ABSTRACT

In this paper, we use the notion social innovation to shed light on the complex interrelations between the emergence and consolidation of new policy approaches and their geographical mobility. Empirically, the paper deals with learning region policies in Germany, which epitomize a shift of the main approach from ‘catching up’ to ‘reflexive experimentation’ during the 1980s/1990s in Germany. We highlight the nature of social innovations in spatial planning as complex assemblages of material, organizational and conceptual elements. These elements are not necessarily new themselves. Rather, the novelty lies in the unprecedented ways, in which these elements are re-combined. From an innovation perspective, the unfolding of the learning region policy model co-evolves with the growth and proliferation of a related professional community of practice. Longitudinal data covering the whole innovation process is analysed in combination with case study material from two recent instantiations of the respective policies: the REGIONALE 2016 Westmünsterland and the ‘Competition Impulse Regions’ in Saxony.

1. Introduction: problem statement

The making of a good plan involves the appreciation of the idiosyncrasies of place and sensitivity to the historical heritage. A well-crafted plan, in other words, should be historically and locally unique. However, a broader view across planning practices at many places and throughout longer phases of planning history unveils patterns of similarity. What becomes apparent are recurrent ‘governance arrangements’ or emergent (and retreating) ‘policy models’. This paper is concerned with such ‘strangely familiar' (Temenos & McCann, Citation2013, p. 344) instantiations of planning practices at different times and places. We link up with and seek to contribute to the literature on policy mobilities by exploring in how far the notion ‘social innovation’ sheds more light into the complex interrelations between the emergence of new approaches and their geographical mobility.

Most accounts in the policy mobility debate address mobile practices as ‘models’. Novelty is mainly interpreted in terms of adaptation or adjustment of already existing models to the particular local circumstances at the multiple destinations they are transferred to (e.g. Peck & Theodore, Citation2012). In contrast, the innovation framework advanced here suggests a shift of focus from the spatial diffusion of existing models to the interrelations between the unfolding of a new idea and its repeated instantiation at multiple places. Novelty and movement, we argue, do not occur successively. Rather, learning about a model and its spatial mobilization are simultaneous and co-constitutive processes. Ideas, in other words, emerge and consolidate ‘through’ travelling.

Policies can practically never exist independently from place, organizations and actors. Rather, throughout the whole process the related expertize is and remains locally situated and historically contingent (Temenos & McCann, Citation2013). If this is true, the very idea of a ‘model’ becomes problematic. The question then is: How can policy ‘models’ exist at all? And if they exist, where can they be located? We seek to advance this part of the debate by focusing on ‘professional communities’ (Amin & Roberts, Citation2008; Healey, Citation2013; Müller & Ibert, Citation2015). Along the lines of the innovation framework, we will argue, that new policies typically co-evolve with a related professional community. Models, thus, do not exist as discrete entities, but resemble expertize that is dynamically preserved, frequently re-instantiated and variegated in divergent local and historical contexts by professional communities.

Policy mobility is portrayed to be strongly shaped by dominant political powers and mainly serves the interests of powerful elites (Peck & Theodore, Citation2015). Professionals are delegated to the role of mere ‘technocrats’ who distribute policy models across the globe and support the enforcement of a neoliberal agenda (Larner & Laurie, Citation2010). However, such accounts overlook the capabilities, and readiness, of professionals to proactively create, or at least influence their working conditions according to their own professional standards. At least within communities of professional planners, these standards hardly fit into a neoliberal agenda. Rather, planning professionals frequently mobilize values such as deliberation, sustainability or the public good. The innovation framework focuses stronger on the widely understated agency aspects involved in mobilizing policies and puts a stronger emphasis on the proactive role of experts and their intrinsic motivations in these processes.

In line with these considerations, we will examine the following research questions: (1) In how far can novel policy approaches be understood as innovations? (2) What is the relationship between learning and mobility? (3) How can policy models be understood and where can they be located? (4) What is the role of idealistic professionals in mobilizing policies?Footnote1

Empirically we will focus on a major shift in the field of regional development policies that have taken place during the past three decades in Germany. In essence, this shift was one from ‘catching up’ to ‘reflexive experimentation’. Our research revealed that despite most practitioners can agree on which single ‘practices’ constitute the novel approach in regional development policies they still lack an established common terminology to designate the ‘assemblage of practices as a whole’. As one interviewed expert put it:

I don’t know the ideal term to hallmark what I see. This could be one achievement of your project. There is definitely a shift away from this policy of catching up towards an augmented spectrum (I-5).

We thus borrowed the notion ‘learning region’ (Florida, Citation1995; Hassink, Citation2001; Morgan, Citation1997) from the literature to denote the novel practices we are concerned with.Footnote2 In our reading, ‘learning region’ is distinctive from other territorial innovation models (Moulaert & Sekia, Citation2003) in the sense that it focuses on the problems of regions that suffer from lock-ins instead of seeking to learn from the success stories of strong regions (Fürst, Citation2001; Hassink, Citation2001; Morgan, Citation1997). However, only few practitioners in the field (e.g. Stein, Citation2006) use this term frequently.

In the following section, we will situate our approach into the present discourse and develop our theoretical understanding of policy innovations and their embeddedness in professional communities. After a short account of the research design, we scrutinize different phases in the co-evolutionary social process in which an unfolding innovation interacts with an emergent professional community.

2. Situating social innovations in the policy mobilities debate

In the following sub-sections we do not only review the strands of literature we wish to contribute to, but also frequently draw connections to the empirical field we labelled as learning region policies. We do so, first, to illustrate the conceptual ideas more effectively, second to substantiate the connections of the approach to the discussed concepts, and third, to stepwise introduce our understanding of learning region policies to the reader.

Fundamental shifts in practices of spatial planning can be interpreted as ‘social innovations’ (Christmann, Ibert, Jessen, & Walther, Citation2017, Citation2019). Along with Schumpeter, we understand innovations as novel combinations that have become consequential in practice (Schumpeter, Citation1911). Hence, innovations are more than just new ideas. Another necessary condition is that they have to be integrated into social practices and thus have to be valued as useful by other practitioners. With the prefix ‘social’ we do not suggest that innovations should be allocated to discrete sectors (like ‘market’ or ‘technology’). Rather, new ‘social practices’, such as policy innovations, embrace new (and existing) technologies and also take into account economic aspects (even if not striving for profits; see also Domanski et al., Citation2019).

When applying the term social innovation to the field of spatial planning the question arises how the two main features of an innovation, ‘novelty’ and ‘usefulness for practice’ can be made operational. We use a social-constructivist approach (Christmann et al., Citation2017, Citation2019) by analysing how practitioners and observers who belong to the field assess the respective shifts in practice. Innovation can be specified as changes in professional practices that are claimed to be ‘novel’ or ‘innovative’ by field representatives. In this approach, innovations are discursively constructed by contrasting novel practices against the background of an alleged state of the art. Further, innovations denote discrepancies between ‘traditional’ and ‘new’ with a disruptive quality. Along these lines, learning region policies can be classified as ‘novel’ as they represent a shift in strategies of regional development policies from ‘catching up’ to ‘exploring new development paths’.

The social-constructivist approach towards social innovation inevitably touches upon normative issues (Moulaert, Jessop, Hulgård, & Hamdouch, Citation2013). Practitioners do not only assess the ‘novelty’ of a solution, but also make judgements about its ‘practical value’. Participants do so by mobilizing professional standards and by confronting the respective innovations with these norms and values. In the case of learning region policies ‘long-term orientation’ and the ‘willingness of municipalities to cooperate’ across administrative boundaries have been important criteria for professionals when promoting or defending the respective innovation. These norms widely reflect the professional identities of spatial planners vis à vis political actors who tend to think in legislative terms and are perceived to overstate the interests of the territory they represent.

2.1. Mobile policy models and social innovations as assemblages

In the discourse on policy mobilities policies are understood as ‘assemblages’ (Allen & Cochrane, Citation2007; Anderson & McFarlane, Citation2011; McCann & Ward, Citation2012a, Citation2012b), contestable combinations of heterogeneous bundles of knowledge and techniques purposefully gathered together for particular reasons and adapted to particular (local) conditions (Temenos & McCann, Citation2013). As assemblages ‘policies rarely travel as complete packages, they move in ‘bits’ and ‘pieces’ – as selective discourses, inchoate ideas and synthesised models' (Peck & Theodore, Citation2010, p. 170). Thereby some elements can be regarded as ‘constitutive’ (Roy, Citation2012) while others are facultative.

Learning region policies are a good case to illustrate this idea. The novelty of this approach can be understood as a recombination of diverse pre-existing elements (pieces of expertize, regulation and institutional capacities), some taken from near and others from far (see McCann & Ward, Citation2012b, p. 328). The following ‘constitutive’ (Roy, Citation2012) elements are frequently reassembled in order to pursue learning region policies (Füg, Citation2015; Fürst, Citation2001; Ganser, Siebel, & Sieverts, Citation1993; Hassink, Citation2001; Siebel, Ibert, & Mayer, Citation1999; Stein, Citation2006):

- Campaigning: Learning region policies aim at creating long term visions for regions, which are then operationalized incrementally in a series of interconnected projects.

- Extended spectrum of involved actors: Actors from different societal spheres (public, private and civic) work together in the formulation and implementation of these policies.

- Integrated approaches. Overcoming of sectoral policies and disciplinary boundaries.

- Mobilizing external expertize. Mobilizing ‘strangers’ and learning from their external views on the region.

- Competitive modes of governance: Mobilizing project proposals through open calls and granting funds according to quality criteria.

Not always, but often we observe the following facultative elements:

- Problem-based rescaling: Policies enact spaces according to the geographical extension of the addressed problems thereby overstepping territorial administrative boundaries.

- Intermediary agencies: Regional development agencies that combine the logics of public administration, private enterprises and civil society drive the process.

- Festivalization: Learning region policies are eventful, the results are communicated widely, and public attention is mobilized (Siebel, Citation2015).

Along with the policy mobilities discours, we appreciate that these models ‘evolve through mobility' (Peck & Theodore, Citation2010, p. 170) and morph and mutate as they travel (McCann & Ward, Citation2012b). Policies are thus subject to interpretation and reinterpretation in a socio-spatial process. Clarke distinguishes a topographical and topological understanding of ‘mobility’ (Clarke, Citation2012). The former denotes movements of concepts across the absolute space, while the latter focuses on the similarities and dissimilarities of local practices across different sites. When policies move they do so in topological and topographical space simultaneously.

Most contributors, however, seem to be mainly concerned with interrogating how ‘existing’ policy models are adapted (and thereby modified) to ‘existing’ local contexts. The origins of the model and the creative process through which heterogeneous techniques and concepts are assembled to ‘novel’ policy models often remain outside the scope of the analysis. Furthermore, the contingencies, contestations and frictions in the process of establishing such models in practice remain obscure (Temenos & McCann, Citation2013).

2.2. On travelling technocrats and professional communities of practice

The mobility of policies is understood as an active, purposeful and interest-driven process pushed forward by powerful political stakeholders and enacted by a new elite of ‘travelling technocrats’ (Larner & Laurie, Citation2010). At the local level, it is facilitated by mid-level technocrats who co-create locally specific instantiations of globally circulating policies in their respective settings (Larner & Laurie, Citation2010; Roy, Citation2012; Wood, Citation2014).

Policies travel most easily as trimmed and standardized models (Temenos & McCann, Citation2012, p. 1393). Mobility thus depends on ‘essentialising and delocalising policy programmes, converting them into “how-to” manuals of policy implementation' (Prince, Citation2010, p. 171). This has given rise to an accelerated circulation of models during ‘which policymakers stop thinking for themselves and instead rely on the achievements of their counterparts elsewhere' (Wood, Citation2015, p. 208).

We argue the depicted actors and mechanisms of transfer are not sufficient to fully understand how something like a model with validity at different times and places can emerge: ‘There is no cloud of free-floating policies hovering in the ether, waiting to be selected on the basis of “perfect information”' (McCann & Ward, Citation2012b, p. 327). Thus it becomes necessary to consider, how models are related to professional communities, how community members share, cultivate and variegate these models and how both, models and communities co-evolve.

A professional community is a sub-category of the more general notion of community of practice (Amin & Roberts, Citation2008; Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Communities of practice encompass people who participate in the same practice and follow common rules when performing this practice (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Wenger, Citation1998). Within communities, practitioners use and advance the shared pool of knowledge by interacting with peers and colleagues. Newcomers are integrated in existing communities by obtaining positions of ‘legitimate peripheral participation’ (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Experienced members thus share their expertize freely and – at least initially – without the expectation of reciprocity (Belk, Citation2010).

In ‘professional’ communities (e.g. lawyers or medical professionals) members have acquired a formal academic education. More crucially, the acquired abstract knowledge becomes more sophisticated through reiterated use in practice. Both criteria, formal education and the necessity to collect rich experiences in practice apply to planning practitioners. Along these lines, a community encompasses ‘professional enquirers who make up the field of scholarship and practical engagement associated with planning as a project for shaping urban and regional/territorial futures' (Healey, Citation2013, p. 189). Members might differ with respect to their organizational affiliations but share in common that ‘they are doing work of some kind in a governance context’ (Healey, Citation2013, p. 196) related to spatial development.

The community of practice approach offers a conceptual framework for understanding how models emerge and become common among practitioners. For instance, communities circulate objects and share documents, blueprints or photographs and thereby make available the inscribed or codified knowledge for members. The circulation of ideas is enabled through personal mobility, for instance, by visiting iconic places (Faulconbridge, Citation2010; Wood, Citation2015).

However, these mechanisms of learning alone are not sufficient to promote a shared understanding. Most importantly, these practices are embedded in an ongoing process of ‘mutual engagement’ (Wenger, Citation1998). The continuous telling of ‘war stories’ (Brown & Duguid, Citation1991) – real life accounts of how practitioners handled challenging situations – have frequently been observed among planners (Forester, Citation1999). By jointly scrutinizing the details of practical instances community members negotiate which of these elements are crucial to establish a shared practice and which represent only local idiosyncrasies (Grabher & Ibert, Citation2014). As long as relevant aspects in the conditions at distant places are sufficiently similar, it is possible to share practice without necessarily being personally present at the same location (Brown & Duguid, Citation2001) – the ‘topological dimension’ of policy mobility (Clarke, Citation2012).

By thinking social innovation in conjunction with the community perspective the agency of participants becomes more accessible for empirical analysis. Professionals are no longer delegated into the over-determined role of a vicarious agent (the travelling technocrat) of a neoliberal policy agenda, but come back as entrepreneurial and inventive social actors with professional identities, own agendas and a degree of freedom to make (or reject) choices.

3. Research design

The presented study is part of a greater research project, in which the emergence and unfolding of innovations in spatial planning is studied in four different domains of spatial planning (see Footnote 1). From 2013 to 2016 four empirical investigations have been conducted in parallel following a similar research design to afford comparison across these domains. In this paper, we focus on only one of the four areas: regional innovation policies. As all other studies in the project, it is based on longitudinal data that covers the whole process from a pre-conceptual state until establishment.

In our research, we combined forward and backward working types of longitudinal data analysis (McCann & Ward, Citation2012a, p. 46). The ‘forward working strategy’ is about identifying a policy’s origin and reconstructing the process from there until today. Longitudinal data is collected along with an ‘innovation biography’ (Butzin & Widmaier, Citation2016). The ‘backward working strategy’ starts from recent instantiations of learning region policies. It provides a comparison between two embedded cases (Yin, Citation2014) of recent instantiations of learning region policies. The cases represent a theoretically relevant contrast: The first case, the ‘Zukunftsland REGIONALE 2016' in the Westmünsterland region in North Rhine-Westphalia, represents a case in geographical and institutional proximity to the place of origin. It is the eighth (and probably last) of a series of events that have been coordinated by the Ministry of Urban Development in North Rhine-Westphalia from 2000 to 2016. Hence, actors could draw on rich previous experiences. The second case, the ‘Competition Impulse Regions' in Saxony is characterized by geographical and institutional distance to the place of origin. While the initial experiences with learning region policies have been made in the Western part of Germany, Saxony is the easternmost federal state in Germany. In institutional terms, after the German reunification in 1990, the re-establishment of the federal state of Saxony was a disruptive event.

The study draws on two sets of data: First, a ‘document analysis’ has been conducted based on a systematically assembled compilation of journal articles to capture the professional and scientific discourse from 1975 to 2014. The selected journals cover the disciplines of planning, geography, political science and regional economics, and target academics as well as practitioners and policy makers. In addition, the analysis includes key monographs, edited volumes and legislative documents. Results of the discourse analysis have been published elsewhere (Füg, Citation2015).

The second set of data consists of 23 ‘expert interviews’ with 27 interviewees. Ten of these interviews encompass prominent commentators, observers and participants of the discourses on learning region policies in Germany (in the following coded as I-1–10). We analysed these data in combination with data obtained in the course of the discourse analysis to reconstruct the innovation biography. The experts answered to questions about the content of the innovation, its elements and linkages between these elements, the temporal order of events from the origin of the idea until today, involved places, individual and collective actors and the influence of different discourses at different times.

The case studies comprise seven interviews with eight interviewees related to the REGIONALE 2016 (coded as N-1–7) and six interviews with nine interviewees in Saxony (S-1–6). Interviewees work for public administrations at the municipal and federal state level, for regional development agencies or were involved in the selection, qualification or development of projects. Unlike the first series of interviews, the case-study interviews took the actual regional situation as a starting point and sought to appreciate the specificities of the cases. Further questions aimed at unveiling linkages to past experiences that were mobilized in order to launch the respective programmes.

4. The emergence and consolidation of learning region policies in Germany

In this section, we seek to elucidate the connection between an emergent innovation, its unfolding and consolidation on the one hand and the process of community formation on the other. The analysis proceeds in four steps, starting with the pre-conceptual state, in which the innovation is in a state of ‘latency’ (4.1) and proceeding to first-time ‘generation’ (4.2), to developing promising ‘formats’ (4.3) and eventually terminating with the ‘stabilization’ of the innovation (4.4) (Ibert, Christmann, Jessen, & Walther, Citation2015). For each phase, we first, analyse how the innovation is materialized as assemblage (consisting of elements and linkages) and second, how this materialization is embedded in professional communities. For both levels of analysis, we consider issues of spatial distribution and mobility.

4.1. Latency: Intersecting communities gathering around a shared problem

Disruptive changes emerge in historical settings in which ‘time is ripe’ (Barnes, Citation2018). During the late 1970s and early 1980s time was indeed ripe for something new in regional development policies. The historical background was the persistent crisis of the old industrial regions in Europe. In Germany, it was in particular the experiences with the Ruhr Area, which lead to the slowly emerging recognition that these regions were facing a deep structural crisis rather than just another temporary economic downturn (I-1–2; I-5; I-8).

Until then structural policies were widely concerned with moving the regions forward on a development path towards industrialization. In the light of the sustained economic crisis of the formerly most advanced regions, in particular, the Ruhr Area, this ‘linear development model’ (Freytag & Windelberg, Citation1978) was questioned. Further, regional economists plead for an ‘innovation-oriented regional policy’ (Ewers & Wettmann, Citation1980). At about the same time ‘human and economic geographers’ started to reinvigorate the cultural foundations of regions highlighting the endogenous resources as so far underestimated drivers of economic development (I-6). Drawing on international research on innovative milieus (Camagni, Citation1991), the German discourse soon shifted the attention from the successful regions, like the Third Italy (Piore & Sabel, Citation1984) or Baden-Württemberg, towards the problematic cases (Grabher, Citation1988, Citation1993; Läpple, Citation1986)

We have to investigate non-innovative milieus: which persistent structures are blocking things? Explaining a successful region is somewhat redundant - or doesn’t bring us any further (I-8).

A third discourse, advanced by political and social scientists, addressed the changing role of the state in shaping development conditions: Cooperative forms (Ritter, Citation1979) complement the traditionally hierarchical relationship between state and society. Diminishing tax revenues give rise to public–private partnerships (Hesse & Zöpel, Citation1990). Integrated approaches replace or complement classical sectoral policies (Hassink, Citation2001). Established ways of scaling policies are criticized as inappropriate to address problems that enact their own spatiality (Blotevogel, Citation1998). In hindsight, all these strands of discussion culminate in a discussion about a shift in state intervention from ‘government’ to ‘governance’ (Mayntz, Citation2004).

4.1.1. Assemblages: fragmented local initiatives

Against this background, local initiatives started to experiment with new policy approaches for regional development. Many elements of the later innovation were already there, yet they remained disconnected. In North Rhine-Westphalia, two successive initiatives undertaken by the state government for the ‘Future of old industrial regions' (ZIM) in 1987 and for the ‘Future of regions in North Rhine-Westphalia' (ZIN) in 1989 had an important ‘preparatory function’ (I-1) for learning region policy approaches. In particular, these initiatives promoted the bottom-up formulation of regionally specific development strategies, stimulated cooperation across municipal boundaries, and deliberative forms of integrating a wide range of private actors in development policies (Prognos, Citation2016).

At about the same time, regional conferences experimented with integrated planning modes in parts of Lower Saxony in Northern Germany (Danielzyk, Citation1994) but also in Switzerland and Austria (e.g. Grabher, Citation1988; Lutzky & Wettmann, Citation1982). For different reasons these experiments were not fully convincing (Prognos, Citation2016, p. 105ff): They did not spur enough innovative projects; they failed to integrate stakeholders beyond the political-administrative sphere and often re-enacted existing administrative boundaries rather than establishing rescaled territories in accordance to the geography of the developmental problems.

4.1.2. Communities: separate practices, joint interest, overlapping discourses

During this phase, professional planners find themselves under pressure. The traditional repertoire of practices, like investing in hard infrastructures or improving the conditions for external investors, has proven to be no longer sufficient to mitigate the crisis.

Academic researchers who have a strong ability to translate academic insight into politically and practically relevant knowledge participated in almost all of the early local experiments (I-6; I-8; I-1). The interpenetration of academic and planning practices took place at public events during this early stage, for instance, a series of working group meetings held in the Ruhr Area during the mid 1980s (I-2; I-6). Experts, who started their careers in academia, eventually became decision makers in key administrative bodies. Karl Ganser is a case in point, who started his career as a human geographer at the Technical University Munich in the 1960s, worked for the Federal Institute of Regional Studies and Planning during the 1970s before becoming head of the department in the North Rhine-Westphalian Ministry for Regional and Urban Planning in the 1980s.

An increasing number of professional planners, most of whom belonging to a younger generation, became excited about these then novel views on the crisis of old industrial regions. The idea of learning region policies was in the air, yet remained latent:

All that has been undertaken so far reached limits. And it became clear that one needs to go beyond these limits – but not exactly in which direction (I-2; similarly: I-5).

4.2. Generation: emergent novel policies and a local boundary practice

Most interviewees regard the International Building Exhibition (IBA) Emscher Park, a development programme for the Northern part of the Ruhr Area coordinated by the federal state Ministry of Regional and Urban Development from 1989 to 1999 as a prototypical instantiation of the novel practice and as a critical breakthrough (Ganser et al., Citation1993). It addressed several key issues of learning region policies that so far had remained unresolved by creating associations between key elements of learning region policies for the first time.

4.2.1. Assemblages: first interlinkages of key elements

Unlike most predecessors, the IBA found a way for stimulating projects with an innovative edge by combining elements of competition with instruments for the qualification of project ideas (Siebel et al., Citation1999). The IBA started with an open call for projects and installed a board of trustees to select the most promising proposals submitted by regional stakeholders from the public and private sectors and from civil society. Moreover, the IBA found a way to stimulate inter-municipal cooperation at the regional scale. Having been an organization owned by the federal state, all municipalities accepted its authority and legitimacy. This new way of distributing responsibility across multiple administrative levels and political scales (referred to as ‘centralisation' by interviewee I-4 and I-5) was crucial to overcome short-sighted controversies among municipalities and to enable inter-municipal cooperation and cooperative project design from bottom-up. Furthermore, it became possible to establish a region that mirrors the geography of the structural problems of the declining old industrial region (I-4) irrespective of existing administrative boundaries.

More importantly, the IBA Planning Company was founded, a privately organised development agency in public ownership, with the already mentioned Karl Ganser as a managing director. It was compulsory for awarded projects to involve representatives of the IBA Planning Company in project development. It was thus possible to qualify all of the about 100 selected projects from their beginning to completion. The IBA Planning Company staged the restructuring programme as a series of events, with an interim and a final presentation in 1994 and 1999 and manifold project-related festivities. This ‘festivalisation’ (Siebel, Citation2015) has been instrumental for increasing the motivation of all participants to achieve outcomes beyond the routine (Ibert, Citation2003).

4.2.2. Communities: collaborating across boundaries, emergent shared local practices

The Ruhr Area provided an almost ideal-typical situation to explore the problem of regional ‘lock-ins’ (Grabher, Citation1993) in all its dimensions. First, the so far predominant approach was already weakened due to a long standing track record of first hand experiences with ‘bad practices’ (Grabher & Thiel, Citation2015). Interviewees describe the situation as one of despair and frustration and the political leaders were already ‘with their backs to the wall' (I-5, similarly I-2). Second, the local scene of planners in the Ruhr Area already encompassed a critical mass of potential allies ready to appreciate new ideas that elsewhere would have had little chances of being taken serious (I-4; I-6). Third, international field trips to regions with similar problems (e.g. North West England, France) and subsequent return visits sensitized the regional scene of planning practitioners to the nature of the development problem (I-5). Fourth, the IBA would have been impossible without ‘political patronage’ (Christmann et al., Citation2019). The popular prime minister of North Rhine-Westphalia, Johannes Rau was ‘holding his hand over it, fatherly' (I-8; similarly: I-1).

The first prototypical instantiation of a learning region policy, in other words, co-evolved with an emergent local community of practice consisting of planning practitioners, academics, politicians and local allies. The shared practice crystallized around the IBA planning company. With the board of scientific directors, five leading proponents of relevant academic discourses became affiliated part-time with the IBA. The scientific directors were involved in qualifying projects and thus were part of the mutual engagement of an emergent ‘boundary practice' (Wenger, Citation1998, p. 113) at the intersection of formerly separated practices.

4.3. Formatting: from local to a trans-local boundary practices

The mid 1990ies can be interpreted as another turning point. Learning dynamics shifted from implementing a novel idea for the first time to finding ways of re-enacting it under varying circumstances (‘formatting’).

4.3.1. Assemblages: detecting and developing mobile elements

Interaction among practitioners increasingly became concerned with developing a shared repertoire of more permanent resources. Participants sought to consolidate a joint terminology and to codify essentials of the planning strategy in a series of papers published in journals that address audiences at the interface between academia and planning practice, like ‘RaumPlanung’ (e.g. Ganser et al., Citation1993) or ‘Informationen zur Raumentwicklung’ (e.g. Läpple, Citation1986; Siebel et al., Citation1999). Here the authors identified key elements, of learning region policies as for instance, ‘project’, ‘development agency’, ‘competition’ and ‘rescaling’ and explore their interrelatedness. The scientific directors of the IBA published an edited volume (Kreibich, Schmid, Siebel, Sieverts, & Zlonicky, Citation1994), in which they reflect on experiences made during the first five years of the IBA Emscher Park (Häußermann & Siebel, Citation1994). Soon textbooks were published that extract lessons learnt from vanguard projects (e.g. Beierlorzer et al., Citation1998).

Such and other ‘bits and pieces' (Peck & Theodore, Citation2010, p. 170) of practices established during the early 1990s have been taken over in follow-up policies. This ‘upscaling’ was more consequential for the design of policy programmes while it had hardly any impact on legislative initiatives. Many of the key features of the approach – the temporality of the intervention, the association with festivals, the valuation of endogenous regional resources and the voluntary participation of stakeholders – turned out to be difficult if not impossible to mobilize via the law (I-4; I-5).

Within North Rhine-Westphalia, learning region policies have been taken up and developed further within several ministries. The REGIONALE programme (Beierlorzer, Citation2010), a follow-up programme that spurred a series of regional development initiatives in North Rhine-Westphalia from 2000 to 2016, was led by the ministry of urban affairs. Other federal states outside North Rhine-Westphalia followed and organised similar initiatives (e.g. IBA ‘Urban Regeneration' Saxony-Anhalt 2010; IBA ‘Fürst-Pückler-Land' in Brandenburg).

4.3.2. Community: from local to trans-local professional community

In this phase the professional community increasingly became trans-local. Travelling experts, for example, the IBA scientific directors, were one important driver of this process. More importantly, fieldtrips by students and planning practitioners to the Northern Ruhr Area, including site visits and personal meetings with project staff, accelerated the pace of circulating ideas. Successful practitioners who collected first hand experiences in the second row during early instantiations of the policy have been hired into leading positions in follow-up events outside the Ruhr Area (I-5). The excitement about the IBA from outside the region stands in strange contrast to the growing dissatisfaction about the results and heritage of IBA within the Ruhr Area. In the process of a shared local boundary practice becoming a trans-local community, the place of origin is ‘mystified’ (Honeck, Citation2016).

In summary, formatting and travelling are observed as co-constitutive processes. The model travelled foremost and easier to regions with similar structural problems and to regions that are close in political terms (e.g. the Saar region). Only subsequently, the learning region approach was adopted in regions that were more dissimilar in terms of institutional settings, political power constellations and socio-economic structures (Saxony-Anhalt; Brandenburg; most recently Thuringia). The process of creating a model out of a series of one-off endeavours took place through the repeated instantiations in increasingly divergent contexts.

4.4. Stabilization and adjustment: between consolidation and pragmatism

In this section, we zoom into two recent instantiations of learning region policies: the ‘Zukunftsland REGIONALE 2016’ and the ‘Competition Impulse Regions'. Both comprise key elements of learning region policies yet representing rather distinct trajectories.

4.4.1. Assemblages: different versions, same idea?

In both cases, the element of ‘campaigning’ can be identified. In Westmünsterland, a region that has successfully and ‘silently’ (Hassink, Citation2007) managed the structural change from a textile region to a wealthy rural region, ten key questions concerning future development options have been raised and serve as organizing principle for concrete development projects at the beginning of the initiative (N-2; N-4). Regional actors proactively tackle challenges such as future mobility in rural areas, demographic shrinkage or shortage of skilled labour forces before they become manifest as problems as the name ‘Zukunftsland' (= land of the future) suggests:

There is no compulsory demand for structural policy, only if you look into the future. This region will face problems due to demographic development in the coming years (N-1).

We are possibly a space for experimentation and can try out things (…) (N-2).

Responding to these challenges, projects include the modernization of the outlying rural district Wulfen-Barkenberg, the customization of intermodal mobility infrastructure, with the implementation of cargo bikes at bus stops in the project ‘MOVIE', or ‘PUSH Münsterland', a knowledge transfer network of small and medium sized businesses targeting key value chains in the region.

The awarded Saxon regions are concerned with similar problems: demographic change, strengthening centres in peripheral regions, employment opportunities in rural areas (S-2). However, here the campaigning approach is less proactive, as these problems became manifest already back in the late 1990s. Compared to the Westmünsterland, the Impulse Regions are not about playful experimentation, but are based on political demand to offer funding for pressuring issues:

The question that came up, especially from the municipalities, was: Can’t you […] fund specific implementation projects, investments, so to say (S-1).

Implemented activities are, for example, a regional marketing campaign, a shared vehicle as ‘citizens bus’ for rudimentary public transport that is used by the youth soccer team to travel to weekend-tournaments, or the funding of a position as ‘mediator’ to improve the inclusion of Eastern European workers in the border region between Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic.

Further, both cases are comparable in the decision makers’ willingness to systematically ‘expand the spectrum of actors’ beyond the public and administrative sphere in regional development policies. Interviewees mention providers of mobility services in both cases. In addition they name economic actors, churches and civil society groups (N-4) in the case of Westmünsterland or health services (S-6b) in the case of the awarded Impulse Region North Saxony. Similarly, the mobilization of ‘external expertize’ was a key mechanism to spur new ideas in both cases at the level of projects and programmes. Furthermore, the aspiration to provide ‘integrated solutions’ is expressed prominently in official documents and by interviewees in both cases. Both federal states set up inter-ministerial working groups to advise projects about funding possibilities (S-2; N-4).

Both cases offer vivid examples of introducing ‘competitive modes of governance’ in regional development policies. The prospect to get first priority in funding schemes of the respective federal states serves as an important incentive to participate in the competition. Moreover, awarded projects gain reputation and are thus strengthened for applications for European funds. In the REGIONALE 2016 case, inter-regional competition was weak. After seven rounds of funding in the REGIONALE scheme, Westmünsterland was the last ‘white spot' (N-5) left on the map that did not yet get funding from the programme (also: I-4). However, intra-regional competition between project proposals is intense. Every proposal goes through a three step selection procedure in which it is evaluated and further qualified with the help of an inter-ministerial commission and the project agency. In the Saxon case, the inter-regional competition is more pronounced as only four regions got awarded as Impulse Regions (S-2). However, once a region has been granted an award, projects were no longer selected according to quality criteria. As a consequence, the participating municipalities were allowed to distribute funds equally within the regions (S-6a/b).

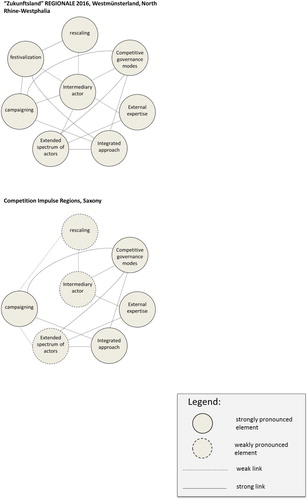

The facultative elements in assemblages of learning region policies can all be identified in the REGIONALE 2016 case but only partly in Saxony. ‘Festivalization’, for instance, is of some relevance in the Westmünsterland region (final presentation of project results in April 2016), but absent in the Saxon case. The ‘rescaling of territories’ was much more pronounced in Westmünsterland, a region covering two counties and some municipalities. Some observers criticize these delimitations as somewhat ‘artificial' (N-5) while others acknowledge the opportunity to reinvent a newly demarcated space (N-3; N-4). In the Saxon case, rescaling is nothing explicitly excluded, yet in practice three of the four awarded regions are identical with existing counties (‘Landkreise'; S-2). Likewise in the REGIONALE case, an intermediary agency is in charge of managing the whole process while in Saxony participants manage the process from within the existing ministerial administration.

We said right from the beginning, that the effort must be limited. […] Since the regions are relatively small, […] we said that there is no need for an additional organisation (S-2).

However, an independent jury with external experts was nominated as an additional structure to make the decision about the regions to be awarded. Unlike the REGIONALE Development Agency, which was in charge of managing the whole development process, the jury dissolved after the decision about the awards had been made. Subsequently, the county administrations (Landkreise) took over again the leading role as units of operational management and programme implementation.

Both cases do not only differ with respect to the number of observable elements but, more crucially, also in terms of the linkages between elements (see ). For instance, in Westmünsterland the regional savings bank (‘Sparkasse') is not only included in single projects, but is strongly integrated as a private shareholder of the regional development agency. This strong commitment was motivated by the fact that the newly defined region overlaps significantly with the recently reorganized network of bank branches (N-3). Another case in point is the central role of the REGIONALE development agency which is interlinked with almost all elements in the assemblage. Such a density of linkages cannot be achieved by the jury of external experts that could be seen as the corresponding body on the Saxon side.

In short, both cases represent different instantiations of the learning region policy model. The REGIONALE 2016 is an example of an ambitious consolidation of the model that seeks to maintain core qualities and improve single elements. The Saxon case, in contrast, is an example of a selective adaptation to regional requirements and a re-instantiation on a more mundane level that is more suitable for integration into administrative routines.

4.4.2. Communities: trans-local professional community, unevenly distributed in space

When instantiating learning region policies, both regions could draw on a trans-local professional community of practice. The Westmünsterland region builds on more than two decades of practical experiences with learning region policies in North Rhine-Westfalia. The REGIONALE programme was a direct spin-off of the IBA Emscher Park and since 2000 there has been a final presentation of a REGIONALE every two (2000–2010) to three years (2013 and 2016) (Beierlorzer, Citation2010). The way of directing funding to the region was already explored during the IBA Emscher Park in the 1990s and the federal state administration today is used to work in informal inter-ministerial working groups to secure funding for integrated approaches within projects by combining several sectoral funding schemes (N-4; N-1a).

Saxony, in contrast, was re-established as a political and administrative entity after the reunification in 1990. Professional planners thus experienced a drastic restructuring of institutions and an almost complete exchange of personnel with many newly recruited staff from former Western Germany. Against this background, it is little astonishing that the first discussion about learning region approaches started some years later than in North Rhine-Westphalia. Interviewees recollect a series of workshops that were held in 1993–1996 with an explicit agenda to scan Western German experiences for implication for the situation in Saxony (e.g. Vaatz, Citation1997). The roots of the ‘Impulse Regions' can be traced back to ministerial directives in 1993 and 1997.

Given the low degree of institutionalization in this field and the limited possibilities for routinization, membership in the community is probably critical for the ability to enact complex renewal strategies in a region. Actors from both case studies share a similar set of practices, refer to a similar set of reference projects, share ideas about good and bad practices. In short, they belong to the same trans-local professional community of practice. However, both regions also show interesting differences in terms of the density and richness of the mutual engagement of community members. In North Rhine-Westphalia, well connected community members occupy positions in municipal administrations and in federal state ministries, while in Saxony the respective expertize is concentrated in the federal state administration alone. Furthermore, in North Rhine-Westphalia, the awareness is spread across adjacent policy sectors as well, e.g. economic affairs, ecology and agriculture. In Saxony, the same sectors are reported to be involved in the implementation of the programme. However, at the same time, they are also criticized for lacking understanding for the particularities of the approach (S-2). Finally, in North Rhine-Westphalia expertize related to learning region policies is also present in private consultancies (N-7). Public non-university research institutes in the region frequently conduct evaluative research studies (N-5). Both types of actors are not active in the Saxon case example. Instead, in Saxony events organised by national professional associations, like the Academy for Spatial Research and Planning (ARL) were the only way to enhance the influence of the trans-local professional community into this region (Vaatz, Citation1997).

The mutual engagement of practitioners is denser and richer in North Rhine-Westphalia. Frequent informal meetings between present and former directors of REGIONALE Development Agencies as well as informal meetings of leading staff augment the possibilities of sharing of experiences between different regions:

We were discussing again and again, adopt it to our needs, refine it, and experienced support again and again, what does not work, how can we put it into practice and so on. We also learned from negative examples. (N-2)

Within North Rhine-Westphalia practices of mutual site visits persist until today and an increasing number of accessible sites can be visited without much effort by curious practitioners (N-7). Subsequent REGIONALE events frequently recruit staff from their predecessors (N-2). They can thus build on long-term experiences with learning region policies despite the temporal character of the events. In Saxony, practitioners do also report about an exchange of ideas on a regular basis. However here, only few likeminded practitioners can be found in the own region. Sharing of ideas mainly includes staff of municipal and ministerial planning departments while representatives from other policy sectors and private consultancies are missing. Further, sharing of practice is more restricted to formalized formats of professional exchange at the national scale (S-2).

5. Conclusion

With this paper we set out to explore the following research questions in order to make theoretical contributions to inter-disciplinary debates on the mobility of policy models and on (social) innovations in the realm of spatial planning: (1) In how far can novel policy approaches be understood as innovations? (2) What is the relationship between learning and mobility? (3) How can policy models be understood and where can they be located? (4) What is the role of idealistic professionals in mobilizing policies?

Ad 1. Learning region policies can be understood as a social innovation in the field of spatial planning (Christmann, Citation2019). When explaining the novelty of the approach, our interviewees differentiate between ‘traditional’ policies of catching up along existing development paths in contrast to the novel approach of exploring new regional development trajectories. Moreover, learning region policies can be interpreted as innovations ‘in spatial planning’ in the sense that this mode of governance has not only been assessed in terms of its novelty, but also in terms of its value for practice. This valuation took place against the background of professional standards of planners who stress the necessity for inter-municipal cooperation, integrated approaches and the mobilization of endogenous resources. Furthermore, these novelties can also be understood as being socially constructed. Learning region policies have been described in terms of a complex ‘assemblage’ (Allen & Cochrane, Citation2007; Anderson & McFarlane, Citation2011; McCann & Ward, Citation2012a, Citation2012b). Not the single elements are novel but the newly established ways of linking them.

Ad 2. The social process of innovation has been described as one in which the gradual unfolding and consolidation of a new approach goes hand in hand with the emergence and proliferation of a (trans-)local professional community. Initially, time was ripe for something new in regional development policies, but no one was able to bring together all required elements in one location. Partly by historical coincidence, partly by intentional agency of entrepreneurial individuals, learning region policies took shape for the first time during the IBA Emscher Park in the Northern Ruhr Area before transferring it into other, more or less similar regions across Germany. Eventually, the model is consolidated (like in Westmünsterland) but also implemented in more pragmatic ways (like in Saxony). Throughout this process, initially a group of pioneers succeeded in mobilizing a local coalition of actors. Later on, early and late adopters join in and carry the new solution into their respective home regions. What started as a local ‘community of inquirers’ (Healey, Citation2013) performing an unprecedented boundary practice (Wenger, Citation1998) increasingly grew, branches out and turns from a local into a trans-local professional community. This view sheds new light on the relationship between the creation of a model and its mobility across divergent spatial contexts. Both, the policy mobilities strands and innovation studies implicitly assume that the creation and diffusion of novelty are successive steps. Our evidence from the field of learning region policies, in contrast, shows that creating a model takes place through mobilization. Unfolding and mobilizing ideas are thus co-constitutive practices and co-evolve throughout the entire process of innovation.

Ad 3. Against this background, models can be reinterpreted as a set of practices that are cultivated, developed further, and continually variegated in professional communities. This addresses a research gap in the policy mobilities literature, in which professional communities could function as a conceptual element that works like the proverbial social ‘ether’ (McCann & Ward, Citation2012b) in which models float. Learning region policies cannot be described as models in the strict sense of the word. Rather, the respective assemblages emerge out of local practices, are negotiated against the background of increasingly divergent contexts and are continually modified by a professional community. Thus similar sets of elements and links can be re-instantiated in several locations ‘as if’ following an abstract model. This suggests that new ideas have to travel in order to evolve into models.

Ad 4. Finally, it becomes clear that professionals do have agency in this process of mobilizing policy models. They are more than just ‘traveling technocrats’ (Larner & Laurie, Citation2010). Rather, they bring in their own values, ideals and agendas as professional planners when becoming excited about the new policies and propagating it in front of peers, decision makers or society more broadly. Learning region policies have been appreciated, valued, evaluated and driven mainly by idealistic professional planners – less so by politicians (with the notable exception of patrons), and most of them see them as part of a politically progressive project. In particular ‘social’ innovations are driven by enthusiasts and propagated openly by professionals with strong beliefs. The very fact that an idea is mobilized, thus, seems to be rather loosely connected to the nature of the underlying political agenda.

Our findings have to be interpreted with care, of course. Due to our research design, we did not further follow the international links (like international delegates, international publications) we encountered in the professional community. Thus international policy mobility remains underrepresented in our account but is, of course, the main focus in the debates on policies mobilities.

However, our findings also clearly show that the mobilization of policies ‘within’ a national territory is already a challenging task, in particular in federal states such as Germany. Further, our analysis showed that policy mobility might be stronger determined by territorial institutions than often assumed, in particular when these policies are innovative. The recent debate on policy mobilities, which advanced a ‘global-relational understanding of urban policy' (McCann & Ward, Citation2012a, p. 46), might understate the persistent influence of territorialized institutions for the circulation of policy models. For future research, it would thus be desirable to analyse processes of social innovations with an explicitly international research design.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under Grant IB 95/6-1. The project was part of a bigger project consortium. Empirical work has been conducted with a similar research design and in close cooperation with Gabriela Christmann (PI) and Thomas Honeck (Grant CH 864/3-1 on ‘temporary uses’); Johann Jessen (PI) and Daniela Zupan (Grant JE 202/6-1 on ‘compact, mixed-use urban neighbourhoods’) as well as Uwe-Jens Walther (PI) and Oliver Koczy (Grant 1591/6-1 on ‘neighbourhood management’). See also Christmann et al. (Citation2019).

2 It is important to note that in the German context the term ‘learning region’ is also used beyond the field of application we are concerned with here. For instance, an educational programme co-funded in 2001 by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and the European Social Fund for Germany (ESF) is called ‘Lernende Region’. It supports networks at the regional scale between different educational institutions in order to promote life-long learning. However, apart from addressing the regional scale it has little in common with the type of policies we are discussing bellow.

References

- Allen, J., & Cochrane, A. (2007). Beyond the territorial fix: Regional assemblages, politics and power. Regional Studies, 41(9), 1161–1175. doi: 10.1080/00343400701543348

- Amin, A., & Roberts, J. (2008). Knowing in action: Beyond communities of practice. Research Policy, 37(2), 353–369. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2007.11.003

- Anderson, B., & McFarlane, C. (2011). Assemblage and geography. Area, 43(2), 124–127. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2011.01004 doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2011.01004.x

- Barnes, T. J. (2018). A marginal man and his central contributions: The creative spaces of William (‘Wild Bill’) Bunge and American geography. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(8), 1697–1715. doi: 10.1177/0308518X17707524

- Beierlorzer, H. (2010). The Regionale. A regional approach to stabilizing structurally weak urban peripheries applied to the southern fringe of the metropolitan area Rhine-Ruhr. disP – The Planning Review, 46(181), 80–88. doi: 10.1080/02513625.2010.10557089

- Beierlorzer, H., Boll, J., Borghoff, B., Kübel-Sorger, A., Post, N., & Seineke, J. (1998). Einfach und selber bauen. Ein Handbuch zur Entwicklung von Selbstbausiedlungen [Simply do it yourself: A handbook on the development of self-constructed settlements]. Aachen: Landesinstitut für Bauwesen des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen.

- Belk, R. (2010). Sharing. The Journal of Consumer Research, 36(5), 715–734. doi: 10.1086/612649

- Blotevogel, H. H. (1998). The Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region: Reality and discourse. European Planning Studies, 6(4), 395–410. doi: 10.1080/09654319808720470

- Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities of practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning and innovation. Organization Science, 2(1), 40–57. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2.1.40

- Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (2001). Knowledge and organization: A social-practice perspective. Organization Science, 12(2), 198–213. doi: 10.1287/orsc.12.2.198.10116

- Butzin, A., & Widmaier, B. (2016). Exploring territorial knowledge dynamics through innovation biographies. Regional Studies, 50(2), 220–232. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.1001353

- Camagni, R. (1991). Innovation Networks: Spatial perspectives. London: Belhaven.

- Christmann, G. B., Ibert, O., Jessen, J., & Walther, U.-J. (2019). Towards the emergence of innovations in spatial planning. The social process of innovating – phases, actors, Conflicts. European Planning Studies. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1639399

- Christmann, G. B., Ibert, O., Jessen, J., & Walther, U. J. (2017). How does novelty enter spatial planning?: Conceptualizing innovations in planning and research strategies. In W. Rammert, A. Windeler, H. Koblauch, & M. Hutter (Eds.), Innovation society today. Perspectives, Fields, and cases (pp. 247–272). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Christmann, G. B. (2019). Introduction: Struggling with innovations – social innovations and conflicts in urban planning and development. European Planning Studies. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1639396

- Clarke, N. (2012). Urban policy mobility, anti-politics, and histories of the transnational municipal movement. Progress in Human Geography, 36(1), 25–43. doi: 10.1177/0309132511407952

- Danielzyk, R. (1994). Regionalisierung der Ökonomie – Regionalisierung der Politik in Niedersachsen. Zur Aktualität geographischer Regionalforschung [Regionalisation of the Economy – Regionalisation of the policy in Lower Saxony. About the relevance of Geographic regional research]. Berichte zur Deutschen Landeskunde, 68, 85–110.

- Domanski, D., Howaldt, J., & Kaletka, C. (2019). A comprehensive concept of social innovation and its implications for the local context – On the growing importance of social innovation ecosystems and infrastructures. European Planning Studies. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1639397

- Ewers, H.-J., & Wettmann, R. W. (1980). Innovation-oriented regional policy. Regional Studies, 14(3), 161–179. doi: 10.1080/09595238000185171

- Faulconbridge, J. (2010). Global architects. Learning and innovation through communities and constellations of practice. Environment and Planning A, 42(12), 2842–2858. doi: 10.1068/a4311

- Florida, R. (1995). Toward the learning region. Futures, 27(5), 527–536. doi: 10.1016/0016-3287(95)00021-N

- Forester, J. (1999). The deliberative practitioner: Encouraging participatory planning processes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Freytag, H. L., & Windelberg, J. (1978). Ein Ansatz für eine integrierte regionale Innovationsstrategie [An approach for an integrated regional innovation strategy]. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, 7, 527–534.

- Füg, F. (2015). Reflexive Regionalpolitik als soziale innovation. Vom Blick in die Sackgasse zur kollektiven regionalen Neuerfindung. [Reflexive regional policy as a social innovation: From the view into the dead end to collective regional reinvention]. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, (3), 245–259.

- Fürst, D. (2001). Die “learning region“ – Strategisches Konzept oder Artefakt? [The “learning region“ – strategic concept or artefact?]. In H.-F. Eckey, M. Junckernheinrich, H. Karl, N. Werbeck, & R. Wink (Eds.), Ordnungspolitik als konstruktive Antwort auf wirtschaftspolitische Herausforderungen [Regulatory policy as Constructive Response to Eeconomic political challenges] (pp. 71–89). Lucius & Lucius: Stuttgart.

- Ganser, K., Siebel, W., & Sieverts, T. (1993). Die Planungsstrategie der IBA Emscher Park. Eine Annäherung [The planning strategy of the IBA Emscher Park: An approximation]. RaumPlanung, 61, 112–118.

- Grabher, G. (1988). De-Industrialisierung oder Neo-Industrialisierung: Innovationsprozesse und Innovationspolitik in traditionellen Industrieregionen [De-Industrialization or Neo-Industrialization: Innovation processes and innovation policy in traditional industrial regions]. Berlin: Edition Sigma.

- Grabher, G. (1993). The embedded firm: On the socioeconomics of interfirm relations. London and New York: Routledge.

- Grabher, G., & Ibert, O. (2014). Distance as asset: Knowledge collaboration in hybrid virtual communities. Journal of Economic Geography, 14, 97–123. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbt014

- Grabher, G., & Thiel, J. (2015). Mobilizing action, incorporating doubt: London’s reflexive strategy of hosting the Olympic Games 2012. In G. Grabher, & J. Thiel (Eds.), Perspectives in Metropolitan research: Self-Induced Shocks: Mega-projects and Urban development (pp. 87–98). Berlin: Jovis.

- Hassink, R. (2001). The learning region: A fuzzy concept or a sound theoretical basis for modern regional innovation policies? Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 45(3–4), 219–230. doi: 10.1515/zfw.2001.0013

- Hassink, R. (2007). The Strength of weak lock-ins: The renewal of the Westmünsterland textile industry. Environment and Planning A, 39(5), 1147–1165. doi: 10.1068/a3848

- Häußermann, H., & Siebel, W. (1994). Wie organisiert man Innovationen in nichtinnovativen milieus? [How to organize innovations in non-innovative milieus?]. In R. Kreibich, A. S. Schmid, W. Siebel, T. Sieverts, & P. Zlonicky (Eds.), Bauplatz Zukunft: Dispute über die Entwicklung von Industrieregionen [Construction site future: Disputes over the development of industrial regions] (pp. 52–64). Essen: Fuldaer Verlagsanstalt.

- Healey, P. (2013). Circuits of knowledge and techniques: The transnational flow of planning ideas and practices. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), 1510–1526. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12044

- Hesse, J. J., & Zöpel, C. (1990). Der Staat der Zukunft [The state of the future]. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Honeck, T. (2016). The importance of being Berlin: How narratives make urban policies travel “against the current” based on a study of temporary uses in Germany. Unpublished manuscript.

- Ibert, O. (2003). Innovationsorientierte Planung: Verfahren und Strategien zur organisation von innovation [Innovation-oriented planning: Procedures and strategies for the organisation of innovation]. Opladen: Leske & Budrich.

- Ibert, O., Christmann, G. C., Jessen, J., & Walther, U.-J. (2015). Innovationen in der räumlichen Planung. [Innovations in spatial planning]. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, (3), 171–182.

- Kreibich, R., Schmid, A. S., Siebel, W., Sieverts, T., & Zlonicky, P. (1994). Bauplatz Zukunft: Dispute über die Entwicklung von Industrieregionen [Construction site future: Disputes over the development of industrial regions]. Essen: Bauplatz Zukunft.

- Larner, W., & Laurie, N. (2010). Travelling technocrats, embodied knowledges: Globalising privatisation in telecoms and water. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 41(2), 218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.11.005

- Lave, J. C., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Läpple, D. (1986). Trendbruch in der Raumentwicklung: Auf dem Weg zu einem neuen industriellen Entwicklungstyp? [Breaking the trend in spatial development: Towards a new industrial development model?]. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, 11/12, 909–920.

- Lutzky, N., & Wettmann, R. W. (1982). Strategien der Raumordnung und Entwicklungsengpässe der 80er Jahre als Probleme der Landesentwicklung: Zusammenfassende Hypothesen [Strategies in spatial regulation and development shortfalls of the 80ies as problems of state development]. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, 9, 741–744.

- Mayntz, R. (2004). Governance im modernen Staat [Governance in the contemporary state]. In A. Benz (Ed.), Governance - Regieren in komplexen Regelsystemen: Eine Einführung [Governance – Governing in complex regulatory systems: An introduction] (pp. 65–76). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (2012a). Assembling urbanism: Following policies and ‘studying through’ the sites and situations of policy making. Environment and Planning A, 44(1), 42–51. doi: 10.1068/a44178

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (2012b). Policy assemblages, mobilities and mutations: Toward a multidisciplinary conversation. Political Studies Review, 10(3), 325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-9302.2012.00276.x

- Morgan, K. (1997). The learning region: Institutions, innovation and regional renewal. Regional Studies, 31(5), 491–503. doi: 10.1080/00343409750132289

- Moulaert, F., Jessop, B., Hulgård, L., & Hamdouch, A. (2013). Social innovation: A new stage in innovation process analysis? In F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood, & A. Hamdouch (Eds.), The international handbook on social innovation: Collective action, social learning and transdisciplinary research (pp. 110–130). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Moulaert, F., & Sekia, F. (2003). Territorial innovation models: A critical Survey. Regional Studies, 37(3), 289–302. doi: 10.1080/0034340032000065442

- Müller, F. C., & Ibert, O. (2015). (Re-)sources of innovation: Understanding and comparing time-spatial innovation dynamics through the lens of communities of practice. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 65, 338–350.

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2010). Mobilizing policy: Models, methods, and mutations. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 41(2), 169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.01.002

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2012). Follow the policy: A distended case approach. Environment and Planning A, 44(1), doi: 10.1068/a44179

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2015). Fast policy: Experimental statecraft at the thresholds of neoliberalism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Piore, M., & Sabel, C. F. (1984). The second industrial divide: Possibilities for prosperity. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Prince, R. (2010). Policy transfer as policy assemblage: Making policy for the creative industries in New Zealand. Environment and Planning A, 42(1), 169–186. doi: 10.1068/a4224

- Prognos. (2016). Lehren aus dem Strukturwandel im Ruhrgebiet für die Regionalpolitik. [Lessons from the structural change in the Ruhr Area for regional policy]. Retrieved from http://www.prognos.com/uploads/tx_atwpubdb/151111_Prognos_Endbericht_ Lehren_aus_dem_Strukturwandel__1_.pdf

- Ritter, E. H. (1979). Der kooperative Staat: Bemerkungen zum Verhältnis von Staat und Wirtschaft [The cooperative state: Remarks on the relation between state and economy]. Archiv des öffentlichen Rechts, 104, 389–413.

- Roy, A. (2012). Ethnographic circulations: Space-time relations in the worlds of poverty management. Environment and Planning A, 44(1), 31–41. doi: 10.1068/a44180

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1911). Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung [Theory of economic development]. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

- Siebel, W. (2015). Mega-events as vehicles of urban policy. In G. Grabher, & J. Thiel (Eds.), Perspectives in Metropolitan research: Self-induced shocks: Mega-projects and urban development (pp. 87–98). Berlin: Jovis.

- Siebel, W., Ibert, O., & Mayer, H.-N. (1999). Projektorientierte Planung - ein neues Paradigma? [Project-oriented planning – a new paradigm?]. Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, 3/4, 163–172.

- Stein, U. (2006). Lernende Stadtregion: Verständigungsprozesse über Zwischenstadt. [Learning urban regions: Understanding Zwischenstadt]. Wuppertal: Müller + Busmann.

- Temenos, C., & McCann, E. (2012). The local politics of policy mobility: Learning, persuasion, and the production of a municipal sustainability fix. Environment and Planning A, 44(6), 1389–1406. doi: 10.1068/a44314

- Temenos, C., & McCann, E. (2013). Geographies of policy mobilities. Geography Compass, 7(5), 344–357. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12063

- Vaatz, A. (1997). Eröffnung, Begrüßung und Einführung [Opening, welcome and introduction]. In Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung (ARL) (pp. 1–3). Hannover: Verlag der ARL.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wood, A. (2014). Moving policy: Global and local characters circulating bus rapid transit through South African cities. Urban Geography, 35(8), 1238–1254. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2014.954459

- Wood, A. (2015). Competing for knowledge: Leaders and laggards of bus rapid transit in South Africa. Urban Forum, 26(2), 203–221. doi: 10.1007/s12132-014-9248-y

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.