ABSTRACT

Complex public health programmes may suffer from ‘teething problems’ during their implementation in practice, especially when programmes are developed top-down without the participation of end-users and service providers. Trying out and optimising a new concept in practice with stakeholder´s participation may enhance the programme´s chance of success. In this article we describe the participatory optimisation process of a German primary prevention programme for stroke caregivers, performed before its full-scale implementation.

A Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach was applied immediately after the development of the preliminary programme that was led by the professional research team. Iterative PAR-cycles were composed of: observe, reflect, plan and act.

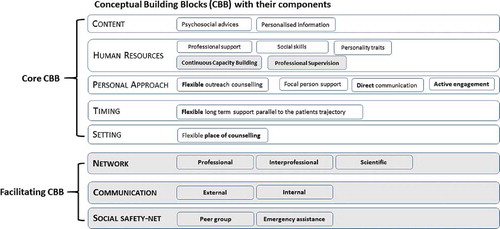

Through PAR a matured concept, containing eight Conceptual Building Blocks, was obtained. The five preliminary building blocks: `Content´, `Human resources´, `Personalised approach´, `Timing´, and `Setting´, were prioritised to be the core blocks, providing the base for individual caregiver support. Three new building blocks: `Network building´, `Communication´, and `Social safety-net´ were designated as facilitating blocks, interconnecting and safeguarding the programme.

PAR was found to be vital in systematically detecting the conceptual weaknesses of the preliminary concept and in adjusting its components to the needs of the key stakeholders, before full-scale implementation.

Introduction

Family caregivers play a key role in the day-to-day care of stroke survivors (Bakas et al. Citation2014), as they make up the primary support system after hospital discharge (Grant, Hunt, and Steadman Citation2014; Wetzstein, Rommel, and Lange Citation2015). Family caregivers are relatives, partners, friends or neighbours, who provide voluntary physical, practical, and emotional care and/or support to a person with a chronic disability (adapted from Family Caregiver Alliance Citation2006, p.5; Candy et al. Citation2011).

The abrupt onset of complex demands immediately after stroke differentiates stroke caregivers from other caregiver groups, e.g. dementia caregivers (Redfern, McKevitt, and Wolfe Citation2006; Bulley et al. Citation2009; Forster et al. Citation2013). Particularly in the beginning, stroke caregivers feel challenged due to personal deficits, e.g. lack of knowledge and skills; interpersonal concerns such as changes in their relationship with the stroke survivor and their role in the family (Grant, Hunt, and Steadman Citation2014). At a later stage organisational issues, such as identifying suitable support offers, financial stress and social isolation, are recognized as additional caregiver burdens (Adelman et al. Citation2014). Unmet support needs may impact negatively on caregivers´ health and social well-being (Adelman et al. Citation2014; Greenwood et al. Citation2010). Thus, comprehensive caregiver support programmes are required.

Stroke caregivers need informational, emotional, psychological and peer support (Wilz and Böhm Citation2007), as well as accompaniment and transition coaching (Egan, Anderson, and McTaggart Citation2010). Their needs are dynamic and change over the course of the care trajectory (Forster et al. Citation2013; Cameron et al. Citation2012; Plank, Mazzoni, and Cavada Citation2012). Personalized long-term interventions with a set of flexible components are therefore considered as the most promising (Cameron et al. Citation2012). Multicomponent interventions, including informational and psychosocial support, skills training, stress-coping strategies, caregiver counselling and problem-solving, have all been reported to be helpful (Grant, Hunt, and Steadman Citation2014; Plank, Mazzoni, and Cavada Citation2012; Cheng, Chair, and Chau Citation2014).

These types of programmes are considered as complex interventions (Craig et al. Citation2008) and require an in-depth contextual understanding (Campbell et al. Citation2007). The implementation of public health interventions in practice is challenging and ‘teething problems’ often occur (Sermeus Citation2015). Many interventions fail due to insufficient investment in their development phase (Bleijenberg et al. Citation2018). An optimisation phase is necessary before full-scale implementation and is recommended by the Medical Research Council´s (MRC) guideline for complex interventions (Craig et al. Citation2008).

Optimisation aims to improve the effectiveness of an intervention and to increase its acceptability and feasibility in practice (Sermeus Citation2015). Optimisation is a process, which may include verifying the intervention´s components (Levati et al. Citation2016), completing and fitting the components to the practice, and prioritising the components according to the objectives of the intervention (Bleijenberg et al. Citation2018). Stakeholders´ participation and engagement is considered helpful in the optimisation of a complex intervention (Bleijenberg et al. Citation2018). Cornwall´s participation model (Cornwall Citation1996), distinguishes six participation modes, and is frequently used when engaging with people in health related studies (Truman and Raine Citation2001).

Participatory Action Research (PAR) might be a suitable approach to address complexity and system needs in public health and has been increasingly applied in public health and local projects (Koshy, Koshy, and Waterman Citation2011; Ehde et al. Citation2013; Baum Citation2016). PAR is considered as a systematic, collaborative and empowering process, directed to improve practice (Cook et al. Citation2017; Meyer Citation2000). It is a qualitative methodology, which particularly concerns the role played by the professional researcher and the participants (Gibson Citation2002).

In the self-reflective inquiry process, alternating between action and critical reflection, professional researchers engage with the programme´s key stakeholders (O´Leary Citation2004; Baum, MacDougall, and Smith Citation2006). In order to remain reflective and self-conscious, professional researchers are required to reflect on the different perspectives of knowledge generation (Hessels & Van Lente, Citation2008). Banks (Citation1998) provided a typology that might be applied for both practitioner-based and professional researcher-based knowledge generation, by allocating it to one out of four perspectives: indigenous insight, indigenous outside, external inside, or external outside.

In the last decades many large-scale non-pharmacological caregiver intervention trials have been conducted, but none of them have reported on a conceptual optimisation process. For instance, TRACS in UK or ATTEND in India, both considered as complex intervention programmes (Craig et al. Citation2008), did not achieve the expected effectiveness. In a process evaluation of the TRACS programme, contextual factors including service improvement pressures and staff perceptions (e.g. acceptability) impacted negatively on the implementation (Clarke et al. Citation2014). Winstein (Citation2018) guessed that collaboration between patient, professional and caregiver was not achieved, which might have been the reason behind ATTENDs´ failure.

The ‘Timing it Right’ framework (Cameron et al. Citation2012) was based on exploring both the needs of the service providers within the system (practitioners) and family caregivers (end-users), using a qualitative study design before implementation. However, it was not reported whether there was an optimisation phase following the published study (Cameron et al. Citation2012).

The caregivers’ guide: a new stroke caregiver support programme

In Germany, the current patient-centred stroke rehabilitation process is fragmented, and characterised by multiple transition points and diverse bureaucratic, informational and logistical bottlenecks (Schuler and Oster Citation2004). This situation poses several challenges for the support system, the patient, and the caregiver (Schuler and Oster Citation2004). A new primary prevention programme – The Caregivers’ Guide – was recently developed by the Institute for Health Research and Social Psychiatry (igsp) – Catholic University of Applied Sciences North Rhine-Westphalia in Aachen, Germany (Krieger et al., Citation2017; Krieger et al. Citation2019). The programme aims to maintain the quality of life and reduce stroke caregivers´ burdens by offering professional support parallel to the current rehabilitation trajectory. Caregivers should be approached via outreach counselling as early as possible during the patients´ acute phase in the hospital. Psychosocial support and personalised information are the main ingredients of this intervention (Krieger et al., 2016). The Caregivers’ Guide fits the definitions of a complex intervention (Craig et al. Citation2008).

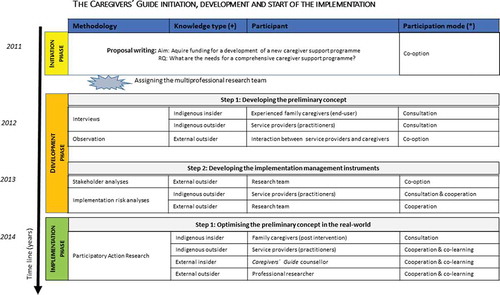

The new programme was initiated by a psychologist (Prof. Johannes Jungbauer) who wrote the funding proposal, which was based on exploring the literature and experiences with a family support programme in another region than North Rhine-Westphalia. One year later, the German Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF) approved a 36-month funding period for the programme. At this point a professional research team was created by contracting a clinical social worker (Miriam Floren, the second author) and a nurse/public health expert (Theresia Krieger, the first author). The name Caregivers’ Guide was chosen for the new programme. The new programmes´ management life cycle comprises of three phases: development, implementation and evaluation (PMI, Citation2013). In the development and early implementation phases (optimisation) various data collection methodologies, participation modes (Cornwall Citation1996) and knowledge generation types (Banks Citation1998) were applied (see ).

The development phase was split into two parts (as shown in ). First, the preliminary concept was developed by the lead of the professional research team (Krieger, Feron, and Dorant Citation2017). New knowledge was gained via explorative interviews with experienced caregivers (end-users), semi-structured interviews with practitioners (service providers), and field observations in the acute, rehabilitation and homecare settings. Modes of participation (Cornwall Citation1996) varied on a low level of participation (, right side). Analyses resulted in five preliminary Conceptual Building Blocks (CBB): `Content´, `Approach´, `Timing´, `Setting´ and `Human resources´.

Secondly, we invested in gaining a comprehensive understanding of the stakeholders and of possible implementation risks in order to develop implementation management instruments. Stakeholder- and risk-analyses were conducted using top-down and bottom-up working approaches (Krieger et al., 2019). Directed by the principal investigator, the programme´s stakeholders were identified, classified and assessed top-down and new knowledge was generated (, right side). Subsequently, a bottom-up working approach was applied. The professional research team engaged with the professional stakeholders to identify and assess possible implementation risks for the new programme. The participation modes increased and varied between consultation and cooperation (, right side).

This article reports on the optimisation of the Caregivers’ Guide support programme that was included before full-scale implementation. Our aim was to verify the completeness of the preliminary concept, to detect weaknesses and to adjust the programme to meet the real need in practice.

Methods

PAR

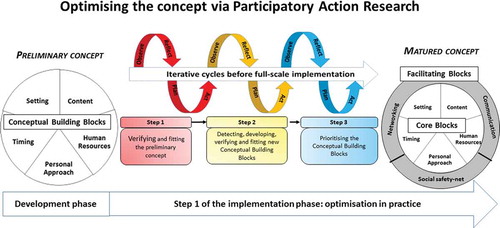

Our optimisation process was navigated by iterative PAR cycles (O´Leary Citation2004), as depicted in .

A top-down approach was chosen in the `observe´ part of the cycle. Indigenous insight, indigenous outside, external inside, and external outside knowledge (Banks Citation1998) was generated via interviews. Data were examined using qualitative content analyses with an inductive theoretical stand, resulting in subthemes and themes (Graneheim and Lundman Citation2004). Qualitative strategies were chosen to enhance trustworthiness of the results, e.g. method-, researcher- and data triangulation, as well as member checking (Meyer Citation2000; Friesen-Stroms et al. Citation2014). A bottom-up working approach was chosen for the `reflect´ and `plan´ parts. The professional research team engaged with the practitioners in a co-creative manner. Focus groups were conducted in order to reflect critically on the findings of the `observe´ phase: subthemes and themes, and new programme activities were planned. New activities were implemented top-down by the Caregivers’ Guide counsellor at an individual level when starting a new stroke caregiver counselling case, and by the research team when interacting at a system level. Cycles were repeated until all participants were verified as fitting all CBBs perfectly.

Study design

A multi-methodological qualitative study design was chosen. Interviews and focus groups were used for data collection.

The optimisation process

The optimisation of the Caregivers’ Guide preliminary concept included three steps: (1) verifying and fitting the preliminary concept, (2) detecting, developing, verifying and fitting new CBBs, and (3) prioritising all CBBs (see ).

The Caregivers’ Guide preliminary concept consisted of five CBBs, each with components characterising the CBB in detail ( – left side).

In step one, each preliminary CBB was verified and critically reflected by the practitioners and the research team with regard to its feasibility in practice. When a need for adaption arose, new actions were planned and individual and collective ideas for improvements were integrated. New subthemes and themes, possibly leading to new CBBs or components, were incorporated in the new PAR cycles. Finally, when their feasibility was confirmed, improvements were introduced into the mature concept.

During the second step, new CBBs, each with their components, were detected, developed, verified and fitted by the research team and the practitioners into practice. As a result of the qualitative content analyses in the observation steps, new subthemes with themes were detected. In order to decide on a new CBB, we translated our findings into practice by introducing them into the new PAR cycles. An iterative PAR process continued with verifying and fitting the new CBB. The new CBBs were then included in the concept.

In step three, all CBBs were prioritised according to their relevance towards achieving the intervention´s goal, resulting in the matured concept (, right side). CBBs were divided into `core´ and `facilitating´ blocks. We defined a `core CBB´ as being compulsory for the individual caregiver counselling activity, whereas a `facilitating CBB´ enables and safeguards the counsellor´s work within the system, and sustains the intervention in practice.

Participants and participation modes

Cornwall’s participation model (Citation1996) was used to indicate the level of participation of the participants. Three groups contributed with their knowledge and experiences: stroke family caregivers, practitioners, and the Caregivers’ Guide counsellor.

The first twenty stroke caregivers participated in PAR´s observe: 15 female and 5 male caregivers (12 partners, 6 adult children, one sister and one grandchild). The average age of the participants was 48 years (SD 29–75). Caregivers were consulted (mode 3, Cornwall Citation1996) during semi-structured interviews that were conducted after the last counselling session.

Sixteen practitioners, working in the regional stroke support system, possessed two roles: as interviewees and as co-researchers. Participation modes (Cornwall Citation1996) varied between consultations (mode 3) and co-learning (mode 5). Practitioners represented the acute, rehabilitation, home care and the external support system in the Aachen region ().

Table 1. Practitioners participating in the Participatory Action Research

During the `observe´ part, practitioners were iteratively interviewed on every encounter by the first or second author. They were asked to critically reflect on their experiences with the new intervention. Practitioners´ internal system knowledge and feedback was used to verify the CBBs and to detect weaknesses. During the `reflect´ and `plan´ parts, practitioners provided their input as co-researchers in focus groups. Focus groups were conducted during the inter-sectoral working group (IWG) meetings as well as the three project advancement meetings (PAM).

The Caregivers’ Guide counsellor (second author) is the intervention provider, possessing a clinical social worker background. During optimisation, she had three roles: intervention provider, interviewee, and professional researcher. During the `observe´ part, she reflected on her personal working experiences by participating in explorative interviews (consultation) with the professional researcher (first author) after a caregiver case was concluded, and she also conducted practitioner interviews. During `reflect´ and `plan´, she participated as a professional researcher (co-learning). During `act´ phase, she implemented the planned improvements.

Roles of the professional researchers

Two professional researchers were involved in this study (the first and second authors).

The first author played two roles. During `observe´ part, she interviewed the experienced caregivers, the practitioners and the counsellor (mode 3, Cornwall Citation1996) and took the lead in analysing the qualitative data. During the `reflect´ and `plan´ part, she facilitated the focus groups, mediated the co-creative analysing process, and documented the planned improvements. She was not involved in the `act´ phase.

The second author´s contributions have been explained previously (see ‘Participants and participation modes’).

Ethical considerations

During the overall programme, two dimensions of ethics in qualitative research were addressed: procedural ethics, and ‘ethics in practice’, defined as the everyday ethical issues that arise during research (Guillemin and Gillam Citation2004). Procedural ethical approval was given by the Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Applied Sciences North Rhine-Westphalia (KatHo). In addition, the COREQ research guidelines were followed (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig Citation2007).

In this study, the ‘ethics in practice’ were addressed by considering four important ethical research principles: (1) beneficence, (2) respect for autonomy, (3) justice, and (4) non-maleficence (Beauchamp and Childress Citation1989). In addition, we were guided by an action research checklist (Denscombe Citation2005, 82). Participants were emotionally and professionally empowered by the different PAR activities. The professional researchers possessed the skills to conduct, facilitate and mediate the research. Participation in this study was voluntary, no participation incentives were offered and drop-out was allowed at any moment without any negative consequences. Before the start, all participants were informed about the study, its purpose and its procedures using a participant-friendly language. Participants were included after giving consent. Caregiver interviews were held in privacy, typically in the caregiver´s home environment. Research data were anonymized by assigning participants an identifier (ID number). Data were stored on the computer using an encrypted form. Confidentiality was maintained at all times. The decisions regarding the direction of the research and probable outcomes were made in a collective manner with the participants (O´Brien Citation2001).

Results

After the programmes´ preliminary concept was developed top-down, the participatory optimisation process started with the programme being implemented in practice. The outcomes of the optimisation process per PAR cycle as well as per optimisation step is described next.

Step 1

The programme´s preliminary concept contained five CBBs ( – left side). While trying-out the programme in practice and at the same time applying PAR, all five CBBs were verified (annex 1) and needs for improvements were observed. As a result only four CBBs could be fitted to the practice: `Content, `Personal Approach´, `Timing´, and `Setting´, whereas `Human resources´ required further development ().

Table 2. Verifying and fitting the preliminary Conceptual Building Block `Human resources´ using PAR

Table 3. Detecting, developing, verifying and fitting the Caregivers’ Guide new Conceptual Building Blocks using PAR

The preliminary CBB `Content´ contained `psychosocial advice´ and `personalised information´. After its verification, only some adjusting was needed, resulting in the addition of three practical elements: extending the first counselling session with personalised needs assessment, providing a first aid check list, and using an information tool box.

Before optimisation `Personal approach´ included four components: participation, outreach counselling, face-to-face communication, and focal person system (Annex 1 – left side), all of which were verified as being important. However, outreach counselling, face-to-face communication and participation had to be refined (Annex 1 – right side).

Outreach counselling was refined by adding the word `flexible´, to accommodate differences in professional viewpoints and working attitudes between the two acute hospitals.

The component `face-to-face´ was broadened to `direct communication´. Both groups, the co-researchers and the professional research team, were convinced that face-to-face communication was the best counselling approach. However, they decided that telephone support should be offered when a face-to-face session was not possible.

Caregivers have shown limited personal manageability directly post-stroke, which led us to modify the component `participation´ into `active engagement´.

`Timing´ contained long-term support across all phases that required specification to fit to the practice. Co-researchers and the counsellor indicated that caregivers needed flexible long-term support, as the stroke rehabilitation trajectory differs from one case to the other. Practitioners recommended that support should not be provided prior to the fifth day post-stroke. The first counselling session, requiring approximately 90–120 minutes, was perceived as the ‘most important’ by both the counsellor and stroke caregivers, whereas the following sessions could be completed in 60 minutes.

Caregivers welcomed having the opportunity to decide when to end their personalised counselling process. However, an average of seven-month counselling was agreed to be necessary in practice.

Before optimisation, `Setting´ included the component `flexibility´, which meant offering caregiver support at a place convenient to the caregivers. This component appeared to be ‘too general’ for the practitioners and the counsellor, and was adjusted to `flexible place of counselling´.

The preliminary CBB `Human resources´ described the Caregivers’ Guide counsellors’ requirements and included `professional support´, `social skills´, and `personality traits´, which were all confirmed to be crucial. However, from critical observation and reflection, important new insights emerged (see ). Two additional components: `continuous capacity building´ and `on-going supervision´, were detected, verified and fitted into the mature concept.

Step 2

Further observation cycles resulted in detecting, verifying and fitting three new CBBs (). `Communication´ and `Network building´ were detected during step 1 of the optimisation phase within the CBB `Human resources´ (), whereas `Social safety-net´ was first detected when the concept was verified in practice.

The new CBB `Communication´ contains two components: external and internal communication. External communication involves activities necessary to augment the visibility, transparency, marketing, and credibility of the programme. Internal communication embraces activities aimed at assuring counsellor accessibility to caregivers, and establishing a personalised communication within the caregiver-patient dyad. Communication was perceived to be vital by all participants, since it enables, supports and safeguards the programme at an individual, professional and support system level.

`Network building´ contains three components: professional-, interprofessional-, and scientific network building. It provides the base for disseminating knowledge and exchanging ideas, as well as safeguarding and connecting the intervention programme with the system. The implementation of the `stakeholder-risk atlas´ (Krieger et al., 2019) was a helpful instrument in guiding the counsellor during her day-to-day interaction with the multiple stakeholders.

`Social safety-net´ consists of two components: peer group and emergency assistance. It was first perceived by the caregivers, then subsequently by the practitioners and the research team, to be essential in providing caregivers with the security needed to master their caregiving role. The possibility of establishing a stroke caregiver peer group was explored, resulting in the group’s foundation. At the end of each counselling trajectory, caregivers were encouraged to join this group. Moreover, after learning that caregivers were worried about the occurrence of a re-infarct, we agreed that emergency assistance should be offered after the client´s discharge, e.g. via telephone counselling.

Step 3

Optimisation resulted in the mature concept, in which all eight CBBs were prioritised by the practitioners and the research team. `Content´, `Human resources´, `Personal Approach´, `Timing´, and `Setting´ were designated to `Core blocks´, whereas `Communication´, `Network building´ and `Social safety-net´ were chosen to serve as facilitating blocks (see ).

We gained a multi-perspective conceptual understanding through PAR. We generated new knowledge from four perspectives (Banks Citation1998): (1) indigenous insights were provided by family caregivers, which reflected on their individual experiences post intervention; (2) indigenous outside perspectives were gained by practitioner engagement, reflecting on their experiences with caregivers enrolled in the new programme within their own organization; (3) external insides were contributed by the Caregivers’ Guide counselor, who reflected on the daily working experience with the family caregivers while being affiliated to the academic organization; and (4) external outside perspectives were gathered by the primary investigator, who belonged to the academic organization and had not been working in the regional stroke support system.

Discussion

The new programme was initiated and developed with low participation grades for the key stakeholders that are the service providers and end-users. It was therefore uncertain if it addresses the needs at an individual and system level. Consequently, before full scale implementation, we introduced an optimisation phase guided by a PAR approach. We aimed to verify the maturity of the preliminary concept and fit it to the needs in practice. Optimisation included three steps: (1) verifying and fitting the CBBs of the preliminary concept, (2) detecting, developing, verifying and fitting new CBBs, and (3) prioritising all the CBBs.

Optimisation resulted in the matured concept, comprising eight CBBs: five of which were core, and three facilitating. In four of the five preliminary CBBs, alterations were made to meet the requirements of both the actual stroke support system and the caregivers. The CBB `Human Resources´ required adjustments. `Continuous capacity building´ and `Professional supervision´ (). The components `Communication’ and `Network building’ were moved from the CBB `Human resources´ to two separate blocks, since their importance for the programme became apparent (). `Social safety-net´ emerged as a new CBB (), resulting in establishing a stroke caregiver `peer group´ and offering `emergency assistance´ for discharged clients. Finally, all CBBs were prioritized. The five preliminary CBBs were considered to be `core elements´ for the individualised caregiver support, and the three new CBBs as `facilitating´ since they enable the counsellor´s work and interlink and safeguard the new programme with the intricate stroke support system () during implementation.

Optimisation process

The implementation of a complex programme in practice, especially in public health, is considered a `black box´ (Sermeus Citation2015). An insufficiently developed programme or conceptual weaknesses may endanger the implementation in practice, and subsequently affect its effectiveness (Bleijenberg et al. Citation2018; Chalmers and Glasziou Citation2009). We are in agreement with Greenwood-Lee et al. (Citation2016) in suggesting that developing a programme without trying it out in practice seems to be problematic. The outcomes of our study illustrate that developing a `state-of-art´ family caregiver support concept in theory alone was not sufficient (, preliminary concept).

The in-vivo optimisation strategy (Palmer et al. Citation2013) allowed us early on to acquire real-life experiences. Conceptual strengths and weaknesses (Levati et al. Citation2016), as well as practical ‘teething problems’, were detected early on and an immediate response to these was possible. By systematically verifying the new concept´s completeness and feasibility in practice, a conceptual maturation was achieved, as proposed by Bleijenberg et al. (Citation2018). The outcomes of our study show that investing in an optimisation phase before full-scale implementation may be helpful for complex public health programmes.

Our experiences support those of Craig et al. (Citation2008) in recognising the development of a complex intervention as an iterative process. Our top-down developed preliminary concept did not adequately address the system´s needs (Krieger, Feron, and Dorant Citation2017). In retrospect, this might be attributed to the fact that the Caregivers’ Guide counsellor was affiliated to the academic organisation and not to the regional stroke support system. Therefore, insufficient internal system knowledge was available to address the systems´ needs. The new insights gained came from giving more attention to the system, as suggested by Hoddinot, Britten, and Pill (Citation2010). We applied a holistic and systems-thinking approach (WHO Citation2009; Waldman Citation2007), since a reductionist approach or silo-thinking (Quigley Citation2002; Leischow et al. Citation2008) may be insufficient when dealing with complexity. Systems-thinking and holistic approaches in public health emphasise the importance of transdisciplinary stakeholder engagement as well as relationship building between individuals and organisations (Leischow et al. Citation2008). However, investing in an optimisation phase requires time, human resources, professional skills, and stakeholders´ commitment. Twenty caregivers, sixteen practitioners and two professional researchers contributed in this. The three optimisation steps were completed over a 20-month timespan.

This article provides a practical example of an optimisation process of a complex public health programme. The MRC guideline highlights the value of modelling and optimising (Craig et al. Citation2008). Unfortunately, practical examples of complex interventions´ optimisation processes are rarely published (Bleijenberg et al. Citation2018), even though they are of clear value to all groups involved in the new programme.

During our optimisation process, the key stakeholders of the new programme (Krieger et al., 2019) were considered to possess the power to facilitate or hinder the implementation of the new programme (Caron Citation2014). Consequently, we invested in stakeholder engagement, which led to achieve mutual understanding and trust among the participants, as proposed by Jeffery (Citation2019) and Pandi-Perumal et al. (Citation2015). We enabled intensive stakeholder dialogues, advocated as `best practice´ by Caron (Citation2014). As a result, our stakeholders provided valuable feedback, which increased our in-depth understanding of the dynamic and intricate support system (Burton et al. Citation2008). However, in addition to resources, e.g. time, and professional skills, stakeholder engagement additionally requires an open-minded and constructive working climate (Jeffery Citation2019). The capability for critical reflection is required from all participants, which may be incompatible with the procedures or working traditions within some organisations, societies or cultures (D´Cruz et al., Citation2007; MacDonald Citation2012; Hofstede Citation2003).

Methodological considerations

For the purpose of this study PAR appeared to be the correct approach.

Through PAR, we achieved a long-term engagement among the professional research team and the co-researchers, as promoted by O´Brien (Citation2001). All participants experienced PAR as an interactive and encouraging process, as predicted by Baum (Citation2016). This approach required the strong commitment of all participants. High participation grades were experienced as crucial to reduce the asymmetry of the professional researchers´ power, as promoted by Galuppo, Gorli, and Ripaonti (Citation2011). The mediating attitude of the professional researcher, the conflict awareness and applying conflict resolution skills, as well as investing in a positive and an open-minded working atmosphere, helped to reduce emotional clashes and resulted in building trust. Through PAR, co-researchers were empowered to provide critical feedback on the new concept´s maturity (MacDonald Citation2012; Meyer Citation2000). PAR fostered the collaboration among the practitioners and the professional research team, as predicated by MacDonald (Citation2012), which led to a better understanding of the system´s needs.

PAR has several strengths, including bridging the gap between theory and practice (Buul et al. Citation2014) and providing the opportunity to generate new caregiver-specific, contextual and systemic knowledge in a co-creative way (Baum Citation2016; Greenhalgh et al. Citation2016). However, our experiences showed that PAR is time- and resource-consuming, as was also experienced by Young (Citation2006). Due to the complexity of our programme, multiple iterative cycles were necessary. The PAR approach needs to be sufficiently communicated within the system. The professional superiors must be convinced of the approach in order to guarantee continuous commitment. Meanwhile, PAR requires from the professional researcher extended research experience, interpersonal skills and the courage to work outside the professional comfort zone (Meyer Citation2000; Denscombe Citation2005). PAR implies power sharing and acknowledging the value of generating new knowledge in a co-creative manner (Greenhalgh et al. Citation2016). Professional researchers should feel comfortable with their facilitating role instead of trying to control the process top-down. Mode 2 researchers (Nowotny, Scott, and Gibbons Citation2003) might possibly feel more attracted to this approach.

Critical reflection on participant inclusion and roles

Following the PAR ethos, one may assume that all those stakeholders affected by the programme should be involved in the interactive parts of PAR. However, in our study during `reflect´ and `plan´, we were unable to involve the family caregivers, as they are the end-users of this programme. The reason for this lays in the programme´s history, where the initial proposal was written with a conventional top-down approach and the funding was agreed on this basis. In the proposal, action research (AR) was mentioned as one element of programme development. During the programme´s advancement, the research team became increasingly aware of the importance of participation and stakeholder engagement, and consequently integrated these elements in their research activities. The P (participation) was added to AR, which was applied in the optimization phase. However, not only resource constrains but also the decisions of the ethical committee did not provide space to include the family caregivers in the PAR process with an `interactive voice´ (Mockler Citation2014). In retrospect, it might have been helpful for the entire study to also involve family caregivers in the PAR. However, the preliminary concept was developed by the interactive contribution of ‘experienced stroke caregivers’ (Krieger, Feron, and Dorant Citation2017) and the `voice´ of caregivers after receiving the intervention was included via interviews in PAR.

In their daily routine all participating practitioners experienced the gap between the actual caregivers’ needs and the current support options. Therefore, the opportunity to be actively engaged in the development of the new programme was welcomed. During the process of critical (self-) or system reflection, practitioners experienced empowerment at both professional and individual levels. However, continuous commitment in the regular PAR meetings was difficult for some participants, due to the lack of support from their superiors or shortage of staff. None of the practitioners mentioned role conflicts due to the involvement of PAR in their practical work.

For the Caregivers’ Guide counselor, role conflicts were usual, as she played three roles (see methods). She frequently received constructive criticism and also needed to self-reflect on her daily performance. Especially at the beginning of the implementation phase, some ‘teething problems’, e.g. misunderstandings, appeared. At this moment she found both the stepwise optimization and critical reflection on her performance from the professional researcher to be helpful. However, she also perceived that her professional performance improved and that her capacity of managing conflicts was enhanced. It remained a constant challenge to be `objective´ in her researcher role.

The professional researcher was assigned to a different role than in a classical top-down design (see methods), and she possessed a mode 2 researcher profile. She perceived her new facilitator role both encouraging, as predicted by Meyer (Citation2000), and beneficial in gaining internal system knowledge. Moreover, she perceived a professional empowerment. In her previous professional career she experienced that key stakeholders´ participation in different programme phases, e.g. HIV programme initiation, was crucial for fitting the programme to the needs at an individual and system level. Consequently, she was confident that the participation mechanisms will also be applicable in the German stroke support system.

Participation, multiperspective understanding and multimethodological design

Cornwalls´ participation model (Citation1996) was applied to indicate the different participation modes in the different parts of PAR and within the three groups of participants as this model is focussing on participation in research. We felt that this clarification was worthwhile, as the term `participation´ is used nowadays inflationary. Our participation modes ranged between co-option and co-learning (mode 1–5), depending on the participant group, e.g. caregiver vs professional, and PAR phase, e.g. `observe´ vs `reflect´. Achieving a co-learning atmosphere fostered the mutual understanding for the needs of all participants: family caregivers (end-users), practitioners of the stroke support system (service providers), and the counsellor (intervention provider). Participation was considered to be an important step for improving the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention. Higher modes were experienced as more valuable by both the co-researchers and the research team with regard to the research outcomes.

A multiperspective understanding was achieved as a result of the PAR process and valuable knowledge was gathered from four perspectives (Banks Citation1998). Researcher’s reflexivity was complemented and critically reflected from the co-researchers. The collaboration between `insiders´ and outsiders´ arose from gaining a comprehensive picture (Anderson and Jones (Citation2000) of the needs at both individual and system levels.

We applied a qualitative multi-methodological design (Morse Citation2010) with two different data collection methods, namely interviews and focus groups. This ‘methodological pluralism’ (Baum Citation2016) helped us to gain a greater understanding of the actual needs in practice, as predicted by Thurmond (Citation2001). Using more than one method helped us to take advantage of the strengths of both, as reported by Creswell (Citation2009). Moreover, it augmented the trustworthiness of this study (Phillips et al. Citation2014). By first analysing each dataset separately, and then integrating the findings in the CBBs, we achieved data convergence and complementarity (Greene, Caracelli, and Graham Citation1989). In order to assure rigor, we triangulated our data, which in providing a multiperspective perception of the concept´s maturity, as advocated by Morse (Citation2010). Professional stakeholders were empowered to critically reflect on different findings, also known as ‘member checking’ (Meyer Citation2000). Our study achieved high democratic validity as a result of early stakeholder engagement.

Conclusion

Our complex caregiver support programme benefited from the optimisation phase in practice via PAR before full-scale implementation. The PAR approach was considered as appropriate for fitting the new programme to the complex needs at both individual and system levels. Its iterative process resulted in verification and testing of the preliminary concept, detecting conceptual weaknesses and practical ‘teething problems’, adjusting the components to the practical needs, and prioritizing the different CBBs. The preliminary concept with its five CBBs was improved, resulting in a matured concept containing eight CBBs: five core, concentrating on the individual caregiver counselling process; and three facilitating, safeguarding and interlinking the new programme with the actual support system.

Professionals from the stroke support system contributed as co-researchers and their engagement was considered as crucial during optimisation. Applying different participation modes and generating knowledge from different perspectives was necessary for translating findings from theory into practice. Methodological pluralism was compulsory to counterbalance the weaknesses of each method.

Author contribution

All authors revised the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version. MF, FF and ED participated in reflecting analysis, interpreting data. MF and TK contributed in data collection and primary analyses. ED contributed in designing the manuscript. TK participated in conception, design and drafting the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The board of the University of Applied Sciences North Rhine Westphalia and the Ethic Committee of the University Hospital Aachen provided ethical approval.

REAC-2018-0112.R2_Annex_1.docx

Download MS Word (28.8 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank the participating stakeholders of our programme for their contribution. The presented study stems from the research project `The Caregivers’ Guide’, conducted under the direction of Prof. Dr. Johannes Jungbauer, at the Catholic University North-Rhine Westphalia (Germany).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adelman, R., L. Tmanova, D. Delegado, S. Dion, and M. Lachs. 2014. “Caregiver Burden. A Clinical Review.” JAMA 311: 1052–1059. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.304.

- Anderson, G., and F. Jones. 2000. “Knowledge Generation in Educational Administration from the Inside-out: The Promise and Perils of Site-based, Administrator Research.” Educational Administration Quarterly 36: 428–464. doi:10.1177/00131610021969056.

- Bakas, T., P. Clark, M. Kelly-Hayes, R. King, B. Lutz, and E. Miller. 2014. “Evidence for Stroke Family Caregiver and Dyad Interventions: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association.” Stroke 45: 2836–2852. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000033.

- Banks, J.A. 1998. “The Lives and Values of Researchers: Implications for Educating Citizens in a Multicultural Society.” Educational Researcher 27 (7): 4–17. doi:10.3102/0013189X027007004.

- Baum, F. 2016. “Power and Glory: Applying Participatory Action Research in Public Health. (Editorial).” Gaceta Sanitaria 30: 405–407. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.05.014.

- Baum, F., C. MacDougall, and D. Smith. 2006. “Participatory Action Research.” Journal of Epidemiological Community Health 60: 854–857. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.028662.

- Beauchamp, T.L., and J.F. Childress. 1989. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 3rd ed. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bleijenberg, N., J. de Man-van Ginke, J. Trappenburg, R. Ettema, C. Sino, N. Heim, T. Hafsteindóttir, D. Richards, and M. Schuurmans. 2018. “Increasing Value and Reducing Waste by Optimizing the Development of Complex Interventions: Enriching the development Phase of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 79: 86–93. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.12.001.

- Bulley, C., J. Shiels, K. Wilkie, and L. Salisbury. 2009. “Carer Experiences of Life after Stroke – A Qualitative Analysis.” Disability & Rehabilitation 32: 1406–1413. doi:10.3109/09638280903531238.

- Burton, H., M. Adams, R. Bunton, and P. Schroder-Back. 2008. “Developing Stakeholder Involvement for Introducing Public Health Genomics into public Policy.” Public Health Genomics 12: 11–19. doi:10.1159/000153426.

- Buul, L., J. Sikkers, M. Agtmael, M. Kramer, J. Steen, and C. Hertogh. 2014. “Participatory Action Research in Antimicrobial Stewardship: A Novel Approach to Improving antimicrobial Prescribing in Hospitals and Long-term Facilities.” Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 69: 1734–1741. doi:10.1093/jac/dku068.

- Cameron, J., G. Naglie, F. Sivler, and M. Gignac. 2012. “Stroke Family Caregivers’ Support Needs Change across the Care Continuum: A Qualitative Study Using the Timing It Right Framework.” Disability & Rehabilitation 35: 315–324. doi:10.3109/09638288.2012.691937.

- Campbell, N., E. Murray, J. Darbyshire, J. Emery, A. Farmer, F. Griffiths, B. Guthrie, H. Lester, P. Wilson, and A. Kinmonth. 2007. “Designing and Evaluating Complex Interventions to Improve Health Care.” BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 334: 455–459. doi:10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE.

- Candy, B., L. Jones, R. Drake, B. Leurent, and M. King. 2011. “Interventions for Supporting Informal Caregivers of Patients in the Terminal Phase of a Disease.” Cochran Database Systematic Review 6: CD007617.

- Caron, F. 2014. “Project Planning and Control: Early Engagement of project Stakeholders.” Journal of Modern Project Management 2: 84–97.

- Chalmers, I., and P. Glasziou. 2009. “Avoidable Waste in the Production and Reporting of Research Evidence.” Lancet 374: 86–90. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60329-9.

- Cheng, H., S. Chair, and J. Chau. 2014. “The Effectiveness of Psychosocial Interventions for Stroke Family Caregivers and stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Patient Education Counselling 95: 30–40. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.01.005.

- Clarke, D., R. Hawkins, E. Sadler, G. Harding, C. McKevitt, M. Godfrey, L. Dickerson, et al. 2014. “Introducing Structured Caregiver Training in Stroke Care: Findings from the TRACS Process Evaluation Study.” BMJ Open (2014 (4): e004473. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004473.

- Cook, T., J. Boote, N. Buckley, S. Vougioukalou, and M. Wright. 2017. “Accessing Participatory Research Impact and Legacy: Developing the Evidence Base for participatory Approaches in Health research.” Educational Action Research 25 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1080/09650792.2017.1326964.

- Cornwall, A. 1996. “Towards Participatory Practice: Participatory Rural Appraisal and the participatory Process.” In Participatory Research in Health: Issues and Experiences, edited by K. de Koning and M. Martin, 96. London: Zed Books.

- Craig, P., P. Dieppe, S. Macintyre, S. Michie, I. Nazareth, and M. Petticrew. 2008. “Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: The New Medical Research Council Guidance.” BMJ Clinical Research (Ed) 337: a1655.

- Creswell, J. 2009. “Mapping the Field of Mixed Methods Research.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 3: 95–108. doi:10.1177/1558689808330883.

- D’Cruz, H., P. Gillingham, and S. Melendez. 2007. “Reflexivity, Its Meanings and Relevance for Social Work: A Critical Review of the Literature.” British Journal of Social Work 37: 1.

- Denscombe, M. 2005. The Good Research Guide for Small-scale Social research Projects. 2nd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Egan, M., S. Anderson, and J. McTaggart. 2010. “Community Navigation for Stroke Survivors and Their Care Partners: Description and Evaluation.” Top Stroke Rehabilitation 17: 183–190. doi:10.1310/tsr1703-183.

- Ehde, D., S. Wegener, R. Williams, P. Ephraim, J. Stevenson, P. Isenberg, and E. MacKenzie. 2013. “Developing, Testing, and Sustaining Rehabilitation Interventions via Participatory Action Research.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 94: S30–42. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.10.025.

- Family Caregiver Alliance. 2006. “Caregiver Assessment: Principles, Guidelines, and Strategies for Change.” Report from a National Consensus Development Conference 2006, Accessed April 11 2018. www.caregiver.org/sites/caregiver.org/files/pdfs/v1_consensus.pdf

- Forster, A., J. Dickerson, J. Young, A. Patel, L. Kalra, and J. Nixon; TRACS Trial Collaboration. 2013. “A Structured Training Programme for Caregivers of Inpatients after Stroke (TRACS): A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial and Cost-effectiveness Analyses.” Lancet 382: 2069–2076. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61603-7.

- Friesen-Stroms, J., A. Moser, S. von der Loo, A. Beurskens, and G. Bours. 2014. “Systematic Implementation of Evidence-based Practice in a Clinical Nursing Setting: A Participatory Action Research Project.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 24: 57–68. doi:10.1111/jocn.12697.

- Galuppo, L., M. Gorli, and S. Ripaonti. 2011. “Playing Dissymmetry in Action Research: The Role of Power and Differences in Promoting Participatory Knowledge and Change.” Systemic Practice and Action Research 24 (2): 147–164. doi:10.1007/s11213-010-9181-5.

- Gibson, M. 2002. “Doing a Doctorate Using a Participatory Action Research Framework in the Context of Community Health.” Qualitative Health Research 12 (4): 546–588. doi:10.1177/104973202129120061.

- Graneheim, U., and B. Lundman. 2004. “Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measurement to Achieve Trustworthiness.” Nurse Education Today 24: 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Grant, J., C. Hunt, and L. Steadman. 2014. “Common Caregiver Issues and Nursing Interventions after a Stroke.” Stroke 45: e151–e153. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005094.

- Greene, J., V. Caracelli, and W. Graham. 1989. “Towards a Conceptual Framework for Mixed-method Evaluation Designs.” Education and Policy Analysis 11: 255–274. doi:10.3102/01623737011003255.

- Greenhalgh, T., C. Jackson, S. Shaw, and T. Janamian. 2016. “Achieving Research Impact through Co-creation in Community-based Health Services: Literature Review and Case Study.” The Milbank Quarterly 94: 392–429. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12197.

- Greenwood, N., A. Mackenzie, G. Cloud, and N. Wilson. 2010. “Loss of Autonomy, Control and Independence When Caring: A Qualitative Study of Carers of Stroke Survivors in the First Three Months after Discharge.” Disability & Rehabilitation 32: 125–133. doi:10.3109/09638280903050069.

- Greenwood-Lee, J., P. Hawe, A. Nettel-Aguirre, A. Shiell, and D. Marshall. 2016. “Complex Intervention Modelling Should Capture the Dynamics of Adaption.” BMC, Medical Research Methodology 16: 51. doi:10.1186/s12874-016-0149-8.

- Guillemin, M., and L. Gillam. 2004. “Ethics, Reflexivity, and “Ethically Important Moments” in Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 10 (2): 261–280. doi:10.1177/1077800403262360.

- Hessels, L. K., and H. Van Lente. 2008. “Re-thinking New Knowledge Production: A Literature Review and a Research Agenda.” Research Policy 37 (4): 740–760.

- Hoddinot, J., J. Britten, and R. Pill. 2010. “Why Do Interventions Work in Some Places and Not Others: A Breastfeeding Support Group Trial?” Social Science & Medicine 70: 769–778. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.067.

- Hofstede, G. 2003. Cultures and Organizations. Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival. London: Profile Books .

- Jeffery, N. 2019. “Stakeholder Engagement: A Road Map to Meaningful Engagement.” Doughty Centre ´How to do Corporate Responsibility´ Series. 2009. Accessed 10 February 2019. https://www.som.cranfield.ac.uk/som/dinamic-content/media/CR%20Stakeholder.pdf

- Koshy, E., V. Koshy, and H. Waterman. 2011. Action Research in Health Care. London: SAGE.

- Krieger, T., F. Feron, and E. Dorant. 2017. “Developing a Complex Intervention Programme for Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors: The Caregivers’ Guide.” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science 31: 146–156. doi:10.1111/scs.12344.

- Krieger, T., F. Feron, N. Bouman, and E. Dorant. 2019. “Developing Implementation Management Instruments in a Complex Intervention for Stoke Caregivers Based on Combined Stakeholder and Risk Analyses.” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. doi:10.1111/scs.12723.

- Leischow, S., A. Best, W. Trochim, P. Clark, R. Gallagher, S. Marcus, and E. Matthews. 2008. “Systems Thinking to Improve the Public’s Health.” American Journal for Preventive Medicine 35: S196–S203. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.014.

- Levati, S., P. Camplell, R. Frost, N. Dougall, M. Wells, C. Donaldson, and S. Hagen. 2016. “Optimisation of Complex Health Interventions Prior to a Randomized Controlled Trial: A Scoping Review of Strategies Used.” Pilot and Feasibility Studies 2: 17. doi:10.1186/s40814-016-0058-y.

- MacDonald, C. 2012. “Understanding Participatory Action Research: A Qualitative research Methodology Option.” Canadian Journal of Action Research 13: 34–50.

- Meyer, J. 2000. “Qualitative Research in Health Care. Using qualitative Methods in health Related Action research.” British Medical Journal 320: 178–181. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178.

- Mockler, N. 2014. “When `Research Ethics´ Become `everyday Ethics´: The Intersection of Inquiry and Practice in Practitioner research.” Educational Action Research 22 (2): 146–158. doi:10.1080/09650792.2013.856771.

- Morse, J. 2010. “Simultaneous and Sequential Qualitative Mixed Methods Design.” Qualitative Inquiry 16: 483–491. doi:10.1177/1077800410364741.

- Nowotny, H., P. Scott, and M. Gibbons. 2003. “Introduction: `mode 2´ Revisited: The New Production of Knowledge.” Minerva 41: 179. doi:10.1023/A:1025505528250.

- O´Brien, R. 2001. “An Overview of the Methodological Approach of Action Research.” Accessed 29 January 2019. http://www.web.ca/~robrien/papers/arfinal.html

- O´Leary, Z. 2004. The Essential Guide to Doing Research. London: SAGE.

- Palmer, J., G. Bozas, A. Stephens, M. Johnson, G. Avery, and L. Toole. 2013. “Developing a Complex Intervention for the Outpatient Management of Incidentally Diagnosed Pulmonary Embolism in Cancer Patients.” BMC Health Service Research 13: 235. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-235.

- Pandi-Perumal, S., S. Akhter, F. Zizi, G. Jean-Loui, C. Ramasubramanian, R. Freeman, and M. Narasimhan. 2015. “Project Stakeholder Management in Clinical Research Environment How to Do It Right. Review.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 6: 71. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00071.

- Phillips, C., K. Dwan, J. Hepworth, C. Pearce, and S. Hall. 2014. “Using Qualitative Mixed Methods to Small Health Care Organizations while Maximizing Trustworthiness and Authenticity.” BMC Health Service Research 14: 559. doi:10.1186/s12913-014-0559-4.

- Plank, A., V. Mazzoni, and L. Cavada. 2012. “Becoming a Caregiver: New Family Caregivers´ Experience during Transition from Hospital to Home.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 21: 2072–2082. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04025.x.

- PMI - Project Management Institute. 2013. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide). 5th ed. Atlanta: Project Management Institute, 391–413.

- Quigley, W. 2002. “The Health of health Care. Quoting Martin Hickey, Former Lovelace CEO.” Albuquerque Journal Outlook 1: 3–9.

- Redfern, J., C. McKevitt, and C. Wolfe. 2006. “Development of Complex Interventions in Stroke Care: A Systematic Review.” Stroke 37: 2410–2419. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000237097.00342.a9.

- Schuler, M., and P. Oster. 2004. “Versorgung Von Patienten Mit Und Nach Akutem Schlaganfall Aus Geriatrischer Sicht. (Supporting Patients during and after Acute Stroke from a Geriatric Point of View).” Gesundheit Gesellschaft Wissenschaft 3: 23–28.

- Sermeus, W. 2015. “Modelling Process and Outcomes in Complex Interventions.” In Complex Interventions in Health, edited by D. Richards and I. Hallberg, 116–191. New York: Routledge.

- Thurmond, V. 2001. “The Point of Triangulation.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 33: 253–258. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00253.x.

- Tong, A., P. Sainsbury, and J. Craig. 2007. “Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups.” International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19: 349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Truman, C., and P. Raine. 2001. “Involving Users in Evaluation: The Social Relations of User Participation in Health Research.” Critical Public Health 11: 215–229. doi:10.1080/09581590110066667.

- Waldman, J. 2007. “Thinking Systems Needs System Thinking. Research Paper.” Systems Research and Behavioral Science 24: 271–284. doi:10.1002/sres.828.

- Wetzstein, M., A. Rommel, and C. Lange. 2015. “Pflegende Angehörige - Deutschlands Größter Pflegedienst. (Family Caregivers - Germany´s Biggest Ambulant Health Care Service).” Gesundheitsberichterstattung Kompakt, Berlin: Robert Koch Institute.

- WHO. 2009. “World Health Organization Systems Thinking for health systems Strengthening.” D. Savigny and T. Adam (eds); Accessed 11 January 2019. www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44204/1/9789241563895_eng.pdf

- Wilz, G., and B. Böhm. 2007. “Interventions for Caregivers of Stroke Patients: Need and Effectiveness.” Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie 57: 12–18. doi:10.1055/s-2006-951847.

- Winstein, C. 2018. “The ATTEND Trial: An Alternative Exploration with Implications for Future Recovery and Rehabilitation Trials.” International Journal of Stroke 13: 112–116. doi:10.1177/1747493017743061.

- Young, L. 2006. “Participatory Action Research (PAR): A research Strategy for Nursing?” Western Journal of Nursing Research 8: 499–504. doi:10.1177/0193945906288597.