ABSTRACT

Recent literature stresses the increasing importance of global innovation networks (GINs) as a mechanism to organize innovation across geographical space. This paper investigates why and to what extent citizenship diversity of the firm's employees relates to the engagement of small and medium size companies in GINs. Citizenship diversity provides knowledge about the institutional context of other countries, increased capabilities to deal with institutional differences, larger social networks to build GINs and a broader search space. Further, the paper examines how the absorptive capacity of firms mediates the relationship between citizenship diversity and GINs. The empirical study is based on a linked employee-employer dataset with 6,771 observations of innovative small and medium size firms in Sweden. It provides strong evidence that the engagement in GINs is positively related to citizenship diversity, depending, however, on the absorptive capacity of firms.

1. Introduction

The new global innovation landscape characterized by increased technological complexity, open models of innovation and modularization together with the upgrading of technological capabilities in middle income countries has dramatically altered the geography of innovation (Cano-Kollmann, Hannigan, & Mudambi, Citation2018). The globalization of manufacturing and production that spurred the studies on global production networks in the early 2000’s (Coe et al., Citation2004; Henderson, Dicken, Hess, Coe, & Yeung, Citation2002) is now being followed by a wave of globalization of innovation activities that builds upon complex networks of actors pinned down to specific locations all over the world. This new –networked- configuration of innovation activities at a global scale – which some authors refer to as global innovation networks (GINs) – is increasingly calling the attention of scholars in the intersect between economic geography, international business and innovation studies (Barnard & Chaminade, Citation2017; Cano-Kollmann et al., Citation2018; Cooke, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Cooke & Kemeny, Citation2017; Degelsegger-Marquez, Remøe, & Trienes, Citation2018; Martin, Aslesen, Grillitsch, & Herstad, Citation2018; Mudambi et al., Citation2018; Shakirov, Citation2017; Silva & Klagge, Citation2013). By bringing insights from the three disciplines scholars are trying to understand how innovation processes are organized at a global scale, who the main actors and drivers are and what the impact of these global networks for innovation is, both for companies and regions in both the developed and developing world.

Global innovation and knowledge networks are an important factor for regional development. Most contemporary studies have acknowledged that global innovation and knowledge networks contribute to path development in different regional innovation systems (Aslesen, Hydle, & Wallevik, Citation2017; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2016; Martin et al., Citation2018; Trippl, Grillitsch, & Isaksen, Citation2017). GINs are considered to be crucial particularly for peripheral regions with limited local knowledge resources (Grillitsch & Nilsson, Citation2015; Trippl et al., Citation2017) and in institutionally and organizationally thin regional innovation systems (Chaminade & Plechero, Citation2015). GINs can play an important role as a complementary or compensatory mechanism to local or regional knowledge linkages (Fitjar & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013; Grillitsch & Nilsson, Citation2015; Mudambi et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, there is growing amount of evidence on the role of the geography of networks on the degree of novelty of innovations which suggests that local and regional linkages are associated with incremental innovation while global linkages tend to lead to more radical innovations. The underlying rationale is that local and regional networks tend to provide access to similar knowledge (Asheim & Isaksen, Citation1997; Visser & Boschma, Citation2004) while GINs enable the firm to tap into new pools of knowledge (Herstad, Aslesen, & Ebersberger, Citation2014; Laursen & Salter, Citation2006; Plechero & Chaminade, Citation2016). It follows from this line of argument that GINs are desirable if the aim is to achieve innovations with higher degrees of novelty.

Given the potential role of GINs for regional development, it is critical to understand the factors that enable or constrain companies and other organizations located in a particular region to engage in GINs. From existing evidence we know that firm-specific characteristics such as the level of education of the workforce, research and development activities, exports, foreign ownership or size are positively related to the propensity of firms to engage in GINs (Ebersberger & Herstad, Citation2013). However, with the sole exception of Solheim and Fitjar (Citation2018) the issue of diversity of the labour force in terms of country of origin has been widely neglected as a factor influencing the propensity of firms to engage in GINsFootnote1, Footnote2.

We argue that institutional barriers between national boundaries are a specific and fundamental challenge for firms’ engagement in GINs and that citizenship diversity can alleviate this challenge through several causal mechanisms, namely by providing knowledge about the institutional context of the migrants’ home countries, by enhancing firms’ capabilities to cope with institutional differences (Grillitsch, Citation2015), a broadened search space of firms (Ebersberger, Herstad, Iversen, Kirner, & Som, Citation2011; Laursen, Citation2012; Østergaard, Timmermans, & Kristinsson, Citation2011) as well as social networks to individuals and organizations located in other countries (Agrawal, Cockburn, & McHale, Citation2006; Saxenian & Sabel, Citation2008).

We test the proposition that firms with a diverse labour force, captured by the citizenship of the employees, engage more in GINs on a representative sample of 6,771 observations of innovative small and medium size firms generated from merging four waves of the Community Innovation Survey (CIS) in Sweden. The CIS provide information about the spatial configuration of firms’ innovation networks as well as numerous control variables. This data is merged with linked employer-employee data provided by the Statistical Office of Sweden (SCB) in order to measure diversity of the labour force. Instead of treating international linkages as a black box, this paper investigates the impact of diversity on innovation networks within Sweden, within Europe, outside Europe and global (networks with partners in all geographical areas) thus truly investigating GINs.

In this paper we focus on small and medium size companies (SMEs) for several reasons. First, small and medium size innovation performance is considered to be paramount for the dynamics of regions (Kemeny, Citation2011). Second, in line with the extensive literature on born globals (Knight & Cavusgil, Citation2004), there is growing evidence of the capacity of small firms to engage in GINs (Barnard & Chaminade, Citation2017) as well as their positive effect on the degree of novelty (Aslesen & Harirchi, Citation2015). However, most of the existing literature on the drivers of engagement in GINs tend to focus on large multinational companies. Can diversity of the employees in terms of citizenship support SMEs in their efforts to engage in global networks to innovate?

The paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 elaborates on the concept of firm-level citizenship diversity, and in particular why and how citizenship diversity contributes to the engagement of firms in GINs. Section 3 presents the empirical strategy followed by a discussion of the results in section 4. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Diversity and its effect on GINs

2.1. Citizenship diversity, firm performance and innovation

The role of diversity of the labour force on firm performance has long been discussed in management studies (Horwitz, Citation2005), but it has only recently been used in connection to innovation performance (Østergaard et al., Citation2011; Solheim & Fitjar, Citation2018). Existing empirical evidence suggests that the impact of diversity on the general performance of the firm is highly contingent on the type of diversity. Ruef, Aldrich, and Carter (Citation2003) distinguish between ascribed and achieved attributes of diversity; the ascribed attributes are related to demographic characteristics such as gender, age, ethnicity and nationality, while the acquired attributes are mostly related to education, experience or job function. The later are also referred to in the literature as job-related attributes. Generally speaking, job-related attributes of diversity, like educational background and functional background are positively related to firm performanceFootnote3 while the impact of other diversity attributes like gender, race or citizenship are often associated with conflicts and thus negative firm performance (Bell et al., Citation2010; Horwitz, Citation2005; Pelled, Citation1996) although the results are highly contingent of the group in which the analysis is performed (Shore et al., Citation2009). The negative impact of ascribed diversity on performance is generally explained in terms of conflicts, miscommunication and lack of trust of the different group or team members (Horwitz, Citation2005; Shore et al., Citation2009). Of all demographic traits of diversity, ethnicity has been identified as the one with potential to affect firm performance positively by bridging the knowledge gap with potential markets (Cox & Blake, Citation1991; cf Horwitz, Citation2005). For instance, Cooke and Kemeny (Citation2017) and Kemeny and Cooke (Citation2018) find that diversity of the workforce in terms of migrant origin is positively related to higher productivity, particularly in jobs that require complex-problem solving and are of high relational nature, thus suggesting a possible link between diversity and innovation.

The relationship between innovation and diversity has been far less studied. Simonen and McCann (Citation2008) provide evidence of a positive relationship between recruitment of labour from other regions and product and process innovations. Lee and Nathan (Citation2010) find that workforce and ownership diversity contributes to product and process innovations. The study by Nathan and Lee (Citation2013) reports a small but significant positive effect of diversity on firm innovation and surprisingly the effect is stronger for less knowledge-intensive sectors. Kerr (Citation2013) provides evidence for the US on how diversity of the workforce enabled by migration is positively related to innovation and entrepreneurship in organizations.

Interestingly, some of the attributes, which are considered to affect general firm performance negatively, are found to be positively related to innovation. Ozgen, Nijkamp, and Poot (Citation2013) show that diversity of foreign nationalities contributes to firm innovativeness. In a similar vein, Parrotta, Pozzoli, and Pytlikova (Citation2014) find that ethnic diversity is positively related to firms’ patenting behaviour. Østergaard et al. (Citation2011) find a positive relation between diversity in education years, education background and gender with innovation and a negative relation between diversity in age and innovation, while the results for ethnicity are not significant. The authors hypothesize that the diversity of the workforce is positively related to innovation if it helps the firm to tap into and combine different forms of knowledge needed to innovate thus pointing out to the role of innovation networks as a liaison between diversity and innovation. Analogously, Fey and Birkinshaw (Citation2005) found that partnerships, particularly with university, are positively related to R&D performance. However, such relationship is strongly mediated by the ‘openess to new ideas’ of the company.

2.2. Citizenship diversity and global innovation networks

The main aim of this section is to carve out why citizenship diversity of the firm affects engagement in GINs positively. We do this firstly by identifying the challenges for firms’ engagement in GINs, and secondly by developing the argument why and how citizenship diversity contributes to alleviating these challenges. GINs are understood as the globally organized web of collaborative interactions between different organizations (firms and/or non-firm organizations) engaged in knowledge production that is related to and resulting in innovation. Thus, a defining feature of GINs is that it concerns activities crossing national boundaries and on a global scale (Parrilli, Nadvi, & Yeung, Citation2013). This implies that firms have to overcome institutional barriers in the form of differences in laws and regulations such as intellectual property rights, business law, labour law, and environmental regulations; differences in how the legal system works; as well as more informal aspects such as divergent norms, values, believes and how to interact with business partners. Recent studies show that managing the complexity of different institutional contexts is one of the most important barriers for firms as regards their participation in GINs and that consequently the ability to cope with different institutional environments should be positively related with the propensity of firms to engage in internationalization of production and innovation activities (Alvandi, Chaminade, & Lv, Citation2014; Dachs et al., Citation2012; Hsu, Lien, & Chen, Citation2015).

We argue below that citizenship diversity of the workforce helps firms to overcome institutional barriers erected between nation states through the following mechanisms: i) the provision of knowledge about the institutional context in other countries, ii) the increased capabilities to deal with institutional differences, iii) social network effects, and iv) a broader search space.

First, migrant workers who had exposure to their home country, for instance when growing-up, working or interacting with family and friends, will have some knowledge about the institutional context of their home country. This may put such migrants in an advantageous position to deal with the legal and regulatory environment in their home country. Furthermore, familiarity with the socio-cultural context facilitates knowledge exchange and interactive learning (Boschma, Citation2005). In other words, less is lost in translation.

Second, citizenship diversity may also increase the capability of firms to cope with different contexts beyond the migrants’ home countries. One reason is that integrating individuals with divergent institutional heritage is a social learning process of how to communicate and interact without misunderstandings, how to build relationships and trust, and how to exchange knowledge despite institutional differences. This learning process potentially builds the capabilities of individuals and firms to overcome institutional barriers that exist with collaboration partners in different parts of the world. This is important not only for establishing global networks but also in making them a successful learning experience contributing to the innovation performance of firms. This resonates well with empirical evidence showing that the impact of internationalization on firm's productivity is highly influenced by previous international experience, particularly international breath – that is the number of countries in which the firm operates (Kafouros, Buckley, & Clegg, Citation2012). However, too much diversity in the networks might also impact negatively the performance of the firm insomuch as network complexity increases (Bahlmann, Citation2014). Another reason is related to the fact that migrants, particularly research migrants, are likely to collaborate with individuals from their home country, even when those are located in third countries (Scellato, Franzoni, & Stephan, Citation2015). In this respect, citizenship diversity might help the establishment of collaborations for innovation not only in the home country but also worldwide.

Third, citizenship diversity goes hand in hand with a greater breath of social networks, on which a firm can draw for engaging in GINs. The relevance of social networks in this regard is justified by i) the higher likelihood of establishing social networks in close geographic proximity and ii) the durability of social networks over time even if individuals change locations. Social networks are often forged when individuals interact face-to-face, at for instance university, their workplace or where they live. In this regard, it has been shown that regional labour mobility is an important factor explaining local knowledge spillovers (Breschi & Lissoni, Citation2009) and that firms dominantly recruit regionally in order to source knowledge (Grillitsch, Tödtling, & Höglinger, Citation2015; Plum & Hassink, Citation2013). Geographic proximity can thus be seen as intermediary factor that increases the likelihood that people meet, interact, and build social relationships, even though not all individuals and firms in a given location are equally engaged in local networking or have equal access to networks (Giuliani, Citation2007; Morrison, Citation2008).

While co-location increases the propensity to build social networks, they are maintained when people move to other places (Agrawal et al., Citation2006; Saxenian & Sabel, Citation2008; Trippl, Citation2013). Social networks facilitate the exchange of information and interactive learning as well as reduce the likelihood of opportunistic behaviour (Granovetter, Citation1985, Citation2005). Thus social networks contribute to overcoming geographic distance and institutional barriers. This implies that the social networks that individuals have built over time where they grew up, lived and worked can potentially be activated in order to facilitate the engagement of firms in GINs (Crescenzi, Nathan, & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2016). As regards GINs, it can thus be expected that the social networks of migrants to their home country are an important factor strengthening a firm’s ability to engage and draw value from GINs (Oettl & Agrawal, Citation2008).

Forth, citizenship diversity and the related social networks translate into a broader information and knowledge search space of firms (Laursen, Citation2012; Østergaard et al., Citation2011). A wide search space in the context of GINs means that firms are able to draw on reliable information about potential collaboration partners for their innovation activities in different parts of the world. The wide search space may be attributed to migrants' knowledge of relevant organizations in their home country, their ability to gather such knowledge through social networks, and their understanding of social and institutional particularities.

In sum, we have carved out four mechanisms through which citizenship diversity of the workforce facilitates firms’ engagement in GINs, relating to the direct benefit of understanding the institutional environment of the migrants' home country, the indirect benefit of developing firm capabilities to deal with institutional differences, social network effects, and a broader search space. As discussed, these mechanisms directly address some of the key complexities and challenges of firms’ engagement in GINs, which is why we consider that citizenship diversity is a causal driver for GINs. Hence, our first hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1: Firms with a high degree of citizenship diversity have a higher likelihood to participate in global innovation networks.

2.3. Citizenship diversity, absorptive capacity and GINs

So far, we discussed why citizenship diversity at the level of the firm should be positively related to the likelihood that firms engage in GINs. However, does this apply to all firms equally? There are important reasons to assume that the effect of firm-level citizenship diversity on the engagement in GINs is mediated by a number of factors related to the absorptive capacity of the firm (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990; Zahra & George, Citation2002), particularly the educational level of the workforce. Fitjar and Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2014) find that education increases the likelihood of Norwegian firms to establish international collaboration linkages at the expense of local links. Furthermore, Solheim and Fitjar (Citation2018) argue that citizenship may be related to performance and the propensity of firms to collaborate internationally to the extent to which they are highly educated or hold higher positions in the company.

GINs are characterized by high complexity, partly due to the need of dealing with different institutional contexts. Furthermore, the purpose of establishing innovation networks is to engage in learning processes, which largely depends on the capacity of firms to identify relevant knowledge and appropriate it for innovations. Lacking absorptive capacity, it will be difficult for firms to establish and draw benefits from GINs. Hence, firm-level citizenship diversity is expected to be largely ineffective for firms with low levels of absorptive capacity. In contrast, for firms with high levels of absorptive capacity, we expect a strong relationship between GINs and firm-level citizenship diversity. Hence, our second hypothesis is the following:

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between citizenship diversity and firms’ participation in global innovation networks is stronger for firms with a high absorptive capacity.

3. Empirical strategy

3.1. Data sources

The study uses data provided by the Statistical Office of Sweden (SCB) comprising the Community Innovation Survey (CIS), longitudinal individual registry data, business registry data, firm and establishment dynamic data and business statistics data. The CIS is a large-scale European survey that captures innovation activities and innovation networks of firms. The methodology for the CIS has been developed by Eurostat and implemented by the national statistical offices of the participating countries. The CIS is conducted in two-year intervals and for the purpose of increasing representativeness we merge four waves covering the periods 2004–2006, 2006–2008, 2008-2010, and 2010–2012. In the analysis, we include only firms with less than 250 employees (small- and medium-sized enterprises) because the link between diversity and international engagement is more difficult to establish for large firms with potentially many establishments abroad and the possibility and need to recruit international staff to cover foreign markets. The longitudinal individual registry includes among others data on individuals’ occupations, education, citizenship, and respective employers for each individual registered in Sweden and aged above 16 years. The individual registry data is measured each year on the 31st of December except for some variables like employment for which the measurement is undertaken in November. In order to account for this, the analysis is performed on individual data one year before each CIS period. For instance, individual registry data for 2003 is used in combination with the CIS wave covering the period from 2004 to 2006. As the database includes all individuals registered in Sweden, important characteristics of the workforce of Swedish firms can be represented. In particular, it constitutes a highly reliable source for measuring citizenship diversity as well as human capital within a firm. The business registry data, firm establishment and dynamics data and business statistics data are used to construct the control variables as further explained below.

3.2. Dependent variable

The dependent variable captures whether a firm had innovation collaborations in different world regions during the specific period of each CIS wave. The following world regions are covered in the CIS: Sweden, Europe, USA, China, India, and Others. This allows us to define different scales of innovation collaborations:

Swedeni,t = 1 if firm i had innovation collaborations in Sweden in time period t, otherwise 0

Europei,t = 1 if firm i had innovation collaborations in Europe (excluding Sweden) in time period t, otherwise 0

Outside Europei,t = 1 if firm i had innovation collaborations in USA, China, India or others in time period t, otherwise 0

Globali,t = 1 if firm i had innovation collaborations in all world regions in time period t, otherwise 0

3.3. Independent variables

The operationalization of diversity depends on the conceptual idea this construct represents. Harrison and Klein (Citation2007) distinguish between diversity understood as separation, variety or disparity. Separation aims to capture differences in position or opinion between group members that potentially reduce cohesiveness and introduces conflict. Variety conceptualizes diversity in a positive manner as complementary types of knowledge or experience. Disparity concerns differences in the share held by individual agents in socially valued assets such as income, power, or status. In the context of this paper, citizenship diversity is conceptualized as a proxy for variety in social networks, knowledge about different institutional contexts and search spaces, which facilitate the engagement of firms in GINs. Hence, the Blau index, a typical and frequently used operationalization of diversity, is used to operationalize citizenship diversity:(1) where p denotes the share of highly qualified individuals belonging to citizenship groups k = 1, … , K in the total of highly qualified staff of a firm.

Highly qualified individuals refer to those who are in a position to influence innovation networks. They are identified using occupational data available in the longitudinal individual register. The Swedish classification of occupations SSYK 96 follows the International Standard Classification of Occupations ISCO-88 and orders occupations in a hierarchical framework. It captures the ‘set of tasks or duties designed to be executed by one person’, ‘the degree of complexity of constituent tasks’, and ‘the field of knowledge required for competent performance of the constituent tasks’ (Statistical Office of Sweden, Citation1998, p. 17). SSYK classifies occupations in 10 major groups out of which group one (managers), two (professionals) and three (technicians and associate professionals) contain occupations that are very relevant in innovation processes and require high skill levels. Individuals classified in one of these three groups are thus identified as highly qualified. Occupational data has important advantages over educational data because it captures the actual work individuals are performing at present while educational data may refer to qualifications that were required long time back or that are not utilized in the activities and tasks of an employee. The citizenship groups provided by the longitudinal individual registry comprise: Sweden, Nordic countries (but Sweden), Europe (but Nordic countries), Africa, North America, South America, Asia, and other.

In hypothesis 2 we test whether the relationship between the engagement in GINs and citizenship diversity is mediated by the absorptive capacity of a firm. The notion of absorptive capacity stipulates that firm-internal knowledge and skills are a precondition for appropriating and using new knowledge acquired through innovation networks (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990; Zahra & George, Citation2002). Accordingly, the absorptive capacity is captured by the qualification of the human capital of a firm measured as the share of highly qualified staff in the total staff of a firm based on occupational data as described above.

The measurement and data source of all control variables used in the study are described in and Annex 1 reports descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Description of control variables.

3.4. Identification strategy

Data on innovation networks is per definition only available for firms that are innovation active, thus potentially causing a selection bias (Heckman, Citation1979). Consequently, a Heckman selection model is applied similar to other studies using CIS data (Ebersberger & Herstad, Citation2012; Frenz & Ietto-Gillies, Citation2009; Herstad et al., Citation2014; Lööf & Heshmati, Citation2002) with the following selection model:(2) The dependent variable captures firms that are active in innovation and is a function of firm characteristics (firm), effects of location in a metropolitan area (metropolitan), industry effects (industry), time effects (time) and random errors (ε) with ϵ ∼ N(0,1). As regards firm characteristics, the selection equation includes human capital, foreign sales, size, the capacity to finance innovations and whether the firm is new. The latter two variables are relevant to explain whether a firm is innovation active but have no theoretical or statistical relationship with the likelihood that firms engage in GINs. The function is estimated with a probit regression applying standard errors clustered at the level of the firm in order to adjust them for repeated observations. The coefficients of the selection equation are presented in . As expected the qualification of the human capital, foreign sales and firm size are positively related to the probability that firms are innovative. Also, firms with a strong financial capacity and firms that have been established within three years before the respective CIS wave are more likely to be innovative. Somewhat surprising is the negative effect of being located in a metropolitan area, suggesting that negative agglomeration economies outweigh positive ones. A potential interpretation is that one of the main effects of metropolitan areas, namely access to a thick labour market, may be absorbed in the human capital indicator at the level of the firm.

Table 2. Probit Regression on the selection equation.

The inverse Mills ratio (imr) is calculated from the above probit regression:(3) where

stands for the linear predictors of the selection function. The inverse Mills ratio is included as one of the explanatory variables in the outcome model, which is used to test hypothesis 1:

(4) The outcome model explains the engagement of firms in GINs (global) as a function of citizenship diversity (diversity), a set of firm characteristics (firm), the effect of location in a metropolitan area (metropolitan), the inverse Mills ratio (imr), industry characteristics (industry), time effects (time) and random errors (ε) with ϵ ∼ N(0,1). The firm characteristics include human capital, intramural R&D, international networks within the corporate group, foreign ownership, foreign sales, and size. The outcome model is estimated applying probit regression and standard errors clustered at the level of the firm.

In order to investigate whether the effect of citizenship diversity is mediated by the level of human capital (human_capital) an interaction variable between the two variables is introduced in the outcome equation:(5) The main interest of the interaction model is to identify the relationship between citizenship diversity and the engagement of firms in GINs conditional to the level of human capital. It is not uncommon that the average marginal effect of a variable at certain levels of the specified condition is significant although the interaction term itself is insignificant, which is why the average marginal effects are reported (Brambor, Clark, & Golder, Citation2006).

4. Results

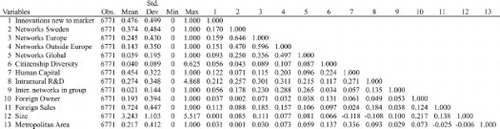

presents basic distributional statistics. The total sample comprises 14,035 observations out of which approximately half are from innovative firms. Out of the observations for innovative firms 37% have networks with Swedish partners, 25% with partners in Europe but outside Sweden, 15% with partners located outside Europe, and 4% are truly global with networks in all world regions covered by this study. Overall the employment of non-Swedish staff is rather common among innovative firms. It turns out to be most likely (55%) for firms that maintain GINs compared to 31%, 38%, and 44% for firms with network partners in Sweden, Europe, and outside Europe respectively. However, the share of non-Swedish staff tends to be rather low and ranges between 2.89% for firms with innovation networks in Sweden and 4.50% for firms with GINs. The mean number of unique citizenship groups in a firm ranges between 1.4 and 1.9 for firms with Swedish and GINs respectively. The measure for citizenship diversity takes the lowest value for firms with networks in Sweden (0.0453) and turns out highest for firms with GINs (0.0782). Hence, the descriptive statistics provide an indication for a positive relationship between citizenship diversity and GINs. However, the results also indicate that this relationship may hold more generally for international innovation networks.

Table 3. Sample characteristics.

Before moving to the main focus of this paper, the identification of relationships between citizenship diversity and firms’ engagement in GINs, we confirm in that innovation networks indeed contribute to the innovativeness of firms. As information on innovation networks is only collected for firms that have declared to be innovative, it is not possible to use non-innovative firms as counterfactual. Hence, we investigate whether innovation networks make it more likely that firms have introduced innovations that are new to the world, which is the most radical form of innovation about which the CIS provides information. We introduce innovation networks at the four spatial scales investigated in the study and find indeed that all of them are positively and highly significantly correlated with the likelihood that firms introduce innovations new to the market.

Table 4. Probit regression: innovation networks on introduction of innovations new to the market.

tests the hypothesis that firms with a high degree of citizenship diversity have a higher likelihood to participate in GINs. It shows models without (Models 1–4) and with the inclusion of inter-firm networks (Models 5–8). The reason for showing these separately is that a high international engagement of firms can be the cause for high citizenship diversity. We take necessary precautions to control for this in the regressions through the following variables: foreign sales, foreign ownership, and most importantly intra-firm innovation networks. Neglecting intra-firm innovation networks, citizenship diversity is positively related to innovation collaborations at all investigated spatial scales (Models 1–4). However, if we include intra-firm networks, citizenship diversity only remains highly significant and positive for GINs (Model 8). Conversely, intra-firm networks are strongly related to innovation network with external partners at all geographical scales.

Table 5. Probit regression: citizenship diversity on innovation networks at different spatial scales.

The control variables exercise highly significant effects on innovation networks. There are three variables where the coefficient is substantial higher for GINs than for other spatial scales: human capital, firm size, and foreign sales. The first two variables are close proxies for the absorptive capacity of firms and therefore this pattern is not surprising as an increasing level of global engagement also increases complexity due to the need to coordinate a large number of units embedded in different institutional environments. Foreign sales is one of the mechanisms (besides citizenship diversity, global intra-firm collaboration, and foreign ownership) that can facilitate GINs by enlarging networks abroad, enhancing the search space for partners, and increasing capability to deal with institutional differences. However, foreign ownership, which has also been identified as a proxy for international engagement, is surprisingly not positively related to GINs and is even negatively correlated with networks at the European scale and outside Europe. This indicates that foreign ownership rather aims at capturing knowledge in Sweden than facilitating the capturing of knowledge of Swedish firms abroad. It is worth looking into this more deeply because the implication would be that foreign investments trigger larger knowledge out- than inflows and thereby endanger Swedish competitiveness. Location in a metropolitan area does not positively affect engagement in GINs, which is in line with recent empirical studies (Chaminade & Plechero, Citation2015; Grillitsch & Nilsson, Citation2015; Tödtling, Grillitsch, & Höglinger, Citation2012).

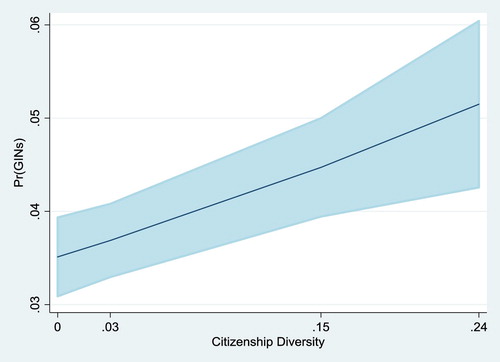

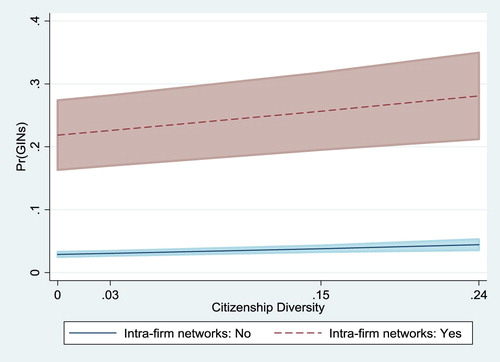

In order to interpret these results, as well as and present the likelihood to engage in GINs conditional to certain levels of citizenship diversity and conditional to whether the firm has global intra-firm networks or not. The chosen levels of citizenship diversity are 0, 0.03, 0.15, and 0.24, which correspond respectively to the 50th (no citizenship diversity), 75th, 90th, and 95th (high citizenship diversity) percentiles. Comparing the 50th and 95th percentiles, (and Column 1/) shows that the likelihood to engage in GINs increases from 3.5% to 5.2%. (and Columns 2 & 3/) shows that i) intra-firm networks play a crucial role, and that ii) firms with a high citizenship diversity tend to have a higher likelihood to engage in GINs. The likelihood to engage in GINs at the 50th and 95th percentiles are 2.9% and 4.4% respectively for firms without intra-firm networks. For firms with global intra-firm networks the likelihood to engage in GINs is 21.9% for firms with no citizenship diversity (50th percentile) and 28.2% for highly diverse firms (95th percentile).

Figure 1. Likelihood to engage in GINs at specific levels of Citizenship Diversity (with 90% confidence intervals).

Figure 2. Likelihood to engage in GINs at specific levels of Citizenship Diversity and inter-firm networks (with 90% confidence intervals).

Table 6. Likelihood to engage in GINs conditional to fixing citizenship diversity and intra-firm networks at the indicated levels.

The above analysis provides support for the assumed relationship between citizenship diversity and firms’ participation in GINs (hypothesis 1). As robustness check, depicts how sensitive the relationship is to the included control variables. The first line shows the coefficient of citizenship diversity. The following rows report, which control variables are included in the respective models. Accordingly, in all cases the coefficient remains highly significant and shows only minor deviations in magnitude between 0.8793 and 1.0494 depending on which control variable is excluded.

Table 7. Probit regression: citizenship diversity on GINs.

The results provide empirical evidence that citizenship diversity at the level of the firm is positively related to the likelihood that firms engage in GINs. However, does this apply to all firms equally? In the theory section, we have argued that the effect of citizenship diversity on the participation of firms in GINs depends on the absorptive capacity of firms. Without the cognitive ability to identify relevant knowledge, exchange knowledge and create new knowledge in GINs, citizenship diversity is assumed to be ineffective.

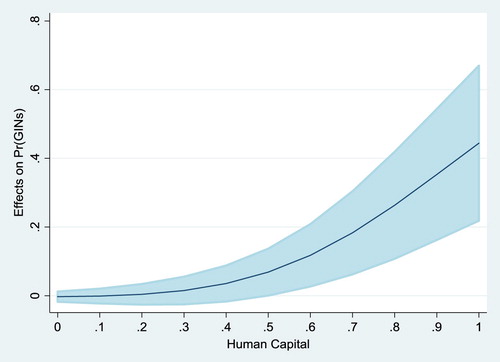

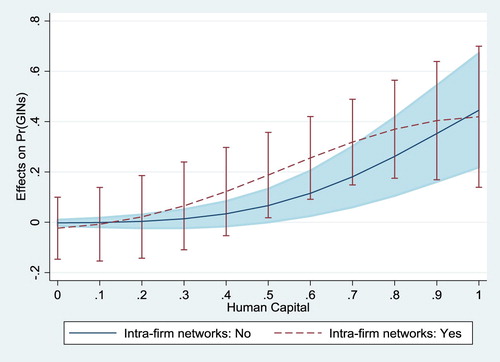

In order to investigate this relationship, we interact the citizenship diversity with the human capital variable. presents the average marginal effects of citizenship diversity on GINs conditional to certain levels of human capital and conditional to whether global intra-firm innovation networks exist. The results show that citizenship diversity has no effect for firms with low levels of human capital but a highly positive and significant effect for firms with high shares of qualified staff over the total staff of the firm, thus backing hypothesis 2. Graphically, the average marginal effects of citizenship diversity at different levels of human capital are depicted in . The average share of qualified employees in the sample is approximately 45%, which is the level at which the citizenship diversity variable turns significant. In the sample, 1.051 firms (16%) have a human capital level of larger than 90% and 527 firms (8%) of 100%. For these firms the marginal effects come up to 0.3529 and 0.4441 respectively (, Column 1). This general pattern holds also if average marginal effects are calculated conditional to the existence of global intra-firm networks. It suggests that even if intra-firm innovation networks exist, citizenship diversity only contributes positively to the engagement in GINs if the firm has a certain level of absorptive capacity. At 100% human capital, the average marginal effect has a similar magnitude for both, firms with and without intra-firm networks (). However, the pattern indicates that the average marginal effect increases faster with human capital for firms with intra-firm networks. However, due to the high standard errors, this difference in shape cannot be established statistically.

Figure 3. Average marginal effects of citizenship diversity on the probability to engage in GINs at specific levels of human capital (with 90% confidence intervals).

Figure 4. Average marginal effects of citizenship diversity on the probability to engage in GINs at specific levels of human capital and intra-firm networks (with 90% confidence intervals).

Table 8. Average marginal effect of citizenship diversity on the likelihood to engage in GINs conditional to fixing human capital and intra-firm networks at the indicated levels.

In summary, our results suggests that citizenship diversity has a strong effect on the likelihood that firms engage in GINs contingent to the level of absorptive capital, measured here as human capital.

5. Conclusions

In the last decades, we have witnessed an increase in the global distribution of innovation networks (De Prato & Nepelski, Citation2012; Herstad et al., Citation2014) and a number of studies have shown how GINs significantly contribute to the innovativeness and economic performance of firms (Plechero & Chaminade, Citation2016) and regions. But engaging in truly global networks implies that actors need to overcome institutional barriers associated with location in different regional and national contexts. Therefore, we argue in this paper that citizenship diversity at the level of the firm should be an important factor explaining the engagement of firms in GINs. In contrast to most of the existing literature that treats international linkages as a black box, this paper investigates the impact of diversity on innovation networks outside Sweden but within Europe, Outside Europe and truly global (networks with partners in all geographical areas). Our results indeed show that firms with a high citizenship diversity are more likely to have truly global innovation linkages and that in contrast, we have no evidence that high citizenship diversity affects the propensity of firms to engage in other forms of international innovation networks.

While diversity has many dimensions, it is argued that diversity related to the country of citizenship of the firm’s workforce is highly relevant for GINs as it relates to the national institutional context conditions in which individuals have been socialized. Conceptually we identify four reasons why citizenship diversity should be positively related to GINs. Workers with different citizenships have knowledge about the institutional context conditions in their respective home countries, thus reducing institutional barriers related to GINs. In addition, citizenship diversity within a firm may stimulate learning about how to deal with institutional differences, i.e. how to overcome institutional barriers. Furthermore, firm-level citizenship diversity is related to the breath of social networks. For instance, studies have shown that migrants’ social networks with their home countries can support innovation collaboration (Agrawal et al., Citation2006; Trippl, Citation2013). Finally, the capability to overcome institutional barriers and social networks contribute to a broad search space for information and knowledge (Ebersberger et al., Citation2011; Laursen, Citation2012; Østergaard et al., Citation2011), for instance about organizations in different countries that hold required competencies for innovation processes.

Our empirical study also shows that that the relationship between firm-level citizenship diversity and engagement in GINs is contingent on the absorptive capacity of firms. Without a minimum cognitive level, firms will not be able to successfully search, capture and integrate the knowledge acquired through global networks and manage the complexity of internationalization. As absorptive capacity increases, captured by the qualification of the labour force, the relationship between firm-level citizenship diversity and engagement in GINs becomes stronger.

In conclusion, our discussion and analysis provide novel inputs to the emergent scholarly work on GINs by providing insights into the mechanisms through which firm-level citizenship diversity is expected to stimulate small and medium-sized firms’ participation in GINs (as a distinct form of international networks) as well as evidence of their positive relation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Markus Grillitsch http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8406-4727

Cristina Chaminade http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6739-8071

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The authors refer to partners in general, without specifying the type of partnership or if the partnership is related to innovation. Additionally, the authors do not make a distinction between international and global networks.

2 A particular subset of literature focuses only on the diversity of the top management. Carpenter & Fredrickson (Citation2001), using data of US firms, find that the diversity of the top management team is positively related to a higher propensity to pursue innovative strategies in global markets. Barkema & Shvyrkov (Citation2007) provide evidence that diversity of the top management team has a positive impact on the foreign expansion of the firm but that the final effect is mediated by the tenure of the team as well as the cultural distance between the different managers. Caligiuri, Lazarova, & Zehetbauer (Citation2004) find that the diversity of nationalities among top managers positively influences the propensity to internationalize through exports, foreign direct investments and through recruitment. Furthermore their evidence shows that diversity of the top management team has special impact on the breath of internationalization, that is the number of countries in which the firm operates which, in turn, as discussed earlier has a higher impact on productivity (Kafouros et al., Citation2012).

3 Diversity in educational level is however negatively associated with performance (Bell et al., Citation2010).

References

- Agrawal, A., Cockburn, I., & McHale, J. (2006). Gone but not forgotten: Knowledge flows, labor mobility, and enduring social relationships. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(5), 571–591. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbl016

- Alvandi, K., Chaminade, C., & Lv, P. (2014). Commonalities and differences between production-related foreign direct investment and technology-related foreign direct investment in developed and emerging economies. Innovation and Development, 4(2), 293–311. doi: 10.1080/2157930X.2014.923615

- Asheim, B. T., & Isaksen, A. (1997). Location, agglomeration and innovation: Towards regional innovation systems in Norway? European Planning Studies, 5(3), 299–330. doi: 10.1080/09654319708720402

- Aslesen, H. W., & Harirchi, G. (2015). The effect of local and global linkages on the innovativeness in ICT SMEs: Does location-specific context matter? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 27(9–10), 644–669. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2015.1059897

- Aslesen, H. W., Hydle, K. M., & Wallevik, K. (2017). Extra-regional linkages through MNCs in organizationally thick and specialized RISs: A source of new path development? European Planning Studies, 25(3), 443–461. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1273322

- Bahlmann, M. D. (2014). Geographic network diversity: How does it affect exploratory innovation? Industry and Innovation, 21(7–8), 633–654. doi: 10.1080/13662716.2015.1012906

- Barkema, H. G., & Shvyrkov, O. (2007). Does top management team diversity promote or hamper foreign expansion? Strategic Management Journal, 28(7), 663–680. doi: 10.1002/smj.604

- Barnard, H., & Chaminade, C. (2017). Openness of innovation systems through global innovation networks: A comparative analysis of firms in developed and emerging economies. International Journal of Technological Learning, Innovation and Development, 9(3), 269. doi: 10.1504/IJTLID.2017.087426

- Bell, S. T., Villado, A. J., Lukasik, M. A., Belau, L., & Briggs, A. L. (2010). Getting specific about demographic diversity variable and team performance relationships: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management.

- Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74. doi: 10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M.. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpi014

- Breschi, S., & Lissoni, F. (2009). Mobility of skilled workers and co-invention networks: An anatomy of localized knowledge flows. Journal of Economic Geography, 9(4), 439–468. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbp008

- Caligiuri, P., Lazarova, M., & Zehetbauer, S. (2004). Top managers’ national diversity and boundary spanning: Attitudinal indicators of a firm’s internationalization. Journal of Management Development, 23(9), 848–859. doi: 10.1108/02621710410558459

- Cano-Kollmann, M., Hannigan T. J., & Mudambi, R. (2018). Global innovation networks – organizations and people. Journal of International Management, 24(2), 87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2017.09.008

- Carpenter, M. A., & Fredrickson, J. W. (2001). Top management teams, global strategic posture, and the moderating role of uncertainty. Academy of Management Journal, 44(3), 533–545.

- Chaminade, C., & Plechero, M. (2015). Do regions make a difference? Regional innovation systems and global innovation networks in the ICT industry. European Planning Studies, 23(2), 215–237. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.861806

- Coe, N. M., Hess, M., Yeung, H. W.-C., Dicken, P., & Henderson, J. (2004). Globalizing’ regional development: A global production networks perspective. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 29(4), 468–484. doi: 10.1111/j.0020-2754.2004.00142.x

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. doi: 10.2307/2393553

- Cooke, A., & Kemeny, T. (2017). Cities, immigrant diversity, and complex problem solving. Research Policy, 46(6), 1175–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2017.05.003

- Cooke, P. (2013a). Global innovation networks, territory and services innovation. In Service industries and regions (pp. 109–133). Berlin: Springer.

- Cooke, P. (2013b). Global production networks and global innovation networks: Stability versus growth. European Planning Studies, 21(7), 1081–1094. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.733854

- Cox, T. H., & Blake, S. (1991). Managing cultural diversity: Implications for organizational competitiveness. The Executive, 5, 45–56.

- Crescenzi, R., Nathan, M., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2016). Do inventors talk to strangers? On proximity and collaborative knowledge creation. Research Policy, 45(1), 177–194. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2015.07.003

- Dachs, B., Kampik, F., Scherngell, T., Zahradnik, G., Hanzl-Weiss, D., Hunya, G., … Waltraut, U. (2012). Internationalisation of business investments in R&D and analysis of their economic impact. Luxembourg: European Commission.

- De Prato, G., & Nepelski, D. (2012). Global technological collaboration network: Network analysis of international co-inventions. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(3), 1–18.

- Degelsegger-Marquez, A., Remøe, S. O., & Trienes, R. (2018). Regional knowledge economies and global innovation networks - the case of Southeast Asia. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 9(1), 66–86. doi: 10.1108/JSTPM-06-2017-0027

- Ebersberger, B., & Herstad S. J. (2012). Go abroad or have strangers visit? On organizational search spaces and local linkages. Journal of Economic Geography, 12(1), 273–295. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbq057

- Ebersberger, B., & Herstad, S. J. (2013). The relationship between international innovation collaboration, intramural R&D and SMEs’ innovation performance: A quantile regression approach. Applied Economics Letters, 20(7), 626–630. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2012.724158

- Ebersberger, B., Herstad, S., Iversen, E. J., Kirner, E., & Som, O. (2011). Open innovation in Europe: effects, determinants and policy.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities; what are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(9), 1105–1121.

- Fey, C. F., & Birkinshaw, J. (2005). External sources of knowledge, governance mode, and R&D performance. Journal of Management, 31(4), 597–621. doi: 10.1177/0149206304272346

- Fitjar, R. D., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Firm collaboration and modes of innovation in Norway. Research Policy, 42(1), 128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.05.009

- Fitjar, R. D., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2014). The geographical dimension of innovation collaboration: Networking and innovation in Norway. Urban Studies, 51(12), 2572–2595. doi: 10.1177/0042098013510567

- Frenz, M., & Ietto-Gillies, G. (2009). The impact on innovation performance of different sources of knowledge: Evidence from the UK Community Innovation Survey. Research Policy, 38(7), 1125–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2009.05.002

- Giuliani, E. (2007). The selective nature of knowledge networks in clusters: Evidence from the wine industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(2), 139–168. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbl014

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. doi: 10.1086/228311

- Granovetter, M. (2005). The impact of social structure on economic outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1), 33–50. doi: 10.1257/0895330053147958

- Grillitsch, M. (2015). Institutional layers, connectedness and change: Implications for economic evolution in regions. European Planning Studies, 23(10), 2099–2124. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2014.1003796

- Grillitsch, M., & Nilsson, M. (2015). Innovation in peripheral regions: Do collaborations compensate for a lack of local knowledge spillovers? The Annals of Regional Science, 54(1), 299–321. doi: 10.1007/s00168-014-0655-8

- Grillitsch, M., Tödtling, F., & Höglinger, C. (2015). Variety in knowledge sourcing, geography and innovation: Evidence from the ICT sector in Austria. Papers in Regional Science, 94(1), 25–43.

- Harrison, D. A., & Klein, K. J. (2007). What’s the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1199–1228. doi: 10.5465/amr.2007.26586096

- Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161. doi: 10.2307/1912352

- Henderson, J., Dicken, P., Hess, M., Coe, N., & Yeung, H. W.-C. (2002). Global production networks and the analysis of economic development. Review of International Political Economy, 9(3), 436–464. doi: 10.1080/09692290210150842

- Herstad, S. J., Aslesen, H. W., & Ebersberger, B. (2014). On industrial knowledge bases, commercial opportunities and global innovation network linkages. Research Policy, 43, 495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.003

- Horwitz, S. K. (2005). The compositional impact of team diversity on performance: Theoretical considerations. Human Resource Development Review, 4(2), 219–245. doi: 10.1177/1534484305275847

- Hsu, C.-W., Lien, Y.-C., & Chen, H. (2015). R&D internationalization and innovation performance. International Business Review, 24(2), 187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.07.007

- Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2016). Path development in different regional innovation systems. A conceptual analysis. In D. Parrilli, R. D. Fitjar, & A. Rodriguez-Pose (Eds.), Innovation drivers and regional innovation strategies (pp. 66–84). New York and London: Routledge.

- Kafouros, M. I., Buckley, P. J., & Clegg, J. (2012). The effects of global knowledge reservoirs on the productivity of multinational enterprises: The role of international depth and breadth. Research Policy, 41(5), 848–861. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.007

- Kemeny, T. (2011). Are international technology gaps growing or shrinking in the age of globalization? Journal of Economic Geography, 11(1), 1–35. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbp062

- Kemeny, T., & Cooke, A. (2018). Spillovers from immigrant diversity in cities. Journal of Economic Geography, 18(1), 213–245. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbx012

- Kerr, W. R. (2013). US high-skilled immigration, innovation, and entrepreneurship: Empirical approaches and evidence.

- Knight, G. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2004). Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 124–141. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400071

- Laursen, K. (2012). Keep searching and you’ll find: What do we know about variety creation through firms’ search activities for innovation? Industrial and Corporate Change, 21(5), 1181–1220. doi: 10.1093/icc/dts025

- Laursen, K., & Salter, A. (2006). Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Journal, 27(2), 131–150. doi: 10.1002/smj.507

- Lee, N., & Nathan, M. (2010). Knowledge workers, cultural diversity and innovation: Evidence from London. International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development, 1(1–2), 53–78. doi: 10.1504/IJKBD.2010.032586

- Lööf, H., & Heshmati, A. (2002). Knowledge capital and performance heterogeneity:: A firm-level innovation study. International Journal of Production Economics, 76(1), 61–85. doi: 10.1016/S0925-5273(01)00147-5

- Martin, R., Aslesen, H. W., Grillitsch, M., & Herstad, S. J. (2018). Regional innovation systems and global flows of knowledge. In New avenues for regional innovation systems-theoretical advances, empirical cases and policy lessons (pp. 127–147). Berlin: Springer.

- Morrison, A. (2008). Gatekeepers of knowledge within industrial districts: Who they Are, How they interact. Regional Studies, 42(6), 817–835. doi: 10.1080/00343400701654178

- Mudambi, R., Li, L., Ma, X., Makino, S., Qian, G., & Boschma, R. (2018). Zoom in, zoom out: Geographic scale and multinational activity. Journal of International Business Studies. Advance online publication.

- Nathan, M., & Lee, N. (2013). Cultural diversity, innovation, and entrepreneurship: Firm-level evidence from London. Economic Geography, 89(4), 367–394. doi: 10.1111/ecge.12016

- Oettl, A., & Agrawal, A. (2008). International labor mobility and knowledge flow externalities. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(8), 1242–1260. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400358

- Østergaard, C. R., Timmermans, B., & Kristinsson, K. (2011). Does a different view create something new? The effect of employee diversity on innovation. Research Policy, 40(3), 500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2010.11.004

- Ozgen, C., Nijkamp, P., & Poot, J. (2013). The impact of cultural diversity on firm innovation: Evidence from Dutch micro-data. IZA Journal of Migration, 2(1), 18. doi: 10.1186/2193-9039-2-18

- Parrilli, M. D., Nadvi, K., & Yeung, H. W.-C. (2013). Local and regional development in global value chains, production networks and innovation networks: A comparative review and the challenges for future research. European Planning Studies, 21(7), 967–988. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.733849

- Parrotta, P., Pozzoli, D., & Pytlikova, M.. (2014). The nexus between labor diversity and firm’s innovation. Journal of Population Economics, 27(2), 303–364. doi: 10.1007/s00148-013-0491-7

- Pelled, L. H. (1996). Demographic diversity, conflict, and work group outcomes: An intervening process theory. Organization Science, 7(6), 615–631. doi: 10.1287/orsc.7.6.615

- Plechero, M., & Chaminade, C. (2016). Spatial distribution of innovation networks, technological competencies and degree of novelty in emerging economy firms. European Planning Studies, 24(6), 1–23. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1151481

- Plum, O., & Hassink, R. (2013). Analysing the knowledge base configuration that drives southwest saxony’s automotive firms. European Urban and Regional Studies, 20(2), 206–226. doi: 10.1177/0969776412454127

- Ruef, M., Aldrich, H. E., & Carter, N. M. (2003). The structure of founding teams: Homophily, strong ties, and isolation among US entrepreneurs. American Sociological Review, 68, 195–222. doi: 10.2307/1519766

- Saxenian, A., & Sabel, C. (2008). Roepke lecture in economic geography venture capital in the “periphery”: The New argonauts, global search, and local institution building. Economic Geography, 84(4), 379–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2008.00001.x

- Scellato, G., Franzoni, C., & Stephan, P. (2015). Migrant scientists and international networks. Research Policy, 44(1), 108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2014.07.014

- Shakirov, A. R. (2017). The links between global value chains and global innovation networks. Vestnik Mezhdunarodnykh Organizatsii-International Organisations Research Journal, 12(4), 236–241.

- Shore, L. M., Chung-Herrera, B. G., Dean, M. A., Ehrhart, K. H., Jung, D. I., Randel, A. E., & Singh, G. (2009). Diversity in organizations: Where are we now and where are we going? Human Resource Management Review, 19(2), 117–133. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.10.004

- Silva, P. C., & Klagge, B. (2013). The evolution of the wind industry and the rise of Chinese firms: From industrial policies to global innovation networks. European Planning Studies, 21(9), 1341–1356. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.756203

- Simonen, J., & McCann, P. (2008). Firm innovation: The influence of R&D cooperation and the geography of human capital inputs. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(1), 146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2007.10.002

- Solheim, M. C., & Fitjar, R. D. (2018). Foreign workers are associated with innovation, but why? International networks as a mechanism. International Regional Science Review, 41(3), 311–334. doi: 10.1177/0160017615626217

- Statistical Office of Sweden. (1998). SSYK 96 standard för svensk yrkesklassificering 1996 [Standard for Swedish classification of occupations]. MIS Meddelanden i samordningsfrågor för Sveriges officiella statistik [Reports on statistical coordination for the official statistics of Sweden] 1998/3.

- Teece, D. J., & Pisano, G. P. (1997). The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3(3), 537–556.

- Tödtling, F., Grillitsch, M., & Höglinger, C. (2012). Knowledge sourcing and innovation in Austrian ICT companies—How does geography matter? Industry and Innovation, 19(4), 327–348. doi: 10.1080/13662716.2012.694678

- Trippl, M. (2013). Scientific mobility and knowledge transfer at the interregional and intraregional level. Regional Studies, 47(10), 1653–1667. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2010.549119

- Trippl, M., Grillitsch, M., & Isaksen, A. (2017). Exogenous sources of regional industrial change: Attraction and absorption of non-local knowledge for new path development. Progress in Human Geography, 0309132517700982. Advance online publication.

- Visser, E. J., & Boschma, R. (2004). Learning in districts: Novelty and lock-in in a regional context. European Planning Studies, 12(6), 793–808. doi: 10.1080/0965431042000251864

- Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185–203. doi: 10.5465/amr.2002.6587995