ABSTRACT

The popularity of Participatory Action Research (PAR) increases the risk of tokenism and blurring the boundaries of what might be considered ‘good’ PAR. This became a pressing issue when we were invited by the City of Amsterdam to conduct PAR on digital inequality with vulnerable citizens in Amsterdam, within serious constraints of time and budget. We decided to take up the challenge to offer citizens an opportunity to share their needs. This paper aims to increase the transparency of the complex reality of a PAR process in order to help new researchers learn about the challenges of PAR in real-life situations, and to open up the discussion on the quality and boundaries of PAR. Though we managed to implement some core ethical principles of PAR in this project, two were particularly under pressure: democratic participation and collective action. These jeopardized collective learning and might unintentionally feed stereotypes regarding people’s capabilities. Nevertheless, this small and local study did manage to create ripples for change.

Introduction

The worldview of PAR, which gained much of its impetus in the 1940s from marginalized communities in low- and middle-income countries who were vulnerable to exploitation, is based on the notion that reality is not an objective truth to be discovered but ‘includes the way in which the people involved with facts perceive them’ (Freire Citation1982, 30). One of the core values of PAR is that knowledge is co-produced with a community; people working together to examine a problem with the goal of addressing it for the better (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR) Citation2013; Abma et al. Citation2019; Reason and Bradbury Citation2001). The idea that this approach is more likely to have a broad social impact fits well with the increasing concern, high on the agenda of funders and governments across the world, to ensure that research has a social and economic impact (Abma et al. Citation2017; Penfield et al. Citation2014). It is increasingly acknowledged, for example, that clinical and health service research failed to translate research into practice and policy (Grimshaw et al. Citation2012), did not always meet people’s needs, nor do justice to their daily reality (Chalmers et al. Citation2014; Ioannidis et al. Citation2014). PAR is also considered to respond to increasing complexity; the need for multiple perspectives and brief cyclical learning processes (Ter Haar Citation2014). Finally, the approach fits the call for knowledge democratisation, as citizens and patients increasingly demand to have a say in policy and research affecting them (Anderson Citation2017; Stirling Citation2008), and for contextual knowledge. Moreover, it acknowledges that people are experts about their own life.

Knowledge democratisation and social impact have become important dimensions in how research is funded and evaluated (Cook et al. Citation2017). This is the case for funding agencies in the Netherlands; in the past, these agencies asked the researcher to simply tick a box regarding whether they would or would not include citizens/patients. Nowadays, researchers need to explain how they are going to involve the public or patients in their research and, more recently, how they involved stakeholders in writing the research proposal (ZonMw Citation2006). This movement places further pressure on researchers – already dealing with the stress arising from limited funding opportunities (Halffman and Radder Citation2015). Not already acquainted with the approach, they quickly need to educate themselves in the principles of PAR and how to enact them.

This upsurge of interest in PAR also means that it will be stretched to fields and institutes that are not yet acquainted with the values and the necessary conditions for it to flourish, such as clinics and local governments. In other words, there is a risk of tokenism and of blurring the boundaries of what might be considered ‘good’ PAR. The increasing popularity of PAR challenges inexperienced but also more experienced PAR researchers. There is recognition that some research that calls itself participatory does not align with the core principles and basic philosophical assumptions, motivations and practices that PAR practitioners would recognise (Springett Citation2017). Moreover, there is evidence that PAR is not necessarily a good thing in itself and has even caused some major harm, creating mistrust and participation fatigue (Cooke and Kothari Citation2004; Banks et al. Citation2013).

PAR scholars place the assessment of quality and critical reflection high on the agenda (Dedding and Slager Citation2013; International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR) Citation2013; Cook et al. Citation2017; Abma et al. Citation2019; Banks and Brydon-Miller Citation2019; Abma et al. Citation2017; Lennette et al. Citation2019). These scholars point to the ideal and rhetoric of participation and call for creative solutions, asking PAR practitioners to engage in self-analysis of the tensions they encounter in conducting democratic collaborative research. There is a need to reflect critically on questions such as whether participation is always good, and always necessary. When is it good, or good enough? Does it always need to be small, local and long term, or could it also be done in a short timespan with a bigger group, for instance with the help of social media? And if participation is based on values, and is not a method, what do these values look like in practice?

The often-reported lack of extensive case description makes it hard for new PAR researchers to become acquainted with the core values of PAR and unsure of how to put them into practice, but also limits the conceptualisation of PAR processes, its impacts and quality (Springett Citation2017). As Cook (Citation2012) argues, impact is embedded in the process, which means it is not always easy to distinguish among and articulate its different forms. Moreover, scientific journals outline how researchers should report their scholarly research, set strict word limits, and work with peer reviewers who may not always see the value of extensive case descriptions. This can result in a discrepancy between what PAR researchers actually do and how they report what they do. Furthermore, in line with PAR, researchers prefer local impact and also need to please local funders and so often produce grey literature, which is harder to find in scientific databases (Jagosh et al. Citation2012).

The above critical reflections became pressing when we were asked by the City of Amsterdam to conduct a PAR process on digital inequality among citizens in order to feed into the upcoming policy for digital inclusion. Due to the political timeframe, the results needed to be available in seven months. As an experienced (PAR) researcher (CD) and a new scholar in the field (NG) we immediately knew that involving ‘citizens of Amsterdam’ in seven months, with funding for almost one full-time equivalent (FTE) researcher, would be ‘challenging’. Meaningful participation would be hard to achieve. The municipality, however, could not offer more time or money; their staff were curious to see what new insights participation would bring to their understanding, but could not yet sell the ‘new’ approach to higher levels to free up more funds. Above all, they had to inform the alderman about possible policy implications and priorities for action within the scheduled time.

This posed a dilemma; not accepting the assignment would mean that policy-makers would continue to take important decisions for citizens in vulnerable situations, while accepting the opportunity might lead to tokenism, devaluation of an approach that is still critically viewed for being less scientific (Cook Citation2012) and might harm our personal careers as scientists. After careful deliberation, we decided to take up the challenge in order a) to give citizens an opportunity to share their experiences and needs and b) to make policy-makers more aware of the value of participation and the often complicated situations in which people live. After the project was finished, we received some critical questions about the generalizability of the findings, but the report was largely well received. The findings attracted attention at higher policy levels, and helped to set a new national policy on digital inclusion. Nevertheless, the question remained for us of whether we should ever again try to do PAR under such constraints. Therefore, we decided to reflect on our own experiences in PAR process: to what extent did we manage to put (some of) the core ethical principles of PAR into practice and actually contribute to change? We invited two ‘critical’ friends in the writing process (Kember et al. Citation1997), namely PAR researchers (JB and TA), who have extensive professional and experiential knowledge, to critically reflect on our process and lessons learned.

This paper aims to increase the transparency of the complex reality of a PAR process in order to help new researchers learn about the messy process of PAR in real-life situations, the often problematic and contradictory relationships and the prerequisites, and at the same time to open up discussion about the quality and stretching boundaries of PAR. Before we share our experiences in a PAR project under restraining conditions, we first shortly summarise the basic principles of PAR and provide some context for the case.

Short summary of the basic principles of PAR

Participatory Action Research builds on a long and diverse history drawn from a range of disciplines, each of which has informed and developed its own understanding of what PAR is. Fundamental to PAR is a ‘shared recognition that science is more than adherence to specific epistemological or methodological criteria, but is rather a means for generating knowledge to improve people’s lives’ (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR) Citation2013, 5). The aim of involving multiple perspectives and different forms of knowledge (experiential, practical, traditional and scientific) is to develop a richer and more meaningful portrayal of the subjects of research, and to facilitate a learning platform for representing the multiple experiences, hopes, and fears of those directly involved as route to reducing (health) inequalities (Abma et al. Citation2019). While this will depend on the focus of the study, stemming from an emancipatory movement the focus is on the poor and marginalized in society, who seldom have a voice in defining the problem and solutions. The focus is on shared learning and action for social change (Cornwall and Jewkes Citation1995; Khanlou and Peter Citation2005; Abma et al. Citation2019), within the local context. It is not a ‘quick fix’ and it does not follow a linear and predictable process. On the contrary, its endpoint is often open (Piggot-Irvine, Rowe, and Ferkins Citation2015).

We used the key ethical principles of PAR, as defined by the International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR), to reflect on the process and the outcomes. These principles, summarised in , do not suggest how to act, but need to be interpreted in the light of particular circumstances, and can be considered as being on a continuum, an ideal for which to strive – the ICPHR emphasis on seeking maximum participation and collective action based on joint insights (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR) Citation2013).

Table 1. The seven underpinning values and ethical principles of PHR, as defined by ICPHR (Citation2013)

Methods: a case study concerning the development of a policy agenda for digital inclusion

The project was funded by the poverty director at the City of Amsterdam. Based on a former project with children living in poverty (Sarti et al. Citation2017; Sarti, Schalkers, and Dedding Citation2015), the first author (CD) was invited to attend a meeting in which choices would be made on how to accommodate the needs of children in relation to digital inclusion. A group of professionals attended the meeting. Many had direct experience with the so-called ‘target group’, and shared ideas on how best to spend the available money. Among others, the idea was to develop educational apps for toddlers and to expand the current free laptop arrangement to young children.Footnote1 Practical questions of what kind of devices children actually need could not be answered, either in relation to school or to their social lives, which was also acknowledged as important. Therefore, the first author along with an industrial designer who had worked with the municipality in the field of poverty reduction, were invited to collaborate in a ‘participatory action study’. While we repeatedly stressed that for participatory and quality purposes we needed to make choices in the so-called ‘target group’, this was not possible. On the contrary, the project design rapidly expanded to not only children, but also to the experiences and needs of their parents; numbers were considered important in order to get the conclusions accepted by the policy-makers. The resulting findings should provide an overview of 1) the problem and needs of families with a low socioeconomic position (SEP) in relation to the quickly digitalizing society; and 2) concrete, and preferably swift, operational solutions.

Digital inequality is a complex social problem that transcends several policy domains, in this case poverty reduction, education and welfare, spanning the entire political spectrum, each party with its own – often conflicting – views and agenda in relation to felt responsibility, need and kind of action. The upcoming elections, 11 months after the start of the project, increased the pressure to profile themselves well – who wants to own a complex problem that defies simple solutions in an election period? This made it even more important to present a rewarding perspective for all policy-makers involved.

The budget covered for both senior and a junior researcher (together 0.9 FTE), research materials and some money to reimburse participants for their time. We also pushed for financial support to create an outstanding end product, complete with visuals. Given the complexity of the problem, the political sensitivity and the lack of time, we knew from the start that it was a huge challenge. With the help of an intern, we engaged volunteers and professionals working with families in deprived areas of Amsterdam and, through their networks, we involved parents and children living in such areas. The research question and design were developed by the researchers in cooperation with the policy-makers. In the first phase of the research, we focused on understanding the problem, as experienced by families. We conducted formal interviews with professionals (n = 42), parents (n = 10) and children (n = 3) from five deprived neighbourhoods in Amsterdam, and enlarged our understanding through participant observations, informal interviews and work sessions (). In the second phase, we focused on co-creating solutions. In total three co-creation sessions were organized with volunteers and professionals (n = 64). The findings of the co-creation sessions were discussed in six focus groups: four with mothers (n = 21), and two with children (n = 30) ().

Table 2. An overview of research activities

The methodology included several cycles of critical reflection. We started with critical re-reading of the journal that we (CD and NG) kept during the research process, comparing the research design and the actual process with the PAR literature and the seven ethical principles of ICPHR, identifying the main dilemmas and issues encountered. Second, we invited two critical friends (JB and TA) to read a first draft of our manuscript to identify issues and concerns with the process followed. Thereafter, we reflected on the process with the principal and the policy project leader in extended interviews, which lasted for approximately one hour and were transcribed verbatim. During the analytical process, we alternated between (re-)reading of the data and the critical questions, and open coding and final code categorisation was based on the ICPHR ethical principles.

Results

In order to do justice to the complexity of the process and for the sake of readability, we do not use the seven ethical principles as a grid, but follow the process as it has evolved in practice and the dilemma’s we faced. First, we describe the different roles of the participants in the research project. We then describe how the working relationships developed during the project. Finally, we show whether we managed to make a difference. The participants’ experiences, needs and priorities have been published in a policy report (Dedding, Goedhart, and Kattouw Citation2017) and a scientific article (Goedhart et al. Citation2019.).

The different roles of stakeholders in the project: democratic participation under pressure

Due to the short timeframe, the interest in the for policy-makers’ new approach, and the fact that the City of Amsterdam had good working relations in the field, it was decided to work closely together. We met once a week at the municipality (90–120 minutes) to discuss each step and interim findings. The policy-makers accommodated field meetings and attended some interviews and work sessions in order to learn what is at stake for whom, and to connect to other projects and departments. While working, they often reminded us of the (often shifting) focus and (interim) deadlines, as the principal explained: ‘my goal was to catch the momentum in time for the elections’, and often highlighted this in our weekly meetings: ‘If we want to submit it to the board in January, a deadline for the report in October is not on time’ [notes 4-07-2017]. Although we often explained that we needed time and flexibility for genuine participation, in order to meet and to build trust with citizens who are not familiar with research and not spontaneously willing to connect with the local government, and to learn what is actually at stake, as a team we all had to stick to these deadlines, after all: ‘The internal consultation with aldermen cannot be rescheduled […]’ [notes 7-07-2017].

Given the lack of time, it would have been easiest and most efficient to invite citizens who are already known to professional organisations, like formal educational training. However, in line with the principles of equality and inclusion, we deliberately chose also to reach people living in deprived neighbourhoods at some distance from official organizations. It was expected that they might be most affected by the digital gap, and at the same time could profit most from technological progress. We adopted no exclusion criteria in relation to language capabilities and no formal group sessions were organized. With the help of professionals and volunteers, we met people at times and places that suited their practical agendas and needs. Rather than inviting them at times and venues that suited us or clashed with theirs, we respectfully tried to fit our research activities around their schedules. We explained the purposes of the project as ensuring that future interventions and policies would fit their life-worlds and needs, and asked adults and children to share their experiences of the digital world, their needs and ideas for solutions. During the conversations, we actively explored and discussed existing interventions, such as digital training materials and a new app developed by the municipality called ‘understand the letter’. For children, we arranged an excursion to a film museum, where they learned to make a stop motion movie. We planned transport, and used the time to get to know each other and to learn about what is at stake for them. In general, these real-life meetings lasted for one or two hours.

During the project, we worked closely with volunteers linked to language and debt courses, some of them with personal experience of living in poverty. They shared their (personal) knowledge and experiences and helped to introduce the project to people living in precarious circumstances. During all phases of the project we stayed close to one welfare professional in particular, who had worked as a volunteer in her spare time for more than 10 years, to feed into the discussion, and to validate our findings and actions.

We analysed the stories using an ethnographic content analysis, ensuring that we kept an eye on the situational context and providing the opportunity iteratively to gain a more in-depth understanding. The stories and expressed needs were shared with a group of policy-makers, educators, volunteers and creative designers in three co-creation sessions in order to exchange ideas, connect to what is already happening and to develop innovative and concrete ideas. These interpretations were brought back to a group of mothers to check whether these ideas fit with their daily life, ideas, experiences, and needs. The policy-makers’ idea of investing in educational apps for young children, for example, was quickly turned down by mothers, as they believed this would damage young children’s sight. The app that was developed to help to understand difficult letters was experienced as not user-friendly, and most of all as threatening their personal comfort zone and privacy. However, the idea of developing educational vlogs about the problems they experience was seen as an opportunity some would like to try.

We tried to work together with a group of ‘experiential-experts’, who are involved in a three-year schooling trajectory in order to become professional experiential advisers in the field of poverty reduction. We visited the school to explain the purpose of the project and to see whether we could work together. At that time the schooling programme had just started, people were busy making sense of their own and others’ experiences. Some of the students were really enthusiastic about being involved in the project. Unfortunately, we could not fully invest in this relationship due to the mutually inflexible schedules. We even had to decline a request of a student for an internship, since we could not invest in a proper working relationship (integrity principle).

In we summarize the different roles of the citizens and policy-makers in the different stages of the project. It shows that we did not reach a high level of citizens’ participation, but we did so among policy-makers and, to a lesser extent, volunteers.

Table 3. Roles played by the stakeholders in the different phases of the research project

Working relations: mutual respect, active and shared learning, equality & inclusion

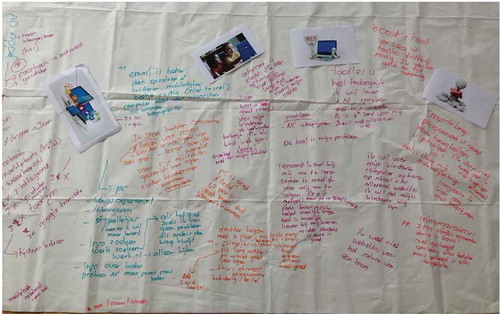

Although in their daily lives participants faced many challenges in relation to the rapidly digitalizing world, we quickly learned that for most citizens the topic was not high on their agenda. Arranging for basic needs, daily concerns, and practical caregiving tasks were more important. Besides, we often had to balance citizens’ feelings of distrust regarding the municipality, ensuring their privacy and that their information could not be used in ways they had not authorized. Rather than making private notes, we wrote on a paper tablecloth so everybody could see our notes and get an overview of the data (see ). Breaking ‘the rule’ of not writing on a tablecloth, and also learning new words and phrases, often created a relaxed atmosphere, helped to build trust and resulted in active and shared learning. We also ensured that the children were having a good time, had the opportunity to explore and expand their skills and to reflect about who we are and why we felt it is important to listen to them. Given the lack of toys in informal day care, we left our research materials behind and later sent them extra items to play with afterwards. The community centre, we closely worked with, received a gift certificate for their investment of time and sharing their knowledge, which they used for their collective food garden. Individual citizens received a gift certificate for sharing their knowledge and experiences in an interview.

Different types of knowledge – e.g. experiential, theoretical, practical, intuitive, and emotional ways of knowing – were all used and valued. We familiarized ourselves with theoretical models, such as the multiple access model of Van Dijk (Citation2005), indicating that the digital divide is a product of four factors, namely: motivational, materials, skills, and usage access. While this model turned out to be helpful for understanding the different kinds of access that might be significant, we did not use it as a rigid grid. On the contrary, we sought to familiarize ourselves with the experiences and lives of people, whether young or adult, in their specific context with the scientific theory and knowledge in our ‘backpack’.

We did not invite citizens to the co-creation session. Due to time pressure we could not create a respectful and empowering setting for them; it would have demanded extra preparation meetings with citizens in order for them to feel confident, or at least reasonably comfortable in relation to formal professionals. Indeed, two of the four volunteers who attended later commented that they felt overwhelmed by the dominance of the experts and their lack of respect, which had the effect of limiting active participation and shared learning. Though we tried to mitigate this during the meeting, we didn’t fully succeed. Partly this had to do with the fact that organizations and professionals have to compete with each other for current and future activities; (un)intentionally this increased their need to advertise their added value and ideas to the policy-makers, often overruling the more modest volunteers.

The citizens’ experiences, needs and solutions were fed into the co-creation sessions by the research team, with the help of ‘personas’, and verbally explained. Personas – semi-fictional representations – are often used in the context of industrial design to express and focus on the major needs and expectations of the most important user groups; to aid in revealing universal features and functionality; and to describe real people with their own backgrounds, goals, and values (Guo, Shamdasani, and Randa Citation2011). Though useful in the context of design, it didn’t feel right in the context of PAR. It was talking about people rather than with people, and it risked over-generalization of stereotypes, often portraying people negatively as passive and unknowledgeable. Moreover, it increased the risk of side-lining topics which were not considered relevant from the professionals’ perspective. And this might inadvertently have limited the position of the volunteers.

Making a difference and ‘collective’ action

It is not easy to distinguish and articulate the project’s impact since it is embedded in the process, demands time – the scarcest resource in this project – and so could not be evaluated with all stakeholders. However, in order to evaluate whether we managed to bring some of the core principles of PAR into action, we need to look at impact, since action and change is what PAR is about. Therefore, we summarized some of the benefits of the process for the different stakeholders, shown in .

Table 4. The benefits of the process for the different stakeholders

Interestingly, shows a relation between the depth of involvement and impact; the greatest impact was on policy-makers. Nevertheless, the process did open up alternative perspectives and courses of action. Some of the ideas at the start, e.g. to invest in education apps for young children, were not followed up, since they were not welcomed by parents. The urge for action was clearly felt and acted upon by the professionals, the municipality and beyond.

Discussion and conclusion

With hesitation, we accepted this challenging project and made it as participatory as we could. We had three reasons. First, leaving out citizens’ voices would lead to what is called ‘epistemic injustice’ (Fricker Citation2007; Groot and Abma Citation2018). Epistemic injustice arises when people are seen as less credible than policy-makers and professionals, leading to single or one-sided views of reality (Abma et al. Citation2017). Second, it would lead to a situation in which (again) top-down policies and interventions were developed that do not fit the daily reality and needs of people living in precarious circumstances. Third, it would be a missed opportunity to demonstrate the importance of listening to people who seldom have a voice in defining what is at stake and what actions should be taken. The question is: 1) how far did we meet (some of) the ethical principles of PAR as set out by the ICPHR, and with what consequences? And, 2) is it wise to start a PAR approach under such constraints in the future?

We started the project with a strong motivation for democratic participation, equality and inclusion, respect, and collective action to identify needs, to stretch the boundaries of science (if necessary) and to co-create knowledge for action. To a certain extent knowledge was generated through active learning in the daily context (testing apps, going on excursions), and policy-makers increasingly learned about people’s daily reality and needs. Establishing a respectful relationship with citizens was central to most of our actions, not ‘collecting data’, but fitting in with local activities and contexts, and the experiences people wanted to share. Different forms of knowledge were put on the table and valued: the knowledge of adult citizens, children, volunteers, educators, policy-makers and researchers; experiential, theoretical, practical, intuitive, and emotional ways of knowing were all valued, exchanged in dialogue sessions and brought together in a final report and agenda for action. The research has vividly highlighted a sense of urgency, leading to ‘ripples’ (Burns Citation2007; Trickett and Beehler Citation2017) in individual, community and policy systems, as shown in . Ripples that we expect to keep spreading thanks to the greater understanding and awareness of the problem, not only by reading a report or article, but by actually getting in touch with citizens’ real life stories.

Though we managed to put some of the core principles of PAR, as set out by the ICPHR in their ethics position paper, into practice, we could not do so for all them. Two ethical principles were not achieved, namely democratic participation and collective action. They stood at odds with the available resources (in particular time), the wish for quick wins and short-term policy impact. This jeopardized collective learning, did not do justice to the participants’ qualities, and might therefore unintentionally have fed stereotypes of people’s capabilities. The project was shaped and controlled by policy-makers and researchers, and we worked more closely with policy-makers than with citizens. In fact, citizens mainly functioned at the level of consultation while policy-makers functioned at the level of cooperation in each phase of the project. In other words, the maximization of the participation of those whose life is the subject of the research in all stages of the research process (ICPHR Citation2013) was severely limited. Second, we could not engage enough citizens in cycles of action and reflection over time. In most cases we met citizens only once, thereby limiting participatory democracy and learning. Though we sometimes felt frustrated about the time we had to invest in keeping the policy-makers of the City of Amsterdam on board, and the continuous shifting emphasis on goals, priorities and perspectives, part of the success of this project is due to their involvement. They facilitated every step in the process, ranging from opening up their networks, organizing practical pre-conditions for the research activities, translating the findings into a policy agenda, which they managed to sell to higher levels, and arranging a major conference to create awareness and shared learning. Moreover, due to their involvement they better understood for whom they work, felt the urgency for action and the importance for (future) participation.

A third critical point is that we were unable to arrange for dialogues between citizens and professionals. Instead, the researchers and volunteers functioned as a bridge between the two worlds, thereby limiting shared learning. Though from former research projects (Sarti et al. Citation2017; Bijleveld, Dedding, and Bunders-Aelen Citation2014; Abma and Broerse Citation2010) we know how valuable a dialogue is to increase mutual understanding of a multifaceted problem and the willingness to share ownership and to act together; we also know that such a dialogue should be well prepared with a representative group of people. Co-creative knowledge-generation requires facilitation so that trust can be built – particularly for a group who feels less confident and does not always have positive experiences in relation to formal institutes, as was the case in this project. But also professionals should be empowered in their role in order to avoid side-lining and the use of jargon (Elberse, Caron-Flinterman, and Broerse Citation2011). We could not pay enough attention to power issues in such a way that each voice would have been heard, dialogue encouraged and joint ownership created. As a consequence, the power of the insiders’ voice was limited; citizens could not fully show and develop their competences as owners and solvers of the problem. Moreover, the process hardly challenged negative stereotypes of people living in poverty as passive and depending on professionals for solutions, except for the many critical questions we as researchers raised in the problem-solving skills of professionals in relation to the complexity of the daily lives of people living in poverty. Working together, preferably in a shared space, could have stimulated empathy (Castro et al. Citation2018) – not only for citizens’ difficult lives, but also for people working in bureaucratic institutions, and why they act in the way they do. This understanding of the working of bureaucratic systems could reduce mistrust or reluctance to contact institutions/policy-makers for necessary applications or putting issues on the agenda.

The issues described are not completely new. Back in 1998, Robert Chambers wrote: ‘a repeated experience with PR [participatory research] has been the tension and contradiction between top down bureaucratic cultures and requirements, tending as they do to standardise, simplify and control, and demands generated at the local level, tending as they do to be diverse and complex and to require local-level discretion’ (Chambers Citation1998, 290). In this project this partly had to do with the sensitive political context, the fact that PAR was new to the policy-makers and that they had to report to different aldermen, which intensified their wish and need to control the project. Obviously, the project’s scarcest resource was time. Building trust and genuine relationships, the development and exchange of ideas, and translating these into action demands time, as many scholars have pointed out (Pain et al. Citation2015; Abma et al. Citation2019).

So, what constitutes ‘good’ participatory action research in this specific case? Choices have to be made in any project. In this project, the limited amount of time forced us to make a choice in the route towards action for social change 1) by facilitating a shared, bottom-up learning process with citizens and other relevant stakeholders, or 2) by facilitating a shared learning process with a focus on policy-makers. Given the scope and urgency of the problem of digital inequality, and the increasing exclusion of people already living in vulnerable circumstances, we believed that creating awareness and action at higher policy levels was more urgent. By working alongside policy-makers and their deadlines, we managed to create momentum in the City of Amsterdam and attract the attention of national policy-makers – not only for the specific problem, but also for working together with all stakeholders. Nevertheless, we were not satisfied, and felt a moral duty to continue what we considered an unbalanced and unfinished process. We actively advocated a follow-up project in which we would have the time necessary for good participation with citizens, and this was granted. It shows that what constitutes ‘good’ PAR is not only situational, as many have argued before, but can also be debated. Moreover, it demanded ongoing ethical work (Banks and Brydon-Miller Citation2019).

Hopefully, the growing recognition of the value of participation and the conditions it requires will help in developing more inclusive practices. It demands that we dare to share our lessons, whether positive or negative. We would encourage researchers to take up the challenge, the willingness to push boundaries, to be creative and to take risks. We hope to have shown that putting at least some of the core ethical principles of PAR into practice in less than flourishing circumstances did create ripples of change: citizens who seldom get a voice at a policy level shared their preferences, needs and knowledge, and the urge for action was clearly felt and acted upon, by professionals, the municipality and beyond.

Acknowledgments

The success of the project could not have been accomplished without the support of our commissioners of the City of Amsterdam. We would like to thank Maureen van Eijk, Maartje van de Beek and Sander Havermans for their courage in initiating this project, their firmness, and commitment. The authors also thank Rolinka Kattouw and Jantine van Wijlick, who were involved in the data collection. Last, but not least, we would like to thank all the citizens, volunteers and professionals involved for their collaboration in this project and for their valuable knowledge and insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The City of Amsterdam provides laptops to children in secondary education and MBO (vocational education) whose parents are on low incomes. Once in four years, parents with children between 12 and 18 years old can also receive a laptop. The idea was to expand the laptop arrangement to children between the ages of 10 and 18 years, and to offer a choice between a laptop and a tablet.

References

- Abma, T.A., S. Banks, T. Cook, S. Dias, W. Madsen, J. Springett, and M.T. Wright. 2019. Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-Being. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Abma, T.A., and J.E.W. Broerse. 2010. “Patient Participation as Dialogue: Setting Research Agendas.” Health Expectations 13 (2): 160–173. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10.1111). doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00549.x.

- Abma, T.A., T. Cook, M. Rämgård, E. Kleba, J. Harris, and N. Wallerstein. 2017. “Social Impact of Participatory Health Research: Collaborative Non-Linear Processes of Knowledge Mobilization.” Educational Action Research 25 (4): 489–505. doi:10.1080/09650792.2017.1329092.

- Anderson, G.L. 2017. “Can Participatory Action Research (PAR) Democratize Research, Knowledge, and Schooling? Experiences from the Global South and North.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 30 (5): 427–431. Routledge. doi:10.1080/09518398.2017.1303216.

- Banks, S., A. Armstrong, K. Carter, H. Graham, P. Hayward, A. Henry, T. Holland, et al. 2013. “Everyday Ethics in Community-Based Participatory Research.” Contemporary Social Science 8 (3): 263–277. doi:10.1080/21582041.2013.769618.

- Banks, S., and M. Brydon-Miller, eds. 2019. Ethics in Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-Being: Cases and Commentaries. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Bijleveld, G.G., C.W.M. Dedding, and J.F.G. Bunders-Aelen. 2014. “Seeing Eye to Eye or Not? Young People’s and Child Protection Workers’ Perspectives on Children’s Participation within the Dutch Child Protection and Welfare Services.” Children and Youth Services Review 47: 253–259. doi:10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2014.09.018.

- Burns, D. 2007. Systematic Action Research: A Stratergy for Whole System Change. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. doi:10.1007/s11115-009-0105-8.

- Castro, E.M., S. Malfait, T. Van Regenmortel, A. Van Hecke, W. Sermeus, and K. Vanhaecht. 2018. “Co-Design for Implementing Patient Participation in Hospital Services: A Discussion Paper.” Patient Education and Counseling 101 (7): 1302–1305. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.019.

- Chalmers, I., M.B. Bracken, B. Djulbegovic, S. Garattini, J. Grant, M. Gülmezoglu, D.W. Howells, J.P.A. Ioannidis, and S. Oliver. 2014. “How to Increase Value and Reduce Waste When Research Priorities are Set.” The Lancet 383 (9912): 156–165. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62229-1.

- Chambers, R. 1998. “Beyond ‘Whose Reality Counts?’ New Methods We Now Need?” Studies in Cultures, Organizations and Societies 4 (2): 279–301. Harwood Academic Publishers. doi:10.1080/10245289808523516.

- Cook, T. 2012. “Where Participatory Approaches Meet Pragmatism in Funded (Health) Research: The Challenge of Finding Meaningful Spaces.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 13: Art–18. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung.

- Cook, T., J. Boote, N. Buckley, S. Vougioukalou, and M. Wright. 2017. “Accessing Participatory Research Impact and Legacy: Developing the Evidence Base for Participatory Approaches in Health Research.” Educational Action Research 25 (4): 473–488. Routledge. doi:10.1080/09650792.2017.1326964.

- Cooke, B., and U. Kothari, eds. 2004. Participation: The New Tyranny? 3rd ed. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- Cornwall, A. A., and R. Jewkes. 1995. “What Is Participatory Research?” Social Science in Medicine 41 (12): 1667–1676. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-S.

- Dedding, C., N.S. Goedhart, and R. Kattouw. 2017. Digitale Ongelijkheid - Een Participatieve Verkenning in Amsterdam. Amsterdam: Gemeente Amsterdam.

- Dedding, C., and M. Slager. 2013. De Rafels Van Participatie in De Gezondheidszorg: Van Participerende Patient Naar Participerende Omgeving. Amsterdam: Boom uitgevers.

- Elberse, J.E., J.F. Caron-Flinterman, and J.E.W. Broerse. 2011. “Patient-Expert Partnerships in Research: How to Stimulate Inclusion of Patient Perspectives.” Health Expectations 14 (3): 225–239. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10.1111). doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00647.x.

- Freire, P. 1982. “Creating Alternative Research Methods: Learning to Do It by Doing It.” In Creating Knowledge: A Monopoly? Participatory Research in Development, edited by B. Hall, A. Gillette, and R. Tandon, 29–37. Toronto: Participatory Research Network.

- Fricker, M. 2007. Epistemic Injustice : Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Goedhart, N.S., J.E.W. Broerse, R. Kattouw, and C. Dedding. 2019. “‘Just Having a Computer Doesn’t Make Sense’ : The Digital Divide from the Perspective of Mothers with a Low Socio-Economic Position.” New Media & Society 1–19. doi:10.1177/1461444819846059.

- Grimshaw, J.M., M.P. Eccles, J.N. Lavis, S.J. Hill, and J.E. Squires. 2012. “Knowledge Translation of Research Findings.” Implementation Science 7 (1): 50. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-7-50.

- Groot, B.C., and T.A. Abma. 2018. “Participatory Health Research with Older People in the Netherlands: Navigating Power Imbalances Towards Mutually Transforming Power.” Participatory Health Research 165–178. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92177-8_11.

- Guo, F.Y., S. Shamdasani, and B. Randa. 2011. “Creating Effective Personas for Product Design: Insights from a Case Study.” In Internationalization, Design, HCII, 2011, LNCS 6775 P.L.P. Rau, edited by, 37–46. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-21660-2.

- Halffman, W., and H. Radder. 2015. “The Academic Manifesto: From an Occupied to a Public University.” Minerva 53 (2): 165–187. doi:10.1007/s11024-015-9270-9.

- International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR). 2013. “Position Paper 1: What Is Participatory Health Research?” Berlin.

- Ioannidis, J.P.A., S. Greenland, M.A. Hlatky, M.J. Khoury, M.R. Macleod, D. Moher, K.F. Schulz, and R. Tibshirani. 2014. “Increasing Value and Reducing Waste in Research Design, Conduct, and Analysis.” Lancet (London, England) 383 (9912): 166–175. NIH Public Access. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62227-8.

- Jagosh, J., A.C. Macualay, P. Pluye, J. Salsberg, P.L. Bush, J. Henderson, E. Sirett, et al. 2012. “Uncovering the Benefits of Participatory Research: Implications of a Realist Review for Health Research and Practice.” The Milbank Quarterly 90 (2): 311–346. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x.

- Kember, D., T. Ha, B. Lam, A. Lee, S. Ng, L. Yan, and J.C.K. Yum. 1997. “The Diverse Role of the Critical Friend in Supporting Educational Action Research Projects.” Educational Action Research 5 (3): 463–481. doi:10.1080/09650799700200036.

- Khanlou, N., and E. Peter. 2005. “Participatory Action Research: Considerations for Ethical Review.” Social Science & Medicine 60 (10): 2333–2340. Pergamon. doi:10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2004.10.004.

- Lennette, C., S.J. Banks, K. Coddington, T. Cook, S.T. Kong, C. Nunn, and N. Stavropoulou. 2019. “Brushed under the Carpet: Examining the Complexities of Participatory Research (PR).” Research in Action 3 (2): 161–179. doi:10.18546/RFA.03.2.04.

- Pain, R., K. Askins, S. Banks, T. Cook, G. Crawford, L. Crookes, S. Darby, et al. 2015. Mapping Alternative Impact: Alternative Approaches to Impact from Co-Produced Research Centre for Social Justice and Community Action. Durham, UK: Durham University.

- Penfield, T., M.J. Baker, R. Scoble, and M.C. Wykes. 2014. “Assessment, Evaluations, and Definitions of Research Impact: A Review.” Research Evaluation 23 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1093/reseval/rvt021.

- Piggot-Irvine, E., W. Rowe, and L. Ferkins. 2015. “Conceptualizing Indicator Domains for Evaluating Action Research.” Educational Action Research 23 (4): 545–566. Routledge. doi:10.1080/09650792.2015.1042984.

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury. 2001. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. London: Sage.

- Sarti, A., I. Schalkers, J.F.G. Bunders, and C. Dedding. 2017, April. “Around the Table with Policymakers: Giving Voice to Children in Contexts of Poverty and Deprivation.” Action Research 147675031769541. doi:10.1177/1476750317695412.

- Sarti, A., I. Schalkers, and C. Dedding. 2015. “‘I Am Not Poor. Poor Children Live in Africa’: Social Identity and Children’s Perspectives on Growing up in Contexts of Poverty and Deprivation in the Netherlands.” Children & Society 29 (6): 535–545. doi:10.1111/chso.12093.

- Springett, J. 2017. “Impact in Participatory Health Research: What Can We Learn from Research on Participatory Evaluation?” Educational Action Research 25 (4): 560–574. Routledge. doi:10.1080/09650792.2017.1342554.

- Stirling, A. 2008. “‘Opening Up’ and ‘Closing Down.’.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 33 (2): 262–294. doi:10.1177/0162243907311265.

- Ter Haar, W.M.A. 2014. “Communiceren En Improviseren: Omgaan Met Dynamiek En Complexiteit Bij De Ontwikkeling En Implementatie Van Een Gezondheidsinterventie.” http://dare.uva.nl

- Trickett, E.J., and S. Beehler. 2017. “Participatory Action Research and Impact: An Ecological Ripples Perspective.” Educational Action Research 25 (4): 525–540. Routledge. doi:10.1080/09650792.2017.1299025.

- Van Dijk, J.A.G.M. 2005. The Deepening Divide : Inequality in the Information Society. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- ZonMw. 2006. Handboek Patiëntenparticipatie in Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek. Edited by C. Smit, M. de Wit, C. Vossen, R. Klop, H. van der Waa, and M. Vogels. Enschede, the Netherlands: PrintPartners Ipskamp.