ABSTRACT

Innovation strategies for smart specialization have become the new framework for organizing innovation support in European regions and states. This article examines how policy-makers conceive monitoring in the context of the current European territorial and innovation policy. In this setting, monitoring activities have to move beyond an audit-oriented logic in order to integrate a range of strategic functions such as producing the information needed to manage evidence-based policy decisions effectively and keep stakeholders informed and engaged in the policy cycle. To analyse this transition, we first conceptualize the logic of intervention of smart specialization. In a second step, we present the findings from a survey of policy-makers on their perceptions of this intervention logic and monitoring. We find that strategy monitoring is an exercise that must go beyond a narrow audit focus. Regional policy-makers involve stakeholders to interpret monitoring results for strategy revision and they adopt a priority-specific intervention logic, albeit with problems of implementing this logic in practice.

1. Introduction

This article provides first empirical evidence on how regional and national policy-makers in Europe conceive monitoring mechanisms for strategic interventions related to territorial innovation and development policies for smart specialization (European Commission, Citation2012; European Parliament and Council, Citation2013). To this end, we first develop an analytical scheme representing the building blocks of the smart specialization logic of intervention, and the causal relationships among them. We then present the findings from a survey of regional and national policy-makers responsible for the development of innovation strategies for smart specialization (RIS3) on their perception of those elements.

Monitoring the way policy interventions influence socio-economic processes is a crucial activity for informing their supervision and management. In its original Latin meaning, the word ‘monitor’ refers to a supervisor or to somebody or something that reminds or warns about something. That is, monitoring is supposed to serve as an early warning system that provides information on whether events are unfolding in a wrong or unexpected direction. It allows well-timed countermeasures to steer processes towards goals. In this ideal-type understanding, monitoring allows learning from failure before it actually materializes.

Monitoring is an integral part of policy-making and is usually seen as sister to evaluation. However, as a stand-alone exercise it has received less attention. In the archetypical policy cycle, monitoring appears towards the end of the different policy stages. Laswell’s (Citation1956) seminal work on decision-making distinguishes among several different stages, where only the last two – appraisal of policy decisions, and their eventual termination or modification – refer explicitly to monitoring. This stage model, although criticized by many for its overly functional and rationalist approach, has been a major influence on how we understand contemporary policy-making.

Most often, policy-makers – based on conviction or legal requirements – put strong emphasis on evaluating what has been done in order to learn for the future. Yet, the logical first step in this exercise is monitoring what is being done in order to progressively generate the information base needed for evaluation. In the context of European regional development policies, the European Court of Auditors (Citation2007, p. 7) states that ‘poor monitoring systems had hampered many evaluations’ in the past by not providing relevant information. This article seeks to redress this shortcoming in theory and practice by focusing on monitoring systems for territorial innovation strategies for smart specialization. We use the terms monitoring ‘system’ or ‘mechanism’ on purpose: monitoring must be institutionalized and designed with a view to enabling meaningful and informed decisions in order to support agile and responsive policy-making in a continuous way (Leeuw & Furubo, Citation2008).

The smart specialization approach is perhaps the most relevant recent example of a modern type of policy developed within, but not intended to be limited to the context of European Cohesion policy (Ahner & Landabaso, Citation2011; Barca, Citation2009; Capello, Citation2014; McCann & Ortega-Argilés, Citation2015). Smart specialization as a policy concept is underpinned by a comprehensive transformational agenda for the way territorial innovation policies are conceived and implemented. Smart specialization strategies or RIS3 introduce four main novelties: they (1) abandon the sectoral focus of traditional industrial policy in favour of identifying more narrowly defined and emerging activities within and across sectors; (2) prioritize only a limited set of such activities; (3) require policy-makers to identify RIS3 ‘priorities’ based on solid evidence and meaningful involvement of stakeholders such as firms, research organizations, universities and civil society and (4) build in monitoring mechanisms to effectively support policy learning, thus rendering the policy cycle sustainable and self-correcting. In other words, innovation strategies are emergent strategies that have to adapt to changing realities (Mintzberg, Citation1994). Similarly, monitoring mechanisms must be an emergent tool for strategic management.

In 2013, the inclusion of a monitoring mechanism in RIS3 became a new legal requirement for the funding of such strategies from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). European Commission guidance on smart specialization stresses the necessary role of monitoring systems in strategy design from the very beginning of the process (European Commission, Citation2012). Since a transparent evidence base is a defining feature of RIS3, monitoring de facto starts with strategy design and should percolate throughout the whole policy cycle. Despite these formal provisions and current policy advice, neither conceptual work on smart specialization nor the European regulation provides details of what should be monitored and how. There are no ‘official’ conceptual models or proposals for developing monitoring systems that can guarantee ongoing policy learning at the strategic level. Gianelle and Kleibrink (Citation2015) made a first effort to address these issues by conceptualizing the logic of intervention of RIS3; this approach is extended and further operationalized in the present article.

This article contributes to improving our knowledge of how policy-makers understand the logic of intervention of smart specialization policy, and how this is reflected in the monitoring mechanisms. To the best of our knowledge, only the contribution by Kroll (Citation2015) analyses survey data on the implementation of RIS3, but with no specific focus on monitoring. The present study extends the existing theory and practice on territorial innovation and development policy and smart specialization in two directions. First, it proposes an original conceptual systematization of the inner logic of intervention of RIS3, thereby filling a gap in the literature and the European regulatory provisions on this topic. Second, it provides the first pan-European evidence on both the structure of monitoring mechanisms, and the process that led to their definition.

To capture the multifaceted nature of monitoring activities, we collected and analysed information on how regional and national policy-makers in charge of innovation strategies for smart specialization perceive the constituent elements and functions of monitoring. The survey reveals that policy-makers generally consider monitoring activities as an important channel for transmitting information between public bodies and stakeholders to support effective trust building and long-term mutual commitment to strategy implementation and revision. This is in line with the principles of smart specialization. It also reveals a dual response pattern depending on the government level involved in the strategy. Most regional policy-makers seem to have incorporated the smart specialization logic of intervention, and put into practice a priority-specific approach, whereas national respondents have a more general, less priority-specific focus. However, when it comes to the operationalization of policy interventions, a complete application of the intervention logic appears to be still lacking at both government levels. While the evidence we collected is encouraging for European policy-makers promoting and funding smart specialization policies, we believe at the same time that it calls for more attention to the design of monitoring approaches that follow meaningfully the progress of policy implementation in relation to the desired outcomes and strategic objectives. We need a better understanding of the different roles played by distinct strategic planning levels.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature and provides a conceptualization of the logic of intervention of RIS3; Section 3 presents the survey methodology and results and Section 4 concludes with a discussion of the main findings and policy implications.

2. Theoretical background

In the literature, we find three different purposes policy monitoring may have: (1) learning about actual transformation processes and informing policy responses accordingly (Floc’hlay & Plottu, Citation1998); (2) building and reinforcing trust and cooperation with and among stakeholders and citizens (Gianelle & Kleibrink, Citation2015; Saltelli, Citation2007) and (3) ensuring accountability of policy-makers and project managers (Hanberger, Citation2011; Magro & Wilson, Citation2015). Monitoring systems serve these purposes by performing three main functions: gathering information and making it available to decision-makers; clarifying the purpose and functioning of innovation and development strategies and making these comprehensible to the broader public; and supporting the constructive involvement and participation of stakeholders through transparent channels.

Interestingly, accountability is most often at the core of monitoring and evaluation, usually as a legal obligation. While ‘audit per se is a badge of legitimacy’, it may in fact be a superficial exercise impeding transparency towards the world outside the audited organization (Power, Citation2000, pp. 116–117). In the context of EU funding, audit requirements have ensured that programme and project managers were accountable for their activities. Criticisms that excessive and rigid audit requirements focused mainly on compliance may stifle innovation in EU regional development programmes have been levelled on several occasions (Mendez & Bachtler, Citation2011); audit obligations overburden regional administrations, promote too many risk-averse project applications and in the worst case can scare off promising applicants. To give another example, Altman (Citation1979) developed the idea of ‘performance monitoring’ as a response to the huge increase in funding for social projects in the 1960s US American Great Society programme. Ensuring public money was spent well was a difficult task for local and state administrations which lacked the necessary resources and skills. It is curious that most of the academic literature on public administration, which uses the term ‘monitoring’, indeed originates from audit exercises.

Studies of public management have taken up and reinforced this idea by introducing detailed indicator systems for auditing and inspecting the performance of public administrations aimed at making them more efficient and effective (Barzelay, Citation1997; Leeuw & Furubo, Citation2008, pp. 161–162). In policy studies, monitoring usually is associated with related sanctioning or enforcement mechanisms (Sabatier, Citation2007). Both strands of the literature point to how monitoring insights translate into new decisions and adjustments. How governments learn from past failures and successes is important. In order to move towards more reflexive forms of governance, monitoring systems ought to ensure that ‘complete knowledge and maximization of control are replaced by continuous learning’ (Mierlo, Arkesteijn, & Leeuwis, Citation2010, p. 145). Considering the recent EU Cohesion policy developments, most analysts would agree that the new smart specialization approach requires ‘a better and leaner monitoring of performance’ (Farole, Rodríguez-Pose, & Storper, Citation2011, p. 1108).

Policy learning and trust building through monitoring have received scarce attention in both the literature and in practice. Learning can be undermined if monitoring is seen mainly as fulfilling an audit or control function; this interpretation can even be a barrier to trust building and cooperation (Hummelbrunner, Citation2006, p. 178). Using statistics to benchmark performance against other structurally similar territories is a necessary, but not sufficient precondition for policy learning (Navarro et al., Citation2014). Studies of ‘learning regions’ highlight that regions in a globalized and knowledge-intensive economy have to transition from being places of mass manufacturing to being places of ‘continuous improvement, new ideas, knowledge creation and organizational learning’ by creating inter-related physical, human and communication infrastructures (Florida, Citation1995, p. 532). Learning is an integral part of this concept, albeit with a focus on endogenously managing the relations of embedded organizations in local economies.

Participation and empowerment studies conducted in the 1990s stress the need to actively engage relevant stakeholders and ‘reflective practitioners’ in ‘communities of learners’ (Fetterman, Citation2000, p. 9; Floc’hlay & Plottu, Citation1998; Plottu & Plottu, Citation2009). Coupled with the increasing attention paid to evidence-based policy-making in that period, scholarship on monitoring moved towards broader and more systemic approaches that seek to capture, in a more holistic way, the implementation of policies and their outcomes (Mierlo et al., Citation2010). Such approaches acknowledge the complex nature of innovation systems and the difficulties involved in measuring their performance using single indicators (Borras, Citation2012). The ‘Oxford Dictionary’ defines an indicator as ‘a sign that shows you what something is like or how a situation is changing’. Indicators can be derived from official statistics, but they can emerge equally from interactions with stakeholders with an intimate, often tacit knowledge of how the situation is changing on the ground (Sabel, Citation1995).

It is not sufficient to solely resort to traditional indicators based on official statistics to promote learning. Rather, feedback from stakeholders can provide external validation of the collected data (Plottu & Plottu, Citation2009, p. 346). Indeed, in this role, governments engage in an iterative process of what Sabel (Citation1993, p. 30) calls learning-by-monitoring, in which the ‘state instigates the firms to set goals with reference to some prevailing standard so that shortfalls in performance are apparent to those with the incentives and capacity to remedy them – the firms themselves – and new targets are set accordingly’. Sabel’s notion of learning-by-monitoring echoes the premises of the learning regions approach, in that continuous improvement and organizational learning improve performance. In turn, if organizations implementing innovation measures have a degree of ownership in the setting up of monitoring, this makes the building of trust in the policy-makers more likely.

Regional development policies are particularly difficult to monitor, since they cover many different aspects such as innovation and competitiveness, linking various socio-economic factors and actors with unpredictable behaviour (Hummelbrunner, Citation2006). Another challenge for monitoring is the lack of regionalized data and the high costs of acquiring them (Gianelle & Kleibrink, Citation2015).

In the current EU Cohesion policy, the fact that comprehensive monitoring across various funding streams is legally required in smart specialization strategies sets the bar to meaningful monitoring even higher. Guidelines issued by the European Commission in the 1990s as part of experimental projects fostering a strategic planning culture implicitly recommended systematic monitoring and evaluation. However, very few regions embraced this approach in their pilot exercises (Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, Jiménez-Sáez, & Castro-Martínez, Citation2008). Since audit and financial controls have so far dominated monitoring activities, this raises the question of how monitoring RIS3 can become a tool for driving policy learning and steering policy implementation by measuring strategy performance. Audits are meant to ensure the legal and appropriate use of the public funding. Smart specialization, on the other hand, is about experimenting with new approaches to strategy making and implementation that go beyond mere ‘numbers games’ (Mintzberg, Citation1994, p. 85). For instance, Austrian policy-makers believe that purely control-oriented monitoring for audit is ‘strangling innovation’ in EU-funded regional development projects (Bachtler & Mendez, Citation2011, p. 758). More generally, auditors have been concerned mainly with ‘doing things right [and not] doing the right things’ (Öhman, Häckner, Jansson, & Tschudi, Citation2006, p. 89). In order to avoid such unintended consequences, those policy-makers designing monitoring mechanisms should focus more on learning and stakeholder communication.

Few studies provide a detailed account of the constituents, structure and models for mechanisms to monitor policy implementation. What exactly should be monitored and how? To address this question, we need first to identify the conceptual building blocks of the policy strategy and understand how they are causally and logically interlinked. Monitoring can be only understood based on its fundamental relationship with the strategy’s structure.

Based on the provisions contained in the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) regulation (European Parliament and Council, Citation2013) and the official guidance on smart specialization issued by the European Commission (European Commission, Citation2012), we derive a prototypical structure of RIS3 and an associated operational definition of monitoring (Gianelle & Kleibrink, Citation2015).

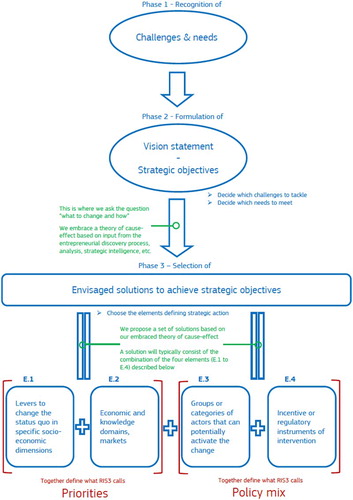

depicts the three stylized phases in any strategic approach: detection of needs, challenges and problems (Phase 1); decision about the desired transformations and their reframing in terms of strategic objectives (Phase 2) and definition of the responses and formulation of solutions for selected objectives and problems (Phase 3).

Figure 1. The logic of intervention in innovation strategies for smart specialization. Source: Gianelle and Kleibrink (Citation2015, p. 6).

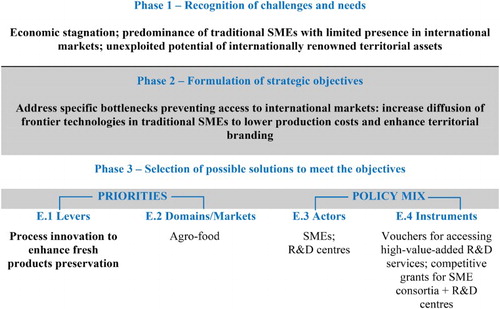

In the context of smart specialization, the community of citizens and social and economic actors expresses their needs and challenges. The strategic objectives are the major desired and expected changes to the region or country’s socio-economic system, which ultimately are endorsed by political authorities. The responses aimed at achieving strategic objectives can be seen as operational solutions consisting of specific combinations of four elements: (E.1) levers to change the existing state of affairs in specific socio-economic dimensions; (E.2) target markets, economic or knowledge domains, or more traditional sectors; (E.3) groups or categories of subjects that can potentially activate the change and (E.4) economic or regulatory instruments of intervention (see for an illustration).

Figure 2. An illustration of the logic of intervention in agro-food. Source: Gianelle and Kleibrink (Citation2015, p. 7).

We will focus on the progression from Phase 2 to Phase 3, where the RIS3 moves from general to specific. It is necessary first to choose and then to apply a specific theory of cause–effect that matches the desired goals with the specific solutions. This consists of assuming a causal mechanism derived based on stakeholder contributions, general experience and analysis. In the context of smart specialization, this assumption may emerge naturally in the ‘entrepreneurial discovery process’, with the support of analysis, relevant scientific literature and strategic intelligence (Foray, Citation2015). The strategy designer must ensure that the causal mechanism is understood and explained.

The first element of a strategic solution is a (set of) lever(s) to be activated in order to modify the existing way of conducting processes for the production of goods and services, organizational procedures and inter-organizational relationships. A ‘lever’ denotes a specific means or agency for achieving an end. It is usually represented by a category of actions performed by social and economic actors. It may be framed as a technological trajectory, an aspect of the production process or a type of inter-actor relationship. The second element of a strategic solution is a (set of) economic area(s) that define the perimeter to the applicability of the levers.

According to this interpretation, determining the specific matches between levers (E.1) and target economic areas (E.2) gives rise to what in RIS3 is referred to as a set of priorities. In RIS3 documents, these matches can be made more or less explicit; however, in identifying priorities, the strategy designer must consider both the types of levers to be activated and the domains/market segments in which they will be applied.

The characterization of RIS3 priorities makes it possible to determine the nature and scope of the desired and realistically achievable change aspired to in a given socio-economic dimension. In a strategic context, this is usually described as an ‘expected change’. A mix of policy instruments (E.4) targeted at a specific group of actors (E.3) can then be chosen in order to contribute to the defined expected change.

Explicitly identifying expected changes is equivalent to setting specific objectives for the RIS3 and is hence a fundamental element of the monitoring system. Variables capturing the expected changes are ‘result indicators’ (European Commission, Citation2014). Having chosen the result indicators, it is essential to identify baseline and target values. Only in this way it is possible to appreciate whether a change is materializing (baseline vs. actual value), and whether this change is in the desired direction and proceeding at the desired pace (actual value vs. target value).

The choice of instruments (E.4) used to produce the expected change allows the identification of the output of the policy action. This output and its generative process can be captured by an ‘output indicator’ defined as an exactly measurable variable that quantifies the extent to which the actions enabled by the instrument reach the target population.

A problem related to the definition of monitoring indicators is that governments in modern states have become accustomed to using ‘standardized characteristics that will be easiest to monitor, count, assess, and manage’ (Scott, Citation1999, pp. 81–82). In the case of innovation policy, standards manuals, such as the Oslo and Frascati manuals, have become the main reference works for measuring all aspects of innovation support and its outcomes. While this has obvious advantages for establishing comparative databases and benchmarking, it causes lock-in and reduced use of novel indicators or adaptations to existing ones. Similarly, resorting to widely used indicators often results in the cart going before the horse: already established indicators are taken as the default and everything is construed around them, rather than thinking backwards starting with strategic objectives and desired outcomes and only then moving to policy outputs and inputs required (i.e. outlining the logic of intervention).

However, for monitoring smart specialization, the key is to track developments of the prioritized activities, their relative growth and the associated structural changes in the regional economic structure, as well as the dynamics within each of them. For instance, if a region prioritizes particular elements of health and e-health, a good monitoring system should be able to show the annual development of this activity area in terms of scientific and commercial performance, organizational development of firms and research organizations and so on.

According to the logic of intervention we have described, RIS3 monitoring systems should exhibit the following characteristics: (1) identification of result indicators; (2) identification of output indicators; (3) definition of the linkage between result and output indicators on one side, and between these indicators and strategy objectives, expected changes and priority areas on the other and (4) involvement of stakeholders in the development of the monitoring system.

3. Survey methodology and findings

Based on the conceptualization in the previous section, we developed a survey for European regional and national policy-makers involved in RIS3 structured around the following six dimensions: (1) the state of development of the monitoring system; (2) the main functions fulfilled by monitoring; (3) the channels for disseminating monitoring results; (4) the presence of and relationships among the RIS3 conceptual building blocks; (5) the sources of information and methodologies employed to monitor the RIS3 and (6) the degree of stakeholder involvement. We surveyed 436 policy-makers between May and June 2015. We obtained 96 complete responses, 80 from regional policy-makers representing 68 regions, and 16 from national policy-makers representing 12 countries in Europe, corresponding to a total response rate of 22%. EU member states are well represented by a large part of the respondents (23 of the 28 Member States). Only Luxemburg, Ireland, Cyprus, Croatia and Latvia are not in the sample. The countries with most observations are also those that are to some degree decentralized and have many regions implementing RIS3: 14 responses come from Italy, 10 from Poland and 9 from Spain. Controlling for selection bias is possible by comparing the extent to which the group of survey respondents differs from the overall population of cases. When comparing how many respondents work for more or less developed regions, we find no systematic or strong bias (see ). More developed regions are slightly over-represented and transition regions to some extent under-represented among respondents, but otherwise our sample corresponds mostly to the distribution of regions in Europe in terms of GDP per capita. The response bias in favour of more developed regions can be explained by their inherent higher propensity and capacity to interact with external institutions, to answer surveys and to provide information; in other words, their stronger administrative capacity should make them more likely to respond. Most surveys of policy-makers are prone to this kind of response bias.

Table 1. Comparison of respondent sample with all NUTS 2 regions by GDP levels.

3.1. Monitoring smart specialization is work in progress

We administered the survey at a moment in time when most monitoring mechanisms are under development. Around 59% of respondents stated that the monitoring mechanism was not completely defined; 15% stated that the mechanism was defined, but not yet operational. This allowed us to gather very timely information on current deliberations within government institutions unlike surveys that ask for information on past events, which are prone to different kinds of bias. A downside of our timeliness is that RIS3 monitoring mechanisms are moving targets. Thus, readers should interpret the results with some caution since they reflect the agenda-setting phase identifying what the relevant issues are and who is important for monitoring RIS3.

3.2. The troubled transition from pure financial monitoring towards novel approaches

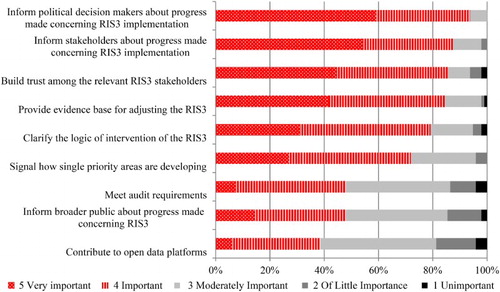

The results summarized in show that policy-makers believe that informing policy and politics about progress in strategy implementation is the single most important function of a monitoring mechanism. More than 93% of respondents consider this function to be important or very important. Similarly, 87% of respondents rank the information-providing role of monitoring mechanisms for stakeholders as important or very important.

Figure 3. Perception of policy-makers on the main functions fulfilled by monitoring. Source: Own elaboration. Respondents were asked to state how much they think these monitoring functions are important for RIS3.

Overall, more than 71% of respondents assign great importance to the functions related to information provision, adjustment and revision of strategy. The literature suggests that this necessitates a clear shift from pure financial monitoring at the programme level to monitoring the outcomes of a territorial innovation policy and assessing their impact on the economy and on society as a whole. This poses additional methodological and analytical challenges: monitoring an overall innovation policy as required by RIS3 may not be achievable through conventional approaches using mainly established statistical sources because these sources cannot fulfil the task of providing an instantaneous picture of the status of strategy implementation, nor can they readily depict emerging innovation domains or relational aspects of the evolution of innovation networks.

It is interesting that policy-makers are already seeing RIS3 monitoring as an exercise that goes beyond a narrow focus on meeting audit requirements; only seven respondents believe that meeting audit requirements is one of the foremost important functions of monitoring. In fact, second to being a management tool, RIS3 monitoring is seen as a communication instrument (the survey allowed for multiple answers). More specifically, monitoring is not regarded as a potential external communication tool towards the broader public, but rather as a means to reach out to stakeholders directly involved in implementing the policy in order to build or reinforce trust with public authorities (85% of respondents consider this function important or very important). This result is in line with previous empirical findings showing how smart specialization helped regional authorities to internalize the principle of participatory policy-making (Kroll, Citation2015).

During the multi-annual EU budgeting period 2007–2013, policy-makers in charge of structural funds were more focused on absorbing as much of the available funding as possible, rather than on monitoring the results and the impact on the economy and society (Barca, Citation2009). The current challenge is how to go beyond the mandatory financial monitoring to control the use of public funding and move towards strategic performance monitoring.

3.3. Transparent policy communication, but how?

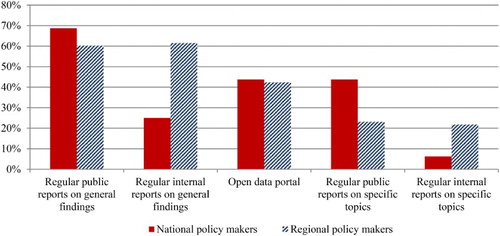

shows that reports on general findings of strategy monitoring are the main dissemination channels, according to around 69% of national and 62% of regional respondents. The preference for communicating general rather than specific findings confirms the perception of policy-makers’ preference for a transversal approach to monitoring; the related communication is considered as a whole with no distinction between RIS3 priorities.

Figure 4. The dissemination channels of monitoring results according to national and regional policy-makers. Source: Own elaboration. Respondents were asked how RIS3 monitoring data will be disseminated. Multiple choices were allowed.

There is a notable difference related to the role of reports on specific monitoring findings; these are seen as a relevant communication channel by 43% of national policy-makers, but at the regional level they are considered important only by about a quarter of the respondents. A second and even more striking difference relates to the different roles of internal and public reports. Internal reports are important at the regional level (61% of respondents), but less so at the national level (25%). More innovative dissemination channels such as open data portals are the third most frequent channel (44% of national respondents and 42% of regional respondents).

3.4. Logic of intervention in practice

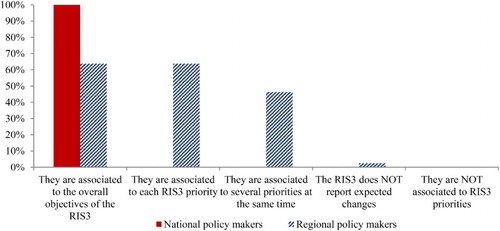

Policy-makers were asked to indicate the statement that best described the relationship between expected changes and the different elements of the RIS3 (). Here, national and regional respondents again show a diverging pattern. At the regional level, the majority of respondents (64%) report a direct link between the expected changes identified in the strategy and each of the RIS3 priorities. This result is consistent with an intervention logic that is highly priority specific, which accords with the smart specialization approach. At the national level, respondents related expected changes only to overall RIS3 objectives, showing that national RIS3 are mostly not priority specific.

Figure 5. Perception of policy-makers on the association of expected changes and the RIS3. Source: Own elaboration. Respondents were asked which of these statements best describe how expected changes relate to the different elements of RIS3. Multiple choices were allowed.

Such differences suggest a distinction among roles and focus in national and regional RIS3, with national strategies acting as the overarching strategic framework focused on progress in the achievement of comprehensive socio-economic objectives, and regional strategies being more similar to operational tools used to identify current and future specialization areas and priorities and monitor their evolution.

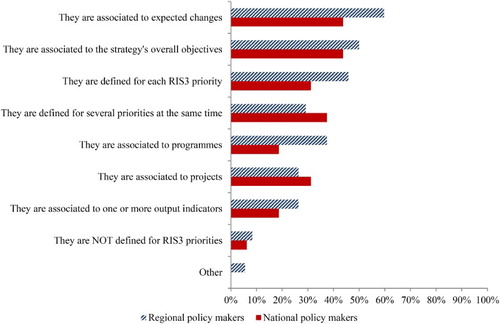

When asked to define the role of result indicators (), regional policy-makers were fairly consistent on the logic of intervention, with 60% of respondents linking result indicators to the expected changes identified in the strategy, in line with the conceptualization of the RIS3 structure described in Section 2. Most of these respondents (75%) also indicated that result indicators were associated with individual or collective RIS3 priorities, demonstrating substantial adherence to a priority-specific approach.

Figure 6. Perception of policy-makers about the role of result indicators in their RIS3 monitoring. Source: Own elaboration. Respondents were asked which of these statements best describe how result indicators relate to the different elements of the RIS3. Multiple choices were allowed.

Result indicators were associated with the strategy’s overall objectives by 50% of regional respondents, 55% of whom also associated result indicators with expected changes, revealing a capacity to identify a logical chain of strategic steps from objectives (socio-economic dimensions), to expected changes (desired variation in these dimensions), to indicators (specific variables to measure progress). Overall, 16% of regional policy-makers participating in the survey were aware of the interconnections among the main RIS3 strategic building blocks (strategic objectives, priorities, expected changes and result indicators); out of which 7% extend this logic to output indicators.

At the national level, applying and understanding the RIS3 intervention logic appear less clear-cut. Only around 44% of respondents linked result indicators to the expected changes identified in the strategy, while a similar percentage linked indicators to RIS3 priorities; at the regional level, these figures were, respectively, 16 and 6 percentage points higher. Around 45% of national and regional respondents connected result indicators with both expected changes and priorities. Interestingly, at the regional level there is a higher propensity to identify priority-specific result indicators, while at the national level policy-makers often defined the indicators across several priorities.

The ‘last mile’ in monitoring implementation is about defining output indicators related to policy measures, and the establishment of a clear relationship between them and the result indicators representing the socio-economic variables of strategic importance. In the survey, only 26% of regional and 19% of national respondents made an explicit connection between result and output indicators, despite evidence of their understanding and application of the RIS3 logic of intervention. This reveals an important missing link that cannot be explained by the present work on the definition or implementation of monitoring mechanisms. If confirmed, this evidence would point to an incomplete understanding or misinterpretation of the policy logic of intervention that goes beyond the context of smart specialization, and would require the European authorities responsible for territorial development policies to pay attention to these aspects.

3.5. Monitoring and follow-up: an organizational challenge

Since RIS3 includes several programmes and sources of funding at the regional, national and European levels, the challenge related to RIS3 monitoring is to gather quantitative and qualitative information from a variety of sources. In most cases, the authorities responsible for managing operational programmes will be responsible for the implementation and monitoring of ERDF projects; other public bodies are responsible for monitoring participation in programmes such as Horizon 2020. This points to two central issues related to RIS3 monitoring: (1) teams in charge of RIS3 monitoring must abandon ‘silo thinking and acting’ and connect with organizations monitoring other programmes and (2) in terms of human resources, the challenge will be to develop new approaches to monitoring which combine quantitative and qualitative aspects. This will require the development of new skills to create the capacity to work with new types of indicators based on less conventional sources. Recruiting staff with the appropriate skills to undertake a form of meta-monitoring across funding programmes will be crucial.

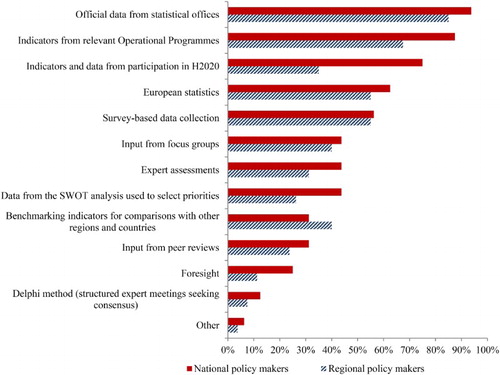

In a setting where multiple choices were allowed, the results reported in show that the sources of information feeding monitoring mechanisms stem mainly from national and regional statistical offices (according to 94% of national and 85% of regional respondents), and from Eurostat (according to 63% of national and 55% of regional respondents). These ‘official’ sources have the advantage that they are reliable, but suffer from a major drawback: the publication of indicators is often delayed because they require multiple verifications. Recent developments like using novel data analytics or more participatory methods to gather relevant information do not yet constitute a large part of the practice of innovation policy-makers.

Figure 7. The main sources of information and methodologies employed to monitor the RIS3 according to national and regional policy-makers. Source: Own elaboration. Respondents were asked to choose among sources of data and methodologies used for the monitoring of their respective RIS3.

In principle, indicators related to programme implementation (ERDF, Horizon 2020) are relevant because they reflect early signals indicating either the rate of absorption of ESIF by stakeholders, or their capacity to acquire funding through competitive calls such as Horizon 2020. At a later point in the policy cycle, a weak funding absorption rate would imply either a drastic change in the RIS3 in terms of specialization domains or the implementation of additional policy measures in order to stimulate the community of potential beneficiaries. This sort of information may need to be enriched by sectoral and thematic components, which are not always covered by traditional programme indicators. In practice, our survey reveals that both national (88%) and regional (68%) policy-makers rely heavily on data from relevant ESIF operational programmes.

Data on participation in the Horizon 2020 programme are important at the national level (75% of respondents), but less so at the regional level (35% of respondents). The lack of access to suitable data may hamper the monitoring of RIS3 at the regional level. Despite the existence of regional data on the organizations involved in Horizon 2020 projects, there is frequently no breakdown of data for the regional level. In part, this can be explained by the fact that the European Commission usually provides information related to contracts signed by project participants only to a limited number of national authority personnel. These individuals are subject to confidentiality agreements, which explains their reluctance to communicate information to regional authorities. This situation is the likely cause of the observed gap between national and regional policy-makers in our survey. Part of the problem surely is also lacking awareness at the regional level. For instance, the European Open Data Portal includes machine-readable files with data on the past four framework programmes for research and technological development since 1994 freely available; while access to this kind of data is not any longer an obstacle, the challenge to regionalize the data remains. Building basic data analytics skills in the regional public sector could remedy this shortcoming.

Most national and regional policy-makers consider acquiring tailored and original information through surveys. It is partly surprising to see that surveys are the most important method to gather evidence from stakeholders. One of the main downsides of surveys is their cost in terms of both time and financial resources. Targeted surveys need substantial preparation and should not overburden stakeholders. Despite the existence of many other methods that are potentially more economical (web scraping and data analytics, focus groups, etc.), surveys remain the gold standard for gathering original data. Expert assessments and analyses of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) are more important at the national level, while regions seem to favour benchmarking indicators. One would expect that SWOT analyses should be more relevant, since all regions and states had to conduct SWOT analyses in their strategy process as required by the ex ante conditionality enshrined in the ESIF regulation. Especially regional policy-makers do not see it as worthwhile to build on this existing body of knowledge by expanding their strategies’ SWOT studies. Input from peer reviews, foresight exercises and Delphi methodology play a minor role. International organizations such as the OECD and the European Commission have supported the use of peer reviews to allow policy learning across administrations. During the strategy design phase, peer reviews have been a highly demanded service: more than 60 regional and 15 national governments have undergone a peer review to discuss their strategies and implementation challenges. Despite continuous interest, the survey responses imply that the information and knowledge derived from this exercise cannot be easily used for monitoring purposes. Some adjustments may be necessary to allow policy-makers to more easily use peer reviews for monitoring and benchmarking. Similarly, foresight and other participatory methods like Delphi seem to be much less popular than a decade ago.

3.6. Stakeholders and their contribution to the definition of monitoring systems

At the national level, almost one-fifth of respondents stated that the public body that contributed most to the design of the monitoring mechanism is not the same body that designed the overarching strategy. At the regional level, 90% of respondents replied that the same body was responsible for both the design of RIS3 and its monitoring, promising a better alignment and greater coherence. Other actors, such as associations of entrepreneurs and research organizations, were not included in the setting up of monitoring mechanisms at the national level, but are part of the process at the regional level. Generally, regional policy-makers include a high variety of stakeholders, such as citizen and user groups, which are not included at the national level.

A key principle of RIS3 design is its bottom-up approach, which takes account of all stakeholders potentially affected by the strategy, from research and academia, the public sector, companies and non-profit organizations (in short, quadruple helix actors). The focus on the creation of economic value through an entrepreneurial discovery process also considers all relevant stakeholders in the respective territory. For this reason, RIS3 monitoring ought to involve stakeholders and provide them with ownership of the process.

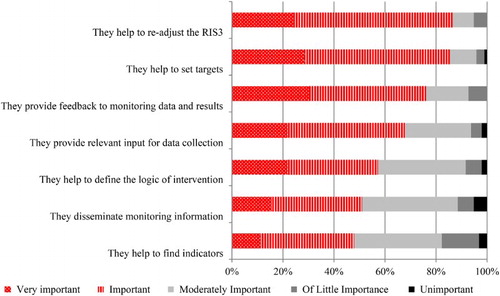

While the types of policy interventions are still under development in most regions, shows that regional and national policy-makers are expecting stakeholders to occupy a strategic role, mainly by contributing to the readjustment of RIS3 and the definition of targets (more than 85% of respondents see these roles as ‘important’ or ‘very important’). Interestingly, only 48% of policy-makers think that stakeholders should contribute substantially to the prior selection of indicators. This might suggest a tension between stakeholder expectations about a meaningful contribution at each stage of the monitoring process, and public bodies that see their role to be mainly at the end of this process. If stakeholders disagree over the initial choice of indicators and do not have ownership in that decision, they are unlikely to be committed to suggesting target values for measuring progress based on what they perceive as the wrong measure. As Mintzberg, an eminent strategy scholar, succinctly put it: ‘if the [strategy’s] objectives truly exist to motivate, then according to behavioural scientists, people have to be involved in the setting of their own ones’ (Citation1994, p. 71). Lack of real ownership is a pertinent threat to successful monitoring. A possible way out of this ‘cul-de-sac’ might be to ask stakeholders to contribute to the interpretation of quantitative indicators. Their involvement in the selection of indicators is an important aspect that determines stakeholders’ perceptions of ownership in the lengthy monitoring process. Our data reveal that policy-makers still do not adequately consider this aspect. Further research is needed to understand whether this is a persistent feature and what the reasons behind these results are.

Figure 8. The role of stakeholders in the monitoring of the RIS3 according to national and regional policy-makers. Source: Own elaboration. Respondents were asked to grade the potential role of stakeholders in the RIS3 monitoring (from unimportant to very important).

Another interesting finding is that stakeholders are not seen as very important for defining the logic of intervention. One can reasonably assume that stakeholders know better than governments what they need to improve their performance. Linking ends to means should then be equally important during the strategy design and implementation phases. After all, the legal requirement foresees that stakeholders actively participate in the search process leading to the strategy document and its underlying intervention logic (Saritas, Pace, & Stalpers, Citation2013).

Stakeholders are not seen as important for disseminating monitoring information. Yet, innovation councils, bodies gathering the most important stakeholders, are often the best-suited organization to disseminate monitoring results and reach out to the wider public.

4. Concluding remarks

How can policy-makers monitor something as complex as strategies for innovation and territorial development? This article provides original evidence on how they understand the monitoring of territorial innovation policies at different levels of government. We shed light on the rationales, content and organizational set-up of monitoring strategy implementation in the highly heterogeneous context of European states and regions. Our findings are based on a survey of almost one hundred policy-makers providing insights into the logic of policy intervention and its building blocks in the context of innovation strategies for smart specialization or RIS3.

Although the majority of respondents declared that work on monitoring systems is still ongoing, some important findings have emerged. First, policy-makers at both the national and regional levels are already seeing strategy monitoring as an exercise that must go beyond a narrow focus on meeting audit requirements. Monitoring innovation strategies for smart specialization is partly seen as a management tool and as an instrument for communication with stakeholders. This would indicate the acceptance of one of the main and most innovative aspects of the smart specialization approach, namely participative and inclusive strategy building. The evidence so far suggests that the theory of smart specialization is relatively well understood, but translating this into practice and completing the process of stakeholder involvement in all phases of strategic management will require further efforts.

The existence of different territorial patterns in the survey responses, with regional policy-makers generally exhibiting closer adherence to the conceptualization of smart specialization strategies, may suggest that the most suitable scale at which such strategies can be achieved is the region or equivalent subnational administrative partition. More evidence and information are needed on the different nature and implementation of national and regional innovation strategies for smart specialization, in order to better understand the different roles played by distinct levels of strategic planning. Future European policies and rules may have to be tailored to different needs and goals at multiple levels of government.

Apart from these findings with relatively clear implications, three more complex ambiguities arise from our observations on the role of stakeholders, monitoring specific priority areas and linking policy outputs with results. First some remarks on stakeholders. Clearly, policy-makers perceive stakeholders and their involvement as important actors in monitoring innovation strategies. However, our findings do not tell us if they assign stakeholders a passive or rather active role beyond the rhetorical reference to collaborative arrangements. Trust, an essential element in the interactions between public authorities and independent firms and research organizations, is created by using monitoring data to inform stakeholders about the progress made in strategy implementation. Policy-makers stress this very much and are less interested in giving stakeholders a more active role in setting up a monitoring system and choosing indicators. From the perspective of stakeholders, however, this may not be fully satisfactory. They may want to feel stronger ownership, since they hold tacit knowledge of what kind of results can be realistically achieved with a given set of outputs. Learning by monitoring, if taken seriously, would require a mutual process in which public authorities more openly engage stakeholders. Conceptually, more research is needed to understand how policy-makers can embed such an engagement in the design and daily practice of monitoring. Preliminary studies from the agricultural sector illustrate how to monitor processes and systems (Mierlo et al., Citation2010).

Second, prioritization and concentration of investments in selected activity areas and sectors are at the very heart of smart specialization. Yet, this is not always fully reflected in the monitoring efforts. A reason for this may be the natural human reflex to resort to standard operating procedures to minimize administrative burden. For EU cohesion policy, this procedure is the standardized approach taken in operational programmes, legally binding documents that set out in which areas public authorities intent to invest in. Since the monitoring of these programmes is highly standardized, many policy-makers see this as the primary source of data for strategy monitoring. However, they lack the needed level of detail to depict developments in prioritized areas and not only across broader sets of the economy. Breaking out of this kind of thinking will very much depend on the availability and accessibility of data and information sources to truly conduct strategy monitoring. Many respondents were rather sceptical of using established methods like peer reviews, foresight or Delphi for gathering monitoring ‘data’. Partly, this may be due to a lack of tailor-made approaches to specifically address monitoring needs during the implementation and not provide scenarios of future developments. Recalibrating foresight approaches to better match the needs of monitoring could yield significant benefits. Foresight has moved beyond relying predominantly on expert contributions to mobilizing wider groups of stakeholders with varying perspectives and interests by facilitating the development of common ‘problem frames’, making use of their local and sectoral knowledge and providing actionable insights for implementation (Coates, Citation1985; Keller, Markmann, & von der Gracht, Citation2015). Inside public administrations, staff training will have to increasingly include data analysis and developing open data solutions to share information across levels of government and with stakeholders. Governments cannot afford to lag behind and ultimately depend solely on private data analysts for ensuring effective and result-oriented policy-making (Dunleavy, Citation2016).

Finally, outputs must be more directly connected to desired results. Although the result-oriented logic of intervention of innovation strategies appears generally to be fairly well understood and applied by policy-makers, only a minority of respondents established a clear link between output and result indicators. Put differently, there is not yet a robust ‘implementation theory’ in place (Weiss, Citation1998). This is revealed by a weak monitoring of the ‘last mile’ of policy implementation, which deserves more attention from public authorities and bodies responsible for supervising European territorial policies.

The prospect of an integrated approach at the regional level, where in most cases the same organizational entity that designed the innovation strategy will also be in charge of monitoring, should be reassuring for European policy-makers promoting and funding smart specialization policies. While entailing some risk of conflicting interests, at the very least this should ensure a coherent implementation and monitoring of strategies. Yet more work will have to be done to meaningfully involve stakeholders throughout implementation, to show the developments within prioritized areas and to ensure the logic of intervention is upheld by showing which ends have been achieved with what kind of means.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ahner, D., & Landabaso, M. (2011). Regional policies in times of austerity. European Review of Industrial Economics and Policy, 2.

- Altman, S. (1979). Performance monitoring systems for public managers. Public Administration Review, 39(1), 31–35. doi:10.2307/3110375

- Bachtler, J., & Mendez, C. (2011). Administrative reform and unintended consequences: An assessment of the EU cohesion policy ‘audit explosion’. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(5), 746–765. doi:10.1080/13501763.2011.586802

- Barca, F. (2009). An agenda for a reformed cohesion policy: A place-based approach to meeting European Union challenges and expectations. Independent Report Prepared at the Request of Danuta Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy.

- Barzelay, M. (1997). Central audit institutions and performance auditing: A comparative analysis of organizational strategies in the OECD. Governance, 10(3), 235–260. doi:10.1111/0952-1895.411997041

- Borras, S. (2012). Three tensions in the governance of science and technology. In D. Levi-Faur (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of governance (pp. 429–440). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Capello, R. (2014). Smart specialisation strategy and the new EU cohesion policy reform: Introductory remarks. Scienze Regionali, 1(1), 5–13. doi:10.3280/SCRE2014-001001

- Coates, J. F. (1985). Foresight in federal government policymaking. Futures Research Quarterly, 1, 29–53.

- Dunleavy, P. (2016). ‘Big data’ and policy learning. In G. Stoker & M. Evans (Eds.), Methods that matter: Social science and evidence-based policymaking. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- European Commission. (2012). Guide to research and innovation strategies for smart specialisation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Commission. (2014). Guidance document on monitoring and evaluation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Court of Auditors. (2007). Special report no 1/2007 concerning the implementation of the mid-term processes on the structural funds 2000-2006 together with the commission’s replies, 2007/C 124/01. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union.

- European Parliament and Council. (2013). Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013 of the European parliament and of the council laying down common provisions on the European regional development fund, the European social fund, the cohesion fund, the European agricultural fund for rural development and the European maritime and fisheries fund and laying down general provisions on the European regional development fund, the European social fund, the cohesion fund and the European maritime and fisheries fund. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union.

- Farole, T., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2011). Cohesion policy in the European union: Growth, geography, institutions. Journal of Common Market Studies, 49(5), 1089–1111. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02161.x

- Fetterman, D. (2000). Foundations of empowerment evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Floc’hlay, B., & Plottu, E. (1998). Democratic evaluation from empowerment evaluation to public decision-making. Evaluation, 4(3), 261–277. doi:10.1177/13563899822208590

- Florida, R. (1995). Toward the learning region. Futures, 27(5), 527–536. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(95)00021-N

- Foray, D. (2015). Smart specialisation: Opportunities and challenges for regional innovation policy. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gianelle, C., & Kleibrink, A. (2015). Monitoring mechanisms for smart specialisation strategies, S3 policy brief series, 13/2015. Spain: European Commission, Joint Research Centre.

- Hanberger, A. (2011). The real functions of evaluation and response systems. Evaluation, 17(4), 327–349. doi:10.1177/1356389011421697

- Hummelbrunner, R. (2006). Systemic evaluation in the field of regional development. In B. Williams & I. Imam (Eds.), Systems concepts in evaluation: An expert anthology (pp. 161–180). Point Reyes, CA: EdgePress of Inverness.

- Keller, J., Markmann, C., & von der Gracht, H. A. (2015). Foresight support systems to facilitate regional innovations: A conceptualization case for a German logistics cluster. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 97, 15–28. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2013.12.031

- Kroll, H. (2015). Efforts to implement smart specialization in practice: Leading unlike horses to the water. European Planning Studies, 23(10), 2079–2098. doi:10.1080/09654313.2014.1003036

- Lasswell, H. D. (1956). The decision process: Seven categories of functional analysis. College Park, MD: Bureau of Governmental Research, College of Business and Public Administration, University of Maryland.

- Leeuw, F. L., & Furubo, J.-E. (2008). Evaluation systems: What are they and why study them? Evaluation, 14(2), 157–169. doi:10.1177/1356389007087537

- Magro, E., & Wilson, J. R. (2015). Evaluating territorial strategies. In J. M. Valdaliso & J. R. Wilson (Eds.), Strategies for shaping territorial competitiveness (pp. 94–110). Oxon: Routledge.

- McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2015). Smart specialization, regional growth and applications to European Union cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1291–1302. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.799769

- Mendez, C., & Bachtler, J. (2011). Administrative reform and unintended consequences: An assessment of the EU cohesion policy ‘audit explosion’. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(5), 746–765. doi:10.1080/13501763.2011.586802

- Mierlo, B. V., Arkesteijn, M., & Leeuwis, C. (2010). Enhancing the reflexivity of system innovation projects with system analyses. American Journal of Evaluation, 31(2), 143–161. doi:10.1177/1098214010366046

- Mintzberg, H. (1994). The rise and fall of strategic planning: Reconceiving roles for planning, plans, Planners. New York, NY: Free Press; Maxwell Macmillan Canada.

- Navarro, M., Gibaja, J. J., Franco, S., Murciego, A., Gianelle, C., Kleibrink, A., & Hegyi, F. B. (2014). Regional benchmarking in the smart specialisation process: Identification of reference regions based on structural similarity, S3 working paper, 03/2014. Spain: European Commission, Joint Research Centre.

- Öhman, P., Häckner, E., Jansson, A.-M., & Tschudi, F. (2006). Swedish auditors’ view of auditing: Doing things right versus doing the right things. European Accounting Review, 15(1), 89–114. doi:10.1080/09638180500510475

- Plottu, B., & Plottu, E. (2009). Approaches to participation in evaluation: Some conditions for implementation. Evaluation, 15(3), 343–359. doi:10.1177/1356389009106357

- Power, M. (2000). The audit society: Second thoughts. International Journal of Auditing, 4(1), 111–119. doi:10.1111/1099-1123.00306

- Sabatier, P. A. (Ed.). (2007). Theories of the policy process. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Sabel, C. F. (1993). Learning by monitoring: The institutions of economic development (Working Paper No. 102). New York, NY: Center for Law and Economic Studies, Columbia University School of Law.

- Sabel, C. F. (1995). Intelligible differences: On deliberate strategy and the exploration of possibility in economic life. Paper presented at the 36th Annual Meeting of the Società Italiana degli Economisti, Florence.

- Saltelli, A. (2007). Composite indicators between analysis and advocacy. Social Indicators Research, 81(1), 65–77. doi:10.1007/s11205-006-0024-9

- Saritas, O., Pace, L. A., & Stalpers, S. I. P. (2013). Stakeholder participation and dialogue in foresight. In K. Borch, S. M. Dingli, & M. S. Jorgensen (Eds.), Participation and interaction in foresight: Dialogue, dissemination and visions (pp. 35–69). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Scott, J. C. (1999). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Weiss, C. H. (1998). Evaluation: Methods for studying programs and policies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J. M., Jiménez-Sáez, F., & Castro-Martínez, E. (2008). Evaluating European regional innovation strategies. European Planning Studies, 16(8), 1145–1160. doi:10.1080/09654310802315849