ABSTRACT

This study offers a contribution to the literature on access to justice and legal empowerment. It presents findings from qualitative empirical legal research and explores how obtaining access to justice contributes to conflict resolution. Fifty-four in-depth interviews were conducted with victims of domestic violence who had obtained access to the Public Prosecutor’s Office of the City of Buenos Aires (Argentina) with a domestic violence complaint. The study found that these victims benefitted from obtaining access to justice even when this did not directly achieve resolution of their conflict. The benefits were related to the actions taken by legal organisations contributing to their own perceptions of being agents capable of making decisions.

Introduction

Victims believe that when they obtain access to justice someone will solve their problems (Genn Citation1999). They soon learn however that they have started on a pathway which includes unexpected tasks and choices. The study reported here presents results from a qualitative empirical legal research study comprising in-depth interviews with victims of domestic violence (hereinafter, Victims) who had obtained access to the General Prosecutor’s Office of the City of Buenos Aires (Argentina) between June 2013 and January 2014. This study explores how obtaining access to justice contributes to conflict resolution through legal empowerment; taking an explanatory and deductive approach, relying on qualitative methods. It suggests that justice systems need to invest in mechanisms that enhance effective communication with Victims during the legal process. Access to justice was not found to translate into conflict resolution, even though the courts enforce rights. However, there were positive consequences of obtaining access to justice related to the actions of organisations, which contribute to the empowerment of Victims and their self-perceptions of being agents capable of making decisions in the search for conflict resolution.

Review of the literature

National surveys show that within a three–year period between 37% and 67% of low and middle–income people experienced one or more problems with legal connotations considered difficult to solve.Footnote1 The results of those surveys enabled countries, for the first time to understand, with empirical evidence, the relationship between people, legal problems, and the justice system. The surveys looked at the paths people follow to resolve the problems, the type of legal services available, and at awareness before and perceptions after the interaction with the justice system (Barendrecht, Kamminga and Verdonschot Citation2008, Pleasence et al. Citation2004, Currie Citation2006). This line of research can be traced back to the volume edited by Mauro Cappelletti and Bryant Garth entitled ‘Access to Justice’ (Citation1978) which recognised the importance of considering the social dimension of access to justice by answering a question: justice for whom? This line of work also explores ways of achieving equality in justice and considers legal organisations as organisations created by modern societies to tackle lack of access to justice for those in need (Cappelletti et al. Citation1975, p. 77–132).

Access to justice

The justice system, through the design and implementation of legal organisations, is presumed to help individuals to find remedies. In the past, access to justice was considered to be obtaining access to courts. In the last ten years, however, access to justice has been seen in a broader sense, representing the fundamental right of people to seek and be granted justice (Macdonald Citation2010). Hence, justice can be granted by different mechanisms, not only through traditional access to courts (Macdonald Citation2010, p. 503–9). Innovations in different mechanisms for access to justice aim to achieve access for all, eliminating common obstacles faced by vulnerable groups, such as victims of domestic violence (Wojkowska and UNDP Citation2006). The theory developed to include this inclusive aspect stated ‘access to justice exists if people, notably poor and disadvantaged, suffering from injustices, have the ability to make their grievances be listened to, and to obtain proper treatment of their grievances by state or non-state institutions leading to redress of those injustices’ (Bedner and Vel Citation2010, p. 7).

Different attempts are being made at innovation in the form of legal organisations for victims of domestic violence. Factors such as specialisation of tribunals or legal organisations, proximity to the geographical area where problems take place, and familiarity with the targeted population have shown to have a positive impact on obtaining access to justice and conflict resolution (Scott Citation1958, Genn Citation1999, Pleasence et al. Citation2004, UNDP and Douglas Citation2007). Consequently, legal organisations have been created to assist people in accessing the justice system and exercising their rights. These legal organisations, mostly known as legal aid offices, first appeared as part of state policy in Europe and North America in the 1970s (Cappelletti et al. Citation1975, p. 29–76) and required allocation of considerable resources (Barendrecht et al. Citation2006). Most legal organisations rely on state resources; and budget cuts and political preferences in the past have jeopardised their capacity to assist the vulnerable population.

The legal empowerment approach offers a way of understanding access to justice that places the individual at the centre (Golub Citation2003, Bruce et al. Citation2007, Macdonald Citation2010). Legal empowerment considers legal provisions and legal organisations as tools for empowerment and trusts in their power to enhance the capabilities of individuals to overcome conflict. Research to understand and measure legal empowerment has gained momentum since the 2000s (Bruce et al. Citation2007, p. 1, Golub Citation2010, p. 2). Legal empowerment relies on the concept of equal access to and use of the law; and rests on the legal principle that ‘all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’ (Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor 8AD: 4). Legal empowerment is connected to the improvement of the situation of the poor using legal remedies in the form of legal provisions and legal organisations (Gramatikov and Porter Citation2010, p. 5–6).

The legal empowerment approach, in addition, considers the acquisition of decision-making power through access to information and assistance providers. For example, in the UK, 31% of the people who took action to solve their legal problems experienced ‘a sense of empowerment’ and reported that a feeling of satisfaction was derived from the enforcement of rights (Genn Citation1999, p. 193). The wider the gap between a powerful party and a non-powerful party, the greater is the need for external assistance to empower the latter (Gramatikov and Porter Citation2010, p. 4–5). Providers working for legal organisations are perceived as having the capacity to empower those who access the justice system by explaining how to deal with legal situations and how to avoid further legal problems (Barendrecht Citation2010).

Ownership of conflicts

Hazel Genn found that people at an early stage want to ‘know how to solve their problems’ (Citation1999, p. 95) but in the end what people want is not to be empowered but ‘to be saved’ (Genn Citation1999, p. 100). Nils Christie argues further that most people are willing to pass their conflict on and that lawyers are willing to take the conflict away from people (Citation2010, p. 6). People hence look at the justice system as the institution that will take over their conflicts and propose a solution to them. However, Christie claims that ‘ownership’ of the legal problem should stay with the person who seeks help from the justice system. He claims that this is the only approach to conflict resolution that allows people to indeed solve their problems. Moreover, there is an assumption that vulnerable groups do not have the social power to improve their life conditions (Friedmann Citation1992, p. 57–58, 66). Yet the empowerment model of John Friedmann contemplates the use of ‘local units of governance’, not to plan for the vulnerable, but to empower them (ibid. 1192: 35–36).

Christie takes a criminological perspective and criticises justice systems that separate victims from their conflicts (Citation2010). He proposes a system that enhances the participation of the parties. Therefore, legal provisions that offer real chances and options for people to participate in the resolution of conflicts are perceived as contributing to actual resolution. Examples are to be found in the mechanisms of alternative dispute resolution (Christie Citation2010, p. 24–25, 27, 36, Van De Meene and Van Rooij Citation2008, p. 10–11, 15–16). These mechanisms broaden the spectrum of possible ways for parties to achieve conflict resolution through a tailor-made remedy (XIV Ibero-American Judicial Summit Citation2008). Moreover, they stress the importance of the quality of providers in understanding the vulnerabilities of certain groups to their ability to enhance those groups’ participation in the process (XIV Ibero-American Judicial Summit Citation2008: para. 47).

A restorative justice approach to conflict resolution uses tools that enable the participation of parties in the process, primarily the offender (Shapland et al. Citation2011, p. 3–4). This approach strengthens (and trusts in) the responsibility of parties to overcome the conflict and the harm produced. Empirical research shows that ‘restorative justice may have potential for reducing crime and [that there is] quite convincing evidence that citizens who experience restorative justice as victims, offenders and participants, perceive it to be fairer and more satisfying than courtroom justice’ (Strang and Braithwaite Citation2002, p. 3). On the one hand, restorative justice reinforces the role of victims in the process, not limited to their role as witnesses, but incorporating alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. On the other hand, restorative justice searches for conflict resolution, looking at repairing the harm caused to victims and not just the punishment of the offender (UN Secretary General Citation2002: para. 16). Studies also show a decrease in the probability that the offender will re-offend when parties experience a restorative justice legal process, using alternative dispute resolution mechanisms (UN Secretary General Citation2002: para. 4). Restorative justice considers, however, that parties are not to be exposed to risk when searching for remedies, and this element serves as the main argument for excluding domestic violence from this approach.

Empirical studies of the effectiveness of restorative justice to resolve conflicts have excluded domestic violence from their experiments. It is argued that the power imbalance between parties makes the search for a common agreement biased, and that the encounter at legal organisations between victims and abusers may increase the risk of harm (Shapland et al. Citation2011, p. 83). Moreover, studies consider that the process proposed by restorative justice implies the voluntary participation of victims, something that is often missing (Drost et al. Citation2013, p. 8). Theory suggests, however, that the probability of re-offending diminishes if the offenders believe they experience a fair process (Sherman Citation2000, p. 281–84). The restorative justice approach to domestic violence issues is starting to be considered suitable when it adapts to the risk and power imbalance that characterises these conflicts (Ptacek Citation2009, p. 281–85, Drost et al. Citation2013).

Methodology

Interviews, observations, and documentary analysis facilitate in-depth understanding of experiences and behaviours of users of the justice system. These methods in addition allow for an understanding of certain phenomena by the actors (Hesse-Biber and Leavy Citation2010, p. 6–7, 33, and 42) and have been used to obtain ‘in-depth information about behaviour, decision-making and motivation, permitting a more detailed tracing of the process through which disputes were handled’ (Genn Citation1999, p. 18, Citation2009).

Data collection and sample

The Public Prosecutor’s Office of the City of Buenos Aires (hereinafter, Public Prosecutor’s Office) is used in this study as an example of a legal organisation that intervenes in the legal empowerment of individuals who obtain access to justice. The office does not have a defined goal to legally empower victims, but to assist them in the process.

The data was collected at the Victims and Witness Assistance Office, a multidisciplinary office that is mandated to offer immediate intervention in domestic violence cases which access the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Domestic violence cases are defined as crimes of ‘threat’ and contraventions of ‘harassment’ against a person with whom an intimate relation exists or by another family member (Criminal Code Citation1984: art 149bis; Contravention Code Citation2004: art 52). The Public Prosecutor’s Office of the City of Buenos Aires is part of the City Attorney Office (Convención Constituyente Citation1996: art 107).

Data collection took place during three separate points in time (Period One, Period Two, Period Three, see ). This technique was inspired by a similar method used in a previous study by Janet Walker (Walker et al. Citation2007, p. 23–29), to track the experiences of Victims before and while they had access to the justice system. It was not possible to have a control group in the present study due to the difficulties in finding a sample of Victims who had not submitted complaints. This study therefore follows Victims who obtained access to the Public Prosecutor’s Office during a six-month period in order to be able to capture how their relation to the conflict developed as they passed through the legal process. The first interviews were carried out over a period of 43 days for each Victim who had an appointment there and who agreed to participate in the study. An equal amount of time was spent in each of the decentralised units, covering the five days of the working week at each unit. Fifty-four Victims were interviewed once (first interview) and 31 again after a six-month interval (second interview). We also interviewed representatives of the Victims who approached the Public Prosecutor’s Office and agreed to participate in the interview. We did not control for, for example, gender, age, education, income, see .

Table 1. Research stays

Table 2. Sample characteristics

Data collection

The interview questions were open-ended and not leading. Triangulation of data was achieved by validating the interviews with the legal documents of each Victim and also with our observation notes (Padgett Citation2008: chap. 8). Interviewees became the source of data for this study in their capacity of experts in the topics inquired into (Hesse-Biber and Leavy Citation2010, p. 42), and were selected because they hold the information needed to answer the research question. The aim was to learn from their experiences; therefore, special care was needed to avoid leading the conversations, and responsive interviewing techniques were used (Rubin and Rubin Citation2012, p. 152–200).

In Period One, we took observation notes during meetings between members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and Victims. These notes helped our understanding of the characteristics and vocabulary used by Victims. A questionnaire was developed from this information containing closed questions and a set of open-ended questions to be used in the first in-depth interviews.

In Periods Two and Three in-depth we used interviews with open-ended questions, and in Period Three the interview also included a questionnaire that repeated the structure of the one conducted during Period Two. During Period Three, a set of specific questions was also developed for each Victim with aspects to follow-up from first interviews. Lastly, we complemented the data collected with legal documents available in the electronic file at the Public Prosecutor’s Office. These documents showed the actions taken in each case inside the justice system.

Thirty-one out of the fifty-four Victims who agreed to the first interview at the Public Prosecutor’s Office also took part in the second interviews (Period Three). Most of these second interviews were conducted over the telephone, to avoid asking Victims to travel to the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Observations and fieldwork notes were also used to track contextual information, perceptions, and the main lessons learned. Fieldwork notes were also used to prepare for future interviews, and to analyse and triangulate data.

Data analysis and validity

Data analysis used a content analysis approach in this study (Graham R Gibbs; Oppenheim Citation1992, King et al. Citation1994, Rubin and Rubin Citation2012). Interviews were thematically coded by both pre-selected categories and categories that were created during the process of coding (Webley Citation2010, p. 941–42). The study followed a deductive approach at the beginning, using main codes or themes that derived from the literature on access to justice, legal empowerment, and conflict resolution. The study later followed an inductive approach that led to new codes that derived from the data. Moreover, the analysis of data considered the importance of certain words in the discourse of interviewees, the interaction and contradiction between different factors as presented by interviewees, and the enumeration of elements considered to be relevant for certain topics. NVivo was used to analyse the data systematically. It served as a tool to retrieve different codes and analyse them at different stages in the study. Furthermore, personal attributes of the interviewees, such as age and place of birth (see ), were linked to some codes in order to relate the findings to their characteristics.

Possible ambiguity in findings was reduced by using triangulation techniques between different sources of data (Wolcott Citation2008, p. 26, Padgett Citation2008: chaps. 5, 8). The three fieldwork periods assisted validation of the information. In addition, during those periods we were given a physical space at the Public Prosecutor’s Office to prepare for the interviews, work on observation and fieldwork notes, and access the legal documents in the legal files of Victims. Staying in the office helped us engage with service providers in a colloquial way. This facilitated a deep understanding of the dynamics of what was taking place at the offices and the population they serve. Moreover, the prolonged contact with the same Victim at two different points in time also assisted in validating the data. In addition, the main findings were shared in an oral presentation at the Public Prosecutor’s Office attended by service providers.

This study took care in respect of reliability by referring to all interviews in detail and in an anonymised way. Hence, it is possible to observe throughout the study references indicating the sources from which information was taken. NVivo helped to facilitate this process.

Ethical considerations

An agreement for collaboration was signed between the researcher’s institution and the Public Prosecutor’s Office. All interviewees were informed of the objectives of the study and were asked for their consent to participate. Interviewees were informed of confidentiality and anonymity rules and given an explanation about the exclusive use of the data for the purpose of this study. The anonymity of interviewees is preserved with the elimination of names and the allocation of codes composed of the letter V (for Victim), the number 1 or 2 (for first or second interview), and a number to distinguish amongst different Victims (for example, V1, 001). Furthermore, interviews between service providers of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and Victims are identified with the letters IwSP.

The vulnerable condition and stressful situation of Victims demanded special consideration. Victims were reminded and asked for consent at each stage of the interview process. While undertaking second contacts, Victims were reminded again of the purpose of the study. Moreover, the questionnaires and interview guides used to collect data from Victims were shared with psychologists from the Public Prosecutor’s Office to ensure that Victims were not harmed or re-victimised. Special attention was given to avoid taking Victims to places that could cause them harm, and all questions were limited to the experience of Victims with access to justice and not with the violence experienced.

Limitations

The method used to collect and analyse data relied to a certain extent on the decisions we made. Sharing the research design with experts and colleagues helped to test decisions made throughout the process. The six-month interval between interviews and the questions related to the paths followed by Victims to obtain access to justice and to decide to submit complaints were used to overcome this limitation. The incorporation of open-ended and non-leading questions served to reduce bias. The use of responsive interviewing techniques assisted us in working with interviewees as conversational partners, and probing served as a technique to deepen aspects that were more surprising.

Results

Experiences of victims

Submitting complaints was expressed as a clear manifestation of a desire for change. Most Victims experienced it as a moment where they gained control over their lives, which gave them a sense of self-confidence in their capacity to change. Victims also witnessed how others perceived the reality that they were living, feeling reassured of their decision to end with the violent relation. As mentioned by one interviewee:

How did you feel after submitting the complaint?

I liked it a lot, because it surprised me.

It surprised you?

Yes. It surprised me that it came out that way. And it made me feel more confident [about myself], and about what it was that I wanted.

In which sense you felt ‘more confident’?

In my decisions. Up to here I tolerate, up to here I do not. This I can stand, this I cannot.

It is as if it gave you more confidence to make decisions or more confidence in saying ‘this I want, this I do not want’?

Both, because submitting a complaint implies also making a decision (V2, 051).

Victims were asked about the changes they noticed in themselves immediately after submitting the complaint (first interview), and after six months (second interview). Victims expressed changes in terms of positive and negative feelings, developments in their complaints, and the health of the accused. Only a few Victims expressed comments in terms of enforcement of rights.

Victims who expressed positive feelings talked about: (i) tranquillity (mentioned by 14 Victims)Footnote2; (ii) trust in own capacity (mentioned by 14 Victims)Footnote3; and, (iii) support (mentioned by five Victims).Footnote4 While Victims who expressed negative feelings talked about: (i) feeling bad (mentioned by six Victims)Footnote5; (ii) nervous (V1, 004); and (iii) afraid (mentioned by eight Victims).Footnote6

Victims who expressed a feeling of tranquillity after submitting complaints related tranquillity to a chance to perform ordinary activities, enforce rights, live by themselves and feel safe in and outside their houses, overcome the situation, begin the search for change, or receive help and solve problems. However, this group viewed delays in the justice system as an obstacle to that feeling of tranquillity.

Victims who expressed tranquillity as a feeling that was regained during the legal process can be divided into those who ended the violent relationship and those who continued living with the accused. Those who ended the relationship related the feeling of tranquillity to having been able to solve the entire problem and to have the chance to live in peace, or to having been able to solve some aspects of the problem with the support of the judicial system. Those who continued living with the accused related the feeling of tranquillity to having been able to gain control over problems by understanding the roots and their responsibility (such as alcohol addiction), learn how to handle abusive situations, or become aware of the assistance providers to turn to for help if something happened.

Another group of Victims said that submitting the complaints allowed them to gain trust in their own capacity to handle problems. This trust in their own capacity was mentioned during first and second interviews by different Victims. Trust in their own capacity related to receiving instructions from providers and psychologists on how to communicate with the accused; being more patient in the process needed to solve their problem and becoming aware of the complexities of the legal process.Footnote7 Additionally, trust in their own capacity also related to persevering in requesting a response from organisations, being able to talk and express their own desires and gain strength to place limits on the accused, or being able to understand their own reality and change accordingly.Footnote8

The feeling of being supported and protected; you believe that you are more protected (V2, 047), was mentioned by a group of Victims as the main effect of submitting complaints. This feeling was related to being heard and to knowing that there were places available to seek help, such as specialised legal organisations (V1, 022; V1, 023; V1, 024).

As a pattern, Victims who related submitting a complaint to a feeling of tranquillity manifested an action of which they were a part. Most Victims who spoke in terms of trust related the feeling to an internal process of self-assurance, and a number of Victims related it to the manifestation of an action. Becoming involved in the process is shown to be an element leading to positive feelings, and active listening by providers enhanced participatory behaviour.

Some Victims felt bad, afraid, or nervous as a result of their complaints. Those who felt bad when submitting complaints related that feeling to exercising a legal action against a loved one (V1, 014; V1, 015; V1, 026). This result was not surprising given the target group. After six months, another group of Victims admitted to having a constant feeling of fear, in and outside their homes (mentioned by five Victims).Footnote9 As a reaction to that fear they described taking security precautions, such as being more careful when going in and out of their homes and work places (V2, 006), or being more alert to other signs of potential risks to their safety (V2, 041).

The expectations of victims and caveats

When Victims submitted complaints they immediately expected that the action would trigger: (i) a warning to the accused (V1, 021; V1, 032); (ii) a motivation for change in the behaviour of the accused towards themselves or their children (mentioned by eight Victims)Footnote10; (iii) a good solution to their problems (V1, 006); and (iv) a way to receive protection to make possible the performance of another activity (V1, 053). At that moment few Victims lacked expectations (V1, 022) or were sceptical (V1, 022; V1, 030) of the effect of the complaint in solving their problems. However, Victims became surprised by the amount of participation they had to take in the legal process after submitting the complaint. They expected that the legal process was about submitting a complaint and nothing else, that he would get notified and be told how he needed to behave (V1, 037; V1, 021).

Expectations changed as Victims experienced the legal process. They started to perceive themselves as the party that takes the main bureaucratic burden: you are called 35,000 times but [they do] not [call] the other person (V2, 019). This created doubt in the efficiency of the justice system to solve their problems in the near future. Hence, some Victims decided to try other means to find solutions, such as visiting psychologists or personally performing judicial administrative tasks to accelerate the process, such as notifying the accused themselves instead of waiting for the police to do so (V1, 043; V1, 024; V2, 006).

Furthermore, some Victims explained that the combination of requests (such as complying with appointments at the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the court) and other personal obligations (such as doctors’ appointments) pushed them towards abandoning their complaints (V1, 002). After six months, a group of Victims expressed frustration for the number of activities they had to perform in order to comply with the judicial requests that resulted from their complaints. They stopped attending appointments (V2, 001; V2, 043; V2, 045), delayed the legal process (V2, 033; V2, 052; V2, 006; V2, 012), or solved their problems only partially (V2, 039; V2, 041).

At this point in time, the expectations of Victims and the reality of the legal process started to move in opposite directions. Some Victims became inactive, and felt happy on receiving a call with a concrete option for a solution, for example, a mediation (V2, 006, V2, 034). Others decided to comply with judicial requests without understanding how these requests were connected to solving their problems (mentioned by seven Victims).Footnote11 Others solved their problems because the accused stopped the offence while the legal process remained open (and they did not know that the legal process was still open).

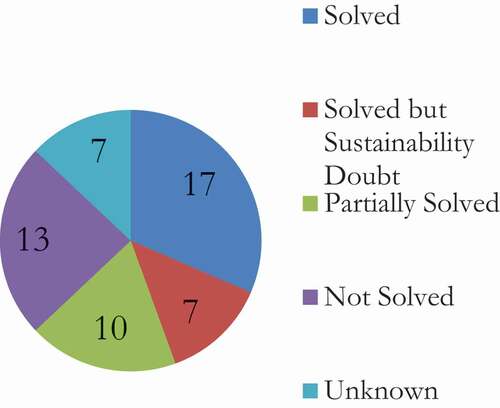

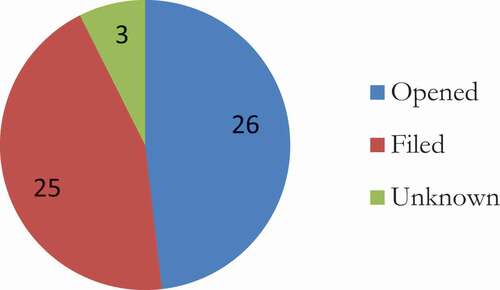

This study, consequently, compared what Victims said about the status of the problem that triggered the complaint and what the legal documents in their files at the Public Prosecutor’s Office stated about the status of their cases. There is discrepancy between the perception of Victims of having their problems solved, and the decision of the Public Prosecutor’s Office to file the case (see ).

Relationship with organisations

There were benefits that Victims experienced when obtaining access to justice even when this access did not directly resulted in the resolution of their conflicts. The quality of the service provided and the appropriate understanding of needs made a difference to the way access to justice was experienced. Victims however rarely distinguished between the service provided by one organisation or another (V1, 021; V1, 036; V1, 044; V1, 022).

In general, activities taken by organisations, such as follow-up calls, active listening, and plain language, did make Victims feel supported (mentioned by five Victims),Footnote12 protected (V1, 015; V1, 034; V1, 051), confident (V1, 027; V1, 042; V2, 039), and reassured in their decision to pursue complaints (V2, 043). Likewise, organisations that remained active were considered efficient (V2, 037; V1, 045). Follow-up calls in particular reassured Victims as to the importance of their case.Footnote13 They gave Victims a feeling of trust in the help they might receive from organisations, and for some Victims the calls even gave them an incentive to continue with their complaints.Footnote14 In this process, Victims realised that they have a socially acceptable option that can be used to overcome their problems. However, the multiplicity of organisations becoming involved in cases created confusion.

Victims appeared to perceive the support of organisations when they felt heard and had the opportunity to express themselves in a private, quiet room. In comparison, Victims felt they were not being supported when they experienced long waits and multiple referrals, excessive telephone calls, and calls received at a time of the day when they were busy performing other activities or obligations (mentioned by seven Victims).Footnote15 The type of questions and ways in which meetings were conducted were important for the confidence of Victims. Questions that had an inquiring rather than believing connotation (for example, But, do you have any injuries? V1, 045; Are you hit? Did he hit you? V1, 048) were mentioned as a reason for the experience with an organisation being seen as negative.

Legal terminology was also mentioned as an obstacle to effective communication. Technical words such as mediation and probation, together with the names of organisations, were not always remembered by Victims. Sometimes they were associated with the time of the year when the events occurred, or by the physical addresses of organisations (for example, referring to mediation as the option of September, V1, 13).

Legal terminology showed itself to be foreign and abstract to most Victims. As two Victims expressed in relation to different legal words,

Referring to the additional research she had to do in order to understand the legal process: And we add all the bureaucratic terminology of ‘restraining,’ ‘solution,’ ‘measures,’ you have no idea what it all means, until you need to understand [because it is part of the terminology of the problem] (V2, 034).

Referring to the calls with the Public Prosecutor’s Office when the stage of the legal process was explained to her: They gave me the feeling that they were speaking very fast, they gave me little information, and they spoke about ‘probation,’ ‘probation.’ At that stage they did speak difficult ‘and that probation, and if not we go to trial.’ My head was a little messy, I did not understand much (V2, 050).

Moreover, Victims expressed difficulty in understanding the terminology and the purpose of written notifications. A Victim explained,

It is difficult when receiving notifications. You do not understand what they are for, if you have done something wrong. And, if the notification says what it is for, it is still difficult to understand the vocabulary because it uses difficult terminology. … In these situations I call my lawyer (V2, 019).

Another Victim elaborated on the written notifications she received and stated that they represented a materialisation of the decision she had made which led to a deeper assimilation of her problem (V2, 039). Moreover, some Victims still perceived the legal terminology as a label of seriousness. For example, the same Victim who felt lost with understanding the meaning of the legal term ‘probation’ explained that when she was called and informed that there was a hearing scheduled she realised that it was not acceptable to be harassed (V2, 050).

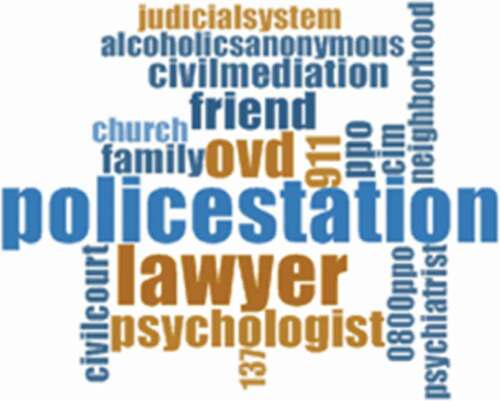

During the last ten years, the City of Buenos Aires experienced an increase in the number of legal organisations that assist victims of domestic violence. Those visited most often by Victims are the Public Prosecutor’s Office, Office of Domestic Violence, and the Access to Justice Offices, and Comprehensive Centres for Women. The creation of these organisations offered Victims new options to demand rights beyond the traditional fora (courts) and to receive comprehensive assistance, but it also confused Victims as to who did what.

The number of actions taken by the number of organisations involved became an obstacle to understanding which aspects of the problem were being taken care of by each organisation. Furthermore, the intervention of different organisations often triggered other paths with tasks (such as counselling) and few Victims understood the reasons why this accumulation occurred. Some Victims, nevertheless, appreciated having multiple organisations. They remarked positively that after submitting their first complaints they realised they had many ways to seek help besides going to a police station (V1, 006).

The solutions provided by legal organisations to Victims could however sometimes trigger additional problems. For example, a Victim was sent to a welfare shelter with her two children due to the severity of the violence she had experienced and said that being in the welfare shelter became a problem because she quarrelled with others there, and the psychologist wanted to make her believe she was crazy (V1, 007; V2, 007). Another Victim explained that after the accused left she started experiencing economic constraints and had to move with her children to the house of her mother (V1, 011). She mentioned needing to hire a lawyer to deal with child support even though this would imply allowing visitation (V1, 011). Another Victim explained needing to request custody in order to avoid future problems (V1, 015). Lastly, a Victim expressed that the domestic violence complaint was not the best option to handle the alcohol addiction of her partner (V1, 030).

As the legal process moved forward some Victims started facing new problems unrelated to domestic violence. These Victims indicated that it became even more difficult for them to follow the domestic violence complaints because legal processes consisted of non-demanding periods and very demanding periods of time (V2, 052). Very demanding periods could not be anticipated and hence when the demands occurred Victims could have been also be handling other important problems, which led them to be unresponsive or feel stressed (V2, 052). Under these circumstances, Victims skipped appointments or requested rescheduling of appointments, thereby prolonging the legal process.

Access to organisations seemed to help Victims to remember and to learn where they had reached with their problems. Some Victims started to become aware of their capacity to resolve their problems, instead of simply accepting them. Therefore, even when a solution to their conflicts was not provided, the access in itself could have an empowering effect. Organisations could strengthen this effect by investing in mechanisms that enhance effective communication during the legal process.

Reaching out for assistance

This section offers further evidence about the type of assistance that Victims valued. Victims were seen to follow advice, referrals, or their own intuition when reaching out for assistance. The police station, lawyers, the Office of Domestic Violence, psychologists, and friends were the assistance providers most frequently mentioned as having been approached by Victims (see ).Footnote16 The Office of Domestic Violence and the Public Prosecutor’s Office were, in most cases, organisations that were contacted after a referral. Police, lawyers and psychologists were assistance providers who were approached mainly after recommendations. In this study, Victims were asked about what they recalled from their experience with different assistance providers.

Police stations

Our interviews indicated that police stations were present in the social consciousness as the place to go, and Victims showed themselves to have difficulties memorising the names or contact information of the other places available for submitting complaints or seeking assistance. A Victim explained, while talking about her decision to go to a police station,

And did you happen to go to another place before?

No, I thought directly about submitting the complaint at the police station.

And why was that?

Because it is where complaints are received.

Okay. And, where did you learn that? From experience? Or someone told you?

That is the way it is. That is to say, at the police station is where complaints are received [laughs] (V1, 022).

Even in cases where Victims were not happy with the assistance received at police stations, and knew of other available options, when asked where they would seek help if another event occurred, the answer was often: The police (V1, 024). The reasons mentioned by Victims as to why they selected the police station as the access point were related to the following factors: (i) it is the place where complaints are received (mentioned by seven Victims)Footnote17; (ii) it is located close to their housesFootnote18; and (iii) it is a neutral organisation without adding an emotional element. Victims who decided not to use the police station as the access point explained that in their neighbourhoods, police stations were not an alternative because they did not provide effective options, there were long waits, and they provided wrong referrals (V1, 015).

Lawyers

Victims who had a lawyer did not show, in general, a better understanding about what was going on in their complaints. On the contrary, complaints seem to be left in the hands of their lawyers, and Victims referred to the main updates in their complaints in the same terms as they were explained by their lawyers (mentioned by 12 Victims).Footnote19 Other Victims explained communicating frequently with lawyers about updates in order to decide how to proceed (mentioned by six Victims)Footnote20 and mostly did what was recommended by their lawyers (V1, 017; V1, 022; V1, 042). Some Victims in that group were asked during second interviews about how things were going, and they replied that they needed to call their lawyers to request an update (V2, 015; V2, 017; V2, 044).

Lawyers were on some occasions mentioned as necessary partners to start a fight (V1, 016; V1, 044). For example, a Victim explained, He has a lawyer and I do not have mine. I needed to go to sign. I was given a lawyer, but because I did not sign they [ultimately] did not give me one (V1, 016). Some Victims perceived a disadvantage during mediation or the legal process because they were by themselves while the accused had a lawyer (V1, 028; V2, 028; V–IwSP, 048). The Victim who reported being qualified as a lawyer specialist in domestic violence also confirmed that there was a significant difference in the way Victims were received and taken care of when they approached courts by themselves and when they did so with a lawyer (V1, 032).

Lawyers were therefore considered actors capable of understanding what was going on and able to communicate with organisations.Footnote21 Lawyers projected in Victims a feeling of reassurance (V2, 037; V1, 041; V1, 045), support (V1, 045; V2, 049), speed and security because they helped avoiding meeting with the accused (V2, 053).

Money and time were mentioned as obstacles to hiring a lawyer. The cost of hiring lawyers was not mentioned as an impediment (V-Q, 004; V1, 003), but it was seen as a heavy economic burden. These Victims explained this as having to sacrifice ways of using their money, agreeing on a payment in instalments,Footnote22 or delaying the representation until they were able to handle the costs (mentioned by six Victims).Footnote23 Other Victims hesitated calling back to their lawyers, since payment for previous services was still due (V–IwSP, 004; V–IwSP, 005), and so ‘borrowed’ the lawyer of a friend who had the ability to pay (V1, 037), or borrowed money from family members to pay for legal services (V1, 044).

Time is another factor mentioned as an impediment to continuing a civil case with a lawyer (V2, 039). A Victim explained having too many responsibilities with [her] children and work (V2, 039) to be able to continue her case with her lawyer.

Psychologists

Referrals by organisations to psychologists were mentioned by some Victims who activated those referrals as an important emotional support on how to handle problems, how to improve their quality of life and how to understand behaviour (mentioned by nine Victims).Footnote24 Some Victims did not feel convinced of the benefits of approaching psychologists, and others mentioned going or considering going to psychologists because it was a step they needed to take (V–IwSP, 009) or because they were pushed to go (V2, 001; V2, 012). Other Victims were taking psychological therapy before the submission of complaints and considered the therapy useful in coping with the legal process (V–IwSP, 019; V1, 028; V1, 043; V1, 044).

A group of Victims considered it important that their children attended psychological therapy in order to overcome the violence experienced, and so as not to repeat it (V1, 004; V–IwSP, 004; V–IwSP, 026; V–IwSP, 031). Two Victims gave up their therapy in order to afford therapy for their children (V–IwSP, 026; V–IwSP, 031). Group therapy was considered helpful by one Victim (V2, 017), since it allowed sharing personal experiences with peers and to reassure them about decisions and encourage persistence.

Contextual support

All Victims but two indicated in their complaints having support from a social network, which included family, friends, and colleagues.Footnote25 These numbers might be saying something about the characteristics of Victims who submit complaints in the City of Buenos Aires: that most have affectional and contextual support.Footnote26 Some of these Victims expressed having a social network to rely on during first interviews, yet during second interviews that support was no longer present.Footnote27 On the contrary however, one of those Victims described strengthening the relationship with her family between the first and second interview.Footnote28

Socially accepted organisations, physical proximity, neutrality, effectiveness in the service provided, effectiveness in the manner of communication, equal opportunity to participate and voice their position, speed and emotional and unconditional support were mentioned as the characteristics that contributed to the decision to use assistance. These elements are suggested to be considered when evaluating organisations assisting victims of domestic violence.

Awareness of rights

Some Victims recalled previous exposure to information about domestic violence and the organisations available for help. Additionally, previous experience with the justice system was reported as increasing the feeling of owning responsibility in the search for a solution. Moreover, Victims who obtained access to justice expressed sharing the information they received with other women facing domestic violence. Consequently, the information that Victims receive before obtaining access to justice may become relevant to their decision to submit a complaint and to participate in the legal process.

For example, a Victim recalled hearing about domestic violence almost seven years before she experienced it herself, when she participated in some meetings organised by her sister and friends to talk about gender violence (V1, 017). A different Victim expressed learning about the existence of the Office of Domestic Violence in a seminar some years ago and during a visit to the hospital after being physically abused, though on both occasions the Victim ignored the organisation at that time (V1, 048). Experiences shared by other Victims and the actions they took to overcome the situations offered other examples of exposure to information prior to submission of complaints. Victims also recalled anecdotal information; for example, hearing of the existence of a lawyer who could help her some time ago in an elevator located in the building where her lawyer had an office (V1, 008).

This sample gave some hints leading us to believe that efforts towards awareness of rights can have an impact in the short term and in the long term. Moreover, the repetition of legal information provided to Victims seemed to be beneficial for the process of reassurance of their decision to submit complaints.

Closing remarks

In this study, most Victims expressed a feeling of confidence at the time they submitted complaints against the accused. Some Victims gained, when submitting complaints, their first perceptions of their own capacity to make decisions for themselves. Treating the justice system as a magic wand that will solve problems is a misleading approach to access to justice. A number of Victims immediately started exploring other organisations or withdrawing their cases when realising the demands of the justice system. However, this study shows that there were benefits that Victims experienced when obtaining access to the justice system even when not directly resulting in the resolution of their conflicts. Those positive elements were related to instances of participation where Victims experienced gaining ownership of their problems.

This study shows that access to the justice system can increase the perception Victims have of their chances to achieve a change. The value of conflict resolution for Victims is not in the enforcement of a penalty but in the support Victims receive from the justice system as a sign of care and support. These Victims considered the quality of the assistance provided and the quality of the communication relating to the enablement of conflict resolution to be important. The quality of the assistance provided can be measured by the actions performed by organisations that are then interpreted by Victims as symbols of care, support and protection, and they can trigger confidence and self-awareness. A reasonable number of follow-up calls, actions, active listening during meetings, and a proper physical space for interviews are mentioned as a sign of quality of assistance. Judgemental assistance, lack of commitment and long waits before being assisted represent aspects of low quality in the assistance. For some Victims those negative aspects motivated their decisions to discontinue with the use of those specific organisations.

A legal empowerment approach to access to justice assumes that obtaining access to the justice system does not necessarily mean obtaining a resolution of conflicts. The approach rather assumes that a justice system could contribute when parties become the main players in the search for resolution, and advance in the understanding of their rights and in the means available to enforce them. This study suggests that for that to be possible, the justice system needs to further invest in mechanisms that enhance effective communication with Victims during the legal process. Ultimately, the justice system can contribute to the empowerment and the self-perception of Victims as agents capable of making decisions to resolve their conflicts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. England and Wales 34% (Genn Citation1999); US 50% (Research and Public Citation1994); the Netherlands 67% (van Velthoven and ter Voert Citation2004); and New Zealand 51% (Maxwell et al. Citation1999).

2. V1, 008; V1, 017; V1, 025; V2, 006; V2, 017; V2, 021; V2, 027; V2, 029; V2, 035; V2, 037; V2, 038; V2, 039; V2, 047; V2, 054.

3. V1, 008; V1, 013; V1, 017; V1, 016; V1, 024; V1, 028; V1, 030; V2, 026; V1, 027; V2, 045; V2, 052; V2, 027; V2, 047; V2, 051.

4. V1, 022; V1, 023; V1, 024; V2, 037; V2, 045.

5. V1, 014; V1, 015; V1, 026; V2, 023; V2, 029; V2, 044.

6. V–IwSP, 012; V1, 020; V2, 006; V2, 015; V2, 034; V2, 041; V2, 050; V2, 052.

7. V2, 052 (the Victim said, ‘Because the justice system is not always what it seems to be. For example, I thought that the justice system would be straight and direct and do everything fast’); V1, 024; V1, 028.

8. V1, 016 (the Victim said, “I received some instructions, that is where I got the space to become aware of my own reality, … for me it was the same as the previous years, but then when I came to Lavalle [i.e. referring to Office of Domestic Violence], when I submitted the complaint I told them ‘well this is my life.’ And there I was told to look for places where I really feel good, that I need to feel good with myself. Because the life that he offers me is not good. So that is what I had in consideration to say ‘No.’ If they want to help me, maybe I never realised it, and I accepted the help. And that is why I come here and all of that ‘And it made me [feel better] to come here and become aware of the reality I live’); V1, 013; V2, 045.

9. V2, 006; V2, 015; V2, 041; V2, 050; V2, 052.

10. V1, 050; V1, 038; V1, 002; V1, 004; V2, 049; V2, 052; V1, 021; V1, 023.

11. V2, 007; V2, 011; V2, 021; V2, 028; V2, 038; V2, 006; V2, 023.

12. V1, 033; V1, 034; V2, 012; V2, 050; V1, 008.

13. V1, 012; V1, 028; V1, 037 (expressed feeling happy with the pro bono attorney because the attorney called her all the time); V1, 008 (expressed feeling confident in the type of follow-ups the Public Prosecutor’s Office did); V2, 006 (expressed feeling supported by the Public Prosecutor’s Office because they called her frequently and provided guidance to her); V2, 050.

14. e.g. a Victim found an incentive to continue with the complaint after a call from the Public Prosecutor’s Office, V1, 034.

15. V2, 019; V1, 024; V2, 031; V1, 032; V2, 035; V–IwSP, 040; V2, 050.

16. The Public Prosecutor’s Office was not mentioned as frequently as the former, and this could be explained by the fact that interviews took place in their location.

17. V1, 012; V1, 014; V1, 021; V1, 022; V1, 024; V1, 036; V1, 050.

18. e.g. because they previously had to do other administrative paperwork there, V1, 005; V1, 026.

19. V1, 030; V2, 003; V–IwSP, 009; V2, 017; V2, 019; V2, 026; V1, 026; V2, 028; V–IwSP, 030; V2, 033; V–IwSP, 033; V1, 037; V2, 037; V–IwSP, 041; V2, 044.

20. V2, 015; V2, 017; V2, 044; V–IwSP, 005; V1, 052; V2, 052; V2, 053.

21. V–IwSP, 017 (e.g. the Victim explained to Public Prosecutor’s Office that she was waiting for her attorney to come back from vacation to request an extension of the restraining order); V2, 001; V2, 003; V1, 004; V1, 005; V1, 006; V2, 006; V2, 007; V1, 007; V1, 013; V1, 014; V2, 014; V1, 015; V2, 015; V–IwSP, 017; V2, 017; V1, 022; V1, 023; V1, 026; V2, 028; V2, 033; V–IwSP, 033; V2, 035; V2, 037; V1, 042; V1, 044; V1, 045; V–IwSP, 046; V1, 052; V2, 052; V–IwSP, 053; V1, 053; V2, 053.

22. The Victim signed a six-month agreement for a monthly payment of ARS 600, V2, 015.

23. V–IwSP, 030; V2, 031; V1, 037; V–IwSP, 042; V1, 044; V–IwSP, 048.

24. V1, 016; V1, 017; V2, 017; V1, 041; V2, 019; V2, 028; V1, 004; V1, 037; V–IwSP, 040; V1, 013.

25. Twenty-six Victims have ‘significant support provided by others,’ while eleven Victims have ‘support provided by others, yet not significant,’ and two Victims have ‘no support.’

26. V1, 001 (boyfriend and office colleagues); V–IwSP, 002 (sisters); V–IwSP, 004 (social network); V–IwSP, 011 (family and two friends); V–IwSP, 014 (family, friends, psychologist); V–IwSP, 030 (family, friends, psychologist); V–IwSP, 019 (family, friends, psychologist); V–IwSP, 015 (family members); V–IwSP, 026 (friends); V–IwSP, 023 (family and husband, note: the accused was her brother); V–IwSP, 021 (family and friends); V–IwSP, 024 (family); V–IwSP, 017 (family, psychologist, lawyer, friends); V–IwSP, 018 (family, friends, office colleagues); V–IwSP, 033 (family and office colleagues); V–IwSP, 037 (family and psychologist); V–IwSP, 042 (friends and children); V–IwSP, 040 (family and friends); V–IwSP, 045 (family and friends); V–IwSP, 046 (family); V–IwSP, 052 (husband, family, psychologist, note: the accused was the boyfriend of her 17 year old daughter); V–IwSP, 054 (family and friends); V–IwSP, 053 (family and friends); V–IwSP, 034 (family); V–IwSP, 049 (family and friends); V–IwSP, 044 (neighbour and friend, because the family lives in Bolivia).

27. e.g. the Victim expressed during the first interview that she had a friend who supported her. During the second interview, she mentioned not seeing that friend any longer and believed her friend did not want to see her anymore because she returned to the accused, V2, 037.

28. The Victim lost a child between the first and second interview and had to spend time in hospital. During this period she regained her relationship with her family, and since then the family has become a big support for her, V2, 051.

29. In file with the author.

30. The sample can be divided as follows: three Victims are below 20 years of age (17-represented by her mother age 39-, 18, and 19). Thirteen Victims are in their twenties (22 two, 23 two, 24, 25, 26 two, 28 two, 29 three). Thirteen Victims are in their thirties (30 two, 31, 32 three, 36 two, 37, 38 two, and 39 two). Twelve Victims are in their forties (40, 41, 42, 43 four, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49). Five Victims are in their fifties (50, 52, 55, 57, and 59). Two Victims are in their sixties (68 and 69). Six did not answer to the question.

31. The sample can be divided as follows: unfinished primary education ≥ 6%; completed primary education ≥ 12%; unfinished secondary education ≥ 14%; finished secondary education ≥ 20%; unfinished tertiary education ≥ 10%; finished tertiary education ≥ 10%; unfinished university education ≥ 16%; finished university education ≥ 8%.

32. The sample can be divided as follows: 27% have 1 child ≤ 57% have 2 children, 8% have 3 children, ≤ 3% have 5.3% have 7, and 3% have 9 children.

References

- Barendrecht, M., 2010. Legal aid, accessible courts or legal information? Three access to justice strategies compared. TISCO Working Paper Series on Civil Law and Conflict Resolution Systems No. 010/2010. Available from http://ssrn.com/paper=1706825 01 June 2020.

- Barendrecht, M., Kamminga, P., and Verdonschot, J.H., 2008. Priorities for the justice system: responding to the most urgent legal problems of individuals. SSRN ELibrary. Available from http://ssrn.com/paper=1090885 01 June 2020

- Barendrecht, M., Mulder, J., and Giesen, I., 2006. How to measure the price and quality of access to justice? SSRN ELibrary. Available from http://ssrn.com/paper=949209 01 June 2020

- Bedner, A.W. and Vel, J.A.C., 2010. An analytical framework for empirical research on access to justice. Law, Social Justice & Global Development (LGD), 15 (1), 29.

- Bruce, J.W., et al., 2007. Legal empowerment of the poor: from concepts to assessment. U.S. Agency for International Development.

- Cappelletti, M., and Garth, B., 1978. Access to justice Vol. I: a world survey (Book I & II). European University Institute: Giuffrè Editore/Sijthoff/Noordhoff. Available from http://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/18559 15 April 2018

- Cappelletti, M., Gordley, J., and Johnson, E., Jr., 1975. Toward equal justice: a comparative study of legal aid in modern societies. Milan: Giuffre & Oceana Publications.

- Christie, N., 2010. Victim movements at a crossroad. Punishment & society, 12 (2), 115–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474509357978

- Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor, 8AD. Making the Law Work for Everyone. Vol I. Report of the Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor. New York: Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor and United Nations Development Programme.

- Contravention Code, 2004. Código Contravencional de La Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. http://www.buenosaires.gob.ar/areas/seguridad_justicia/justicia_trabajo/contravencional/completo.php

- Convención Constituyente, 1996. Constitución de La Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Available from http://www.legislatura.gov.ar/documentos/constituciones/constitucion-ciudad.pdf 01 June 2020.

- Criminal Code, 1984 Código Penal de La Nación . . http://www.infoleg.gov.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/15000-19999/16546/texact.htm. Congreso de la Nación Argentina

- Currie, A., 2006. A national survey of the civil justice problems of low-and moderate-income Canadians: incidence and patterns. International journal of the legal profession, 13 (3), 217–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09695950701192194

- Douglas, S., and UNDP, 2007. Gender equality and justice programming: equitable. Access to justice for women. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- Drost, L., et al., 2013. Restorative justice in cases of domestic violence. WS1. Comparative Report. Criminal Justice 2013 with the financial support of the European Commission.

- Friedmann, J., 1992. Empowerment: the politics of an alternative development. Economic Geography: Blackwell Cambridge MA & Oxford UK.

- Genn, H., 1999. Paths to justice: what people do and think about going to law. Oxford: Hart.

- Genn, H., 2009. Hazel genn and paths to justice. In: Conducting law and society research, reflections on methods and practices. Cambridge Studies in Law and Society: Cambridge University Press, 227–239.

- Golub, S., 2010. What is legal empowerment? An introduction. In: Legal empowerment: working papers Golub, S. Rome, Italy: International Development Law Organisation, 15.

- Golub, S, 2003. Beyond rule of law Orthodoxy: the legal empowerment alternative. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available from http://carnegieendowment.org/2003/10/14/beyond-rule-of-law-orthodoxy-legal-empowerment-alternative/bet [Accessed 6 May 2014.

- Graham, R.G, n.d. Research methods in the social sciences with a particular focus on qualitative research. YouTube. Available from http://www.youtube.com/user/GrahamRGibbs?feature=&view=. [Accessed 22 February 2013].

- Gramatikov, M. and Porter, R.B., 2010. Yes, I Can: subjective legal empowerment. Tilburg University, TISCO Working Paper Series on Civil Law and Conflict Resolution Systems No. 010/2010, October, p. 46.

- Hesse-Biber, S.N., and Leavy, P., 2010. The practice of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- King, G., Keohane, R.O., and Verba, S., 1994. Designing social inquiry. Princeton University Press.

- Macdonald, R.A., 2010. Access to civil justice. In: The oxford handbook of empirical legal research Cane , Peter, and Kritzer, Hebert. Oxford University Press, 492–521.

- Maxwell, Gabrielle M., Smith, Catherine, Shepherd, Paula J. & Morris, Alison (1999) Meeting Legal Service Needs (Wellington, New Zealand Legal Services Board).

- Oppenheim, A.N., 1992. Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Padgett, D.K., 2008. Qualitative methods in social work research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Pleasence, P., et al., 2004. Causes of action: civil law and social justice. Final Report First Edition. First LSRC Survey of Justiciable Problems. Legal Services Commission.

- Ptacek, J., ed., 2009. Restorative justice and violence against women. Oxford Scholarship Online 15 May 2017 doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195335484.001.0001.

- Research, and Public, Legal Needs and Civil Justice: A Survey of Americans: Major Findings of the Comprehensive Legal Needs Study, 1994 https://www.wisbar.org/aboutus/membership/Documents/WisTAFApp_J_ABA_Legal_need_study.pdf

- Rubin, H.J., and Rubin, I.S., 2012. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data. SAGE Publications doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226651.

- Scott, P.D., 1958. Juvenile courts: the Juvenile’s point of view. British journal of delinquency, 9, 200.

- Shapland, J., Robinson, G., and Sorsby, A., 2011. Restorative justice in practice: evaluating what works for victims and offenders. New York, NY: Willan.

- Sherman, L.W., 2000. Domestic violence and restorative justice: answering key questions. Virginia journal of social policy & the law, 8, 263.

- Strang, H., and Braithwaite, J., 2002. Restorative justice and family violence. United Kingdon: Cambridge University Press.

- UN Secretary General, 2002. Justicia Restaurativa. E /CN.15/2002/5/Add.1. 11° Período de Sesiones. Available from https://www.unodc.org/pdf/crime/commissions/11comm/5add1s.pdf 01 June 2020.

- Van De Meene, I., and Van Rooij, B., 2008. Access to Justice and Legal Empowerment. Making the Poor Central in Legal Development Co-Operation. Leiden University Press. Available from http://books.google.nl/books?id=U_U84FKFBBQC 01 June 2020.

- Walker, J., et al., 2007. The family advice and information service: a changing role for family lawyers in England and Wales? Final evaluation report. Final Evaluation Report. Newcastle Centre for Family Studies.

- Webley, L., 2010. Qualitative approaches to empirical legal research. In: The oxford handbook of empirical legal research Cane, Peter, and Kritzer, Herbert M. Oxford University Press, 926–950 doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199542475.013.0039.

- Wojkowska, E., and UNDP, 2006 Doing justice: how informal justice systems can contribute .Oslo Governance Centre: UNDP.

- Wolcott, H.F., 2008. Writing up qualitative research. 3rd ed. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- XIV Ibero-American Judicial Summit, 2008. Brasilia regulations regarding access to justice for vulnerable people. Available from https://www.icj.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Brasilia-rules-vulnerable-groups.pdf 01 June 2020.

- Paths to Justice in the Netherlands