?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Related variety of economic activities is widely recognized to induce regional development; however, it is not clear how this mechanism takes place in regions that go through major structural and institutional transformation. Furthermore, foreign direct investment (FDI) is typically a major source of structural change in these areas; and we still need a better understanding on how foreign-owned (foreign) firms affect the dynamics of domestic-owned (domestic) companies. For these reasons we analyse firm-level exit in Hungarian city regions between 1996 and 2011, over the late post-socialist transition in manufacturing industries, focusing on the difference between foreign and domestic firms. Introducing ownership into the related variety calculation, we estimate the probability of firm exit with the region-level related variety calculated separately for foreign and domestic firms. Our results suggest that related variety of foreign firms decreases the probability of domestic firm exit earlier during the economic transition compared to the related variety of domestic firms. This finding supports the idea that FDI plays a formative role in regions under transition, and shows that domestic firms benefit from being in agglomerations where foreign firms are technologically related to each other.

1. Introduction

The argument that technological relatedness influences regional economic development through learning and capacity building has been at the core of recent discussion in economic geography (Zhu, Jin, & He, Citation2019). Extending on the literature of agglomeration economies (Beaudry & Schiffauerova, Citation2009; Duranton & Puga, Citation2004; Glaeser, Kallal, Scheinkman, & Shleifer, Citation1992; Henderson, Kuncoro, & Turner, Citation1995; Jacobs, Citation1969; Marshall, Citation1920), the central tenet claims that the related variety of economic activities in a region is crucial for economic performance because it improves local learning and boosts agglomeration externalities (Boschma & Iammarino, Citation2009; Frenken, van Oort, & Verburg, Citation2007). A vast body of empirical results supports these claims, showing that related variety is beneficial for economic growth (for an overview, see Content & Frenken, Citation2016) and diversification (Hidalgo et al., Citation2018), and there is some evidence showing that related variety enhances the chances of firm survival as well (Basile, Pittiglio, & Reganati, Citation2017; Howell, He, Yang, & Fand, Citation2018; Neffke, Henning, & Boschma, Citation2012).

All the while, there has been a growing interest in understanding the role of relatedness in regional economies that went through rapid and radical structural and institutional transformation (Gao, Jun, Pentland, Zhou, & Hidalgo, Citation2017). This is perhaps because these rapid changes – in the last decades in China or after 1990 in Central- and Eastern Europe (CEE) – provide the opportunity to understand the above mechanisms in a context similar to natural experiments (Jun, Pinheiro, Buchmann, Yi, & Hidalgo, Citation2017). As previous evidence show for Hungarian regions, firm populations went through large fluctuations during these changing times making some regions decline and others grow (Lengyel, Vas, Szakálné Kanó & Lengyel, Citation2017). Despite these recent efforts our understanding is still scanty on how agglomeration economies in general, and related variety in particular are associated with firm survival during economic transformation.

Multinational enterprises (MNEs) and foreign direct investment (FDI) are major sources for regional transformation (Pavlínek, Citation2004; Radosevic, Citation2002), because such foreign-owned (foreign) firms connect regions to global markets (Keller & Yeaple, Citation2009), and influence the productivity and innovation of co-located domestic-owned (domestic) firms of the host economy through spillover effects (Békés, Kleinert, & Toubal, Citation2009; Crescenzi, Gagliardi, & Iammarino, Citation2015; Csáfordi, Lőrincz, Lengyel, & Kiss, Citation2018; Gorg & Strobl, Citation2001). A recent study, building on the structural change framework developed by Neffke, Hartog, Boschma, and Henning (Citation2018), has found that foreign firms drive transitioning regions into unrelated diversification (Elekes, Boschma, & Lengyel, Citation2019), perhaps by bringing new knowledge into the region and dismantling old-fashioned capacities. What needs to be unpacked in this regard is the relative importance of related variety among foreign and domestic firms for firm survival as economic transition unfolds.

For these reasons, the aim of this paper is to explore how the related variety of foreign firms and the host economy relates to firm survival in regions that went through major structural and institutional transformation. We achieve this through studying the case of manufacturing firm population dynamics in Hungarian city regions between 1996 and 2011. We propose that the case is well suited for observing the interplay of technological relatedness and MNEs in regions under transition because Hungary, like many other former Eastern Block countries, went through a major transformation from a planned to a market economy beginning in the early 1990s. Previous research indeed showed that those regions succeeded in tackling the challenges of the market economy where foreign firms located their subsidiaries and re-organized the economic structure of regions (Lengyel & Leydesdorff, Citation2011), and the majority of those regions that could not attract FDI, failed (Lengyel & Szakálné Kanó, Citation2014).

For the empirical analysis we rely upon a unique firm-level panel database, in which the location of the company seat, industry classification of the main activity, size and ownership structure of companies are pulled together with key balance sheets variables. We opt for a firm level panel logit model to link firm exit to various measures of variety over the period of 1996–2011, while also controlling for other sources of agglomeration economies. Variety measures are interacted with time dummies to enable us to detect the changing importance of related variety over time. This method also provides a fine-grained picture in which firm-level controls can be accounted for.

The results of our investigation show evidence for transition patterns, especially when looking at the interplay between foreign and domestic firms. Our results indicate that the related variety of domestic firms’ industries became linked to firm survival gradually, only at a later phase of the transition. The related variety of foreign firms’ industries has started to help firm survival earlier than the related variety among domestic firms. This points towards that FDI and MNEs were transformative actors for the host regions in the earlier stages of the economic transition.

With this research, we hope to make the following contributions. First, we introduce foreign versus domestic ownership into related variety calculation, which is a new methodological development. Second, we bring the literatures of evolutionary economic geography (EEG) and MNEs closer together by putting foreign firms as key actors of economic transition into the centre of this analysis. Third, we contribute to the EEG literature by showing that the effect of related variety can change over turbulent times of economic transition, and specificities of regional transformation like the strengthening role of FDI may drive these changes.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 the literatures on related variety, and MNEs are connected, and the empirical context of our case is introduced. This is followed by the description of the data, our methodological development and the panel logit model specification in Section 3. In Section 4 the results on the relationship between firm exit as the dependent variable and regional level relatedness measures as the independent variables are presented. A discussion of our key findings, limitations and opportunities for further research conclude the paper in Section 5.

2. Conceptual and contextual background

2.1. Agglomeration externalities and firm survival

It is widely accepted that costs and benefits arise from the spatial concentration of economic activities. These agglomeration externalities influencing firm performance and regional outcomes have been undoubtedly the dominant way of understanding unequal spatial development (Duranton & Puga, Citation2004). Besides internal economies of scale, co-locating firms in similar industries benefit first from localization economies stemming from specialized local labour market, specialized local value-chains and intra-industry knowledge spillovers (Marshall, Citation1920). Specialization permits better matching between employers and employees, more efficient sharing of intermediate goods, and technological learning (Duranton & Puga, Citation2004). Second, Jacobs-externalities arise due to inter-industry knowledge spillovers stemming from the variety of economic activities present in a region (Jacobs, Citation1969). Numerous empirical findings led to a long-standing debate on the relative importance of specialization and diversity in regional growth (Glaeser et al., Citation1992; Henderson et al., Citation1995). Third, urbanization economies are present in large urban areas with a significant market size, economies of scale in public services and advanced infrastructure, offering benefits to all firms regardless of industry (McCann, Citation2008).

This discussion was furthered by the seminal work of Frenken et al. (Citation2007) on related variety. They showed that Jacobs-externalities can be expected when there is neither too strong, nor too weak technological proximity between industries within the same region, as such optimal proximity allows for effective learning and innovation (Boschma, Citation2005). Unrelated variety in contrast offers a portfolio effect for regions against economic shocks (Frenken et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, they demonstrated that localization economies are contributing mainly to productivity growth. A growing number of papers have confirmed and extended on the findings on related variety (for an overview see Content & Frenken, Citation2016).

These agglomeration forces also influence the survival of firms and the industrial composition of regions. Regional characteristics like the number of new businesses in the relevant regional market or the size of the region have a pronounced effect on new firm survival (Falck, Citation2007). Contradicting empirical evidence shows that localization economies can be both beneficial (Basile et al., Citation2017; Howell et al., Citation2018), and adverse (Boschma & Wenting, Citation2007; Borggren, Eriksson, & Lindgren, Citation2016) to firm survival. This may be because the local concentration of similar activities incentivises further entry, but also increases competition. Evidence on urbanization economies mostly indicates no link to firm survival (Basile et al., Citation2017; Boschma & Wenting, Citation2007), or a negative effect on it (Howell et al., Citation2018; Neffke et al., Citation2012). In contrast to these findings the effect of related variety (Basile et al., Citation2017; Howell et al., Citation2018), the local concentration of related industries (Boschma & Wenting, Citation2007; Neffke et al., Citation2012), or locally available workforce from related industries (Borggren et al., Citation2016; Jara-Figueroa, Jun, Glaeser, & Hidalgo, Citation2018), show a positive relationship to firm survival in many different empirical settings. Finally, the effect of unrelated variety of industries also proves to be hard to disentangle as it was found to decrease the chance of survival in general (Howell et al., Citation2018), and to increase the likelihood of survival in service (Basile et al., Citation2017), and low-tech industries in particular (Cainelli, Montresor, & Marzetti, Citation2014).

2.2. Multinational enterprises and related variety

What is missing from the above stream of studies is making a distinction between multinational enterprises (MNEs) and the host economy when measuring related variety, as it's widely documented benefits may not be straightforward to be obtained when industries are populated by a mixture of MNEs and domestic firms. This is an important extension of the literature because the role of MNEs in regional development has gained considerable attention in the last few decades (Iammarino & McCann, Citation2013). Besides the location behaviour (Barrel & Pain, Citation1999; Cantwell, Citation2009; Ledyaeva, Citation2009) and speed of local embedding of MNEs (Lorenzen & Mahnke, Citation2002), the spatial effects of foreign firms are frequently analysed and the exact mechanisms are still in question (Beugelsdijk, McCann, & Mudambi, Citation2010; Cantwell & Iammarino, Citation2000; Christopherson & Clark, Citation2007; Phelps, Citation2004, Citation2008; Young, Hood, & Peters, Citation1994).

Capello (Citation2009) argues for various channels of spillovers from MNEs to co-located domestic firms, and proposes a cognitive approach to capture them. According to her arguments, the productivity of domestic firms can be enhanced by MNEs even at low levels of labour flows and value chain links because the presence of MNEs can change the attitude of domestic companies towards cooperation and novelties. FDI inflows also contribute to the upgrading of indigenous capabilities of local firms, making them gradually switch to more complex products (Javorcik, Lo Turco, & Maggioni, Citation2017). What previous evidence shows is that new knowledge brought in by MNEs will not automatically benefit local firms. The spillover effect of FDI on the host economy depends on the absorptive capacity and dynamic capabilities of local firms (Cantwell & Iammarino, Citation2003; Teece & Pisano, Citation1994), and the degree of fit between the characteristics of the MNE and the host region (Crescenzi et al., Citation2015; Delios, Xu, & Beamish, Citation2008; Iammarino & McCann, Citation2013;).

We expect, based on the literature above, that related variety in particular is associated with a decreased chance of exit, and we aim to explore the differential role of related variety within the foreign and domestic subset of firms. In connection with the transformative role that MNEs may play in structural change, we also expect that the related variety of foreign firms’ industries in particular is mitigating the chance of exit even for domestic firms.

2.3. The changing role of related variety in regions under transition

A further point that still needs to be explored in the literature is that the link between related variety and firm survival may change over time, especially in regions under economic or institutional transition. The emergence of agglomeration economies is a cumulative process, as it was proposed earlier by Myrdal (Citation1957), thus a firm is likely to enter a region where agglomeration economies are already present and the new entry will further increase agglomeration economies. Evidence show that agglomeration externalities indeed change over time (Almeida & Kogut, Citation1997; Duranton & Puga, Citation2001; Neffke, Henning, Boschma, Lundquist, & Olander, Citation2011). Consequently, the potential for knowledge spillovers increases with newly entering firms (Arthur, Citation1990), which is especially the case when entries increase the level of technological relatedness in the region because firms are more likely to absorb these knowledge spillovers (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990). Related variety is aiming to capture the level of potential knowledge spillovers in a region (Boschma & Iammarino, Citation2009; Frenken et al., Citation2007), and consequently, firms are expected to locate in regions with a high potential of knowledge spillovers (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2006). Furthermore, the level of technological relatedness among co-located firms correlates with the level of intermediate goods and services in the region (Cainelli & Iacobucci, Citation2012), which suggest that different sources of agglomeration economies might co-evolve.

What follows from this is that the effect of related variety can change over time. This is because firms related to the regional portfolio have a higher chance to enter the region compared to unrelated firms (Neffke, Henning, & Boschma, Citation2011), and therefore new firms can be expected to increase related variety in regions. It is also important to note that an additional firm increases the number of all possible firm-firm knowledge links and thus the potential for knowledge spillovers by the number of firms already present.Footnote1 Consequently, if new entries increase related variety in the region then technological proximity across firms has an increasing chance to further boost agglomeration economies.

Related diversification indeed seems to be the rule (Hidalgo et al., Citation2018), while country-level evidence shows that unrelated diversification is rare, happening at an intermediate level of economic development (Pinheiro, Alshamsi, Hartmann, Boschma, & Hidalgo, Citation2018). It is important to note that the subsequent relative shrinking of unrelated variety within the local economy may hinder long-term growth potential (Saviotti & Frenken, Citation2008), and resilience against economic shocks (Frenken et al., Citation2007). Indeed, the diversification slows down and becomes more related during times of crisis, and more diverse cities outperform more specialized cities in diversifying during times of crisis (Steijn, Balland, Boschma, & Rigby, Citation2019). What's more, agglomeration forces may enhance entry during economic expansion and exit during a recession (Cainelli et al., Citation2014).

We further propose that growing relatedness in the foreign subset of the regional economy can affect the domestic firms of the same region positively. Because relatedness co-evolves with other aspects of agglomeration economies such as local value chains (Cainelli & Iacobucci, Citation2012), the growing capacity of knowledge spillovers and labour pooling across foreign firms, and the increasing returns created thereof can generate growing demand for intermediary goods and services, which might be beneficial for the local economy as a whole. As a result, the dynamics of local firms can take off even if knowledge externalities have low potential in those segments.

Our expectations on the changing association between variety and firm survival is first that the importance of related variety increases in the host economy following economic restructuring, because self-reinforcing benefits take time to form. Second, the positive spillovers of related variety matter more for firm survival in times of stability, while the stabilizing portfolio-effect of unrelated variety matters more in times of economic turmoil.

2.4. Case description

Our particular case is the transformation of Hungarian regions, in which regions that were specialized in heavy industry during the socialist era faced serious difficulties and declined in the 1990s (Lengyel & Szakálné Kanó, Citation2013). Starting from the second half of the 1990s, foreign firms became key actors in determining the export and employment levels of regional industries (Kállay & Lengyel, Citation2008; Lengyel, Citation2003). These firms brought new knowledge into the regions offering new sources of dynamics (Halpern & Muraközy, Citation2007; Inzelt, Citation2003). The location choices of foreign firms were extremely concentrated and did not change significantly between 1994 and 2002 (Antalóczy & Sass, Citation2005). Previous research showed that despite their central position, the local interactions between foreign and domestic firms evolved slowly (Békés et al., Citation2009; Lengyel & Leydesdorff, Citation2015; Lengyel & Szakálné Kanó, Citation2014).

Taking history under consideration, in our empirical analysis we address three major characteristics of regional development during the post-socialist transition in CEE countries. First, the collapse of the Comecon was an elementary external shock leaving most traded industries with limited experience in accessing international input and output markets, as well as a sudden exposure to global competition (Rodrik, Citation1992). Thus, we look at firm failure and investigate how characteristics of the local economy have reduced the probability of firm exit. Second, development paths in regions under post-socialist transition are often argued to differ from the gradual development in more developed regions (Lengyel & Leydesdorff, Citation2011; Novotny, Blažek, & Květoň, Citation2016; Sokol, Citation2001; Zenka, Novotny, & Csank, Citation2014). An important previous finding suggests that the emergence of agglomeration economies has speeded up in the 2000s in the CEE countries (Strano & Sood, Citation2016), and therefore we aim to uncover if related variety have started to express only in later phases of the transition. Finally, FDI became a major engine of economic growth, and the presence of the subsidiaries of large MNEs was crucial in regional transformation (Pavlínek, Citation2004; Radosevic, Citation2002; Resmini, Citation2007). Therefore, we investigate whether the technological relatedness of co-located foreign firms have generated agglomeration economies, which would have influenced the dynamics of domestic firms as well.

3. Research design

3.1. Data and sample selection

We rely on a firm-level dataset that was provided to us by the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (HCSO), consisting of annual census-type data of Hungarian firms, compiled from financial statements associated with tax reporting that were submitted to the National Tax Authority in Hungary by legal entities using double-entry bookkeeping. The observation period is between 1995 and 2012 on a yearly basis. The data contains basic information on each firm, including the LAU2 region (settlement) of the company seat, the 4-digit NACE code of its main activity, the annual average number of employees, the amount of equity capital held by different types of owners, and major financial indices at the end of each term. Foreign ownership was attributed to a firm if more than 50% of its total equity capital was in foreign hands.

Our investigation is limited to manufacturing firms for two reasons. First, available company seat data are more likely to represent the actual site of the productive activity in the case of manufacturing industries in Hungary (Békés & Harasztosi, Citation2013). Second, the location decision of manufacturing firms can be expected to be influenced more strongly by local knowledge externalities and related variety compared to service firms, because the latter may be motivated by the presence of customers (Frenken et al., Citation2007; Mameli, Iammarino, & Boschma, Citation2012). In order to increase the reliability of the data, we exclude those firms from the sample that never reached at least five employees during the period of interest, because the quality of the data compiled from the balance sheets of Hungarian firms with less than five employees have been considered unreliable in previous studies (Békés & Harasztosi, Citation2013).

In terms of geography, we focus our attention on firms located in city regions identified on the basis of daily commuting trends aggregated from census data by the HCSO. It has been reported repeatedly that the majority of manufacturing industries is concentrated in these 23 agglomeration areas around major settlements (Tóth, Citation2014), and as such, city regions represent concentrations of economic activity where related variety can reasonably be expected to have an effect. The majority of both foreign and domestic firms, as well as corresponding employees are located within city regions (58–68%) throughout the period of the analysis (Appendix 1 and 2). The boundaries of these city regions change over time, mostly due to changing commuting patterns, thus, we use the 2012 classification consistently over the period of the analysis.

Finally, we exclude those firms from the sample that were present for just one year or were present in the data with gaps. Thus the final sample is a panel database with 169,048 firm-year combinations consisting of 21,491 unique firms being listed 7.87 times on average.

3.2. The calculation of the variety indicators

We depart from the seminal work of Frenken et al. (Citation2007) in the first step of calculating the related and unrelated variety indicators. They claim that two co-located firms are technologically unrelated when they do not share two-digit NACE codes. Two co-located firms are technologically related when they share the same two-digit NACE codes but do not share the four-digit NACE code. The rationale behind these assumptions is that related firms may share enough knowledge but are not too proximate; therefore, they can not only understand but may also learn new things from one other, whereas unrelated firms may not be able to learn from one other because they exploit different technologies.

This approach relies on entropy-calculation in measuring diversity, frequently used in economics and regional studies (Dusek & Kotosz, Citation2016; Frenken, Citation2007). The distinction between related and unrelated variety (i.e. entropy decomposition) on the basis of a standard industrial classification leads to an ex ante measure of relatedness. This means that such taxonomies classify industries in the same category precisely because they are expected to have some degree of relatedness. While unavailability of data prevented us from using an ex post measure of relatedness based of products or skills (for comparison of ex ante and ex post measures see e.g. Boschma, Eriksson, & Lindgren, Citation2014), using the entropy-measure increases the comparability of our results with previous studies (Blažek, Marek, & Květoň, Citation2016). Furthermore, with this paper, we aim to refine the decomposition procedure by introducing firm ownership as an additional level.

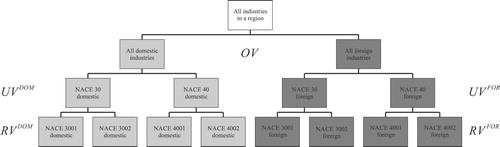

We develop an alternative model in order to account for the various forms of foreign-domestic knowledge spillovers in the context of the entropy decomposition. This development is important in the case of firm-level dynamics in Hungary because the technological proximity and gap between foreign and domestic firms were crucial in regional development as reported by previous research (e.g. Lengyel & Szakálné Kanó, Citation2014). Unlike in previous papers, in which related variety was decomposed into subsets of manufacturing and service industries (Mameli et al., Citation2012), or high-tech manufacturing (Hartog, Boschma, & Sotarauta, Citation2012) by technological categories, the introduction of ownership categories requires an additional level in entropy-decomposition.

In a previous paper, we showed that in principle ownership can be introduced at different levels of the entropy decomposition, and that introducing the new level in the decomposition at the level of the whole economy fits best the foreign-domestic duality of the Hungarian economy (Szakálné Kanó, Lengyel, Elekes, & Lengyel, Citation2017). In this model, economic variety measured in the region is equal to the entropy of the employment distribution of the finest bin structure, which is the four-digit NACE code combined with the ownership category. This approach yields the main variables of interest, namely two related variety ( and

) and two unrelated variety (

and

) measures. A higher value of these measures indicates an increased variety of economic activities among foreign or domestic firms. Ownership variety (

) is an additional variable yielded by this approach indicating how balanced is the number of foreign and domestic firms (weighted by employment) in a region (). A higher value of ownership variety indicates a more balanced distribution of firms over the ownership groups.

Figure 1. Variety decomposition with ownership.

Note: light grey represents the domestic subset and dark grey represents the foreign subset of firms.

More formally, let poi be the share of employment in industries with four-digit NACE codes combined with ownership categories. Let poi add up to Pog, which is the share of employment in two-digit NACE codes combined with ownership categories. Additionally, let the sum of Pog be Po, the share of employment in all industries combined with ownership categories. Finally, let d indicate the domestic set of firms and f the foreign set of firms.

Economic variety measured in the region will be equal to the entropy of the employment distribution of the finest bin structure, which is the four-digit NACE code combined with the ownership category (Equation (1)). The overall variety in a region then equals the variety measured in the ownership distribution () plus the weighted sum of domestic and foreign unrelated varieties (

and

) and the weighted sum of domestic and foreign related varieties (

and

) (Equations (2)–(9)):

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

(8)

(8)

(9)

(9)

3.3. Specification of the econometric model for firm exit

A previous paper found the dynamically changing effect of related variety on employment growth in Hungarian regions (Lengyel & Szakálné Kanó, Citation2013). In order to detect these changing effects of the explanatory variables, we apply time period dummies in the analysis. We divide the whole 16-year timespan into four equal time periods, each of which can be associated with significantly different eras in the post-socialist transition of the Hungarian economy. A fast liberalization and dynamic economic growth characterized the first period (1996–1999). Next, the country prepared for joining the EU in the second period (2000–2003), followed by an economic slowdown in the third period (2004-2007) and a more dramatic downturn in the fourth period (2008–2011). We use all four periods respectively as baselines for the investigation in four variants of the model in order to obtain the significance level of being different from zeroFootnote2 for coefficients of each period separately. These four variants differ from each other only in meaning of reported coefficients and have the same model-description statistics.

During the econometric analysis, following Disney, Haskel, and Heden (Citation2003), those firms are considered to exit in year that are present in the sample in year

, but not in

. To establish such exit status, we also used data for 2012, but subsequently dropped them from the analysis as all firms would have exited in 2012. After sample selection every firm had at most one exit during the 16 years period of the analysis. Consequently

is a binary dependent variable taking the value of 1 in the last year the firm is observed in the data, and 0 otherwise.

The entryFootnote3 activity of foreign firms steadily decreased from cca. 130 to cca. 35 during the period of the analysis, while exit was more stable, increasing from cca. 35 to cca. 75 instances per year. Altogether the total entry of foreign-owned firms exceeded their total exit up until 2000, since then the number of foreign firms slowly declined. The dynamics of domestic firms show similar patterns with more stability. Total exit in this group exceeded total entry after 2006. The peak in entry activity in 2004 is due to a change in the regulations on mandatory double-entry bookkeeping. Overall, the firm population dynamics indicate a slowly decreasing number of firms, especially since the late 2000s, most likely due to the general slow-down of the Hungarian economy.

A fixed effect model is applied as this approach allow for us to control for time invariant unobserved firm characteristics to some extent. Explanatory variables are lagged by 1 year in order to account for the widely observed impedance of agglomeration externalities to express their effect on the regional economy. We tested different lags as a robustness check, ranging from 1 to 3 yielding similar results. So as to test for the relation between variety and firm exit, we run fixed effects panel logit models for the whole 16-year-period with period dummies (Equation (10)):(10)

(10)

is an

vector, containing values of explanatory variables and values of the time period dummy-interactions for firm

and year

.

is an

vector, containing values of control variables for firm

and year

.

is an

vector of the coefficients of the explanatory variables and the time period dummy-interactions and

is an

vector of the coefficients of the control variables. In our case parameter

is equal to 20, while

is equal to 24.

We use xtlogit, fe (STATA command) to estimate the coefficients, which runs a conditional maximum likelihood method. This technique means that a likelihood function is conditioned on total number of events observed for each firm. Consequently, the contribution of one particular firm to the likelihood function is measured by the probability of the firm’s exiting the economy in the actual year in which it occurred rather than in one of the other possible years.Footnote4 Fixed effect models take into account only those firms which had exactly once in the 16 year period under investigation.Footnote5 We use fixed effect instead of random effect approach in order to avoid omitted variable bias. The within variation is big enough compared to the between variation of the explanatory and the control variables (), which further underlines the relevance of fixed effect models.

Table 1. Panel descriptives of explanatory and control variables.

A number of control variables are used for the exit models. As related and unrelated variety are the main focus of this paper, we control for other types of agglomeration economies in two ways. Location quotient () is used to control for the level of specialization of a city region on a given 2-digit NACE industry, while Ellison–Glaeser γ (

) controls for the level of economies of scale external to the firms within the industry. Besides these average firm size (

) in the 2-digit industry of the firm in a city region controls for the level of economies of scale internal to the firms within the industry.Footnote6 At the firm level we use the number of employees (

) and total equity capital (

) to control for different aspects of firm size. An additional firm level dummy variable (

) is used to control for unsuccessful firms, taking the value of 1 if the net result of the firm was negative in the year of exiting (see for panel descriptives of the independent variables). When looking at the variance inflation factor (VIF)Footnote7 values of the right hand side variables we concluded that multicollinearity is unlikely to be an issue in the models: the values stay below 5 in most cases and never exceed 10 (see for pairwise correlation of coefficients and VIF values).

Table 2. Pairwise correlation of coefficients and VIF values in the models of .

4. Results

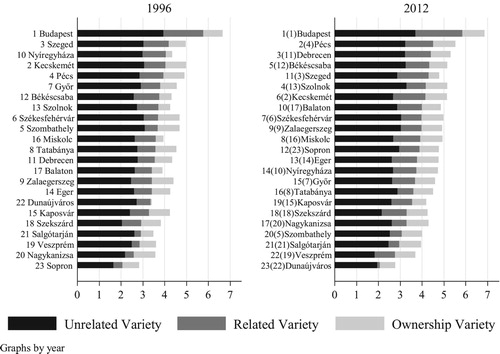

So as to get a general impression on the change of the variety measures over time we sorted Hungarian city regions by variety in a descending order for years 1996 and 2012, and plotted the decomposed variety measures into ownership-, unrelated-, and related variety values. As one would expect, Budapest, the capital with its suburban area has the highest variety value, while the heavily industrialized region of Dunaújváros has the lowest ().

Figure 2. Related variety, unrelated variety and ownership variety index values for city regions in 1996 and 2012.

Note: city regions were sorted by the sum of unrelated and related variety (ownership variety excluded). The numbers indicate the total variety ranking (related, unrelated and ownership variety together). The numbers in parentheses in column 2012 indicate the total variety ranking in 1996.

Some important connections can be made between this picture on variety and our econometric specification. First, adding the ownership level into the entropy-decomposition is necessary and meaningful, because ownership variety plays a pronounced role in shaping the ranking of city-regions by variety. Second, this role slightly decreases over time, and ownership variety values become much more similar between city regions by 2012, suggesting an equalization process in terms of spatial distribution of FDI in the background. Third, unrelated variety seemed to play a role in the reordering the city regions throughout our period of interest. As expected, the variety of economic activities in regions changes slowly over time; however, related variety among domestic firms increased considerably between 1996 and 2012. This offers some initial support for our expectation of widening opportunities for knowledge spillovers between these firms. The largest component of variety throughout the whole period remains to be the unrelated variety within ownership groups. Ownership variety shows only a slight increase over the entire period, while also having the lowest within variance among the variety indicators ().

Now we turn to our estimations on the probability of firm exit (). We differentiate the dependent variables based on ownership to look for any cross-group effects, running separate regressions for all firms, the subsample of domestic firms and the subsample of foreign firms. The fact that we study only those firms that exited regions creates a different empirical setting compared to studying employment or productivity growth. This is because we do not analyse incumbent firms, we only compare the circumstances of an existing firm to the circumstances of the same firm in its incumbent period. The fixed effect model offers a way to compare the deviation in the conditions of the firm from the average condition of the same firm during its presence in the sample, i.e. the comparison is between the incumbent years and the last year of the firm's presence. All the models are statistically significant with good log likelihood values, while admittedly the exit decision of foreign firms seem to be less dependent on the factors we observe in the models.

Table 3. Panel logit regression results for firm exit between 1996 and 2011.

The applied control variables show plausible relations with firm exit. Specialization () has a positive effect on exit suggesting that high demand on productivity stemming from local competition is a challenging environment for incumbents. This is in line with the observation that competition intensifies in more specialized regions (Iammarino & McCann, Citation2013). This effect was strongest after 2000, and is visible mostly for domestic firms, underlining that these firms are more vulnerable to productivity pressure compared to foreign firms. The spatial concentration of industries (

) after 2000 shows negative effect on exit, showing that incumbents benefit from external economies of scale in regions. This comes mostly from the domestic subset of firms. The average firm size (

) at the 2-digit NACE level has a negative relation with exit pointing towards the benefits of internal economies of scale. Domestic firms tend to access these benefits throughout the period in question, while foreign firms are more independent of them, especially after Hungary joined the EU in 2004. Counter intuitively, higher capital endowment (

) increases the probability of exit, more specifically in the case of domestic firms. Evidently, higher total equity capital puts domestic firms at risk. This may be linked to the internal structure of total equity capital, but unfortunately, we have no data on capital assets to investigate this further. Firm size measured by employment (

) works as expected, showing that large firms are less likely to fail (Dunne, Roberts, & Samuelson, Citation1989). The same goes for being in loss in the year of the exit (

), as this is a strong predictor of leaving the region.

Turning to the coefficient on ownership variety (), it shows a significant positive effect on firm exit throughout the period of observation, meaning that having a closer to equal number of foreign and domestic firms (weighted by employment) increases the chance of firm exit. The strength of this effect was lowest during the early to mid-2000s, when relative economic stability surrounded firms. This suggests that a more balanced regional composition of foreign and domestic firms, which in many cases means an increased share of foreign firms, is less desirable for incumbents, possibly because of stronger competition for markets and regional capabilities, and also because of better-established ‘local buzz-global pipelines’-type relations that initially pose high entry costs. These barriers are present for domestic and foreign firms alike.

The coefficient of the related variety of domestic firms () shows an interesting pattern throughout the period in question. It shows negative effect on exit in the 2004–2007 period, during the first few year of the Hungarian EU membership. This suggests that the benefits attributed to related variety indeed became relevant between domestic firms as the Hungarian market economy consolidated. One possible explanation is that in the first two periods the competitive aspect of transitioning into a market economy dominated firm behaviour, especially in the domestic subgroup that was slowly adapting to the exposure to global competition. Later on, firms may have recognized the cooperative aspects of economic activities enabling the occurrence of knowledge spillovers commonly attributed to related variety. With the economic downturn of 2008, the spillover potential between domestic firms became dominated by competition for resources once again. Additionally, domestic and foreign firm exit is affected the same way following the EU accession. One can expect that related variety in a region decreases the probability of firm exit because there is a higher level of intermediate goods and services in the region, and technological relatedness boosts the prevalence of agglomeration economies (Cainelli & Iacobucci, Citation2012). This finding is in line with previous observations regarding the changing effect of related variety on employment growth in Hungarian regions (Lengyel & Szakálné Kanó, Citation2013), and further supports the idea that fully restructured input-output relations due to the economic transition left their mark on agglomeration economies as well.

As opposed to the previous pattern, the related variety of foreign firms () proved to be consistently beneficial for incumbent firms throughout the whole period. In the 2000s, domestic firms in particular were more likely to stay in regions with more related variety among foreign firms. Apparently, the related variety of foreign firms expressed its effect much earlier than that of domestic firms, hinting that foreign firms have been transformative agents of the Hungarian regional economies. Firm exit in both cases shows this pattern indicating that the benefits expected from related variety are expressed to some degree once a firm entered a region. As a final point, foreign firms seem to be unaffected by related variety within their group from 2000 up until 2008. This suggests that different drivers are motivating these foreign investments taking place in resource and investment driven regional economies compared to the ones in knowledge and innovation oriented regions.

As for unrelated variety, arguments about intermediate products may also be relevant because the diversity without technological proximity involved also increases the variety of locally available intermediate products and services. The unrelated variety of domestic firms () is becoming unable to prevent domestic firm exit over time, suggesting that earlier on the relative safety of unrelated variety in the host economy helped the more unprepared domestic local competitors. Interestingly, the unrelated variety of foreign firms (

) in particular was beneficial in times of economic turmoil, most notably before 2000, and after 2008. This however is stemming particularly from domestic firms, as foreign ones are barely affected by unrelated variety. As a last point, it seems that the effects of related and unrelated variety change over time with an opposite sign: as related variety became a stabilizing factor for incumbents over this transition period, so did unrelated variety loose its relevance in firm exit. One possible explanation for this is that unrelated variety may be less demanding in terms of being part of a knowledge network or being able to attract highly skilled workers to access benefits expected from related variety. In sum, these findings suggest that unrelated variety may be more important during the initial stage of regional transition in an economy that suffers from major shock that is not industry-specific, affecting the entire economy. However, as agglomeration economies start to be expressed and knowledge spillovers gain importance, related variety gets a more significant role.

5. Conclusions and further research

The aim of this paper was to explore how the related variety of foreign firms and the host economy relates to firm survival in regions that went through major structural and institutional transformation. Our empirical analysis featured the case the city regions of Hungary, a country with a small open economy and a duality of foreign and domestic firms that was formed during the period of economic transition after 1990. Relying on a unique dataset offering information on the ownership structure of manufacturing firms, we found evidence for transition patterns in related variety and firm exit, especially when looking at the interplay between foreign and domestic firms.

A number of conclusions can be drawn from our findings. First, the role of agglomeration economies in general and related variety in particular as a driving force of churn in the firm population of regions changed during the period in question. The variety of the industry structure of regions became an important source of agglomeration economies after 2000. More specifically the related variety of industries started to have a stronger association with firm exit at a later phase compared to unrelated variety, suggesting that the portfolio effect often attributed to the latter was slowly substituted by the spillover benefits of the former. These findings may suggest that technological proximity became important as cooperation among co-located actors slowly evolved after the major economic transition. Second, the related variety of domestic firms became a source of agglomeration economies later on. Interestingly the related variety of foreign firms has shown such a stabilizing effect in the host economy earlier on, and was an increasingly beneficial feature of regions for domestic firms, as the interactions between the two groups became more complex over time. Third, these findings point towards that FDI and MNEs were transformative actors for the host regions in the earlier stages of the economic transition, while foreign firms themselves were barely affected by potential spillovers throughout the transition.

This paper takes a step towards linking agglomeration economies mediated by technological relatedness and firm population dynamics in regions under transition. However, as any other paper, our study has a number of limitations which should be taken up in future research.

First, this analysis was performed on a single case study on Hungarian regions. A more comprehensive analysis on agglomeration economies and relatedness in the former Eastern Bloc would be able to verify the external validity of our findings, a task we could not take up on due to the lack of firm-level data. That being said, we consider our results to be of relevance to other CEE countries that went through a similar transition, as well as to regions of more developed economies going through turbulent economic restructuring.

Second, with our data at hand, we could not differentiate between different internationalization strategies of MNEs. Indeed the direct and indirect effect from the related variety of foreign firms on the host region may depend on the strategy of these firms to exploit lower labour cost, obtain new consumer markets or reconfiguring pre-existing local manufacturing capabilities.

Finally, we could not link directly the individual firm to the regional portfolio of economic activities, and thus related variety is effectively considered a public good available in the region. This limitation, also present in other papers on related variety based on entropy-decomposition, could be remedied if appropriate data on products produced (e.g. Neffke, Henning, & Boschma, Citation2011), or labour mobility between industries were available (e.g. Boschma et al., Citation2014). An interesting question is whether relatedness to the foreign or domestic industrial portfolio of regions is more important for the survival of firms. In other words, the push or pull effect of foreign firms and the host economy could be assessed, especially when differentiating between foreign and domestic exit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Izabella Szakálné Kanó http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4149-1243

Balázs Lengyel http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5196-5599

Zoltán Elekes http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7437-5791

Imre Lengyel http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9225-5320

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 If N is the number of firms in the region then the maximum number of knowledge links in the firm knowledge network is N x (N-1)/2, which depends quadratically on N. If one new firm enters then the number of potential links raises by N, because this new firm can potentially build link to each present firm.

2 One particular model variant would give the coefficients for the baseline period and differences from coefficients of baseline period for the other periods. Hence for the other periods this variant reports significance level of being different from coefficient of the baseline period; we do not list other periods in the table.

3 For the purposes of this descriptive, was also generated, taking the value of 1 if a firm was present in the dataset in year

but not in

, and 0 otherwise. Data for 1995 was used for this calculation.

4 For further explanation of fixed effects panel logit models see Allison (Citation2009).

5 This is the reason for having fewer than 169,048 observations of firms in the regression tables.

6 Population density was also considered as a control for the size of agglomerations, but it had high linear correlation with related and unrelated variety variables, therefore we excluded it from our analysis.

7 VIF measures the linear association between an independent variable and all the other independent variables. A VIF value of higher than 5 warrants further investigation, and a value of higher than 10 indicates a high chance of multicollinearity (Rogerson, Citation2001).

References

- Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. Series: Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences 160. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Almeida, P., & Kogut, B. (1997). The exploration of technological diversity and the geographical localization of innovation. Small Business Economics, 9, 21–31. doi: 10.1023/A:1007995512597

- Antalóczy, K., & Sass, M. (2005). A külföldi működőtőke-befektetések regionális elhelyezkedése és gazdasági hatásai Magyarországon. Közgazdasági Szemle, 52, 494–520.

- Arthur, B. (1990). Silicon valley locational clusters: When do increasing returns imply monopoly? Mathematical Social Sciences, 19, 235–251. doi: 10.1016/0165-4896(90)90064-E

- Barrel, R. & Pain, N. (1999). Domestic institutions, agglomerations and foreign direct investment in Europe. European Economic Review, 43, 925–934. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00105-6

- Basile, R., Pittiglio, R., & Reganati, F. (2017). Do agglomeration externalities affect firm survival? Regional Studies, 51, 548–562. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1114175

- Beaudry, C., & Schiffauerova, A. (2009). Who's right, Marshall or Jacobs? The localization versus urbanization debate. Research Policy, 38, 318–337. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2008.11.010

- Békés, G., & Harasztosi, P. (2013). Agglomeration premium and trading activity of firms. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 43, 51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2012.11.004

- Békés, G., Kleinert, J., & Toubal, F. (2009). Spillovers from multinationals to heterogeneous domestic firms: Evidence from Hungary. World Economy, 32, 1408–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01179.x

- Beugelsdijk, S., McCann, P., & Mudambi, R. (2010). Introduction: Place, space and organization – economic geography and the multinational Enterprise. Journal of Economic Geography, 10, 485–493. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbq018

- Blažek, J., Marek, D., & Květoň, V. (2016). The variety of related variety studies: Opening the black box of technological relatedness via analysis of inter-firm R&D cooperative projects. Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography, 1301, University Utrecht, Faculty of Geosciences.

- Borggren, J., Eriksson, R. H., & Lindgren, U. (2016). Knowledge flows in high-impact firms: How does relatedness influence survival, acquisition and exit? Journal of Economic Geography, 16, 637–665. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbv014

- Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39, 61–74. doi: 10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Boschma, R., Eriksson, R. H., & Lindgren, U. (2014). Labour market externalities and regional growth in Sweden: The importance of labour mobility between Skill-related industries. Regional Studies, 48, 1669–1690. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.867429

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2006). Why is economic geography not an evolutionary science? Towards an evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 6, 273–302. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbi022

- Boschma, R., & Iammarino, S. (2009). Related variety, trade linkages, and regional growth in Italy. Economic Geography, 85, 289–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01034.x

- Boschma, R., & Wenting, R. (2007). The spatial evolution of the British automobile industry: Does location matter? Industrial and Corporate Change, 16, 213–238. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtm004

- Cainelli, G., & Iacobucci, D. (2012). Agglomeration, related variety, and vertical integration. Economic Geography, 88, 255–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2012.01156.x

- Cainelli, G., Montresor, S., & Marzetti, G. V. (2014). Spatial agglomeration and firm exit: A spatial dynamic analysis for Italian provinces. Small Business Economics, 43, 213–228. doi: 10.1007/s11187-013-9532-6

- Cantwell, J. (2009). Location and the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 35–41. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2008.82

- Cantwell, J., & Iammarino, S. (2000). Multinational corporations and the location of technological innovations in the UK regions. Regional Studies, 34, 317–332. doi: 10.1080/00343400050078105

- Cantwell, J., & Iammarino, S. (2003). Multinational corporations and European regional systems of innovation. London, New York: Routledge.

- Capello, R. (2009). Spatial spillovers and regional growth: A cognitive approach. European Planning Studies, 17, 639–658. doi: 10.1080/09654310902778045

- Christopherson, S., & Clark, J. (2007). Power in firm networks: What it means for regional innovation systems. Regional Studies, 41, 1223–1236. doi: 10.1080/00343400701543330

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 128–152. doi: 10.2307/2393553

- Content, J., & Frenken, K. (2016). Related variety and economic development: A literature review. European Planning Studies, 24, 2097–2112. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1246517

- Crescenzi, R., Gagliardi, L., & Iammarino, S. (2015). Foreign multinationals and domestic innovation: Intra-industry effects and firm heterogeneity. Research Policy, 44, 596–609. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2014.12.009

- Csáfordi, Z., Lőrincz, L., Lengyel, B., & Kiss, K. M. (2018). Productivity spillovers through labor flows: Productivity gap, multinational experience and industry relatedness. The Journal of Technology Transfer. doi: 10.1007/s10961-018-9670-8

- Delios, A., Xu, D., & Beamish, P. W. (2008). Within-country product diversification and foreign subsidiary performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 39, 706–724. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400378

- Disney, R., Haskel, J., & Heden, Y. (2003). Entry, exit and establishment survival in UK manufacturing. Journal of Industrial Economics, 51, 91–112. doi: 10.1111/1467-6451.00193

- Dunne, T., Roberts, M. J., & Samuelson, L. (1989). The growth and failure of U.S. manufacturing plants. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104, 671–698. doi: 10.2307/2937862

- Duranton, G., & Puga, D. (2001). Nursery cities: Urban diversity, process innovation, and the life cycle of products. American Economic Review, 91, 1454–1477. doi: 10.1257/aer.91.5.1454

- Duranton, G., & Puga, D. (2004). Micro-foundations of urban agglomeration economies. In J. V. Henderson, & J. V. Thisse (Eds.), Handbook of regional and urban Economics (pp. 2063–2117). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Dusek, T., & Kotosz, B. (2016). Területi Statisztika. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Elekes, Z., Boschma, R., & Lengyel, B. (2019). Foreign-owned firms as agents of structural change in regions. Regional Studies. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2019.1596254

- Falck, O. (2007). Survival chances of new businesses: Do regional conditions matter? Applied Economics, 39, 2039–2048. doi: 10.1080/00036840600749615

- Frenken, K. (2007). Entropy statistics and information theory. In H. Hanusch, & A. Pyka (Eds.), Elgar Companion to Neo-Schumpeterian Economics (pp. 544–555). Cheltenham – Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Frenken, K., van Oort, F., & Verburg, T. (2007). Related variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Regional Studies, 41, 685–697. doi: 10.1080/00343400601120296

- Gao, J., Jun, B., Pentland, A., Zhou, T., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2017). Collective learning in China’s regional economic development. arXiv Preprint. Retrieved from: https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.01369

- Glaeser, E., Kallal, H. D., Scheinkman, J. D., & Shleifer, A. (1992). Growth in cities. Journal of Political Economy, 100, 1126–1152. doi: 10.1086/261856

- Gorg, H., & Strobl, E. (2001). Multinational companies and productivity spillovers: A meta-analysis. The Economic Journal, 111, F723–F739. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.00669

- Halpern, L., & Muraközy, B. (2007). Does distance matter in spillover? The Economics of Transition, 15, 781–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0351.2007.00308.x

- Hartog, M., Boschma, R., & Sotarauta, M. (2012). The impact of related variety on regional employment growth in Finland 1993–2006: High-tech versus medium/low-tech. Industry and Innovation, 19, 459–476. doi: 10.1080/13662716.2012.718874

- Henderson, J. V., Kuncoro, A., & Turner, M. (1995). Industrial development in cities. Journal of Political Economy, 103, 1067–1090. doi: 10.1086/262013

- Hidalgo, C. A., Balland, P. A., Boschma, R., Delgado, M., Feldman, M., Frenken, K., … Zhu, S. (2018). The principle of relatedness. In International conference on complex systems (pp. 451–457). Cham: Springer.

- Howell, A., He, C., Yang, R., & Fand, C. C. (2018). Agglomeration, (un)-related variety and new firm survival in China: Do local subsidies matter? Papers in Regional Science, 97, 485–500. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12269

- Iammarino, S., & McCann, P. (2013). Multinationals and economic geography. Cheltenham – Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Inzelt, A. (2003). Foreign involvement in acquiring and producing new knowledge: The case of Hungary. In J. Cantwell, & J. Molero (Eds.), Multinational enterprises, innovative strategies and systems of innovation (pp. 234–268). Cheltenham – Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Jacobs, J. (1969). The economy of cities. New York: Random House.

- Jara-Figueroa, C., Jun, B., Glaeser, E. L., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2018). The role of industry-specific, occupation-specific, and location-specific knowledge in the growth and survival of new firms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115, 12646–12653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800475115

- Javorcik, B. S., Lo Turco, A., & Maggioni, D. (2017). New and improved: Does FDI boost production complexity in host countries? The Economic Journal, doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12530

- Jun, B., Pinheiro, F., Buchmann, T., Yi, S., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2017). Meet me in the middle: The reunification of Germany’s research network. arXiv Preprint. Retrieved from: https://arxiv.org/abs/1704.08426

- Kállay, L., & Lengyel, I. (2008). The internationalization of Hungarian SMEs. In L. P. Dana, I. M. Welpe, M. Han, & V. Ratten (Eds.), Handbook of research on European business and entrepreneurship. Towards a theory of internationalization (pp. 277–295). Cheltenham – Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Keller, W., & Yeaple, S. R. (2009). Multinational enterprises, international trade, and productivity growth: Firm level evidence from the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91, 821–831. doi: 10.1162/rest.91.4.821

- Ledyaeva, S. (2009). Spatial econometric analysis of foreign direct investment determinants in Russian regions. World Economy, 32, 643–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9701.2008.01145.x

- Lengyel, B., & Leydesdorff, L. (2011). Regional innovation systems in Hungary: The failing synergy at the national level. Regional Studies, 45, 677–693. doi: 10.1080/00343401003614274

- Lengyel, B., & Leydesdorff, L. (2015). The effects of FDI on innovation systems in Hungarian regions: Where is the synergy generated?. Regional Statistics, 5, 3–24. doi: 10.15196/RS05101

- Lengyel, B., & Szakálné Kanó, I. (2013). Related variety and regional growth in Hungary: Towards a transition economy approach. Regional Statistics, 3, 98–116. doi: 10.15196/RS03106

- Lengyel, B., & Szakálné Kanó I. (2014). Regional economic growth in Hungary 1998–2005: What does really matter in clusters? Acta Oeconomica, 64, 257–285. doi: 10.1556/AOecon.64.2014.3.1

- Lengyel, I. (2003). The pyramid model: Enhancing regional competitiveness in Hungary. Acta Economica, 53, 323–342.

- Lengyel, I., Vas, Z., Szakálné Kanó, I., & Lengyel, B. (2017). Spatial differences of reindustrialization in a post-socialist economy: Manufacturing in the Hungarian counties. European Planning Studies, 25, 1416–1434. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1319467

- Lorenzen, M., & Mahnke, V. (2002). Global strategy and the acquisition of local knowledge: How MNCs enter regional knowledge clusters. Paper presented at the DRUID Summer Conference on “Industrial Dynamics of the New and Old Economy - who is embracing whom?”, Copenhagen/Elsinore.

- Mameli, F., Iammarino, S., & Boschma, R. (2012). Regional variety and employment growth in Italian labour market areas: Services versus manufacturing industries. Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography, 1203, University Utrecht, Faculty of Geosciences.

- Marshall, A. (1920). Principles of Economics. (8th ed). London: MacMillan.

- McCann, P. (2008). Agglomeration economies. In C. Karlsson (Ed.), Handbook of research on cluster theory (pp. 23–38). Cheltenham – Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Myrdal, G. (1957). Economic theory and underdeveloped regions. London: Duckworth.

- Neffke, F., Hartog, M., Boschma, R., & Henning, M. (2018). Agents of structural change: The role of firms and entrepreneurs in regional diversification. Economic Geography, 94, 23–48. doi: 10.1080/00130095.2017.1391691

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., & Boschma, R. (2011). How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of New growth paths in regions. Economic Geography, 87, 237–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

- Neffke, F. M. H., Henning, M., & Boschma, R. (2012). The impact of aging and technological relatedness on agglomeration externalities: A survival analysis. Journal of Economic Geography, 12, 485–517. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbr001

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., Boschma, R., Lundquist, K.-J., & Olander, L.-O. (2011). The dynamics of agglomeration externalities along the life cycle of industries. Regional Studies, 45, 49–65. doi: 10.1080/00343401003596307

- Novotny, J., Blažek, J., & Květoň, V. (2016). The anatomy of difference: Comprehending the evolutionary dynamics of economic and spatial structure in the Austrian and Czech economies. European Planning Studies, 24, 788–808. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1139060

- Pavlínek, P. (2004). Regional development implications of foreign direct investment in central Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 11, 47–70. doi: 10.1177/0969776404039142

- Phelps, N. A. (2004). Clusters, dispersion and the spaces in between: For an economic geography of the banal. Urban Studies, 41, 971–989. doi: 10.1080/00420980410001675887

- Phelps, N. A. (2008). Cluster or capture? Manufacturing foreign direct investment, external economies and agglomeration. Regional Studies, 42, 457–473. doi: 10.1080/00343400701543256

- Pinheiro, F. L., Alshamsi, A., Hartmann, D., Boschma, R., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2018). Shooting high or low: Do countries benefit from entering unrelated activities?. ArXiv preprint, arXiv:1801.05352.

- Radosevic, S. (2002). Regional innovation systems in central and Eastern Europe: Determinants, organizers and alignments. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 27, 87–96. doi: 10.1023/A:1013152721632

- Resmini, L. (2007). Regional Patterns of industry location in transition countries: Does economic integration with the European Union matter? Regional Studies, 41, 747–764. doi: 10.1080/00343400701281741

- Rodrik, D. (1992). Making sense of the Soviet trade shock in Eastern Europe: A framework and some estimates. NBER Working Paper, No. 4112.

- Rogerson, P. A. (2001). Statistical methods for geography. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

- Saviotti, P. P., & Frenken, K. (2008). Export variety and the economic performance of countries. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 18, 201–218. doi: 10.1007/s00191-007-0081-5

- Sokol, M. (2001). Central and Eastern Europe a decade after the fall of state-socialism: Regional dimensions of transition processes. Regional Studies, 35, 645–655. doi: 10.1080/00343400120075911

- Steijn, M. P. A., Balland, P.-A., Boschma, R. A., & Rigby, D. L. (2019). Technological diversification of U.S. cities during the great historical crises. Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography, 1901, University Utrecht, Faculty of Geosciences.

- Strano, E., & Sood, V. (2016). Rich and poor cities in Europe. An urban scaling approach to mapping the European economic transition. PLoS ONE, 11, e0159465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159465

- Szakálné Kanó, I., Lengyel, B., Elekes, Z., & Lengyel, I. (2017). Entrópia-dekompozíció és a vállalatok kapcsolati közelsége a hazai várostérségekben. Területi Statisztika, 57, 249–271.

- Teece, D. J., & Pisano, G. (1994). The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3, 537–556. doi: 10.1093/icc/3.3.537-a

- Tóth, G. (2014). Az agglomerációk, településegyüttesek lehatárolásának eredményei. Területi Statisztika, 54, 289–299.

- Young, S., Hood, N., & Peters, E. (1994). Multinational enterprises and regional economic development. Regional Studies, 28, 657–677. doi: 10.1080/00343409412331348566

- Zenka, J., Novotny, J., & Csank, P. (2014). Regional competitiveness in central European countries: In search of a useful conceptual framework. European Planning Studies, 22, 164–183. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.731042

- Zhu, S., Jin, W., & He, C. (2019). On evolutionary economic geography: A literature review using bibliometric analysis. European Planning Studies, 27, 639–660. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1568395.