ABSTRACT

Trust is a key mechanism for explaining the ease and frequency of knowledge spillovers within regions. While the importance of trust is virtually uncontested, there have been few attempts to rigorously disentangle the way in which trust formation is related to space and proximity. The aim of this paper is to advance the understanding of trust formation in terms of its main antecedents within the context of regional studies. This is done by reviewing the rich literature on trust formation from psychology, sociology, and organization studies and connecting it conceptually to different types of proximity. In doing so, the paper maps out a number of avenues for future research on trust and geography.

Introduction

Over the last 15–20 years much has been written about learning and knowledge flows in regions and districts, not least within relational economic geography. Because knowledge is embedded in individuals, learning is to a high extent inter-personal and therefore dependent on social interaction, which in turn is facilitated by physical proximity and local embeddedness. The ability for collective learning and knowledge transfer is closely linked to social embeddedness, localized networks and buzz (Gertler, Citation2003; Malmberg & Maskell, Citation2006; Maskell, Citation2001). What started with a focus on geographical proximity and collocation has evolved into a more nuanced discourse about how different forms of proximity influence localized learning, knowledge spillovers, and social tie formation. A key issue in this literature is the geographical nature of proximity (Bouba-Olga, Carrincazeaux, Coris, & Ferru, Citation2015; Lagendijk & Lorentzen, Citation2007; Rutten, Citation2017) While widely agreed that geographical proximity alone is neither necessary nor sufficient for knowledge transfer or formation of social ties, it remains an important facilitative condition (Boschma, Citation2005; Torre & Rallet, Citation2005). Firstly, knowledge transfer takes place on different spatial scales and a combination of local and non-local network ties tend to be more conducive for creating a viable learning region (Boschma & Ter Wal, Citation2007; Morrison, Rabellotti, & Zirulia, Citation2013). Secondly, different forms of proximity as well as their interrelationships influence knowledge spillovers and learning: social, cultural, institutional, cognitive, technological, organizational, and geographical proximity (Balland, Boschma, & Frenken, Citation2015; Boschma, Citation2005; Huber, Citation2012; Knoben & Oerlemans, Citation2006; Lagendijk & Lorentzen, Citation2007; Torre & Rallet, Citation2005).

A core argument within the relational literature is that tacit knowledge flows, localized learning, exchange of complex knowledge, and mutual understanding are all greatly facilitated by trust-based localized networks (Powell, Koput, Bowie, & Smith-Doerr, Citation2002; Sunley, Citation2008). Where there is mutual trust, actors tend to interact and share information and knowledge more freely; information asymmetries, risk of opportunism and transaction cost are lower; and shared values, norms and attitudes tend to develop. This view has had a vast influence on theories on clusters, districts and milieus where trust is frequently referred to both as an outcome of collocation and a precondition or facilitator of localized learning and exchange (Molina-Morales, López-Navarro, & Guia-Julve, Citation2002).

Co-localized firms will, therefore, it is asserted, often benefit from the emergence of a general climate of understanding and trust that helps (i) to reduce malfeasance, (ii) to induce the volunteering of reliable information, (iii) to cause agreements to be honored, (iv) to place negotiators on the same wavelength, and (v) to ease the sharing of tacit knowledge. (Maskell, Citation2001, p. 926)

F2F can play important roles in mitigating these incentives and free-rider problems. One reason for this is simply that it is easier to observe and interpret a partner’s behavior in an F2F situation. […] Humans are very effective at sensing non-verbal messages from one another, particularly about emotions, cooperation, and trustworthiness. (Storper & Venables, Citation2004, p. 355)

This is the case even to the extent that the literature rarely links up with the vast body of trust research within psychology, sociology, organization studies, and economics. This is particularly surprising given that (i) trust is central to knowledge and information transfer and (ii) the literature on proximity types is based on a conceptual typology – cultural, social, behavioural, institutional – that overlaps with established conceptualizations of trust formation processes (Nilsson & Mattes, Citation2015). The aim of this paper is to advance the understanding of trust formation antecedents and provide a link between the literatures on trust and proximity.

Murphy (Citation2006) is among the few geographers who explicitly discuss trust formation in relation to space and collocation. He presents a framework disentangling trust-building processes at the macro, meso, and micro scale. While these processes are partially linked to space and locality its contribution is mainly a broader call for ‘considering and understanding the ways in which collaborative practices, trusting relationships, and network associations are situated within distinct times, places, and interactive spaces through particular combinations of materials, symbols, social practices, and institutions’. (p.443). In relation to Murphy’s work this paper points to a need to incorporate a temporal dimension, i.e. distinguishing between initial trust (trust formed in the absence of previous direct interaction between trustor and trustee) and gradual trust (trust that develops as a result of exchange between trustor and trustee). I.e. between impersonal and personal trust.

In a more recent example, Mathews and Stokes (Citation2013) goes a step further and attempt a conceptualization of the antecedents to trust formation in industrial districts. Like Murphy, they start from the observation that

while trust has been addressed and discussed in-depth in a range of situations and contexts, the origins of trust in an industrial district setting has received relatively minor attention (Staber, Citation2007), where trust is generally seen to grow from frequent face-to-face interactions (Mathews & Stokes, Citation2013, pp. 846–7).

These attempts at linking antecedents of trust formation to proximity typically focus on geographical proximity without considering that trust is both gradually developed over time and exist ex ante when actors initiate contacts. Given the highly interrelated nature of trust antecedents and their relationship to different proximity dimensions over time, a more comprehensive approach is needed. Only when the relationship between trust antecedents and proximity is disentangled can a conceptually grounded analysis take place.

The paper starts with a presentation of different types of proximity followed by a discussion of different types of trust and their respective antecedents. These are then integrated in order to delineate the way in which proximity influence the formation of initial and gradual trust. Lastly, conclusions and avenues for future research are presented and discussed.

Forms and types of proximity

The role of proximity is subject to much debate within economic geography and planning studies. Critiques of spatial fetishism and over-regionalization propose that the role of physical collocation has been exaggerated. One approach for dealing with over-regionalization is to adopt a broad view on proximity (Lorentzen, Citation2008; Rutten, Citation2017). Geographical proximity is seen as one of several types of proximity that influence interaction and knowledge exchange (e.g. Boschma, Citation2005; Huber, Citation2012; Knoben & Oerlemans, Citation2006; Lagendijk & Lorentzen, Citation2007; Torre & Rallet, Citation2005).

In order to link the proximity concept to trust formation, this paper focuses on five types: cognitive, social, institutional, cultural and geographical proximity. Geographical proximity refers to the physical distance between actors and lies at the heart of studies of regions and clusters. While geographical space is often the starting point in regional studies, its significance for learning lies mainly in that it facilitates and coincides with cognitive, cultural, social and institutional proximity (Malmberg & Maskell, Citation2006). Cognitive proximity is related to how actors’ perceive, interpret and evaluate the world according to mental models and categories (Huber, Citation2012). If there is great cognitive proximity between actors, they are well endowed to understand each other and communicate but at the same time, the opportunities for new influence and insights are limited (Nooteboom, Citation2000). Social proximity refers to the degree to which actors’ share personal relationships, often by means of past collaboration (Breschi & Lissoni, Citation2009). It is reminiscent of Granovetter’s (Citation1983) social ties, the strength of which are determined by the amount of time, emotional intensity, reciprocal services, intimacy and mutual confiding between actors. Social proximity thus largely evolves through interaction over time. A level of social proximity may however also exist between actors belonging to the same social or professional network even in the absence of a history of direct exchange. As shown by for example Gulati (Citation2007) new tie formation is more common when actors belong to the same network, largely due to second-hand referrals. While facilitative for tie formation, communication, and knowledge diffusion, too much social proximity can lead to a loss of economic rationale and relational lock-in (Boschma, Citation2005). Institutional proximity relates to the existence of a common institutional framework at the macro level. This entails both formal institutions, i.e. the ‘rules of the game’ and informal, i.e. conventions and codes of behaviour (Balland, Citation2012; North, Citation1990). Where there is high institutional proximity, the conditions for collaboration and interactive learning are familiar and stable, which reduces uncertainty and risk of opportunism (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2010; Gertler, Citation2004). Lastly, cultural proximity refers to shared language, codes and norms of communication and exchange between actors (Gertler, Citation1995). Culture is shared and accepted by – and therefore defines – a given group at a given time (Knoben & Oerlemans, Citation2006). While cultural proximity facilitates communication and interaction between actors, too much proximity risk leading to lock-in and inertia.

Scholars vary in their treatment of proximity dimensions. Boschma (Citation2005) for example considers cultural proximity to be part of institutional proximity while Knoben and Oerlemans (Citation2006) consider cognitive, institutional, cultural and social proximity as part of organizational proximity. For the purpose of this paper, the five types of proximity are kept separate as they correspond conceptually with the antecedents to trust formation.

Proximity dimensions are closely interrelated and in many cases mutually reinforcing. To illustrate, cognitive proximity is a precondition for effective and meaningful communication. This infers that where there is cognitive proximity, social proximity develops more easily. A result of strong interpersonal linkages and emotional closeness (high social proximity) is that actors develop an even deeper shared understanding about the world; i.e. greater cognitive proximity.

In regional studies, the starting point is typically the role played by geographical proximity and how other types of proximity are facilitated by collocation. While geographical proximity on its own is neither necessary nor sufficient for knowledge transfer and interaction to take place (Boschma, Citation2005), it is facilitative for other forms of proximity (Balland et al., Citation2015; Nilsson & Mattes, Citation2015). Collocated actors are more likely to interact, the nature of interaction is different insofar as there is greater possibility for face-to-face, and collocated actors are more likely to belong to the same networks (Gertler, Citation2003; Malmberg & Maskell, Citation2006; Storper & Venables, Citation2004). These exchange characteristics are directly facilitative for social, cultural, cognitive and (informal) institutional proximity. In addition to this, geographical proximity also tends to be correlated with the existence of shared formal institutions, as collocated actors are more likely to operate under the same national and state regulations and rules-of-the-game.

While geographical proximity most often is discussed in relation to dense regions, cities and clusters, an evolving stream of research emphasize the complementary role of temporary and virtual proximity. While deep relational trust mainly evolve through repeated and frequent interaction over time, temporary proximity through trade-fairs, conferences and meetings may facilitate social tie formation amongst non-collocated actors (Grabher, Citation2002; Maskell, Citation2014; Torre, Citation2008). Similarly, the role of mediated interaction and virtual communities has come into focus (Bathelt & Turi, Citation2011; Grabher & Ibert, Citation2014; Rutten, Citation2017). Over the last 150 years, technological innovations in transportation and communication have led to repeated prophesies about ‘the annihilation of space’ (e.g. the railway and telegraph in the nineteenth century) and ‘the death of distance’ (modern ICT). Whilst distance is, as of yet, not ‘dead’, new means of communication and exchange has implication for the formation of social ties. Still, however, face-to-face interaction plays an important role for social life (Larsen, Urry, & Axhausen, Citation2016; Urry, Citation2002) and virtual communities and buzz contribute to the formation of social, cognitive and cultural proximity. The role of virtual proximity and technology-mediated interaction is further discussed in relation to trust formation below.

Types of trust and its formation over time

Trust is, broadly defined, the intention to accept vulnerability based on positive expectations on the intentions or behaviour of others (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, Citation1998). For example, when actors engage in collaboration and knowledge sharing involving sensitive information. There are many facets and schools of thought within the trust literature, not least when it comes to the antecedents of trust (see e.g. Bachmann & Zaheer, Citation2006; Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Citation1995; Nilsson & Mattes, Citation2015). The different views emphasize different but interdependent aspects of trust formation (cf. Williams, Citation2001), including both calculative, knowledge-based, and identification-based trust (Lewis & Weigert, Citation1985).Footnote1

Trust is a concept applied at different levels of analysis. At the micro-level between individuals and in specific situations; at the meso-level trust in groups and organizations; and at the macro-level trust in institutions, both formal (rule and legal systems etc.) and informal (culture etc.). Complementary to this is the distinction between personal (relational) and impersonal (e.g. institutional) trust (Kroeger, Citation2017). What is of specific interest here is the interplay between different levels and forms of trust in relation to proximity. In that, a temporal dimension becomes relevant as impersonal trust in for example institutional arrangements and routines may facilitate initial trust, while trust developed as a result of interaction over time tend to be social and personal (cf. Kroeger, Citation2012). Both inter-personal trust (e.g. the level of trust a boundary spanner places on her counterpart in an organization) and inter-organizational trust (e.g. the level trust placed in the partner organization by the members of a focal organization) can be initial or gradual and are largely built on the same antecedent factors.

To capture the relationship between proximity and trust formation, a broad conceptualization of trust is needed. Such conceptualization tend to distinguish between different levels of robustness/fragility. At one end of the spectrum is so-called calculative or deterrence-based trust where deterring factors (e.g. risk of sanctions, legislation) generate trust by reducing the risk of opportunism (Williamson, Citation1993). A slightly deeper form of trust pivots on the ability of actors to understand and predict the behaviour of others (i.e. trust based on reduced information asymmetries). When the perceived ability to predict is high, uncertainties are reduced, facilitating the formation of trust between actors (McKnight, Cummings, & Chervany, Citation1998). This ability to understand and predict behaviour often traces back to perceived similarities and group belonging. Whilst these two views on trust largely holds a utilitarian or ‘functional’ view (Murphy, Citation2006) on trust (i.e. stressing reduction of information asymmetries, ability to predict, deterrence, reduction of uncertainty), in relational economic geography trust is more often seen as relational and emergent. Thirdly, the trustors’ belief in the competence and ability of the trustee as a basis for trust. Trust in an actor’s competence and ability to perform certain tasks is often, but not solely, based on previous experiences of interaction. Lastly, the deepest and most robust form of trust is considered to be that which is based on an (experience-based) belief in an actor’s intentions, integrity, benevolence, and ultimately emotional bonds of friendship and identification. As relationships evolve, actors develop stronger ties characterized by rapport, shared understanding, and emotional bonds (Bigley & Pearce, Citation1998; Kramer, Citation1999). These bases of trust are typically seen as stronger and more robust than calculative and ‘utilitarian’ trust (Ring, Citation1996).

The evolution from weak/fragile to deep/robust trust takes place over time as relationships are reinforced through exchange and experience (Mayer et al., Citation1995; Ring, Citation1996). The temporal dimension, and the distinction between initial and gradual trust, is thus central for understanding the trust formation process. The temporal dimension is also, as we shall see later, important for linking trust formation and proximity. Regional scholars typically discuss trust solely as something that is built through interaction over time. Mathews and Stokes criticize what they consider to be an implicit view that ‘ … trust is built up over time through mutual investments and adjustments except when dealing with unknown firms when trust is the default setting’ (Mathews & Stokes, Citation2013, p. 851). Only by tracing the antecedents of gradual and initial trust can the conceptual validity of such a view be assessed. provides an overview of the types of initial and gradual trust antecedents as well as the links to proximity categories.

Table 1. Overview of conceptual linkages between trust formation and proximity types.

Initial/swift trust

Initial trust (also referred to as ‘swift trust’) refers to when the trustor has little or no first-hand information about the trustee (McKnight et al., Citation1998). Initial trust is thus not based on exchange-experience but rather on assumptions and expectations that can be attributed to (i) cognitive cues and first impressions related to group belonging, (ii) to institutional factors and (iii) situational conditions.Footnote2 Initial trust is thus inherently impersonal (Becerra & Gupta, Citation1999; Shapiro, Citation1987).

Trust antecedents that are based on cognitive cues and first-impressions are largely derived from perceived group belonging; either belonging to the same social or professional group or stereotypes regarding a group’s trustworthiness. Actors who are perceived as belonging to the same community or group (be it professional, social, cultural) as the trustor tend to be considered more trustworthy (Usoro, Sharratt, Tsui, & Shekhar, Citation2007). A number of studies have found that perceived similarity is a driver of trust (Gargiulo & Ertug, Citation2006; Jones, Citation1991; Levin et al., Citation2006), either because of perceived lower uncertainties or greater ability to predict behaviour and identify with the trustee. However, trust in groups does not only refer to trust formation when actors belong to the same group but also when trustworthiness is inferred from stereotyping. Trustworthiness is then based on belonging to a trustworthy or competent group (e.g. ‘academics’, ‘doctors’) (Crisp & Jarvenpaa, Citation2013; Williams, Citation2001). Lastly, reputational inference (second-hand information) may be in the form of local buzz or word-of-mouth (Burt & Knez, Citation1995) but also from direct referrals from trusted actors (Gulati, Citation1998).

In addition to cognitive cues, initial trust formation is also closely linked to situational conditions and institutional factors that reduce uncertainty and facilitate communication (Bachmann & Inkpen, Citation2011; Nooteboom, Citation2006). The literature presents two dimensions of institutional and situational trust. One has to do with situational normality/similarity (i.e. a belief that exchange will be successful because the situation is normal/familiar), and the other having to do with structural assurances (i.e. belief that the exchange will be successful because of the existence of favourable contextual conditions such as promises, contracts, regulations and guarantees) (McKnight et al., Citation1998). A shared institutional context and institutional deterrence effects – enforced rules of the game as well as shared culture, norms and codes of conduct – facilitate trust creation by making situational and contextual conditions explicit, transparent and reliable for the actors involved (Möllering, Citation2006; Shapiro, Citation1987; Zucker, Citation1986). Situational conditions are however not limited to institutional factors and deterrence. Other situational conditions such as perceived shared interests and ease of communication are also considered facilitative for trust formation.

Gradual trust

Regional scholars tend to focus on how trust is formed through repeated face-to-face interaction amongst collocated actors. Once actors have initiated a relationship, trust evolves, either by growing stronger (Becerra & Gupta, Citation2003; Gulati & Sytch, Citation2008) or deteriorating as first-hand experiences gives insights about the trustee’s competence, reliability and/or integrity (Jones & George, Citation1998). Situational and institutional factors, inferences from group belonging, and deterrence effects are replaced by first-hand experience. In other words, personal trust supplants impersonal trust.

At a general level, gradual trust formation is influenced by three aspects of the social exchange: (i) the length of the relationship, (ii) the frequency of interaction, and (iii) the type of interaction (cf. Granovetter, Citation1983). Regarding the latter, a number of studies find that face-to-face interaction is superior to other forms of exchange (e.g. technology-mediated/virtual communication) when it comes to enabling trust (Jarvenpaa & Leidner, Citation1999; Nilsson & Mattes, Citation2015; Nohria & Eccles, Citation1992; Shapiro, Sheppard, & Cheraskin, Citation1992). In particular, when the focus of the relationship is to share complex knowledge with a large tacit component (Becerra, Lunnan, & Huemer, Citation2008; Jones, Hesterly, & Borgatti, Citation1997). The rationale explaining how the type of interaction shapes trust formation partially links up with the theory of cues-filtered-out and social information processing where communication without nonverbal cues is discussed and problematized (Walther, Citation1995). In particular the way in which direct and mediated interaction differ in terms of quality and content; i.e. how direct social interaction conveys vastly more information than for example technology-mediated communication (Wilson, Straus, & McEvily, Citation2006). Trust research has built on this to problematize how trust is formed in face-to-face versus mediated settings. Studies show that computer-mediated exchange share information much slower than face-to-face exchange (cf. Naquin & Paulson, Citation2003; Wilson et al., Citation2006). Since face-to-face interaction enables exchange of greater amount of social information, gradual trust is developed more easily and rapidly in face-to-face exchange.

Two bases for gradual trust has been identified. Firstly, gradually evolving rational expectations regarding the ability, capacity, intention and motive of the trustee (Kramer, Citation1999; Shapiro et al., Citation1992). This is referred to as cognition-based gradual trust; i.e. rational expectations as to the trustee’s competence, reliability and integrity (McAllister, Citation1995). Secondly, as actors interact over time mutual empathy and identification develop. This form of affect-based gradual trust is based on emotional bonds of empathy and identification between actors (Bigley & Pearce, Citation1998; Droege et al., Citation2003).

The way trust is formed has implications for the strength/resilience of trust. Gradual trust that has been developed through repeated first-hand interaction over time is considered ‘deeper’, ‘thicker’ and more resilient than initial trust which is built on deterrence and perceived similarities (Droege et al., Citation2003; McKnight & Chervany, Citation2006; Molm, Schaefer, & Collett, Citation2009; Zaheer, Albert, & Zaheer, Citation1999). Fragile calculus-based trust may, however, evolve into knowledge-based trust and ultimately identification-based deep trust over time (McEvily, Perrone, & Zaheer, Citation2003).

Discussion: proximity and the trust formation process

This section draws together the literatures on proximity and trust formation based on the five types of proximity (cognitive, institutional, cultural, social, and geographical) that are central for understanding regional learning and knowledge dynamics. This means that the linkages to initial and gradual trust is depicted from the vantage point of the five proximity types (in above, the conceptual linkages between trust formation and proximity are summarized from the point-of-view of the bases of trust). The three first types – cognitive, institutional, and cultural – are mainly related to initial trust antecedents and the formation of impersonal trust as they do not depend on social exchange. While there are complex interdependencies between initial and gradual trust formation and the different types of proximity, the aim here is to disentangle these interdependencies and provide insights into how proximity relates to the formation of trust (for example Rutten, Citation2017 stress the importance of distinguishing between micro-level (social networks) and marco-level (e.g. institutions) social dynamics and to identify their connection to ‘proximities’).

Social proximity has conceptual linkages to both initial and gradual trust antecedents. Interestingly, geographical proximity has the weakest conceptual links to the antecedents for trust formation. Collocated actors, without cultural, social, institutional or cognitive proximity are arguably not more likely to develop trust. However, as argued above, geographical proximity is intimately related to social proximity as it is facilitative for frequent and repeated fact-to-face interaction. Geographical proximity thus has strong indirect conceptual linkages to gradual trust formation. To help understand these linkages, stylized illustrations are provided for each type of proximity. are meant to illustrate conceptual relationships (i.e. relationships postulated in the trust and proximity literatures) of influence between different types of proximity and trust. In doing so, it is necessary to distinguish between the different antecedents of initial and gradual trust formation. The linkages illustrated in are not to be seen as necessary or sufficient for trust formation, but rather as facilitating conditions – e.g. that geographical proximity facilitates or increases the likeliness of direct face-to-face interaction, which in turn is an antecedent to gradual trust formation. Gradual trust may, however, arise without any geographical proximity and there can be trust without geographical proximity.

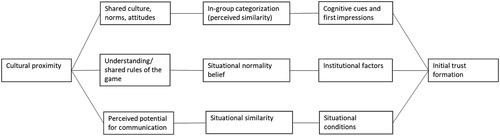

Figure 1. Conceptual linkages between cognitive proximity and initial trust formation. In –5 different forms of proximity has been taken as the starting point with the attempt to sketch the (stylized) conceptual linkages between proximity and trust formation.

Cognitive proximity and trust formation

Cognitive proximity pivots on shared a knowledge base and similar experiences. It is conceptually linked to several antecedents for initial trust formation: cognitive cues as well as institutional and situational conditions (). In terms of cognitive cues, cognitive proximity infers a perception of similarity by belonging to the same community and sharing knowledge base. Simply put, an actor is more likely to perceive cognitively proximate actors as more similar (and thereby more trustworthy) than cognitively distant actors. For example when belonging to a community of practice.

In terms of situational and institutional trust antecedents, cognitive proximity signals normality and similarity in exchange situations. The perception of a similar/shared understanding of the exchange situation and the rules-of-the-game is expected by the actors to result in easier, less uncertain and therefore more successful exchange and communication. Exchange between actors with similar knowledge bases and experiences is thus perceived as an indication of situational and institutional similarity – an antecedent for initial trust.

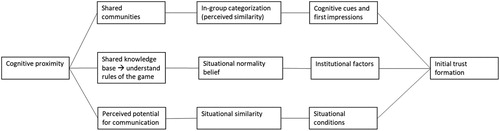

Institutional proximity and trust formation

Institutional proximity refers to understanding the rules-of-the-game in terms of the ways of doing business and collaborating as well as familiarity with and trust in regulations and professional norms. There is a clear link to institutional trust based on situational normality beliefs – i.e. trust in the system based on familiarity with the rules-of-the-game (). Such perceived familiarity reduces uncertainty and the perceived risk of opportunism. Even in the absence of previous exchange, familiarity with and trust in the institutional setting in which situations of exchange takes place thus entail higher levels of initial trust.Footnote3

Cultural proximity and trust formation

Cultural proximity refers to having a shared language, codes and norms of communication. As with cognitive proximity, cultural proximity is related to both cognitive cues, institutional and situational conditions (). In this case, cognitive cues refer to in-group categorizations based on cultural groups rather than shared communities, i.e. when actors are perceived to share culture, norms and attitudes. A reason for this is that individuals more fluently can perceive and interpret trust-relevant signals, symbols and patterns within our own cultural sphere (Child & Möllering, Citation2003). This reduces the perceived uncertainty in the exchange situation as actors are familiar with the format of exchange and as it facilitates communication between the involved actors. This is facilitative for both situation-based and institutional trust formation.

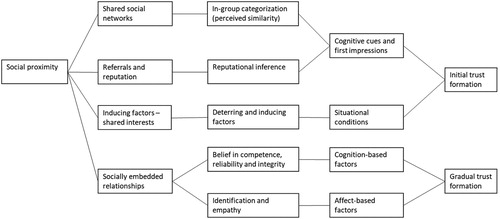

Social proximity and trust formation

Social proximity mainly refers to having experience from prior exchange and is thus a precondition for gradual trust formation (). As it is defined in terms of socially embedded direct relations between actors, social proximity contributes to both cognition-based (rational) and affect-based gradual trust formation. As actors interact over time, both rational belief in the competence, reliability, and integrity of actors and identification with and empathy for the other party may develop.

However, even in the absence of prior interaction, indirect social proximity in the form of belonging to the same social or professional network may facilitate the formation of initial trust. Actors tend to be considered as more trustworthy because of perceived similarities when belonging to the same social network as the trustor (in-group categorization). Furthermore, social networks also provide an opportunity for actors to gain third-party referrals about potential collaborators (reputational inference). Thirdly, social proximity may also affect initial trust formation by means of situational deterrence effects. When actors belong to the same social network, malicious exchange-behaviour may lead to more severe social sanctions. Therefore, such an exchange-situation involves less risk of opportunistic behaviour and thereby reduces uncertainty (i.e. deterrence-based trust).

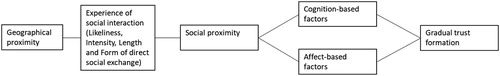

Geographical proximity and trust formation

When it comes to initial trust formation, geographical proximity has at best an indirect influence as it is correlated with other forms of proximity (cultural, institutional etc.) that influence initial-trust formation. For example, because collocation increases the likelihood of interaction, the probability of social proximity and belonging to the same social networks increases. Similarly, collocation infers a greater probability of cultural proximity as norms, values and culture often is created, shared, and reified amongst collocated actors (in cities, regions and even nations). In that sense, geographical proximity may be seen as a basis for in-group categorization. Culture can however by no means be reduced to geography. Organizations as well as social and professional communities may (and often strives to) develop their own norms, value-system and worldviews across space.

These indirect relationships between geographical proximity and initial trust should thus be acknowledged but also drawn upon carefully. The fact that different proximity types are interrelated and mutually reinforcing applies to not only geographical proximity but also other forms. Reducing initial trust formation to geographical proximity by a reductionist approach where other forms of proximity are seen as vehicles activated by geographical proximity is highly problematic. However, disentangling the roles of different proximity types in trust formation enables a fuller understanding of the role of collocation. It also points to the risk of over-regionalization: What is ascribed to collocation is in many instances better understood in terms of social, cognitive and institutional proximity.

If overemphasizing the role of geographical proximity in initial trust formation can be criticized from the point of view of trust literature, gradual trust formation is more directly related to geographical proximity. A key reason as to why regional scholars consider collocation facilitative for knowledge transfer and localized learning is that collocated actors are more likely to interact, do so more frequently, and to a higher extent through face-to-face. Gradual interpersonal and inter-organizational trust is based on experience of interacting and formed when there is repeated and frequent exchange with a high social and relational content, as with face-to-face exchange. Geographical proximity is therefore conducive for gradual trust formation. illustrates the conceptual relationship between geographical proximity and gradual trust formation.

A stylized example can illustrate the relationship between geographical proximity and gradual trust formation. A firm located in a cluster where there is a high presence of related and unrelated actors (suppliers, customers, competitors, research institutes etc.) is more likely to encounter and have direct and repeated face-to-face exchange with such actors, purposeful or haphazard. Geographical proximity is thus related to the formation of social ties (social proximity) which over time lead to formation of gradual trust or distrust.

Collocation may also be conducive for other forms of proximity. Importantly, the frequent and repeated direct exchange that is more likely in dense regions may contribute to social, cognitive, cultural and even institutional proximity. This means that the direct exchange that takes place within a cluster of collocated firms, leads to or reinforces social and professional relationships (fostering social proximity); shared understanding and common frameworks (fostering cognitive proximity); common culture and values (fostering cultural proximity); and institutional context (fostering institutional proximity). This illustrates the interrelationships between different forms of proximity and the need for disentangling these in relation to trust formation.

While direct exchange between collocated actors may contribute to other forms of proximity, gradually developed deep trust based on direct exchange is also argued to substitute for geographical proximity (cf. Nilsson & Mattes, Citation2015):

A higher level of trust and, more widely, an increased ability to collaborate, enables one to operate at a larger cognitive distance and thereby generate more innovative potential. That is, I think, the crux of the relation between trust and innovation. (Nooteboom, Citation2013, p. 108)

Concluding discussion and avenues for future research

Within regional studies and relational geography in particular, collocation is associated with tacit knowledge transfer. A key explanation for this is that proximity fosters mutual trust. While the trust literature lends credence to such a view, this paper shows that the relationship between proximity and trust formation goes well beyond deep trust formation based on face-to-face exchange. A more nuanced relationship between proximity and swift (impersonal) and gradual (personal) trust formation has been laid out.

Explicating the conceptual relationships between proximity and swift trust formation adds new insights into regional studies. Gertler (Citation2003) argues that the role of trust is greatest when it comes to influencing an actor’s decision on whether or not to share sensitive explicit knowledge to ‘strangers’, capturing the importance of initial trust/distrust. Initial trust formation largely pivots on perceived similarity/closeness in terms of norms, practices, attitudes (informal institutions); culture; social networks (embedded social relations); and communities (shared knowledge base and cognitive frameworks). This provides cognitive cues as well as perceived situational and institutional normality, which is drawn upon by actors to determine whether or not to trust an actor with whom there is no previous relationship. Initial trust is thus impersonal.

When it comes to geographical proximity, it is in itself not internally related to initial trust formation. It is, however, facilitative for gradual deep trust formation as it enables frequent and repeated face-to-face. While gradual trust is not inherently local or dependent on collocation, it is dependent on repeated social exchange over time. Furthermore, the speed at which gradual trust is developed depends on the social content of the exchange, which in turn is facilitated by collocation. The conclusion from this is that building deep personal trust across distance is by no means impossible but involves greater investments in time and effort, typically by temporary collocation – c.f. the global pipelines analogy (Bathelt, Malmberg, & Maskell, Citation2004; Maskell, Citation2014). Importantly, once deep trust has been developed, it is relatively robust over time and reduce the importance of permanent collocation (Nilsson & Mattes, Citation2015).

While the account in this paper mainly pivots on the positive/virtuous aspects of trust, this bias is mainly upheld for the sake of clarity. While echoing the same positive view on trust as is often found in relational economic geography, one should be careful not to overemphasize the virtuous nature of trust relationships (Sayer, Citation2002; Staber, Citation2007). The aim here is not to establish trust as an all-encompassing solution to problems of transaction and knowledge exchange but rather to draw on ‘proximity’ to conceptually anchor trust formation in a regional setting. While the discussion above focuses on the formation of trust, it is equally important to acknowledge that proximity may contribute to distrust and dissolution of trust and that this not should be seen as inherently negative.

As argued by Staber (Citation2007) both trust and distrust help to reduce uncertainty in situations of risk but they do so by different means. In terms of initial distrust, reputational inference and third-party referrals may help actors avoid entering into relationships with untrustworthy or otherwise unsuitable counterparts. Similarly, when situational and institutional factors appear unfavourable, the rational choice may be to avoid forming a relationship and engage in knowledge exchange.

Having said this, there is also a ‘dark side of trust’. For example when perceived differences (in terms of in-group categorizations and stereotyping) lead to actors not engaging because of irrational and unsound perceptions about the trustee. For example, if actors engage in knowledge exchange relationships only with those perceived to be similar to the trustor – i.e. when cultural, cognitive and social proximity is high – the potential for new insights and exploration of new ideas are significantly lower because of functional, cognitive, and political lock-in and inertia (Grabher, Citation1993; Nooteboom, Citation2000).

In the context of experience-based gradual trust formation, trust may also dissolve as actors get experience of interacting. Again, such dissolution of trust is not inherently negative. Rational grounds for dissolving trust based on the trustee’s competence, reliability and integrity is important for avoiding unfruitful exchanges and opportunistic behaviour. Conversely, to over-invest in trust and forming strong trust-relationships that are of limited economic value to firms may result in misallocation of resources, over-exposure to risk and cognitive lock-in and groupthink which in turn lead to negative effects on innovative performance – this is one element of the so-called dark side of trust (Molina-Morales, Martínez-Fernández, & Vanina Jasmine, Citation2011; Skinner, Dietz, & Weibel, Citation2014).

This positive and negative role of trust constitute an avenue for future research into regional dynamics – especially in the context of different regional development paths. In new path formation, strong emotive personal trust and strong relational ties of deep personal trust may be an obstacle to renewal and reconfiguration of regional industrial profiles (Fazio & Lavecchia, Citation2013). As suggested above, these obstacles materialize in cognitive and relational lock-in. In new path formation, emphasis is on forming new ties and exploring less closely related avenues for regional industrial development. In this, initial trust between a broader array of actors is key as it facilitates exploration of new opportunities.

However, obstacles to new path formation may result not only from strong emotive personal trust but also from impersonal trust. For new path formation, it is necessary to form linkages and engage with actors within unrelated field (different communities, culture, institutional fields etc.). Antecedents to initial impersonal trust formation may, as argued above, inhibit this as actors tend to trust those who are perceived similar to themselves – where there is some kind of proximity. This may lead to instances of ‘false negatives’ when it comes to searching and assessing future development paths. In such situations, boundary spanners play a particularly important role.

In addition to the role of trust for regional development and path formation, a number of avenues for future research within regional studies can be identified. One such avenue is further empirical research into spatial influences on the trust formation process. This includes studies that build on existing research (Koch, Citation2018; Mathews & Stokes, Citation2013; Murphy, Citation2006; Nilsson & Mattes, Citation2013; Oba & Semerciöz, Citation2005) but adding the fundamental distinction between initial and gradual trust formation rather than focusing heavily on the role of face-to-face. This may also incorporate different levels of analysis when it comes to trust formation and resilience – i.e. interpersonal and interorganizational trust formation.

In particular, empirical studies disentangling both the social aspect of gradual trust formation, the rational/calculative dimension related to reduced information asymmetries, and the cognitive, institutional and situational dimensions central to initial trust formation would provide much-needed insights into a key mechanism of regional knowledge dynamics and learning. This should include further work on how different regional constellations influence not only trust formation but also the formation of distrust and dissolution of trust (cf. Koch, Citation2018). This would contribute to a more nuanced view on trust in regional studies. The literature on the ‘dark’ side of trust provide a fruitful starting point for this (Gargiulo & Ertug, Citation2006; Molina-Morales et al., Citation2011). As argued above, trust does not only facilitate mutual understanding, tie formation, knowledge dissemination and shared vision. It may also

… draw the focal party (whether giver or recipient) into an uncomfortable exchange dilemma from which it is difficult to extricate oneself; where the very nature of trust means that most of the options available as a response are neither viable nor attractive. (Skinner et al., Citation2014, p. 207)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Magnus Nilsson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8769-8266

Notes

1 While this section discuss the antecedents to trust formation it should be noted that the same factors may result in the dissolution of trust or distrust, which is equally important for effective interaction.

2 I exclude personality traits of the trustor as an antecedent. A general attitude – a trusting stance and faith in humanity – of the individual is not based on interaction or perception of the trustee or on institutional or situational conditions and thus has little relation to proximity.

3 Another dimension of institutional trust pivots on trust in the system that does not originate in familiarity or proximity. For example, an actor may trust the integrity and enforcement of national institutions without being familiar with them.

References

- Bachmann, R., & Inkpen, A. C. (2011). Understanding institutional-based trust building processes in inter-organizational relationships. Organization Studies, 32(2), 281–301. Retrieved from http://oss.sagepub.com/content/32/2/281.abstract doi: 10.1177/0170840610397477

- Bachmann, R., & Zaheer, A. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of trust research. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Balland, P.-A. (2012). Proximity and the evolution of collaboration networks: Evidence from research and development projects within the global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) industry. Regional Studies, 46(6), 741–756. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2010.529121

- Balland, P.-A., Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2015). Proximity and innovation: From Statics to dynamics. Regional Studies, 49(6), 907–920. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.883598

- Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. (2004). Clusters and knowledge: Local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Progress in Human Geography, 28(1), 31–56. doi: 10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

- Bathelt, H., & Turi, P. (2011). Local, global and virtual buzz: The importance of face-to-face contact in economic interaction and possibilities to go beyond. Geoforum, 42(5), 520–529. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016718511000558 doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.04.007

- Bathelt, H., & Turi, P. G. (2013). Knowledge creation and the geographies of local, global, and virtual buzz. In P. Meusburger, J. Glückler, & M. Meskioui (Eds.), Knowledge and the economy (pp. 61–78). Heidelberg: Springer.

- Becerra, M., & Gupta, A. K. (1999). Trust within the organization: Integrating the trust literature with agency theory and transaction costs economics. Public Administration Quarterly, 23(2), 177–203.

- Becerra, M., & Gupta, A. K. (2003). Perceived trustworthiness within the organization: The Moderating Impact of communication frequency on trustor and trustee effects. Organization Science, 14(1), 32–44. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.1.32.12815

- Becerra, M., Lunnan, R., & Huemer, L. (2008). Trustworthiness, risk, and the transfer of tacit and explicit knowledge between Alliance partners. The Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 691–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00766.x

- Bigley, G. A., & Pearce, J. L. (1998). Straining for shared meaning in organization science: Problems of trust and distrust. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 405–421. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/259286 doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926618

- Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A Critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74. doi: 10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2010). The spatial evolution of innovation networks: A proximity perspective. In R. Boschma & R. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 120–135). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Boschma, R. A., & Ter Wal, A. L. J. (2007). Knowledge networks and innovative performance in an industrial district: The case of a Footwear district in the South of Italy. Industry and Innovation, 14(2), 177–199. doi: 10.1080/13662710701253441

- Bouba-Olga, O., Carrincazeaux, C., Coris, M., & Ferru, M. (2015). Proximity dynamics, social networks and innovation AU – Bouba-Olga, Olivier. Regional Studies, 49(6), 901–906. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1028222

- Breschi, S., & Lissoni, F. (2009). Mobility of skilled workers and co-invention networks: An anatomy of localized knowledge flows. Journal of Economic Geography, 9(4), 439–468. Retrieved from http://joeg.oxfordjournals.org/content/9/4/439.abstract doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbp008

- Burt, R. S., & Knez, M. (1995). Kinds of third-party effects on trust. Rationality and Society, 7(3), 255–292. doi: 10.1177/1043463195007003003

- Child, J., & Möllering, G. (2003). Contextual confidence and active trust development in the Chinese business Environment. Organization Science, 14(1), 69–80. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.1.69.12813

- Crisp, C. B., & Jarvenpaa, S. L. (2013). Swift trust in global virtual teams: Trusting beliefs and normative actions. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 12(1), 45–56. doi: 10.1027/1866-5888/a000075

- Das, T. K., & Teng, B.-S. (1998). Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 491–512. doi:10.5465/amr.1998.926623

- Droege, S. B., Anderson, J. R., & Bowler, M. (2003). Trust and organizational information flow. Journal of Busines and Management, 9(1), 45–59.

- Dupuy, J.-C., & Torre, A. (1998). Cooperation and trust in spatially clustered firms. In N. Lazaric & E. Lorenz (Eds.), Trust and economic learning (pp. 141–161). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Fazio, G., & Lavecchia, L. (2013). Social capital formation across space: Proximity and trust in European regions. International Regional Science Review, 36(3), 296–321. doi: 10.1177/0160017613484928

- Gargiulo, M., & Ertug, G. (2006). The dark side of trust. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 165–186). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Gertler, M. S. (1995). “Being there”: Proximity, organization, and culture in the development and adoption of advanced manufacturing technologies. Economic Geography, 71(1), 1–26. doi: 10.2307/144433

- Gertler, M. S. (2003). Tacit knowledge and the economic geography of context, or the undefinable tacitness of being (there). Journal of Economic Geography, 3(1), 75–99. doi: 10.1093/jeg/3.1.75

- Gertler, M. S. (2004). Manufacturing culture: The institutional geography of industrial practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties. The lock-in of regional development in the Ruhr Area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The embedded firm. On the socioeconomics of industrial networks (pp. 255–277). London: Routledge.

- Grabher, G. (2002). Cool projects, Boring institutions: Temporary collaboration in social context. Regional Studies, 36(3), 205–214. doi: 10.1080/00343400220122025

- Grabher, G., & Ibert, O. (2014). Distance as asset? Knowledge collaboration in hybrid virtual communities. Journal of Economic Geography, 14(1), 97–123. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbt014

- Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233. doi: 10.2307/202051

- Gulati, R. (1998). Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19(4), 293–317. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199804)19:4<293::AID-SMJ982>3.0.CO;2-M

- Gulati, R. (2007). Managing network resources: Alliances, affiliations and other relational assets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gulati, R., & Sytch, M. (2008). Does familiarity breed trust? Revisiting the antecedents of trust. Managerial and Decision Economics, 29(2–3), 165–190. doi: 10.1002/mde.1396

- Hess, M. (2004). ‘Spatial’ relationships? Towards a reconceptualization of embeddedness. Progress in Human Geography, 28(2), 165–186. Retrieved from http://phg.sagepub.com/content/28/2/165.abstract. doi: 10.1191/0309132504ph479oa

- Huber, F. (2012). On the role and Interrelationship of spatial, social and cognitive proximity: Personal knowledge relationships of R&D workers in the Cambridge information technology cluster. Regional Studies, 46(9), 1169–1182. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2011.569539

- Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. (1999). Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Organization Science, 10(6), 791–815. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2640242 doi: 10.1287/orsc.10.6.791

- Jones, C., Hesterly, W. S., & Borgatti, S. P. (1997). A general theory of network governance: Exchange conditions and social mechanisms. The Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 911–945. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/259249 doi: 10.5465/amr.1997.9711022109

- Jones, G. R., & George, J. M. (1998). The experience and evolution of trust: Implications for cooperation and teamwork. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 531–546. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926625

- Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. The Academy of Managment Review, 16(2), 366–395. doi: 10.5465/amr.1991.4278958

- Knoben, J., & Oerlemans, L. A. G. (2006). Proximity and inter-organizational collaboration: A literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8(2), 71–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2006.00121.x

- Koch, K. (2018). The spatiality of trust in EU external cross-border cooperation. European Planning Studies, 26(3), 591–610. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1393502

- Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 569–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.569

- Kroeger, F. (2012). Trusting organizations: The institutionalization of trust in interorganizational relationships. Organization, 19(6), 743–763. doi: 10.1177/1350508411420900

- Kroeger, F. (2017). Facework: Creating trust in systems, institutions and organisations. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 41(2), 487–514. doi: 10.1093/cje/bew038

- Lagendijk, A., & Lorentzen, A. (2007). Proximity, knowledge and innovation in peripheral regions. On the Intersection between geographical and organizational proximity. European Planning Studies, 15(4), 457–466. doi: 10.1080/09654310601133260

- Larsen, J., Urry, J., & Axhausen, K. (2016). Mobilities, networks, geographies. New York: Routledge.

- Levin, D. Z., Whitener, E. M., & Cross, R. (2006). Perceived trustworthiness of knowledge Sources: The moderating impact of relationship length. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1163–1171. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1163

- Lewis, J. D., & Weigert, A. (1985). Trust as a social reality. Social Forces, 63(4), 967–985. Retrieved from http://sf.oxfordjournals.org/content/63/4/967.abstract. doi: 10.1093/sf/63.4.967

- Lorentzen, A. (2008). Knowledge networks in local and global space. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 20(6), 533–545. doi: 10.1080/08985620802462124

- Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. (2006). Localized learning revisited. Growth & Change, 37(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2257.2006.00302.x

- Maskell, P. (2001). Towards a knowledge-based theory of the geographical cluster. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(4), 921–943. doi: 10.1093/icc/10.4.921

- Maskell, P. (2014). Accessing remote knowledge—the roles of trade fairs, pipelines, crowdsourcing and listening posts. Journal of Economic Geography. Retrieved from http://joeg.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/02/18/jeg.lbu002.abstract. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbu002

- Mathews, M., & Stokes, P. (2013). The creation of trust: The interplay of rationality, institutions and exchange. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(9–10), 845–866. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2013.845695

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, D. F. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. doi: 10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

- McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. The Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/256727

- McEvily, B., Perrone, V., & Zaheer, A. (2003). Trust as an organizing principle. Organization Science, 14(1), 91–103. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.1.91.12814

- McKnight, D. H., & Chervany, N. L. (2006). Reflections on an initial trust-building model. In R. Bachmann & Z. Akbar (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 29–51). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- McKnight, D. H., Cummings, L. L., & Chervany, N. L. (1998). Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 473–490. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926622

- Molina-Morales, F. X., López-Navarro, M. Á., & Guia-Julve, J. (2002). The role of local institutions as intermediary agents in the industrial district. European Urban and Regional Studies, 9(4), 315–329. doi: 10.1177/096977640200900403

- Molina-Morales, X. F., Martínez-Fernández, T. M., & Vanina Jasmine, T. (2011). The dark side of trust: The benefits, costs and optimal levels of trust for innovation performance. Long Range Planning, 44(2), 118–133. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0024630111000033 doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2011.01.001

- Möllering, G. (2006). Trust, institutions, agency: Towards a neoinstitutional theory of trust. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 355–376). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Molm, L. D., Schaefer, D. R., & Collett, J. L. (2009). Fragile and resilient trust: Risk and uncertainty in negotiated and reciprocal exchange*. Sociological Theory, 27(1), 1–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.00336.x

- Morrison, A., Rabellotti, R., & Zirulia, L. (2013). When do global pipelines enhance the diffusion of knowledge in clusters? Economic Geography, 89(1), 77–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2012.01167.x

- Murphy, J. T. (2006). Building trust in economic space. Progress in Human Geography, 30(4), 427–450. Retrieved from http://phg.sagepub.com/content/30/4/427.abstract. doi: 10.1191/0309132506ph617oa

- Naquin, C. E., & Paulson, G. D. (2003). Online bargaining and interpersonal trust. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 113–120. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.113

- Nilsson, M., & Mattes, J. (2013). Spatiality and trust: Antecedents of trust and the role of face-to-face contacts. CIRCLE Electronic Working Paper Series, 2013/16.

- Nilsson, M., & Mattes, J. (2015). The spatiality of trust: Factors influencing the creation of trust and the role of face-to-face contacts. European Management Journal, 33(4), 230–244. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2015.01.002

- Nohria, N., & Eccles, R. G. (1992). Face-to-face: Making network organizations work. In N. Nohria & R. G. Eccles (Eds.), Networks and organizations: Structure, form, and action (pp. 288–308). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Nooteboom, B. (2000). Learning by interaction: Absorptive capacity, cognitive distance and governance. Journal of Management and Governance, 4(1), 69–92. doi: 10.1023/a:1009941416749

- Nooteboom, B. (2006). Forms, sources and processes of trust. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research (pp. 247–263). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Nooteboom, B. (2013). Trust and innovation. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of advances in trust research (pp. 106–122). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oba, B., & Semerciöz, F. (2005). Antecedents of trust in industrial districts: An empirical analysis of inter-firm relations in a Turkish industrial district. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 17(3), 163–182. doi: 10.1080/08985620500102964

- Powell, W. W., Koput, K. W., Bowie, J. I., & Smith-Doerr, L. (2002). The spatial clustering of science and capital: Accounting for biotech firm-venture capital relationships. Regional Studies, 36(3), 291–305. doi: 10.1080/00343400220122089

- Ring, P. S. (1996). Fragile and resilient trust and their roles in economic exchange. Business & Society, 35(2), 148–175. Retrieved from http://bas.sagepub.com/content/35/2/148.abstract doi: 10.1177/000765039603500202

- Ring, P. S., & Van de Ven, A. H. (1992). Structuring cooperative relationships between organizations. Strategic Management Journal, 13(7), 483–498. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250130702

- Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926617

- Rutten, R. (2017). Beyond proximities: The socio-spatial dynamics of knowledge creation. Progress in Human Geography, 41(2), 159–177. doi: 10.1177/0309132516629003

- Sayer, A. (2002). Markets, embededdness and trust: Problems of polysemy and idealism. In S. Metcalf & A. Warde (Eds.), Market relations and the competitive process (pp. 41–57). Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Shapiro, D. L., Sheppard, B. H., & Cheraskin, L. (1992). Business on a handshake. Negotiation Journal, 8(4), 365–377. doi: 10.1007/bf01000396

- Shapiro, S. P. (1987). The social control of impersonal trust. American Journal of Sociology, 93(3), 623–658. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780293 doi: 10.1086/228791

- Skinner, D., Dietz, G., & Weibel, A. (2014). The dark side of trust: When trust becomes a ‘poisoned chalice’. Organization, 21(2), 206–224. doi: 10.1177/1350508412473866

- Staber, U. D. O. (2007). A matter of distrust: Explaining the persistence of dysfunctional beliefs in regional clusters. Growth and Change, 38(3), 341–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2257.2007.00374.x

- Storper, M., & Venables, A. J. (2004). Buzz: Face-to-face contact and the urban economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 4(4), 351–370. doi: 10.1093/jnlecg/lbh027

- Sunley, P. (2008). Relational economic geography: A partial understanding or a new paradigm? Economic Geography, 84(1), 1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2008.tb00389.x

- Torre, A. (2008). On the role played by temporary geographical proximity in knowledge transmission. Regional Studies, 42(6), 869–889. doi: 10.1080/00343400801922814

- Torre, A., & Rallet, A. (2005). Proximity and localization. Regional Studies, 39(1), 47–59. doi: 10.1080/0034340052000320842

- Urry, J. (2002). Mobility and proximity. Sociology, 36(2), 255–274. doi: 10.1177/0038038502036002002

- Usoro, A., Sharratt, M. W., Tsui, E., & Shekhar, S. (2007). Trust as an antecedent to knowledge sharing in virtual communities of practice. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 5(3), 199–212. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.kmrp.8500143

- Walther, J. B. (1995). Relational aspects of computer-mediated communication: Experimental observations over time. Organization Science, 6(2), 186–203. doi: 10.1287/orsc.6.2.186

- Williams, M. (2001). In whom we trust: Group membership as an affective context for trust development. The Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 377–396. doi: 10.2307/259183

- Williamson, O. E. (1993). Calculativeness, trust, and economic organization. Journal of Law and Economics, 36(1), 453–486. doi: 10.1086/467284

- Wilson, J. M., Straus, S. G., & McEvily, B. (2006). All in due time: The development of trust in computer-mediated and face-to-face teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99(1), 16–33. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.08.001

- Zaheer, S., Albert, S., & Zaheer, A. (1999). Time scales and organizational theory. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 725–741. doi: 10.5465/amr.1999.2553250

- Zucker, L. G. (1986). Production of trust: Institutional sources of economic structure, 1840–1920. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (Vol. 8, pp. 53–111). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.