ABSTRACT

This paper reflects on the tensions and possibilities offered by a newly developed Action Research (AR) module in a Higher Education (HE) institution. The module, that has now run its first presentation, was offered to final year, undergraduate Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) students who are already working in the early years sector. Its aims were two-fold: first, to support students in developing the research and academic skills needed to obtain degree results; second, to become an emancipatory and political tool that can help practitioners critically examine the conditions that shape their practice. Drawing on the principles of critical, collaborative AR, students were supported in developing Communities of Practice (CoP) and in gradually moving from peripheral participation to assuming more central, expert positions. AR was also used by the tutor in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the module. Results from the latter suggest that the first, academic aims were met successfully. However, the second, emancipatory agenda faced challenges as the students seemed to assume a different, learners’ agenda. This paper makes topical the apparent tensions between the roles of practitioner, student and researcher and considers whether a reconciliation between the three is possible.

Introduction

This paper evaluates the effectiveness of a newly developed Action Research (AR) module in a Higher Education (HE) institution. This was offered to final year, undergraduate Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) students who are already working in the early years sector. It is a level 6, compulsory module and aims to support students in conducting research and writing up a dissertation.

Most of our students have substantial work experience and confidence in their ability to meet the demands of their work environment. In other words, they have significant tacit (Polanyi Citation1962) and practical (Schӧn Citation1983) knowledge about their practice. However, they often feel less certain about their ability to meet the academic challenges of university study.

The new AR module, which has now completed its first year, was developed in order to address this lack of parity between the students’ self-efficacy as practitioners and as learners. Using the students’ practical knowledge and skills as the starting point, the AR module aimed at supporting them to explore their relationship with academic ‘knowledge’. The module’s aims were two-fold: firstly, to support students in developing the research skills and the confidence to investigate and improve aspects of their practice; secondly, to encourage them to reposition themselves as agents of change, as powerful, knowledgeable practitioners that can participate in debates and have a ‘voice’ about their profession (Kemmis Citation2009; McNiff Citation2017; Schӧn Citation1983; Papadopoulou Citation2019).

Therefore, and in addition to meeting the module’s academic outcomes (for accreditation purposes), this AR programme had an empowering agenda; it aimed at supporting students in developing strong professional identities, or else at forming a Community of Practice (CoP) (Wenger Citation1998) that collaboratively debated, explored and negotiated meanings. Using the tools of ongoing reflection and collaborative enquiry as a starting point, students were invited to uncover and examine their (often tacit) knowledge (Polanyi Citation1962) and personal values that inform their practice. They were encouraged to share, discuss and debate their knowledge with peers in an attempt to develop their professional identities and sense of belonging to a professional community of similar minded others (Wenger Citation2004). Individual and group reflections were then complemented with the development of academic and research skills. Academic and research skills were introduced and explored in relation to and as a means of studying the field of practice (Papadopoulou Citation2011). Methods and theoretical concepts were introduced as ‘tools’ that can help achieve a purpose, answer questions and bring changes in the field of practice.

It has been our ambition to use this course as an emancipatory tool for our student-practitioners; to give them the methodological and academic skills needed to resolve ‘problems’ that are relevant and important to them and to bring their concerns to the public domain. This is, admittedly, a complex, far reaching and challenging undertaking. There is, perhaps, an unavoidable conflict between trying to empower students whilst at the same time assessing their performance for accreditation purposes. Indeed, being a student who tries to achieve externally defined standards may often be at odds with the empowering identities that our course aimed at fostering in our student-practitioners. The terrain of HE with its ‘audit culture’ (Groundwater-Smith and Mockler Citation2016), the tyranny of learning objectives (Hil Citation2015) and individualistic ethos (McAlister Citation2016) have often threatened our empowering agenda.

This AR module partially met its aims; it has succeeded in supporting students to meet the learning outcomes for this programme of study. Indeed, the students developed research skills, conducted AR about an area of their practice and wrote dissertations that met all academic level 6 criteria. However, our political agenda proved to be more ambiguous. Despite our ongoing efforts to create a space for collaborative reflection, a space for a CoP, students seemed, at times, to have different priorities; they seemed more concerned with completing their work in the given time frame, meeting deadlines and achieving a high grade. There was a community there, during our sessions, but this was a students’ community, or else a group of learners. The ties and cohesion of the learning group were loose, with individuals’ agendas often taking the lead over the group’s shared aims.

This paper highlights the apparent tensions between the roles of ‘practitioner’ and ‘student’. It first considers the role and purpose of AR as an emancipatory and political tool that can help practitioners critically examine the conditions that shape their practice. It then discusses the ways practitioners can engage in discussions and contribute to shaping their practice through the development of CoP. Following from this, this paper considers the extent to which the broader structural and political context of HE can really afford us the opportunities to create communities of informed, confident and agentic practitioners.

Drawing on the students’ and the tutor’s reflections upon the experience of this module, the paper addresses the tensions arising from the two communities: the CoP that the tutor was trying to establish and the Community of Students (CoS) that the students appeared more familiar with and willing to inhabit. The last section of this paper discusses this apparent conflict between student, researcher and professional identities and whether a reconciliation between the three is ever possible.

Action Research as a political tool

It was the ambition of our AR module to bring politics into the classroom (Moss Citation2007). Given its political and theoretical foundations (Gibbs et al. Citation2017), we employed AR as a tool to introduce critical pedagogy in Higher Education. It was used, not only as a means for (academic and research) skill development, but also as an emancipatory tool that could help reposition practitioners as agents of change (Papadopoulou Citation2019). This AR model, otherwise called collaborative critical action research, is the one Kemmis and McTaggart refer to in their definition:

Action research is a form of collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own social or educational practices, as well as their understandings of these practices and the situations within which these practices are carried out (Kemmis and McTaggart, Citation1998, p. 1).

This type of AR aims at bringing about change; change in the ways practitioners understand and carry out their practice, but also change in the conditions that shape practices (Kemmis Citation2006). The practitioners’ remit of deliberation is not restricted to their immediate work environment. Rather, it reaches out to and addresses the field of practice. It considers the complex socio political and historical factors that have shaped practice in addressing and debating the broader, complex issues that have influenced practice. It involves taking action with the purpose of achieving a change in the world, not just in the classroom. It involves speaking for oneself, as a practitioner, and offering explanations for the action one has taken (McNiff Citation2017); but also seeing oneself as part of a network of others; as taking action in a social context that involves, and possibly has an impact on, others.

This type of AR views practitioners as researchers, as theorists and as activists. It gives them an intellectual and a moral platform to define their practice. It sees them as valuable informants and as agents; as the ‘yeast’ (Kemmis Citation2010) that, through individual and collaborative reflection, helps their practice evolve in the face of changing needs and circumstances. Alas, this type of practitioner enquiry seems to be in short supply.

AR can take different forms and teleoaffective structures. Kemmis (Citation2009) refers to three types: Technical AR aims at improving practitioners’ practice based on predetermined, externally defined and measurable outcomes. There is a given, uncontested definition of ‘good practice’, that the practitioner aspires to achieving and AR becomes the instrument for achieving this end. The role of practitioners is to understand the requirements and to follow a predetermined route to meeting them. This typology is frequently employed in HE institutions, where the standards and outcomes are already set and conforming to these leads to accreditation. Research of this kind focuses on ‘teaching’ practitioners to implement policy and improve teaching techniques (Kinsler Citation2010), and may result in the ‘domestication’ of practitioners (Kemmis Citation2006).

The second type, practical AR, is more open ended according to Kemmis (Citation2009). The aim is to improve a particular area of practice, but the ends are not predefined and given. The ends, as well as the means, are in question. The role of the practitioner is to gain an understanding of the practice and act more wisely. Practitioners assume an evaluative stance in considering the short and long term consequences of certain decisions and in this way they set the criteria for assessing their practice. Practical AR affords opportunities for the practitioner to make some decisions about his/her practice and recognises his/her authority in making changes and setting the standards of practice.

The third type, emancipatory or critical AR, is the most transitive of all. It involves a critical stance to knowledge generation, policy making, issues of power and control and the positioning of the researcher/practitioner. It problematizes power structures and locates practice within the context of the wider socio-political frame (Kemmis and McTaggart Citation1998). This type of research, employed in our AR module, requires collective activity. It is undertaken by practitioners that see themselves as ‘we’, as a community with a distinct identity that has agency and a contribution to make. This type of research opens up a space for discussion, debate and negotiation; a communicative space where practitioners can engage in group reflections and collectively explore issues related to their everyday practices (Kemmis Citation2009; Kinsler Citation2010).

The three types of AR presented here differ in the degree of agency and control that practitioners assume. In technical AR they have very limited agency to make decisions or define the criteria of ‘good’ practice. The course of research and action are close ended, predetermined and non-negotiable. The role of the researcher/practitioner is to follow the predetermined route and meet these externally defined requirements. The second type, practical research, affords practitioners more opportunities to make decisions. It is more evaluative and open ended, but still focuses on the individuals’ remit of reflection and action. This perhaps makes it limited in scope. The last, critical, type, is the most transitive of all.

Its influence lies in empowering practitioners to make their voices, individually but, perhaps even more importantly, collectively heard; and taken seriously in making decisions about their practice. This type of emancipatory research appears to be in short supply. The voices of practitioners are, more often than not, marginalised. Indeed, as Whitehead and McNiff (Whitehead and Jean Citation2006) and McNiff (Citation2017) state, early years practitioners tend to not participate in theory generation and policy formation. They are often seen as the technicians, whose role is to translate others’ theories and knowledge into practice.

The preference for technical and practical AR is also found in teacher education courses (Chesney and Marcangelo Citation2010; Getz Citation2009; Gravett Citation2004; Greenbank Citation2007). The aim of such programmes is to improve individuals’ teaching practice, but not to question this practice and the conditions shaping it.

However, Kemmis (Citation2010) argues that practitioners are not just ‘operatives but also stewards – custodians of the practice for their times and generation’. It is the duty of each professional body (and in our case HE programme that offers professional accreditation) to contribute to the evolution of its profession; to support its members to develop the skills, knowledge, confidence and critical awareness that will enable them to help their practice evolve. Enable them to flexibly respond to the changing demands of their profession through the process of ongoing dialogue and deliberation.

Our AR module aimed at supporting students to engage in individual and group reflection; to ‘step back’ from the familiar field of practice in order to problematize it; reflect on and in their practice (Schӧn Citation1983) and consider the broader issues influencing their role as practitioners. Our intention was to create ‘communicative spaces’ (Kemmis Citation2006) that would enable students to form their Community of Practice.

Situated learning in a community of practice

Situated learning theory sees learning as a social process and as embedded in some form of practice. It emerges from interactions between individuals as they engage with and participate in social practices (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). A CoP is not just a group of people; it is a community with mutual engagement, a joint enterprise and shared repertoire (Wenger Citation1998).

Mutual engagement refers to the group’s distinctive patterns of interaction. These are the group’s established norms of relationships and expectations and become the ties that bind the group members together. The group members gradually develop shared understandings of themselves, the community and its purpose. In other words, they develop a common understanding of what their CoP is about; a joint enterprise that is constantly negotiated by its members. Finally, as the community establishes its norms, ways of relating, doing and acting, it develops a shared repertoire, a set of common resources, such as language, tools, artefacts, concepts, methods and standards (Wenger Citation2010). It is through these three characteristics that the group establishes its criteria of what it is to be a participant, a competent member, or an outsider.

Engagement and full participation in the practices of the community happen gradually. Newcomers start at the periphery of activity as they are gradually introduced to the norms and practices of the community. Gradually, as they gain experience, they move towards the centre through growing involvement. This initial, peripheral positioning of new members is legitimate, it is a developmental process community members experience as they progress from being a novice to becoming an expert. The notion of legitimate peripheral participation (Wenger Citation1998) describes the dynamic process of initiation the CoP uses to engage newcomers and support them in progressively becoming fully involved.

Involvement in CoP offers individuals a sense of identity. Engagement in shared practice and negotiation of meaning involves a sense of becoming that the participants experience; a sense of self belonging in a certain community with a given purpose (Wenger Citation2016). This process of identity formation is bi-directional: as individuals enter the community they already have a sense of self as having certain skills, competences, intentions and ways of contributing to the community. At the same time, engagement with a community of similar-minded others contributes to one’s sense of belonging and becoming; the latter inextricably linked to the individual’s sense of being as a person.

The degree of similar-mindedness between a community’s members has, however, been questioned. Hodkinson (Citation2004) challenges the idealised, cosy, narrative of homogeneity between the participants of CoP. Power relationships, competing, individualistic agendas and competitiveness between community members (Cousin and Deepwell Citation2005; Pemberton, Mavin, and Stalker Citation2007) can threaten group cohesion and a shared identity. Roberts (Citation2006) argues that it is the broader context within which a CoP functions that shapes its workings, relationships between its members, the transfer of knowledge and success in meeting its agenda. Our AR module was designed along the principles of situated learning theory. It involved creating a community of practice that would enable students to share their experiences and understandings of their practice and to negotiate meanings; to address and reflect on the complexities, the norms and standards of their practice; to develop a strong practitioner identity and sense of belonging to a group of similar minded others (Papadopoulou Citation2019). It was anticipated that, as the course progressed, the students’ participation would increase and move from the periphery to the centre; that they would gradually gain the confidence, control and agency to take the lead and make decisions about their study, their research and issues surrounding their practice. However, the context within which our study developed, the terrain of HE, posed its own challenges, as discussed next.

The terrain of HE: a community of practice or a community of students?

The type and degree of participants’ involvement in communities of research and practice depends on the opportunities that the wider context offers. Individuals’ praxis is shaped by the cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political conditions that shape their practice. These ‘practice architectures’ (Kemmis Citation2009) prefigure the practice as they enable or restrict certain ways of doing, of saying, of relating to others, of thinking.

The terrain of HE, at least in the West, with its audit culture and emphasis on externally defined measurable outcomes, (Groundwater-Smith and Mockler Citation2016) inhibits participation, collaboration and self-determination. This neoliberal ethos of the HE permeates all aspects of academic life and imposes its own set of cultural, socio-political, economical and relational arrangements; it creates its own norms, expectations and priorities. Its emphasis on assessment and its ‘tyranny of grades’, its individualistic and antagonistic ethos threaten collaborative engagement, the sharing of ideas and collective work.

Universities are highly complex systems and consist of several and diverse CoP. The academic landscape is turbulent, continuously changing in response to internal and external political and economic drivers (Arthur Citation2016). The academic environment may thus be less sympathetic to the ethos of CoP (Nagy and Burch Citation2009).

In their study about the experience of students on a Teacher Training Education programme, The Literacy Study Group (Citation2010) reflect on the impact of the broader structural and political forces impacting on students’ willingness to engage in the CoP embedded in their programme of study. Students’ motivation to be members of such a CoP depends on two factors: a. whether they see the university as a CoP and b. whether they see themselves as belonging to this community. Students’ perceptions are influenced by the broader context of economic, political and managerialist forces shaping their academic experience (The Literacy Study Group Citation2010). CoP are only possible ‘in conditions that advance democratic and communicatively orientated practices’ (p. 10). This democratic ethos underpinning CoP seems to be at odds with the broader marketisation and instrumentalist discourses shaping academia.

The practice architecture in academic institutions, thus, restricts the development of a CoP but perhaps affords opportunities for the development of a different type of community, a Community of Students (CoS).

Henri and Pudelko (Citation2003) argue that different types of community emerge in different contexts, depending on the level of group cohesion, the common aims that the community sets for itself and the intentionality of its members. The learners’ community (here we call it Community of Students – CoS) emerges in academic environments. Its members are students, and it is created by a tutor to facilitate learning and meet learning outcomes. The duration and purpose of this community are determined by the life of and engagement with the programme of study individuals are undertaking. So, it is preoccupation with academic study that gives this community its sole purpose and identity rather than with learning as a lifelong process. This is the reason we prefer to call this a Community of Students rather than a Community of Learners.

The members of this community can show varying degrees of contribution and participation in the learning process. However, the quality standards, modular and disciplinary demands are pre-set, fixed and not open to negotiation. The end product of learning is fixed, individually assessed, unquestionable and measurable in some way. The instructor’s role is to support each individual student to reach this end successfully and timely.

This creates a different relationship dynamic. The tutor is seen as possessing knowledge and skills and as having the role and responsibility to transmit these to the learners. In this landscape of educational praxis, the tutor is the only ‘expert’, occupying the centre of the CoP. The learners are at the periphery and, with scaffolding and individual work, may start gaining knowledge and understanding of the module and its requirements. However, students can never really occupy the central positions in this endeavour; they never become the ‘experts’ because they lack the power to collaboratively negotiate and set the norms of this (educational) practice.

The aim of our AR module was to create opportunities and spaces for dialogue and negotiation of meaning as the means by which the participants/students would move from the periphery towards more central positions in this educational praxis. However, at times we all experienced tensions that seemed to reflect the different agendas individuals had. Perhaps there were two, often competing, communities there: a CoP that I was trying to support and a CoS that the students seemed more at ease with and willing to inhabit.

Methodology

Context and rationale

Our department has developed several, predominantly public sector, courses in the Early Childhood field. The ECEC programme we will be focusing on here admits students that are already in employment and seek academic accreditation. Most of them work four days a week and attend university one day only. They may thus have several challenges and competing priorities to meet in addition to their university study, a point we will return to later.

Despite the apparent heterogeneity of this group in terms of socio economic background, age, level of qualifications, practitioner and life experiences, there are some common characteristics that different student cohorts seem to have historically shared. Firstly, there has often been a disparity between the students’ voices as practitioners and as learners. When invited to discuss issues related to their practice, students seemed familiar with the ‘shop floor’ of their practice. They possessed substantial tacit (Polanyi Citation1962) and practical knowledge (Schӧn Citation1983) and their voices often had authority when sharing meanings and experiences about their practice and the children in their care. However, when the discussion shifted to the academic sphere, these same voices sometimes would lose their authority and become more insecure and uncertain.

Secondly, students have often expressed their self-perceived lack of agency and the ability to make decisions about their practice. This seemed to have an impact on their sense of practitioner identities. Most saw themselves as ‘technicians’, who were told what to do, when and how to do it, rather than as practitioners with power and control over their profession.

These two considerations led to the development of the AR module. It was designed as a learning but also as a political tool. As a learning tool it aimed at supporting students to develop academic and research skills as they reflected, evaluated, researched and wrote about their practice. The learning outcomes were assessed through the written dissertation of the AR students conducted in their field of practice. As a political tool, it aimed at supporting students in assuming a critical stance towards the conditions that shape their practice; reflect on themselves, their role, power and agency as practitioners; and develop a sense of professional, collaborative identities. A sense of belonging to a group that had the voice, authority, agency and legitimacy to influence their practice (Papadopoulou Citation2019).

The AR module

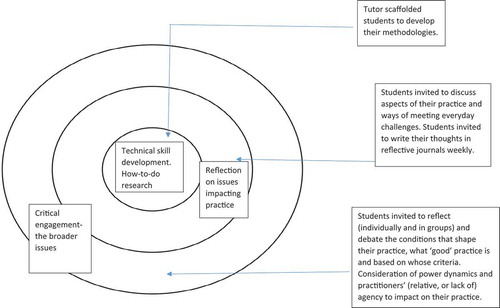

Although the overarching module aim was to facilitate students’ critical engagement, elements of both technical and practical Action Research (Kemmis Citation2006) were incorporated in the module design. The latter were seen as the first stages of a developmental process leading to the former. Development of technical (research and academic) skills and knowledge about how-to-do research was the first, descriptive stage. This was seen as a prerequisite for the development of a more reflective stance, a deeper understanding and appreciation of aspects of practice that required improvement (the second, practical stage). These two modes of student engagement were considered as integral parts of a more critical stance about their practice and of themselves as practitioners. The three types of engagement have been depicted as concentric cycles in this course design (see ).

As shows, each of the three layers required a different kind of tutor input and student engagement. Each taught session addressed all three layers of AR engagement; starting with the technical dimension, then considering the practical considerations and finally addressing the ‘big’, complex picture of practice. Whilst addressing the technical aspect, students received tutor input on research methodologies followed by individual and group activities. The next layer of student engagement, the practical dimension, was addressed through individual and group activities. Students were now invited to reflect upon, narrate and debate several issues impacting upon their everyday practice and ways of addressing these through enquiry. Students were also supported in engaging with the broader conditions that shape their practice and themselves as practitioners (the critical dimension).

There were 10 taught sessions, each including elements of technical, practical and critical engagement. The intention was to create a practice architecture that allowed space for open dialogue and debate. With this in mind, the students were invited to share their views and make decisions about our ways of working together. Despite the fact that the learning outcomes and assessment were already set and beyond our control, the group engaged in negotiating and making decisions about all other aspects of the module organisation, structure and ways of working together.

The students were encouraged to share their experiences and thoughts, to evaluate areas within their practice that worked, or did not work, and to consider the factors and conditions that had an impact on what they did as practitioners. They were often invited to reflect on ‘what the issues are’, in a chosen area, or ‘what it is that we want to improve and why’, but also on ‘who we are and what matters to us as practitioners’. Such questions aimed at supporting the students in assuming a critical stance and appreciation of the space architectures of their working lives.

The course also aimed at strengthening their group identities and giving them a safe space to ‘join their voices’ and thus get an empowered sense of self as part of an agentic CoP. Learners were scaffolded to gradually move from the periphery of participation to occupying more central positions in our topography of practice. In order to achieve a dynamic movement of the group members, I positioned myself as a facilitator but not an expert. My role and input was changeable, depending on the focus of the discussion. When reflecting on an area of practice, the students were the experts and I was the novice, who did not know and asked questions. This dynamic changed when the focus shifted on research and academic skills and tutor expertise was needed. Finally, the students knew that all of us in that context were action researchers, investigating an area of our practice in order to improve it. Alongside their AR, I was also investigating the effectiveness of this module. When discussing my AR, the students were the experts, the informants that I was consulting in order to improve my practice.

Sample

The student cohort that studied the AR module consisted of 20 women from different age groups and socio-economic backgrounds. They had variable experiences of the field of early years practice and a spread of academic qualifications and competences.

Ethics

The students were told at the beginning of the course that I also intended to carry out AR in order to evaluate and further develop this module. They were fully informed of the aims of the study and all of them agreed that I could reflect on and write about my experience of the module. In addition to this, I invited volunteers to discuss the impact the AR module has had on their student and practitioner identities. All students gave me permission to carry out research upon the experience of teaching this module and ten students actively engaged with the research process by contributing their insights.

The students’ anonymity, confidentiality and data protection have been maintained in accordance with BERA (British Educational Research Association (BERA) Citation2018).

Methods

Three methods were used for this study: questionnaires, interviews and the tutor’s reflections. Questionnaires were administered to students towards the end of the AR module. The questions invited them to reflect on and evaluate the module; consider what worked well, what did not work so well, how they positioned themselves and whether the module had contributed (and if so how) to their sense of selves as students and as practitioners.

Some of the students suggested that we should have a discussion instead. These students were offered semi structured interviews where they were invited to evaluate the module and their experience. In these discussions they reflected on aspects of the course and certain incidents that seemed to stand out. These discussions became a rich source of data allowing me to reflect on issues from a number of perspectives (the students’ and my own).

Finally, I kept a journal for the duration of the course. This included critical incidents and my reflections on those.

Findings

Students’ perceptions

When invited to reflect on their experience of the AR module, the students referred to the impact it has had in the following areas. There is often a sense of overlap between some of these themes as student responses sometimes referred to more than one theme. The following patterns of meaning emerged:

Knowledge and skills

All the students thought that the module had given them significant research skills, such as the ability to systematically observe behaviours, identify areas for improvement, plan and carry out research to achieve these improvements and reflect on the process.

I feel confident that I do this (elements of AR) already in everyday practice. I will often bring an observation for discussion to a staff meeting for the team to reflect and talk about.

Some also referred to the knowledge they acquired about their research topic and aspects of practice, such as theories about children’s learning and the importance of play.

I now look at children’s learning very differently, and really value child-initiated play as the context for learning in early childhood.

Understanding of their practice

Responses in this category referred to a different appreciation of issues, a different stance they had developed as the result of their study. They spoke of their developed ability to understand issues in their practice, to be more critical and evaluative, to adopt a more systematic approach when ‘defining’ a problem, or when trying to find solutions to a problem in their practice.

This module has had a huge impact on my practice by informing my knowledge of effective pedagogy

Another comment referred to a better understanding of the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) that herself and colleagues had reached and how this had impacted on their everyday practice.

Doing Action Research has changed my practice as I now implement an emergent curriculum, therefore changing how myself and my team view the role of the EYFS in our practice

They also spoke of their newly emergent disposition to collect evidence before making decisions in their everyday practice.

I now feel that I am able to identify issues that impact upon my practice, and engage in the action research cycle myself to gain knowledge and understanding surrounding practice. (Student B)

Sense of self

Some students also reflected on the ways the AR module had contributed to a more positive sense of self. They spoke about the confidence they had gained as the result of choosing their topic of interest and carrying out their own research.

My confidence as a practitioner has grown massively as I feel I have a good knowledge of my chosen subject.

The fact that this module was designed around their practice, their interests and concerns, gave them intrinsic motivation and made them feel they had some agency and control over making their own decisions during the research process.

I am now much clearer of my role as a practitioner and how I can promote effective learning. I keep discussing my ideas with colleagues and parents.

One of the students spoke about the sense of empowerments she felt she would have by collecting research evidence to support her practice:

I feel that this will really help me at times where I feel my beliefs as a professional are threatened, e.g. by parents or Ofsted inspectors as I can now justify my thinking and have research that supports me.

One of the students, who was leaving the early years sector to join a charity for children, felt prepared to meet the new challenges. This confidence was based on the skills she developed when doing AR:

I feel very prepared professionally to take this new challenge and role and I know a lot of that is down to my personal journey through the action research process.

Impact on the field of practice

I started this project with very different opinions about my work colleagues and feel that (as the result of doing this project) I have a very different perspective now … I have become a lot more reflective in my practice which has also helped me become a lot happier in my job!

The students thought that their research had had an impact on their relationship with colleagues and parents in their field of practice. One student remarked that group reflections (used as a data collection tool in her study) had now become the norm at her setting. Herself and her colleagues would all sit together and reflect on issues at the end of the day.

Reflections are part of everyday life at work. At the end of each day, when all children are gone we all sit down and reflect on our day. It helps us to think and plan the next day.

One other practitioner said that her study had helped her convince her colleagues and parents about the benefits of risky play (her chosen AR topic)

I always knew it that risky play is good for children. Doing this research has helped me show colleagues and peers the evidence, what I always knew.

The following two responses refer to the impact of AR on the collaborative engagement of staff in resolving practical issues.

We have now started talking about things that don’t work. We bring issues to the table, share our views and discuss solutions.

My team and I are now continuously developing tools that can help us be responsive to child-initiated learning to further improve our practice.

The relational aspect

Although not specifically asked, students often referred to the importance of others and of relationships in the ways they experienced the research process and study of the module. Relationships with colleagues, parents and children (in their work environment) were seen as central. Responses frequently mentioned the importance of offering quality support to the children in their care, their motive to meet the children’s needs, their accountability and sense of responsibility towards parents, colleagues and, predominantly the children.

Relationships with fellow students were also mentioned frequently. Students spoke about the positive experience of working in and receiving support from small groups of peers, the importance of exchanging views and having ‘critical’ friends, the positive relationship they had with the tutor and the support they received from others in the duration of their study. However, there were also some less positive comments about others.

In their work environment, students often felt restrained, frustrated and not understood by colleagues and management. They were often under pressure to fulfil duties they had not been consulted about; their colleagues were not always appreciative of their thoughts and initiatives and some of the parents were seen as ‘too demanding’.

In the academic context, students seemed to have positive relationships with one another, but they also acknowledged that they did not feel open and comfortable sharing their views in class. Rather, they preferred to be in small friendship groups.

We are a supportive bunch, like if anyone needs advice or any help, we offer it. But I don’t like sharing my ideas in class. I’d rather speak to X and Y(names of two other students) about my work

Some of the students admitted that the atmosphere was too antagonistic and competitive. One of the students thought that she put so much effort into her studies and in achieving a good grade, so she did not want others to get ‘ready’ answers and achieve the same outcome without trying as hard as she did.

I have worked very hard for this degree and I want a first. I know that some others in this class haven’t done as much as I have. So why should I give them ready answers?

One other student felt that some of her colleagues were too secretive about their work and this discouraged her from sharing her ideas. Other students spoke about the lack of confidence they had in sharing their experiences as they felt that they might be judged as less competent, or that their views were of less interest to others.

I don’t know what the others are thinking. I don’t want to be judged. I’m better off speaking to my small group of peers.

Indeed, most of the students admitted that their relationships with colleagues were often too competitive and this restricted their opportunities for open dialogue and debate.

Pressures

All of the students referred to a number of pressures they experienced during the course. They frequently complained about their deadlines, the pressures experienced at work and at university and the competing demands placed upon them. Some students were committed to achieving high grades and channelled all efforts to understanding what they had to do in order to gain these grades.

For other students, regular attendance and time to read and reflect on the course themes were difficult to achieve for a number of reasons. Consequently, as the course progressed, they felt under stress and less confident to actively engage with the course.

I feel a little lost as the classes have finished but I’m unsure on how and what to include and if I am doing it right. We should have spent more time doing our questionnaires and ethics in class.

These pressures seemed to relate to academic study in general rather than the specific course

All modules, not just this, is causing lots of worry and stress because of the timings. (end of academic year- nursery children transitioning to school (= reports, parent meetings, lots of paperwork, school teacher appointments) plus finding time to write this module.

Suggestions

The students felt that the course had offered them significant knowledge and skills that were transferable to their practice. They were particularly positive about the first sessions, where they were introduced to AR and invited to reflect on their field of practice. They also appreciated the tutor input as it enabled them to gain an understanding of methodologies and answer their questions. However, they were less positive about the significance and impact of collaborative reflections. Indeed, most of the students felt that the course should gradually become more tailored to individual students’ needs. They thought that group reflections on issues of practice should be replaced with tutor input and individual support. The latter would help them make better use of the limited time and would give them more specific instructions about how to investigate their chosen topic.

I feel this module was very good at the beginning but as each individual started to develop and gather a knowledge, it needed to become more personalised.

Another student suggested that group activities and discussions should be replaced by individual support as the module progressed:

… once we decided out topics, some of the input was not relevant to each of us individually …

The students appreciated work in small groups, but felt that whole class discussions of topics were not always relevant to all students. I would suggest perhaps minimal whole class input and more focus on discussing with individuals.

The tutor’s perspective – a summary

Throughout the duration of the AR module I kept a reflective log of my thoughts. The following extracts are chosen as they depict the dynamics of our interaction as they emerged and progressed during the course. I present these in chronological order to identify any developmental trends in student engagement, in line with Wenger’s (Citation1998) notion of Legitimate Peripheral Participation.

The first session was successful. The students seemed interested in AR. They understood its aims and expectations. They seemed inspired by its emancipatory agenda. When asked to reflect on their practice all the practitioners expressed a strong professional ethos. They felt motivated to offer quality services to children and their families. They spoke about their ‘duty of care’ towards children. But, they also felt constrained by conditions, structures and other individuals in their settings. This made me reflect on how the module could address the politics of disempowerment. The students seemed aware of critical issues in their field of practice. I felt optimistic about the outcomes of this module.

In the following two sessions, the students seemed engaged. They asked questions and participated in small group activities. Some students seemed more confident and had clearer ideas about their topics of interest and how to investigate them. Others seemed uncertain and reluctant to choose an area for investigation. They kept asking what it is they have to do. Only a few of the students had done the readings and preparatory work for the sessions.

Mid-point: the atmosphere felt different. Students seemed quiet and reserved. They answered questions, when asked, but did not seem too willing to engage in discussions and take initiatives. Why did they feel apprehensive? Did they need more scaffolding and encouragement in developing the confidence to share their reflections? Wasn’t this a ‘safe’ space to share and negotiate meanings? I felt anxious and responded by taking the lead. This session was tutor heavy. I felt that the students needed more input – they kept asking what they had to do and seemed to expect a ‘right’ answer. In response to this, I defaulted to giving them answers.

Last sessions: The students felt that they needed clear instructions about what was expected of them. They felt under pressure as the course was coming to an end and the submission deadline was approaching. I defaulted to the traditional role of offering input and giving suggestions. Reflections and other group activities were limited in number and duration and took place in small groups. The last sessions offered more time for individual support. All students made use of this and seemed more open to discuss their ideas when speaking to me on their own. I was aware that this was not the co-constructive model of teaching I had in mind when designing the module. In some ways it was the opposite as it drew on a more traditional pedagogical model. However, I could also feel the pressures of time and of students that needed ‘answers’.

Discussion

The aims of this AR module were two-fold: first, to facilitate the development of the knowledge and skills needed to conduct AR that meets academic standards; second, to support students in developing a strong sense of collaborative, practitioner identity and the confidence to reflect on, and make their voices heard as a CoP (Wenger Citation1998). The first, academic aim, was met successfully. Indeed, our students/practitioners chose topics that were of importance to them, reflected on their significance for their practice and defined the research ‘problem’ that their study would address. They were supported in designing and carrying out research that would resolve the research issue they had identified and in engaging with the complexities surrounding their area of study.

The students, thus, successfully assumed a researcher’s perspective as they carried out AR, albeit this was at a technical or, at best, at a practical level (Kemmis Citation2009). The research ‘problems’ that students identified mostly assumed a given, predetermined and unquestionable definition of ‘good practice’. Consequently, they saw their practitioner roles as understanding and meeting the standards of this ‘good practice’ but not always questioning it. Some of our more academically competent students referred to critical issues. They reflected on some of the complexities and pressures experienced in practice and on the socio-political influences impacting on their practice and on themselves as practitioners. This type of engagement resembles Kemmis’ (Kemmis Citation2009) second type of practical AR in that it is evaluative; but lacks the collective, self-reflective stance that Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) refer to in their definition of critical, collaborative AR.

Students engaged with the module, but this was mostly as individuals, not as a collective. Indeed, their collaborative, self-reflective, practitioner ‘voice’ was often lacking. They seemed more willing to collectively explore the conditions and issues affecting their practice at the beginning of the course. However, this collaborative voice lost its momentum and was gradually replaced by individuals’ voices. This collaborative space seemed to give way to a more solitary space where each individual’s immediate concerns and agendas took precedence over the common, shared interests, concerns of the collective.

The practical, time restraints and competing demands in students’ lives, took precedence over the new collaborative, agentic ethos the module was promoting. This is also noted In Jacob’s study:

when time pressure rose, the empowerment goal started to collide with academic and practical aims, and the dialogue within the project team became obstructed leading to a return to the traditional routine of applied research and the accompanying power relationships, with implications for the learning in and about the project. (Jacobs Citation2010, 367)

The group, thus, lacked the mutual engagement, joint enterprise and shared repertoire of a CoP (Wenger Citation1998). Its members shared individually defined and oriented interests, concerns and agendas. These emerged from their role as students and the emphasis they placed upon learning, achieving and gaining accreditation. They were predominantly a Community of Students (CoS) that happened to share similar experiences as practitioners.

The relationships, roles, expectations and dynamics of the CoS differed to these of the CoP that I was trying to foster. The dynamics of the community we became part of were more fixed than what I had anticipated. At the beginning the students occupied peripheral positions but appeared more flexible in moving to the centre as they discussed issues in their practice. The tutor’s position was at the centre when the focus of the discussion was on academic and research skills but not when the discussion was about the students’ field of practice. However, this dynamic soon lost its momentum as our positions started becoming less flexible. Despite the knowledge and familiarity with research that the students gradually developed, they assumed a progressively more ‘passive’ stance. They asked for answers and often seemed to resist engaging with the ambiguity and complexity of issues. They positioned the tutor as the expert, at the centre of this configuration, and themselves as unknowing, as inexperienced, at time helpless, that needed specific guidance and fixed answers.

Despite my initial reluctance to betray the emancipatory agenda of the module, I soon assumed the expert position that was expected of me. Feeling the pressure of the students’ expectations and the fixed time scale we had to complete the module, I defaulted to a more authoritative role and assumed a less interactive, less dynamic, less constructivist teaching model. The political, emancipatory agenda of this module was, therefore, not met.

Perhaps this is not surprising, if one considers the academic context within which this AR module was developed. The pressure to meet the learning outcomes within a given time frame, to achieve high grades and thus gain a degree that is ‘good value for money’ may have constrained our opportunities for debate, negotiation of meanings and activism. As Henri and Pudelko (Citation2003) claim, CoP cannot happen in academic environments. At best, they can be used as a learning tool, as a way of showing students how theory can translate into practice.

This resonates with our experience of this module. Our practitioners did engage in discussions about their practice and they did show awareness of issues that have an impact on their practice. In other words, they did have a sense of practitioner identity and belonging in a CoP. But this ‘lived elsewhere’, it seemed to inhabit a different space, not the academic environment. For the duration of this module, the participants mostly assumed a different identity, a students’ identity, perhaps in response to what was expected of them. The students’ identity, and the researchers’ identity that they developed when embarking on AR, sometimes seemed to be in conflict with the emancipated practitioner identity that the module aimed at fostering.

This begs the question, are these identities really irreconcilable? Perhaps they are not. There may be significant overlap between the three and each may inform or be influenced by the others. People can be members of different communities, each with clearly defined boundaries. Brokering is the process of transferring some elements from one community to another (Wenger Citation1998). In this sense, the communities of learners, of practitioners and of researchers, that are at the core of our AR module, should not be seen as mutually exclusive but as interconnected, as open and mutually influential systems; as the rings of a chain.

In order to resolve the tensions between the students’ and practitioners’ identities and agendas, we need to reconceptualise the different communities we are all members of and the ways these relate to and influence one another. Perhaps community membership and engagement, as a dynamic process, cannot be viewed as separate from the process of positioning (Harré and van Langenhove Citation1999). Positioning of the self and of others (as individuals as communities) is continuous and always at play in the development of individual and of group identity. Self and other positioning can only happen in relation to others and in response to the demands and expectations of different contexts. As such, this process of positioning of oneself (and of others) in several communities needs to become topical.

Conclusion

Our student practitioners developed knowledge and research skills and conducted AR that was successful in meeting the module outcomes. The academic outcomes were thus fulfilled. They engaged in a Community of Students with its own typology: they assumed certain roles (perhaps not as active and autonomous as I would have liked), had common expectations (of what this module was about and how it can contribute to their self-defined goals). They developed a common language and repertoire of behaviours that reflected their experience of studying, understanding and meeting learning outcomes. Notwithstanding the lack of collaborative engagement, the group shared common understandings of the conditions of this (academic) context and how to be in that environment. They all positioned themselves as students and were members of a student identity with shared, albeit individualistic, goals.

This does not suggest, however, that our students cannot be collaborative, critical and political about their practice. Such attitudes have emergent qualities; they emanate from real life situations and in order to deal with real concerns that affect the whole community of similar minded others. They ‘inhabit’ a different space, the work environment.

Our AR agenda continues to be emancipatory, although the latter will only be demonstrated whilst in their field of practice. In the duration of this module we can offer the skills, knowledge and confidence they will need to position themselves as critical, reflective and collaborative agents whilst addressing real life problems.

Future steps: In the new course presentation and, as we enter the second cycle of the spiral of AR, our self-positioning as individuals, learners, researchers and members of a community will become the starting point and central theme of the module. All participants (students and tutor) will engage in ongoing reflections of who we are as learners, as experts, as practitioners and as researchers; as individuals and as a collective; who we are at present and who we are aspiring to becoming. Through ongoing, collaborative and individual reflections and brokering we will continuously reflect on the ways our different identities develop and mutually influence each other, but may also be in conflict at times.

Perhaps critical, collaborative reflection on ourselves and our roles will create new spaces for debate, dialogue, negotiations; a reconfigured practice architecture that is enabling, agentic and emancipatory for all its members.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Arthur, L. 2016. “Communities of Practice in Higher Education: Professional Learning in an Academic Career.” International Journal for Academic Development 21 (3): 230–241. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2015.1127813.

- British Educational Research Association (BERA). 2018. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. 4th Available at Accessed: 30 April 2019. British Educational Research Association. https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Chesney, S., and C. Marcangelo. 2010. “There Was a Lot of Learning Going On: Using a Digital Medium to Support Learning in a Professional Course for New HE Lecturers.” Computers and Education 54: 701–708. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.09.027.

- Cousin, G., and F. Deepwell. 2005. “Designs for Network Learning: A Communities of Practice Perspective.” Studies in Higher Education 30: 57–66. doi:10.1080/0307507052000307795.

- Getz, C. 2009. “Teaching Leadership as Exploring Sacred Space.” Educational Action Research 17: 447–461. doi:10.1080/09650790903093318.

- Gibbs, P., P. Cartney, K. Wilkinson, J. Parkinson, S. Cunningham, C. James-Reynolds, T. Zoubir, et al. 2017. “Literature Review on the Use of Action Research in Higher Education.” Educational Action Research 25 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1080/09650792.2015.1124046.

- Gravett, S. 2004. “Action Research and Transformative Learning in Teaching Development.” Educational Action Research 12: 259–272. doi:10.1080/09650790400200248.

- Greenbank, P. 2007. “Utilising Collaborative Forms of Educational Action Research: Some Reflections.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 31: 97–108. doi:10.1080/03098770701267531.

- Groundwater-Smith, S., and N. Mockler. 2016. “From Data Source to Co-researchers? Tracing the Shift from ‘Student Voice’ to Student-Teacher Partnerships in Educational Action Research.” Educational Action Research 24 (2): 159–176. doi:10.1080/09650792.2015.1053507.

- Harré, R., & van Langenhove, L. (Eds.). 1999. Positioning theory: Moral contexts of intentional actions. Oxford: Blackwell

- Henri, F., and B. Pudelko. 2003. “Understanding and Analysing Activity and Learning in Virtual Communities.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 19: 474–487. doi:10.1046/j.0266-4909.2003.00051.x.

- Hil, R. 2015. Selling Students Short. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin.

- Hodkinson, P. 2004. “Research as a Form of Work: Expertise, Community and Methodological Objectivity.” British Educational Research Journal 30: 9–26. doi:10.1080/01411920310001629947.

- Jacobs, G. 2010. “Conflicting Demands and the Power of Defensive Routines in Participatory Action Research.” Action Research 8: 367–386. doi:10.1177/1476750310366041.

- Kemmis, S. 2006. “Participatory Action Research and the Public Sphere.” Educational Action Research 14 (4): 459–476. doi:10.1080/09650790600975593.

- Kemmis, S. 2009. “Action Research as a Practice-Based Practice.” Educational Action Research 17 (3): 463–474. doi:10.1080/09650790903093284.

- Kemmis, S. 2010. “What Is to Be Done? The Place of Action Research.” Educational Action Research 18 (4): 417–427. doi:10.1080/09650793.2010.524745.

- Kemmis, S., and R. McTaggart. 1998. The Action Research Planner. Geelong: Deakin University Press. Geelong, Victoria: Deakin University Press.

- Kinsler, K. 2010. “The Utility of Educational Action Research for Emancipatory Change.” Action Research 8 (2): 171–189. doi:10.1177/1476750309351357.

- Lave, J., and É. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McAlister, M. 2016. “Emerging Communities of Practice.” Collective Essays on Learning and Teaching, Volume IX.

- McNiff, J. 2017. Action Research. All You Need to Know. London: Sage.

- Moss, P. 2007. “Bringing Politics into the Nursery: Early Childhood Education as a Democratic Practice.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 15 (1): 5–20. doi:10.1080/13502930601046620.

- Nagy, J., and T. Burch. 2009. “Communities of Practice in Academe (Cop‐ia): Understanding Academic Work Practices to Enable Knowledge Building Capacities in Corporate Universities.” Oxford Review of Education 35: 227–247. doi:10.1080/03054980902792888.

- Papadopoulou, M. 2011. “The Authority of Personal Knowledge in the Development of Critical Thinking: A Pedagogy of Self Reflection.” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 3 (3): 1–21. doi:10.11120/elss.2011.03030012.

- Papadopoulou, M. 2019. “Supporting the Development of Early Years Students’ Professional Identities through an Action Research Programme.” Educational Action Research. doi:10.1080/09650792.2019.1652196.

- Pemberton, J., S. Mavin, and B. Stalker. 2007. “Scratching beneath the Surface of Communities of (Mal) Practice.” The Learning Organization 14: 62–73. doi:10.1108/09696470710718357.

- Polanyi, M. 1962. Personal Knowledge. Towards a Post Critical Philosophy. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Roberts, J. 2006. “£limits to Communities of Practice.” Journal of Management Studies 43: 623–639. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00618.x.

- Schӧn, D.A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner. How Professionals Think in Action. London: Temple Smith.

- The Literacy Study Group. 2010. “The Allegiance and Experience of Student Literacy Teachers in the Post‐compulsory Education Context: Competing Communities of Practice.” Journal of Education for Teaching 36 (1): 5–17. doi:10.1080/02607470903461927.

- Wenger, É. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity (Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive and Computational Perspectives). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, É. 2004. “Knowledge Management as a Doughnut”. Ivey Business Journal. https://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/knowledge-management-as-a-doughnut/ last accessed 11/07/19

- Wenger, E. 2010. “Conceptual Tools for CoPs as Social Learning Systems: Boundaries, Identity, Trajectories and Participation”. In Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, edited by Chris Blackmore, 125–144. London: Springer.

- Wenger, E. 2016. “Communities of Practice as a Social Theory of Learning: a Conversation with Etienne Wenger.” British Journal of Educational Studies 64: 139–160. doi:10.1080/00071005.2015.1133799.

- Whitehead, J., and M. Jean. 2006. Action Research. Living Theory. London: Sage Publications.