ABSTRACT

The paper analyses with a case study the use of a widely applied normative concept of polycentricity as spatial imaginary. The case study of Helsinki City Plan and the conflict over its city-boulevard scheme draws on qualitative content analysis of planning documents and expert interviews. It demonstrates the instrumental role of multiple interpretations of polycentricity in tension-ridden metropolitan and city-regional spatial planning. The conflict reveals how the conceptual ambiguity of polycentricity and the institutional vagueness of city-regional planning have together enabled advancing contradictory political aims under their guise. In conclusion, the paper emphasizes the persuasive performativity and fluidity of polycentricity as a spatial imaginary in multi-scalar planning settings.

Introduction

In the future, Helsinki will be an urban, rapidly growing rail transport network city with expanding central areas coupled with other developing centres. Commuter trains and the metro will offer fast rail connections between the central areas and other parts of Helsinki. The light rail network will complement this traffic system, making it a highly efficient network. The city will be concentrated along the transverse traffic routes, the expanding centres and in what are currently highway-like areas (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2013c, p. 5)

In this study, we aim to make sense of the process that led to the surfacing of this conflict. The city region of Greater Helsinki does not exist in any formal sense, as there is no sole administrative body or statutory plan to govern it. It is generally considered as an entity somewhat covering the functional urban region and being constituted of 14 municipalities that co-operate primarily on a voluntary basis. We intend to reveal that the weak institutionalization of city-regional planning in Greater Helsinki has afforded strategic leeway to individual municipalities in the city region to forward their own land use interests under the seemingly shared imaginary of polycentricity. Such leeway has also been enabled by the vagueness of the concept of polycentricity, which has been detected in previous studies (e.g. Davoudi, Citation2003; Rauhut, Citation2017; Schmitt, Citation2013; Shaw & Sykes, Citation2004; van Meeteren, Poorthuis, Derudder, & Witlox, Citation2016). While there is abundant research on the manifold conceptualisations of polycentricity (e.g. Meijers, Citation2008; van Meeteren et al., Citation2016), what has remained empirically understudied is the intentional use of the conceptual vagueness of polycentricity as a strategic tool in generating joint coordination and political legitimacy at the city-regional level (cf. Bergsli & Harvold, Citation2017; Schmitt, Citation2013). To analyse this, we associate polycentricity with the concept of ‘spatial imaginary’ (e.g. Davoudi et al., Citation2018). We chose the concept as an analytical frame as it captures the nature of polycentricity both as a planning concept and as a planning space, and, further, as a concept affording multiple interpretations and legitimizing material practices.

In this article, we will first present the concept of spatial imaginary and examine the concept of polycentricity as a spatial imaginary, in connection to its various definitions given in spatial planning and geographical research. Then we will introduce the case: the Helsinki City Plan and the conflict over its city-boulevard scheme. By drawing on qualitative content analysis of planning documents and expert interviews, we aim to explain the conflict through the different and – as we aim to reveal – discordant interpretations of polycentricity that operationalize it as a planning goal at different planning scales. Without referring to city-regional polycentricity directly (ESPON Citation1.Citation1.Citation1, Citation2005), the Helsinki City Plan imposes a certain city-regional structure. It presents an interpretation of polycentricity, which co-aligns, to a degree, with the functional interpretation of polycentricity at the city-regional scale. On the other hand, regarding morphological interpretation, the boulevardisation idea in the plan advances (city-)regional monocentricity, not polycentricity. With these city-regional implications of the Helsinki City Plan, the different city-regional interpretations of polycentricity reveal their discordance and an underlying conflict on the favoured urban structure and system between the actors mobilizing them.

We argue that the soft governance of Helsinki city-regional planning has enabled, until now, the use of polycentricity as a pacifying spatial imaginary, rather than an integrative planning strategy (e.g. Humer, Citation2018; Schmitt, Citation2013; Shaw & Sykes, Citation2004). As such, its different interpretations have concealed a non-agreement on the pursued city-regional structure and system. The case thus addresses both conceptual ambiguities and institutional voids related to the uses of the concept of polycentricity, for the analysis of which the concept of spatial imaginary provides a novel approach. We aim to contribute to the academic discussion on spatial imaginaries by drawing attention to the persuasive performativity and varied uses of polycentricity as a fluid spatial imaginary in tension-ridden metropolitan and city-regional planning.

Spatial imaginaries

Spatial planning concepts contain and perform specific spatial imaginaries (Davoudi et al., Citation2018, p. 97). Although spatial imaginaries retain many incarnations, for example, in geographical imagination (Said, Citation1978), socio-political theory (Anderson, Citation1983; Castoriadis, Citation1987; Taylor, Citation2004), and cultural political economy (Sum & Jessop, Citation2013), they can be defined as selective ‘mental maps’ into complex spatial reality (Jessop, Citation2012, p. 17), which give sense to, enable, and legitimise collective spatial practices. Imaginaries are operationalized and propagated, for example, through texts, stories, and images (Davoudi et al., Citation2018, p. 101).

Spatial imaginaries are both descriptive and prescriptive. In their selective representation and discursive construction of spatial phenomena, spatial imaginaries frontstage some spatial issues, thus supplanting alternative or competing imaginaries (Boudreau, Citation2007; Olesen, Citation2017; Sum & Jessop, Citation2013). They either assign distinct characteristics to a place or base on ‘idealised models’, which contain and convey guidelines for action (Golubchikov, Citation2010; Watkins, Citation2015). As such, spatial imaginaries become materialized as certain normative politics and practices of spatial planning, which reproduce and reinforce them (Baker & Ruming, Citation2015; Luukkonen & Sirviö, Citation2017; Wetzstein, Citation2013). In this regard, many authors have highlighted their performative role in constructing spaces and spatial relations (e.g. Baker & Ruming, Citation2015; Bialasiewicz et al., Citation2007; Watkins, Citation2015). As Jessop (Citation2012, p. 17) has summarized, imaginaries, and the spatial planning concepts that carry them, guide present and future (non-)decisions and (in-)actions and play a performative role, when intense expectations unfold to mobilize resources, produce incentives, and justify certain actions in preference to other ones.

Imaginaries are collectively held broad conceptual frameworks of representation and interpretation, and as such, cannot be reduced to interests of certain groups or works of individual imagination (Davoudi et al., Citation2018). Hincks, Deas, and Haughton (Citation2017, p. 4) emphasize that the appeal of imaginaries to policymaking rests largely on their imprecision and fluidity. Imaginaries allow policymakers to construct particular readings of a problem and to propose appropriate solutions depending on their own viewpoints and material interests. Consequently, they enable arguments for many different political views and interests, thereby interlinking even adversarial interest groups (Sum & Jessop, Citation2013; Wetzstein, Citation2013). It has been shown that the employment of existing imaginaries, or the construction of new ones, can help actors to negotiate complex and contested issues, securing agreement on ways of moving forward and generating joint meaning and action (Boudreau, Citation2007; Vigar, Graham, & Healey, Citation2005; Wetzstein, Citation2013). Discursive and material coalitions can thus emerge around resonating imaginaries (Hincks et al., Citation2017; Jessop & Oosterlynck, Citation2008; Wetzstein, Citation2013).

However, for the purpose of our study, it is important to emphasize that the enactment of flexible imaginaries can also induce disagreement and contestation (Jonas, Citation2014; Levy & Spicer, Citation2013). On the one hand, there always exists a plurality of competing interpretations of spatial imaginaries, operating at different scales and expressing different spatial logics; and problems occur in making these complementary (Harrison & Growe, Citation2014). On the other hand, because an imaginary does not have a fixed meaning (Davoudi et al., Citation2018; Vigar et al., Citation2005), its new situational readings may create mutually discordant interpretations of its meaning, leading to failures in policy coordination (cf. van Duinen, Citation2013). Drawing on Laclau’s and Lacan’s theoretical work on empty signifiers, Gunder and Hillier (Citation2009) argue that this is because planning concepts are inherently open to different significations of meaning depending on the discourses they are attached to, thus encapsulating various meanings under a single term. Such concepts may temporarily gain a fixed meaning and perform crystallisation points in a specific discourse, but also overflow with different interpretations (Laclau, Citation2015; cf. Kooij, van Assche, & Lagendijk, Citation2014). Imaginaries may thus become fuzzy and depoliticized in their self-evident but ambiguous merit (Davoudi et al., Citation2018, p. 98; Olesen & Richardson, Citation2011). As such, imaginaries may guarantee only surface agreements without providing guidelines for action (Brand & Gaffikin, Citation2007) and disguise actual policy interests promoted under a seemingly unifying imaginary (Healey, Citation2007, p. 232). As we later in this article aim to reveal, in the city-regional planning and local master planning of Helsinki, polycentricity served as a seemingly unifying spatial imaginary.

Polycentricity as spatial imaginary

The concept of polycentricity has gained widespread currency in planning and spatial development strategies (e.g. Davoudi, Citation2003; Kloosterman & Musterd, Citation2001; van Meeteren et al., Citation2016; Waterhout, Zonneveld, & Meijers, Citation2005). The interest in polycentricity links with city-regional development, following the observation that city regions increasingly often display polycentric characteristics (Lambregts, Citation2009). They have resulted from growth and outflow of activities from the urban cores, which have clustered to sub-centres due to agglomerative economic forces, or from integration of historically distinct cities, to benefit from economies of scale (Kloosterman & Musterd, Citation2001; Meijers, Citation2007; Parr, Citation2004). On the other hand, polycentricity has not emerged only as a concept used for describing the changing internal spatial organization and regionalization of growing urban areas (e.g. Batten, Citation1995; Graham & Marvin, Citation2001; Sieverts, Citation2003), but also as a normative concept for spatial planning at various scales (Davoudi, Citation2003), promoted not least by the European Union (e.g. ESPON Citation1.Citation1.Citation1, Citation2005). Indeed, this conceptual ambivalence is a key characteristic of polycentricity when used as a spatial imaginary. Polycentricity as a normative concept refers to active encouragement of polycentric spatial development as a policy objective. However, polycentric spatial development involves numerous and varying definitions (e.g. Davoudi, Citation2003; Lambregts, Citation2009; van Meeteren et al., Citation2016). These are operationalized through images and textual planning practice. In our case study, we are interested in how the spatial imaginary of polycentricity is interpreted in planning texts at different planning scales.

In a literal sense ‘polycentric’ merely denotes that a spatial entity consists of multiple centres, while not specifying how many or what kind of centres there are or whether and how they are connected (Schmitt, Citation2013). Beyond this, there are many different definitions of polycentricity. A morphological definition of a polycentric area is the crudest, indicating the presence of multiple centres in a given area, as well as their equal sizes and spacing. Complementarily to the previous, a functional definition requires networking between the centres, emphasizing their multidirectional connections and flow patterns (Burger & Meijers, Citation2012, p. 1128; Green, Citation2007). These emerge when the centres become functionally differentiated, which leads to their specialization and complementarity (Kloosterman & Musterd, Citation2001, pp. 626–627; Meijers, Citation2007). Functional polycentricity is informed by and closely relates to the network city theory and concept (e.g. Camagni & Capello, Citation2004).

The concept of polycentricity is also scale-sensitive, as it can be applied to describe and prescribe polycentric development in an intra-urban scale, inter-urban scale, inter-regional scale, or further macro scales. In reference to different scales, polycentricity describes different kinds of polycentric structures and deals varyingly with policy goals attached to its promotion, such as counteracting urban sprawl, reducing regional disparities and increasing competitiveness (Davoudi, Citation2003; Schmitt, Citation2013). As Hall (Citation2003, p. 199) aptly notes ‘What is monocentric at one level can be polycentric at another.’ In practical terms, this means that a particular measure may, for instance, support polycentricity at the inter-regional level, undermine it at the inter-urban level and again support it at the intra-urban level (Eskelinen & Fritsch, Citation2009, p. 608). However, while applicable at different scales, polycentricity is not hierarchically scalable. Jessop, Brenner, and Jones (Citation2008) argue that the structuring principle of polycentricity, applied to any place, is network. Because any field of operation contains only one structuring principle, network and scale become contradictory. Therefore, in reference to different scales, the interpretations of polycentricity can include discordant meanings and strategic goals – e.g. polycentric Helsinki in a monocentric Greater Helsinki city region, or monocentric Helsinki in a polycentric Greater Helsinki city region.

In addition to conceptualizing polycentricity in morphological or functional terms, or by its scalar qualities, it can also denote relational polycentricity, indicating a strategic, political, or institutional definition of polycentricity (Giffinger & Suitner, Citation2015; Halbert, Citation2008; Meijers, Hoogerbrugge, & Cardoso, Citation2018). According to Giffinger and Suitner (Citation2015, p. 1174), this type of polycentricity emerges from political-institutional relations and strategic networking between municipalities. Giffinger and Suitner further argue that both morphological and functional polycentricity can serve as a basis for strategic-relational cooperation, however, requiring cognitive envisioning and processual understanding of the layers of polycentric development. Thus, relational polycentricity as a spatial imaginary emphasizes soft network-based governance forms and spaces (e.g. Albrechts, Citation2001; Parr, Citation2004; Schmitt, Citation2013).

Identifying and establishing an appropriate mode of governance that would correspond to the layers of the polycentric metropolitan or city-regional system has remained a challenge (e.g. Kloosterman & Musterd, Citation2001; van Houtum & Lagendijk, Citation2001). Creating soft city-regional governance arrangements alongside the existing ‘hard’ institutional local and regional authorities may lead to the generation of a city-regional ‘institutional void’, in Hajer’s terms (Hajer, Citation2003; see also Salet, Citation2018). Such a void may open up strategic room for manoeuvre to individual municipalities for pushing their own self-regarded land use interests behind the guise of a shared city-regional spatial imaginary (Hytönen et al., Citation2016). The fluidity of the spatial imaginary of polycentricity may then be utilized in such manoeuvres (cf. Jensen & Richardson, Citation2003). However, the imaginary might also bring different actors together, and it has provided an integrative strategy for many city regions of Europe (e.g. Oliveira & Hersperger, Citation2018; Shaw & Sykes, Citation2004), for example, for reaching densification and competitiveness goals (Schmitt, Citation2013). Similarly, polycentricity has successfully been used as an integrative concept at inter-city (Meijers et al., Citation2018) and national levels (Humer, Citation2018).

Polycentric Greater Helsinki

The city region of Greater Helsinki does not exist in any formal sense, because it does not have an administrative body responsible over its governance. In functional and morphological terms, Greater Helsinki has been perceived as the only properly polycentric city region in Finland (Joutsiniemi, Citation2010; Vasanen, Citation2012; Ylä-Anttila, Citation2010). When defined ‘bottom-up’, based on statistical and GIS-analysis of work – and shopping-related commuting, it appears as a functional urban region, spawning 100 km around Helsinki, with around 1.5 million inhabitants and 700,000 jobs (2010) (Söderström, Citation2014, p. 98). The municipalities of Helsinki, Vantaa, Espoo and Kauniainen form the core area of the functional urban region, including around 65 percent of its inhabitants and 78 percent of jobs. The core area has strong functional ties and a distinctive structure of sub-centres. Vasanen (Citation2012) claims that the core area is polycentric more in functional than morphological terms, with the city centre of Helsinki dominating with its strong regional role. Yet, the number and status of the sub-centres has increased, especially in their role as job agglomerations, which the increase in commuter traffic echoes (Söderström, Citation2014, p. 106, 156; Vasanen, Citation2012, p. 3636). The functional polycentricity does not expand beyond the core area. The broader functional urban region is orientated towards it, utilizing rail, bus, and car accessibility (Suomen Ympäristökeskus, Citation2012).

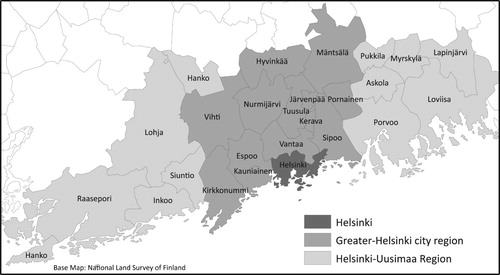

Establishing a mode of governance that would correspond to the layers of polycentric city-regional system has remained a challenge in Greater Helsinki. The Finnish governance system consists of the national government, 18 regions, and around 300 local authorities. Consequently, a sole administrative body does not govern the Greater Helsinki city region which, with its 14 local authorities, forms a part of the broader Helsinki-Uusimaa region (). The responsibility of land use planning lies, accordingly, with the regional and local level, and the statutory land use planning system involves three planning levels in a hierarchically binding order: regional land use plan, local master plan and local detailed plan (local authorities may also draft a joint local master plan). These plans are defined in content and process by planning legislation (Land Use and Building Act, Citation1999/Citation132, Citation1999) and need to comply with the National Land Use Objectives (Valtioneuvosto, Citation2017), which define objectives for land use in the whole country. Planning at the city-regional level, in turn, bases on voluntary co-operation of local governments. The 14 municipalities of Greater Helsinki have jointly drafted non-statutory city-regional plans since 2011. Currently, they are implementing the MASU 2050 –Land Use Plan of Greater Helsinki (Helsingin Seudun Maankäyttösuunnitelma, Citation2015), which operates alongside the statutory Regional Land Use Plan for the Helsinki-Uusimaa Region (Uudenmaan liitto, Citation2014). To enforce the implementation of the MASU 2050 –plan, the Central Government has signed a letter of intent with the municipalities, concerning the sharing of investments and responsibilities namely in major transport projects and the supply of subsidized housing.

Figure 1. Location of the City of Helsinki, City region of Greater Helsinki and Helsinki-Uusimaa region.

In the Finnish planning system, local governments have a strong political autonomy and legal-institutional role in determining their land use policies. The verbal National Land Use Objectives are rather superficial and the regional land use plans have tended to be reactive to local governments’ land use aspirations, although in the planning system, they are superior to local level plans (e.g. Puustinen & Hirvonen, Citation2006; Sairinen, Citation2009, p. 277). Furthermore, the steering capacities of voluntary city-regional plans, such as the MASU 2050 –plan, have been questioned, in the face of continuing inter-municipal competition on investments and tax-payers (citizen and corporate taxes) (Hytönen et al., Citation2016; Mäntysalo, Kangasoja, & Kanninen, Citation2015, pp. 170–171).

Contrary to city-regional land use planning, which lacks a joint city-regional planning authority, there is a joint city-regional authority responsible for public transport, the Helsinki Regional Transport Authority (HSL). Its members include the nine municipalities of Helsinki, Espoo, Vantaa, Kauniainen, Kerava, Kirkkonummi, Sipoo, Siuntio, and Tuusula, which have defined joint objectives in the Helsinki Region Transport Plan (HLJ –plan) (HSL, Citation2015).

The case of Helsinki City Plan

In this section, we introduce the case of Helsinki City Plan 2016. First, we present the content of the plan and the assessments of its city-regional impacts, which led to critical statements towards the plan as well as appeals to the Regional Administrative Court and to its consequent ruling. Subsequently, we analyse the unfolding of the conflict by identifying different interpretations of the imaginary of polycentricity in planning documents. The approach is motivated by previous studies (e.g. Hincks et al., Citation2017; Vigar et al., Citation2005; Wetzstein, Citation2013), which have found fluid spatial imaginaries to consolidate different interpretations, prone to diverse interests and discursive contexts. The interpretations are identified through content analysis of the key planning documents guiding spatial planning of the city and the city region of Greater Helsinki: National Land Use Objectives, Regional Land Use Plan for Helsinki-Uusimaa 2014, MASU 2050 –plan, HLJ –plan, and Helsinki City Plan 2016. The interpretations refer varyingly to the key elements of the spatial imaginary of polycentricity outlined in the previous section: structure (functional/morphological), scale, and normative policy goals. Finally, we reveal the discordance of interpretations, and the city-regional spatial structure they imply, through the analysis of statements made on the Helsinki City Plan. We relate this discordance to the emergent relational imaginary of polycentric network governance.

Alongside planning documents, the empirical data that we use in our analysis consist of the Regional Administrative Court’s decision report, and 25 official statements on the plan by the other municipalities of the region, regional actors, and ministries of the central government. In our reflections on the document analysis, we draw on 14 semi-structured interviews conducted with experts and academics working with issues related to spatial planning in Greater Helsinki. The interviewed experts and academics included nine senior researchers employed by universities, research institutes, and private consultancies, as well as three civil servants from the Ministry of Environment, which is the Finnish ministry in charge of land use planning issues. The interviews were conducted in August-September 2016, recorded, and fully transcribed. The direct quotes are translations by the authors and not linked to the names of the interviewees, to ensure anonymity.

Helsinki City Plan and its city-regional impacts

The City of Helsinki adopted the new Helsinki City Plan in 2016, replacing the previous plan from 2002. With the plan, Helsinki prepares for its growth by 252,000 inhabitants by 2050 (636,576 inhabitants in 2017). To enable this growth, the Helsinki City Plan delivers the vision and urban structure of rail-based ‘network city’ (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2016, p. 12, 16). According to the vision document (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2013c, pp. 70–78), the urban structure of rail-based ‘network city’ is to be achieved with (1) outward expansion of central Helsinki; and (2) turning sub-urban centres into a centre network, connected by efficient rail transport.

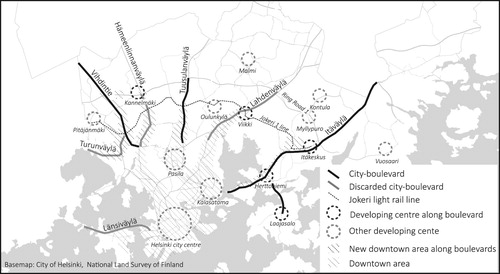

The outward expansion of central Helsinki is pursued by increasing the efficiency of land use along all arterial highways within Ring Road 1, by transforming them into urban spaces. This so-called ‘boulevardisation’ of the highway arteries involves reducing car lanes and driving speed on the roads, as well as adding light rail (or possibly metro) lines and biking lanes onto them, and densifying the urban structure alongside them. One third of the planned new housing volume (for 80,000 inhabitants) is located in the areas to be boulevardised (). In this regard, the city-boulevards are primarily a land-use development initiative to expand central Helsinki. They are expected to respond to increasing and unforeseen demand for urban living, generate economic agglomeration benefits, and increase attractiveness and competitiveness of central Helsinki. They are aimed to remove the barrier effect of highways, thus connecting previously isolated neighbourhoods and opening up new land reserves for extensive infill development for the needs of the growing city (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2013b, Citation2013c, pp. 70–71, Citation2016, pp. 20–32).

Figure 2. The ratified and non-ratified city-boulevards, new downtown areas along them, and developing centres both along and adjacent to the city-boulevards.

The city-boulevards are also a transport solution; a key element in the building of the rail-based network city for supporting sustainable urban structure (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2013c, p. 10). While radial public transport connections are improved with the light rail lines along the city-boulevards, the transversal connections are to be improved with the so-called ‘Jokeri 1’ and ‘Jokeri 2’ light rail lines, which intersect with the city-boulevards. Thus, these improvements contribute to creating a networked rail transport system (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2016, p. 22, 54–55, 60). According to the City Board (Helsinki Region Administrative Court Citation2018, p. 83), the city-boulevards create preconditions for developing the suburban centres into a multi-centre network (see City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2016, p. 105). The city-boulevards would improve their accessibility and create possibilities for developing sub-centres at the nodes of rail transport, particularly where the Jokeri 1 line meets the city-boulevards, such as in Itäkeskus, Käpylä, and Viikki (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2016, p. 22, 54–55, 60). The sub-centres are to be developed as distinctive towns with abundant urban amenities. This is intended to enable an urban lifestyle also outside the conventional downtown area and improve accessibility of services by non-motorized transport. When well-connected sub-centres develop and central areas expand, the relative functional importance of the current downtown core decreases. However, the expanding central Helsinki should remain as the main centre of the polycentric metropolitan area (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2016, p. 16).

As part of the planning process, the city-boulevards were subject to a number of impact assessments. On the one hand, they were approached as an initiative with the most potential for managing the growth of Helsinki in a sustainable manner, and with the most significant impacts to its urban structure and transport system (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2015, Citation2016). According to the assessments, the city-boulevards would enable increasing the supply of much demanded urban housing and business spaces in well-accessible locations close to downtown Helsinki, as well as improve the accessibility by non-motorized transport in Helsinki, especially in the inner areas enveloped by Ring Road 1 (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2013a, Citation2013b, Citation2015; City Planning Department of Helsinki and HSL, Citation2015). On the other hand, the city-boulevards were assessed to reduce the motorized traffic flow capacity of the arterial roads by 50 percent. The decreased capacity would likely congest the traffic within and beyond the city-boulevards and increase the travel times to downtown Helsinki by cars and buses from the other parts of the city region and the rest of the country, reducing its accessibility. Furthermore, while the city-boulevards were assessed to enable densification of the urban structure inward from Ring Road 1, the assessed impacts on the urban structure outward from it might be reverse (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2013a, Citation2015).

The assessments of regional and national impacts of city-boulevards motivated local, regional, and national actors to submit non-supportive official statements during the statutory hearing period of the plan proposal (Land Use and Building Act 2000, §62). Although the City of Helsinki issued a more comprehensive city-regional evaluation of city-boulevards as a result, the final Helsinki City Plan report concluded that the city-boulevards would not remarkably impact transport, in terms of increased travel times or congestion. Consequently the city-boulevards were left almost unchanged in the revised plan (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2016). The local authorities have a strong autonomy in local master planning in Finland, leaving stakeholders unable to enforce changes to the plan during the planning process. As in this case Helsinki did not make notable revisions to the plan, the Finnish Transport Agency and the regional state agency Uusimaa Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment, resorted to appeal to the Regional Administrative Court against Helsinki’s decision of approval of the Helsinki City Plan. The appeal argued that four city-boulevards did not meet up their status as regional and national traffic routes – the status which they are given in the superior and statutory Regional Land Use Plan for Helsinki-Uusimaa. The regional plan requires unrestricted motorized traffic flow capacity for these arteries. Based on the appeal, the Court overruled these four city-boulevards. Although the City of Helsinki appealed to the Supreme Administrative Court on the Regional Administrative Court’s overruling of the four city-boulevards, the ruling was maintained. The Helsinki City Plan was ratified in December 2018, excluding the areas overruled by the Regional Administrative Court.

Different interpretations of the imaginary of polycentricity

The polycentric and networked city region has emerged as a spatial imaginary in national, regional and city-regional statutory and non-statutory plans that portray common intent for the development of Greater Helsinki. All these plans and guidelines make either explicit or implicit reference to polycentricity as a city-regional planning goal (cf. Schmitt, Citation2013). In general, to reflect and manage the emerging spatial structure of the city region, the plans endorse a well-functioning and densified structure, which is polycentric and founded around a network of public transport connections. However, interpretations of polycentricity presented in the planning documents vary, emphasizing either spatial balance (the morphologically balanced polycentric spatial structure) or sustainable transport (the functionally networked rail-based transport system).

Regional and city-regional spatial balance interpretation. The Regional Land Use Plan for Helsinki-Uusimaa (Uudenmaanliitto, Citation2014) and the MASU 2050 –plan (Helsingin Seudun Maankäyttösuunnitelma, Citation2015) take a morphologically balanced polycentric spatial structure as a planning goal at regional and city-regional scales. They stipulate that spatial planning should promote balanced spatial structure around a network of existing centres for avoiding a core–periphery distinction and for combating urban sprawl. For example, MASU 2050 –plan envisions that Greater Helsinki will develop as a functional and attractive metropolitan area, in which a dense urban core and a surrounding network of distinctive centres form an integrated spatial structure. Both plans emphasize densification of existing centres and development located along rail and bus transit corridors. MASU 2050 –plan concretizes the densification goal with allocation of 80 percent of new housing to the core areas around the Helsinki city centre, to areas along the three main railway lines and to existing municipal centres served by bus transport. The regional land use plan concretizes the aim to densify urban areas along rail and bus corridors by defining a hierarchical centre network. In the core area, the plan recognizes a network of well-connected sub-centres, the role of which is seen to increase. The development of municipal centres outside the core area is seen to contribute to a more balanced regional spatial structure and equal accessibility of services and jobs in the whole region.

City-regional sustainable transport interpretation. The other city-regional planning goal, referred primarily in the HLJ –plan (HSL, Citation2015) and the National Land Use Objectives, is the development of a network-like transport system for fostering the use of sustainable transport modes, contributing positively to functional accessibility and competitiveness of the city region, and combating urban sprawl with simultaneous densification. The previous National Land Use Objectives (Valtioneuvosto, Citation2008), updated in 2017 (Valtioneuvosto, Citation2017), instructed spatial planning to pursue a well-functioning spatial structure, which is ‘polycentric, networked, and founded around good transport connections’. In Greater Helsinki, the urban structure should develop around public transport, especially rail transport, for decreasing car dependency. The HLJ –plan takes a similar stand. With the main objective to increase the use of sustainable transport modes and to reduce traffic overall, the plan envisions a networked transport system, based on strong and expanding rail connections, complemented with bus transport. Public transport nodes of the network emerge as important areas and possibly even as new hubs, where walkability and urbanity should be encouraged.

A city-regional imaginary of polycentricity has appeared attractive to the municipalities of Greater Helsinki, which have pronounced their commitment to the implementation of city-regional plans. While the thematic of polycentricity is only emerging as an issue in the outer fringe municipalities, the three most populous municipalities in the core area, Helsinki, Espoo and Vantaa, have adopted polycentricity as an explicit planning objective. At first glance, the Helsinki City Plan also seems to align with the interpretations of spatial balance and sustainable transport, as its objective is to develop a functionally connected multi-centre structure. However, when interpreting polycentricity, the Helsinki City Plan refers to developing a sustainable transport network only within Helsinki’s municipal borders. It aims at developing a local multi-centre structure, where central Helsinki, however, is to grow as the most important centre of the metropolitan area. In the Helsinki City Plan, polycentricity is interpreted as a means to increasing urban attractiveness and sustainability ().

Table 1. Interpretations of polycentricity.

In Helsinki’s urban attractiveness and sustainability interpretation, polycentricity refers to a growing network of urban mixed-use centres connected by sustainable rail transport. Increasing functional connectivity and complementarity of densifying centres, accessible by sustainable transport modes, would improve service delivery and reduce car dependency in the growing city-region. The light rail system along radial city-boulevards and orbital routes would contribute to increased functional polycentricity. Furthermore, the multicentre structure would provide more opportunities for much-demanded urban living, which is viewed to increase the attractiveness of urban areas of Helsinki. Although a network of distinctive and complementary sub-centres would have a role in generating attractive spaces for urban living, such urbanity is mostly to be achieved by expanding central Helsinki with city-boulevards. This is aimed to foster the development of central Helsinki as the most competitive centre of the city-region and the whole country, and assist in utilising untapped agglomeration benefits (City Planning Department of Helsinki, Citation2013c, pp. 10–13, Citation2016).

Discordant interpretations concealing spatial politics

The official statements on the Helsinki City Plan by state, regional, city-regional and neighbouring municipal actors widely supported Helsinki’s overall objective of ‘network city’. The densification of land use, prioritization of non-motorized transport forms over the car, and improvement of orbital connections that the network city entails were also supported. Thus, at the local scale, Helsinki’s interpretation of polycentricity co-aligns with the city-regional sustainable transport interpretation of polycentricity.

On the other hand, the (city-)regional spatial balance interpretation was mobilized in the negative statements on the plan. As the statement of the City of Järvenpää (Citation2016) exemplifies: ‘Helsinki [city region] is a single functional labour market area, which should be developed as a balanced entity. The goal could be a polycentric network of urban areas, connected by rapid public transport.’ The statements raised the concern that with the focus on creating a more urban structure and reducing the accessibility of central Helsinki by motorized transport with boulevardisation, the Helsinki City Plan would over-emphasize the city-regional role of Helsinki and its central areas. Especially the fringe municipalities were concerned that reduced accessibility due to boulevardisation would negatively affect the attractiveness of centres in parts of the region served by motorized traffic, thus hampering the development of a balanced polycentric city-regional structure. In their view, hindering bus-based city-regional transport with boulevardisation would also involve a risk of turning bus-serviced areas to even more car-based and sprawled than today. Similarly, the regional and national actors emphasized the importance of finding solutions for safeguarding also regional and national bus transport in the functional labour market area, alongside rail.

With its view on polycentricity, Helsinki bypasses the city-regional scale, as an expert interviewee notes: ‘Helsinki views polycentricity only through its own city structure, which is the now expanding urban centre and sub-centres that are now labelled as urban centres. So, “urban” is the main theme’. The expert interviewees confirmed that as a result of boulevardisation, the core of Helsinki would grow in morphological terms. Thus, even at the local, and particularly city-regional scale, the plan arguably fosters a traditional monocentric morphological structure, rather than a polycentric one.

In my opinion, the aim is to expand Helsinki’s city centre, which is the main centre of the city region. If city-boulevards are a tool for its expansion and densification, it means that Helsinki city region will as a result obtain a larger main centre, both morphologically and functionally. The boulevards may increase the service and transport role of some sub-centres, but I do not see a great impact on the polycentric structure. (Expert interviewee)

In fact, with the city-boulevards, Helsinki wants to keep a lot of the (city-regional) growth to itself. (Expert interviewee)

The implications of Helsinki City Plan on the city-regional urban structure and system reveal that the ostensibly conforming city-regional interpretations of polycentricity are mutually discordant. The sustainable transport interpretation, based on principles of densification and prioritization of rail-based public transport, implies a less morphologically balanced city-regional structure. The achievement of spatial balance, in turn, would require both rail- and bus- (and car-) based accessibility. Beneath the discordant interpretations lies the key conflict on the city-regional structure and the distribution of growth and tax income between the municipalities. With Helsinki City Plan, Helsinki aims to capture much of this city-regional growth ().

Table 2. City-regional urban structure and system implied by the interpretations of polycentricity.

The municipalities’ competition over growth and tax income explains their support of either the more evenly growth-distributing spatial balance interpretation (morphological (city-)regional polycentricity) or the more selective (rail corridors) sustainable transport interpretation (functional city-regional polycentricity), according to their relative connectivity to the city-regional transport network.

(…) there is a conflict. (…) the expansion of the inner city creates supply of housing and jobs in the best location (in the region). For not all regional actors this is an optimal solution, as it weakens their accessibility and growth potential. (Expert interviewee)

Relational polycentricity: overcoming spatial politics?

In the city region of Greater Helsinki, the institutional landscape fragments into several municipalities. Whereas city-regional land use planning is based on voluntary cooperation between the municipalities, transport planning in the city region is organized through a joint authority, the HSL, which has drafted the HLJ –plan. Therefore, the interviewees saw that although a polycentric planning strategy has emerged, and has its strength in integrating transport and land use planning, the municipality-led land use planning and sub-regionally organized transport planning have created a conflict.

On the institutional level, there is a problem, which became now apparent in the interaction between the Helsinki City Plan and the HLJ –plan. HSL has emerged as a strong transport planning and service provision organisation. It is able to draft regional transport plans, which are politically accepted in the city region and truly guide the transport investments and projects. However, on the side of land use planning, there are the Regional Council and regional plan but they do not really guide planning in the core area (Helsinki, Espoo, Kauniainen, Vantaa), only in (…) the rest of the region. There is local master planning but a counterpart of city-regional transport planning is missing. (…) The mismatch between city-regional transport planning and municipal land use planning creates constant conflicts. (…) The municipal and regional administrative structure has a strong influence (on the conflict around the boulevards). (Expert interviewee)

The polycentric network-based city-region is conceptually very vague. If one carefully scrutinises, for example, the MASU 2050 and HLJ –plans, one can see a clear difference in their priorities. The HLJ –plan takes a clear position for the development of centres connected by rail; they should develop as the primary city-regional centres. On the contrary, the MASU 2050 –plan establishes rail-based centres and rural municipalities’ main centres as equally important, although there has not been courage to state this explicitly. (…) In my opinion, political correctness has led to this. (…) The main urban areas of each municipality have received a centre status, which is not dependent on their functional role (…) This is because the starting point is that there needs to be a structure which everybody can accept (…) The Helsinki City Plan then pursues the plan to prioritise the rail-based centres. (…) In this sense, the polycentric network-based city is a clever term; everyone can interpret it in their own way. (Expert interviewee).

Conclusion

Polycentricity has recently gained popularity as a strategic planning concept in metropolitan and city regions, and is frequently associated with goals of sustainability, cohesiveness and competitiveness (e.g. Davoudi, Citation2003; Schmitt, Citation2013). We argue that at least some of this popularity can be explained by examining polycentricity as a spatial imaginary.

Being a spatial imaginary, polycentricity may find support especially in institutionally fragmented city regions, as our case study exemplifies. In its fluidity, the imaginary is persuasive in affording the coexistence of different interpretations. Although polycentricity might serve in developing an integrative strategy, the many interpretations may also be used strategically to avoid conflicts and enable surface agreements (cf. Brand & Gaffikin, Citation2007), which are then conducted in soft and networked city-regional governance – which in itself follows the relational imaginary of polycentric governance. Underneath these surface agreements, diverging policy goals may be pursued in different arenas, choosing to fill the spatial imaginary of polycentricity with such content that is best suited for each goal. The spatial imaginary of polycentricity thereby masks the political goals that have brought it into being.

However, if the goals are mutually contradictory, the implementation of one of them at the others’ expense eventually reveals the discordance of the interpretations under the imaginary of polycentricity – as is the case with the Helsinki City Plan. In our analysis of the Helsinki City Plan case data, we identified three interpretations of polycentricity: (city-)regional spatial balance, city-regional sustainable transport, and urban attractiveness and sustainability. In view of polycentricity, each implies different functional and morphological planning choices, when ‘brought to the ground’. When viewed from its city-regional implications, the urban attractiveness and sustainability interpretation somewhat co-aligns in functional terms with the sustainable transport interpretation – but, in morphological terms, it contradicts with the spatial balance interpretation. By pursuing spatially the urban attractiveness and sustainability interpretation, the Helsinki City Plan revealed the discordance of (city-)regional interpretations, with regard to prioritized transport modes and distribution of growth.

In our case, the spatial imaginary of polycentricity served in maintaining the status quo of two city-regional interpretations of polycentricity, and underneath them the inter-municipal competition for investments and ‘good’ tax-payers in the growing city region. Thus, the ambiguity of the spatial imaginary of polycentricity served in preventing the formation of a properly strategic city-regional policy on what kind of spatial structure and system to aim for, and what kind of political choices it would mean. With the institutional ‘rules of the game’ (cf. Salet, Citation2018) missing in the city-regional realm, strategic room for such indecisiveness was kept open for the municipalities. This status quo was broken by the Helsinki City Plan that fostered the urban attractiveness and sustainability interpretation, in concrete functional and morphological terms – with repercussions on city-regional, regional and further national scales. However, with its ruling against the city-boulevards, the Regional Administrative Court finally resorted to the basic institutional rule of the Finnish land use planning system: the hierarchy of statutory planning levels.

The case study resonates with some earlier findings (e.g. Jessop et al., Citation2008) of difficulties in using network-based normative concepts in multi-scalar and hierarchical planning settings. However, our study is not critical to the concept of polycentricity as such. Instead, we hope to have raised critical awareness on the multiple and even contradictory political goals it lends itself to when used as an indeterminate spatial imaginary in institutionally vague arenas of ‘soft’ spatial governance.

Acknowledgements

Besides the three anonymous referees, we are grateful for Simin Davoudi for her comments on the earlier draft of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Kaisa Granqvist http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8113-5561

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albrechts, L. (2001). How to proceed from image and discourse to action: As applied to the Flemish Diamond. Urban Studies, 38(4), 733–745. doi: 10.1080/00420980120035312

- Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Baker, T., & Ruming, K. (2015). Making ‘Global Sydney’: Spatial imaginaries, worlding and strategic plans. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(1), 62–78. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12183

- Batten, D. F. (1995). Network cities: Creative urban agglomerations for the 21st century. Urban Studies, 32(2), 313–327. doi:10.1080/00420989550013103

- Bergsli, H., & Harvold, K.-A. (2017). Planning for polycentricity: The development of a regional plan for the Oslo metropolitan area. Scandinavian Journal for Public Administration, 22(1), 99–117.

- Bialasiewicz, L., Campbell, D., Elden, S., Graham, S., Jeffrey, A., & Williams, A. J. (2007). Performing Security: The imaginative geographies of current US strategy. Political Geography, 26(2007), 405–422. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.12.002

- Boudreau, J.-A. (2007). Making new political spaces: Mobilizing spatial imaginaries, instrumentalising spatial practices, and strategically using spatial tools. Environment and Planning A, 39(1), 2593–2611. doi:10.1068/a39228

- Brand, R., & Gaffikin, F. (2007). Collaborative planning in an uncollaborative world. Planning Theory, 6(3), 282–313. doi:10.1177/1473095207082036

- Burger, M., & Meijers, E. (2012). Form follows function? Linking Morphological and Functional Polycentricity. Urban Studies, 49(5), 1127–1149. doi: 10.1177/004209801140709

- Camagni, R., & Capello, R. (2004). The city network paradigm: Theory and empirical evidence. Contributions to Economic Analysis, 266(16), 495–529. doi:10.1016/S0573-8555(04)66016-0

- Castoriadis, C. (1987). The Imaginary Institution of Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- City of Järvenpää. (2016). Statement to the plan.

- City Planning Department of Helsinki. (2013a). Helsingin uuteen yleiskaavaan liittyvien liikennehankkeiden vaikutusten arviointi, Osa A. Moottoritiemäisten alueiden tarkastelut, 1–45.

- City Planning Department of Helsinki. (2013b). Helsingin yleiskaava. Helsingin kantakaupungin laajentaminen, Moottoritiemäisten ympäristöjen maankäytön tehostaminen ja muuttaminen urbaaniksi kaupunkitilaksi. Helsingin kaupunkisuunnitteluviraston yleissuunnitteluosaston selvityksiä, 2013(4), 1–44.

- City Planning Department of Helsinki. (2013c). Helsingin Yleiskaava. Visio 2050. Kaupunkikaava – Helsingin uusi yleiskaava. Helsingin kaupunkisuunnitteluviraston yleissuunnitteluosaston selvityksiä, 2013, 23.

- City Planning Department of Helsinki. (2015). Helsingin Yleiskaava. Kaupunkibulevardien seudulliset vaikutukset. Helsingin kaupunkisuunnitteluviraston yleissuunnitteluosaston selvityksiä, 2015, 5.

- City Planning Department of Helsinki. (2016). Helsingin Yleiskaava. Selostus. Kaupunkikaava-Helsingin uusi yleiskaava. Helsingin kaupunkisuunnitteluviraston yleissuunnitteluosaston selvityksiä, 2016, 3.

- City Planning Department of Helsinki and HSL. (2015). Raideliikenteen verkkoselvitys. Helsingin kaupunkisuunnitteluviraston liikennesuunnitteluosaston selvityksiä, 2015, 2.

- Davoudi, S. (2003). Polycentricity in European spatial planning: From an analytical tool to a normative agenda. European Planning Studies, 11(8), 979–999. doi:10.1080/0965431032000146169

- Davoudi, S., Crawford, J., Raynor, R., Reid, B., Sykes, O., & Shaw, D. (2018). Policy and practice. Spatial imaginaries: Tyrannies or transformations? TPR, 89(2), 97–124.

- Eskelinen, H., & Fritsch, M. (2009). Polycentricity in the Northeastern periphery of the EU Territory. European Planning Studies, 17(4), 605–619. doi:10.1080/09654310802682206

- ESPON Project 1.1.1. (2005). Potentials for polycentric development in Europe. Project report. Luxembourg: ESPON.

- Giffinger, R., & Suitner, J. (2015). Polycentric metropolitan development: From structural assessment to processual dimensions. European Planning Studies, 23(6), 1169–1186. doi:10.1080/09654313.2014.905007

- Golubchikov, O. (2010). World-city-entrepreneurealism: Globalist imaginaries, neoliberal geographies, and the production of new St Petersburg. Environment and Planning A, 42, 626–643. doi:10.1068/a39367

- Graham, S., & Marvin, S. (2001). Splintering Urbanism: Networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and Urban condition. London: Routledge.

- Green, N. (2007). Functional polycentricity: A formal definition in terms of social network analysis. Urban Studies, 44(11), 2077–2103. doi:10.1080/00420980701518941

- Gunder, M., & Hillier, J. (2009). Planning in ten words or less. A Lacanian entanglement with spatial planning. England: Ashgate.

- Hajer, M. A. (2003). Policy without polity? Policy analysis and the institutional void. Policy Sciences, 36, 175–195. doi:10.1023/A:1024834510939

- Halbert, L. (2008). Examining the mega-city-region hypothesis: Evidence from the Paris city-region/bassin parisien. Regional Studies, 42(8), 1147–1160. doi: 10.1080/00343400701861328

- Hall, P. (2003). In a lather about polycentricity. Town and Country Planning, 72(7), 199.

- Harrison, J., & Growe, A. (2014). When regions collide: In what sense a new ‘regional problem’? Environment and Plannning A, 46, 2332–2352. doi:10.1068/a130341p

- Healey, P. (2007). Urban complexity and spatial strategies. Towards a relational planning for our times. London: Routledge.

- Helsingin Seudun Maankäyttösuunnitelma. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.hel.fi/hel2/Helsinginseutu/Hsyk/Hsyk_141014/asia1liite2.pdf

- Helsinki Region Administrative Court. (2018). Päätös 18/0049/5.

- Hincks, S., Deas, I., & Haughton, G. (2017). Real geographies, real economies, and soft spatial imaginaries: Creating a ‘more than Manchester region’. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 642–657. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12514

- HSL. (2015). Helsingin Seudun Liikennejärjestelmäsuunnitelma. HLJ 2015. HSL:n julkaisuja 3/2015.

- Humer, A. (2018). Linking polycentricity concepts to periphery: Implications for an integrative Austrian strategic spatial planning practice. European Planning Studies, 26(4), 635–652.

- Hytönen, J., Mäntysalo, R., Peltonen, L., Kanninen, V., Niemi, P., & Simanainen, M. (2016). Defensive routines in land use policy steering in Finnish urban regions. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(1), 40–55. doi:10.1177/0969776413490424

- Jensen, O. B., & Richardson, T. (2003). Being on the map: The new iconographies of power over European space. International Planning Studies, 8(1), 9–34. doi:10.1080/13563470320000059246

- Jessop, B. (2012). Economic and Ecological Crises: Green new deals and no-growth economies. Development, 55(1), 17–24. doi:10.1057/dev.2011.10

- Jessop, B., Brenner, N., & Jones, M. (2008). Theorizing sociospatial relations. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26, 389–401. doi:10.1068/d9107

- Jessop, B., & Oosterlynck, S. (2008). Cultural political economy: On making the cultural turn without falling into soft economic sociology. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 39, 1155–1169. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.12.008

- Jonas, M. (2014). The dortmunt case – on the enactment of and urban economic imaginary. International Journal of Urban and Economic Research, 38(6), 2123–2140. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12092

- Joutsiniemi, A. (2010). Becoming metapolis: A configurational approach. Tampere: DATUTOP Occasional Papers.

- Kloosterman, R. C., & Musterd, S. (2001). The polycentric urban region: Towards a research agenda. Urban Studies, 38(4), 623–633. doi:10.1080/00420980120035259

- Kooij, H., van Assche, K., & Lagendijk, A. (2014). Open concepts as crystallization points and enablers of discursive configurations: The case of the innovation campus in the Netherlands. European Planning Studies, 22(1), 84–100. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.731039

- Laclau, E. (2015). Why Do empty signifiers matter to politics? In D. Howarth (Ed.), Ernesto Laclau, Post Marxism, populism & critique (pp. 66–74). London & New York: Routledge.

- Lambregts, B. (2009). The polycentric metropolis unpacked: Concepts, trends, and policy in the Randstadt Holland. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Institute for Metropolitan and International Development Studies.

- Land Use and Building Act 132/1999. (1999). Retrieved from https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990132.pdf

- Levy, D., & Spicer, A. (2013). Contested imaginaries and the cultural political economy of climate change. Organisation, 20(5), 659–678. doi: 10.1177/1350508413489816

- Luukkonen, J., & Sirviö, H. (2017). Kaupunkiregionalismi ja epäpolitisoinnin politiikka. Talousmaantieteellinen imaginaari aluepoliittisten käytäntöjen vastaansanomattomana viitekohteena. Politiikka, 59(2), 114–132.

- Mäntysalo, R., Kangasoja, J. K., & Kanninen, V. (2015). The paradox of strategic spatial planning: A theoretical outline with a view on Finland. Planning Theory & Practice, 16(2), 169–183. doi:10.1080/14649357.2015.1016548

- Meijers, E. (2007). Clones or complements? The division of labour between the main cities of the Randstad, the Flemish Diamond and the Rhein-Ruhr area. Regional Studies, 41(7), 889–900. doi:10.1080/00343400601120239

- Meijers, E. (2008). Measuring polycentricity and its promises. European Planning Studies, 16(9), 1313–1323. doi:10.1080/09654310802401805

- Meijers, E., Hoogerbrugge, M., & Cardoso, R. (2018). Beyond polycentricity: Does stronger integration between cities in polycentric urban regions improve performance. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 109(1), 1–21. doi:10.1111/tesg.12292

- Olesen, K. (2017). Talk to the hand: Strategic spatial planning as persuasive storytelling of the Loop city. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 978–993. doi:10.1080/09654313.2017.1296936

- Olesen, K., & Richardson, T. (2011). The spatial politics of spatial representation: Relationality as a medium for depolitization? International Planning Studies, 16(4), 355–375. doi:10.1080/13563475.2011.615549

- Oliveira, E., & Hersperger, A. (2018). Governance arrangements, funding mechanisms and power configurations in current practices of strategic spatial plan implementation. Land Use Policy, 76, 623–633. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.02.042

- Parr, J. (2004). The polycentric urban region: A closer inspection. Regional Studies, 38(3), 231–240. doi:10.1080/003434042000211114

- Puustinen, S., & Hirvonen, J. (2006). Alueidenkäytön suunnittelujärjestelmän toimivuus – AKSU. Helsinki: Suomen ympäristö 782, Ympäristöministeriö.

- Rauhut, D. (2017). Polycentricity- one concept or many? European Planning Studies, 25(2), 332–348. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.12761574

- Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Western conceptions of the Orient. UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

- Sairinen, R. (Ed.). (2009). Yhdyskuntarakenteen eheyttäminen ja elinympäristön laatu. Espoo: Yhdyskuntasuunnittelun tutkimus- ja koulutuskeskuksen julkaisuja B 96.

- Salet, W. (2018). Public norms and aspirations. The turn to institutions in action. New York: Routledge.

- Schmitt, P. (2013). Planning for polycentricity in European metropolitan areas—challenges, expectations and practices. Planning Practice & Research, 28(4), 400–419. doi:10.1080/02697459.2013.780570

- Shaw, D., & Sykes, O. (2004). The concept of polycentricity in European spatial planning: Reflections on its interpretation and application in the practice of spatial planning. International Planning Studies, 9(4), 283–306. doi:0.1080/13563470500050437

- Sieverts, T. (2003). Cities without cities: An interpretation of a Zwhischenstadt. London: Routledge.

- Söderström, P. (2014). Yhdyskuntarakenteen aluejaot Helsingin ja Tukholman kaupunkiseuduilla. In P. Söderström, H. Schulman, & M. Ristimäki (Eds.), Pohjoiset Suurkaupungit. Yhdyskuntarakenteen kehitys Helsingin ja Tukholman Metropolialueilla (pp. 98–117). SYKEN julkaisuja 2.

- Sum, N.-L., & Jessop, B. (2013). Towards a cultural political economy: Putting culture in its place in political economy. Chelteham: Edward Elgar.

- Suomen Ympäristökeskus. (2012). Yhdyskuntarakenteen toiminnalliset alueet Suomessa. Helsinki: Suomen Ympäristökeskus.

- Taylor, C. (2004). Modern social imaginaries. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Uudenmaan liitto. (2014). Uudenmaan 2. vaihemaakuntakaava.

- Valtioneuvosto. (2008). Valtioneuvoston päätös valtakunnallisista alueidenkäyttötavoitteista. Valtakunnallisten Alueidenkäyttötavoitteiden tarkistaminen. Retrieved from http://www.ymparisto.fi/fi-FI/Elinymparisto_ja_kaavoitus/Maankayton_suunnittelujarjestelma/Valtakunnalliset_alueidenkayttotavoitteet

- Valtioneuvosto. (2017). Valtioneuvoston päätös valtakunnallisista alueidenkäyttötavoitteista. Retrieved from http://www.ymparisto.fi/download/noname/%7B67CD97B8-C4EE-4509-BEC0-AF93F8D87AF7%7D/133346

- van Duinen, L. (2013). Mainport and corridor: Exploring the mobilizing capacities of Dutch spatial concepts. Planning Theory & Practice, 14(2), 211–232. doi:10.1080/14649357.2013.782423

- van Houtum, H., & Lagendijk, A. (2001). Contextualising regional identity and imagination in the construction of polycentric urban regions: The cases of the Ruhr area and the Basque country. Urban Studies, 38(4), 747–767. doi:10.1080/00420980120035321

- van Meeteren, M., Poorthuis, A., Derudder, B., & Witlox, F. (2016). Pacifying Babel’s Tower: A scientometric analysis of polycentricity in urban research. Urban Studies, 53(6), 1278–1298. doi:10.1177/0042098015573455

- Vasanen, A. (2012). Functional polycentricity: Examining metropolitan spatial structure through the connectivity of urban Sub-centres. Urban Studies, 49(16), 3627–3644. doi:10.1177/0042098012447000

- Vigar, G., Graham, S., & Healey, P. (2005). In search of the city in spatial strategies: Past legacies, future imaginings. Urban Studies, 42(8), 1391–1410. doi:10.1080=00420980500150730

- Waterhout, B., Zonneveld, W., & Meijers, E. (2005). Polycentric development policies in Europe: Overview and debate. Built Environment, 31(2), 163–173. doi:10.2148/benv.31.2.163.66250

- Watkins, J. (2015). Spatial imaginaries research in geography: Synergies, tensions, and new directions. Geography Compass, 9(9), 508–522.

- Wetzstein, S. (2013). Globalising economic governance, political projects, and spatial imaginaries: Insights from four Australasian cities. Geographical Research, 51(1), 71–84. doi:10.1111/j.1745-5871.2012.00768.x

- Ylä-Anttila, K. (2010). Verkosto kaupunkirakenteen analyysin ja suunnittelun välineenä. Tampere: Tampere University of Technology.