ABSTRACT

Youth-led participatory action research (YPAR) empowers children and young people to platform their capability to create knowledge based on their lived experiences. It is this insider knowledge of childhood, which adult researchers lack, that enables the young to make significant contributions to educational research and to secure positive change. This article reports and reflects on YPAR in a secondary school in Thailand. Pupil researchers alongside the author, an adult ally, sought to establish if and to what extent the wider school population shared their dissatisfaction with the need for learners to take paid-for classes in addition to their regular school lessons. Through pupils taking photographs that captured their lived reality in regard to supplementary paid-for classes, the sharing of these images with the school leadership team, and the generation of data from a wider survey, the young people argued for, crafted, and secured positive change to their school lives and, potentially, beyond. YPAR enabled educational leadership to make evidence-informed decisions. However, the traditional YPAR concepts of confrontation and dialogue between young people and adults as equals were found to be contextually inappropriate, suggesting that, within power-rigid contexts, ‘powerful partnerships’ with adult allies are more comprehensible to those who live within those contexts, and, thus, more effective in securing positive change. The paper therefore suggests that strategies cognisant and sympathetic to established power hierarchies are needed if positive change to the lived realities of children is to be achieved. Considering this finding, reconceptualisations of YPAR and its catalytic research validity are offered alongside the results and discussion of the YPAR itself.

Introduction

Youth-led participatory action research (YPAR) centralises children and young people in the creation of new knowledge. Informed by lived experiences, children and young people investigate and reflect critically on the social issues affecting their lives and determine action that seeks to rectify self-identified problems (Cammarota and Fine Citation2008). YPAR challenges the deficit view of youth (Scorza et al. Citation2017) and it affords an opportunity for the traditionally subjugated voices of children and young people to establish themselves as transformative intellectuals (Morrell Citation2008). It empowers youth to platform their capability as creators of valid sources of knowledge as professionals within their own lived experience. It is this expert (McIntyre Citation2000), indigenous (Fals-Borda Citation2001), insider knowledge (Herr and Anderson Citation2005), which adult researchers lack that enables youth to make significant contributions to educational research (Rodríguez and Brown Citation2009). The recognition that their knowledge is useful and authentic empowers children and young people (Call-Cummings Citation2018) and it blurs the distinction between researchers and participants to ‘socialize the ownership among the community in which it is being done’ (Lozenski, Casey, and McManimon Citation2013, 83). Children and young people, as researchers of their own lives, develop an awareness of oppression in a process of conscientization (Freire Citation2005a). It is this awakening or sensitisation which serves to drive action that has the aim of decolonising their lives.

Within the context of YPAR undertaken in schools, when pupils offer a collective and reasoned voice based on sound methodological approaches to data collection, analysis, and presentation, YPAR can be a powerful vehicle of positive change. When children identify issues such as possible improvements to play facilities, when they suggest changes to canteen seating arrangements or, when school council members, representing their peers, relay fellow learners’ ideas to address a lack of sports equipment, teachers and educational leadership teams may regard such voice as responsible, the suggestions actionable, and the whole process a part of the wider process of learner engagement, skill development, and preparation for young people to take an active part as citizens in a democratic society when they leave school.

However, and something which forms the epistemological spine of this paper, what happens when learners identify issues about the equity of education provision? More specifically for the research which this article reports, what happens when young people identify supplementary paid-for education – the learning that takes place through parentally/carer funded additional out-of-school-time tutoring – as problematic for academic equity within a school? Can the space for dialogue remain and if it can survive, does it become more cramped? To what extent does pupil voice become problematic when children raise issues that run counter to the neoliberal hegemonic discourse of competitive individualism and put forward opinions which potentially have a negative impact on numerically measurable academic outcomes which are used to judge schools and those who work in them.

The purpose of this article is to report and reflect on a YPAR episode that I collaborated in with learners in a government-funded secondary school in northern Thailand. I will outline the research’s origins and methodology before setting out the findings. Finally, I will theorise why traditional power hierarchies between teacher and learner may limit or prohibit the potential positive change of pupil-led research. Reflecting on my experiences of YPAR, I will suggest that when uncomfortable issues are raised, in contexts where confrontation is neither accepted nor understood, there exists a real danger for the young and their adult allies to be seen as divisive troublemakers. I will plot some anticipatory paths which can be charted to navigate the possible dangerous terrain. These paths form part of a wider reflection on the YPAR episode and are offered as potential directions toward the establishment of authentic and sustainable spaces for research by children and young people. ‘Authentic’ is defined as unbounded spaces, spaces not restricted to comfortable issues, but rather contextually relevant spaces for the research and discussion of all issues which children and young people value as important.

The origin of the YPAR episode

The research topic was born by way of an intersection of concerns between a group of four Thai year 9 learners (15–16 years old), who took the lead in this research, and me, at the time a British teacher of mathematics in Thailand, their adult ally. The learners expressed dismay at the need for them to spend what they saw as an excessive amount of time and money engaged in supplementary paid-for education. The young people spoke of what they saw as the growing necessity for them to learn outside of the school gates to ensure competitive performances in high-stakes tests. They also lamented how educational corruption impacted their lived realities, and how they were effectively forced to study additional paid-for lessons with teachers who teach them at school to secure the necessary knowledge and favour to obtain good school grades. The distress they demonstrated when describing their frustrations made the research necessary and urgent.

I had, at the time, recently been introduced to YPAR as part of my postgraduate studies and I saw the potential for the learners to engage as researchers on an issue that they had identified themselves. As such, this research, given that it is youth-led, raises wider epistemological questions as it challenges boundaries drawn around some established norms, such as, who has the right to research teaching and learning, who has the right to create knowledge in relation to teaching and learning, and who has the right to have that knowledge listened to and acted on.

Before describing the methodology of the youth-led research it is first necessary to define supplementary paid-for education and explore why it is problematic for educational equity and learner well-being. It is to this that this article now turns.

Supplementary paid-for education

Definitions and growth of paid-for supplementary tuition

Paid-for supplementary tuition can be defined as the paid-for educational episodes with which a learner engages outside of compulsory school hours (Bray Citation1999). In the context of Thailand, the country in which this research is based, these episodes cover a wide range of educational experiences including individual tuition, large group lecture-style classes, both day and longer residential camps, and a relatively new innovation, but one which is expanding rapidly globally, online paid-for tuition. It does not include the unpaid help a learner receives from friends and relatives, non-government organisations, or free-to-access online tutoring. The definition for this paper is further narrowed, as it has been in previous research (Bray Citation1999), by the exclusion of additional classes in art, music, technology, and sport, rather focusing on the subjects commonly used in high-stakes examinations. In the context of Thailand, these subjects are mathematics, science, English as a second language, Thai language, and a collection of history, geography, religious studies, and politics grouped into a single subject referred to as social studies.

Research on supplementary education in Thailand has not been extensive (Lao Citation2014). However, the data which are available suggest that Thai learners’ engagement in supplementary paid-for education is amongst the highest in the world (OECD, 2012 cited in Park et al. Citation2016), and growing (Sinlarat, 2002 cited in Lao Citation2014). This engagement is seen in learners of all ages from pre-school through to postgraduate level and is driven in part, by the closeness to which the Thai education system is tied to high-stakes examinations (Saengboon Citation2019), the perception that regular schoolteachers are poorly qualified and use inappropriate pedagogies (Mounier and Tangchuang Citation2018), and the government’s free market ideology of consumer choice (Lao Citation2014).

The expansion in supplementary education is not a phenomenon restricted to Thailand, a similar picture is seen worldwide and has led to participation in it becoming a ‘standard feature of education in most nations’ (Mori and Baker Citation2010, 39). Consequently, more research is needed to further explore children and young people’s lived experiences of supplementary education worldwide. It is hoped that this article serves as a catalyst for this further research.

Problematising supplementary education

Research fails to find a consensus on whether supplementary tuition leads to academic improvement. Baker et al. (Citation2001) report positive links while according to Bray (Citation1999, 46) ‘Identification of the impact of private supplementary tutoring on individuals’ academic achievement is difficult because so many other factors are involved’. Despite this lack of clarity on its effectiveness, the main reasons given by parents for choosing to send their children to supplementary tuition or children choosing to go themselves are, to improve academic performance, to seek remedial help, to enable the inability to keep up in regular school, and to increase confidence in an academic subject (Bray Citation1999). If these desired outcomes are achieved then, on an individual learner basis supplementary tuition would appear beneficial.

A case could be made for supplementary education being, at least in part, an equity-producing technology. Drawing on Bourdieu’s work on fields and capitals (Bourdieu Citation2012) parents with sufficient economic capital can invest in education to compensate for their own lack of knowledge in an academic subject. Supplementary education may, it could be suggested, reduce inequality by offering a substitute for the unpaid family help that some children, those with parents or relatives who have a higher level of education, receive. However, this argument is problematised when it is considered that affluent families invest more in supplementary education than poorer households (Park et al. Citation2016). While acknowledging the age of the research, it was found in Japan that the most affluent families spend ten times the amount on private tuition than the least affluent do (Blumenthal Citation1992). More recent research, undertaken in the UK (Ireson and Rushforth Citation2011), Singapore (Tan Citation2017), and Turkey (Tansel Citation2013) report similar spending patterns aligned with parents’ socio-economic status.

According to Zhang and Bray (Citation2018), supplementary education widens inequity based on geographic lines. Children outside of urban areas are less likely to participate in additional paid-for tutorage, due to low household income and the clustering of tuition schools and experienced tutors in urban areas.

It is not just supplementary education’s negative impact on socio-economic equity which generates concern, The Ministry of Education in China (Chinese Government Citation2021), has implemented its double reduction policy, in part due to concerns that long hours of supplementary tuition pose risks to children’s mental health. Bray (Citation2013) similarly draws attention to how supplementary education leaves children little time for play and other activities.

The backwash of supplementary paid-for education on traditional schooling

Supplementary education is increasingly disrupting traditional schooling (Bray Citation2013). According to Bray (Citation2009) when teachers are aware that a high percentage of learners attend tuition lessons this may lessen their motivation to teach as they assume that the material has already been studied. This places learners who cannot afford supplementary education or choose not to engage with it at a disadvantage come test time.

Children who attend late-night tuition lessons may be tired and inattentive and may even sleep in regular school time classrooms (Kim, 2007 cited in Bray Citation2009). Having previously learned content in supplementary education episodes, learners have been noted to consider the traditional school as supplementary to the out-of-regular-school hours instruction they receive, this may lead to them being bored and potentially more disruptive (Jheng Citation2015).

The growth of supplementary education has created new income streams for teachers. Faced with the potential to enhance their income, some teachers reserve their best tuition for outside of the regular school walls. In Thailand, young people have traditionally studied extra lessons with the same teacher who teaches them in regular school hours, especially in academic subjects which carry greater weight in grade point average calculations. These additional lessons are not compulsory, however, as research has found in neighbouring Cambodia (Brehm and Silova Citation2014), and Latin America (Heyneman Citation2009), learners who attend have access to a more complete curriculum, potentially receive better grades, and are more likely to be allowed passage to study in the next school year group.

Methodology

The systematic enquiry sought to explore whether the negative feelings held by the research team in regard to paid-for tuition were shared by the wider pupil population of the school. If the data collected in the initial stages of the research indicated this was the case, then the research team would explore what action could be taken to address the shared problem in the next stage of the research.

The initial research question was:

To what extent is supplementary paid-for education a problematic outside of the research team members’ individual realities and ideologies?

The second research question would be:

What action can be taken to redress the perceived problematic?

The research team (four young researchers and the author, hereafter ‘we’) chose photovoice (Wang Citation1999; Wang and Burris Citation1997; Wang, Burris, and Ping Citation1996; Wang, Cash, and Powers Citation2000) as a research method to decentre the research team’s opinions and enable participants to explore their owned lived realities in regard to paid-for tuition without influence. A more in-depth introduction to the photovoice method, alongside the specific steps we took when employing the method, is given after this chronological description of the methodological process. The research team also decided to include a wider group of students in the research by issuing a survey to 50 students in each year group (years 7 to 12, 300 surveys in total) after the completion of the photovoice episode.

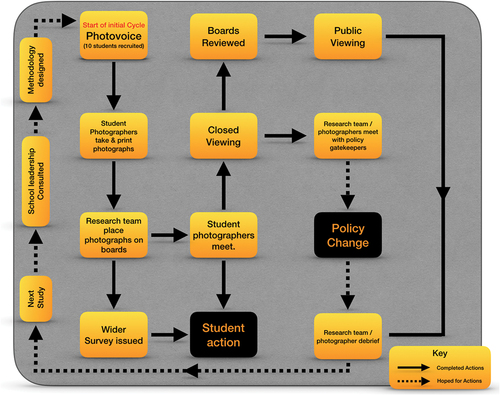

After the research team had agreed on research methods, the next step was to recruit ten photographers from the wider school population who would take photographs that represented their own lived reality of supplementary paid-for education. Again, the selection of the photographers is explored and problematised after the description of the research process. The methodology of our YPAR research is represented in .

Figure 1. An overview of the methodology (inspired by Wang Citation1999).

Each photographer was asked to take photographs of what supplementary paid-for education meant to them. They were given two weeks to take as many photographs as they liked. At the end of this 14-day period, each photographer was asked to select approximately ten photographs (a limit was necessary due to the budget constraints of this self-funded research) and was given photographic glossy paper and access to an inkjet printer to print the photographs. The photographers were asked to write as much or as little as they liked about each of their photos and to give each image a title. Each photographer was given a large envelope and was asked to place in it their photographs and accompanying texts. These envelopes were collected by the research team.

Exploring similarities and differences between individuals’ lived realities

After the photographers had submitted their pictures, they were invited to the focus group stage of the photovoice method. The group meetings were an opportunity for the photographers to critically reflect, both as individuals and collectively, on their lives, identify common themes, and then move forward to charting a course of action. One limitation of the study might be that the group discussions were not recorded. Transcripts might have yielded rich data on the thought process which came behind each photograph and the emergence of shared similar lived experiences with paid-for tuition. Those wishing to draw inspiration from our research may wish to consider recording group discussions.

The first stage of the focus group involved the photographers being asked to individually consider in silence all the photographs and texts. The photographs at this time had been placed on boards around the room by the research team. Each photographer was given a notebook should they want to take notes. Unlike in any other photovoice research we have read, we covered the texts with a blank piece of card that could be flipped to reveal the title and text. This allowed participants to individually attach their own meaning to others’ photographs before reading the photographers’ messages and titles. This innovation was an attempt to see if the photographs resonated in any way with anyone other than the photographer who had taken the photograph. As such, we attempted to maintain the individual voices of the photographers and avoid what has been referred to as ‘group think’ (Cooke Citation2001, 112–116) where individual critical thinking is replaced by conformity to the group.

In the second stage, after individually viewing the photographs, the photographers were asked to group together for the first time. One member of the original research team served as a group facilitator in these meetings. In our research, as Wang (Citation1999) suggests for research using the photovoice method, the photographers took a critical look at the photographs by using the framework provided by the acronym ‘SHOWeD’: What do you See here? What is really Happening here? How does this relate to Our lives? Why does this situation, concern or strength exist? What can we Do about it?” (Wang Citation1999, 188). The aim of the discussion was to encourage participants to look not just inwards at how paid-for tuition impacted themselves, but also outwards to explore others’ realities. As part of the discussion, the photographers jointly selected as many photographs as they wished to include in a closed viewing with the five-member institutional leadership team.

To maintain the voice of the participants, the research team did not code the photographs, but rather the photographers themselves highlighted themes that they saw as running through their shared life experiences. These themes were also used to code the responses of the wider survey.

Photographs chosen by the photographers were displayed on boards for a closed viewing by the school leadership team. Although attendance was not compulsory, all photographers chose to attend the closed viewing to explain the photographs further. The research team were also present. To protect the identities of specific photographers they were given the option of choosing to exclude their photograph from the closed viewing, claim ownership of all or specific photographs, or leave specific photographs with unassigned ownership. Most of the photographs were attributed to specific photographers.

After the closed viewing, a display of photographs that had been approved by institutional management was presented on boards that could be seen by the school community. This is problematic in terms of the powerful muting the voice of the young. However, our reasons for this are explained as part of the theorised ‘comprehendible voice’ below.

Following the public viewing, the research team and photographers held a debriefing with the photographers to discuss any possible developments in the process and to establish if and what further action could be taken. The action which was taken emerged from these discussions and from discussions within the research team.

Having outlined the methodology chronologically, a more in-depth focus is now applied to the photovoice method and how it was specifically drawn on and adapted by the research team.

Photovoice

Photovoice is a participatory action research strategy that is frequently used to enable sections of the community who have been traditionally silenced to find their voice (Sutton-Brown Citation2014). According to Palibroda et al. (Citation2009), photovoice privileges the authority of participant voice in research. The photovoice method is utilised not just to seek to rest at the uncovering of reality but to produce knowledge that breathes life into grassroots action and change. It is this commitment to seek change that holds the method true to its action research roots.

In photovoice, traditionally, cameras are issued to participants for them to capture their own lived realities, as experts in their own situation (Wang, Burris, and Ping Citation1996) rather than having these realities seen through an extra layer of the researchers’ subjectivity. These photos are then used to create discussion, critical thought, and policy change. As such, the research ‘oscillates between private and public worlds’ (Sutton-Brown Citation2014, 170). These group discussions are reminiscent of Freire’s (Citation2005b) culture circles, where participants reflect on their individual reality as it fits into wider frames of oppression and the need for change (Souto-Manning Citation2010).

The photovoice method has its roots in three epistemologies: the critical pedagogy of Freire, Citation2005a, Citation2005b) and his concept of conscientization, feminist theory, and advocacy photography. Originally conceived as photo novella (Wang and Burris Citation1994) it was later developed by the extension of a suggested structure for group discussion on the photographs which participants take (Wang Citation1999). The term photovoice is based on the word photo and the acronym VOICE which stands for Voicing Our Individual and Collective Experience (Wang Citation1999).

Photographer recruitment: recruiting mindful of group discussion

One critical reflection of the photovoice literature is the lack of critical discussion on groups’ composition. The lack of discussion is perhaps due to space restrictions of published articles, however, given the importance that group reflection has in the wider method of photovoice, it demands brief discussion.

Although no participant recruitment process is perfect, recruitment by advertising for volunteer pupil photographers by our research team would have been a considered and defendable strategy against criticism of participant selection from a position of researcher power. Perhaps the inclusion of all volunteers, which has been the case in some past research using the photovoice method (Wang, Cash, and Powers Citation2000) would have further bolstered a claim of egalitarian participant selection.

The research team wanted to recruit a diverse group of children. Research has shown (Checkoway Citation2011; Shier et al. Citation2014) that young learners are more likely to volunteer when they have sufficient confidence, social capital (Bourdieu Citation2012), and experience. We were concerned that recruitment by asking for volunteers would not necessarily allow for marginalised, seldom-heard voices to be involved or heard in the research. As a result, we decided against asking for volunteers and chose to form two groups of five diverse participants. This was made possible with the assistance of homeroom teachers. Given that we did not form groups from volunteers, we accept that we chose participants from a privileged position of researcher power. However, our justification was our aim to include learners from diverse socio-economic realities to capture supplementary paid-for education through multiple lenses.

Individual realities explored

(Wang Citation1999) stresses the need to train participant photographers before they go and capture images. This is usually done as a group exercise and traditionally includes critical issues such as ethical photography and ethical research. We felt that a group meeting before taking photographs might impact the photographs taken and thus negate the benefit which photovoice offers of allowing insight into individual realities. For this reason, we adjusted the method and met the ten photographers individually to inform them of the topic of research and to discuss the methodology and what part they would play.

The need for individual investigation before group discussion

We chose photovoice as it first aims to let an individual express their own reality rather than exposing them to the complexities of the group. Kothari (Citation2001, 147) states ‘decisions taken on the basis of a rapid participatory analysis reinforce a normative discourse that reflects a group consensus on what is usual and ordinary, while the complexities and “messiness” of most people’s everyday lives is filtered out’. As a research team, we wanted to capture this diverse messiness and we took deliberate steps to achieve this goal.

Although possibly a reflection of the age of some of the literature, one of the frequently mentioned aspects of the training is instruction on how to use a camera and how to take a picture. Unlike studies with older people as participants who may not be familiar with the technology (Ronzi et al. Citation2016), our participants had no such problems. We thought by training the photographers we would risk creating an outside influence of what constituted an appropriate picture. This outside influence on group processes has been referred to as coercive persuasion (Cooke Citation2001). We felt that training the photographers on how to take a photograph may prove counterproductive to our aim of capturing the participants’ authentic realities. Our decision is supported by Harrison (2002 cited in Catalani and Minkler Citation2010) who states that untrained photographers offer a rich source of data on cultural and social constructions.

Addressing positionalities and ethics through approach, method, and mindfulness

In the initial stages of working together as a research team, the youth researchers and I discussed the hierarchical power dynamics which existed within our group. I explained to the four researchers the ultimate duty of care I had as a teacher and my responsibility and commitment to undertaking ethical research that caused us and our participants no harm. I told them the value that extant research placed on children and young people as knowledge creators and how I wanted to support and participate in the project but not lead the research. It would be naïve to assume and erroneous to claim, especially with a culture where a pronounced power divide between adults and youth exists, that established positionalities dissolved instantaneously and equity spontaneously emerged from these conversations. Importantly, as is discussed later, adult positionality and power vis a vis that of youth is not universally problematic or unquestionably an obstacle in research with children and young people. However, for now, what these conversations allowed for was the making visible of our positionalities so that we were able to work on and with them as we set out to create positive change as a research team. Throughout the research project, I made time to reflect on these initial conversations to remain conscious of the multiple roles I was concurrently assuming in the research project, a deliberate everyday reflexivity.

The methodology was mindfully crafted. The use of photovoice, the participant photographers’ identification of themes from the images, and the use of these themes to analyse the data from the wider survey were conscious decisions that the research team took to distance our positionalities and opinions from the data that we collected.

I approached the research ethics of this project in a much more nuanced manner than the simple securing of institutional ethical clearance from the university at which I was studying. The mindfulness of ethics was a constant thread woven through my research; I had an ultimate responsibility of care to the children and young people I taught. My cognisance of this responsibility was especially important when joining with young people in YPAR, which is potentially dangerous research that challenges the established norms of a school, and, therefore, its organisational culture. The young children could have been seen as creating trouble and punished. I attempted to mitigate this risk by serving as a bridge between institutional leadership and the youth members of the research team. Ultimately, it is the ethics of care I have as a teacher, the emotional work that is teaching, and the awareness of student unhappiness, which made inaction on a student-identified issue as fundamentally problematic and even unethical.

Results

Initial reflections

Quantifying results is a difficult task for a study such as this which has the dual aim of investigating perceptions of oppression and promoting youth-identified possible change. Additional complexity is added in that the YPAR episode outlined in this paper is embedded in a much wider project of the establishment and continuing nurtured emergence of a learner-led research culture in the school where this research was undertaken.

Learners’ perceptions of supplementary paid-for education

The answer to the first research question (To what extent is supplementary paid-for education a problematic outside of the research team members’ individual realities and ideologies?) is complex. The photographers expressed both positive and negative feelings towards paid-for tuition (). This validates the research team’s decision to utilise the photovoice method to decentre our opinions from the research; we had only expressed negative feelings. Our findings also point to the danger of assuming YPAR in and of itself can represent the diverse views of children and young people beyond those involved as part of research teams; children and young people are not a homogenous group.

Table 1. Summary of photographer-identified themes in photographs and survey responses.

As mentioned previously, the photographers grouped their photographs by theme. The survey was coded using the themes that the photographers had identified during the group discussions of the images (). The coding process of the survey was a time-consuming task that involved the research team working together to colour code the responses. These coded responses were then further discussed and reflected on as a research team.

There are seven main themes: (a) Time, (b) Money, (c) Opportunity, (d) Necessity, (e) Friendship, (f) Guilt, and (g) Hope. Both the group of girls and boys identified time, money, opportunity, and necessity. The group of girls also identified friendship and guilt with the group of boys identifying hope as a theme.

From the participant photographers, pupils do not perceive supplementary paid-for education as universally bad, the opportunity to spend time with friends and make new friends are representative of this. However, many of the identified positives remain problematical in that they are indicative of deficiencies in the instruction given in the pupils’ compulsory schooling and raise difficult questions about compulsory schooling. A clear overall theme points to the perceived necessity of paid-for tuition and the hope and opportunity that it gives pupils for better lives. This was deeply troubling for me as a teacher working in compulsory schooling. Since learners perceive supplementary paid-for education as a necessity indicates the belief in traditional education as a great leveller has been damaged.

Learners’ reflections on the research process

Reflecting on the process, one photographer, Stephanie (a pseudonym), commented that what appeared at first a fun activity (the photovoice activity), did in fact force her to reflect on wider aspects of her life and she expressed feelings of shame and anger. She shared her thoughts with me and another member of the research team:

I started off thinking that this is going to be fun, take some pictures, talk about them, maybe speak to the school director, nothing really difficult in that. But when I was printing out the photos, I caught just how hard my mum works and just how tired she looked in the photograph. I know she wants the best for me, but I feel ashamed that I made her this tired and angry that she had to spend all this money on my education and angry that I didn’t get it in school. It made me stop and think about so much.

The photographs and the process of taking them prompted Stephanie to have very painful reflections on her life and how that life impacts her family. Her admission of shame and anger serves to sensitise me to the human emotion and suffering which lie beneath issues researched through YPAR in general and specifically for our research topic. I asked her if she wanted to discontinue her involvement in the research. She replied:

No, I want the director to know how tired my mum is.

Although ‘Stephanie’ is a pseudonym, aware that others would recognise her mother from the picture and being conscious of previous research which has problematised anonymity in participatory action research (Manzo and Brightbill Citation2007), we agreed to not use her photograph in the private or public showings or in this paper, Stephanie (as a photographer she was present at the private viewing with the educational leadership team) did, however, speak of her mother’s efforts to finance her supplementary tuition with institutional leadership.

Stephanie’s tears weigh uneasily with my responsibility as a teacher to safeguard learners’ well-being and serve as a poignant reminder that YPAR is not unproblematic. Participatory action research is an active endeavour, not passive labour. Stephanie’s tears are indicative of an emergence of her consciousness to oppression; participatory action research is emotional work.

Photovoice has been criticised for the negative impact on participants when anticipated change does not materialise (Catalani and Minkler Citation2010; Johnston Citation2016; Tanjasiri et al. Citation2011), a criticism also made against participatory action research in general (Klocker Citation2015). I attempted to manage expectations by drawing the research team’s attention to positive change when it did happen and by discussing the real possibility of achieving no change with them when asking for their informed consent.

From raised consciousness to positive change

Reflecting on the research, the use of YPAR served as an effective framework to scaffold the learners to critically reflect on their lived realities and to increase their level of consciousness of oppression. However, a consciousness of oppression without action is of limited value and might even lead to frustration. The claims that YPAR offers the potential to improve the lived realities of those involved rests to a large extent on the positive change which is secured. The production of knowledge by subjugated youth is admirable but what steps can be taken to realise actual change? As Lewin, states ‘No action without research, no research without action’ (nd. cited in Adelman Citation1993, 8). There appears to be an unbridged space between consciousness and change; a space which divides the awakened from the promised positive change. This space is not inert but rather may be filled with frustrations and degenerative fatalistic acceptance of fixed and unchangeable truths. In the next part of this article, I will explore how change can be achieved in contexts where traditionally cited confrontation is unintelligible.

A model of contextually aware YPAR

Although problematic in the sense that what I will now outline further places responsibility onto the oppressed for their own emancipation, contextually coherent ‘conscientização’ (Freire Citation2005a, 35), or what I term ‘contextually comprehendible critical consciousness’ offers real hope for change.

For voice to be not just heard but listened to, it must be spoken in a language that is understood by those who have the power to change policy. This is especially the case in Thailand where direct confrontation is culturally unacceptable, dangerous, or prohibited by law. For institutional leadership to listen to learner voice, what I will term ‘comprehendible voice’ must be articulated.

Hinton (Citation2008, 287) states, ‘Globally, asymmetrical power relationships between children and adults remain a pervasive barrier to children’s public action’. Within the context of a Thai school, horizontal dialogics (Fals-Borda Citation1991), positive confrontation (Fals-Borda Citation1991), dialogism (Bakhtin Citation1984), and mechanics of communicative action (Habermas Citation1984), are unhelpful and incoherent aims and processes for YPAR. The rigid difference in power between the children and adults precludes a dialogue of equals. Alternative strategies that make learner voice coherent must be engineered and employed to secure change. By remaining within culturally accepted power structures, voice is rendered acceptable and understood by those holding the power to change policy and practice. These strategies were: pacts with the powerful, pupil-teacher partnerships, and pedagogic opportunities. These strategies are now discussed.

Pacts with the powerful for comprehensibility

Our team sought change from the position of least power and therefore least ease, as Freire acknowledged, ‘the intellectual activity of those without power is always characterised as non-intellectual’ (Freire and Macedo Citation1987, 85). Given the large power divide between adults and children in Thai society in general, and between teachers and learners specifically, school-based youth-led research without the support of the institutional leadership would be incoherent for all stakeholders, including the young themselves.

Our unchallenging approach with institutional leaders, including them at all stages and providing them with a private viewing of the photographs appears to rest uncomfortably with the ‘contact zone’ of Torre et al., (Citation2008) who, drawing on the work of Pratt (Citation1991), define this zone as a ‘messy social space where differently situated people meet clash and grapple with each other across their varying relationships to power’ (Torre et al. Citation2008, 25). This zone is beyond comprehension in the context of children and adults in Thailand.

I do not frame the compulsory private viewing by the school leadership before the wider open display of the photographs and the censuring of three photographs as manipulative acts to maintain power. I frame these as cognisance of context and the need to negotiate pronounced disparities of power. The irreconcilable discomfort between photograph censorship and the realisation that local cultural awareness is key to securing permission to research serves to raise the consciousness of possible manipulation in research.

Pupil-teacher partnerships for comprehensibility

The role of adults in research led by children is sometimes lost in the prose of resistance, revolution, and emancipation. However, on reflection of the current research project, adults maintain a central and essential positionality in YPAR. The positive change that our research achieved was catalysed by an alliance between the young, who contextually occupy a peripheral space, and teachers, who occupy a position closer to the nucleus of policy-making decisions. Reflecting on the current research project, the ability of children to be researchers in matters which concern them most should not be seen as the just marginalisation of adults in research, nor should it be viewed as a move towards adults’ eventual total exclusion. Although this paper contributes to the literature which points to the need to redress the years of objectification of children by adults in research, it would be erroneous to see no role for adults in research which aims to create positive change in the lives of children.

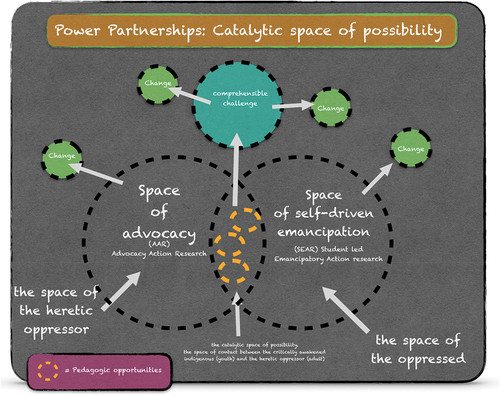

My research led me to the importance of what I call Advocacy Action Research (AAR) and Student-led Emancipatory Action Research (SEAR). Together AAR and SEAR can create a space to serve as a catalytic space for change (See ).

The combination of learners’ critical consciousness and the advocacy of the teacher, who has traditionally seen as an oppressor, allowed our research team, to make more comprehendible challenges to the accepted norm of supplementary paid-for education and its backwash. The combination of the rebel teacher and the professional knowledge of the young would appear to equate to Fals-Borda’s (Citation2001, 28) call to action for ‘the hopeful discovery of other types of knowledge from unrecognized worthy sources like the rebel, the heretical, the indigenous, and the common folk’.

My theory sits uneasily with Freire’s (Citation2005b) binary of the progressive teacher who is open to change, and the conservative teacher who is resistant to it. The possibility of being a ‘heretic within’ captures a more nuanced picture of the teacher who necessarily, for the creation of change, occupies multiple positionalities simultaneously.

Institutional leadership-supported actions such as the time-tabled homework workload and the provision of a budget, resources, and location for peer teaching serve as examples of what might be just the start of what is possible from the space where advocacy and self-emancipatory action research overlap. It is important to acknowledge that at the same time, this catalytic space does not preclude change that bypasses institutional leadership, as the establishment of Facebook pages, free website flyers, peer-led ‘homework help desk’ and teacher-led ‘confusion clinics’ indicate.

The structure of the research team allowed the opportunity to use the current social convention, which privileges adults over children, to attempt to co-create a new culture of young person research. Ozer et al. (Citation2010) use Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) metaphor of the scaffold to suggest that teachers’ help is essential in YPAR. However, our experience suggests the scaffold metaphor does not fully capture the role of the teacher in YPAR. To scaffold suggests something that is bolted on as support, a temporary external rather than as an integral part of the structure as in our research to make the research more comprehendible to the more powerful. In the struggle for the young to claim the right to research, our research demonstrates the effectiveness of the paradox of the central role of the adult. If adults remain as important players in youth-led research, it would suggest that power in YPAR is not a zero-sum game.

Perhaps the metaphor of the jigsaw puzzle is a more appropriate representation of the roles the young and adult allies play in the facilitation of youth-led change. For the achievement of the whole, intergenerational collaboration is required. Upon initiation of a project or on the commencement of the path towards organisational change more pieces must be placed by the adult. However, even at the end, some of the pieces need to be placed by an adult ally.

Pedagogic opportunity for comprehensibility

The pedagogical possibilities of pupil-led research were instrumental in the school leadership granting permission for our research. The researchers’ call for action regarding supplementary paid-for education was heard, at least in part, because the leadership team were introduced to how previous research had highlighted how youth-led research presents teachers with the pedagogic opportunity to nurture in children and young people a wide range of transferable life skills (Shamrova and Cummings Citation2017). In addition to learning how to generate, analyse, and disseminate data, the young researchers in our research developed their ability to speak in public, work in groups, relieve conflicts, and think critically.

Bridges to emancipation

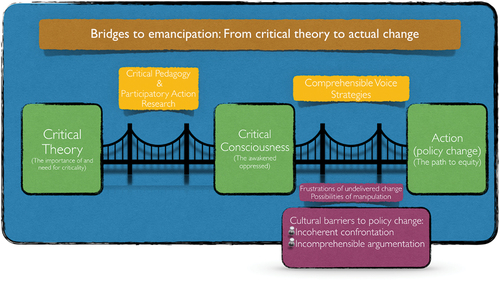

The three strategies of pacts with the powerful, pupil-teacher partnerships, and pedagogic opportunities form part of a wider model that charts theory to action. I termed this model as ‘the bridges to emancipation’ (See ).

Considering , participatory action research and critical pedagogy serve to raise critical consciousness. However, consciousness without action is only part of an unfinished journey to change. Through the utilisation of comprehensible voice strategies, a bridge is built between consciousness and action. These strategies recognise the need to be contextually aware, reject as a universalising assumption that confrontation is a path to greater equity, and make praxis possible.

The model captures a key finding which emerged from our research which was the need for YPAR to be contextually relevant to achieve the desired change. This supports earlier research which asserts that researchers’ awareness and deference to local contexts is essential for authentic PAR and the awakening of the local oppressed to their oppression (Fals-Borda Citation1995; Freire Citation2005a).

Action inspired by the youth-led participatory action research

Addressing the second research question concerning possible action to address the problematic aspects of supplementary paid-for tuition, encouragingly, action is already being taken (See ). Although this can be seen as only an initial step, it is with hope-laden optimism that the action already taken, and any subsequent action, will address at least in part the student-identified issue.

Table 2. Actions to date.

The action taken in school practices and the development of the researchers are two elements of positive change generated from the youth-led research. In a final reflection of our project, research validity of the current research is claimed in YPAR’s ability to change those involved in it.

Change as a legitimate claim to validity

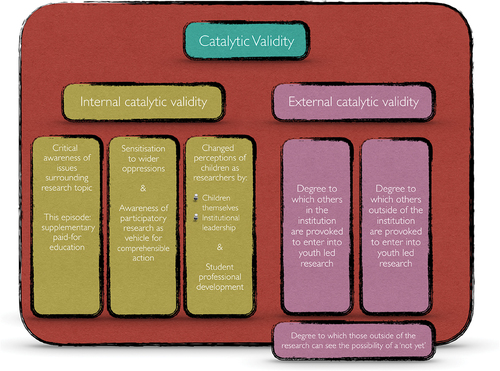

Lather (Citation1986, 272) defines catalytic validity as ‘the degree to which the research process reorients, focuses, and energises participants towards knowing reality in order to transform it’, and according to Scheurich (1986, cited in Cho and Trent Citation2006, 325) catalytic validity captures ‘the degree to which the research empowers and emancipates the research subjects’. Put simply, research changes the people involved in it.

Reflecting on our youth-led research, rather than using the narrow lens of change to the participants, I would like to zoom out to look at the change experienced by all involved in the research including the young researchers, the photographers, the children that completed the survey, the school management team, other teachers within the institution, me as a teacher and adult member of the research team, and also to include those outside of the institution who perhaps read this research or learn from it through more informal conversations. This zooming out necessitates an extension to the concept of catalytic validity.

I separate catalytic validity (See ) into two groups: internal catalytic validity and external catalytic validity.

Internal catalytic validity

Internal catalytic validity reflects the changes experienced by those involved in the research, and I separate it into three sub-sections. The first sub-section is indicative of the degree to which those involved have gained a critical awareness of the research topic itself. In the case of our research, supplementary paid-for tuition. The second sub-section refers to the extent to which increased consciousness of one oppression has sensitised those within the institution to other oppressions. The third and last sub-section captures the degree to which new outlooks of possibility are attached to children as researchers.

External catalytic validity

External catalytic validity draws on Fine’s (Citation2008, 229) concept of ‘provocative generalizability’ ; however, I have extended the concept to capture future episodes both within and beyond the original research site’s walls. External catalytic validity is high when others are inspired by the research to challenge the oppressive neoliberal hegemonic discourse and square up against established notions on who has the right to research and create knowledge. External catalytic validity is high when others are inspired to look for ‘what could be’ (Fine Citation2008, 229), pursue possibility, and challenge the structures or practices that are taken for granted. External catalytic validity is high when it installs hope in researchers of the not yet and creates discomfort with the accepted realities of the present.

Firm foundations laid

It is with guarded excitement that following our research institutional management commented on the usefulness of YPAR in the development of learner competencies and its ability to identify where change is needed. School leadership have asked subject department heads to ask pupils and staff to identify projects for research. So long as these projects can avoid being co-opted and remain true to the conscientization of the children, our research has catalysed the very embryonic stage of a larger movement of change within the institution. This is an encouraging step which reflects the emergence of a reimaging of whose knowledge is valued in school and whose knowledge can create change. Given the success of the current project, it is with cautious optimism that a prediction can be made that this fledgling development has the potential to mature into something growing and sustainable. Perhaps it is a truism that only time will tell, however the receptiveness of school leadership and the belief and energy of the learners are strong foundations on which to build.

It is much too early to realistically hope for change beyond the institution, but certainly, pupils and institutional management appear appreciative of the change that youth-led research has bought to date and enthusiastic about what it can lead to in the future.

Conclusion

The findings of the YPAR show that learners feel that their lives are being increasingly colonised by supplementary paid-for education. Their time is stolen by a technology that grows unchecked and unregulated in response to a credentialed competitive individualist society. Those with sufficient funds can invest, leaving others with the backwash that paid-for tuition has on compulsory education.

Our contextually relevant YPAR enabled individual feelings of oppression to coalesce into a shared consciousness of not just how things should not be, but what action could be taken to move towards what they should be. Through YPAR, the young researchers demonstrated their ability to systematically research and disseminate their findings on an issue which they saw as important. The methodological robustness of YPAR empowered the young researchers to demonstrate an authentic claim to the right to research and an ability to create new knowledge.

An important finding of this research is the need for the contextual relevance of YPAR. The danger remains that participatory action research can become a Eurocentric/Global North model for change that lacks contextual applicability and local coherence. To date, there has been an insufficient problematisation of the assumption of the possibility of democratic discourse. It is hoped that the YPAR outlined in this paper opens new possibilities for the decolonisation of children’s lives in contexts in which challenging by way of confrontation serves to make traditional participatory action research incomprehensible to the more powerful adult.

The discomfort in the necessity to enter pacts with the powerful who control policy is recognised, but encouragement is offered to grasp this discomfort as a tool to unmask tokenism, decoration, and manipulation (Freire Citation2005a; Hart Citation1992) and as sensitisation to the possibilities of fawning, dismissing, and ignoring the young (Perry-Hazan Citation2016).

It is with renewed hope that, through contextually comprehensible YPAR, children and perhaps other oppressed groups can exercise their right to research. Comprehensibility is key for that research to happen and for positive change to emerge from it. Only when children’s voices are understood will what they are saying be heard.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adelman, C. 1993. “Kurt Lewin and the Origins of Action Research.” Educational Action Research 1 (1): 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965079930010102.

- Baker, D. P., M. Akiba, G. K. LeTendre, and A. W. Wiseman. 2001. “Worldwide Shadow Education: Outside-School Learning, Institutional Quality of Schooling and Cross-National Mathematics Achievement.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 23 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737023001001.

- Bakhtin, M. 1984. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Blumenthal, T. 1992. “Japan’s Juken Industry.” Asian Survey 32 (5): 448–460. https://doi.org/10.2307/2644976.

- Bourdieu, P. 2012. “The Forms of Social Capital (1986, 2008).” In The E-Learning Reader, edited by S. de Freitas and J. Jameson, 273–274. London: Continuum.

- Bray, M. 1999. The Shadow Education System: Private Tutoring and Its Implications for Planners. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning. http://www.u4.no/recommended-reading/the-shadow-education-system-private-tutoring-and-its-implications-for-planners/.

- Bray, M. 2009. Confronting the Shadow Education System: What Government Policies for What Private Tutoring. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001851/185106E.pdf.

- Bray, M. 2013. “Shadow Education: Comparative Perspectives on the Expansion and Implications of Private Supplementary Tutoring.” Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences 77: 412–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.03.096.

- Brehm, W. C., and I. Silova. 2014. “Hidden Privatization of Public Education in Cambodia: Equity Implications of Private Tutoring.” Journal for Educational Research Online 6 (1): 94–116. https://www.pedocs.de/frontdoor.php?source_opus=8842.

- Call-Cummings, M. 2018. “Claiming Power by Producing Knowledge: The Empowering Potential of PAR in the Classroom.” Educational Action Research 26 (3): 385–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2017.1354772.

- Cammarota, J., and M. Fine. 2008. “Youth Participatory Action Research: A Pedagogy for Transformational Resistance.” In Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion, edited by J. Cammarota and M. Fine, 1–11. New York, N.Y, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Catalani, C., and M. Minkler. 2010. “Photovoice: A Review of the Literature in Health and Public Health.” Health Education and Behaviour 37 (3): 424–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198109342084.

- Checkoway, B. 2011. “What is Youth Participation?” Children and Youth Services Review 33 (2): 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.09.017.

- Chinese Government. 2021. “Opinions on Further Reducing the Homework Burden and Off-Campus Training Burden of Students in Compulsory Education.” https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-07/24/content_5627132.htm.

- Cho, J., and A. Trent. 2006. “Validity in Qualitative Research Revisited.” Qualitative Research 6 (3): 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106065006.

- Cooke, B. 2001. “The Social Psychology Limits of Participation.” In Participation: The New Tyranny? edited by B. Cooke and U. Kothari, 102–121. London: Zed.

- Fals-Borda, O. 1991. “Some Basic Ingredients.” In Action and Knowledge, edited by O. Fals-Borda and M. A. Rahman, 3–12. New York: Apex Press.

- Fals-Borda, O. 1995. “Research for Social Justice: Some North South Convergences.” Plenary Address at the Southern Sociological Society Meeting. http://comm-org.wisc.edu/si/falsborda.htm.

- Fals-Borda, O. 2001. “Participatory (Action) Research in Social Theory: Origins and Challenges.” In The Sage Handbook of Action Research: Participatory Inquiry and Practice, edited by P. Reason and H. Bradbury, 27–37. London: Sage.

- Fine, M. 2008. “An Epilogue of Sorts.” In Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion, edited by J. Cammarota and M. Fine, 155–184. New York, N.Y, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Freire, P. 2005a. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Continuum.

- Freire, P. 2005b. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

- Freire, P., and D. Macedo. 1987. Literacy: reading the word and the world. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Habermas, J. 1984. The Theory of Communicative Action (Vol. 1) Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Hart, R.A. 1992. “Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to citizenship.” Florence: UNICEF. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/childrens_participation.pdf.

- Herr, K., and G. L. Anderson. 2005. The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty. California: Thousand Oaks.

- Heyneman, S. P. 2009. “Education Corruption in International Perspective: An Introduction.” In Buying Your Way into Heaven: The Corruption of Education Systems in Global Perspective, edited by S.P. Heyneman. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Hinton, R. 2008. “Children’s Participation and Good Governance: Limitations of the Theoretical Literature.” International Journal of Children’s Rights 16 (3): 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1163/157181808X311141.

- Ireson, J., and K. Rushforth. 2011. “Mapping the Nature and Extent of Private Tutoring at Transaction Points in the English Education System.” Research Papers in Education 26 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520903191170.

- Jheng, Y-J. 2015. “The Influence of Private Tutoring on Middle-Class students’ Use of In-Class Time in Formal Schools in Taiwan.” International Journal of Educational Development 40 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.11.019.

- Johnston, G. 2016. “Champions for Social Change: Photovoice Ethics in Practice and ‘False hopes’ for Policy and Social Change.” Global Public Health 11 (5–6): 799–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1170176.

- Klocker, N. 2015. “Participatory Action Research: The Distress of (Not) Making a Difference.” Emotion, Space and Society 17:37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2015.06.006.

- Kothari, U. 2001. “Power, Knowledge and Social Control in Participatory Development.” In Participation: The New Tyranny? edited by B. Cooke and U. Kothari, 139–142. London: Zed.

- Lao, R. 2014. “Analyzing the Thai State Policy on Private Tutoring: The Prevalence on the Market Discourse.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 34 (4): 476–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2014.960799.

- Lather, P. 1986. “Research as Praxis.” Harvard Educational Review 56 (3): 257–277. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.56.3.bj2h231877069482.

- Lozenski, B. D., Z. A. Casey, and S. K. McManimon. 2013. “Contesting Production: Youth Participatory Action Research in the Struggle to Produce Knowledge.” Cultural Logic: Marxist Theory & Practice 80–95. https://doi.org/10.14288/clogic.v20i0.190893.

- Manzo, L. C., and N. Brightbill. 2007. “Toward a Participatory Ethics.” In Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place, edited by S. Kindon, R. Pain, and M. Kesby, 33–40. London: Routledge.

- McIntyre, A. 2000. “Constructing Meaning About Violence, School, and Community: Participatory Action Research with Urban Youth.” The Urban Review 32 (2): 123–154. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005181731698.

- Mori, I., and D. Baker. 2010. “The Origin of Universal Shadow Education: What the Supplemental Education Phenomenon Tells Us About the Postmodern Institution of Education.” Asia Pacific Education Review 11 (1): 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-009-9057-5.

- Morrell, E. 2008. “Six Summers of YPAR.” In Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion, edited by J. Cammarota and M. Fine, 155–184. New York, N.Y, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mounier, A., and P. Tangchuang. 2018. “Quality Issues of Education in Thailand.” In Education in Thailand. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, edited by G. Fry, 477–499. Vol. 42. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-7857-6_19.

- Ozer, E. J., M. L. Ritterman, and M. G. Wanis. 2010. “Participatory Action Research (PAR) in Middle School: Opportunities, Constraints, and Key Processes.” American Journal of Community Psychology 46 (1–2): 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9335-8.

- Palibroda, B., B. Krieg, L. Murdock, and J. Havelock. 2009. “A Practical Guide to Photovoice: Sharing Pictures, Telling Stories and Changing Communities [Online].” Manitoba: The Prairie Women’s Health Centre of Excellence. http://www.pwhce.ca/photovoice/pdf/Photovoice_Manual.pdf.

- Park, H., C. Buchmann, J. Choi, and J. J. Merry. 2016. “Learning Beyond the School Walls: Trends and Implications.” Annual Review of Sociology 42 (1): 231–52. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074341.

- Perry-Hazan, L. 2016. “Children’s participation in national policymaking: “You’re so adorable, adorable, adorable! I’m speechless; so much fun!” Children and Youth Services Review 67:105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.05.015.

- Pratt, M. L. 1991. “Arts of the Contact Zone.” Profession 33–40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25595469?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

- Rahman, M. A., and O. Fals-Borda. 1991. “A Self-Review of PAR.” In Action and Knowledge, edited by O. Fals-Borda and M.A. Rahman, 24–34. New York: Apex Press.

- Rodríguez, L. F., and T. M. Brown. 2009. “From Voice to Agency: Guiding Principles for Participatory Action Research with Youth.” New Directions for Youth Development 2009 (123): 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.312.

- Ronzi, S., L. Pope, D. Orton, and N. G. Bruce. 2016. “Using Photovoice Methods to Explore Older People’s Perceptions of Respect and Social Inclusion in Cities: Opportunities, Challenges, and Solutions.” SSM - Population Health 2:732–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.09.004.

- Saengboon, S. 2019. “Shadow Education in Thailand: A Case Study of Thai English Tutors’ Perspectives Towards the Roles of Private Supplementary Tutoring in Improving English Language Skills.” Language Education and Acquisition Research Network Journal 12 (1): 38–54. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1225683.pdf.

- Scorza, D., M. Bertrand, M. A. Bautista, E. Morrell, and C. Matthews. 2017. “The Dual Pedagogy of YPAR: Teaching Students and Students as Teachers.” Review of Education, Pedagogy, & Cultural Studies 39 (2): 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2017.1296279.

- Shamrova, D. P., and C. E. Cummings. 2017. “Participatory Action Research (PAR) with Children and Youth: An Integrative Review of Methodology and PAR Outcomes for Participants, Organizations, and Communities.” Children & Youth Services Review 81 (C): 400–412. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740917302086.

- Shier, H., M. H. Méndez, M. Centeno, I. Arróliga, and M. González. 2014. “How Children and Young People Influence Policy-Makers: Lessons from Nicaragua.” Children & Society 28 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2012.00443.x.

- Souto-Manning, M. 2010. Freire, Teaching, and Learning: Cultural Circles Across Contexts. New York: Peter Lang.

- Sutton-Brown, C. A. 2014. “Photovoice: A Methodological Guide.” Photography & Culture 7 (2): 169–185. https://doi.org/10.2752/175145214X13999922103165.

- Tan, C. 2017. “Private Supplementary Tutoring and Parentocracy in Singapore.” Interchange 48:315–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-017-9303-4.

- Tanjasiri, S. P., R. Lew, D. G. Kuratani, M. Wong, and L. Fu. 2011. “Using Photovoice to Assess and Promote Environmental Approaches to Tobacco Control in AAPI Communities.” Health Promotion Practice 12 (5): 654–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839910369987.

- Tansel, A. 2013. Supplementary Education in Turkey: Recent Developments and Future Prospects. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/S1479-3679%282013%290000022004.

- Torre, M. E., M. Fine, N. Alexander, A. B. Billups, Y. Blanding, E. Genao, E. Marboe, T. Salah, and K. Urdang. 2008. “Participatory Action Research in the Contact Zone.” In Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion, edited by J. Cammarota and M. Fine, 23–44. London and New York: Routledge.

- Vygotsky, L. 1978. “Interaction between learning and development.” Readings on the Development of Children 23 (3): 34–41.

- Wang, C. 1999. “Photovoice: A Participatory Action Research Strategy Applied to Women’s Health.” Journal of Women’s Health 8 (2): 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185.

- Wang, C., and M. A. Burris. 1994. “Empowerment Through Photo Novella: Portraits of Participation.” Health Education Quarterly 21 (2): 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819402100204.

- Wang, C., and M. A. Burris. 1997. “Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and the Use of Participatory Needs Assessment.” Health Education & Behavior 24 (3): 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309.

- Wang, C., M. A. Burris, and X. Y. Ping. 1996. “Chinese Village Women as Visual Anthropologists: A Participatory Approach to Reaching Policy Makers.” Social Science and Medicine 42 (10): 1391–1400. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00287-1.

- Wang, C. C., J. L. Cash, and L. S. Powers. 2000. “Who Knows the Streets as Well as the Homeless? Promoting Personal and Community Action Through Photovoice.” Health Promotion Practice 1 (1): 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/152483990000100113.

- Zhang, W., and M. Bray. 2018. “Equalising Schooling, Unequalising Private Supplementary Tutoring: Access and Tracking Through Shadow Education in China.” Oxford Review of Education 44 (2): 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1389710.