ABSTRACT

Even before officially sanctioned as a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene conquers the imaginary and is reified as awareness-raising, inspiring, universalist, capitalist-technocratic, dangerous. As critical scholarship discerns in this name-nomination an opportunity to rethink the human/more-than-human/environmental nexus, debating the Anthropocene becomes in itself more policy/politically relevant than its actual confirmation as a new geological epoch. However, the Anthropocene debate remains remarkably disembodied, engaging rarely with emerging actors and practices across the world that drive precisely the socio-ecological transformations that critical scholars advocate. Correspondingly, most actors involved in these practices are indifferent to the Anthropocene debate. And here, I argue, lies the task of academic labour: to engage in what I call a scholarship of presence; a scholarship that adds empirical weight to our theoretical musings around the Anthropocene. To do this, we need to be prepared simultaneously to explore the world like a frog and see it like an eagle; to be present locally, splashing (frog-like) into the murky waters of empirics; and to zoom-out broaden the gaze (eagle-like) from localized struggles, make comparisons and develop broader conceptual contributions. Such a scholarship of presence can be instrumental in making the Anthropocene the quilting point for articulating geographically fragmented struggles into a new ethico-aesthetic paradigm.

1. Introduction

Presence (English) state of … existing, occurring. ORIGIN: from Latin praeessee, from prae [=before] + esse [be] Παρουσία (Greek for ‘presence’) sate of existing next to, standing by the side of. ETYMOLOGY: πάρειμι, from παρά [=next to] + εἱμί [=be]

Before designated as the official name a new geological epoch, the term ‘Anthropocene’ has already captivated the academic and public imagination. It is discussed as awareness-raising, inspiring, universalist, awesome, enabling, but at the same time as capitalist-technocratic and dangerous. As critical scholarship discerns in this name-nomination an opportunity to think differently about the human/more-than-human/environmental nexus, the term ‘Anthropocene’ in itself becomes more policy/politically relevant than its actual confirmation (or not) as the name of a new geological epoch.

However, the intensifying academic debate around the Anthropocene remains remarkably disembodied, as it engages rarely with the on-the-ground actors and practices that drive exactly the type of processes of socio-ecological transformation and subject formation that critical Anthropocene scholars advocate. Correspondingly, the actors involved in generating these socio-environmental practices are often oblivious or indifferent to academic debates over the Anthropocene.

This hiatus between academic debate and political praxis in the face of intensifying socio-environmental challenges places new demands on the academic vocation and invites a more reflexive attitude with respect to the focus and purpose of academic labour. I suggest that this gap can be addressed through the pursuit of a scholarship that would put as much effort in documenting alternative localised socio-environmental practices as in abstracting from these practices, making global connections, and producing new visions to address mounting socio-environmental challenges.

I call this type of scholarship a ‘scholarship of presence’, as it requires us to practice being ‘present’ in two distinct and interrelated ways. First, it invites practicing ‘presence’ as the act of existing/standing next to, in close proximity to others. This practice of ‘presence’ is not just about documenting; it is also about doing or seeing things in common when it comes to developing alternative localised socio-environmental practices.

Second a scholarship of presence requires practicing being ‘present’ as the act of existing/standing in front of others. This second practice of ‘presence’ demands standing at some distance as a scholar who can abstract without losing sight of the particular, make connections, construct new narratives, and communicate alternative knowledge(s), and visions that can address pressing socio-environmental challenges.

A ‘scholarship of presence’ would therefore force us to zoom-in empirically, make our hands ‘dirty’ and splash (a bit like a frog) into the murky waters and messiness of local struggles and conflicts. But at the same time it demands that we are able to zoom-out, to distance our gaze (a bit like an eagle) from the militant particularisms of local socio-environmental struggles in order to see the bigger picture, advance comparative analyses and make broader conceptual contributions.

This binary practice of being ‘present’ (as being next to/in common with others; and being in front of others) also corresponds to a binary etymology of the word ‘presence’ in different languages and cultural contexts. In Latin-origin languages ‘presence’ originates in praeesse, which indicates the stand alone act of existing in front of/before something or someone (from prae [=before] and esse [be]). In the Greek language, the etymology of ‘presence’ (παρουσία) indicates standing/existing not alone, but standing/ existing next to, together with others, doing things in common (from πάρειμι: παρά [next] and εἱμί [be]). In the Greek word for presence (παρουσία) the act of commoning is already embedded in the linguistic symbolization of presence; one cannot be present on one’s own; being present requires being in common.

My call for practicing a ‘scholarship of presence’ as a binary yet integrated act, is a call to face and overcome our own dualisms in the division of academic labour between ‘empirical’ and ‘theoretical’ work. No doubt, overcoming this dualism requires hard(er) work. But a ‘scholarship of presence’ that sees the world like an eagle, and explores it like a frog would add empirical weight to out theoretical musings around the Anthropocene. And it could also enhance the articulation of geographically fragmented localised struggles into a coherent narrative that can elevate the Anthropocene debate into a new ethico-aesthetic paradigm.

2. The imaginary of nature: the Anthropocene as a master narrative that is becoming performative

About a decade ago, the Global Edition of the New York Times featured an article on long term unemployment and homelessness in Poland. The article, titled ‘Homeless Poles look to the sea’ was surprising, in that it conveyed vision, not despair (Kulish, Citation2009). It was the story of 25 long term unemployed and homeless Polish men, who set out, with almost no resources, to build a boat that would eventually enable them to sail around the world. For these 25 men, nature (in the form of the sea) featured as a symbolic and material frontier that had to be conquered as part of a process of transcending their current condition of unemployment and homelessness.

Their dream to conquer ‘nature’, to leave their mark on the physical world, is certainly not new. Throughout human history and mythology conquering nature has been an act of simultaneous liberation of the self and dominance of others; an act of asserting power (economic or other) and human (mostly male) superiority over other beings- human or non-human. From Prometheus’ mythical striving to conquer the element of fire, and Ulysses’ journey of mastering the sea and its creatures, to the real life Promethean efforts of Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott to reach the South Pole (Katz & Kirby, Citation1991), Edward Teller’s plans to reshape Alaska with hydrogen bomb blasts (Kirsch & Mitchel, Citation1998), and most recently, Richard Branson’s and Elon Musk’s search for capital expansion to the ‘ultimate’ frontier’- space.

The whole history of the western world is a history of conquering nature. Indeed, the history of urbanization is a history of urbanizing nature (Kaika, Citation2005). Urbanization is predicated upon piercing mountains, damming rivers, deep drilling into ocean floor, rummaging through energy landscapes and -more recently- fracking and blasting. Since the industrial revolution, this relentless creative destruction (Berman, Citation1971) and production of ‘second natures’ (Lefebvre, Citation1974; Smith, Citation1984) has extended in ways that affected global geophysical transformations to such an extent that humanity is now considered to be not simply one of earth’s biological factors, but a geological actor too; an actor that shapes geophysical transformations on the earth’s stratigraphy the way only ‘natural’ forces used to do in earth’s previous long history (Dalby, Citation1992).

So, we might as well name this relentless, intense and intensifying imprint of human activity on the earth a new geological epoch the ‘Anthropocene’, a term coined by Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer (Citation2000) on the grounds that within this epoch human activity became ‘the most powerful influence on the earth and its environment, climate and ecology in ways that will leave long-term imprints in the earth’s stratigraphy’.Footnote1 Predictably, Crutzen and Stoermer’s (Citation2000) nomination for ‘the Anthropocene’ has stirred intense debate in earth and environmental sciences. If the Anthropocene Working Group of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy gathers enough evidence to recommend renaming, it will create significant work for physical geographers and geologists, who will busy themselves tracing the imprints of this epoch onto the earth’s strata.

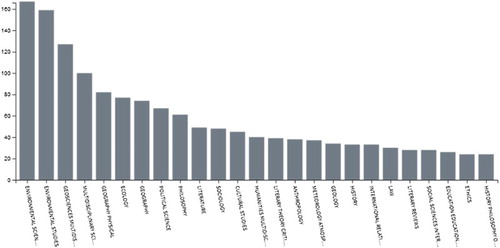

Less predictably, however, and perhaps more interestingly, the discussion over the Anthropocene already gathered weight way beyond the chambers of geological societies and scientific conferences. Although the humanities did not seem to have taken any notice of the name or characteristics of our current geological epoch (Holocene), the concept of the Anthropocene generated mass media and academic attention within a remarkably short period of time, not only in planning (Brondizio et al., Citation2016) and human geography (Leichenko & Mahecha, Citation2015) but also in design, cultural studies, politics, international law, and urban studies. Research, teaching and training curricula in the arts and humanities are currently revised so that students can be taught how to plan and design cities ‘for the Anthropocene’, how to manage the environment or the economy ‘in the Anthropocene’ (Head, Citation2015), how to govern in the Anthropocene (McLean, Citation2016), or how to live in the Anthropocene (Gibson, Rose, & Fincher, Citation2015). What Castree (Citation2015) noted a few years back, that the Anthropocene debate was dominated by geoscientists and few environmental social scientists, no longer holds true . Out of a total of 1193 documents returned on the Web of Science featuring the ‘Anthropocene’ in their title in May 2018, 49.6% (592 records) are in the arts, humanities and social sciences, with the highest count in human geography (73 records, 6.1%), followed by political science (66 records, 5.5%, philosophy (60, 5.0%), literature (48, 4.0%), sociology (47, 3.9%), cultural studies (44, 3.6%), humanities multidisciplinary (39, 3.2%) literary theory (38, 3.1%), anthropology (37, 3.1%), history (32, 2.6%). International relations (32, 2.6%), law (29, 2.4%), etc. (see ).

Figure 1. Analysis by discipline of Web of Science abstracted documents featuring the Anthropocene in the title. Out of a total of 1193 documents featuring the ‘Anthropocene’ in their title in May 2018, 49.6% (592 records) are in the arts, humanities and social sciences Data and Graphics direct from Web of Science, May 2018.

What this indicates is that, even before the Anthropocene is confirmed as the name of a new geological epoch, it has already conquered our imaginary and is creating ‘friction’ (Randalls, Citation2015; Whitehead, Citation2014) like few other concepts have done over the past decades. And because of this conquest of the imaginary, the Anthropocene is already acquiring status and weight of character. It is objectified, and praised for raising awareness on the current environmental crisis (Hamilton, Bonneuil, & Gemenne, Citation2015), or for inspiring us to be more alert to climate change, and find new modes of subject formation and place making (Bristow, Citation2015; Wakefield & Braun, Citation2014; Yusoff, Citation2013). But it is also accused of being arrogant (the ultimate hubris against nature), Universalist (assuming that all humans will be equally affected) (Moore, Citation2015; Purdy, Citation2015) and capitalist/technocratic (depicts human/natural history as a succession of technological innovations, thus ignoring the social relations that drive this history) (Moore, Citation2015; Purdy, Citation2015; see also (Macfarlane, Citation2016).

Awareness-raising, inspiring, arrogant, Universalist, capitalist-technocratic … all or none of the above. This conquest of the imaginary and the weight of character offered to the concept through our intense engagement matters arguably more than any negative or positive quality that we may assign to the epoch. What I suggest in this paper is that this emerging imaginary of the Anthropocene itself may in fact be the most political thing about the Anthropocene. The proliferating debate beyond physical geography and geology raises it to a matter of contested public concern, and is fast becoming more policy/politically relevant than its actual adaptation (or not) as an official name. Our collective engagement with the Anthropocene offers it the status of an emerging master narrative (or rather, several master narratives – see (Bonneuil, Fressoz, & Fernbach, Citation2016) that already becomes performative even before the concept is officially instituted; a radical imaginary that demands to be institutionalized (Castoriadis, Citation1987; Kaika, Citation2011).

3. The weight of the imaginary: instituting the Anthropocene as the dominant social narrative for the twenty-first century

The proliferating literature around the Anthropocene in the arts, humanities and social sciences is mostly critical. However, this critical over-engagement seems to have -for the time being- one clear political consequence: it adds symbolic power and scholarly weight to a concept that can contribute further towards ‘naturalizing’ capitalism (Moore, Citation2015). By rubber stamping Nature as endlessly malleable by the geological force called humankind, the Anthropocene becomes a new imaginary signification that depicts the production of second natures though technology, labour, and capital investment, (pierced mountains embanked rivers, fracked landscapes, dammed waterways) as naturalized spatial ontologies. Suggesting the effects of perpetual capital expansion as stratigraphic evidence makes them acquire the same ontological status as rocks, fossils, minerals, and tectonic plates, the stigmata of the latest geological force: humankind. These naturalized spatial ontologies institute the social configurations of power that produced them as real ‘natural’ existing things.

The Anthropocene label, Moore (Citation2015) argues, can only endorse and perpetuate the current status quo and the search for technological rather than social solutions to continuous practices of socio-environmental destruction. The institution of the Anthropocene as a dominant social imaginary for twenty-first century capitalism becomes the means for ensuring that any debate over social change is saturated by a debate over mitigating climate change and environmental destruction (Purdy, Citation2015). The UN’s New Urban Agenda endorses this; if only we could find the right technology, the smartest city, the greenest design, the most techno-environmentally friendly city form, we would all live happily ever after on earth’s new geological epoch (Kaika, Citation2017). The Anthropocene is becoming a deterministic and teleological way of thinking about the future of the earth and the future of human and more-than-human beings. The imaginary of the Anthropocene emerges as one that not only rubber stamps capitalism as the only possible mode of socio-economic organization for the epoch; but also reproduces current socio-environmental relations as the only imaginary possible for the future. Foreclosing alternative processes of subjectivisation and possibilities for autonomy, it becomes a totem that indicates to society what to desire and how to desire it (Kaika, Citation2011); or to even stop altogether desiring alternative socio-environmental arrangements.

However, much of the humanities’ and social sciences’ critical engagement with the Anthropocene is trying to contest this emerging dominant imaginary. It tries to turn the nomination of a new geological era into an opportunity to think differently about the human/more-than-human/environmental nexus. Many authors engage in a search for an alternative politics for the Anthropocene (Purdy, Citation2015), exploring whether it can become the ignition point for developing more inclusive ontologies and epistemologies (Latimer & Miele, Citation2013); or multispecies ethnographies (Watson, Citation2014) that undercut the dominant power relations, including the socially constructed dichotomy between humans and non-humans. Yusoff sees in the concept a driver for searching/scripting a new history of human origin (Yusoff, Citation2016). The Anthropocene is also seen as a contingency to re-assess the dichotomy between social and human sciences (Rose, Citation2013) and to radically rethink the division of disciplines that can lead to a better understanding of the root-cause and proposed solutions to climate change (Szerszynski, Citation2010).

One can hardly exaggerate the political importance of the intellectual labour invested in trying to de-couple the Anthropocene debate from the pursuit of further technocratic and techno-managerial solutions. Adding symbolic weight to the concept as a potentially alternative way of thinking and doing socio-environmental politics can become a means of turning it into a powerful new radical imaginary; a new narrative that can support radical demands and social mobilization over socio-environmental change. Instead of foreclosing the potential for change and asserting techno-economic solutions as the only way forward, the idea of the Anthropocene can potentially expand the scope of political action and inform how everyday practices link to global capitalist expansion and environmental change. Everything seems to be up for grabs at the moment.

And here, I argue, in this brief moment of openness of symbolization, lies the task for academics/public intellectuals and planning and design practitioners alike: not only to further dialogue around the concept per se (which is already happening), but also to try and make it performative politically by linking the concept to contemporary practices and struggles over socio-environmental change. In short, the urgent task is to conquer the imaginary over the Anthropocene; to use the concept’s acquired symbolic weight in order to strengthen the voice and imaginaries of emerging socio-political demands that try to disrupt the power landscapes of the era (named Anthropocene or not) and resist the capitalist developmental logic as the force that can continue to dominate the earth.

4. The need to de-colonize the imaginary at times of crisis

Everyone has read or at least heard of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (Carson, Citation1962). The book was so significant in breathing new life into the environmental movement not simply because it offered a compelling scientific analysis of the effects of pesticide-use on bird populations per se. The book was so significant and became iconic also because it offered a powerful symbolization (notably through its title) that forced our imaginary to link everyday life (birds tweeting in the spring) to the politics and practices of the post-war chemical industry that led to environmental destruction (the silence of birds).

Can the Anthropocene do something similar? Can it become anything beyond a name change in a geological epoch? Can it mobilize anyone or anything outside scientists who have to trace the signature of humans onto the earth’s strata? Can this name change become politically performative, as some of the more optimistic authors suggest, and add weight, symbolism and political momentum to contemporary social struggles for equality and socio-environmental change? Or will it end up becoming an empty signifier like so many other buzzwords that preceded it, notably ‘sustainability’? Our experience with the concept of ‘sustainability’ is disheartening. After that concept ruled policy and academic debates for over 3 decades, after having generated hope and optimism over environmental politics, the call for ‘sustainable development’ ended up further reproducing technocratic ‘solutions’ endorsing the continuation of the same old developmentalist logic (smart cities, green cities, smart technologies etc). Can the Anthropocene avoid a similar fate?

If we take seriously our own criticism and engagement with the Anthropocene, we should equally take seriously the fact that whether the epoch is called Anthropocene or not is actually irrelevant if viewed from the perspective of the urgent necessity to put into gear processes of socio-environmental change. So I suggest we move beyond an Anthropocene debate that is not only self-referential but also a-geographical, as it tends thus far to mask diversity and difference in local and regional contexts (Biermann et al., Citation2016; see also Lovbrand et al., Citation2015). I suggest instead to focus our attention on linking this debate to emerging practices and alternative radical imaginaries that demand new socio-environmental arrangements.

Take, for example, the 25 homeless Poles I mentioned in the beginning of this article. Their project to conquer nature in the form of the sea was something over and above an act of asserting power and dominance. It was not driven by a debate over a geological epoch; it was an act of necessity. It was born out of the need to challenge and change their relationship to the world; it was about asserting that they are still alive and still worth a place in a society that had largely forgotten about them and written them off. It was a project that staged equality within an increasingly socio-environmentally uneven and unequal world. There are many actors – some more, some less known- that generate such practices and imaginaries across the world today. In Romania, for example, a fifteen year long anti-mining struggle in Rosia Montana, has given birth to new subjectivities performed as demands against representational and consensual politics and as prompts to rethink what environmental justice means. The local residents and anti-mining activists (the Rosieni) challenged the reduction of environmental justice to representational/consensual politics; they refused to ‘sit around the table’ with predefined roles and power relations (Velicu & Kaika, Citation2015). They demanded (through performative acts of the everyday) visibility instead of participation, and chose autonomy over redistribution of profits from the destruction of their environmental and social values. They demanded re-thinking both the concept of environmental justice, and the concept of participation, as expressions of the relentless exploitation of human and non-humans alike in the name of development. In Greece, the coalition against the privatization of the public water company of Thessaloniki (EYATH) tendered a bid to buy back the public water company when it came up for privatization. In a long drawn out struggle a broad citizens’ coalition (notably Initiative ‘K136’ and ‘Soste to Nero’) asked citizens to contribute 136 euros each to buy back the public water company when it came up for sale. This act in effect asked citizens to transform 136 euros from mere consuming/purchasing power into flows of autonomous subjectivisation (Lazzarato, Citation2007). The citizens’ movement offered alternative imaginaries to the privatization solution to the Tragedy of the Commons which were arguably more efficient socially, environmentally, and perhaps economically.

Most actors involved in the aforementioned and many other resistance practices today across the world are neither driven nor inspired by the Anthropocene per se. In fact, most ignore the concept’s existence altogether. They are driven by the necessity – at times despair even- induced by prolonged social exclusion and inequality. The socio-environmental and deeply political processes described above share in common the fact that – although oblivious to the Anthropocene debate- the actors involved radically shifted the terrain of power, and turned nominally powerless citizens into potentially powerful decision makers with a renewed capacity to manage their commons under the Anthropocene or otherwise named era. These movements contribute towards avoiding all of us accepting and vesting the powerless role of discredited political subjects, incapable of producing our own socio-environmental histories in the face of the new/old geological era. Similar processes of resistance and subjectivisation proliferate across the world (Fredriksen, Citation2016; Martindale, Citation2015; Martinez Alier, Citation2005; Reynolds & Szerszynski, Citation2016) taking a radical stance against the ‘naturalization’ of socio-environmental degradation under late capitalism (Brand, Citation2007). They are inspiring reminders that during moments of crisis, constructing and performing/embodying/enacting a new vision, a new socio-ecological imaginary, becomes central in the construction of a new myth that can sustain the future and give meaning to the present.

A key question is: can the Anthropocene provide the quilting point for articulating these geographically fragmented socio-environmental imaginaries and struggles into a coherent, powerful and politically performative narrative? Can the concept act performatively into turning these alternative stories into new ethico-aesthetic paradigms (Guattari, Citation1989)? Can the Anthropocene become our new myth for an alternative future?

5. Between the frog and the eagle: reclaiming a scholarship of presence for the Anthropocene

The current academic debate over the Anthropocene remains thus far disembodied, and delinked from everyday socio-environmental practices like those presented in the previous section. Nevertheless, such practices are invaluable for advancing the Anthropocene debate, as they offer concrete alternative ways of perceiving and performing the role of humans and other beings during our epoch. Many go so far as to offer concrete methods that defy technical solutions to environmental ills and put forward radical demands for socio-environmental equality. For example, calling citizens to refrain from using 136 euros as additional buying capacity (for a new smartphone, new jumpers, shoes, etc.) and turn it instead into real capital by buying back the commons (water in Thessaloniki) is a radical gesture that redefines our role in the power equation of capitalist expansion (in the Anthropocene). Refusing to sit around the table to negotiate the terms of destruction of our livelihoods and environment in return for ‘redistributive’ practices and mining jobs (Rosia Montana case) does the same. Fighting for global minimum wages (as Negri suggests) or for a radical redistribution of resources through the global ban of private wealth inheritance (as Olivier-Padis suggests) are also radical ideas awaiting to be linked to everyday practices.

These alternatives demonstrate the paradoxical character of the call upon science and technology (an alias for capitalism, as Castoriadis (Citation1987) notes) to save us from capitalism. Even if/when their militancy withers away, these movements will have put into gear a process of subject formation that challenges the social fatalism of a deepening socio-environmental crisis; a process that becomes a generative force for a broader socio-ecological transformation that can potentially prevent an Anthropological as well as the confirmed geological catastrophe.

And herein, I argue, lies the intellectual responsibility of the social sciences and humanities: to add gravitas to these emerging imaginaries; to engage more systematically in symbolizing and narrating these proliferating alternative socio-spatial/ socio-environmental arrangements as part of a new epoch; to add symbolic weight to the narratives that show we can think and desire differently. If we, as academics, planning professionals or urban practitioners wish to have an impact, we need to be prepared to explore the many diverse venues across which social change originates – as Hulme (Citation2015) argues – and to contribute towards turning scientific buzzwords into ‘societal keywords’ (Castree, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2014c).

How do we do this? Let us go back to Carson’s Silent Spring, for inspiration, or to any book or author who has inspired or driven research, intellectual, and policy agendas in the past. For me, such a list would include – amongst many others- thinkers as diverse as Marx and Engels, Simmel and Arendt, Benjamin Debord and Lefebvre, Carson and Jacobs, Castoriadis, Harvey and Irigaray). Despite the diversity, I can identify at least three common characteristics amongst these authors. First, they worked outside and beyond disciplinary boundaries and were often contrarians to mainstream academic discourse. Second, their work was not a response to funding streams or academic assessment; it was politically driven not by academic impact agendas, but by everyday life. Third, their intellectual labour was a hard labour of love (Kaika & Ruggiero, Citation2018). Whether they were documenting the conditions of the working class in nineteenth-century Manchester (Engels), the psycho geographies of Metropolitan Life (Simmel), the role of moustachioed hot dog vendors in the street corners of New York (Jacobs), or the silencing of birds (Carson), their intellectual labour was a hard going rigorous and embodied process, in which they moved continuously from a frog’s to an eagle’s perspective. That is, from being present, down there, from a frog’s perspective, zooming into the streets, collecting details of everyday life, day in day out, mapping and documenting tedious facts and empirical details (from the number of inhabitants in nineteenth century tenements to incidents of pesticide exposure and its link to human and environmental damage) – to zooming out, acquiring an eagle’s perspective, in order to see the broader picture, make connections between different territories and localities, in order to be able to conceptualize processes that consolidated power relations and accentuated socio-environmental inequalities.

The eagle could not exist without the frog; and vice versa. This relentless zooming in and out, this continuous metamorphosis from eagle to frog and back, this hard labour of love can only be politically as well as intellectually driven. Such a politically engaging, necessity driven, empirically and conceptually rigorous, and deeply embodied explication of cities and environments is imperative today too. These are characteristics that make up what I call a scholarship of presence. A scholarship that pays as much attention to seemingly tedious details of everyday life (the number of inhabitants per room in Manchester’s Victorian tenements, the number of New York street vendors, the declining number of birds in a neighbourhood), as it does to developing a broader intellectual agenda and a political project that can produce new radical imaginaries for socio-environmental change.

This scholarship of presence is the reason why the work of the scholars I mentioned earlier resonates with us. And this scholarship of presence is what is needed today, I argue. We need a move from frog to eagle that will enable us to collect the stories and the data that can put flesh and bone onto abstract ideas. But we also need to put in the hard labour and courage to symbolize emerging radical imaginaries in ways that can empower them to become narratives performative of creating a new future. Our intellectual labour can contribute towards building narratives that not only help us make sense of the present, but also contribute towards constructing anarchaeology for a new future.

Needless to say, this is easier said than done. We may have today more research funding available than ever before, more publication outlets than ever before, a toolbox of methods larger than ever before, and a repository of concepts fuller than ever before. But after having rejected the conviction that science and ideas can change the world (positivism), after having spent over 3 decades discredited and deconstructed our once intellectual heroes, after having witnessed the demise of ideas that some had hoped would lead to alternative socio-environmental praxis (communism and socialism), we are understandably reluctant to propose or support new grand ideas, narratives and social imaginaries. The failed utopias of the past haunt us and weigh heavily upon constructing the utopias of the future.

Moreover, as we are embedded in academic institutions that are fast becoming part of the power landscapes of a corporatized world it is attractive to turn from public intellectuals into professionals; even our social impact is now measured through predefined parameters and metrics. It is therefore more attractive today to become contrarians/adversaries/ opponents of concepts or ideas than to be auxiliaries/supporters/deputies/ ambassadors of emerging political practices. It is more tempting and certainly more beneficial professionally (in terms of citation counts, impact, research funding, etc.) to be a professional public critic or to engage critically with the latest neologism, than to be a public intellectual; that is, to invest energy in empirical work in building new narratives out of real life empirics. I am as culpable as every other academic in doing just that.

But at the end of the day, maybe this is precisely the call of the Anthropocene. This is where our intellectual role lies today. Not in criticizing the concept; but perhaps in ignoring it all-together as an act of defiance to a newly emerging master narrative of capitalism. Maybe we should shift focus and energy instead in finding new symbolisms for the alternative imaginaries that emerge across the world and that need our urgent attention.

At times like these, times of environmental crisis and general spread of fear, a new project for autonomy, and the construction of alternative radical imaginaries emerges not as an intellectual exercise, but as a necessity for transformation and change. We need to be present again, co-researching, capturing processes of subjectification, new claims for re-commoning cities and natures alike. We need to document and narrate these stories, give them symbolic and ontological gravitas.

We may all love to hate geo-engineering advocates for their technological determinism (Corner, Parkhill, Pidgeon, & Vaughan, Citation2013), but we cannot capture dominant discourse and praxis without operationalizing our own qualitative or quantitative research. Engaging in a scholarship of presence, as described above, is the only way we can recapture the authority to speak about environmental change from economists, geoscientists, or technocrats. Rigorous empirical work in humanities, social sciences and urban professions (qualitative as well as quantitative) and hard labour to advance emerging concepts and methods is what is required if we, as scholars or urban practitioners want to recapture our role as co-producers of alternative socio-environmental futures. Resetting teaching and training agendas in geography, planning, environmental governance, design, is equally important for de-colonizing younger minds from the all prevailing social imaginary of the Anthropocene/Capitalocene.

We need to become again the frog that splashes into the murky waters of empirics in order to resurface with narratives of radical new practices like the ones I described earlier. But we also need to be the eagle again, unafraid of abstracting from the militant particularism of empirics, in order to show how these historically geographically specific stories do in fact matter to the rest of the world; they can act performatively as new paradigms if they gain enough symbolic weight and exposure.

And these exist and will continue to exist regardless of the naming or re-naming of the epoch. From Romania to Sao Paolo, and from Greece and Spain to China, new acts of defiance are performed every day (Crawshaw, Jackson, & Havel, Citation2010) producing new socio-environmental subject positions and demanding our attention.

Let us take these seriously – more seriously than a proposal to rename a geological epoch. Let us perform the labour of love requested to document and put these practices into narratives, let us add symbolic weight to their imaginaries. Let us, -as Luce Irigaray suggested- militate intellectually-politically for the impossible (Deutscher, Citation2002). Let us give symbolic form to wants and claims that do not yet exist, and let us make these the only possible futures. It is the thing we can do best. Let us do just that.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

References

- Berman, M. (1971). The politics of authenticity: Radical individualism and the emergence of modern society. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Biermann, F., Bai, X., Bondre, N., Broadgate, W., Arthur Chen, C.-T., Dube, O. P., … Seto, K. C. (2016). Down to earth: Contextualizing the Anthropocene. Global Environmental Change, 39, 341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.11.004

- Bonneuil, C., Fressoz, J.-B., & Fernbach, D. (2016). The shock of the Anthropocene: The earth, history, and us. London: Verso.

- Brand, P. (2007). Green subjection: The politics of neoliberal urban environmental management. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 31(3), 616–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00748.x

- Bristow, T. (2015). The Anthropocene lyric: An affective geography of poetry, person, place. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brondizio, E. S., O’Brien, K., Bai, X., Biermann, F., Steffen, W., Berkhout, F., … Chen, C.-T. A. (2016). Re-conceptualizing the Anthropocene: A call for collaboration. Global Environmental Change, 39, 318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.02.006

- Carson, R. (1962). Silent spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Castoriadis, C. (1987). The imaginary institution of society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Castree, N. (2014a). The Anthropocene and geography I: The back story. Geography Compass, 8, 436–449. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12141

- Castree, N. (2014b). The Anthropocene and geography III: Future directions. Geography Compass, 8, 464–476. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12139

- Castree, N. (2014c). Geography and the Anthropocene II: Current contributions. Geography Compass, 8, 450–463. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12140

- Castree, N. (2015). Changing the Anthropo(s)cene: Geographers, global environmental change and the politics of knowledge. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(3), 301–316. doi: 10.1177/2043820615613216

- Corner, A., Parkhill, K., Pidgeon, N., & Vaughan, N. E. (2013). Messing with nature? Exploring public perceptions of geoengineering in the UK. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 938–947. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.06.002

- Crawshaw, S., Jackson, J., & Havel, V. (2010). Small acts of resistance: How courage, tenacity, and ingenuity can change the world. New York, NY: Union Square.

- Crutzen, P. J., & Stoermer, E. F. (2000). The “Anthropocene”. International Geosphere–Biosphere Programme (IGBP). Global Change Newsletter, 41, 17–18.

- Dalby, S. (1992). Ecopolitical discourse: ‘environmental security’ and political geography. Progress in Human Geography, 16(4), 503–522. doi: 10.1177/030913259201600401

- Deutscher, P. (2002). A politics of impossible difference: The later work of Luce Irigaray. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Fredriksen, A. (2016). Of wildcats and wild cats: Troubling species-based conservation in the Anthropocene. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(4), 689–705. doi: 10.1177/0263775815623539

- Gibson, K., Rose, D. B., & Fincher, R. (2015). Manifesto for living in the Anthropocene. Brooklyn, NY: punctum books.

- Guattari, F. (1989). Les trois écologies. Paris: Galilée.

- Hamilton, C., Bonneuil, C., & Gemenne, F. (2015). The Anthropocene and the global environmental crisis. New York: Routledge.

- Head, L. (2015). Hope and grief in the Anthropocene: Re-conceptualising human-nature relations. New York: Routledge.

- Hulme, M. (2015). Changing what exactly, and from where? A response to Castree. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(3), 322–326. doi: 10.1177/2043820615613227

- Kaika, M. (2005). City of flows: Nature, modernity and the city. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kaika, M. (2011). Autistic architecture: The fall of the icon and the rise of the serial object of architecture. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(6), 968–992. doi: 10.1068/d16110

- Kaika, M. (2017). ‘Don’t call me resilient again!’: The new urban agenda as immunology … or … what happens when communities refuse to be vaccinated with ‘smart cities’ and indicators. Environment and Urbanization, 29(1), 89–102. doi: 110.1177/0956247816684763

- Kaika, M., & Ruggiero, L. (2018). The academic article as a collective “labour of love”. In N. Gregson, M. Crang, J. Botticello, M. Calestani, A. Krzywoszynska, M. Kaika & L. Ruggiero (Eds.), Winners of the 2017 Jim Lewis prize. European Urban and Regional Studies, 25(1), 3–7. doi:10.1177/0969776417751503 (Vol. 25, pp. 3–7). doi: 10.1177/0969776413484166

- Katz, C., & Kirby, A. (1991). In the nature of things: The environment and everyday life. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 16(3), 259–271. doi: 10.2307/622947

- Kirsch, S., & Mitchel, D. (1998). Earth-moving as the “measure of man”: edward teller, geographical engineering, and the matter of progress. Social Text, 54, 100–134. doi: 10.2307/466752

- Kulish, N. (2009). Homeless Poles look to the sea. The Global Edition of the New York Times (Saturday-Sunday August 1–2, 2009 ed., p. 3).

- Latimer, J., & Miele, M. (2013). Naturecultures? Science, affect and the non-human. Theory, Culture & Society, 30(7–8), 5–31. doi: 10.1177/0263276413502088

- Lazzarato, M. (2007). The making of the indebted man: Essay on the neoliberal condition. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e).

- Lefebvre, H. (1974). La production de l’Espace. Paris: Anthropos.

- Leichenko, R., & Mahecha, A. (2015). Celebrating geography’s place in an inclusive and collaborative Anthropo(s)cene. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(3), 327–332. doi: 10.1177/2043820615613252

- Lovbrand, E., Beck, S., Chilvers, J., Forsyth, T., Hedrén, J., Hulme, M., … Vasileiadou, E. (2015). Who speaks for the future of earth? How critical social science can extend the conversation on the Anthropocene. Global Environmental Change, 32, 211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.012

- Macfarlane, R. (2016). Generation Anthropocene: How humans have altered the planet for ever. The Guardian (Vol. Friday 1 April 2016, pp. no page number).

- Martindale, L. (2015). Understanding humans in the Anthropocene: Finding answers in geoengineering and transition towns. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 33(5), 907–924. doi: 10.1177/0263775815604914

- Martinez Alier, J. (2005). The environmentalism of the poor: A study of ecological conflicts and valuation. New Delhi, NY: Oxford University Press.

- McLean, J. E. (2016). The contingency of change in the Anthropocene: More-than-real renegotiation of power relations in climate change institutional transformation in Australia. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(3), 508–527. doi: 10.1177/0263775815618963

- Moore, J. W. (2015). Capitalism in the web of life: Ecology and the accumulation of capital. London: Verso.

- Purdy, J. (2015). After nature: A politics for the Anthropocene. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Randalls, S. (2015). Creating positive friction in the Anthropo(s)cenes. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(3), 333–336. doi: 10.1177/2043820615613262

- Reynolds, L., & Szerszynski, B. (2016). The post-political and the end of nature: The genetically modified organism. In J. Wilson & E. Swyngedouw (Eds.), The post-political and its discontents: Spaces of depoliticization, spectres of radical politics (pp. 48–65). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Rose, N. (2013). The human sciences in a biological age. Theory, Culture & Society, 30(1), 3–34. doi: 10.1177/0263276412456569

- Smith, N. (1984). Uneven development: Nature, capital and the production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Szerszynski, B. (2010). Reading and writing the weather: Climate technics and the moment of responsibility. Theory, Culture & Society, 27(2–3), 9–30. doi: 10.1177/0263276409361915

- Velicu, I., & Kaika, M. (2015). Undoing environmental justice: Re-imagining equality in the Rosia Montana anti-mining movement. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.10.012

- Wakefield, S., & Braun, B. (2014). Guest editorial. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(1), 4–11. doi: 10.1068/d3201int

- Watson, M. C. (2014). Derrida, stengers, latour, and subalternist cosmopolitics. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(1), 75–98. doi: 10.1177/0263276413495283

- Whitehead, M. (2014). Environmental transformations: A geography of the Anthropocene. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Yusoff, K. (2013). Geologic life: Prehistory, climate, futures in the Anthropocene. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31(5), 779–795. doi: 10.1068/d11512

- Yusoff, K. (2016). Anthropogenesis: Origins and endings in the Anthropocene. Theory, Culture & Society, 33(2), 3–28. doi: 10.1177/0263276415581021