ABSTRACT

This paper considers how heterogeneous groups of regional stakeholders design and implement strategic activities that contribute to their region’s innovation capacity. We aim to understand how these stakeholder groups attempt to create new regional development pathways, and explore why otherwise enthusiastic and willing partnerships might fail to progress. We conceptualize this in terms of partners seeking to develop a shared actionable knowledge set as the basis for future development, and contend that one explanation for these failures might be a failure of the ways that partners combine their knowledge. We conceptualize strategic processes in terms of a series of distinct phases, and identify how problems in knowledge combination processes might manifest themselves in preventing the creation of valuable knowledge for subsequent action. Drawing on a detailed empirical case study of the Creative Science Park in Aveiro (Portugal), we argue that a better understanding of inter-stakeholder knowledge combination processes is necessary for creating and implementing better strategic transformational development processes for regions.

Introduction and problem setting

The creation of strategic regional innovation processes is an almost ubiquitous development/topic in contemporary economies (OECD, Citation2011) and much supporting work has been undertaken on identifying ‘ideal type’ approaches. Strategic processes involve regional partners arranging themselves towards purposive regional interventions that affect the overall regional development trajectory, and ideally upgrade the regional economy. The collective nature of these strategic processes imply that they should be more successful when more regional stakeholders are more substantively involved (Navarro, Valdaliso, Aranguren, & Magro, Citation2014). Regional strategic processes represent ongoing agreements between participants to work towards achieving common directions of travel and to jointly invest in and deliver work packages towards intermediate objectives that can be realized through collaboration (Valdaliso & Wilson, Citation2015). These regional strategic processes thereby result in regional change, and subject to the correct diagnosis being made, can help to build new regional development pathways that ultimately lead to more prosperous regions.

Despite extensive work on regional innovation strategies, Aranguren, Navarro, and Wilson (Citation2015) note that the activity of ‘strategy-making, in general, is a black box that needs opening up’ (p. 219). Theorization to date has been primarily preoccupied with describing the qualities of good strategies and setting out ideal type processes by which good strategies can be collectively/collaboratively created. This downplays the role of individual agency (Uyarra, Flanagan, Magro, Wilson, & Sotarauta, Citation2017) in favour of collective narratives (sometimes referred to as ‘happy family stories’ (Lagendijk & Oinas, Citation2005)). Those ‘happy family stories’ can in turn be critiqued for failing to examine how heterogeneous groups of regional actors with diverse interests can overcome internal tensions to agree to collectively fund joint action that deliver solutions intended to bring long-term benefits.

In this paper, we explore these tensions looking at the dynamics of actors in terms of goal setting and realization within strategic processes of regional innovation. Sotarauta (Citation2016) identified that problems emerge in implementing prospective agreements where regional partners can easily agree on long-term goals in principle, and then initial actions, but fail to continue to take the subsequent steps to deliver these desired long-term effects towards a wider locus of regional change. This paper is concerned with how successive short-term interventions may converge towards long-term strategic objectives, and how participants’ different interests affect these convergence processes. We ask the overarching research question: How can ‘actors within regional innovation collectives’ develop strategic regional innovation processes to improve longer-term regional economic performances?

In section 2, we present a framework explaining how actors collectively attempt to envisage and realize mutually beneficial outcomes in strategic regional innovation processes, highlighting the importance of knowledge combination processes in determining progress. We explore this framework using a single case study, based in the Aveiro region in Portugal, where a regional innovation collective experienced ongoing hindrance in the realization of its goals despite an apparent high level of consensus and enthusiasm for the regional innovation system. We highlight a number of problems in knowledge combination processes that arose early on in developing the science park, not hindering immediate process, but creating fissures that were problematic later. We conclude by arguing on the basis of this exploratory case study that this conceptualization appears useful for exploring regional innovation strategies. A better understanding of inter-stakeholder knowledge combination processes (reflecting different regional economic development contexts) is necessary for creating and implementing strategic transformational regional development processes.

Developing binding action frameworks to shape an uncertain future: a knowledge combination approach

To address this question, we propose a framework to understand how regional partners are coordinated into shared actions and ultimately improve longer-term regional economic performances. That coordination function is provided by strategic processes, processes where regional stakeholders are mobilized, their needs and opportunities articulated and arranged into a strategic plan, which is subsequently implemented. The overall coordination to longer-term regional changes comes through successive rounds of strategic processes in which partners attune to successes and failures between successive policy rounds. We regard coordination problems as a failure to successfully attune ongoing strategic processes, thereby failing to deliver this longer-term economic change.

The role of regional innovation coalitions in delivering strategic innovation processes

There has been growing scholarly and policy interest in understanding how regional policies affect innovation thereby promoting societal welfare and development (see for instance Borrás & Jordana, Citation2016). The reason for the focus on the region as a scale of analysis and implementation is because regions are the spaces within which various kinds of proximity can facilitate tacit knowledge exchange between partners, creating wider regional spill-over effects (Boschma, Citation2005; Maskell & Malmberg, Citation1999). Within this, some regions suffer from a set of problems that systematically inhibit territorial innovation, and modern innovation policy has emerged as an attempt to focus on equipping all regions to benefit from innovation by addressing these problems where appropriate (Benneworth, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2011; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2005).

This emphasis on equipping regions to address these problems is evident in the theories underpinning modern regional innovation policy such as Smart Specialization or Constructed Regional Advantage (McCann & Ortega-Argilés, Citation2013). These approaches emphasise the identification and implementation of case-specific regional solutions through strategic processes involving diverse stakeholders (Nieth et al., Citation2018) that are able to take into account the oft neglected subtle interdependencies between actors (Pinto & Rodrigues, Citation2010). These activities seek to deliver a series of changes that successively add up towards improvements in long-run regional economic performance. In the case of less successful regions that could involve what Cooke (Citation1995) refers to as an upward shifting of the ‘economic development road’.

We here foreground the idea of strategic processes as being central to the activation of agency within regional innovation policy to produce these upward shifts in regional economic performance. These strategic processes involve regional stakeholders coming together into what Benneworth (Citation2007) calls Regional Innovation Coalitions (RICs). RICs consult external experts and identifying the region’s current situation, strengths and opportunities, work creatively to identify regional weaknesses and propose policy interventions to strengthen existing regional assets (Boekholt, Arnold, & Tsipouri, Citation1998). Strategic processes have two functions within regional innovation policy: (a) they set out a pathway to a clearly desirable collective future state, and (b) they identify activities and interventions necessary to realize that desirable future. They are delivered within multi-actor and multi-level governance systems, are dependent on the past development of the region and involve a set of complex stakeholders with different capabilities and interests (Laasonen & Kolehmainen, Citation2017; Uyarra et al., Citation2017).

Given this complexity there is a need to consider in detail the way that actors’ behaviours in these coalitions lead to overall changes in the regional innovation environment (Benneworth, Pinheiro, & Karlsen, Citation2017; Hassink, Isaksen, & Trippl, Citation2019; Sotarauta, Citation2018). Activated agency approaches note that stakeholder groups working together to address regional challenges can compensate for the fact that any single organization may lack sufficient capabilities to develop and implement regional solutions (Arenas, Sanchez, & Murphy, Citation2013). Different agents with complementary elements of what Coffano and Foray (Citation2014) call ‘entrepreneurial knowledge’ work together on these processes, combining their individual knowledge sets to envision collective regional futures (van Tulder, Seitanidi, Crane, & Brammer, Citation2016).

Successful strategic processes involve creating, exchanging, managing and applying ‘different forms of popular and expert knowledge’ (Oliveira & Hersperger, Citation2018, p. 1). Their success therefore depends upon partners collective capacities to combine knowledge from ‘different sources, geographical scales and channels’ (Grillitisch & Trippl, Citation2014, p. 2306). Strategic activities are therefore not only processes of sharing knowledge, but creating new knowledge in processes that demand bargaining and compromising between different agents (Aranguren et al., Citation2015). But combining different kinds of knowledge within networks is not a straightforward process, and itself represents an innovation process (Asheim & Coenen, Citation2005). The nature of the knowledge changes in its combination and circulation between partners in pursuit of these collective goals. Partners seek to create through these combination processes what Aranguren and Larrea (Citation2011) call ‘actionable knowledge’, that provides the basis for activity and progression towards the longer-term goals of regional improvement. We follow the definition of Argyris (Citation1996) understanding ‘actionable knowledge’ as that knowledge that is required to implement external validity (relevance) and is thereby necessary to transform abstract knowledge into an everyday world context.

A shared set of regional goals must be formulated in ways that require different partners to contribute their implicit understandings of the region in ways that other partners understand and accept it. Partners must therefore first codify their internal tacit knowledge, then bring it together with others’ codified tacit knowledge, and combine it into a codified text (shared goals). Those goals must then be pursued by partners implementing individual innovation projects – those partners must firstly acquire that codified knowledge, and make sense of it to apply it to their own project to ensure it meets partners’ intentions. These switches between codified/tacit knowledge and internal/external knowledge change the nature of that knowledge and are not trivial processes (Nonaka, Citation1994; Nonaka & Takeuchi, Citation1995). This is complicated as creating futures is an unknowable and complex process. Participants’ willingness to make these efforts, notably to transfer private, tacit knowledge into the collective domain depends on those collective results’ value given their individual interests (Benneworth, Hospers, Jongbloed, Leiyste, & Zomer, Citation2011). And it is this issue of the calibration of individual interests within these collectivities that we contend has to date been missing from considerations of these strategic processes as they move from present uncertainty to future positive outcome.

RICs building actionable knowledge that delivers innovation outcomes

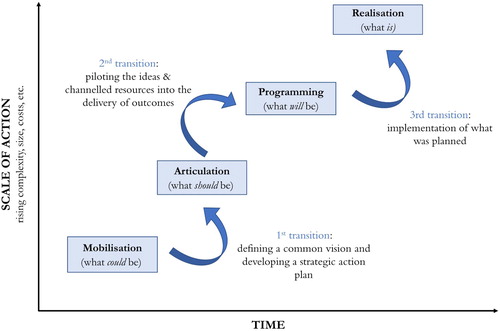

The purpose of the knowledge combination is to create actionable knowledge to proceed from present uncertainty to future positive outcome. We conceptualize this following Clarke and Fuller (Citation2010, p. 86)’s ‘integrated conceptual model for collaborative strategic planning and implementation’ as a progression between four qualitatively different states of strategic action, namely mobilization, articulation, strategic programming and realization. In this stylization, strategic processes see RICs combine knowledges to build actionable knowledge assisting progress between these four different states towards realizing desirable futures (see ). We actively modify the framework of Clark and Fuller – which is a linear pipeline – following Aranguren and Larrea (Citation2011) who stress path-dependency. We do that because of the nature of the object of study – a region rather not a single, easy-to-control business. Thus, we regard progress through the different states as a constructive struggle, where what can or cannot be achieved in one state affects how it does or does not progress to the next.

Figure 1. Four-state process of strategy formulation and implementation in RICs (Author’s own design based on Clarke and Fuller (Citation2010)).

The first state, mobilisation, involves developing a collective understanding between partners to function as an effective RIC. Partners bring a range of capacities to the coalition and – by signalling these capacities to others – a collective reflection on how capacities could potentially be applied to regional problems is developed. The RICs also begin identifying potential desirable future states, without necessarily specifying one particular choice. In this state, partners may opt in and out depending on relationships with the full coalition, and the potential desirability of the emerging regional future (Brinkerhoff, Citation2002).

The second state, articulation, is characterized by regional partners agreeing on an overall common vision, and the willingness to develop a collective plan to deliver that vision. This typically involves a discursive mechanism for negotiating priorities and potential regional futures, optimizing between individual interests/capacities and regional interest/need. Success here requires generating synergies and aligning diverse partners’ different needs and priorities. The time needed to achieve this prioritization varies depending on ‘the nature and extent’ of the issues requiring agreement, and is not amenable to bureaucratic timetables (Clarke & Fuller, Citation2010, p. 88).

In the third state, strategic programming, partners agree on clear operational plans for delivering high-level strategic visions. Partners in this state build certainty regarding the concrete activities to be delivered, and reach agreements on how different partners will combine their capacities to deliver added value and regional transformation. Strategic programming involves partners taking concrete decisions about what they will pursue and to make choices about how those activities will be delivered, reflecting individual interests and capacities along with the overall agreed regional goals.

The final state, realisation, is concerned with implementing planned activities, with partners combining their knowledge to ensure that what has been planned for can be delivered in practice. Individual activities here may focus upon appropriating extant collective knowledge and interpretation, and execution creating novel interventions whilst dealing with arising uncertainties. Individual partners here face the challenge of ensuring projects are not just successful in their own terms, but remained coupled with the wider regional strategic goals.

Knowledge combination failures as barriers to RIC success

Our modified Clarke & Fuller model describes progress by partners effectively combining knowledges to create actionable knowledge that enable those future actions that move towards the delivery of the strategic goals. We here draw upon Nonaka & Takeuchi’s knowledge combination model (Citation1995) which covers four processes: socialization, externalization, combination and internalization. We observe that there are two important dimensions in this model, a distinction between tacit and codified knowledge and between internal and external knowledge. It is these two dimensions that are most useful for us in understanding knowledge combinations in RICs. We argue that in RICs – trying to create an actionable collective knowledge base (and not just being concerned with internal knowledge) – there are three key knowledge combination processes: There is the internal curation of knowledge to contribute to strategic processes, combining internal tacit and codified capacities to produce knowledges that are placed into the collective sphere of the RIC. There is an external knowledge combination process in which RIC actors take these various inputs and seek to combine them into a shared knowledge capacity oriented towards improving long-term regional economic performance. There is then an actioning process where elements of the external knowledge are acquired by individual partners and absorbed to be transformed into a local actionable knowledge base.

Framing strategic processes as knowledge combination and transformation processes allows us to propose conditions under which RICs may fail to deliver regional transformation through being unable to effectively combine partners’ knowledge. In earlier phases, openness for discussion, compromise and cooperation of the different stakeholders is required to overcome emerging disagreements (Arenas et al., Citation2013). Later, openness ensures that particular activities’ execution and implementation remain aligned with the overall regional direction of travel. The success or failure of knowledge combination also depends on both the acceptability and reality of the emerging knowledge to the stakeholders, and whether an acceptable and realistic future can be agreed given diverse partners’ individual interests. The critical issue is the state transition, and the transformation of knowledge that takes place. We identify in below those problems that potentially arise within each state and hinder progression to the next state.

Table 1. Knowledge combination processes and barriers through strategic planning and implementation.

Methodology and introduction to case studies

Methodology

We use this framework to create an understanding of how RIC actors participate in knowledge combination activities creating actionable knowledge that influences longer-term regional economic performance. We adopt a qualitative exploratory approach, taking a single case study allowing sufficient analytic detail to give insights into whether the dynamics suggested in our framework are indeed evident. We explore a slow-moving strategic process to examine whether knowledge combination problems within these different states explain slow strategic processes. We use qualitative data to produce a synthetic narrative of strategic processes, which we then stylise using our concepts and compare with the proposed theoretical framework.

Fieldwork was conducted between January and August 2018. Primary data were collected through 45 qualitative semi-structured interviews – each lasting between 45 and 75 min. Interview partners were identified through informative conversations with relevant stakeholders of the RICs whereafter a snowballing approach was applied. The interviews focused upon asking participants to describe in their own words their collaborative efforts around the regional innovation strategy leading to the creation of a particular intervention (the Creative Science Park, see next section). Interviewees were asked to describe how regional partners collaborated in strategic processes, their own roles and their interactions with other actors. Interviews were anonymous and confidential, recorded and transcribed, and data analysis supported by the use of Atlas.ti software. The primary data was triangulated against secondary documents and archival records of interest, which covered reports produced as part of strategic planning, official collaboration agreements, strategic collaborative plans, newspaper articles and website content.

Case study region of Aveiro and introduction to the RICs

The chosen study region of Aveiro comprises 11 municipalities combined in the intermunicipal community of CIRA (Comunidade Intermunicipal da Região de Aveiro), situated in north-central Portugal. Aveiro is a small region in northern Portugal, with 370,000 inhabitants concentrated in a number of medium-sized cities (Aveiro, Águeda and Ovar). Although the region is sometimes described as peripheral/less favoured in the European context, it is a rather strong industrial region in the Portuguese context. It is home to several internationally leading firms with strongly emerging sectors such as the metallurgical, chemical, food, automobile, non-metallic minerals and electrical equipment industry (Rodrigues & Teles, Citation2017). Aveiro was chosen because as a Portuguese region, it had benefited from considerable investments in science and technology infrastructure since the early 1990s. Despite a desire dating back to 2000 amongst regional partners to create a science park – with serious discussions beginning in 2007 – the science park was only realized and formally opened in 2018; This offers a prima facie case of a non-straightforward (regional innovation) strategy process. The RIC was constituted around a stakeholder and shareholder group formed to deliver Aveiro’s Creative Science Park (hereafter the CSP), involving five types of partners:

scientific partners: Aveiro University (UA);

local government: Intermunicipal Community of the Region of Aveiro (CIRA), Municipalities of Aveiro and Ílhavo;

institutional partners: Industrial Association of Aveiro (AIDA), Inova Ria (Companies Association), Young Entrepreneurs Association, Administration of the Port of Aveiro and Portus Park;

financial partners: Caixa Geral de Depósitos and Banco Espírito Santo; and

companies: PT Inovação, Martifer, Visabeira, Civilria, Durit, Exporlux, Ramalhos, and Rosas Construtores.

The region is set in a cultural and historical context where the style of collaboration is highly dependent on personal interrelations as well as hierarchy and power distances (Kickert, Citation2011). It is important to note that strategic leadership in development processes – such as the one analysed in this paper – is often split between partners with no clear order, all claiming to know their region best and participating in what Sotarauta and Mustikkamäki (Citation2012) have termed the ‘strategic leadership relay’ for regional development (see also Beer and Clower (Citation2014) for a more detailed treatment). The University of Aveiro and the intermunicipal community (CIRA) found themselves at the centre of this collaborative leadership, with the core leadership role evolving over time from the university towards CIRA.

The CSP represents a continuation of an ongoing cooperation between UA, regional municipalities and industrial associations such as AIDA. The CSP sought ‘to be a strategic and operational promoter of innovative and entrepreneurial projects’ in five strategic areas, in line with UA’s strategic areas of information technologies, communication and electronics; materials; marine economy; agroindustry; and energy (Universidad de Aveiro, Citation2015, p. 75). Part of the structure of the case is a powerful core group of leaders, representing the university and the municipalities who are powerful within CIRA. There is then a wider stakeholder network that does not actively exert leadership, nevertheless there have historically been struggles between and disagreements around strategic regional priorities, often decided on by these two core groups. Occupying a 35ha site, three buildings opened in March 2018 housing the Business Incubator of UA, the UA Design Factory and the Laboratory for Common Use of Information Technology, Communication and Electronics (Georgieva, Citation2018). Of the total €35 m investment – provided from all the shareholders and co-financed by the Portuguese National Strategic Reference Framework (QREN) – €20 m have been spent to date. The second phase of construction, creating additional space for new companies, was still without a scheduled start date in early 2018.

Ten years in the making: the long road to the Creative Science Park of Aveiro

The realization of the science park was a ten-year process characterized by moments of rapid progress alongside periods of indecision and stasis. In this section, we present a stylized historical overview of the strategy process. The stylization involves highlighting process elements where actors sought to create collective understandings as the basis for action, although we hesitate in this section from seeking to immediately ascribe events to a particular state according to the theoretical framework. In section 5, we apply our conceptual framework to this historical overview to analyse the dynamics of knowledge combination processes and inform our concluding discussion.

Preceding connections and the big idea of building something together

One of the earliest activities between RIC participants – UA and the respective municipalities – related to the Aveiro lagoon, affected in the late 1980s by pollution and environmental challenges. To save the lagoon, the municipalities decided to design a common environmental policy that would also involve the UA as it was located near to the wetlands and had potentially useful knowledge on addressing those challenges. Various joint undertakings were subsequently developed, exemplified by the multi-party creation and implementation of territorial development plans for 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 to receive and manage a National Strategic Reference Framework grant (see detailed analysis in Rodrigues & Teles, Citation2017; Silva, Teles, & Rosa Pires, Citation2016).

These different joint activities – hoping not just to facilitate the knowledge economy but collectively building an element of the knowledge economy – led to the idea of creating ‘something ambitious’ between UA and CIRA. At this time, as a senior official related, regional partners agreed with the collective goal of creating ‘the most important example of cooperation between the region and the university’. The idea initially related to creating an industrial zone, and a feasibility study was undertaken, and in the course of those discussions, the common idea emerged of the desirability and feasibility of creating a ‘science park’.

Choosing a concept: fact-finding missions & the Tampere model

The idea of creating a science park began to seriously coalesce in late 2007 and – according to an academic close to the CSP process – was driven by the university ‘trying to spot an opportunity’ and starting the discussions with key entrepreneurs and municipalities. The choice of creating a science park was defined as an alternative to developing an industrial area or a real estate park. That choice can be traced back to the fact that municipalities were strongly interested in attracting new firms to their municipalities as an economic development strategy. They were worried of the potential for a science park to lure companies away from their industrial zones (thereby lowering resultant municipality business tax bases). The idea of the CSP as an alternative facilitated its choice precisely because it would not create competition with municipalities’ industrial zones.

As participants became enthusiastic about creating some type of science park, different concepts were explored with the intention to deliver a consensus about what kind of science park was suitable for Aveiro. UA was keen to ensure that the new science park fitted with strategic priority areas for regional innovation in the regional development strategy, and took an active lead at this point. Firstly, UA arranged a scoping study for possible contemporary science parks, followed by a series of field visits to science parks around Europe (Denmark, Sweden, Spain, Finland), along with regular meetings between and discussions amongst the regional stakeholders. The field visits were arranged with the help of UA employees drawing on their extensive international institutional networks to identify suitable site visits. The final decision on the Aveiro Science Park model was taken jointly between the university rector and the CIRA president – and they justified their choice with reference to the scoping study and field visits.

The model of the ‘Creative Science Park’ was chosen in the course of 2008 and 2009. A local government employee argued that the main aim of the CSP was to ‘grow the connections between the companies and the university and [to create …] a positive environment with innovation’. At the same time, it was intended to be ‘closer to firms than the traditional science and technology park’. The university employees defined the most suitable science park model drawing heavily on the science park visited in Tampere, Finland, although as one interviewee from UA noted ‘what they [the non-UA study trip participants] saw were buildings and not so much these institutional bases, which is much more important than the building’. Although UA did not share that understanding, the idea consolidated (possibly not consciously) amongst other partners that the CSP was primarily a real estate project rather than a focus for business support networks (the institutional bases alluded to in the previous quotation).

The difficulties of choosing locations & changes within the UA team

Once the decision was taken to create a CSP, the focus of stakeholder discussions shifted to determining its precise location. Although the science park model was chosen over an industrial park model, the emphasis on creating a set of buildings reawakened municipalities’ latent fears (critically amongst mayors) that the CSP would still lure businesses away from other municipalities. Mayors began actively competing with each other to win the CSP in the hope of attracting the businesses that the CSP was expected to bring.

UA is located at the border of Aveiro municipality, adjacent to Ílhavo municipality, and Ílhavo municipality was eventually chosen to host the CSP. Interviewees identified two main explanations for this decision: Firstly, because strong political interests ruled out other locations, and secondly, that the CSP could be created adjacent to UA allowing UA to expand into a new municipality whilst also allowing the CSP to benefit from proximity to UA infrastructure. The location decision was primarily political, driven by a desire amongst politicians ‘to show the people [their potential voters] that they are doing projects and building, building, building while not thinking in strategic terms – in the long term’. As part of this compromise, CIRA and UA promised to develop a study outlining how and why the CSP would benefit all municipalities (although this study never materialized). Interviewees also argued that the CSP location provided an expansion opportunity for UA in a neighbouring municipality, although there did not appear to be a significant potential for further student growth in UA.

Location competition also became controversial within the UA at various levels, particularly between the Department of Social, Political and Territorial Sciences (who were involved in the planning processes) and the Rectory team (initially with a clear institutional interest in expanding the Aveiro site). This internal disagreement covered a range of issues, from the location, and indeed whether the university should properly be involved in the science park; These disagreements led to some UA participants progressively withdrawing from the project. In 2010, rectorship elections led to an unexpected change in UA leadership, and the new leadership demanded changes to the science park model, focus and expected tasks. These changes demanded reopening discussions with partners and integrating new people into project structures which significantly slowed the development.

Planning regulations & public protests

The advancement of the CSP was then subsequently further delayed due to complications with land acquisition and the changes to planning regulations necessary for building the CSP. The disagreements within the RIC had seen land acquisition proceeding in a piecemeal way. This later hindered the development of the physical infrastructure linking the university and CSP: bridges, pathways and streets all had to cross land still in private ownership. These additional delays led individuals from other municipalities to publically criticize the project, claiming those problems demonstrated that the location choice was incorrect.

An additional complication came because the CSP zone lay within the Aveiro lagoon zone, land with substantial ecological and agricultural value. ONG Quercus, ‘one of the most important private environmental agencies in Portugal’ actively protested against creating the CSP in the chosen area, mobilizing local political parties against the project. These protests escalated into 13 different court cases (PÚBLICO, Citation2015; Santana, Citation2014). A number of interview partners noted that the CSP plans would preserve much of the land, create an observatory tower over the lagoon and be publicly accessible as both a research and knowledge centre, but also for recreational usage. After the CSP won the first court cases, the legal examination of the other cases was stayed, although the litigation compounded project delays.

Opening of the Creative Science Park

These delays compounded substantially: one high-level government employee observed: ‘When we started, we thought that we would put it out in six years […], but we have many, many problems, difficult problems. And we took twice the time that we thought at the start’. A company representative described this significant delay in opening as particularly complicated for companies involved whose business plans depended on the timely availability of suitable accommodation.

Having finally overcome the delays and complications, the CSP was officially inaugurated in March 2018, shortly before the UA rector’s mandate expired. The other municipalities had found themselves disengaging with the process as the difficulties of persuading residents of other municipalities that the CSP was also beneficial for the more distant parts of the region became clear. Although the CSP building was largely empty at its opening ceremony, the first three buildings were operational at the time of writing, hosting 80 organizations with 400 employees, including the UA Business Incubator, the Design Factory & diverse shared use laboratories (Universidad de Aveiro, Citation2019).

Knowledge combination problems across the four phases

We now use this stylized history to analyse the CSP as a case of strategy-making through knowledge combination processes, exploring how those processes unfolded and which factors influenced them. We stylise the case into four distinct phases corresponding with the conceptual model’s four states (we here term them phases to avoid a simple reading-off onto the model). In the first phase, UA provided important knowledge framing the science park notion and allowing sceptical municipalities to agree upon the desirability of creating some kind of science park. While both of the two main stakeholders (UA and CIRA) were jointly active in these initial developments and the ideation process, it was the university that was taking the lead in the first phases. In the second phase, UA oversaw a process to concretize a selection by municipalities, leading to the ‘Tampere model’ (as the centre of dense innovation networks) being chosen. In the third phase, a failure to achieve consensus manifested itself in a shift in project leadership towards leading municipalities, who imposed their reading on the CSP meaning (an attractive location for tax-paying businesses). This can be seen as the only, but very relevant shift in the balance of power throughout the complete process. In the final phase, the lack of a common position hindered sensible decision-making and saw lengthy delays in the development which – with the benefit of hindsight – were largely avoidable. We now characterize the nature of the knowledge combination processes in each phase.

The mobilisation phase involved partners deciding to collectively mobilize to create some kind of science park. The science park framing emerged because it finessed the problems that ‘business park’ framings carried which would benefit one municipality but penalize ten others. Building consensus was time-consuming and expensive, actors met repeatedly in different combinations to present their own interests and opinions and to seek a potential value-added compromise. The primary knowledge process was internal to UA, in which it used existing skills within the Department of Social, Political and Territorial Sciences, its own desire for expansion, and its institutional knowledge of the regional innovation priorities acquired thorough its past involvement in developing the region development strategy. Those three largely tacit knowledges were taken and combined internally into a set of reports that were then passed into and became part of the collective knowledge base. Municipalities absorbed that knowledge and transformed it internally to provide an answer to the question ‘what are the benefits and costs of a science park in another municipality for us?’. This tacit knowledge then allowed the municipalities to support the science park notion. The knowledge combination process created knowledge that aligned with and supported individual actor’s interests and produced a convergence that in turn transformed the meaning of the science park idea into being a relevant and timely regional innovation solution for Aveiro.

In the articulation phase, partners started to articulate precisely what kind of science park would be suitable for Aveiro. The knowledge combination process began again with UA, with an academic department using their contacts (internal tacit knowledge) to arrange a field trip for the group to help them understand the different models available for a science park. The intention was that the result should have been the same as in the articulation phase, namely that UA made its tacit knowledge available to regional partners who uncritically internalized it and used it to validate their internal interests. But in this acquisition step, the municipalities chose to acquire a very different set of knowledges from the collective knowledge base, acquiring the notion that it was a real estate development that was attractive to companies. That knowledge aligned with their internal interests, and because they believed that they were aligned with the collective understanding, it produced a consensus to proceed but a split in the shared knowledge between the network and real estate understanding of the ‘science park model’.

The strategic programming phase involved the final confirmation of the model, the choice of location and the precise content of the business plan. It was at this point that the split in the collective knowledge produced in the previous period became evident. Interestingly, this was in parallel with the project’s leadership centre shifting from UA to the leading CIRA municipalities. The domination of the real estate framing disempowered the university and saw the initiative shift back to the municipalities, who used their internal knowledge to create business cases for the science park to be located within their own municipalities, aligned with their individual interests to host the science park. This produced a strong knowledge dissonance, with 11 different versions (corresponding to the 11 municipalities) circulating of what should be the correct way forward. This also destabilized the internal knowledge of UA, as they understood the science park as a network location, and with these changes and the changes of rector, they had to acquire this new reading and find a way to align it with their institutional interest for room for growth. This created a knowledge split within the university that separated the institutional knowledge base from the departmental knowledge use. One example here can be that the knowledge related to the ecological dynamics of the lagoon effectively disappeared from the university knowledge capacity relating to the science park.

The realisation phase was earmarked by a series of delays and problems that reflected the knowledge splits that had built up within the RIC: A key issue was this split between institutional and departmental knowledge within UA that hindered the internal creation of a tacit knowledge base for action having acquired the external knowledge. This was manifested most clearly in two areas. The decision to acquire land in a piecemeal way rather than through eminent domain – ignoring the knowledge about science parks – created a practical issues relating to site access. The decision to build on land of high ecological value – ignoring the different departments’ knowledge – led to a conflict with the national environmental agency. It was in this phase that the lack of real convergence in the knowledge base was revealed, as the splits that had built up in the earlier phases meant that there were not the knowledge capacities in place within the RIC to ensure that the CSP development moved forward smoothly.

Table 2. Observed knowledge combination failures in the CSP strategic process.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have asked ‘How can actors within regional innovation collectives develop regional innovation activities to improve longer-term regional economic performances?’ We have focused on the issue of knowledge combination in regional strategic processes, and in particular, the issues that arise when heterogeneous actors combine their knowledge to create collective understandings that are sufficiently robust to serve as actionable knowledge later in strategic processes. The key finding from our research is that problems arise in knowledge combinations early in the process in the form of fissures within knowledge bases. These fissures were either within organizations (such as the split in UA between planning knowledge, institutional knowledge and knowledge of the regional development strategy) or collectively (the persistence of a science park model that could be both a real estate and a regional network model). These fissures did not immediately hinder consensus but did become problematic later in preventing the utilization of knowledge capacities (e.g. relating to the lagoon’s ecological status) to deal with implementation problems.

We see here that these knowledge combination failures and fissures resonances with the notion of what Sotarauta (Citation2016, Chapter 7) terms ‘strategic black holes’ in regional innovation processes; The tendency of RICs to repeat the same innovation interventions rather than upscaling and creating a more comprehensive and transformative innovation infrastructure. Our research provides an explanation for these black holes – the fissures in the actionable knowledge prevent that upscaling process. The actionable knowledge does not travel well – a single actor can deliver a single intervention that fits with a strategy – but lacks the broad hinterland of combined knowledge to construe it as a regional asset. The next result is that partners are trapped repeating past successes rather than consolidating those successes into more widespread regional transformation. There is a fissure that prevents the development of a regional knowledge base in of support developing regional innovation activities to improve longer-term regional economic performance. We are here struck that the issue of developing this transformational regional knowledge base is dealt with so frivolously in these agency activation approaches such as Smart Specialization.

We regard strategic regional processes as building futures by potentially creating knowledge capacities for collective action, shifting from uncertainty to a clear plan of deliverable action. From this perspective, our findings are significant because they highlight that the process of building a common understanding is not a dispassionate nor straightforward learning process. Building knowledges takes place within the boundaries of what partners are prepared to understand, and the prior learning and understanding of the actors and the partners. What partners are prepared to understand is partly – but not completely – conditioned by what regional leaders seek to promote, and this partiality may be a problem as it is not possible to compel other actors to understand those knowledges.

In this case, the knowledge dynamic appears to be a significant element of the exercise of agency: agency is bound by the prior learning and knowledge of the actors – for example relating to the five strategic priority sectors for the regional innovation strategy which the CSP could potentially strengthen. Conversely, the capacity to exert agency relates to the capacity to strategically deploy and combine knowledge and understanding. We believe this represents an interesting contribution in terms of the lack of understanding of how agency is exerted and creates influence in regional innovation strategy processes – as well as achieving purpose upon path development trajectories. To take it back to Sotarauta’s analysis, in our reading a ‘black hole’ may arise when partners believe there is a shared understanding when no such shared understanding exists.

In this case, we see interesting resonances with the way that the strategic process functioned in terms of providing the basis for a convergence of divergent interests, beliefs and viewpoints. In a way, the idea of a science park in mobilizing and articulating the strategic process served as what has been termed an ‘empty signifier’ (see for instance Gunder & Hillier, Citation2009). The very point of an empty signifier is precisely not to have ‘any one particular meaning [and taking] on a universal function of presenting an entirety of ambiguous, fuzzy, related meanings’ (Gunder & Hillier, Citation2009, p. 3). In an empty signifier, knowledge fissures are not problematic because there is no need for the knowledge to have coherence; it is only later, when the empty signifier should become actionable knowledge, that these fissures become problematic. The ‘science park as an empty signifier’ can help to establish a platform and bring different stakeholders together which – in an ideal case – succeed in opening up new horizons that they never planned for in the first place. Yet, the ‘science park as an empty signifier’ can also lead to frustration in later policy circles when stakeholders realize that what they signed up for was blurry and turned out to be far away from what they expected. A key challenge here for both further research and policy-makers is how to balance the trade-off between early progress and later certainty in strategic regional innovation processes, and to ensure there are effective knowledge combination processes without hindering consensus and coalition forming.

Our case also highlights a methodological problem in the study of agency in regional innovation strategy processes, relating to the dynamics of collective understanding. Although partners apparently sincerely believed in the early phases that there was a shared understanding of the CSP as a collective regional asset, this model had not been successful in completely supplanting the local business park variant. Indeed, it was that second variant that framed the ways that the partners undertook the next stage of the process. There is, therefore, a need to look at these knowledge processes in a longer-term process, considering the competing forms of understanding within regional innovation strategy processes, foregrounding knowledge fissures, identifying which variants dominate, and the potential inconsistencies and controversies that emerge in the wake of those fissures. This suggests that ‘agency’ in knowledge combination (successfully achieving a fissure-free shared understanding) is only revealed in later practice, and cannot simply be claimed by regional partners. More reflection is needed on how to methodologically analyse these situations, because simply claiming fissures exist on the basis of failures seems to risk making these fissures a ‘catch-all’ explanation.

Our analysis also suggests that we need to be aware of the difficulties different actors might bring into a strategic innovation process or path development process. The university, often considered only as an important knowledge provider, was a complex and messy actor in this process, and prone to knowledge fissures. While some UA activity in these knowledge combination processes made sense to some communities (notably the rectory team), this disenchanted some academics involved and thus lead to internal complications. This demands a rethinking of our understanding of universities and the role they play in regional systems reflecting their situation as complex actors with multiple roles, as ‘fissile’ knowledge actors – prone to knowledge fissures that may create problems elsewhere in the RIC. We acknowledge the limitations of a single case in terms of wider conclusions, nevertheless, this research is a way to give room to the important discussion of micro-scale agent behaviour and dynamics of regional stakeholder coalitions. Considering the combination of individual actors’ knowledge bases, activities, motivations and their involvement in regional processes as well as in the development of regional growth paths is a first step towards understanding how regions can be supported in their development efforts toward new futures.

Acknowledgements

The project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under MSCA-ITN Grant agreement No. 722295. A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers (Washington D.C., April 2019) and the Workshop ‘Agency, Higher Education Institutions and Resilience’ of the University of Tampere (Tampere, March 2019). The authors would like to thank the editors of this volume and two anonymous referees for their constructive comments. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aranguren, M., & Larrea, M. (2011). Regional innovation policy processes: Linking learning to action. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 2(4), 569–585. doi: 10.1007/s13132-011-0068-1

- Aranguren, M., Navarro, M., & Wilson, J. (2015). Constructing research and innovation strategies for smart specialisation (RIS3). In J. Valdaliso & J. Wilson (Eds.), Strategies for shaping territorial competitiveness (pp. 218–242). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Arenas, D., Sanchez, P., & Murphy, M. (2013). Different paths to collaboration between businesses and civil society and the role of third parties. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(4), 723–739. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1829-5

- Argyris, C. (1996). Actionable knowledge: Intent versus actuality. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 32(4), 441–444. doi: 10.1177/0021886396324008

- Asheim, B., & Coenen, L. (2005). Knowledge bases and regional innovation systems: Comparing Nordic clusters. Research Policy, 34(8), 1173–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2005.03.013

- Beer, A., & Clower, T. (2014). Mobilizing leadership in cities and regions. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 1(1), 5–20. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2013.869428

- Benneworth, P. (2007). Leading innovation: Building effective regional coalitions for innovation. Research Report from the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA). London: NESTA.

- Benneworth, P. (ed.). (2018). Universities and regional economic development - Engaging with the Periphery. London: Routledge.

- Benneworth, P., Hospers, G., Jongbloed, B., Leiyste, L., & Zomer, A. (2011). The 'Science City' as a system coupler in fragmented strategic urban environments? Built Environment, 37(3), 317–335. doi: 10.2148/benv.37.3.317

- Benneworth, P., Pinheiro, R., & Karlsen, J. (2017). Strategic agency and institutional change: Investigating the role of universities in regional innovation systems (RISs). Regional Studies, 51(2), 235–248. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1215599

- Boekholt, P., Arnold, E., & Tsipouri, L. (1998). The evaluation of the pre-pilot actions under Article 10: Innovative Measures regarding Regional Technology Plans. Report to the European Commission. Retrieved from www.innovatingregions.org/download/RTPreport.pdf

- Borrás, S., & Jordana, J. (2016). When regional innovation policies meet policy rationales and evidence: A plea for policy analysis. European Planning Studies, 24(12), 2133–2153. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1236074

- Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74. doi: 10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Brinkerhoff, J. (2002). Assessing and improving partnership relationships and outcomes: A proposed framework. Evaluation and Program Planning, 25(3), 215–231. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(02)00017-4

- Clarke, A., & Fuller, M. (2010). Collaborative strategic management: Strategy formulation and implementation by multi-organizational cross-sector social partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 85–101. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-0781-5

- Coffano, M., & Foray, D. (2014). The centrality of entrepreneurial discovery in building and implementing a smart specialisation strategy. Italian Journal of Regional Science, 13(1), 33–50. doi: 10.3280/SCRE2014-001003

- Cooke, P. (1995). Keeping to the high road: Learning, reflexivity and associative governance in regional economic development. In P. Cooke (Ed.), The rise of the rustbelt (pp. 231–245). London: UCL Press.

- Georgieva, O. (2018). The Mayor of Aveiro, Mr. José Ribau Esteves: It is very important that citizens have an accurate picture of the importance of the European Union for their lives. TheMayor.eu. Retrieved from www.themayor.eu/en/the-mayor-of-aveiro-mr-jose-ribau-esteves-it-is-very-important-that-citizens-have-an-accurate-picture-of-the-importance-of-the-european-union-for-their-lives

- Grillitisch, M., & Trippl, M. (2014). Combining knowledge from different sources, channels and geographical scales. European Planning Studies, 22(11), 2305–2325. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.835793

- Gunder, M., & Hillier, J. (2009). Planning in ten words or less. A Lacanian entanglement with spatial planning. London: Routledge.

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Kickert, W. (2011). Distinctiveness of administrative reform in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain. Common characteristics of context, administrations and reforms. Public Administration, 89(3), 801–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01862.x

- Laasonen, V., & Kolehmainen, J. (2017). Capabilities in knowledge-based regional development – towards a dynamic framework AU. European Planning Studies, 25(10), 1673–1692. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1337727

- Lagendijk, A., & Oinas, P. (2005). Proximity, external relations, and local economic development. In A. Lagendijk, & P. Oinas (Eds.), Proximity, distance, and diversity: Issues on economic interaction and local development (pp. 336). London: Routledge.

- Maskell, P., & Malmberg, A. (1999). Localised learning and industrial competitiveness. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 23, 167–185. doi: 10.1093/cje/23.2.167

- McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2013). Modern regional innovation policy. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 6(2), 187–216. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rst007

- Navarro, M., Valdaliso, J., Aranguren, M., & Magro, E. (2014). A holistic approach to regional strategies: The case of the Basque Country. Science and Public Policy, 41(4), 532–547. doi: 10.1093/scipol/sct080

- Nieth, L., Benneworth, P., Charles, D., Fonseca, L., Rodrigues, C., Salomaa, M., & Stienstra, M. (2018). Embedding entrepreneurial regional innovation ecosystems – Reflecting on the role of effectual entrepreneurial discovery processes. European Planning Studies, 26(11), 2147–2166. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2018.1530144

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37. doi: 10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- OECD. (2011). Regions and Innovation Policy. Retrieved from Paris: www.oecd.org/regional/regionsandinnovationpolicy

- Oliveira, E., & Hersperger, A. (2018). Disentangling the governance configurations of strategic spatial plan-making in European urban regions. Planning Practice & Research, 34(1), 47–61. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2018.1548218

- Pinto, H., & Rodrigues, P. (2010). Knowledge production in European regions: The impact of regional strategies and regionalization on innovation. European Planning Studies, 18(10), 1731–1748. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2010.504352

- PÚBLICO. (2015). Ílhavo inaugurates controversial access to Science and Innovation Park [Ílhavo inaugura acesso polémico ao Parque da Ciência e Inovação]. PÚBLICO. Retrieved from www.publico.pt/2015/04/30/local/noticia/ilhavo-inaugura-acesso-polemico-ao-parque-da-ciencia-e-inovacao-1694137

- Rodrigues, C., & Teles, F. (2017). The Fourth Helix in smart specialsiation strategies: The gap between discourse and practice. In S. Monteiro & E. Carayannis (Eds.), The quadruple innovation helix nexus: A smart growth model, quantitative empirical validation and operationalization for OECD countries (pp. 111–136). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Santana, M. (2014). Quercus tries to stop work on the access road to the Science Park of Aveiro [Quercus tenta parar obra da via de acesso ao parque da ciencia de aveiro]. PÚBLICO. Retrieved from www.publico.pt/2014/04/07/local/noticia/quercus-tenta-parar-obra-da-via-de-acesso-ao-parque-da-ciencia-de-aveiro-1631372

- Silva, P., Teles, F., & Rosa Pires, A. (2016). Paving the (hard) way for regional partnerships: Evidence from Portugal. Regional & Federal Studies, 26(4), 449–474. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2016.1219720

- Sotarauta, M. (2016). Leadership and the city: Power, strategy and networks in the making of knowledge cities. London: Routledge.

- Sotarauta, M. (2018). Smart specialization and place leadership: Dreaming about shared visions, falling into policy traps? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 190–203. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2018.1480902

- Sotarauta, M., & Mustikkamäki, N. (2012). Strategic leadership relay: How to keep regional innovation journeys in motion? In M. Sotarauta, L. Horlings & J. Liddle (Eds.), Leadership and change in sustainable regional development (pp. 190–211). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2005). One size fits all? Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Research Policy, 34(8), 1203–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.018

- Universidad de Aveiro. (2015). UA Enterprises: Competences and Services. Retrieved from Aveiro: https://issuu.com/universidade-de-aveiro/docs/ua_enterprises_web

- Universidad de Aveiro. (2019, March 22). Ministro Adjunto e da Economia no aniversário do PCI - Creative Science Park Aveiro Region [Minister of State and Economy at the anniversary of the PCI - Creative Science Park Aveiro Region]. UA Online. Retrieved from https://uaonline.ua.pt/pub/detail.asp?c=57644&lg=pt

- Uyarra, E., Flanagan, K., Magro, E., Wilson, J., & Sotarauta, M. (2017). Understanding regional innovation policy dynamics: Actors, agency and learning. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(4), 559–568. doi: 10.1177/2399654417705914

- Valdaliso, J., & Wilson, J. (eds.). (2015). Strategies for shaping territorrial competetiveness. Abingdon: Routledge.

- van Tulder, R., Seitanidi, M., Crane, A., & Brammer, S. (2016). Enhancing the impact of cross-sector partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(1), 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2756-4