ABSTRACT

In this article we explore the effects of two Slovenian jazz festivals on the economic resilience of the host cities: Jazzinty Novo Mesto and Jazz Cerkno. We analyse to what extent the two jazz festivals contribute to the original pre-crisis status (e.g. static economic resilience) of the two host cities as reaction to the financial crisis of 2008. Using a monthly based dataset of Statistical Office of Republic of Slovenia, covering the period 2008–2015, and ex-post econometric verification methodology (time series and panel data methods), we estimate the effects of these festivals on tourism inflows and employment. The results confirm important effects of the events in both cities, but with wide variation across the years, being more present in the earlier years of the festivals, and being on a very different scale for both cities.

1. Introduction

Within the broad spectrum of ‘music festivals’, jazz festivals occupy a significant role. In recent decades, this genre became a widespread phenomenon: the number of large and small jazz festivals has been intensively growing across Europe.Footnote1 Several studies (i.e. Allen, O’Toole, Harris, & McDonnell, Citation2011; Andersson, Getz, & Mykletun, Citation2013; Riley & Laine, Citation2006) proved the viability and prospects of jazz festivals in their social, economic and cultural dimensions. Besides the social and economic values generated by any festival, jazz festival specificity is represented by its function to preserve and transmit jazz heritage, intercultural exchange between different national jazz cultures, where festivals expand the jazz target audience, and foster demand for live music (Hiller, Citation2016). Moreover, festivals generate a sense of community and festive atmosphere; they imply a social ritual for gathering people around a special event (Goldblatt, Citation1997). Jazz festivals like other types of festival become a creative destination (Prentice & Andersen, Citation2003) and have experienced a boom phase (Frey, Citation2000).

Over time, the relationship between festivals and tourism becomes stronger. Music festivals as with all cultural festivals represent a core topic of tourism marketing: ‘The arts create attractions for tourism and tourism supplies extra audiences for the arts’ (Myerscough, Citation1998, p. 80). These events are tourist attractions and generate tourist flows (i.e. Getz, Citation2010; Quinn, Citation2006). Arguably, their survival and transmission are based on the ability to create links between endogenous resources and exogenous forces (Quinn, Citation2005).

There are very few studies dealing with the economic impact of small events. Our study wants to fill in this gap in the existing literature. Specifically, we explore the effects of Jazzinty Novo Mesto and Jazz Cerkno jazz festivals on the economic resilience of the host cities as a combination of two reactions towards the financial crisis of 2008: the ability of a regional economy to withstand external pressures; and its capacity to respond positively to external change. Established in different years, these festivals take place in small-sized cities, quite far from the Slovenian capital, Ljubljana. Due to the size of the host cities and remoteness from Ljubljana, the festivals serve as important stimulators for the economic and social environment of those small cities, providing them a ‘buffer’ against unexpected shocks and a source of sustainable growth towards the challenges of the post-industrial economy. Using the Statistical Office of Republic of Slovenia (SORS) dataset (municipality level data), we estimate the effects of the festivals on tourism inflows and on the local economy and, by this, the ability of a local economy to withstand external pressures represented by the financial crisis in economic terms. Slovenia was one of the most affected countries by the financial crisis in Europe (Verbič et al., Citation2016). To this end, we use an ex-post econometric verification approach (using time series intervention analysis), originating in sport economics and being seldom used in cultural economics (see e.g. Skinner, Citation2006; Srakar & Vecco, Citationin press). This enables us to estimate the effects of the festivals for the two Slovenian smaller cities (at least compared to European cities), enhancing the economic resilience of the local environment. Therefore, our main research question, is: To what extent the two jazz festivals (Novo Mesto and Cerkno) contribute to the economic resilience of the two host cities as reaction to the financial crisis of 2008 respectively?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Following this introduction, the second section presents a literature review on the concepts of jazz festival and economic resilience to contextualize the present research. In the third section, the two jazz festivals are introduced with their main socio-demographic characteristics. The fourth section introduces the methods and the analysis of the economic effects of these festivals on tourism inflows and employment. Finally, after the discussion of the main findings, some concluding remarks on the economic enhancement of these two jazz festivals on the local economy are proposed in the sixth section.

2. Jazz festivals and economic resilience

2.1. Jazz festivals

A music festival is a ‘product bundling’ (Choi, Citation2003) as in an addition to the art itself: in its frame there is a significant role of place, geography and environment, the way the festival is organized and presented, its attractiveness for tourists, etc. Moreover, a music festival possesses unity of time, place and action, gathering a specific target audience towards which the artistic concept is addressed. Festivals act as intermediaries between producers and consumers of ‘aural goods’ (Paleo & Wijnberg, Citation2006, p. 50). A variety of festival impacts have been discussed academically.

Several scholars (Clifton, O’Sullivan, & Pickernell, Citation2012; Crespi-Vallbona & Richards, Citation2007; O’Sullivan, Pickernell, & Senyard, Citation2009; Robertson, Rogers, & Leask, Citation2009; Van Winkle & Woosnam, Citation2014; Williams & Bowdin, Citation2007) investigated the contribution of festivals in city development or regional development as a touristic attraction tool, city imaging, its marketing and the impact upon local community. Getz (Citation2010), in his large-scale literature review of 423 academic articles, identifies the most commonly acknowledged festivals’ positive impacts: economic, social, cultural, personal impact, urban renewal, development and environmental impacts. Despite the relevance of jazz festivals, some scholars identified a loss of festival social significance for the local inhabitants as the clear values shift towards the economic utility dimension became more evident (Okech, Citation2011; Quinn, Citation2006; Richards & Wilson, Citation2004). However, cultural policy makers are convinced that festivals may contribute to the city’s image betterment, create place distinctiveness and draw visitors and tourists – all in order to generate economic benefits (Frey, Citation2000; Quinn, Citation2013; Schuster, Citation1995). Much research has been done on the role that festivals play in economic development. Invariably, they are expected to foster the cosmopolitan dimension of the city (i.e. Waitt, Citation2008) and a positive image as a destination (Getz & Andersson, Citation2008; Quinn, Citation2005).

The importance of acknowledging jazz festivals’ impacts is well-documented in the literature. Nonetheless, evaluative research has, until very recently, adopted predominantly the economic impact approach (Bracalente et al., Citation2011; Brown, Var, & Lee, Citation2002; Riley & Laine, Citation2006; Saayman & Rossouw, Citation2010, Citation2011). In most instances, an estimate of an aggregate measure of income and employment change attributable to the festival is used. This approach and the regional economic models to which it is related were originally developed to explain the effects of exogenous changes in demand on an area’s economy, and in particular, to explain the growth effects of increased spending upon a region’s exports (e.g. Hunter, Citation1989; Krikelas, Citation1992). Constantly, the results are positive and are then used to make the demand for public support for the festival stronger using the evidence-base. However, this approach reveals some limitations as it misinterprets the benefits of arts and cultural organizations (Seaman, Citation2000; Sterngold, Citation2004) and the analysis finishes ‘prematurely with the estimation of local multiplier effects but without progressing one stage further and illustrating how these translate into local economic growth’ (Okech, Citation2011, p. 187). Additionally, some key factors responsible for the inaccuracy of direct expenditure forecasts have been identified (Ramchandani & Coleman, Citation2012).

2.2. The economic resilience

The concept of resilience is not new. Its use goes back to the 1960s in physics. In these years, along with the growing importance of systems thinking, resilience entered the field of ecology and become a key concept to define the sustainability or the persistence of a complex ecosystem (Vickers, Citation1995). In this context, the seminal article by Holling (Citation1973) appeared. This scholar proposed the concept of resilient system, described as ‘if it survives shock and disturbances from the internal and/or external environment’ (Holling, Citation1973, p. 15). Since its infancy, multiple meanings of the concept of resilience have emerged, with each being rooted in different scientific traditions and approachesFootnote2 and been repeatedly redefined and extended by heuristic, metaphorical or normative dimensions (among others: Holling, Citation2001; Hughes, Bellwood, Folke, Steneck, & Wilson, Citation2005; Pickett, Cadenasso, & Grove, Citation2004). For some authors (Horne & Orr, Citation1998; Sutcliffe & Vogus, Citation2003) resilience derives from a return to a stable state after a perturbation; Douglas and Wildavsky (Citation1982, p. 196) specifically defined resilience as ‘the capacity to use change to better cope with the unknown: it is learning to bounce back’. Furthermore, Davies (Citation2011) identified three types of reactions: the ability of a regional economy to withstand external pressures, its capacity to respond positively to external change and its long-term adaptability or learning capacity (see e.g. Lazzaretti & Cooke, Citation2015).

According to Perrings (Citation1998), the resilience of a system can be defined according to different perspectives that provides the engineering and ecological resilience, respectively. Engineering resilience is the ability of a system to return to a stable equilibrium or steady-state after a shock or a disturbance in general (Pimm, Citation1984). In this perspective, the resistance to disturbance and the speed by which the system returns to equilibrium is the measure of its resilience. The faster the system recovers, the more resilient it is. Ecological resilience refers to the extent to which a shock can be absorbed by a local stable domain before it is induced into some other stable equilibrium (Holling, Citation1973) and it is measured by the elasticity of the system to react.

What should be pointed out in this context is that the economic resilience can be analysed as engineering resilience, of ecological resilience, or of both kinds of resilience. From a research perspective, the engineering approach has been preferred in the economic field as it can be difficult to identify the new equilibria implied in the concept of ecological resilience.

Among the existing definitions of economic resilience, we decided to use as working definition in this analyse Rose’s one: ‘the ability of an entity or system to maintain function (e.g. continue producing) when shocked’ (Rose, Citation2007, p. 384). Moreover, economic resilience may be distinguished into static economic resilience – as ability of a system to maintain its function when shocked – and dynamic economic resilience as the speedy of a system to recover from a shock to achieve a desired state (Rose, Citation2007). The former deals with a classical economic problem – an efficient allocation of existing resources and is static as it can be realized without repair and reconstruction activities – while the latter refers to the speeding recovery through repair and reconstruction of the critical inputs in terms of capital stock. This dynamic form of economic resilience is more complex as it may imply a long-term investment problem related to the repair and reconstruction. Furthermore, its complexity can increase because of the trade-offs associated to the investment portfolio decisions to recovery and reconstruction of the infrastructures of the economic system.

Despite the classifications and different interpretations provided by the extant literature, we have to bear in mind that economic resilience is just one face of the concept and we need to consider it strictly interconnected with ecological sustainability. Although we can have clear definition of the concept, its operationalization and measurement can be more problematic as the main measure used (productivity measures in terms of economic output for a given period in time) – even if clear and measurable – may not capture not all specific elements of an economy such as relative competitiveness or equity (Rose, Citation2007). We cannot discuss the operationalization of the concept in a standardized way but we need to carefully identify appropriate tools and methodologies according to the variables used to construe the concept of economic resilience. Furthermore, researchers investigating economic resilience have to pay attention as this concept involves more than one dimension and different levels of analysis (microeconomic, mesoeconomic and macroeconomic). This leads to situations in which the whole is not simply the sum of the parts, which cannot be fully captured by a general equilibrium analysis.

The concept of resilience is one of the most relevant research topics in the context of achieving sustainability (Brand & Jax, Citation2007; Foley et al., Citation2005; Perrings, Mäler, Folke, Holling, & Jansson, Citation1995). Some ecologists and ecological economists have linked resilience to the concept of sustainability as long-term survival and non-decreasing quality of life (Common, Citation1995; Perrings, Citation2001). Furthermore, as pointed out by Pickett, McGrath, Cadenasso, and Felson (Citation2014), resilience is a key concept for operationalizing sustainability. Sustainability clusters socially derived goals, embracing social equity, economic viability and ecological integrity (Curwell, Deakin, & Symes, Citation2005; Jenks & Jones, Citation2010), while resilience is a conceptual framework which ‘facilitate or inhibit the achievement of normative sustainability goals’ (Pickett et al., Citation2014, p. 143). Strictly connected to this concept and the topic of this paper is the growing focus on resilient cities (recently, Childers, Pickett, Grove, Ogden, & Whitmer, Citation2014; Desouza & Flanery, Citation2013; Pickett et al., Citation2014). In this stream the concept of resilience provides ‘a new perspective to the issue of sustainability in the sense that resilience is needed for a sustainable environment’ (Cartalis, Citation2014, p. 261).

Recently, some scholars pinpoint the relation between festivals and sustainability (Bormann, Citation2015; Getz & Andersson, Citation2008; Getz, Andersson, & Mykletun, Citation2013). This call to sustainability may be considered as part of a broader research and societal goal (see ICOMOS’ concept note, Citation2016). Although Zifkos (Citation2014) identified three distinctive uses of the concept of sustainable festivals (namely, as the ‘green festival’, as a festival’s ability to be ‘sustained’ – meaning to survive in the sense of endure as an organization, and finally how festival organizations can achieve long-term viability within their community), no specific reference is to how a festival can contribute to the economic resilience of its territory. Festivals in small regional destinations often play an important role in tourism development and thereby in local economic development. They can be considered as good examples of the relocalisation movement, as a strategy to build societies based on the local production of food, energy and goods, and the local development of currency, governance and culture. Relocalisation or sustainable de-growth aims at increasing resilience and well-being in local communities as a response to interrelated social-ecological threats emerging on a global scale (Curtis, Citation2005; Hopkins, Citation2008; Swilling & Annecke, Citation2012; Victor, Citation2008).

In our study, we focus on contribution of the two jazz festivals to the static economic resilience to the two hosting cities. To operationalize the concept of static economic resilience, we use the analysed period (2008–2015) to observe the changes in the levels of tourism and employment, generated by the two festivals, in times of the financial crisis.

3. The two Slovenian jazz festivals

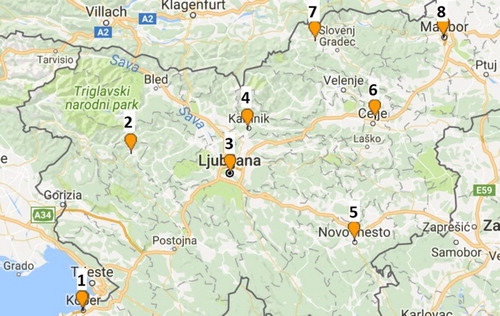

Slovenia has eight jazz festivals which take place in different cities (see ), mostly during the summer period. As tourism attractors, festivals are organized in areas that present some cultural or natural interest. In our specific case, Jazzinty has taken place since the year 2000 in the city of Novo Mesto (one of the largest cities in Slovenia). Jazz Cerkno has taken place in a smaller and more remote city of Cerkno (mainly attractive to visitors due to its ski resort) since 1996. presents the main features of the two festivals.

Figure 1. Locations of Slovenian jazz festivals. Source: Own adaptation on the basis of European jazz network, http://www.europejazz.net/jazz/festivals/si.

Table 1. Main characteristics of Jazzinty and Jazz Cerkno festivals.

The Festival Jazz Cerkno is an annual international music festival organized by the independent (NGO) Jazz Cerkno Institute. Started as a domestic music event squeezed into a small but vivid room in the bar – became an international festival presenting various international high-quality music groups and musicians from a wide variety of music genres. The big break-through in different aspects, organizational, musical and social, came in 2000 when the event moved outdoors and out of town. On the other hand, the Jazzinty Festival is younger in age, but already achieved an acclaimed status in Central and Eastern Europe. Foreign jazz musicians and pedagogues are invited every year to run the workshops and to play at the festival. These jazz events have become one of the main international musical events in the region of Dolenjska.

According to the framework developed by O’Sullivan and Jackson (Citation2002), these jazz festivals cluster in the category of home-grown festivals, where a ‘home-grown’ festival is essentially small scale, bottom-up and run by one or more volunteers for the benefit of the locality.

4. Data and methods

The present section introduces the main variables, their descriptive statistics and the methods used in this analysis. To reply to this study research question, we pay primarily attention to the tourism flows and employment generated, if any, by the selected jazz festivals. To this end, we follow Skinner (Citation2006), and Srakar and Vecco (Citationin press) and adopt a univariate interrupted time series econometric method. This implies the construction of models with the following independent variables: tourist arrivals (total and foreign), tourist overnight stays (total and foreign) and number of employed persons.

Our dataset – including different tourism and employment variables from January 2008 to April 2016 – are compiled from SORS data. shows some descriptive statistics of the key variables included in the time series.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of key variables.

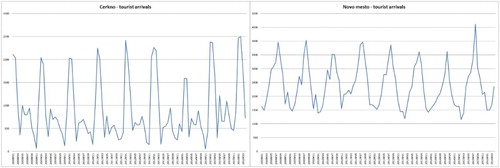

presents the monthly movements in the number of tourist arrivals in Cerkno and Novo Mesto in the analysed period. On the left graph (Cerkno), the top peak is explained by the tourism peak in winter due to its ski resort, while the smaller peak we want to estimate happens in May each year.

Figure 2. Tourist arrivals in Cerkno and novo mesto, monthly data January 2008–March 2016. Source: own calculations on the basis of sors data.

The right graph presents the monthly movements in the number of tourist arrivals in Novo Mesto from January 2008 until March 2016. The top peak which we want to estimate happens in August each year.

Our time series methodology consists of several steps. Dummy variables representing the periods in the months when the two festivals took place (Cerkno – May; Novo Mesto – August) are introduced into the model. As there was insufficient data on crucial explanatory variables to allow estimation of even a single multivariate equation, we could not perform a multi-equation model of impact on tourism and employment would be estimated. We used time series analysis as it can provide ‘a valid estimation methodology applicable to this problem’ (Skinner, Citation2006, p. 115).

There are some other factors besides the festivals that could have an effect on tourism during the observed period, for example, seasonal factors and business cycles. Therefore, a filtered model is estimated to exclude connections with these mentioned factors. Equation (1) presents the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model for monthly filtered number of tourist arrivals. The equations are similar for other dependent filtered variables. The coefficients represent the average number of tourists, overnights or employed persons for each quarter or season of the period. Variables for Slovenia are added to adjust for cyclical effects. The OLS model’s residuals are Cerkno and Novo Mesto tourists, overnights or number of employees, depending on the used dependent variable filtered to seasonal and cyclical effects.(1)

To capture the systematic time relationship in the filtered dependent variables, we perform an interrupted time series analysis. The festivals occur at several points over the period of the time series. The interrupted time series, in general, does not require stationarity of the dependent variable of used in the original (filtered) series. The general form of interrupted time series’ regression model assumes the following form (Huitema & McKean, Citation2000):(2)

Here TA_t is the aggregated outcome variable measured at each equally spaced time-point t, T is the time since the start of the study, X_t is a dummy (indicator) variable representing the intervention (pre-intervention periods 0, otherwise 1), and XT_t is an interaction term. The coefficients of interest will be b2 – the effects of interventions.

5. Results

This section presents the results of the analysis of tourism variables for the two festivals ( and , respectively). As it can be seen, the results for Jazz Cerkno in terms of new tourism were more visible in earlier years of our analysis, namely, in 2008, 2009 and 2010. Interestingly enough, the coefficients on interactions with time are also significant, which means that the effects were not only short term. We can estimate new visitors due to the festival in the period 2008–2010 in the range of 300–1000, of which ca. 200–600 were foreigners. Additionally, we can estimate ca. 1000–5000 additional tourism overnight stays in the period 2008–2010, of which ca. 600–3000 were by foreign tourists. Following the years at the start of the crisis (2008–2010), in next years no effect of the festival on tourism can be observed. This can be attributed to different reasons: one of them surely being the financial crisis, hitting Slovenia with some delay (see e.g. Verbič et al., Citation2016), another one being the festival coming to an older age and saturation of the tourists and a final, related one being the competition of other festivals and events in nearby environment. Nevertheless, in 2014, an additional positive effect can be seen in terms of ca. 400 new visitors and ca. 1500 new overnights stays. Again, this effect seemed to last for a longer time, contributing not only to the short term insertion of new money in the economy, but to the longer term growth and resilience of the area to other possible shocks at that time, confirming that here we are talking about contribution to static resilience, as the system is not using strong renovation and reconstruction to respond to the shocks of financial crisis, but nevertheless maintaining its functions.

Table 3. Results of interrupted time series analysis, tourism, Cerkno.

Table 4. Results of interrupted time series analysis, tourism, Novo Mesto.

As for Cerkno, for Jazzinty Novo Mesto as well, significant results can be mainly identified in years 2008, 2009 and 2010, being followed later only in 2015. The numbers are on a significantly lower scale than those in Cerkno, but have grown by 2015. The lower scale numbers can be attributed to the nature of the event: it is mainly based on the workshop and not so much on the events of the festival. Approximately 100–200 new visitors have come due to the festival of which more than 200 were foreigners. This apparent paradox can clearly be explained by the effect of crowding out – it is possible that foreign visitors have overcrowded the local inhabitants (similar effect was observed in the case of European Capital of Culture Maribor 2012; see Srakar & Vecco, Citationin press). A similar trend can be observed in the number of overnight stays: approximately 1000 new overnight stays, all foreign, happened in 2008 and 2009 due to the festival.

In 2015, a significant rise in the number of new visitors and overnight stays can be noticed in Novo Mesto: ca. 400 new visitors (only half foreign) and ca. 1100 new overnight stays (half of them foreign). Interestingly, again we can observe a crowding out effect visible in the negative level of the coefficient on the interaction term with time trend.

presents the results for the employment variables for both festivals. Similarly as earlier identified, the main effects can be observed for both festivals in years 2008, 2009 and 2010. Later, even negative effects can be noticed, probably to be attributed to some external factors like the financial crisis (although we control for cyclical effects in the starting OLS regression). Similarly, for Cerkno we are able to find strong positive effects in the year 2014.

Table 5. Results of interrupted time series analysis, employment, Cerkno and Novo Mesto.

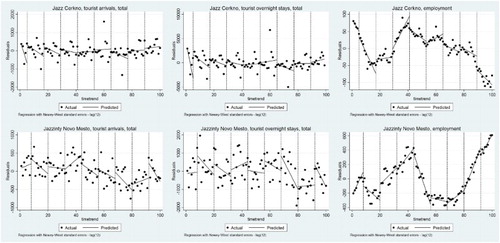

Finally, shows the dynamics of movements in tourism and employment, caused by the ‘shock’ in the form of each year’s festival in Cerkno and Novo Mesto. The vertical dotted lines represent the month of the festival (the ‘intervention/shock’), while the solid lines represent the movements of the observed variable, that is, tourism arrivals and overnight stays and employment.

Figure 3. Dynamics of the effects on tourism and employment, Cerkno and novo mesto. Source: own calculations.

Firstly, we can observe the same dynamics in the tourism variables as explained above: for Cerkno, there were time lasting effects in the early years and, in particular, in year 2014, while for Novo Mesto there were time lasting effects in 2010/2011 and 2015. Interestingly, as confirmed by results of , the effects on employment were even more timely for both cities: almost whenever there was a significant effect of the festival on the volume of employment, it was of a lasting nature, be it in a positive or negative direction. In particular, one can observe positive effects for Jazzinty Novo Mesto in years 2012–2014, which is in accordance with the results of . It, again, also confirms we are talking about static resilience – the timely effects show that not much additional renovation and reconstruction (which is surely not characteristic to ‘home-grown’ festivals) was needed to maintain the functions of the system when shocked.

6. Discussion and conclusion

This paper has examined the economic impact of two small Slovenian jazz festivals to make a positive contribution to the economic resilience of their host cities in 2008–2015. As we found evidence for the effect on tourism and employment in both cities, we can conclude that these festivals – even small in scale – may play a role and support the local economy to withstand the external shock represented by the financial crisis of 2008. Nevertheless, we identified different results over the studied years. It is clear that the festivals are reflected in the growth in the number of tourism and employment. However, this can be attributed to numerous reasons. Firstly, the results show an increase in both tourism and employment in the starting years in both jazz festivals, with significantly larger numbers for Jazz Cerkno. The latter has established itself as a ‘proper’ jazz festival, taking place since the middle of the 1990s and attracting a regular group of contributors and visitors.

Nevertheless, we can claim some evidence of the effects of the two ‘home-grown’ festivals on the static economic resilience of the two host towns. An additional level of new tourists and, as a consequence, new employment spaces, in particular in the early years of the festivals can surely be seen as a stimulus to local economic growth and, by this, to the economic resilience and welfare of the two towns. Furthermore, the economic effects – we used to measure the static economic resilience – were apparently on a timely basis, as evidenced by the coefficients on the interaction variables: they did not persist only in the month of the festival, but were more evenly spread across the year. However, the times of the financial crisis saw those effects significantly lessened if not disappeared as we have seen that the financial crisis seriously affected Slovenia’s economic resilience (Lapuh, Citation2016).

As matter of fact, the global economic crisis hit Slovenia severely in 2009 and GDP change was among the greatest in negative terms in the EU (−7.8%) (Stražišar, Strnad, & Štemberger, Citation2016). As consequence of the economic crisis employment has been falling since this year. During the economic crisis the highest drop was recorded in 2010 (by 2.1%), while in the second wave of the economic crisis (real GDP growth −2.7%) employment declined the most in 2013 (by 1.4%). Slovenia as other countries did not show to be economically resilient as was not able to fully recover from the crisis and the activity levels continuing to decline three years after the original downturn (ESPON, Citation2014). According to this macroeconomic study, although the country is not economically resilient, we can distinguish between East and West Slovenian regions: the former are characterized by activity levels continuing to decline three years and the latter by activity levels now rising but not achieved pre-crisis levels within three years of the original downturn while for the regional GDP resilience the trend is still not positive but it shows some positive signals as the activity levels were rising but not achieved pre-crisis levels.

Clearly, the economic crisis had its effect even beyond the mere cyclical effects on the level of Slovenia – we could claim it had an influence on both cities in a stronger manner than for the general country. This is in line and confirmed by Lapuh (Citation2016) who – analysing the impact of the recession on Slovenian statistical regions ad their ability to recover – showed that the regions of Gorizia (Cerkno) and Southeast Slovenia (Novo Mesto) are lagging behind in their recovery. In terms of GDP per capita, Southeast Slovenia statistical region has one of the strongest shocks while in terms of registered unemployment rate (2008–2013) Gorizia region registered one of the strongest shocks (Lapuh, Citation2016).

Notwithstanding, some signs of the effects, returning in the years 2014–2015, can be observed for both cities, demonstrating the static economic resilience effects of the two festivals. Clearly, the effects of the financial crisis would be worse in terms of employment has there not been for the two festivals. On the other hand, it is very hard to quantify the actual contribution to the static economic resilience of those cities as no full data were available to perform general equilibrium and/or other models suggested by the literature (see e.g. Rose, Citation2004, Citation2007) to estimate the actual static economic resilience of a city/region/country. Also, such efforts, even if taken, might not show the complete picture, as many aspects suggest that static economic resilience is hard to isolate for a small city and for a single event. Moreover, it is also clear that the festivals contribute not just to the economic effects but to the social, environmental, cultural and spiritual value and identity of the towns. It would be interesting, therefore, to perform also studies following the qualitative and contingent valuation methodology (or any other methodology to assess those other values). Only then we would be really able to comprehensively and holistically assess the value and the impact of the two festivals to the total, ‘holistic’ resilience of the host cities.

Referring to cultural activities, the competition of different new festivals (jazz – see ; and of other musical genres) has surely contributed to the dissipation of the usual visitors and their decay in interest. Jazz Cerkno was in that time already not so new and it is possible that it suffered a crisis of identity in the latter years due to changes of its location. Additionally, both festivals can be classified as ‘home-grown’ festivals, being more attractive to home than to foreign visitors – the latter forming a large part of the impact of the Jazz Cerkno festival in the earlier years while decaying latter. Finally, Jazzinty Novo Mesto consists of several events, not necessarily being focused on the jazz festival performances as it includes a composition award and several workshops. It is therefore to no surprise that the effects of the Novo Mesto festival are even less visible in the number of new tourists and employment generated.

This study also presents some limitations. Evaluative research on the jazz festivals’ impacts has, until very recently, adopted predominantly the economic impact approach. This is despite a growing awareness of the potential limitations of results attained from the application of economic models alone. Future studies on jazz festivals have to focus on the sustainable competitiveness that such kind of events may generate and combine the analysis of social and economic effects to understand the contribution festivals make to social cohesion, civic participation and ultimately sustainable cultural capital in resilient regional communities. This will lead to develop a more holistic ‘picture’ of the festival capacity to support resilience in the host territory.

In both cases, the evidence (see e.g. City Council of Novo Mesto, Citation2016; Vidmar, Citation2016) provides indications that the festivals, at least indirectly, help local firms to grow and prosper (in Novo Mesto: Krka, Revoz; in Cerkno: some smaller companies like Hotel Cerkno, local groceries, etc.). The jazz festivals support the local business development. However, this research did not cover examples of direct festival involvement in the encouragement of social entrepreneurs, community businesses or enterprises and co-operatives, volunteers, which generate jobs, income and meet wider social and environmental objectives.

Future research could further explore the social economic impact of jazz festivals, first at country level and then across Europe, and the impact of the small festivals from visitor’s perspective, as well as relationship between the communities and the destination management aspects.

Nonetheless, article uses a novel methodology in cultural economics, developing only in the past year with few studies. It presents results, which both confirm the importance of the method as well as show its drawbacks. It would be very important to use this methodology notably more in future, as it promises to overcome the significant (inherent) methodological problems of both the economic impact studies and contingent valuation. We hope this article would provide another step in this research direction.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr Peter Baroš, secretary general of the Slovenian Music Information Centre (SIGIC), Mr Simon Kenda, head of the Jazz Cerkno Institute, Mr Jure Dolinar, head of the organization of Jazzinty Novo Mesto festival, who provided us the information on the two festivals and the participants at the Vienna Music Business Research Days, Vienna (29 and 30 September 2016) for their comments. Moreover, we would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Marilena Vecco http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6894-4361

Notes

1. The most used among practitioners database of festivals throughout Europe (http://jazzfests.net/) includes 1408; accessed on 20 August 2016.

2. Lodinec (Citation2009) lists over 40 definitions for the term of resilience.

References

- Allen, J., O’Toole, W., Harris, R., & McDonnell, I. (2011). Festival and special event management (5th ed.). Brisbane: Wiley.

- Andersson, T., Getz, D., & Mykletun, R. (2013). Sustainable festival populations: An application of organizational ecology. Tourism Analysis, 18(6), 621–634. doi:10.3727/108354213X13824558188505

- Bormann, F. (2015). Cultural tourism and sustainable development: A case study of the AvatimeAmu (rice) festival in Volta region, Ghana. Global Journal of Human-Social Science: Sociology & Culture, 15(1), 15–20. Retrieved from https://globaljournals.org/GJHSS_Volume15/3-Cultural-Tourism-and-Sustainable.pdf

- Bracalente, B., Chirieleison, C., Cossignani, M., Ferrucci, F., Gigliotti, M., & Ranalli, M. G. (2011). The economic impact of cultural events: The Umbria Jazz music festival. Tourism Economics, 17(6), 1235–1255. doi:10.5367/te.2011.0096

- Brand, F. S., & Jax, K. (2007). Focusing the meaning(s) of resilience: Resilience as a descriptive concept and a boundary object. Ecology and Society, 12(1), 1–23. doi:10.5751/ES-02029-120123

- Brown, M., Var, T., & Lee, S. (2002). Messina Hof Wine and Jazz Festival: An economic impact analysis. Tourism Economics, 8(3), 273–279. doi: 10.5367/000000002101298115

- Cartalis, C. (2014). Towards resilient cities – A review of definitions, challenges and prospects. Advances in Building Energy Research, 8(2), 259–266. doi:10.1080/17512549.2014.890533

- Childers, D. L., Pickett, S. T. A., Grove, J. M., Ogden, L., & Whitmer, A. (2014). Advancing urban sustainability theory and action: Challenges and opportunities. Landscape And Urban Planning, 125, 320–328. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.022

- Choi, J. P. (2003). Bundling new products with old signal quality, with application to the sequencing of new products. International Journal of Industrial Organisation, 21(8), 1179–1200. doi:10.1016/S0167-7187(03)00077-8

- City Council of Novo Mesto. (2016). Strategija razvoja turizma v Mestni občini Novo mesto do 2020–1. obravnava [Angl. Strategy for the development of tourism in the city municipality of Novo Mesto until 2020 – 1st hearing]. Novo Mesto: City Council of Novo Mesto. Retrieved from http://www.novomesto.si/media/doc/svet/seje/2016/14.20redna20seja20mandat20201420-202018/07.20Gradivo20Strategija20razvoja20turizma%20MONM.pdf

- Clifton, N., O’Sullivan, D., & Pickernell, D. (2012). Capacity building and the contribution of public festivals: Evaluating ‘cardiff 2005’. Event Management, 16(1), 77–91. doi:10.3727/152599512X13264729827712

- Common, M. (1995). Sustainability and policy limits to economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Crespi-Vallbona, M., & Richards, G. (2007). The meaning of cultural festivals: Stakeholder perspectives in Catalunya. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 13(2), 103–122. doi:10.1080/10286630701201830

- Curtis, F. (2005). Eco-localism and sustainability. Ecological Economics, 46(1), 83–102. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(03)00102-2

- Curwell, S., Deakin, M., & Symes, M. (Eds.). (2005). Sustainable urban development, Vol. 1: The framework and protocols for environmental assessment. New York: Routledge.

- Davies, A. (2011). Local leadership, rural revitalisation and festival fun. In C. Gibson & J. Connell (Eds.), Festival places: Revitalising rural Australia (pp. 25–43). Farnham: Ashgate.

- Desouza, K. C., & Flanery, T. H. (2013). Designing, planning, and managing resilient cities: A conceptual framework. Cities, 35, 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2013.06.003

- Douglas, M., & Wildavsky, A. (1982). Risk and culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- ESPON. (2014). Territorial dynamics in Europe economic crisis and the resilience of regions ( Territorial observation, n. 12). Luxembourg: European Union.

- Foley, J. A., De Fries, R., Asner, G. P., Barford, C., Bonan, G., Carpenter, S. R., … Snyder, P. K. (2005). Global consequences of land use. Science, 309, 570–574. doi:10.1126/science.1111772

- Frey, B. S. (2000). The rise and fall of festivals reflections on the Salzburg festival ( Working paper series ISSN 1424-0459, n. 48). University of Zurich.

- Getz, D. (2010). The nature and scope of festival studies. International Journal of Event Management Research, 5(1), 1–47. Retrieved from http://www.ijemr.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Getz.pdf

- Getz, D., & Andersson, T. (2008). Sustainable festivals: On becoming an institution. Event Management, 12(1), 1–17. doi:10.3727/152599509787992625

- Getz, D., Andersson, T., & Mykletun, R. (2013). Sustainable festivals: An organizational ecology approach. Tourism Analysis, 18(3/4), 621–634.

- Goldblatt, J. (1997). Special events best practices in modern event management (2nd ed.). New York: Nostr and Reinhold.

- Hiller, R. S. (2016). The importance of quality: How music festivals achieved commercial success. Journal of Cultural Economics, 40(30), 309–334. doi:10.1007/s10824-015-9249-2

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecological Systems, 4, 1–23. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

- Holling, C. S. (2001). Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems, 4, 390–405. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0101-5

- Hopkins, R. (2008). The transition handbook: from oil dependency to local resilience. Totne, England: Green.

- Horne, J., & Orr, J. (1998). Assessing behaviors that create resilient organizations. Employment Relations Today, 24(4), 29–39. doi:10.1002/ert.3910240405

- Hughes, T. P., Bellwood, D. R., Folke, C., Steneck, R. S., & Wilson, J. (2005). New paradigms for supporting the resilience of marine ecosystems. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 20(7), 380–386. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.03.022

- Huitema, B. E., & McKean, J. W. (2000). An improved portmanteau test for autocorrelated errors in interrupted time-series regression models. Behavior Research Methods, 39(3), 343–349. doi:10.3758/BF03193002

- Hunter, W. W. J. (1989). Economic-impact studies: Inaccurate, misleading and unnecessary. Industrial Development Review, 158(4), 10–16.

- ICOMOS. (2016). Cultural heritage, the UN sustainable development goals, and the New Urban Agenda, ICOMOS. Retrieved from http://www.usicomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Final-Concept-Note.pdf

- Jenks, M., & Jones, C. (Eds.). (2010). Dimensions of the sustainable city, Vol. 2: Future city. New York: Springer.

- Krikelas, A. C. (1992). Why regions grow: A review of research on the economic base model. Economic Review (July): 16–29. Retrieved from https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/frbatlreview/pages/67252_1990-1994.pdf

- Lapuh, L. (2016). Measuring the impact of the recession on Slovenia statistical regions and their ability to recover. Acta Geographica Slovenica, 56(2), 247–266. doi:10.3986/AGS.764

- Lazzaretti, L., & Cooke, P. (2015). Introduction to the special issue ‘the resilient city’. City, Culture and Society, 6, 47–49. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2015.05.001

- Lodinec, M. J. (2009). Definitions of resilience: An analysis. Community and Regional Resilience Institute. Retrieved from http://www.resilientus.org/about-us/definition-ofcommunity-resilience.html

- Myerscough, J. (1988). The economic importance of the arts in Britain, policy. London: Policy Studies Institute.

- Okech, R. N. (2011). Promoting sustainable festival events tourism: A case study of lamu Kenya. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 3(3), 193–202. doi:10.1108/17554211111142158

- O’Sullivan, D., & Jackson, M. J. (2002). Festival tourism: A contributor to sustainable local economic development? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(4), 325–342. doi: 10.1080/09669580208667171

- O’Sullivan, D., Pickernell, D., & Senyard, J. (2009). Public sector evaluation of festivals and special events. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1(1), 19–36. doi:10.1080/19407960802703482

- Paleo, I. O., & Wijnberg, N. M. (2006). Classification of popular music festivals: A typology of festivals and an inquiry into their role in the construction of music genre. International Journal of Arts Management, 8(2), 50–61.

- Perrings, C. (1998). Resilience in the dynamics of economy-environment systems. Environmental and Resource Economics, 11(3–4), 503–520. doi:10.1023/A:1008255614276

- Perrings, C. (2001). Resilience and sustainability. In H. Folmer, H. L. Gabel, S. Gerking, & A. Rose (Eds.), Frontiers of environmental economics (pp. 319–341). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Perrings, C. A., Mäler, K.-G., Folke, C., Holling, C. S., & Jansson, B.-O. (Eds.). (1995). Biodiversity conservation, problems and policies. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- Pickett, S. T. A., Cadenasso, M. L., & Grove, J. M. (2004). Resilient cities: Meaning, models, and metaphor for integrating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning realms. Landscape and Urban Planning, 69, 369–384. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.10.035

- Pickett, S. T. A., McGrath, B., Cadenasso, M. L., & Felson, A. J. (2014). Ecological resilience and resilient cities. Building Research & Information, 42(2), 143–157. doi:10.1080/09613218.2014.850600

- Pimm, S. L. (1984). The complexity and stability of ecosystems. Nature, 307, 321–326. doi:10.1038/307321a0

- Prentice, R., & Andersen, V. (2003). Festival as creative destination. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1), 7–30. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00034-8

- Quinn, B. (2005). Changing festival places: Insights from Galway. Social & Cultural Geography, 6(2), 237–252. doi:10.1080/14649360500074667

- Quinn, B. (2006). Problematising festival tourism: Arts festivals and sustainable development in Ireland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 14(3), 288–306. doi:10.1080/09669580608669060

- Quinn, B. (2013). Arts festivals, tourism, cities, urban policy. In D. Stevenson & A. Matthews (Eds.), Culture and the city: Creativity, tourism, leisure (pp. 69–84). Oxon: Routledge.

- Ramchandani, G. M., & Coleman, R. J. (2012). Testing the accuracy of event economic impact forecasts. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 3(2), 188–200. doi:10.1108/17582951211229726

- Richards, G., & Wilson, L. (2004). The impact of cultural events on city image: Rotterdam, cultural capital of Europe 2001. Urban Studies, 41(10), 1931–1951. doi:10.1080/0042098042000256323

- Riley, M., & Laine, M. (2006). The value of jazz in Britain report commissioned by jazz services ltd. Westminster: University of Westminster.

- Robertson, M., Rogers, P., & Leask, A. (2009). Progressing socio-cultural impact evaluation for festivals. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1(2), 156–169. doi:10.1080/19407960902992233

- Rose, A. Z. (2004). Defining and measuring economic resilience to disasters. Disaster Prevention and Management, 13, 307–314. doi:10.1108/09653560410556528

- Rose, A. Z. (2007). Economic resilience to natural and man-made disasters: Multidisciplinary origins and contextual dimensions. Environ Hazards, 7, 383–398. doi:10.1016/j.envhaz.2007.10.001

- Saayman, M., & Rossouw, R. (2010). The Cape Town international jazz festival: More than just jazz. Development Southern Africa, 27(2), 255–272. doi:10.1080/03768351003740696

- Saayman, M., & Rossouw, R. (2011). The significance of festivals to regional economies: Measuring the economic value of the grahams town national arts festival in South Africa. Tourism Economics, 17(3), 603–624. doi:10.5367/te.2011.0049

- Schuster, J. (1995). Two urban festivals: La Mercè and First Night. Planning Practice and Research, 10, 173–188. doi: 10.1080/02697459550036694

- Seaman, B. A. (2000). Arts impact studies: A fashionable excess. In G. Bradford, M. Gary, & G. Wallach (Eds.), The politics of culture: Policy perspectives for individuals, institutions and communities (pp. 266–285). New York, NY: New Press.

- Skinner, S. J. (2006). Estimating the real growth effects of blockbuster art exhibits: A time series approach. Journal of Cultural Economics, 30, 109–125. doi:10.1007/s10824-006-9010-y

- Srakar, A., & Vecco, M. (in press). Ex-ante vs. Ex-post: Comparison of the effects of the European capital of culture Maribor 2012 on tourism and employment. Journal of Cultural Economics.

- Sterngold, A. H. (2004). Do economic impact studies misrepresent the benefits of arts and cultural organizations? The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 34(3), 166–187. doi:10.3200/JAML.34.3.166-187

- Stražišar, N., Strnad, B., & Štemberger, P. (2016). National accounts on the economic crisis in Slovenia. Ljubljana: Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved from http://www.stat.si/StatWeb/en/publications

- Sutcliffe, K., & Vogus, T. (2003). Organizing for resilience. In K. Cameron (Ed.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 94–110)). San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

- Swilling, M., & Annecke, E. (2012). Just transitions explorations of sustainability in an unfair world. Claremont, South Africa: UCT Press.

- Van Winkle, C. M., & Woosnam, K. M. (2014). Sense of community and perceptions of festival social impacts. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 5(1), 22–38. doi:10.1108/IJEFM-01-2013-0002

- Verbič, M., Srakar, A., Majcen, B., & Čok, M. (2016). Slovenian public finances through the financial crisis. Teorija in Praksa, 53(1), 203–227. Retrieved from http://www.fdv.uni-lj.si/docs/default-source/tip/tip_1_2016_verbic_idr.pdf?sfvrsn=2

- Vickers, S. G. (1995). The Art of judgment: A study of policy making. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Victor, P. A. (2008). Managing without growth. Slower by Design, Not Disaster. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Vidmar, I. (2016, May 23). Jazz Cerkno dobiva terapevtske razsežnosti [Engl. Jazz Cerkno is becoming therapeutic dimensions]. Dnevnik. Retrieved from https://dnevnik.si/1042736104/kultura/glasba/jazz-cerkno-dobiva-terapevtske-razseznosti-

- Waitt, G. (2008). Urban festivals: Geographies of hype, helplessness and hope. Geography Compass, 2, 513–537. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00089.x

- Williams, M., & Bowdin, G. A. J. (2007). Festival evaluation: An exploration of seven UK arts festivals. Managing Leisure, 12(2), 187–203. doi:10.1080/13606710701339520

- Zifkos, G. (2014). Sustainability everywhere: Problematising the ‘sustainable festival’ phenomenon. Tourism Planning & Development, 12(1), 6–19. doi:10.1080/21568316.2014.960600