Introduction

Part 2 of this special issue on knowledge democracy continues to examine what we presented in Part 1 as an important and challenging topic for the global action research community. In Part 1 we included eight articles and two book reviews. In this issue, we include another six articles and an additional book review. For the Part 2 editorial, we have chosen to experiment with an aspect of democratizing knowledge and that is to practice in a transparent manner what Budd Hall and Rajesh Tandon describe as ‘linking values of democracy and action to the process of using knowledge’ (Hall and Tandon Citation2015). Our experiment involves each of us writing a separate brief editorial based on our individual readings of the articles included in Part 2. Although we both agreed that these are the articles we wanted to include, we realized over the course of our communications regarding the content of the articles that we had different understandings and impressions of the articles’ contents as well as the relationships of the content to the theme of this special issue. We then respond to what we each have written in a spirit of reflection on our similarities and differences in relation to values of democracy, action, and the use of knowledge.

We again want to thank all the contributors to this special issue as well as the reviewers and our journal leadership team at the University of Nottingham. Thank you for your patience, guidance and support throughout the process of putting together this special issue. We realize that to capture the essence and nuances of current work in the knowledge democracy space we have pushed the boundaries of what Convery and Townsend (Citation2018) discussed as reasons why articles are accepted and rejected in EARJ. Thanks also to those who provided feedback on Part 1 of the special issue. Your comments confirmed the relevance of the topic, and the urgency faced by the global action research community in taking action to support further explorations of democratizing knowledge production and dissemination.

Lonnie’s editorial

In the editorial for Part 1 of this special issue, Allan Feldman and I examined relations between knowledge democracy and action research through a brief comparison of criteria for knowledge democracy and the focus of each of the articles included in Part 1. At a minimum, we established that action research has the potential to be a key player and a close ally with others in the larger knowledge democracy movement. Knowledge produced by action researchers often reflects a widened ‘methodological imagination’ (Fine Citation2018) and at least a nod towards democratizing knowledge production.

Part 2 of the special issue continues the exploration of these issues, with a twist. We include two lengthier articles: one that brings to the foreground deeper challenges associated with democratizing knowledge production in the context of global north and global south relations and provides possible signposts for further considerations of strategic directions for the global action research community in relation to knowledge democracy (e.g. Rowell et al. Citation2017; Rowell Citation2019); and one that describes a changed methodological imagination based on an encounter between western-oriented research and the leaders and members of an indigenous community in Southern Chile. In his article, Thomas Stern takes on what is certainly one of the toughest questions for advocates of knowledge democracy, namely, to what extent do advocates believe that science and alternative knowledges are compatible and ‘on equal footing’? While the essence of the radical idea of knowledge democracy is found in recognizing and respecting the diverse epistemologies found around the globe, Stern places the epistemological framework of action research squarely within the western worldview. While others also have raised this issue of where to situate action research epistemologically (e.g. Carr Citation2006), Stern addresses it in the specific context of efforts to align knowledge democracy and action research. His article critically examines a way forward given concerns that science itself is the ‘back side’ of the colonial project through which a vast ‘subjugation and eradication’ of traditional knowledges has been unleashed on the Global South by the Global North. Stern explores the tensions between a western science orientation and knowledge democratization and identifies some ways that action researchers can contribute to lessening the tensions and building bridges ‘towards a truly pluralistic and democratic world.’ Stern’s article is a strong example of the importance of developing a critical consciousness about our own personal knowing and the larger processes of formal knowledge construction. This is a powerful study in consciousness-raising tied to the spirit of the globally emerging participatory paradigm (Heron and Reason Citation1997).

The second-long article, by Miguel Del Pino and Donatila Ferrado, provides a fine illustration of the bridge-building process at work in one country in the global south. The authors describe their work with a community of the Mapuche people, the most populous indigenous group in Chile, to create a Mapuche education as an alternative to the Chilean government-sanctioned bilingual and intercultural education programme. The article explores the complexities of working in socio-cultural, historical, intellectual, and knowledge construction zones in which an ‘epistemological rupture’ has taken place that allows for the enactment of more participatory approaches including participatory action research. In an earlier article, the authors introduce the investigative practice that has emerged over the course of a research project initiated more than a decade ago by a group of Chilean and Mapuche researchers (Ferrada and Del Pino Citation2018). They assert that the type of research they now present ‘can be perfectly developed in other environments’ provided the actors in these environments are willing to confront together their conflicting rationales about the production of knowledge and to accept the time needed (they suggest 2 to 3 years) for transforming a research community into a truly egalitarian group. In the present article, Del Pino and Ferrada apply their Dialogic-kishu kimkelay ta che research approach to addressing a critical issue identified by a local community. In this case, a Mapuche community wished to establish Mapuche education based on a curricular framework rooted in the language, culture, and epistemological understandings of the Mapuche, as transmitted across generations and lived in the present alongside western-oriented Chilean cultural and educational perspectives. The article provides an important example of the inner workings of knowledge democratization based on a deeply felt and profoundly egalitarian collaboration. Included in the approach they use is a framework for assessing the knowledge produced through the research method, with knowledge distinguished as ‘transformative, conservative, or exclusive’ depending on its relation to the actual change being sought by the community. The authors also detail the practical significance of bidirectional dialogic collaborations in relation to larger issues of state policy-making impacting indigenous groups and to community-based challenges to the historical marginalization of these group’s orientations towards knowledge production and knowledge mobilization.

Other articles in part 2 of the special issue examine knowledge democracy and action research potentials and challenges in different contexts in the global north. Cook et al explore the use of ‘disruption’ in participatory action research in the UK to shake up assumptions regarding knowledge production and power and privilege and to deepen understandings of knowledge democratization in mental health, disability services, and family care services. Here, the authors bring to mind the idea of ‘translational contact zones’ (de Sousa Santos Citation2014). Such zones are needed in decolonizing oppressive knowledge mobilization spaces. The service domains examined by Cook et al. are often marginalized spaces defined by unequal relations, rejection, dehumanization, discrimination, and stereotypes. Such spaces can benefit from various forms of disruption in the service of greater bidirectional, democratic, and dialogic understanding. Percy-Smith et al. examine the diversity of youth-led action research found in eight European cities. Their work highlights the creative potential of knowledge democratization initiatives in relation to youth empowerment in a variety of social spaces. Although the particular socio-cultural and historical contexts of youth vary between nations in the global North and/or South, initiatives for democratizing knowledge in relation to their needs, interests, and concerns are urgently needed, and what Percy-Smith et al. show us is the great potential of action research, and in particular participatory action research and youth participatory action research to respond to those needs. In the work of Fernandez-Diaz and her colleagues, we see an example of how a process of systematic reflection on knowledge democratization can lead to reconceptualizations of pedagogies, including the pedagogies associated with teacher preparation, and to creative and determined efforts to democratize teaching and learning. In their case, the work is done across universities and features experimentation with forms of displaying knowledge.

The Shosh article provides another example of experimenting with the production of knowledge in education, this time within a region of one state in the US. Although a great deal has been written about educational action research (e.g., Noffke and Somekh Citation2009; Mertler Citation2019), much less literature is found that examines critically the ways in which education research in the global north and global south have been colonized and are in a condition such that educational action research represents a decolonizing force, or at least could be such a force (Rowell Citation2019; Hong and Rowell Citation2019; Rowell and Hong Citation2017) if it is able to shake off its current formulaic and technocratic problem-solving orientation (Feldman Citation2017). In the case of the Shosh group, participation in a global call for regional workshops in preparation for convening of the 1st Global Assembly for Knowledge Democracy in 2017 (Wood, McAteer, and Whitehead Citation2019) introduced a new lens to an already planned project involving examining ways to strengthen the practice of student leadership development in their region’s schools. While teacher-researcher team members conducted site-based participatory action research and youth participatory action research projects, Shosh and three project consultants worked to support team members in beginning to see their projects within a knowledge democracy framework. One result was a heightened sense of responsibility for the knowledge production and knowledge dissemination associated with their individual projects and with the initiative as a whole. Another was the increasingly strong engagement of team members with the relations between youth participatory action research and student leadership development. The article calls to mind what Call-Cummings calls ‘critical empowerment’ in the classroom (Citation2018), which she examined as a process for addressing issues of marginalization and oppression through participatory forms of knowledge production in education. The Shosh article points to ways participatory approaches can be used in relation to school site and district curricular designs, and school-based programs supporting character development, student leadership, and civic literacy in general.

Allan’s editorial

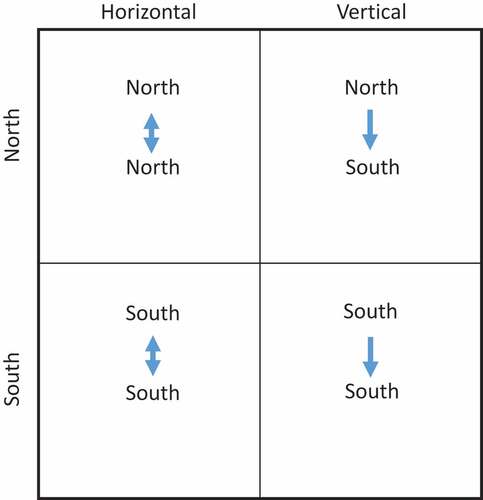

In our article in the first special issue on knowledge democracy (KD) and action research (AR), Fred Bradley and I (Feldman and Bradley Citation2019) proposed a framework for understanding the nature of knowledge democracy. From our analysis of the literature, we uncovered at least two different conceptions of what is meant by KD, which we called horizontal and vertical conceptions. Each conception identifies a divide. The horizontal divide is between controlled and unrestricted production, dissemination and use of knowledge, while the vertical divide is between privileged knowledge, often associated with the global North, and marginalized knowledge, which is associated with the global South (see , 93 of Feldman and Bradley (Citation2019)). After a careful read of the articles in this second special issue on KD, I believe that a modification of that framework can be useful in unpacking further what we mean by KD in relation to AR.

Figure 1. A 2 × 2 table for unpacking the relationship between knowledge democracy and action research.

This new framework uses a simple device that I am quite fond of – the 2 × 2 table (see ). Before I explain what it means, I do want to acknowledge that there are dangers in using this type of table. First, the very nature of the table suggests that there are solid boundaries between the quadrants, and second, it can reify false dichotomies. This 2 × 2 table, like all others, is a human construction that consists of humanly constructed concepts. Neither the walls of the quadrants nor the split between the concepts (North/South, Horizontal/Vertical) are real. It is up to me as the author and you as the reader to make sure we recognize the fluidity among these ideas.

In Fred and my article (2019), we were primarily concerned with the top row of the table. What we called the horizontal conception was situated in the North. It considered the production, flow, and use of knowledge within the social, political, and economic structures among individuals, communities, institutions, and corporations in countries with high Human Development Indices (HDI).Footnote1 The vertical conception focused on the contrast between high-status knowledge production in the North with that of the low status of knowledge produced in local communities and indigenous peoples in the South (lower HDI countries). Even though this conception straddles the North/South divide, much of what appeared in our previous special issue, and this one is written from the perspective of the North, which is why it is located in the top row and the arrow is unidirectional.

The bottom row of the table recognizes that it is possible to consider the horizontal conception of KD in the South. That is, within the global South and within lower HDI countries, there is the production, flow, and use of the high-status knowledge among the more privileged (individuals, communities, institutions, and corporations), similar to that within the global North. The lower right quadrant highlights the contrast between high-status knowledge production within the South and knowledge produced in local communities and indigenous peoples in that region.

I used this framework to revisit the articles from the first special issue and for those in this issue. Although many of the articles cite scholars from the global South who urge us to recognize the importance of indigenous and local knowledge, as well as the dangers of epistemicide (e.g., de Sousa Santos Citation2014; Fals Borda and Rahman Citation1991), most of the articles in both issues deal primarily with KD within the global North. Four of the articles in this issue focus on the democratization of knowledge within their local, northern contexts, which I locate in the upper right-hand quadrant of the 2 × 2 table. Cook et al. examine the ways that disruptions in the participatory action research (PAR) process can lead to greater KD. In their article, they show this in three projects. The first was a PAR project with a mental health service user forum in the northeast of the England. The authors questioned whether the participants’ training in traditional research methods limited what could be known and also limited the possibility of radical change in service delivery. The second used action research, PAR, and Radical Dissensual Research as ways to interrogate and expose the power structures that arose in the UK when disabled people were allowed to have a greater say in their care. The third project was also in the UK and focused on the needs of family caregivers of adults with learning disabilities and challenging behavior. Its purpose was to bring together the knowledge and experience of professional service deliverers with that of family carers to develop a course for them using Mindfulness and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Each of these projects sought to disrupt traditional ways of including participants in PAR to move toward greater KD within their situations in the global North.

The focus of the second article in this quadrant is teaching in Spanish universities. Elia Fernández-Díaz and her colleagues from different universities in Spain describe how they rethought their teaching along the lines of a model of participatory responsibility based on social connection through the use of action research. They report on how they were able to collaboratively reflect on the meaning of democratization, problematizing their relationship with their students and helping them to commit to promoting activism. This was done through the generation of an environment in which they explored the meaning of their practices through visual narrative, weaving and identifying their biographies and how they interact with one another. In doing so, they searched for the meanings of their actions in their communities and the challenges of social justice.

Barry Percy-Smith, Gráinne McMahon, and Nigel Thomas similarly locate their work of promoting knowledge democracy in the global North. In their case, it is a study that looked at how and where young people (ages 15–30) participate in youth-led action research projects in eight European cities. The projects used a wide variety of ways to engage in action research, ranging from the more traditional approaches, to more action-focused and arts-based approaches. In their article they illustrate the diverse ways that the young people were able to promote knowledge democracy in formal, non-formal, and informal spaces. In these projects, the youths struggled for recognition, respect and social justice as they actively contributed to their communities as citizens, which helped to give meaning to their values and identities.

The fourth article, by Joe Shosh, describes the process by which a collective of teachers in the US worked to promote youth leadership in their schools through youth participatory action research (YPAR). Following up on their participation in the Global Assembly, the group developed a set of guidelines for the promotion and support of YPAR.

All four of the articles that I summarized above have as their focus the promotion of knowledge democracy within communities or institutions in the global North. In doing so they sought to uncover the boundaries and impediment for wider participation of citizens in the production and use of knowledge, and to take action for knowledge mobilization. While there are status differentials between the academics writing these articles and their participants (clients in the health services in the UK; students in Spanish universities; youth activists in European cities; and teachers and students in the US), I do not see in them the differentials that exist between knowledge and its production in the global North with that in the global South. Thomas Stern, in his article, turns to those differences from his perspective in an Austrian university. Therefore, I see his work fitting into the upper right quadrant of the 2 × 2 table as he looks from the North to the South. In his insightful article, he raises questions about the compatibility of knowledge produced by traditional communities, marginalized groups, and grassroots movements, which is associated with the Global South, with the privileged knowledge of the Global North. He provides us with examples of how when there is an appreciative exchange of different perspectives, knowledge from different epistemologies can mesh as local people and researchers work together to result in increased self-consciousness and emancipation from the social constraints of both the global North and global South.

The remaining article in this issue, by Miguel Del Pino, is the only one that I found to fit in the bottom row of the 2 × 2 table. I see it fitting into the lower right-hand quadrant because Del Pino, a university professor in Chile, works with the Mapuche people who live in the Araucanía region of Chile to promote knowledge democracy. I located this study in the lower row because it was written by and takes place in the global South. It is in the right column because the Mapuche’s knowledge and their ways of producing it are what are typically associated with the label global South, and are feeling the dangers of epistemicide. This highly informative and thought-provoking article reports on the development of a Mapuche education program in response to indigenous demands and claims as a replacement for the curriculum supplied by the national education system. This was done using a methodology, dialogical-kishu kimkelay ta che, that was developed jointly between Del Pino, his colleagues and students, and indigenous experts (a Maci, two Kimches, a Gütancefe, and Mapuche teachers). The article closes with an important implication for those of us who reside, either physically or epistemologically, in the global North – we need to have at least some knowledge of the indigenous language. This would help us to begin to understand epistemological differences; and to help develop a sense of how it is for indigenous people as they live in the boundary lands between their traditional world and values and those of the global North.

In closing my section of this editorial, I want to note that in itself, there is no reason to be concerned that most of the articles in the two issues would be located in the upper left-hand quadrant. Those articles describe and examine important work being done to promote knowledge democracy and mobilization within the contexts within which the authors work and live. However, if Educational Action Research is to be an international journal that provides an outlet for this type of work throughout the world, then we should be looking critically at how we can better support researchers doing this important work in both the global North and South, and with those whose knowledge democracy is restricted horizontally and vertically.

Lonnie’s response

I appreciate Allan and Fred’s framework as a useful construction for generating further discussion of knowledge democracy (KD) and its relation with action research. The framework considers the production and uses of knowledge in relation to a differentiated global north and global south as well as a distinction between what they call ‘high status’ and ‘low status’ knowledge. They equate higher status knowledge with privileged contexts such as formal state-sponsored institutions and well-funded knowledge production initiatives, while lower status knowledge is that which emerges from subaltern spaces associated with marginalized groups and indigenous cultures. Their framework thus incorporates two of the crucial considerations found in the literature and activism surrounding KD, namely the existence of a divide between knowledge produced in the global north and the global south and the issue of whose knowledge counts. In his part 2 editorial, Allan applies this framework to a content analysis of the 14 articles included in our special issue. He concludes that although the content acknowledges the divide most of the articles address KD in the global north. I value his reminder that EARJ has much work to do if it wishes to truly represent the international dimensions of educational action research, particularly in the context of supporting democratizing knowledge production and mobilization.

Allan also acknowledges the tendency for boundaries and quadrants to reify false dichotomies and challenges readers to recognize fluidity among ideas about action research and knowledge democracy. A number of such recognitions come to mind for me, including questions about potentials for the flow of knowledges between these divides. In Del Pino and Ferrada’s article, for example, we see a dynamic process of shifting the context of a research methodology from a ‘high status’ perspective (i.e. western-oriented scientific inquiry), with its associated threat to extinguish the ways of knowing of an indigenous people (de Sousa Santos Citation2014), to a method co-created with indigenous people in the context of their self-determined efforts to retain their epistemological frameworks. The co-constructed method is then used to address a problem in a critical contact zone between their culture and the larger national culture in which they wish to live in harmony. Although, this bridge-building takes place as part of a study that Allan states ‘highlights the contrast between high status knowledge production within the South and knowledge produced in local communities [by] indigenous peoples in that region,’ it seems important not to miss the point that the purpose of the project was to find a way past the contrast. Furthermore, publication of the article in EARJ contributes to correcting the ‘unequal relations of knowledge’ (Falls Borda & Rahman, Citation1991) between the global north and the global south. These are dynamics associated with what I would call cyclical potentials of knowledge democracy aligned with participatory action research, with research and action situated in either the north or the south helping lower boundaries between categories and types of research and contributing to the further democratization of knowledge production and mobilization on a global basis.

I also recognize similarities and differences in action research and knowledge democracy in relation to varied areas of expertise. My particular interest is in the challenges associated with democratizing knowledge production and mobilization in education. I recently examined rigor in educational action research as a ‘stance of opposition’ within education research (Rowell Citation2019, 118). Similarly, Eunsook Hong and I have examined KD and educational action research in the context of building both localized knowledge democracies and alternative globalization initiatives (Rowell and Hong Citation2017; Hong and Rowell Citation2019). In our view, the importance of teacher, student, and parent involvement in the production of practice-based research evidence (PBRE) is the interplay of knowledge democratization and the search for creative solutions to problems of educational practice. We note that ‘the more grounded action research has been in working respectfully with diverse knowledges, the more it has “slipped the bonds” of epistemological privilege’ (Rowell and Hong Citation2017, 69). Fluidity in relation to ‘high status’ and ‘low status’ knowledge categories reflects specific contexts associated with areas of expertise, with education being one of those areas, and these contexts indicate the demarcation lines for struggles regarding knowledge creation. Thus, the knowledge being produced in the Shosh team’s project may have a higher status in their region due to the project’s support from the larger community. The participating teachers then found their voices as empowered educators rather than having to struggle as ‘de-skilled technicians’ (Giroux, Citation2003). Also, through a link with a larger knowledge democratization initiative, the project provides additional legitimacy for knowledge production by teachers, and the teacher-researchers begin to articulate a rationale for empowering student voice as well.

Ultimately, advocating for knowledge democracy and for action research requires recognition of the vast institutional and economic power of the current monolithic knowledge structure and a keen awareness of the negative psychological effects of ‘intellectual colonialism’ (Fals Borda & Mora-Osejo, Citation2003). Frameworks such as that offered by Allan can help us to organize our thinking about KD as an idea and as a path forward in which action research can play a critical role. They can provide vantage points from which to look critically at the direction we are headed in relation to the idea. What they cannot do is to infuse the needed spirit to take up the work required for change to occur (Rowell Citation2019). That spirit is found in the crucible of action research at whatever place on the planet someone seeking that spirit is situated.

Allan’s response

I am writing this after having read Lonnie’s part of this editorial and his response to my part. His thoughtful analysis of the articles in this issue resonate with me, and I see much similarity to our approaches and interpretations. In my reflection on his words and our reading of the articles, I am reminded of the work of Gloria Anzaldúa (Citation1987). In her book Borderlands: La Frontera she wrote about the ‘borders’ that exist between countries, cultures and peoples, in particular between Mexico and the United States, and between people of different genders. Most importantly in relation to knowledge democracy, she explored the borderlands, la frontera in Spanish, in which we find ourselves living in more and more, by delving into her experience as a Chicana. The geographical borderland straddles both sides of the national border between Mexico and the US, and what we have been referring to in this editorial as the divide between the Global South and the Global North. People in these borderlands experience la mezcla, a sort of hybridity or fluidity in which one is part of each side of the border and also of both.

I believe that the knowledge democracy that the authors in these two issues strive for is located in the borderlands. It is a borderland that is somehow part of and between the epistemologies of the South and the North. What I mean by this is that we should not be looking for ways that those of us in the North allow for epistemologies of the South to have legitimacy; or for those of the South to have some type of ascendency over those of the North. Rather, each has is legitimate in its own context, while at the same time we should be seeking ways to have la mezcla that goes beyond each.

I see this struggle for an epistemology of the borderlands in each of the articles in this issue. As Lonnie’s and my comments above suggest, this is most evident in the articles by Thomas Stern, and Miguel Del Pino and Donatila Ferrado. As Lonnie and I noted above, Stern’s article highlights the difficulties that come about when attempting to put Western science and alternative forms of knowledge ‘on equal footing’. In doing so he contrasts these ways of knowing and raises the possibility of an epistemology of the borderlands. Del Pino and Ferrado’s article describes their response in collaboration with the Mapuche to the attempt by the Chilean government to bring Mapuche youth across the ‘border’ to the world of Europeanized Chile through the Bilingual Intercultural Education Program (BIEP). While the Mapuche rejected the BIEP as a mechanism of oppression by the state, they acknowledged that although being indigenous people, they had begun to reside in the borderlands. Therefore, they sought to develop a curriculum from their perspective as an indigenous community that would allow them to keep their language and culture while interacting with western culture. As they acknowledge in their article, Del Pino and Ferrado found that for them to be of help to the Mapuche they also needed to find a way to inhabit the borderland between the cultures.

The other four articles in this issue also struggle with a way to inhabit the borderlands, but rather than between North and South, across the borders between those with high status knowledge (in all four examples university professors) and those who have been marginalized in some way (caregivers, patients, teachers, and students). Cook et al. exhibit the struggle of working in la frontera in their examination of the use of disruption of PAR in what Lonnie has described as ‘translational contact zones’ (de Sousa Santos Citation2014). Similarly, the European YPAR projects examined by Percy-Smith et al. took place in those spaces created where youth culture came up against the discourse of the national research teams. It is in those spaces of la mezcla that the young people developed new forms, understandings, and practices for knowledge democracy. The article by Shosh also raises issues related to the crossing of borders. In this case, they are between university researcher, school teachers, and school students. While the focus of the teachers’ work was on the development of youth leadership through YPAR, leadership was made problematic across the hierarchal structure inherent in schools and universities as they all wrestled with taking on and learning how to engage in leadership. Finally, Fernández-Díaz and her colleagues weaved biography and visual narrative to construct an environment between the walls of their separate universities, and between them and their students. It was in this borderland that they engaged in critical inquiry to promote with their students opportunities for activism.

Conclusion

We (Lonnie and Allan) ended the editorial for part 1 of this special issue on knowledge democracy and action research by noting that holding to an open space for the generation of knowledge democracy requires a constant vigilance. Nothing included in part 2 lessens the importance of that recognition. The work involved in building knowledge democracies is hard and requires determination (Rowell Citation2019). We wish to acknowledge again that the concept is not ‘owned’ by action researchers any more than it is owned by those working in other democratizing spaces. While the concept is at work in varied forms in various parts of the world, it is up to those engaged in this work to now define how a movement to democratize knowledge will be framed, led, and sustained in the years to come. Following on the work of Susan Noffke, we acknowledge the importance of seeking convergences among the varied kinds of knowledges found around the world and embraced by action researchers, the growing number of knowledge production methods, and the diverse ends towards which action research projects are aimed (Noffke & Somekh; Fals Borda and Moro-Osejo Citation2003). Our hope remains that this 2-part special issue contributes to building momentum in relation to such convergences. In the end, we believe knowledge democracy is not only a shared interest among many in the global action research community but is a critically needed alternative to knowledge production and dissemination associated with corporatized globalization and knowledge economy schemes in which inequalities and social injustices are rationalized and reified and efforts to make the world a safer, freer, and more sustainable place for all its inhabitants are marginalized, chased down, and delegitimized.

Notes

1. According to the United Nations, the ‘The HDI was created to emphasize that people and their capabilities should be the ultimate criteria for assessing the development of a country, not economic growth alone’ (United Nations Development Programme Citation2019). It was constructed to take into account measures such as ‘long and healthy life’; ‘knowledge’; and ‘a decent standard of living’. A look at the data for 2017 suggests that those countries that are usually considered the part of the global North are in the top part of the list, while those in the global South are in the lower part.

References

- Anzaldúa, G. 1987. Borderlands: La Frontera. San Francisco: Aunt Lute.

- Call-Cummings, M. 2018. “Claiming Power by Producing Knowledge: The Empowering Potential of PAR in the Classroom.” Educational Action Research 26 (3): 385–402. doi:10.1080/09650792.2017.1354772.

- Carr, W. 2006. “Philosophy, Methodology, and Action Research.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 40 (4): 421–435. doi:10.1111/jope.2006.40.issue-4.

- Convery, A., and A. Townsend. 2018. “Action Research Update: Why Do Articles Get Rejected from EARJ?” Educational Action Research 26 (4): 503–512. doi:10.1080/09650792.2018.1518746.

- de Sousa Santos, B. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. London, UK: Routledge.

- Fals Borda, O., and L.E. Moro-Osejo. 2003. “Context and Diffusion of Knowledge: A Critique of Eurocentrism.” Action Research 1 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1177/14767503030011003.

- Fals Borda, O., and M. Rahman. 1991. Action and Knowledge: Breaking the Monopoly with Participatory Action Research. New York: Apex Press.

- Feldman, A. 2017. “An Emergent History of Educational Action Research in the English-Speaking World.” In The Palgrave International Handbook of Action Research, edited by L.L. Rowell, C.D. Bruce, J.M. Shosh, and M.M. Riel, 125–145. New York: Nature America.

- Feldman, A., and F. Bradley. 2019. “Interrogating Ourselves to Promote the Democratic Production, Distribution, and Use of Knowledge through Action Research.” Educational Action Research 27 (1): 91–107. doi:10.1080/09650792.2018.1526097.

- Ferrada, D., and M. Del Pino. 2018. “Dialogic-Kishu Kimkelay Ta Che Educational Research: Participatory Action Research.” Educational Action Research 26 (4): 533–549. doi:10.1080/09650792.2017.1379422.

- Fine, M. 2018. Just Research in Contentious Times: Widening the Methodological Imagination. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Giroux, H.A. 2003. “Public Pedagogy and The Politics Of Resistance: Notes on a Critical Theory of Educational Struggle.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 35 (1): 5–16. doi: 10.1111/1469-5812.00002.

- Hall, B.L., and R. Tandon (2015). Are We Killing Knowledge Systems? Knowledge, Democracy and Transformation. Retrieved from http://www.politicsofevidence.ca/349/

- Heron, J., and P. Reason. 1997. “A Participatory Inquiry Paradigm.” Qualitative Inquiry 3 (3): 274–294. doi:10.1177/107780049700300302.

- Hong, E., and L. Rowell. 2019. “Challenging Knowledge Monopoly in Education in the U.S. Through Democratizing Knowledge Production and Dissemination.” Educational Action Research 27 (1): 125–143. doi:10.1080/09650792.2018.1534694.

- Mertler, C.A., Ed. 2019. The Wiley Handbook of Action Research in Education. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Noffke, S.E., and B.S. Somekh, Eds. 2009. The SAGE Handbook of Educational Action Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Rowell, L.L., and E. Hong. 2017. “Knowledge Democracy and Action Research: Pathways for the Twenty-First Century.” In The Palgrave International Handbook of Action Research, edited by L.L. Rowell, C.D. Bruce, J.M. Shosh, and M.M. Riel, 63–83. New York: Nature America.

- Rowell, L.L., R. Balogh, C. Edwards-Groves, O. Zuber-Skerritt, D. Santos, and J.M. Shosh. 2017. “Toward a Strategic Research Agenda for the Global Action Research: Reflections on Alternative Globalization.” In The Palgrave International Handbook of Action Research, edited by L.L. Rowell, C.D. Bruce, J.M. Shosh, and M.M. Riel, 843–862. New York: Nature America.

- Rowell, L.L. 2019. “Rigor in Educational Action Research and the Construction of Knowledge Democracies.” In The Wiley Handbook of Action Research in Education, edited by C.A. Mertler, 117–138. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2019). Human Development Index (HDI). http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi

- Wood, L., M. McAteer, and J. Whitehead. 2019. “How are Action Researchers Contributing to Knowledge Democracy? A Global Perspective.” Educational Action Research 27 (1): 7–21. doi:10.1080/09650792.2018.1531044.