ABSTRACT

This research study focuses on school leadership groups taking part in an action research project (AR project) within schools in a Norwegian municipality. The study aims to show and discuss how action research (AR) adopted in school change can help build collective leadership capacity in school leadership groups. Combined with the theory of expansive learning, the theories of critical participatory action research and practice architectures frame the study. The study identified two essential actions for building leadership capacity in school leadership groups: performing an empirical and historical analysis of the problem space worked on and conducting collective reflections regarding their experiences in the development work process. Furthermore, the study shows how external leadership supervisors can contribute as critical friends in ways that may be significant for capacity building in school leadership groups. The study concludes with two implications related to collective capacity building for school leadership groups and one methodological implication for performing action research.

Introduction

School leaders play a significant role in developing schools. Change processes depend on the school leaders’ capacity to lead collective learning processes in schools through collaborative and theoretically informed reflexive activities (Kovačević and Hallinger Citation2019; Fullan Citation2018; Stoll et al. Citation2006). Leadership groups offer a promising approach to building capacity by developing their collective leadership capacity through action research (AR), as is reported in this article.

Leadership is required to manage school development work and sustain change to improve student learning (Aas and Paulsen Citation2019; Bush Citation2018; Fullan Citation2014; Hargreaves and Shirley Citation2012; Mulford and Silins Citation2003). Development work cannot be accomplished without active support from leaders at all levels (Harris and Jones Citation2019; Leithwood and Louis Citation2012; Leithwood, Sun, and Pollock Citation2017; Vennebo Citation2015). This insight is supported by research and reflected in many countries’ educational policies (OECD Citation2013). Educational changes progress depending on school leaders’ and teachers’ individual and collective capacities to promote students’ learning (Hargreaves and O’Connor Citation2018). These capacities include motivation, skills, positive learning, organisational conditions, organisational culture and support infrastructure (Stoll et al. Citation2006).

Developing professional learning communities (PLCs) is one way of building capacities for sustainable school improvements and changes (DuFour and Marzano Citation2011; Fullan Citation2018; Stoll and Louis Citation2007). As of yet, no universal definition of a PLC has been established, but a broad international consensus has developed around the following definition: ‘a group of people sharing and critically interrogating their practice in an ongoing, reflective, collaborative, inclusive, learning-oriented, growth-promoting way’ (Stoll et al. Citation2006, 223). To understand the link between leadership and change, it is useful to consider the five characteristics that PLCs share: (1) shared values, (2) collective responsibility, (3) reflective professional enquiry, (4) collaboration and (5) group and individual learning (Stoll and Louis Citation2007). In other words, PLCs provide opportunities for leaders and teachers to discuss and negotiate the meaning of concepts and experiences and to understand new theories better, thereby building consensus concerning the values and goals of new collective practices (Timperley et al. Citation2007).

When the work of transforming schools includes all or most schools in a district, such work requires a system change. Transformation requires changes in what the participants say, what they do and how they relate (Kemmis Citation2009). A system change involves schools and districts learning from each other by strengthening the focus of the middle leadership regarding system goals and local needs (Fullan Citation2015). To close the gap between the different levels in the education system, establishing and developing school leadership groups as PLCs may be useful. In this article, the gap relates to the relationship between the district level (municipality) and the school level. By building learning centred around leaders’ experiences and practices, theory and practice can be linked together through collaborative reflexive activities (Aas Citation2017a; Dempster, Lovett, and Fluckiger Citation2011; Huber Citation2011; Robertson Citation2013). In other words, school leaders being active and involved in development processes in their own schools is crucial to their personal and their schools’ learning as well as for remaking practices (Aas, Vennebo, and Halvorsen Citation2019; Vennebo Citation2016). This corresponds to practical action research (Kemmis Citation2009), building on collaborative and self-reflective principles through which practitioners remake their practices for themselves. Action research (AR) may be called a ‘practice-changing practice’ and, as such, a mode of learning for school leadership development (Kemmis Citation2009). It can be a systematic, critical and self-critical process that animates and urges changes in practice, understandings and the conditions of practices through individual and collective self-reflective transformation (Kemmis et al. Citation2014).

Because negotiation and internal conflicts are part of the developmental and learning processes in schools (Aas Citation2017b; Roth and Lee Citation2006; Stoll and Louis Citation2007), in-depth examinations of school leaders’ and teachers’ behaviours and practices are essential for understanding change. Historical cultural activity theory and the idea of expansive learning (Engeström Citation2001) offer, in combination with AR theories, a theoretical framework that fits this study’s purpose: to show and discuss how AR adopted in the context of school change can help to build collective leadership capacity in school leadership groups.

The present study was guided by the following research question: How can school leadership groups build their collective leadership capacity through AR? The research context comprised AR undertaken in a Norwegian municipality with fifteen participating schools and their leadership groups in collaboration with three researchers/leadership supervisors from two universities. Through an AR project the municipality wanted to support the schools’ change processes of integrating and using iPads in schools, especially to help the school leadership groups to develop their collective leadership capacity necessary to progress the school change processes. The following sections of the article include a presentation of the theoretical framework, the research context and the methodology and an analysis of the findings in light of the theoretical framework. Finally, the last section offers concluding remarks on the research.

Theories of critical participatory AR and practice architectures

AR is described as a promising approach for transforming practice (Kemmis Citation2009; Lewin and Cartwright Citation1951; Reason and Bradbury Citation2006; Somekh and Zeichner Citation2009). Based on critical theory, particularly Habermas (Citation1987) idea of critical social science, critical participatory action researchers study practices from ‘within a practice tradition’ (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Researching a practice from ‘within’ means standing alongside practitioners to make or remake the practice by doing it differently, for example, supporting school leadership groups in their process of integrating and using iPads in schools. Critical participatory AR aims to change not only practitioners’ practices but also their understandings of their practices and the situations in which they perform them (including the practice architectures that shape them). None of these three change efforts precede the others; they all constantly interplay with one another (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2019).

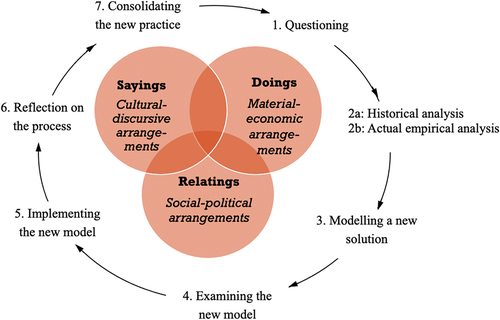

The theory of practice architectures offers insight into interactions between the individual and the social perspectives of practices. Social interaction is seen as a system in which the combination of what is said and done and the relationships among those involved create a dynamic interaction (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2014). The framework of practice architectures is inspired by Schatzki’s practice theory and philosophy (Schatzki Citation2006), first presented by Kemmis and Grootenboer (Citation2008) and still undergoing development (Kemmis, Wilkinson, and Edwards-Groves Citation2017). The theory is used in the literature regarding theoretical, reflective and analytical frameworks, for example, concerning school leadership (Seiser Citation2019; Skoglund Citation2020). Changing practices requires changing the conditions that support the practices and the practice architectures that enable and constrain them. New practices, with new sayings, doings and relatings, indicate that we must also have new practice architectures to support them: new cultural-discursive arrangements, new material-economic arrangements and new social-political arrangements. Only when these new practice architectures are in place can new practices survive (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2014).

Practice architectures appear in three intersubjective dimensions: semantic, social and physical. In the semantic dimension, cultural-discursive arrangements appear through the language and speech (Kemmis et al. Citation2014) surrounding the specific practice, such as during discourse about using iPads in schools. In the social dimension, social-political arrangements reveal how people relate to each other and to artefacts inside and outside the practice, such as through the relationships between leaders and teachers, between teachers and students or between teachers and parents. In the physical dimension, material-economic arrangements become visible in the actions and work that take place, for example, in the discourse about technological equipment.

Through critical participatory AR, participants aim to analyse, explore and, if possible, transform particular sayings, doings and ways of relating. Sayings refer to ideas, narratives and perspectives that inform their practices and how these are situated in local discursive arrangements or new ways of thinking and saying (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). In relation to current AR, the following may be asked: Do different people have different views about whether iPad use in schools is a good idea? Do they have different views about whether the schools’ current practices are productive or unproductive? Doings refer to activities and patterns of work that animate the participants’ practices and the ways these are made possible by the particular local material-economic arrangements or new ways of doing things. Concerning current AR, two questions might be asked: Do different people have differing views about whether the schools’ current practices are sustainable or unsustainable? What sort of technical equipment is necessary to implement iPad use in the entire school? Finally, ways of relating are enacted in their practices and the ways these are made possible by the particular local social-political arrangements or new ways of relating to others. Relating refers to how people encounter one another as social beings in a particular place (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2019). Regarding the AR, the following may be questioned: Do the new practices foster solidarity and a sense of inclusion and belonging among the teachers, or do they create conflict among people? Do the school leader groups and teachers have different answers to these questions?

Critical participatory AR and the theory of practice architectures are built on the idea that practices are central to knowledge generation and change. This involves a shift from an epistemological perspective to an ontological perspective. An epistemological perspective puts knowledge at the centre of things, while an ontological perspective emphasizes practice. The former focuses on knowing and the latter on being and becoming (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2019, 190). An action researcher works more like a historian to write the local history of the practices and the traditions that they are part of and to document how they change in light of the efforts that participants make to improve their practices. While the theory of practice architectures can tell us how the transformations of saying, doings and relatings are part of contextual arrangements, the framework of expansive learning can help us to see how change activities are part of longitudinal cultural-historical arrangements.

Theory of expansive learning

Engeström’s (Citation1987) theory of expansive learning explains learning as collective processes among communities of learners that relies on its own metaphor: expansion (Engeström and Sannino Citation2010). Expansion means that learners, in the learning process, learn something that is not yet there. The learners construct a new object for their collective activity and attempt to implement this new object in practice, which, in the present study, refers to integrating and using iPads in schools. This implies a process of constructing and reconstructing an object of change and looking into both short-term action and long-term activity (Engestrom Citation2000).

Questioning is a necessary starting point in Engeström’s (Citation2001) sequences of action in an expansive learning circle. If the questions and motivations for change come from the participants within an organisation, a leader more easily obtains commitment than if these questions and motivations originate from external sources (e.g. the district). Both historical and current empirical analyses should be conducted before a new solution (e.g. a new practice) is framed. The next sequence of action is to analyse the new model before implementing the corresponding practice. After implementation, the participants must reflect on the current practice before the new practice can be consolidated. New questions must be asked concerning current methods to illustrate the constantly changing practices. Expansive learning can potentially produce new forms of work activity; in doing so, however, the learning process may cease or break down.

An understanding of the role of contradictions is crucial to appreciate what happens within a collective activity. Contradictions are defined as historically accumulated structural tensions within and among activity systems (Engeström Citation2001. They serve as both driving forces and obstacles in a learning process (Citation2001; Foot Citation2001). An expansive learning circle illustrates how development is a non-linear but contradictory process of expected and unexpected outcomes. A core idea of expansive methodology is that revealing and addressing tensions is necessary to attain sustainable practices and consolidate new practices. In the case of incorporating iPads into the schools as in this research, tensions were represented as conflicting voices between expectations from the district and teacher levels. Darwin (Citation2011), who explores the methodological potential of AR in activity theory, argued that Engeström’s (Citation2001) expansive methodology and the reflective circle of AR provide a foundation for alignment because they share the same transformative motive. On the one hand, AR methods offer expansive learning a complementary interventionist methodology; specifically, AR methods provide more democratic and participatory modes of research engagement and social learning. On the other hand, practice architectures can reflexively benefit from the analysis of action sequences in an expansive learning circle (Aas Citation2014). An overview of ‘sayings, doings and relatings within the expansive learning circle’ is illustrated in .

Figure 1. Sayings, doings and relatings within the expansive learning circle. Inspired by Kemmis et al. (Citation2014) and Engestróm (Citation2001)

Research context

The research was conducted during a partnership between three researchers/leadership supervisors from two universities and fifteen schools involving the district level (a municipality responsible for primary and lower secondary schools) in Norway. Based on their decisions about integrating and using one-to-one iPads in all the school classrooms, the district had put an action plan for digital competence building into action. The plan was based on the SAMR Model, which is a framework created by Puentedura (Citation2013) that categorises four different degrees of classroom technology integration. SAMR is an acronym that stands for substitution, augmentation, modification, and redefinition. Substitution and augmentation are considered enhancement steps, while modification and redefinition are termed transformation steps. As a first practical step, the district had finished a year-long learning programme for all teachers on using iPads in schools. When the district, the director and his leadership team recognized the great variety between classrooms within schools and between schools in terms of using iPads, they wanted to support the schools’ change efforts, especially to help the school leadership groups develop their collective leadership capacity necessary to progress the school change processes further. In collaboration with three researchers/leadership supervisors from the two universities, an AR project was established to fulfil the district’s desire to support the school leadership groups. The partners came to an agreement on developing knowledge through exploring new teaching methods related to iPads, on building an environment for professional learning among teachers and in the leadership groups and on encouraging systematic improvement in the change process. The AR project commenced from June 2018 to June 2019. Prior to the project, the researchers/leadership supervisors observed selected courses from the learning programme for teachers to obtain knowledge about how this particular learning programme could affect the schools’ change processes.

All researchers/leadership supervisors had specific knowledge about school leadership and the methodology of group coaching based on respect, recognition and positive feedback (Aas and Vavik Citation2015; Britton Citation2010; Brown and Grant Citation2010). A timetable was set up for four leadership group meetings per school, and each of the three researchers/leadership supervisors was responsible for leading the process in five leadership groups, with fifteen schools altogether, including three lower upper-secondary schools and twelve primary schools. The district level (the director of the municipality) had superior authority in establishing the policies of the partnership, which were discussed in regular meetings with the researchers/leadership supervisors. During the process, observations and reflections from the researchers/leadership supervisors, especially problems with leadership groups that could not participate due to the timetable, were discussed with the director and his leadership team. All other leadership group meetings were confidential and kept between the supervisor and the leadership group member according to the ethical policy of AR (Carr and Kemmis Citation1986). A group coaching methodology (Aas Citation2017a) combined with the action phases in the expansive learning circle (Engeström Citation2001) was chosen to support the schools’ change processes (see ). With inspiration from a protocol used in the Norwegian National Leadership Programme,Footnote1 a particular coaching protocol was developed (Aas and Fluckiger Citation2016; Brandmo et al. Citation2019). The five steps of the protocol are presented in .

Table 1. Protocol for the group coaching sessions.

Methodology

In this article, we draw on reflection-based data from the AR project, which ran from 2018–2020, and focus on the leadership groups’ sayings, doings and relatings that evolved through the groups’ participation in the project during 2018–2019, the conditions that support their practices and the practice architectures that enable and constrain their practices, as well as how the AR project supported capacity building in the school leadership groups. Reflection notes written ahead of the four leadership group meetings, protocols after the meetings and the researchers’/leadership supervisors’ field notes from the meetings constituted the core data. The background data, the plan for digital competence building and the agreement regarding the AR project comprised PowerPoint presentations, meeting protocols and the researchers’/leadership supervisors’ field notes from the three seminars for all the leadership groups in the district, director and advisers at the district governance level and the three researchers/leadership supervisors. The number of participants in the leadership groups ranged from two to six, with a total of 60 persons involved. The seminars included 68 participants. An overview of the data collection is shown in .

Table 2. Overview of the core data collection.

The data collected at meetings allowed us to capture the opinions of leadership group members, while the practice architectures that enabled and constrained their practices as cultural-discursive arrangements, material-economic arrangements and social-political arrangements were documented in the field notes. To capture the longitudinal aspects of the study, the group meetings were repeated four times between September 2018 and June 2019. The researchers/leadership supervisors acted as critical friends, assisting throughout the questioning and providing reflection and other viewpoints (Henriksen and Aas Citation2020; Swaffield Citation2004). A critical friend can be seen as a shoulder to lean on and is like the role of a leadership coach, who can contribute to principals’ learning through contributing critical questions and reflections that can lead to new leadership practices (Fluckiger, Lovett, and Dempster Citation2014).

Based on the data, we examined how each of the school leadership groups explored the change process through their sayings, doings and relatings. The analysis was conducted in three steps (Richards Citation2014). We started by revealing all statements proposed in the reflection notes, the meeting protocols and the field notes for every leadership group. Next, we organized the statements into seven analytical categories, referring to each of the sequences of action in the expansive learning circle (questioning, historical and empirical analyses, modelling the new solution, analysing the new model, implementing the new model, reflecting on the process and consolidating the new practice) across all fifteen groups. These analytical categories represent the longitudinal change process. Furthermore, we performed a close-up analysis of the statements within each of the seven main analytical categories, as listed above. This provided an overview of which sayings, doings and relatings were typical in the different action sequences of the change process. Additionally, the field notes helped us to see how the practice architectures affected possibilities and barriers in the change process, which could help us in explaining why some leadership groups succeeded in building leadership capacity while others did not. In , we show how, in the analysis, we combined the practice architectures with the analytical categories from the actions in the expansive learning circle to identify the main findings.

Table 3. Analytical categories to reveal transformations in sayings, doings and relatings within the expansive learning circle.

The Norwegian ethical guidelines for social-science-based research, provided by the National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and Humanities (NESH), and the guidelines given by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) were adhered to throughout the research. All the participants consented to participate. They were assured confidentiality and informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time without explaining their reasoning. Member checking (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985) was used to ensure the quality of the research project. This means that all the leadership groups and the director of the municipality and his leadership team have read the text for both accuracy and the ethical dimension.

Findings and analysis

The aim of this study was to provide insight into how an AR can build leadership capacity in leadership groups. The analytical matrix in elaborates on and discusses the findings in five sections: first, discussions during the start-up of the change process (sequences 1 and 2 in the expansive learning circle); second, discussions about the modelling of the new teaching and learning practices (sequences 3 and 4 in the expansive learning circle); third, discussions about the implementation of new practices (sequence 5 in the expansive learning circle); fourth, discussions about reflections on the process (sequence 6 in the expansive learning circle); and five, discussions about consolidating new practices (sequence 7 in the expansive learning circle). Discussions about how barriers related to the practice architecture influence the practice of the leadership groups are included in each section.

The presentation includes quotes from the participants to illustrate the main findings. The quotes were translated from Norwegian to English. We started the translation process when we worked on the close analysis of the statements, identifying typical sayings, doings and ways of relating in the different action sequences of the change process. To confirm that we captured the original meaning in the words during translation, the research team discussed the translations in light of the national and local context.

The start-up sequences

The first group meeting was mainly used to describe the school context to understand how each school’s organisation and culture (social-political arrangements) could influence the change process. In this investigation, the leadership group was a central theme in uncovering how the work in the leadership group was organized: how often they met, what they talked about and how they organized the work. An obligation in the AR project was that the schools had to define and pilot one or more new practices. Because the middle leaders were to lead and follow up with the work in their departments or teams, it seemed important for school leadership groups to develop a collective understanding of what to change and how to do it. A discussion on these questions was initiated by the researchers/leadership supervisors in the group meetings, and the principal then continued the discussion in their own school.

The first critical action was revealed in the second sequence of expansive learning: performing empirical and historical analyses. Ten of the schools completed an analysis of actual school practices regarding iPads, while five of the schools did not come up with an analysis. The main reasons for not conducting an analysis included a long tradition of private teacher practices, illness or other problems in the leadership group and too many projects initiated from the district level. As one of the principals said in the first group meeting:

Right now, I am alone in the leadership group because one middle leadership position is vacant and one middle leader has been sick for a long time. My focus is running the school, and so I cannot get deeply involved in all the development projects the district level asks us to do. (Principal at a small primary school)

For the ten schools that performed the empirical analysis, the most typical finding was that differences existed between teachers’ competence and their willingness to change. One of the principals described the situation in the following way: ‘There is a big variation in the skills of the staff around the use of iPads and apps; many may experience that the iPad project is not relevant to them and their students’ (Principal at a primary school).

Another barrier was identified in the analysis of the reflection notes and the meeting protocols. The reflection notes served as preparation for the meetings and should have been sent to the researchers/leadership supervisors one week in advance of each group meeting. After the meetings, the schools were instructed to write a summary of what had been discussed in the conversations and what actions they should accomplish before the next group meeting. Meeting protocols were to be sent to the researchers/leadership supervisors. The writing process was part of training the leadership groups to formulate their sayings in terms of achieving clarity regarding what to do and why and to build a bridge to the doings. A typical pattern was that the researchers/leadership supervisors had to remind participants about the deadlines for reflection notes and the meeting protocols. Reasons provided for not meeting the deadlines were most often that the principals had very stressful everyday working lives, that unexpected leadership challenges had occurred or that it was difficult for them to meet all expectations placed on them, either by the district or by their teachers. On some occasions, the schools came to the group meetings without having submitted a reflection note in advance, or the meeting had to be postponed and conducted virtually on Skype. These conditions were either due to a principal’s illness or extraordinary conditions at the school. From the data, we can see how barriers to the cultural-discursive arrangements (weak tradition regarding writing) and the material-economic arrangements (tensions between external expectations and the conditions of their practical daily working lives) created challenges in the establishment phase and influenced the further process of change.

The modelling sequence

There was great variety in the topics that the schools wanted to work with and to develop further (see , the columns Modelling and Analysing the new model). Some schools were concerned with how they could use iPads in teaching and learning. This included the further testing of apps that they had already received training on from the courses and the desire for new apps. Several wanted to use iPads to strengthen students’ reading skills, especially for subject-specific reading. Competence development was another theme that was repeated in almost all schools as well as how to ensure that both the schools’ leadership groups and the teachers who were not keen iPad and digital technologies users could increase their competence. Many schools highlighted the need to discuss how iPads affected the role of teachers. A recurring theme questioned in many schools was how the iPad initiative was seen in light of the schools’ technical equipment and digital infrastructures as well as how the work could be included in an overall digitization strategy. The variety of themes illustrates how differently the schools started their work in terms of integrating and using iPads in teaching and learning. Across all the leadership groups, there were many questions about the future, exemplified in a reflection note from one of the principals:

We have a lot of questions: How can learning boards be used to increase exploratory and critical thinking pedagogy? How can teachers be helped to show how this happens in practice? How can a plan be made that contains more than competence development, and what is it possible to measure? (Lower secondary school principal)

Two different leadership approaches could be identified in the leadership groups in the modelling process. Ten leadership groups participated closely with the teachers during the modelling, while the other five leadership groups had a more administrative leadership style. Both material-economic arrangements (the practical conditions for the leadership group) and social-political arrangements (the culture and leadership style in the leadership group) influenced how the leadership group participated in the modelling phase. An example of how practical conditions function as a barrier in this process was expressed by one of the principals in a reflection note at the second group meeting:

We have had little time together in the leadership group since last time. One middle leader is following leadership training at the university, another is finishing his master’s and the third has had two full-day meetings at City Hall, as well as the fact that there are a lot of student cases arising due to teacher absence. (Primary school principal)

The implementation sequence

The second critical action appeared during the implementation sequence. All schools defined and carried out the implementation of new practices in a limited area related to the use of iPads in the schools’ teaching and learning. The trials included the use of iPads in the students’ learning, the teachers’ learning and in each school’s administration. Technological changes to support the integration and use of iPads were implemented in all fifteen schools, often in collaboration with the district level. Concerning pedagogical changes, one to five examples of new practices were implemented in each school, either in some classrooms or across the entire school, as exemplified by one of the principals in their third reflection note:

Office 365 and the use of iPads are now an integrated part of the teachers’ education and students’ learning. We have a collective agreement about implementing iPads in the students’ own evaluations. The purpose is to enhance the students’ reflections and dialogues regarding their own learning. (Lower secondary school principal)

Ten of the leadership groups closely followed up the implementation process, while the other five leadership groups left the follow-up to the teacher teams. At this stage in the change process, we could see how it became a challenge for the principal involved when the entire leadership group was not present during the supervisor group meetings. This was especially relevant when the piloting required the members of the leadership group to guide the work of their department or team. Only four of the leadership groups participated in all four group meetings, which was caused by barriers in the physical dimension, explained as the material-economic arrangements. In his reflection note from the third group meeting, one of the principals explained the difficulties of not participating in the meetings with his entire leadership group:

It is a challenge for me when we are not together as a leadership group in the group meetings because then I have to follow up the process back in school, and that is difficult. I cannot remember everything that is said by the supervisors, and it is impossible to replace the collective understanding that occurred in the group meeting. (Principal at a primary school)

Since the AR project’s idea was to support the schools’ change efforts and help the school leadership groups to develop the collective capacity (Stoll et al. Citation2006) necessary for taking the school change processes further, we can see how such processes depend on a place and time for a collective culture of sharing and critically investigating school practices. According to Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon (Citation2019), this means new ways of relating to others as social beings in the particular place in question.

The reflection sequence

Several schools had a tradition of sharing experiences between teachers in departments or teams and, to some extent, between teams. A central theme for discussion in all leadership groups was how sharing experiences could be connected to collaborative reflections. The members of the leadership groups were trained in asking questions that could contribute to reflection and generate new learning by combining and connecting experience-based knowledge with research-based knowledge. Schools where entire leadership groups participated in the supervised sessions benefited most from this learning. They emphasized that working with questions and reflections related to the definition and trialling of new practices contributed to increased learning for them and for the school as a whole. Several leadership groups reported that the supervision in the meetings functioned as a model for how the principal could create and drive knowledge-based experiential learning in their own leadership group and for how the middle leaders could, in the same way, facilitate knowledge-based experiential learning processes in their departments/teams.

This particular effect of the modelling process was expressed by one of the principals in their last reflection note: ‘The critical questions from the supervisor have helped us in expressing and sharing our opinions, and we see that we as leaders have to facilitate the same reflection practices in supporting the teachers’ (Principal at a primary school). Another principal described how they had developed a school structure for reflections: ‘Teachers collaborate about developing new classroom practices. After each trialling sequence, they make written reflections. Furthermore, they share their reflections in teacher teams and, finally, with the whole teacher group’ (Principal at a small primary school). As mentioned earlier, theory and practice can be linked together through collaborative reflexive activities (Aas Citation2017a; Dempster, Lovett, and Fluckiger Citation2011; Huber Citation2011; Robertson Citation2013). According to the practice architecture regarding the conditions of sayings, doings and relatings, we can see that both facilitating structures of collective reflections and the leaders’ skills in leading these processes seem to be crucial for schools’ learning and remaking practices (Aas, Vennebo, and Halvorsen Citation2019; Vennebo Citation2016).

The consolidating sequence

According to Engeström (Citation2001), consolidating practices means that the new practices have become part of the institutional school organisation, for example, as collective understandings and new routines. The variations between schools identified in the start-up phase of the change process regarding teachers’ competences and the willingness to change were also displayed at the end of the AR project. In the analysis, we could identify one to five new practices in each school that could be characterized as consolidating practices. However, some changes were only located in singular classrooms, whereas other changes were schoolwide, including collective understandings and routines for collective reflections, as expressed by one of the principals:

We have completed several changes regarding pedagogical practice during this project, but the most important change involves translating experience sharing into new learning. The leadership group has made a long-term plan of how the pedagogical process surrounding the iPad should be taken forward. (Principal at a lower secondary school)

Concerning building leadership capacity in the leadership groups, we identified two areas of leadership practices that could be characterized as consolidating. First, ten leadership groups experienced how performing empirical and historical analysis in the group helped them to build a collective understanding of what to do and why in preparation for taking the modelling sequence further to the entire teacher group. As shown above, barriers to the practice architecture (the conditions for sayings, doings and relatings) seemed to inhibit the process for the five other leadership groups. Second, the same ten leadership groups enhanced their knowledge in leading collective reflections. The impact of leading and performing collective reflections led to new learning for themselves and for the teachers, whereas in the five other schools, a more fragmented practice occurred depending on the willingness of single teachers and not the entire leadership group.

Conclusions

The study showed that schools where the principal and the leadership group themselves were actively involved in leading the AR project seemed to succeed in building collective leadership capacity for school change. New school practices emerged as a result of ‘learning by doing’ (Dewey Citation1966) in a process of the transformation of sayings, doings and relatings (Kemmis Citation2009), first in the leadership group and then in the teacher group. Leadership groups that performed the analysis of actual practices appeared to be better prepared for coming up with new solutions in the modelling phase. Furthermore, knowledge and skills in terms of leading reflections in experience-sharing sessions by asking reflective questions themselves facilitated experience sharing and resulted in something more than just telling each other about what had been done. It turned out that asking reflective questions became a critical skill in leading change processes and implementing new practices. By using the framework of expansive learning as an analytical tool (Engeström Citation2001), we identified two critical actions in building capacity in the leadership groups: first, in sequence 2, ‘doing empirical and historical analysis,’ and second, in sequence 6, ‘reflections on the process.’ The theory of practice architectures helped us to identify barriers in the conditions of sayings, doings and relatings in each action in expansive learning. As reported above, the barriers according to sequences 2 and 6 were related to cultural-discursive arrangements, material-economic arrangements, and social-political arrangements (Kemmis et al. Citation2014); they played out as a combination of practical barriers in the school organisation structures as well as expressions at the district level and the history of the school.

The role of the researchers/leadership supervisors as critical friends (Henriksen and Aas Citation2020) was greatly acknowledged by the leadership groups, particularly by the ten groups that used the critical questions from the researchers/leadership supervisors to examine and improve the collective culture in their leadership groups. Because of the duty of confidentiality, the leaders were free to share their thoughts and concerns without any consequences for their jobs. The participants expressed great satisfaction that they could speak openly, and the atmosphere was characterized by trust, leading to increased motivation to make changes at their schools (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2019). Critical participatory AR aims to change the practices of not only the practitioners but also the researchers/leadership supervisors (critical friends). As researchers/leadership supervisors, we learned from the AR project that we had to find a balance between motivating and supporting the participants in writing reflection notes and coming to the meetings. Even though we were disappointed when the leadership groups did not send the reflection notes before the meetings or suddenly cancelled a meeting, we had to focus on how we could support them in moving forward through each stage by showing them that we understand the challenges that appeared in their daily leadership practices.

We suggest two implications related to collective capacity building for school leadership groups and one methodological implication of performing AR. First, leadership groups play a critical role in constructing and implementing new practices in schools. In doing so, they need to enhance their knowledge of leading collective processes of performing an empirical and historical analysis of current practices before modelling new practices. Next, they need to improve their capacity for leading collective reflections (asking reflective questions) when new practices are implemented. Furthermore, the combination of using the framework of expansive learning and the theory of practice architectures might be useful as an analytical lens in studies of change processes in schools. The framework of expansive learning with its seven sequences of actions can help researchers to analyse what happens in a longitudinal change process, while the theory of practice architectures can facilitate examination of how the different actions are situated in cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements. To conclude, the article provides knowledge about how to use the theory of expansive learning as a way to structure and analyse AR as well as knowledge about the benefits of using the theory in combination with the theory of practice architectures implementing reflective leadership in schools.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The protocol has been tested in ten countries as part of the international project, ‘Professional Learning through Reflection Promoted by Feedback and Coaching’ (PROFLEC).

References

- Aas, M. 2014. “Towards a Reflection Repertoire: Using a Thinking Tool to Understand Tensions in an Action Research Project.” Educational Action Research 22 (3): 441–454. doi:10.1080/09650792.2013.872572.

- Aas, M. 2017a. “Leaders as Learners: Developing New Leadership Practices.” Professional Development in Education 43 (3): 439–453. doi:10.1080/19415257.2016.1194878.

- Aas, M. 2017b. “Understanding Leadership and Change in Schools: Expansive Learning and Tensions.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 20 (3): 278–296. doi:10.1080/13603124.2015.1082630.

- Aas, M., and B. Fluckiger. 2016. “The Role of a Group Coach in the Professional Learning of School Leaders.” Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice 9 (1): 38–52. doi:10.1080/17521882.2016.1143022.

- Aas, M., and J.M. Paulsen. 2019. “National Strategy for Supporting School Principal’s Instructional Leadership. A Scandinavian Approach.” Journal of Educational Administration 57 (5): 540–553. doi:10.1108/JEA-09-2018-0168.

- Aas, M., and M. Vavik. 2015. “Group Coaching: A New Way of Constructing Leadership Identity?” School Leadership & Management: Formerly School Organisation 35 (3): 251–265. doi:10.1080/13632434.2014.962497.

- Aas, M., K.F. Vennebo, and K.A. Halvorsen. 2019. “Benchlearning – An Action Research Program for Transforming Leadership and School Practices.” Educational Action Research 28 (2): 210–226. doi:10.1080/09650792.2019.1566084.

- Brandmo, C., M. Aas, T. Colbjørnsen, and R. Olsen. 2019. “Group Coaching that Promotes Self-Efficacy and Role Clarity among School Leaders.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/00313831.2019.1659406.

- Britton, J.J. 2010. Effective Group Coaching. Tried and Tested Tools and Resources for Optimum Coaching Results. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Son.

- Brown, S.W., and A.M. Grant. 2010. “From GROW to GROUP: Theoretical Issues and a Practical Model for Group Coaching in Organisations.” Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice 3 (1): 30–45. doi:10.1080/17521880903559697.

- Bush, T. 2018. “Transformational Leadership: Exploring Common Conceptions.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 46 (6): 883–887. doi:10.1177/1741143218795731.

- Carr, W., and S. Kemmis. 1986. Becoming Critical: Education, Knowledge, and Action Research. London: Falmer Press.

- Darwin, S. 2011. “Learning in Activity: Exploring the Methodological Potential of Action Research in Activity Theorising of Social Practice.” Educational Action Research 19 (2): 215–229. doi:10.1080/09650792.2011.569230.

- Dempster, N., S. Lovett, and B. Fluckiger. 2011. “Literature Review: Strategies to Develop School Leadership.” Melbourne: AITSL.

- Dewey, J. 1966. Democracy and Education (1916). New York: Free Press.

- DuFour, R., and R.J. Marzano. 2011. Leaders of Learning: How District, School, and Classroom Leaders Improve Student Achievement. Bloomington: Solution Tree Press.

- Engestrom, Y. 2000. “Activity Theory and the Social Construction of Knowledge: A Story of Four Umpires.” Organization 7 (2): 301–310. doi:10.1177/135050840072006.

- Engeström, Y. 1987. “Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research.” PhD diss., University of Helsinki.

- Engeström, Y. 2001. “Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical Reconceptualization.” Journal of Education and Work 14 (1): 133–156. doi:10.1080/13639080020028747.

- Engeström, Y., and A. Sannino. 2010. “Studies of Expansive Learning: Foundations, Findings and Future Challenges.” Educational Research Review 5 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002.

- Fluckiger, B., S. Lovett, and N. Dempster. 2014. “Judging the Quality of School Leadership Learning Programmes: An International Search.” Professional Development in Education 40 (5): 561–575. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.902861.

- Foot, K.A. 2001. “Cultural-Historical Activity Theory as Practical Theory: Illuminating the Development of a Conflict Monitoring Network.” Communication Theory 11 (1): 56–83. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2001.tb00233.x.

- Fullan, M. 2014. The Principal. Three Keys to Maximizing Impact. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Fullan, M. 2015. The New Meaning of Educational Change. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Fullan, M. 2018. Surreal Change: The Real Life of Transforming Public Education. New York: Routledge.

- Habermas, J. 1987. Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason. Translated and edited by T. McCarthy, Vol. 2. London: Heinemann.

- Hargreaves, A., and M.T. O’Connor. 2018. Collaborative Professionalism. When Teaching Together Means Learning for All. Boston: Emerald Publishing.

- Hargreaves, A., and D.T. Shirley. 2012. The Global Fourth Way: The Quest for Educational Excellence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Harris, A., and M. Jones. 2019. “Leading Professional Learning with Impact.” School Leadership & Management 39 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1080/13632434.2018.1530892.

- Henriksen, Ø.H., and M. Aas. 2020. “Enhancing System Thinking – A Superintendent and Three Principals Reflecting with A Critical Friend” Educational Action Research Advance online publication. 1–16. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2020.1724813.

- Huber, S.G. 2011. “Leadership for Learning – Learning for Leadership: The Impact of Professional Development.” In Springer International Handbook of Leadership for Learning. Springer International Handbooks of Education, edited by T. Townsend and J. MacBeath, 635–652. Vol. 25. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Kemmis, S. 2009. “Action Research as a Practice-Based Practice.” Educational Action Research 17 (3): 463–474. doi:10.1080/09650790903093284.

- Kemmis, S., and P. Grootenboer. 2008. “Situating Praxis in Practice: Practice Architectures and the Cultural, Social and Material Conditions for Practice.” In Enabling Praxis: Challenges for Education, edited by P.S.P. Salo and S. Kemmis, 37–64, Rotterdam: Sence Publisher.

- Kemmis, S., R. McTaggart, and R. Nixon. 2014. The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research. Singapore: Springer.

- Kemmis, S., R. McTaggart, and R. Nixon. 2019. “Critical Participatory Action Research.” In Action Learning and Action Research: Genres and Approaches, edited by O. Zuber-Skerritt and L. Wood, 179–192, Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Kemmis, S., J. Wilkinson, and C. Edwards-Groves. 2017. “Roads Not Travelled, Roads Ahead: How the Theory of Practice Architectures Is Travelling.” In Exploring Education and Professional Practice, edited by K. Mahon, S. Francisco, and S. Kemmis, 239–256. Singapore: Springer.

- Kovačević, J., and P. Hallinger. 2019. “Leading School Change and Improvement.” Journal of Educational Administration 57 (6): 635–657. doi:10.1108/JEA-02-2019-0018.

- Leithwood, K., and K.S. Louis. 2012. Linking Leadership to Student Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Leithwood, K., J. Sun, and K. Pollock. 2017. How School Leaders Contribute to Student Success: The Four Paths Framework. New York: Springer.

- Lewin, K., and D. Cartwright. 1951. Field Theory in Social Science Selected Theoretical Papers. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Lincoln, Y.S., and E.G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Mulford, B., and H. Silins. 2003. “Leadership for Organizational Learning and Improved Student Outcomes – What Do We Know?” Cambridge Journal of Education 33 (2): 175–195. doi:10.1080/03057640302041.

- OECD. 2013. Leadership for 21st Century Learning, Educational Research and Innovation. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Puentedura, R.R. 2013. “SAMR: Moving from Enhancement to Transformation” Web blog post, May 29. http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/000095.html

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury. 2006. Handbook of Action Research: The Concise Paperback Edition. London: Sage.

- Richards, L. 2014. Handling Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Robertson, J. 2013. “Learning Leadership.” Leading and Managing 19 (2): 54–69.

- Roth, W.-M., and Y.-J. Lee. 2006. “Contradictions in Theorizing and Implementing Communities in Education.” Educational Research Review 1 (1): 27–40. doi:10.3102/0034654306298273.

- Schatzki, T.R. 2006. “On Organizations as They Happen.” Organization Studies 27 (12): 1863–1873. doi:10.1177/0170840606071942.

- Seiser, A.F. 2019. “Exploring Enhanced Pedagogical Leadership: An Action Research Study Involving Swedish Principals.” Educational Action Research Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/09650792.2019.1656661.

- Skoglund, K.N. 2020. “Social Interaction of Leaders in Partnerships between Schools and Universities: Tensions as Support and Counterbalance” International Journal of Leadership in Education Advance online publication. 1–20. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2020.1797178.

- Somekh, B., and K. Zeichner. 2009. “Action Research for Educational Reform: Remodelling Action Research Theories and Practices in Local Contexts.” Educational Action Research 17 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1080/09650790802667402.

- Stoll, L., R. Bolam, A. McMahon, M. Wallace, and S. Thomas. 2006. “Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Educational Change 7 (4): 221–258. doi:10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8.

- Stoll, L., and K.S. Louis. 2007. Professional Learning Communities: Divergence, Depth and Dilemmas. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill/Open University Press.

- Swaffield, S. 2004. “Critical Friends: Supporting Leadership,” Improving Learning. 7 (3): 267–278.

- Timperley, H., A. Wilson, H. Barrar, and I. Fung. 2007. Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education. http://educationcounts.edcentre.govt.nz/goto/BES

- Vennebo, K.F. 2015. “School Leadership and Innovative Work. Places and Spaces.” PhD diss., University of Oslo.

- Vennebo, K.F. 2016. “Innovative Work in School Development: Exploring Leadership Enactment.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 45 (2): 298–315. doi:10.1177/1741143215617944.