ABSTRACT

This paper aims to contribute fresh insights into youth participatory action research (YPAR) by using bell hooks’ engaged pedagogy to illuminate the process of co-designing a program for transition beyond secondary school. Engaged pedagogy is a critical pedagogy that combines critical consciousness and radical wholeness and seeks to foster a learning community. The 10-week YPAR included six staff collaborators (SCs) and five youth collaborators (YCs). Data comprised recordings of weekly collaborative group meetings; group interviews with SCs and YCs; and reflections and artefacts such as planning documents, graphic organisers and photographs. Informed by engaged pedagogy, findings are represented in two themes. First, YCs and SCs raised critical consciousness by collectively unpacking and critiquing the concept of transition. Critical consciousness allowed YCs to share their lived experiences and critique the dominant deficit discourse that represents transition as a linear process that needs to be smoothed by expert adults. Second, YCs and SCs demonstrated what hooks describes as radical wholeness, by bringing their whole selves to the YPAR. While some SCs and YCs struggled with the messiness of co-design as they negotiated expectations and roles, they learned to be honest and share their emotions, becoming what hooks describes as a learning community. Using an engaged pedagogy lens, we conclude by advocating for a holistic approach for YPAR in which educators take the risk of being vulnerable, sharing uncertainty and discomfort while encouraging youth to also take risks by bringing their whole selves to the process.

Introduction

We all kind of came in at the same playing field, like no one really knew what was going to happen, and then along the way everyone’s opinion was taken on board. It was very much group work. It wasn’t adults and young people. it was very much, we’re all in it together. (Sarah, Youth Collaborator, Focus Group)

This youth collaborator’s (YC’s) comment evocatively describes the collaborative work that took place during the process of co-designing a transition program through youth participatory action research (YPAR). It also emphasises the need for youth and adults to work as a learning community. This article explores that co-design process using bell hooks’ engaged pedagogy as a framework. We propose that there are clear synergies between hooks’ engaged pedagogy and YPAR, particularly hooks’ concepts of critical consciousness, learning communities, and radical wholeness.

The goal of this project was to involve youth in all stages of the research, co-creating knowledge by sharing power and supporting youth to take actions that contribute to social change (Cammarota and Fine Citation2008; Duke and Fripp Citation2022). YCs and staff collaborators (SCs) listened to each other’s stories, made sense of what we were learning together through ongoing and respectful dialogue, participated in decisions, and collaborated in meaningful action. YCs and SCs are co-authors of this paper.

Despite a growing body of research around YPAR in education (Cox et al. Citation2021; Einboden et al. Citation2022; Duke and Fripp Citation2022; Schwedhelm et al. Citation2021; Lau and Body Citation2021; Call-Cummings, Ní Sheanáin, and Buttimer Citation2022), this project is one of the first documented examples of using YPAR to understand post-secondary transition and the use of bell hooks’ engaged pedagogy to illuminate complexities and messiness in the co-design process. We begin this paper by introducing YPAR as a tool to co-design programs with young people in order to investigate power dynamics, histories of struggle, and the consequences of oppression in their lives and communities. Next, we discuss how using hooks’ engaged pedagogy as a theoretical lens helps us to understand the complexities of the co-design process. Informed by engaged pedagogy, we conclude with suggestions about how to take a holistic approach to YPAR in which educators take the risk of being vulnerable and share uncertainty and discomfort while encouraging youth to take risks by bringing their whole selves to the process (hooks Citation2009).

Youth participatory action research

YPAR challenges power dynamics and knowledge hierarchies in traditional research because it is committed to reframing who is allowed to design, conduct, and disseminate research (Cammarota and Fine Citation2008; Mirra, Garcia, and Morrell Citation2016). As Mirra, Garcia, and Morrell (Citation2016) outline, YPAR asks important questions to disrupt the traditional paradigm of knowledge production: Who tells the stories? How are they told? Who has the right to speak for the silenced? Who benefits from the stories that are told? YPAR positions young people as co-researchers whose experiences and knowledge are equally valuable to academic expertise and emphasises young people’s agency for social change (Desai Citation2019; Cox et al. Citation2021).

YPAR is critical research with origins in critical pedagogy and particularly in the work of Paulo Freire (Cammarota and Fine Citation2008). Freire (Citation1987) states that critical consciousness and praxis are key elements of social transformation. Critical consciousness focuses on achieving an in-depth understanding of the world, allowing for the perception and exposure of social and political contradictions (Freire Citation1987). Praxis combines action and reflection where students and teachers become subjects who can look at reality, critically reflect upon that reality and take action to change that reality (Freire Citation1987). YPAR explores ways to inquire about complex power relations, histories of struggle, and the consequences of oppression in young people’s lives and their communities (Desai Citation2019; Cammarota and Fine Citation2008; Luguetti et al. Citation2017). For Fine (Citation2011), this form of inquiry troubles ideological categories projected onto youth, such as delinquent, at-risk, promiscuous, damaged and victim, and contests the use of science to legitimise dominant policies and practices that reinforce stereotypes and fail to consider young people’s voices.

YPAR aims to mentor ‘young people to become social scientists by involving them in all aspects of the research cycle’ (Mirra, Garcia, and Morrell Citation2016, 2); from formulating research aims and collecting and analysing data to presenting findings and offering recommendations that lead to social action and meaningful change. As such, YPAR provides marginalised young people with an opportunity to exercise their agency by being civically engaged, developing their critical consciousness, and learning how to advocate for themselves and oppressed communities (Freire Citation1987; Cammarota and Fine Citation2008). In this sense, YPAR is ‘explicit and unapologetic in its goal of social justice and social transformation’ (Desai Citation2019, 126).

While there is a significant body of research around YPAR as a strategy to empower social change in schools, there remains a need for YPAR in the post-secondary transition area. Most of the literature on post-secondary transition has studied the transition from secondary education to higher education, emphasising a deficit discourse that represents transition as a linear process that needs to be smoothed by expert adults (Ecclestone, Biesta, and Hughes Citation2009; Gravett Citation2021). While some scholars have problematised this discourse (e.g. Gale and Parker Citation2014; Gravett and Winstone Citation2021; Gravett Citation2021; Coertjens et al. Citation2017), there remains a lack of work that critically investigates young people’s experiences after secondary school, particularly beyond transition to higher education. Further, there is a need to move from considering young people’s voices to inviting them as activists to understand the issues they face (Sellar and Gale Citation2011).

YPAR offers a useful theoretical and empirical contribution to rethinking and doing research into post-secondary transition by shifting the focus from managing transition (a deficit view) to recognising the value of challenges and difficulties as sources of growth and learning. YPAR also amplifies the richness, complexities and messiness involved in co-design with young people. The YPAR process allows young people to problematise the idea that adults need to help young people to have a smooth transition. In addition, YPAR acknowledges the multiplicity of young people’s lived realities, emphasising what young people can do and what resources they bring with them in understanding their post-secondary transition. To theoretically construct and analyse this process, we have supplemented YPAR with bell hooks’ engaged pedagogy (hooks Citation1994, Citation2003, Citation2009).

hooks’ engaged pedagogy: critical consciousness and radical wholeness

Engaged pedagogy emerged from the interplay of anticolonial, critical, and feminist pedagogies, committed to the Black liberation struggle (hooks Citation1994, Citation2009, Citation2003). As a Black feminist, hooks challenged multiple interrelated axes of oppression such as race, class, gender, and colonialism in her work. According to hooks (Citation1994, 2), education is ‘fundamentally political because it was rooted in antiracist struggle. Indeed, my [her] all-black grade schools became the location where I [she] experienced learning as revolution’ (hooks Citation1994, 2). In her embodied experience, the teachers in all-Black schools were Black women who insisted on the importance of education for freedom (hooks Citation1994, Citation2009, Citation2003).

Engaged pedagogy is a unique critical pedagogy grounded in critical consciousness and radical wholeness (Low, Citation2021). Critical consciousness or conscientização (in Portuguese) is a core element of hooks’ engaged pedagogy inspired by Freire (Citation1987). Critical consciousness includes achieving an in-depth understanding of the world and acting against the oppressive elements in one’s life that are illuminated by that understanding. hooks was inspired by Freire (Citation1987) and his view of education as the practice of freedom. For Freire and hooks, education is inherently political; a place in which we ‘entered the classrooms with the conviction that it was crucial for me [us] and every other student to be an active participant, not a passive consumer’ (hooks Citation1994, 14). Critical consciousness strongly critiques the systematised inequity, disconnectedness, and invisibility young people often experience within Eurocentric, socially reproductive, market-driven schooling (Sosa-Provencio et al. Citation2020; Ladson-Billings Citation2009; Valenzuela Citation1999). It positions young people as co-creators of knowledge in challenging the political nature of knowing and historicizes schooling within larger dynamics of power and privilege (Freire Citation1987, Citation1996).

hooks’ engaged pedagogy is concerned with spiritual recovery as well as political recovery (Low, Citation2021, 10). As hooks (Citation1994) herself claimed, ‘Progressive, holistic education, engaged pedagogy is more demanding than conventional critical or feminist pedagogy. For, unlike these two teaching practices, it emphasizes wellbeing’ (15). Like her critical consciousness, Citation1994) radical wholeness originated in embodied experiences of Buddhist studies where teaching is a healing practice that engages body, mind, and spirit (Low, Citation2021). hooks (Citation1994) credited her Buddhist teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh, with illuminating pedagogy as ‘wholeness, a union of mind, body, and spirit, stating that this insight was instrumental in overcoming the conventional Western academic belief that ‘a classroom was diminished if students and professors regarded one another as “whole” human beings’ (14–15).

Using hooks’ engaged pedagogy as a theoretical lens helps us to understand the complexities and messiness in the co-design process and our collaboration with each other.

Methods

This study comprised a ten-week YPAR. The intention was to involve youth to co-design a post-secondary transition experience. The context of the study was the Summer Gap (SG) project, an innovative collaboration between Victoria University (VU), the Hellenic Museum, AVID Australia, and YCs to (a) co-design a program to build young people’s agency and capabilities to negotiate post-secondary life choices, including pathways to further education and employment; (b) pilot the co-designed program; and (c) evaluate the pilot program and make recommendations for implementation beyond 2022. The SG Project offered an opportunity for authentic connection, sharing, learning, and collaboration, between staff and YCs.

The YPAR included six staff SCs and five YCs of diverse backgrounds and experiences with a common interest in co-designing a post-secondary transition experience (See ).

Table 1. Participants in the YPAR project summarised from positionality statements.

The first seven weeks were dedicated to developing capacity with the YCs and SCs (See ). In that phase, Amy facilitated collaborative group meetings to prepare participants to co-design the transition experience during the last three sessions, which were facilitated as intensives.

Table 2. Description of the sessions with the youth collaborators and staff collaborators.

Ethics approval for this study was received from the Victoria University Ethics Committee. All participants signed written consent forms at the beginning of their participation in the study, and their interactive consent was negotiated orally at regular intervals during the study, especially when explicitly generating data for reflections and focus groups.

Data generation included:

Weekly collaborative group meetings between YCs and SCs facilitated by Amy. These nine meetings were recorded and transcribed (70 pages).

Weekly reflections from YCs and SCs written after each collaborative group meeting about their experiences in the co-design and used to inform the weekly collaborative group meetings (37 pages).

Project artefacts including planning documents, graphic organisers, and photographs. All digital material was collected through Miro board (19 pages plus digital Miro board).

Focus group discussions with YCs and SCs facilitated by Carla and Juliana to identify the barriers and enablers encountered when co-designing the transition experience, emotions experienced, and learning throughout this process (30 pages).

Weekly SC meeting to reflect on the co-design of the transition program. Those meetings served as a peer debriefer and assisted with progressive data analysis (201 pages). The data were organised chronologically and filed by session date.

Data analysis involved ongoing dialogue between YCs and SCs. We were informed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2021, 331) in taking an approach that encompassed ‘reflexive engagement with theory, data and interpretation’. Our initial analysis was inductive. For example, the final collaborative meeting between SCs and YCs ended with a recorded collective reflection on the co-design process and its outcome. Afterwards Carla and Juliana developed a written summary of what they saw as key points. They shared the summary with YCs who had expressed interest in being co-researchers (Sarah, Aisha, Chloe), asking for their interpretations and whether there were any important points missing. In conversation, the YCs confirmed that the broad themes made sense to them as a starting point for further analysis. Carla, Juliana and Bill and three YCs (Sarah, Aisha, Chloe) then individually read all data (collaborative meetings, focus groups, reflections, and generated artefacts). YCs and SCs met twice to discuss our interpretations and collectively develop insights into the themes. As we shared our different perceptions and interpretations over several conversations, YCs became more active in co-constructing meaning. For example, Chloe clarified that her sense of ownership in the co-design grew as she came to understand the project better, while Patty explained that their sense of ownership grew as they connected the co-designed program with their own lived experiences and motivation to help others (Research meeting, June 2022).

Between meetings, Carla and Juliana iteratively wrote an interpretive narrative based on YC and SC discussions. As discussions progressed, Carla and Juliana noted some connections between YPAR and key elements of hooks’ engaged pedagogy, particularly concepts of critical consciousness, learning communities, and radical wholeness. Reflexive thematic analysis can be used with compatible guiding theory (Braun and Clarke Citation2021). Consequently, our analysis progressed from inductive beginnings to become deductive, as we used engaged pedagogy as a frame for co-constructing the findings presented below.

Findings and discussion

Guided by the work of bell hooks’ engaged pedagogy (hooks Citation1994, Citation2003, Citation2009), we constructed two main themes from our data: (a) raising critical consciousness about transition; (b) bringing our whole selves to the YPAR and sharing ownership of the co-designed program.

‘Transition sounds like we know where we are going’: raising critical consciousness about transition from secondary school

hooks proposes that it is essential that teachers and students raise critical consciousness through engaged pedagogy, allowing for the perception and exposure of social and political contradictions in education (hooks Citation2003, Citation1994). In this theme, we discuss how YCs and SCs raised critical consciousness by collectively unpacking and critiquing the dominant concept of transition as a linear process that needs to be managed by adults.

From the beginning of our co-designed program, YCs problematised dominant expectations and constructions of post-secondary transition, with a particular focus on the Australian Tertiary Admissions Rank (ATAR). The ATAR is used to rank comparative academic achievement and determine university entrance for most school leavers. In the first session, Chloe (YC) talked about one of her friends being known as a ‘Dux girl’ due to her high ATAR. Drawing on the YCs’ lived experiences, we critiqued the role of ATAR as the dominant way of constructing young people’s identities, questioning the assumption that an ATAR is definitive in either a positive or negative sense. We also discussed the failure of schools to make space for individuals and their dispositions and talents beyond the ATAR. After the co-design process, Sarah reflected on different experiences and pathways beyond secondary school:

[I]t’s similar to others like Chloe. She also had a friend who got the highest ATAR in her school and I did too and they both, they tried really hard, but then after it, it was kind a period of just like, oh, it’s kind of done now, and we also had friends who didn’t know what to do or didn’t take the straight pathway which is to go straight to uni […] so when we were exploring the whole word about transition and how I kind of was just like, I just, I don’t like the word, like it’s just, it doesn’t sum up what we’re trying to do and I explained why and the reasons I thought that and everyone took that on board.” (Sarah, YC, focus group).

Sarah questioned the use of the word transition. For her, ‘transition sounds like we know where we are going’. Some SCs initially resisted changing the name of the co-designed program, as the original project design was largely informed by the body of knowledge on transition. Further, the YPAR was funded as a transition project in the traditional linear sense. Sarah and other YCs helped the whole group to understand the benefits of using different language to describe the program that we were co-creating. Chloe (YC) suggested the name ‘Becoming You’. SCs and YCs agreed that Becoming You would better describe the fluidity and complexity of the co-design program. Critical consciousness emerged in a process where SCs and YCs negotiated different perspectives, experiences and sources of knowledge.

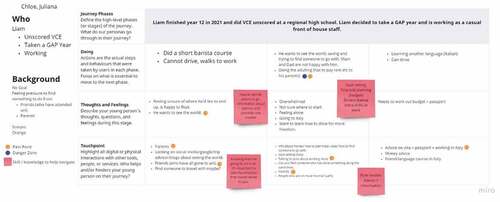

Building understandings based on YCs’ lived experiences was central to raising critical consciousness. For example, SCs and YCs worked on ‘journey mapping’ to story different lived experiences after secondary school. Journey mapping is a qualitative method of representing lived experiences as a social text with temporal and spatial aspects (Robinette Citation2022). provides one such example:

As described by Juliana (SC) and Chloe (YC), Liam’s story offers one representation of the complexities of transition. For Liam, transition was not smooth. He did unscored year 12, meaning he was not eligible for an ATAR ranking that would support direct admission into university. He did not finish year 12 with clear goals and he took a gap year after completing school. He was working as a barista. He was generally happy without having firm plans about what was coming next. However, Liam felt the influence of family and peers who had gone away to university in the city as a pressure to have defined goals. Juliana (SC) and Chloe (YC) created the Liam story as it represented some of the lived experiences Chloe shared with the group. All three of the journeys mapped during this activity represented non-linear experiences, providing an opportunity for YCs and SCs to build on lived experiences to problematise transition.

Our growing critical consciousness about transition was challenged by external pressures. SCs and YCs faced challenges when a member of a visiting panel of scholars asked the group whether parents should be invited to be involved in the co-designed program. Carla (SC) reflected on the influence of a visit by institutional project leaders during one of the co-design days:

In the second half of the intensive day, we had several outsiders arriving. […] Would the young people be comfortable with the outsiders? […] We had to explain the project to the outsiders […] I would rather prefer a panel of young people to judge our program. I would rather prefer young people’s suggestions/impressions. I would rather prefer to co-design this program in a community centre […] (Carla (SC), reflection, session 8).

According to that panel member, parents should be involved in the co-design project since they know best what young people need. This reflected the dominant account of transition that we had problematised. Sarah (YC) took the lead in responding that the program was being designed to support young people in taking control over their own lives and choices. Later, she reflected on what she had learned:

We were pitching our ideas, of the program to those kinds of higher-ups […] and when that question was asked, where do parents come into play with this, and how Amy [SC] could have answered that or you could have answered that or Juliana [SC] could have answered that, but Amy gave me the option to answer it and it just felt like it was a moment where I showed that I’m a part of it and I’m owning what I’m kind of creating, so I thought that was a great learning kind of thing for me (Sarah, YC, 2022).

Sarah (YC) was brilliant in defending the purpose of the created program and the panel member’s implied critique of the need to prioritise young people’s lived experiences and voices. She clarified that the program was being designed to support young people to have control over their own lives and choices and did not waver even when pressed. It was clear that the YCs had developed a strong vision for the program and were able to voice this beyond the group.

YCs and SCs raised critical consciousness by collectively unpacking and critiquing post-secondary transition to broaden our understandings of the meaning of transition. Our critical consciousness emerged from the constant reflection of the YCs’ lived experiences, represented in our collaborative work. By critiquing transition, we became aware of some of the social and political contradictions in the dominant account of transition as a linear process, which allowed us to plan for future actions, including design of the pilot program (hooks Citation2003, Citation1994).

‘Sometimes I would come in here confused about what we were doing’: radical wholeness and shared ownership of the co-designed program

Engaged pedagogy emphasises a holistic approach where teachers and students bring their whole selves (hooks Citation1994), being both honest and willing to share their feelings. For hooks, teachers must be actively committed to a process of ‘self-actualization that promotes their own well-being if they are to teach in a manner that empowers students’ (hooks Citation1994, 15). Connecting with each other openly and as whole people was essential for building connection and shared commitment to the co-design process, as Chloe (YC), explained:

I think that the biggest thing is the kind of bonds that everyone created in the team. I don’t know, I wasn’t … I came into this very beginning wanting to meet new people, but I wasn’t expecting […] to like those people […] I’m quite fond of everyone in the group, and that can be really hard to happen, especially when you’re co-designing something. […] I think one thing that kind of settled my nerves, actually having the first session and it was like one of those small kinds of insignificant activities like that, that red string activity that we did, that one where everyone was connected, it helped me realise that yes, these people that I’m sitting with are complete strangers, I don’t know them at all, but in a way, we’re all connected because we’re all standing here right now, and you know, this person’s been overseas and this person’s also been overseas, this person’s hiked this mountain, this person likes hiking, you know, like all of those little connections that you make between all those people, I think that kind of settled my nerves a little bit more (Chloe, YC, Focus Group).

In negotiating discomfort, the YCs shared feelings, including some that were difficult. For example, reflecting on the co-design process, Sarah (YC) mentioned how she would have liked more structure at the beginning when it was all ‘very up in the air’ and what we needed to do was far clearer than how:

The thing that came to my mind was maybe at the start have a bit more of a structure, because I found right at the start, like the first two meetings, it was very all up in the air, like it was kind of like, ‘This is what we have to do, but how we get there, I’m not too sure’.

I agree with what Sarah was saying […] but I think in a way, that not really having a full idea is really good because, as I said, we all got to kind of start from the bottom together, like if our youth collaborate and come into it with the other collaborators, knowing that, okay, we’ve kind of got a foundation program and you guys need to just kind of add a few little things onto there for us, I think not knowing was an advantage, in a way, like yes it was a disadvantage, but it was also an advantage for the team, all starting in the same spot, the lack of knowledge, not really knowing. Yeah.

I did agree with all of them on how it wasn’t really that clear. Sometimes I would come in here confused, sometimes, about what we were doing.

I think I was most uncomfortable at the beginning, like once again, when I didn’t really know what I was doing, I didn’t know if anything that I was saying or putting forward was actually helpful because I didn’t really know what I was doing. So I guess that’s when I was most uncomfortable (Focus group, YCs).

The discomfort was part of the co-design process. YCs and SCs did not know what the co-design project would look like or how many sessions would we need to run to co-design the program. The YCs had to learn how to deal with being confused and uncomfortable when they did not really know what they were doing. Chloe (YC) described how not knowing was important for the co-design project since it allowed us to create a safe space where SCs and YCs could contribute more equally. SC reflections mirrored those of the YCs, including commentary on the messiness of co-design, the intangibility of learning, and the ultimate growth in ownership and voice of the YCs. SCs also spoke about the complexity of the co-design process, and the importance of uncertainty and complexity in authentic collaboration. When SCs shared feelings of being confused and uncomfortable, it was an invitation for YCs to do the same.

Even though SCs and YCs struggled with the messiness of co-design in negotiating expectations and roles, together we had fostered a learning community whereby we could be honest and share emotions. Amy, as a caring facilitator, helped foster a safe space where youth could build relationships with each other and the SCs. Her friendly approach and open communication were mentioned as one of the strengths in the co-design process:

I think how casual Amy was about it all, like when we very first met, she was kind of like, ‘Oh I’ve been really stressed about this’, and it kind of broke the tension in the room, like nobody really knowing each other, or like people knew each other, but youth collaborators not knowing each other, youth collaborators not knowing the other collaborators, and how friendly and open she’s been, and then all the communication.

[…] I didn’t participate that much as in talking but it was nice to hear everyone’s thoughts on it. Because I kept being informed through emails, so that’s like, that was nice I could hear what was coming next […] I thought I wasn’t getting involved that much but Amy […] kept in touch with me.

I think it’s such a small detail, but the way that our conversations went, they were always around a table where everyone could see each other […] everyone was kind of having a conversation together and everyone felt like they were on the same level and you could see everyone going and talking, so I think that was one of the things that helped as well.

How we all kind of came in at the same playing field, like no one really knew what was going to happen, and then along the way […] everyone’s opinion was taken on board. It was very much group work. It wasn’t adults and young people, it was very much, we’re all in it together […] (Focus Group, YCs)

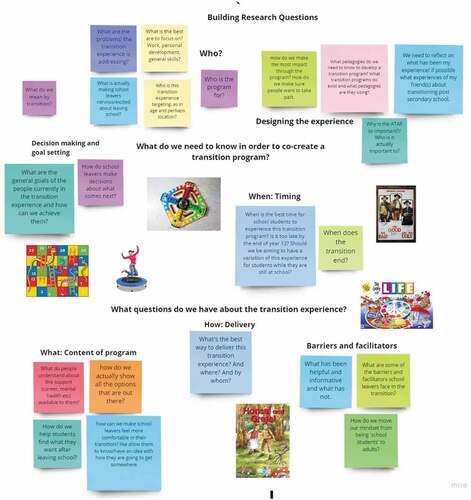

As described by the YCs, Amy actively facilitated the process of sharing power and creating a space in which all voices could be heard, and emotions be shared. This social interaction importantly combined with the material aspects such as the layout of the rooms where we met. For instance, in session 5, we utilised a Miro board to create research questions that guided program design. Amy asked, ‘What do we need to know in order to co-create a transition program?’ and ‘What questions do we have about the transition experience’?

Through two cycles of discussions involving small groups of YCs and SCs, we collaboratively created a representation of our discussion (see ). By providing a space where different perspectives, ideas and emotions could be shared and recognised, this online collaboration contributed to the formation of a learning community in which YCs grew increasingly active as co-researchers. However, SCs and YCs also faced the challenge of negotiating the different levels of engagement in the project, particularly online. To enable YCs’ participation, and due to COVID impacts, we decided to move online in sessions 3 and 4. Despite plenty of interactive activities, we collectively experienced session 4 as a session where YCs barely engaged. This lack of participation resulted in some assumption about YCs, such as the idea that YCs’ different levels of participation were related with their ‘lack of knowledge’ in this process. The SCs had to negotiate this assumption:

I think it’s starting to become apparent that we’re not going to be able to get this whole group together very often […] I’m keen to hear from the whole group …anyone’s had brainwaves or anything that we can be doing.

That’s the challenge of doing a project like this. It’s not like we’ve already got all the steps [.] It’s not going the way we’d hoped. Does that mean it’s not going, or is it just going in a different way than we anticipated?

I think there’s an added complexity with us in youth participatory action research, as well as using the dance analogy. If you think about a circle dance where you change partners as part of the dance, we’re all in this dance together. But our youth collaborators are dancing one style with other partners, and then they come back to us and we’re doing something completely different, and we do stumble a few steps as we’re working out how to do that. They are still very much being treated as young people who need to be taught.

That’s a bit of an assumption, though.

I don’t think we can make that assumption that they’re not being shifted in the way they engaged in school previously by the very nature that they got there in post-secondary (SCs meeting 5).

The SCs’ reflections helped them to question their own biases and assumptions to understand that youth participate in different ways. SCs then had an open conversation with YCs in terms of the best ways they would like to participate in this project. The SCs shared their lack of understanding about different levels of participation and asked the YCs’ help to understand what the co-design should look like. Together SCs and YCs decided that we would need intensive days to work with the YCs. We also paired YCs with SCs to work together in between sessions on research activities that would help inform the co-design of the program, such as exploring different lived experiences and understandings of post-secondary transitions. These collaborative activities offered a further opportunity to build relationships, recognise diverse perspectives and experiences and co-construct knowledge. While SCs and YCs were able to successfully recognise and negotiate how YCs participated in the YPAR, this did not always lead to the level of involvement that SCs had initially envisaged. For example, YCs were keen to engage in dissemination activities such as conferences and media production and were active in discussing the themes in the findings, including those presented here. However, YCs did not choose to participate in academic writing to the extent that SCs had hoped. Challenges in engaging YCs in collaborative writing highlighted that each writing group has their own contextualised story of writing together (Gardner Citation2018).

Engaged pedagogy does not seek simply to create spaces to empower students. It employs a holistic model of learning in which educators also grow and are empowered. This kind of empowerment can only happen when educators take the risk of being vulnerable while encouraging students to take risks (hooks Citation2009). The SCs had to be vulnerable in challenging their own bias and assumptions and asking the YCs for help in creating the environment where they could work together. By bringing our whole selves to the process, as SCs and YCs, and by being open about feelings, including uncertainty and discomfort, we built trust and connection with each other and in the co-design process that we developed together.

Conclusion

This paper illustrates the contributions of bell hooks’ engaged pedagogy (hooks Citation1994, Citation2003, Citation2009) to understanding the process of co-designing a post-secondary transition experience. Our findings add to the body of knowledge on YPAR and education (Cox et al. Citation2021; Einboden et al. Citation2022; Duke and Fripp Citation2022; Schwedhelm et al. Citation2021; Lau and Body Citation2021; Call-Cummings, Ní Sheanáin, and Buttimer Citation2022) by presenting a holistic approach for YPAR in which educators take a position of radical wholeness and critical consciousness through a learning community.

Critical consciousness allowed YCs and SCs to problematise the dominant deficit discourse which emphasises transition as a linear path into university. This awareness created spaces where YCs and SCs could see the political context in which the deficit view emerged, an emphasis on education as a means of generating productivity and standardisation of educational goals and assessment (Ecclestone, Biesta, and Hughes Citation2009; Gale and Parker Citation2014). Critical consciousness started with the understanding of YCs’ lived experiences. We incorporated Chloe’s suggestion to not use the world transition and we called the co-designed program ‘Becoming You’. Taking a more critical perspective, we located our concept of transition in the construct of transition-as-becoming which proposes that transition involves fluid, diverse, and multiple experiences (Gale and Parker Citation2014; Taylor and Harris-Evans Citation2018). This suggests a need to shift the focus from managing transition to recognising the value of challenges and difficulties as sources of growth and learning. Recognising post-secondary transition as complex, messy and troublesome also highlights how important it is for young people to be empowered as change-makers so they can effectively negotiate post-secondary school options and own their decisions.

Radical wholeness was evident when YCs and SCs brought their whole selves to the YPAR. Discomfort was part of the co-design process and YCs and SCs had to learn how to deal with being confused and uncomfortable when they did not really know what they were doing. Referring to engaged pedagogy, Sosa-Provencio et al. (Citation2020) suggest ‘this work approaches teaching and learning as the opening of physically spiritual places’ (356). Education as healing calls on educators to commit to a process of self-actualisation (hooks Citation1994). Such self-actualisation is very different to the individual self-fulfilment proposed by Maslow.Footnote1 It is a collective process of spiritual healing that encompasses the realisation of the self in relation to others (Low, Citation2021). When practising engaged pedagogy, educators must be willing to grow, take risks and be vulnerable, becoming empowered and empowering others in the process (hooks Citation2009). SCs were willing to take risks and be vulnerable, creating a space in which YCs were invited to do the same.

Additionally, critical consciousness and radical wholeness were nurtured in a learning community. When engaged pedagogy is practised effectively, the classroom becomes a learning community where teachers and students work together in partnership to co-create knowledge (hooks Citation2003, Citation1994). YCs and SCs fostered a learning community through dialogue and power sharing. Equitable participation was cultivated through caring facilitation, dialogue between the participants, and connection building. Additionally, YCs and SCs had diverse perspectives and experiences and the cultivation of a learning community allowed us to mutually recognise these and learn from each other in this YPAR. Teachers and students foster a learning community where they recognise and learn the cultural codes of others. This implies that we ‘learn to accept different ways of knowing, new epistemologies, in the multicultural settings’ (hooks Citation1994, 41).

This process was not without challenges. SCs needed to relinquish power to foster a fully cooperative and youth-driven process and critical consciousness to emerge. There were moments when SCs had different perspectives and disagreed with YCs. For instance, this became evident when Sarah and Chloe suggested another name for the co-designed project that conflicted with the area of knowledge and funding bodies. In the same way, YCs and SCs faced external pressure to change the critical perspective of transition. The inclusion of parents’ voices in the co-design that was suggested by a panel of scholars had to be challenged by the YCs and SCs. This negotiation required constant interrogation and resistance against impulses to manage or control the always-evolving, frequently surprising process of YPAR (Call-Cummings, Ní Sheanáin, and Buttimer Citation2022).

We also had to negotiate the different levels of engagement in the project. When the YC’s engagement levels diminished during online activities, we had to collectively select a series of intensive days (face-to-face) to work with the YCs and through informal spaces between the sessions. The SCs had to challenge their assumption that the YCs did not want to engage with the co-design project and understand that the sessions’ dynamics would explain the YCs engagement. By opening ourselves up to initiating safe spaces for growth and communication, we emphasised the relationality and potential for relationship-building and mutually transformative power.

Finally, while we recognised the importance of involving youth as much as possible in all stages of the research, the SCs struggled to promote youth involvement in writing academic publications beyond discussion of themes in the findings. It is hoped that this paper acts as a resource to guide future YPAR to interrogate the need for a holistic approach in which educators exercise their critical consciousness and radical wholeness when collaborating with young people. In a messy and uncertain process experienced in YPAR, an engaged pedagogy emphasises intentionality and humanity, creating a space where adults and young people care for each other’s well-being. Further, by emphasising radical wholeness and critical consciousness, an engaged pedagogy also enables an understanding of tensions and challenges as opportunities for participants to rethink themselves through the YPAR process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The concept of self-actualisation was brought into the mainstream by Abraham Maslow when he introduced his ‘hierarchy of needs’. For Maslow, it is the highest level of psychological development where the ‘actualisation’ of full personal potential is achieved, which occurs usually after basic bodily and ego needs have been fulfilled.

References

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021. “One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 328–352. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Call-Cummings, Meagan, Úna Ní Sheanáin, and Chris Buttimer. 2022. “School-Based YPAR: Negotiating Productive Tensions of Participation and Possibility.” Educational Action Research 30 (1): 76–91. doi:10.1080/09650792.2020.1776136.

- Cammarota, Julio, and Michelle Fine. 2008. Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Coertjens, Liesje, Taiga Brahm, Caroline Trautwein, and Sari Lindblom-Ylänne. 2017. “Students’ Transition into Higher Education from an International Perspective.” Higher Education 73 (3): 357–369. doi:10.1007/s10734-016-0092-y.

- Cox, Robin, Cheryl Heykoop, Sarah Fletcher, Tiffany Hill, Leila Scannell, Laura Wright, Kiana Alexander, Nigel Deans, and Tamara Plush. 2021. “Creative Action Research.” Educational Action Research 29 (4): 569–587. doi:10.1080/09650792.2021.1925569.

- Desai, Shiv R. 2019. “Youth Participatory Action Research: The Nuts and Bolts as Well as the Roses and Thorns.” In Research Methods for Social Justice and Equity in Education, edited by K. K. Strunk and L. A. Locke, 125–135. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05900-2.

- Duke, Adrienne M., and Jessica A. Fripp. 2022. “Examining Youth Participatory Action Research as a Context to Disrupt Implicit Bias in African American Adolescent Girls.” Educational Action Research 30 (1): 92–106. doi:10.1080/09650792.2020.1774404.

- Ecclestone, K., G. Biesta, and M. Hughes, eds. 2009. “Transitions in the Lifecourse: The Role of Identity, Agency and Structure.” In Transitions and Learning Through the Lifecourse, 25–39. Routledge.

- Einboden, Rochelle, Hazel Maxwell, Craig Campbell, Greg Rickard, and Marguerite Bramble. 2022. “Improving the First-Year Student Experience: A Critical Reflection on Co-Operative Inquiry as the ‘Last Loop’ in an Action Research Project.” Educational Action Research 00 (00): 1–15. doi:10.1080/09650792.2022.2034657.

- Fine, Michelle. 2011. “Youth Participatory Action Research.” In Keywords in Youth Studies: Tracing Affects, Movements, Knowledges, edited by N. Lesko and S. Talburt, 318–324. ProQuest Ebook. doi:10.4324/9780203805909.

- Freire, Paulo. 1987. Pedagogia Do Oprimido [Pedagogy of the Oppressed]. 17th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

- Freire, Paulo. 1996. Pedagogia Da Autonomia: Saberes Necessários a Prática Educativa [Pedagogy of Autonomy: Necessary Knowledge for Educational Practice]. Paulo Freire: Vida e Obra. São Paulo: Expressão …. São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

- Gale, T., and S. Parker. 2014. “Navigating Change: A Typology of Student Transition in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (5): 734–753. doi:10.1080/03075079.2012.721351.

- Gardner, Morgan. 2018. “Writing Together for Academic Publication as a Youth-Adult PAR Team: Moving from Distance and Distaste Towards Transformative Engagement.” Educational Action Research 26 (2): 205–219. doi:10.1080/09650792.2017.1329093.

- Gravett, Karen. 2021. “Troubling Transitions and Celebrating Becomings: From Pathway to Rhizome.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (8): 1506–1517. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1691162.

- Gravett, Karen, and Naomi E. Winstone. 2021. “Storying Students’ Becomings into and Through Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (8): 1578–1589. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1695112.

- hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

- hooks, bell. 2003. Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope. New York, NY: Routledge.

- hooks, bell. 2009. Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 2009. The Dreamkeepers : Successful Teachers of African American Children. San Francisco, CAS: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Lau, Emily, and Alison Body. 2021. “Community Alliances and Participatory Action Research as a Mechanism for Re-Politicising Social Action for Students in Higher Education.” Educational Action Research 29 (5): 738–754. doi:10.1080/09650792.2020.1772093.

- Low, Remy. 2021. Recovery as Resistance: Bell hooks, Engaged Pedagogy, and Buddhist Thought, Critical Studies in Education. doi:10.1080/17508487.2021.1990976.

- Luguetti, C., K.L. Oliver, L.E.P.B.T. Dantas, and D. Kirk. 2017. “‘The Life of Crime Does Not Pay; Stop and Think!’: The Process of Co-Constructing a Prototype Pedagogical Model of Sport for Working with Youth from Socially Vulnerable Backgrounds.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 22 (4): 329–348. doi:10.1080/17408989.2016.1203887.

- Mirra, Nicole, Antero Garcia, and Ernest Morrell. 2016. Doing Youth Participatory Action Research : A Methodological Handbook for Researchers, Educators, and Youth. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Robinette, Lee. 2022. “Investigating a Method as Part of the Action Research Process: Education Journey Maps.” Educational Action Research. doi:10.1080/09650792.2022.2113416.

- Schwedhelm, Maria Cecilia, April K. Wilhelm, Martha Bigelow, Nicole Bates, Teresa M. Vibar, Luis Ortega, and Michele L. Allen. 2021. “What is Sustainable Participatory Research? Insights from a School-University Partnership.” Educational Action Research 00 (00): 1–17. doi:10.1080/09650792.2021.2007783.

- Sellar, Sam, and Trevor Gale. 2011. “Mobility, Aspiration, Voice: A New Structure of Feeling for Student Equity in Higher Education.” Critical Studies in Education 52 (2): 115–134. doi:10.1080/17508487.2011.572826.

- Sosa-Provencio, Mia Angélica, Annmarie Sheahan, Shiv Desai, and Shawn Secatero. 2020. “Tenets of Body-Soul Rooted Pedagogy: Teaching for Critical Consciousness, Nourished Resistance, and Healing.” Critical Studies in Education 61 (3): 345–362. doi:10.1080/17508487.2018.1445653.

- Taylor, C. A., and J. Harris-Evans. 2018. “Reconceptualising Transition to Higher Education with Deleuze and Guattari.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (7): 1254–1267. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1242567.

- Valenzuela, Angela. 1999. Subtractive Schooling : U.S.-Mexican Youth and the Politics of Caring. New York: State University of New York Press.