ABSTRACT

Spatial planning using a landscape approach has been recognized as being essential for reconciling ecological, cultural and socio-economic dimensions in sustainable development (SuD). Although embraced as a concept, there is a lack of planning tools capable of incorporating multi-level, multifunctional and multi-sectoral perspectives, especially in a rural context. The departure point in this paper is the legal requirements for municipal comprehensive planning (MCP) in Sweden and an e-mail survey about incentives, stakeholder involvement, policy integration and implementation in MCP in all 15 Swedish mountain municipalities. The purpose of this explorative study is to examine whether MCP could be a tool in planning for SuD. Results indicate a general lack of resources and a low status of MCP that affect, and even limit, stakeholder involvement, policy integration and implementation. However, legal requirements for MCP are targeted at SuD, and municipal personnel responsible for planning appreciate the potential of MCP. Therefore, there is potential to develop the MCP into an effective landscape planning tool. To accomplish this, the status of an active planning process has to be raised, the mandate of the local planning agency has to be secured, and residents and land users have to be involved throughout the planning process.

Introduction

Public sector-led spatial planning is considered important in the re-scaling of international and national issues and objectives to the local level (Albrechts, Citation2004), but planning could also depart from the local/regional arena. Regardless of whether the perspective taken is top-down or bottom-up, there is a need for spatial coordination and consideration of the landscape in all kinds of land use. The need to involve local, practical examples to secure relevance has been suggested by, for example, Koschke et al. (Citation2014) for the application of ecosystem services in practical planning and decision-making (Beery et al., Citation2016). It is through planning at local and regional levels that overall economic, environmental, cultural and social sustainability can be achieved (Andersson, Angelstam, Axelsson, Elbakidze, & Törnblom, Citation2013; Coenen, Citation1998). In this respect, municipality/city councils (in Scandinavia, but not in the EU in general where the regional level is emphasized) are the central governance and decision-making or implementing actors in sustainability work and, thus, the municipality itself is the focal spatial entity.

The relevance and use of spatial planning have been questioned from time to time in many countries (Mintzberg, Citation1994; Wilson, Citation1994), but have now resurfaced as an important political instrument – especially at the local level (Montin, Johansson, & Forsemalm, Citation2014). One driver in this shift has been the fact that spatial planning has been singled out as an important tool for achieving the sustainable development (SuD) perspectives launched in Our Common Future (World Commission on Environment and Development, Citation1987) and Agenda 21 (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Citation1992). Various European policies now highlight the importance of spatial planning for the long-term sustainability of regions (European Commission, Citation1999; Council of Europe Citation2000; European Council, Citation2011). Following on from this, there is now a growing interest in spatial planning all over Europe, particularly at the central and regional levels. However, not much is known about how and whether these plans are actually being implemented or guiding practice.

In Sweden, spatial planning is a municipal monopoly (SFS, Citation2010:900). The National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (NBHBP) is the advisory agency regarding spatial planning, but there is no supervisory or executive planning agency at the national level. Different actors such as landowners, municipalities, County Administrative Boards (CABs) and the Swedish Forest Agency work separately to implement policies concerning sustainability, contributing to the lack of coordination in the planning process (Stjernström, Karlsson, & Pettersson, Citation2013). Hence, Sweden has no concerted landscape-scale territorial land-use planning (i.e. at broad geographic scales that cover, for example, a gradient of land cover types, several separate land holdings or an entire watershed area). However, there is a growing need for landscape approaches and integrated spatial planning, in order to meet national-level environmental objectives and new policies promoting green infrastructure (Andersson et al., Citation2013; Plieninger et al., Citation2015; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency [SEPA], Citation2016a).

The use of landscape approaches to integrated land-use management is increasingly being encouraged to try and find viable trade-offs between conservation and development (Sayer, Citation2009; Sayer et al., Citation2013). Although landscape approaches originated from conservation theory, their development has been stimulated by recognition of both the importance of the people who ultimately shape landscapes (Lawrence, Citation2010) and the spatiotemporal connectivity of habitats and structures at large geographic scales, that is, the green infrastructure concept (Benedict & McMahon, Citation2006). The most pervasive challenges to implementing a landscape approach are institutional and governance concerns (Sayer et al., Citation2013). Hence, landscape approaches, as understood here, include tactical and operational components such as spatial planning but also strategic components such as institutional, policy and spatiotemporal perspectives of the multifunctional values and functions of nature.

The main extant spatial planning process with the potential to develop the landscape approach in Sweden is municipal comprehensive planning (MCP) (Persson, Citation2013). Every municipality has to have an updated MCP document that states what the present and intended land use is, as well as all national land-use interests for the whole municipal area. The MCP document should present the political vision and strategic choices for a long-term SuD of the physical environment (Nylund, Citation2014; SFS, Citation2010:900). The purpose of the MCP process and document is: (a) a state-of-the-art description of present and future land use, (b) an instrument for negotiations between local and national interests and (c) a strategic politically based plan for the future direction and the implementation of central directives. Additionally, the MCP also acts as a guideline for all other planning in the municipality. Therefore, MCP should be a multifunctional, multi-sectoral and multi-level tool.

The use of MCP as strategic spatial planning will, potentially, increase in the light of new policies linked to climate change and the ongoing unsustainable use of natural resources (Elbakidze et al., Citation2015; European Commission, Citation2013; Storbjörk & Uggla, Citation2015), and will facilitate the integration of local, regional and national sustainability issues. The original purpose of MCP was to decentralize planning and increase its relevancy to local conditions and residents, to produce greater legitimacy of planning and decisions (Larsson, Citation2011; Prop., Citation1985/1986:3, Citation1985/1986:1). There is, however, a legal requirement that MCP should be coordinated with national and regional objectives, policies and programmes. Furthermore, there have been strong expectations within Swedish regional policy on inter-municipal collaboration and regional coordination for the MCP process (Hilding-Rydevik, Håkansson, & Isaksson, Citation2011).

It could be argued that there is an urban-oriented tradition in the Swedish planning system created by responsible authorities, such as the NBHBP. This is also reflected in the research on Swedish MCPs, since it generally concentrates on planning in urban areas (e.g. Fredriksson, Citation2011; Malbert, Citation1998; Sandström, Citation2002). Furthermore, research has predominantly focused on areas such as specific aspects of the plan or the planning process, for example, how sustainability is handled in MCP (Åkerskog, Citation2009; Andersson et al., Citation2013; Guinchard, & Cars, Citation1997; Nilsson & Iversen, Citation2015; Persson, Citation2013), on different attachment MCPs such as wind power, rural development in shoreline areas and in-depth plans for towns and larger villages/districts (Gullstrand, Löwgren, & Castensson, Citation2003; Kalbro, Lindgren, & Paulsson, Citation2012; Khan, Citation2003; Söderholm, Ek, & Pettersson, Citation2007; Söderholm & Pettersson, Citation2011), on public participation (Henecke & Khan, Citation2002; Johansson, Citation2001; Malbert, Citation1998; Morf, Citation2005) and on MCP as a learning process (Elbakidze et al., Citation2015). Studies on how legal requirements for MCP are handled in practice are rare and mainly found in undergraduate theses and similar studies (e.g. Larsson, Citation2011; Lundgren, Citation2013). A study of the role and potential of MCP, and a critical assessment of its practical use from a sustainable landscape planning perspective and for strategic land-use management, principally in a rural context, is thus much needed.

Some 160 of the 290 municipalities in Sweden have MCP documents adopted prior to 2010 (Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Citation2014) and among these, the 197 rural municipalities (defined as having fewer than 30,000 inhabitants, no town with more than 25,000 residents and at least 5 inhabitants per km2) are well represented. Among the rural municipalities are 15 ‘mountain municipalities’, situated along the Scandinavian Mountain Range (), which are some of the most rural areas in Sweden (The Swedish Board of Agriculture, Citation2016). Only 5 of the 15 mountain municipalities in Sweden have a MCP document adopted in 2010 or later.

Figure 1. European map displaying Sweden, the 4 mountain counties of Norrbotten, Västerbotten, Jämtland and Dalarna with the 15 mountain municipalities marked in grey.

The overall aim of this explorative study is to examine and analyse the Swedish MCP as a strategic tool and its potential for development into an instrument for sustainable landscape planning in rural areas rich in natural resources.

The starting point of the study is the intended use of, and legal requirements for, MCP as a process and document (protocol). MCP in mountain municipalities, according to municipal officials (reality), is studied and described. The implications for MCP using the discrepancy between protocol and reality are discussed, as well as the rural municipality as an agency in relation to supervisory and advisory regional and national agencies in the planning process and the potential for using MCP as a strategic tool for sustainable landscape planning. Overall, the analysis carried out is based on Ziafati Bafarasat’s (Citation2015) understanding of strategic spatial planning: ‘ … that it mediates between the respective claims on space of the state, market, and community around three considerations: stakeholder involvement, policy integration, and implementation’ (Ziafati Bafarasat, Citation2015, p. 132). These three key features are considered to be crucial concerns in the spatial planning process, but also prerequisites for achieving sustainable development (Baker & Eckerberg, Citation2008; Eckerberg & Dahlgren, Citation2007). Thus, it can be used as an analytical frame to study the variety of designs and planning practices in different contexts and settings. Accordingly, the key features are used here as an analytical frame for the actual conditions for MCP in the Swedish mountain municipalities. Preconditions for MCP, in terms of available resources (human, financial, time and knowledge), are also addressed in the study as these are contextual factors that, both directly and indirectly, affect consultations with the public (stakeholder involvement), scope of the planning (policy integration) and MCP enforcement (implementation).

Material and methods

Research area

The 15 mountain municipalities extend from the Norwegian border to central parts of the northern Swedish inland region (see ).

The total area of these municipalities is over 155,000 km2, nearly 30% of the total area of Sweden, and they currently hold 1.4% of the total population in Sweden, out of about 9.7 million (Statistics Sweden, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). The residents mostly live in one or two population centres in each municipality. However, during high season periods, the population in many of the municipalities can hugely increase due to tourism and second-home residents, with high concentrations in a few small villages (Lundmark & Marjavaara, Citation2005).

The Sami have cultural rights and rights to self-determination in traditional territories, including the mountain region (Prop., Citation1976/1977:80, Citation1998/1999:143, Citation2009/2010:80; SFS, Citation2009:724). Thus, the role of the Sami people in any landscape planning context concerning their traditional territories is clearly imperative.

Large parts of the area in the municipalities are protected land (see ). Forestry is carried out on nearly all productive forest land, which is owned predominantly by forest companies, non-industrial private forest owners and the State. Eight of the 12 large river systems are mostly used for hydro power production. Wind power farms are being built, the mining industry is expanding and recreational activities (hunting, fishing, hiking, skiing, snow mobile driving, etc.) are carried out on privately owned land as well as in commercial contexts on all types of land, based on property rights and the right of public access (Heberlein, Fredman, & Vuorio, Citation2002; Sandström, Citation2015; Zachrisson, Sandell, Fredman, & Eckerberg, Citation2006). Reindeer husbandry is ongoing across the whole mountain area.

Study design

The empirical data for this explorative study are based on legal requirements and strategic documents concerning MCP in Sweden (i.e. protocol), and an e-mail survey to all 15 mountain municipalities regarding their work with, and experiences of, MCP (i.e. reality).

The survey was designed to gain insight into the overall experience of local government work with the MCP process in natural resource-rich rural municipalities, with regard to: (I) responsibilities, delegations and planning strategy, (II) the extent, nature and effects of participatory processes in the context of MCP work, (III) policy integration in terms of broad-ranging (i.e. multi-sectoral and multi-level) or more selective focus in MCP and (IV) the implementation of the plan (see Supplementary material).

The survey was sent to officials responsible for MCP in all 15 municipalities with an explanation of the survey’s purpose and how to respond to it (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, Citation2014). Thirteen out of 15 municipalities responded. There are limitations with self-reported data, but since most mountain municipalities lack a specific planning administration, this was a suitable method to capture the perceived ‘reality’ of MCP according to responsible municipal officials. All respondents were anonymous and they reported on perceived problems and weaknesses regarding the MCP even though that meant presenting themselves and/or their organization in an unfavourable manner. Thus, their answers have been perceived as reliable. The risk of misunderstanding and misinterpretations among respondents was handled by allowing them to contact us for clarifications or questions, which some of them did. The responses received were coded and compiled. Information about MCP (such as year of adoption, description of planning process, etc.) in the two municipalities that did not respond to the survey was obtained from their MCP documents. All 13 survey responses were triangulated with information in the plan documents.

Analytical framework

Key features in spatial planning

Ziafati Bafarasat (Citation2015) identified three schools of strategic spatial planning: the performance school, the school of innovative action and the school of transformative strategy formulation. The schools are defined by the responsible planning agency and three key features of planning: ‘stakeholder involvement’, ‘policy integration’ and ‘implementation’ (). The schools were developed based on ideas about planning from different national contexts, mainly in urban settings. Ziafati Bafarasat elaborated on the key features’ dichotomies inherent in the merger of regional planning and comprehensive city planning. However, we argue that the key features also have the potential to function as an analytical tool (to sort, systematize and/or compare) in a national (Swedish) context, at a municipal level and in a rural setting.

Table 1. An overview of key features in relation to the three schools of thoughts.

A democratically accountable and trusted planning agency can persuade recognized actors in society that change is desirable. In return, the agency gains power from networking and political legitimacy. Such a planning agency is, according to Ziafati Bafarasat (Citation2015), required in ‘the school of transformative strategy formulation’. With reference to planning agency, legal requirements or ‘protocol’, it can be understood that the goals of Swedish MCPs best correspond to the school of transformative strategy formulation. In this study, we examine the mountain municipalities’ MCPs, based on the key features. The key features and our operationalization of them are introduced now.

Stakeholder involvement

According to ‘the performance school’, with a top-down process (cf. Faludi, Citation2000), only organized interests should be involved in the planning process. Public participation is limited; consultative procedures usually ask residents to choose from a predetermined set of options (Ziafati Bafarasat, Citation2015). In ‘the school of innovative action’, with a bottom-up process, inclusive debates should lead to innovative spatial development influenced by people (cf. Oosterlynck, Albrechts, & Van den Broeck, Citation2011). Hence, the dichotomy of efficiency versus inclusivity is not recognized according to Ziafati Bafarasat (Citation2015) (). In ‘the school of transformative strategy formulation’, the greatest effects of stakeholder involvement are gained from tangible project-specific deliberations. A criticism of this school is that the grassroots are commonly included in the policy-making phase, but are excluded from the negotiation phase based on their confusion, low technical legitimacy and inability to provide desired organizational resources (Ziafati Bafarasat, Citation2015).

In our survey, we captured the type and level of stakeholder involvement in MCP, ranging from efficiency to inclusivity, by the questions ‘How were municipal residents involved in the planning process of your current MCP document?’ and ‘How were different community and land-use interests involved in the planning process of your current MCP document?’.

Policy integration

In ‘the performance school’, the integration of high-level policy objectives with less immediate investment implications, that is, broad-ranging approach or multi-level and multi-sectoral policy integration, is a cornerstone to avoiding tension in representative/corporate deliberations according to Ziafati Bafarasat (Citation2015). The incremental integration in ‘the school of innovative action’ leads to broad-ranging outcomes, suggesting a strategic approach to spatial planning with a selective focus (on a few goals and places) (cf. Albrechts, Citation2006; Oosterlynck et al., Citation2011). In ‘the school of transformative strategy formulation’, the inclusionary ethos suggests an inherently broad-ranging (i.e. multi-level and multi-sectoral) approach to policy integration. However, various actors with clear objectives and expectations are all searching for assurances regarding recognition of their specific priorities. This ‘fairness approach’ in spatial planning requires substantial resources (Ziafati Bafarasat, Citation2015).

In our survey, the range between broad and selective policy integration (multi-level and multi-sectoral scope or not) in MCP is captured by the questions ‘Do you have any thematic supplements and/or in depth MCP documents in/attached to your main MCP document?’ followed by, ‘If yes, which?’, and ‘For what reason did your municipality choose to develop attachment plans to your main MCP document?’. There was also a question regarding the respondents’ appreciation of the connections between MCP and national and regional goals and policies, which are legal requirements.

Implementation

The idea behind implementation in ‘the performance school’ is described as ‘strategic spatial planning gives shape to spatial development in an indirect way […] by giving shape to the minds of those who subsequently act on the space … ’ (Ziafati Bafarasat, Citation2015, p. 135). According to ‘the school of innovative action’, strategic spatial planning is enforced through strategic projects, where a range of actors interact (Ziafati Bafarasat, Citation2015; see also Oosterlynck et al., Citation2011). In ‘the school of transformative strategy formulation’, stakeholder involvement is considered to result in efficient decisions as well as efficient actions. Projects are an output of spatial strategies but they also play a key role in empowering grassroots in strategy making and hence levelling influence and improving prospects of plans built on consent (Ziafati Bafarasat, Citation2015).

The implementation of Swedish MCPs, defined by the laws regulating it, sees the plan functioning as guidance for decisions concerning land use. Compared to the Swedish case, the planning levels studied by Ziafati Bafarasat (Citation2015) were somewhere between MCP documents and detailed plans. Therefore, due to the overarching scope of MCP, the dichotomy of plan and project is not applicable in this study. To adjust it to the national context and accomplishment of MCP, the implementation is viewed in terms of ‘just a “plan”’ (a dusty document on the bookshelf) or an active process and a ‘useful “tool”’. The questions asked were: ‘How is MCP followed up in your municipality?’, ‘Do you use the MCP document actively in your work and what for?’ and ‘In your experience, do you think other actors take your MCP into account?’ with a request to assess the use among actors, including CAB, other governmental agencies, and other municipalities and developers.

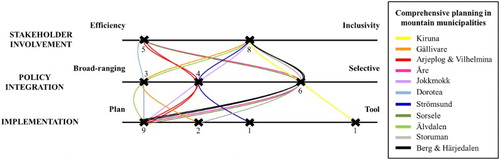

To sum up, stakeholder involvement is identified and discussed from efficiency and inclusivity aspects, policy integration is either broad-ranging (i.e. multi-sectoral and multi-level) or selective while implementation can be defined as either a plan or an active process, that is, a tool (). This dichotomy guides our analysis of spatial strategy practices in the mountain municipalities.

Background

Protocol – legal requirements of MCP

As stated in the introduction, the municipalities hold the statutory responsibility of updated planning of land and water use within their territories. The legal system for municipal spatial planning comprises legally binding detailed plans, and the non-binding MCP. In the MCP document, the municipality should present their policies for development regarding fundamentals of the intended land and water use within the municipality and how the built environment should be used, developed and preserved to meet housing needs. The MCP document should also report how the local government plans to consider and prioritize among different public interests in general, and appointed national interests in particular, in land-use decisions. Moreover, to ensure the role of MCP as a strategic tool, the plan has to indicate how the municipality intends to consider national and regional objectives, plans and programmes (SFS, Citation1998:808; SFS, Citation2010:900).

Designation of geographic areas as ‘Areas of National Interest’ implies that appointed government agencies have identified geographic areas as having some aspect considered to be of national interest such as nature, cultural heritage, outdoor recreation, energy production, mining (also regulated by specific legislation overriding property rights and MCP), fishing, reindeer husbandry, communications and waste management. Areas recognized for these aspects are extensive and often overlapping (, map a). National interest recognition does not imply full legal protection of that particular land use and, hence, the ongoing land use is not affected. However, they can be overlapped by legally protected areas (see later) and, in the case of a potential change in land use, this has to be evaluated against the values stated as national interests. In the MCP process, the local government must consult with the CAB, which speaks on behalf of the State, regarding values and borders of the national interest areas and ensure that the values are safeguarded (NBHBP, Citation2016a; SFS, Citation1998:808; SFS, Citation2010:900).

In many cases, geographically overlapping Areas of National interest are Natura 2000 areas, appointed and regulated by the European Council (Citation1999, Citation2009) (also considered to be of national interest) and legally protected areas (such as national parks and nature and culture reserves) for which land use is formally regulated and managed by the Swedish government (SEPA, Citation2016b) (, map b).

In Sweden generally, and in the mountain municipalities specifically, the local government has limited influence on land use defined by property rights. In mountain municipalities, the State controls virtually all land (mountains and forest land) in the western areas. The majority of the land east of the mountains is forest land (, map c) owned by non-industrial private forest owners, forest companies and forest commons (Statistics Sweden, Citation2016c). Forestry is carried out on productive forest land (, map c) that has not been voluntarily set aside by the owners to develop freely (approximately 5%) or protected in reserves or national parks (approximately 11%, cf. , maps a and c) (Statistics Sweden, Citation2016c). Furthermore, forestry is regulated by the Forestry Act which is not linked to the laws regulating MCP. Forestry is not defined as a national interest; however, it is described as being ‘of national importance’ and must be safeguarded as ‘ongoing land use’ with land-use changes being negotiated (SFS, Citation1998:808).

If needed, to handle certain issues (i.e. wind power or cultural environments) or certain geographic areas (i.e. a town or district within the municipality) more in depth, the municipality can produce attachment plans to the main MCP document following the same protocol as the main MCP process (NBHBP, Citation2016b; SFS, Citation1998:808; Citation2010:900).

The NBHBP provides instructions on how to interpret the legislation and advice on planning principles. The CAB is responsible for reviewing the municipal planning to safeguard public and national interests. It is also obliged to provide suitable support and documentation regarding these interests (NBHBP, Citation2016c; SFS, Citation2010:900).

The aim of the legislation is to attain sustainability with a holistic perspective within the municipality, at a regional level and in the country as a whole through a process-oriented planning system. According to the NBHBP, MCP should be the foundation of an effective strategic planning process for SuD. This means that planning not only deals with the physical aspects of land and water use, but all three acknowledged dimensions of sustainability: ecological, social and economic (NBHBP, Citation2016d).

To ensure democracy in the planning process, the municipality has to consult the CAB, neighbouring municipalities, organizations affected by the plan and residents of the municipality regarding the proposals in the plan. How consultations occur, however, is not firmly regulated but very much a municipal decision. The full proposal has to be exhibited for at least two months before it is adopted (SFS, Citation2010:900).

MCP document applicability, with respect to the statutory requirements, must be tested at least once every four-year political term (SFS, Citation2010:900). Currently, many Municipality Councils merely decide to actualize the existing plan one political term after another, without revision. This implies that the applicability of the plans can be questioned; the procedure has been criticized by the NBHBP because it circumvents the original intentions of the legislation (cf. Fredriksson, Citation2011; Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Citation2014).

Results

Reality – current status of MCP

All 15 mountain municipalities face the same legal requirements regarding comprehensive planning but, in practice, there are great variations in how and with what efforts the MCP documents are produced. Our survey illustrates that the status, resources and process connected to MCP differ considerably among the municipalities. Only 4 of the 13 respondents (5 of the total 15 mountain municipalities according to their MCP documents) have an updated MCP document adopted during the last four-year political term. The majority of the municipalities have plans that are 15 or more years old (and three have ones as old as 24–25 years).

The variation among the mountain municipalities is striking with respect to specifically allocated resources, from 0 SEK in seven municipalities (in terms of employees less than one full time or none for MCP specifically) to over 1.2 million SEK per year (almost 118,000 €) in Åre municipality. There is some uncertainty as to whether the stated numbers actually apply to ‘running’ MCP processes in the municipalities or if they refer to an ongoing ‘project’, with a beginning and an end, to update an old plan. It is, however, reasonable to believe that the result as a whole indicates that MCP has generally low priority in mountain municipalities. This assumption is strengthened by the fact that nearly all (12) of the respondents stated a lack of personnel for MCP work. Also, more than half of the respondents (seven) stated a lack of financial means and competence.

It is true that up to one full time person (distributed over part time posts) is dedicated to MCP but the people in question also have many other tasks that tend to steal time from the MCP work. The same applies to competence, which is found to varying degrees in a number of municipal officials, but they mostly have too little time available, beyond the time needed for their routine work, to contribute very actively to the MCP work. (Berg)

Stakeholder involvement

The municipality has the statutory responsibility for MCP, but the practical work can be contracted out. According to protocol, stakeholder consultation regarding the plan proposal is mandatory, but how this happens is not firmly regulated apart from the final display of the plan. In the mountain municipalities, MCP is commonly a joint process, involving municipal officials, political working groups, the public and consultants. Only one of the respondents stated that the MCP document was developed entirely by a consultant. Most respondents (10) stated that their municipalities involved the public and different land-use interests/actors during the mandatory consultation and exhibition process. The rest did not know. Regarding other types of cooperation and/or consultations, it seems slightly more common to involve the public than land-use interests/actors. The most common way to involve them was through meetings or workshops. Surveys, web forums and the like have been used in three municipalities to collect the views of the public. In two cases, the municipality has used local projects to provide active participation of various interests and actors. A majority (eight) of the respondents thought that it was hard to engage certain groups, principally young people and families with small children. One respondent mentioned timing as being crucial for reaching different societal groups. Other respondents pointed to difficulties with engaging local politicians as well as municipality residents because the wide, visionary scope of MCP is hard to grasp.

The questions are big and hard to grasp; one is more interested in issues concerning the individual, much the same problems as with elections and pocketbook issues. / … / It is difficult to get continuity in the work. There is also no political drive in the matter. The discussion on strategic planning issues is often sidetracked on land use that takes the focus from the whole. (Storuman)

Policy integration

In almost all (11) of the responding municipalities, respondents stated that they had one or more attachment plans added to their main MCP documents. Wind power (eight) and rural development in shoreline areas (five) were the most common issues handled for the entire municipality and in-depth plans for towns and larger villages/districts (seven) were also fairly common. Reasons for developing attachment plans were stated as being a need to do so, because of the municipality size (large areas), due to legal demands, due to rapid growth in parts of the municipality or that ‘ … the level of detail needs to be higher than normally expected in a MCP document’ (Härjedalen). Wind power and rural development in shoreline areas are also quite ‘new’ issues in comparison with the age of the MCP documents of these municipalities. Furthermore, the municipalities were given the opportunity to apply for government grants in order to handle these issues in their MCP.

The supplement regarding wind power was created due to governmental grants and collaboration with neighbouring municipalities. The in-depth plan was developed because of rapid expansion of vacation settlement over a short time. (Vilhelmina)

Implementation

All respondents stated that the legal requirements regarding MCP were relevant to their municipality. It is interesting to link this result to the answers concerning whether the respondents used the MCP document and how often. The majority of them (seven) stated that they used the MCP document only every month and some of them (four) as rarely as once each year or never. Only two of the respondents used the MCP document on a daily or weekly basis. The main use was to ‘check’ other types/levels of planning and land use-related decisions so that they concurred with intentions stated in the MCP document. Most respondents thought that their municipality’s MCP document had clear links to other municipal plans and legally binding decisions, at least to some extent.

A majority of the respondents believed that the CAB (12) and external developers (seven) took the MCP of their municipality into account. Ten of the respondents did not know if other municipalities did, but seven of the respondents thought that other official agencies did. Only one of the municipalities (one with a ‘new’ plan) systematically evaluated its MCP document every fourth year before the old plan was actualized or it was decided to develop a new plan. All the other respondents stated that their municipalities actualized or adopted a new MCP document every fourth year without evaluation of the old plan (predominantly the municipalities with ‘new’ plans) or that their municipalities (all the ones with out-of-date plans) did not have a strategy for following up MCP. This implies that most mountain municipalities do not actually follow legal requirements.

Discussion

Comparison of MCP among the mountain municipalities

Two groups can be identified regarding ‘stakeholder involvement’, where five of the municipalities did no more than the legal requirements stipulate: final consultation and exhibition (which only produced minor adjustments in the MCP document) (). However, eight of the municipalities stated that they have strived for more collaboration in the planning process, and thus moved along the scale towards more inclusivity. They had additional, supplementary cooperation with residents and/or land-use interests that produced changes to the comprehensive plan on particular demarcated issues. This difference in the degree of people’s involvement in the planning process among municipalities was verified by a study of wind power planning, which showed that municipalities differed greatly in how much participation they allowed for (Khan, Citation2003).

Figure 3. Overview of the work on MCP in the responding 13 mountain municipalities placed on a ‘sliding scale’ in accordance to the dichotomy of the key features in spatial planning; stakeholder involvement, policy integration and implementation.

Regarding ‘policy integration’, three groups are identified in this study. Municipalities with a main MCP document, without attachments, are defined as broad-ranging (i.e. multi-sectoral) in their planning due to the legal requirements. However, most of these MCP documents are old, which imply that they actually do not have a sustainable landscape approach, at least not anymore. Municipalities with a few attachments slide on the scale towards a more selective planning process. Municipalities with, relatively speaking, many attachments are defined as having even more, but not entirely, selective planning processes (because they still have their broad-ranging main MCP document). Yet, it can be discussed what a more selective approach means in reality. Many of the attachments handle more recent and up-to-date issues and there seems to be an increased stakeholder involvement in these processes (cf. Khan, Citation2003; Morf, Citation2005). The possibility of finding funding for this type of plan implies that more resources are allocated to the planning processes. Thus, it can be argued that well-conducted and coordinated selective planning could conceivably strengthen a sustainable landscape approach to a higher degree than old broad-ranging plans. Also, according to Lundgren (Citation2013), new MCP documents generally show more consideration of regional objectives than older plans.

The key feature ‘implementation’ indicates four groups, or placements along the scale, of municipalities. The majority of the mountain municipalities do not have MCP documents that are used in the daily or weekly work of the local government, nor are they thought to be considered by other authorities. Furthermore, the absence of strategic evaluation before actualizing or re-developing the plan indicates that the MCPs are ‘just plans’. However, there are a few municipalities that use the MCP document more often, every month, week or day. Given that respondents in these municipalities also believed that other authorities do take their MCP into account, this indicates that MCP can be seen as more of a tool. Strategic evaluation of the plan before actualizing or re-developing is also a factor that pushes the municipality along the scale towards ‘tool’. The actual use of MCP documents in municipalities with relatively newly adopted plans, or in municipalities that put more monetary resources into the planning process, does not seem more frequent than in other municipalities. Instead, the answers from Kiruna, a municipality with a plan from 2002 and no obviously different budgeted resources but clearly the largest community centre in the mountain municipalities (18,000 inhabitants out of a municipal total of 23,000), indicate the highest level of implementation. The second largest community centre has half that population and the rest of them are far from such a size. It is not an ambiguous result, but it implies that the effect of the urban-oriented tradition in the Swedish planning system should be critically assessed regarding if and how it influences the prerequisites for successful strategic spatial planning in rural areas. Overall, no clear pattern can be detected, merely that there is indeed a discrepancy between protocol and reality in MCP due to available resources and priorities.

The discrepancy between protocol and reality

According to ‘protocol’, the aim of the Swedish planning legislation is to attain a sustainable, holistic perspective within the municipality, at a regional level and in the country as a whole (i.e. multi-sectoral and multi-level), through a process-oriented planning system. The ‘all-embracing’ legislation and the fact that MCP was originally aimed at decentralizing spatial planning in order to bring it closer to people and the landscape suggests that municipalities are responsible for adapting the scope and process of planning to local conditions (NBHBP, Citation2016e). On the other hand, the national interest system was developed to slow the progression of exploitation interests, in most cases prioritized over conservation interests in the municipalities (cf. Larsson, Citation2011). National interests have been described as State-regulated islands within municipal planning, which have led to conflicts arising between local and central government about both the designation and interpretation of national interest areas (Gustavsson, Citation2005). As stated in the introduction, there are also strong expectations, in Swedish regional policy and laws regulating MCP, for inter-municipal collaboration and regional coordination. These have been hard to realize, that is, because the process of regionalization and the creation of new regions causes confusion regarding the tasks of the different planning bodies at different geographical levels (Statens offentliga utredningar, Citation2016; Stjernström et al., Citation2013) Furthermore, public authorities are sectionalized (cf. Hilding-Rydevik et al., Citation2011; Montin et al., Citation2014). Many land uses, such as extraction of valuable substances and minerals, forestry and agriculture, are either of national interest or ‘of national importance’, governed by other laws and managed by specific national or regional governmental agencies or national boards. This implies that local government cannot actually plan for the management of these types of land use. A result, from ‘reality’, is that none of the respondents mentioned forestry as being an important issue in MCP even though the majority of the municipalities are largely covered by forest land (, map c). Given that considerable areas are designated as ‘national interests’ or legally protected (, maps a and b), this also implies that the municipal planning monopoly is somewhat mythical and that the municipalities are incapacitated by State control. The documented lack of allocated resources and political priority for MCP raises a question regarding as to what degree spatial planning, in the shape of Swedish MCP, really is a process at all at the fundamental municipal level. The plans are old and the municipalities find it difficult and/or do not have the resources to involve inhabitants and other stakeholders beyond what is required by law. They have problems with grasping broad-ranging policy integration and, hence, the legally defined multi-level and multi-sectoral MCP process. Their ability to actually plan with cooperation of land-use actors and for land uses governed and managed by specific laws and authorities, including the State, over the entire municipality is curtailed by monetary and personnel resources and institutional barriers. Lastly, the generally limited use of MCP documents among the respondents and the uncertain level of use among other potential users both indicate a low level of implementation, casting a shadow over the actual effect of MCP and its multifunctionality. This challenges the municipality as a planning platform. The requirements for MCP could, of course, change in some way so the municipalities could execute their planning responsibility with the desired results and effects. However, there might also be a risk that the planning system is changed, or even more likely that the CABs take over, at least some parts of, the spatial planning so that the municipal planning monopoly disappears. Then, the municipalities would lose their ability to lead the planning of a sustainable landscape development for their own benefit.

Conclusions

The methodological starting point of the legal requirements for MCP and the e-mail survey produced a satisfactory overall view of the MCP situation in the Swedish mountain municipalities. Using the theoretical dichotomy of the three central key features of spatial planning, ‘stakeholder involvement’, ‘policy integration’ and ‘implementation’ (Ziafati Bafarasat, Citation2015), to examine and analyse Swedish MCP appears to have been successful. We argue that this explorative study has indeed begun to fill the knowledge gap in an otherwise urban-oriented research field (cf. Fredriksson, Citation2011). The study not only generated novel insights into the prerequisites for using MCP as a strategic tool for sustainable landscape planning in rural areas, but also allowed us to identify limitations and opportunities for refinements and further research. In the light of the discussion above, it can be argued that MCP, in its current form, cannot fully serve as a useful and effective tool for the Swedish municipalities and for fulfilling the statutory ambitions regarding overarching landscape planning for SuD. As stated in the introduction, a general view is that public sector-led strategic spatial planning is vital for SuD. In addition, the attitudes among the respondents in this study regarding opportunities with MCP are consistently positive. Therefore, it is important for future research to examine the actual effects of MCP, how to overcome the existing institutional barriers in the MCP process and ultimately determine if/how MCP could be developed into a multi-level and multi-sector municipal tool that produces desired effects on land use and landscape development locally and regionally, as well as nationally.

Based on stakeholder involvement being considered important for the legitimacy of a plan, policy integration being a measure of the width of the scope and implementation being crucial for the ‘effect’ of the plan, it can be argued that Ziafati Bafarasat’s key features offer a useful framework for comparing and analysing spatial plans and planning processes in terms of their potential to be a tool for sustainable landscape development. The ability to adapt and use them in other national settings should, however, be further investigated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Therese Bjärstig http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6845-5525

Additional information

Funding

References

- Åkerskog, A. (2009). Implementeringar av miljöbedömningar i Sverige: fran EG-direktiv till kommunal översiktlig planering [Implementations of environmental assessment in Sweden: From EU directives to municipal comprehensive planning] (Doctoral dissertation). Uppsala : Sveriges lantbruksuniv., Acta Universitatis agriculturae Sueciae.

- Albrechts, L. (2004). Strategic (spatial) planning reexamined. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 31(5), 743–758. doi: 10.1068/b3065

- Albrechts, L. (2006). Bridge the gap: From spatial planning to strategic projects. European Planning Studies, 14(10), 1487–1500. doi: 10.1080/09654310600852464

- Andersson, K., Angelstam, P., Axelsson, R., Elbakidze, M., & Törnblom, J. (2013). Connecting municipal and regional level planning: Analysis and visualization of sustainability indicators in Bergslagen, Sweden. European Planning Studies, 21(8), 1210–1234. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.722943

- Baker, S., & Eckerberg, K. (Eds.). (2008). In pursuit of sustainable development: New governance practices at the sub-national level in Europe. Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group. Retrieved from https://books.google.se/books?hl=sv&lr=&id=_xQsEvzuhvkC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Baker+and+Eckerberg+2008&ots=liEtU_8e8V&sig=9nfCGZZULe6Tb1v_tuQu3u2wEH0&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Baker%20and%20Eckerberg%202008&f=false

- Beery, T., Stålhammar, S., Jönsson, K. I., Wamsler, C., Bramryd, T., Brink, E., … Schubert, P. (2016). Perceptions of the ecosystem services concept: Opportunities and challenges in the Swedish municipal context. Ecosystem Services, 17, 123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.12.002

- Benedict, M. A., & McMahon, E. T. (2006). Green infrastructure. Washington, DC: Island.

- Coenen, F. (1998). Policy integration and public involvement in the local policy process: Lessons from local green planning in the Netherlands. European Environment, 8(2), 50–57. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0976(199803/04)8:2<50::AID-EET148>3.0.CO;2-B

- Council of Europe. (2000). The European Landscape Convention. Strasbourg.

- Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Eckerberg, K., & Dahlgren, K. (2007). Project or process? Fifteen years’ experience with local agenda 21 in Sweden (English version). EKONOMIAZ. Revista vasca de Economía, 64(1), 124–141.

- Elbakidze, M., Dawson, L., Andersson, K., Axelsson, R., Angelstam, P., Stjernquist, I., … Thellbro, C. (2015). Is spatial planning a collaborative learning process? A case study from a rural–urban gradient in Sweden. Land Use Policy,48, 270–285. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.05.001

- European Commission. (1999). ESDP European spatial development perspective. Towards balanced and sustainable development of the territory of the European Union. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- European Commission. (2013). Green infrastructure (GI) – Enhancing Europe’s natural capital. COM 249.

- European Council. (1999). Council directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora.

- European Council. (2009). Directive 2009/147/EC of the European parliament and of the council of 30 November 2009 on the conservation of wild birds.

- European Council. (2011). Territorial agenda of the European Union 2020. Towards an inclusive, smart and sustainable Europe of diverse regions. In Agreed at the informal ministerial meeting of ministers responsible for spatial planning and territorial development on 19th May 2011. Hungary: Gödöllo?. Retrieved January 13, 2017, from http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/what/territorial-cohesion/territorial_agenda_2020.pdf

- Faludi, A. (2000). The performance of spatial planning. Planning Practice and Research, 15(4), 299–318. doi: 10.1080/713691907

- Fredriksson, C. (2011). Planning in the ‘new reality’: Strategic elements and approaches in Swedish municipalities (Doctoral dissertation). Stockholm: KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

- Guinchard, C. G., & Cars, G. (1997). Swedish planning: Towards sustainable development. Swedish Society for Town and Country Planning [Fören. för samhällsplanering]..

- Gullstrand, M., Löwgren, M., & Castensson, R. (2003). Water issues in comprehensive municipal planning: A review of the Motala River Basin. Journal of Environmental Management, 69(3), 239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2003.09.007

- Gustavsson, K. (2005). Bland perifera riksintressen. In L-E. Jönsson & B. Svensson (Eds.), I industrisamhällets slagskugga. Om problematiska kulturarv s (pp. 113–137). Lund: Carlssons.

- Heberlein, T. A., Fredman, P., & Vuorio, T. (2002). Current tourism patterns in the Swedish mountain region. Mountain Research and Development, 22(2), 142–149. doi: 10.1659/0276-4741(2002)022[0142:CTPITS]2.0.CO;2

- Henecke, B., & Khan, J. (2002). Medborgardeltagande i den fysiska planeringen – en demokratiteoretisk analys av lagstiftning, retorik och praktik (Report). Lund: Department of Environmental and Energy Systems Studies, Lund Institute of Technology, Lund University.

- Hilding-Rydevik, T., Håkansson, M., & Isaksson, K. (2011). The Swedish discourse on sustainable regional development: Consolidating the post-political condition. International Planning Studies, 16(2), 169–187. doi: 10.1080/13563475.2011.561062

- Johansson, M. (2001). Citizens in planning consultation – theory and reality. In E. Asplund & T. Hilding-Rydevik (Eds.), Arena for sustainable development – actors and processes (pp. 61–77). Stockholm: Royal Institute of Technology, Regional Planning Section ( in Swedish).

- Kalbro, T., Lindgren, E., & Paulsson, J. (2012). Detaljplaner i praktiken: Är plan-och bygglagen i takt med tiden? Arkitektur och samhällsbyggnad. Stockholm: KTH.

- Khan, J. (2003). Wind power planning in three Swedish municipalities. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 46(4), 563–581. doi: 10.1080/0964056032000133161

- Koschke, L., van der Meulen, S., Frank, S., Schneidergruber, A., Kruse, M., Fürst, C., … Bastian, O. (2014). Do you have 5 minutes to spare? – The challenges of stakeholder processes in ecosystem services studies. Landscape Online, 37, 1–25. doi: 10.3097/LO.201437

- Larsson, K. (2011). Riksintressen i den översiktliga planeringen. (Examensarbete). Masterprogrammet i fysisk planering. Karlskrona: Blekinge Tekniska Högskola.

- Lawrence, A. (Ed.). (2010). Taking stock of nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lundgren, G. (2013). Beaktandet av regionala utvecklingsmål i kommunala översiktsplaner. En studie av situationen i Västerbottens län. Examensarbete i kulturgeografi. Institutionen för geografi och ekonomisk historia. Umeå: Umeå Universitet.

- Lundmark, L., & Marjavaara, R. (2005). Second home localizations in the Swedish mountain range. Tourism, 53(1), 3–16.

- Malbert, B. (1998). Urban planning participation: Linking practice and theory (Dissertation in Urban Design and Planning). Chalmers University of Technology, Göteborg, Sweden.

- Mintzberg, H. (1994). The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harvard Business Review, 72(1), 107–114.

- Montin, S., Johansson, M., & Forsemalm, J. (2014). Understanding innovative regional collaboration. In C. Ansell, & J. Torfing (Eds.), Public innovation through collaboration and design (pp. 106–124). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Morf, A. (2005). Public participation in municipal planning as a tool for coastal management: Case studies from western Sweden. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 34(2), 74–83. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-34.2.74

- National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. 2016a. Riksintressen är nationellt betydelsefulla områden [National interests are nationally important areas]. Retrieved February 16, 2017, from http://www.boverket.se/sv/samhallsplanering/sa-planeras-sverige/riksintressen-ar-betydelsefulla-omraden/

- National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. 2016b. Fördjupningar av och tillägg till översiktsplan [In depths and supplements to the municipal comprehensive plan]. Retrieved December 7, 2016, from http://www.boverket.se/sv/PBL-kunskapsbanken/oversiktsplan/processen-for-oversiktsplanering/fordjupningar-och-tillagg/

- National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. 2016c. Instruktioner och regleringsbrev för Boverket [Instructions and appropriations for the national board of housing, building and planning]. Retrieved December 7, 2016, from http://www.boverket.se/sv/om-boverket/boverkets-uppdrag/instruktion-och-regleringsbrev/

- National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. 2016d. Hållbar utveckling i översiktsplaneringen [Sustainable development in the municipal comprehensive planning]. Retrieved December 7, 2016, from http://www.boverket.se/sv/PBL-kunskapsbanken/oversiktsplan/hallbar-utveckling-i-oversiktsplaneringen/

- National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. 2016e. Översiktsplanens utformning [Comprehensive plan design.] Retrieved December 7, 2016, from http://www.boverket.se/sv/PBL-kunskapsbanken/oversiktsplan/oversiktsplanens-funktion/oversiktsplanens-utformning/

- Nilsson, K. L., & Iversen, E. (2015). Hållbar utveckling i fysisk planering och PBL-processer. Del 2; Exempel på kommuners processer, metoder och verktyg. Forskningsrapport. Luleå: Luleå Tekniska Universitet.

- Nylund, K. (2014). Conceptions of justice in the planning of the new urban landscape–recent changes in the comprehensive planning discourse in Malmö, Sweden. Planning Theory & Practice, 15(1), 41–61. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2013.866263

- Oosterlynck, S., Albrechts, L. O. U. I. S., & Van den Broeck, J. (2011). Strategic spatial planning through strategic projects. Strategic Spatial Projects: Catalysts for Change, 1–14. Retrieved from https://books.google.se/books?hl=sv&lr=&id=2GChAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT20&dq=Strategic+spatial+planning+through+strategic+projects&ots=APxfd-6sMl&sig=wXSeYDtv990sY-0zNUvGMOzhe1U&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Strategic%20spatial%20planning%20through%20strategic%20projects&f=false

- Persson, C. (2013). Deliberation or doctrine? Land use and spatial planning for sustainable development in Sweden. Land Use Policy, 34, 301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.04.007

- Plieninger, T., Bieling, C., Fagerholm, N., Byg, A., Hartel, T., Hurley, P., … van der Horst, D. (2015). The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 14, 28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2015.02.006

- Prop. (1976/1977: 80). Regeringens proposition 1976/77:80 om insatser för samerna [Prop. 1976/77: 80 Government Bill 1976/77: 80 on efforts for the Sami People].

- Prop. (1985/1986:3). Med förslag till lag om hushållning med naturresurser m.m [Prop. 1985/86:3 with draft law on the management of natural resources, etc].

- Prop. (1985/1986:1). Förslag till ny plan- och bygglag [Prop. 1985/86:1 Proposition for a new planning and building act].

- Prop. (1998/1999:143). Nationella minoriteter i Sverige [Prop. 1998/99:143 National minorities in Sweden].

- Prop. (2009/2010:80). En reformerad grundlag [Prop. 2009/10: 80 A reformed constitution].

- Sandström, U. G. (2002). Green infrastructure planning in urban Sweden. Planning Practice and Research, 17(4), 373–385. Retrieved from doi: 10.1080/02697450216356

- Sandström, P. (2015). A toolbox for co-production of knowledge and improved land use dialogues – the perspective of reindeer husbandry. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Suecicae – Silvestra, 20). Retrieved from https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/11881/

- Sayer, J. (2009). Reconciling conservation and development: Are landscapes the answer? Biotropica, 41(6), 649–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2009.00575.x

- Sayer, J., Sunderland, T., Ghazoul, J., Pfund, J-L., Sheil, D., Meijaard, E., … Garcia, C. (2013). Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 110, 8349–8356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210595110

- SFS. (1998:808). Environmental Act.

- SFS. (2009:724). National minorities and minority languages Act.

- SFS. (2010:900). Planning and building Act.

- Söderholm, P., & Pettersson, M. (2011). Offshore wind power policy and planning in Sweden. Energy Policy, 39(2), 518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2010.05.065

- Söderholm, P., Ek, K., & Pettersson, M. (2007). Wind power development in Sweden: Global policies and local obstacles. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 11(3), 365–400. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2005.03.001

- Statens offentliga utredningar. (2016). Delredovisning från Indelningskommittén, Fi 2015:09. Retrieved February 1, 2017, from http://www.sou.gov.se/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Delredovisning-Indelningskommitten-160229.pdf

- Statistics Sweden. (2016a). Kommunarealer den 1 januari 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2016, from http://www.scb.se/MI0802/

- Statistics Sweden. (2016b). Folkmängd i riket, län och kommuner 31 december 2014 och befolkningsförändringar 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2016, from http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Statistik-efter-amne/Befolkning/Befolkningens-sammansattning/Befolkningsstatistik/25788/25795/Helarsstatistik---Kommun-lan-och-riket/385423/

- Statistics Sweden. (2016c). Skyddad natur 2014-12-31. Retrieved October 19, 2016, from. http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Statistik-efter-amne/Miljo/Markanvandning/Skyddad-natur/24541/24548/Behallare-for-Press/390529/

- Stjernström, O., Karlsson, S., & Pettersson, Ö. (2013). Skogen och den kommunala planeringen. Plan, (1), 42–45.

- Storbjörk, S., & Uggla, Y. (2015). The practice of settling and enacting strategic guidelines for climate adaptation in spatial planning: Lessons from ten Swedish municipalities. Regional Environmental Change, 15(6), 1133–1143. doi: 10.1007/s10113-014-0690-0

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting, SKL). (2014). Aktuella kommunomfattande översiktsplaner. Läget i landet mars 2014 [Current municipal comprehensive plans. The situation in the country in March 2014]. Report, 18 p. (in Swedish) Stockholm: The Association of Local Authorities and Regions.

- Swedish Board of Agriculture (Jordbruksverket). 2016. Så här definierar vi landsbygd [This is how we define countryside]. Retrieved February 1, 2017, from http://www.jordbruksverket.se/etjanster/etjanster/landsbygdsutveckling/alltomlandet/sahardefinierarvilandsbygd.4.362991bd13f31cadcc256b.html

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. (2016a). Retrieved March 20, 2017, from. http://www.miljomal.se/sv/Environmental-Objectives-Portal/

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. (2016b). Skyddad natur [Protected nature]. Retrieved March 20, 2017, from http://www.naturvardsverket.se/Var-natur/Skyddad-natur/

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. (1992). Agenda 21: Earth Summit – the United Nations programme of action from Rio. New York, NY: Author. Retrieved February 2, 2017, from http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?documentid=52&articleid=61

- Wilson, I. (1994). Strategic planning isn’t dead – it changed. Long Range Planning, 27(4), 12–24. doi: 10.1016/0024-6301(94)90052-3

- World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zachrisson, A., Sandell, K., Fredman, P., & Eckerberg, K. (2006). Tourism and protected areas: Motives, actors and processes. The International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management, 2(4), 350–358. doi: 10.1080/17451590609618156

- Ziafati Bafarasat, A. (2015). Reflections on the three schools of thought on strategic spatial planning. Journal of Planning Literature, 30(2), 132–148. doi: 10.1177/0885412214562428