ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the micro-level processes whereby knowledge-intensive entrepreneurs become embedded in networks to access resources, and in doing so help transform a region. Our analysis contributes to theoretical debates about how the entrepreneurs achieve this aim in order to develop their knowledge-intensive entrepreneurial ventures in creative industries. Our conceptualization specifies how entrepreneurs can use embeddedness in networks in order to access specific types of resources, during the pre-entry phase, the establishment phase, and the post-entry phase. The textiles and fashion industry is an interesting setting to explore these topics because of the rapid industrial transformation from mass production of textiles to large e-commerce firms. Our results suggest that pre-history of the individual entrepreneur has long-term effects upon access to unique resources within the industry, enabling this group to more quickly build their entrepreneurial ventures. Our qualitative case study contributes to theoretical discussions of how micro-processes of KIE entrepreneurship can renew regions and traditional industries, because our analysis shows the enduring impact of past industrial, regional and family ties.

1. Introduction

This article is situated in evolutionary economic geography and evolutionary economics more broadly, where emerging literature suggest the need to better understand the relationships between knowledge, entrepreneurship and regional transformation (Henning & McKelvey, Citation2018). Evolutionary economic geography is an important stream of literature for understanding regional transformation over time (Boschma & Martin, Citation2010). Our first starting-point is that actors, networks and resources tend to concentrate into regions, and that this concentration, in turn, drives regional specialization and entrepreneurial activity into certain technologies and industries (Boschma & Martin, Citation2010; Feldman, Citation2001). Within this literature, a wide variety of studies focus upon processes leading to technological and industrial change, by proposing concepts such as regional innovation systems, relatedness, smart specialization, resilience and entrepreneurial ecosystems (Boschma, Citation2015; Simmie & Martin, Citation2010). Our second starting-point arises from the insight from an evolutionary approach more generally, that micro-level processes can explain complex macro processes of technological and industrial change in an institutional context, as related to knowledge. The economic geography studies share commonality with evolutionary economics more broadly, in identifying and analyzing actors, mechanisms and outcomes, and in proposing that regional transformation over time involves both path-dependency as well as multiple sets of possible alternative trajectories and outcomes. Evolutionary economics more generally has proposed the important role of information and knowledge, in stimulating processes of creative destruction and renewal in the economy (Antonelli, Citation2008; Metcalfe, Citation1998). Currently, we know much less about how these broader processes relate to the specific processes whereby entrepreneurs embed in regional networks, and how such embeddedness in turn impacts their knowledge-intensive entrepreneurial (KIE) firms. Hence, this article analyzes the micro-level processes of KIE firms becoming embedded in their context, using an evolutionary approach.

More specifically, our focus is upon knowledge-intensive entrepreneurs in creative industries, in relation to the process of becoming embedded in regional and industrial networks. The emerging literature on knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship builds upon Schumpeterian economics, evolutionary economics and innovation systems (Malerba & McKelvey, Citation2018a). This literature provides a conceptualization of how and why knowledge and innovation are vital in creating strategic capabilities in this type of firms, and therefore helps explain why network relationships that are vital in the evolution from an individual entrepreneur (e.g. person and founder team) through the starting up and managing of an entrepreneurial venture (e.g. organization) (Malerba, Caloghirou, McKelvey, & Radoševic, Citation2016; McKelvey & Lassen, Citation2013). For the current article, this type of KIE entrepreneurship is a relevant situated context to study the process of becoming embedded, because previous research indicates that KIE firms are highly dependent upon knowledge network and innovation system relationships in order to access resources to start their company, identify opportunities and also result in business performance (Malerba & McKelvey, Citation2018a). We further extend current literature by studying when these entrepreneurs become embedded in regional networks, and especially focusing on how the individual entrepreneur accesses resources and later develop capabilities within the KIE firm.

In extending this literature, we draw upon existing entrepreneurship and network literature, which propose that studying entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship involves not only markets but also networks and institutions (Carlsson et al., Citation2013). As entrepreneurs gain access to social networks, they accrue social capital, which may increase their chance to obtain resources through network conduits (Uzzi, Citation1997). We particular draw from research which explains how individual entrepreneurs access networks within their region (Jack & Anderson, Citation2002; Mai & Zheng, Citation2013) as well as studies that explain how policy can facilitate the creation of social capital for less embedded entrepreneurs (Cooke, Citation2007). We do so in order to provide a more fine-grained analysis of what it means for these KIE firms to become embedded in networks.

This article has three aims, reflecting the subsequent sections. First, we provide conceptualization of possible factors which affect the process of becoming embedded, which may determine which resources are channelled to the new KIE venture. Section 2 explains how foundations from existing theory are further developed, leading to our conceptualization of this process. Secondly, this conceptualization is applied to our research strategy. We conduct a qualitative study over several years, of a full population of emerging KIE entrepreneurs, active in a specific industry and in a geographically delimited region. Therefore, section 3 discusses research design and methodology, while section 4 presents our results. Third, we interpret the results of our qualitative case study in relation to our conceptualization, in order to develop propositions and suggestions for future research. Hence, section 5 discusses and interprets our findings, in terms of propositions and future research.

2. Linking KIE entrepreneurship with embeddedness using an evolutionary economics approach

Our contribution is te focus upon the micro-level processes of KIE entrepreneurs becoming embedded, within a defined industry and region in the creative industries. We acknowledge that entrepreneurship can be analysed at many different levels, from the individual entrepreneur to the venture to the phenomena and the impacts on the economy and the society (Carlsson et al., Citation2013). Our approach, laid out above, is that we will study the entrepreneur in relation to their access to resources through networks and their development of capabilities in the KIE firm, and that our focus is knowledge-intensive entrepreneurs because they are highly dependent upon new knowledge as the basis for competition and upon network relationships (Malerba & McKelvey, Citation2018b). We will therefore analyse micro-level processes. We do so, in order to analyze why becoming embedded in the network is useful to the entrepreneur, by developing and synthesizing three views from existing literature into a novel conceptualization.

Firstly, to further enrich our study of the micro-level processes of KIE entrepreneurship, we draw upon theories that help explain the importance of embeddedness and social capital in networks more generally to apply to this purpose. We use social capital and social network theory to examine how networks affect the entrepreneur's access to resources, which in turn affect the firm's capabilities and performance (Granovetter, Citation1985; Powell, Koput, & Smith-Doerr, Citation1996; Uzzi, Citation1999). This literature suggests that partners engage in collaboration, accept risk and trust partners to different degrees. Going further, based on the knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship concept, we aim to further investigate and develop the underlying assumption that networks such as innovation systems are used to access core resources and capabilities of a firm, by bringing in theories of the firm. We define resources as the stock of productive factors controlled by a firm, as defined by Amit and Schoemaker (Citation1993). We define capabilities of entrepreneurial ventures as the capacity to use these resources to reach a desired outcome (Barney, Citation1991; Mahoney & Pandian, Citation1992). We further divide resources and capabilities into the sub-categories of financial, physical, human and social, and organizational resources and capabilities, recognizing that they may be tangible or intangible (Barney, Citation1991). Resources and capabilities are concepts used within theories of the firm, including ones inspired by Schumpeterian and evolutionary economics more broadly. Related theoretical and empirical research has found that access to existing resources and the development of capabilities in the creation of new entrepreneurial ventures as well as creation of new opportunities together impact their relative success or failure (Giarratana & Fosfuri, Citation2007; Zaring & Eriksson, Citation2009). Specifically, our interest is in how KIE firms acquire and use unique resources in order to perform in the market, applying ideas from theory of the firm to this context.

Secondly, to more specifically examine the relationship to the local context, we consider the role and characteristics of entrepreneurial networks in regions and industries. Generally, in the entrepreneurship literature, networks are widely recognized to play a central role in the successful emergence and growth of entrepreneurial firms (Hite & Hesterly, Citation2001). Being able to use networks to access resources and capabilities is of major importance for entrepreneurial ventures (Strobl, Citation2014). Our interpretation of this literature is that having certain positions in a network opens up opportunities the firm and also enables them to access resources. Our reasoning is based on previous literature that shows that entrepreneurs rely on various network types, such as social networks, reputational networks, competition networks, marketing networks, as well as knowledge, innovation and technology networks (Burt, Citation2001; Coleman, Citation1988; Lechner, Dowling, & Welpe, Citation2006). More specifically linked to the propositions of evolutionary economic geography, we draw from research that suggests that individuals may be relationally and economically embedded in a specific location. This type of embeddedness is ‘in the form of localized network externalities that are intangible assets with a limited transferability over space’ (Martynovich, Citation2017, p. 743). Previous research in this vein have found that entrepreneurs that perform in their home regions tend to show a higher rate of survival than those relocating to other regions (Dahl & Sorenson, Citation2009). Several reasons for this variation have been found, e.g. access information and financial resources at an early stage (Martynovich, Citation2017; Nijkamp, Citation2003); develop the ability to identify and reach potential collaborative partner such as customers, suppliers, advisors, employees and investors and facilitate the exchange and quality of local knowledge (Martynovich, Citation2017; Michelacci & Silva, Citation2007; Zander, Citation2004) Klepper (Citation2001, p. 659). showed that specific industry experience of the entrepreneur is particularly important in explaining the performance of their start-ups ventures in the same industry Baptista, Karaoz, and Mendonca (Citation2014, p. 845). state that ‘pre-entry knowledge associated with general and specific human capital helps discover and evaluate opportunities, set up the business, and endure the critical first years after founding, possibly by facilitating more cumulative learning about the market’ Mai and Zheng (Citation2013, p. 519). argue that employees are more likely to start new ventures in the industry in which they worked before, due to their high level of embeddedness that enables them to access key resources and also have a positive impact on the growth of the venture. Hence, we adhere to the notion that the process of building networks to obtain resources and capabilities for entrepreneurial ventures is highly geographically bounded (Audretsch, Falck, Feldman, & Heblich, Citation2012).

Thirdly, we use existing literature to motive our choice to examine different phases of entrepreneurship, due to differing linkages between the entrepreneur (e.g. person or founder team) and the entrepreneurial venture over time. Embeddedness occurs when a particular type of business network is developed that helps the company to access resources (Halinen & Törnroos, Citation1998) Helfat and Lieberman (Citation2002, p. 725). argues that ‘before ways of doing can persist, they must be born’ to suggest the importance of studying what happens before the entrepreneurial venture is started. Their argument is that the experience of the entrepreneur before starting the company will impact the relationship between market entry capabilities and organizational resources, cf. also (Hansen, Citation1995). In an early start-up phase the entrepreneur may encounter problems related to resource access, reaching customers as well as developing the business process and marketing people (such as capable personnel and reliable suppliers), and market assessments, external relations (advisors and financers), and the positioning and sales (Strobl & Kronenberg, Citation2016). Still, characteristics of the founder can continue to impact the venture over time, because networks can provide access to resources (Licht & Siegel, Citation2006). McKelvey and Lassen (Citation2013) and Lassen, McKelvey, and Ljungberg (Citation2018) propose differentiate three phases of KIE entrepreneurship, namely ‘Accessing resources and ideas’, ‘Developing and managing the venture’ and ‘Evaluating performance and output’. We follow phases in relation to market entry, following (Helfat & Lieberman, Citation2002). Our interpretation is therefore that it is useful to distinguish three phases, which we here define as pre-entry, entry, and post-entry, all considered in relation to entry to the market.

Our conceptualization builds upon the above streams of literature, and our interpretation of how these processes will play out are that:

Becoming embedded in a network will impact the evolution of the KIE firm, due to the entrepreneur's access to resources and the KIE firm's transformation of resources and organizational configuration into capabilities. To further understand the process of becoming embedded, we have divided our analysis of the resources obtained through networks into a series of fine-grained categories

Becoming embeddedness is important, due to the logic of exchange that promotes improvements in economic efficiency of entrepreneurial ventures. We suggest that economic efficiency can depend upon innovation system aspects, specifically the qualities of the regional social capital, how same-industry knowledge is acquired, and the specific developmental phase of the KIE venture.

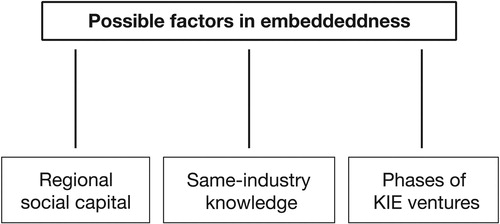

Therefore, we propose that three factors matter in the process in embeddeddness of a KIE venture, and they matter because they likely determine which resources may be channelled to a new venture, during different phases. This conceptualization is visualized in .

Our interpretation of the theoretical logic underlying can be summarized as follows. The process of embedding of a new KIE venture in a commercial context represents an opportunity to acquire unique combinations of resources as well as develop firm-level conversion mechanisms for capability development. In the long run, the specific industrial and regional context of embeddedness means that knowledge and entrepreneurship affect regional transformation in particular directions. Moreover, we are interested in how the KIE entrepreneurs start (are endowed) with firm-specific resources and capabilities, but that over time, they acquire new resources and capabilities, during the process of becoming embedded in a specific regional and industrial context.

3. Empirical setting and research design

3.1. From textiles to fashion in Borås Sweden

The empirical setting for our qualitative case study of the phenomena of knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship is the Swedish textile and fashion industry, specifically in the European region of Borås, Sweden. Like much of Europe, this industry in Borås is characterized by long-term regional and industrial dynamics, including recent upheavals due to internationalization, and the case is suitable for our study. Olsson, Berglund, Caldenby, and Johansson (Citation2005) point out that the larger area, Sjuhäradsbygden, was granted special rights of trade as far back as 1621. Textile manufacturing became a major industry there in the nineteenth century, first specializing in wool spun into yarn and clothing, and later linen and cotton used for thread, material and clothes. In the twentieth century, Sjuhäradsbygden and the city expanded rapidly. However, the Swedish textile industry collapsed in the 1970s, and employment in this industry in the region decreased from 1,13,000 employees in 1950, to less than 30,000 by the mid-1980s (Larsson et al., Citation2014, p. 512). Although the textile industry disappeared completely in many regions in Sweden and in Europe, Borås has at least been partially successful in this regional transformation. Borås is currently the leading Scandinavian centre for large distribution companies, whose headquarters and logistics are located there, while manufacturing is located abroad. Even if Stockholm is much more prominent in fashion, Borås has activities, and especially KIE entrepreneurial ventures in textiles and fashion.

3.2. Research design: enriching theory through a single case study

Our in-depth empirical investigation is into the phenomenon of how entrepreneurs become embedded in networks, during the evolution of KIE firms in a specific region and industry. Therefore, we designed our case study to capture this phenomenon, from the perspective of these entrepreneurs, and to use our analysis to develop theoretical propositions. We follow Eisenhardt (Citation1989) and Bansal and Corley (Citation2012, p. 510), in designing a specific workflow for going back and forth between theory and empirics. This includes developing theoretical concepts, coding for the qualitative analysis, and specifying new theoretical understanding by generating propositions. This article is based on a single case study design (Stake, Citation1995), covering the full population of relevance, which we have identified as 12 KIE firms matching our criteria for selection.

Five criteria for selection were used to find this population of KIE entrepreneurs. The first two criteria were used to specify the industry and region – specifically, manufacturing and design in textiles in the region of Borås (Sjuhäradsbygden). We made an initial analysis of all active companies there, based upon industry statistics, where Statistics Sweden (SCB, Citation2014) confirmed that there were 64 companies within the textile industry in Borås in 2014 Portnoff (Citation2013, p. 16). provides a rationale for this segment of the textile industry. In order to focus upon entrepreneurs who have started small KIE companies, the next three criteria for selection were used: only entrepreneurs who had incorporated a company; a maximum age of company (10 years), a maximum size (<10 employees), and where fashion represents the key type of knowledge used as a competitive asset. Taken together, these three criteria for selection correspond to the definition of knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship (Malerba & McKelvey, Citation2018a; McKelvey & Lassen, Citation2013).

Thus, we study all entrepreneurs and their KIE firms, which together constitute the total population matching all five criteria for selection. The population consists of twelve KIE firms, as described in .

Table 1. An overview of the twelve KIE entrepreneurial ventures and characteristics of founders.

Even though all the KIE firms are young (<10 years), and very small (<10 employees), they have been formally constituted as companies and managed to sell their good or product. As shown in , nine entrepreneurs were from the region, and three were not; seven had work experiences in textiles and fashion and five did not. Moreover, provides an indication of their specific niche within the textile and fashion industry and basic information.

Our case study has been chosen to explore the phenomenon of how entrepreneurs become embedded in networks, during the evolution of knowledge-intensive entrepreneurial ventures. Thus, we can use our case study to analyze variation across the areas of interest, in relation to the phenomenon and our proposed conceptualization above. First, we examine the resources obtained through networks through fine-grained categories; second, we examine their relational and economic embeddedness in the region; third, we examine their work and educational experience; and finally, we examine this micro-level process through three phases. e.g. pre-entry, entry and post-entry.

We recognize the limitations of our single case study design, limited to one in-depth empirical investigation over time. The case study covers the full regional population of single industry KIE entrepreneurs. A specific empirical characteristic may be the collaborative nature of relationships, confirming Malmberg, Power, and Hauge (Citation2009), but limiting generalizability.

3.3. Data collection and data analysis

For the population chosen, we have listed each entrepreneur (or founder team) and also identify each company as described above. Following this initial list, our next step was to collect archival material, such as annual reports, newspaper articles and official statistics, in order to create a background understanding for each of the firms. Short write-ups were completed to provide depth of understanding. Interviews were then carried out, according to a semi-structured interview guide, developed jointly by all authors, and intended to focus the discussion upon the variables and processes specified above. In addition, the interviewer asked follow-up questions to elicit clarification, more in-depth understanding and illustrations. Twenty-three interviews were conducted in Spring 2014 and Spring 2015, by one author. All were recorded as well as immediate field notes. Each interview lasted on average 45 min and were subsequently transcribed (in Swedish). The initial round in 2014 covered all entrepreneurs active in the 12 companies studied. Note that 13 interviews were conducted, because one company had two founders. Twenty-two interviews were conducted face-to-face, and one by phone. In 2015, follow-up interviews were conducted with the eight entrepreneurs who responded to our request. The authors have translated quotes used in this article to English.

Uzzi (Citation1996) states that the purpose of a qualitative study is to identify underlying patterns. The patterns that occur can be categorized as variables that summarize, describe and explain the data that have been collected.

Hence, we have categorized and coded the empirical material in the form of interview transcripts, other documents obtained during the data collection process and field notes from site visits. In this way, each interview was individually analyzed, yielding the process history of each entrepreneur's embedding in a textile and fashion industry, as grounded in theory and in chronological order of start-up. One author did the initial coding, and then all three authors reviewed the coding to improve validity, and reliability, as well as removing errors due to interrater subjectivity.

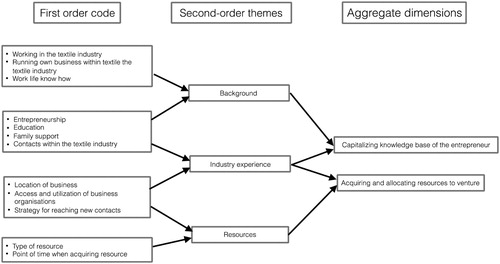

To further explain, our coding strategy visualized in follows the procedure employed by Ailon-Souday and Kunda to ‘make sense’ of our data in a three-step procedure of analysis. The first one involves coding and categorization (Ailon-Souday & Kunda, Citation2003; Strauss, Citation1987). Here, our descriptive, first order codes, e.g. those of age, gender, education, industry background, and points in time when resources where acquired were assigned in transcripts and documents. In the next round of coding, we used theoretically grounded second-order themes from our conceptualization as together with our concurrent analysis of the empirical material, as described above, and we assigned the first order coded qualitative data to each of the themes. The themes describe theoretical categories for ‘background’, ‘industry experience’, and the characteristics of ‘resource’ acquisition, such as the stage of development and connection to a place. Each code and theme were assigned a colour applied to specific parts of our transcripts and documents. The next step was to arrange the coded transcripts and documents chronologically. The final step was to re-read the material and identify aggregate dimensions that would explain our phenomenon of interest. At this step, existing and some new literature were perused to verify the validity of these discoveries or identify other interpretations. This largely descriptive material was then further analyzed to develop analytical abstractions in order to extract patterns and underlying mechanisms that might explain how entrepreneurs embed (Charmaz, Citation2006). The coded interviews were used to extract quotes in and interpretations of our results in Section 4.

Table 2. Quotes about existing resources, nature of embedding, and resources acquired during the pre-entry phase.

Table 3. Quotes about resources acquired during the establishment phase.

Table 4. Quotes about existing resources acquired during the entry phase.

4. Results: KIE entrepreneurs becoming embedded in the textile industry and region

This section provides the results of our qualitative case study, and specifically the analysis of the KIE entrepreneur and their firm, in relation to three phases of becoming embedded.

4.1. Insights related to our conceptualization

Our analysis of the qualitative case study in relation to the conceptualization of the process of becoming embedded depending upon both the capitalizing on the knowledge base of the KIE entrepreneur, and the later acquiring and allocating resources to the KIE venture. Our two main insights from this analysis can be summarized as 1) the importance of a closed network and 2) the distinction between the experienced and non-experienced entrepreneur.

Our first insight related to our conceptualization is that KIE entrepreneurs preferred to become part of a closed and small network around the region and industry. The reason for preferring – or at least recognizing the value – of a closed network is that this provide values by enabling them to access resources. In particular, the entrepreneurs describe how the social capital resulting from embedding can be enhanced through personal branding, trust and collaboration. These KIE entrepreneurs identified the importance of ‘personal branding’, e.g. what they meant was the branding of the individual entrepreneurs as being trustworthy. Our interpretation is that they have low bargaining power as compared to suppliers, because all of the KIE ventures studied were very small companies, without standardized scale production over time. This scale issue made it difficult to find suppliers to manufacture for their needs. Therefore, branding – usually of the person and occasionally of the venture – made it possible to access resources that would not be available in a market arms-length transaction.

Moreover, our interpretation is that these closed networks were primarily regional in these sense of a geographical region, in that they felt that trust was to actors close by. The entrepreneurs stressed that regional interactions – as compared to national or international ones – were particularly important. They exemplified this through different types of regional collaboration, and, many entrepreneurs referred to investments by national and regional government agencies to stimulate the industry, such as the Textile Fashion Centre and the University of Textiles. Several entrepreneurs mentioned that they might cooperate with students at the University of Borås in the future in order to develop high quality fabrics. In developing these ties, the entrepreneurs also reported that they used a variety of channels of communication – such as fairs, industry associations, and social media – as well as direct personal relationships within the region. In presenting the results below, we therefore pay special attention to the networks underlying regional social capital, including the different types of resources acquired during the three phases of pre-entry, entry, and post-entry to the market.

Our second insight from the analysis in relation to the conceptualization is that the entrepreneurs need to be divided in two separate analytical categories, namely the experienced and the non-experienced KIE entrepreneur. These two categories build upon , and our theoretical themes visualized there. More specifically for this insight, we found that:

Contrasting the categories of experienced and non-experienced KIE entrepreneurs was particularly relevant to our analysis, in relation to their socio-relations and economic embeddedness in a specific location.

Contrasting the categories of experienced and non-experienced KIE entrepreneurs was particularly relevant to our analysis, in relation to their work and educational experience in the same industry.

In presenting the details of the qualitative study below, we use these two analytical categories of experienced and non-experienced KIE entrepreneurs, as they have a strong explanatory power.

4.2. Embedding in the pre-entry phase

Our first results refer to the pre-entry phase, where embedding is dominated by the personal networks of the KIE entrepreneur. Our interpretation follows, focusing upon what we interpret related to existing resources, nature of embedding, and resources acquired.

For the experienced entrepreneurs, they used their previous experience, as a way to access complementary resources and capabilities such as contact with suppliers, producers, marketing, sales and personal contacts. In interviews with the founders, more of them stressed personal branding, by which they meant individual characteristics that helped networking and decision-making. Several stated that personal branding helped them to establish new contacts or re-establish older contacts, especially if they had had previous network relationships through business. As further analyzed in Section 4.4, they referred to legitimacy, bargaining power and reputation. In terms of resources, many of these interviewees stressed the importance of the coming from a family with an entrepreneurial background, which in turn influenced their decisions and helped provide access to resources.

For the non-experienced entrepreneurs, they in contrast stressed that they had to create networks. Their important sources of knowledge were entrepreneurial education and training activities, involving both practical and theoretical knowledge. Moreover, they identified the importance of developing new network relationships in the industry, and in their case, the specific illustrations relate to having a mentor with knowledge of the textile industry or an advisory board as well as the support of family to make contacts. They argued that these types of networks conveyed knowledge that they found crucial about how to run a business (in general), or to learn about the specific industry. Finally, in terms of resources, a key aspect they mentioned was how the network facilitated accessing resources related to financing.

is structured so that three aspects from our conceptualization about embedding are in the first column, while the second and third column provide relevant quotes from experienced and non-experienced entrepreneurs, in relation to the three aspects of existing resources, nature of embedding, and resources acquired.

Let us compare and contrast the two groups for the pre-entry phase. In terms of similarities, both utilized their own financial capital as well as public grants for founding the start-up. For both, arms-length transactions through the market were primarily used to obtain non-core capabilities and to develop marketing channels.

For the experienced entrepreneurs, they were active in utilizing their network in this phase, with an aim to use or further develop an existing, mature network within the textile industry and region before the establishment of their company. Moreover, their individual networks depended heavily upon attributes of (individual) social capital in the industry, partly based upon work experience and family experience of entrepreneurship; this social capital also facilitated access to financial capital. Thus, the experienced entrepreneurs stressed the importance of their heritage within an entrepreneurial textile family, which enabled them to know the business culture as well as already having a reputation in the industry, existing before starting the KIE firm. Their personal branding then enabled them to directly access resources from the network during this phase.

For the non-experienced entrepreneurs, they had to rely more on support and help from their family or from industry and regional associations. Moreover, they had educational and other experience of more general entrepreneurial skills, which they found useful. As a way to substitute for the fact that the non-experienced were not already embedded in the industry, they relied upon the contacts of contacts, or ‘second hand’ contacts, in order to acquire knowledge about the textile industry and how to run a business. In these processes, our interpretation is that their social capital was also useful in the search for creating a network (e.g. adding additional contacts), which could help to support the evolution of their KIE firm.

4.3. Effects of embedding during the entry phase

Our second result concerns the entry (establishment) phase, at which time we can analyze separately and in interaction, the networks of both the entrepreneur and the KIE venture.

For the experienced entrepreneurs, they also utilized regional organizations and incubators, but they did so in order to find additional contacts and increase their overall network. The network helped them to find and exchange experiences, to widen the network by making contact with similar companies, and to further develop their artistic expression in fashion. For some, their regional and industrial experience is particularly valuable resource during the establishment phase.

Moreover, we found some differences within the group of experienced entrepreneurs. Some of these founders could draw upon contacts they had already had, while others had to develop new networks for new purposes. For the latter, even though they had same-industry experience, the entrepreneurs had been working within a different niche in the industry and needed network for the new niche in fashion. The reason was that these entrepreneurs identify quite different types of market, business and advanced knowledge as relevant in different market niches in the same industry.

For the non-experienced entrepreneurs, the establishment phase was a time when their previous and current activities to develop a network now enabled them to become more embedded in the regional structure. The regional collaborative structure helped them, and these founders stressed aspects of collaborative support such as the importance of having a concentration of activities in textiles in the region as well as specific organizations designed for collaboration and advice. The value of networks included activities, which they felt might enhance their possibility to become innovators as well as activities to facilitate the creation of additional relationships. Our interpretation is that these entrepreneurs started to become embedded as they entered the market, and regional collaborative activities and organizational structures were very important to them.

In order to further explore the effects of embedding in the entry phase, provides quotes for each group, about the resources they acquire.

Our interpretation is that the two groups are becoming more alike during the entry phase, in that both have become embedded but continue to do so, in slightly different ways as explained above. For them, embedding is characterized by a mix of arms-length relationships related to market transactions as well as socially embedded network ties. A similarity between the two groups is that they could access complementary assets, and they face the task of scaling up, and thereby required additional types and scale of resources. In particular, they stressed the importance of knowledge resources about industry practices, technology and supply channels are acquired by the entrepreneurs and their KIE ventures.

4.4. Effects of embedding during the post-entry phase

Our third result focuses upon the post-entry phase, where embeddedness involves both the networks of the KIE firm and of the individual entrepreneurs, but more time has elapsed.

The experienced entrepreneurs continue to benefit from the entrepreneur's own networks, and benefit from the fact that they already have a personal brand and reputation, and thus have the advantage of being known. These entrepreneurs use their knowledge of this specific regional business culture and textile industry to make decisions, and they did not have to search as much for new contacts, but instead use their old contacts to access resources. After accessing resources and developing organizational capabilities, they then tried to develop them further by ‘re-connecting’ to their original networks. They had access to distribution channels to a larger extent than the non-experienced entrepreneurs.

For the non-experienced entrepreneurs, they must in contrast continue to expend resources to develop their network, also during this latter phase. They report that it is important to be involved in regional activities, and their network provided advantages by making them as individuals and their KIE firm a known brand, which in turn enabled them to further expand their network.

provides quotes about the effects of embedding in the post-entry phase, with a focus on how they impacted the evolution of the company.

In contrasting the two types of KIE entrepreneurs, they seem to use networks for similar reasons, but the entrepreneurs’ previous knowledge and experience continues to impact the evolution of the KIE venture. For the experienced entrepreneurs, our interpretation is that they benefited from being embedded already and could use those existing networks to scale up the venture, instead of having to spend time developing new contacts. The experienced entrepreneur placed more emphasis on re-connecting with their networks, and in defining which were valuable contacts in order to produce, distribute and market their fashion products. For the non-experienced entrepreneurs, they did use the network to develop personal branding and company branding and thereby obtain resources, but in contrast they were still required to expend resources to continue to becoming further embedded. They stress the need to develop a larger network in order to facilitate access to new resources, such as illustrated by hiring employees with work and regional experience. Moreover, these founders report that engaging in activities like branding or creating and strengthening intangible resources was useful in order to secure sales and productions. They also tried to have intermediaries – or people already in the networks – to facilitate additional contacts.

The experienced entrepreneur uses ‘personal branding’ at the individual level – described as legitimacy and reputation – to be able to access resources held by suppliers, distributors and producers. In contrast, even though the non-experienced entrepreneur works hard to try to develop personal branding over time, the analysis suggests that they and their ventures remained more reliant upon regional collaborative bodies. Moreover, they used these collaborative bodies to solve core issues of their business, as compared to the experienced entrepreneurs, who were more interested in creative inspiration.

5. Three propositions and future research

We started out by suggesting that more research should address how and why knowledge, entrepreneurship and regional transformation are somehow linked to path dependency of the region (Henning & McKelvey, Citation2018). This article has explored the processes of becoming embedded within KIE entrepreneurship, following literature which views this as an evolutionary, path-dependent process linked to an industry and local community (Audretsch & Feldman, Citation1996; Boschma & Martin, Citation2010). So how do these abstract concepts play out in our qualitative case study, more specifically, at the micro-level for a population of KIE ventures in one industry and one region? We below provide three propositions and future reseach areas, based upon our analysis and interpretation of our findings.

First, our insight above that the KIE entrepreneurs prefer a local and closed network should be understood relative to our conceptualization of different possible factors which affect the process of becoming embedded. Our first proposition is that experience of entrepreneurs from traditional industries can still affect the process of renewal in a region, due to the enduring importance of existing resources of the entrepreneur or venture; due to the nature of embedding, and due to the resources acquired. Surprisingly, the closed networks also affected their relative ability to develop arms-length transactions through markets, such as find suppliers and producers of their products. Some results, such as same-industry knowledge, is in line with existing literature that entrepreneurs’ previous work experience matters for explaining later performance of the venture (Agarwal, Buenstorf, Cohen, & Malerba, Citation2015; Klepper, Citation2001) or more generally that KIE firms are especially dependent upon network relationships and innovation systems as compared to other ventures (Malerba & McKelvey, Citation2018a). An interesting topic for future research is to study KIE entrepreneurship in different industries, and especially the comparison with creative industries. Some existing literature suggests that creative industries are very different from manufacturing and may transform regions (Bayliss, Citation2007; De-Miguel-Molina, Hervas-Oliver, Boix, & De-Miguel-Molina, Citation2012; Turok, Citation2003), whereas Lassen et al. (Citation2018) find some differences but also many similarities. We do not know if the insight about local and closed networks is a feature of the creative industries or more generally valid. Future research should further explore the process of KIE entrepreneurs and firms becoming embedded in different industries, and especially address them in the creative industries.

Secondly our insight above about experienced and non-experienced can help to further develop the KIE literature, in order to specifically understand processes of resources and capabilities building (Barney, Citation1991; Mahoney & Pandian, Citation1992) for different types of entrepreneurs. Our second proposition is that our two aggregate dimensions of capitalizing on knowledge and acquiring and allocating resources will depend upon the specific networks of the entrepreneurs, which in turn will also affect the evolution of the KIE venture. We have a clear finding that networks – and associated regional social capital – are of enduring importance for the KIE entrepreneurs and their ventures. Note that instead of defining the full network based upon co-membership (Jack & Anderson, Citation2002; Uzzi, Citation1996), our findings suggest that individual KIE entrepreneurs has different access, and use of the same network, in ways which affect the firm. One reason is that previous experience helps the entrepreneur develop networks (Jack & Anderson, Citation2002), and hence our approach finds a way to specifically study networks as well as the types of resources accessed through them. Moreover, not only does social capital in terms of trust helps the development of the network (Helfat & Lieberman, Citation2002, p. 732), but moreover, we have identified the importance of personal branding and formal collaboration in the networks. In particular, the personal branding of the entrepreneur can help them access arms-length transactions such as access to production and distribution, as well as other types of resources like ‘like-minded people’ or financing, within the fairly closed network. Although both experienced and non-experienced entrepreneurs could build networks, the non-experienced entrepreneurs had to expend more time and effort to access the network and associated resources, over all phases. Future research should investigate and validate whether being connected to geographically bounded networks gives the experienced entrepreneur easier access to valuable resources and thereby increases the chances of survival, through large-scale quantitative research.

Thirdly, in relation to the three phases of KIE ventures, our analysis has demonstrated that embedding has a sequential nature referring to the specific phases of the KIE venture, as in entrepreneurship more generally (Carlsson et al., Citation2013). Our third proposition is that also during different phases, the two categoriess of KIE entrepreneurs have different access, and ability to build, regional knowledge networks, in order to access resources and capabilities. We have shown that during the pre-entry phase, embedding should be differentiated from a parallel process of venture creation. More specifically, we have been able to show that experienced entrepreneurs who are already embedded locally gain access to specific and difficult-to-obtain current know-how and resources valuable specifically for this industry. Conversely, the non-experienced entrepreneurs have to pay a penalty in terms of time and cost to obtain similar market-specific resources and capabilities, which they do by developing a network or other mechanisms. However, by the third phase of post-entry, the non-experienced entrepreneurs have also become part of networks, which suggests that the initial advantages of the experienced entrepreneurs were slowly fading. Thus, our fine-grained analysis indicates that there is an important distinction between the acquisition of more general entrepreneurial capabilities (such as management skills and financial resources) as contrasted to the acquisition of very specific resources and knowledge relevant to their industry, region and product. Consequently, this can help interpret previous research, suggesting that the region has specific knowledge networks, which impact regional resilience to change (Henning & Nedelkoska, Citation2014). Therefore, future research could employ existing concepts like technological distance, as well as cognitive and organizational proximity, to see if they provide additional explanatory power about the differences between experienced and non-experienced entrepreneurs.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the ‘Social and Cultural Entrepreneurship’ Workshop at Institute of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Department of Economy and Society, University of Gothenburg on November 12, 2015 and at the DRUID Academy Conference 2015 at Aalborg, Denmark, January 21 to 23, 2015.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Ida Hermanson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5861-0835

Maureen McKelvey http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1457-7922

Olof Zaring http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0928-9376

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agarwal, R., Buenstorf, G., Cohen, W. M., & Malerba, F. (2015). The legacy of Steven Klepper: Industry evolution, entrepreneurship, and geography. Industrial and Corporate Change, 24(4), 739–753. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtv030

- Ailon-Souday, G., & Kunda, G. (2003). The local selves of global workers: The social construction of national identity in the face of organizational globalization. Organization Studies, 24(7), 1073–1096. doi: 10.1177/01708406030247004

- Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33–46. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250140105

- Antonelli, C. (2008). Pecuniary knowledge externalities: The convergence of directed technological change and the emergence of innovation systems. Industrial and Corporate Change, 17(5), 1049–1070. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtn029

- Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M. P. (1996). Innovative clusters and the industry life cycle. Review of Industrial Organization, 11(2), 253–273. doi: 10.1007/BF00157670

- Audretsch, F. O., Falck, O., Feldman, M. P., & Heblich, S. (2012). Local entrepreneurship in context. Regional Studies, 46(3), 379–389. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2010.490209

- Bansal, P., & Corley, K. (2012). Publishing in AMJ —part 7: What’s different about qualitative research? Academy of Management Journal, 55(3), 509–513. doi: 10.5465/amj.2012.4003

- Baptista, R., Karaoz, M., & Mendonca, J. (2014). The impact of human capital on the early success of necessity versus opportunity-based entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 831–847. doi: 10.1007/s11187-013-9502-z

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. doi: 10.1177/014920639101700108

- Bayliss, D. (2007). The rise of the creative city: Culture and creativity in Copenhagen. European Planning Studies, 15(7), 889–903. doi: 10.1080/09654310701356183

- Boschma, R. (2015). Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Regional Studies, 49(5), 733–751. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.959481

- Boschma, R., & Martin, R. (2010). The handbook of evolutionary economic geography. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Burt, R. S. (2001). Structural holes versus network closure as social capital. In N. Lin, K. S. Cook, & R. S. Burt (Eds.), Social capital: Theory and research (pp. 31–56). New York: Aldine Transaction.

- Carlsson, B., Braunerhjelm, P., McKelvey, M., Olofsson, C., Persson, L., & Ylinenpaa, H. (2013). The evolving domain of entrepreneurship research. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 913–930. doi: 10.1007/s11187-013-9503-y

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE.

- Coleman, J. (1988). Social capital and the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. doi: 10.1086/228943

- Cooke, P. (2007). Social capital, embeddedness, and market interactions: An analysis of firm performance in UK regions. Review of Social Economy, 65(1), 79–106. doi: 10.1080/00346760601132170

- Dahl, M. S., & Sorenson, O. (2009). The embedded entrepreneur. European Management Review, 6(3), 172–181. doi: 10.1057/emr.2009.14

- De-Miguel-Molina, B., Hervas-Oliver, J. L., Boix, R., & De-Miguel-Molina, M. (2012). The importance of creative industry agglomerations in explaining the wealth of European regions. European Planning Studies, 20(8), 1263–1280. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.680579

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case-study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. doi:10.2307/258557 doi: 10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

- Feldman, M. P. (2001). The entrepreneurial event revisited: Firm formation in a regional context. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(4), 861–891. doi: 10.1093/icc/10.4.861

- Giarratana, M. S., & Fosfuri, A. (2007). Product strategies and survival in Schumpeterian environments: Evidence from the US security software industry. Organization Studies, 28(6), 909–929. doi: 10.1177/0170840607075267

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure. The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. doi: 10.1086/228311

- Halinen, A., & Törnroos, J-Å. (1998). The role of embeddedness in the evolution of business networks. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 14(3), 187–205. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5221(98)80009-2

- Hansen, E. L. (1995). Entrepreneurial networks and new organization growth. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 19(4), 7–19. doi: 10.1177/104225879501900402

- Helfat, C. E., & Lieberman, M. B. (2002). The birth of capabilities: Market entry and the importance of pre-history. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(4), 725–760. doi: 10.1093/icc/11.4.725

- Henning, M., & McKelvey, M. (2018). Knowledge, entrepreneurship and regional transformation: Contributing to the Schumpeterian and evolutionary perspective on the relationships between them. Small Business Economics, 1–7.

- Henning, M., & Nedelkoska, L. (2014). Branschöverskridande kompetensknippen. Nya perspektiv på Västsveriges näringslivsstruktur (Report No. n.d.) Västra Götalandsregionen and Västra Region Halland Retrieved from Västra Götalandsregionens https://alfresco.vgregion.se/alfresco/service/vgr/storage/node/content/workspace/SpacesStore/840065f2-57fe-4f90-8443-d268d4335872/Relatedness_VC3A4stsverige.pdf?a=false&guest=true

- Hite, J. M., & Hesterly, W. S. (2001). The evolution of firm networks: From emergence to early growth of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 22(3), 275–286. doi: 10.1002/smj.156

- Jack, S. L., & Anderson, A. R. (2002). The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(5), 467–487. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00076-3

- Klepper, S. (2001). Employee startups in high-tech industries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(3), 639–674. doi: 10.1093/icc/10.3.639

- Larsson, M., Andersson-Skog, L., Broberg, O., Magnusson, L., Petersson, T., & Sandberg, P. (2014). Det svenska näringslivets historia 1864–2014. Stockholm: Dialogos Förlag.

- Lassen, A. H., McKelvey, M., & Ljungberg, D. (2018). Knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship in manufacturing and creative industries: Same, same, but different. Creativity and Innovation Management, 27(3), 284–294. doi: 10.1111/caim.12292

- Lechner, C., Dowling, M., & Welpe, I. (2006). Firm networks and firm development: The role of the relational mix. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(4), 514–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.02.004

- Licht, A. N., & Siegel, J. I. (2006). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In M. Casson, & B. Yeung (Eds.), Oxford handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 511–539). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mahoney, J. T., & Pandian, J. R. (1992). The resource-based view within the conversation of strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 13(5), 363–380. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250130505

- Mai, Y. Y., & Zheng, Y. F. (2013). How on-the-job embeddedness influences new venture creation and growth. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(4), 508–524. doi: 10.1111/jsbm.12000

- Malerba, F., Caloghirou, Y., McKelvey, M., & Radoševic, S. (2016). Dynamics of knowledge intensive entrepreneurship: Business strategy and public policy, Vol. 38. Routledge.

- Malerba, F., & McKelvey, M. (2018a). Knowledge intensive entrepreneurship: Integrating Schumpeter, evolutionary economics and innovation systems. Small Business Economics. doi: 10.1007/s11187-018-0060-2

- Malerba, F., & McKelvey, M. (2018b). Knowledge intensive entrepreneurship and future research directions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Malmberg, A., Power, D., & Hauge, A. (2009). The spaces and places of Swedish fashion. European Planning Studies, 17(4), 529–547. doi: 10.1080/09654310802682073

- Martynovich, M. (2017). The role of local embeddedness and non-local knowledge in entrepreneurial activity. Small Business Economics, 49(4), 741–762. doi: 10.1007/s11187-017-9871-9

- McKelvey, M., & Lassen, A. H. (2013). Knowledge intensive entrepreneurship: Engaging, learning and evaluating venture creation. Cheltenhem, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Metcalfe, J. S. (1998). Evolutionary economics and creative destruction. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Michelacci, C., & Silva, O. (2007). Why so many local entrepreneurs? Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(4), 615–633. doi: 10.1162/rest.89.4.615

- Nijkamp, P. (2003). Entrepreneurship in a modern network economy. Regional Studies, 37(4), 395–405. doi: 10.1080/0034340032000074424

- Olsson, K., Berglund, B., Caldenby, C., & Johansson, L. (2005). Borås stads historia II. Industrins och industrisamhällets framväxt 1860–1920. Lund: Historiska Media.

- Portnoff, L. (2013). Modebranschen i Sverige: statistik & analys (Report no. 13:03) Retrieved from Volante Research http://volanteresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/1303-Modebranschen-i-Sverige-2013_web.pdf

- Powell, W. W., Koput, K. W., & Smith-Doerr, L. (1996). Interorganizational collaboration and the locus of innovation: Networks of learning in biotechnology. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(1), 116–145. doi: 10.2307/2393988

- SCB. (2014, April 6). Hierarkisk visning från avdelningsnivå och nedåt enligt SNI Retrieved from Swedish statistics http://www.sni2007.scb.se/snihierarki2007.asp?sniniva=2&snikod=14&test=20

- Simmie, J., & Martin, R. (2010). The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Cambridge Journal of Regions Economy and Society, 3(1), 27–43. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsp029

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Strobl, A. (2014). What ties resources to entrepreneurs?–activating social capital. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 6(2), 140–161. doi: 10.1504/IJEV.2014.062749

- Strobl, A., & Kronenberg, C. (2016). Entrepreneurial networks across the business life cycle: The case of alpine hospitality entrepreneurs. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(6), 1177–1203. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-03-2014-0147

- Turok, I. (2003). Cities, clusters and creative industries: The case of film and television in Scotland. European Planning Studies, 11(5), 549–565. doi:10.1080/0965431032000088515 doi: 10.1080/09654310303652

- Uzzi, B. (1996). The sources and consequences of embeddedness for the economic performance of organizations: The network effect. American Sociological Review, 61(4), 674–698. doi: 10.2307/2096399

- Uzzi, B. (1997). Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(1), 35–67. doi: 10.2307/2393808

- Uzzi, B. (1999). Embeddedness in the making of financial capital: How social relations and networks benefit firms seeking financing. American Sociological Review, 64(4), 481–505. doi: 10.2307/2657252

- Zander, I. (2004). The microfoundations of cluster stickiness—walking in the shoes of the entrepreneur. Journal of International Management, 10(2), 151–175. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2004.02.002

- Zaring, O., & Eriksson, C. M. (2009). The dynamics of rapid industrial growth: Evidence from Sweden’s information technology industry, 1990–2004. Industrial and Corporate Change, 18(3), 507–528. doi:10.1093/icc/dtp010