radical right populist parties (Mudde Citation2007; Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012; Bornschier Citation2010; Kriesi and Pappas Citation2015), it suggests that a significant number of AfD voters are motivated by distinct political preferences and ideological convictions which correspond to the programmatic positions of the AfD.

Apparently, the 2017 federal election was characterised by the interplay between long-term structural changes in the political landscape (viz., the emergence of a new cleavage), on the one hand, and the consequences of an ‘attention-grabbing event’ (Mader and Schoen Citation2019) (viz., the ‘refugee crisis’), on the other. The ‘refugee crisis’ focused attention on the new policy dimension, which was undoubtedly advantageous to those political parties who attached a great deal of importance to the immigration issue, and with whom voters associated it. Since this issue was constitutive for a structural line of political conflict which already had considerable polarising potential in previous elections, this effect was particularly strong in the 2017 election. Hence, the ‘refugee crisis’ was catalysing the evolution of the new cleavage.

Recent analyses of the 2021 federal election show that this change has had lasting consequences. Burst et al.'s (Citation2021) analysis of the parties’ election programmes shows that their programmatic profiles can be mapped in a two-dimensional space. There were clear differences between the parties on socioeconomic issues on the one hand and cultural-identitarian issues on the other. The parties’ positioning on these issues largely corresponds to their positioning in the 2017 election. In addition, voter surveys by Roose (Citation2021) show increasing polarisation in the electorate and among party supporters. What is striking here is the strong polarising power of the migration issue. The issue of migration policy shows the greatest differences in attitudes among party supporters. In turn, large sections of supporters of the Left and the Greens are opposed to large sections of AfD supporters. This corresponds to the pattern of polarisation shown above for the 2017 federal election.

The Politicisation of Civil Society in Germany

What follows from this for political protest and civil society in Germany? The new conflicts not only put political parties under pressure, they also result in a profound politicisation of civil society. The concept of politicisation can be found in several meanings in the scholarly literature (for a short summary see Grande and Hutter Citation2016, 7ff). In political sociology, politicisation emphasises political conflict, the ‘dynamics of the expansion of the scope of political conflict’ (Schattschneider Citation1960, 16) among actors in particular. Political conflict must not be confined to the electoral arena and party competition. Instead, the intensification of political conflict is characterised by an increasing number and diversity of actors beyond party politics and a stronger polarisation among these actors. Research on civil society organisations (CSOs) distinguishes three facets of politicisation (Bolleyer Citation2021, 499f.): (a) the transition of an issue from the private to the public sphere; (b) a CSO’s action repertoire; and (c) the targets of organisational activities.

Politicisation of civic engagement is an important and so far underestimated aspect of the current transformation of civil society in Germany. Changes within civil society are a central topic of civil society research (e.g. Grande, Grande, and Hahn Citation2021). There is ample empirical evidence that the associational foundations of late modern societies have been changing (see Putnam Citation1995, Citation2000, Citation2001; Wuthnow Citation1998; Skocpol Citation2003). This applies to voluntary, membership-based civic associations, as well as social movements and political parties. For civic engagement in Germany, these changes were documented by the Study Commission ‘Future of Civic Engagement’ (Enquete-Kommission Citation2002) already in the early 2000s, and they have since been described in many details by several surveys (e.g. Priemer, Krimmer, and Labigne Citation2017; Simonson, Vogel, and Tesch-Römer Citation2017; Dritter Engagementbericht Citation2020; BMFSFJ Citation2021). These surveys indicate that civic engagement has increased over time; but that the range of activities and the organisational forms have been changing. Most important, permanent and formal ties to voluntary associations and parties have been losing importance, while new, more flexible, and informal forms of engagement have become more attractive for citizens.

At the same time, civil society is becoming ‘more political’ (Priemer, Krimmer, and Labigne Citation2017, 5; translation by author). It is true that volunteering is proportionately most common in sports, culture and music, or the social sector. Activity in organisations with political objectives (e.g. political parties) accounts for only a very small share (2.9 percent) of civic engagement in Germany (BMFSFJ Citation2021, 24). However, there is evidence of an increasing importance of fields of civic engagement with explicit political objectives, as compared to cultural or leisure activities. This holds in particular for highly professionalised ‘voluntary agencies’ (cf. Bolleyer Citation2021). Moreover, civil society has become engaged in the new conflicts outlined above, regardless of the specific area of engagement. At closer inspection, several patterns and channels of the politicisation of civil society can be identified in Germany.

First, existing civil society organisations such as unions, churches, and sports clubs have been politicised in several ways. On the one hand, these organisations have been forced by its members to take sides in controversies over, for example, migration and human rights. Recent public demonstrations by soccer players and athletes against racism exemplify this. As a response, organised civil society has been put ‘under pressure’ by radical right populist parties (the AfD in particular) and organisations to enforce their political ‘neutrality’ in political controversies (Schroeder et al. Citation2020; see Schroeder et al. Citation2022 in this special issue). On the otherhand, the new cleavage has been carried into existing organisations, such as trade unions, by the AfD in an effort to become ‘anchored in society’. As a result, the new cleavage not only polarises political parties, it also ‘divides families, polarises workplaces and schools’ (Kleffner and Meisner Citation2017, 9; translation by author).

Second, the number of new civil society associations with explicit socio-political objectives (e.g. human rights, refugee aid) has been increasing (Priemer, Krimmer, and Labigne Citation2017). The numerous refugee aid initiatives and projects that emerged in the ‘refugee crisis’ in Germany are recent examples of this new humanitarian impetus of civil society. Schiffauer, Eilert, and Rudloff (Citation2017, 13) estimated in 2017 that over five million citizens got involved in around 15,000 projects and initiatives during this time at the local level. According to the most recent survey on civic engagement in Germany (BMFSFJ Citation2021, 26), more than one in ten people aged 14 and over have volunteered for refugees and asylum seekers in the last five years. This solidarity movement is situated between social charitable engagement and political participation – with fluid transitions, for example, when refugee aid initiatives and networks demonstrate against restrictive state policies and bureaucratic practices, as observed, for example, in Bavaria (Poweleit Citation2021).

Third, civil society has been politicised by new social movements ‘from the right’, which have successfully mobilised citizens on the streets by articulating the new cleavage issues, potential threats imposed by immigrants and refugees in particular (Caiani, della Porta, and Wagemann Citation2012). In Germany, the protest arena has been increasingly used by new xenophobic movements, such as Pegida (Vorländer, Herold, and Schäller Citation2018). These organisations and groups interacted with the radical right populist AfD and constituted radical right populism ‘as a social movement’ in the last decade (Rucht Citation2017; Häusler and Schedler Citation2016; Weisskircher and Berntzen Citation2019). Protest against the public corona measures in Germany is a recent example of this new protest wave. It brings together socially and politically very heterogeneous groups, including radical right political groupings (see Heinze and Weisskircher Citation2022 in this special issue).

Finally, organised counter-mobilisation against radical right populism has been politicising civil society. The activities of the AfD and movements ‘from the right’ such as Pegida have increasingly meet political resistance on the streets (Vüllers and Hellmeier Citation2021). The result is a pattern of mobilisation and counter-mobilisation, exemplified in recent years by Pegida and by protest events on migration issues in Chemnitz, Kandel, and in other cities. Vüllers and Hellmeier (Citation2021, 1) show that counter-mobilisation intensifies conflict rather than containing a radical right populist movement: ‘large counter-demonstrations are associated with larger subsequent Pegida protests, and violence against Pegida supporters reduces the likelihood that they will stop protesting’.

In sum, the new conflicts have profoundly shaped civil society and its associations in the last decade. This politicisation of civil society is highly ambivalent, however. By dividing ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of de-nationalization, the new ‘demarcation-integration’ cleavage has not only strengthened those progressive social movements that emerged in the course of the 1960s and 1970s, it also showed the ‘dark side’ of civil society.

Civil Society, Cleavage Structures, and Democracy

The crucial questions then are: How does the politicisation of civil society affect the relationship between civil society and democracy? Is it strengthening democracy – or does it instead threaten it? The answer to these questions depends not least on where precisely the lines of conflict run in society. In principle, three basic constellations are conceivable.

In the first constellation, the dominant conflict line runs between (liberal) civil society on the one hand and the (authoritarian) state on the other. This conflict constellation was characteristic of the most recent global waves of democratisation, in which civil society mobilised against authoritarian regimes in Eastern Europe and the Arab world. In the other two constellations, the lines of conflict do not run between state and civil society but within civil society. In the pluralist model, civil society is divided by a multitude of different conflicts that cut across each other, thus avoiding intense polarisation. This model corresponds to Tocqueville’s model of civil society and the normative ideal of pluralist theory. Alternatively, civil society is divided and polarised by one (or a few) dominant conflict line(s), most importantly class conflict or religious conflicts. This constellation was characteristic of Western European societies in the late 19th and 20th centuries, as analyzed exemplarily by Rokkan; and it profoundly shaped the party systems of these countries (cf. Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967; Rokkan Citation2000).

Apparently, civic engagement must not necessarily have a positive effect on democracy. A positive relationship between civil society and democracy is most likely in the first two constellations. However, this does not hold for the third constellation. When societal conflicts lead to the formation of closed and antagonising social groups, civil society organisations tend to reinforce such conflicts, thus weakening social cohesion and threatening democracy. Such a ‘pillarization’ of societies and the formation of religiously, ethnically or ideologically based ‘camps’ (Lager) is a well-known phenomenon in comparative democracy research (for an overview see Hellemans Citation2020). In the 20th century, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Austria were textbook examples of the successful integration of such divided societies through elite cooperation (Lehmbruch Citation1967; Lijphart Citation1968; Steiner and Ertmann Citation2002).

European history was not only shaped by positive experiences in which it was possible to build ‘bridges’ between hostile ‘camps’ and to accommodate conflicts, however. It also knows examples of unbridgeable hostility, civic war and the expulsion and extermination of social and political adversaries. Hence, comparative research on social capital concluded that the social capital accumulated by civil society ‘does not automatically lead to a democratic character’ (Putnam and Goss Citation2001, 24; translation by author). As Berman (Citation1997) shows for the Weimar Republic and Ekiert (Citation2019), most recently with the example of Poland, a strong civil society can also be instrumentalised by non-democratic forces to establish an authoritarian regime.

Conclusions

The individual willingness to engage and the organisational strength of civil society are indispensable preconditions for social cohesion and democratic governance. However, they are not sufficient to guarantee social and political stability. In addition, as shown in this article, the embedding of civil society in the relevant political conflict structures is of crucial importance. Current changes in the structure of political conflict and the politicisation of civil society in Germany exemplify this ambiguous role of civil society. Against this background, it seems as if German civil society has arrived at a critical juncture. While civic engagement has been increasing, there is also evidence of a stronger politicisation and polarisation. Hence, concerning the future of democracy in Germany, it is an open question whether civil society will be part of the problem or part of the solution.

These findings have several implications for future research on political conflict and civil society in Germany. First of all, empirical research on civil society is well advised not to limit its field of investigation by too strong normative presuppositions and a narrow focus on the ‘civil’ side of civic engagement. For an adequate understanding of the current challenges of democracy, it is indispensable to capture civil society in all its manifestations – and with all its ambiguities and contradictions. From such a perspective, civil society is characterised by a conflictive coexistence and plurality of interests, values, goals, actors, and forms of action. It serves as a battleground for conflicting actors rather than representing a specific type of organisation or actor. Second, to understand the role of civil society for the functioning and development of democracy, research should pay more attention to (a) the mechanisms for the politicisation of civil society, (b) the dynamics of conflict, and (c) the driving forces of radicalisation. My analysis of the German case suggests that civil society can play an essential role in mobilising new political oppositions and structuring and restructuring political conflict. Finally, the literature on social capital suggests that civil society can not only contribute to an intensification of political conflict; it can also play a crucial role in accommodating and absorbing conflict. Most important in this regard are cross-cutting forms of social solidarity and more encompassing identities, as we find them in forms of ‘bridging social capital’ (Putnam Citation2000, Citation2007). Therefore, it is an imminent task for civil society research to identify the preconditions for forming and accumulating such ‘bridging’ social capital. Knowledge of this is crucial for civil society to live up to the normative expectations placed on it.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Edgar Grande

Edgar Grande is Founding Director of the Center for Civil Society Research at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center in Germany.

Notes

1 This article builds upon two recent publications: Grande (Citation2018a, Citation2018b). The author acknowledges the support of Tobias Schwarzbözl in analyzing the data on the 2017 German election.

2 On the cleavage concept in political sociology more generally see Bartolini (Citation2005).

3 For reasons of readability, I will use the term ‘immigration issue’ throughout this article as an umbrella term for all matters related to national and transnational migration issues.

4 Data on public election debates is taken from Kriesi et al. (Citation2020) and available via the Pol-Dem data portal (https://poldem.eui.eu/). This data is based on a quantitative content analysis of press coverage of the election campaign in the last two months prior to the election. It relies on newspaper articles. For each country, a quality newspaper and a tabloid newspaper were chosen, in Germany Süddeutsche Zeitung and Bild. Articles referring to politics were selected and subsequently coded using the core sentence approach, a method developed by Kleinnijenhuis and Pennings (Citation2001). For a detailed description of this methodology see Kriesi et al. (Citation2012, Ch. 2).

5 Salience refers to the visibility of an issue in relation to all other issues in an election campaign. Accordingly, the indicator is operationalised as the percentage share of core sentences of an issue such as, for example, immigration compared to the number of all observations during an election campaign.

6 In the Eurozone crisis, divisions on European issues mainly unfolded within mainstream parties and between the two Christian-Democratic parties CDU and CSU (Grande and Kriesi Citation2015).

7 The left positioning of the Green Party is partly due to the fact that environmental issues are embedded into the socio-economic cleavage.

8 In particular, the environmental issue is not included in the voter data because it was subsumed under socio-economic issues in party competition. Because of the relatively high visibility of environmental issues in the 2017 campaign and the strong affinity of the Green Party to this issue, the Greens slide further to the left on the socio-economic conflict dimension in Figure 3.

9 As a similar pattern was observed in the 2013 federal elections already (cf. Schwarzbözl and Fatke Citation2016). Therefore, this positioning of voters should not be interpreted as a consequence of the moderate right parties’ voter losses in the 2017 election.

References

- Bartolini, Stefano. 2000. The Political Mobilization of the European Left, 1860–1980. The Class Divide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bartolini, Stefano. 2005. “La Formation des Clivages.” Revue International de Politique Comparée 12 (1): 9–34.

- Beramendi, Pablo, Silja Häusermann, Herbert Kitschelt, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. 2015. The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berman, Sheri. 1997. “Civil Society and the Collapse of the Weimar Republic.” World Politics 49 (3): 401–429.

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2020. Gesellschaftlicher Zusammenhalt in Deutschland 2020. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- BMFSFJ. 2021. Freiwilliges Engagement in Deutschland. Zentrale Ergebnisse des Fünften Deutschen Freiwilligensurveys (FWS 2019). Berlin: BMFSFJ.

- Bolleyer, Nicole. 2021. “Civil Society – Politically Engaged or Memberserving? A Governance Perspective.” European Union Politics 22 (3): 495–520.

- Bornschier, Simon. 2010. Cleavage Politics and the Populist Right: The New Cultural Conflict in Western Europe. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Bornschier, Simon. 2012. “Why a Right-Wing Populist Party Emerged in France but Not in Germany: Cleavages and Actors in the Formation of a New Cultural Divide.” European Political Science Review 4 (1): 121–145.

- Burst, Tobias, Christoph Ivanusch, Pola Lehmann, Sven Regel, and Lisa Zehnter. 2021. “Rot-Grün-Rot passt am besten zusammen”, ZEIT online, 19.09.2021.

- Caiani, Manuela, Donatella della Porta, and Claudius Wagemann. 2012. Mobilizing on the Extreme Right: Germany, Italy and the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chambers, Simone, and Jeffrey Kopstein. 2001. “Bad Civil Society.” Political Theory 29 (6): 837–865.

- Crouch, Colin. 2016. “Neue Formen der Partizipation: Zivilgesellschaft, Rechtspopulismus und Postdemokratie.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 29 (3): 143–153.

- della Porta, Donatella. 2015. Social Movements in Times of Austerity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Diani, Mario. 2015. The Cement of Society: Studying Networks in Localities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dolezal, Martin. 2008. “Germany: The dog That Didn’t Bark.” In West European Politics in the Age of Globalization, edited by Hanspeter Kriesi, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheus Frey, 208–234. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dritter Engagementbericht. 2020. “Zukunft Zivilgesellschaft: Junges Engagement im digitalen Zeitalter.” Deutscher Bundestag, 19. Wahlperiode, Drucksache 19/19320, May 14.

- Ekiert, Grzegorz. 2019. Civil Society as a Threat to Democracy: The Case of Poland. Unpublished Manuscript.

- Enquete-Kommission. 2002. “Report of the Study Commission ‘Zukunft des Bürgerschaftlichen Engagements’: Bürgerschaftliches Engagement: auf dem Weg in eine zukunftsfähige Bürgergesellschaft.” Deutscher Bundestag, 14. Wahlperiode, Drucksache 14/8900, June 02.

- Foa, Roberto Stefan, and Grzegorz Ekiert. 2017. “The Weakness of Postcommunist Civil Society Reassessed.” European Journal of Political Research 56: 419–439.

- Giugni, Marco, and Maria Grasso, eds. 2015. Austerity and Protest: Popular Contention in Times of Economic Crisis. London: Routledge.

- GLES. 2019. “Rolling Cross-Section-Wahlkampfstudie mit Nachwahl-Panelwelle (GLES 2017)”. (ZA6803 Datenfile Version 1.0.0) Köln: GESIS Datenarchiv. doi:10.4232/1.12941.

- Grande, Edgar. 2018a. “Der Wandel politischer Konfliktlinien - Strategische Herausforderungen und Handlungsoptionen für die Volksparteien.” In Zwischen Offenheit und Abschottung. Wie die Politik zurück in die Mitte findet, edited by Wilfried Mack, 17–43. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder.

- Grande, Edgar. 2018b. “;Zivilgesellschaft, politischer Konflikt und soziale Bewegungen.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 31 (1-2): 52–59.

- Grande, Brigitte, Edgar Grande, and Udo Udo Hahn. eds. 2021. Zivilgesellschaft in Deutschland. Aufbrüche, Umbrüche, Ausblicke. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Grande, Edgar, and Swen Hutter. 2016. “Introduction: European Integration and the Challenge of Politicization.” In Politicizing Europe, edited by Swen Hutter, Edgar Grande, and Hanspeter Kriesi, 3–31. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grande, Edgar, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2015. “Die Eurokrise: Ein Quantensprung in der Politisierung des europäischen Integrationsprozesses?” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 56 (3): 479–505.

- Grande, Edgar, Tobias Schwarzbözl, and Mathias Fatke. 2019. “Politicizing Immigration in Western Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (10): 1444–1463.

- Greskovits, Béla. 2020. “Rebuilding the Hungarian Right Through Conquering Civil Society: The Civic Circles Movement.” East European Politics 36 (2): 247–266. doi:10.1080/21599165.2020.1718657.

- Häusler, Alexander, and Jan Schedler. 2016. “Neue Formen einer flüchtlingsfeindlichen sozialen Bewegung von rechts.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 29 (2): 11–20.

- Heinze, Anna-Sophie, and Manès Weisskircher. 2022. “How Political Parties Respond to Pariah Street Protest: The Case of Anti-Corona Mobilization in Germany”, German Politics, Special Issue on “Civil society, social movements, and the polarization of German politics”, Advance Online Publication.

- Hellemans, Staf. 2020. “Pillarization (‘Verzuiling’). On Organized ‘Self-Contained Worlds’ in the Modern World.” American Sociologist 51: 124–147. doi:10.1007/s12108-020-09449-x.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. 2018. “Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1): 109–135.

- Hutter, Swen, Edgar Grande, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. 2016. Politicizing Europe: Integration and Mass Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. 2019. European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2021. “Politicizing Immigration in Times of Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853902.

- Hutter, Swen, and Manès Weisskircher. 2022. “New contentious politics. Civil society, social movements, and the polarization of German politics”, German Politics, Special Issue on “Civil society, social movements, and the polarization of German politics”, Advance Online Publication.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1998. Modernisierung und Postmodernisierung. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

- Kleffner, Heike, and Matthias Meisner. 2017. “Vorwort: 1990 bis 2016 – Unter Sachsen.” In Unter Sachsen. Zwischen Wut und Willkommen, edited by Heike Kleffner, and Matthias Meisner, 8–10. Berlin: Links Verlag.

- Kleinnijenhuis, Jan, and Paul Pennings. 2001. “Measurement of Party Positions on the Basis of Party Programmes, Media Coverage and Voter Perceptions.” In Estimating the Policy Positions of Political Actors, edited by Michael Laver, 162–182. London: Routledge.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2016. “The Politicization of European Integration.” Journal of Common Market Studies 54 (S1): 32–47.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Martin Dolezal, Marc Helbling, Dominic Höglinger, Swen Hutter, and Bruno Wüest. 2012. Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, E. Grande, S. Hutter, A. Altiparmakis, E. Borbáth, S. Bornschier, and B. Bremer. 2020. “PolDem National Election Campaign Dataset, Version 1” (dataset). https://poldem.eui.eu/.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheus Frey. 2008. West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Takis S. Pappas, eds. 2015. European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Larsen, Christian Albrekt. 2013. The Rise and Fall of Social Cohesion: The Construction and Deconstruction of Social Trust in the US, UK, Sweden, and Denmark. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lehmbruch, Gerhard. 1967. Proporzdemokratie: Politisches System und politische Kultur in der Schweiz und in Österreich. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr.

- Lijphart, Arend. 1968. The Politics of Accommodation: Pluralism and Democracy in the Netherlands. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Lipset, Seymour M., and Stein Rokkan. 1967. “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments.” In Party Systems and Voter Alignments, edited by Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan, 1–64. New York: Free Press.

- Mader, Matthias, and Harald Schoen. 2019. “The European Refugee Crisis, Party Competition, and Voters’ Responses in Germany.” West European Politics 42 (1), doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1490484.

- McAdam, Doug, and Karina Kloos. 2014. Deeply Divided: Racial Politics and Social Movements in Postwar America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- More in Common 2019. “Die andere deutsche Teilung: Zustand und Zukunftsfähigkeit unserer Gesellschaft.” Berlin: More in Common.

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Poweleit, Julia. 2021. “Zivilgesellschaft in der Migrationsgesellschaft: Die Geschichte von ‘Asyl im Oberland’.” In Zivilgesellschaft in Deutschland: Aufbrüche, Umbrüche, Ausblicke, edited by Brigitte Grande, Edgar Grande, and Udo Hahn, 115–121. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Priemer, Jana, Holger Krimmer, and Anaël Labigne. 2017. Vielfalt verstehen. Zusammenhalt stärken: ZiviZ-Survey 2017. Essen: Stifterverband.

- Putnam, Robert D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Putnam, Robert D. 1995. “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” Journal of Democracy 6: 65–78.

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Putnam, Robert D., ed. 2001. Gesellschaft und Gemeinsinn: Sozialkapital im internationalen Vergleich. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Putnam, Robert D. 2007. “E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-First Century.” Scandinavian Political Studies 30 (2): 137–174.

- Putnam, Robert D., and Kristin A. Goss. 2001. “Einleitung.” In Gesellschaft und Gemeinsinn. Sozialkapital im internationalen Vergleich, edited by Robert D. Putnam, 15–43. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Rokkan, Stein. 2000. Staat, Nation und Demokratie in Europa. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

- Roose, Jürgen. 2021. Politische Polarisierung in Deutschland. Berlin: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung.

- Röpke, Thomas. 2021. Der Humus der Gesellschaft. Über Bürgerschaftliches Engagement und die Bedingungen, es gut wachsen zu lassen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Rucht, Dieter. 2017. “Rechtspopulismus als soziale Bewegung.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 30 (2): 34–50.

- Schattschneider, E. E. 1960. The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America. Hindsdale, IL: Dryden Press.

- Schiffauer, Werner, Anne Eilert, and Marlene Rudloff, eds. 2017. So schaffen wir das – Eine Zivilgesellschaft im Aufbruch. 90 wegweisende Projekte mit Geflüchteten. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Schroeder, Wolfgang, Samuel Greef, Jennifer Ten Elsen, and Lukas Heller. 2022. “Interventions by the populist radical right in German civil society and the search for counterstrategies, German Politics, Special Issue on “Civil society, social movements, and the polarization of German politics”, Advance Online Publication.

- Schroeder, Wolfgang, Samuel Samuel Greef, Jennifer Ten Elsen, and Lukas Heller. 2020. “Bedrängte Zivilgesellschaft von rechts. Interventionsversuche und Reaktionsmuster.” OBS-Arbeitsheft 102. Frankfurt a.M.: Otto-Brenner-Stiftung.

- Schwarzbözl, Tobias, and Mathias Fatke. 2016. “Außer Protesten nichts gewesen? Das politische Potenzial der AfD.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 57 (2): 276–299.

- Simonson, Julia, Claudia Vogel, and Clemens Tesch-Römer, eds. 2017. Freiwilliges Engagement in Deutschland: Der Deutsche Freiwilligensurvey 2014. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Skocpol, Theda. 2003. Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Steiner, Jürg, and Thomas Ertmann, eds. 2002. “Consociationalism and Corporatism in Western Europe: Still the Politics of Accommodation?” Special Issue of Acta Politica. Amsterdam: Boom.

- Vorländer, Hans, Maik Herold, and Steven Schäller. 2018. Pegida and New Right-Wing Populism in Germany. Cham: Palgrave.

- Vüllers, Johannes, and Sebastian Hellmeier. 2021. “Does Counter-Mobilization Contain Right-Wing Populist Movements? Evidence from Germany.” European Journal of Political Research, doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12439.

- Weisskircher, Manès, and Lars Erik Berntzen. 2019. “Remaining on the Streets: Anti-Islamic PEGIDA Mobilization and its Relationship to Far-Right Party Politics.” In Radical Right Movement Parties in Europe, edited by Manuela Caiani, and Ondřej Císař, Ch. 8. London: Routledge.

- Wuthnow, Robert. 1998. Loose Connections: Joining Together in America’s Fragmented Communities. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Youngs, Richard, ed. 2018. The Mobilization of Conservative Civil Society. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment.

- Zentrum Liberale Moderne. 2019. Sicherheit im Wandel: Gesellschaftlicher Zusammenhalt in stürmischen Zeiten. Berlin: Zentrum Liberale Moderne.