Abstract

This paper aims to show the levels of local and regional embeddedness of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (GMB) as well as its effects on the position of Bilbao within global networks. Although it is often said that the GMB as an international art franchise did not fit well with the local traditions, values and culture of Bilbao and the Basque Country, this paper attempts to show that the GMB is quite embedded into the local and regional context of institutions, private agents and policies. This effect increases with the growing recognition of the potential effects of the GMB on the creative and service industry in the Bilbao region. On the other hand, there is also an increasing tendency for Bilbao and the GMB to be included in global networks, as can be demonstrated by the branding effect of the GMB on the attraction of tourists or the increasing importance of the term “Bilbao” in semantic networks. The authors conclude with some recommendations on strengthening both the regional embeddedness and the global networking potential of museums in order to generate positive effects on urban regeneration and regional development.

1. Introduction

Bilbao has experienced an important development regarding urban and economic regeneration over the last 20 years. A sharp economic crisis during the 1980s triggered a search for new development possibilities based on public policies targeted at structural change and urban regeneration. The icing on the cake was the construction of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (GMB) in 1997. The “Bilbao effect” (also known as the “Guggenheim effect”) was born. The academic response to the “Bilbao effect” has been divergent. The impacts of the museum on the city's economic, social and urban landscapes have been analyzed from different perspectives. In a political economic perspective, the museum has succeeded as a tourist magnet and an image-making device, but has failed to restructure the region's uneven development and inequality (Rodriguez et al., Citation2001) and to solve the city's unemployment, poverty and gentrification problem (Vicario & Martinez-Monje, Citation2003; Doucet, Citation2009). Another perspective has, in contrast, focused on the direct economic benefits of the museum, i.e. image-making (Evans, Citation2003), direct returns, fiscal taxes and multiplicative effects on the economy (Esteban, Citation2000; Del Castillo & Haarich, Citation2004; Haarich, Citation2006; Plaza, Citation2006). However, nothing or very little has been said about the regional embeddedness of the GMB and its effects on the global networking of Bilbao. This paper tackles precisely this deficiency by analyzing these aspects before and after the opening of the museum. Accordingly, the paper is structured in six parts. At the beginning, we briefly introduce the theoretical assumption that regional embeddedness and global integration are two intertwined dynamic processes that reinforce each other. In Second 2, we summarize the impacts of the so-called Guggenheim effect as it is discussed in scientific journals, newspapers and expert circuits. In Section 3, we present a short history of the GMB and the main factors which were relevant to its genesis. Understanding the history and the different facets of the Guggenheim Effect will help settle the following debate on the quality of links of the museum and their effects on the city-region of Bilbao. Section 4 illustrates the quality of embeddedness of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, introducing the different levels where the GMB has developed local-regional linkages. Although it is true that local embeddedness was not one of the primary goals of the museum, one can observe today that the GMB has managed to develop relationships with multiple actors, initiatives and policies. Section 5 describes how global linkages benefit the GMB and the city-region of Bilbao through reinforcing effects. Finally, we summarize the beneficiary effects of the regional embeddedness and the global linkages on the development of the GMB and on regional development and discuss some policy implications.

2. Regional Embeddedness and Global Networking: Theoretical Assumptions

Regional embeddedness and global linkages represent complementary aspects of economic and cultural globalization. In this sense, embeddedness and parallel global networking have to be understood as a pair of dynamic processes that are strengthened mutually. According to Beckert (Citation2003, p. 769) embeddedness “refers to the social, cultural, political, and cognitive structuration of decisions in economic contexts. It points to the indissoluble connection of the actor with his or her social surrounding”. In the understanding of Granovetter (Citation1985, p. 490), embeddedness refers to the “role of concrete personal relations and structures (or ‘networks’) of such relations in generating trust and discouraging malfeasance”, establishing trust and order as prerequisites for economic activity and success. Coined by Granovetter (Citation1985), the term embeddedness makes reference to the effects of social relationships (e.g. trust and cohesion) on economic outcomes, involving the overlap between social and economic ties within and between organizations.

In the case of the GMB, our hypothesis is that regional embeddedness has been a necessary condition to create an attractive museum, carry out its social, cultural and artistic function and develop a sustainable activity in the medium and long-term, i.e. for return on the investment, both for the Basque Institutions and for the region as well as for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. The GMB has reinforced a shared cultural, social and cognitive context of the city, aligning the local actors with the “vision” of change. This Guggenheim-driven different and augmented context of the city has substantially increased the institutional “thickness” (Amin & Thrift, Citation1992) and the global visibility of the region.

On the basis of this, we developed five analytical dimensions of regional embeddedness that cover the given linkages due to the contractual relationships, but also the emergent linkages between the museum and the surrounding territory:

The GMB is also a social and economic space shaped by a global management structure and transnational production, marketing, networking and collaborative standards and practices. Its origin offers the GMB access not only to the other museums of the Guggenheim Network, but also to other alliances with cultural (and non-cultural) entities. This global network allows for “better exhibitions, better educational programs, allows more people to learn through art, attracts more and better artists and collections, shares different values, and contributes to enhancing better relationships between different countries, regions, cultures, and people” (Azua, Citation2005, p. 83). Important GMB assets, such as the brand, the management philosophy, the productive resources (paintings and art works) as well as knowledge in art management, come from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Before we begin to review these categories of embeddedness, we briefly present the Guggenheim “Bilbao effect” and the history of the GMB.

3. The Guggenheim Bilbao Effect in a Nutshell

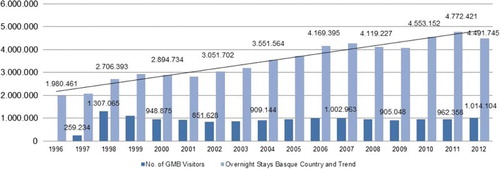

The GMB recently celebrated its 15th anniversary. During this time, it has been the focus of economists, planners and art managers seeking to find the success factors behind the so-called Bilbao or Guggenheim Effect.Footnote1 The total number of visitors of almost 15 million people from its opening in October 1997 until the end of 2012, the stable visitor figures of approximately 1 million per year confirming the estimations in the feasibility studies, the corresponding employment effects and income generated through taxes and tourism provide the hard facts that demonstrate the obvious success of the GMB as a cultural venture ().

The GMB can be seen as the trigger for Bilbao's successful shift of from an industrial port to a modern service-oriented tourist destination over the last 20 years. However, the GMB was not the only element in the redevelopment of the city. Behind the famous symbol were other local and regional initiatives that have contributed to the renewal of the city (e.g. the Metro Line, the cleaning of the River Nervión, the new airport, etc.). In fact, the urban change had already started before the GMB with the decision to implement the Strategic Plan for the Revitalization of Metropolitan Bilbao, which was presented in 1992 in response to a major economic crisis of the city-region. In this context, a number of activities were set in motion over the following years in order to improve the basic infrastructure of the Bilbao metropolitan area, to promote economic growth and to stimulate cultural demand and activity. The proposal to open a new art museum was one of 71 actions recommended by a group of experts. Of course, with the benefit of hindsight, we know that this was to be the most visible and symbolic action in the launching of the revitalization of Bilbao's economy. In fact, so much so that the GMB has become a symbol for (i) structural change and economic development, (ii), urban regeneration with a cultural focus, (iii) the use of a flagship architecture in urban renewal and (iv) local–global partnerships in museum management (Haarich & Plaza, Citation2010). These four facets of the Guggenheim Effect are briefly presented.

To start with, the effect on the economic development in Bilbao and its region is one of the most acknowledged representations of the Guggenheim Effect. Due to the stable visitor figures of the GMB and the attraction of tourists, regional economic activity—especially in the service sector—had been growing since practically the opening of the GMB, until the effects of the current crisis hit Bilbao. The GMB contributed to the creation and maintenance of approximately 1200 jobs (Plaza, Citation2010; Plaza et al., Citation2011). Moreover, there are important qualitative effects of the museum and its surrounding area, for example, on the general perception of Bilbao among the residents and tourists, on the quality of life in the inner-city area or on the self-perception of the city and its residents. The positive impact of the Guggenheim Museum on civic pride is now universally accepted. However, if we study the economic development of Bilbao and the Basque Country in general more in detail, we can see that a general economic boom over the last 15 years facilitated the creation of many new jobs in different sectors, especially business services and real estate, construction, even in manufacturing. The tourism-related sectors are not among the leaders with regard to employment impact, as one might think (). The review of the overall figures puts the effects attributed to the GMB into perspective. Moreover, besides the museum itself, other macroeconomic and social conditions (Plaza & Haarich, Citation2010) might have contributed to turning the GMB into an economic success for the city-region.

The second symbolic representation associated with the GMB is related to the urban regeneration process of Bilbao, which was partially based on cultural infrastructures. In the context of the urban renewal of Bilbao, and especially of the Abandoibarra area in the inner-city of Bilbao, the GMB has a representative function here. It was the first element of the Abandoibarra Master Plan, designed by Cesar Pelli, to redevelop the former industrial, port and ship-building district in the centre of Bilbao. Actually, the GMB had already been built before the Master Plan for the surrounding area was developed. Today, the 34.8 ha wide area is equipped with a new public park and leisure zone, walkways, a shopping mall with cinema, new residential buildings, a luxury hotel, new university buildings and a new office tower, which is now the highest building of Bilbao and creates a new visible landmark in the city centre. Although the present role of the GMB in this new area is clearly visible, contributing to the effective mixture of functions and land uses in the Abandoibarra area, it is but one element in the whole urban renewal concept. Other factors, such as the cleaning of the river, the creation of a footpath system out of the former railway lines, the connection of the museum by tram, management by the private–public entity Bilbao Ria 2000, etc., have also contributed to the success of the urban regeneration process.

Closely related to the previous aspect is the understanding of the GMB as a symbol for the use of architecture and flagship buildings in urban renewal and for city-marketing purposes. The GMB has been widely praised as an architectonical masterpiece, an icon for the current century, built utopia, titanium dream, “perhaps the only post-war building to challenge the Sydney Opera House in emotional resonance and immediacy of recognition” (Ellis, Citation2007). Here, the Guggenheim effect stands perhaps at the beginning of a new era in city marketing and strategic urban planning processes, where the involvement of famous architects or “starchitects” becomes a key element, not only for big cities, but also for second-tier cities like Bilbao.

Finally, another interpretation of the Guggenheim effect would be the impact of the GMB on the role of local–global partnerships in museum management as well as the shift towards perceiving a museum as a business venture. Adapted to each case, the new museum franchise model, where local and global interests meet, was subsequently used by the Tate Gallery (Liverpool, St Ives), the Louvre (Lens), the Centre Pompidou (Metz), the Hermitage (Amsterdam) and the forthcoming “V&A Dundee”, as well as other projects, especially in Abu Dhabi (Louvre, Guggenheim).

The term “Guggenheim Effect” is sometimes applied to some or all of these perspectives of impact and symbolic representation. Sometimes it is used to describe the simplistic and misleading causal relationship between a new museum and the economic upturn of a city, which in the case of Bilbao was based not so much on a direct relationship but more on a happy coincidence of many supportive economic and social factors. What is surely a “Bilbao effect” is the fact that the new Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art has been able to attract almost one million people each year to an old industrial city where tourism and high-level culture were practically unknown. This achievement alone is a true Guggenheim Effect and, as such, difficult to emulate.

4. The Genesis of the GMB as a Global Museum in the Basque Country

To understand the different shades of embeddedness which are presented in the next section, the history of the GMB and the entanglement of the different actors in its creation and management are briefly reconstructed.

4.1 An Essential Player Was the Guggenheim Foundation

When Thomas Krens become the New York Guggenheim's director in 1988, the museum was faced with a tight budget and Frank Lloyd Wright's building was in need of renovation. In 1990, the New York museum building's exhibition area and other spaces were expanded by the addition of an adjoining rectangular tower and the renovation of the original building. The same year, the foundation opened a Guggenheim Museum in the SoHo neighbourhood of downtown Manhattan. As a consequence, the New York-based Solomon R. Guggenheim foundation was in need of urgent liquidity. Krens was looking for a European city to open a Guggenheim outpost in order to rotate their collection through the Guggenheim satellites, trying to collect an additional cash inflow in this way for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

In Spain, a small number of key actors triggered the early stage negotiations and prepared the genesis of the GMB. The most relevant connectors were Carmen Gimenez (Former-Executive Advisor to the Spanish Minister of Culture, initiator of the Reina Sofia Museum and Curator of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum New York) and Alfonso de Otazu (former-collaborator of Carmen Gimenez at the Spanish Minister of Culture): Carmen Gimenez and Alfonso Otazu first proposed the idea of Bilbao as a site for a Guggenheim satellite to Thomas Krens in 1991. They played important roles as network connectors, facilitating the match between the Guggenheim New York and the Basque authorities.

On the local level, Juan-Luis Laskurain was one of the main players by all standards for two reasons. First, he was head of the public Treasury of Biscay and therefore in control of the public expenses. The Basque region enjoys fiscal independence under the Spanish constitution, enhancing flexibility in public expenditure-related decision-making processes. The public Treasury of Biscay had a solvent liquidity situation at the time. Second, Juan-Luis Laskurain was part of the local political elite. He was the main local visionary and promoter of the GMB project, and it was he who managed to convince all the local and regional authorities. In December 1991, a preliminary agreement was signed between NY and Bilbao, ratified 2 months later in NY. Basque institutions agreed to pay 2000 million pesetas (US$20.9 million back then) for the right to exhibit the Guggenheim Collection for 20 years. Juan-Luis Laskurain played an important role as the main local promoter and initiator of the Guggenheim Bilbao project, enabling the financial and political match between the Guggenheim New York and the Basque authorities. Juan Ignacio Vidarte was an assistant then to Juan-Luis Laskurain at the Treasury of Biscay. He played an important role in the implementation of the project, although his role as initiator was minor.

The BBV bank (Banco Bilbao Vizcaya, sponsor of both Guggenheim exhibitions held in Madrid in 1991, now BBVA) is one of the facilitating agents in the creation process of the GMB. When the Guggenheim Foundation NY rotated part of their collection through temporary exhibitions in several international cities, two of these exhibitions were held in the city of Madrid and both were sponsored by the BBV bank. The BBV is strongly connected to the city of Bilbao, in which both banks Banco de Bilbao and Banco de Vizcaya were founded in the nineteenth century, and Bilbao remains the headquarters of the bank.

As random factors in the creation of the GMB, we must mention, of course, the architect Frank O. Gehry and its outstanding design of the building, as well as the location of the museum on the riverside in an abandoned industrial area beneath an aesthetically challenging bridge. Other coincidental factors were the computer advancement called CATIA, a software program developed in the 1980s that allows architects to create curved forms instead of angles. Bilbao was the first large-scale project where CATIA was used to support documentation and coordination among multiple contractors during the construction process. The material innovation that complemented the software was titanium. Titanium provided a lighter alternative to steel and proved to become distinctive for the GMB. Already used in other works, Gehry's GMB was the first major work to draw the attention of the architecture community towards titanium.

5. The GMB and Its Embeddedness in the Bilbao Region

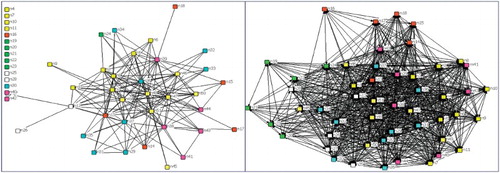

Our hypothesis is that the main cause of the GMB's success was the effective integration of the GMB in its new local and regional environment, which facilitated the combination of advantages of regional embeddedness, on the one hand, and of disembedded, transnational links, on the other hand. As can be observed in , the GMB managed—in its first 15 years—to establish effective and dynamic relationships with different spheres of the local–regional environment as well as with the global network of Guggenheim museums and other museums.

While in 1997 the GMB was a newborn entity, depending broadly on the American Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and only connected to some Basque Institutions without further links to other elements of the regional environment, the situation changed profoundly by 2012. In these 15 years, many different relationships have been established between the GMB and different spheres of the regional environment (institutional, urban, social, economic, strategic, etc.). The GMB has become an equal partner in the global Guggenheim Network and the worldwide network of museums (). Additionally, the GMB has become an important interface with which to connect elements of the local and regional environment to the transnational level and vice versa ().

Assuming that the effective embeddedness of the GMB into the local–regional environment is one of its success factors, in this section we analyse the quality of embeddedness of the GMB in more detail. The spheres of embeddedness we examined are: (a) political, (b) institutional, (c) economic, (d) artistic, (e) socio-cultural and (f) socio-strategic embeddedness.

5.1 Political Embeddedness

In the 1990s when the GMB emerged, it was conceived with a politically embedded strategy. The project was supported by all political levels (regional, provincial and local) which were governed at that time by the same political party, facilitating the necessary consensus for the partnership with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. This political consensus was a driving force for the GMB project and framed within the wider Revitalization Strategy for the Bilbao Metropolitan area. At the local–regional level, the urban revitalization of Bilbao, the economic structural change and the creation of a cultural attraction were the specific goals to which the GMB project should contribute. From the earliest stages and during the construction phase, the public alliance between the various administrative levels in the Basque Country and the public–private partnership was forged as the foundation of the current network of institutional relationships of the GMB. In 2014, the current agreement between the local–regional institutions and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation will come to an end and negotiations are already underway for a new agreement. The Basque Institutions are calling for more autarchy in decision-making, a fact that shows the profound institutional embeddedness and sense of ownership towards the GMB after 15 successful years. It remains to be seen if the GMB Foundation as a cornerstone in the Guggenheim Global Network will be able to come of age after almost 18 years in 2014.

5.2 Institutional Embeddedness

With regard to decision-making, the GMB's role within the global Guggenheim network has steadily become more important, especially in relation to the elder “brother”, the Guggenheim New York. Similar visitor figures () show the increasing relevance of the Bilbao delegation despite its shorter life. The integration of GMB's Director Vidarte into the management team at the New York headquarters and his responsibility for the development of the Guggenheim Museum Abu Dhabi show the increasing relevance of the Bilbao site. GMB's Director Vidarte joined the New York staff of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation as Deputy Director and Chief Officer for Global Strategies in November 2008.

Table 1. Number of visitors to Guggenheim New York museum and to the Guggenheim Bilbao (Annual data from 1997 to 2012)

The financial embeddedness is even more prominent. In order to guarantee the effectiveness of a museum as an economic engine, a sustained and continuous financial contribution from the public sector is required throughout the life of the museum. Unlike other autonomous Communities of Spain, the Basque Country and Navarre have almost full responsibility for collecting and administering their own taxes (McNeill, Citation2000; Uranga & Etxebarria, Citation2000). This gave the Basque authorities full autonomy and flexibility in the decision-making process with the Guggenheim NY Foundation, moving very fast at the early stages of the negotiation process (1992–1993). Regional public institutions, the Basque Government and Biscay authority fully funded the construction of the building, giving support to approximately 30% of the annual operating budget of about €25 million, whereas 70% of the budget comes from self-financing and sponsorship.

5.3 Economic Embeddedness

According to an impact study carried out on behalf of the GMB, the economic impact generated by the museum's activities in 2011 amounted to 311 million EUR. Through its activities, the museum has helped to generate 274.3 million euros in GDP, which works out to be 0.42% of the Basque Country's regional GDP. The museum has generated an additional 42.2 million euros in revenue for the Basque treasury and tax authorities, 0.39% of the total amount collected by the provincial treasuries, the revenues generated by the GMB and its visitors. In the same context, the museum has helped to maintain 5885 annual jobs (all figures GMBF, Citation2012).

Another form of economic embeddedness arises from the role of the GMB as a demanding client for advanced services and innovative technologies. The strong base of architecture and engineering companies in the city of Bilbao enabled the building of Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao. In the Basque Country, all publicly funded projects must hire local companies. In this context, a collaborative network for the design and construction of the GMB was set up under the leadership of the Bilbao-based engineering company IDOM as the executive architect for the project to work with the CATIA-software on the design of the GMB (Cacace et al., Citation2000; Yoo et al., Citation2006). It should be underlined that this relationship was made possible because of the strong industry base in the Basque Country, especially the experience with industrial and aerospace design.

A third dimension of the economic embeddedness is the, albeit moderate, influence of the GMB on the change in Bilbao's economic structure. Traditionally, industry has played an important role in the Basque economy, especially auxiliary industrial goods, i.e. intermediate inputs and equipment goods, with few final consumer goods at the end of the value chain (). In recent decades, as in other economies, advanced services have become the main activity (Plaza et al., Citation2013a). Bilbao and its region have seen an expansion in higher-end manufacturing and knowledge-intensive activities over recent years (). Today, professional services, information and communication technologies (ICTs), manufacturing, commerce and tourism are the main economic sectors, with a fast-growing creative sector (Haarich & Plaza, Citation2012).

A fourth aspect of economic embeddedness is the anchor position of the GMB in the development of the tourism sector in the Basque Country. Never before were the city of Bilbao, the Biscay Province or the Basque Country known as tourist destinations, perhaps with the exception of some surfing beaches and the early twentieth-century travel to the city of San Sebastian. Until 1997, people came to Bilbao exclusively on business trips or to visit family and friends, but almost never for leisure. Only with the GMB and the renewed inner-city development along the banks of the river has Bilbao become attractive for tourists and enjoys being a kind of insider tip in travel guides. The GMB is the main pole of attraction for tourists to Bilbao (Plaza, Citation2006). However, the stock of additional intangible assets is also relevant to the success of the tourist industry. Gastronomy is one of the most important cultural assets of the Basque Country, and there was already culinary tourism before the Guggenheim (Plaza, Citation2000). In fact, Spanish fine cuisine is mainly concentrated in Catalonia and the Basque Country. In the year 2012, 60% of the restaurants with 3 Michelin stars were concentrated in the Basque Country, whereas 40% were concentrated in Catalonia (Michelin-star awarded restaurants in Spain 2012). For the overall distribution of Michelin stars, 23% were concentrated in Madrid, 21% in the Basque Country and another 21% in Catalonia. In the GMB itself, there is also a Michelin-star restaurant. Aware of its role as an anchor point for Basque tourism, together with local and regional institutions, the museum participates in tourism fairs like FITUR and offers package deals through major travel and tourism agencies (GMBF, Citation2012).

A final form of economic embeddedness is the nominal relationship between the GMB and local–regional companies, especially those active at the international level (local multinationals). The GMB offers a formal sponsorship programme for corporate members in different categories, which are Strategic Trustees, Trustees, Corporate Benefactors, Media Benefactors and Associate Members. Strategic Trustees of the GMB are BBK (now Kutxabank, the regional Savings Bank), BBVA, Iberdrola and ArcelorMittal. At the beginning of 2012, 123 participating companies were signed up in the Corporate Members Programme of the GMB. Despite the worsening economic situation, the number of corporate members has remained constant over the last years (GMBF, Citation2012).

5.4 Artistic Embeddedness

During the first years of the GMB, many critics pointed out the lack of commitment with local and Basque artists in the art programme of the museum. However, the integration of Basque and Spanish artists was one of the goals of the GMB from the beginning. The GMB organized several major solo exhibitions on work by Cristina Iglesias (1998), the Eduardo Chillida retrospective (1999) and the Jorge Oteiza retrospective (2004). In October 2007, the GMB celebrated its 10th anniversary with 2 exhibitions, one of them being a set of site-specific installations by living Basque artists. In 2008, of the Guggenheim Bilbao collection's total of 51 artists, 21 were Spanish—14 of which were Basque (27.5%). In 2012, of 70 featured artists, 30 were Spanish, 20 of which were of Basque origin (28.6%). Works by these artists include sculptures by Chillida, Oteiza and Cristina Iglesias, as well as paintings by Jesus Mari Lazcano, Dario Urzay, Txomin Badiola, among others. Moreover, the GMB now supports young local artists through a new support programme for young local artists started in 2012. In the “Wall Guggenheim Bilbao” young artists living in the Basque Country were invited to present their work in the GMB. For the season 2012/2013, 6 artists were selected of 75 applications.

At the institutional level, the integration of the GMB into the existing museum and art landscape in Bilbao advanced positively. In this context, the GMB collaborates extensively with its strategic partner BBK, the regional Savings Bank, which was already a supporter of artists and art/cultural exhibitions in Bilbao before the GMB. The GMB also collaborates extensively with the Iberdrola Foundation and the BBVA Foundation. Additionally, the GMB and its visitors stimulated additional investments in the local art sector. Among these investments, the most noticeable venture has been the expansion of the Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts (MFA). Since the opening of the GMB in 1997, the number of attendees of the MFA expanded from 95,000 yearly attendees in 1996 to 260,000 in 2011. Especially, the combined Guggenheim-MFA entrance ticket, but also the modernized museum installations and the attractive exhibitions in the MFA can be seen as success factors (Plaza et al., Citation2009).

5.5 Socio-Cultural Embeddedness

After initial disbelief and scepticism among the local population, especially before the opening in 1997, the GMB was able to count on support from the first year on with the support of the Bilbao and Basque society. Proof of this support is the impressive number of “Friends of the Museum”, individual members of the GMB Membership Programme which in 2011 reached the figure of 16,239 divided among 6 different categories. Approximately 1000 people took part in the exclusively organized annual Members’ Day 2011. With regard to visitors in 2011, 38% of visitors came from Spain and the remaining 62% were foreigners. This trend is consistent with previous years, although a slight increase was registered in the percentage of visitors from the Basque Country (GMBF, Citation2012).

One of the key concerns of the GMB is education through arts and culture, both for adults and especially for children and young people. Among the specific programmes and projects we find educational materials, online teaching resources, virtual tours, educational spaces within the museum, children's activities, etc. The beneficiaries of these activities are estimated at more than 640,000 for the year 2011 (GMBF, Citation2012). Apart from the organization of exhibitions, the GMB organizes additional and complementary cultural activities and events. The GMB regularly organizes classic Guggenheim Bilbao Nights and Art After Dark sessions, an activity designed for young people that combines the museum's exhibitions with music sessions led by international DJs (GMBF, Citation2012).

Finally, the GMB has come to represent one of the distinguished venues for cultural or corporate events in Bilbao and the Basque Country. In 2011, the GMB hosted more than

80 special events of various types: social events, such as receptions, dinners, award ceremonies, and product launches, […]; professional gatherings, shareholders’ meetings, press conferences, and musical performances, […]. Less public events, such as the private tours of temporary exhibitions or the special privileges extended to corporate sponsors were among the primary reasons why many firms chose to hold their corporate events at the museum. (GMBF, Citation2012, p. 36)

5.6 Socio-Strategic Embeddedness

As an important player in regional tourism, cultural policy and local development, the GMB is becoming increasingly more involved, either actively or passively, in regional and local strategic planning processes. In the current Basque Country Tourism Policy, which was actually non-existent before the boom launched by the GMB, the GMB and some of its key values (culture, urban heritage and innovation) are cornerstones of the local–regional strategy based on culture, architecture and urban aesthetics, haute-cuisine and traditional Basque gastronomy. In the local strategies for the socioeconomic development of the Bilbao area, the support of the creative industries and the cultural sectors plays an increasingly key role. The GMB is an essential asset in proclaiming the relevance of the creative and cultural sector in Bilbao. In all official city-marketing strategies and campaigns, the GMB has become the new image and reference point—both visual and symbolic—for Bilbao and the Basque Country.

6. How Global Linkages Strengthen GMB's Regional Embeddedness

How important is the connection to key global actors in the process of regional–local embeddedness? The hypothesis of this paper is that the GMB has boosted global–local connectivity for the city of Bilbao. The GMB has improved the connectivity of local actors to the world, but equally importantly, has boosted the connectivity of global actors to the city. We can think of the city of Bilbao as being crisscrossed by the Guggenheim-related global circuits (e.g. first-tier exhibition circuits), putting this secondary city on the global map of highly specialized international circuits (Sassen, Citation2001). This approach allows us to detect the particular networks that connect specific activities in the city of Bilbao with specific activities in cities in other countries. As stated by Sassen (Citation2001), competitive advantage and international positioning of cities depends on their connectivity to highly specialized cross-border circuits. In this section, we analyse how global connections to the Solomon R. Guggenheim New York, other elements of the global Guggenheim network and other museums and institutions have affected the GMB and Bilbao and strengthened the GMB's local embeddedness, boosting the attractiveness and the competitive advantage of the city-region of Bilbao.

6.1 Economies of Scale and Scope in General Business and Art Management

The Guggenheim global network, which began in the 1970s with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum New York, has expanded since 1997 to include the GMB, the Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin (closed in December 2012), and the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. Museums in general operate with high fixed costs (Frey, Citation1998). The rotation of the permanent collection throughout the Guggenheim network between New York, Venice and Bilbao embarks on economies of scale. As the number of outposts promoted increased, more people could be reached per dollar spent. In this way, the cost of their exhibitions is distributed over a greater revenue base, so cost efficiency improves. As the Guggenheim network became large enough to take advantage of fixed operating costs, cost-savings and other economies of scale took place. The global structure of the Guggenheim Network and alliances with other museums also facilitate the rotation of art funds, increasing the overall quality of the exhibitions as well as reducing the related costs for access to art work. In addition, the global operating structure and the worldwide distribution of exhibitions facilitates access to private sponsors and enhances the museum's attractiveness to the general public and potential visitors from non-artistic circles. The global network of Guggenheim museums and collections contributes to the GMB's basic competences and also brings continuous flows of knowledge, innovation and creative ideas.

6.2 Access to High-Level Suppliers (Signature Architects, First-Tier Exhibitions, Notorious Curators)

How important is interaction with global actors in the process? Just like multinational companies (MNCs) can facilitate access to external resources and competences as well as coordination with internal and external actors (Heidenreich, Citation2012), the GMB has facilitated access to high-level suppliers and services. The connection with the Solomon R. Guggenheim New York Museum facilitated access to Frank O. Gehry, who otherwise probably would have been inaccessible at that moment. After the visible success of the GMB, other star architects like Zaha Hadid and Rafael Moneo were able to be attracted to Bilbao. The connection to the Solomon R. Guggenheim New York Foundation has also guaranteed Bilbao access to first-tier exhibitions, as well as notorious curators. Undoubtedly, the GMB is bringing an important representation of modern and contemporary art to the Basque region. It also created the option for the population to have an encounter with works of art by significant artists of the western European and American art scene of the twentieth century (Baniotopoulou, Citation2001). The number and quality of artists increased with the increasing success of the GMB exhibitions through a positive feedback-effect.

6.3 Enhanced Image, Global Brand and Recognition Value Even in Non-Cultural Circuits

The GMB (1997) opened around the same time as the Internet boom started to have an effect on global communication and news transfer. The heightened use of the social media more than likely leveraged an additional advantage in the form of more rapid information publication (Plaza et al., 2013b). The number of news items on the GMB increased even more to the extent that its silhouette was reported through North American news agencies, which enjoy a monopoly power worldwide at the time. The connection of the GMB to English-speaking, especially US media channels, acted as a huge loudspeaker worldwide, accelerating the branding effectiveness of the GMB.

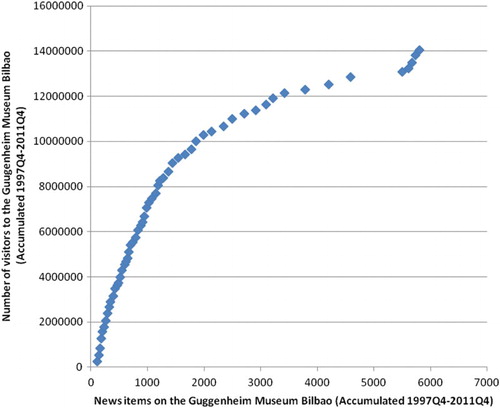

Cultural brands virtually cluster around media hubs, “global media cities” (Krätke & Taylor, Citation2004). Circuits (e.g. the Guggenheim museum circuit) that are well-connected to international media hubs (the Guggenheim Foundation is based in New York City) may tap into distribution channels more easily. From the opening of the GMB in October 1997, images of the Guggenheim Bilbao in online media accumulated at an increasing rate (). Image accumulation fuels increasing demand for place, which reinforces a brand and ultimately attracts cultural visitors ().

Figure 4. The relationship between online news items on the GMB and number of visitors to the GMB (accumulated quarterly data, 1997Q4–2011Q4).Source: Plaza (2012).

The reinforced recognition value of the brand “Bilbao” surely helped to attract new investments, such as the installation of the Digipen European Campus,Footnote2 and to win distinctive international prizes, such as the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize 2010 for urban development or the granting of the title “World Mayor 2012” to Bilbao's Mayor (winning against shortlisted finalists from Baltimore, Perth, Rio de Janeiro, Rotterdam and Ankara, among others).

6.4 Access to Strategic Alliances

The global linkages through the GMB facilitate access to strategic alliances, not only at the art level but also in relation to other networks. In this sense, we can differentiate between two related impacts. First, the use of the GMB as a symbolic reference and entry point and, second, the actual positioning of the GMB and Bilbao-related actors and institutions in international networks.

6.4.1 The museum as a symbolic point of reference

The GMB and its huge success has become the paradigmatic case of a flagship artefact put forward to revitalize a city's urban and economic fabric. The massive media attention generated by the so-called Guggenheim effect has captured the attention of policy-makers around the world, who travel to Bilbao to witness in situ the city's transformation from a run-down manufacturing city to the “new Mecca of urbanism” (Masboungi, Citation2001). The so-called “Bilbao effect” is diffused internationally through what may be called urban policy tourism, in other words short trips made to Bilbao by policy-makers to learn from their regeneration (Gonzalez, Citation2011).

Even more interesting is the GMB's vast power in building up symbolic capital (e.g. intangibles). In economic sociology, “symbolic capital” (Bourdieu, Citation1987) can be referred to as the resources available to an individual on the basis of honour, prestige or recognition, and functions as an authoritative embodiment of cultural value. Symbolic capital refers to peoples’ perceptions that the cultural-architectural facility embodies and represents. This symbolic capital (Bourdieu, Citation1987) has the potential to add value to economic processes in post-industrial societies. The growth of knowledge relies on cognitive content and capital such as reputation, which strengthens the bonds of networking and generates new ideas. This art-driven reputation can heighten internal and external networking as well as increase global actors’ willingness to cooperate with Bilbao-related actors (), reducing transaction costs and increasing the international attractiveness of Bilbao. The symbolic dimension of cultural facilities must be newly understood in the context of meanings and mental associations of art and culture brands (Scott, Citation2006; Power & Jansson, Citation2011). Part of building an effective brand of a cultural asset depends on understanding what drives these cognitive connections in their cities. Symbolic proximity can increase other types of proximity in the form of embeddedness, cognitive proximity and/or mental proximity (Boschma, Citation2005).

6.4.2 The GMB as a networking engine

The GMB has succeeded in connecting itself and the sphere of Bilbao to international (brand) networks which has also triggered connections to real personal and institutional networks. We can show this reality by comparing the network of news items related to the GMB and Bilbao during the periods before (1991–1995) and with the GMB (2007–2011). In order to compare the networks we selected seven brand circuits of key terms, mostly related to the GMB: the Guggenheim Network Museums, GMB trustees, GMB artists, Frank Gehry's masterpieces, signature architects, high-cuisine chefs, museums related to urban renewal and franchise museums. The database was created by recording the number of keyword hits for each term and each co-citation of terms in Google News for the periods 1991–1995 and 2007–2011. The results show considerably increased network connections and higher network density with central positions for the terms “GMB” and “Bilbao” in the 2007–2011 period. In the previous period (1991–1995), the network has a total of 354 ties out of 2601 possible links, and a density of 0.13, which is small for network standards (there are 15 nodes in the network that do not interact with any other nodes). In the period 2007–2011, the network has a total of 1724 ties out of 2601 links, and a density of 0.66, which is quite high ().

This shows that the GMB has boosted connectivity for the city of Bilbao (), providing favourable conditions for improving the region's competitiveness and attractiveness.

7. Conclusions: The GMB between Regional Embeddedness and Global Networking

The key questions addressed in this paper are how the integration of the city of Bilbao into international first-tier museums networks has facilitated (or constrained) its competitive upgrading, and to what extent it has led to the greater embeddedness of the Guggenheim Museum in the Bilbao economy. It has been illustrated that the city of Bilbao has substantially upgraded its economic position as a result of its international art-driven networks ().

Bilbao and its local–regional actors benefitted from enhanced access to global networks, whereas the GMB and the global players involved in the GMB developed strong multi-dimensional linkages to the local and regional fabric. These two trends related to the GMB have to be understood as simultaneous processes that strengthen each other mutually. The GMB has successfully developed a high degree of local–regional embeddedness over the last 15 years, covering different spheres from policy to economy. On the other side of the coin, the GMB has become embedded in global museum-driven brand networks, especially in relation to the global Guggenheim network and its strategic partners. From there on, the density of connections with other relevant societal areas all over the world has been steadily enhanced. Coinciding with the boom of ICT and Internet, the use of social media channels and digital branding has opened up the processes of image accumulation ( and ) and led to a strengthened recognition value for Bilbao as a city and for other local and regional players. In this sense, the GMB has benefited from a new logic of (virtual) agglomeration as a result of the Internet, and has also added attractiveness to the region through positive branding spill-over effects for the city and the related agents.

The results of the analysis lead to several implications for policy-making on the use of museums as engines for urban renewal and development.

Museums cannot be seen as islands in their local–regional setting, but require guided evolutionary processes to establish links with regional agents, policies, institutions and functional environments.

Global museums with important strategic partners might add recognition value and brand image to their cities and regions, which should be taken up and reinforced by open regional policies and complementary public and private initiatives.

Museums can open important gateways for the internationalization of firms and institutions and the attraction of talent. They should, therefore, not be neglected in regional policies regarding these issues.

Local and global networks are equally important for the development of a successful creative city. Museums can help to develop both, but need to be integrated in already existing bottom-up economic and social development processes. While museums can serve as anchor points, they need to gain their place and win the trust of the other regional creative agents to play a major role.

As one final conclusion of the analysis of GMB's local and global linkages, the striking similarity between the GMB as a global museum and the general concept of MNCs has become obvious. From the point of view of the dilemma surrounding the development of a multinational venture within a local–regional setting, the GMB can be seen as an atypical multinational enterprise as it combines the characteristics of a MNC and a local cultural tourism attraction. Since the function of service production and income generation is as important for the Guggenheim museum as for other companies, one could compare the performance of the GMB according to the same criteria that are usually applied in the analysis of MNCs. This assessment should not focus on the artistic or cultural value of the GMB or any other museum, which should obviously be evaluated by standards other than mere economic or business criteria. The GMB, like any other MNC, has to adapt to a national and regional context of norms and legislations, policies, plans and socio-cultural realities. “MNCs have to deal with national and regional contexts characterized by heterogeneous institutions, discourses, opportunities and constraints” (Heidenreich, Citation2012, p. 569). Like an MNC, the GMB needs to rely on local and regional sources of knowledge and develop relationships with suppliers, customers (visitors), competitors, external service partners, political support and qualified employees within the given regional and national legal, cultural and fiscal context (Cantwell & Mudambi, Citation2005). The GMB situates itself in the dilemma of regional–local responsiveness and global integration, well-known for multinational enterprises, as already described in the 1970s by Doz and Prahalad (Citation1991). The challenge of arranging regional links with the influences of globalization in order to optimize economic performance and regional development was already discussed as early as in 1992 by Amin and Thrift or, in relation to regional clusters, by Bathelt et al. (Citation2004). This line of thought could be a future field of research.

Acknowledgements

The Art4pax Foundation (Guernica) and the Basque Government (SAIOTEK) provided financial support for this project. We are grateful to Professor Manuel Cuadrado (Universitat de València) who kindly read an early draft of the article. He is not responsible for our interpretations.

Notes

1. For a full list of academic works regarding Bilbao and its regeneration process, see Art4pax Foundation (2012).

2. DigiPen Institute of Technology is a US-based institute of higher education of computer interactive technologies, digital technologies for games and simulation. Digipen has three campuses worldwide: DigiPen's central campus in Redmond (Washington) and two international branch campuses located in Singapore and Bilbao.

References

- Amin, A. & Thrift, N. (1992) Neo-Marshallian nodes in global networks, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 16(4), pp. 571–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.1992.tb00197.x

- Art4pax Foundation (2012) Scholars on Bilbao. Gernika. Available at http://www.scholars-onbilbao.info (accessed 11 January 2013).

- Azua, J. (2005) Guggenheim Bilbao: ‘Coopetitive’ strategies for the new culture economy spaces, in: A.M. Guasch & J. Zulaika (Eds) Learning from the Bilbao Guggenheim, pp. 77–100. Center for Basque studies conference papers series (Reno: University of Nevada)

- Baniotopoulou, E. (2001) Art for whose sake? Modern art museums and their role in transforming societies: The case of the Guggenheim Bilbao, Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 7, pp. 1–15. doi: 10.5334/jcms.7011

- Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A. & Maskell, P. (2004) Clusters and knowledge: Local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation, Progress in Human Geography, 28(1), pp. 31–56. doi: 10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

- Beckert, J. (2003) Economic sociology and embeddedness: How shall we conceptualize economic action?, Journal of Economic Issues, 37(3), pp. 769–787.

- Boschma, R. (2005) Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment, Regional Studies, 39(1), pp. 61–74. doi: 10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Bourdieu, P. (1987) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

- Cacace, K., Nikaki, M. & Stefanidou, A. (2000) Guggenheim Museum Bilbao – An evaluation of the cladding materials. Available at http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic502069.files/guggenheim.pdf (accessed 31 December 2012).

- Cantwell, J.A. & Mudambi, R. (2005) MNE competence-creating subsidiary mandates, Strategic Management Journal, 26(12), pp. 1109–1128. doi: 10.1002/smj.497

- Del Castillo, J. & Haarich, S. N. (2004) Urban renaissance, arts and culture: The Bilbao region as an innovative milieu, in: R. Camagni, D. Maillat & A. Matteaccioli (Eds) Ressources naturelles and culturelles, milieux et developpement local. (GREMI IV) Institut de recherches économiques et régionales IRER (Neuchâtel: Université Neuchâtel).

- Doucet, B. (2009) Global flagships, local impacts, Proceedings of the ICE – Urban Design and Planning, 162(3), pp. 101–107. doi: 10.1680/udap.2009.162.3.101

- Doz, Y.L. & Prahalad, C.K. (1991) Managing DMNCs: A search for a new paradigm, Strategic Management Journal, 12(S1), pp. 145–164. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250120911

- Ellis, A. (2007) A franchise model for the few- very few, The Art Newspaper, October 1, Issue 184, 1.10.07.

- Esteban, M. (2000) Bilbao, Luces y sombras de titanio. El proceso de regeneracion del Bilbao metropolitano [Bilbao, lights and shadows of titanium. The process of regeneration of metropolitan Bilbao]. (Bilbao: Servicio Editorial Universidad del Pais Vasco).

- Evans, G. (2003) Hard-branding the cultural city: From Prado to Prada, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27(2), pp. 417–440. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00455

- Frey, B. (1998) Superstar museums: An economic analysis, Journal of Cultural Economics, 22(2–3), pp. 113–125. doi: 10.1023/A:1007501918099

- GMBF (Guggenheim Museum Bilbao Foundation) (2012) Annual Report 2011. Available at http://www.guggenheim-bilbao-corp.es/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/MEMORIA-2011-ENG.pdf (accessed 30 December 2012).

- Gonzalez, S. (2011) Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in motion’. How urban regeneration ‘models’ travel and mutate in the global flows of policy tourism, Urban Studies, 48(7), pp. 1397–1418. doi: 10.1177/0042098010374510

- Granovetter, M. (1985) Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness, American Journal of Sociology, 91, pp. 481–510. doi: 10.1086/228311

- Haarich, S.N. (2006) Bilbaos Wandel auf Karten und Plänen. Über die Funktionen von Stadtplänen und Karten in einer sich regenerierenden Industriestadt, Raumplanung, 124, pp. 38–42.

- Haarich, S. & Plaza, B. (2010) Das Guggenheim-Museum von Bilbao als Symbol für erfolgreichen Wandel-Legende und Wirklichkeit, in: U. Altrock, S. Huning, T. Kuder, H. Nuissl & D. Peters, (Eds) Symbolische Orte. Planerische (De-)Konstruktionen. Reihe Planungsrundschau 19 (Berlin: Institut für Stadt- und Regionalplanung).

- Haarich, S. & Plaza, B. (2012) Creative Bilbao: The Guggenheim Effect, The Journal of Urban Planning International, 27(3), pp. 11–16.

- Heidenreich, M. (2012) The social embeddedness of multinational companies: A literature review, Socio-Economic Review, 10, pp. 549–579. doi: 10.1093/ser/mws010

- Krätke, S. & Taylor, P.J. (2004) A world geography of global media cities, European Planning Studies, 12(4), pp. 459–477. doi: 10.1080/0965431042000212731

- Masboungi, A. (2001) La nouvelle Mecque de l'urbanisme-La nueva Meca del urbanismo, Projet Urbain, 23, pp. 17–21.

- McNeill, D. (2000) McGuggenisation? National identity and globalisation in the Basque Country, Political Geography, 19(4), pp. 473–494. doi: 10.1016/S0962-6298(99)00093-1

- Plaza, B. (2000) The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and Basque high cuisine: An approach to the transmission of know-how, Tourism and Hospitality Management, 6(1–2), pp. 119–126.

- Plaza, B. (2006) The return on investment of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 30(2), pp. 452–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00672.x

- Plaza, B. (2010) Valuing museums as economic engines: Willingness to pay or discounting of cash-flows?, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 11(2), pp. 155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.culher.2009.06.001

- Plaza, B. (2012) Kultur als Zweck oder Mittel. Presentation at Akademie der Künste-Berlin [Academy of Art-Berlin]. 31.10.2012.

- Plaza, B. & Haarich, S.N. (2010) A Guggenheim-Hermitage Museum as an economic engine? Some preliminary ingredients for its effectiveness, Transformations in Business and Economics, 9(2), pp. 128–138.

- Plaza, B., Tironi, M. & Haarich, S.N. (2009) Bilbao's art scene and the “Guggenheim effect” revisited, European Planning Studies, 17(11), pp. 1711–1729. doi: 10.1080/09654310903230806

- Plaza, B., Galvez-Galvez, C. & Gonzalez-Flores, A. (2011) Testing the employment impact of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao via TSA, Tourism Economics, 17(1), pp. 223–229. doi: 10.5367/te.2011.0032

- Plaza, B., Galvez-Galvez, C. & Gonzalez-Flores, A. (2013a) Increasing advanced services through urban regeneration, Proceedings of the ICE – Municipal Engineer (In press).

- Plaza, B., Haarich, S. N. & Waldron, C. M. (2013b) Picasso's Guernica: The strength of an art brand in destination e-branding, International Journal of Arts Management, 15(3), pp. 53–64.

- Power, D. & Jansson, J. (2011) Constructing brands from the outside? Brand channels, cyclical clusters and global circuits, in: A. Pike (Eds) Brands and Branding Geographies, pp. 150–164.Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Rodriguez, A., Martinez, E. & Guenaga, G. (2001) Uneven redevelopment New urban policies and socio-spatial fragmentation in metropolitan Bilbao, European Urban and Regional Studies, 8(2), pp. 161–178. doi: 10.1177/096977640100800206

- Sassen, S. (2001) The city: Between topographic representation and spatialized power projects, Art Journal, 60(2), pp. 12–20. doi: 10.1080/00043249.2001.10792059

- Scott, A.J. (2006) Creative cities: Conceptual issues and policy questions, Journal of Urban Affairs, 28(1), pp. 1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.0735-2166.2006.00256.x

- Uranga, M., Etxebarria, G. (2000) Panorama of the Basque Country and its competence for self-government, European Planning Studies, 8(4), pp. 521–535. doi: 10.1080/713666417

- Vicario, L. & Martinez-Monje, P.M. (2003) Another “Guggenheim effect”: The generation of a potentially gentrifiable neighbourhood in Bilbao, Urban Studies, 40(12), pp. 2383–2400. doi: 10.1080/0042098032000136129

- Yoo, Y., Boland, R. & Lyytinen, K. (2006) From organization design to organization designing, Organization Science, 17(2), pp. 215–229. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1050.0168