ABSTRACT

New industrial innovation policies like smart specialization aim at boosting economic growth by diversification towards more complex and higher value economic activities. This paper proposes a conceptual and analytical framework to support the design and implementation of such policies considering place-specific preconditions, particularly the differentiation of the regional system of innovation and entrepreneurship and the degree of current industrial diversification. The paper expands on the links between these preconditions and the barriers and opportunities for industrial diversification. Consequently, it proposes an archetypical place-based policy framework covering overall policy objectives as well as measures at the level of actors, networks, and the institutional and organizational support structures.

1. Introduction

The objective of this paper is to develop a conceptual and analytical framework aimed at supporting the design and implementation of place-based entrepreneurship and innovation policies that drive what Foray calls ‘positive structural changes’ (Foray, Citation2017, p. 38), i.e. promoting regional industrial diversification and future competitiveness, leading to economic growth and new job generation. Such policies represent a new industrial innovation policy pursuing a high road strategy of innovation-based competition as the sustainable alternative to a downward spiral of cost competition (i.e. the low road strategy) (Milberg & Houston, Citation2005).

New industrial innovation policies are characterized by the following (Radosevic, Citation2017, p. 9):

No single agent has a total overview of the economy.

Its key feature is designing a policy process that leads to the ‘discovery’ of new specializations.

Policy making is an endogenous factor in the design and implementation of industrial innovation policy facilitating the process of self-discovery by agents.

Radosevic (Citation2017) considers smart specialization (S3) as the EU’s version of new industrial innovation policy. Smart Specialization is probably the single largest attempt ever of an orchestrated, supranational innovation strategy to boost economic growth through economic diversification and new path development, e.g. diversify the economy into technologically more advanced activities that move up the ladder of higher knowledge complexity compared to the present level in the region (Asheim, Grillitsch, & Trippl, Citation2017). In the words of Landabaso (Citation2014, p. 378), then Head of Unit in the EC responsible for S3, it is ‘a process of priority-setting in national and regional research and innovation strategies in order to build “place-based” competitive advantages and help regions and countries develop an innovation-driven economic transformation agenda.’

The aim is to plan for economic diversification in a short and medium term as well as a long term perspective to promote more fundamental structural changes in the economy through transformative activities. S3 represents an explicit, placed-based approach, emphasizing prioritization and selectively through non-neutral, vertical policies, and thereby acknowledging the large variations in regional pre-conditions and policy challenges as regards promoting innovation, competitiveness and growth (Barca, McCann, & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2012; Camagni & Capello, Citation2013; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2005). Furthermore, S3 – for the first time in the EU’s history – provides a policy framework or platform for promoting and implementing a broad based innovation policy (Asheim, Boschma, & Cooke, Citation2011; Cooke, Citation2007, Citation2012). In the words of the European Commission (Citation2014, p. 2) S3 ‘supports technological as well as practice-based innovation’.

This new perspective on innovation policy was not, however, in the light of the dominating linear view of the EU, immediately understood by all policy makers and practitioners. Thus, especially in the first phase of regions’ design and implementation of S3, one can find examples of regions that viewed S3 as more of the same traditional linear, R&D based policy. However, this new view of DG Regio of the necessity of applying a broad based approach to cope with the innovation challenges found in the heterogeneity of EU regions was based on theoretical and empirical based policy reflections presented in e.g. the Constructing Regional Advantage report from 2006 (Asheim et al., Citation2011) as well as the Barca report from 2009 (Barca, Citation2009). Both these reports emphasized that a one size fits all, horizontal, R&D based innovation policy is not sufficient to promote job creation and economic development in the majority of EU regions, and argued for a place-based and region specific, vertical policy that built on the existing strengths and capabilities in the regions. Today Foray, one of the fathers of the smart specialization approach, maintains that ‘there are an infinite number of potential innovations, which are context-, sector-, and region-specific, and which will never be invented in Silicon Valley!’ (Foray, Citation2017, p. 47).

Smart specialization is not about ‘specialization’ as known from previous regional development strategies, i.e. a Porter-like, sector specialized cluster strategy, but about diversified specialization. What this means is that countries should identify strategic sectors – or ‘domains’ – of existing and/or potential competitive advantage, where they can specialize and create capabilities in a diversified (different) way compared to other countries and regions (Asheim et al., Citation2017). This contrasts what Foray (Citation2009, p. 20) identified as main shortfall of European innovation policy, namely that ‘the uniformisation of priorities leave Europe with a collection of subcritical systems, all doing more or less the same thing, systems which are unattractive and thus cannot play in the arena of the world localisation tournament.’

‘Smart’ in the smart specialization approach refers to the identification of these domains of competitive advantage through what is called the ‘entrepreneurial discovery’ process. Foray (Citation2014, p. 495) defines entrepreneurial discovery as a process of ‘deployment and variation of innovative ideas in a specialised area that generate knowledge about the future economic value of a possible change.’ However, the emphasis here is not on the role of traditional entrepreneurs, resulting in a policy focus only on firm formation and start-ups as an individual entrepreneurial project. As underlined in the writings on smart specialization, ‘entrepreneurial’ should be understood broadly to encompass all actors including innovative (Schumpetarian) entrepreneurs at the firm and company level (Schumpeter, Citation1911; Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000), institutional entrepreneurs at universities and in the public sector (Battilana, Leca, & Boxenbaum, Citation2009; Sotarauta & Suvinen, Citation2018), and place leadership (Gibney, Copeland, & Murie, Citation2009; Sotarauta, Beer, & Gibney, Citation2017) at the regional level that have the capacity and entrepreneurial mindset to discover domains for securing existing and future competitiveness (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2018). Such a broad interpretation of ‘entrepreneurial discovery’ resonates well with systemic approaches to innovation and regional development (Asheim & Gertler, Citation2005; Asheim & Isaksen, Citation2002; Cooke, Citation1992; Doloreux, Citation2002; Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, Citation2000; Morgan, Citation1997; Morgan & Cooke, Citation1998; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2005) The systems approach to innovation also highlights the role of government and public policy in driving innovation, as well as the balance between exploration and exploitation (Asheim, Grillitsch, & Trippl, Citation2016).

This paper thus aims at developing a place-based entrepreneurship and innovation policy framework for regional industrial diversification. This framework will help to identify opportunities for regional industrial diversification in different types of regions, main barriers for promoting new industrial growth paths, and policy recommendations to strengthen the regional environment for entrepreneurship and innovation. The paper progresses in three sections. Section 2 develops the conceptual framework. Section 3 discusses the policy implications that can be derived from the conceptual framework. Section 4 concludes with reflections about the analytical process leading to the design of and recommendation for entrepreneurship and innovation policies.

2. Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework aims at identifying the relationships between regional characteristics, barriers for industrial diversifications, and the most promising forms of new industrial path development. In order to achieve this, Section 2.1 introduces a differentiated perspective on new industrial path development and Section 2.2 discusses the regional pre-conditions for such processes to happen. Based on these foundations, Section 2.3 elaborates on place-based opportunities and barriers for regional industrial path development.

2.1. Typology of industrial path development

Industrial path development and regional diversification have recently become a core theme in the literature (Boschma, Coenen, Frenken, & Truffer, Citation2017; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2016; Martin, Citation2010; Neffke, Henning, & Boschma, Citation2011). Industrial path development comes in many shapes, which renders futile a ‘one policy fits all’ approach to industrial path development (Grillitsch & Trippl, Citation2016; Isaksen, Tödtling, & Trippl, Citation2016). Three broad categories of new industrial path development can be distinguished: upgrading, diversification, and the emergence of new regional industrial paths (see ).

Table 1. Types of new regional industrial path development.

Upgrading of existing industrial paths makes a qualitative change to existing industries and is in some regional settings the most feasible way to enhance competitiveness and foster economic growth. Upgrading can take several forms. Climbing the hierarchy in global production networks (GPN) refers to enhancing the position of the regional industry towards higher value added activities through upgraded skills and production capabilities. Renewal refers to a major change of the existing industry due to the introduction of new technologies, change of business models, or organizational innovations. Industries can also enhance growth by moving into higher value added niches based on symbolic knowledge. This refers, for instance, to the generation of value through design and branding of traditional products, which makes it possible for high-income regions to compete in low-tech industries (e.g. design furniture from Denmark).

Diversification refers to firm-level processes where knowledge and resources from existing industries are used in new industries. In this regard, the literature differentiates between related and unrelated variety (Frenken, Van Oort, & Verburg, Citation2007). Related variety refers to different industries that build on similar types of knowledge. Diversification based on related variety is a process where entrepreneurs re-use core competencies in new industries. Diversification based on related variety is seen as fundamental mechanism in evolutionary economic geography (Frenken & Boschma, Citation2007). For instance, the maritime industry may re-use competences about the installation of oil platforms to the installation of offshore wind parks and thereby move into the renewable energy sector.

Diversification based on unrelated variety implies that entrepreneurs from existing industries combine their knowledge with dissimilar knowledge from other industries or knowledge providers (Grillitsch, Asheim, & Trippl, Citation2017). A conceptual basis for unrelated knowledge combinations can be found in the differentiated knowledge base approach, which distinguishes between analytical (science based), synthetic (engineering based), and symbolic (design based) knowledge (Asheim, Citation2007). Innovations with a high degree of novelty typically rest on the combination of unrelated types of knowledge and are the source for new industrial path development based on unrelated diversification (Asheim et al., Citation2011; Strambach & Klement, Citation2012). One example is the creation of fashionable, functional foods based on the combination of knowledge from the food industry (synthetic knowledge), biotechnology (analytical knowledge), and design (symbolic knowledge). In general, Key Enabling Technologies (KET) can be an important unrelated knowledge source for this type of diversification.

Finally, new industries may emerge in regions that are unrelated to existing industries. The most radical form of new path development is the creation of completely new industries. Sources for path creation are new technologies, scientific breakthroughs, or radical innovations based on new business models, user-driven or social innovations. From a regional perspective, it is also possible that an industry emerges that is new to the region but not new to the world, which is labelled as importation of an industrial path. Path importation rests on the inflow of actors and resources from outside the region.

2.2. Regional pre-conditions for industrial path development

In defining regional pre-conditions for industrial path-development, this paper draws on systemic approaches to innovation and entrepreneurship, in particular the regional innovation systems approach, which has a long tradition of developing regional typologies based on structural characteristics and policy challenges (Asheim et al., Citation2016). However, it is often difficult to relate empirical cases to the respective types. For this reason, this section elaborates a more fine-grained evaluation framework for the differentiation of the regional system of innovation and entrepreneurship (see ). In particular, it is acknowledged that such systems comprise many aspects, each of which deserve specific attention in empirical contexts. The evaluation framework builds on three fundamental system properties: actors, networks and institutions.

Table 2. Differentiation of systems of innovation and entrepreneurship.

As regards actors, a qualitative and quantitative dimension can be distinguished (Grillitsch & Asheim, Citation2016). The former captures the capabilities of regional actors, which refers among others to the use of cutting-edge knowledge and technologies, high resource endowment and financial capabilities. High capabilities imply that actors perform high-value and high skill activities. The quantitative dimension refers to the scope and scale of actors present. A variety of actor types (scope) contributes to and provides resources for innovation and entrepreneurship. Van de Ven, Polley, Garud, and Venkataraman’s (Citation1999) broad interpretation of entrepreneurship as one type of leadership along the ‘innovation journey’ resonates with the smart specialization approach, which propagates the inclusion of the business sector, higher education institutes, public administration as well as the civil society. Following Van de Ven (ibid.), entrepreneurship is exercised by a core network of interacting actors comprising firms, universities, public research organizations and government institutions and, especially in small regions, non-local actors. This broad interpretation is a key feature of systemic approaches to innovation and entrepreneurship highlighting in addition the importance of support organizations such as incubators, science parks, cluster organizations, etc. (Autio, Citation1998; Doloreux & Parto, Citation2005) as well as high-growth start-ups, serial entrepreneurs, banks, business angle groups, and venture capital firms (Mason & Brown, Citation2014). Scale refers to the number of actors and size of organizations present in the region. A system with a high level of differentiation as regards actors would imply that the region is endowed with a large number of variegated, and highly capable actors. In the literature, this constituent of system differentiation has been captured as organizational thickness (Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2016; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2005).

As regards networks, systemic approaches to innovation and entrepreneurship highlight the importance of localized learning (Malmberg & Maskell, Citation2006) both within sectors as well as across sectors. Within sectors this corresponds for instance to user-producer interaction and user-driven innovation (Lundvall, Citation1988; von Hippel, Citation2005). As regards new path development and more radical innovation, there is, however, increasing evidence that networks between sectors play an important role. This refers to interactions between industry, research, public services, and civil society (Carayannis & Rakhmatullin, Citation2014; Cooke & Morgan, Citation1994; Etzkowitz, Citation2012) as well as to interactions between different industries (Asheim et al., Citation2011). Such networks between sectors create opportunities for novel combinations of knowledge and resources (Grillitsch, Citation2016). Furthermore, regions are conceptualized as open systems, which are embedded in a national and international context (Asheim et al., Citation2016). Local and global networks are both of complementary as well as compensatory nature. Local learning dynamics benefit from the inflow of knowledge from the global scale (Bathelt, Malmberg, & Maskell, Citation2004). Firms also tend to be more innovative when combining knowledge from different scales (Tödtling & Grillitsch, Citation2015) and an overreliance on local sources may create lock-in and reduce innovativeness (Fitjar & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2011; Westlund & Kobayashi, Citation2013). In addition, extra-regional networks are a way to compensate for a lack of knowledge available regionally (Grillitsch & Nilsson, Citation2015; Shearmur & Doloreux, Citation2016). High system differentiation is thus characterized by a combination of networks within and between sectors, as well as regional and global embeddedness.

From an institutional perspective, system differentiation also includes a number of factors. Building a fundament for regional development, the quality of governance influences the innovativeness in regions as well as the effectiveness of policy instruments (Charron, Dijkstra, & Lapuente, Citation2014; Rodríguez-Pose & Di Cataldo, Citation2015). Quality of governance refers among others to low corruption, impartial public services and rule of law. More specifically, the regional innovation systems literature points to the pervasive influence of policy and regulations (Asheim, Citation2007; Cooke, Citation1992). Morgan (Citation2016) illustrates how policy repertoires are stable over time and are a major factor for diverging economic performance in regions that otherwise have similar preconditions. This points to the necessity of adapting the support systems to the region-specific needs and opportunities. Another important institutional aspect refers to governance processes. Recent policy approaches to regional innovation and entrepreneurship emphasize a complex governance process covering multiple-scales (local, regional, national, international), multiple-actor coordination, as well as the importance of bottom-up processes. According to the smart specialization approach entrepreneurial discoveries should inform policy priorities in bottom-up processes, interregional connectedness and cooperation, as well as the engagement of civil society and consumers in order to address major societal challenges (EC, Citation2012). Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2018) suggest that such bottom-up governance processes for regional structural change rest on the interplay of and synergies between the ‘trinity of change agency’: innovative entrepreneurs (chasing opportunities to create value), institutional entrepreneurs (working towards institutional change), and place leadership (promoting local interests, mobilize and pool resources). Furthermore, region-specific cultural aspects influence innovation and entrepreneurship. This refers in particular to the notion of an entrepreneurial culture, which finds expression among others in a low degree of risk aversion and a high rate of new-firm formation (Davidsson & Wiklund, Citation1997; Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2014; Lee, Florida, & Acs, Citation2004), as well as openness to development and insights from outside the region (Fitjar & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2011; Westlund & Kobayashi, Citation2013). System differentiation thus results from high quality of governance, adequate policy repertoires, multi-level policy processes, and the existence of an entrepreneurial culture.

The second dimension for determining regional pre-conditions refers to the industrial profile. There has been a long debate in economic geography on the virtues of specialization and diversity. Specialization in one industry can be understood as a cluster (Porter, Citation1998, Citation2000) with strong traded and untraded interdependencies between related firms and organizations (Storper, Citation1995). Storper, Kemeny, Makarem, and Osman (Citation2016) argue for the importance of distinguishing between specialization in growing and dynamic industries versus specialization in mature and declining industries. The former are the major source for superior economic growth in core regions. As industries mature, lower-skilled production relocates to more peripheral regions. Also, industrial diversification is typically not a top policy priority if regions are specialized in a dynamic and growing industry. In contrast, industrial diversification and renewal is the main policy objective in stagnating regions with a specialization in older industries (Hassink, Citation2010; Trippl & Otto, Citation2009).

As regards diversity, evolutionary scholars have introduced a debate on the contributions of related and unrelated variety to economic growth (Frenken et al., Citation2007; Neffke et al., Citation2011). The related variety proponents argue that ‘inter-industry spillovers occur mainly between sectors that draw on similar knowledge […] (about technology, markets, etc.).’ (Content & Frenken, Citation2016, p. 1). Consequently, firms mainly diversify into technologically related products. Unrelated variety, in contrast, refers to industries that do not share similar knowledge. In particular when discussing industrial diversification and industrial path creation, the combination of unrelated knowledge is thought to be of high importance (Boschma et al., Citation2017; Grillitsch et al., Citation2017). Thus, while related diversification may be the rule, the rarer but more radical forms of industrial path development often involve unrelated knowledge combinations.

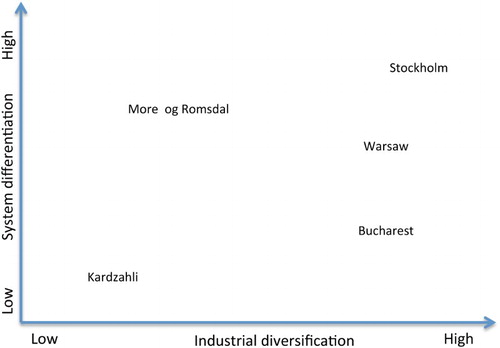

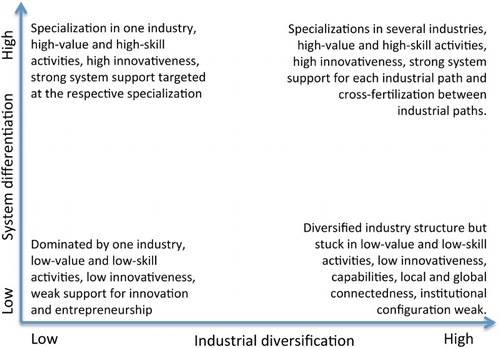

The two dimensions – system differentiation and industrial diversification – are continuous and any empirical case needs to be evaluated on a continuous scale (see ). At the lower end of system differentiation, regions will exhibit low-value and low-skill industrial activities, and low levels of innovation. Such regions may be dominated by one industry (typically small peripheral regions) or be relatively diversified (typically urban centres in less developed countries). In the latter case, it may even be possible that many of the actor types supporting innovation and entrepreneurship are present but their capabilities, local and global connectedness, and institutional configurations are weak. At the higher end of system differentiation, high-value and high-skill activities are pursued with a high level of innovativeness. If such regions are dominated by one industry, they typically have a support system for innovation and entrepreneurship that is targeted at the respective sector. On the other hand, regions with a differentiated system for innovation and entrepreneurship and a high degree of industrial diversification can be best understood as regions that have developed a variety of strong specializations or, in other words, a variety of strong industrial paths. Due to the required critical mass for developing strong industrial paths, thick and diversified regions are found in larger urban areas. In such regions, the system for innovation and entrepreneurship is supportive for each industrial path as well as for cross-fertilization between paths.

Figure 1. Representation of regional pre-conditions along two dimensions – system differentiation and industrial diversification.

In , we provide an illustration of how the analytical framework can be applied. We do not provide findings of in-depth case studies but rather showcase the applicability of the framework in terms of positioning regions relative to each other. The five exemplary cases are Stockholm (Sweden), Warsaw (Poland), Bucharest (Romania), Kardzahli (Bulgaria), and More og Romsdal (Norway). Stockholm, Warsaw and Bucharest are national capitals of roughly similar size in terms of population. The three regions are characterized by a relative high variety of industrial / economic activities and can thus be positioned on the right-hand side of . Also, the three regions exhibit similarities as regards the quantitative characteristics of system differentiation: All host the countries’ highest governmental functions, top universities, and leading business functions. However, when assessing system differentiation in qualitative terms clear differences can be noted with Stockholm ranking highest, followed by Warsaw and Bucharest. In the scope of this paper, we cannot go much beyond the authors judgment, which, however, is backed by the Regional Innovation Scoreboard (European Commission, Citation2017) identifying Stockholm as the most innovative region in the European Union, Warsaw as moderate innovator and Bucharest as modest innovator. The other two regions exhibit a less diversified industrial structure. Kardzahli is a province in southern Bulgaria. According to the National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria (Citation2018), more than 40% of employment was in agriculture in 2016. Due to untouched nature (thanks to low industrial activities) and location in the picturesque Rhodope Mountains, potential has been identified in tourism, which has, however, not yet materialized. Besides the low degree of industrial diversification, it does not need many words to conclude that the level of system differentiation is low, both in quantitative and qualitative terms. No high-level government, business, or educational functions are located in the region and the educational level is low (Institute for Market Economics, Citation2017). According to this rough assessment, Kardzahli would be positioned in the lower left-hand corner of . More og Romsdal is a region located at the North Sea in western Norway. It is home to one of the world’s leading maritime clusters, which has shown strong economic performance, at least until the drop in oil prices in 2014. In this field of specialization, More og Romsdal has developed unique capabilities at the level of firms, specialized higher education institutes, and governance support, which allow for a high-speed of incremental innovations. Although this suggests a high level of system differentiation, it does not rival Stockholm because of among others the lack of leading universities and a strong presence of public functions. As regards industrial diversification, More og Romsdal exhibits – compared to for instance Stockholm – a low level. Yet it’s industrial diversification is higher than the one of Kardzahli because of the presence of some other industries such as marine or furniture (Asheim et al., Citation2017). This allows us to position More og Romsdal in somewhat below Stockholm and right of Kardzahli.

This empirical illustration – based on a crude analysis – shows how the framework can be used to position regions in relation to each other. Needless to say that each empirical case needs a thorough analysis to identify the real challenges and derive policy recommendations considering all the elements of innovation systems as summarized in . In the next section, we discuss place-based opportunities and barriers for industrial path development by focusing on the four ‘stylized’ types of regions i) high system differentiation and high industrial diversification, ii) high system differentiation and low industrial diversification, iii) low system differentiation and high industrial diversification, and iv) low system differentiation and low industrial diversification.

2.3. Place-based opportunities and barriers for industrial path development

The regional context shapes the opportunities for new industrial path development (Grillitsch & Trippl, Citation2016). In this section, the opportunities and barriers for new industrial path development are discussed depending on the regional pre-conditions. As regards the barriers, a distinction is made in barriers for breaking with existing paths and barriers for growing new paths (see ).

Regions with low system differentiation lack a critical mass of strong actors in any particular field by definition. This implies that entrepreneurs in thin regions cannot draw on regional sources for combining related or unrelated knowledge. Also, entrepreneurs in thin regions are deprived of strong systemic support for innovation and entrepreneurship. Given these preconditions, the more challenging and novel forms of new industrial path development are often out of reach for such regions. Diversification into new industries would imply that the already thin resources are spread even thinner. The creation of completely new industries typically rests on a variety of high-level competences that need to come together. Lacking one of these may obstruct the creation of a new industry (Sotarauta & Heinonen, Citation2016). Thus, even though exceptions may prove the rule (Simmie, Citation2012), the creation of new industries will be unfeasible in regions with low system sophistication. Thus, the most feasible options are path upgrading and importation. Path upgrading includes moving into higher-value added niches, climbing the hierarchy in value chains, and renewing the industry by introducing new technologies and business models. Path importation rests on extra-regional sources of knowledge and resources, which are anchored in the region. This includes both direct investments as well as the inflow of people (Trippl, Grillitsch, & Isaksen, Citation2017).

In many ways, path upgrading and path importation are closely related to increasing regional system differentiation. This includes increasing capabilities of local actors, enhancing the positions of local actors in global networks, and strengthening institutional configurations. The main challenge resembles a catch-22 situation. Actors need extra-regional linkages to compensate for the lack of knowledge and resources available locally (Grillitsch & Nilsson, Citation2015). However, in order to access knowledge and resources through extra-regional networks, it is necessary that the regional actors have the capability to identify sources of relevant knowledge, establish knowledge transfer mechanisms (e.g. collaborations, recruitment), and absorb new knowledge. Hence, path upgrading will need to work simultaneously at enhancing actors’ capabilities and network embeddedness. There are some differences between regions with low and high industrial diversification. While for the former variety and capability of actors is an issue, the latter only suffer from a lack of capabilities.

As regards breaking with existing paths, the probably most important issue is a pervasive institutional weakness that may relate to all aspects highlighted previously (good governance, adequate policy repertoires, governance processes, and regional culture). The presence of influential incumbent players is a potential barrier in particular for regions with low industrial diversification (Boschma, Citation2015). If such players exist, they will be very powerful as compared to other regional actors. This risk is smaller for regions with high industrial diversification because policy makers need to take into consideration the interests of more variegated stakeholder groups. This multiplicity of stakeholder groups in regions with high industrial diversification, however, increases the complexity of governance processes, concretely it will be more difficult to coordinate and engage the various stakeholders, make the entrepreneurial discovery process work, and facilitate collective action (Grillitsch, Citation2016).

Regions with high system differentiation but low industrial diversification are characterized by a critical mass of strong actors concentrated in one particular field. Under these preconditions, the emergence of completely new industries either through importation or new path creation would face opposition as existing competences, routines, and investments would devalue. On the one hand, if the region experiences growth in the industry of specialization, the production factors will be occupied and achieve high rents in the existing specialization. This will make it relatively unattractive for entrepreneurs and workers to move into a new industry where pay-offs are lower or still uncertain. On the other hand, a specialization in maturing and declining industries may release resources for other uses but it will be difficult to unlearn existing competencies and build up new ones. In comparison, related and unrelated diversification is more feasible because it allows entrepreneurs to re-use existing competencies in new industries where higher value can be achieved.

An important barrier for developing new growth paths through diversification is that regions with one dominant industry have a relatively homogeneous knowledge base. This means that there are limited opportunities through regional sources to apply existing competencies in other industries (related diversification) or to combine knowledge from different industries (unrelated diversification). This points to the need to develop extra-regional networks outside the field of specialization. Furthermore, breaking with the existing specialization is difficult due to cognitive, functional and political lock-ins (Grabher, Citation1993). Cognitive lock-in describes a situation when actors find it difficult to take in new information, unlearn existing routines, and learn new ones. Functional lock-in relates to interdependencies in production networks where making a small change requires changes in other parts of the value chain. Political lock-in captures institutional rigidities where powerful incumbent firms together with policy makers engage in self-sustaining coalitions. Incumbent firms aim at protecting vested interests while policy makers want to avoid job cuts due to downsizing or shutting down existing industrial activities.

Regions with high industrial diversification and high system differentiation have the largest range of opportunities for new industrial path development. Such regions exhibit a critical mass in several related and unrelated industries and are endowed with many of the elements that make a strong system for entrepreneurship and innovation. This provides the best preconditions for related and unrelated diversification as well as the creation of completely new industries. Nevertheless, also such regions may face difficulties in developing new growth paths or breaking with existing ones. A potential barrier relates to weak linkages between industries and sectors. This barrier is likely in such types of regions because of the high degree of specialization in different fields. With specialization, cognitive and institutional barriers tend to increase between each field and thereby also the challenge for knowledge transfers (Boschma, Citation2005). This links to another challenge, namely the exploitation of research-based knowledge created at universities and research facilities. The lack of exploitation capacity relates to a mismatch between scientific excellence and industrial specializations, which implies that regional industrial actors are not able to use and absorb the research-based knowledge generated in the region (Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2016). Furthermore, such regions may face difficulties in breaking with existing industrial paths and reallocating public support and resources to new industrial paths due to rigidities in policy repertoires (Morgan, Citation2016).

Table 3. Place-based barriers and opportunities for industrial path development.

3. Implications for a place-based policy for new industrial path development through entrepreneurship and SME policies

Following the discussion above, the opportunities and barriers for new industrial path development depend on the regional context. Responding to these place-specific opportunities and barriers, innovation and entrepreneurship policy has an important role for enabling and facilitating new industrial path development. Based on the conceptual framework elaborated above, place-based policy options for industrial path development can be developed (). The policy options are discussed from a systemic perspective, addressing actors, networks, and the institutional and organizational support structure. It is important to mention that this section does not discuss generic preconditions such as promoting entrepreneurial culture or good governance, which are beneficial for all types of regions.

Table 4. Place-based policy framework for new industrial path development.

3.1. Place-based policy for regions with low system differentiation and low industrial diversification

A reasonable policy objective for such regions is to gain a strong position in a niche and increase system differentiation. This implies a qualitative change of the regional industry, based on path upgrading or importation, which is more feasible than diversification processes or the creation of completely new paths. The long-term goal would be to transform the region into one that has a high degree of complexity in one specialization. In order to achieve this goal, it is paramount to strengthen the skills and competences of local actors in relation to a niche, because only knowledgeable and resourceful entrepreneurs and firms will be able to establish and draw benefit from extra-regional linkages. This combination of strong internal capabilities with extra-regional linkages is central in such regions. As regards networks, policy may support the positioning of local actors within global production networks or the establishment of linkages with universities and other knowledge providers. Such networks provide access to competencies and technologies (support renewal) and may open up opportunities for higher-value added activities in global production networks.

In line with that, institutional and organizational support needs to target the level of capabilities of local actors. As regards education and training, regional characteristics should be taken into account. It may be more useful to invest in training and education (life-long learning) of individuals that are grounded (e.g. by family ties, lifestyle choices) in the region, rather than providing training and education to a highly mobile group of people that may want to move to core regions. A cultural aspect deserving attention is the openness of regional actors towards external influences. Peripheral regions suffer more often than other regions from tight regional networks at the expense of the highly necessary interactions with external knowledge sources (Fitjar & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2011; Westlund & Kobayashi, Citation2013). This is problematic because it is often unfeasible to build (at least in the short-/medium-run) all the functions of strong systems of innovation and entrepreneurship locally. Remedies to these shortcomings are to stimulate a ‘global mindedness’ among local actors, i.e. an attention to and openness for global developments, as well as to facilitate access to resources and support structures in core regions. However, the inflow of knowledge and resources is often hampered due to the relatively low attractiveness of the region for external actors (e.g. highly skilled labour, firms) (Trippl et al., Citation2017). This justifies policies that aim at enhancing regional attractiveness (e.g. good public services, conditions for doing business, development of a regional identity) in order to retain and attract entrepreneurs, firms and skilled labour.

3.2. Place-based policy for regions with low system differentiation and high industrial diversification

A reasonable policy objective for regions with low system differentiation but high industrial diversification is to gain a strong position in relation to several niches and enhance overall system differentiation. Besides measures to strengthen actors’ capabilities in relation to specific economic activities, capabilities at a more general level (e.g. universities, government, civil society) are necessary to increase overall system differentiation. Inflow of external knowledge is important for regions with low system differentiation (Trippl et al., Citation2017). As high industrial diversification usually requires a relative large regional size, which then often implies also the presence of universities and other relevant actors in innovation systems (but with relatively low capabilities), one strategy is to mobilize and strengthen local universities and knowledge intensive business services as intermediaries. Such organizations often have international knowledge linkages and spread advanced knowledge through local networks (Herstad & Ebersberger, Citation2015; Strambach, Citation2008).

At the institutional level, strengthened governance processes that integrate the variegated stakeholder groups are important because only then it will be possible to take advantage from variety in terms of discovering potential areas of future competitiveness and mobilize collective efforts with the objective to reach a critical mass (Grillitsch, Citation2016). This will also contribute to solving the institutional problem of inadequate policy repertoires (Morgan, Citation2016) because such multi-stakeholder governance processes will help to identify the real needs and challenges, thereby allowing policy makers to better adapt their approaches. Furthermore, system differentiation will be enhanced by the attraction and upgrading of general support functions of innovation systems (e.g. education, research, technology transfer, business incubation, finance, etc.). Finally, regional attractiveness is a key factor for the inflow but also retention of individuals and organizations (Florida, Citation2003). As this particular type of region often constitutes a major regional capital, it can often build on assets such as access to regional markets, relatively well educated but cheap labour force, low living costs, alternative cultural scenes, etc.

3.3. Placed-based policy for specialized regions with high system differentiation

A reasonable general policy objective for regions with high system differentiation and low industrial diversification is often to move towards more dynamic industrial growth paths by exploiting related and unrelated diversification processes. Some regions may even attempt to develop strengths in several specializations, thus becoming a more diversified region. The latter is a policy option if the region is large enough (or can reasonably be expected to grow respectively) to allow for a critical mass in several specializations. As discussed previously, the relatively homogenous knowledge base in specialized regions is a major barrier for diversification. Therefore, actor related policy measures should aim at developing new skills and competencies in complementary fields among regional actors or by attracting new actors from outside the region.

As regards networks, the main barrier for new path development is not a lack of embeddedness in global production networks related to the existing specialization but the connectedness to related or unrelated fields. Therefore, policy should focus on the promotion of extra-regional linkages to sources of related and unrelated knowledge, comprising both industry and research. Despite this extra-regional focus, specialized regions may have some competencies in complementary fields that may be worth exploring. Furthermore, as regional industries move towards more dynamic growth paths through diversification, capabilities are built gradually in the emerging specialization. In the course of this process, opportunities for local knowledge interactions supporting the new growth path will increase. In addition, policy makers need to be attentive as regards networks with incumbent firms. It is natural that policy makers listen to powerful players representing the existing specialization. However, incumbent firms have vested interests that may conflict with the efforts to grow new industrial paths. Hence, it is important that policy makers engage in a broad dialogue, both regionally and extra-regionally, in order to break potential self-sustaining coalitions with incumbent firms.

In relation to institutional and organizational support structures, specialized regions with high system differentiation are expected to benefit from regional visioning exercises because such processes contribute to aligning the interests of influential and powerful players in the existing specialization with those of potential newcomers and to mobilize collective efforts for the shared objective of industrial diversification. In line with this, a reorientation of existing innovation and entrepreneurship policies is frequently required. It has been a common policy approach (e.g. cluster policies) to support existing specializations. This is also reasonable when clusters emerge and grow. However, such policies may be counter-productive when the desired outcome shifts from growth in the existing specialization towards industrial diversification. Then, the focus of cluster, entrepreneurship and innovation policy also needs to shift from strengthening existing fields to promoting competencies, networks, as well as innovation and entrepreneurship in new fields. This includes mobilizing collective resources for new activities and changing education and training programmes to support building competencies in new complementary fields. Furthermore, even though system differentiation is high in the field of specialization, some of the generic capabilities of systems of innovation and entrepreneurship are frequently difficult to build (e.g. the diversity of skills and knowledge available at main universities, provision of high-level business services for entrepreneurship, provision of risk capital, etc.). This suggests that policy should support access to such capabilities available in core regions.

3.4. Placed-based policy for diversified regions with high system differentiation

For diversified and highly differentiated regions, the overall policy objective typically includes the move towards more dynamic industrial growth paths but may also target the creation of completely new industries. As regards the former objective, diversified regions differ from specialized ones, as diversification will often result in a shift of resources between industries that are already present in the region. More concretely, the main feature of diversified regions with high system differentiation is that they have achieved a critical mass in several specializations. These specializations may be in different stages of development. Some may be emerging or growing, while others may be maturing or even declining. However, resources may not flow seamlessly from old to new industrial paths within the region due to e.g. skill mismatch or organizational rigidities. A valid policy rationale is thus to support actors in the weaker industrial paths to gain competencies related to the stronger industrial paths.

Diversified regions with high system differentiation host major universities and research centres. New scientific discoveries have the potential for creating completely new industrial paths. However, the path to innovation and growth from research-based knowledge is long. A relevant policy at the level of actors is therefore to increase capacities to commercialize research-based knowledge. These capacities may rest on local entrepreneurship, and for this end nourishing an entrepreneurial ecosystem plays an important role, or the inflow of external actors. As regards the latter, the development of the biotech industry in Vienna is a good example (Trippl & Tödtling, Citation2007). Vienna has strong competencies in (bio)medicine based on research, education and a leading university hospital. However, there was a lack of local actors with the capacities to absorb and innovate based on these competencies. Therefore, international companies that established branches and R&D units in Vienna were essential for creating a growth path pivoting around biotech activities.

As regards networks, entrepreneurs and firms will maintain extra-regional linkages within their fields of specialization due to the embeddedness of industries in global production and innovation networks. Furthermore, strong universities are typically linked internationally through research collaborations. The barrier to be addressed by policy is thus typically not a lack of extra-regional networks. The barrier is that networks usually evolve in response to interdependencies within social structures such as industries or academic fields. This implies that networks are typically thin between industries, technological fields and sectors. Hence, there is a policy rationale for enhancing connectedness between social structures, which in turn increases the likelihood for novel combination of knowledge and resources from related and unrelated fields, thereby promoting radical innovations, and in consequence industrial diversification or even the creation of novel industrial paths (Grillitsch, Citation2016).

As regards institutional and organizational support structures, diversified regions with high system differentiation are by definition endowed with many of the elements that make a strong system of innovation and entrepreneurship. It is a reasonable target to provide all core resources and generic capabilities for innovation and entrepreneurship locally. This means addressing potential bottlenecks in any of the crucial elements of systems of innovation and entrepreneurship as well as strengthening the interconnectedness between the elements as discussed previously. Interconnectedness may be facilitated by removing barriers for interactions and mobility between sectors (e.g. through extended leave policies), or creating possibilities for actors to have positions in different social structures (e.g. university professor engaged in entrepreneurial ventures; participation in advisory boards). Also, the establishment and promotion of platforms or organizations that cut across social sectors promote interconnectedness within diversified systems (e.g. associations for young entrepreneurs or business leaders) (Grillitsch, Citation2018). Finally, an important policy implication is to shift public support from established low-growth paths to new, dynamic industrial paths, which may be difficult due the rigidities associated with existing policy rationales and repertoires (Morgan, Citation2016).

3.5. Reflection for ‘real’ cases

We have discussed stylized regions but most real cases will not score high or low on all aspects that constitute system differentiation and may have ‘medium’ levels of industrial diversification. For instance, Warsaw (Poland) and More og Romsdal (Norway) are not located at the outer corners of the framework (see section 2.2). More og Romsdal is known for a leading cluster in the maritime industry but can also draw on some other industries (e.g. marine or furniture). In line with the proposed framework, More og Romsdal needs to develop complementary capabilities, establish knowledge linkages outside the area of specialization and mostly at an extra-regional scale, break with self-sustaining coalitions between incumbents and policy makers, reorient policies to support new industrial paths, etc. in order to promote path diversification. Yet, some niches may be identified (e.g. interior for yachts) at the intersections of the regional industries. Thus, to some extent the increase of connectedness between industries and sectors (which was highlighted as policy intervention for regions with high industrial diversification) also applies for More og Romsdal (see Asheim et al., Citation2017).

We have previously described Warsaw as region with high industrial diversification and a system differentiation that lies between Stockholm and Bucharest. As regards industrial diversification, Warsaw is characterized by a concentration of private services and benefits from several regional headquarters of multinational cooperations. It has a low share in manufacturing with only a few large, state-owned factories remaining in operation but still the highest concentration of electronics and high-tech industry in Poland. The incoming FDIs are concentrated in industries producing consumer products for the domestic market (e.g. Coca Cola), and outsourced or offshored business services (e.g. Scandinavian Airlines).

Reflecting its position as the national capital and largest city in Poland, it has the highest functions in public administration, a large number and variety of actors and organizations, strong universities, well-developed networks and social capital and adequate policy repertoires. Still most of the economic activities are characterized by a low innovation capacity. Hence in qualitative terms, the level of capabilities appears notably lower than for instance in Stockholm. As regards policy, this means that in the more advanced sectors, path diversification and new path creation (by exploiting knowledge of universities and research organizations) is feasible, while for the less innovative industrial activities path upgrading is more appropriate. In addition, path importation is (as demonstrated by several incoming FDIs) one of the ways of industrial path development.

4. Conclusions

New industrial innovation policy promotes structural change in regions towards higher value economic activities that ensure future competitiveness (Radosevic, Citation2017). Such `positive structural changé (Foray, Citation2017, p. 38) is also at the core of smart specialization strategies aiming to enhance economic growth through economic diversification and new path development (Asheim et al., Citation2017). Building on systemic approaches of innovation and entrepreneurship, the main objective of this paper is to provide a conceptual and analytical framework to design and improve place-based policies for economic diversification and new industrial path development. This framework suggests that policy analysis should cover the assessment of regional preconditions as captured by the degree of system differentiation and industrial diversification (see section 2.2), the assessment of regional opportunities and barriers for new regional industrial path development (see section 2.3), and the assessment of existing innovation and entrepreneurship policies. These assessments provide a basis for the design of policies and respective recommendations (see section 3), which are solidly grounded in place-specific context conditions.

The proposed framework for policy analysis is part of a reflective policy cycle as illustrated in . The analysis feeds into the design of innovation and entrepreneurship policies. Changes to those policies and consequently changed regional preconditions for innovation and entrepreneurship are the concrete and measurable outputs of the policy intervention. The effects of these changes on innovation and entrepreneurship activities are the systemic outcome of the policy intervention. The contribution of innovative entrepreneurship to economic diversification and new industrial path development in turn is the intended system impact. This changes regional preconditions, opportunities and barriers for further development and therefore becomes the new foundation for analysis.

Figure 3. Analytical framework for the design of place-based policy recommendations for new industrial path development.

Two qualifications shall be added to the proposed framework. First, while hard data provides background information about structural preconditions, the opportunities for new path development will rest largely on factors that are not measurable quantitatively. Opportunities are not only reflections of structural preconditions but also shaped by perceptions about the future (Garud, Kumaraswamy, & Karnøe, Citation2010; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2018). In this regard, the entrepreneurial discovery process extends from actors chasing market opportunities to institutional entrepreneurs, policy makers, and possibly even civil society. Hence, while the structural preconditions are important, this picture needs to be complemented with the inspirations and perceived future of regional actors, which is only possible through qualitative approaches (e.g. interviews, focus groups). Such an approach is in line with the idea that entrepreneurial discovery processes should inform policy design as propagated by the smart specialization approach (Foray, David, & Hall, Citation2009; Grillitsch, Citation2016; OECD, Citation2013).

Second, in concrete empirical contexts, it cannot be expected that stylized regional types will be observed as regional preconditions contain many aspects that manifest on continuous scales. Few regions will score high or low on all aspects that define the differentiation of systems of innovation and entrepreneurship. Furthermore, regions may be dominated by one industry but related and unrelated activities will often co-exist. This implies that policy recommendations need to be adapted to the specific regional context and consequently differ from the stylized cases. In a specific case, the policy repertoire may for instance include a mix of policy actions that address on the one hand increasing system differentiation through path upgrading, while on the other hand utilizing opportunities for diversification. The value of stylized cases is to develop an understanding of the cause-effect relationships between regional preconditions and opportunities/barriers for regional industrial path development. Knowledge about these cause-effect relationships is necessary for designing effective policies.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Sandra Hannig and Jonathan Potter for insightful discussions and reflections against the background of experiences with OECD’s Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Markus Grillitsch http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8406-4727

Additional information

Funding

References

- Asheim, B. T. (2007). Differentiated knowledge bases and varieties of regional innovation systems. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 20, 223–241. doi: 10.1080/13511610701722846

- Asheim, B. T., Boschma, R., & Cooke, P. (2011). Constructing regional advantage: Platform policies based on related variety and differentiated knowledge bases. Regional Studies, 45, 893–904. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2010.543126

- Asheim, B. T., & Gertler, M. S. (2005). The geography of innovation: Regional innovation systems. In J. Fagerberg, D. C. Mowery, & R. R. Nelson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of innovation (pp. 291–317). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Asheim, B. T., Grillitsch, M., & Trippl, M. (2016). Regional innovation systems: Past–present–future. In R. Shearmur, C. Carrincazeaux, & D. Doloreux (Eds.), Handbook on the geographies of innovation (pp. 45–62). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Asheim, B. T., Grillitsch, M., & Trippl, M. (2017). Smart specialization as an innovation-driven strategy for economic diversification: Examples from Scandinavian regions. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorghiu, L. Andreescu, & I. Wade (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 74–99). London: Elsevier.

- Asheim, B. T., & Isaksen, A. (2002). Regional innovation systems: The integration of local ‘sticky’ and global ‘ubiquitous’ knowledge. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 27, 77–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1013100704794

- Autio, E. (1998). Evaluation of RTD in regional systems of innovation. European Planning Studies, 6, 131–140. doi: 10.1080/09654319808720451

- Barca, F. (2009). An agenda for a reformed cohesion policy: A place-based approach to meeting European Union challenges and expectations. Brussels: European Commission.

- Barca, F., McCann, P., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2012). The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. Journal of Regional Science, 52, 134–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00756.x

- Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. (2004). Clusters and knowledge: Local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Progress in Human Geography, 28, 31–56. doi: 10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. The Academy of Management Annals, 3, 65–107. doi: 10.5465/19416520903053598

- Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39, 61–74. doi: 10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Boschma, R. (2015). Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Regional Studies, 49, 733–751. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.959481

- Boschma, R., Coenen, L., Frenken, K., & Truffer, B. (2017). Towards a theory of regional diversification: Combining insights from evolutionary economic geography and transition studies. Regional Studies, 51, 31–45. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

- Camagni, R., & Capello, R. (2013). Regional innovation patterns and the EU regional policy reform: Toward smart innovation policies. Growth and Change, 44, 355–389. doi: 10.1111/grow.12012

- Carayannis, E. G., & Rakhmatullin, R. (2014). The quadruple/quintuple innovation helixes and smart specialisation strategies for sustainable and inclusive growth in Europe and beyond. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 5, 212–239. doi: 10.1007/s13132-014-0185-8

- Charron, N., Dijkstra, L., & Lapuente, V. (2014). Regional governance matters: Quality of government within European Union member states. Regional Studies, 48, 68–90. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.770141

- Content, J., & Frenken, K. (2016). Related variety and economic development: A literature review. European Planning Studies, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1246517

- Cooke, P. (1992). Regional innovation systems: Competitive regulation in the new Europe. Geoforum, 23, 365–382. doi: 10.1016/0016-7185(92)90048-9

- Cooke, P. (2007). Social capital, embeddedness, and market interactions: An analysis of firm performance in UK regions. Review of Social Economy, 65, 79–106. doi: 10.1080/00346760601132170

- Cooke, P. (2012). From clusters to platform policies in regional development. European Planning Studies, 20, 1415–1424. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.680741

- Cooke, P., & Morgan, K. (1994). The regional innovation system in Baden-Wurttemberg. International Journal of Technology Management, 9, 394–429.

- Davidsson, P., & Wiklund, J. (1997). Values, beliefs and regional variations in new firm formation rates. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18, 179–199. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4870(97)00004-4

- Doloreux, D. (2002). What we should know about regional systems of innovation. Technology in Society, 24, 243–263. doi: 10.1016/S0160-791X(02)00007-6

- Doloreux, D., & Parto, S. (2005). Regional innovation systems: Current discourse and unresolved issues. Technology in Society, 27, 133–153. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2005.01.002

- Etzkowitz, H. (2012). Triple helix clusters: Boundary permeability at university–industry–government interfaces as a regional innovation strategy. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 30, 766–779. doi: 10.1068/c1182

- Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and “mode 2” to a triple helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy, 29, 9–123. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00034-7

- European Commission. (2012). Guide to research and innovation strategies for smart specialisations (RIS3). Brussels: Joint Research Center, European Commission.

- European Commission. (2014). National/regional innovation strategies for smart specialisation (RIS3). Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. (2017). Regional innovation scoreboard 2017. Brussels: European Commission.

- Fitjar, R. D., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2011). When local interaction does not suffice: Sources of firm innovation in urban Norway. Environment and Planning A, 43, 1248–1267. doi: 10.1068/a43516

- Florida, R. (2003). Cities and the creative class. City and Community, 2, 3–19. doi: 10.1111/1540-6040.00034

- Foray, D. (2009). Understanding smart specialisation. In D. Pontikakis, D. Kyriakou, & R. Van Bavel (Eds.), The question of R&D specialisation, perspectives and policy implications (pp. 19–28). Brussels: Joint Research Center.

- Foray, D. (2014). From smart specialisation to smart specialisation policy. European Journal of Innovation Management, 17, 492–507. doi: 10.1108/EJIM-09-2014-0096

- Foray, D. (2017). The economic fundamentals of smart specialization strategies. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorghiu, L. Andreescu, & I. Wade (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 37–50). London: Academic Press.

- Foray, D., David, P. A., & Hall, B. (2009). Smart specialisation–the concept. Knowledge Economists Policy Brief, 9, 100.

- Frenken, K., & Boschma, R. A. (2007). A theoretical framework for evolutionary economic geography: Industrial dynamics and urban growth as a branching process. Journal of Economic Geography, 7, 635–649. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbm018

- Frenken, K., Van Oort, F., & Verburg, T. (2007). Related variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Regional Studies, 41, 685–697. doi: 10.1080/00343400601120296

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2014). The long persistence of regional levels of entrepreneurship: Germany, 1925–2005. Regional Studies, 48, 955–973. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.816414

- Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., & Karnøe, P. (2010). Path dependence or path creation? Journal of Management Studies, 47, 760–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00914.x

- Gibney, J., Copeland, S., & Murie, A. (2009). Toward a ‘new’ strategic leadership of place for the knowledge-based economy. Leadership, 5, 5–23. doi: 10.1177/1742715008098307

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties; the lock-in of regional development in the Ruhr area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The embedded firm: On the socioeconomics of industrial networks (pp. 255–277). London: Routledge.

- Grillitsch, M. (2016). Institutions, smart specialisation dynamics and policy. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34, 22–37. doi: 10.1177/0263774X15614694

- Grillitsch, M. (2018). Following or breaking regional development paths: On the role and capability of the innovative entrepreneur. Regional Studies, 80, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2018.1463436

- Grillitsch, M., & Asheim, B. (2016). Cluster policy: Renewal through the integration of institutional variety. In D. Fornahl, R. Hassink, & M.-P. Menzel (Eds.), Broadening our knowledge on cluster evolution (pp. 76–94). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Grillitsch, M., Asheim, B., & Trippl, M. (2017). Unrelated knowledge combinations: Unexplored potential for regional industrial path development. Papers in Innovation Studies, CIRCLE, Lund University Nr. 2017/10:1–25.

- Grillitsch, M., & Nilsson, M. (2015). Innovation in peripheral regions: Do collaborations compensate for a lack of local knowledge spillovers? The Annals of Regional Science, 54, 299–321. doi: 10.1007/s00168-014-0655-8

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2018). Regional growth paths: From structure to agency and back. Papers in Innovation Studies, Nr. 2018/1. Centre for Innovation, Research and Competence in the Learning Economy (CIRCLE), Lund University.

- Grillitsch, M., & Trippl, M. (2016). Innovation policies and new regional growth paths: A place-based system failure framework. Papers in Innovation Studies No. 2016/26.

- Hassink, R. (2010). Locked in decline? On the role of regional lock-ins in old industrial areas. In R. Boschma & R. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 450–468). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Herstad, S. J., & Ebersberger, B. (2015). On the link between urban location and the involvement of knowledge-intensive business services firms in collaboration networks. Regional Studies, 49, 1160–1175. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.816413

- Institute for Market Economics. (2017). Regional profiles. Indicators of Devleopment 2017. Retrieved from http://www.regionalprofiles.bg/en/

- Isaksen, A., Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2016, August 23–26). Innovation policies for regional structural change: Combining actor-based and system-based strategies. In 56th ERSA Congress, Vienna, Austria.

- Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2016). Path development in different regional innovation systems. In M. Parrilli, R. Fitjar, & A. Rodríguez-Pose (Eds.), Innovation drivers and regional innovation strategies (pp. 66–84). New York: Routledge.

- Landabaso, M. (2014). Guest editorial on research and innovation strategies for smart specialisation in Europe. European Journal of Innovation Management, 17, 378–389. doi: 10.1108/EJIM-08-2014-0093

- Lee, S. Y., Florida, R., & Acs, Z. (2004). Creativity and entrepreneurship: A regional analysis of new firm formation. Regional Studies, 38, 879–891. doi: 10.1080/0034340042000280910

- Lundvall, B.-A. (1988). Innovation as an interactive process: From user-producer interaction to the national system of innovation. In G. Dosi, C. Freeman, R. Nelson, G. Silverberg, & L. L. Soete (Eds.), Technical change and economic theory (pp. 349–369). London: Frances Pinter.

- Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. (2006). Localized learning revisited. Growth and Change, 37, 1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2257.2006.00302.x

- Martin, R. (2010). Roepke lecture in economic geography—rethinking regional path dependence: Beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86, 1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Vol. 38. Paris: OECD.

- Milberg, W., & Houston, E. (2005). The high road and the low road to international competitiveness: Extending the neo-Schumpeterian trade model beyond technology. International Review of Applied Economics, 19, 137–162. doi: 10.1080/02692170500031646

- Morgan, K. (1997). The learning region: Institutions, innovation and regional renewal. Regional Studies, 31, 491–503. doi: 10.1080/00343409750132289

- Morgan, K. (2016). Nurturing novelty: Regional innovation policy in the age of smart specialisation. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 35, 569–583.

- Morgan, K., & Cooke, P. (1998). The associational economy: Firms, regions, and innovation. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=1496189

- National Statistical Institute of the Republic of Bulgaria. (2018, June 6). Employed persons by regions. Retrieved from http://www.nsi.bg/en/content/5528/employed-persons-regions

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., & Boschma, R. (2011). How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of new growth paths in regions. Economic Geography, 87, 237–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

- OECD. (2013). Innovation-driven growth in regions: The role of smart specialisation. preliminary version. Paris: OECD.

- Porter, M. E. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, 76, 77–90.

- Porter, M. E. (2000). Location, competition, and economic development: Local clusters in a global economy. Economic Development Quarterly, 14, 15–34. doi: 10.1177/089124240001400105

- Radosevic, S. (2017). Assessing EU smart specialisation policy in a comparative perspective. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorghiu, L. Andreescu, & I. Wade (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 2–36). London: Academic Press.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Di Cataldo, M. (2015). Quality of government and innovative performance in the regions of Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, 15, 673–706. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbu023

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1911). Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung. Leipzig: Duncker & Humbolt.

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. The Academy of Management Review, 25, 217–226.

- Shearmur, R., & Doloreux, D. (2016). How open innovation processes vary between urban and remote environments: Slow innovators, market-sourced information and frequency of interaction. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 28, 337–357. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2016.1154984

- Simmie, J. (2012). Path dependence and new technological path creation in the Danish wind power industry. European Planning Studies, 20, 753–772. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.667924

- Sotarauta, M., Beer, A., & Gibney, J. (2017). Making sense of leadership in urban and regional development. Regional Studies, 51, 187–193. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1267340

- Sotarauta, M., & Heinonen, T. (2016). The triple helix model and the competence set: Human spare parts industry under scrutiny. Triple Helix, 3, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40604-016-0038-5

- Sotarauta, M., & Suvinen, N. (2018). Institutional agency and path creation: Institutional path from industrial to knowledge city. In A. Isaksen, R. Martin, & M. Trippl (Eds.), New avenues for regional innovation systems - theoretical advances, empirical cases and policy lessons (pp. 85–104). New York: Springer.

- Storper, M. (1995). The resurgence of regional economies, ten years later: The region as a nexus of untraded interdependencies. European Urban and Regional Studies, 2, 191–221. doi: 10.1177/096977649500200301

- Storper, M., Kemeny, T., Makarem, N. P., & Osman, T. (2016). On specialization, divergence and evolution: A brief response to Ron Martin’s review. Regional Studies, 50, 1628–1630. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1183975

- Strambach, S. (2008). Knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) as drivers of multilevel knowledge dynamics. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 10, 152–174. doi: 10.1504/IJSTM.2008.022117

- Strambach, S., & Klement, B. (2012). Cumulative and combinatorial micro-dynamics of knowledge: The role of space and place in knowledge integration. European Planning Studies, 20, 1843–1866. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.723424

- Tödtling, F., & Grillitsch, M. (2015). Does combinatorial knowledge lead to a better innovation performance of firms? European Planning Studies, 23, 1741–1758. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2015.1056773

- Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2005). One size fits all? Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Research Policy, 34, 1203–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.018

- Trippl, M., Grillitsch, M., & Isaksen, A. (2017). Exogenous sources of regional industrial change. Progress in Human Geography. doi: 10.1177/0309132517700982

- Trippl, M., & Otto, A. (2009). How to turn the fate of old industrial areas: A comparison of cluster-based renewal processes in Styria and the Saarland. Environment and Planning A, 41, 1217–1233. doi: 10.1068/a4129

- Trippl, M., & Tödtling, F. (2007). Developing biotechnology clusters in non-high technology regions—the case of Austria. Industry and Innovation, 14, 47–67. doi: 10.1080/13662710601130590

- Van de Ven, A. H., Polley, D. E., Garud, R., & Venkataraman, S. (1999). The innovation journey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- von Hippel, E. (2005). Democratizing innovation: The evolving phenomenon of user innovation. Journal für Betriebswirtschaft, 55, 63–78. doi: 10.1007/s11301-004-0002-8

- Westlund, H., & Kobayashi, K. (2013). Social capital and sustainable urban-rural relationships in the global knowledge society. In H. Westlund, & K. Kobayashi (Eds.), Social capital and rural development in the knowledge society (pp. 1–17). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.