ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the concept of the entrepreneurial university by examining roles of academic entrepreneurship departments in driving regional economic development outcomes. While a wealth of research investigates the role, activities and function of the entrepreneurial university, very little which focuses specifically on academic entrepreneurship departments, where much of the research, teaching and knowledge exchange concerning entrepreneurship takes place. Two case studies of large and active entrepreneurship departments are presented to illustrate the different roles and activities they undertake in the sphere of economic development in their regions or locales. A dual model of engagement is proposed, whereby the entrepreneurship department operates within the framework of the entrepreneurial university, but also as a regional actor in its own right.

Introduction

The ‘entrepreneurial university’ has gained prominence as a knowledge and innovation actor, key to competitiveness, stimulation of economic growth and wealth creation in today’s globalized world (Fayolle & Redford, Citation2014; Mian, Citation2011). Studies in regional economic development have shown that universities are eager to position themselves as ‘entrepreneurial’ and building links to increase their impact within regions and beyond in tangible ways through engaging in third mission activities, such as licensing, spin-out and ‘knowledge transfer’ (Gordon, Hamilton, & Jack, Citation2012; Guerrero, Cunningham, & Urbano, Citation2015; Johnstone & Huggins, Citation2016; Larty, Jack, & Lockett, Citation2016). What is evident from previous work is how little we know about individuals from such universities, especially how those from academic entrepreneurship departments connect with their regional context and the mechanisms they might use to assist a university in its goal of becoming engaged and ‘entrepreneurial’; nor is much known about measuring these activities to determine the economic impact (Bramwell & Wolfe, Citation2008; Larty et al., Citation2016). This paper looks to being filling gaps in knowledge about the roles of entrepreneurship departments in driving regional economic development.

Audretsch (Citation2014) argues: the role of universities stretches beyond generating technology transfer (through, for example, patents, spin-offs and start-ups) encompassing wider roles such as contributing and providing leadership for creating entrepreneurial thinking, actions, institutions and entrepreneurial capital. It is within this wider appreciation of universities’ roles and activities, particularly in relation to how they engage in a regional context through their members, that this paper is situated; we are interested in how the entrepreneurial university adopts entrepreneurial management styles, with members who act entrepreneurially, and interacts with its community and region in an entrepreneurial manner (Klofsten & Jones-Evans, Citation2000). Recent work highlighted that network relationships in which university members engage and their ties within regions can play a significant role in building entrepreneurial activity and better position regions in global arenas (Dada, Jack, & George, Citation2015; Larty et al., Citation2016; Rose, Decter, Robinson, Jack, & Lockett, Citation2012).

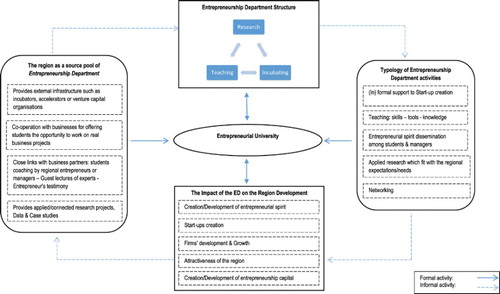

We might expect entrepreneurship departments to be at the vanguard of the entrepreneurial university. However, relatively little research has addressed the roles and activities of entrepreneurship departments within the discourse of the entrepreneurial university. By conducting case studies of ‘real world’ entrepreneurship departments, we identify six streams of activities undertaken within the domain of engagement. We find a variety of roles being performed, some more formal such as collaborative research, contract research and consulting and others more informal like providing ad hoc advice and practitioner networking (Perkmann et al., Citation2013); formal activities are performed through the wider structure of the ‘entrepreneurial university’ and also via direct links to regional networks and actors, whereas more informal roles are enacted through direct routes to the region. Arguably most difficult to measure are a host of informal arrangements that include participating in research consortia made up of university and private sector representatives, faculty consulting with or working in private firms, or firm-based personnel working in universities. While the importance of informal engagement is established, there are calls for more investigation into this (Abreu & Grinevich, Citation2013; Larty et al, Citation2016). Informal mechanisms which link individuals within entrepreneurship departments with regional networks emerge as being at least as important as more formal knowledge transfer activities. Entrepreneurship departments are found to be regional actors in their own right, and also part of the broader entrepreneurial university, interacting with the region directly and indirectly via the wider university structure.

Theoretical foundations

Universities have been described as ‘natural incubators’ (Etzkowitz, Citation2003, p. 111) at the very heart of innovation, creativity and economic growth. While not all universities are in such positions, the fact that universities need to be entrepreneurial in terms of their actions, orientation, education, structures, practices, culture and research is increasingly recognized (Fayolle & Redford, Citation2014). Nevertheless, actually making universities think and act entrepreneurially is a challenge, compounded by the lack of definition or consensus about what an entrepreneurial university is (Fayolle & Redford, Citation2014). However, key works have elaborated and made the case for the theory, with have been assimilated into our understanding here (Di Gregorio & Shane, Citation2003; Guerrero et al., Citation2015). Nonetheless, some universities show they are more able, proactive and innovative in engaging stakeholders, allowing them to become key actors in shaping communities, regions and societies (Johnstone & Huggins, Citation2016). The regional impacts of more traditional entrepreneurial university functions such as technology Transfer Offices, intellectual property, spin-outs and academic entrepreneurs are fairly well explored (Audretsch, Citation2014; Rose et al., Citation2012), but the understanding of softer and broader roles is less well established.

A broad definition of the entrepreneurial university by Etzkowitz, Webster, Gebhardt, and Terra (Citation2000) is any university taking on activities to ‘improve regional or national economic performance as well as the university’s financial advantage and that of its faculty’, differentiated from what Baldini, Fini, Grimaldi, and Sobrero (Citation2014) define as ‘academic entrepreneurship’, encompassing formal and informal mechanisms to commercialize research. The entrepreneurial university as a concept differs slightly from academic entrepreneurship, and regional entrepreneurship, though all are arguably strongly interrelated. The entrepreneurial university concept can be understood at the institutional level, whereas academic entrepreneurship refers to the activities and roles undertaken by individuals (Baldini et al., Citation2014). An entrepreneurial university can be any university that contributes and provides leadership for creating entrepreneurial thinking, actions, institutions and entrepreneurship capital (Audretsch & Keilbach, Citation2008). It has a broader role than just to generate technology transfer in the form of patents, licenses and start-ups, and we position ourselves alongside Audretsch’s (Citation2014) call for a move from the concept of the ‘entrepreneurial university’ to a university for the entrepreneurial society. We see entrepreneurship departments as having a key role to play within this dynamic through their roles in enhancing entrepreneurship capital and facilitating entrepreneurial behaviour through research, teaching and knowledge exchange activities within the entrepreneurial domain.

presents pertinent literature identifying the existing research gaps; it shows the range of activities that have been studied that can be placed under the ‘entrepreneurial university’ and knowledge exchange bracket. Comprehensive overviews of work in the field have already been written (see Drucker & Goldstein, Citation2007; Perkmann et al., Citation2013; Uyarra, Citation2010). While we found a wealth of contributions in the knowledge transfer field, many were premised on the exploitation or commercialization of science and technology-based research (Mian, Citation2011). Research examining wider regional roles, beyond knowledge transfer, and in contexts outside of the science and technology domain is less common (Audretsch, Citation2014; Johnstone & Huggins, Citation2016).

Table 1. Key themes in entrepreneurial university research.

We later return to this table to compare what we found with regard to entrepreneurship departments. We divide activities into ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ activities, which also can be referred to as ‘commercialization’ and ‘academic engagement’ (Perkmann et al., Citation2013) or ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ activities (Klofsten & Jones-Evans, Citation2000). Because of the variation in universities and Higher Education Institutions, the ways they are structured and the roles they play, not all activities of the ‘entrepreneurial university’ are necessarily carried out by a particular department or institution; they could be shared out between different parts of the university for instance, with entrepreneurship departments taking care of the entrepreneurship education elements and technology transfer offices handling the intellectual property.

Beyond well-researched areas of commercialization and knowledge exchange (Rose et al., Citation2012; Johnstone & Huggins, Citation2016), current knowledge on wider regional roles and impacts is confusing. Klofsten and Jones-Evans (Citation2000) suggest that the ‘softer’ side of academic-industry engagement is more widespread and important than more comprehensively studied technology spin-off activities. Contributions exploring a more nuanced and broad view of universities’ roles within their regions include Power and Malmberg (Citation2008), Smith and Bagchi-Sen (Citation2011) and Hughes and Kitson (Citation2012). However, these papers are more agenda setting and exploratory, and pose more questions than they provide answers; the current state of the art is very much one of shifting the focus of work on the entrepreneurial university and discovering the wide range of activities, roles and impacts therein. To understand the regional contribution of universities, and the knowledge they hold, it was also necessary to consult literature on knowledge spill-overs to understand debates around proximity and regional effects (Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch, & Carlsson, Citation2009; Audretsch & Keilbach, Citation2008). Guerrero et al.’s (Citation2015) study of United Kingdom (UK) entrepreneurial universities found research-intensive Russell Group universities achieve higher rates of economic impact through entrepreneurial spin-offs compared to other UK universities, mostly performing knowledge transfer. This paper responds directly to two core problems highlighted by Hughes and Kitson (Citation2012): an over-focussing on commercialization and technology transfer over less visible mechanisms, the focus on the science base ignoring knowledge exchange activities from across all disciplines.

While there has been increasing interest in the role of university members within the regional context via knowledge exchange (Dada et al., Citation2015; Rose et al., Citation2012), less has been said about how members engage with regions through networks and how relevant their ties to the region might be in positioning the ‘Entrepreneurial University’. Even less has been said about how networks might actually support regional development activities. Even so, networks created at the regional level are critical for supporting entrepreneurship (Gordon et al., Citation2012). We know people tend to engage much more through personal and informal network relationships built through trust and respect than through formal mechanisms (Jack, Moult, Anderson, & Dodd, Citation2010). We also know the creation of trust and sociability is a key for the long-term success of university and regional engagement (Gordon et al., Citation2012; Rose et al., Citation2012). So, understanding the ties of individual members may be critical to understanding how ‘Entrepreneurial Universities’ are perceived and positioned within the regional context. We also need to factor in to our conceptualization the absorptive capacity (cf. Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990) of the surrounding region, and in particular the other actors, such as firms and non-profit organizations, which influence the entrepreneurial ecosystem (cf. Cooke, Citation2016; Spigel, Citation2017), as opposed to viewing the entrepreneurship department and indeed the university as an island.

Methodology and case studies

Due to our interests, this paper is structured as an exploratory case study, useful for situations where the state of the art is emergent rather than established. This research was designed to illuminate activities undertaken and roles played by entrepreneurship departments, and the individuals and groups within them, through accessing a wide range of data sources and methods. It is structured as a comparative qualitative case study between two different but comparable entrepreneurship departments to encourage the conceptualization and theorization of their roles in precipitating regional economic development as a vital component of the entrepreneurial university. The two departments chosen as case studies – EMLYON’s Entrepreneurship Department and the Institute for Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development (IEED),Footnote1 Lancaster University – were seen to be broadly comparable, based on size, standing and characteristics. Appendix 1 provides background information about the two regions against which to situate the study. Both departments sit within universities aligned with the entrepreneurial university agenda. Through its strategy, EMLYON seeks to drive an entrepreneurial spirit and economic development in its regional environment and beyond (European Commission, Citation2015). Lancaster University’s priorities are teaching, research and engagement with the local community (Lancaster University, Citation2015). We made the choice to ‘uncover’ the cases to enable a discussion about regional economic development, for which it is necessary to understand the context of the regions we are discussing. It is impossible to hide the cases so respondents remain anonymous.

Our starting point was: ‘why are these two case studies interesting, and what can we learn more broadly from them?’ Part of the answer is their success and stature as leading departments within the field, and important contributors to the activities of their wider entrepreneurial universities. For example, IEED recently received an award from the ESRC (the UK funding body for social and economic research) for impact and engagement activities and EMLYON through, Alain Fayolle, was awarded the European Entrepreneurship Education Award (EEEA) 2013. Another reason is the common intent of the two departments to be excellent in research and education, in dialogue with local business and community. Also, the scale and scope of knowledge exchange and engagement activity alongside world-leading research and teaching is notable in the British and French academic contexts.

The two case studies were designed to be replicable so they could be compared and contrasted (Yin, Citation2003). Three approaches were used to generate data: observations, interviews and document analysis. These different data sources allowed for triangulation, ensuring the reliability of findings.

At the time of the study, the authors were employed in or affiliated with the two departments investigated. This offered excellent access to key individuals and ease in organizing interviews. A potential downside was positions and intimate knowledge meant our own pre-conceptions could influence respondents, or mean mis-interpreting data. So, a number of steps were taken to increase the objectivity of the research and remove as much as possible of our own biases. The first step was to carefully design interview schedules so all respondents across cases would be asked the same questions, both to reduce influencing the findings by asking leading questions and to enable cross-case comparison under each question. Recorded interviews were professionally transcribed. We used NVivo software to support analysis, and double-checked each other’s coding to make sure we captured themes and did not overlook important aspects through being ‘too close’ to respondents or data. We used the same analysis grid and worked iteratively across both sets of data so we could cross-reference emerging themes. By having four researchers working with the data, we could pick up a range of themes, and spot those missed by colleagues. Our well-structured and pre-formulated approach ensured replicability of the two case studies, and rigour of data collection and interpretation. Thus, throughout the research process, we remained theoretically sensitive (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967), neutral and non-judgemental.

Departmental, school and university documents painted a rich picture from a multi-level perspective. These were followed up by interviews with key actors ranging from strategic or managerial levels (e.g. Heads of Department) through to those implementing activities and programmes ‘on the ground’ (e.g. programme managers). Semi-structured interviews were preferred due to their ability to produce broadly comparable data, and keep conversations ‘on track’ to cover key themes being investigated, sometimes referred to as ‘topical’ interviews due to their structure around particular topics or issues (Simons, Citation2009). Respondents were asked to explain roles, activities undertaken, barriers faced, work with other actors within the department, university and region, and reflect on the changing nature of knowledge exchange. Due to the authors’ positions, observational and ethnographic methods were used to capitalize on this richness of knowledge and lived experience.

In keeping with standard procedures of inductive case study research (Leppäaho, Plakoyiannaki, & Dimitratos, Citation2015), information about each university was compiled as a case study. Individual cases were then examined for detail. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim and raw data from documents, field notes, observations pulled together before being reduced and sorted into descriptive categories and explanatory themes which fitted our research questions. Working through each case allowed comparison of potential themes and patterns across cases. We then refined themes into descriptive categories. Descriptive categories were then synthesized into analytical categories which explained what we were looking at when brought together (Bansal & Corley, Citation2012). Analysis was iterative with ideas emerging from data held up against the literature with the constant comparative approach providing a way to review data with emerging categories and concepts (Bansal & Corley, Citation2012).

provides interviewee details, numbers are used to differentiate between quotes in the paper. Each interview took around one hour. EMLYON interviews were conducted in French (later translated into English).

Table 2. Interviews conducted.

The IEED was founded in 2003 to achieve excellence in entrepreneurship research and teaching, underpinned by engagement with business. Entrepreneurship had been taught since the late 1980s and an Entrepreneurship Unit established in 1999 with teaching supported by research activity. Now there are over 40 staff and research and teaching runs alongside programmes of business engagement. EMLYON’s entrepreneurship department is an informal structure, part of UPR (Unit of Pedagogy and Research) Strategy and Organization. Since the mid-1980s, with the creation of the ‘Centre des entrepreneurs’, the department has focused on developing entrepreneurial mindsets among students and faculty members. Today, there is an emphasis on entrepreneurship education in all academic programmes and other activities, closely linked with the EMLYON Incubator. Since 2004, the school’s baseline is ‘Educating Entrepreneurs for the World’. Ten professors cover entrepreneurship; another 30–40 are involved in entrepreneurship education.

Findings

We identified a number of common roles and activities carried out by these entrepreneurship departments in terms of their broad third mission activities. Indeed, the similarity between them was initially surprising, although the exact programmes and activities differed, their underpinning and aims were very similar. To understand and theorize, and link back to the extant literature on entrepreneurial universities, we organized activities into six broad categories. We do not omit other streams of activity encountered in other entrepreneurship departments, but these represent the main functions of the departments we studied. While described as separate streams, these activities are not mutually exclusive; boundaries between them are blurred. These themes of activity have been conceptualized according to the roles and activities colleagues discussed as important, and reflect our understandings of the various and multi-faceted activities undertaken by the departments considered: educating the current and next generation of entrepreneurs, managers and innovators to increase the entrepreneurial capital of the region; providing programmes and services to businesses in the locality to enhance growth, resilience and vitality; playing leadership or governance roles in the region, and strengthening local economic networks through participation; conducting world class research into entrepreneurship (and associated areas), which underpin all activities; mobilizing and transferring entrepreneurial experience (Fayolle & Redford, Citation2014); creating an entrepreneurial culture. With these wider categories, a number of specific activities or programmes have been recognized, see , alongside insights garnered from interviews.

Table 3. Activities under key roles of entrepreneurship departments.

The overarching role of the entrepreneurship department is expressed as co-ordinating and applying management theory to real-world practice: ‘The application of the Management School to the outside world seems to focus through the Entrepreneurship Department … to apply wide management theory within the small business context and to the role of the individual as entrepreneur, or teams as entrepreneurs’ (E&R2). This is slightly different to the aim of entrepreneurial activity often highlighted in third mission studies, which is usually more to do with the transfer of knowledge in a more tangible sense, often revolving around a particular technology or development.

Perhaps the most fundamental similarity underpinning both departments is that all teaching and engagement activities are underpinned by research into entrepreneurship, and this is the key factor which sets entrepreneurship departments apart from the wider entrepreneurial university as a whole. The mission of the entrepreneurship department was articulated by senior managers: ‘One of the skills I would like most students to go out with … . Is an entrepreneurial mind-set … and bringing that together with working to help the region seems a very good place to be’ (SM1).

Both departments provide education for their own students and wider stakeholders in their region, such as businesses and entrepreneurs. There are also activities which aim to bring students and businesses together through placements in local (and regional, national and international) businesses in both departments, and present is the incorporation of entrepreneurs and practitioners into teaching: ‘We connect students with entrepreneurs and they must visit them in their companies and conduct “small” start-up missions. They must spend three hours a week for one month within the start-up and produce a final report’ (KE3).

Through such links many practical student and research projects have emerged, and this area of activity emerged as important from several interviewees but is little discussed in the extant literature; the role of students in carrying out projects and research emerges as a central form of engagement benefitting both company and students.

Both departments directly provide services or programmes to business and entrepreneurial communities, often underpinned by other public monies such as European Structural Funds or national sources of funding, leading to variations in the types of programmes according to the policy context within which departments operate. In Lancaster, a large stream of activity ‘the W2GH programme’ was achieved through the Regional Growth Fund from the UK government to develop the English regions; in France, the government is driving the establishment of incubators nationwide. These programmes are often driven by local, regional and national policy priorities and funding streams available; the exact formulation of support varies from place to place. An EMLYON academic explained:

We have requests that we receive from several external institutions … This may come from the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Lyon, which is very associated with the school, from regional incubators or from the Réseau Entreprendre … It is at their initiative, they wish to be associated with our research activities and they want to reinforce the communication between what we are doing and what they are doing. (T&R6)

A particular characteristic of the entrepreneurship department, which sets them apart from other departments within the university, is the way teaching, research and engagement come together. To better understand how these roles co-exist, participants were asked about research, teaching and knowledge exchange undertaken, and how they fit together in their experiences. The overlap between the three spheres certainly exists; research into entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial activity feeds into both teaching and engagement activities undertaken: ‘We’re using entrepreneurial learning techniques so its very action based, to deliver those programmes. So, that’s where the research comes in. More of it could come in for sure; and should’ (KE1);

The Entreprendre and Innover is a research-practical oriented journal. It’s a link between the entrepreneurship department and the outside world … it is a part of EMLYON. For several years, we organized with external institutions such as the Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Union of incubators, conferences and a special issue … which will be devoted to them and on problems that interest them. (T&R6)

I regularly make sure to integrate my research and others’ in my classes … I'm very, very interested in, what I call the ‘Evidence-Based Entrepreneurship Education’ and I ensure to develop lessons that rely increasingly on evidence coming from empirical studies that are link to important issues in education and training and should increasingly feed the lessons. (T&R6)

I would say that I'm afraid that good researchers shut you up in a small interesting intellectual world of ideas, concepts and theories. It makes you happy, but to me you lock yourself in a world that can and may become disconnected from the real world. (KE4)

Normally, as an academic, you’re expected to be quite good at teaching, research and any kind of industry relationships and knowledge exchange. However, a lot of reputable scholars say that you can normally only be good in two of three, because it’s so specialised. (T&R1)

Some felt KE activities, and research surrounding them, could feed into teaching more, and this could interest students. It was also felt the expertise of the entrepreneurship department could be better fed into university-wide enterprise services, open to all students and staff, and there is an opportunity for the department to contribute to the university here. There was some contrast in the views of teachers and students as to how well agendas overlap and feed into each other: ‘Today, it is essential to tighten very, very strong links between research in entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship broadly with educational practices and practices of actors engaged in incubation support structures, entrepreneurs, project developers, etc.’ (T&R6).

The specific measures and programmes put in place to support local economic growth varied across the departments, but were important to both. For example, EMLYON has its own incubator while IEED has a more organic, less structured approach to social incubation. The educating role of entrepreneurship departments certainly goes beyond training entrepreneurs, and staff involved in teaching highlighted the importance of entrepreneurial thinking and skills for all student career paths. The importance of training graduates who think entrepreneurially was highlighted as important for regional and national economies, and the role of the entrepreneurship department in economic terms is clearly articulated:

We have to compete on innovation, and I think that this type of mindset that entrepreneurship education graduates can bring companies can make the difference when it comes to taking the lead advantage of countries and regions that are more efficient in terms of costs’. (T&R1)

Analysis and discussion

To summarize the above into a more tangible conception of what third mission activities the entrepreneurship department undertakes, we return to and add our findings to what has been found by past research. In , we show established and extra dimensions of the entrepreneurial university.

Table 4. Established and extra dimensions of the entrepreneurial university.

Having identified key roles being played by entrepreneurship departments, the next stage of our analysis was to understand how these roles are enacted, and how entrepreneurship departments fit into the wider entrepreneurial university and the wider region. The interviews with colleagues undertaking different roles in the departments allowed us to gain a rich picture of who members of entrepreneurship departments are interacting with, how, and for what purpose. The result of analysing these discussions was to find a complex and multi-faceted model of engagement between the department, the university and the region. We found that entrepreneurship departments, while making up part of the wider ‘entrepreneurial’ university, and carrying out roles in this wider institutional capacity, can also be seen as regional actors in their own right, articulated thus: ‘I see [the entrepreneurship department] as being directly accountable for developing growth and jobs and bringing acumen and knowledge and capabilities and confidence in businesses and the region’ (SM 1). Entrepreneurship departments were also found to play a direct role in developing a regional strategy and working directly with government and policy-makers, what we conceptualize as playing a role in the governance of regional economic development (for a full discussion of this role, please see Pugh, Hamilton, Jack, & Gibbons, Citation2016).

Two routes through which the entrepreneurship department engages with the region are identified: formal routes, via the wider entrepreneurial university, are important for some activities; others are through more informal routes and direct to the region, bypassing the entrepreneurial university structures. We have represented these pathways visually in .

The entrepreneurial department has a complete value chain through a series of formal and informal activities that is more likely to impact a region (Dada et al., Citation2015; Perkmann et al., Citation2013). This channel covers a wide spectrum of activities including teaching, knowledge and skills development, dissemination of entrepreneurial spirit among students and executive managers (who are often entrepreneurs and CEOs in regional companies), incubation programmes and new venture creation and growth. All these feed, and are fueled by, research activities that produce new knowledge which fit regional needs and expectations. Entrepreneurship departments’ research activities are distinguished by applied economic and social purpose. They are mostly based on economic and social challenges emerging from the regional context. Furthermore, the departments evolve in a dialogic relationship with the region, in that interactions, engagement and knowledge exchanges flow: from department to region and from region to department (Hughes & Kitson, Citation2012; Lawton Smith and Bagchi-Sen, Citation2011; Perkmann et al., Citation2013; Power & Malmberg, Citation2008). The absorptive capacity of the region (in particular its firms) is a key here in how the activities of the entrepreneurial university are received and interacted with: we can see the impact of activities and their ‘use’ will be higher in regions with a greater absorptive capacity.

The region constitutes a ‘pool’, through all resources, infrastructures and facilities that it offers to the department members and students. The regional environment is developing and enriching the set of activities carried out within the department. For example, the department cooperates often in an informal way, with local SME networks to offer students the opportunity to work on real business projects. In addition, the region provides external infrastructures such as incubators, accelerators or venture capital organizations to help students in the earlier stage of their new venture creation process.

Furthermore, local entrepreneurs and managers are working jointly with entrepreneurship faculty to develop formal and/or informal teaching supports and coaching activities: such as mentoring, guest lecturing, entrepreneur’s testimonies and case studies. Moreover, the region funds and provides data and applied research projects to shed light on concerns of local actors and institutions, such as entrepreneurs, SME managers, incubators, science and technology parks and policy-makers. For example, several PhD projects were supported by Lyon Chamber of Commerce, regional incubators and regional network of entrepreneurs called ‘Réseau Entreprendre®’.

As well as within the region, there are also links to wider university structures to promote and facilitate regional engagement. Some activities take exclusively one or the other route, but others use a combination of formal and informal mechanisms. An illustrative example of this is student projects, where it was explained companies are often recruited through personal networks and informal links, but when student projects develop, the relationship becomes increasingly formalized and brought into the university’s structures for teaching and research. We can see the university structures often being bypassed in favour of more informal networking mechanisms, due to personal and professional relationships between staff and regional actors. These were described as the most effective way to increase the regional impact. Staff in both departments felt networks with regional actors outside the university were stronger and more important to their work, and both departments also felt it necessary to improve co-ordination between the entrepreneurship department and wider university.

Digging deeper into individual interlinkages illuminates a more complex picture than we would envision through simply referring to the ‘entrepreneurial university’. The formal links tend to be embedded within the procedures and structures of the university, but informal linkages to the region have a more complex structure, formation and enactment, and are often curated or developed by individuals. As such, they are not owned by the university, and are dependent on the existence of personal relationships. By employing social network analysis, we explored the mechanisms through which members create, nurture and utilize these relationships. The importance of networks and connection emerged time and again as a key factor underpinning all activity: ‘Unless you connect, you’re nobody’ (SM11).

Because relationships and connection are important to the activities undertaken, managing and building these links is a critical element of the work of department members, especially those in knowledge exchange. This is achieved through ‘an awful lot of hard work’ (KE1), through:

lots of personal links, databases, lots of relationship building with all those external people, bringing them in to see what we do, engaging and trying to build that relationship … We put on events, we run masterclasses … . Relationships take time, trust takes time. (KE1)

The means through which these connections are developed, maintained and operationalized for engagement are complex and multi-faceted. They are also heterogeneous and individual. However, by asking colleagues how they undertake daily tasks we could build a picture of how they go about networking with regional stakeholders (and to a lesser degree within the entrepreneurial university). Contacts are built and maintained by visiting local businesses, attending local networking events, inviting local entrepreneurs and businesses to events at the department, and setting up joint research projects with staff and students, all of which are extremely time-consuming activities. There is clearly no easy way to build up a strong regional network.

Overall, it is important to emphasize how important informal links to the region are to the entrepreneurship department’s work, and more formal structures of the entrepreneurial university, that have received more attention in the extant literature, can only explain a part of the entrepreneurship department’s third mission role.

Our results show a symbiotic effect between the entrepreneurship department and the region. On the one hand, the department plays a key role in developing entrepreneurial capital (Audretsch & Keilbach, Citation2008), through dissemination of an entrepreneurial spirit, entrepreneurship education, production of useful knowledge for entrepreneurs and finally, new venture creation and growth. On the other hand, the region fuels the entrepreneurship department’s activities by providing a favourable environment to teach, do research and incubate students’ projects.

Conclusions

This paper directly responds to a gap in the literature pertaining to entrepreneurial universities and their roles in regional economic development: the roles and activities undertaken by entrepreneurship departments. By exploring two case studies of large and active entrepreneurship departments which are embedded within their regions and engaged in research, teaching and practice, we highlighted a number of activities and roles undertaken which have been underexplored in past studies of entrepreneurial universities. It is not only in entrepreneurship departments that third mission and knowledge exchange activities have been overlooked (Audretsch, Citation2014), the same is true of other humanities and social sciences disciplines, but we might expect entrepreneurship departments to be at the vanguard of theorizing around the entrepreneurial university.

Overall, we found an interesting similarity between the two entrepreneurship departments studied in both the roles they take on and activities undertaken because their foundations are heterogeneous: that of linking up three main spheres to undertake research-led teaching and engagement in the field of entrepreneurship and to have a positive effect on their local, regional and national economies through their activities. Their activities have been categorized into six streams that capture these commonalities, thus creating a framework which can be used to analyse activities and roles played by entrepreneurship departments within their regions. We explore how entrepreneurship departments act both within and beyond the wider ‘entrepreneurial university’ in their regions, and how these roles vary according to different streams of activity. Simply conceptualizing entrepreneurship departments as an element of the entrepreneurial university obscures and underplays their importance as regional actors, and may in fact miss the bulk of the engagement and impact achieved. Given the duality of their roles, and the complexity of links between entrepreneurship departments, the entrepreneurial university as a whole, and the region, we call for a more nuanced understanding of the entrepreneurial university and the components comprising it.

By mapping out knowledge exchange activities undertaken in entrepreneurship departments, this paper has found a number of ‘extra’ roles and functions as yet underexplored in the literature, see . It also found activities taking place in entrepreneurship departments that have been found in other departmental contexts by past research. Equally, there are a number of roles and activities well researched in the literature, usually more ‘formal’ or ‘hard’ activities, which were not found to be taking place in entrepreneurship departments, suggesting that they are not universally important to the entrepreneurial university’s work. It is hoped that by highlighting the extra activities, and questioning the importance of well-established mechanisms, such as spinout and licensing, this paper helps the agenda of broadening our conceptualization of what the entrepreneurial university is, what it does and how it relates to its region.

On the subject of regional interaction, this paper examined routes via which the entrepreneurship department engages with its region, and found two paths. We disagree with a linear model whereby departments feed into the university, which then engages with the region, and we support the growing research agenda of looking at universities regional roles more broadly (see Dada et al., Citation2015; Power & Malmberg, Citation2008), and at engagement as a two way street between the university and the region (Johnstone & Huggins, Citation2016). As such, our visualization of the entrepreneurship department’s roles is cyclical, with feedbacks to and fro. We propose a framework that conceptualizes these two routes to engaging with the wider region: one goes through the university structures, as part of the so-called entrepreneurial university, and another bypasses them. This leads to the question of what we mean by the ‘entrepreneurial university’, because if we take the university as a whole, this misses out a significant proportion of engagement that is taking place.

We are aware of the limitations of drawing wider conclusions from two case studies, however, as a foundation they allowed us to illicit interesting discussions about the roles of entrepreneurship departments within the entrepreneurial university in line with the exploratory aims originally outlined. Through considering linkages involved in the entrepreneurship departments’ roles and activities, we found activities and functions which bring businesses and entrepreneurs ‘in’ to the university equally important in creating a wider entrepreneurial ecosystem and culture as those activities driven ‘out’ of the department to local businesses. Not all of the entrepreneurship department’s roles are enacted on a regional level, its impact can be national or international. Evidence from Lancaster and EMLYON suggests some entrepreneurship departments play on a global stage, and staff are collaborating and interacting with businesses and other institutions worldwide.

Entrepreneurship departments are sitting in a particular niche within and beyond the entrepreneurial university of providing teaching and engagement that is underpinned by research into entrepreneurship. Interactions with their regions flow both ways, with a high degree of direct relationships between department members and regional entrepreneurial actors. Entrepreneurship departments are carrying out a wide range of third mission activities, both formal and informal, which makes it all the more surprising that they have been largely overlooked in the entrepreneurial university debate to date. This paper calls for a reversal of that trend, and sets the ground for further investigation into entrepreneurship departments, and indeed other types of departments not yet captured in the literature, as key drivers of regional economic development within and beyond the concept of the entrepreneurial university.

Appendix_1.docx

Download MS Word (18.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The department is now named DESI – Department of Entrepreneurship, Strategy and Innovation – following a merger of the two previously separate IEED and Strategy departments. At the time of research, they were separate and we interviewed only members of IEED.

References

- Abreu, M., & Grinevich, V. (2013). The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: Widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities. Research Policy, 42(2), 408–422. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.10.005

- Acs, Z., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30. doi: 10.1007/s11187-008-9157-3

- Audretsch, D. (2014). From the entrepreneurial university to the university for the entrepreneurial society. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(3), 313–321. doi: 10.1007/s10961-012-9288-1

- Audretsch, D., & Keilbach, M. (2008). Resolving the knowledge paradox: Knowledge-spillover entrepreneurship and economic growth. Research Policy, 37(10), 1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2008.08.008

- Baldini, N., Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., & Sobrero, M. (2014). Organisational change and the institutionalisation of university patenting activity in Italy. MINERVA, 52, 27–53. doi: 10.1007/s11024-013-9243-9

- Bansal, T., & Corley, K. (2012). From the editors: Publishing in AMJ – part 7: What’s different about qualitative research? Academy of Management Journal, 55(3), 509–513. doi: 10.5465/amj.2012.4003

- Bienkowska, D., & Klofsten, M. (2012). Creating entrepreneurial networks: Academic entrepreneurship, mobility, and collaboration during PhD education. Higher Education, 64(2), 207–222. doi: 10.1007/s10734-011-9488-x

- Bramwell, A., & Wolfe, D. (2008). Universities and regional economic development: The entrepreneurial University of Waterloo. Research Policy, 37(8), 1175–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2008.04.016

- Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128. doi: 10.2307/2393553

- Cooke, P. (2016). The virtues of variety in regional innovation systems and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 2(1), 1–19. doi: 10.1186/s40852-016-0036-x

- Dada, Olufunmilola (Lola), Jack, Sarah, & George, Magnus. (2015). University–business engagement franchising and geographic distance: A case study of a business leadership programme. Regional Studies, 50(7), 1217–1231. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.995614

- Di Gregorio, D., & & Shane, S. (2003). Why do some universities generate more start-ups than others? Research Policy, 32(2), 209–227. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00097-5

- Drucker, J., & Goldstein, H. (2007). Assessing the regional economic development impacts of universities: A review of current approaches. International Regional Science Review, 30(1), 20–46. doi: 10.1177/0160017606296731

- Etzkowitz, H. (2003). Research groups as ‘quasi-firms': The invention of the entrepreneurial university. Research Policy, 32(1), 109–121. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00009-4

- Etzkowitz, H., Webster, A., Gebhardt, C., & Terra, B. (2000). The future of the university and the university of the future: Evolution of ivory tower to entrepreneurial paradigm. Research Policy, 29, 313. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00069-4

- European Commission Report. (2015). “Supporting the Entrepreneurial Potential of Higher Education – Final report –version 1.1”. (Authors: Stefan Lilischkis, Christine Volkmann, Marc Gruenhagen, Kathrin Bischoff and Brigitte Halbfas). http://sephe.eu/fileadmin/sephe/documents/sephe_final-report_2015-06-30_v1.10.pdf

- Fayolle, A., & Redford, D. (2014). Introduction: Towards more entrepreneurial universities - myth or reality? In A. Fayolle & D. Redford (Eds.), Handbook on the entrepreneurial university (pp. 1–10). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Feldman, M., Feller, I., Bercovitz, J., & Burton, R. (2002). Equity and the technology transfer strategies of American Research Universities. Management Science, 48(1), 105–121. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.48.1.105.14276

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine.

- Goddard, J., & Vallance, P. (2013). The University and the City. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Gordon, I., Hamilton, E., & Jack, S. (2012). A study of a university-led entrepreneurship education programme for small business owner/managers. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(9-10), 767–805. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2011.566377

- Guerrero, M., Cunningham, J., & Urbano, D. (2015). Economic impact of entrepreneurial universities’ activities: An exploratory study of the United Kingdom. Research Policy, 44(3), 748–764. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2014.10.008

- Hughes, A., & Kitson, M. (2012). ‘Pathways to impact and the strategic role of universities: New evidence on the breadth and depth of university knowledge exchange in the UK and the factors constraining its development’. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 36(3), 723–750. doi: 10.1093/cje/bes017

- Jack, S., Moult, S., Anderson, A., & Dodd, S. (2010). An entrepreneurial network evolving: Patterns of change. International Small Business Journal, 28(4), 315–337. doi: 10.1177/0266242610363525

- Johnstone, A., & Huggins, R. (2016). Drivers of university–industry links: The case of knowledge-intensive business service firms in rural locations. Regional Studies, 50(8), 1330–1345. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1009028

- Klofsten, M., & Jones-Evans, D. (2000). Comparing academic entrepreneurship in Europe – The case of Sweden and Ireland. Small Business Economics, 14(4), 299–309. doi: 10.1023/A:1008184601282

- Kolympiris, C., Kalaitzandonakes, N., and Miller, D. (2015). Location choice of academic entrepreneurs: Evidence from the US biotechnology industry. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 227–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.02.002

- Lancaster University. (2015). Creating a Global University; our strategy to 2020. Retrieved from https:/www.lancaster.ac.uk/strategic-plan/

- Larty, J., Jack, S., & Lockett, N. (2016). Building regions: A resource-based view of a policy-led knowledge exchange network. Regional Studies, 51(7), 994–1007. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1143093

- Leppäaho, T., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Dimitratos, P. (2015). The case study in family business: An analysis of current research practices and recommendations. Family Business Review, 29(2), 1–15.

- Martinelli, M., Meyer, M., & von Tunzelmann, N. (2008). Becoming and entrepreneurial university? A case study of knowledge-exchange relationships and faculty attitudes in a medium-sized, research-oriented university. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 33(3), 259–283. doi: 10.1007/s10961-007-9031-5

- Mian, S. (2011). University’s involvement in technology business incubation: What theory and practice tell us? International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 13(2). doi: 10.1504/IJEIM.2011.038854

- Perkmann, M., Tartarik, V., McKelvey, M., Autio, E., Broström, A., D’Este, P., … Sobrero, M. (2013). Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Research Policy, 42(2), 423–442. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.09.007

- Phan, P., Siegel, D., & Wright, M. (2005). Science parks and incubators: Observations, synthesis, and future research. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(2), 165–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.12.001

- Power, D., & Malmberg, A. (2008). The contribution of universities to innovation and economic development: In what sense a regional problem? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 1, 233–245. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsn006

- Pugh, R., Hamilton, E., Jack, S., & Gibbons, A. (2016). A step into the unknown: Universities and the governance of regional economic development. European Planning Studies, 24(7), 1357–1373. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1173201

- Rose, M., Decter, M., Robinson, S., Jack, S., & Lockett, N. (2012). Opportunities, contradictions and attitudes: The paradox of university- business engagement since 1960. Business History, 55(2), 259–279. doi: 10.1080/00076791.2012.704512

- Rothaermel, F., Agung, S., & Jiang, L. (2007). University entrepreneurship: A taxonomy of the literature. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(4), 691–791. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtm023

- Simons, H. (2009). Case study research in practice. London: Sage.

- Smith, Lawton S., & Bagchi-Sen, S. (2011). The research university, entrepreneurship and regional development: Research propositions and current evidence. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(5–6), 383–404. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2011.592547

- Spigel, B. (2017). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49–72. doi: 10.1111/etap.12167

- Uyarra, E. (2010). Conceptualizing the regional roles of universities, implications and contradictions. European Planning Studies, 18(8), 1227–1246. doi: 10.1080/09654311003791275

- Van Burg, E. (2014). Commercializing science by means of university spin-offs: An ethical review. In A. Fayolle & D. T. Redford (Eds.), Handbook on the entrepreneurial university (pp. 346–359). Edward Elgar: Chltenham.

- Wright, M., Piva, E., Mosey, S., & Lockett, A. (2009). Academic entrepreneurship and business schools. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 34, 560–587. doi: 10.1007/s10961-009-9128-0

- Yin, R. (2003). Case study research design and methods, 3rd ed. London: Sage.